Bioinformatics-Driven, Plant-Based Antibiotic Research Against Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli Multiresistant Microbes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Biofilm and Quorum Sensing in Antibiotic Resistance

3. Pseudomonas aeruginosa

3.1. Group Behavior in P. aeruginosa: Tolerance and Resistance to Antibiotics

3.2. QS Systems in P. aeruginosa

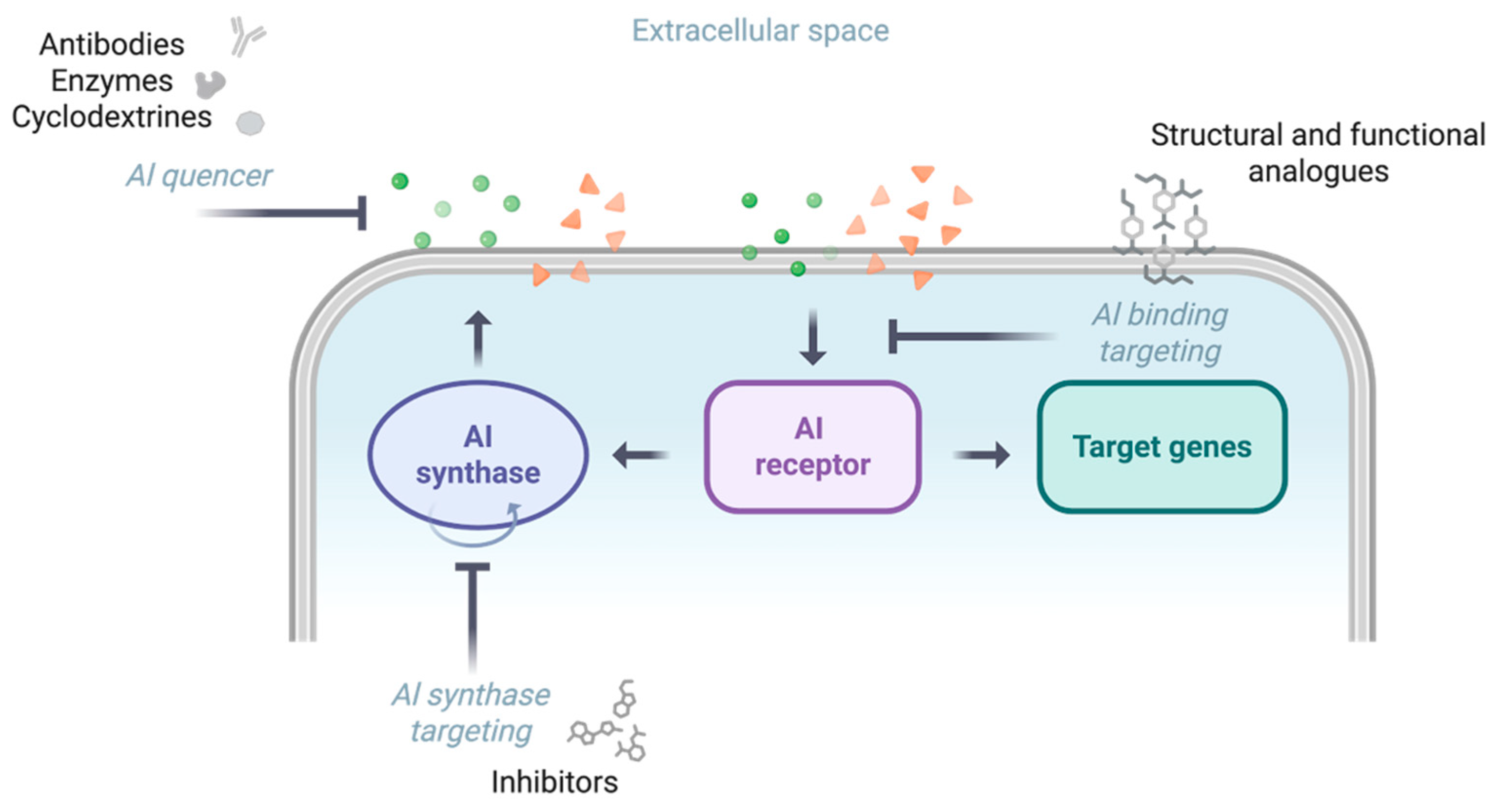

3.3. QS Inhibition as a Potential Anti-Pathogenicity Strategy Against P. aeruginosa

4. Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC)

4.1. Antibiotic Tolerance and Resistance Mechanisms in UPEC

4.2. QS Systems in UPEC

4.3. Therapeutic Interventions Targeting QS and Biofilms in UPEC

5. Emerging Trends in Bioinformatics for QS Research

5.1. Bioinformatics and Artificial Intelligence in Natural Product Discovery

5.2. Virtual Screening and Structure-Based Strategies for Targeting QS

5.2.1. Protein Modeling for QS Targets

5.2.2. Virtual Screening of Anti-QS Natural Compounds

5.2.3. Molecular Dynamics for Hit Validation

5.3. Methodological Reproducibility in Computational QS Research

6. Identifying Natural and Synthetic QS Inhibitors

6.1. Ethnobotanical Approaches to Selecting Medicinal Plants

6.2. Plants as Resources of Novel Antibiotics

6.3. In Vitro Testing of Biofilm Formation Inhibition

6.4. Phytochemical Classes with Anti-QS and Anti-Biofilm Activity

6.4.1. Flavonoids

6.4.2. Alkaloids

6.4.3. Terpenoids

6.4.4. Sesquiterpene Lactones

6.4.5. Phenolic Compounds

6.4.6. Other Natural Chemical Compound Classes

7. Clinical Relevance and Translational Constraints of QS-Targeted Strategies

8. Conclusions

9. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Global Threat. Available online: https://www.unep.org/topics/chemicals-and-pollution-action/chemicals-management/pollution-and-health/antimicrobial (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- European Commission. One Health: Overview. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/one-health/overview_en (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T.R.; Gales, A.C.; Laxminarayan, R.; Dodd, P.C. Antimicrobial Resistance: Addressing a Global Threat to Humanity. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, J.S.; Jeggo, M. The One Health Approach—Why Is It So Important? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destoumieux-Garzón, D.; Mavingui, P.; Boetsch, G.; Boissier, J.; Darriet, F.; Duboz, P.; Fritsch, C.; Giraudoux, P.; Le Roux, F.; Morand, S.; et al. The One Health Concept: 10 Years Old and a Long Road Ahead. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, W.Y.; Getachew, M.; Tegegne, B.A.; Teffera, Z.H.; Dagne, A.; Zeleke, T.K.; Wondm, S.A.; Abebe, R.B.; Gedif, A.A.; Fenta, A.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance with a Focus on Antibacterial, Antifungal, Antimalarial, and Antiviral Drugs Resistance, Its Threat, Global Priority Pathogens, Prevention, and Control Strategies: A Review. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, 20499361251340144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muteeb, G.; Rehman, M.T.; Shahwan, M.; Aatif, M. Origin of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance, and Their Impacts on Drug Development: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowan, M.M. Plant Products as Antimicrobial Agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, S.; Jia, W.; Guo, T.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Yao, Z. Natural Antimicrobials from Plants: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, J.M.; Yang, K.; Swanson, K.; Jin, W.; Cubillos-Ruiz, A.; Donghia, N.M.; MacNair, C.R.; French, S.; Carfrae, L.A.; Bloom-Ackermann, Z.; et al. A Deep Learning Approach to Antibiotic Discovery. Cell 2020, 180, 688–702.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, A.; McKay, C.; Tanner, J.J.; Cheng, J. Artificial Intelligence in the Prediction of Protein–Ligand Interactions: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesse, L.L.; Osland, A.M.; Asal, B.; Mo, S.S. Evolution of Antimicrobial Resistance in E. coli Biofilm Treated with High Doses of Ciprofloxacin. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1246895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, A.; Höller, B.M.; Molin, S.; Zechner, E.L. Synergistic Effects in Mixed Escherichia coli Biofilms: Conjugative Plasmid Transfer Drives Biofilm Expansion. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 3582–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uruén, C.; Chopo-Escuin, G.; Tommassen, J.; Mainar-Jaime, R.C.; Arenas, J. Biofilms as Promoters of Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance and Tolerance. Antibiotics 2020, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenlehner, F.; Lorenz, H.; Ewald, O.; Gerke, P. Why D-Mannose May Be as Efficient as Antibiotics in the Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Lower Urinary Tract Infections—Preliminary Considerations and Conclusions from a Non-Interventional Study. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilsen, M.P.; Jongeneel, R.M.H.; Schneeberger, C.; Platteel, T.N.; Van Nieuwkoop, C.; Mody, L.; Caterino, J.M.; Geerlings, S.E.; Köves, B.; Wagenlehner, F.; et al. Definitions of Urinary Tract Infection in Current Research: A Systematic Review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Vietinghoff, S.; Shevchuk, O.; Dobrindt, U.; Engel, D.R.; Jorch, S.K.; Kurts, C.; Miethke, T.; Wagenlehner, F. The Global Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance—Urinary Tract Infections. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024, 39, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrollahian, S.; Graham, J.P.; Halaji, M. A Review of the Mechanisms That Confer Antibiotic Resistance in Pathotypes of E. coli. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1387497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafaque, Z.; Abid, N.; Liaquat, N.; Afridi, P.; Siddique, S.; Masood, S.; Kanwal, S.; Iqbal Dasti, J. In-Vitro Investigation of Antibiotics Efficacy Against Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Biofilms and Antibiotic Induced Biofilm Formation at Sub-Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Ciprofloxacin. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 2801–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schembri, M.A.; Christiansen, G.; Klemm, P. FimH-mediated Autoaggregation of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 41, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, K.; Singh, S.; Singh, M.; Parabia, F.; Chandrasekhar, K. Algal Biofilms: Potential Wastewater Treatment Applications and Biotechnological Significance. In Application of Biofilms in Applied Microbiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 203–233. ISBN 978-0-323-90513-8. [Google Scholar]

- Nealson, K.H.; Platt, T.; Hastings, J.W. Cellular Control of the Synthesis and Activity of the Bacterial Luminescent System. J. Bacteriol. 1970, 104, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engebrecht, J.; Nealson, K.; Silverman, M. Bacterial Bioluminescence: Isolation and Genetic Analysis of Functions from Vibrio fischeri. Cell 1983, 32, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engebrecht, J.; Silverman, M. Identification of Genes and Gene Products Necessary for Bacterial Bioluminescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 4154–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Urretavizcaya, B.; Vilaplana, L.; Marco, M.-P. Strategies for Quorum Sensing Inhibition as a Tool for Controlling Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, N.K.; Mazaitis, M.J.; Costerton, J.W.; Leid, J.G.; Powers, M.E.; Shirtliff, M.E. Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms: Properties, Regulation, and Roles in Human Disease. Virulence 2011, 2, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, K.; Stoodley, P.; Goeres, D.M.; Hall-Stoodley, L.; Burmølle, M.; Stewart, P.S.; Bjarnsholt, T. The Biofilm Life Cycle: Expanding the Conceptual Model of Biofilm Formation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, V.; Rohn, J.L.; Stoodley, P.; Carugo, D.; Stride, E. Drug Delivery Strategies for Antibiofilm Therapy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Hou, K.; Valencak, T.G.; Luo, X.M.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. AI-2/LuxS Quorum Sensing System Promotes Biofilm Formation of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG and Enhances the Resistance to Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in Germ-Free Zebrafish. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00610-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.; Borges, A.; Flament-Simon, S.-C.; Simões, M. Quorum Sensing Architecture Network in Escherichia coli Virulence and Pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal Jimenez, P.; Koch, G.; Thompson, J.A.; Xavier, K.B.; Cool, R.H.; Quax, W.J. The Multiple Signaling Systems Regulating Virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, X. The Pseudomonas Quinolone Signal (PQS): Not Just for Quorum Sensing Anymore. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya, J.; Montagut, E.-J.; Marco, M.-P. Analysing the Integrated Quorum Sensing (Iqs) System and Its Potential Role in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1575421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Cámara, M. Quorum Sensing and Environmental Adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A Tale of Regulatory Networks and Multifunctional Signal Molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009, 12, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zeng, J.; Chang, Y.; Han, S.; Zhao, J.; Fan, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Zou, X.; Wang, C.; et al. Risk Factors for Mortality of Inpatients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bacteremia in China: Impact of Resistance Profile in the Mortality. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 4115–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuon, F.F.; Dantas, L.R.; Suss, P.H.; Tasca Ribeiro, V.S. Pathogenesis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm: A Review. Pathogens 2022, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Buchad, H.; Gajjar, D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Persister Cell Formation upon Antibiotic Exposure in Planktonic and Biofilm State. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, B.W.; Valenta, J.A.; Benedik, M.J.; Wood, T.K. Arrested Protein Synthesis Increases Persister-Like Cell Formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 1468–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. Multidrug Tolerance of Biofilms and Persister Cells. In Bacterial Biofilms; Romeo, T., Ed.; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 322, pp. 107–131. ISBN 978-3-540-75417-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.; Joshi-Datar, A.; Lepine, F.; Bauerle, E.; Olakanmi, O.; Beer, K.; McKay, G.; Siehnel, R.; Schafhauser, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Active Starvation Responses Mediate Antibiotic Tolerance in Biofilms and Nutrient-Limited Bacteria. Science 2011, 334, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.; Alexandre, K.; Etienne, M. Tolerance and Persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Biofilms Exposed to Antibiotics: Molecular Mechanisms, Antibiotic Strategies and Therapeutic Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haagensen, J.; Verotta, D.; Huang, L.; Engel, J.; Spormann, A.M.; Yang, K. Spatiotemporal Pharmacodynamics of Meropenem- and Tobramycin-Treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 3357–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.; Price-Whelan, A.; Dietrich, L.E.P. Gradients and Consequences of Heterogeneity in Biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciofu, O.; Rojo-Molinero, E.; Macià, M.D.; Oliver, A. Antibiotic Treatment of Biofilm Infections. APMIS 2017, 125, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.W.; Mah, T.-F. Molecular Mechanisms of Biofilm-Based Antibiotic Resistance and Tolerance in Pathogenic Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrusson, F.; Varet, H.; Nguyen, T.K.; Legendre, R.; Sismeiro, O.; Coppée, J.-Y.; Wolz, C.; Tenson, T.; Van Bambeke, F. Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus Persisters upon Antibiotic Exposure. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnsholt, T.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Burmølle, M.; Hentzer, M.; Haagensen, J.A.J.; Hougen, H.P.; Calum, H.; Madsen, K.G.; Moser, C.; Molin, S.; et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Tolerance to Tobramycin, Hydrogen Peroxide and Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes Is Quorum-Sensing Dependent. Microbiology 2005, 151, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brackman, G.; Cos, P.; Maes, L.; Nelis, H.J.; Coenye, T. Quorum Sensing Inhibitors Increase the Susceptibility of Bacterial Biofilms to Antibiotics In Vitro and In Vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 2655–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, R.; Que, Y.A.; Maura, D.; Strobel, B.; Majcherczyk, P.A.; Hopper, L.R.; Wilbur, D.J.; Hreha, T.N.; Barquera, B.; Rahme, L.G. Auto Poisoning of the Respiratory Chain by a Quorum-Sensing-Regulated Molecule Favors Biofilm Formation and Antibiotic Tolerance. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, S.H.; Tse, E.C.M.; Yates, M.D.; Otero, F.J.; Trammell, S.A.; Stemp, E.D.A.; Barton, J.K.; Tender, L.M.; Newman, D.K. Extracellular DNA Promotes Efficient Extracellular Electron Transfer by Pyocyanin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Cell 2020, 182, 919–932.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, I.; Manfredi, P.; Maffei, E.; Egli, A.; Jenal, U. Evolution of Antibiotic Tolerance Shapes Resistance Development in Chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. mBio 2021, 12, e03482-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potron, A.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. Emerging Broad-Spectrum Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii: Mechanisms and Epidemiology. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 568–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio, R.; Mancheño, M.; Viedma, E.; Villa, J.; Orellana, M.Á.; Lora-Tamayo, J.; Chaves, F. Predictors of Mortality in Bloodstream Infections Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance and Bacterial Virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01759-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alav, I.; Sutton, J.M.; Rahman, K.M. Role of Bacterial Efflux Pumps in Biofilm Formation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2003–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.P.; Van Delden, C.; Iglewski, B.H. Active Efflux and Diffusion Are Involved in Transport of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Cell-to-Cell Signals. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horna, G.; López, M.; Guerra, H.; Saénz, Y.; Ruiz, J. Interplay between MexAB-OprM and MexEF-OprN in Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillis, R.J.; White, K.G.; Choi, K.-H.; Wagner, V.E.; Schweizer, H.P.; Iglewski, B.H. Molecular Basis of Azithromycin-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 3858–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, Z.; Gholami, M.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.A.; Goli, H.R. The Role of MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN Efflux Systems in the Multiple Antibiotic Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Clinical Samples. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraud, S.; Campigotto, A.J.; Chen, Z.; Poole, K. MexCD-OprJ Multidrug Efflux System of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Involvement in Chlorhexidine Resistance and Induction by Membrane-Damaging Agents Dependent upon the AlgU Stress Response Sigma Factor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 4478–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarche, M.G.; Déziel, E. MexEF-OprN Efflux Pump Exports the Pseudomonas Quinolone Signal (PQS) Precursor HHQ (4-Hydroxy-2-Heptylquinoline). PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhtah, H.; Koyama, L.; Zhang, Y.; Morales, D.K.; Fields, B.L.; Price-Whelan, A.; Hogan, D.A.; Shepard, K.; Dietrich, L.E.P. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa Efflux Pump MexGHI-OpmD Transports a Natural Phenazine That Controls Gene Expression and Biofilm Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E3538–E3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Mah, T.-F. Involvement of a Novel Efflux System in Biofilm-Specific Resistance to Antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 4447–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Wu, M.; Xu, J. Outer Membrane Vesicle Contributes to the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Resistance to Antimicrobial Peptides in the Acidic Airway of Bronchiectasis Patients. MedComm 2025, 6, e70084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Erickson, S.K.; Goldberg, L.R.; Hills, S.; Radin, A.G.B.; Schertzer, J.W. OprF Functions as a Latch to Direct Outer Membrane Vesicle Release in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qian, C.; Tang, M.; Zeng, W.; Kong, J.; Fu, C.; Xu, C.; Ye, J.; Zhou, T. Carbapenemase-Loaded Outer Membrane Vesicles Protect Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Degrading Imipenem and Promoting Mutation of Antimicrobial Resistance Gene. Drug Resist. Updat. 2023, 68, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florez, C.; Raab, J.E.; Cooke, A.C.; Schertzer, J.W. Membrane Distribution of the Pseudomonas Quinolone Signal Modulates Outer Membrane Vesicle Production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 2017, 8, e01034-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashburn-Warren, L.; Howe, J.; Brandenburg, K.; Whiteley, M. Structural Requirements of the Pseudomonas Quinolone Signal for Membrane Vesicle Stimulation. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 3411–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulianello, L.; Canard, C.; Köhler, T.; Caille, D.; Lacroix, J.-S.; Meda, P. Rhamnolipids Are Virulence Factors That Promote Early Infiltration of Primary Human Airway Epithelia by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 3134–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, S.; McDermott, C.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; McFarland, A.; Forbes, A.; Perkins, A.; Davey, A.; Chess-Williams, R.; Kiefel, M.; Arora, D.; et al. Cellular Effects of Pyocyanin, a Secreted Virulence Factor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Toxins 2016, 8, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scribani Rossi, C.; Eckartt, K.; Scarchilli, E.; Angeli, S.; Price-Whelan, A.; Di Matteo, A.; Chevreuil, M.; Raynal, B.; Arcovito, A.; Giacon, N.; et al. Molecular Insights into RmcA-Mediated c-Di-GMP Consumption: Linking Redox Potential to Biofilm Morphogenesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 277, 127498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, C.; Shoemark, A.; Chan, M.; Ollosson, S.; Dixon, M.; Hogg, C.; Alton, E.W.F.W.; Davies, J.C.; Williams, H.D. Cyanide Levels Found in Infected Cystic Fibrosis Sputum Inhibit Airway Ciliary Function. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiley, M.K.; Sekaran, D.C.; Price-Whelan, A.; Dietrich, L.E.P. Cyanide-Dependent Control of Terminal Oxidase Hybridization by Pseudomonas aeruginosa MpaR. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanmardi, F.; Emami, A.; Pirbonyeh, N.; Keshavarzi, A.; Rajaee, M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Exo-Toxins Prevalence in Hospital Acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 75, 104037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambello, M.J.; Kaye, S.; Iglewski, B.H. LasR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Is a Transcriptional Activator of the Alkaline Protease Gene (Apr) and an Enhancer of Exotoxin A Expression. Infect. Immun. 1993, 61, 1180–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogardt, M.; Schmoldt, S.; Götzfried, M.; Adler, K.; Heesemann, J. Pitfalls of Polymyxin Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Cystic Fibrosis Patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Muñoz-Cázares, N.; Castillo-Juárez, I.; García-Contreras, R.; Castro-Torres, V.A.; Díaz-Guerrero, M.; Rodríguez-Zavala, J.S.; Quezada, H.; González-Pedrajo, B.; Martínez-Vázquez, M. A Brominated Furanone Inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum Sensing and Type III Secretion, Attenuating Its Virulence in a Murine Cutaneous Abscess Model. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariminik, A.; Baseri-Salehi, M.; Kheirkhah, B. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum Sensing Modulates Immune Responses: An Updated Review Article. Immunol. Lett. 2017, 190, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkina, M.V.; Vikström, E. Bacteria-Host Crosstalk: Sensing of the Quorum in the Context of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. J. Innate Immun. 2019, 11, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-S.; Winans, S.C. LuxR-Type Quorum-Sensing Regulators That Are Detached from Common Scents: LuxR-Type Apoproteins. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 77, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Aceves, M.P.; Cocotl-Yañez, M.; Servín-González, L.; Soberón-Chávez, G. The Rhl Quorum-Sensing System Is at the Top of the Regulatory Hierarchy under Phosphate-Limiting Conditions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 2021, 203, e00475-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, J.P.; Pesci, E.C.; Iglewski, B.H. Roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Las and Rhl Quorum-Sensing Systems in Control of Elastase and Rhamnolipid Biosynthesis Genes. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 5756–5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Moustafa, D.; Smith, C.D.; Goldberg, J.B.; Bassler, B.L. The RhlR Quorum-Sensing Receptor Controls Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pathogenesis and Biofilm Development Independently of Its Canonical Homoserine Lactone Autoinducer. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugani, S.A.; Whiteley, M.; Lee, K.M.; D’Argenio, D.; Manoil, C.; Greenberg, E.P. QscR, a Modulator of Quorum-Sensing Signal Synthesis and Virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 2752–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, F.; Oinuma, K.-I.; Smalley, N.E.; Schaefer, A.L.; Hamwy, O.; Greenberg, E.P.; Dandekar, A.A. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa Orphan Quorum Sensing Signal Receptor QscR Regulates Global Quorum Sensing Gene Expression by Activating a Single Linked Operon. mBio 2018, 9, e01274-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, C.; Park, S.J.; Im, S.-J.; Park, S.-J.; Lee, J.-H. Interspecies Signaling through QscR, a Quorum Receptor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Cells 2012, 33, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Kong, W.; Jin, S.; Chen, L.; Xu, Y.; Duan, K. Pqs R-dependent and Pqs R-independent Regulation of Motility and Biofilm Formation by PQS in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Basic Microbiol. 2014, 54, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Z.-Y.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Yang, M.-H.; Huang, Y.-J.; Lin, J.; Chen, W.-M. 3-Hydroxypyridin-4(1H)-One Derivatives as Pqs Quorum Sensing Inhibitors Attenuate Virulence and Reduce Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 15823–15846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, S.L.; Iglewski, B.H.; Pesci, E.C. The Pseudomonas Quinolone Signal Regulates Rhl Quorum Sensing in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 2702–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Aceves, M.P.; Smalley, N.E.; Schaefer, A.L.; Greenberg, E.P. The Relationship between Pqs Gene Expression and Acylhomoserine Lactone Signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2025, 207, e00475-24, Erratum in J. Bacteriol. 2024, 206, e0138-24. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00138-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredenbruch, F.; Geffers, R.; Nimtz, M.; Buer, J.; Häussler, S. The Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Quinolone Signal (PQS) Has an Iron-Chelating Activity. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 1318–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggle, S.P.; Matthijs, S.; Wright, V.J.; Fletcher, M.P.; Chhabra, S.R.; Lamont, I.L.; Kong, X.; Hider, R.C.; Cornelis, P.; Cámara, M.; et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-Quinolone Signal Molecules HHQ and PQS Play Multifunctional Roles in Quorum Sensing and Iron Entrapment. Chem. Biol. 2007, 14, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popat, R.; Harrison, F.; Da Silva, A.C.; Easton, S.A.S.; McNally, L.; Williams, P.; Diggle, S.P. Environmental Modification via a Quorum Sensing Molecule Influences the Social Landscape of Siderophore Production. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 284, 20170200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Wu, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Chang, C.; Dong, Y.; Williams, P.; Zhang, L.-H. A Cell-Cell Communication Signal Integrates Quorum Sensing and Stress Response. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Cornelis, P.; Guillemyn, K.; Ballet, S.; Hammerich, O. Structure Revision of N-Mercapto-4-Formylcarbostyril Produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens G308 to 2-(2-Hydroxyphenyl)Thiazole-4-Carbaldehyde [Aeruginaldehyde]. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Peter Greenberg, E. A Network of Networks: Quorum-Sensing Gene Regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 296, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, T.B.; Givskov, M. Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors as Anti-Pathogenic Drugs. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 296, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; German, N.A. Update on Modulators of Quorum Sensing Pathways in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, C.; Cosma, C.L.; Thomas, J.H.; Manoil, C. Lethal Paralysis of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 15202–15207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosson, P.; Zulianello, L.; Join-Lambert, O.; Faurisson, F.; Gebbie, L.; Benghezal, M.; Van Delden, C.; Curty, L.K.; Köhler, T. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence Analyzed in a Dictyostelium discoideum Host System. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 3027–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjarnsholt, T.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Jakobsen, T.H.; Phipps, R.; Nielsen, A.K.; Rybtke, M.T.; Tolker-Nielsen, T.; Givskov, M.; Høiby, N.; Ciofu, O.; et al. Quorum Sensing and Virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during Lung Infection of Cystic Fibrosis Patients. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumbaugh, K.P.; Griswold, J.A.; Iglewski, B.H.; Hamood, A.N. Contribution of Quorum Sensing to the Virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Burn Wound Infections. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 5854–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez-Rifo, A.; Cook, J.; McEwan, D.L.; Shikara, D.; Ausubel, F.M.; Di Cara, F.; Cheng, Z. ABCDs of the Relative Contributions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum Sensing Systems to Virulence in Diverse Nonvertebrate Hosts. mBio 2022, 13, e00417-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rémy, B.; Mion, S.; Plener, L.; Elias, M.; Chabrière, E.; Daudé, D. Interference in Bacterial Quorum Sensing: A Biopharmaceutical Perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekete-Kertész, I.; Berkl, Z.; Buda, K.; Fenyvesi, É.; Szente, L.; Molnár, M. Quorum Quenching Effect of Cyclodextrins on the Pyocyanin and Pyoverdine Production of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliyil, S.; Downham, C.; Broadbent, I.; Charlton, K.; Porter, A.J. High-Sensitivity Monoclonal Antibodies Specific for Homoserine Lactones Protect Mice from Lethal Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, S.W.; Asfahl, K.L.; Dandekar, A.A.; Greenberg, E.P. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum Sensing. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Filloux, A., Ramos, J.-L., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1386, pp. 95–115. ISBN 978-3-031-08490-4. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.N.; Singh, H.B.; Singh, A.; Singh, B.R.; Mishra, A.; Nautiyal, C.S. Lagerstroemia speciosa Fruit Extract Modulates Quorum Sensing-Controlled Virulence Factor Production and Biofilm Formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 2012, 158, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, A.M.; Amer, G.F.; Nabiel, Y. Quinolone-Resistant Uropathogenic E. coli: Is There a Relation between Qnr Genes, gyrA Gene Target Site Mutation and Biofilm Formation? J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Misra, R. Mutational Activation of Antibiotic-Resistant Mechanisms in the Absence of Major Drug Efflux Systems of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2021, 203, e0010921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, B.A.; Zenick, B.; Rocha-Granados, M.C.; Englander, H.E.; Hare, P.J.; LaGree, T.J.; DeMarco, A.M.; Mok, W.W.K. The AcrAB-TolC Efflux Pump Impacts Persistence and Resistance Development in Stationary-Phase Escherichia coli Following Delafloxacin Treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e00281-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.; Nawaz, M.; Park, M.; Chon, J.; Khan, S.A.; Alotaibi, K.; Khan, A.A. Comprehensive Genomic Analysis of Uropathogenic E. coli: Virulence Factors, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Mobile Genetic Elements. Pathogens 2024, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.; Choi, E.; Cho, Y.-J.; Kim, M.J.; Choi, H.W.; Lee, E.-J. A Shared Mechanism of Multidrug Resistance in Laboratory-Evolved Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Virulence 2024, 15, 2367648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, K.; Kaido, M.; Muratani, T.; Yamasaki, E.; Akai, Y.; Kurazono, H.; Yamamoto, S. Multi-drug Resistance Pattern and Genome-wide SNP Detection in Levofloxacin-resistant Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Strains. Int. J. Urol. 2024, 31, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasufuku, T.; Shigemura, K.; Shirakawa, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Nakano, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Arakawa, S.; Kinoshita, S.; Kawabata, M.; Fujisawa, M. Correlation of Overexpression of Efflux Pump Genes with Antibiotic Resistance in Escherichia coli Strains Clinically Isolated from Urinary Tract Infection Patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.; Suhani, S.; Purkaystha, A.; Begum, M.K.; Raihan, T.; Alam, M.J.; Islam, K.; Azad, A.K. Identification of AcrAB-TolC Efflux Pump Genes and Detection of Mutation in Efflux Repressor AcrR from Omeprazole Responsive Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolates Causing Urinary Tract Infections. Microbiol. Insights 2019, 12, 1178636119889629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaikh, S.A.; El-banna, T.; Sonbol, F.; Farghali, M.H. Correlation between Antimicrobial Resistance, Biofilm Formation, and Virulence Determinants in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli from Egyptian Hospital. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2024, 23, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.V.; Dixon, L.; Benoit, M.R.; Brodie, E.L.; Keyhan, M.; Hu, P.; Ackerley, D.F.; Andersen, G.L.; Matin, A. Role of the rapA Gene in Controlling Antibiotic Resistance of Escherichia coli Biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3650–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, T.; Ito, A.; Okabe, S. Induction of Multidrug Resistance Mechanism in Escherichia coli Biofilms by Interplay between Tetracycline and Ampicillin Resistance Genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 4628–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, K.; Furukawa, S.; Ogihara, H.; Morinaga, Y. Roles of Multidrug Efflux Pumps on the Biofilm Formation of Escherichia coli K-12. Biocontrol Sci. 2011, 16, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandio, V.; Torres, A.G.; Kaper, J.B. Quorum Sensing Escherichia coli Regulators B and C (QseBC): A Novel Two-component Regulatory System Involved in the Regulation of Flagella and Motility by Quorum Sensing in E. coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 43, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Barrios, A.F.; Zuo, R.; Hashimoto, Y.; Yang, L.; Bentley, W.E.; Wood, T.K. Autoinducer 2 Controls Biofilm Formation in Escherichia coli through a Novel Motility Quorum-Sensing Regulator (MqsR, B3022). J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmer, B.M.M. Cell-to-cell Signalling in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 52, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauder, S.; Shokat, K.; Surette, M.G.; Bassler, B.L. The LuxS Family of Bacterial Autoinducers: Biosynthesis of a Novel Quorum-sensing Signal Molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 41, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Schauder, S.; Potier, N.; Van Dorsselaer, A.; Pelczer, I.; Bassler, B.L.; Hughson, F.M. Structural Identification of a Bacterial Quorum-Sensing Signal Containing Boron. Nature 2002, 415, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.T.; Xavier, K.B.; Campagna, S.R.; Taga, M.E.; Semmelhack, M.F.; Bassler, B.L.; Hughson, F.M. Salmonella Typhimurium Recognizes a Chemically Distinct Form of the Bacterial Quorum-Sensing Signal AI-2. Mol. Cell 2004, 15, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taga, M.E.; Miller, S.T.; Bassler, B.L. Lsr-mediated Transport and Processing of AI-2 in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 50, 1411–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Attila, C.; Wang, L.; Wood, T.K.; Valdes, J.J.; Bentley, W.E. Quorum Sensing in Escherichia coli Is Signaled by AI-2/LsrR: Effects on Small RNA and Biofilm Architecture. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 6011–6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Wood, T.K. The Primary Physiological Roles of Autoinducer 2 in Escherichia coli Are Chemotaxis and Biofilm Formation. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLisa, M.P.; Valdes, J.J.; Bentley, W.E. Mapping Stress-Induced Changes in Autoinducer AI-2 Production in Chemostat-Cultivated Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 2918–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Hu, H.; Wu, B.; Zhang, X.; Ren, H. Insight into Mature Biofilm Quorum Sensing in Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plants. Chemosphere 2019, 234, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, V.; Meyer, M.T.; Smith, J.A.I.; Gamby, S.; Sintim, H.O.; Ghodssi, R.; Bentley, W.E. AI-2 Analogs and Antibiotics: A Synergistic Approach to Reduce Bacterial Biofilms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 2627–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland-Bräuer, N.; Kisch, M.J.; Pinnow, N.; Liese, A.; Schmitz, R.A. Highly Effective Inhibition of Biofilm Formation by the First Metagenome-Derived AI-2 Quenching Enzyme. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Meng, J.; Huang, Y.; Ye, L.; Li, G.; Huang, J.; Chen, H. The Role of the QseC Quorum-Sensing Sensor Kinase in Epinephrine-Enhanced Motility and Biofilm Formation by Escherichia coli. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 70, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.B.; Hughes, D.T.; Zhu, C.; Boedeker, E.C.; Sperandio, V. The QseC Sensor Kinase: A Bacterial Adrenergic Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10420–10425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, C.G.; Sperandio, V. The Epinephrine/Norepinephrine/Autoinducer-3 Interkingdom Signaling System in Escherichia coli O157:H7. In Microbial Endocrinology: Interkingdom Signaling in Infectious Disease and Health; Lyte, M., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 874, pp. 247–261. ISBN 978-3-319-20214-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Jayaraman, A.; Wood, T.K. Indole Is an Inter-Species Biofilm Signal Mediated by SdiA. BMC Microbiol. 2007, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, N.M.; Allison, K.R.; Khalil, A.S.; Collins, J.J. Signaling-Mediated Bacterial Persister Formation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido, E.; Giraud, E.; Baucheron, S.; Yamasaki, S.; Wiedemann, A.; Okamoto, K.; Takagi, T.; Yamaguchi, A.; Cloeckaert, A.; Nishino, K. Effects of Indole on Drug Resistance and Virulence of Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium Revealed by Genome-Wide Analyses. Gut Pathog. 2012, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domka, J.; Lee, J.; Bansal, T.; Wood, T.K. Temporal Gene-expression in Escherichia coli K-12 Biofilms. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjifrangiskou, M.; Gu, A.P.; Pinkner, J.S.; Kostakioti, M.; Zhang, E.W.; Greene, S.E.; Hultgren, S.J. Transposon Mutagenesis Identifies Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Biofilm Factors. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 6195–6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.M.; Rasko, D.A.; Sperandio, V. Global Effects of the Cell-to-Cell Signaling Molecules Autoinducer-2, Autoinducer-3, and Epinephrine in a luxS Mutant of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 4875–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatova, N.; Abidullina, A.; Streltsova, O.; Elagin, V.; Kamensky, V. Norepinephrine Effects on Uropathogenic Strains Virulence. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henly, E.L.; Norris, K.; Rawson, K.; Zoulias, N.; Jaques, L.; Chirila, P.G.; Parkin, K.L.; Kadirvel, M.; Whiteoak, C.; Lacey, M.M.; et al. Impact of Long-Term Quorum Sensing Inhibition on Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasko, D.A.; Moreira, C.G.; Li, D.R.; Reading, N.C.; Ritchie, J.M.; Waldor, M.K.; Williams, N.; Taussig, R.; Wei, S.; Roth, M.; et al. Targeting QseC Signaling and Virulence for Antibiotic Development. Science 2008, 321, 1078–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, C.G.; Herrera, C.M.; Needham, B.D.; Parker, C.T.; Libby, S.J.; Fang, F.C.; Trent, M.S.; Sperandio, V. Virulence and Stress-Related Periplasmic Protein (VisP) in Bacterial/Host Associations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 1470–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Sims, J.J.; Wood, T.K. Inhibition of Biofilm Formation and Swarming of Escherichia coli by (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(Bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 3, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Bedzyk, L.A.; Ye, R.W.; Thomas, S.M.; Wood, T.K. Differential Gene Expression Shows Natural Brominated Furanones Interfere with the Autoinducer-2 Bacterial Signaling System of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004, 88, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sha, K.; Xu, G.; Tian, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, N. Subinhibitory Concentrations of Allicin Decrease Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) Biofilm Formation, Adhesion Ability, and Swimming Motility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-Muciño, E.; Arenas-Hernández, M.M.P.; Luna-Guevara, M.L. Mechanisms of Inhibition of Quorum Sensing as an Alternative for the Control of E. coli and Salmonella. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pereira, M.O.; Rocha, C.M.R.; Sousa, A.M. Evolving Biofilm Inhibition and Eradication in Clinical Settings through Plant-Based Antibiofilm Agents. Phytomedicine 2023, 119, 154973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er-rahmani, S.; Errabiti, B.; Matencio, A.; Trotta, F.; Latrache, H.; Koraichi, S.I.; Elabed, S. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds for the Inhibition of Biofilm Formation: A Comprehensive Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 34859–34880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; The International Natural Product Sciences Taskforce; Orhan, I.E.; Banach, M.; Rollinger, J.M.; Barreca, D.; Weckwerth, W.; Bauer, R.; et al. Natural Products in Drug Discovery: Advances and Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadybekov, A.V.; Katritch, V. Computational Approaches Streamlining Drug Discovery. Nature 2023, 616, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, S.K.; Mariam, Z. Computer-Aided Drug Design and Drug Discovery: A Prospective Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, R.; Zhang, X.; Liberati, F.R.; Scribani Rossi, C.; Cutruzzolá, F.; Rinaldo, S.; Gaetani, M.; Aínsa, J.A.; Sancho, J. Merging Multi-Omics with Proteome Integral Solubility Alteration Unveils Antibiotic Mode of Action. eLife 2024, 13, RP96343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, S.; Han, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, R.; Yang, X.; Yi, Y. Safety and Efficacy Evaluation of Halicin as an Effective Drug for Inhibiting Intestinal Infections. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1389293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, J.D.; Tatonetti, N.P. Informatics and Computational Methods in Natural Product Drug Discovery: A Review and Perspectives. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Payra, S.; Singh, S.K. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Pharmacological Research: Bridging the Gap Between Data and Drug Discovery. Cureus 2023, 15, e44359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullowney, M.W.; Duncan, K.R.; Elsayed, S.S.; Garg, N.; Van Der Hooft, J.J.J.; Martin, N.I.; Meijer, D.; Terlouw, B.R.; Biermann, F.; Blin, K.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Natural Product Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, F.-L.; Duan, C.-B.; Xu, H.-L.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Sukhbaatar, O.; Gao, J.; Zhang, M.-Z.; Zhang, W.-H.; Gu, Y.-C. AI-Driven Drug Discovery from Natural Products. Adv. Agrochem 2024, 3, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, M.J.; Boursier, M.E.; McEwan, M.A.; Santa, E.E.; Mattmann, M.E.; Slinger, B.L.; Blackwell, H.E. Autoinducer-Fluorophore Conjugates Enable FRET in LuxR Proteins in Vitro and in Cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Luo, Z.-Q.; Smyth, A.J.; Gao, P.; Von Bodman, S.B.; Farrand, S.K. Quorum-Sensing Signal Binding Results in Dimerization of TraR and Its Release from Membranes into the Cytoplasm. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 5212–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakara, M.; Koumandou, V.L. Evolution of Two-Component Quorum Sensing Systems. Access Microbiol. 2022, 4, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology Modelling of Protein Structures and Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, L.A.; Mezulis, S.; Yates, C.M.; Wass, M.N.; Sternberg, M.J.E. The Phyre2 Web Portal for Protein Modeling, Prediction and Analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šali, A.; Blundell, T.L. Comparative Protein Modelling by Satisfaction of Spatial Restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993, 234, 779–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.; DiMaio, F.; Anishchenko, I.; Dauparas, J.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Lee, G.R.; Wang, J.; Cong, Q.; Kinch, L.N.; Schaeffer, R.D.; et al. Accurate Prediction of Protein Structures and Interactions Using a Three-Track Neural Network. Science 2021, 373, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanek, K.A.; Schumacher, M.L.; Mallery, C.P.; Shen, S.; Li, L.; Paczkowski, J.E. Quorum-Sensing Synthase Mutations Re-Calibrate Autoinducer Concentrations in Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to Enhance Pathogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosignoli, S.; Pacelli, M.; Manganiello, F.; Paiardini, A. An Outlook on Structural Biology after A Lpha F Old: Tools, Limits and Perspectives. FEBS Open Bio 2025, 15, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, R.; Wang, J.; Ahern, W.; Sturmfels, P.; Venkatesh, P.; Kalvet, I.; Lee, G.R.; Morey-Burrows, F.S.; Anishchenko, I.; Humphreys, I.R.; et al. Generalized Biomolecular Modeling and Design with RoseTTAFold All-Atom. Science 2024, 384, eadl2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, G.; Juárez, K.; Valderrama, B.; Soberón-Chávez, G. Mechanism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa RhlR Transcriptional Regulation of the rhlAB Promoter. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 5976–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanowski, M.L.; Lostroh, C.P.; Greenberg, E.P. Reversible Acyl-Homoserine Lactone Binding to Purified Vibrio fischeri LuxR Protein. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno, A.; Ojeda-Montes, M.J.; Tomás-Hernández, S.; Cereto-Massagué, A.; Beltrán-Debón, R.; Mulero, M.; Pujadas, G.; Garcia-Vallvé, S. The Light and Dark Sides of Virtual Screening: What Is There to Know? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, U.; Murali, A.; Khan, M.A.; Selvaraj, C.; Singh, S.K. Virtual Screening Process: A Guide in Modern Drug Designing. In Computational Drug Discovery and Design; Gore, M., Jagtap, U.B., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 2714, pp. 21–31. ISBN 978-1-0716-3440-0. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.-Y.; Zhang, H.-X.; Mezei, M.; Cui, M. Molecular Docking: A Powerful Approach for Structure-Based Drug Discovery. Curr. Comput.-Aided Drug Des. 2011, 7, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagadala, N.S.; Syed, K.; Tuszynski, J. Software for Molecular Docking: A Review. Biophys. Rev. 2017, 9, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaieb, K.; Kouidhi, B.; Hosawi, S.B.; Baothman, O.A.S.; Zamzami, M.A.; Altayeb, H.N. Computational Screening of Natural Compounds as Putative Quorum Sensing Inhibitors Targeting Drug Resistance Bacteria: Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 145, 105517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadoq, B.-E.; Boulaamane, Y.; Touati, I.; Britel, M.; Maurady, A. Virtual Screening and Identification of Natural Molecules as Promising Quorum Sensing Inhibitors against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Lett. Appl. NanoBioScience 2025, 14, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamanikandan, S.; Jeyakanthan, J.; Srinivasan, P. Discovery of Potent Inhibitors Targeting Vibrio Harveyi LuxR through Shape and E-Pharmacophore Based Virtual Screening and Its Biological Evaluation. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 103, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Qian, L.; Cao, L.; Tan, H.; Huang, Y.; Xue, X.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, S. Virtual Screening for Novel Quorum Sensing Inhibitors to Eradicate Biofilm Formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 79, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, E.C.; Gschwend, D.A.; Blaney, J.M.; Kuntz, I.D. Orientational Sampling and Rigid-body Minimization in Molecular Docking. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 1993, 17, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S.; Sousa, M.; Martins, F.G.; Simões, M.; Sousa, S.F. Protocol for in Silico Characterization of Natural-Based Molecules as Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors. STAR Protoc. 2024, 5, 103367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Li, J.; Wu, R. Natural Product Databases for Drug Discovery: Features and Applications. Pharm. Sci. Adv. 2024, 2, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokina, M.; Merseburger, P.; Rajan, K.; Yirik, M.A.; Steinbeck, C. COCONUT Online: Collection of Open Natural Products Database. J. Cheminform. 2021, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, K.; Kemmler, E.; Goede, A.; Becker, F.; Dunkel, M.; Preissner, R.; Banerjee, P. SuperNatural 3.0—A Database of Natural Products and Natural Product-Based Derivatives. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D654–D659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoutsis, C.; Fesatidou, M.; Petrou, A.; Geronikaki, A.; Poroikov, V.; Ivanov, M.; Soković, M.; Ćirić, A.; Carazo, A.; Mladěnka, P. Triazolo Based-Thiadiazole Derivatives. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Molecular Docking Studies. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, M.; Singh, P.K.; Yadav, V.K.; Yadav, B.S.; Sharma, D.; Narvi, S.S.; Mani, A.; Agarwal, V. Structure Based Virtual Screening for Identification of Potential Quorum Sensing Inhibitors against LasR Master Regulator in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 107, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, D.A.; Cheatham, T.E.; Darden, T.; Gohlke, H.; Luo, R.; Merz, K.M.; Onufriev, A.; Simmerling, C.; Wang, B.; Woods, R.J. The Amber Biomolecular Simulation Programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1668–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKerell, A.D.; Brooks, B.; Brooks, C.L.; Nilsson, L.; Roux, B.; Won, Y.; Karplus, M. CHARMM: The Energy Function and Its Parameterization. In Encyclopedia of Computational Chemistry; Von Ragué Schleyer, P., Allinger, N.L., Clark, T., Gasteiger, J., Kollman, P.A., Schaefer, H.F., Schreiner, P.R., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-471-96588-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular Dynamics Simulation for All. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, C.; Liu, T.; Yang, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Yang, R.; Cui, Y.; et al. Computer-Aided Rational Engineering of Signal Sensitivity of Quorum Sensing Protein LuxR in a Whole-Cell Biosensor. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 729350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospital, A.; Gelpi, J.; Goñi, R.; Orozco, M. Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Advances and Applications. Adv. Appl. Bioinform. Chem. 2015, 8, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Wen, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Meng, Q.; Yu, F.; Xiao, J.; Li, X. Virtual Screening–Based Discovery of AI-2 Quorum Sensing Inhibitors That Interact with an Allosteric Hydrophobic Site of LsrK and Their Functional Evaluation. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1185224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekarappa, S.B.; Rimac, H.; Lee, J. In Silico Screening of Quorum Sensing Inhibitor Candidates Obtained by Chemical Similarity Search. Molecules 2022, 27, 4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabski, H.; Ginosyan, S.; Tiratsuyan, S. Molecular Simulations and Markov State Modeling Reveal Inactive Form of Quorum Sensing Regulator SdiA of Escherichia coli. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2021, 18, 2835–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Kong, X.; Qu, F.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Q.; Ye, D. Comprehensive Similarity Algorithm and Molecular Dynamics Simulation-Assisted Terahertz Spectroscopy for Intelligent Matching Identification of Quorum Signal Molecules (N-Acyl-Homoserine Lactones). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandve, G.K.; Nekrutenko, A.; Taylor, J.; Hovig, E. Ten Simple Rules for Reproducible Computational Research. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013, 9, e1003285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodden, V.; McNutt, M.; Bailey, D.H.; Deelman, E.; Gil, Y.; Hanson, B.; Heroux, M.A.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Taufer, M. Enhancing Reproducibility for Computational Methods. Science 2016, 354, 1240–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, E.; Agostino, M.; Ramsland, P.A. Challenges and Advances in Computational Docking: 2009 in Review. J. Mol. Recognit. 2011, 24, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, E.; Gilmer, J.; Mayes, H.B.; Mobley, D.L.; Monroe, J.I.; Prasad, S.; Zuckerman, D.M. Best Practices for Foundations in Molecular Simulations [Article v1.0]. Living J. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 1, 5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Theagarajan, R.; Rizqi, M.M.; Nugraha, A.S.; Boruah, T.; Pratiksha; Kumar, H.; Naik, B.; Yadav, S.; Jha, A.K.; et al. AI-Enabled Drug and Molecular Discovery: Computational Methods, Platforms, and Translational Horizons. Discov. Mol. 2025, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.M.; Mohammad, K.A.; Almalki, M.; Abulnaja, K.O.; Ibrahim, S.R.M. Integrative Experimental and Computational Dataset for Repurposed Antibiofilm Drug Candidates Targeting Quorum Sensing. Data Brief 2025, 62, 112025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Zhou, K.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X.; Fan, J.; Hou, D.; Li, X.; et al. NPASS Database Update 2023: Quantitative Natural Product Activity and Species Source Database for Biomedical Research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D621–D628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, C.; Chen, T.; Qiang, B.; Liu, N.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z. CMNPD: A Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database towards Facilitating Drug Discovery from the Ocean. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D509–D515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, A.; Jiménez, D.A.A.; Zamora, W.J.; Barazorda-Ccahuana, H.L.; Chávez-Fumagalli, M.Á.; Valli, M.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Bolzani, V.D.S.; Olmedo, D.A.; Solís, P.N.; et al. Navigating the Chemical Space and Chemical Multiverse of a Unified Latin American Natural Product Database: LANaPDB. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynton, E.F.; van Santen, J.A.; Pin, M.; Contreras, M.M.; McMann, E.; Parra, J.; Showalter, B.; Zaroubi, L.; Duncan, K.R.; Linington, R.G. The Natural Products Atlas 3.0: Extending the Database of Microbially Derived Natural Products. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D691–D699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Ding, F.; Wang, R.; Shen, R.; Zhang, X.; Luo, S.; Su, C.; Wu, Z.; Xie, Q.; Berger, B.; et al. High-Resolution de Novo Structure Prediction from Primary Sequence. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Akin, H.; Rao, R.; Hie, B.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, W.; Smetanin, N.; Verkuil, R.; Kabeli, O.; Shmueli, Y.; et al. Evolutionary-Scale Prediction of Atomic-Level Protein Structure with a Language Model. Science 2023, 379, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Yadollahpour, P.; Watkins, A.; Frey, N.C.; Leaver-Fay, A.; Ra, S.; Cho, K.; Gligorijević, V.; Regev, A.; Bonneau, R. EquiFold: Protein Structure Prediction with a Novel Coarse-Grained Structure Representation. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlwend, J.; Corso, G.; Passaro, S.; Getz, N.; Reveiz, M.; Leidal, K.; Swiderski, W.; Atkinson, L.; Portnoi, T.; Chinn, I.; et al. Boltz-1 Democratizing Biomolecular Interaction Modeling. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making Protein Folding Accessible to All. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunseri, J.; Koes, D.R. Pharmit: Interactive Exploration of Chemical Space. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W442–W448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koes, D.R.; Camacho, C.J. ZINCPharmer: Pharmacophore Search of the ZINC Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W409–W414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.L.; Smondyrev, A.M.; Knoll, E.H.; Rao, S.N.; Shaw, D.E.; Friesner, R.A. PHASE: A New Engine for Pharmacophore Perception, 3D QSAR Model Development, and 3D Database Screening: 1. Methodology and Preliminary Results. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2006, 20, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolber, G.; Langer, T. LigandScout: 3-D Pharmacophores Derived from Protein-Bound Ligands and Their Use as Virtual Screening Filters. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koes, D.R.; Baumgartner, M.P.; Camacho, C.J. Lessons Learned in Empirical Scoring with Smina from the CSAR 2011 Benchmarking Exercise. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 1893–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosdidier, A.; Zoete, V.; Michielin, O. SwissDock, a Protein-Small Molecule Docking Web Service Based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W270–W277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korb, O.; Stützle, T.; Exner, T.E. Empirical Scoring Functions for Advanced Protein−Ligand Docking with PLANTS. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Carmona, S.; Alvarez-Garcia, D.; Foloppe, N.; Garmendia-Doval, A.B.; Juhos, S.; Schmidtke, P.; Barril, X.; Hubbard, R.E.; Morley, S.D. rDock: A Fast, Versatile and Open Source Program for Docking Ligands to Proteins and Nucleic Acids. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNutt, A.T.; Francoeur, P.; Aggarwal, R.; Masuda, T.; Meli, R.; Ragoza, M.; Sunseri, J.; Koes, D.R. GNINA 1.0: Molecular Docking with Deep Learning. J. Cheminform. 2021, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Willett, P.; Glen, R.C.; Leach, A.R.; Taylor, R. Development and Validation of a Genetic Algorithm for Flexible Docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, R.; Christensen, M.H. MolDock: A New Technique for High-Accuracy Molecular Docking. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 3315–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, B.; Rarey, M.; Lengauer, T. Evaluation of the FLEXX Incremental Construction Algorithm for Protein-Ligand Docking. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 1999, 37, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, P.; Swails, J.; Chodera, J.D.; McGibbon, R.T.; Zhao, Y.; Beauchamp, K.A.; Wang, L.-P.; Simmonett, A.C.; Harrigan, M.P.; Stern, C.D.; et al. OpenMM 7: Rapid Development of High Performance Algorithms for Molecular Dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.C.; Braun, R.; Wang, W.; Gumbart, J.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Villa, E.; Chipot, C.; Skeel, R.D.; Kalé, L.; Schulten, K. Scalable Molecular Dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1781–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A Web-based Graphical User Interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Aktulga, H.M.; Belfon, K.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cisneros, G.A.; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; Forouzesh, N.; Giese, T.J.; Götz, A.W.; Gohlke, H.; et al. AmberTools. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 6183–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tewari, D.; Hohmann, J.; Kiss, A.K.; Rollinger, J.M.; Atanasov, A.G. Editorial: Ethnopharmacology in Central and Eastern Europe in the Context of Global Research Developments. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Shi, M.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Tong, C.; Cao, G.; Shou, D. Natural Phytochemical-Based Strategies for Antibiofilm Applications. Chin. Med. 2025, 20, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, S.A.; Julaeha, E.; Kagawa, N.; Kurnia, D. The Potential of Secondary Metabolites in Medicinal Plants as Anti–Quorum Sensing in Biofilms: A Comprehensive Review. J. Chem. 2025, 2025, 8838140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.H.; Yeo, Y.P.; Hafiz, M.; Ng, N.K.J.; Subramoni, S.; Taj, S.; Tay, M.; Chao, X.; Kjelleberg, S.; Rice, S.A. Functional Metagenomic Analysis of Quorum Sensing Signaling in a Nitrifying Community. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitwell, C.; Indra, S.S.; Luke, C.; Kakoma, M.K. A Review of Modern and Conventional Extraction Techniques and Their Applications for Extracting Phytochemicals from Plants. Sci. Afr. 2023, 19, e01585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Waltenberger, B.; Pferschy-Wenzig, E.-M.; Linder, T.; Wawrosch, C.; Uhrin, P.; Temml, V.; Wang, L.; Schwaiger, S.; Heiss, E.H.; et al. Discovery and Resupply of Pharmacologically Active Plant-Derived Natural Products: A Review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1582–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, N.; Sandeep, I.S.; Mohanty, S. Plant-Derived Natural Products for Drug Discovery: Current Approaches and Prospects. Nucleus 2022, 65, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, A.; Javed, S.A.; Al Bratty, M.; Alhazmi, H.A. Modern Approaches in the Discovery and Development of Plant-Based Natural Products and Their Analogues as Potential Therapeutic Agents. Molecules 2022, 27, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenlehner, F. Novel Antibiotics for Urinary Tract Infection (UTI): The EAGLE 2 and EAGLE-3 Trials for Uncomplicated UTI, and the CERTAIN-1 Trial for Complicated UTI. Eur. Urol. Focus 2024, 10, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naber, K.G.; Alidjanov, J.F.; Fünfstück, R.; Strohmaier, W.L.; Kranz, J.; Cai, T.; Pilatz, A.; Wagenlehner, F.M. Therapeutic Strategies for Uncomplicated Cystitis in Women. GMS Infect. Dis. 2024, 12, Doc01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynendaele, E.; Furman, C.; Wielgomas, B.; Larsson, P.; Hak, E.; Block, T.; Van Calenbergh, S.; Willand, N.; Markuszewski, M.; Odell, L.R.; et al. Sustainability in Drug Discovery. Med. Drug Discov. 2021, 12, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politeo, O.; Skocibusic, M.; Carev, I.; Burcul, F.; Jerkovic, I.; Sarolic, M.; Milos, M. Phytochemical Profiles of Volatile Constituents from Centaurea ragusina Leaves and Flowers and Their Antimicrobial Effects. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 1087–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politeo, O.; Skocibusic, M.; Burcul, F.; Maravic, A.; Carev, I.; Ruscic, M.; Milos, M. Campanula portenschlagiana Roem. et Schult.: Chemical and Antimicrobial Activities. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politeo, O.; Maravić, A.; Burčul, F.; Carev, I.; Kamenjarin, J. Phytochemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils of Wild Growing Cistus Species in Croatia. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1934578X1801300631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carev, I.; Ruščić, M.; Skočibušić, M.; Maravić, A.; Siljak-Yakovlev, S.; Politeo, O. Phytochemical and Cytogenetic Characterization of Centaurea solstitialis L. (Asteraceae) from Croatia. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1600213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carev, I.; Maravić, A.; Bektašević, M.; Ruščić, M.; Siljak-Yakovlev, S.; Politeo, O. Centaurea Rupestris L.: Cytogenetics, Essential Oil Chemistry and Biological Activity. Croat. Chem. Acta 2018, 91, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carev, I.; Maravić, A.; Ilić, N.; Čikeš Čulić, V.; Politeo, O.; Zorić, Z.; Radan, M. UPLC-MS/MS Phytochemical Analysis of Two Croatian Cistus Species and Their Biological Activity. Life 2020, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-W.; Lin, L.-G.; Ye, W.-C. Techniques for Extraction and Isolation of Natural Products: A Comprehensive Review. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jažo, Z.; Glumac, M.; Paštar, V.; Bektić, S.; Radan, M.; Carev, I. Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Salvia officinalis L. Essential Oil. Plants 2023, 12, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glumac, M.; Jažo, Z.; Paštar, V.; Golemac, A.; Čikeš Čulić, V.; Bektić, S.; Radan, M.; Carev, I. Chemical Profiling and Bioactivity Assessment of Helichrysum italicum (Roth) G. Don. Essential Oil: Exploring Pure Compounds and Synergistic Combinations. Molecules 2023, 28, 5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, J.; Azevedo, N.F.; Briandet, R.; Cerca, N.; Coenye, T.; Costa, A.R.; Desvaux, M.; Di Bonaventura, G.; Hébraud, M.; Jaglic, Z.; et al. Critical Review on Biofilm Methods. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 43, 313–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, E.; Nelis, H.J.; Coenye, T. Comparison of Multiple Methods for Quantification of Microbial Biofilms Grown in Microtiter Plates. J. Microbiol. Methods 2008, 72, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V.C. Quorum Sensing Inhibitors: An Overview. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoogstraten, S.W.G.; Kuik, C.; Arts, J.J.C.; Cillero-Pastor, B. Molecular Imaging of Bacterial Biofilms—A Systematic Review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 50, 971–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alum, E.U.; Gulumbe, B.H.; Izah, S.C.; Uti, D.E.; Aja, P.M.; Igwenyi, I.O.; Offor, C.E. Natural Product-Based Inhibitors of Quorum Sensing: A Novel Approach to Combat Antibiotic Resistance. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 43, 102111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadakkan, K.; Sathishkumar, K.; Mapranathukaran, V.O.; Ngangbam, A.K.; Nongmaithem, B.D.; Hemapriya, J.; Nair, J.B. Critical Review on Plant-Derived Quorum Sensing Signaling Inhibitors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Bioorganic Chem. 2024, 151, 107649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, T.; Saravanan, H.; David, H.; Solanke, J.; Rajaramon, S.; Dandela, R.; Solomon, A.P. Bioorganic Compounds in Quorum Sensing Disruption: Strategies, Mechanisms, and Future Prospects. Bioorganic Chem. 2025, 156, 108192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Dong, B.; Wang, K.; Cai, S.; Liu, T.; Cheng, X.; Lei, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Kong, J.; et al. Baicalin Inhibits Biofilm Formation, Attenuates the Quorum Sensing-Controlled Virulence and Enhances Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clearance in a Mouse Peritoneal Implant Infection Model. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczkowski, J.E.; Mukherjee, S.; McCready, A.R.; Cong, J.-P.; Aquino, C.J.; Kim, H.; Henke, B.R.; Smith, C.D.; Bassler, B.L. Flavonoids Suppress Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence through Allosteric Inhibition of Quorum-Sensing Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 4064–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, F.; Ji, B.-P.; Pei, R.-S.; Xu, N. The Antibacterial Mechanism of Carvacrol and Thymol against Escherichia coli. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 47, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, M.; Yadav, V.K.; Singh, P.K.; Sharma, D.; Narvi, S.S.; Agarwal, V. Exploring the Impact of Parthenolide as Anti-Quorum Sensing and Anti-Biofilm Agent against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Life Sci. 2018, 199, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-W.; Luo, H.-Z.; Jiang, H.; Jian, T.-K.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Jia, A.-Q. Hordenine: A Novel Quorum Sensing Inhibitor and Antibiofilm Agent against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 1620–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norizan, S.; Yin, W.-F.; Chan, K.-G. Caffeine as a Potential Quorum Sensing Inhibitor. Sensors 2013, 13, 5117–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sawy, E.R.; Abdel-Aziz, M.S.; Abdelmegeed, H.; Kirsch, G. Coumarins: Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation Inhibition. Molecules 2024, 29, 4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Luo, H.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Z.; Jia, A. Inhibition of Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation of Esculetin on Aeromonas hydrophila. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 737626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Bhatia, S. Quorum Sensing Inhibitors: Curbing Pathogenic Infections through Inhibition of Bacterial Communication. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 20, 486–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Zhang, L. The Hierarchy Quorum Sensing Network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Cell 2015, 6, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Diéguez, L.; Diaz-Tang, G.; Marin Meneses, E.; Cruise, V.; Barraza, I.; Craddock, T.J.A.; Smith, R.P. Periodically Disturbing Biofilms Reduces Expression of Quorum Sensing-Regulated Virulence Factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. iScience 2023, 26, 106843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhou, X.; On behalf of China Critical Care Clinical Trials Group (CCCCTG) and China National Critical Care Quality Control Center Group (China-NCCQC group). Data-Driven Spatial–Temporal Framework for Exploring the Heterogeneity and Temporality of Sepsis. Chin. Med. J. 2026, 139, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyżek, P. Challenges and Limitations of Anti-Quorum Sensing Therapies. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Tools | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Compounds Databases | COCONUT—Collection of Open Natural Products [189], SuperNatural 3.0 [190], NPASS—Natural Product Activity and Species Source [209], CMNPD—Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database [210]; Latin American Natural Product Database LANaPDB) [211], The Natural Products Atlas 3.0 [212] | Collection of Natural Products and Databases |

| Protein Structure Prediction—Homology-based | SwissModel [167], Phyre [168], MODELLER [169] | Template-based structure prediction |

| Protein Structure Prediction—Ab-initio | AlphaFold 2 [170], RoseTTAFold [171], OmegaFold [213], ESMFold [214], EquiFold [215] | Deep learning-based structure prediction |

| Protein Complexes Prediction | AlphaFold 3 [174], RosettaFold-All-Atoms [175], Boltz-1 [216], ColabFold [217] | Multi-protein complex modeling |

| Virtual Screening— Pharmacophore Modelling | Pharmit [218], ZINCPharmer [219], PHASE [220], LigandScout [221] | Pharmacophore-based screening |

| Virtual Screening—Molecular Docking | AutoDock4 [222], AutoDock Vina [223], Smina [224], SwissDock [225], PLANTS [226], rDock [227], Gnina [228], GOLD [229], Molegro [230], Glide [231], FlexX [232]. | Docking-Based Screening |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS [196], OpenMM [233], NAMD [234], CHARMM-GUI [235], AmberTools [236] | MD simulation software |

| Pathogen | QS System/Target | Representative Natural Compounds | Computational Approaches | Experimental Validation | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | LasR (3OC12-HSL receptor) | Flavonoids (e.g., Baicalein, Quercetin, Naringenin, Rutin, Catechin) | Molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, virtual screening | QS reporter assays; elastase and pyocyanin quantification; biofilm inhibition (crystal violet); CLSM | [182,185,186,187,259,264,265] |

| P. aeruginosa | RhlR (C4-HSL receptor) | Terpenoids, cinnamic acid derivatives | Structure-based virtual screening; molecular docking; binding energy calculations | Rhamnolipid production; swarming motility; biofilm formation assays | [184,266,267] |

| P. aeruginosa | PqsR (MvfR)/ PQS pathway | Alkyl quinones; plant-derived phenolic compounds | Structure-based docking, QSAR modeling | virulence factor assays; biofilm analysis | [184] |

| P. aeruginosa | LasI/RhlI (autoinducer synthases) | Fatty acid derivatives; plant secondary metabolites | Molecular docking | Autoinducer quantification; QS gene expression analysis | [262,267,268] |

| UPEC | LuxS/AI-2 system | Coumarins, flavonoids, cinnamic acid derivatives | Molecular docking | AI-2 bioluminescence assays; biofilm formation assays | [252,253,259] |

| UPEC | QseC (sensor kinase) | Indole derivatives, phenolic compounds | Molecular docking; network-based analysis | Motility assays; QS-regulated gene expression analysis | [249,269] |

| UPEC | Indole signaling (TnaA) | Indole analogues, plant-derived aromatics | Molecular docking; molecular interaction analysis | Biofilm assays; antibiotic tolerance tests | [269,270,271] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rosignoli, S.; Lustrino, E.; Shevchuk, O.; Rinaldo, S.; Rubini, E.; Paiardini, A.; Carev, I. Bioinformatics-Driven, Plant-Based Antibiotic Research Against Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli Multiresistant Microbes. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020197

Rosignoli S, Lustrino E, Shevchuk O, Rinaldo S, Rubini E, Paiardini A, Carev I. Bioinformatics-Driven, Plant-Based Antibiotic Research Against Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli Multiresistant Microbes. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(2):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020197

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosignoli, Serena, Elisa Lustrino, Olga Shevchuk, Serena Rinaldo, Elisabetta Rubini, Alessandro Paiardini, and Ivana Carev. 2026. "Bioinformatics-Driven, Plant-Based Antibiotic Research Against Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli Multiresistant Microbes" Biomolecules 16, no. 2: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020197

APA StyleRosignoli, S., Lustrino, E., Shevchuk, O., Rinaldo, S., Rubini, E., Paiardini, A., & Carev, I. (2026). Bioinformatics-Driven, Plant-Based Antibiotic Research Against Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli Multiresistant Microbes. Biomolecules, 16(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020197