Biofunctionalization of Stem Cell Scaffold for Osteogenesis and Bone Regeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Bone Regeneration

2.1. The Physiological Process of Bone Regeneration

2.2. Microenvironmental Characteristics of Bone Regeneration

2.3. Pathological Microenvironment Inhibition of Regeneration

3. Stem Cell

3.1. Classification and Characteristics of Stem Cells

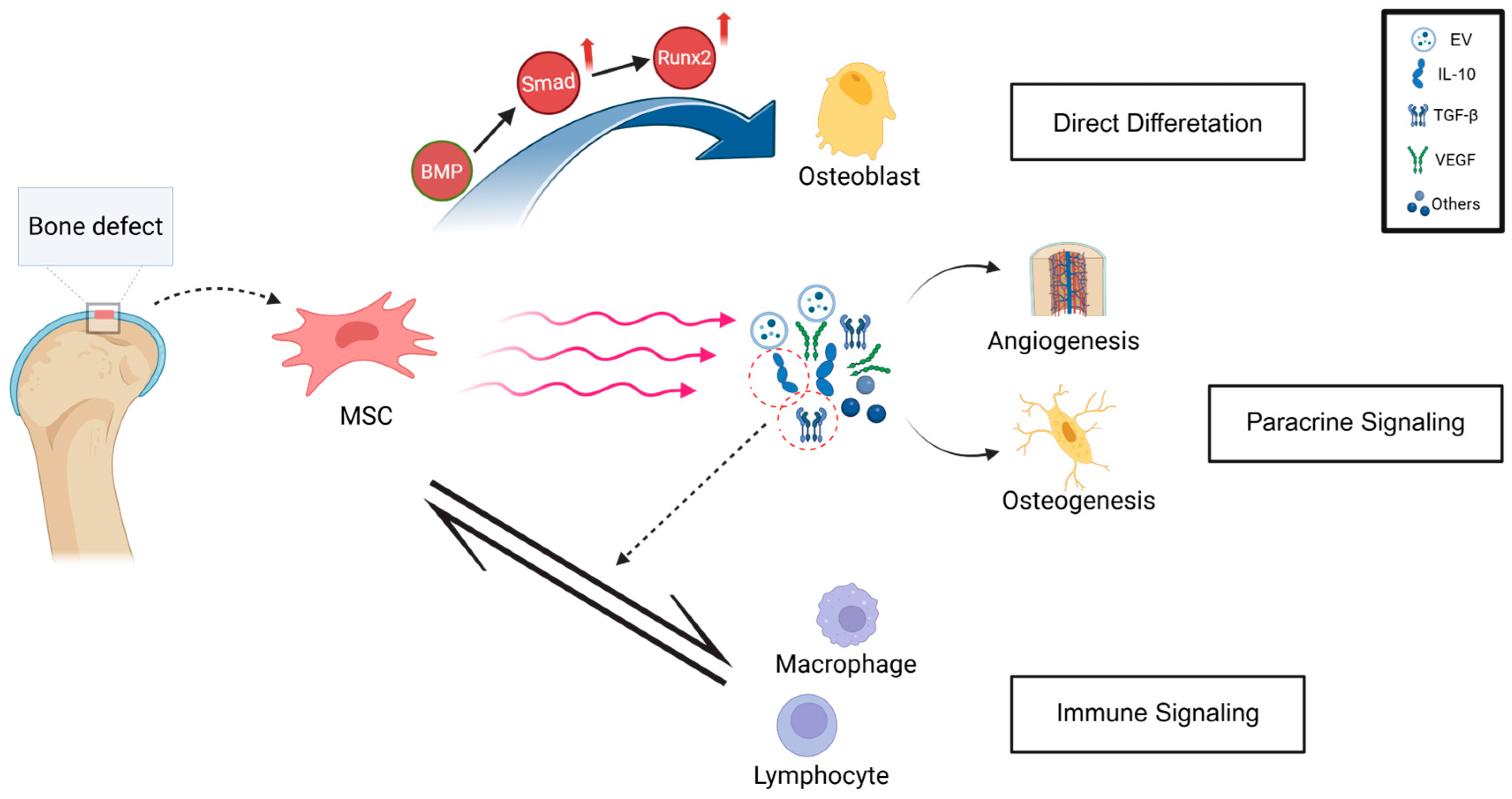

3.2. Mechanisms of Stem Cell-Promoted Osteogenesis

3.3. Limitations

4. Stem Cell Scaffold for Osteogenesis and Bone Regeneration

4.1. Properties of Scaffold Materials

4.1.1. Biochemical Properties

4.1.2. Physical Properties

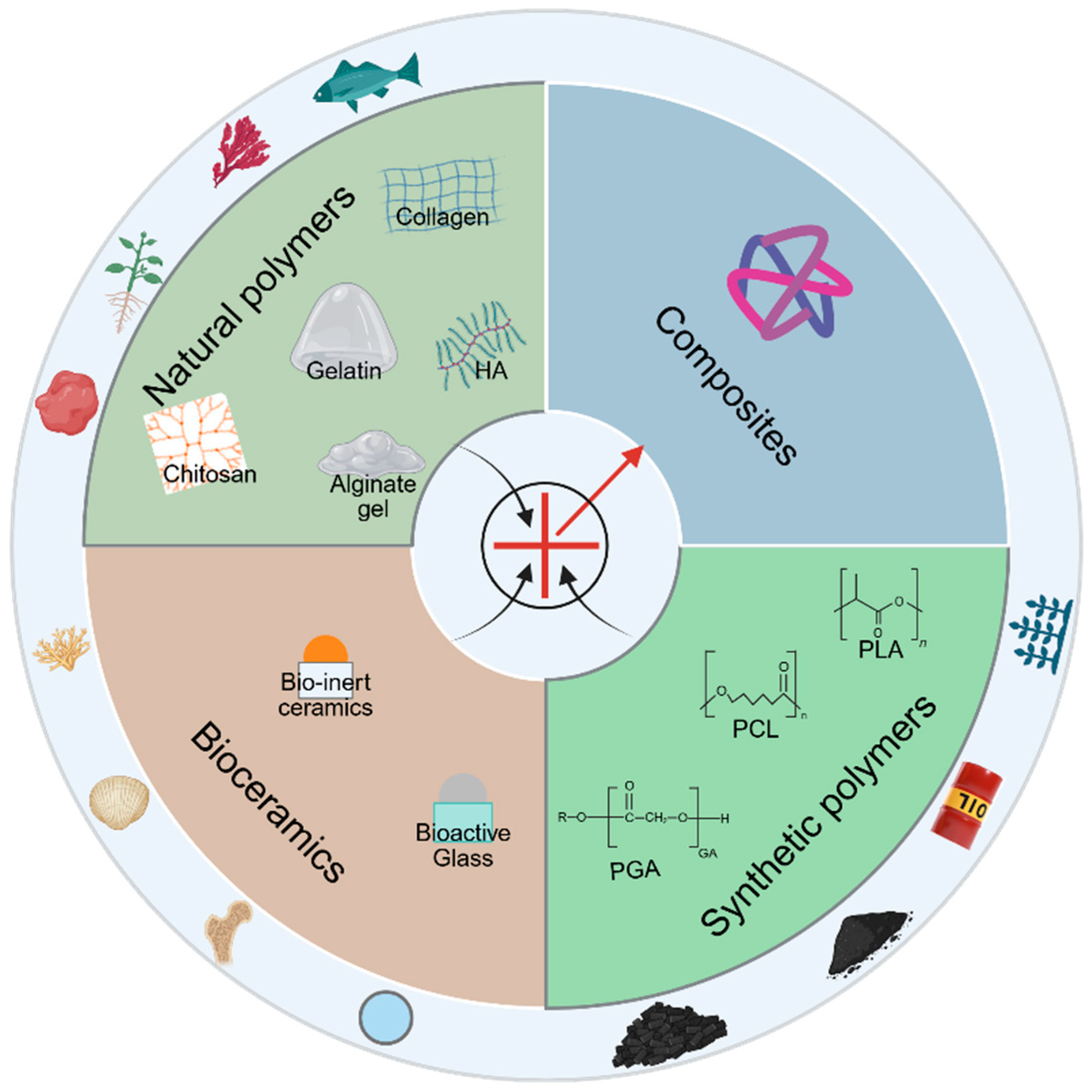

4.2. Classification of Scaffold Materials

4.2.1. Natural Polymers

4.2.2. Synthetic Polymers

4.2.3. Bioceramics

4.2.4. Composite Materials

4.3. Functionalization Strategies of Stem Cell Scaffolds

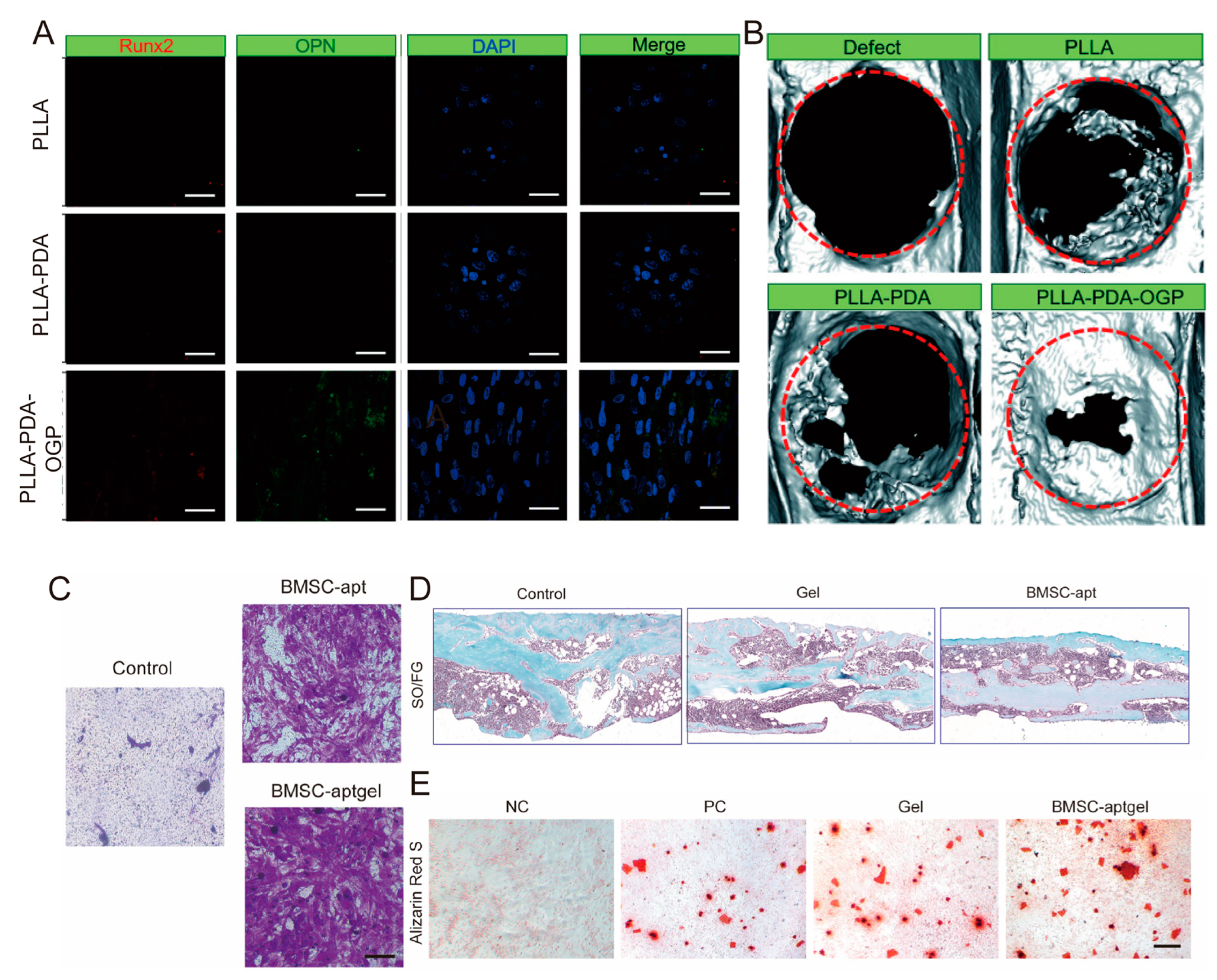

4.3.1. Scaffold Surface Functionalization Strategies

4.3.2. Growth Factor Loading Functionalization Strategy

4.3.3. Bioactive Ion Doping Functionalization Strategy

4.3.4. Extracellular Vesicle (EV) Functionalization Strategy

4.3.5. Microenvironment Regulation-Based Functionalization Strategy

5. Prospects of Biofunctionalization of Stem Cell Scaffold Based on Bibliometric Study and Clinical Trials

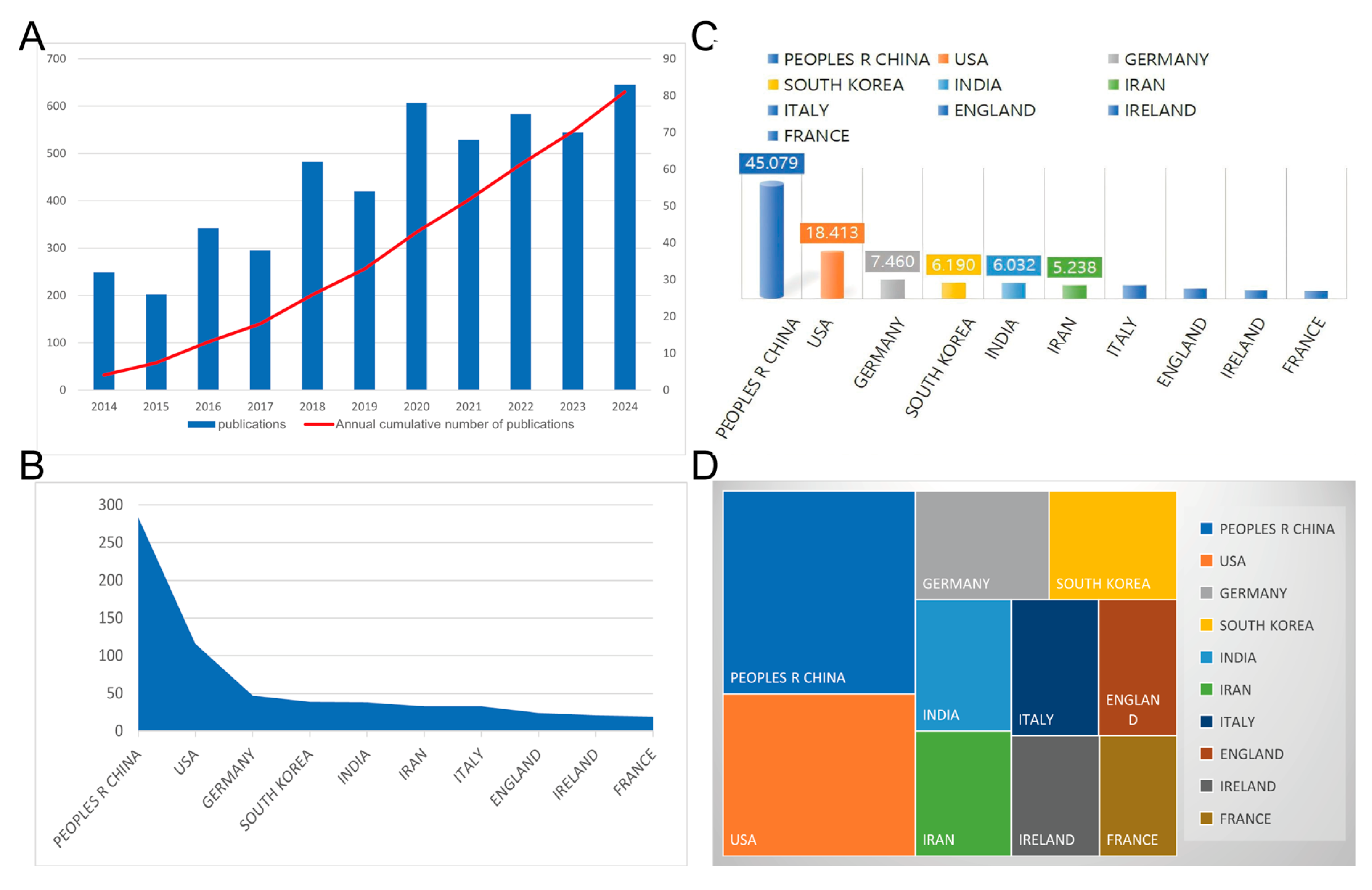

5.1. Global Literature Trend

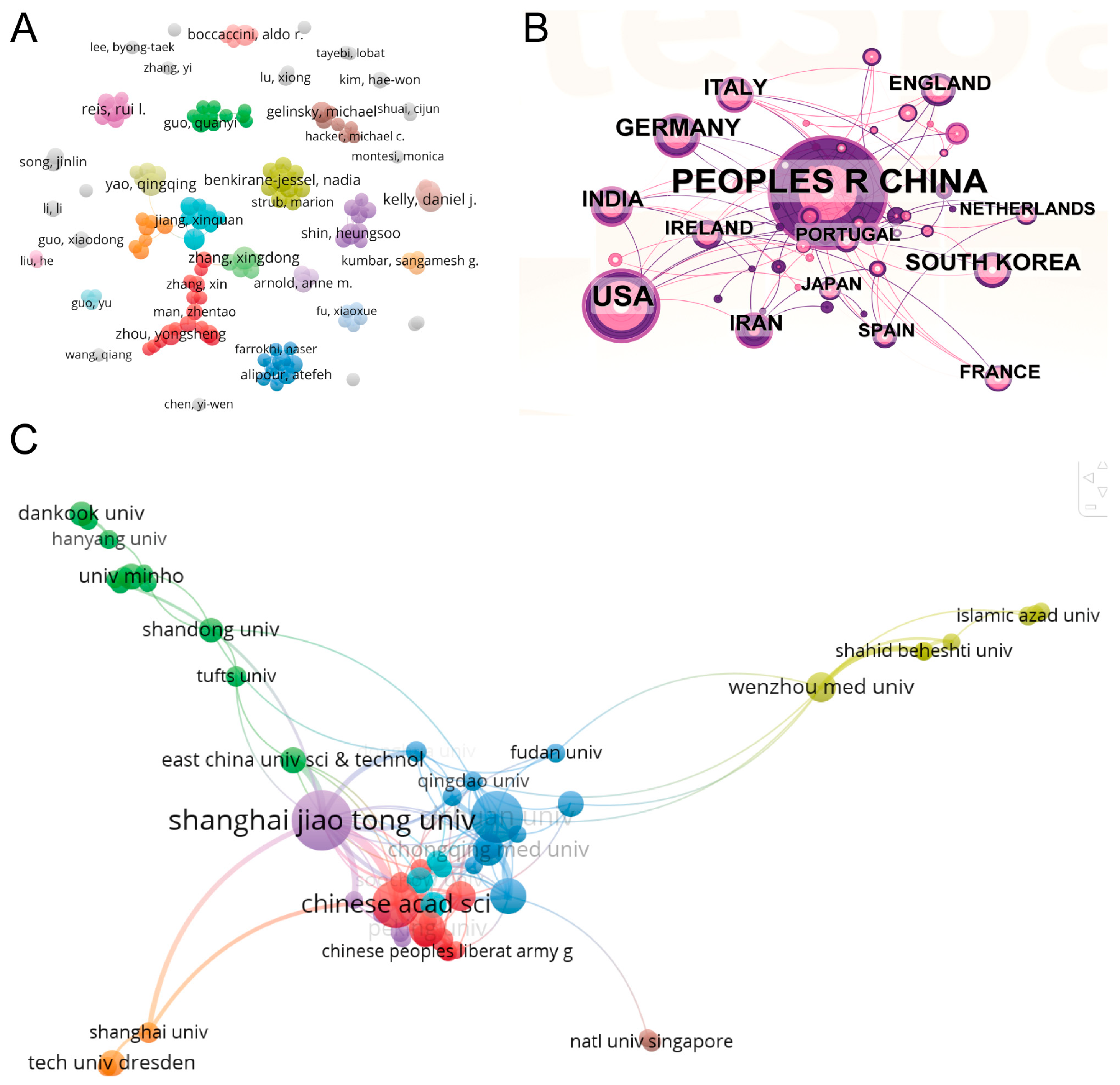

5.2. Bibliometric Analysis of Cooperation Among Authors, Countries, and Institutions

5.3. Clinical Trials of Biofunctionalized Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bharadwaz, A.; Jayasuriya, A.C. Recent trends in the application of widely used natural and synthetic polymer nanocomposites in bone tissue regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 110, 110698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florencio-Silva, R.; Sasso, G.R.; Sasso-Cerri, E.; Simoes, M.J.; Cerri, P.S. Biology of Bone Tissue: Structure, Function, and Factors That Influence Bone Cells. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 421746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Discher, D.E.; Peault, B.M.; Phinney, D.G.; Hare, J.M.; Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: Cell biology to clinical progress. NPJ Regen. Med. 2019, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Shui-Ling, A.; Bolander, J.; Rustom, L.E.; Johnson, A.W.; Luyten, F.P.; Picart, C. Bone regeneration strategies: Engineered scaffolds, bioactive molecules and stem cells current stage and future perspectives. Biomaterials 2018, 180, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, E.A.; Mirsky, N.A.; Silva, B.L.G.; Shinde, A.R.; Arakelians, A.R.L.; Nayak, V.V.; Marcantonio, R.A.C.; Gupta, N.; Witek, L.; Coelho, P.G. Functional Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Regeneration: A Comprehensive Review of Materials, Methods, and Future Directions. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Liang, B.; Shi, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.; Shao, T.; Xing, K.; Yan, M.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Immunomodulatory biomaterials for osteoarthritis: Targeting inflammation and enhancing cartilage regeneration. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 34, 102100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Saiz, E.; Rahaman, M.N.; Tomsia, A.P. Bioactive glass scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: State of the art and future perspectives. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2011, 31, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haumer, A.; Bourgine, P.E.; Occhetta, P.; Born, G.; Tasso, R.; Martin, I. Delivery of cellular factors to regulate bone healing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 129, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safari, B.; Davaran, S.; Aghanejad, A. Osteogenic potential of the growth factors and bioactive molecules in bone regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 175, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhai, D.; Qin, C.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhuang, H.; Shi, Z.; Wang, L.; Wu, C. Polyhedron-Like Biomaterials for Innervated and Vascularized Bone Regeneration. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2302716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Villicana, C.; Barati, D.; Freeman, P.; Luo, Y.; Yang, F. Stem Cell Membrane-Coated Microribbon Scaffolds Induce Regenerative Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses in a Critical-Size Cranial Bone Defect Model. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2208781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaquinta, M.R.; Mazzoni, E.; Bononi, I.; Rotondo, J.C.; Mazziotta, C.; Montesi, M.; Sprio, S.; Tampieri, A.; Tognon, M.; Martini, F. Adult Stem Cells for Bone Regeneration and Repair. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, H.; Duda, G.N.; Peters, A.; Tsitsilonis, S.; Johnson, K.A.; Schmidt-Bleek, K. The haematoma and its role in bone healing. J. Exp. Orthop. 2017, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, J.R.; Mabrouk, A.; Garla, V.V. Fracture Healing Overview. In StatPearls Internet; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, S.; Yallowitz, A.R.; McCormick, J.; Lalani, S.; Zhang, T.; Xu, R.; Li, N.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.S.; Eiseman, M.; et al. Discovery of a periosteal stem cell mediating intramembranous bone formation. Nature 2018, 562, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, D.; Xu, S.; Chen, X.; Huang, J.; Feng, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Z. A novel lineage of osteoprogenitor cells with dual epithelial and mesenchymal properties govern maxillofacial bone homeostasis and regeneration after MSFL. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Gao, C.; Gao, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, M.; et al. Osteocytes regulate senescence of bone and bone marrow. Elife 2022, 11, 36305580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Calle, J.; Bellido, T. The osteocyte as a signaling cell. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 379–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvites, R.; Branquinho, M.; Sousa, A.C.; Lopes, B.; Sousa, P.; Mauricio, A.C. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells and Their Paracrine Activity-Immunomodulation Mechanisms and How to Influence the Therapeutic Potential. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wei, X.; He, X.; Xiao, S.; Shi, Q.; Chen, P.; Lee, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, H.; Fan, Y. Osteoinductive Dental Pulp Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicle-Loaded Multifunctional Hydrogel for Bone Regeneration. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 8777–8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Meyers, C.A.; Chang, L.; Lee, S.; Li, Z.; Tomlinson, R.; Hoke, A.; Clemens, T.L.; James, A.W. Fracture repair requires TrkA signaling by skeletal sensory nerves. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 5137–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, D.; Xu, L.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Pan, Y.; Jiang, M.; Wei, Y.; Wang, L.; Liao, Y.; et al. Harnessing matrix stiffness to engineer a bone marrow niche for hematopoietic stem cell rejuvenation. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 378–395 e378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, K.; Tang, H.; Hu, S.; Xin, L.; Jing, X.; He, Q.; Wang, S.; Song, J.; Mei, L.; et al. A Logic-Based Diagnostic and Therapeutic Hydrogel with Multistimuli Responsiveness to Orchestrate Diabetic Bone Regeneration. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2108430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhou, F.; Wu, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Tang, H.; Bai, L.; Geng, Z.; et al. Engineering Large-Scale Self-Mineralizing Bone Organoids with Bone Matrix-Inspired Hydroxyapatite Hybrid Bioinks. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2309875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, S.; Chu, X.; Reiter, J.; Gao, H.; McGuire, P.; Yu, X.; Xuei, X.; Liu, Y.; Wan, J.; et al. Osteogenic Differentiation Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Using Single Cell Multiomic Analysis. Genes 2023, 14, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, O.H.; Panicker, L.M.; Lu, Q.; Chae, J.J.; Feldman, R.A.; Elisseeff, J.H. Human iPSC-derived osteoblasts and osteoclasts together promote bone regeneration in 3D biomaterials. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Ruan, M.; Bu, Q.; Zhao, C. Signaling Pathways Driving MSC Osteogenesis: Mechanisms, Regulation, and Translational Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Pan, X.; Wang, X.; Xie, H.; Ye, Q. Interactions between induced pluripotent stem cells and stem cell niche augment osteogenesis and bone regeneration. Smart Mater. Med. 2021, 2, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, H.M.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, Y.J. Critical molecular switches involved in BMP-2-induced osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal cells. Gene 2006, 366, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.F.; Cheng, S.L. Signal transductions induced by bone morphogenetic protein-2 and transforming growth factor-beta in normal human osteoblastic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 15514–15522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, M.; Cao, X. BMP signaling in skeletal development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 328, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Karin, M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature 2001, 410, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.J.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.I.; Kim, K. Bone Remodeling: Histone Modifications as Fate Determinants of Bone Cell Differentiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westendorf, J.J.; Kahler, R.A.; Schroeder, T.M. Wnt signaling in osteoblasts and bone diseases. Gene 2004, 341, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, C.P.; Bareja, A.; Gomez, J.A.; Dzau, V.J. Emerging Concepts in Paracrine Mechanisms in Regenerative Cardiovascular Medicine and Biology. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wang, H.; Qiu, G.; Su, X.; Wu, Z. Synergistic Effects of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor on Bone Morphogenetic Proteins Induced Bone Formation In Vivo: Influencing Factors and Future Research Directions. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 2869572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, B.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Yuan, F.; Fan, C. Macrophage-Derived TGF-beta and VEGF Promote the Progression of Trauma-Induced Heterotopic Ossification. Inflammation 2023, 46, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Lv, J.; Guo, S.; Lv, M. Cellular microenvironment: A key for tuning mesenchymal stem cell senescence. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1323678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahy, N.; de Vries-van Melle, M.L.; Lehmann, J.; Wei, W.; Grotenhuis, N.; Farrell, E.; van der Kraan, P.M.; Murphy, J.M.; Bastiaansen-Jenniskens, Y.M.; van Osch, G.J. Human osteoarthritic synovium impacts chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via macrophage polarisation state. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014, 22, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, S.K.; Gao, Q.; Pius, A.; Morita, M.; Ergul, Y.; Murayama, M.; Shinohara, I.; Cekuc, M.S.; Ma, C.; Susuki, Y.; et al. The Advantages and Shortcomings of Stem Cell Therapy for Enhanced Bone Healing. Tissue Eng. Part. C Methods 2024, 30, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezwan, K.; Chen, Q.Z.; Blaker, J.J.; Boccaccini, A.R. Biodegradable and bioactive porous polymer/inorganic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3413–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainer, A.; Giannitelli, S.M.; Abbruzzese, F.; Traversa, E.; Licoccia, S.; Trombetta, M. Fabrication of bioactive glass-ceramic foams mimicking human bone portions for regenerative medicine. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Tare, R.S.; Yang, L.Y.; Williams, D.F.; Ou, K.L.; Oreffo, R.O. Biofabrication of bone tissue: Approaches, challenges and translation for bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2016, 83, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimina, A.; Senatov, F.; Choudhary, R.; Kolesnikov, E.; Anisimova, N.; Kiselevskiy, M.; Orlova, P.; Strukova, N.; Generalova, M.; Manskikh, V.; et al. Biocompatibility and Physico-Chemical Properties of Highly Porous PLA/HA Scaffolds for Bone Reconstruction. Polymers 2020, 12, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Guehennec, L.; Van Hede, D.; Plougonven, E.; Nolens, G.; Verlee, B.; De Pauw, M.C.; Lambert, F. In vitro and in vivo biocompatibility of calcium-phosphate scaffolds three-dimensional printed by stereolithography for bone regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2020, 108, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klavert, J.; van der Eerden, B.C.J. Fibronectin in Fracture Healing: Biological Mechanisms and Regenerative Avenues. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 663357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keselowsky, B.G.; Collard, D.M.; Garcia, A.J. Integrin binding specificity regulates biomaterial surface chemistry effects on cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5953–5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, X.; He, X.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xie, R.; Liu, Z.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, N.; Xiang, Q.; Cui, Y. Targeting integrin pathways: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keselowsky, B.G.; Collard, D.M.; Garcia, A.J. Surface chemistry modulates fibronectin conformation and directs integrin binding and specificity to control cell adhesion. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2003, 66, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valimaki, V.V.; Aro, H.T. Molecular basis for action of bioactive glasses as bone graft substitute. Scand. J. Surg. 2006, 95, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Felfel, R.M.; Abou Neel, E.A.; Grant, D.M.; Ahmed, I.; Hossain, K.M.Z. Bioactive calcium phosphate-based glasses and ceramics and their biomedical applications: A review. J. Tissue Eng. 2017, 8, 2041731417719170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverria Molina, M.I.; Malollari, K.G.; Komvopoulos, K. Design Challenges in Polymeric Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 617141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceonzo, K.; Gaynor, A.; Shaffer, L.; Kojima, K.; Vacanti, C.A.; Stahl, G.L. Polyglycolic acid-induced inflammation: Role of hydrolysis and resulting complement activation. Tissue Eng. 2006, 12, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Diao, J.; Kuang, Y.; Zhao, N. Beta-TCP scaffolds with rationally designed macro-micro hierarchical structure improved angio/osteo-genesis capability for bone regeneration. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2023, 34, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zheng, L.; Wang, M. Biofunctionalized Nanofibrous Bilayer Scaffolds for Enhancing Cell Adhesion, Proliferation and Osteogenesis. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 5276–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Baker, B.A.; Mou, X.; Ren, N.; Qiu, J.; Boughton, R.I.; Liu, H. Biopolymer/Calcium phosphate scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.S.B.; Ponnamma, D.; Choudhary, R.; Sadasivuni, K.K. A Comparative Review of Natural and Synthetic Biopolymer Composite Scaffolds. Polymers 2021, 13, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, V.S.; Bandyopadhyay-Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, S.B. An overview of translational research in bone graft biomaterials. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2023, 34, 497–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.; Vega, M.E.; Pastino, A.K.; Singh, S.; Guvendiren, M.; Kohn, J.; Murthy, N.S.; Schwarzbauer, J.E. Development of hybrid scaffolds with natural extracellular matrix deposited within synthetic polymeric fibers. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2017, 105, 2162–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.B.; Haydel, S.E. Evaluation of the medicinal use of clay minerals as antibacterial agents. Int. Geol. Rev. 2010, 52, 745–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, Y.S.; Park, J.H.; Kim, T.H. Recent Advances in Stem Cell Differentiation Control Using Drug Delivery Systems Based on Porous Functional Materials. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Han, S.H.; Kook, Y.M.; Lee, K.M.; Jin, Y.Z.; Koh, W.G.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, K. A novel 3D indirect co-culture system based on a collagen hydrogel scaffold for enhancing the osteogenesis of stem cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 9481–9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, K.; Chen, X.; Read, H.M.; Zeng, L.; Hang, F. Three dimensional printed bioglass/gelatin/alginate composite scaffolds with promoted mechanical strength, biomineralization, cell responses and osteogenesis. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2020, 31, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, K.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, N. Recent advancements in natural polymers-based self-healing nano-materials for wound dressing. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2024, 112, e35435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Subbiah, R.; Kwon, M.J.; Kim, W.J.; Kim, S.H.; Park, K.; Lee, K. The three dimensional cues-integrated-biomaterial potentiates differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 202, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levengood, S.L.; Zhang, M. Chitosan-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 3161–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiew, V.V.; Simat, S.F.B.; Teoh, P.L. The Advancement of Biomaterials in Regulating Stem Cell Fate. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2018, 14, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.N.; Veeresh, V.; Mallick, S.P.; Jain, Y.; Sinha, S.; Rastogi, A.; Srivastava, P. Design and evaluation of chitosan/chondroitin sulfate/nano-bioglass based composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 133, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.Y.; Seo, S.J.; Moon, H.S.; Yoo, M.K.; Park, I.Y.; Kim, B.C.; Cho, C.S. Chitosan and its derivatives for tissue engineering applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2008, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, J.; Kim, S.K. Chitosan composites for bone tissue engineering--an overview. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2252–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, S.; Oliveira, J.M.; Reis, R.L. Natural-based nanocomposites for bone tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: A review. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 1143–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavanya, K.; Balagangadharan, K.; Chandran, S.V.; Selvamurugan, N. Chitosan-coated and thymol-loaded polymeric semi-interpenetrating hydrogels: An effective platform for bioactive molecule delivery and bone regeneration in vivo. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 146, 213305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Gonzalez, A.C.; Tellez-Jurado, L.; Rodriguez-Lorenzo, L.M. Alginate hydrogels for bone tissue engineering, from injectables to bioprinting: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Kang, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, C.; Shen, S.; Qu, C.; Gong, S.; Liu, P.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; et al. Alginate microspheres-collagen hydrogel, as a novel 3D culture system, enhanced skin wound healing of hUCMSCs in rats model. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 219, 112799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lele, M.; Kapur, S.; Hargett, S.; Sureshbabu, N.M.; Gaharwar, A.K. Global trends in clinical trials involving engineered biomaterials. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eabq0997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademhosseini, A.; Eng, G.; Yeh, J.; Fukuda, J.; Blumling, J., 3rd; Langer, R.; Burdick, J.A. Micromolding of photocrosslinkable hyaluronic acid for cell encapsulation and entrapment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 79, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.I.; Abaci, H.E.; Krupsi, Y.; Weng, L.C.; Burdick, J.A.; Gerecht, S. Hyaluronic acid hydrogel stiffness and oxygen tension affect cancer cell fate and endothelial sprouting. Biomater. Sci. 2014, 2, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakasam, M.; Locs, J.; Salma-Ancane, K.; Loca, D.; Largeteau, A.; Berzina-Cimdina, L. Fabrication, Properties and Applications of Dense Hydroxyapatite: A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2015, 6, 1099–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Abdullah, A.; Wendt, M.K.; Calve, S. Hyaluronic acid, CD44 and RHAMM regulate myoblast behavior during embryogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2019, 78–79, 236–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, M.; Ariyoshi, W.; Iwanaga, K.; Okinaga, T.; Habu, M.; Yoshioka, I.; Tominaga, K.; Nishihara, T. Mechanism involved in enhancement of osteoblast differentiation by hyaluronic acid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 405, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashirina, A.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Biopolymers as bone substitutes: A review. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 3961–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, X. Synthetic Polymers for Organ 3D Printing. Polymers 2020, 12, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunatillake, P.A.; Adhikari, R. Biodegradable synthetic polymers for tissue engineering. Eur. Cell Mater. 2003, 5, 14562275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Harussani, M.M.; Hakimi, M.; Haziq, M.Z.M.; Atikah, M.S.N.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Ishak, M.R.; Razman, M.R.; Nurazzi, N.M.; et al. Polylactic Acid (PLA) Biocomposite: Processing, Additive Manufacturing and Advanced Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugavel, S.; Reddy, V.J.; Ramakrishna, S.; Lakshmi, B.S.; Dev, V.G. Precipitation of hydroxyapatite on electrospun polycaprolactone/aloe vera/silk fibroin nanofibrous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomater. Appl. 2014, 29, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani Ghomi, E.; Khosravi, F.; Saedi Ardahaei, A.; Dai, Y.; Neisiany, R.E.; Foroughi, F.; Wu, M.; Das, O.; Ramakrishna, S. The Life Cycle Assessment for Polylactic Acid (PLA) to Make It a Low-Carbon Material. Polymers 2021, 13, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, R.; Xu, Y.; Xia, D.; Zhu, Y.; Yoon, J.; Gu, R.; Liu, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, X.; et al. Fabrication and Application of a 3D-Printed Poly-epsilon-Caprolactone Cage Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 2087475. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, R.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, R.; Mahajan, A.; Nandana, D.; Katti, D.S.; Mehrotra, D. Polycaprolactone as biomaterial for bone scaffolds: Review of literature. J. Oral. Biol. Craniofac Res. 2020, 10, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labet, M.; Thielemans, W. Synthesis of polycaprolactone: A review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 3484–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Corrigan, N.; Wong, E.H.H.; Boyer, C. Bioactive Synthetic Polymers. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2105063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Blackwood, K.A.; Doustgani, A.; Poh, P.P.; Steck, R.; Stevens, M.M.; Woodruff, M.A. Melt-electrospun polycaprolactone strontium-substituted bioactive glass scaffolds for bone regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2014, 102, 3140–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Torrecilla, J.A.; Echanove-Gonzalez de Anleo, M.; Martinez-Oharriz, C.; Ripalda-Cemborain, P.; Lopez-Martinez, T.; Abizanda, G.; Valdes-Fernandez, J.; Prandota, J.; Muinos-Lopez, E.; Garbayo, E.; et al. 3D-printed polycaprolactone scaffolds functionalized with poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid microparticles enhance bone regeneration through tunable drug release. Acta Biomater. 2025, 198, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regi, M.V.; Esbrit, P.; Salinas, A.J. Degradative Effects of the Biological Environment on Ceramic Biomaterials. In Biomaterials Science; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 955–971. [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj, N.; Piili, H.; Ganvir, A.; Gopaluni, A.; Nayak, C.; Moritz, N.; Salminen, A. Bioinert ceramics scaffolds for bone tissue engineering by laser-based powder bed fusion: A preliminary review. Proc. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 1296, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohner, M.; Santoni, B.L.G.; Dobelin, N. beta-tricalcium phosphate for bone substitution: Synthesis and properties. Acta Biomater. 2020, 113, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasser, R.A.; AlSubaie, A.; AlShehri, F. Effectiveness of beta-tricalcium phosphate in comparison with other materials in treating periodontal infra-bony defects around natural teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral. Health 2021, 21, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, G.; Clarke, J.; Picard, F.; Riches, P.; Jia, L.; Han, F.; Li, B.; Shu, W. 3D bioactive composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2018, 3, 278–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, X.; He, Y.; Lu, J.; Shen, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, B. Co-culturing mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and periosteum enhances osteogenesis and neovascularization of tissue-engineered bone. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2012, 6, 822–832. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Lee, B.T. A combination of biphasic calcium phosphate scaffold with hyaluronic acid-gelatin hydrogel as a new tool for bone regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part. A 2014, 20, 1993–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, C.; D’Asta, F.; Brandi, M.L. Drug delivery using composite scaffolds in the context of bone tissue engineering. Clin. Cases Min. Bone Metab. 2013, 10, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Bi, Q.; Zhao, C.; Chen, J.Y.; Cai, M.H.; Chen, X.Y. Recent Advances in Biomaterials for the Treatment of Bone Defects. Organogenesis 2020, 16, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, R.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M. Surface modifications of scaffolds for bone regeneration. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 7938–7973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yu, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhao, W.; Ge, S.; Liu, H.; Li, J. Metal-phenolic network biointerface-mediated cell regulation for bone tissue regeneration. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 30, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Gao, Q.; Deng, R.; Zeng, L.; Guo, J.; Ye, B.; Yu, J.; Guo, X. Aptamer engineering exosomes loaded on biomimetic periosteum to promote angiogenesis and bone regeneration by targeting injured nerves via JNK3 MAPK pathway. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 16, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanati, M.; Amin Yavari, S. Liposome-integrated hydrogel hybrids: Promising platforms for cancer therapy and tissue regeneration. J. Control. Release 2024, 368, 703–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Z.C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.R.; Deng, R.H.; Zhang, Z.N.; Yu, J.K.; Yuan, F.Z. Function and Mechanism of RGD in Bone and Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 773636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tollabi, M.; Poursalehi, Z.; Mehrafshar, P.; Bakhtiari, R.; Hosseinpour Sarmadi, V.; Tayebi, L.; Haramshahi, S.M.A. Insight into the role of integrins and integrins-targeting biomaterials in bone regeneration. Connect. Tissue Res. 2024, 65, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, Y.J.; Gal, C.W.; Sung, A.; Utami, S.S.; Park, H.; Yun, H.S. Enhanced Osteogenesis in 2D and 3D Culture Systems Using RGD Peptide and alpha-TCP Phase Transition within Alginate-Based Hydrogel. Macromol. Biosci. 2024, 24, e2400190. [Google Scholar]

- Pigossi, S.C.; Medeiros, M.C.; Saska, S.; Cirelli, J.A.; Scarel-Caminaga, R.M. Role of Osteogenic Growth Peptide (OGP) and OGP (10–14) in Bone Regeneration: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, J.; Sun, X.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, J. Sustained delivery of osteogenic growth peptide through injectable photoinitiated composite hydrogel for osteogenesis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1228250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.L.; Wu, J.J.; Lin, C.C.; Qin, X.; Tay, F.R.; Miao, L.; Tao, B.L.; Jiao, Y. Elimination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilms on titanium implants via photothermally-triggered nitric oxide and immunotherapy for enhanced osseointegration. Mil. Med. Res. 2023, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, C.; Gu, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, L. Polydopamine-modified poly(l-lactic acid) nanofiber scaffolds immobilized with an osteogenic growth peptide for bone tissue regeneration. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 11722–11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.J.; Zhang, R.Y.; Jiang, S.; Xiao, S.; Liu, Y.; Niu, Y.; Zhao, W.X.; Wang, D.; Ma, X. Applications of cell penetrating peptide-based drug delivery system in immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1540192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, M.G.; Palermo, N.; D’Amora, U.; Oddo, S.; Guglielmino, S.P.P.; Conoci, S.; Szychlinska, M.A.; Calabrese, G. Multipotential Role of Growth Factor Mimetic Peptides for Osteochondral Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.S.; Zhu, G.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y.W.; Li, H.M.; He, Z.H.; Zou, J.T.; Qian, Y.X.; Zhu, S.; et al. Aptamer-functionalized hydrogels promote bone healing by selectively recruiting endogenous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 23, 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Kinghorn, A.B.; Wang, L.; Bhuyan, S.K.; Shiu, S.C.; Tanner, J.A. The Evolution and Application of a Novel DNA Aptamer Targeting Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 for Bone Regeneration. Molecules 2024, 29, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, J.H.; Qin, X. Polyphosphoprotein from the adhesive pads of Mytilus edulis. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 2887–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Yu, B.; Zhou, F.; Xue, Q. Self-healing surface hydrophobicity by consecutive release of hydrophobic molecules from mesoporous silica. Langmuir 2012, 28, 5845–5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ruan, C.; Pan, H.; Catchmark, J.M. Bioabsorbable cellulose composites prepared by an improved mineral-binding process for bone defect repair. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Tang, F.; Jin, Z. Free-standing polydopamine films generated in the presence of different metallic ions: The comparison of reaction process and film properties. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 18347–18354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wei, J.; Hu, Y.X.; Chen, X.F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Jiang, S.P.; Tao, S.W.; Wang, H.T. Metal-polydopamine frameworks and their transformation to hollow metal/N-doped carbon particles. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 5323–5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Kim, K.Y.; Wook, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, K.D.; Lee, D.Y.; Lee, H. Attenuation of the in vivo toxicity of biomaterials by polydopamine surface modification. Nanomedicine 2011, 6, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, X.; Poh, C.K.; Tan, H.C.; Soe, M.T.; Zhang, S.; Wang, W. Accelerated bone growth in vitro by the conjugation of BMP2 peptide with hydroxyapatite on titanium alloy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 116, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, B.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Zeng, D.; Li, R.; Qin, Y. Rapid Batch Surface Modification of 3D-Printed High-Strength Polymer Scaffolds for Enhanced Bone Regeneration In Vitro and In Vivo. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 43, 103588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankenson, K.D.; Gagne, K.; Shaughnessy, M. Extracellular signaling molecules to promote fracture healing and bone regeneration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 94, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Wang, M.; Yin, Z.; Jing, Y.; Bai, L.; Su, J. Microenvironment-targeted strategy steers advanced bone regeneration. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 22, 100741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.; Olsen, B.R. The roles of vascular endothelial growth factor in bone repair and regeneration. Bone 2016, 91, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaz, A.; Jayasuriya, A.C. Osteogenic differentiation cues of the bone morphogenetic protein-9 (BMP-9) and its recent advances in bone tissue regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 120, 111748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, Z.; Kushioka, J.; Kodama, J.; Kaito, T.; Yoshikawa, H.; Korkusuz, P.; Korkusuz, F. BMP and TGFbeta use and release in bone regeneration. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 1707–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gao, C.Y.; Chu, X.Y.; Zheng, C.Y.; Luan, Y.Y.; He, X.; Yang, K.; Zhang, D.L. VEGF-Loaded Heparinised Gelatine-Hydroxyapatite-Tricalcium Phosphate Scaffold Accelerates Bone Regeneration via Enhancing Osteogenesis-Angiogenesis Coupling. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 915181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, B.; Zhang, K.; Zuo, R.; Kang, Z.; Lin, J.; Kang, Z.; Luo, D.; Chai, Y.; Xu, J.; Kang, Q.; et al. 3D-bioprinted functional scaffold based on synergistic induction of i-PRF and laponite exerts efficient and personalized bone regeneration via miRNA-mediated TGF-beta/Smads signaling. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 3193–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, U.; Jaffery, H.; Salmeron-Sanchez, M.; Dalby, M.J. An ossifying landscape: Materials and growth factor strategies for osteogenic signalling and bone regeneration. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 73, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murahashi, Y.; Yano, F.; Nakamoto, H.; Maenohara, Y.; Iba, K.; Yamashita, T.; Tanaka, S.; Ishihara, K.; Okamura, Y.; Moro, T.; et al. Multi-layered PLLA-nanosheets loaded with FGF-2 induce robust bone regeneration with controlled release in critical-sized mouse femoral defects. Acta Biomater. 2019, 85, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenlarp, P.; Rajendran, A.K.; Iseki, S. Role of fibroblast growth factors in bone regeneration. Inflamm. Regen. 2017, 37, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salandova, M.; van Hengel, I.A.J.; Apachitei, I.; Zadpoor, A.A.; van der Eerden, B.C.J.; Fratila-Apachitei, L.E. Inorganic Agents for Enhanced Angiogenesis of Orthopedic Biomaterials. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, e2002254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baheiraei, N.; Eyni, H.; Bakhshi, B.; Najafloo, R.; Rabiee, N. Effects of strontium ions with potential antibacterial activity on in vivo bone regeneration. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, W.; Gao, H.; Hou, X. Magnesium lithospermate B inhibits titanium particles-induced osteoclast formation by c-fos and inhibiting NFATc1 expression. Connect. Tissue Res. 2019, 60, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Li, Z.; Zhong, X.; Cai, Z.; Ning, Z.; Hou, T.; Xiong, L.; Feng, Y.; Leung, F.; Lu, W.W.; et al. Strontium inhibits osteoclastogenesis by enhancing LRP6 and beta-catenin-mediated OPG targeted by miR-181d-5p. J. Cell Commun. Signal 2019, 13, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, M.; Kharaziha, M.; Tafti, H.A.; Eslaminejad, M.B.; Aghdam, R.M. Synergic role of zinc and gallium doping in hydroxyapatite nanoparticles to improve osteogenesis and antibacterial activity. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 134, 112684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algazlan, A.S.; Almuraikhi, N.; Muthurangan, M.; Balto, H.; Alsalleeh, F. Silver Nanoparticles Alone or in Combination with Calcium Hydroxide Modulate the Viability, Attachment, Migration, and Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutthavas, P.; Tahmasebi Birgani, Z.; Habibovic, P.; van Rijt, S. Calcium Phosphate-Coated and Strontium-Incorporated Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Can Effectively Induce Osteogenic Stem Cell Differentiation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, e2101588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.; Li, Y.; Wen, C. Ion-substituted calcium phosphate coatings by physical vapor deposition magnetron sputtering for biomedical applications: A review. Acta Biomater. 2019, 89, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardeshirylajimi, A.; Golchin, A.; Khojasteh, A.; Bandehpour, M. Increased osteogenic differentiation potential of MSCs cultured on nanofibrous structure through activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signalling by inorganic polyphosphate. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, S943–S949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Tian, Y.; Gao, Q.; Yu, Y.; Xia, X.; Feng, Z.; Dong, F.; Wu, X.; Sui, L. Hierarchical Micro-Nano Topography Promotes Cell Adhesion and Osteogenic Differentiation via Integrin alpha2-PI3K-AKT Signaling Axis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leem, Y.H.; Lee, K.S.; Kim, J.H.; Seok, H.K.; Chang, J.S.; Lee, D.H. Magnesium ions facilitate integrin alpha 2- and alpha 3-mediated proliferation and enhance alkaline phosphatase expression and activity in hBMSCs. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2016, 10, E527–E536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svitkina, T. The Actin Cytoskeleton and Actin-Based Motility. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, 018267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Fan, B.; Yu, X.; Liu, W.; Wu, J.; Shi, L.; Yang, D.; Tan, L.; Wan, P.; Hao, Y.; et al. Biofunctional magnesium coated Ti6Al4V scaffold enhances osteogenesis and angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo for orthopedic application. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, D.; Wan, G.; Gu, X.; Ma, J. Nogo-B promotes angiogenesis and improves cardiac repair after myocardial infarction via activating Notch1 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa-Goncalves, M.; Ribeiro-Machado, C.; Costa, M.; Ribeiro, C.C.; Barbosa, J.N.; Barbosa, M.A.; Santos, S.G. Magnesium incorporation in fibrinogen scaffolds promotes macrophage polarization towards M2 phenotype. Acta Biomater. 2023, 155, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarins, J.; Pilmane, M.; Sidhoma, E.; Salma, I.; Locs, J. Immunohistochemical evaluation after Sr-enriched biphasic ceramic implantation in rabbits femoral neck: Comparison of seven different bone conditions. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2018, 29, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Li, K.; Xie, Y.; Pan, H.; Zhao, J.; Huang, L.; Zheng, X. The combined effects of nanotopography and Sr ion for enhanced osteogenic activity of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs). J. Biomater. Appl. 2017, 31, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnelye, E.; Chabadel, A.; Saltel, F.; Jurdic, P. Dual effect of strontium ranelate: Stimulation of osteoblast differentiation and inhibition of osteoclast formation and resorption in vitro. Bone 2008, 42, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, A.H.; Torres, A.L.; Vasconcelos, D.P.; Ribeiro-Machado, C.; Barbosa, J.N.; Barbosa, M.A.; Barrias, C.C.; Ribeiro, C.C. Osteogenic, anti-osteoclastogenic and immunomodulatory properties of a strontium-releasing hybrid scaffold for bone repair. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 99, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.Q.; Li, K.; Su, S.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, J. Effects of Zinc Ions Released From Ti-NW-Zn Surface on Osteogenesis and Angiogenesis In Vitro and in an In Vivo Zebrafish Model. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 848769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Cheng, M.; Wang, Q.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Chu, P.K.; Zhang, X. Zinc-Modified Sulfonated Polyetheretherketone Surface with Immunomodulatory Function for Guiding Cell Fate and Bone Regeneration. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chang, Q.; Xu, L.; Li, G.; Yang, G.; Ding, X.; Wang, X.; Cui, D.; Jiang, X. Graphene Oxide-Copper Nanocomposite-Coated Porous CaP Scaffold for Vascularized Bone Regeneration via Activation of Hif-1alpha. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, M.; Han, P.; Chen, L.; Chang, J.; Xiao, Y. Copper-containing mesoporous bioactive glass scaffolds with multifunctional properties of angiogenesis capacity, osteostimulation and antibacterial activity. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, A.; Renaudin, G.; Forestier, C.; Nedelec, J.M.; Descamps, S. Biological properties of copper-doped biomaterials for orthopedic applications: A review of antibacterial, angiogenic and osteogenic aspects. Acta Biomater. 2020, 117, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ye, X.; Li, W.; Lin, Z.; Wang, W.; Chen, L.; Li, Q.; Xie, X.; Xu, X.; Lu, Y. Copper-containing chitosan-based hydrogels enabled 3D-printed scaffolds to accelerate bone repair and eliminate MRSA-related infection. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 240, 124463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhou, Y.; Lei, Q.; Lin, D.; Chen, J.; Wu, C. Effect of inorganic phosphate on migration and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. BMC Dev. Biol. 2021, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhou, K.; Wang, M.; Wang, N.; Song, Y.; Xiong, W.; Guo, S.; Yi, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yang, S. Integrating physicomechanical and biological strategies for BTE: Biomaterials-induced osteogenic differentiation of MSCs. Theranostics 2023, 13, 3245–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Chang, J.; Wu, C. Bioactive scaffolds for osteochondral regeneration. J. Orthop. Transl. 2019, 17, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Leng, Y.; Bao, C.; Xu, S.L.; Wang, R.; Ren, F. Antibacterial coatings of fluoridated hydroxyapatite for percutaneous implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 95, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clews, C.; Dillon, S.; Nudelman, F.; Farquharson, C.; Stephen, L.A. Taking a closer look at matrix vesicle biogenesis. J. Bone Min. Res. 2025, 40, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; de Wildt, B.W.M.; Vis, M.A.M.; de Korte, C.E.; Ito, K.; Hofmann, S.; Yuana, Y. Matrix Vesicles: Role in Bone Mineralization and Potential Use as Therapeutics. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhayim, J.; van de Peppel, J.; Dudakovic, A.; Chiba, H.; van Wijnen, A.J.; van Leeuwen, J.P. Molecular characterization of human osteoblast-derived extracellular vesicle mRNA using next-generation sequencing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, H.C. Molecular biology of matrix vesicles. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1995, 314, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittur, F.; Stagni, N.; Moro, L.; de Bernard, B. Alkaline phosphatase binds to collagen; a hypothesis on the mechanism of extravesicular mineralization in epiphyseal cartilage. Experientia 1984, 40, 836–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, H.C. Matrix vesicles and calcification. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2003, 5, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbai-Ghoudan, R.; Nasello, G.; Perez, M.A.; Verbruggen, S.W.; Ruiz de Galarreta, S.; Rodriguez-Florez, N. In silico assessment of the bone regeneration potential of complex porous scaffolds. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 165, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, K.; Lin, F.; Xiang, L.; Deng, L.; Guan, Z.; Cui, W.; Zhang, H. Pharmaceutical electrospinning and 3D printing scaffold design for bone regeneration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 174, 504–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirankumar, S.; Gurusamy, N.; Rajasingh, S.; Sigamani, V.; Vasanthan, J.; Perales, S.G.; Rajasingh, J. Modern approaches on stem cells and scaffolding technology for osteogenic differentiation and regeneration. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 247, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Cao, L.; Chen, L.; Xiang, H. Recent advances in the application of nanogenerators in orthopedics: From body surface to implantation. Nano Energy 2025, 134, 110542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Chen, F.; Du, Y.; Gu, G.; Bai, T.; Lv, C.; et al. Spatiotemporally-graded BHP/G@met scaffold system enables sequential angiogenesis-osteogenesis coupling for accelerated bone regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 168177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Wang, J. Functionalized biomimetic mineralized collagen promotes osseointegration of 3D-printed titanium alloy microporous interface. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 24, 100896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, G.; Liu, M.; Xu, Z.; Chen, H.; Yang, L.; Lv, Y. Scaffold strategies for modulating immune microenvironment during bone regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 108, 110411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Q.; Gao, S.; Sun, N.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, L.; Huang, H.; Chen, Y.; Cai, L.; Yan, F. Immunomodulation, angiogenesis and osteogenesis based 3D-Printed bioceramics for High-Performance bone regeneration. Mater. Des. 2024, 238, 112732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Synnestvedt, M.B.; Chen, C.; Holmes, J.H. CiteSpace II: Visualization and knowledge discovery in bibliographic databases. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2005, 2005, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kawabori, M.; Shichinohe, H.; Kahata, K.; Miura, A.; Maeda, K.; Ito, Y.M.; Mukaino, M.; Kogawa, R.; Nakamura, K.; Gotoh, S.; et al. Phase I/II trial of intracerebral transplantation of autologous bone marrow stem cells combined with recombinant peptide scaffold for patients with chronic intracerebral haemorrhage: A study protocol. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e083959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.K.; Shim, B.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. Tissue-Engineered Bone Regeneration for Medium-to-Large Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head in the Weight-Bearing Portion: An Observational Study. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2024, 16, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponer, P.; Kucera, T.; Brtkova, J.; Urban, K.; Koci, Z.; Mericka, P.; Bezrouk, A.; Konradova, S.; Filipova, A.; Filip, S. Comparative Study on the Application of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Combined with Tricalcium Phosphate Scaffold into Femoral Bone Defects. Cell Transpl. 2018, 27, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, A.; Eubanks, E.; Edwards, S.; Aronovich, S.; Travan, S.; Rudek, I.; Wang, F.; Lanis, A.; Kaigler, D. Optimized cell survival and seeding efficiency for craniofacial tissue engineering using clinical stem cell therapy. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2014, 3, 1495–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrane, D.; Docquier, P.L.; Delloye, C.; Poirel, H.A.; Andre, W.; Aouassar, N. Scaffold-free Three-dimensional Graft From Autologous Adipose-derived Stem Cells for Large Bone Defect Reconstruction: Clinical Proof of Concept. Medicine 2015, 94, e2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thesleff, T.; Lehtimaki, K.; Niskakangas, T.; Mannerstrom, B.; Miettinen, S.; Suuronen, R.; Ohman, J. Cranioplasty with adipose-derived stem cells and biomaterial: A novel method for cranial reconstruction. Neurosurgery 2011, 68, 1535–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Gan, Y.; Shi, D.; Zhao, J.; Tang, T.; Dai, K. A novel cytotherapy device for rapid screening, enriching and combining mesenchymal stem cells into a biomaterial for promoting bone regeneration. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Y.; Dai, K.; Zhang, P.; Tang, T.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, J. The clinical use of enriched bone marrow stem cells combined with porous beta-tricalcium phosphate in posterior spinal fusion. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3973–3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Classification | Biological Functions | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Mg2+ |

| Enhances osteogenesis in various bone repair materials. |

| Sr2+ |

| First-line choice for treating osteoporotic bone defects. |

| Zn2+ | Used for infected bone defects and anti-infective implants. | |

| Cu2+ | For large/poorly vascularized or infected bone defects. | |

| Ca2+ and PO43− | Repairs large or hypovascular bone defects. | |

| Li+ | Used to promote bone regeneration, particularly showing potential in complex osteochondral interface repair. | |

| Other Bioactive Ions | Used for antibacterial coatings or dental materials. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xing, D.; Li, H. Biofunctionalization of Stem Cell Scaffold for Osteogenesis and Bone Regeneration. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121700

Chen Q, Jiang Y, Zhang X, Xu S, Wang Y, Xing D, Li H. Biofunctionalization of Stem Cell Scaffold for Osteogenesis and Bone Regeneration. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121700

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Qianqian, Yixue Jiang, Xiaoyuan Zhang, Shichun Xu, Yunwei Wang, Dan Xing, and Hui Li. 2025. "Biofunctionalization of Stem Cell Scaffold for Osteogenesis and Bone Regeneration" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121700

APA StyleChen, Q., Jiang, Y., Zhang, X., Xu, S., Wang, Y., Xing, D., & Li, H. (2025). Biofunctionalization of Stem Cell Scaffold for Osteogenesis and Bone Regeneration. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121700