Abstract

Collaborative mapping has emerged in recent decades as a key practice for producing open geospatial knowledge and fostering critical citizenship. However, several studies have shown that these platforms may reproduce existing gender inequalities, both in terms of participation and representation. This article examines the potential of collaborative feminist cartography as a strategy for making inequalities visible and promoting gender equality in public space. Methodologically, the study focuses on the project Las Calles de las Mujeres, developed by Geochicas OSM, combining quantitative analysis of street naming in urban development with qualitative implementation in educational contexts. A global overview of 32 cities in 11 countries is provided, with a detailed case study of 11 Spanish cities. Results confirm the persistence of a significant gender gap in urban toponymy: streets named after men not only outnumber those dedicated to women but are also on average longer, more central, and symbolically more prominent. Educational experiences in Spain provide learning outcomes and demonstrate that collaborative mapping strengthens spatial thinking, digital competence, and critical awareness, linking geography education to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 5 and SDG 11). The article concludes that feminist mapping initiatives are simultaneously pedagogical, social, and political tools, capable of fostering more inclusive and sustainable cities.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, collaborative mapping has become central to the production of open geospatial knowledge, with platforms such as OpenStreetMap (OSM) emerging as one of the most important global sources of free spatial data [1]. However, several studies have stressed that this model is not neutral and may reproduce pre-existing gender inequalities [2,3]. In particular, the underrepresentation of women both as contributors of data and as subjects represented in urban space remains a significant challenge for digital inclusion [4].

The field of feminist cartography has emerged at the intersection of technologies and territories. Authors such as Kwan and Pavlovskaya have shown how Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and mainstream maps have historically reflected male-dominated views of space [5,6]. In response, feminist collectives have promoted new mapping practices that seek to make inequalities, silences, and violence visible, reclaiming maps as political tools [6,7]. Initiatives such as HarassMap in Egypt or Women Under Siege in Syria demonstrate the potential of collaborative mapping to document gender-based violence and expose structural inequalities [8].

Building on feminist geographies that conceptualize space as socially produced and gendered [8,9,10], we approach mapping as an epistemic practice capable of making differentiated experiences of urban life visible while avoiding assumptions of neutrality in data and representation. This perspective situates feminist cartography within a broader critique of how spatial knowledge is constructed, disseminated, and used, linking cartographic practices to questions of recognition, inclusion, and agency. Feminist cartographic approaches therefore seek not only to visualize the absence or presence of women in urban space but also to interrogate the mechanisms through which certain narratives become spatially dominant.

Complementing these insights, theories of justice and capabilities [11,12,13,14] provide a pragmatic framework that aligns feminist mapping with educational and policy-oriented objectives, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 5 and SDG 11). These approaches emphasize procedural fairness, redistribution, and recognition as central principles of spatial equity. Within this framework, feminist collaborative mapping can be understood as a reflective, evidence-based practice that promotes more inclusive urban governance and contributes to civic education by connecting local spatial analysis with global sustainability agendas.

Beyond theory, recent empirical work shows that feminist cartography is methodologically diverse and participatory: from digital/PGIS to embodied and arts-based mapping, often combining multiple techniques to foreground lived experiences of inequality [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. These approaches consistently link visibility to agency, reporting outcomes such as capacity-building, community advocacy, or—in some cases—policy influence through collaborative data production and reinterpretation of spatial knowledge.

Feminist cartography, in this sense, cannot be reduced to the inclusion of women in maps or data; it emerges from broader feminist epistemologies that question who produces spatial knowledge and whose experiences are made visible [18,22,23,24]. From this perspective, mapping becomes a reflective act that exposes power relations underlying spatial representation. Gloria Anzaldúa’s notion of mestiza consciousness in Borderlands/La Frontera (1987) offers a useful metaphor for feminist mapping: crossing the boundaries of dominant narratives and acknowledging hybrid identities and multiple epistemologies [23]. In turn, Butler’s idea of performativity [24] and Hill Collins’s concept of situated knowledge illuminate how everyday spatial practices reproduce or challenge social hierarchies [25], while Data Feminism [18] demonstrates how open data can serve equity and participation. Feminist mapping is thus less about counting women than about creating spaces for knowledge that reveal and redress structural inequalities.

Within this framework, the collective Geochicas OSM was founded in 2016 within the OSM community in Latin America, with the aim of reducing the gender gap in digital cartography and empowering women through open data [26]. Since then, this collective has launched emblematic projects such as Las Calles de las Mujeres (“Women’s Streets”) [27], which exposes the limited representation of women in city toponymy, and Yo te nombro (“I Name You”), a collaborative map of feminicides in Mexico [28]. These projects reveal both the transformative power of collaborative mapping and the urgency of contesting the hegemony of corporate platforms such as Google Maps, whose commercial logic contrasts with the open and community-driven ethos of OSM [29,30].

In academia, geography has proven to be a key discipline for advancing education for sustainability and spatial citizenship, in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In particular, SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) can be effectively addressed through collaborative mapping, which fosters critical awareness of gender inequalities in urban space [1]. Experiences in Spain and Latin America have shown how these methodologies are integrated into teacher training and school projects, enabling students to analyze the unequal representation of women in street naming and to propose creative alternatives for change [1,31,32].

The current state of research reflects an ongoing debate. While some authors argue that collaborative mapping contributes to democratizing knowledge and enhancing inclusion [31], others caution that, without an explicit gender-sensitive perspective, these platforms may perpetuate the same biases they seek to overcome [32]. In this context, feminist collaborative mapping projects provide an innovative model that combines digital empowerment, community participation, and gender-sensitive data production.

This article builds on this background and aims to analyze the role of feminist collaborative mapping as strategies for making inequalities visible and promoting gender equality in public space. Our hypothesis is that such practices not only reduce the gender gap in digital participation but also redefine what is mapped and how it is represented, thereby contributing to more inclusive and sustainable cities. Ultimately, we propose that feminist collaborative mapping constitutes a pedagogical, social, and political tool for advancing toward urban sustainability and equity.

2. Collaborative Mapping for Citizen Participation Towards Equity

As has already been noted, collaborative mapping is not only a technical tool for generating open geospatial data but also functions as a social and educational strategy capable of challenging inequalities and promoting equity. Recent literature acknowledges the value of these practices in geographic and civic education, although scientific production that explicitly analyzes the potential of feminist collaborative cartography remains limited [33,34,35,36].

The work of Haklay and Budhathoki [37] is particularly relevant, as it highlights how participation in collaborative mapping is marked by profound gender inequalities, shaping both the type of information represented and the way it is produced. This diagnosis has been crucial to the emergence feminist initiatives that aim to reduce this gap and place gender at the center of collaborative mapping. Their work clearly illustrate that maps are not neutral products but rather social constructions that reproduce existing power structures [37].

A set of experiences developed by the authors of this article confirms the potential of collaborative mapping in education. The findings of Álvarez-Otero, De Miguel, and Sebastián [35], based on participatory design with geospatial technologies in Spanish secondary classrooms, revealed significant improvements in students’ spatial, digital, and citizenship competences, reinforcing the importance of integrating these methodologies into education for sustainability and active citizenship [35,36].

In the same line, the project Las Calles de las Mujeres https://github.com/geochicasosm/lascallesdelasmujeres/blob/master/README.en.md (accessed on 31 October 2025) has been implemented by the authors of this article in the cities of Zaragoza and Huesca, Spain. In Zaragoza, the project engaged university students and prospective teachers, linking the critique of urban toponymy with the development of digital and civic competences [1,31,38]. In Huesca, it was adapted to secondary education, where students investigated the underrepresentation of women in the local street naming and proposed creative alternatives to make visible women relevant to the local history of their community [31,32]. Both cases demonstrate that feminist collaborative mapping not only produces data but also fosters active learning, social awareness, and civic empowerment, thereby contributing to the advancement of gender equality and sustainable urban development.

Beyond educational practice, collaborative mapping can become a tool for social and political transformation. Projects such as Las Calles de las Mujeres in Latin America or the feminicide map Yo te nombro (“I Name You”) in Mexico highlight how maps can serve as instruments of denunciation and public opinion building [27,28]. This approach connects with the tradition of critical cartography and feminist geography, where authors such as Leszczynski and Elwood [39] have underlined that new spatial media may reproduce exclusionary logics unless explicitly addressed. In the same direction, reflections on the ambiguities of cartographic representation [40] or the debates in feminist cartography [41] reaffirm the need to question dominant narratives and build alternative spatial imaginaries.

Thus, feminist collaborative mapping emerges as a dual resource: on the one hand, an educational strategy that strengthens critical citizenship formation at all levels, and on the other, a social and political strategy that challenges technological and commercial hegemonies, instead promoting open, inclusive, and community-driven geospatial knowledge [26,27,28].

3. Materials and Methods

The research is based on a methodological approach that combines collaborative mapping with critical geographic and geospatial education. Following the previous sections, which highlighted the relevance of feminist cartography and the potential of collaborative mapping to promote equity, this methodological block provides a detailed account of the materials, tools, and procedures employed. In particular, it describes the use of open geospatial database, the role of collaborative feminist initiatives in reducing the gender gap in digital cartography, and the development of the Las Calles de las Mujeres project as a representative case study. Furthermore, it outlines the process of data extraction, classification, and verification, as well as the subsequent visualization of the results through an interactive web viewer. These are simple and replicable procedures, which make it possible to transfer experience to other educational, spatial and civic contexts, thus reinforcing its pedagogical value and its capacity to foster social participation in every city or community.

3.1. OpenStreetMap (OSM) and Data Contribution

OpenStreetMap (OSM) is a global collaborative mapping platform based on open data, where thousands of volunteers continuously generate, edit, and enrich geospatial information. Its architecture relies on changesets (sets of edits), which ensure the traceability, transparency, and reproducibility of every contribution.

Data can be introduced into OSM through online editors such as iD Editor, designed for beginners, or more advanced applications like JOSM (Java OpenStreetMap Editor), which allows the integration of multiple layers and external formats (.csv,. shp,. geojson). Within JOSM, specific plugins are often used, including OpenData (to import external files) and TODO list (to manage task batches and validate each point sequentially).

The import and editing process follows a standardized sequence:

- Creation of a dedicated user account: In collective projects, such as those developed it is recommended to create dedicated accounts for bulk imports. This facilitates the tracking, auditing, and potential reversion of changes.

- Loading the external file: Through the OpenData plugin, data are incorporated in compatible formats (e.g., .csv) and projected into a standardized reference system. Task management: Imported points are organized into a list managed with the TODO list plugin, which allows detailed monitoring of the progress (percentage reviewed, pending, corrected).

- Spatial verification: For each element, a cartography layer is downloaded into an active layer to verify its exact location and correct potential errors. This step ensures consistency with existing buildings, checks address attributes (addr:street, addr:housenumber), and prevents duplication.

- Corrections and adjustments: Incomplete addresses, missing tags, or misaligned points are corrected according to the community’s tagging conventions documented inopen repositories.

- Validation and upload of changes: Before publication, JOSM runs an automatic validation process to detect errors or inconsistencies. The changeset is then uploaded with standardized metadata (comment, source, import = yes, url), ensuring full transparency and reproducibility of the process.

This procedure guarantees that imported data meet the quality and consistency standards established by the OSM community. Furthermore, as all contributions are published under the Open Database License (ODbL), the data can be freely reused by citizens, researchers, and public institutions.

3.2. The Role of Geochicas OSM in OpenStreetMap

This collective stands out for its participatory approach to digital mapping, combining technical training, open data production, and gender-sensitive analysis to make women’s presence and experiences visible in urban spaces, online networks, and open data environments.

The collective structures its methodology across four main dimensions:

- Technical training and capacity-building: They organize workshops, webinars, and both in-person and online mapathons where participants learn to use open-source editors (iD, JOSM), import open formats (.csv, .shp, .geojson), and apply quality and validation criteria. These spaces not only provide technical competencies but also aim to break down barriers of access and confidence that have historically limited women’s participation in digital communities.

- Gender-sensitive data production: Unlike other crowdsourcing projects, these initiatives introduce explicit methodological criteria to ensure the inclusion of data often rendered invisible in traditional cartography, such as female representation in street names, feminicides, or unsafe spaces for women. This critical selection of what to map and how to map it is one of their main innovations.

- Design of replicable and scalable projects: Initiatives such as Las Calles de las Mujeres or Yo te nombro (“I Name You”) are based on open methodologies documented in repositories (GitHub, wikis) that facilitate replication across contexts. This involves standardized processes of data collection, cleaning, classification, and visualization, reinforcing transparency and promoting both scientific and civic reuse.

- Community validation and open visualization: The editing process is always accompanied by verification phases through traceable changes and the publication of accessible web viewers. This component ensures data traceability and makes the results available as educational, political, and social resources.

From a methodological standpoint, feminist collaborative mapping goes beyond mapping: it advances a pedagogy and digital model that combines (i) technical learning in geospatial tools, (ii) the development of critical awareness about gender inequalities in public space, and (iii) the generation of open data that can be used for research, teaching, and social action.

This methodological framework has positioned the collective as an example of best practices at the intersection of critical cartography, feminism, and geotechnologies, providing a foundation for applied experiences in both educational and civic contexts across Latin America and Europe.

3.3. Collaborative Mapping Process: Las Calles de las Mujeres

The project Las Calles de las Mujeres constitutes a paradigmatic example of critical and feminist cartography applied to urban toponymy. Its methodological design combines open technological tools with citizen participation dynamics, creating a replicable model across multiple cities in Latin America and Europe.

The procedure is organized into consecutive phases, documented in the project’s GitHub repository (https://github.com/geochicasosm/lascallesdelasmujeres.git (accessed on 31 October 2025) and reproducible by any collective or institution:

- Street network extraction: through an automated script, the complete list of a city’s streets is obtained from open geospatial databases, ensuring that the starting point is open and constantly updatable.

- Gender classification: street names are categorized according to whether they commemorate men, women, collectives, or other references, thus making visible the quantitative inequalities in gender representation.

- Database enrichment: biographies of the women represented are incorporated, along with references to Wikipedia articles and documentary links that contextualize their trajectories.

- Collaborative verification: participant teams review, correct, and validate the information through collective editing and quality control dynamics, ensuring the coherence and reliability of the generated data.

The most notable characteristics of the project are its openness (Figure 1), as data and scripts are publicly available; its replicability, as it employs standardized methodology adaptable to different contexts; and its intersection between geoinformation and historical narratives by connecting toponyms with biographies and collective memory.

Figure 1.

Open repository of the project Las Calles de las Mujeres, hosted on GitHub, where code, scripts, sample datasets, and methodological guidelines are publicly available. This space documents each phase of the workflow and ensures the openness, replicability, and transparency of the methodology, enabling other collectives and institutions to reproduce and adapt the project in different cities (https://github.com/geochicasosm/lascallesdelasmujeres, accessed on 31 October 2025).

From an educational approach, Las Calles de las Mujeres has been implemented in schools, universities, and teacher training programs, enabling students to analyze the underrepresentation of women in street naming, reflect critically on the biases of urban memory, and propose alternatives for change. At the same time, the project serves as a social and political tool of denunciation, by making visible gender inequality in urban space and advocating for more inclusive and equitable cities.

3.4. Online Visualization and Interactive Web Viewer

The results of the project are disseminated through an open and interactive web viewer available at: https://geochicasosm.github.io/lascallesdelasmujeres/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

This viewer represents the final stage of the methodological workflow and fulfills a dual function: the dissemination of results and the active engagement of citizens. Its main features include:

- Dynamic filters by gender and categories: users can quickly identify streets named after women, men, collectives, or other references, allowing for immediate comparative analysis.

- Integration of biographies and external links: each street named after a woman is accompanied by additional information, including Wikipedia articles and documentary references, which provide broader historical and social context.

- Statistical visualization: the viewer displays charts and percentages summarizing the degree of female representation in the street naming of each city, offering a clear and accessible quantitative dimension.

- Open and replicable design: built with free technologies such as Leaflet, JavaScript, and GitHub Pages, the viewer can be adapted to different local contexts, enabling reuse and adaptation by communities, educational institutions, or public administrations.

Its interactive and multi-platform nature makes it a widely accessible educational resource (Figure 2), used in school, university, and teacher training projects. At the same time, it serves as a civic and political tool, as it facilitates understanding of women’s underrepresentation in urban space and encourages active participation in generating proposals for change.

Figure 2.

Online viewer of Las Calles de las Mujeres, which allows filtering by gender, accessing biographical information linked to Wikipedia, and exploring statistics of representation in each city https://geochicasosm.github.io/lascallesdelasmujeres/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

Our design aligns with participatory strands in feminist cartography that leverage PGIS, open-source tools and collaborative verification to connect situated knowledge with reproducible spatial evidence [15,16,17,21]. By coupling open data with community-led validation and accessible visualization, we follow best practices that translate visibility into practical agency—from classroom deliberation to locally usable evidence.

At the same time, we adopt a critical perspective on the technical and epistemological conditions that frame our work. We acknowledge the limitations inherent in the use of rectangular projections for global representation, as highlighted by Robinson (1990), who noted that such projections tend to distort spatial relations and reinforce Eurocentric views of the world [30]. In this sense, we recognize that the Web Mercator (pseudo-Mercator) projection, commonly used by open mapping platforms, while functional for web visualization, is not the most equitable or distorted in representing global diversity. Therefore, our methodological approach embraces these limitations as part of a reflective practice—one that not only produces data but also questions the technical and symbolic frameworks through which space is represented.

In summary, the viewer is not only a final product for dissemination but also a pedagogical and social platform that connects OSM-generated data with critical narratives and processes of collective transformation.

4. Results

This section presents the results obtained from the general analysis of streets named after women mapped in the project, with the aim of providing a global overview of the state of urban toponymy in terms of gender and equality, followed by a more specific focus on the Spanish case. The 32 cities analyzed were selected based on three criteria: (i) availability of open street data, (ii) active participation of local communities in street mapping and (iii) regional diversity across Europe and Latin America to ensure comparative representation. This combination of technical feasibility and community engagement reflects the collaborative ethos of feminist cartography. Once the extraction, classification, and verification of the data were completed, the visualization and critical analysis of the Las Calles de las Mujeres project were structured into different phases: (i) the global overview of mapped cities, (ii) the case study of Spanish cities.

4.1. Geographical Distribution of Mapped Cities

A total of 32 cities across 11 countries were analyzed within the framework of the Las Calles de las Mujeres project (Table 1). The largest concentration of cases was found in Spain (13 cities, 34%) and Argentina (10 cities, 28%), which together account for 62% of the total. This reflects both the active participation of local communities and the strong connection of the project to the Ibero-American context. In a secondary position, Peru (1 city, 11%) and Mexico (1 city, 10%) stand out, while countries such as Costa Rica (2 cities), Paraguay (2), Cuba (1), Uruguay (1), Bolivia (1), and Italy (1) contributed more sporadically, yet still illustrate the territorial diversity reached by the initiative.

Table 1.

Number of mapped cities by country and their percentage relative to the total mapped in the project Las Calles de las Mujeres. Source: project database (2024).

Large metropolitan areas such as Madrid, Mexico City, or Lima recorded more than 3000 streets analyzed, whereas in smaller municipalities like Alaquàs, Santa Coloma deGramanet, or Chajarí, fewer than 100 streets were registered. This uneven distribution illustrates the scalability of the methodology, but also its dependence on both the degree of community involvement and the initial urban density of each city.

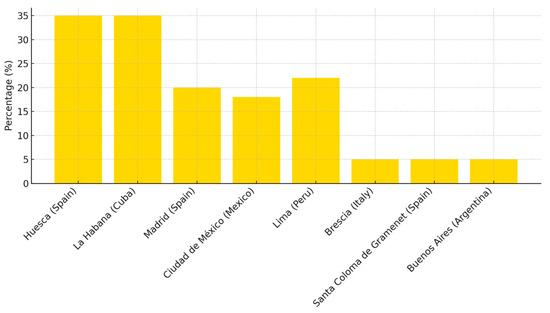

Moreover, the results reveal that differences among cities are not limited to the absolute number of mapped streets but also extend to the proportion of streets named after women (Figure 3). Cases such as Huesca (Spain) or Havana (Cuba) stand out with percentages above 35%, positioning themselves as benchmarks for the visibility of women in toponymy. At the opposite extreme, cities such as Brescia (Italy), Santa Coloma de Gramanet (Spain), or Buenos Aires (Argentina) barely reach 5%, highlighting the persistence of a significant gender gap in the symbolic construction of urban space.

Figure 3.

Percentage of streets named after women by city.

4.2. Case Study: Spanish Cities

A more detailed analysis focused on 11 Spanish cities: Badalona, Barcelona, Gijón, Girona, Huesca, Madrid, Salamanca, Santa Coloma de Gramanet, Valencia, Valladolid, and Zaragoza (Table 2). The selection is based on the fact that, out of the 13 Spanish cities included in the project, only in 11 is full and open access to all the necessary information available to conduct the analysis.

Table 2.

Road name gender disparities in Spanish cities. Source: project database (2024).

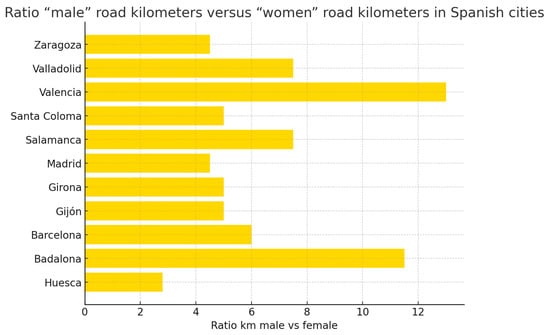

The results reveal highly unequal ratios between male and female street names, ranging from 1 km dedicated to women for every 4 to 13 km commemorating men. Madrid and Zaragoza show the smallest relative differences; however, even in these cases, for every kilometer of streets named after women, there are more than 4 honoring men.

At the opposite end, cities such as Valencia and Badalona reflect much greater disparities. Valencia represents a paradigmatic case: for every kilometer named after a woman, almost 13 commemorate men. This difference goes beyond quantity, encompassing the symbolic hierarchy and structural position of the urban network, as male streets tend to be significantly longer and to occupy more prominent locations within the city’s road structure (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Ratio of “male” road kilometers versus “women” road kilometers in Spanish cities. Source: project database (2024).

4.2.1. Average Street Length

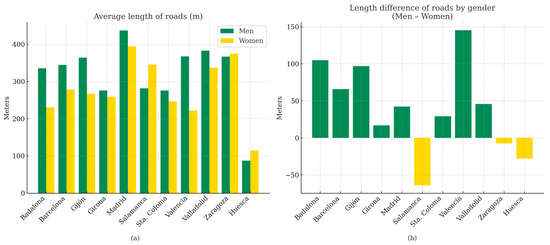

Consistent with the pattern described in Section 4.2, male-named streets are longer on average in 9 of the 11 cities. The main exception is Salamanca, where women’s streets are significantly longer. Huesca also departs from the general trend, with slightly longer female streets on average. These findings suggest that, beyond numeric underrepresentation, women are less present in the structurally prominent road segments of the urban network (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Average street length and length differences by gender in Spanish cities. (a) Average length of roads named after men and women (in meters); (b) Difference in average length between male- and female-named roads (Men–Women).

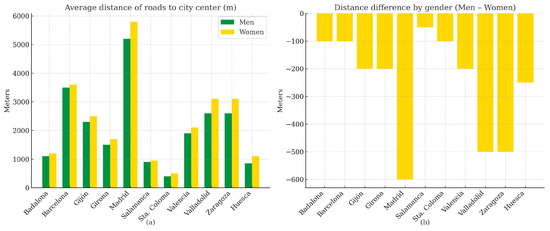

4.2.2. Distance to the Urban Center

In terms of spatial location, male-named streets tend to be closer to the city center in most cases. Exceptions include Santa Coloma de Gramanet, where women’s streets are notably closer, as well as Valladolid and Barcelona, which show smaller advantages for women. Conversely, in Madrid, Huesca, Zaragoza, Girona, and Gijón, women’s streets are located further from the center, reinforcing a peripheral pattern of recognition (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Distance of roads by gender. (a) Average distance of male- and female-named roads to the city center; (b) Difference in average distance by gender (Men–Women).

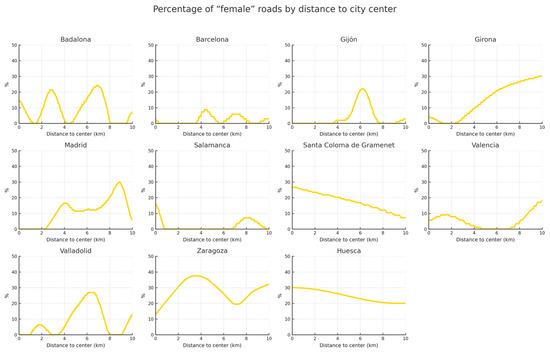

4.2.3. Proportion of Female Streets by Distance to the Urban Center

The city-by-city comparisons (Figure 7) reveal that the share of female streets often increases toward the periphery, consistent with naming practices in newer urban developments. However, this pattern is not uniform: in some municipalities, such as Santa Coloma de Gramanet and Valencia, the opposite trend is observed, indicating a strong dependence on local policies and the historical trajectories of urban growth.

Figure 7.

Percentage of roads named after women by distance to the city center in Spanish cities.

5. Discussion

The results of this study highlight the transformative role of collaborative mapping in making visible the gender imbalance that persists in urban toponymy. The project Las Calles de las Mujeres, developed within the framework of Geochicas OSM, shows how digital cartography can challenge the apparent neutrality of mainstream services by offering alternative representations of urban space. As recent media coverage has underlined, these initiatives demonstrate that maps are not merely technical instruments, but also tools of power that shape the way cities are perceived and remembered. By revealing the underrepresentation of women in street names, feminist cartography uncovers structural silences and demands a more equitable recognition of women in public space.

However, the visibility of women’s names in urban toponymy does not automatically entail a redistribution of power. As feminist and critical geographers have shown, naming is a profoundly political act through which states and institutions construct selective memories and legitimate particular social orders [11,40,41,42]. Street names materialize symbolic hierarchies and may perpetuate exclusion even when they appear to promote inclusion. In this sense, feminist cartography should interrogate not only the absence of women but also the processes, agents, and criteria that govern commemoration [43].

The example of women leaders commemorated in public space—such as Thatcher, Clinton, or Bachelet—illustrates this ambiguity: symbolic visibility can coexist with the reproduction of patriarchal or neoliberal power structures. As Tretter (2011) argues in his analysis of African American toponymy, naming operates within systems of authority that determine who is deemed worthy of remembrance and on what terms [44]. Applying this insight to gendered toponymy reveals that even progressive recognition can function within a patriarchal grammar of place-making.

From a normative standpoint, integrating a just city perspective (Fainstein, 2010) helps to reframe feminist cartography beyond symbolic correction toward procedural fairness [45]. Transparent and participatory naming policies—where communities deliberate on the values, events, or figures to be commemorated—may serve as a practical pathway to gender and social equity. In this regard, feminist mapping does not aim merely to rename, but to democratize the processes through which space, memory, and identity are inscribed in the city.

These reflections on the politics of naming extend beyond symbolic recognition to the educational realm. Understanding how urban space embodies relations of power provides a valuable framework for teaching critical spatial thinking and civic engagement. In this sense, feminist cartography not only reveals inequalities in the public sphere but also offers a pedagogical opportunity to connect geographical education with discussions of justice, memory, and participation.

From an educational perspective, the experience developed with trainee teachers in Zaragoza [1] and secondary school students in Huesca [31,32] confirms that collaborative mapping fosters spatial thinking, spatial citizenship, and critical awareness of social inequalities. Most participants were initially unaware of the magnitude of the gender gap in urban toponymy, and more than 90% did not identify this imbalance before engaging in the mapping process [1,31,32]. Through the analysis of geospatial data, students not only identified the inequality but also linked it with the broader framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). In this way, the activity enabled a shift from a general understanding of sustainability to the practical application of SDG targets and indicators in their immediate social environment.

The discussions with students also revealed significant gaps in their spatial knowledge. Most were only familiar with a few streets named after women, generally associated with central urban hubs, and only a minority could contextualize these streets within the historical growth of the city. Nevertheless, this limitation reinforces the relevance of collaborative mapping as a didactic strategy: it exposes knowledge gaps, generates debate, and provides concrete data that transform abstract goals into measurable realities. By engaging in mapping exercises, both trainee teachers and secondary students develop not only technical competencies in the use of geotechnologies but also analytical, critical, and lateral thinking skills, which are essential to address the complex urban challenges of the twenty-first century.

At the social level, the visibility generated by Las Calles de las Mujeres transcends the academic realm. The initiative has been replicated in multiple Latin American and European cities, increasing public awareness of the lack of parity in urban naming practices. In cities such as Huesca, where more than one-third of the streets named after people are dedicated to women, the project highlights positive exceptions and stimulates reflection on the policies behind toponymic decisions. Conversely, in cities with percentages as low as 5%, the cartographies act as a wake-up call for authorities and citizens to reconsider symbolic representations in public space. This duality underscores the importance of comparative and collaborative approaches, in which local specificities contribute to a global conversation on equity, citizenship, and sustainable urban development.

Beyond the empirical evidence, the results must be situated within broader theoretical debates on the social construction of the city and the hierarchies that structure urban space. These frameworks, ranging from critical urban pedagogy to decolonial perspectives, provide a lens through which feminist cartography can be interpreted. As Araguren and other authors [46,47] points out, the city as a social construction—where the material and the symbolic mutually objectify and shape each other—provides a framework that gives meaning to collective memory while also reflecting social relations, forms of citizenship, and networks of power that configure urban life. This reality underlines the need for a pedagogy of the city capable of questioning these dynamics. Similarly, as Álvarez Álvarez [48] and Curiel [49] argues, from a decolonial perspective it is necessary to go further, advocating the dismantling of multiple hierarchies of power that structure space [25]. Within this framework, cartography emerges as a critical tool for territorial interpretation and for making visible women’s experiences in contexts where their voices are often marginalized. In this line, Font-Casaseca [50] emphasizes that the cartographic process—understood as the localization of concerns—holds innovative potential because of its compatibility with feminist methodologies and its ability to give visibility and voice to excluded groups both inside and outside academia.

Several studies [46,47,48,49,50,51,52] report that urban naming practices play a central role in shaping collective identity and cultural memory. These studies highlight that the underrepresentation of women in street names and public monuments both reflects and perpetuates gendered power relations in urban space. The symbolic exclusion of women from the urban landscape is linked to broader issues of social visibility and recognition. Female-named streets are often shorter and more peripheral, and their relegation resonates with this scholarship, highlighting how urban memory reproduces gender hierarchies through toponymy.

Some studies [47,48,49,52] also emphasize the value of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and cartographic tools for both research and didactic purposes. These tools are used to visualize and analyze gender disparities in urban naming, representing a methodological innovation. According to this evidence, GIS facilitates the identification of spatial patterns and may support critical pedagogy by making gendered inequalities in the urban environment visible. However, explicit educational interventions or didactic strategies are not widely explored in the current evidence base.

The included studies document the underrepresentation and marginalization of women in urban naming and commemoration across cities in Spain and Latin America. GIS and cartographic methods are increasingly used to analyze and visualize these disparities, offering new possibilities for both research and didactic engagement. However, the translation of symbolic recognition into tangible changes in spatial appropriation and the integration of these insights into educational practice remain limited. The findings from these studies underscore the ongoing need for feminist critique and intervention in urban planning, policy, and pedagogy to construct more inclusive urban identities.

Beyond these findings, our results connect with wider debates in feminist geography and critical GIS. Scholars such as Elwood studies [53] have emphasized that participatory mapping projects can simultaneously democratize and reproduce exclusionary logics, depending on their design and inclusiveness. The experience of Geochicas OSM shows how explicitly feminist criteria in data selection—what is mapped and how it is represented—are essential to avoid reproducing androcentric biases [1,37,38]. At the same time, the critical reflection on commercial hegemonies echoes recent analyses of “data colonialism” [54], which warn about the dispossession of local knowledge through corporate platforms. In this context, feminist collaborative mapping positions itself as a counter-hegemonic practice, combining open data with community-driven values.

In urban studies, the results also align with debates on gendered geographies of public space. Research in feminist urban geography [54,55,56] has shown how the symbolic and material production of cities remains strongly gendered, shaping who is remembered, where, and under what conditions. Our evidence that female-named streets are often shorter and more peripheral resonates with this scholarship, pointing to the ways urban memory reproduces gender hierarchies through toponymy.

From the educational viewpoint, the project contributes to current discussions on geography education and the Sustainable Development Goals. As Solem and Boehm argue [57], geocapabilities and critical spatial citizenship are essential competences for twenty-first-century education. Likewise, critical pedagogy [58], of place emphasizes the transformative potential of connecting learning to local environments and social justice. In this sense, feminist collaborative mapping not only strengthens geographical competences but also provides concrete pedagogical pathways for integrating SDGs into curricula.

Despite its contributions, this study presents certain limitations. First, the quantitative focus on street naming excludes other symbolic dimensions of urban space (e.g., monuments, public facilities, or neighborhood names) that also reflect gender biases. Second, while our analysis concentrated on Spain and Latin America, further comparative research in other world regions would help contextualize the findings globally. Third, although educational case studies in Zaragoza and Huesca show strong potential, longitudinal studies are needed to assess the long-term impact of feminist mapping practices on students’ civic engagement. Future research could also examine how intersectional perspectives (gender, race, class) interact in urban toponymy and in participatory mapping practices, enriching the feminist cartographic agenda.

Overall, this discussion confirms that collaborative mapping is not only a pedagogical tool for geography education, but also a form of social activism that empowers citizens—and especially women—to claim their place in urban narratives. By combining data, visualization, and collective reflection, projects such as those presented in this article demonstrate that digital cartography can be both a vehicle for social justice and an effective tool to promote analysis, reflection, and action toward equity in urban planning, both at local and global scales.

6. Conclusions

This study confirms that collaborative mapping is a powerful tool for challenging the illusion of neutrality in digital cartography and for making visible gender inequalities in urban space. Experiences such as Las Calles de las Mujeres, developed by Geochicas OSM, demonstrate that maps are not merely technical instruments but are also political and social tools that are capable of revealing structural silences and demand greater equity in the symbolic representation of cities.

In the educational realm, the participation of trainee teachers in Zaragoza and secondary school students in Huesca illustrates the pedagogical value of feminist cartography. Through collaborative mapping, students not only acquire essential key geographical competences—such as spatial thinking and spatial citizenship— but also engage with broader frameworks of sustainability and equity. These practices create bridges between disciplinary learning and civic engagement, showing how collaborative feminist cartography can foster critical awareness, stimulate dialogue, and inspire collective responsibility among younger generations. In this sense, this approach of mapping functions simultaneously as a didactic strategy and as a transformative practice for cultivating active, reflective, and socially committed citizens [1,31,32].

In a broader context, the work of Geochicas OSM forms is part of the trajectory of feminist cartography, which, for decades, has denounced the androcentric vision of mainstream cartographic systems and promoted innovative practices of gender-sensitive data production. Projects such as the one presented in this article and others developed in different cities worldwide reaffirm the community-driven and open ethos of this approach. of this movement [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. In doing so, they stand in sharp contrast to dominant corporate platforms, whose commercial logic often erases local knowledge and obscures structural inequalities. Feminist collaborative mapping thus positions itself not only as a corrective to these exclusions but also as a generator of alternative imaginaries that place gender, equity, and collective memory at the center of spatial representation.

Our findings confirm our initial hypothesis: feminist collaborative mapping not only helps to reduce the gender gap in digital participation but also redefines what is represented on maps and how it is represented. In this sense, it constitutes a pedagogical, social, and political tool of great scope for advancing towards more inclusive and sustainable cities, consolidating geography as a key discipline in the formation of critical citizenship. As Carvalho (2021) points out, the development of critical spatial thinking is essential for recognizing the limitations of the urban environment and for promoting women’s empowerment in the construction of truly inclusive cities [59].

Looking forward, the main challenge lies in ensuring that these initiatives move beyond symbolic recognition to generate tangible, lasting transformations in urban policies and everyday practices. Strengthening the dialogue between critical scholarship, pedagogical innovation, and grassroots community engagement will be essential for consolidating feminist cartography as both a research agenda and a driver of social change, allowing women to overcome obstacles in mapping to make significant global contributions [59,60]. Future efforts should aim not only to make women visible in urban toponymy but also to reshape the very logics through which cities are conceived, governed, and experienced. By doing so, collaborative mapping can contribute not only to making women visible in urban toponymy, but also to reshaping the very logics through which cities are produced, inhabited, and remembered.

Ultimately, feminist cartography is not a descriptive but a transformative practice. It makes visible gendered absences while exposing the dynamics that shape spatial recognition and participation. By combining open data, community collaboration, and critical pedagogy, feminist collaborative mapping reclaims the map as an act of epistemic justice—transforming visibility into agency and linking knowledge production with social change.

Author Contributions

M.S.L.: conceptualization, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, investigation, project administration, and active member of Geochicas OSM; O.K. and R.D.M.G.: data processing, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; J.A.M.D. and J.M.-B.: investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the project “Digital maps in the classroom: innovation in the learning of geographical competencies through eye-tracking techniques” (code PID2024-155735OB-I00), funded by the State Research Agency. Additionally, Juan Mar-Beguería is supported by a predoctoral grant financed by the University of Zaragoza (code PI-PRD-001/2023). The authors are members of the ARGOS research group (S50_23R, Government of Aragon 2023–2025) and the University Research Institute for Environmental Sciences of Aragon (IUCA) at the University of Zaragoza, whose work is part of the cross-cutting theme Education for Sustainable Development.

Data Availability Statement

Data that support the findings of this study are openly available on websites: https://github.com/geochicasosm/lascallesdelasmujeres.git, https://geochicasosm.github.io/lascallesdelasmujeres/ (all accessed on 31 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the GeoChicas OSM geospatial communities (especially Carmen Diez, Jessica Sena, and María Zuñiga) for their contribution to the collaborative mapping workshop and for making us part of this wonderful community. We are also deeply grateful to Lorenzo Mur for bringing this project to life in the classroom and for incorporating these didactic strategies into his teaching practice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- De Miguel, R.; Sebastián-López, M. Education on Sustainable Development Goals: Geographical Perspectives for Gender Equality in Sustainable Cities and Communities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Z.; Mooney, P.; De Sabbata, S.; Dowthwaite, L. Quantifying Gendered Participation in OpenStreetMap: Responding to Theories of Female (Under) Representation in Crowdsourced Mapping. GeoJournal 2020, 85, 1603–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikara Magazine. Machismo y Medios: Lo Peor de 2020. Available online: https://www.pikaramagazine.com/2020/12/machismo-y-medios-lo-peor-de-2020/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Undark. Feminist Maps Are Helping Latin American Women Transform Public Spaces. Undark Magazine, 17 July 2019. Available online: https://undark.org/2019/07/17/feminist-maps-latin-america/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Kwan, M.P. Feminist Visualization: Re-envisioning GIS as a Method in Feminist Geographic Research. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2002, 92, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovskaya, M.; Martin, K. Feminism and Geographic Information Systems: From a Missing Object to a Mapping Subject. Geogr. Compass 2007, 1, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Feminism and Geography; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Young, C. HarassMap: Using Crowd-Sourced Data to Map Sexual Harassment in Egypt. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2014, 4, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. Space, Place and Gender; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, L. Gender, Identity and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies; Polity Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Redwood, R. From number to name: Symbolic capital, places of memory and the politics of street renaming in New York City. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2008, 9, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.M. Justice and the Politics of Difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist” Condition; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.; Knopp, L. Queering the Map: The Productive Tensions of Colliding Epistemologies. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2008, 98, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Thorsen, S. Data feminism in action: Mapping Urban Belonging in Copenhagen with experimental visualization and participatory GIS. Gend. Place Cult. 2024, 32, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ignazio, C.; Klein, L.F. Data Feminism; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollaz Morán, A. Embodied Urban Cartographies: Women’s Daily Trajectories on Public Transportation in Guadalajara, Mexico. In Feminist Methodologies; Harcourt, W., van den Berg, K., Dupuis, C., Gaybor, J., Eds.; Gender, Development and Social Change; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M. Mapping Bodies, Designing Feminist Icons. GeoHumanities 2021, 7, 529–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckett, T.; Bagelman, J. Body mapping: Feminist-activist geographies in practice. Cult. Geogr. 2023, 30, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prutzer, E. Mapping pedagogies: Applying cartographic practice to the public sphere. Learn. Media Technol. 2022, 47, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzaldúa, G. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza; Aunt Lute Books: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Collins, P. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Routledge: New York, UK, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- González, M. Geochicas, Improving How Open Mapping Represents the World. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geochicas OSM. Las Calles de Las Mujeres. Available online: https://github.com/geochicasosm/lascallesdelasmujeres (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Proyecto Yo te Nombro. Available online: https://mapafeminicidios.blogspot.com/p/inicio.html (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- El País. Los Mapas Creados Por Mujeres Que Desafían el Poder de Google Maps. El País América Futura, 10 March 2025. Available online: https://elpais.com/america-futura/2025-03-10/los-mapas-creados-por-mujeres-que-desafian-el-poder-de-google-maps.html (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Robinson, A.H. Rectangular World Maps—No! The Professional Geographer; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1990; Volume 42, pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur Sangrá, L.; Sebastián López, M.; Mérida Donoso, J.A.; De Miguel González, R.; González González, J.M.; Kratochvil, O. La investigación didáctica del callejero urbano de Huesca: El proyecto Geochicas. Doss. Graó 2024, 16, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián López, M.; Kratochvíl, O.; De Miguel González, R. Geographic Education and Spatial Citizenship: Collaborative Mapping for Learning the Local Environment in a Global Context. In Revisioning Geography; Klonari, A., De Lázaro y Torres, M.L., Kizos, A., Eds.; Key Challenges in Geography; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B. Promoting Geography for Sustainability. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F. An (Other) Geographical Critique of Development and SDGs. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2018, 8, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Otero, J.; De Miguel-González, R.; Sebastián-López, M. El diseño participativo: Un enfoque innovador para la educación geográfica en las aulas de Secundaria. Ens. Rev. Fac. Educ. Albacete 2024, 39, 1–18. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/10067464.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Zúñiga Antón, M.; Sebastián-López, M.; De Miguel González, R.; Pueyo Campos, Á. Creating Public Opinion and Developing Spatial Citizenship through Maps: The Case of Zaragoza, Spain. Eur. J. Geogr. 2017, 8, 62–76. Available online: https://eurogeojournal.eu/index.php/egj/article/view/319 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Haklay, M.; Budhathoki, N. The Gendered Geography of Contribution to OpenStreetMap; UCL Working Paper Series; University College London: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián, M.; De Miguel, R. Mobile Learning for Sustainable Development and Environmental Teacher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczynski, A.; Elwood, S. Feminist Geographies of New Spatial Media. Can. Geogr. 2015, 59, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, D. Las ambigüedades cartográficas de los mapas. Rev. Crítica Cart. 2019, 7, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Azaryahu, M. The power of commemorative street names. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1996, 14, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, L.D.; Vuolteenaho, J. (Eds.) Critical Toponymies: The Contested Politics of Place Naming; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, J.B. Deconstructing the map. Cartogr. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovisualization 1989, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretter, E.M. The power of naming: The toponymic geographies of commemorated African-Americans. Prof. Geogr. 2011, 63, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S.S. The Just City; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aranguren, C. La ciudad como objeto de conocimiento y enseñanza en las ciencias sociales. Fermentum. Rev. Venez. Sociol. Antropol. 2000, 10, 539–550. [Google Scholar]

- Milenio. Congreso Internacional de Cartografía Feminista: Debates y Aportaciones. Milenio, 8 September 2018. Available online: https://www.revistadelauniversidad.mx/articles/21a6cb3c-d651-45cd-b8e6-49d3c46b2390/subvertir-la-cartografia-para-la-liberacion (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Álvarez Álvarez, S. Aproximación metodológica con Sistemas de Información Geográfica (SIG) en reivindicaciones feministas en La Araucanía (Chile). Investig. Geográficas 2023, 66, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, O. La descolonización desde una propuesta feminista crítica. In Descolonización y Despatriarcalización de y Desde Los Feminismos de Abya Yala; Curiel, O., Galindo, M., Eds.; ACSUR-Las Segovias: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; pp. 11–25. Available online: https://suds.cat/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Descolonizacion-y-despatriarcalizacion.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Font-Casaseca, N. Prácticas cartográficas para una geografía feminista: Los mapas como herramientas críticas. Doc. D’anàlisi Geogràfica 2020, 66, 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares Rodríguez, L. Análisis de género en el distrito centro de la ciudad de Málaga. Avanzando a una odonimia feminista. Tercio Creciente 2022, 23, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Sánchez, G.; Marfil-Carmona, R. La imagen de la mujer en el patrimonio urbano de Granada. El espacio público de la ciudad como «escenario comunicativo». aDRes. ESIC Int. J. Commun. Res. 2020, 22, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwood, S. Negotiating knowledge production: The everyday inclusions, exclusions, and contradictions of participatory GIS research. Prof. Geogr. 2006, 58, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, J.; Berg, L.D.; O’Sullivan, D. Data colonialism through accumulation by dispossession: New metaphors for daily data. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2016, 34, 990–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, L.; Rose, D. Constructing gender, constructing the urban: A review of Anglo-American feminist urban geography. Gend. Place Cult. 2003, 10, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, L. Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World; Verso: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Solem, M.N.; Boehm, R.G. Transformative research in geography education: The role of a research coordination network. Prof. Geogr. 2017, 70, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenewald, D.A. The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educ. Res. 2003, 32, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, I.C. Critical spatial thinking in women’s resilience for an inclusive city. J. Adv. Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 4, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI. Women and GIS: Mapping Their Stories; Esri Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.esri.com/content/dam/esrisites/en-us/esri-press/book-pages/sample-page/women-gis-mapping-their-stories.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).