How Culture and Sociopolitical Tensions Might Influence People’s Acceptance of COVID-19 Control Measures That Use Individual-Level Georeferenced Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Areas, Data, and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

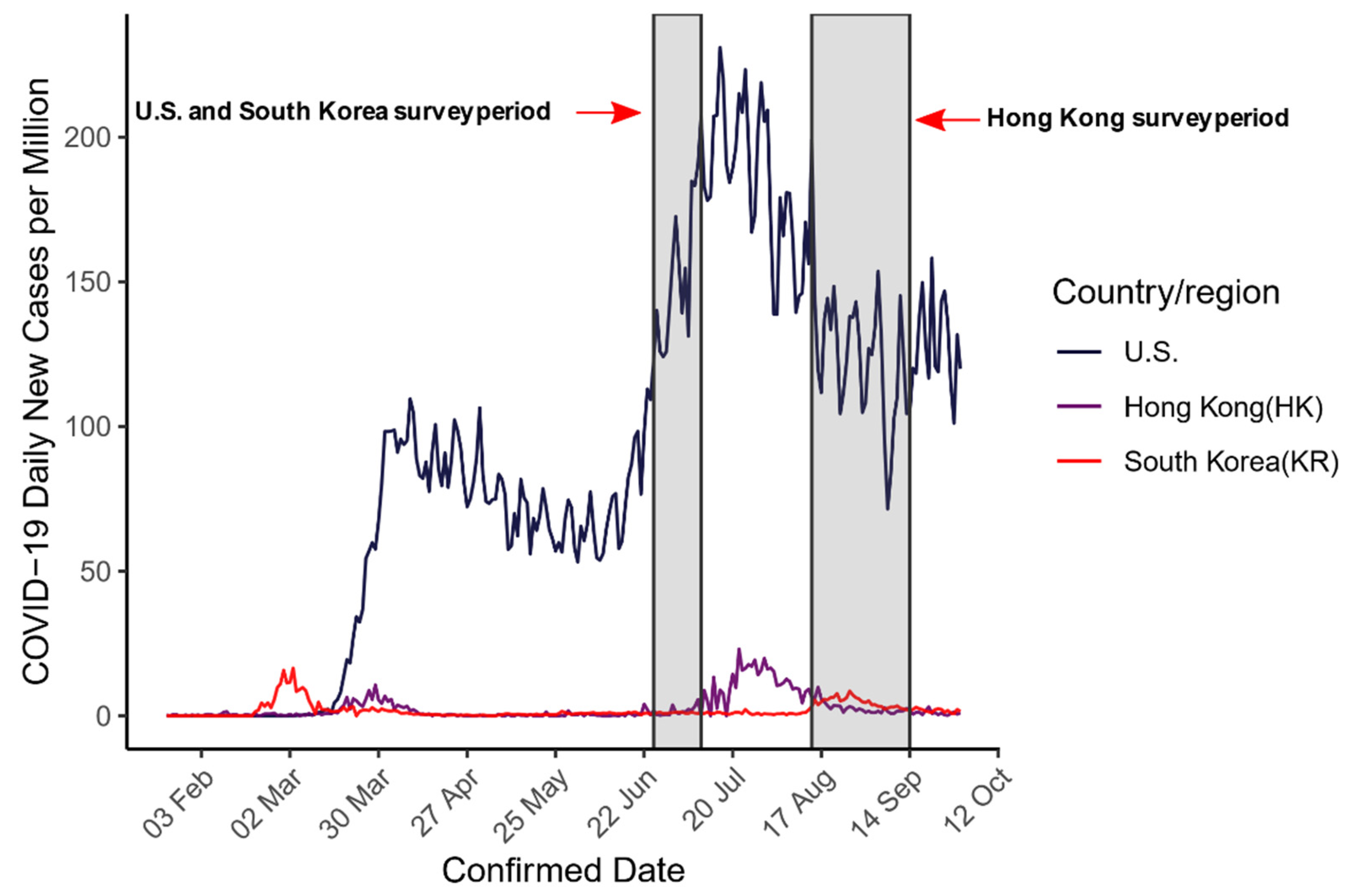

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Survey Questionnaire

3. Results

3.1. Privacy Concerns, Perceived Social Benefits, and Acceptance of COVID-19 Control Measures in Hong Kong

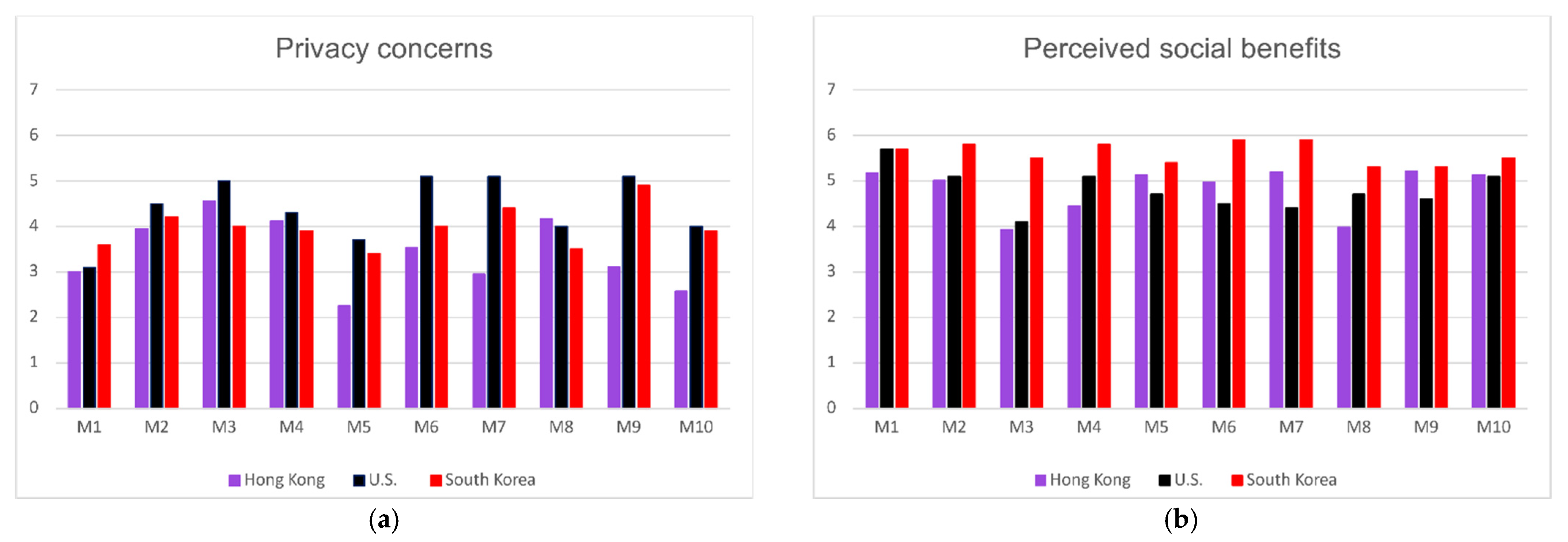

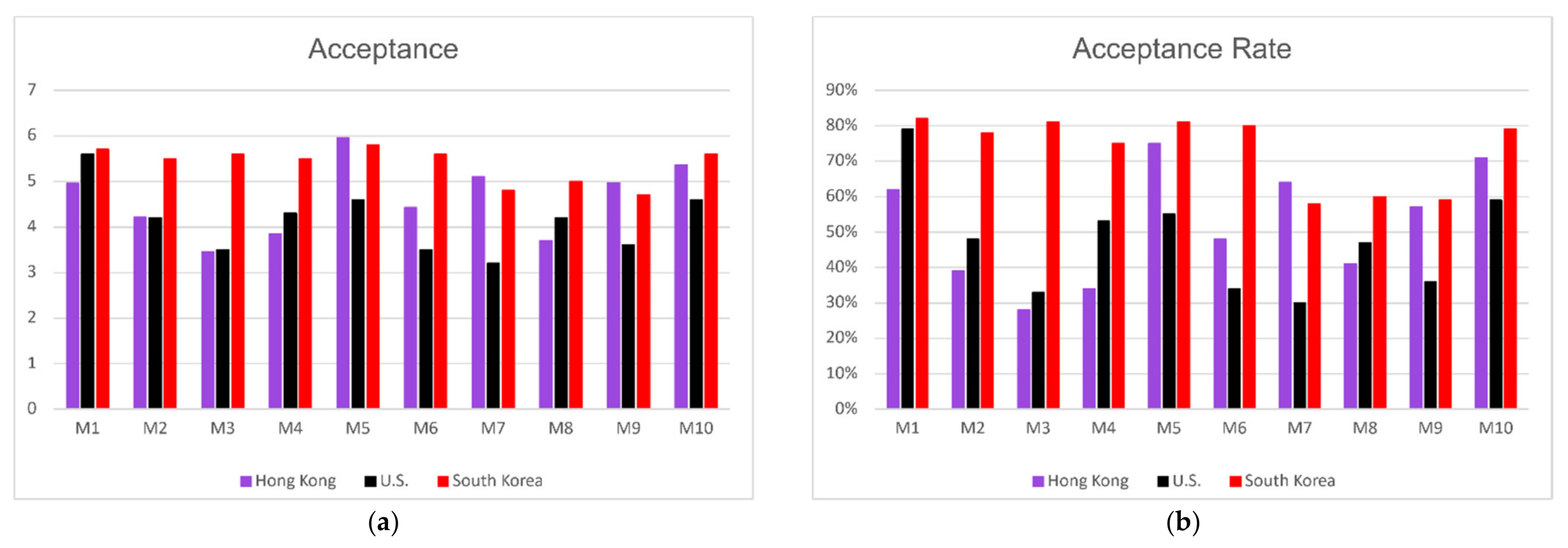

3.2. Comparing Privacy Concerns, Perceived Social Benefits, and Acceptance of COVID-19 Control Measures between the Three Study Areas

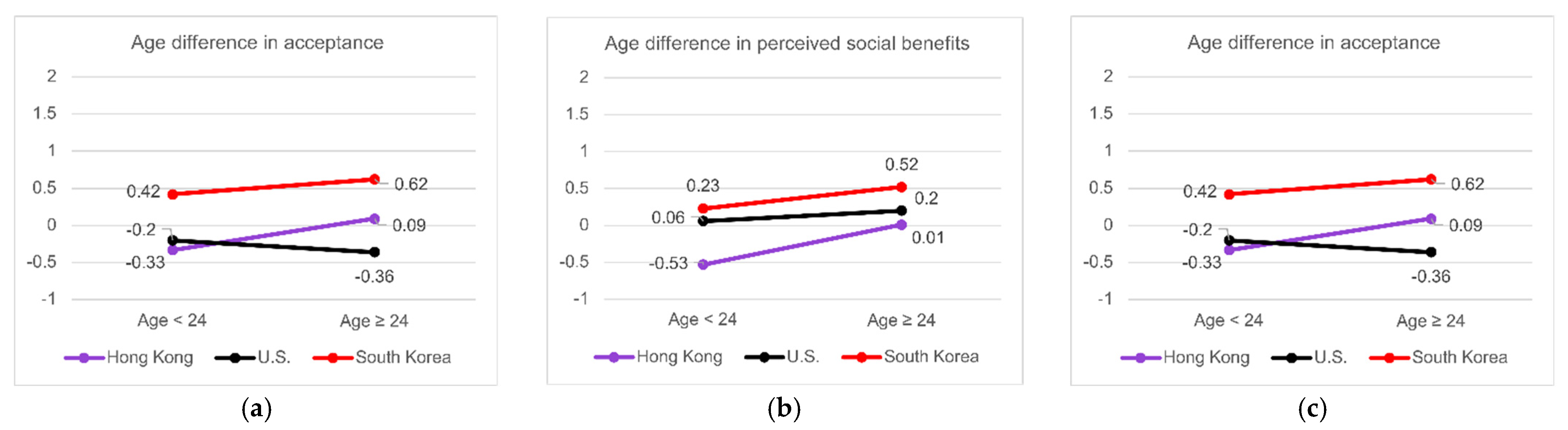

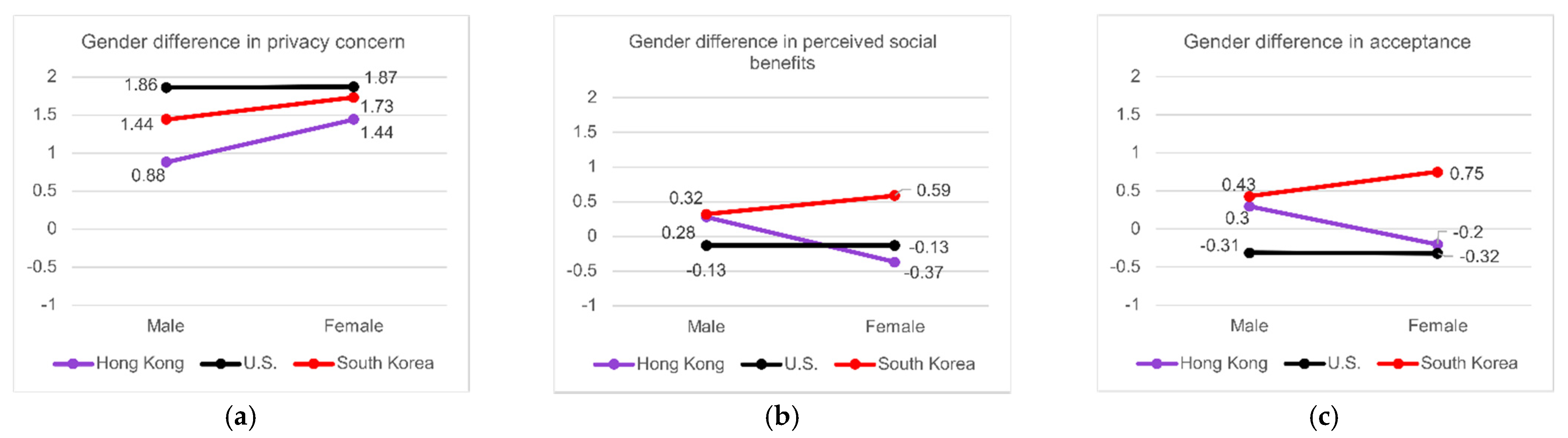

3.3. Associations Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Privacy Concerns, Perceived Social Benefits, and Acceptance of COVID-19 Control Measures

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, R.M.; Heesterbeek, H.; Klinkenberg, D.; Hollingsworth, T.D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 2020, 395, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.G.; Kucharski, A.J.; Eggo, R.M.; Gimma, A.; Edmunds, W.J.; Jombart, T.; O’Reilly, K.; Endo, A.; Hellewell, J.; Nightingale, E.S.; et al. Effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 cases, deaths, and demand for hospital services in the UK: A modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e375–e385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharski, A.J.; Klepac, P.; Conlan, A.J.; Kissler, S.M.; Tang, M.L.; Fry, H.; Gog, J.R.; Edmunds, W.J.; Emery, J.C.; Medley, G.; et al. Effectiveness of isolation, testing, contact tracing, and physical distancing on reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in different settings: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, W.J.; Alley, E.C.; Huggins, J.H.; Lloyd, A.L.; Esvelt, K.M. Bidirectional contact tracing could dramatically improve COVID-19 control. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Z.; Kwan, M.-P.; Wong, M.S.; Huang, J.; Liu, D. Identifying the space-time patterns of COVID-19 risk and their associations with different built environment features in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckee, C.O.; Balsari, S.; Chan, J.; Crosas, M.; Dominici, F.; Gasser, U.; Grad, Y.H.; Grenfell, B.; Halloran, M.E.; Kraemer, M.U.; et al. Aggregated mobility data could help fight COVID-19. Science 2020, 368, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, J.; Miller, B.S.; Manning, E.M.; Lampos, V.; Zhuang, M.; Edelstein, M.; Rees, G.; Emery, V.C.; Stevens, M.M.; Keegan, N.; et al. Digital technologies in the public-health response to COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walrave, M.; Waeterloos, C.; Ponnet, K. Adoption of a contact tracing app for containing COVID-19: A health belief model approach. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e20572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelaw, S.; Mamas, M.A.; Topol, E.; Van Spall, H.G. Applications of digital technology in COVID-19 pandemic planning and response. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e435–e440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbunge, E.; Akinnuwesi, B.; Fashoto, S.G.; Metfula, A.S.; Mashwama, P. A critical review of emerging technologies for tackling COVID-19 pandemic. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekong, I.; Chukwu, E.; Chukwu, M. COVID-19 mobile positioning data contact tracing and patient privacy regulations: Exploratory search of global response strategies and the use of digital tools in Nigeria. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e19139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, N.; Lepri, B.; Sterly, H.; Lambiotte, R.; Deletaille, S.; De Nadai, M.; Letouzé, E.; Salah, A.A.; Benjamins, R.; Cattuto, C.; et al. Mobile phone data for informing public health actions across the COVID-19 pandemic life cycle. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc0764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Mennis, J. Incorporating geographic information science and technology in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, 200246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; McGoogan, J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 2020, 323, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.P.; Ruggles, J.J. Geographic information technologies and personal privacy. Cartographica 2005, 40, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownstein, J.S.; Cassa, C.A.; Kohane, I.S.; Mandl, K.D. An unsupervised classification method for inferring original case locations from low-resolution disease maps. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2006, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brownstein, J.S.; Cassa, C.A.; Mandl, K.D. No place to hide—Reverse identification of patients from published maps. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1741–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, A.; Mills, J.W.; Agustin, L.; Cockburn, M. Confidentiality risks in fine scale aggregations of health data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2011, 35, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, A.J.; Mills, J.W.; Leitner, M. Spatial confidentiality and GIS: Re-engineering mortality locations from published maps about hurricane Katrina. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2006, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Capano, G.; Woo, J.J. Designing policy robustness: Outputs and processes. Policy Soc. 2018, 37, 422–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavel, J.J.V.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Willer, R. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habersaat, K.B.; Betsch, C.; Danchin, M. Ten considerations for effectively managing the COVID-19 transition. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Du, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Tan, X.; Liu, Q. Risk perception of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its related factors among college students in China during quarantine. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, W.B.; Bennett, D. Relationships between initial COVID-19 risk perceptions and protective health behaviors: A national survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 59, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryhurst, S.; Schneider, C.R.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.; van der Linden, S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Jackson, J.C.; Pan, X.; Nau, D.; Pieper, D.; Denison, E.; Dagher, M.; Van Lange, P.A.; Chiu, C.Y.; Wang, M. The relationship between cultural tightness-looseness and COVID-19 cases and deaths: A global analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e135–e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Cheng, K.W.; Qamar, N.; Huang, K.C.; Johnson, J.A. Weathering COVID-19 storm: Successful control measures of five Asian countries. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020, 48, 851–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Wong, M.S.; Kwan, M.P.; Nichol, J.E.; Zhu, R.; Heo, J.; Chan, P.W.; Chin, D.C.W.; Kwok, C.Y.T.; Kan, Z. COVID-19 infection and mortality: Association with PM2.5 concentration and population density—An exploratory study. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, B.Y.; Tang, S.Y. Lessons from COVID-19 responses in East Asia: Institutional infrastructure and enduring policy instruments. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, V. Asia’s COVID-19 lessons for the west: Public goods, privacy, and social tagging. Wash. Q. 2020, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France Weighs Its Love of Liberty in Fight Against Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/17/world/europe/coronavirus-france-digital-tracking.html (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Yan, B.; Zhang, X.; Wu, L.; Zhu, H.; Chen, B. Why do countries respond differently to COVID-19? A comparative study of Sweden, China, France, and Japan. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kwan, M.-P. An examination of people’s privacy concerns, perceptions of social benefits, and acceptance of COVID-19 mitigation measures that harness location information: A comparative study of the USA and South Korea. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2021, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kwan, M.-P.; Levenstein, M.C.; Richardson, D.B. How do people perceive the disclosure risk of maps? Examining the perceived disclosure risk of maps and its implications for geoprivacy protection. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2021, 48, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. Why many countries failed at COVID contact-tracing—But some got it right. Nature 2020, 588, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.; Kim, Y.K.; Hua, J. Governance, technology and citizen behavior in pandemic: Lessons from COVID-19 in East Asia. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 6, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede Insights. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/hong-kong,south-korea,the-usa/ (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Huff, L.; Kelley, L. Levels of organizational trust in individualist versus collectivist societies: A seven-nation study. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kwan, M.-P.; Kan, Z.; Wong, M.S.; Kwok, C.Y.T.; Yu, X. Investigating the relationship between the built environment and relative risk of COVID-19 in Hong Kong. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Threat That COVID-19 Poses Now. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2021/04/fourth-surge-covid-19-unequal/618493/ (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- S. Korea’s COVID-19 Cases Spike as Delta Variant Spreads. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/skorea-reports-over-800-covid-19-cases-highest-daily-count-since-jan-7-yonhap-2021-07-01/ (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Hung, L.S. The SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: What lessons have we learned? J. R. Soc. Med. 2003, 96, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, K.; Jarvis, D.S. Policymaking in a low-trust state: Legitimacy, state capacity, and responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibberts, M.; Johnson, R.B.; Hudson, K. Common survey sampling techniques. In Handbook of Survey Methodology for the Social Sciences; Gideon, L., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H.C.; Gelfand, M.J. Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; Gupta, V. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Sage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- LeaveHomeSafe. Available online: https://www.leavehomesafe.gov.hk/en/ (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- COVID-19: Some Hongkongers Shun Gov’t Tracking App Over Privacy Concerns as New Rules Rolled Out at Eateries. Available online: https://hongkongfp.com/2021/02/19/covid-19-some-hongkongers-shun-govt-tracking-app-over-privacy-concerns-as-new-rules-rolled-out-at-eateries/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Voo, T.C.; Ballantyne, A.; Ng, C.J.; Cowling, B.J.; Xiao, J.; Phang, K.C.; Kaur, S.; Jenarun, G.; Kumar, V.; Lim, J.M.; et al. Public perception of ethical issues related to COVID-19 control measures in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Malaysia: A cross-sectional survey. Preprint 2021. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.01.21252710v1 (accessed on 17 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Survey Findings on HKSAR Government’s Popularity. Available online: http://www.hkiaps.cuhk.edu.hk/eng/survey_result.asp?details=1&ItemID=Survey000004 (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- People’s Trust in the HKSAR Government. Available online: https://www.pori.hk/pop-poll/government-en/k001.html?lang=en (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Weitzman, E.R.; Kelemen, S.; Kaci, L.; Mandl, K.D. Willingness to share personal health record data for care improvement and public health: A survey of experienced personal health record users. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, P.R. Improving access to, use of, and outcomes from public health programs: The importance of building and maintaining trust with patients/clients. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ienca, M.; Vayena, E. On the responsible use of digital data to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 463–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struminskaya, B.; Toepoel, V.; Lugtig, P.; Haan, M.; Luiten, A.; Schouten, B. Understanding willingness to share smartphone-sensor data. Public Opin. Q. 2021, 84, 725–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Privitera, G.J. Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- South Korea Learned Its Successful Covid-19 Strategy from A Previous Coronavirus Outbreak: MERS. Available online: https://thebulletin.org/2020/03/south-korea-learned-its-successful-covid-19-strategy-from-a-previous-coronavirus-outbreak-mers/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Park, S.; Choi, G.J.; Ko, H. Information technology-based tracing strategy in response to COVID-19 in South Korea—Privacy controversies. JAMA 2020, 323, 2129–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Who Needs Yellow Fever Vaccination? Available online: https://www.travelhealth.gov.hk/english/faqs/yell_fever.html (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- What Are the Roadblocks to A “Vaccine Passport”? Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/14/travel/covid-vaccine-passport-excelsior-pass.html (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Lu, J.G.; Jin, P.; English, A.S. Collectivism predicts mask use during COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021793118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.N.; Thyroff, A.; Rapert, M.I.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, H.J. To be or not to be green: Exploring individualism and collectivism as antecedents of environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Gu, J. Exploring the role of cultural individualism and collectivism on public acceptance of nuclear energy. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE. Adv. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Qian, L.; Singhapakdi, A. Sharing sustainability: How values and ethics matter in consumers’ adoption of public bicycle-sharing scheme. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.K.; Chan, M.W.H.; Lee, S.S.; Kwok, K.O. The mediating roles of social benefits and social influence on the relationships between collectivism, power distance, and influenza vaccination among Hong Kong nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 99, 103359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus: Giving Out Patient Details—A Case of Serving Public Good or Invasion of Privacy? Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/coronavirus-giving-out-patient-details-a-case-of-serving-public-good-or-invasion-of (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Coronavirus Doxxing Leads to Online Abuse for Young Woman in China. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3113195/coronavirus-doxxing-leads-online-abuse-young-woman-china (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Santos, H.C.; Varnum, M.E.; Grossmann, I. Global increases in individualism. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Jing, Y.; Feng, Y.U.; Ruolei, G.U.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Huajian, C.A.I. Increasing individualism and decreasing collectivism? Cultural and psychological change around the globe. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 26, 2068–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, M.; Kergall, P. Attitudes and opinions on quarantine and support for a contact-tracing application in France during the COVID-19 outbreak. Public Health 2020, 188, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munzert, S.; Selb, P.; Gohdes, A.; Stoetzer, L.F.; Lowe, W. Tracking and promoting the usage of a COVID-19 contact tracing app. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hong Kong | U.S. | South Korea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (n = 149) | Urban Population 1 | Sample (n = 188) | National Population 2 | Sample (n = 118) | National Population 3 | ||

| Gender | Female | 66% | 55% | 70% | 51% | 42% | 50% |

| Age | 18–24 | 28% | 10% | 26% | 12% | 30% | 14% |

| 25–44 | 52% | 33% | 57% | 34% | 49% | 33% | |

| 45+ | 19% | 57% | 17% | 53% | 19% | 53% | |

| Race | White alone | N/A 4 | N/A 4 | 55% | 74% | N/A 4 | N/A 4 |

| Higher Education | 75% | 33% 5 | 88% | 32% 5 | 73% | 33% 5 | |

| Student | 24% | N/A | 31% | N/A | 41% | N/A | |

| Method | Type | Description | Execution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong | U.S. | South Korea | |||

| M1 | Contact tracing | Obtaining location information by conducting conventional interviews | O | O | O |

| M2 * | Obtaining location information from patients’ mobile phones (e.g., GPS trajectories) | Χ | Δ | O | |

| M3 * | Obtaining location information from patients’ credit card history | Χ | Χ | O | |

| M4 * | Bluetooth-based proximity tracing method | Χ | Δ | Χ | |

| M5 | Self-Quarantine Monitoring | Monitoring people’s self-quarantine by calling them at random times of day | O | Δ | O |

| M6 * | Monitoring people’s self-quarantine by obtaining their real-time locations from their mobile phones (e.g., signal) | Χ | Χ | O | |

| M7 * | Monitoring people’s self-quarantine by requiring them to wear an e-wristband that reported their real-time locations to public health officers | O | Χ | □ | |

| M8 | People were required to carry a valid travel certificate (i.e., not in self-quarantine) when using public places | ◊ | Χ | Χ | |

| M9 | Location Disclosure | Publicly disclosing the locations of major activities of COVID-19 patients with their ages and genders | O | Χ | O |

| M10 | Publicly disclosing the locations of major activities of COVID-19 patients (not disclosing ages and genders) | O | Χ | O | |

| Hong Kong | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Methods | Privacy Concerns | Perceived Social Benefits | Acceptance | Acceptance Rate | Disapproval Rate |

| Contact Tracing | M1 | 3.01(1.88) | 5.18(1.72) | 4.96(1.81) | 0.62 | 0.20 |

| M2 | 3.95(2.11) | 5.01(1.88) | 4.21(2.08) | 0.39 | 0.36 | |

| M3 | 4.56(2.07) | 3.93(2.08) | 3.46(2.08) | 0.28 | 0.54 | |

| M4 | 4.12(2.14) | 4.45(1.97) | 3.85(2.04) | 0.34 | 0.44 | |

| Self-Quarantine Monitoring | M5 | 2.25(1.53) | 5.13(1.87) | 5.59(1.64) | 0.75 | 0.09 |

| M6 | 3.54(2.14) | 4.97(1.86) | 4.43(2.09) | 0.48 | 0.31 | |

| M7 | 2.95(1.82) | 5.19(1.77) | 5.11(1.82) | 0.64 | 0.19 | |

| M8 | 4.17(2.43) | 3.98(2.26) | 3.70(2.46) | 0.41 | 0.50 | |

| Location Disclosure | M9 | 3.11(1.82) | 5.21(1.59) | 4.97(1.66) | 0.57 | 0.14 |

| M10 | 2.58(1.68) | 5.13(1.73) | 5.36(1.68) | 0.71 | 0.14 | |

| Hong Kong–South Korea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Methods | Privacy Concerns | Perceived Social Benefits | Acceptance | |||

| p-value | |r| | p-value | |r| | p-value | |r| | ||

| Contact Tracing | M1 | 0.005 ** | 0.17 | 0.023 | 0.14 | 0.002 ** | 0.19 |

| M2 | 0.438 | 0.05 | 0.001 ** | 0.20 | 0.000 *** | 0.31 | |

| M3 | 0.022 | 0.14 | 0.000 *** | 0.38 | 0.000 *** | 0.49 | |

| M4 | 0.470 | 0.04 | 0.000 *** | 0.33 | 0.000 *** | 0.39 | |

| Self-Quarantine Monitoring | M5 | 0.000 *** | 0.30 | 0.472 | 0.04 | 0.557 | 0.04 |

| M6 | 0.067 | 0.11 | 0.000 *** | 0.22 | 0.000 *** | 0.28 | |

| M7 | 0.000 *** | 0.33 | 0.009 ** | 0.16 | 0.167 | 0.08 | |

| M8 | 0.024 | 0.14 | 0.000 *** | 0.28 | 0.000 *** | 0.26 | |

| Location Disclosure | M9 | 0.000 *** | 0.43 | 0.725 | 0.02 | 0.369 | 0.05 |

| M10 | 0.000 *** | 0.34 | 0.130 | 0.09 | 0.530 | 0.04 | |

| Hong Kong–U.S. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types | Methods | Privacy Concerns | Perceived Social Benefits | Acceptance | |||

| p-value | |r| | p-value | |r| | p-value | |r| | ||

| Contact Tracing | M1 | 0.826 | 0.01 | 0.000 *** | 0.19 | 0.001 ** | 0.17 |

| M2 | 0.035 | 0.11 | 0.506 | 0.04 | 0.936 | 0.00 | |

| M3 | 0.065 | 0.10 | 0.327 | 0.05 | 0.831 | 0.01 | |

| M4 | 0.388 | 0.05 | 0.000 *** | 0.19 | 0.048 | 0.11 | |

| Self-Quarantine Monitoring | M5 | 0.000 *** | 0.33 | 0.058 | 0.10 | 0.000 *** | 0.24 |

| M6 | 0.000 *** | 0.35 | 0.045 | 0.11 | 0.000 *** | 0.21 | |

| M7 | 0.000 *** | 0.47 | 0.001 ** | 0.18 | 0.000 *** | 0.45 | |

| M8 | 0.560 | 0.03 | 0.005 ** | 0.15 | 0.110 | 0.09 | |

| Location Disclosure | M9 | 0.000 *** | 0.48 | 0.009 ** | 0.14 | 0.000 *** | 0.32 |

| M10 | 0.000 *** | 0.35 | 0.919 | 0.01 | 0.000 *** | 0.19 | |

| Variables | Model 1 (Acceptance) | Model 2 (Privacy Concerns) | Model 3 (Perceived Social Benefits) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | −0.084(0.095) | 0.263(0.098) ** | −0.161(0.099) | |

| Age | Age 1 (18–24) | −0.153(0.119) | 0.133(0.123) | −0.067(0.123) |

| Age 2 (45+) | 0.083(0.123) | −0.080(0.128) | 0.037(0.128) | |

| Employment Status | Student | 0.107(0.125) | −0.117(0.130) | 0.031(0130) |

| Employed | 0.077(0.105) | −0.009(0.109) | 0.094(0.109) | |

| Higher education | 0.035(0.177) | −0.006(0.122) | 0.281(0.122) * | |

| Country/ Region 1 | USA | −0.430(0.108) *** | 0.724(0.125) *** | −0.109(0.112) *** |

| South Korea | 0.586(0.120) *** | 0.398(0.124) ** | 0.573(0.124) *** | |

| Collectivist orientation score | 0.223(0.048) *** | −0.186(0.049) *** | 0.180(0.049) *** | |

| Intercept | −0.002(0.176) | −0.530(0.182) ** | −0.278(0.182) | |

| R2 | 0.175 | 0.120 | 0.118 | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.157 | 0.101 | 0.099 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, J.; Kwan, M.-P.; Kim, J. How Culture and Sociopolitical Tensions Might Influence People’s Acceptance of COVID-19 Control Measures That Use Individual-Level Georeferenced Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10070490

Huang J, Kwan M-P, Kim J. How Culture and Sociopolitical Tensions Might Influence People’s Acceptance of COVID-19 Control Measures That Use Individual-Level Georeferenced Data. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2021; 10(7):490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10070490

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Jianwei, Mei-Po Kwan, and Junghwan Kim. 2021. "How Culture and Sociopolitical Tensions Might Influence People’s Acceptance of COVID-19 Control Measures That Use Individual-Level Georeferenced Data" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 10, no. 7: 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10070490

APA StyleHuang, J., Kwan, M.-P., & Kim, J. (2021). How Culture and Sociopolitical Tensions Might Influence People’s Acceptance of COVID-19 Control Measures That Use Individual-Level Georeferenced Data. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10(7), 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10070490