1. Introduction

Planning support systems (PSS) are one of the different types of spatial decision support (SDS) tools adopted in planning [

1]. Studies show that PSS integrate users’ knowledge of planning tasks and processes, spatial and non-spatial data, as well as methodologies or technologies that combine such knowledge and data to support decision-making in the planning process [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The integration of such knowledge, data, and methodologies produces a heterogeneity of “actants” depending on PSS development, implementation, use in planning activities, or existing planning processes [

2,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

This paper uses “actants” to represent the heterogeneity of PSS actors. Drawing on Latour [

13,

14], we define “actants” as human and non-human (technical and non-technical) actors or a source of action. Some PSS studies investigated actants’ capabilities and compatibilities to explain PSS implementation outcomes [

5,

6,

8,

15,

16,

17], while other studies distinguished actants’ characteristics and roles to explain these outcomes [

2,

10,

18]. However, over three decades of research have never conceptualized PSS implementation as its institutionalization in the planning process. In this paper, institutionalization is the embedding and acceptance of new practices (e.g., PSS use in the planning process) as a necessity [

19]. The planning process is an interactive and iterative activity that integrates digital technologies to enhance collaboration among planners and stakeholders [

8].

Vonk [

12] identified challenges with PSS use, and he recognized a gap between PSS use and its institutionalization in planning practice. Still, studies continue to follow reductionist accounts that describe PSS use simply in terms of PSS usage (limited or continuous) based on PSS fit to planning tasks, user acceptance, or deterministic policy mandates of planning processes [

11,

20,

21,

22]. To date, conceptualizing PSS implementation as an institutionalized part of the planning process is a gap in planning research and practice. Tackling this gap requires looking into a PSS case study from its implementation to understand the complexities of heterogeneous actants associations, improvisations, negotiations, and shifting alliances that better explain how PSS institutionalization in the planning process happens. Developing and implementing an approach that can investigate these complexities are the focus of this article.

There are studies about other types of SDS institutionalization in planning processes. Such studies mainly focus on institutionalizing geographic information systems (GIS) and spatial decision support systems (SDSS) or technologies [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. A generalized finding from the studies is that institutionalization is shaped by the roles and actions of human actants (users and developers), with influence from non-human actants (technology, policies, tasks, and politics) involved in practice. While studies that utilize or recommend understanding an institutionalist approach to describe the processes involved in PSS use [

2,

9,

28] exist, such studies omit reporting on the complexities of the human and non-human actants’ associations, producing negotiations and interactions that provide insight into processes of translations or PSS institutionalization. The novelty of this study lies in the development and implementation of an analytic approach that traces and documents the omitted perspectives in existing PSS research. Nevertheless, we first discuss institutionalization in the context of this article.

Institutionalization produces common (

taken-for-granted) knowledge about what is accepted as an established everyday practice [

19,

29]. It happens when actions and agencies of human actants are repeatable by other human actants to reproduce established practices. According to Zucker, institutionalization happens at varying levels and extents depending on the actants’ actions and agencies [

19,

29]. This research defines PSS implementation as its application or use [

30] and PSS institutionalization as a continuous process of embedding PSS as an established practice in planning processes [

31]. It should be noted that this research differentiates between PSS institutionalization in planning processes and PSS institutionalization in planning organizations. PSS institutionalization in planning processes can happen via policy or project intervention without constitutional change(s) in the organizational planning framework. Meanwhile, PSS institutionalization in planning organizations will require constitutional change(s) establishing PSS as a statutory part of all organizational planning processes. Hence, this research is about PSS institutionalization in planning processes.

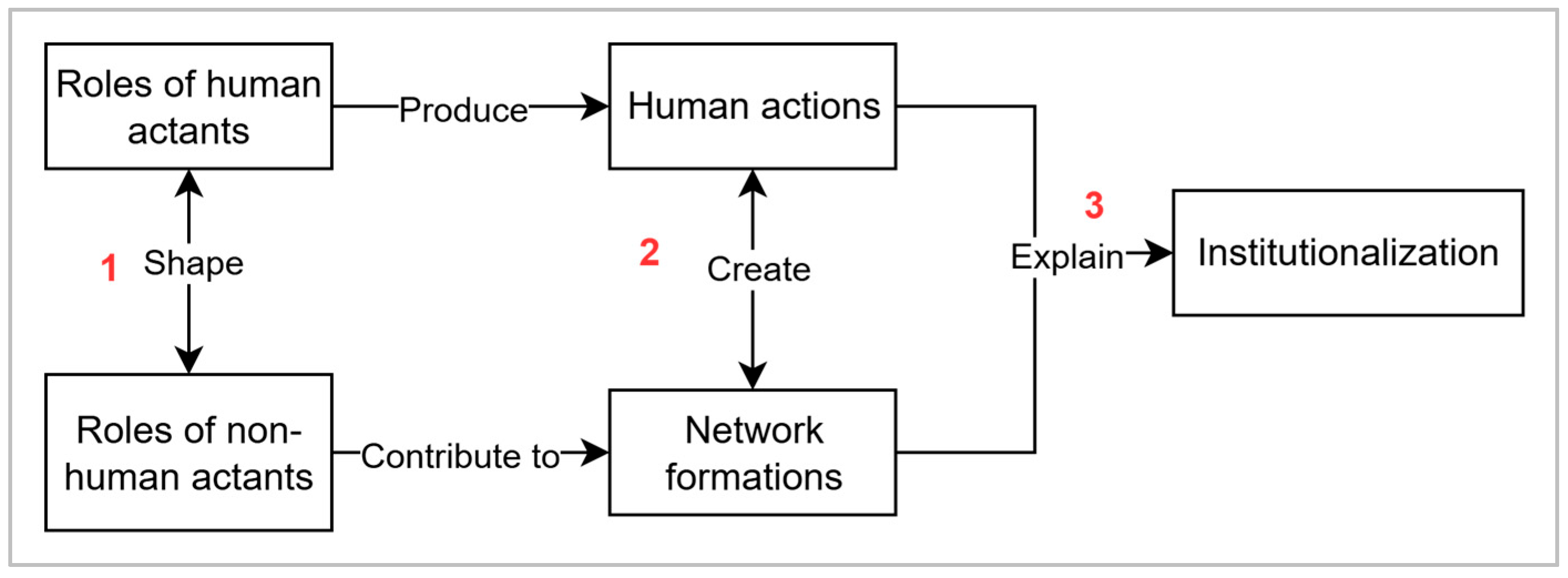

This research assumes that understanding actants’ typologies, actions, roles, and networks involved in PSS implementation and use provides better insight into its institutionalization. We investigate this assumption by asking, “

How, to what extent and why PSS institutionalization happens in the planning process?” In answering the question, this research focuses on three components shown in

Figure 1 as follows: (1) the actants, (2) how actants act or are sources of decisions for network formations, and (3) the actions that explain PSS institutionalization. This research is an exploratory inquiry to (a) present an analytic framework to investigate and explain PSS institutionalization in planning processes and (b) contribute to knowledge on how to better strategize PSS institutionalization to PSS research or practice.

The PSS case study is the Spatial Development Framework methodology (the SDF-PSS) developed in 2011 [

32,

33]. The SDF-PSS methodology supports spatial analyses of settlements for classifications according to hierarchies and infrastructure needs, which has enhanced resource allocation for social, physical, and economic planning in some countries [

32]. As of 2024, the SDF-PSS has been implemented in over nineteen countries across the Global South, demonstrating its broad adaptability, scalability, and relevance to diverse development contexts. Among the nineteen countries, Rwanda has served as a real-world laboratory for the SDF-PSS use from its first implementation in 2015 as a policy implementation methodology to its continuous use in various parts of the country’s planning processes. Rwanda’s case illustrates how the repeated and evolving use of SDF-PSS in diverse planning tasks contributes to spatial planning. The choice of Rwanda as a case study stems from its high relevance for research agendas focused on institutionalizing planning technologies [

8], particularly within the rapidly changing contexts across the Global South.

In Rwanda, under the auspices of the Ministry of Infrastructure (MININFRA), the SDF-PSS was first implemented in 2015–2016 to complement the implementation and spatialization of a national policy document [

33,

34,

35]. The SDF-PSS supported the descriptive identification of the functional hierarchy of settlements across the country and the prescriptive spatial evaluation of the Rwandan territory in terms of four policy objectives of the National Urbanization Policy [

33]. Then, between 2019 and 2020, the functional hierarchy of the Rwandan settlements was described for spatial strategies for industrial planning and development to support decision-makers in the planning process [

36]. Since 2021, MININFRA has sought to institutionalize the SDF-PSS for local planning processes by decentralizing it as a web-based GIS dashboard to support collaborative planning—the Urban Dynamic Mapping (UDM) dashboard. Such web-based GIS dashboards and maptables are known to support collaborative spatial planning among various stakeholders [

37,

38]. Hence, for eight years (2023) and counting, the SDF-PSS has been used in parts of the planning process in Rwanda to enhance collaborative and participatory processes.

Several studies about the SDF-PSS inform this research. First, there is a study on SDF-PSS’s contributions to the spatial implementation of the urbanization policy in Rwanda [

33]. The second introduces its components, capabilities, and potential for continuous use as a PSS for various countries such as Sudan and Rwanda [

32]. The third study discusses the SDF-PSS’s use for policy interpretation from national objectives into spatial realities at local levels and its potential for Rwanda’s planning process [

35]. The fourth one argues that it is crucial to identify and implement unplanned changes during the SDF-PSS implementation for its integration into the planning process [

39]. However, the institutionalization of the SDF-PSS into a part of the Rwandan planning process has not been investigated. This research emphasizes that studies describing PSS’s post-implementation outcomes in terms of use differ from studies designed to investigate and explain PSS institutionalization in practice. It advances the knowledge about PSS institutionalization by explaining what shapes the SDF-PSS institutionalization in parts of Rwanda’s planning process.

2. Analytical Framework

Rather than investigating PSS institutionalization with Vonk’s [

12] technology task user-fit approaches, this study asserts that PSS implementation differs from its institutionalization and utilizes the translation approach to explain PSS institutionalization. Translation is the actants’ continuous interpretation of actions as network(s) formations across specific spatial or temporal contexts [

40]. Tracing of actants’ interpretation(s) is made possible by observing sources of negotiations, trade-offs, agreements, choices among varying preferences, and decisions aiding actions that shape translations. Callon and Latour [

40] asserted that translations from actants’ actions to networks are black boxes and tracing such translations provides insight into network formations leading or not to institutionalization. In 1984, Callon established translation as a process that happens over time and cannot be described as success or failure [

41]. He developed an analytical method to trace the black box of translation—the sociology of translation (SoT).

For this article, PSS translation is its continuous use as (re)developed systems for users or planning tasks requirements at different moments to become an institutionalized PSS adaptable for various users and planning tasks [

40]. PSS use happens at varying translation moments across time and space. This paper posits that investigating the association of actions that describe networks of varying actants provides better insights into how PSS institutionalization does or does not happen. Such insights are better than portraying PSS post-implementation outcomes in planning practice as PSS use or limited use. Hence, we adopt SoT as a framework for classifying different translations that explain institutionalization and implement the “actor–network” as a methodology for tracing involved actants [

42].

The Sociology of Translation (SoT)

The sociology of translation (SoT) adopts agnosticism, generalized symmetry, and free association principles. Agnosticism is an impartiality of interpretations. It encourages that predefined definitions of roles or actions of actants’ are not adopted to censor or enhance interpretations of translation moments. Instead, tracing and presenting an unbiased account of network formations is vital. Generalized symmetry is a commitment to explain conflicting accounts in simple terms. It utilizes common concepts to explain network properties from actants’ heterogeneity and actions. Free association is a rejection of predefined distinctions of actants. It eliminates group or restricted explanations and replaces them with descriptions of how actants produce networks through different associations [

41]. With these principles, SoT helps describe details of translations and network formations with four moments—problematization, interessement, enrollment, and mobilization. The characteristics of SoT moments are as follows:

Problematization is where the definition of actants and potential common interests happen. It stimulates relations among actants from interrelated tasks to be achieved or challenges to be resolved. Here, human actants are convinced to agree on a proposed non-human actant solution for a task (challenge) as a possible solution for others. A consensus of human actants is required to execute the proposed solution, an actant of itself with underlying actant–network(s), and initiated by an obligatory passage point (OPP). OPP describes the human or non-human actant(s) whose role(s) and action(s) help initiate the agency of actants that define network formations across translation moments. Interessement occurs when actions of crucial actant(s) attract or tie other actants to a network through decisions and actions that connect or change a cause of action from the problematization moment. It confirms the status of the network built on the OPP and the alliances created by actants’ actions by locking (displacing) actants in the network. Enrollment describes adopted approaches to enroll more actants that create, change, or (dis)connect network(s) of translations. It focuses on actants’ actions, roles, and agencies that engage more actants in the translation network(s). Mobilization identifies a representative (spokesactant(s)) and narrates who they represent during translation moments to describe network(s) status. It helps explain institutionalization across translation moments.

Callon [

41] describes a spokesactant as any actor (human or non-human) that represents and speaks for others within a given network of actors’ associations. A spokesactant can represent a group of actors, can speak or enhance actions that shape the actions of the group(s) it represents through the alignment of actors and actions (translations). Sometimes, a spokesactant can transform the interests and identities of those it represents to become an OPP to enroll other actors into a network.

In 1986, Michel Callon built on Bruno Latour’s work [

43] and developed a methodology called “actor–network” [

42]. Callon described that the actor–network identifies actants’ heterogeneity and allows to ‘

follow the actants’ across the four moments of SoT. In 1992, John Law harmonized the works of twelve researchers (including himself, Callon, and Latour) at the center for the Sociology of Innovation to coin the term actor–network theory (ANT) [

44]. Law [

44] stated that ANT, like SoT, describes a network as a composition of actants (human, non-human). Callon and Latour later clarified that ANT is not a theory like SoT but a methodology built on SoT principles to investigate what actants do (actions), how, and why they execute the actions [

45,

46]. As a methodology, ANT explores an impartial representation of actants, actions, roles, agencies, and network formations to describe translation moments [

46]. This research adopts ANT as an analytic methodology to operationalize SoT, building on Bruno Latour’s details about ANT as a methodology [

14]. The choice of ANT builds on its identity as a methodology for tracing translations and is the same as SoT [

14,

44,

45,

46].

3. Methods

In order to understand PSS institutionalization in the planning process, this research adopted ethnographic methods for qualitative data collection (participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and collection of texts) and analyses (transcriptions, document analysis, and qualitative data analysis/coding). There are two rationales for choosing these methods. First, the nature of obtained data from “

following the actants” on flat terrains ensures that irrespective of actants’ classifications, they are made visible with equal status as individuals and collectives, human and non-human, during network formations across the four moments of translations [

14]. It helps provide insights into relations among actants’ actions, roles, and agencies. Second, to avoid portraying research findings as a conclusion (success or failure). This research presents findings as a process that happens at varying levels or extents of PSS institutionalization in the planning process. The research methods facilitate the operationalization of the sociology of translation (SoT) principles across four translation moments with the actor–network theory (ANT).

ANT’s strength as a methodology stands on its flat terrain that embodies the phrase—“

follow the actants” [

14,

42]. Following the actants enables us to investigate the evolution of actants’ actions, roles, and agencies to understand what happens across translation moments, how, and why. However, Latour mentioned a fourth principle, apart from agnosticism, generalized symmetry, and free association, that is required to operationalize ANT as a methodology—

controversies. Latour [

14] described controversies as sources of errors that must be considered before commencing a “

follow the actants” tracing of associations. Latour’s five sources of controversies are stated in

Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials. This table’s columns (a) itemize the sources of controversies, (b) describe the actants’ role, and (c) provide an example from Rwanda’s SDF-PSS context. Combining the four principles aided data processing and analysis of Rwanda’s SDF-PSS institutionalization from 2015 to 2023.

Primary data sources include a one-day participant observation of the SDF-PSS decentralization training, semi-structured interviews with sixteen respondents, and field notes from a one-month fieldwork in Rwanda in February 2023. The duration of each semi-structured interview ranges between thirty minutes and an hour, depending on the participant’s preference. However, for fact-checking or data validation purposes, there were instances where one or two follow-up sessions were conducted with some respondents. Field notes contained descriptive observations during daily interactions and visits to individuals and organizations throughout the fieldwork period. Such observations prompted many instant conversations and data verifications that became additional data sources added to field notes. During the one-day participant observation, written field notes include details about participants, their roles, interactions, additional reference materials or specific data sources provided by trainers, and potential interview questions from participants’ discussions. Also, field notes documented interview contexts, non-verbal communications, follow-up questions based on the interviewee’s responses or comments, additional reference materials, and referrals.

During data collection, interviews were transcribed and coded immediately after completion to recognize when additional referral interviews did not yield new data and codes relevant to the research question. Data saturation was observed after fourteen respondents; however, two more respondents were interviewed to ascertain saturation and completeness of data for interpretation. While approximately one hundred individuals were involved across the different phases of the SDF-PSS project between 2015 and 2023 (in development, decision-making, implementation, training, and workshops), those directly engaged in using SDF-PSS within actual planning processes represent a much smaller group. A snowball sampling strategy was employed to ensure comprehensive representation of participants across the project’s phases. Interviewee recruitment commenced with meeting key individuals who had been actively involved in SDF-PSS from its inception and who constituted the initial sample. These participants identified additional respondents with relevant experience in different project stages through a chain-referral process. This approach included core project personnel and end-users with practical, hands-on engagement with SDF-PSS in planning contexts. Also, participation was entirely voluntary, and interviewees provided informed consent. The

Supplementary Materials (Table S2) shows the respondents’ selection and criteria. Semi-structured interviews revolved around interviewees’ experience with the SDF-PSS implementation at the national or local level planning processes. The interview topics were emailed to respondents with appointment requests, which aided appointment confirmations, and respondents prepared for interviews or gave referrals when appropriate.

Although not with the aim of writing this paper, the 1st author already engaged with several actors and participant observations in January–March 2020, online and in-person interviews in 2022 [

47], and the 2nd author did so in the two SDF implementation projects mentioned earlier. Secondary data from archived materials and documents from individuals and organizations were utilized, including press archives, public websites, policies, laws, and regulations.

Data processing and analyses included manual and software-aided methods. Manual processing was performed by close reading, note-taking, and text extractions from primary and secondary data (documents, field notes, sketches, images, and recordings). Extracted text from transcripts was categorized into two groups to narrate the SDF-PSS translation moments using descriptive and interpretive codes. Descriptive codes are phrases or words that represent quote(s) about actants and their roles (e.g., responsibilities, project funding, and available resources). Interpretive codes describe actions or processes during the translation moments (e.g., the decision to adopt the SDF-PSS, proposal development for the SDF-PSS decentralization, and annual plan development). Software-aided data processing was performed with audio-record transcription using AmberScript “

https://www.amberscript.com/en/ (accessed on 10 October 2025)” and code developments using ATLAS.ti Versions 23.3.0 to 25.0.1 “

https://atlasti.com/updates (accessed on 10 October 2025)”. Software-aided analysis was performed using code grouping and theme development in ATLAS.ti. In the

Supplementary Materials,

Figure S1 illustrates the adopted qualitative approach, and

Table S2 contains an overview of data collection, processing, and analysis. It describes data types, sources, processes, analyses, and results that describe how actants’ associations explain PSS institutionalization. For this study, the principal investigator (the first author) primarily collected, interpreted, and analyzed data, with periodic consultation from co-authors to discuss emerging themes and validate interpretations.

For a definition of adopted ANT concepts for this research, see

Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials. The concepts aided in following the actants on flat terrains of network formations across the translation moments and presenting an empirical basis for writing an unbiased ANT account in the Results section.

4. Results

Here, we present our findings to answer the research question “How, to what extent and why PSS institutionalization happens in the planning process?” following the four sociology of translation moments—problematization, interessement, enrollment, and mobilization. We describe associations among actants’ roles and actions that create agencies of actant–network(s) that have shaped the Spatial Development Framework (SDF-PSS) methodology institutionalization since 2015. Results establish our research assertions that (a) PSS implementation differs from its institutionalization and (b) the translation approach from sociology can explain PSS institutionalization. In the

Supplementary Materials,

Table S4 shows interview questions that guided the semi-structured interviews, the focus of such questions for each translation moment, and produced data that guide results detailed in

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2,

Section 4.3 and

Section 4.4.

4.1. Problematization

Problematization focused on how the SDF-PSS was introduced into the country’s planning process and specified the actant that initiated its adoption in practice—the “obligatory passage point” (OPP).

In 2000, the government of Rwanda developed a Vision 2020 to transform the country into an urbanized middle-income economy competitive at the global and regional levels by 2024 [

48]. One of the Vision’s objectives was to mitigate the rural–urban population influx and utilize it as an engine of growth for Rwanda’s transformation. The envisioned transformations led to the development of sector-specific policies and strategies for implementation across the country. Through the ministry in charge of urbanization and infrastructure development (Ministry of Infrastructure (MININFRA)), UN-Habitat proposed developing a National Urbanization Policy (NUP) to tackle the increase in rural–urban influx in Rwanda. During the NUP proposal presentation to the Rwandan cabinet in 2014, MININFRA’s Minister raised an issue: the lack of a spatial implementation methodology for existing policies and strategies. This lack limits the achievements of national policies and strategies developed to guide envisioned spatial transformations, especially at the local levels.

The NUP presenter from UN-Habitat recounted that the Minister said, “I am not sure we need your policy; another piece of paper (policy) to be on the shelf. What I need to know is how do I connect city A with city B? how do I develop them.”

The NUP presenter stated, “I was listening to the minister and believe me, it was pure improvisation, and I said, honorable minister, I had prepared a presentation for you, but hearing you talk, let me show you this work we did in Darfur. And I just opened the Darfur presentation with the SDF; … I had just 10 min.” Describing how this improvisation answered the Minister’s question, he continued, “The minister looked at me, and he said, you know, what you presented, this is what I want. So, you have next week, … I want you in one week to prepare the TORs for Rwanda and I am going to fund you.”

According to the narrated events, the minister perceived the SDF-PSS as a methodology that “

could similarly be used to give hands and feet” to the spatial implementation of the NUP [

33].

Figure S2 in the Supplementary Materials illustrates connections among actants, roles, actions, and agency formations involved in the problematization moment. For more details about the actants’ roles, actions, and agencies that defined the first translation moment, see

Table S5 in the Supplementary Materials.

Generalizing lessons from the SDF-PSS Problematization, we answer, “How, to what extent and why PSS institutionalization happens in the planning process?”. First, the PSS institutionalization commenced with an actant’s quest to find a spatial implementation methodology for the country’s policies and strategies. A prompt improvisation from another actant that presented achievements of an adopted PSS as a spatial implementation methodology in another country led to a decision to adopt the PSS as a possible solution and its inclusion as a policy action to implement a sectoral policy for urbanization. Second, the extent of PSS institutionalization was limited to a part of the planning process, the urbanization process. Lastly, the observed PSS institutionalization was built on the government’s interest in achieving national policy goals of transforming the country into an urbanized economy competitive at the regional and global levels.

4.2. Interessement

Interessement describes processes involved in the SDF-PSS’s use as a PSS for the NUP and parts of the planning process. It narrates how actants and actions define the connection of new actants into a predefined network involved in the SDF-PSS institutionalization.

The NUP promoted the use of appropriate tools for urban planning and management. It identified the SDF-PSS as a spatial methodology for complementing existing planning processes [

34]. The SDF-PSS complements planning processes in three ways [

32]. First, it enhances the spatial analyses of territories and allocation of available resources. Second, it supports hierarchies of settlements across territories with the allocation of required infrastructure economic activities. Third, it enhances the efficient use of available resources according to spatial characteristics across the country to boost economic transformation. After the problematization moment, mandatory instruction and budget allocation for PSS use in the planning process was included in the NUP. The mandatory instruction was interpreted through two policy actions. One is the choice of the SDF-PSS that supports the country’s planning process and economic transformation; the second is establishing a geospatial data platform to support the SDF-PSS use [

40]. MININFRA has been coordinating the NUP implementation and collaborating with other stakeholders to achieve the actions through its Department of Urbanization, Human Settlement, and Housing Development (MININFRA-UHSHD). The SDF-PSS development and use led to actions and role definitions that connected other actants and modified the problematization actant–network, see

Table 1.

During the interessement, MININFRA-UHSHD became the OPP that engaged other actants from the national and local levels to strengthen the SDF-PSS actant–network as shown in

Figure S3 in the Supplementary Materials). The actants’ connections altered the initially stabilized actant–network problematization into an agency within the interessement actant–network. The NSAP aims to integrate spatial components in economic planning, monitoring, and budgeting at all levels of the planning process.

An overview of “How, to what extent and why PSS institutionalization happens in the planning process?” during the interessement is as follows. The government’s decision to approve and fund a policy that mandated PSS use explained how its institutionalization in the planning process was possible. While the PSS implementations aided spatial planning activities across territories, its extent of institutionalization in the planning process remains limited to a small part. The reason for constraints in its institutionalization extent was that involving more actants in PSS use does not necessarily enhance PSS institutionalization. However, involving the right actant(s) in charge of the country’s planning process in the PSS use enhances PSS institutionalization.

4.3. Enrollment

Enrollment describes adopted approaches to enroll actants that create, change, or (dis)connect network(s) of translations. Here, we focus on how the SDF-PSS’s acceptance as a spatial methodology for policy implementation helps moderate actants enrollment to support planning processes addressing urbanization challenges.

The cabinet’s approval of the NUP allows the SDF-PSS to support the Rwanda planning process. The technical validation of the SDF-PSS contributions to spatial planning in Rwanda was documented during the consultative workshop held with government representatives and other partners [

32]. The potential of the SDF-PSS for policy implementation at local levels was explored with two case studies (Rubavu and Musanze) in Rwanda [

35]. The SDF-PSS was established in MININFRA-UHSHD as a decision room (for situation analysis) with spatial evaluation capabilities of policies for recommendations on (a) funding of annual planning proposals to MINECOFIN, (b) implementation strategies to the local levels, and (c) policy priority areas for financial investments in Rwanda [

36]. The SDF-PSS capabilities have stabilized the actant–network since 2015—a spatial methodology to spatially implement policies (problematization). Since then, MININFRA-UHSHD explored ways to enhance the SDF-PSS as a spatial methodology for planning processes at the national and local levels through project partnerships.

The Belgian–Rwandan collaboration for boosting urban infrastructure and supporting economic transformation in selected cities in 2020 was one such project. The Belgian development agency Enabel partnered with MININFRA’s department (MININFRA-UHSHD) and one of its agencies—Rwanda Housing Authority (RHA)—in a project called the Urban Economic Development Initiative (UEDi). UEDi is a five-year project partnership with three local level districts (Musanze, Rubavu, and Rwamagana). The project involved other national agencies coordinating local planning, i.e., the Ministry of Local Government (MINALOC) and the Local Administrative Entities Development Agency (LODA). Aside from urban development projects, UEDi has provided capacity development on the use of GIS technology to support technical staff at the local levels. Such training contributes to technical staff capabilities to use the SDF-PSS for planning processes at the local levels. The project included the appointment of an SDF expert as a staff member of MININFRA-UHSHD for four years.

Another project commenced in 2021 when MININFRA-UHSHD utilized a common pillar action of the NUP and Smart City MasterPlan (SCMP) to develop a proposal for the SDF-PSS decentralization known as the Urban Dynamic Map (UDM) dashboard project [

49]. Funding was from a Wehubit call (a program under Enabel) called “

Resilient cities: towards inclusive and sustainable urban development.” The Wehubit grant resulted in funding for pilot projects in two local level districts (Muhanga and Bugesera). Also, Enabel provided funding to include the three UEDi districts (Musanze, Rubavu, and Rwamagana) in the project. The UDM dashboard was developed as a web-based geographic information system (GIS) using the ArcGIS platform to incorporate spatial data from another GIS tool (ArcGIS Survey 123) and field maps, including non-spatial records from statistical data, reports, or spreadsheets for collection and processing. The relation of the SDF-PSS to UDM is that while the SDF-PSS is situated as a decision room at MININFRA-UHSHD, its decentralization to other national and local level agencies is achievable with the UDM dashboard installation, which explains agencies of enrollment with actants’ roles and actions as described in

Table S6 of the Supplementary Materials.

So, “How, to what extent and why PSS institutionalization happens in the planning process?” The PSS institutionalization continued with the help of specific actants who explored ways to expand PSS use as a spatial planning methodology at all levels of planning. Regardless of the engagement of more actants from the national and local levels in PSS use, five years after its initial use, PSS institutionalization remains limited to the same minor part of the planning process. It suggests that if the actant in charge of both PSS use and institutionalization does not have a constitutional obligation to enforce its use in the country’s planning processes, the extent of its institutionalization remains challenging. Hence, continuous PSS use or institutionalization within an actant–network(s) does not automatically translate to PSS institutionalization in the entire planning process.

4.4. Mobilization

Mobilization identifies the SDF-PSS spokesactant(s) across all translation moments. It outlines who the spokesactant represents during translation moments to narrate the SDF-PSS institutionalization in the planning process as of the middle of 2023. Finally, it summarizes how actant–networks across translation moments explain PSS institutionalization. In this research, mobilization characterizes the SDF-PSS translation and institutionalization as “a state of accomplishment in an ongoing process.” It does not imply a definitive conclusion in the SDF-PSS institutionalization.

Mobilization enhanced the SDF-PSS decentralization for local planning processes with five pilot cases of the Urban Dynamic Mapping (UDM) project in five districts. UDM aims to support a participatory spatial and non-spatial database for Rwanda’s planning processes and economic transformation. On that note, we must know (1) who the SDF-PSS spokesactant is now, (2) the group it represents, and (3) whether the group follows the spokesactant. First, the SDF-PSS spokesactant is the department in charge of Urbanization, Human Settlement, and Housing Development at the Ministry of Infrastructure (MININFRA-UHSHD). Second, MININFRA’s role in the Rwandan planning process permits MININFRA-UHSHD to speak only for itself and the sectoral agency involved in housing, urbanization, and infrastructure development—the Rwanda Housing Authority (RHA). MININFRA-UHSHD utilizes the SDF-PSS to integrate spatial realities to implement RHA’s policies and strategies. Third, although RHA is a direct beneficiary of the SDF-PSS decentralization (UDM), it cannot follow the spokesactant for projects involving other national and local levels because MININFRA-UHSHD is not coordinating the Rwandan planning process. Hence, there is a need to enroll the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN), a spokesactant who speaks for all groups (national and local levels), and these groups will follow.

For this to happen, the SDF-PSS institutionalization requires a three-level coordination—technical, political, and economic. The technical level coordination commenced with the SDF-PSS decentralization as the UDM dashboard installation at five pilot districts, supported by the MININFRA-UHSHD and RHA decision rooms. Continuous training of city managers and technical staff across all local levels is part of the technical level coordination. Still, the political and economic levels of coordination for the SDF-PSS institutionalization will require new spokesactant(s).

A continuous PSS use in parts of the national and local levels signifies its institutionalization as a small but stabilized actant–network(s) of the planning process. Still, it does not ascertain PSS institutionalization in the country’s planning process. Changes in stabilized but smaller actant–network(s) of the planning process make PSS institutionalization vulnerable to breakdowns over time.

5. Discussion

As mentioned in the introduction, studies on planning support systems (PSS) identified actants’ heterogeneity (human and non-human) and described post-implementation outcomes in terms of use (limited, continuous). Our study emphasizes that existing studies about PSS post-implementation outcomes cannot help explain or understand PSS institutionalization in practice. Despite two decades of studies adopting various approaches to investigate how compatibility among PSS, users, and planning tasks explains PSS use in planning practice [

2,

6,

8,

9,

10,

12,

20,

21,

50], knowledge on PSS institutionalization remains limited. This study builds on Vonk’s work [

12] that implemented three frameworks (instrument quality approach, diffusion approach, and user acceptance), which first emphasized a lack of understanding about PSS institutionalization in planning practice. It contributes knowledge to the identified gap by presenting another perspective on PSS post-implementation outcomes as its institutionalization in the planning process. It stresses that understanding PSS institutionalization is aided by the knowledge of agencies of associations among actants and actions across different translation moments. The research reported here introduces a new perspective to understand PSS institutionalization using the sociology of translation and actor–network theory, focusing on how the heterogeneous networks of actors and their actions explain PSS institutionalization in planning.

Table 2 compares the analytic framework developed in this article with Vonk’s frameworks to emphasize its contributions—tracing and understanding the complex relationships and actions among different actors can help provide insight into PSS institutionalization. By applying this theoretical lens from social science research to a geographic information methodology (SDF-PSS), the study aims to advance methodological understanding of how PSS becomes institutionalized in planning processes.

The adopted translation approach differs from other PSS adoption studies that mostly focus on how individual or organizational acceptance or use of technology explains adoption. Such studies omit unpacking the multiplicity of interactions and negotiations among diverse actants that shape adoption and help explain how institutionalization happens or not. Tracing and understanding diverse actants’ associations provide insights into required interventions from policymakers and practitioners to facilitate PSS institutionalization.

We utilize Lynne Zucker’s conceptualization of institutionalization to discuss research findings [

19,

29]. The most exciting finding is that PSS institutionalization occurs at varying levels and extents in the planning process. According to Zucker [

19,

29], a higher level of institutionalization happens when observations or discussions are enough to interpret established practices as habitual processes. A lower level of institutionalization results in an unestablished practice that requires mandatory instructions to aid translation and embeddedness in practice. The extent of institutionalization shows the intensity of translation or embeddedness of established practices across levels of institutionalization [

19]. Hence, the extent of PSS institutionalization is influenced by an established level of its institutionalization as a habitual practice (high) or something requiring mandatory instruction(s) to be habitual (low). The following two sub-Sections describe the level and extent of PSS institutionalization with the SDF-PSS findings based on the evidence from research data such as specific actions of decision-maker(s), and policy statements from published policy documents and plans.

5.1. Levels of Institutionalization

The first translation moment (problematization) indicates how the SDF-PSS became indispensable to resolving challenges facing the planning process—(a) increase in rural-urban population influx and (b) lack of a spatial implementation methodology for existing national policies and strategies. The action that initiated translations was the UN-Habitat representative’s improvisation to present the SDF-PSS as a solution to resolve challenges facing the planning process as illustrated in

Figure S2 in the Supplementary Materials. It was followed by the minister’s acceptance of the SDF-PSS as a spatial methodology for implementing the National Urbanization Policy (NUP).

Aside from the minister’s decision during the cabinet meeting to implement the SDF-PSS, a “mandatory instruction” and a budget item were included in the NUP implementation plan. The mandatory instruction (NUP statement 2, p. 47) was to have “

appropriate tools for urban planning and management” implemented with a policy action—“

geodata platform and planning support system (SDF-PSS)”—and the budget [

34]. Hence, the observed SDF-PSS’s continuous use and institutionalization in parts of the planning processes of urbanization projects across the country. The required actants to translate the SDF-PSS institutionalization into a habitual part of all planning processes included as stakeholders of the NUP statement 2 are the local level districts and four ministries at the national level, i.e., (1) Ministry of Infrastructure (MININFRA), (2) Ministry of Environment (MINIRENA), (3) Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN), and (4) Ministry of ICT and Innovation (MINICT). This is ongoing as of 2023 when the fieldwork for this study was conducted.

Despite being envisioned eight years ago, the integration of the SDF-PSS into the country’s spatial planning processes has not been accomplished, revealing a significant shortcoming in the observed SDF-PSS’s institutionalization. This shortcoming largely stems from the absence of a binding directive from MINECOFIN, the authority responsible for coordinating planning processes [

39]. Without such a mandate, sectoral agencies and local districts have neither the incentive nor the obligation to adopt the SDF-PSS in planning processes. However, the following two paragraphs describe what has been done between 2015 to 2023.

The first SDF-PSS spokesactant was the UN-Habitat representative (problematization), who spoke only for the SDF-PSS, not the Rwandan planning process. MININFRA became a spokesactant because the then minister accepted the SDF-PSS as a spatial methodology to implement the NUP. However, the minister only speaks for the SDF-PSS in MININFRA, a small part of the Rwandan planning process. Based on the NUP’s mandatory instructions, MININFRA is the lead ministry for the SDF-PSS implementation and a spokesactant across translation moments. The SDF-PSS is institutionalized as part of MININFRA’s planning process in the Urbanization, Human Settlement, and Housing Development Department (MININFRA-UHSHD). However, as mandated by the NUP, the statutory engagement of other actants at the national and local levels involved in the country’s planning processes is ongoing.

Specifically, the MININFRA-UHSHD is supported by vital individual actants coordinating the SDF-PSS use in the department’s planning process. This support has led to the SDF-PSS decision room installation in MININFRA-UHSHD (interessement) and in one of its agencies, the Rwanda Housing Authority (enrollment), to enhance engaging more actants from the country’s planning process. MININFRA-UHSHD influenced the technical level coordination of the SDF-PSS institutionalization. However, MININFRA-UHSHD’s role in the country’s planning process does not and cannot represent all actants (national and local levels) of the planning process. Therefore, MININFRA-UHSHD’s representation as the SDF-PSS spokesactant explains the ongoing institutionalization happening only in parts of the planning process overseen by MININFRA-UHSHD. Hence, until the SDF-PSS becomes a habitual part of the Rwandan planning process, the SDF-PSS remains at a lower level of institutionalization [

19,

29].

5.2. Extents of Institutionalization

Contrary to expectations, the low level of institutionalization has not limited the SDF-PSS achievements and use in the planning process at MININFRA-UHSHD. For instance, MINECOFIN developed the National Strategy for Transformation (NST1) in 2017, a medium-term strategy to implement Vision 2020/2050. The SDF-PSS was embedded with the NST1 framework to develop the National Strategic Action Plan (NSAP) in 2019. NSAP integrates spatial components with MINECOFIN’s NST1 visions for economic planning, monitoring, and budgeting across the national and local planning processes as shown in

Figure S3 in the Supplementary Materials.

A possible explanation for the continuous use of SDF-PSS, irrespective of the low level of institutionalization, is the mandatory instruction in the NUP that identifies the SDF-PSS as a spatial methodology for implementing policies. In the third translation moment (enrollment), the SDF-PSS consideration for spatial interventions enhanced the involvement of other interested actants according to their roles in the planning process and actions executed through projects that create actant–networks as described in

Table S5 of the Supplementary Materials. The SDF-PSS decentralization project resulted in the Urban Dynamic Map (UDM) pilot projects in five local districts. Though the UDM project integrates a shared policy action from MININFRA and MINICT policy documents, MINICT is not yet active in SDF-PSS institutionalization. As of 2023, MININFRA-UHSHD and one of MININFRA’s agencies—Rwanda Housing Authority (RHA)–coordinate the UDM pilot projects in five local districts. The final translation moment (mobilization) identifies MININFRA-UHSHD as the spokesactant across all translation moments. However, MININFRA-UHSHD does not represent all groups (national and local levels) of the country’s planning process. Hence, the observed level and extent of the SDF-PSS institutionalization as of the middle of 2023 might not change until MINECOFIN becomes a key spokesactant for the SDF-PSS institutionalization [

39].

Increasing the level of institutionalization requires more than technical level coordination. There is a need to enhance the political and economic levels of coordination for the PSS institutionalization. The political level coordination will require obtaining approval (validation) from the Prime Minister’s office to integrate the SDF-PSS and UDM as part of the participatory planning process at the national and local levels. The approval will enhance engaging other mandatory actants of the SDF-PSS institutionalization.

The economic level coordination will require enrolling the statutory ministry in charge of the country’s planning process—the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN). MINECOFIN is a vital spokesactant of the SDF-PSS institutionalization because MINECOFIN coordinates the country’s planning process with a Budget call circular (statutory regulation) that mandates national and local levels to develop Imihigos (annual plans and budgets) for evaluation, approval, and funding. Hence, institutionalizing the PSS in the country’s planning process becomes challenging without MINECOFIN incorporating mandatory instruction to use the SDF-PSS or UDM in the Budget call circular. Moreover, MINECOFIN evaluates and approves Imihigos with the Integrated Financial Management Information and System (IFMIS). Therefore, the technical level coordination still requires that the SDF-PSS/UDM becomes accessible from MINECOFIN’s IFMIS. Without this, PSS institutionalization at national and local levels becomes more challenging.

As of the middle of 2023, collaborations are ongoing to engage other actants to improve the SDF-PSS institutionalization in the planning process. Therefore, the PSS institutionalization in the planning process requires continuous tracing and documentation of lessons learned from various processes (translations, transformations) across actant–network(s). Such knowledge would help support and better strategize for PSS institutionalization in the planning process.

5.3. Implications

Our findings confirm that institutionalization happens at varying levels and extents across different contexts, requiring collaboration between practice and research to develop adaptable approaches. The analytical framework advances information systems translation and institutionalization studies by unpacking the institutionalization of PSS technology in practice. It offers a versatile methodological perspective applicable across different contexts and actants. However, specific implications depend on the research context and cannot be generalized.

The specific implications of interest to the Rwandan practice are connected to the research boundary object (the SDF-PSS) and Rwanda’s planning context. As results (enrollment) have shown, MININFRA-UHSHD presented the SDF-PSS contributions to a technical committee (representatives of ministries and agencies at the national level) in 2020. A separate presentation on the SDF-PSS and NSAP was later made to MINECOFIN to emphasize the contributions to economic planning and budgeting. Another presentation on the SDF-PSS results and contributions was made to a “Sector Working Group” for all urbanization matters with representatives from ministries and agencies. However, a presentation of such nature was not made to the cabinet; as a result, the SDF-PSS was never validated and approved for the Rwandan planning process. Though required collaborations to extend the SDF-PSS institutionalization in the planning process are ongoing.

An earlier study recommended that while the cabinet’s approval is pending, there is a need to involve MINECOFIN, Ministry of Local Governments (MINALOC), and Local Administrative Entities Development Agency (LODA) in the SDF-PSS use to enhance its adoption in the national and local planning processes [

39]. These research findings establish that without involving vital ministries (departments, authorities) responsible for the country’s planning processes in the SDF-PSS use, its institutionalization in practice becomes more challenging. Therefore, there is a need for a policy that recognizes the SDF-PSS as an essential part of the country’s planning processes. The Rwandan cabinet must approve such a policy to enhance the SDF-PSS institutionalization.

Rwanda’s planning context accommodates independent sector policies and district plan implementation. The SDF-PSS is a tool introduced by the implementation of the urbanization sector plan (National Urbanization Policy). Therefore, the SDF-PSS decentralization into an urban dynamic mapping (UDM) tool helps the ministry-in-charge of the urbanization sector achieve two things. First, to engage other national and local level authorities in the sector plan implementation across the country. Second, a means to enhance the SDF-PSS institutionalization in the country’s planning processes. A higher level of institutionalization for the SDF-PSS cannot be achieved without the cabinet’s approval of the SDF-PSS and UDM as a spatial methodology for the Rwandan planning process.

6. Conclusions

Over the past three decades, PSS post-implementation has not been conceptualized as institutionalization within the planning process. Nearly twenty years ago, Vonk [

12] identified this as a critical gap, which this article addresses by investigating continuous PSS implementation in a national planning context to explain how, to what extent, and why institutionalization happens. The investigated PSS has been used in both data-rich (Rwanda) and data-poor (Darfur) settings [

32,

33], so findings may reflect Rwanda’s data-rich context. While some impacts are specific to the Rwandan case or the SDF-PSS, the analytic framework developed here offers methodological guidance applicable for studying PSS institutionalization in diverse contexts. This paper advanced insights into existing studies of the SDF-PSS [

32,

33,

35,

39], by explaining its institutionalization in a country’s planning processes. It draws two conclusions on the findings, discussing theoretical and methodological contributions as the basis for areas of future research. The limitations of the analytical framework were pointed out to probe the potentials of future PSS research.

This research emphasizes two conclusions. First, PSS implementation research from a heterogeneous actant–network associations perspective is essential to understanding PSS institutionalization in the planning process. This research shows that analyzing actants’ actions, roles, and agency through the translation approach offers a deeper insight into PSS institutionalization in planning than technology task user-fit models. Second, research should shift from reductionist accounts that explain post-implementation outcomes solely in terms of PSS usage, fit to planning tasks, user acceptance, or deterministic policy mandates of planning processes. Instead, studies should consider approaches that provide insights into the complexities of heterogeneous actants’ associations, improvisations, negotiations, and shifting alliances, which better explain how PSS institutionalization happens in the planning process.

Theoretically, research findings contribute new knowledge about PSS institutionalization in top-down and bottom-up planning processes. Although this research focused on the institutionalization of PSS in a country, the findings may have a bearing on the institutionalization of other PSS in other settings. For PSS literature, this paper contributes to the (a) understanding of actants’ heterogeneity in PSS institutionalization, (b) contextual influence of the planning process and external organizations, and (c) expands knowledge on how to enhance PSS institutionalization in the planning process.

Methodologically, this paper proposes the sociology of translation (SoT) framework operationalized with the actor–network theory (ANT) methodology to provide additional insights into PSS implementation and institutionalization across four translation moments. It is essential to state that the methodological perspective started with identifying a boundary object for tracing the actants across translation moments. For this article, the PSS (SDF-PSS) is a boundary object of investigation to explain its institutionalization in the planning process. However, the translation approach does not account for the PSS (boundary object) properties or changes (transformations) during translation moments or institutionalization in the planning process. Such investigations must be performed separately. Such PSS studies should start with approaches that not only investigate PSS development [

18], PSS properties or capabilities [

20], and PSS fit to planning tasks or users [

2,

10,

12,

21,

51,

52], but also, and possibly more importantly, include studies to explain sources of transformations (changes in PSS instrument, users, or planning processes) during PSS implementation and institutionalization in practice.

The relevance of this methodological perspective is not to create many ethnographic accounts using the SoT framework or ANT but to present an approach that can contribute knowledge about PSS institutionalization across multiple case studies. It posits that PSS, when considered a boundary object to investigate institutionalization, provides meaningful insights into the institutionalization that other PSS studies have not yet done.

A promising area for future research lies in developing a systematic monitoring approach to investigate and implement the institutionalization of PSS use in spatial planning processes. This is because our findings confirm that those working on the institutionalization of planning technologies, as part of their work tasks, carry a lot of understanding to make quick operational and strategic decisions, but also encounter many obstacles as they move. As such, sustaining the institutionalization of planning technologies needs more than the technical capabilities to support planning processes, financial sustenance, and political validations for planning technologies. Practically, it requires continuous efforts to trace, document, interpret, adapt, and communicate contributions of knowledge from the practical realities of various actors and organizational structures involved in sustaining the institutionalization of planning technologies. Developing such a systematic monitoring framework could capture the dynamics and complexities of how (a) individual motivations and (b) institutional/organizational structures shape PSS institutionalization in practice.

A significant limitation of the analytical framework (SoT and ANT) is that it does not capture broader dynamics of organizational and institutional structures influencing the institutionalization of PSS use in practice. Then, it raised important questions about the nature of PSS research. First, would adopting the developed analytic framework (SoT and ANT) to investigate the institutionalization of existing PSS enhance contributions to science and practice? Second, would the recommendation to explore an institutional approach to PSS research [

39] contribute to understanding PSS institutionalization in the planning process? Third, would research collaborations with practitioners during PSS implementation contribute knowledge to the gap of PSS institutionalization in planning processes? Lastly, would situating such research within broader debates on the implications of governance structures and regulatory tools provide better empirical insights on PSS institutionalization? We recommend that PSS research explores these four questions and examines how they contribute to PSS institutionalization in practice.