The RNA-Binding Protein KSRP Is a Negative Regulator of Innate Immunity

Abstract

1. Introduction

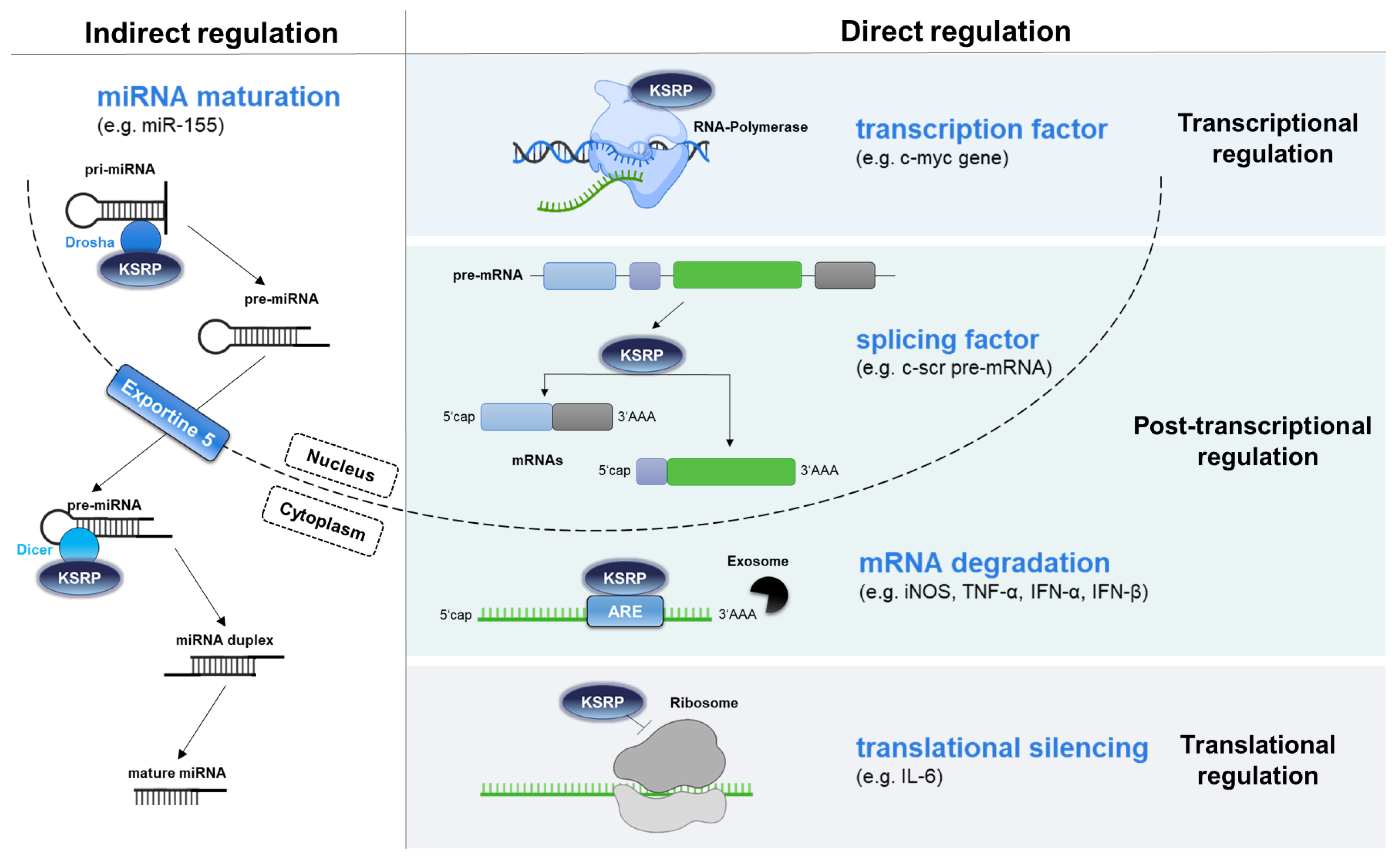

2. KH-Type Splicing Regulatory Protein (KSRP) Exerts Various Functions

3. Regulation of KSRP Activity

3.1. mRNA Level

3.2. Protein Level

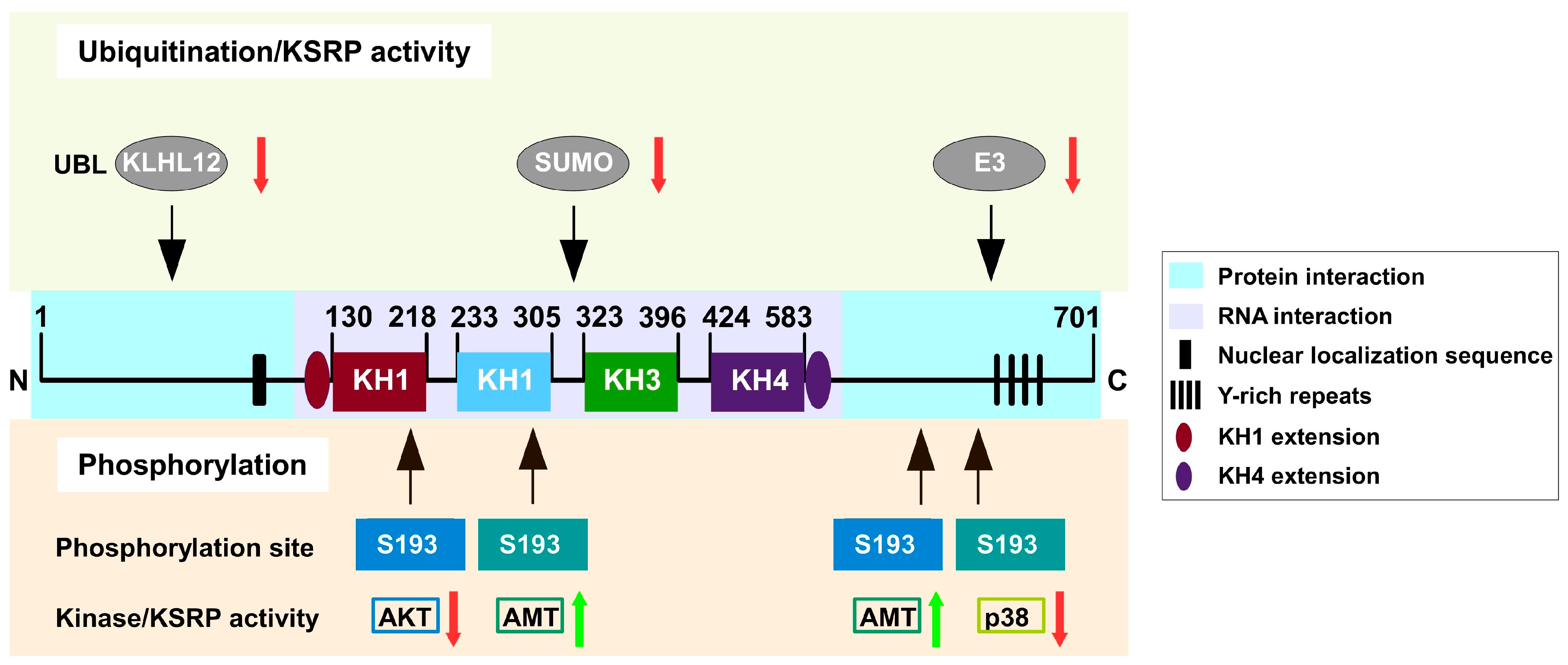

3.2.1. Phosphorylation

3.2.2. Ubiquitination and SUMOylation

3.2.3. Long Non-Coding RNAs

| lncRNA | Mechanism of Action | Functional Consequences | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| H19 | Sequesters KSRP, prevents its interaction with target mRNAs | Stabilization of Myogenin mRNA, thereby promoting skeletal muscle differentiation | [48] |

| EPR | Promotes proteasomal degradation of KSRP | Stabilization of p21 mRNA, thereby inhibiting epithelial proliferation | [49] |

| ALAE | Sequesters KSRP, reduces its mRNA decay function | Stabilization of Gap43 mRNA in axons | [50] |

4. KSRP as a Regulator of Innate Immune Responses

4.1. CAIA

4.2. KSRP Deficiency Led to Enhanced Generation of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Sepsis

4.3. KSRP Deficiency Inhibits IPA

| Disease Model | Immune Cell Types Examined | Immunophenotype Associated with KSRP Deficiency | Functional Effects and Disease Course (KSRP-Deficient vs. WT) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAIA | Joint infiltrates; splenic myeloid cells |

|

| [58] |

| LPS (in vitro) | BMDM; peritoneal MAC |

| - | [63] |

| PMN |

| - | [64] | |

| Sepsis | Systemic cytokine response; MAC-centric |

|

| [63] |

| A. fumigatus conidia (in vitro) | MAC, PMN |

| - | [64] |

| IPA | PMN; MAC (lung, BALF) |

|

|

5. Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFC | A. fumigatus conidia |

| ALAE | regulating axon elongation |

| AMD | ARE-mediated mRNA decay |

| AMT | ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase |

| AP-1 | Activator protein 1 |

| APC | antigen-presenting cells |

| ARE | adenine-uracil-rich element |

| AUF1 | ARE/poly(U)-binding degradation factor |

| CAIA | Collagen antibody-induced arthritis |

| CXCL1 | C-X-C-motif ligand 1 |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| EMT | epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| EPR | Epithelial Program Regulator |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte/Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| HuR | human antigen R |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IL | interleukin |

| ILC | Innate lymphoid cell |

| iNos2 | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IPA | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis |

| IRES | enterovirus internal ribosome entry site |

| ITAF | IRES trans-acting factor |

| KH | K homology |

| KLHL12 | Kelch-like protein 12 |

| KS(H)RP | KH-type splicing regulatory protein |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| mRNA | messenger RNA |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor ‘kappa-light-chain-enhancer’ of activated B-cells |

| NK | Natural killer |

| PKB | protein kinase B |

| PMN | polymorphonuclear neutrophils |

| RBP | RNA-binding protein |

| RIG-I | Retinoic acid-inducible gene I |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCF | S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 and cullin-1 F-box protein |

| STAT | Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription |

| SUMO | small ubiquitin-like modifier |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| TTP | Tristetraprolin |

| USE | Upstream sequence element |

| UTR | untranslated region |

| WT | Wild type |

References

- Leavenworth, J.D.; Yusuf, N.; Hassan, Q. K-Homology Type Splicing Regulatory Protein: Mechanism of Action in Cancer and Immune Disorders. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2024, 34, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherzi, R.; Chen, C.Y.; Ramos, A.; Briata, P. KSRP controls pleiotropic cellular functions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 34, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akira, S.; Maeda, K. Control of RNA Stability in Immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 39, 481–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linker, K.; Pautz, A.; Fechir, M.; Hubrich, T.; Greeve, J.; Kleinert, H. Involvement of KSRP in the post-transcriptional regulation of human iNOS expression-complex interplay of KSRP with TTP and HuR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 4813–4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtke, L.; Schrick, K.; Saurin, S.; Käfer, R.; Gather, F.; Weinmann-Menke, J.; Kleinert, H.; Pautz, A. The KH-type splicing regulatory protein (KSRP) regulates type III interferon expression post-transcriptionally. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamija, S.; Kuehne, N.; Winzen, R.; Doerrie, A.; Dittrich-Breiholz, O.; Thakur, B.K.; Kracht, M.; Holtmann, H. Interleukin-1 activates synthesis of interleukin-6 by interfering with a KH-type splicing regulatory protein (KSRP)-dependent translational silencing mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 33279–33288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, D.; Bin Jeon, H.; Oh, C.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, K.M. RNA-binding proteins in cellular senescence. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2023, 214, 111853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, T.; Trabucchi, M.; De Santa, F.; Zupo, S.; Harfe, B.D.; McManus, M.T.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Briata, P.; Gherzi, R. LPS induces KH-type splicing regulatory protein-dependent processing of microRNA-155 precursors in macrophages. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 2898–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Kumar, P.; Tsuchiya, M.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Biswas, R. Regulation of miR-155 biogenesis in cystic fibrosis lung epithelial cells: Antagonistic role of two mRNA-destabilizing proteins, KSRP and TTP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 433, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.H.; Chen, C.Y. Role of KSRP in control of type I interferon and cytokine expression. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014, 34, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palzer, K.A.; Bolduan, V.; Käfer, R.; Kleinert, H.; Bros, M.; Pautz, A. The Role of KH-Type Splicing Regulatory Protein (KSRP) for Immune Functions and Tumorigenesis. Cells 2022, 11, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Buchanan, C.N.; Zdradzinski, M.D.; Sahoo, P.K.; Kar, A.N.; Lee, S.J.; Vaughn, L.S.; Urisman, A.; Oses-Prieto, J.; Dell’Orco, M.; et al. Intra-axonal translation of Khsrp mRNA slows axon regeneration by destabilizing localized mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 5772–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.C.; Ho, K.H.; Hua, K.T.; Chien, M.H. Roles of K(H)SRP in modulating gene transcription throughout cancer progression: Insights from cellular studies to clinical perspectives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briata, P.; Chen, C.Y.; Ramos, A.; Gherzi, R. Functional and molecular insights into KSRP function in mRNA decay. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1829, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lellek, H.; Welker, S.; Diehl, I.; Kirsten, R.; Greeve, J. Reconstitution of mRNA editing in yeast using a Gal4-apoB-Gal80 fusion transcript as the selectable marker. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 23638–23644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzen, R.; Thakur, B.K.; Dittrich-Breiholz, O.; Shah, M.; Redich, N.; Dhamija, S.; Kracht, M.; Holtmann, H. Functional analysis of KSRP interaction with the AU-rich element of interleukin-8 and identification of inflammatory mRNA targets. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 8388–8400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, E.; Blackshear, P.J. Roles of tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor subtypes in the pathogenesis of the tristetraprolin-deficiency syndrome. Blood 2001, 98, 2389–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, E.; Lai, W.S.; Blackshear, P.J. Evidence that tristetraprolin is a physiological regulator of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor messenger RNA deadenylation and stability. Blood 2000, 95, 1891–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestehorn, A.; von Wirén, J.; Zeiler, C.; Fesselet, J.; Didusch, S.; Forte, M.; Doppelmayer, K.; Borroni, M.; Le Heron, A.; Scinicariello, S.; et al. Cytoplasmic mRNA decay controlling inflammatory gene expression is determined by pre-mRNA fate decision. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 742–755.e749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, M.; D’Silva, N.J.; Kirkwood, K.L. Tristetraprolin regulates interleukin-6 expression through p38 MAPK-dependent affinity changes with mRNA 3′ untranslated region. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011, 31, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Y.; Sadri, N.; Schneider, R.J. Endotoxic shock in AUF1 knockout mice mediated by failure to degrade proinflammatory cytokine mRNAs. Genes. Dev. 2006, 20, 3174–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podszywalow-Bartnicka, P.; Neugebauer, K.M. Multiple roles for AU-rich RNA binding proteins in the development of haematologic malignancies and their resistance to chemotherapy. RNA Biol. 2024, 21, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabar, K.S.; Bakheet, T.; Williams, B.R. AU-rich transient response transcripts in the human genome: Expressed sequence tag clustering and gene discovery approach. Genomics 2005, 85, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabucchi, M.; Briata, P.; Garcia-Mayoral, M.; Haase, A.D.; Filipowicz, W.; Ramos, A.; Gherzi, R.; Rosenfeld, M.G. The RNA-binding protein KSRP promotes the biogenesis of a subset of microRNAs. Nature 2009, 459, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulei, D.; Raduly, L.; Broseghini, E.; Ferracin, M.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. The extensive role of miR-155 in malignant and non-malignant diseases. Mol. Asp. Med. 2019, 70, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazarlou, F.; Kadkhoda, S.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. Emerging role of let-7 family in the pathogenesis of hematological malignancies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, B.; Tang, X.; Wang, Y. Role of microRNA-129 in cancer and non-cancerous diseases (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirouche, A.; Tadesse, H.; Miura, P.; Bélanger, G.; Lunde, J.A.; Côté, J.; Jasmin, B.J. Converging pathways involving microRNA-206 and the RNA-binding protein KSRP control post-transcriptionally utrophin A expression in skeletal muscle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 3982–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Gong, A.Y.; Eischeid, A.N.; Chen, X.M. miR-27b targets KSRP to coordinate TLR4-mediated epithelial defense against Cryptosporidium parvum infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppo, M.; Bucci, G.; Rossi, M.; Giovarelli, M.; Bordo, D.; Moshiri, A.; Gorlero, F.; Gherzi, R.; Briata, P. miRNA-Mediated KHSRP Silencing Rewires Distinct Post-transcriptional Programs during TGF-β-Induced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullmann, R., Jr.; Kim, H.H.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Lal, A.; Martindale, J.L.; Yang, X.; Gorospe, M. Analysis of turnover and translation regulatory RNA-binding protein expression through binding to cognate mRNAs. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 6265–6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briata, P.; Forcales, S.V.; Ponassi, M.; Corte, G.; Chen, C.Y.; Karin, M.; Puri, P.L.; Gherzi, R. p38-dependent phosphorylation of the mRNA decay-promoting factor KSRP controls the stability of select myogenic transcripts. Mol. Cell 2005, 20, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briata, P.; Lin, W.J.; Giovarelli, M.; Pasero, M.; Chou, C.F.; Trabucchi, M.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Chen, C.Y.; Gherzi, R. PI3K/AKT signaling determines a dynamic switch between distinct KSRP functions favoring skeletal myogenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Q. ATM signals miRNA biogenesis through KSRP. Mol. Cell 2011, 41, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Moreno, I.; Hollingworth, D.; Frenkiel, T.A.; Kelly, G.; Martin, S.; Howell, S.; García-Mayoral, M.; Gherzi, R.; Briata, P.; Ramos, A. Phosphorylation-mediated unfolding of a KH domain regulates KSRP localization via 14-3-3 binding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briata, P.; Bordo, D.; Puppo, M.; Gorlero, F.; Rossi, M.; Perrone-Bizzozero, N.; Gherzi, R. Diverse roles of the nucleic acid-binding protein KHSRP in cell differentiation and disease. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2016, 7, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danckwardt, S.; Gantzert, A.S.; Macher-Goeppinger, S.; Probst, H.C.; Gentzel, M.; Wilm, M.; Gröne, H.J.; Schirmacher, P.; Hentze, M.W.; Kulozik, A.E. p38 MAPK controls prothrombin expression by regulated RNA 3′ end processing. Mol. Cell 2011, 41, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollmann, F.; Art, J.; Henke, J.; Schrick, K.; Besche, V.; Bros, M.; Li, H.; Siuda, D.; Handler, N.; Bauer, F.; et al. Resveratrol post-transcriptionally regulates pro-inflammatory gene expression via regulation of KSRP RNA binding activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 12555–12569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshiri, A.; Puppo, M.; Rossi, M.; Gherzi, R.; Briata, P. Resveratrol limits epithelial to mesenchymal transition through modulation of KHSRP/hnRNPA1-dependent alternative splicing in mammary gland cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2017, 1860, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.J.; Rahimi, N.; Tadi, P. Biochemistry, Ubiquitination. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, C.P.; MacGurn, J.A. Coupling Conjugation and Deconjugation Activities to Achieve Cellular Ubiquitin Dynamics. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020, 45, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y.; Li, M.L.; Shih, S.R. Far upstream element binding protein 2 interacts with enterovirus 71 internal ribosomal entry site and negatively regulates viral translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, Y.A.; Hung, C.T.; Chien, K.Y.; Shih, S.R. Control of the negative IRES trans-acting factor KHSRP by ubiquitination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Deng, R.; Zhao, X.; Chen, R.; Hou, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, M.; Jiang, B.; Yu, J. SUMO1 modification of KHSRP regulates tumorigenesis by preventing the TL-G-Rich miRNA biogenesis. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.M.; Yeh, E.T.H. SUMO: From Bench to Bedside. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 1599–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Chao, Y.; Liang, M.; Zhang, F.; Huang, K. E3 Ligase FBXW2 Is a New Therapeutic Target in Obesity and Atherosclerosis. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N. Role of mammalian long non-coding RNAs in normal and neuro oncological disorders. Genomics 2021, 113, 3250–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovarelli, M.; Bucci, G.; Ramos, A.; Bordo, D.; Wilusz, C.J.; Chen, C.Y.; Puppo, M.; Briata, P.; Gherzi, R. H19 long noncoding RNA controls the mRNA decay promoting function of KSRP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E5023–E5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Bucci, G.; Rizzotto, D.; Bordo, D.; Marzi, M.J.; Puppo, M.; Flinois, A.; Spadaro, D.; Citi, S.; Emionite, L.; et al. LncRNA EPR controls epithelial proliferation by coordinating Cdkn1a transcription and mRNA decay response to TGF-β. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, M.; Huang, J.; Li, G.W.; Jiang, B.; Cheng, H.; Liu, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Bao, L.; et al. Axon-enriched lincRNA ALAE is required for axon elongation via regulation of local mRNA translation. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remick, B.C.; Gaidt, M.M.; Vance, R.E. Effector-Triggered Immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 41, 453–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, M.H.; Lee, A.; Santin, E. Microbiome and pathogen interaction with the immune system. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 1906–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onomoto, K.; Onoguchi, K.; Yoneyama, M. Regulation of RIG-I-like receptor-mediated signaling: Interaction between host and viral factors. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonthornvacharin, S.; Rodriguez-Frandsen, A.; Zhou, Y.; Galvez, F.; Huffmaster, N.J.; Tripathi, S.; Balasubramaniam, V.R.; Inoue, A.; de Castro, E.; Moulton, H.; et al. Systems-based analysis of RIG-I-dependent signalling identifies KHSRP as an inhibitor of RIG-I receptor activation. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Yi, P.; Si, Y.; Tan, P.; He, J.; Yu, S.; Ren, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. KSRP specifies monocytic and granulocytic differentiation through regulating miR-129 biogenesis and RUNX1 expression. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Käfer, R.; Schmidtke, L.; Schrick, K.; Montermann, E.; Bros, M.; Kleinert, H.; Pautz, A. The RNA-Binding Protein KSRP Modulates Cytokine Expression of CD4(+) T Cells. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 4726532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtke, L.; Meineck, M.; Saurin, S.; Otten, S.; Gather, F.; Schrick, K.; Käfer, R.; Roth, W.; Kleinert, H.; Weinmann-Menke, J.; et al. Knockout of the KH-Type Splicing Regulatory Protein Drives Glomerulonephritis in MRL-Fas(lpr) Mice. Cells 2021, 10, 3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Käfer, R.; Schrick, K.; Schmidtke, L.; Montermann, E.; Hobernik, D.; Bros, M.; Chen, C.Y.; Kleinert, H.; Pautz, A. Inactivation of the KSRP gene modifies collagen antibody induced arthritis. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 87, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, N.; Zhang, J.; Rima, X.Y.; Nguyen, L.T.H.; Germain, R.N.; Lämmermann, T.; Reátegui, E. Analyzing Inter-Leukocyte Communication and Migration In Vitro: Neutrophils Play an Essential Role in Monocyte Activation During Swarming. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 671546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarczak, D.; Nierhaus, A. Cytokine Storm-Definition, Causes, and Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doganyigit, Z.; Eroglu, E.; Akyuz, E. Inflammatory mediators of cytokines and chemokines in sepsis: From bench to bedside. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2022, 41, 9603271221078871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnack, K.; Balasubramanian, S.; Gantier, M.P.; Kunetsky, V.; Kracht, M.; Schmitz, M.L.; Sträßer, K. Dynamic mRNP Remodeling in Response to Internal and External Stimuli. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolduan, V.; Palzer, K.A.; Hieber, C.; Schunke, J.; Fichter, M.; Schneider, P.; Grabbe, S.; Pautz, A.; Bros, M. The mRNA-Binding Protein KSRP Limits the Inflammatory Response of Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolduan, V.; Palzer, K.A.; Ries, F.; Busch, N.; Pautz, A.; Bros, M. KSRP Deficiency Attenuates the Course of Pulmonary Aspergillosis and Is Associated with the Elevated Pathogen-Killing Activity of Innate Myeloid Immune Cells. Cells 2024, 13, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.S.J.; Chamberlain, T.C.; Lallous, N.; Mui, A.L. The regulation of miR-155 strand selection by CELF2, FUBP1 and KSRP proteins. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.J.; Zheng, X.; Lin, C.C.; Tsao, J.; Zhu, X.; Cody, J.J.; Coleman, J.M.; Gherzi, R.; Luo, M.; Townes, T.M.; et al. Posttranscriptional control of type I interferon genes by KSRP in the innate immune response against viral infection. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 31, 3196–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, V.H.; Mishra, A.; Bordoloi, S.; Varma, A.; Joshi, N.C. Exploring the intersection of Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms, infections, immune response and antifungal resistance. Mycoses 2023, 66, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Baba, F.; Gao, Y.; Soubani, A.O. Pulmonary Aspergillosis: What the Generalist Needs to Know. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionakis, M.S.; Drummond, R.A.; Hohl, T.M. Immune responses to human fungal pathogens and therapeutic prospects. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, K.; Torosantucci, A.; Brakhage, A.A.; Heesemann, J.; Ebel, F. Phagocytosis of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by murine macrophages involves recognition by the dectin-1 beta-glucan receptor and Toll-like receptor 2. Cell Microbiol. 2007, 9, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschner, D.; Cholaszczyńska, A.; Ries, F.; Beckert, H.; Theobald, M.; Grabbe, S.; Radsak, M.; Bros, M. CD11b Regulates Fungal Outgrowth but Not Neutrophil Recruitment in a Mouse Model of Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haist, M.; Ries, F.; Gunzer, M.; Bednarczyk, M.; Siegel, E.; Kuske, M.; Grabbe, S.; Radsak, M.; Bros, M.; Teschner, D. Neutrophil-Specific Knockdown of β2 Integrins Impairs Antifungal Effector Functions and Aggravates the Course of Invasive Pulmonal Aspergillosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 823121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, K.V.; Sepuru, K.M.; Lowry, E.; Penaranda, B.; Frevert, C.W.; Garofalo, R.P.; Rajarathnam, K. Neutrophil recruitment by chemokines Cxcl1/KC and Cxcl2/MIP2: Role of Cxcr2 activation and glycosaminoglycan interactions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2021, 109, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.Y.; Hsieh, S.C.; Liu, C.W.; Lu, C.S.; Wu, C.H.; Liao, H.T.; Chen, M.H.; Li, K.J.; Shen, C.Y.; Kuo, Y.M.; et al. Cross-Talk among Polymorphonuclear Neutrophils, Immune, and Non-Immune Cells via Released Cytokines, Granule Proteins, Microvesicles, and Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation: A Novel Concept of Biology and Pathobiology for Neutrophils. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Kuwano, Y.; Kim, H.H.; Gorospe, M. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by RNA-binding proteins during oxidative stress: Implications for cellular senescence. Biol. Chem. 2008, 389, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, F.; Sedlyarov, V.; Tasciyan, S.; Ivin, M.; Kratochvill, F.; Gratz, N.; Kenner, L.; Villunger, A.; Sixt, M.; Kovarik, P. The RNA-binding protein tristetraprolin schedules apoptosis of pathogen-engaged neutrophils during bacterial infection. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 2051–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, I.; Nowag, S.; Koch, K.; Hubrich, T.; Bollmann, F.; Henke, J.; Schmitz, K.; Kleinert, H.; Pautz, A. Post-transcriptional regulation of the human inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression by the cytosolic poly(A)-binding protein (PABP). Nitric Oxide 2013, 33, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakstaite, A.; Maziukiene, A.; Silkuniene, G.; Kmieliute, K.; Gulbinas, A.; Dambrauskas, Z. HuR mediated post-transcriptional regulation as a new potential adjuvant therapeutic target in chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 13004–13019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, L.; Shen, J.; Xie, Y.; Xiang, M. Macrophage heme oxygenase-1 modulates peroxynitrite-mediated vascular injury and exacerbates abdominal aortic aneurysm development. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2025, 328, C1808–C1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaizu, T.; Ikeda, A.; Nakao, A.; Tsung, A.; Toyokawa, H.; Ueki, S.; Geller, D.A.; Murase, N. Protection of transplant-induced hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury with carbon monoxide via MEK/ERK1/2 pathway downregulation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 294, G236–G244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, B.R.; Galo, J.; Chitturi, K.R.; Chaturvedi, A.; Hashim, H.D.; Case, B.C. Coronary microvascular dysfunction endotypes: IMR tips and tricks. Cardiovasc. Revasc Med. 2025, 71, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartório, C.L.; Pinto, V.D.; Cutini, G.J.; Vassallo, D.V.; Stefanon, I. Effects of inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibition on the rat tail vascular bed reactivity three days after myocardium infarction. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2005, 45, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palzer, K.A.; Bolduan, V.; Lakus, J.; Tubbe, I.; Montermann, E.; Clausen, B.E.; Bros, M.; Pautz, A. The RNA-binding protein KSRP reduces asthma-like characteristics in a murine model. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 74, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Nagahama, Y.; Singh, S.K.; Kozakai, Y.; Nabeshima, H.; Fukushima, K.; Tanaka, H.; Motooka, D.; Fukui, E.; Vivier, E.; et al. Deletion of the mRNA endonuclease Regnase-1 promotes NK cell anti-tumor activity via OCT2-dependent transcription of Ifng. Immunity 2024, 57, 1360–1377.e1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, K.; Tanaka, H.; Yasuda, K.; Adachi, T.; Fukuoka, A.; Akasaki, S.; Koida, A.; Kuroda, E.; Akira, S.; Yoshimoto, T. Regnase-1 degradation is crucial for IL-33- and IL-25-mediated ILC2 activation. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e131480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Hou, W.; Yu, J.; He, T.S.; Xu, L.G. The RNA-binding protein ZFP36 strengthens innate antiviral signaling by targeting RIG-I for K63-linked ubiquitination. J. Cell Physiol. 2023, 238, 2348–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| miRNA | Mechanism | 3′-UTR Binding Region/Gene Context | Biological Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-206 | Direct binding to multiple conserved sites | ≥2 functional sites at ~nt 780–810 and ~1020–1050 | Skeletal muscle differentiation; Duchenne model | [28] |

| miR-27b-3p | Direct/TGF-β-induced silencing | Binds KHSRP 3′UTR in NMuMg and MCF10A cells | TGF-β-induced EMT in mammary epithelial cells | [30] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bolduan, V.; Pautz, A.; Bros, M. The RNA-Binding Protein KSRP Is a Negative Regulator of Innate Immunity. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010030

Bolduan V, Pautz A, Bros M. The RNA-Binding Protein KSRP Is a Negative Regulator of Innate Immunity. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleBolduan, Vanessa, Andrea Pautz, and Matthias Bros. 2026. "The RNA-Binding Protein KSRP Is a Negative Regulator of Innate Immunity" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010030

APA StyleBolduan, V., Pautz, A., & Bros, M. (2026). The RNA-Binding Protein KSRP Is a Negative Regulator of Innate Immunity. Biomolecules, 16(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010030