Dodecanedioic Acid: Alternative Carbon Substrate or Toxic Metabolite?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells

2.2. Cell Viability Assay

2.3. Glucose Uptake Assay

2.4. 13C12-DODA Uptake and Incorporation into Krebs Cycle Intermediates

2.5. Seahorse Analysis

2.6. Metabolomics Analysis and Lipid Profiling

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

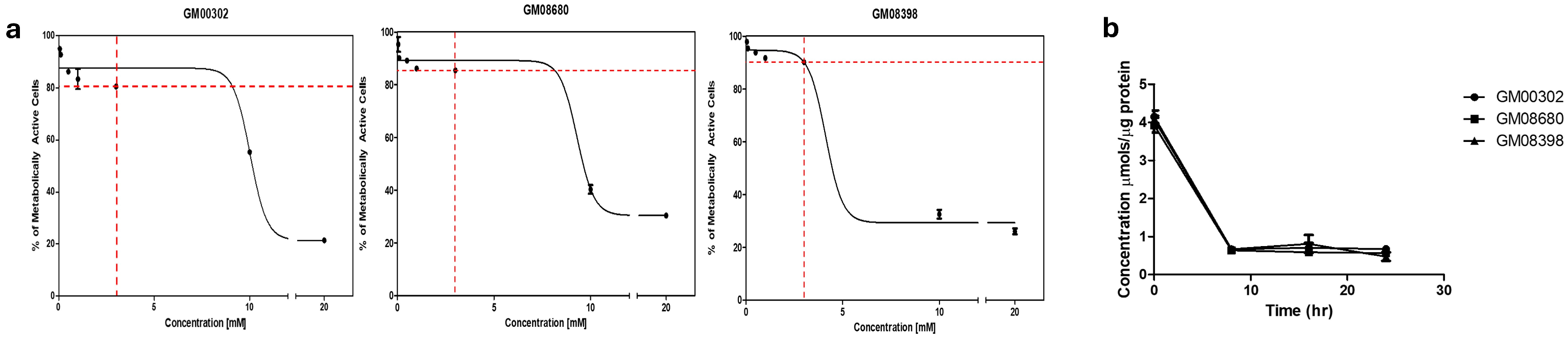

3.1. Establishing Dose-Dependent Curves

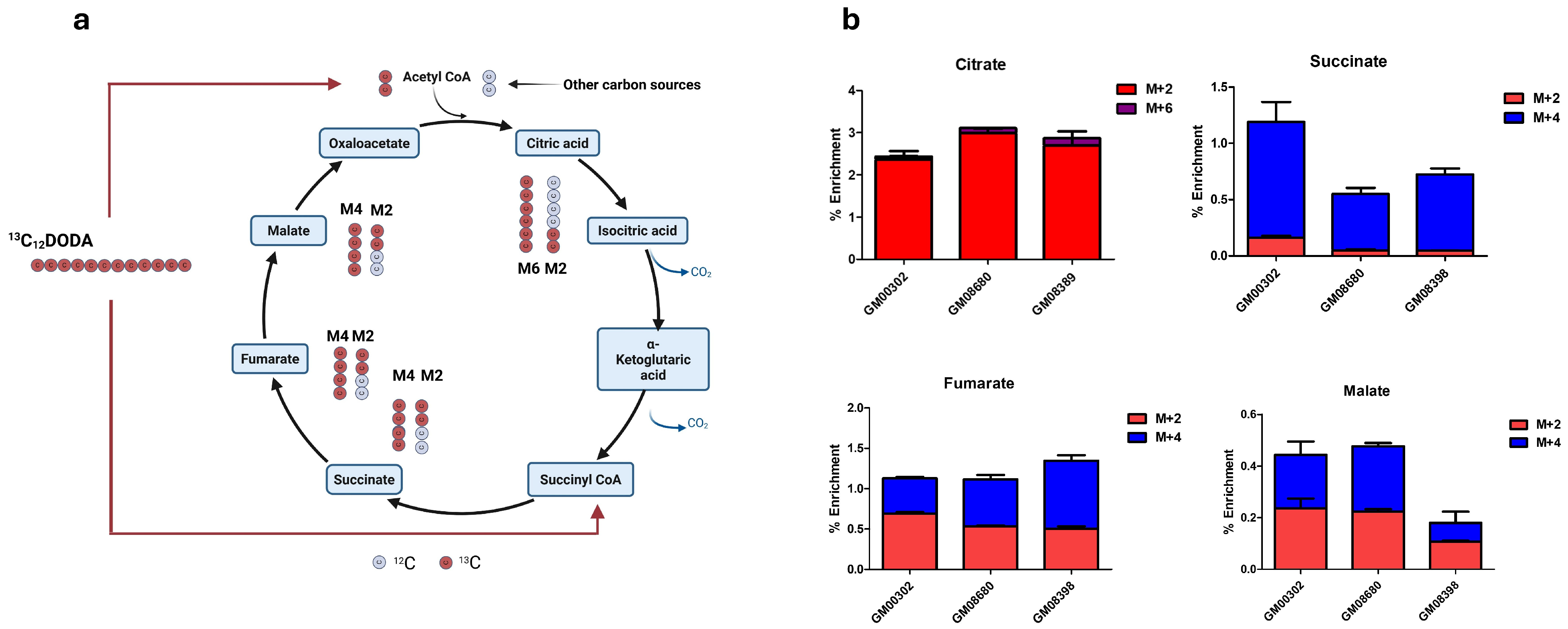

3.2. DODA Is Consumed by Fibroblasts and Its Carbons Refill Krebs Cycle

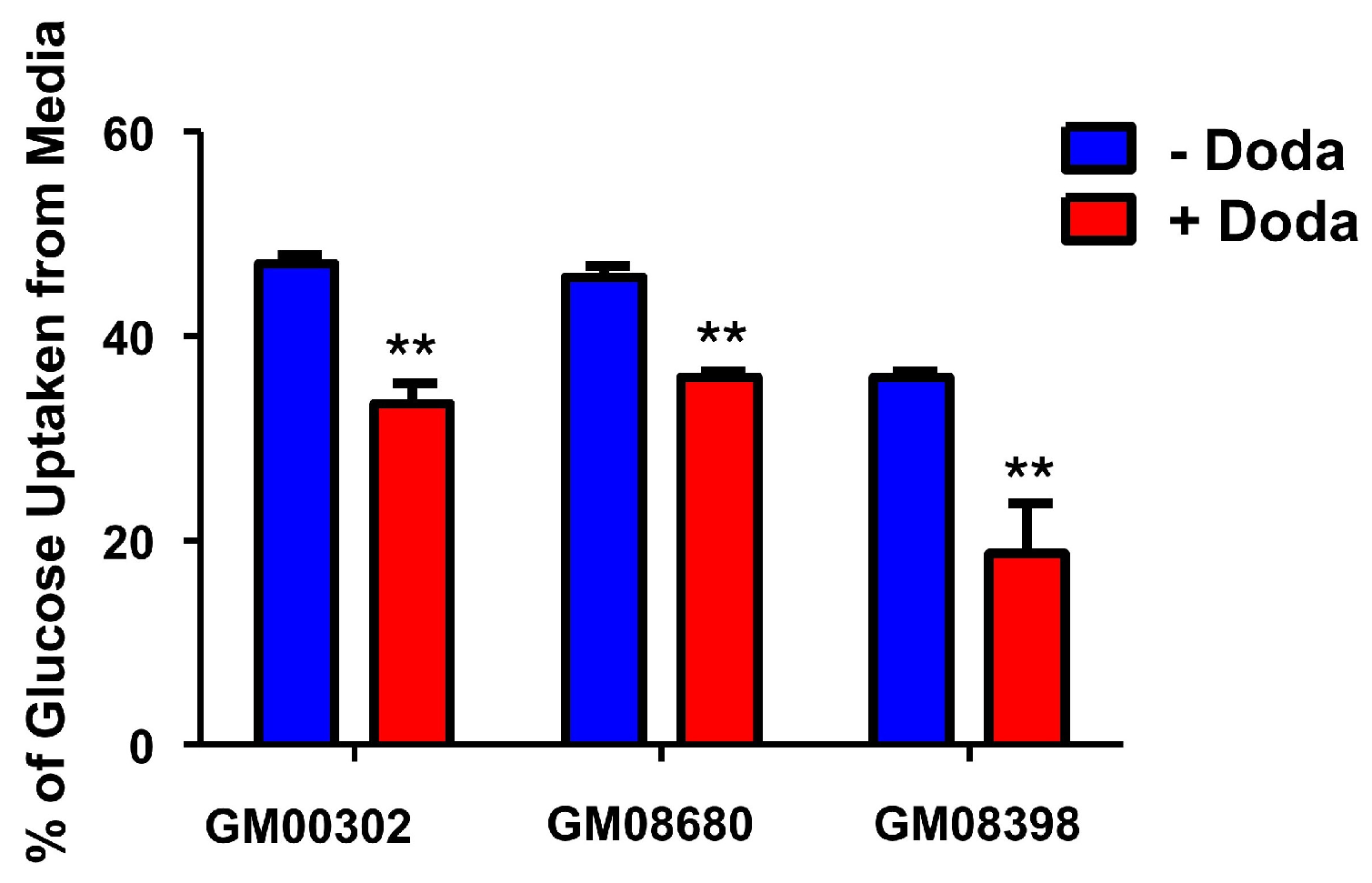

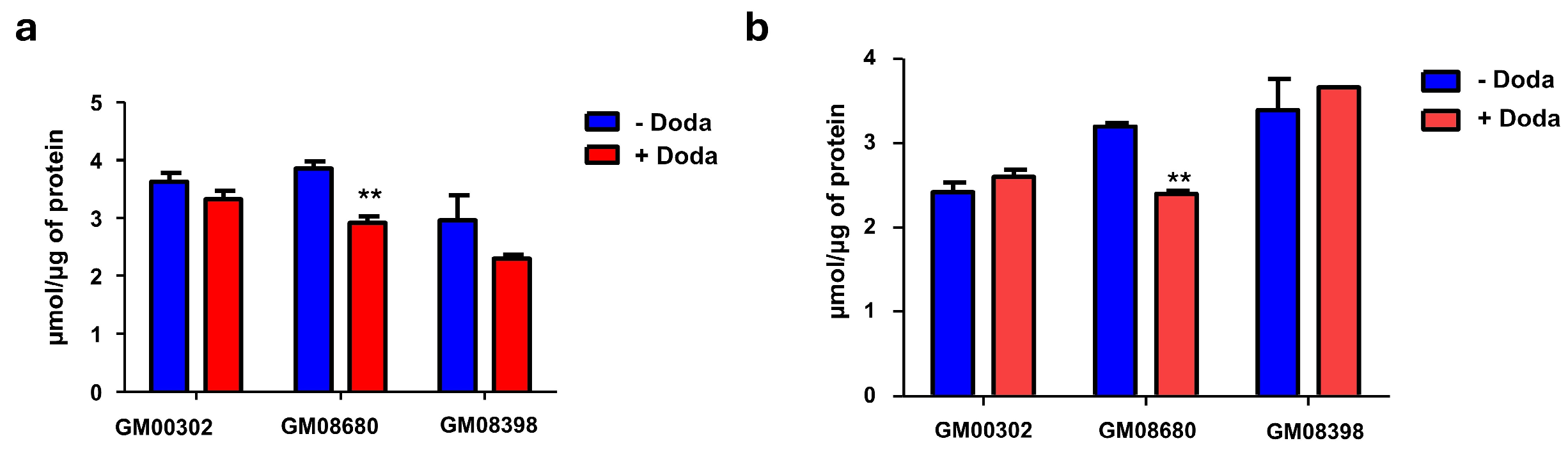

3.3. DODA Decreases Cellular Uptake of Glucose

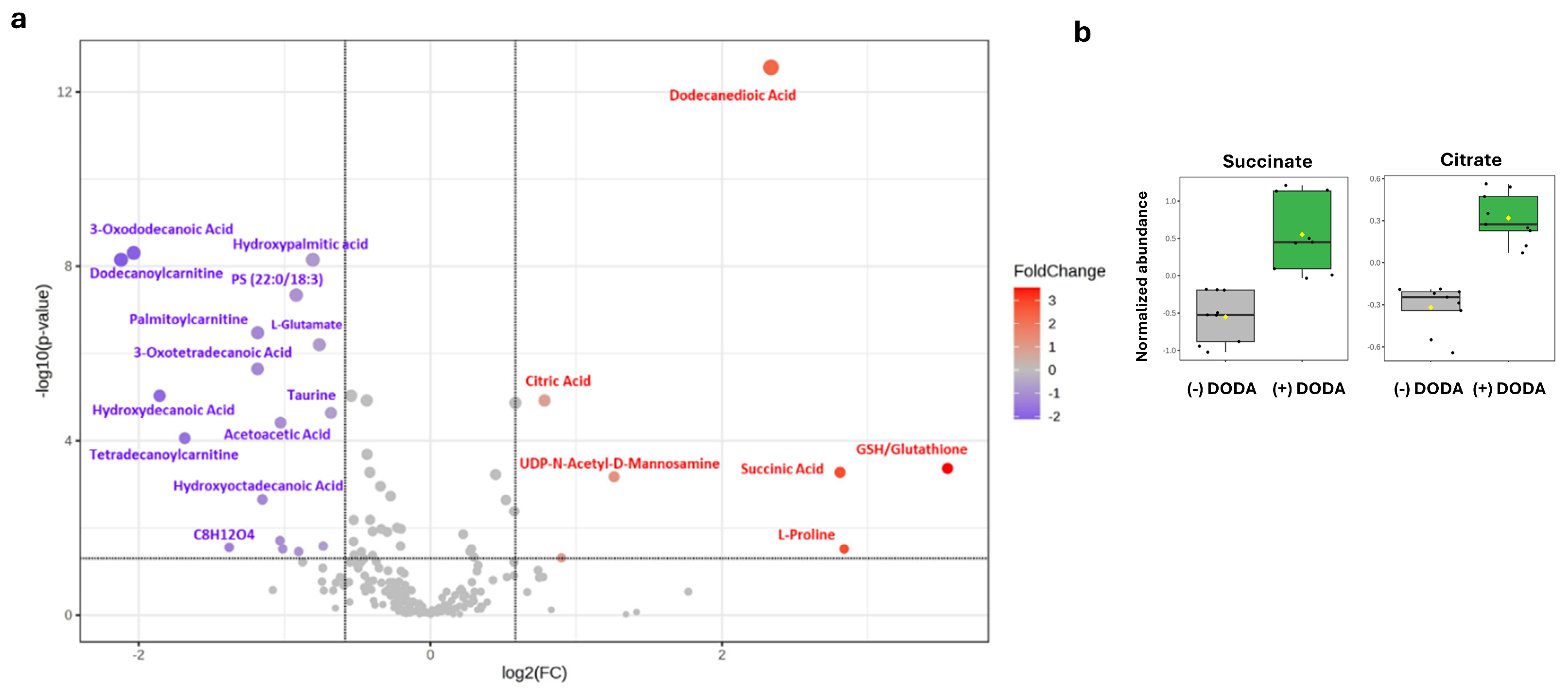

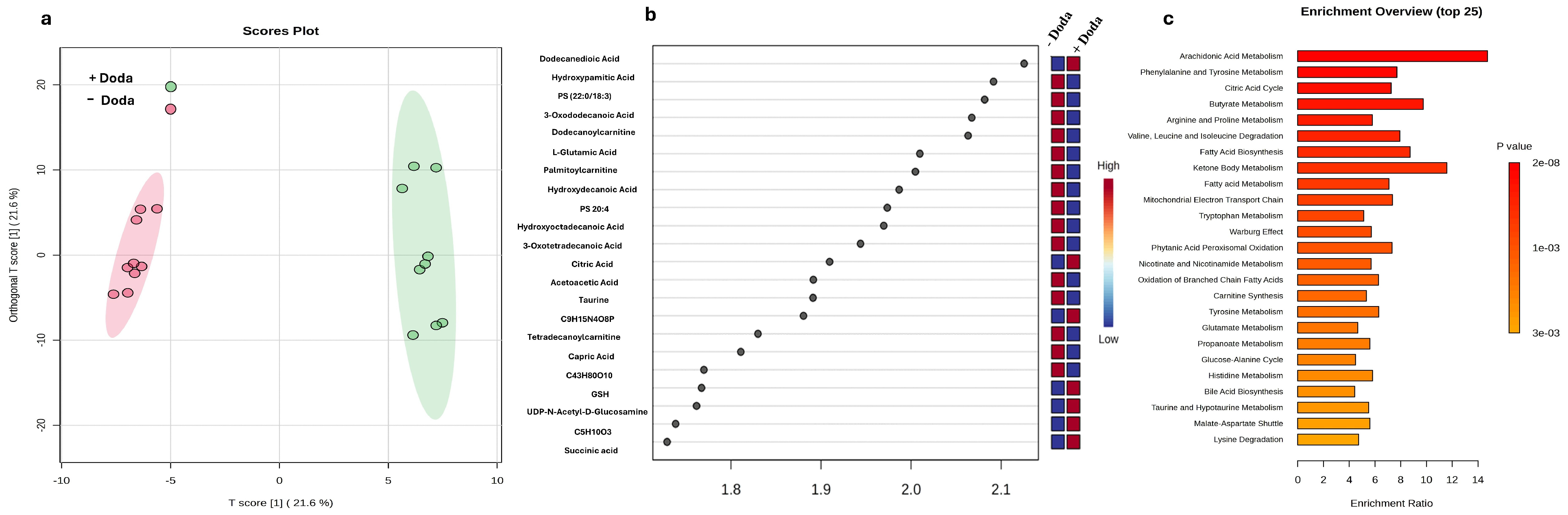

3.4. Changes in Metabolic and Lipid Profiles

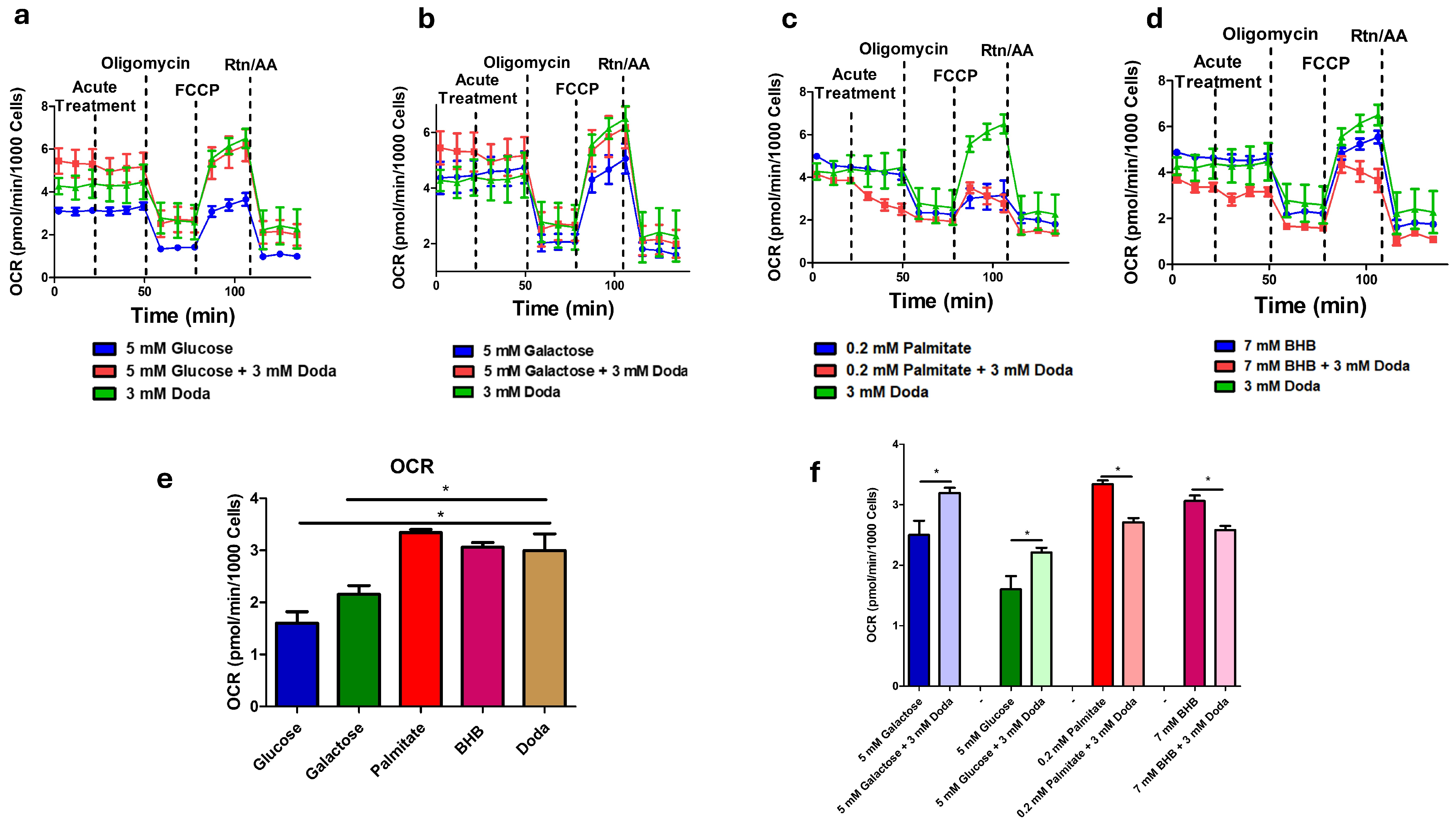

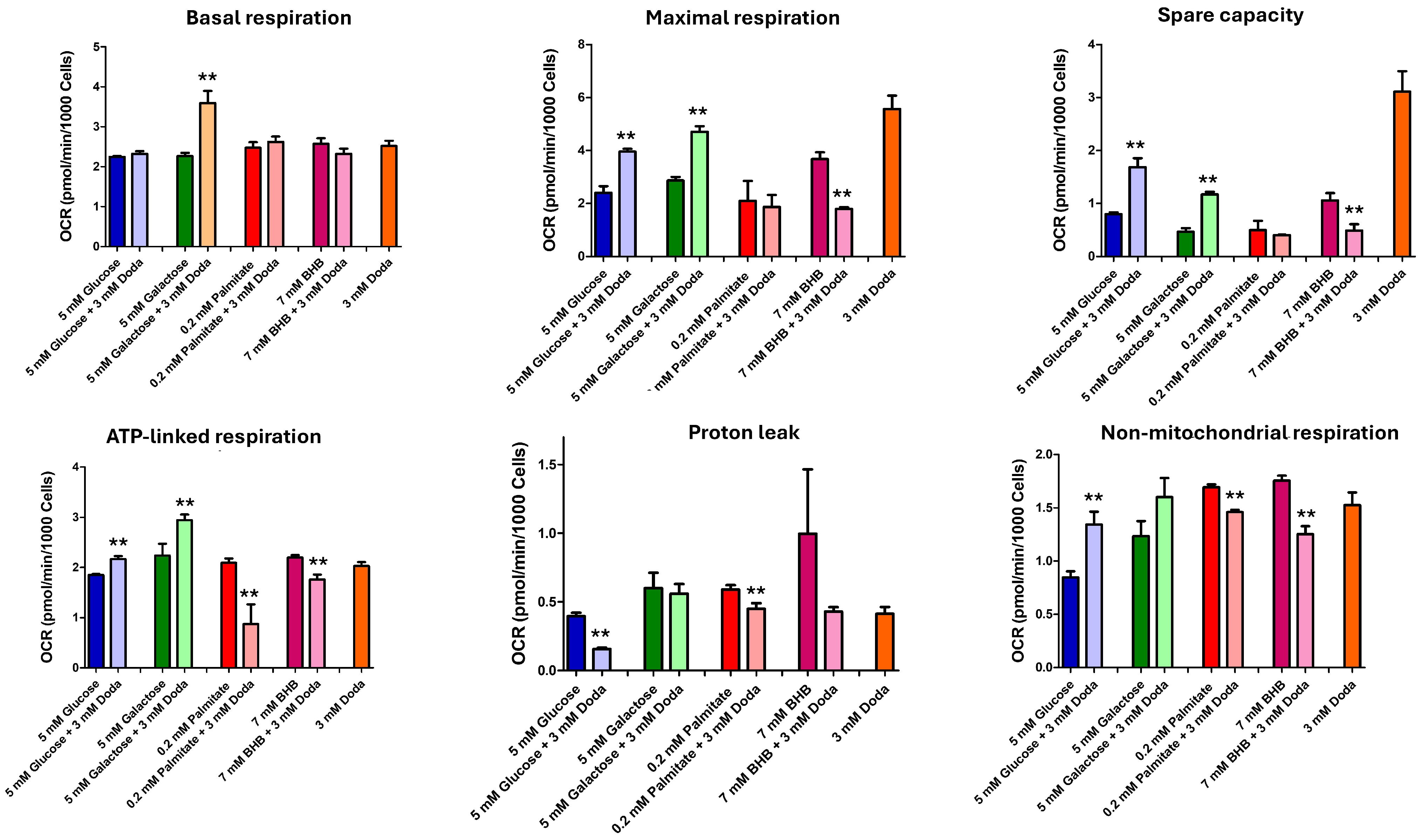

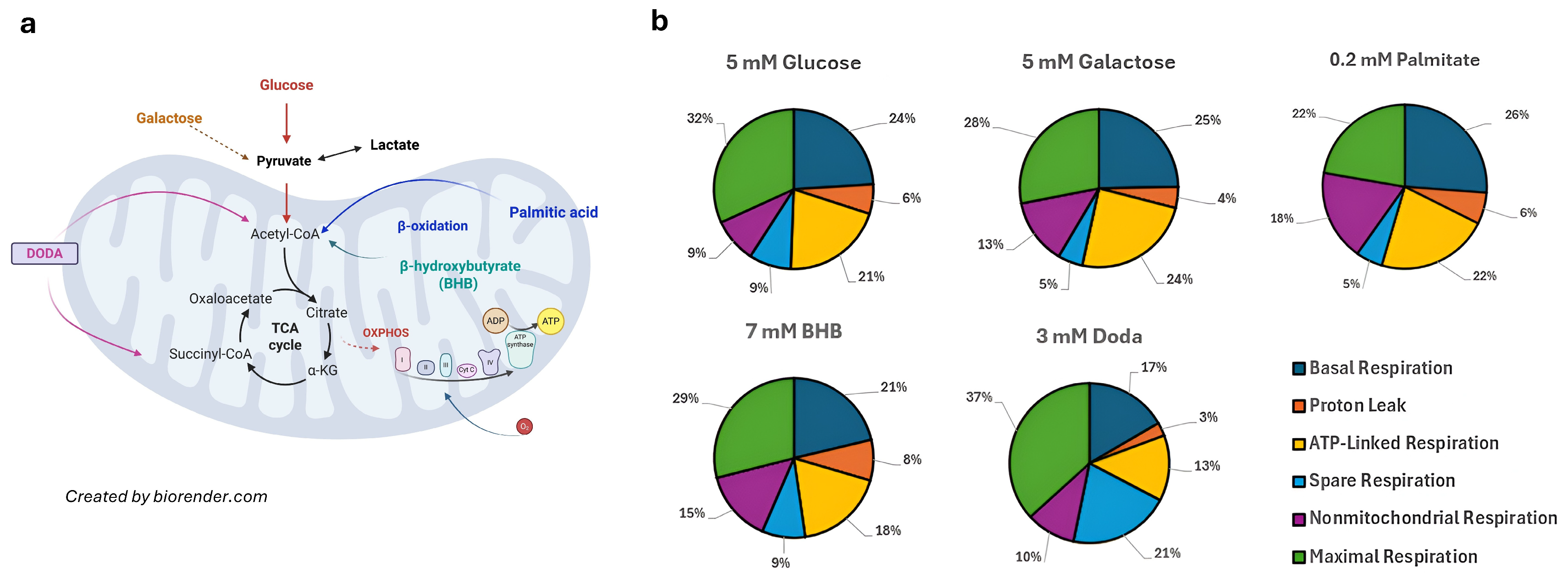

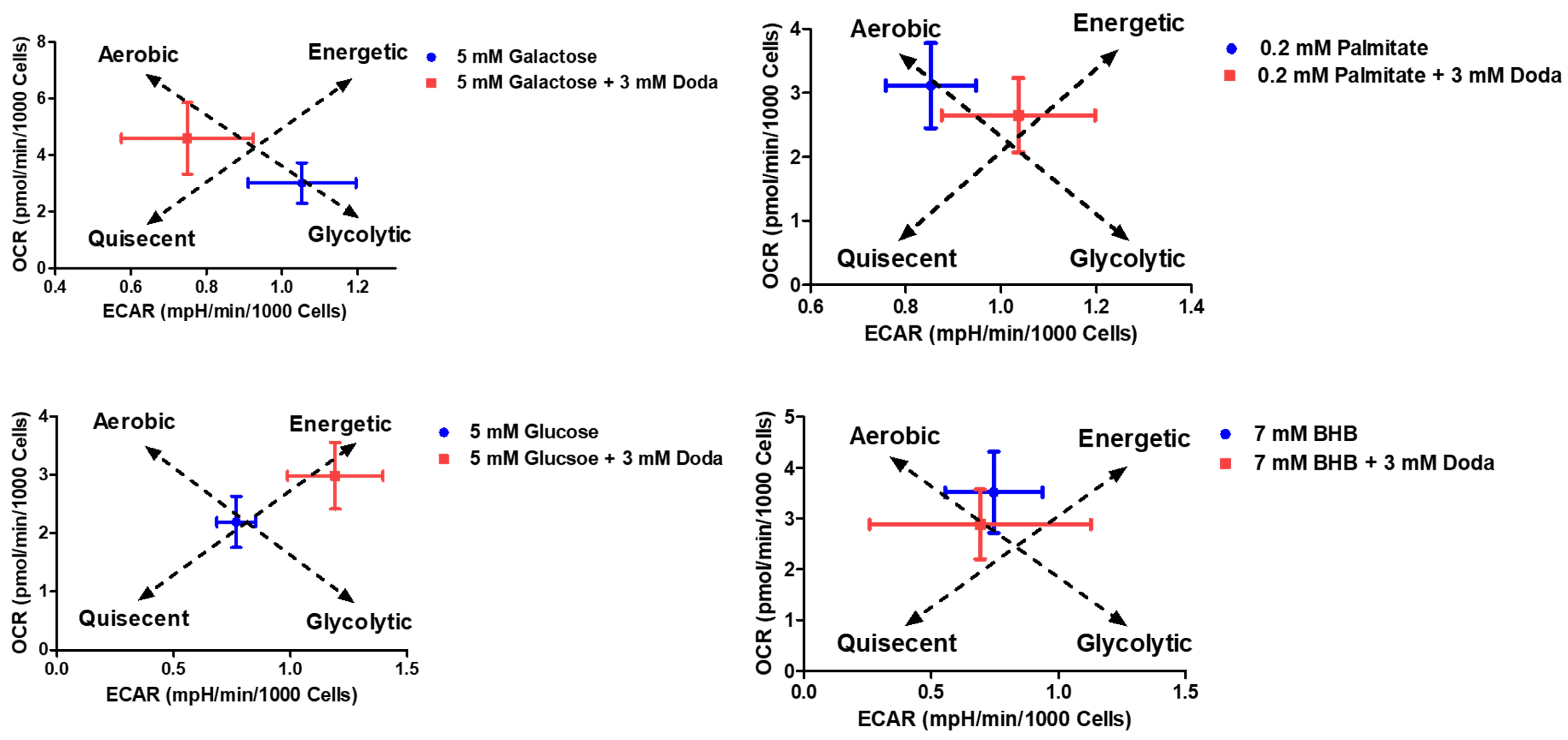

3.5. DODA Impact on Mitochondrial Bioenergetics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DODA | Dodecanedioic acid |

| GCMS | Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry |

| HILIC | Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography |

| MCAD | Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency |

| LCAD | Long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency |

| MADD | Multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| PBS | Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| MTBSTFA | N-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-N-methyltrifluoroacetamide |

| OCR | Oxygen Consumption Rate |

| ECAR | Extracellular Acidification Rate |

| FCCP | Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone |

| BHB | β-Hydroxybutyrate |

| VIP | Variable Importance in Projection |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis |

| LCACs | Long-chain Acylcarnitines |

| GSH | Reduced Glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized Glutathione |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| NADH/NAD+ | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (reduced/oxidized forms) |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative Phosphorylation |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

References

- Tserng, K.Y.; Jin, S.J.; Kerr, D.S.; Hoppel, C.L. Urinary 3-Hydroxydicarboxylic Acids in Pathophysiology of Metabolic Disorders with Dicarboxylic Aciduria. Metabolism 1991, 40, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tserng, K.Y.; Jin, S.J.; Kerr, D.S.; Hoppel, C.L. Abnormal Urinary Excretion of Unsaturated Dicarboxylic Acids in Patients with Medium-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency. J. Lipid Res. 1990, 31, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, M.; De Klerk, J.B.C.; Wadman, S.K.; Bruinvis, L.; Ketting, D. The Differential Diagnosis of Dicarboxylic Aciduria. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1984, 7, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajner, M.; Amaral, A.U. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Fatty Acid Oxidation Disorders: Insights from Human and Animal Studies. Biosci. Rep. 2016, 36, e00281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranea-Robles, P.; Houten, S.M. The Biochemistry and Physiology of Long-Chain Dicarboxylic Acid Metabolism. Biochem. J. 2023, 480, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sala, P.; Peña-Quintana, L. Biochemical Markers for the Diagnosis of Mitochondrial Fatty Acid Oxidation Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grego, A.V.; Mingrone, G. Dicarboxylic Acids, an Alternate Fuel Substrate in Parenteral Nutrition: An Update. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 14, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, G.; Russo, S.; Carli, F.; Infelise, P.; Panunzi, S.; Bertuzzi, A.; Caristo, M.E.; Lembo, E.; Calce, R.; Bornstein, S.R.; et al. Dodecanedioic Acid Prevents and Reverses Metabolic-Associated Liver Disease and Obesity and Ameliorates Liver Fibrosis in a Rodent Model of Diet-Induced Obesity. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e70202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, A.; Mingrone, G.; De Gaetano, A.; Gandolfi, A.; Greco, A.V.; Salinari, S. Kinetics of Dodecanedioic Acid and Effect of Its Administration on Glucose Kinetics in Rats. Br. J. Nutr. 1997, 78, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingrone, G.; Greco, A.; De Gaetano, A.; Tataranni, A.; Raguso, C.; Castagneto, M. Pharmacokinetic Profile of Dodecanedioic Acid, a Proposed Alternative Fuel Substrate. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 1994, 18, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingrone, G.; Castagneto, M. Medium-Chain, Even-Numbered Dicarboxylic Acids as Novel Energy Substrates: An Update. Nutr. Rev. 2006, 64, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tserngg, K.-Y.; Jin, S.-J. Metabolic Conversion of Dicarboxylic Acids to Succinate in Rat Liver Homogenates. A Stable Isotope Tracer Study. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 2924–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, O.E.; Kalhan, S.C.; Hanson, R.W. The Key Role of Anaplerosis and Cataplerosis for Citric Acid Cycle Function. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 30409–30412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibala, M.J.; Young, M.E.; Taegtmeyer, H. Anaplerosis of the Citric Acid Cycle: Role in Energy Metabolism of Heart and Skeletal Muscle. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2000, 168, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, C.R.; Mochel, F. Anaplerotic Diet Therapy in Inherited Metabolic Disease: Therapeutic Potential. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2006, 29, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallet, R.T.; Olivencia-Yurvati, A.H.; Bünger, R. Pyruvate Enhancement of Cardiac Performance: Cellular Mechanisms and Clinical Application. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018, 243, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, N.; Price, L.B.; Gappmaier, E.; Cantor, N.L.; Ernst, S.L.; Bailey, C.; Pasquali, M. Anaplerotic Therapy in Propionic Acidemia. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 122, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, C.R.; Brunengraber, H. Anaplerotic Treatment of Long-Chain Fat Oxidation Disorders with Triheptanoin: Review of 15 Years Experience. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2015, 116, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, Z.; Tucci, S. Therapeutic Potential of Triheptanoin in Metabolic and Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 43, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.V.; Mingrone, G.; Capristo, E.; Benedetti, G.; De Gaetano, A.; Gasbarrini, G. The Metabolic Effect of Dodecanedioic Acid Infusion in Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients. Nutrition 1998, 14, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingrone, G.; Castagneto-Gissey, L.; Macé, K. Use of Dicarboxylic Acids in Type 2 Diabetes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzman, E.S.; Zhang, B.B.; Zhang, Y.; Bharathi, S.S.; Bons, J.; Rose, J.; Shah, S.; Solo, K.J.; Schmidt, A.V.; Richert, A.C.; et al. Dietary Dicarboxylic Acids Provide a Non-Storable Alternative Fat Source That Protects Mice against Obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e174186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Yao, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shang, L.; Chen, X.; Zeng, J. Long-Chain Dicarboxylic Acids Play a Critical Role in Inducing Peroxisomal β-Oxidation and Hepatic Triacylglycerol Accumulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, T.; Deng, S.; Shang, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, K.; Li, P.; Cui, X.; Zeng, J. Fasting Induces Hepatic Lipid Accumulation by Stimulating Peroxisomal Dicarboxylic Acid Oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pons, R.; Cavadini, P.; Baratta, S.; Invernizzi, F.; Lamantea, E.; Garavaglia, B.; Taroni, F. Clinical and Molecular Heterogeneity in Very-Long-Chain Acyl-Coenzyme A Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Pediatr. Neurol. 2000, 22, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonsgard, J.H.; Mendelson, S.A.; Meredith, S.C. Binding of Straight-Chain Saturated Dicarboxylic Acids to Albumin. J. Clin. Investig. 1988, 82, 1567–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonsgard, J.H.; Getz, G.S. Effect of Reye’s Syndrome Serum on Isolated Chinchilla Liver Mitochondria. J. Clin. Investig. 1985, 76, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, M.A.; Villavicencio-Tejo, F.; Quintanilla, R.A. The Use of Fibroblasts as a Valuable Strategy for Studying Mitochondrial Impairment in Neurological Disorders. Transl. Neurodegener. 2022, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, P.G.; Van den Bogert, C.; Bolhuis, P.A.; Scholte, H.R.; van Gennip, A.H.; Schutgens, R.B.; Ketel, A.G. X-Linked Cardioskeletal Myopathy and Neutropenia (Barth Syndrome): Respiratory-Chain Abnormalities in Cultured Fibroblasts. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1996, 19, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djouadi, F.; Habarou, F.; Le Bachelier, C.; Ferdinandusse, S.; Schlemmer, D.; Benoist, J.F.; Boutron, A.; Andresen, B.S.; Visser, G.; de Lonlay, P.; et al. Mitochondrial Trifunctional Protein Deficiency in Human Cultured Fibroblasts: Effects of Bezafibrate. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2016, 39, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ho, E.S.; Cotticelli, M.G.; Xu, P.; Napierala, J.S.; Hauser, L.A.; Napierala, M.; Himes, B.E.; Wilson, R.B.; Lynch, D.R.; et al. Skin Fibroblast Metabolomic Profiling Reveals That Lipid Dysfunction Predicts the Severity of Friedreich’s Ataxia. J. Lipid Res. 2022, 63, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, R.; Khairallah, M.; Cameron, J.M.; Pencharz, P.B.; Rosiers, C.D.; Robinson, B.H. Probing Pyruvate Metabolism in Normal and Mutant Fibroblast Cell Lines Using 13C-Labeled Mass Isotopomer Analysis and Mass Spectrometry. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2009, 98, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kølvraa, S.; Gregersen, N.; Christensen, E.; Hobolth, N. In Vitro Fibroblast Studies in a Patient with C6-C10-Dicarboxylic Aciduria: Evidence for a Defect in General Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase. Clin. Chim. Acta 1982, 126, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannibal, L.; Theimer, J.; Wingert, V.; Klotz, K.; Bierschenk, I.; Nitschke, R.; Spiekerkoetter, U.; Grünert, S.C. Metabolic Profiling in Human Fibroblasts Enables Subtype Clustering in Glycogen Storage Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alatibi, K.I.; Hagenbuchner, J.; Wehbe, Z.; Karall, D.; Ausserlechner, M.J.; Vockley, J.; Spiekerkoetter, U.; Grünert, S.C.; Tucci, S. Different Lipid Signature in Fibroblasts of Long-Chain Fatty Acid Oxidation Disorders. Cells 2021, 10, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junghans, P.; Görs, S.; Lang, I.S.; Steinhoff, J.; Hammon, H.M.; Metges, C.C. A Simplified Mass Isotopomer Approach to Estimate Gluconeogenesis Rate in Vivo Using Deuterium Oxide. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 24, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, A.; Fatica, E.; Shah, R.; Stergar, J.; Pearce, R.; Sandlers, Y. A Protocol for Metabolic Characterization of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes (iPS-CM). MethodsX 2019, 7, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Bian, F.; Tomcik, K.; Kelleher, J.K.; Zhang, G.-F.; Brunengraber, H. Compartmentation of Metabolism of the C12-, C9-, and C5-n-Dicarboxylates in Rat Liver, Investigated by Mass Isotopomer Analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18671–18677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, S.S.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, Z.; Muzumdar, R.; Goetzman, E.S. Role of Mitochondrial Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenases in the Metabolism of Dicarboxylic Fatty Acids. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 527, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepinsh, E.; Makrecka-Kuka, M.; Volska, K.; Kuka, J.; Makarova, E.; Antone, U.; Sevostjanovs, E.; Vilskersts, R.; Strods, A.; Tars, K.; et al. Long-Chain Acylcarnitines Determine Ischaemia/Reperfusion-Induced Damage in Heart Mitochondria. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefort, B.; Issa, J.; Blasco, H.; Labarthe, F. Heart Failure Is Associated with Accumulation of Long Chain Acylcarnitines in Children Suffering from Cardiomyopathy. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. Suppl. 2022, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Labarthe, F.; Fortier, A.; Bouchard, B.; Legault, J.T.; Bolduc, V.; Rigal, O.; Chen, J.; Ducharme, A.; Crawford, P.A.; et al. Circulating Acylcarnitine Profile in Human Heart Failure: A Surrogate of Fatty Acid Metabolic Dysregulation in Mitochondria and Beyond. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2017, 313, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, T.; Kelly, J.P.; McGarrah, R.W.; Hellkamp, A.S.; Fiuzat, M.; Testani, J.M.; Wang, T.S.; Verma, A.; Samsky, M.D.; Donahue, M.P.; et al. Prognostic Implications of Long-Chain Acylcarnitines in Heart Failure and Reversibility with Mechanical Circulatory Support. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken-Buck, H.M.; Krause, J.; Zeller, T.; Jones, P.P.; Lamberts, R.R. Long-Chain Acylcarnitines and Cardiac Excitation-Contraction Coupling: Links to Arrhythmias. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepinsh, E.; Kuka, J.; Vilks, K.; Svalbe, B.; Stelfa, G.; Vilskersts, R.; Sevostjanovs, E.; Goldins, N.R.; Groma, V.; Grinberga, S.; et al. Low Cardiac Content of Long-Chain Acylcarnitines in TMLHE Knockout Mice Prevents Ischaemia-Reperfusion-Induced Mitochondrial and Cardiac Damage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 177, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuka, J.; Makrecka-Kuka, M.; Cirule, H.; Grinberga, S.; Sevostjanovs, E.; Dambrova, M.; Liepinsh, E. Decrease in Long-Chain Acylcarnitine Tissue Content Determines the Duration of and Correlates with the Cardioprotective Effect of Methyl-GBB. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 121, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzikh, I.; Fatica, E.; Kodger, J.; Shah, R.; Pearce, R.; Sandlers, Y.I. Metabolic Outcomes of Anaplerotic Dodecanedioic Acid Supplementation in Very Long Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase (VLCAD) Deficient Fibroblasts. Metabolites 2021, 11, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makievskaya, C.I.; Popkov, V.A.; Andrianova, N.V.; Liao, X.; Zorov, D.B.; Plotnikov, E.Y. Ketogenic Diet and Ketone Bodies against Ischemic Injury: Targets, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, F.V.; Ruiter, J.P.N.; IJlst, L.; de Almeida, I.T.; Wanders, R.J.A. Lactic Acidosis in Long-Chain Fatty Acid Beta-Oxidation Disorders. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1998, 21, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, M.K. Presentation and Diagnosis of Mitochondrial Disorders in Children. Pediatr. Neurol. 2008, 38, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cade, W.T.; Bohnert, K.L.; Peterson, L.R.; Patterson, B.W.; Bittel, A.J.; Okunade, A.L.; de las Fuentes, L.; Steger-May, K.; Bashir, A.; Schweitzer, G.G.; et al. Blunted Fat Oxidation upon Submaximal Exercise Is Partially Compensated by Enhanced Glucose Metabolism in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults with Barth Syndrome. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.M.; Bennett, M.J. Disorders of Mitochondrial Fatty Acid β-Oxidation. In Biomarkers in Inborn Errors of Metabolism; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillmore, N.; Levasseur, J.L.; Fukushima, A.; Wagg, C.S.; Wang, W.; Dyck, J.R.B.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Uncoupling of Glycolysis from Glucose Oxidation Accompanies the Development of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhu, T.; Huang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Luo, F. Current Understanding of the Contribution of Lactate to the Cardiovascular System and Its Therapeutic Relevance. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1205442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopaschuk, G.D.; Karwi, Q.G.; Tian, R.; Wende, A.R.; Abel, E.D. Cardiac Energy Metabolism in Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1487–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, A.U.; Cecatto, C.; Da Silva, J.C.; Wajner, A.; Wajner, M. Mechanistic Bases of Neurotoxicity Provoked by Fatty Acids Accumulating in MCAD and LCHAD Deficiencies. J. Inborn Errors Metab. Screen. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonin, A.M.; Amaral, A.U.; Busanello, E.N.B.; Grings, M.; Castilho, R.F.; Wajner, M. Long-Chain 3-Hydroxy Fatty Acids Accumulating in Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase and Mitochondrial Trifunctional Protein Deficiencies Uncouple Oxidative Phosphorylation in Heart Mitochondria. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2013, 45, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillmore, N.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Targeting Mitochondrial Oxidative Metabolism as an Approach to Treat Heart Failure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Res. 2013, 1833, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassiri, S.; Van De Bovenkamp, A.A.; Remmelzwaal, S.; Sorea, O.; De Man, F.; Handoko, M.L. Effects of Trimetazidine on Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction and Associated Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Open Heart 2024, 11, e002579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragasso, G.; Spoladore, R.; Cuko, A.; Palloshi, A. Modulation of Fatty Acids Oxidation in Heart Failure by Selective Pharmacological Inhibition of 3-Ketoacyl Coenzyme-A Thiolase. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 2, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.S.; Guo, L.; Ghassemi, S.; Snyder, N.W.; Worth, A.J.; Weng, L.; Kam, Y.; Philipson, B.; Trefely, S.; Nunez-Cruz, S.; et al. The CPT1a Inhibitor, Etomoxir Induces Severe Oxidative Stress at Commonly Used Concentrations. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, P.J.; Kirk, T.; Ashmore, T.; Willerton, K.; Evans, R.; Smith, A.; Murray, A.J.; Stubbs, B.; West, J.; McLure, S.W.; et al. Nutritional Ketosis Alters Fuel Preference and Thereby Endurance Performance in Athletes. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleeker, J.C.; Visser, G.; Clarke, K.; Ferdinandusse, S.; de Haan, F.H.; Houtkooper, R.H.; IJlst, L.; Kok, I.L.; Langeveld, M.; van der Pol, W.L.; et al. Nutritional Ketosis Improves Exercise Metabolism in Patients with Very Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020, 43, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, S.A.; Vanitallie, T.B.; Luke’s-, S.; Hospital, R. Ketone Body Therapy: From the Ketogenic Diet to the Oral Administration of Ketone Ester. J. Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 1818–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veech, R.L. The Therapeutic Implications of Ketone Bodies: The Effects of Ketone Bodies in Pathological Conditions: Ketosis, Ketogenic Diet, Redox States, Insulin Resistance, and Mitochondrial Metabolism. Prostagland. Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2004, 70, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, K.L.; Karwi, Q.G.; Wang, F.; Wagg, C.; Zhang, L.; Panidarapu, S.; Chen, B.; Pherwani, S.; Greenwell, A.A.; Oudit, G.Y.; et al. The Ketogenic Diet Does Not Improve Cardiac Function and Blunts Glucose Oxidation in Ischaemic Heart Failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, C.M.; Nisoli, E. The Ketogenic Diet Is Unable to Improve Cardiac Function in Ischaemic Heart Failure: An Unexpected Result? Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 1097–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, K.L.; Karwi, Q.G.; Wagg, C.; Zhang, L.; Vo, K.; Altamimi, T.; Uddin, G.M.; Ussher, J.R.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Ketones Can Become the Major Fuel Source for the Heart but Do Not Increase Cardiac Efficiency. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 117, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwi, Q.G.; Lopaschuk, G.D. CrossTalk Proposal: Ketone Bodies Are an Important Metabolic Fuel for the Heart. J. Physiol. 2022, 600, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.L.; Zhang, L.; Wagg, C.; Al Batran, R.; Gopal, K.; Levasseur, J.; Leone, T.; Dyck, J.R.B.; Ussher, J.R.; Muoio, D.M.; et al. Increased Ketone Body Oxidation Provides Additional Energy for the Failing Heart without Improving Cardiac Efficiency. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1606–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Radzikh, I.; Oyarbide, U.; Patil, A.S.; Sandlers, Y.I. Dodecanedioic Acid: Alternative Carbon Substrate or Toxic Metabolite? Biomolecules 2026, 16, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010057

Radzikh I, Oyarbide U, Patil AS, Sandlers YI. Dodecanedioic Acid: Alternative Carbon Substrate or Toxic Metabolite? Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadzikh, Igor, Usua Oyarbide, Akshay Suresh Patil, and Yana I. Sandlers. 2026. "Dodecanedioic Acid: Alternative Carbon Substrate or Toxic Metabolite?" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010057

APA StyleRadzikh, I., Oyarbide, U., Patil, A. S., & Sandlers, Y. I. (2026). Dodecanedioic Acid: Alternative Carbon Substrate or Toxic Metabolite? Biomolecules, 16(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010057