Dedicated Nonlinear Control of Robot Manipulators in the Presence of External Vibration and Uncertain Payload

Abstract

1. Introduction

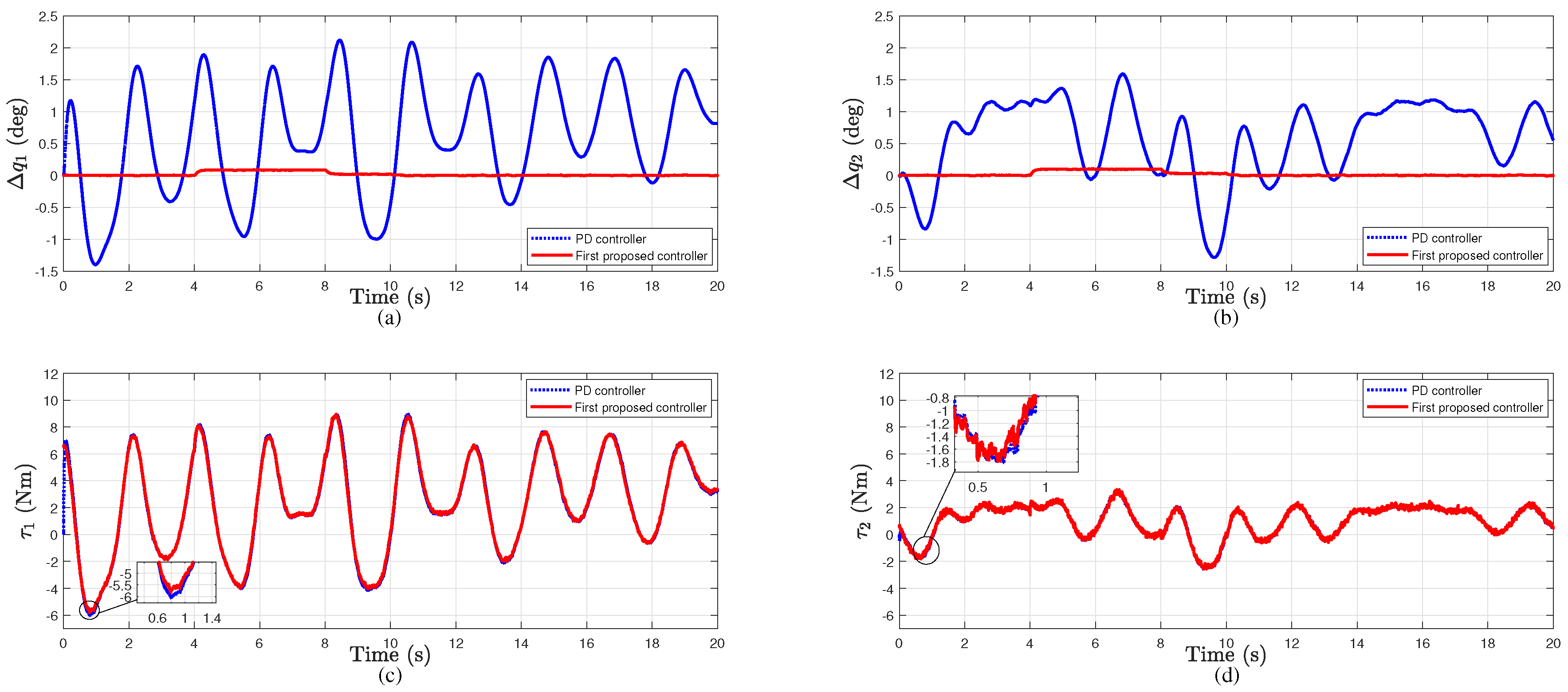

- The controller derived from the first approach is compared with a PD controller in the presence of bounded disturbance torques that are caused by vibration and payload variation. The simulation results show a UUB tracking error for this controller with a good control effort, while the PD controller performs poorly in term of accuracy.

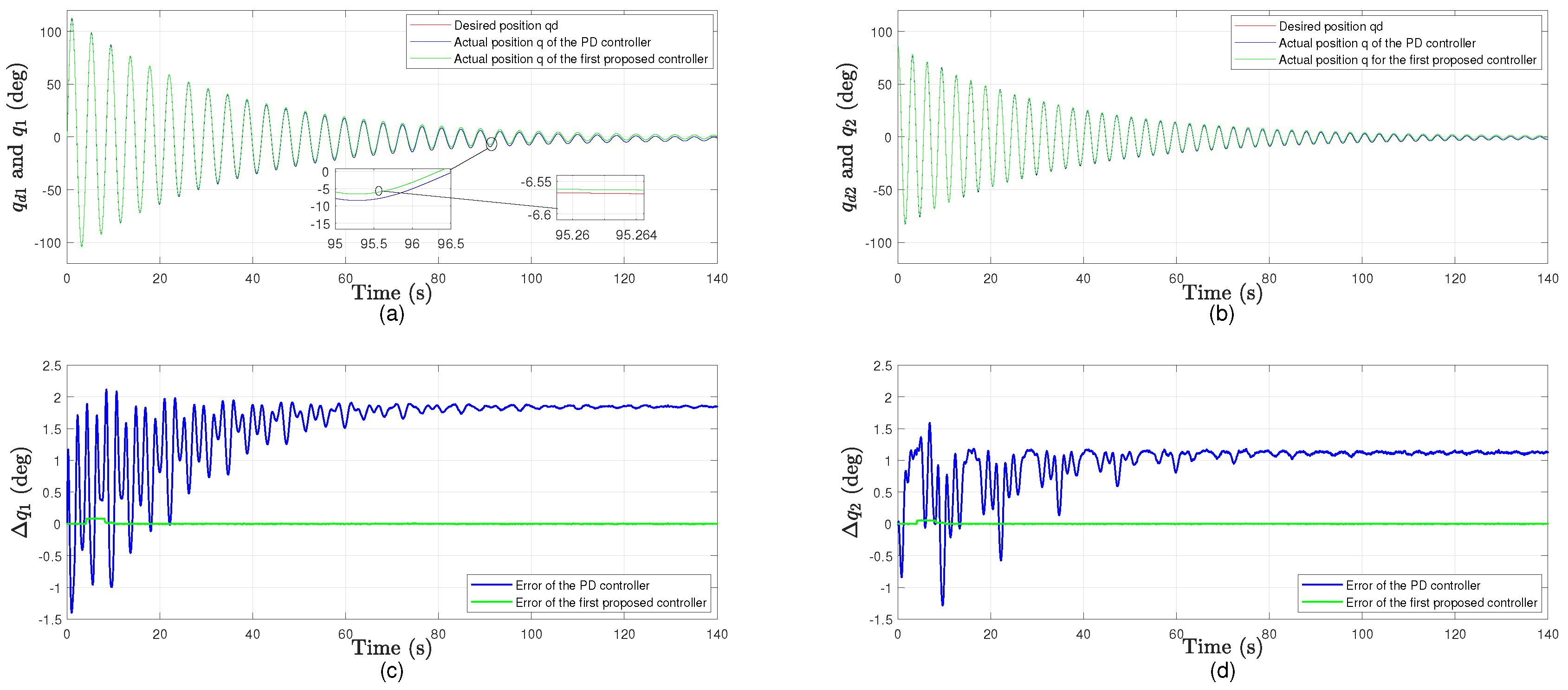

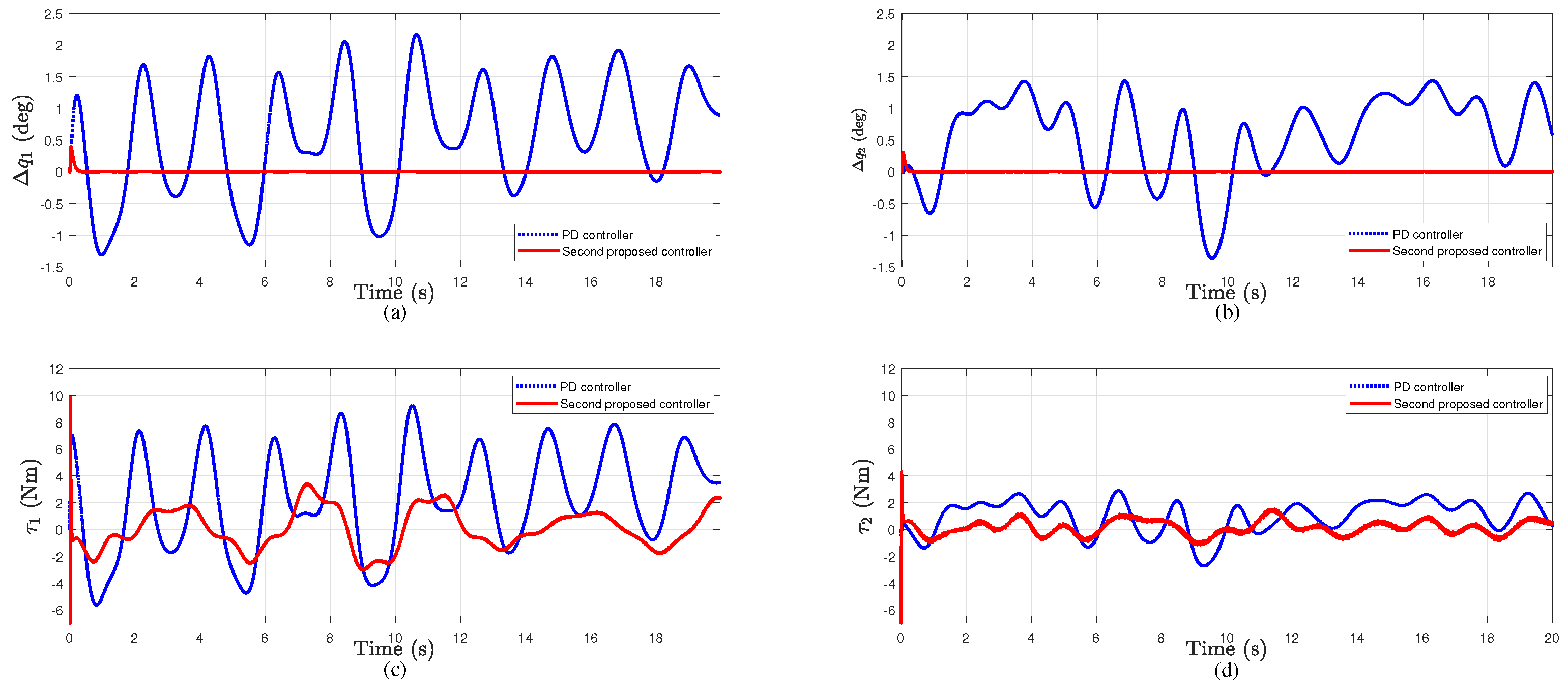

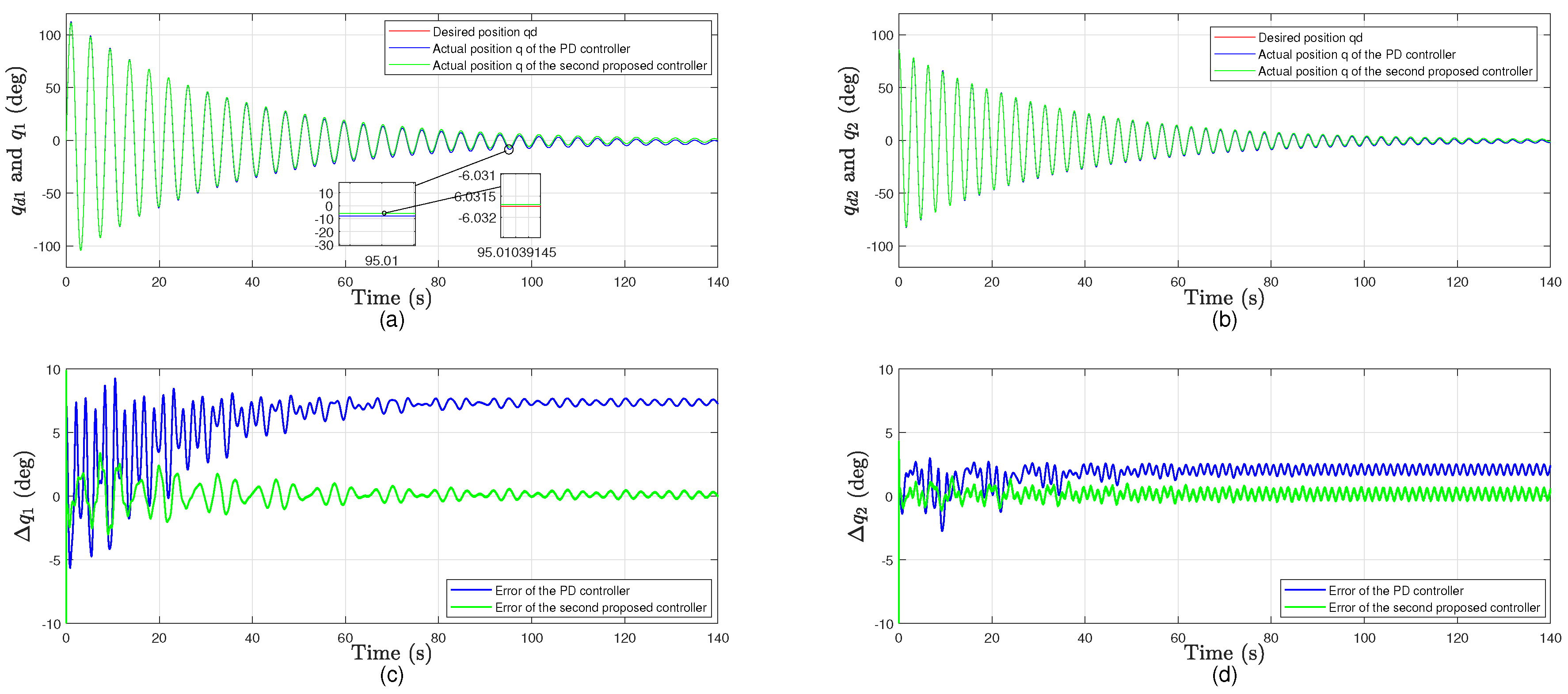

- The controller derived from the second approach is also compared with the PD controller in the presence of a differentiable and bounded vibration and payload variation torques and with a specific initial condition. The simulation results show an asymptotic tracking error for this controller with low control effort. The PD controller behaves almost the same as previously.

2. Specified Dynamic Model and Preliminaries

3. Problem Formulation and Control Approaches

3.1. Problem Formulation

3.2. Control Approach Based on the Bounded-Disturbance: First Control Approach

3.3. Control Approach Based on the Bounded-Differentiable-Disturbance: Second Control Approach

4. Simulation Results

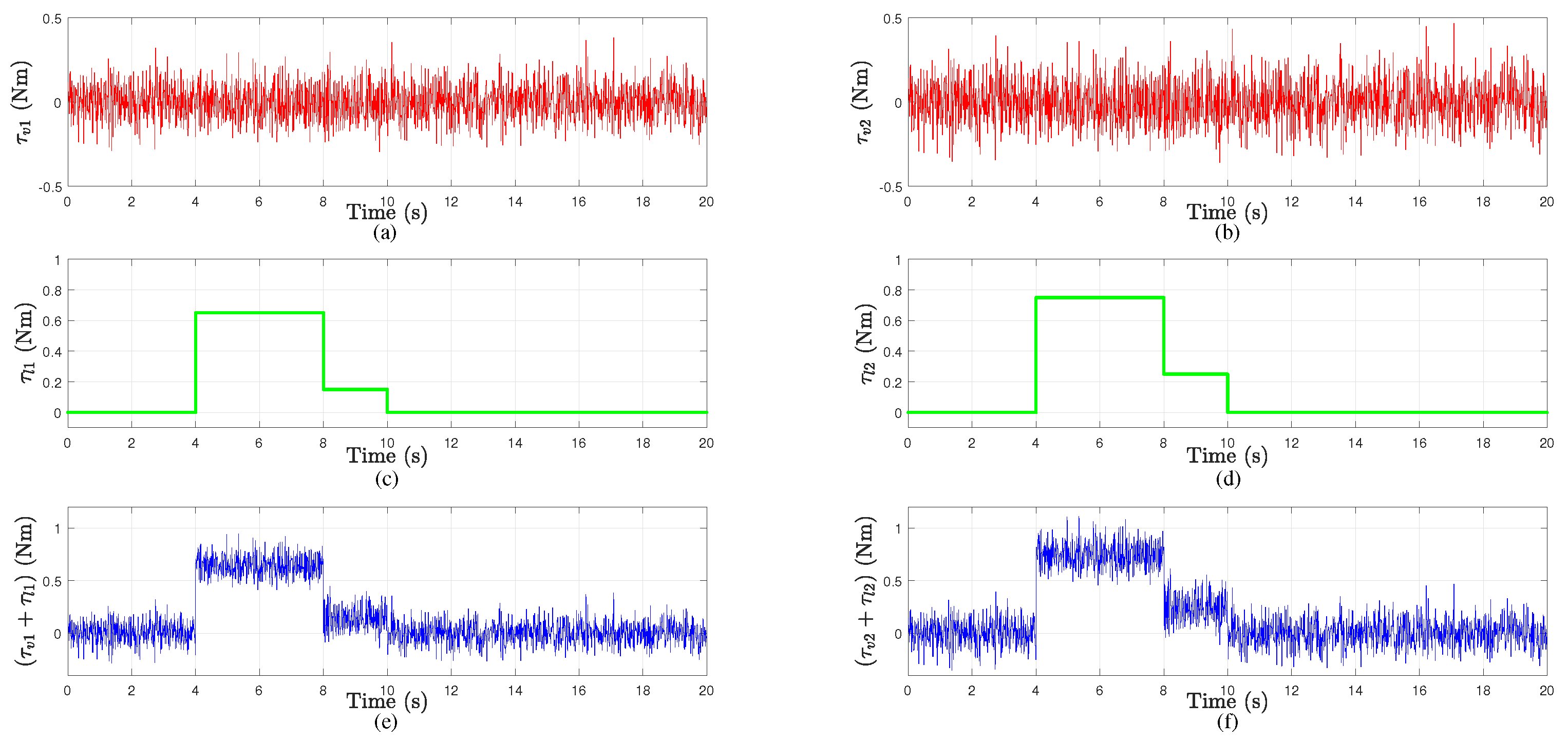

4.1. Simulation Results for the Control Approach Based on the Bounded Disturbance

4.2. Simulation Results for the Second Control Approach Based on the Bounded-Differentiable-Disturbance

4.3. Quantitative Analysis

- Maximum absolute value of the error for each joint.

- Root mean square (rms) values of the error and input torque for each joint.

- Percentage change in the rms values of the error and input torque for the proposed control approaches compared with the PD control.

- The first approach reduces the average tracking errors of both joints by about 97% with almost the same control efforts.

- The second approach reduces the average tracking errors and control efforts of both joints by about 98% and 81%, respectively.

- The proposed controllers have higher computation time than that in the standard PD controller.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, G.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X. Markerless human–manipulator interface using leap motion with interval Kalman filter and improved particle filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2016, 12, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotine, J.J.E.; Li, W. On the adaptive control of robot manipulators. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1987, 6, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.J.; Hsu, P.; Sastry, S.S. Adaptive control of mechanical manipulators. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1987, 6, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, T.S.; Lasky, T.; Guo, Z. Robust independent joint controller design for industrial robot manipulators. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1991, 38, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, D.; Qu, Z.; Lewis, F.; Dorsey, J. Robust control for the tracking of robot motion. Int. J. Control 1990, 52, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spong, M.W. On the robust control of robot manipulators. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1992, 37, 1782–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotine, J.J.E. The robust control of robot manipulators. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1985, 4, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, K.S.; Chen, Y.P. A new controller design for manipulators using the theory of variable structure systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1988, 33, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafia, N.; El Kari, A.; Ayad, H.; Mjahed, M. Robust interval type-2 fuzzy sliding mode control design for robot manipulators. Robotics 2018, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, M.; Johnson, M.A.; Rogers, S.K. Neural network payload estimation for adaptive robot control. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1991, 2, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, C.; Lewis, F.L.; Dawson, D.M. Robust neural-network control of rigid-link electrically driven robots. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1998, 9, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; He, W.; Zhou, C.; Sun, C. Neural network control of a two-link flexible robotic manipulator using assumed mode method. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 15, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Dawson, D.M.; de Queiroz, M.S.; Dixon, W.E. Global adaptive output feedback tracking control of robot manipulators. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2000, 45, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, W.E.; Zergeroglu, E.; Dawson, D.M. Global robust output feedback tracking control of robot manipulators. Robotica 2004, 22, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; de Queiroz, M.S.; Dawson, D.M. Robust adaptive asymptotic tracking of nonlinear systems with additive disturbance. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2006, 51, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patre, P.M.; MacKunis, W.; Makkar, C.; Dixon, W.E. Asymptotic tracking for systems with structured and unstructured uncertainties. In Proceedings of the 45th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–15 December 2006; pp. 441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Makkar, C.; Hu, G.; Sawyer, W.G.; Dixon, W.E. Lyapunov-based tracking control in the presence of uncertain nonlinear parameterizable friction. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2007, 52, 1988–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patre, P.M.; MacKunis, W.; Kaiser, K.; Dixon, W.E. Asymptotic tracking for uncertain dynamic systems via a multilayer neural network feedforward and RISE feedback control structure. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 2180–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Meng, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. RISE and disturbance compensation based trajectory tracking control for a quadrotor UAV without velocity measurements. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 74, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Xie, M.; Li, C. RISE based active vibration control for the flexible refueling hose. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 92, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroza, N.; MacKunis, W.; Golubev, V. Robust nonlinear regulation of limit cycle oscillations in uavs using synthetic jet actuators. Robotics 2014, 3, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N.; Hughes, D.; Walters, P.; Schwartz, E.M.; Dixon, W.E. Nonlinear RISE-based control of an autonomous underwater vehicle. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2014, 30, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, D.; Lee, C.; Mavroidis, C.; Antoniadis, I. Robust vibration suppression in flexible payloads carried by robot manipulators using digital filtering of joint trajectories. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Robotics and Automation, Monterrey, Mexico, 10–12 November 2000; pp. 244–249. [Google Scholar]

- Mamani, G.; Becedas, J.; Feliu, V. Sliding mode tracking control of a very lightweight single-link flexible robot robust to payload changes and motor friction. J. Vib. Control 2012, 18, 1141–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliu, V.; Castillo, F.; Jaramillo, V.; Partida, G. A Robust Controller for A 3-DOF Flexible Robot with a Time Variant Payload. Asian J. Control 2013, 15, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.W.; Petkov, P.; Konstantinov, M.M. Robust Control Design with MATLAB®; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- From, P.J.; Schjølberg, I.; Gravdahl, J.T.; Pettersen, K.Y.; Fossen, T.I. On the boundedness and skew-symmetric properties of the inertia and Coriolis matrices for vehicle-manipulator systems. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2010, 43, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, W.E.; Behal, A.; Dawson, D.M.; Nagarkatti, S.P. Nonlinear Control of Engineering Systems: A Lyapunov-Based Approach; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crane III, C.D.; Duffy, J. Kinematic Analysis of Robot Manipulators; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Slotine, J.J.E.; Li, W. Applied Nonlinear Control; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, H. Nonlinear Systems; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Desoer, C.A.; Vidyasagar, M. Feedback Systems: Input-Output Properties; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, F.L.; Dawson, D.M.; Abdallah, C.T. Robot Manipulator Control: Theory and Practice; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, J. Adaptive Control of Mechanical Manipulators; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kokotovic, P.V. The joy of feedback: Nonlinear and adaptive. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 1992, 12, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Xian, B.; De Queiroz, M.S.; Dawson, D.M. A Continuous Asymptotic Tracking Control Strategy for Uncertain Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2004, 49, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass of link 1 | kg | ||

| Mass of link 2 | kg | ||

| Length of link 1 | m | ||

| Length of link 2 | m |

| Indexes | PD Control | First Approach |

|---|---|---|

| (deg) | ||

| (deg) | ||

| (deg) | ||

| (deg) | ||

| (Nm) | ||

| (Nm) |

| Indexes | PD Control | Second Approach |

|---|---|---|

| (deg) | ||

| (deg) | ||

| (deg) | ||

| (deg) | ||

| (Nm) | ||

| (Nm) |

| Indexes | First Approach | Second Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Controller | No. of Calls | Time/Call (ms) | Total Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD controller | 20552 | ||

| First controller | 76695 | ||

| Second controller | 934670 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mustafa, M.M.; Hamarash, I.; Crane, C.D. Dedicated Nonlinear Control of Robot Manipulators in the Presence of External Vibration and Uncertain Payload. Robotics 2020, 9, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics9010002

Mustafa MM, Hamarash I, Crane CD. Dedicated Nonlinear Control of Robot Manipulators in the Presence of External Vibration and Uncertain Payload. Robotics. 2020; 9(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics9010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustafa, Mustafa M., Ibrahim Hamarash, and Carl D. Crane. 2020. "Dedicated Nonlinear Control of Robot Manipulators in the Presence of External Vibration and Uncertain Payload" Robotics 9, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics9010002

APA StyleMustafa, M. M., Hamarash, I., & Crane, C. D. (2020). Dedicated Nonlinear Control of Robot Manipulators in the Presence of External Vibration and Uncertain Payload. Robotics, 9(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics9010002