The Geographies of Expatriates’ Cultural Venues in Globalizing Shanghai: A Geo-Information Approach Applied to Social Media Data Platform

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background: Expats in a Globalizing Shanghai

2.1. Contextual Geographies 1: Economics, Politics, Outlook of Expats’ Use of Cultural Venues

2.2. Contextual Geographies 2: Expat Communities in Global Cities

3. Analytical Framework

3.1. Data

3.2. Methodology

4. Results

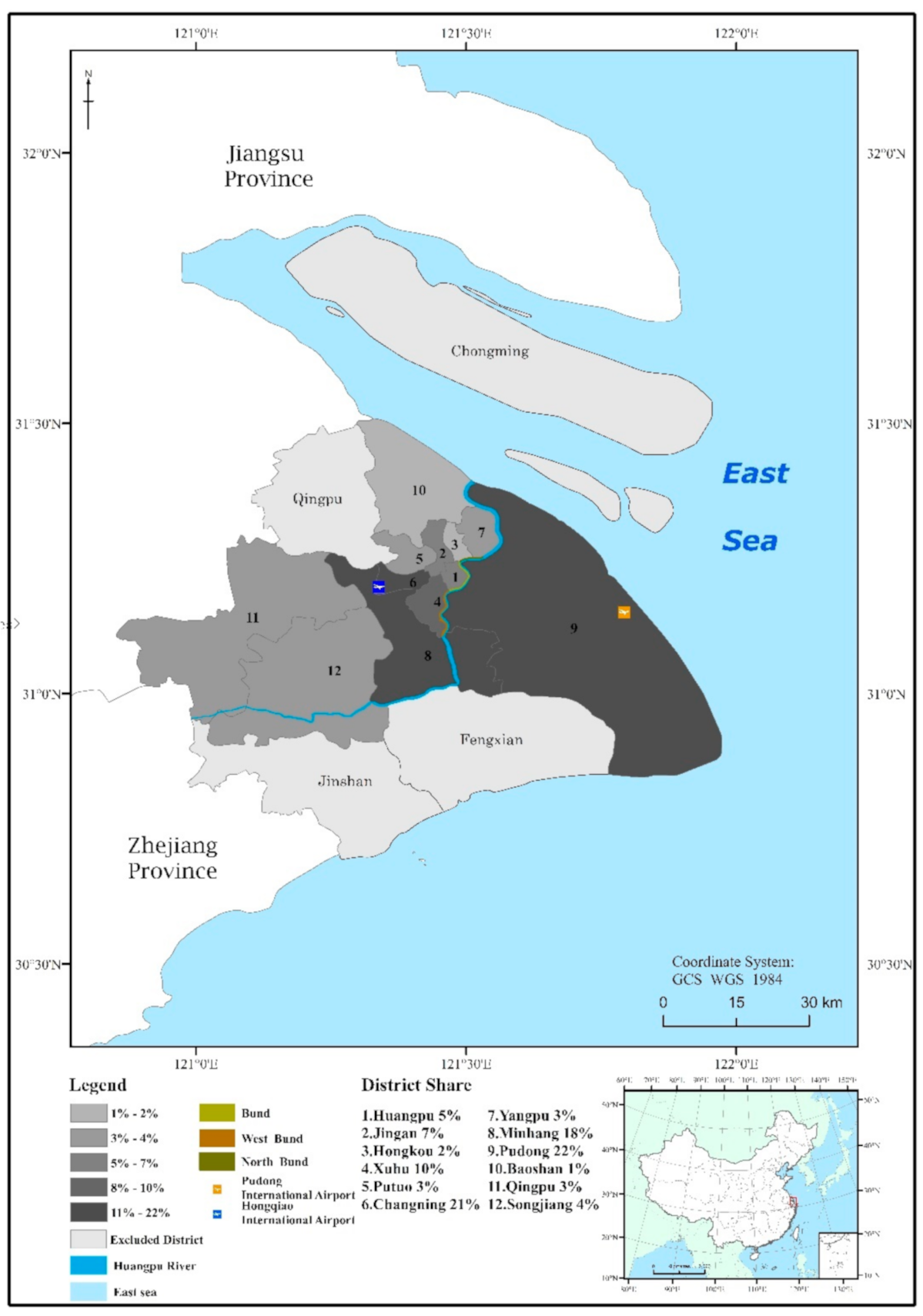

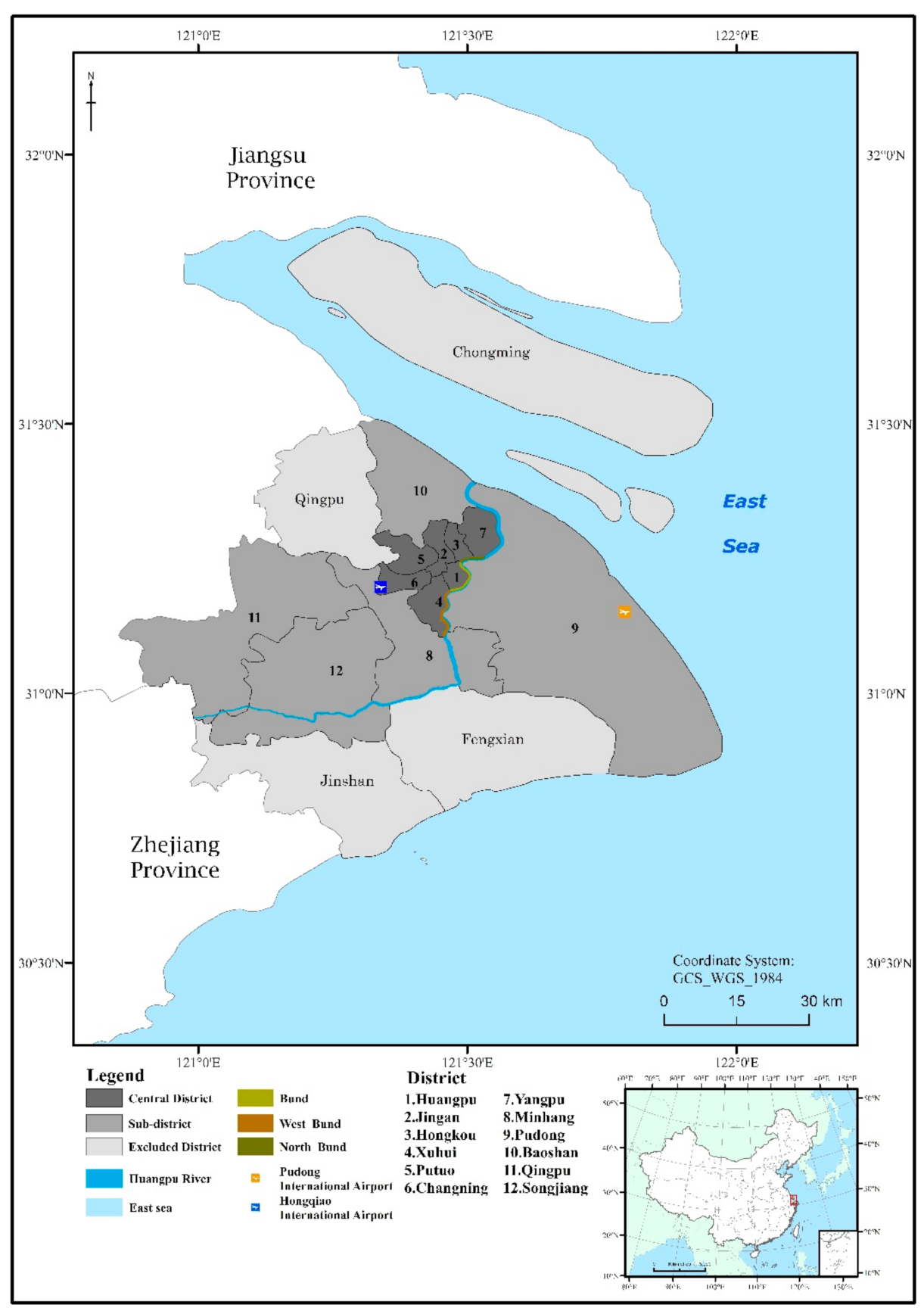

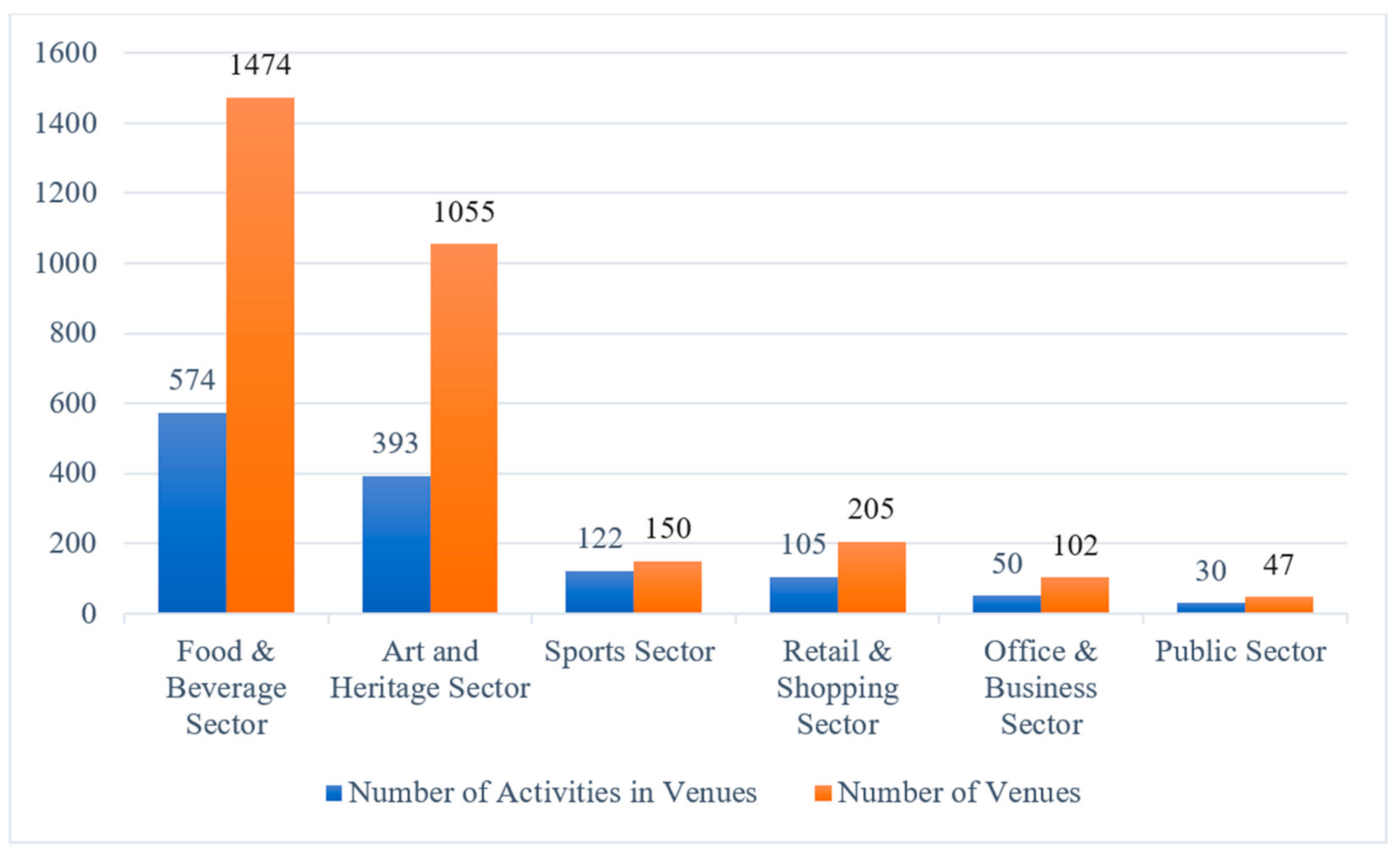

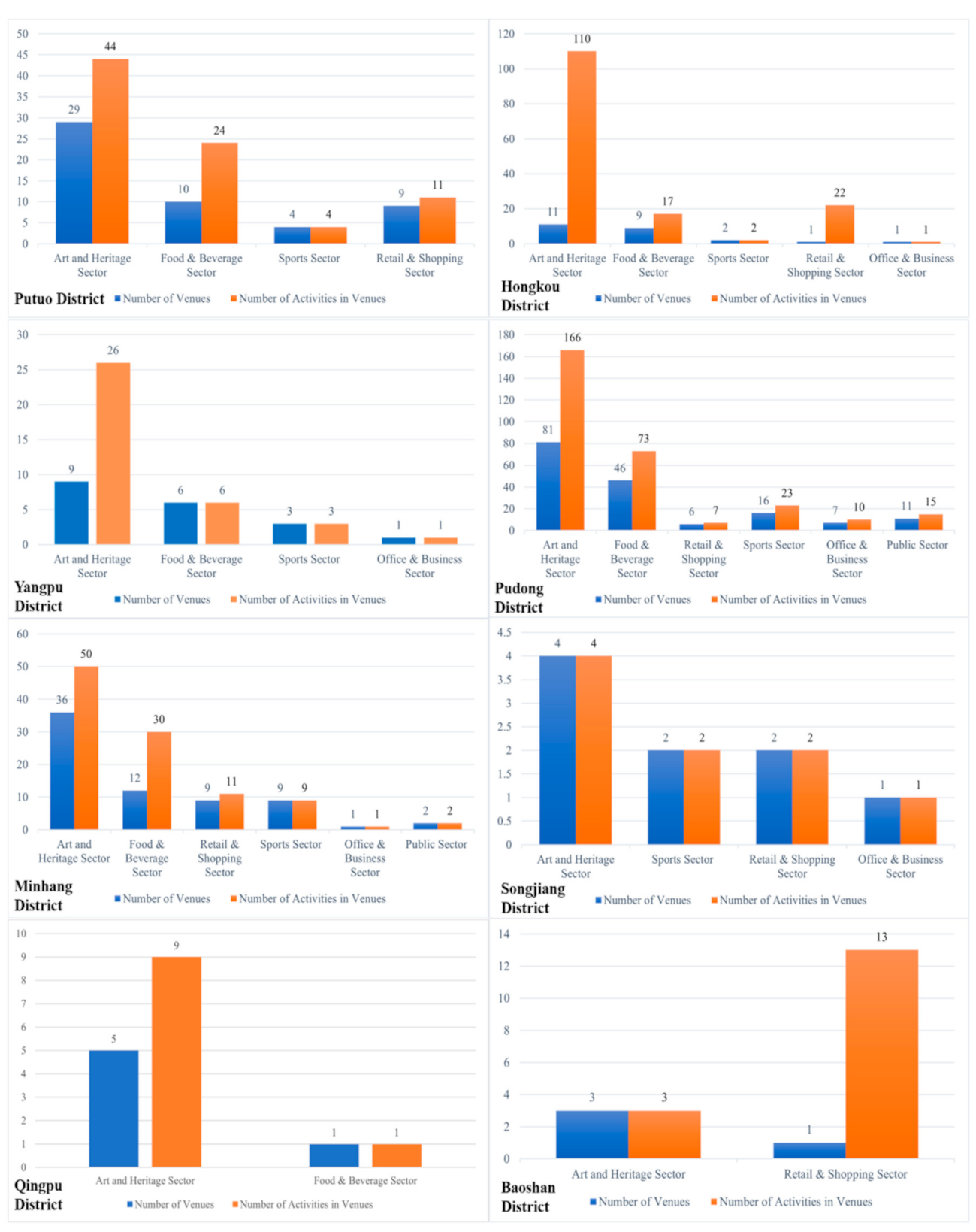

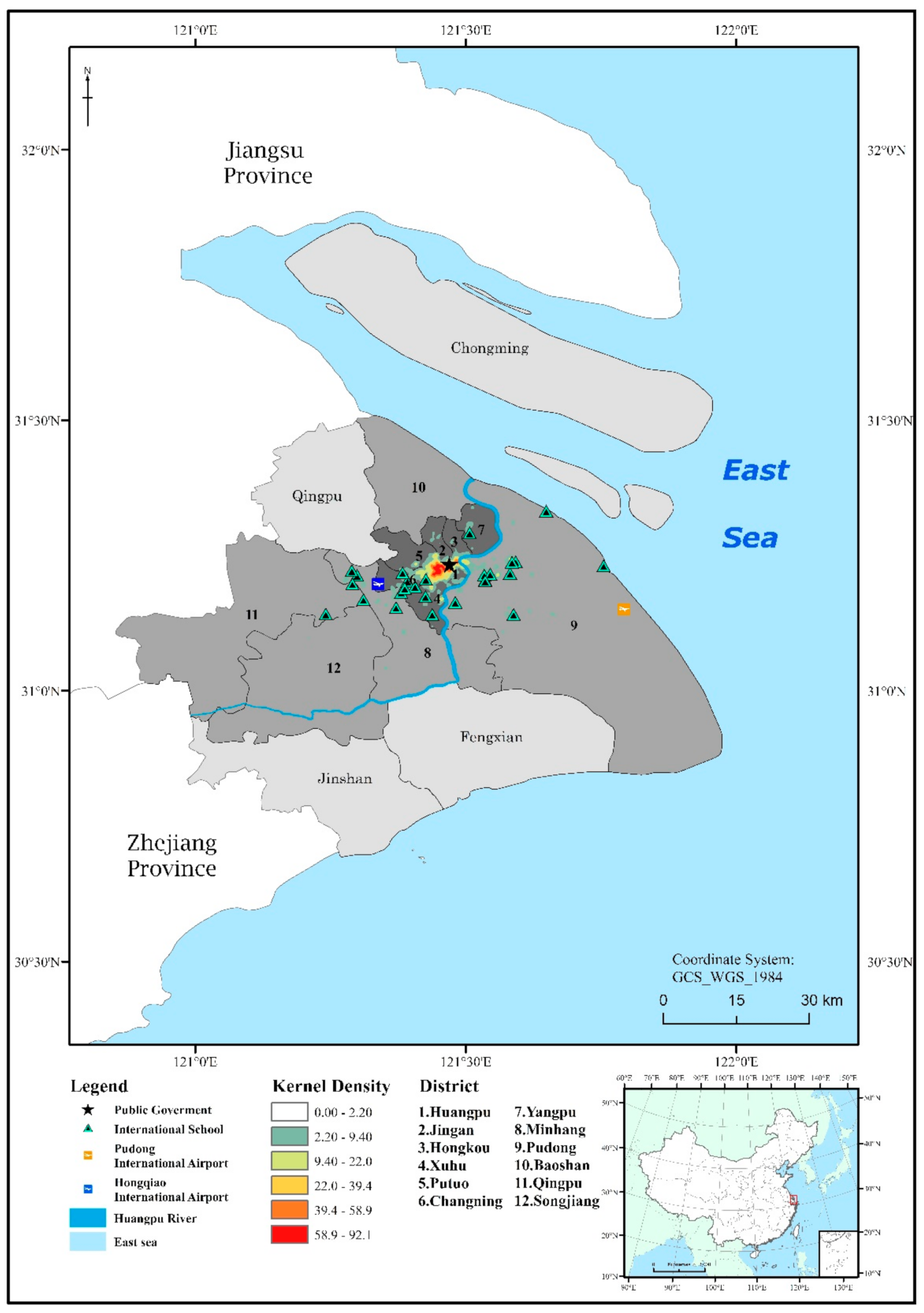

4.1. Geographies of Cultural Venues for Expatriates in Shanghai

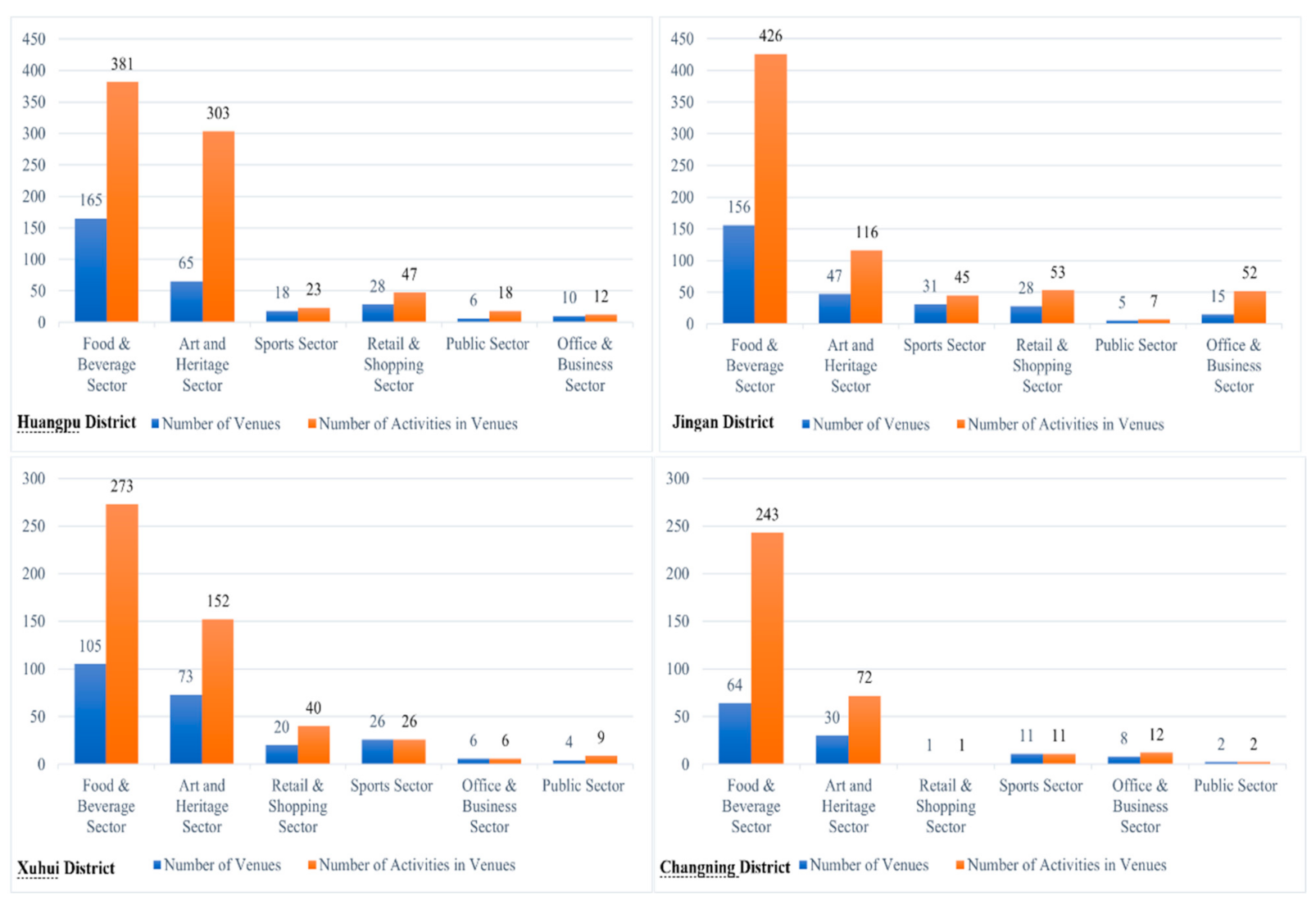

4.2. A Typology of Districts in Shanghai as Cultural Hubs for Expatriates

4.3. Lower Left Quadrant

4.4. Lower Right Quadrant

4.5. Upper Right Quadrant

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaufmann, M.; Siegfried, P.; Huck, L.; Stettler, J. Analysis of tourism hotspot behaviour based on geolocated travel blog data: The Case of Qyer. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ullah, H.; Wan, W.; Haidery, S.A.; Khan, N.U.; Ebrahimpour, Z.; Luo, T. Analyzing the spatiotemporal patterns in green spaces for urban studies using location-based social media data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawrence, H.; Robertson, C.; Feick, R.; Nelson, T. The Spatial-Comprehensiveness (S-COM) index: Identifying optimal spatial extents in volunteered geographic information point datasets. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ling, C.; Wu, J. Exploring the spatial distribution characteristics of emotions of weibo users in wuhan waterfront based on gender differences using social media texts. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Wang, R.; Liu, L.; Wu, H. Exploring urban spatial features of COVID-19 transmission in Wuhan based on social media data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulnerman, A.G.; Karaman, H.; Pekaslan, D.; Bilgi, S. Citizens’ spatial footprint on Twitter—anomaly, trend and bias investigation in Istanbul. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rizwan, M.; Wan, W.; Gwiazdzinski, L. Visualization, spatiotemporal patterns, and directional analysis of urban activities using geolocation data extracted from LBSN. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ebrahimpour, Z.; Wan, W.; García, J.L.V.; Cervantes, O.; Hou, L. Analyzing social-geographic human mobility patterns using large-scale social media data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Xu, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Chen, T.; Jiang, T. A spatiotemporal dilated convolutional generative network for point-of-interest recommendation. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ning, H.; Li, Z.; Hodgson, M.E.; Wang, A.C. Prototyping a social media flooding photo screening system based on deep learning. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farrer, J. ‘New Shanghailanders’ or ‘New Shanghainese’: Western expatriates’ narratives of emplacement in Shanghai. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2010, 36, 1211–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. A massive loss of habitat: New drivers for migration. Sociol. Dev. 2016, 2, 204–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaverstock, J. Highly skilled international labour migration and world cities: Expatriates, executives and entrepreneurs. In International Handbook of Globalization and World Cities; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maslova, S.; Chiodelli, F. Expatriates and the city: The spatialities of the high-skilled migrants’ transnational living in Moscow. Geoforum 2018, 97, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulconbridge, J.R.; Beaverstock, J.V.; Hall, S.; Hewitson, A. The ‘war for talent’: The gatekeeper role of executive search firms in elite labour markets. Geoforum 2009, 40, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, F. The global and local dimensions of place-making: Remaking Shanghai as a world city. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 1359–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Dawood, S.R.S. Global urban development in China: A case study of shanghai in the context of globalization. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 2222–6990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, X. Shanghai Rising: State Power and Local Transformations in a Global Megacity. University of Minnesota Press: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P.; Derudder, B.; Hoyler, M.; Ni, P.; Witlox, F. City-dyad analyses of China’s integration into the world city network. Urban Stud. 2013, 51, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Derudder, B.; Taylor, P.J. Three globalizations shaping the twenty-first century: Understanding the new world geography through its cities. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2020, 110, 1831–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, C. Trade orientation and mutual productivity spillovers between foreign and local firms in China. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2006, 1, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Sit, V.F. Measuring world city formation—The case of Shanghai. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2003, 37, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chiu, L.R. Urban investment and development corporations, new town development and China’s local state restructuring—the case of Songjiang new town, Shanghai. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, L. Alien neighbours: Foreigners in contemporary Shanghai. J. Arch. Urban. 2017, 41, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Statistical Yearbook. 2019. Available online: http://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/zgsh/tjnj2019en.html (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Kawashima, K. Digital outsourcing and Japanese call center workers in Dalian, China. Anthr. News 2017, 58, e358–e362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, A.; Leonard, P. Destination China: Immigration to China in the post-reform era. Pac. Aff. 2020, 93, 424–425. [Google Scholar]

- Farrer, J. Culinary globalization from above and below: Culinary migrants in urban place making in shanghai. In Destination China; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 175–199. [Google Scholar]

- Beaverstock, J.V. Transnational elites in global cities: British expatriates in Singapore’s financial district. Geoforum 2002, 33, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.C. The ‘Expatriatisation’of Holland Village. In Portraits of Places: History, Community and Identity in Singapore; Times Editions Group, Suntec City: Singapore, 1995; pp. 140–157. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.-L.; Gebhardt, H. Space of creative industries: A case study of spatial characteristics of creative clusters in Shanghai. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 22, 2351–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, A. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization; University of Minnesota Press: London, UK, 1996; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.D.; Wu, Y. Urban amenity, human capital and employment distribution in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2019, 91, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wu, F. The suburb as a space of capital accumulation: The development of new towns in Shanghai, China. Antipode 2016, 49, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Gottlieb, J. Urban resurgence and the consumer city. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 1275–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storper, M.; Scott, A. Rethinking human capital, creativity and urban growth. J. Econ. Geogr. 2008, 9, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, J.; Huang, X. Agglomeration, differentiation and creative milieux: A socioeconomic analysis of location behaviour of creative enterprises in Shanghai. Urban Policy Res. 2016, 36, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, C.; Chenavaz, R. The appeal of doing business in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Shanghai. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excel. 2017, 37, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, J. Foreigner street: Urban citizenship in multicultural Shanghai. In Multicultural Challenges and Redefining Identity in East Asia; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Li, C.; Wang, M.; Yang, S. Transnational migrants in Shanghai: Residential spatial patterns and the underlying driving forces. Popul. Space Place 2019, 26, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, C. Socio-spatial restructuring in Shanghai: Sorting out where you live by affordability and social status. Cities 2015, 47, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.; Redmond, G. Review of the circumstances among children in immigrant families in Australia. Child Indic. Res. 2010, 3, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicino, T.; Hanlon, B.; Short, J.R. A typology of urban immigrant neighborhoods. Urban Geogr. 2011, 32, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, S. Residential segregation in Australian cities: A literature review. Int. Migr. Rev. 1993, 27, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-F. Shanghai rush: Skilled migrants in a fantasy city. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2011, 37, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Benton-Short, L. Immigrants and world cities: From the hyper-diverse to the bypassed. GeoJournal 2007, 68, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lau, S.S.Y. Forming foreign enclaves in Shanghai: State action in globalization. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2008, 23, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W. Globalizing Shanghai: International Migration and the Global City (No. 2010/79); WIDER Working Paper: Helsinki, Finland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Farrer, J.; Field, A.D. Shanghai Nightscapes: A Nocturnal Biography of a Global City; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, M. Shanghai Suburbia: Expatriate teenagers’ age-specific experiences of gated community living. City Cult. Soc. 2016, 7, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A. The Cultural Economy of Cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1997, 21, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. Cultural-products industries and urban economic development: Prospects for growth and market contestation in global context. Urban Aff. Rev. 2004, 39, 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. Cities and the Creative Class; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Currid, E.; Williams, S. Two cities, five industries: Similarities and differences within and between cultural industries in New York and Los Angeles. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2010, 29, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flew, T. Toward a cultural economic geography of creative industries and urban development: Introduction to the special issue on creative industries and urban development. Inf. Soc. 2010, 26, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blaschke, T.; Merschdorf, H.; Cabrera-Barona, P.; Gao, S.; Papadakis, E.; Kovacs-Györi, A. Place versus space: From points, lines and polygons in gis to place-based representations reflecting language and culture. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bedianashvili, G. Knowledge economy, entrepreneurial activity and culture factor in modern conditions of globalization: Challenges for Georgia. J. Glob. Bus. 2018, 5, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fouberg, E.H.; Murphy, A.B. Human Geography: People, Place, and Culture; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, K.; Griffiths, R.; Smith, I. Cultural industries, cultural clusters and the city: The example of natural history film-making in Bristol. Geoforum 2002, 33, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, F. China’s changing economic governance: Administrative annexation and the reorganization of local governments in the Yangtze River Delta. Reg. Stud. 2006, 40, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chung, C.K.L.; Bayrak, M.; Wang, W. Administrative boundary changes and regional inequality in provincial China. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2018, 11, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S. The creative spatio-temporal fix: Creative and cultural industries development in Shanghai, China. Geoforum 2019, 106, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Statistical Yearbook; Shanghai Bureau of Statistics Press: Shanghai, China, 2020. Available online: http://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/index.html (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Chang, J.-I.; Kim, K.-J. Everyday life patterns and social segregation of expatriate women in globalizing Asian cities: Cases of Shanghai and Seoul. Neth. J. Hous. Environ. Res. 2016, 31, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Loo, B.P.Y. Hubs of internet entrepreneurs: The emergence of co-working offices in shanghai, china. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Origin | Total Number | Relative Share |

|---|---|---|

| Taiwan | 44,928 | 21.57% |

| Japan | 29,684 | 14.25% |

| USA | 23,602 | 11.33% |

| South Korea | 19,764 | 9.49% |

| Hong Kong | 19,290 | 9.26% |

| France | 7482 | 3.59% |

| Germany | 6893 | 3.31% |

| Canada | 6535 | 3.14% |

| Singapore | 5957 | 2.86% |

| Australia | 5420 | 2.60% |

| UK | 4457 | 2.14% |

| Malaysia | 4021 | 1.93% |

| India | 2550 | 1.22% |

| Italy | 2245 | 1.08% |

| The Philippines | 2024 | 0.97% |

| The Netherlands | 1544 | 0.74% |

| Indonesia | 1345 | 0.65% |

| Spain | 1269 | 0.61% |

| Thailand | 1226 | 0.59% |

| New Zealand | 1215 | 0.58% |

| Russia | 1150 | 0.55% |

| Sweden | 1144 | 0.55% |

| Other | 13,629 | 6.54% |

| District | Area | Total Population | GDP | GDP/Capita | Number of International Residents | International Resident Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central districts | Huangpu | 20.46 | 653,800 | 25.78 | 39.43 | 11,000 | 1.68% |

| Jingan | 36.88 | 1,062,800 | 22.99 | 21.63 | 14,000 | 1.32% | |

| Xuhui | 54.76 | 1,084,400 | 21.11 | 19.47 | 21,000 | 1.94% | |

| Changning | 38.30 | 694,000 | 16.49 | 23.76 | 42,200 | 6.08% | |

| Putuo | 54.83 | 1,281,900 | 11.12 | 8.67 | 6200 | 0.48% | |

| Hongkou | 23.48 | 797,000 | 10.33 | 12.96 | 5000 | 0.63% | |

| Yangpu | 60.73 | 1,312,700 | 20.83 | 15.87 | 5800 | 0.44% | |

| Subdistricts | Pudong | 1210.41 | 5,550,200 | 127.34 | 22.94 | 45,400 | 0.82% |

| Minhang | 370.75 | 2,543,500 | 25.21 | 9.91 | 37,000 | 1.45% | |

| Songjiang | 605.64 | 1,762,200 | 15.80 | 8.96 | 8100 | 0.46% | |

| Qingpu | 670.14 | 1,219,000 | 11.66 | 9.57 | 6200 | 0.51% | |

| Baoshan | 270.99 | 2,042,300 | 15.52 | 7.60 | 1800 | 0.09% |

| Administrative District | Sector Types | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food and Beverage Sector | Art and Heritage Sector | Sports Sector | Retail and Shopping Sector | Office and Business Sector | Public Sector | ||||||||

| V | A | V | A | V | A | V | A | V | A | V | A | ||

| Central districts | Huangpu | 165 | 381 | 65 | 303 | 18 | 23 | 28 | 47 | 10 | 18 | 6 | 12 |

| Jingan | 156 | 426 | 47 | 116 | 31 | 45 | 28 | 53 | 15 | 52 | 5 | 7 | |

| Xuhui | 105 | 273 | 73 | 152 | 26 | 26 | 20 | 40 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 9 | |

| Changning | 64 | 243 | 30 | 72 | 11 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 2 | |

| Putuo | 10 | 24 | 29 | 44 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hongkou | 9 | 17 | 11 | 110 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Yangpu | 6 | 6 | 9 | 26 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Subdistricts | Pudong | 46 | 73 | 81 | 166 | 16 | 23 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 15 |

| Minhang | 12 | 30 | 36 | 50 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Songjiang | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Qingpu | 1 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Baoshan | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total Number | 574 | 1474 | 393 | 1055 | 122 | 150 | 105 | 205 | 50 | 102 | 30 | 47 | |

| District | Spatial Aggregation | Functional Aggregation |

|---|---|---|

| Huangpu | 1.08 | 0.38 |

| Jingan | 1.12 | 0.36 |

| Xuhui | 1.07 | 0.32 |

| Pudong | 0.95 | 0.33 |

| Changning | 1.14 | 0.39 |

| Minhang | 0.96 | 0.34 |

| Putuo | 1.36 | 0.36 |

| Songjiang | 1.13 | 0.31 |

| Hongkou | 1.36 | 0.35 |

| Yangpu | 1.1 | 0.38 |

| Qingpu | 1.43 | 0.72 |

| Baoshan | 1.71 | 0.63 |

| Mean | 1.20 | 0.41 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, X.; Wu, P.; Shen, W.; Huang, Q. The Geographies of Expatriates’ Cultural Venues in Globalizing Shanghai: A Geo-Information Approach Applied to Social Media Data Platform. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10080524

Feng X, Wu P, Shen W, Huang Q. The Geographies of Expatriates’ Cultural Venues in Globalizing Shanghai: A Geo-Information Approach Applied to Social Media Data Platform. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2021; 10(8):524. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10080524

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Xiang, Peipei Wu, Wei Shen, and Qian Huang. 2021. "The Geographies of Expatriates’ Cultural Venues in Globalizing Shanghai: A Geo-Information Approach Applied to Social Media Data Platform" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 10, no. 8: 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10080524