Proteomic Validation of MEG-01-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Representative Models for Megakaryocyte- and Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

2.2. Reagents

2.3. Lentiviral Vector Preparation, Transduction of MEG-01 Cell Line and Cell Sorting

2.4. MEG-01 Differentiation Protocol

2.5. Cell, Platelets and Extracellular Vesicle Isolation

2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.7. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.8. ImageStream Analysis

2.9. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

2.10. Zeta Potential and Electrophoretic Mobility of Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

2.11. Protein Extraction, Digestion and Peptide Clean-Up

2.12. LC-MS/MS Analysis

2.13. Proteomics Data Analysis

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Fluorescence-Based Model for Tracking Cellular and Extracellular Vesicle Populations

3.2. Characterization of Megakaryocytic Differentiation in MEG-01 GFP+ Cells

3.3. Platelet-like Particles from VPA-Treated MEG-01 GFP+ Cells Mimic Activated Platelets

3.4. Characterization of Microvesicles (MVs) from VPA-Treated MEG-01 GFP+ Cells

3.5. Characterization of Exosomes (EXOs) from VPA-Treated MEG-01 GFP+ Cells

3.6. Proteomic Analysis Reveals Distinct Signatures and Functional Specialization of MEG-01-Derived Vesicles

3.7. Functional Proteomic Profiling Distinguishes PLPs from Native Platelets and MEG-01 Cells

3.8. Comparative Proteomics Identifies Conserved Hemostatic Programs in Platelet, Plasma and MEG-01-Derived MVs

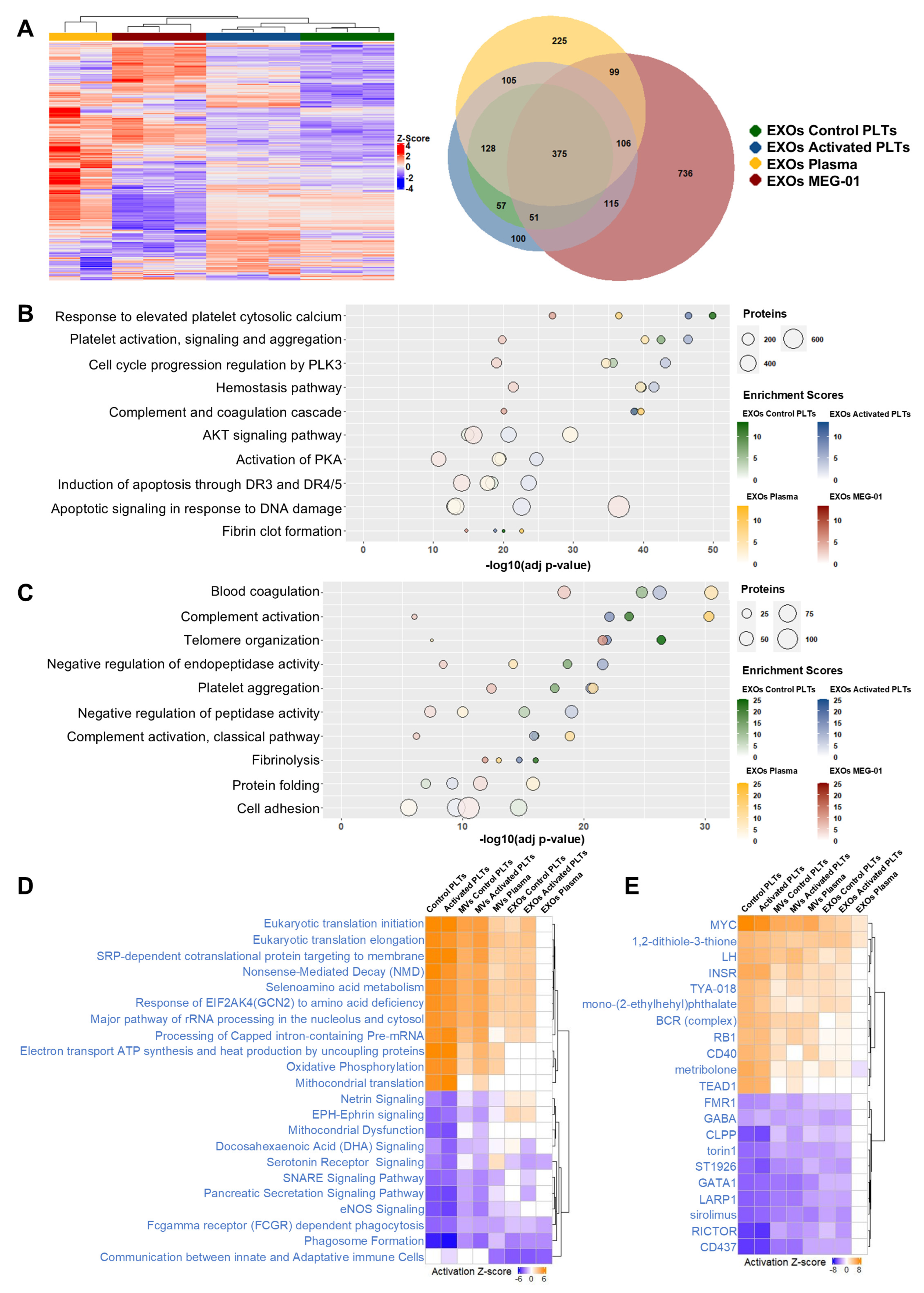

3.9. Exosome Proteomic Characterization Reveals Source-Specific Signatures and Conserved Hemostatic Functions

3.10. Differential Pathway Analysis Reveals Striking Functional Convergence Between EXOs of Plasma and EXOs of MEG-01

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EVs | Extracellular Vesicles |

| EXOs | Exosomes |

| hPSCs | Human Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| HSCs | Hematopoietic stem cells |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| MVs | Microvesicles |

| MVBs | Multivesicular Bodies |

| NTA | Nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| PLPs | Platelet-like particles |

| PLTs | Platelets |

| PRP | Human platelet-rich plasma |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| VPA | Valproic acid |

References

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xie, P.; Zhang, W. Liquid Biopsy: An Arsenal for Tumour Screening and Early Diagnosis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2024, 129, 102774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhm, F.; Boilard, E.; Machlus, K.R. Platelet Extracellular Vesicles: Beyond the Blood. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, M.G.; Sol, N.; Kooi, I.; Tannous, J.; Westerman, B.A.; Rustenburg, F.; Schellen, P.; Verschueren, H.; Post, E.; Koster, J.; et al. RNA-Seq of Tumor-Educated Platelets Enables Blood-Based Pan-Cancer, Multiclass, and Molecular Pathway Cancer Diagnostics. Cancer Cell 2015, 28, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafi, S.; Asemani, Y.; Majidpoor, J.; Mahmoudi, R.; Aghaei-Zarch, S.M.; Mortezaee, K. Tumor-Educated Platelets. Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 552, 117690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Sadida, H.Q.; Marzooqi, S.A.; Jerobin, J.; Altemani, F.H.; Algehainy, N.; Alanazi, M.A.; Abou-Samra, A.-B.; Kumar, R.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles as Tools and Targets in Therapy for Diseases. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Wang, S.; Yu, X.; He, X.; Guo, H.; Ou, C. Current Status and Future Perspectives of Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Kelliher, S.; Krishnan, A. Heterogeneity of Platelets and Their Responses. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 8, 102356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R.; Anjum, A.; Nicolai, L. Platelet Heterogeneity in Disease—The Many and the Diverse? Blood 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, F. In Vitro Generation of Megakaryocytes and Platelets. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 713434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, J. New Insights into the Generation and Function of Megakaryocytes in Health and Disease. Haematologica 2025, 110, 1500–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Albaira, K.I.; Kang, J.; Cho, Y.G.; Kwon, S.S.; Lee, J.; Ko, D.-H.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.Y. Cell-Based Artificial Platelet Production: Historical Milestones, Emerging Trends, and Future Directions. Blood Res. 2025, 60, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Buduo, C.A.; Aguilar, A.; Soprano, P.M.; Bocconi, A.; Miguel, C.P.; Mantica, G.; Balduini, A. Latest Culture Techniques: Cracking the Secrets of Bone Marrow to Mass-Produce Erythrocytes and Platelets Ex Vivo. Haematologica 2021, 106, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elcheva, I.; Brok-Volchanskaya, V.; Kumar, A.; Liu, P.; Lee, J.-H.; Tong, L.; Vodyanik, M.; Swanson, S.; Stewart, R.; Kyba, M.; et al. Direct Induction of Haematoendothelial Programs in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells by Transcriptional Regulators. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, M.G.; Navarro-Montero, O.; Ayllon, V.; Ramos-Mejia, V.; Guerrero-Carreno, X.; Bueno, C.; Romero, T.; Lamolda, M.; Cobo, M.; Martin, F.; et al. SCL/TAL1-Mediated Transcriptional Network Enhances Megakaryocytic Specification of Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wang, H.; Wen, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Su, P.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Shi, L.; et al. MEIS2 Regulates Endothelial to Hematopoietic Transition of Human Embryonic Stem Cells by Targeting TAL1. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, T.; Evans, A.L.; Ghevaert, C.J.G. Differentiation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells to Megakaryocytes by Transcription Factor-Driven Forward Programming. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1812, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Takayama, N.; Hirata, S.; Seo, H.; Endo, H.; Ochi, K.; Fujita, K.; Koike, T.; Harimoto, K.; Dohda, T.; et al. Expandable Megakaryocyte Cell Lines Enable Clinically Applicable Generation of Platelets from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battinelli, E.; Willoughby, S.R.; Foxall, T.; Valeri, C.R.; Loscalzo, J. Induction of Platelet Formation from Megakaryocytoid Cells by Nitric Oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14458–14463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.; Allen, S.; Mennan, C.; Platt, M.; Wright, K.; Kehoe, O. Extracellular Vesicle Depletion Protocols of Foetal Bovine Serum Influence Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Phenotype, Immunomodulation, and Particle Release. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweinfurth, N.; Hohmann, S.; Deuschle, M.; Lederbogen, F.; Schloss, P. Valproic Acid and All Trans Retinoic Acid Differentially Induce Megakaryopoiesis and Platelet-like Particle Formation from the Megakaryoblastic Cell Line MEG-01. Platelets 2010, 21, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Minh, A.; Star, A.T.; Stupak, J.; Fulton, K.M.; Haqqani, A.S.; Gélinas, J.-F.; Li, J.; Twine, S.M.; Kamen, A.A. Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles Secreted in Lentiviral Producing HEK293SF Cell Cultures. Viruses 2021, 13, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.S.; Moggridge, S.; Müller, T.; Sorensen, P.H.; Morin, G.B.; Krijgsveld, J. Single-Pot, Solid-Phase-Enhanced Sample Preparation for Proteomics Experiments. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballman, K.V.; Grill, D.E.; Oberg, A.L.; Therneau, T.M. Faster Cyclic Loess: Normalizing RNA Arrays via Linear Models. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 2778–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma Powers Differential Expression Analyses for RNA-Sequencing and Microarray Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z. Complex Heatmap Visualization. iMeta 2022, 1, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Maaten, L. Accelerating T-SNE Using Tree-Based Algorithms. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 3221–3245. [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the Unification of Biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gene Ontology Consortium; Aleksander, S.A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J.M.; Drabkin, H.J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N.L.; et al. The Gene Ontology Knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224, iyad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milacic, M.; Beavers, D.; Conley, P.; Gong, C.; Gillespie, M.; Griss, J.; Haw, R.; Jassal, B.; Matthews, L.; May, B.; et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase 2024. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, D672–D678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Grishagin, I.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Greene, J.; Obenauer, J.C.; Ngan, D.; Nguyen, D.-T.; Guha, R.; Jadhav, A.; et al. The NCATS BioPlanet—An Integrated Platform for Exploring the Universe of Cellular Signaling Pathways for Toxicology, Systems Biology, and Chemical Genomics. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Moreno, A.; López-Domínguez, R.; Villatoro-García, J.A.; Ramirez-Mena, A.; Aparicio-Puerta, E.; Hackenberg, M.; Pascual-Montano, A.; Carmona-Saez, P. Functional Enrichment Analysis of Regulatory Elements. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, A.; Green, J.; Pollard, J.; Tugendreich, S. Causal Analysis Approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.R.; Hartwig, J.H.; Italiano, J.E. The Biogenesis of Platelets from Megakaryocyte Proplatelets. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 3348–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, J.M.; Williams, J.K.; Zhang, C.; Saleh, A.H.; Liu, X.-M.; Ma, L.; Schekman, R. Extracellular Vesicles and Cellular Homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2025, 94, 587–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croci, O.; De Fazio, S.; Biagioni, F.; Donato, E.; Caganova, M.; Curti, L.; Doni, M.; Sberna, S.; Aldeghi, D.; Biancotto, C.; et al. Transcriptional Integration of Mitogenic and Mechanical Signals by Myc and YAP. Genes. Dev. 2017, 31, 2017–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, D.-I.; Aldridge, G.M.; Weiler, I.J.; Greenough, W.T. Altered mRNA Transport, Docking, and Protein Translation in Neurons Lacking Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 15601–15606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Comparison of Methods for the Isolation and Separation of Extracellular Vesicles from Protein and Lipid Particles in Human Serum|Scientific Reports. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-57497-7 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Multia, E.; Tear, C.J.Y.; Palviainen, M.; Siljander, P.; Riekkola, M.-L. Fast Isolation of Highly Specific Population of Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles from Blood Plasma by Affinity Monolithic Column, Immobilized with Anti-Human CD61 Antibody. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1091, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rommel, M.G.E.; Hoerster, K.; Milde, C.; Schenk, F.; Roser, L.; Kohlscheen, S.; Heinz, N.; Modlich, U. Signaling Properties of Murine MPL and MPL Mutants after Stimulation with Thrombopoietin and Romiplostim. Exp. Hematol. 2020, 85, 33–46.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, L.J.; Huntsman, H.D.; Cheng, H.; Townsley, D.M.; Winkler, T.; Feng, X.; Dunbar, C.E.; Young, N.S.; Larochelle, A. Eltrombopag Maintains Human Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells under Inflammatory Conditions Mediated by IFN-γ. Blood 2019, 133, 2043–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Large-Scale Production of Megakaryocytes from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells by Chemically Defined Forward Programming|Nature Communications. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms11208 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Martinez-Navajas, G.; Ceron-Hernandez, J.; Simon, I.; Lupiañez, P.; Diaz-McLynn, S.; Perales, S.; Modlich, U.; Guerrero, J.A.; Martin, F.; Sevivas, T.; et al. Lentiviral Gene Therapy Reverts GPIX Expression and Phenotype in Bernard-Soulier Syndrome Type C. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 33, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourquin, J.-P.; Subramanian, A.; Langebrake, C.; Reinhardt, D.; Bernard, O.; Ballerini, P.; Baruchel, A.; Cavé, H.; Dastugue, N.; Hasle, H.; et al. Identification of Distinct Molecular Phenotypes in Acute Megakaryoblastic Leukemia by Gene Expression Profiling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 3339–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, N.; Nishimura, S.; Nakamura, S.; Shimizu, T.; Ohnishi, R.; Endo, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Otsu, M.; Nishimura, K.; Nakanishi, M.; et al. Transient Activation of C-MYC Expression Is Critical for Efficient Platelet Generation from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 2817–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Giap, C.; Lazo, J.S.; Prochownik, E.V. Low Molecular Weight Inhibitors of Myc-Max Interaction and Function. Oncogene 2003, 22, 6151–6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyce, A.; Degenhardt, Y.; Bai, Y.; Le, B.; Korenchuk, S.; Crouthame, M.-C.; McHugh, C.F.; Vessella, R.; Creasy, C.L.; Tummino, P.J.; et al. Inhibition of BET Bromodomain Proteins as a Therapeutic Approach in Prostate Cancer. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 2419–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Grafton, F.; Ranjbarvaziri, S.; Budan, A.; Farshidfar, F.; Cho, M.; Xu, E.; Ho, J.; Maddah, M.; Loewke, K.E.; et al. Phenotypic Screening with Deep Learning Identifies HDAC6 Inhibitors as Cardioprotective in a BAG3 Mouse Model of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabl5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messaoudi, K.; Ali, A.; Ishaq, R.; Palazzo, A.; Sliwa, D.; Bluteau, O.; Souquère, S.; Muller, D.; Diop, K.M.; Rameau, P.; et al. Critical Role of the HDAC6-Cortactin Axis in Human Megakaryocyte Maturation Leading to a Proplatelet-Formation Defect. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceron-Hernandez, J.; Martinez-Navajas, G.; Sanchez-Manas, J.M.; Molina, M.P.; Xie, J.; Aznar-Peralta, I.; Garcia-Diaz, A.; Perales, S.; Torres, C.; Serrano, M.J.; et al. Oncogenic KRASG12D Transfer from Platelet-like Particles Enhances Proliferation and Survival in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, R.P.; Mizenko, R.R.; Bozkurt, B.T.; Lowe, N.; Henson, T.; Arizzi, A.; Wang, A.; Tan, C.; George, S.C. Harnessing Extracellular Vesicle Heterogeneity for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2025, 20, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Paulo, J.A.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Nguyen, A.; Cheng, Y.; Massick, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jeppesen, D.K.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Heterogeneity of Extracellular Vesicles and Non-Vesicular Nanoparticles in Glioblastoma. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2025, 14, e70168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.; Willms, E.; Hill, A.F. Understanding Extracellular Vesicle and Nanoparticle Heterogeneity: Novel Methods and Considerations. Proteomics 2021, 21, e2000118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Freitas, D.; Kim, H.S.; Fabijanic, K.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Martin, A.B.; Bojmar, L.; et al. Identification of Distinct Nanoparticles and Subsets of Extracellular Vesicles by Asymmetric Flow Field-Flow Fractionation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italiano, J.E.; Mairuhu, A.T.A.; Flaumenhaft, R. Clinical Relevance of Microparticles from Platelets and Megakaryocytes. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2010, 17, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaumenhaft, R.; Dilks, J.R.; Richardson, J.; Alden, E.; Patel-Hett, S.R.; Battinelli, E.; Klement, G.L.; Sola-Visner, M.; Italiano, J.E. Megakaryocyte-Derived Microparticles: Direct Visualization and Distinction from Platelet-Derived Microparticles. Blood 2009, 113, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcar, M.; Marić, I.; Tertel, T.; Goričar, K.; Čegovnik Primožič, U.; Černe, D.; Giebel, B.; Lenassi, M. Comprehensive Phenotyping of Extracellular Vesicles in Plasma of Healthy Humans—Insights Into Cellular Origin and Biological Variation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2025, 14, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, C.; Koupenova, M.; Machlus, K.R.; Sen Gupta, A. Beyond the Thrombus: Platelet-Inspired Nanomedicine Approaches in Inflammation, Immune Response, and Cancer. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 20, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Zhao, T.; Song, N.; Pan, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Chen, P.; Zhang, J.; Xia, C. Platelets and Platelet Extracellular Vesicles in Drug Delivery Therapy: A Review of the Current Status and Future Prospects. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1026386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bandla, C.; Kundu, D.J.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Bai, J.; Hewapathirana, S.; John, N.S.; Prakash, A.; Walzer, M.; Wang, S.; et al. The PRIDE Database at 20 Years: 2025 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D543–D553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanchez-Manas, J.M.; Perales, S.; Martinez-Navajas, G.; Ceron-Hernandez, J.; Lopez, C.M.; Peralbo-Molina, A.; Delgado, J.R.; Martinez-Galan, J.; Ramos-Mejia, V.; Chicano-Galvez, E.; et al. Proteomic Validation of MEG-01-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Representative Models for Megakaryocyte- and Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1698. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121698

Sanchez-Manas JM, Perales S, Martinez-Navajas G, Ceron-Hernandez J, Lopez CM, Peralbo-Molina A, Delgado JR, Martinez-Galan J, Ramos-Mejia V, Chicano-Galvez E, et al. Proteomic Validation of MEG-01-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Representative Models for Megakaryocyte- and Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1698. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121698

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanchez-Manas, Jose Manuel, Sonia Perales, Gonzalo Martinez-Navajas, Jorge Ceron-Hernandez, Cristina M. Lopez, Angela Peralbo-Molina, Juan R. Delgado, Joaquina Martinez-Galan, Veronica Ramos-Mejia, Eduardo Chicano-Galvez, and et al. 2025. "Proteomic Validation of MEG-01-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Representative Models for Megakaryocyte- and Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1698. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121698

APA StyleSanchez-Manas, J. M., Perales, S., Martinez-Navajas, G., Ceron-Hernandez, J., Lopez, C. M., Peralbo-Molina, A., Delgado, J. R., Martinez-Galan, J., Ramos-Mejia, V., Chicano-Galvez, E., Hernandez-Valladares, M., Ortuno, F. M., Torres, C., & Real, P. J. (2025). Proteomic Validation of MEG-01-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Representative Models for Megakaryocyte- and Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1698. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121698