Resistance Exercise Counteracts Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in T2DM Mice by Upregulating FGF21 and Activating PI3K/Akt Pathway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Establishment of Mice Model of T2DM

2.2. Exercise Protocol

2.3. Glucose and Insulin Tolerance Tests

2.4. Body Composition

2.5. Animal Sampling and Treatment

2.6. Serum Biochemical Analysis

2.7. Hematoxylin-Eosin and Sirius Red Staining

2.8. Protein Extraction and Western Blotting

2.9. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

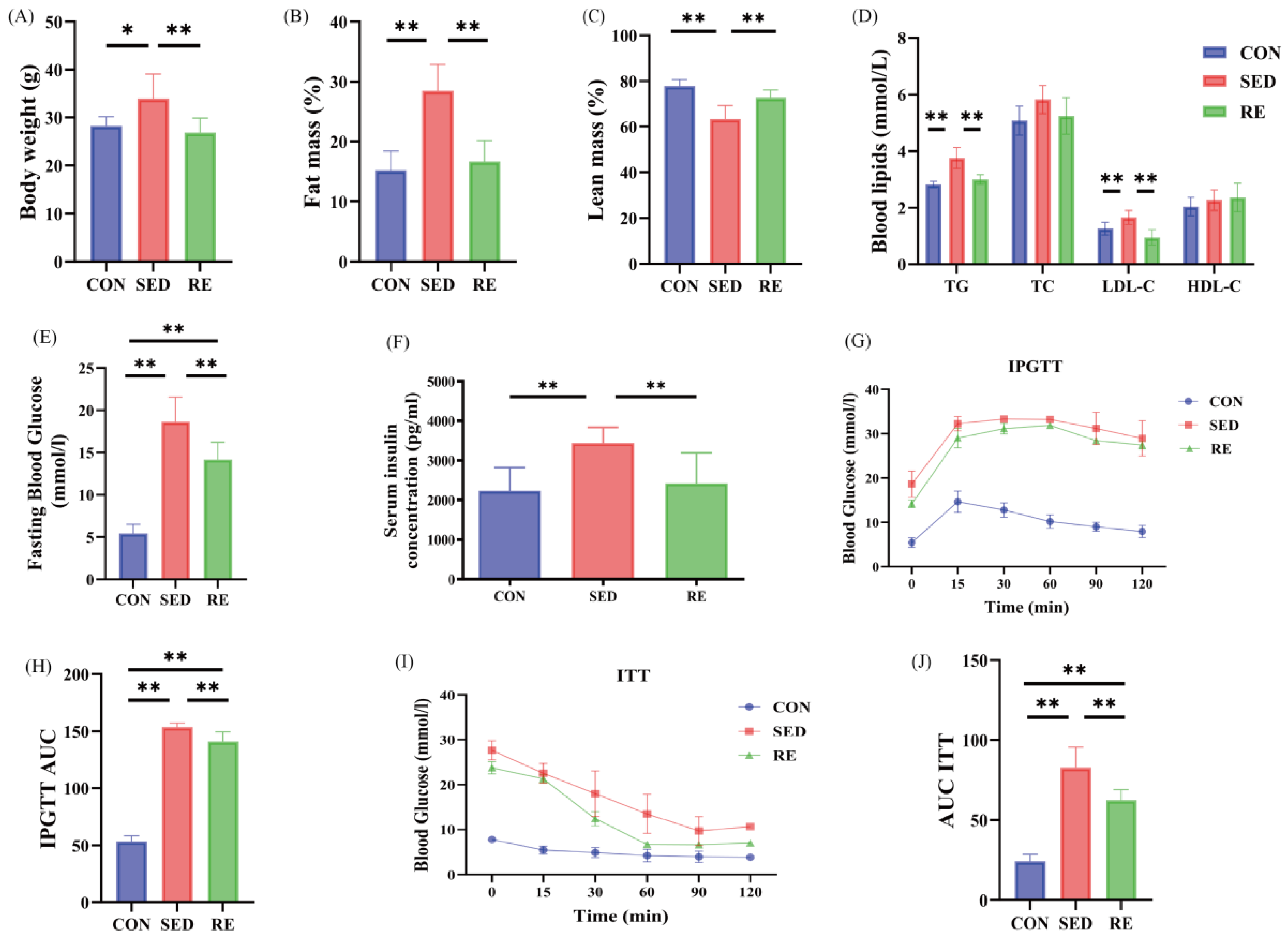

3.1. RE Improves Body Composition and Metabolic Indexes of T2DM Mice

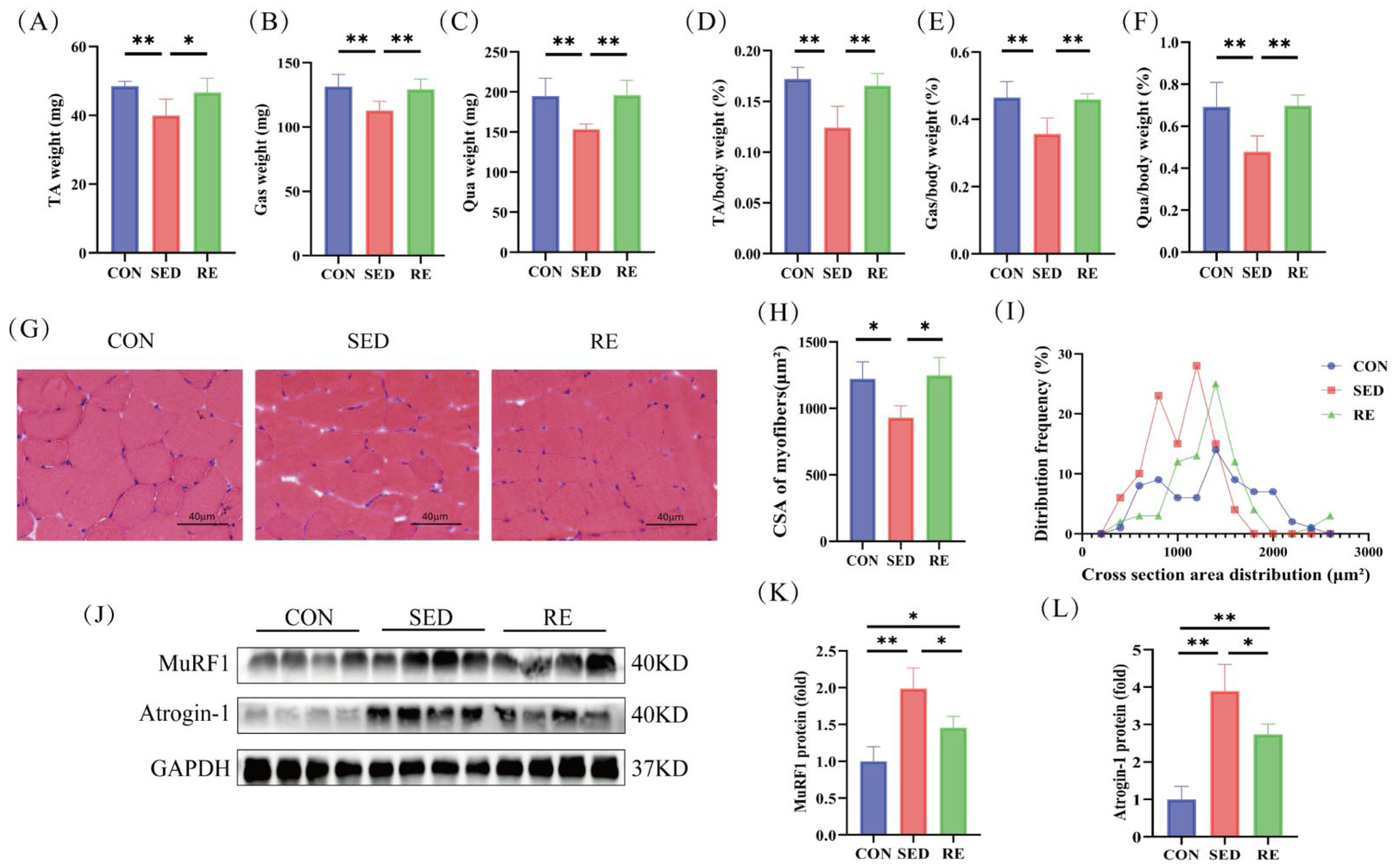

3.2. RE Counteracts Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in T2DM Mice

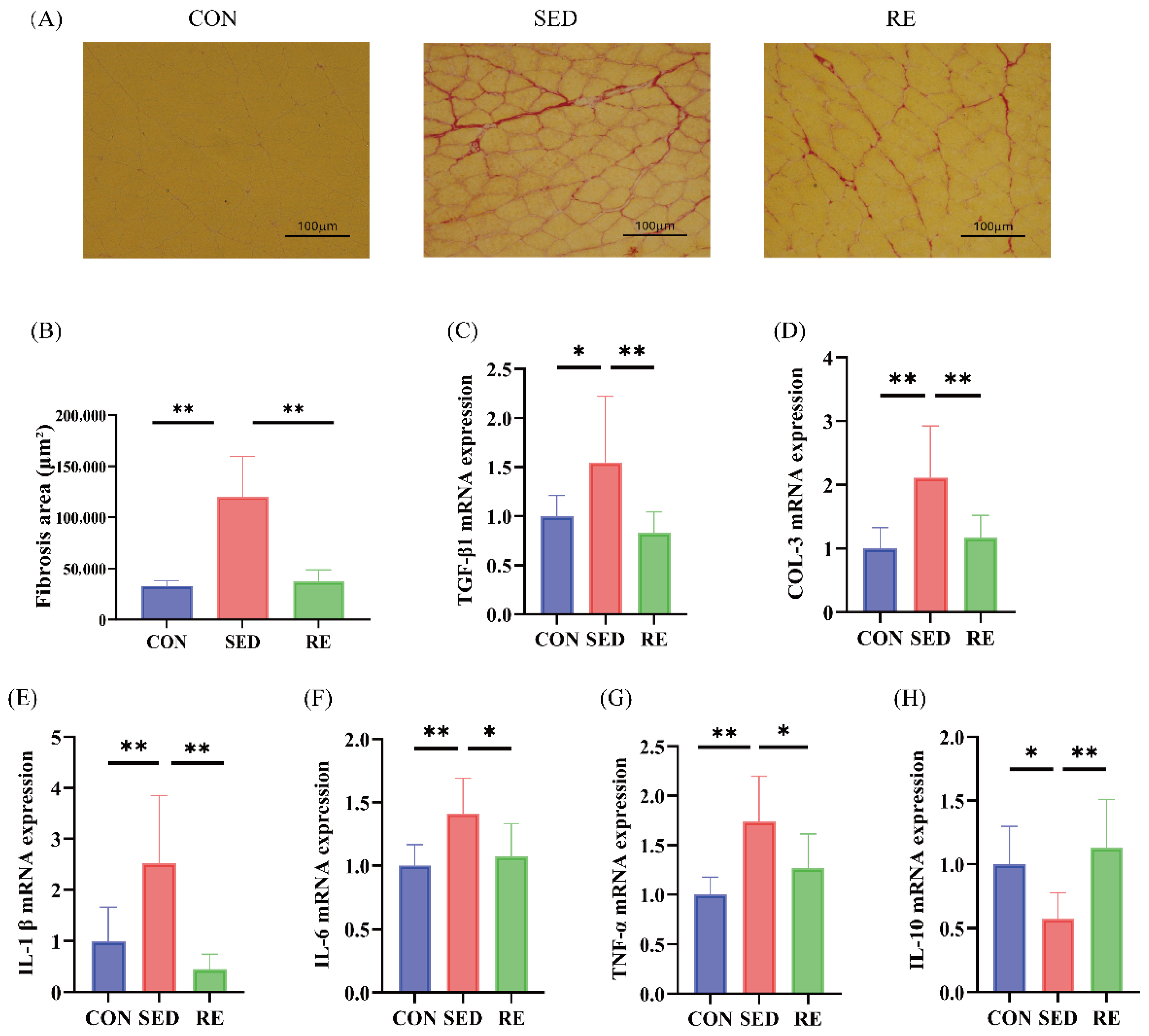

3.3. RE Alleviates Fibrosis and Inflammation of Skeletal Muscle in T2DM Mice

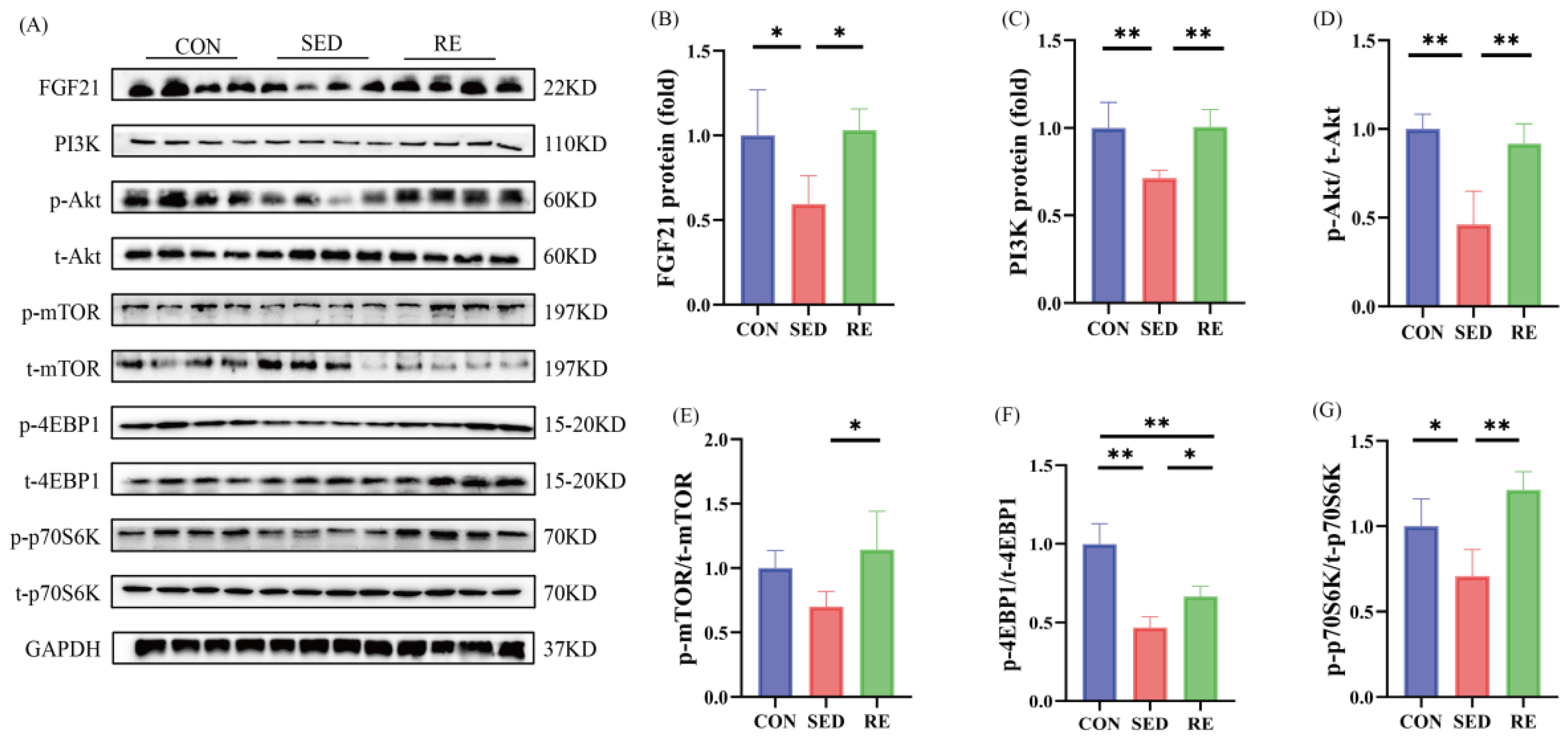

3.4. RE Activates FGF21/PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway and Promotes Skeletal Muscle Protein Synthesis in T2DM Mice

3.5. RE Improves Glycolipid Metabolism Disorder in Skeletal Muscle of T2DM Mice

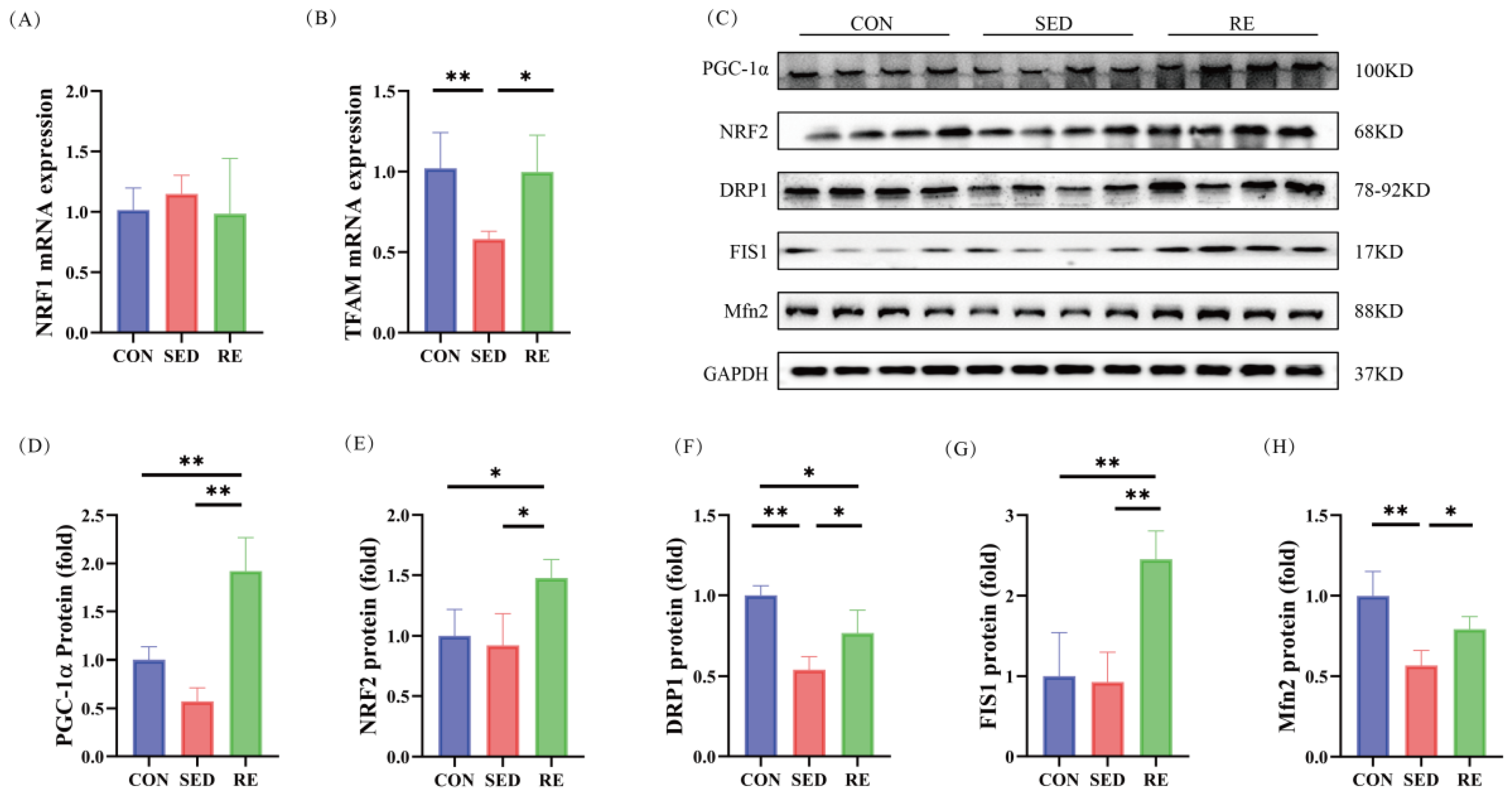

3.6. RE Improves Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Dynamics in Skeletal Muscle of T2DM Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, K.E.; Thurmond, D.C. Role of Skeletal Muscle in Insulin Resistance and Glucose Uptake. Compr. Physiol. 2020, 10, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, G.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Imaging of Sarcopenia in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Clin. Interv. Aging 2024, 19, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, E.; Morley, J.E.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Arai, H.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Guralnik, J.; Bauer, J.M.; Pahor, M.; Clark, B.C.; Cesari, M.; et al. International Clinical Practice Guidelines for Sarcopenia (ICFSR): Screening, Diagnosis and Management. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, Í.M.P.; Argilés, J.M.; Rueda, R.; Ramírez, M.; Pedrosa, J.M.L. Skeletal muscle atrophy and dysfunction in obesity and type-2 diabetes mellitus: Myocellular mechanisms involved. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2025, 26, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Pedrosa, J.M.; Camprubi-Robles, M.; Guzman-Rolo, G.; Lopez-Gonzalez, A.; Garcia-Almeida, J.M.; Sanz-Paris, A.; Rueda, R. The Vicious Cycle of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Skeletal Muscle Atrophy: Clinical, Biochemical, and Nutritional Bases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S.H.; Hu, F.B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Coletta, D.K. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Insights from skeletal muscle extracellular matrix remodeling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2025, 328, C1752–C1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, S.M.; Al-Zougbi, A.; Bodine, S.C.; Adams, C.M. Skeletal Muscle Atrophy: Discovery of Mechanisms and Potential Therapies. Physiology 2019, 34, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Li, B.; Xi, Y.; Cai, M.; Tian, Z. Aerobic exercise and resistance exercise alleviate skeletal muscle atrophy through IGF-1/IGF-1R-PI3K/Akt pathway in mice with myocardial infarction. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022, 322, C164–C176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst, C.; Robinson, S.M.; Witham, M.D.; Dodds, R.M.; Granic, A.; Buckland, C.; De Biase, S.; Finnegan, S.; Rochester, L.; Skelton, D.A.; et al. Resistance exercise as a treatment for sarcopenia: Prescription and delivery. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhai, X.; Sheng, X.; Quan, H.; Lin, H. Exercise mitigates Dapagliflozin-induced skeletal muscle atrophy in STZ-induced diabetic rats. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ato, S.; Kido, K.; Sato, K.; Fujita, S. Type 2 diabetes causes skeletal muscle atrophy but does not impair resistance training-mediated myonuclear accretion and muscle mass gain in rats. Exp. Physiol. 2019, 104, 1518–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, P.; Saikia, B.B.; Sonnaila, S.; Agrawal, S.; Alraawi, Z.; Kumar, T.K.S.; Iyer, S. The Saga of Endocrine FGFs. Cells 2021, 10, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Huang, S.; Zheng, F.; Liu, Y. The CEBPA-FGF21 regulatory network may participate in the T2DM-induced skeletal muscle atrophy by regulating the autophagy-lysosomal pathway. Acta Diabetol. 2023, 60, 1491–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S.; Joe, Y.; Choi, H.S.; Back, S.H.; Park, J.W.; Chung, H.T.; Roh, E.; Kim, M.S.; Ha, T.Y.; Yu, R. Deficiency of fibroblast growth factor 21 aggravates obesity-induced atrophic responses in skeletal muscle. J. Inflamm. 2019, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwon, H.J.; Cho, W.; Choi, S.W.; Lim, D.S.; Tanriverdi, E.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Jeong, J.H.; Jung, T.W. Donepezil improves skeletal muscle insulin resistance in obese mice via the AMPK/FGF21-mediated suppression of inflammation and ferroptosis. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2024, 47, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Sun, X.; Lin, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Z.; Liu, P.; Liu, Z.; Huang, H. Gentiopicroside targets PAQR3 to activate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and ameliorate disordered glucose and lipid metabolism. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 2887–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Zhang, C.; Yang, J.; Tian, Y.; You, L.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Pan, D.; Liu, Z. Kaempferol Improves Exercise Performance by Regulating Glucose Uptake, Mitochondrial Biogenesis, and Protein Synthesis via PI3K/AKT and MAPK Signaling Pathways. Foods 2024, 13, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Xu, D.; Yu, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Lapatinib induces mitochondrial dysfunction to enhance oxidative stress and ferroptosis in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocytes via inhibition of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Tian, G.; Liu, X.; Gui, C.; Xu, L. Down-Regulation of miR-138 Alleviates Inflammatory Response and Promotes Wound Healing in Diabetic Foot Ulcer Rats via Activating PI3K/AKT Pathway and hTERT. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2022, 15, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Fu, R.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, K.; Xiao, Q. Irisin ameliorates D-galactose-induced skeletal muscle fibrosis via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 939, 175476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Rao, Z.; Wu, J.; Ma, X.; Jiang, Z.; Xiao, W. Resistance Exercise Improves Glycolipid Metabolism and Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Skeletal Muscle of T2DM Mice via miR-30d-5p/SIRT1/PGC-1α Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.B.; Liang, H.; Zhan, P.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, Q.X.; Zheng, Z.J.; Lu, H.X.; Shang, G.K.; Ji, X.P. Stimulator of interferon genes promotes diabetic sarcopenia by targeting peroxisome proliferator activated receptors γ degradation and inhibiting fatty acid oxidation. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 2623–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tezze, C.; Romanello, V.; Sandri, M. FGF21 as Modulator of Metabolism in Health and Disease. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilis, P.; Oikonomou, E.; Karakasis, P.; Pamporis, K.; Dimitriadis, K.; Kokkou, E.; Lambadiari, V.; Siasos, G.; Tsioufis, K.; Tousoulis, D. FGF21 Analogues in Patients With Metabolic Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Liver Int. 2025, 45, e70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Hu, W.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, F.; Mao, X.; Yang, G.; Li, L. FGF21 facilitates autophagy in prostate cancer cells by inhibiting the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, S.; Xiong, J.; Hu, F.; Liang, X.; Ye, X. Fibroblast growth factor 21 alleviates idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling and stimulating autophagy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 132896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, D.; Chen, P.; Xiao, W. HIIT Promotes M2 Macrophage Polarization and Sympathetic Nerve Density to Induce Adipose Tissue Browning in T2DM Mice. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Ma, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xiao, W. The Effects of Different Types of Exercise on Pulmonary Inflammation and Fibrosis in Mice with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cells 2025, 14, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabzadeh, E.; Rahimi, A.; Zargani, M.; Feyz Simorghi, Z.; Emami, S.; Sheikhi, S.; Zaeri Amirani, Z.; Yousefi, P.; Sarshin, A.; Aghaei, F.; et al. Resistance exercise promotes functional test via sciatic nerve regeneration, and muscle atrophy improvement through GAP-43 regulation in animal model of traumatic nerve injuries. Neurosci. Lett. 2022, 787, 136812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Quan, H.; Li, W.; Li, T.; Wang, L. Resistance training alleviates muscle atrophy and muscle dysfunction by reducing inflammation and regulating compromised autophagy in aged skeletal muscle. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1597222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Jin, Y.; He, J.; Jia, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y. Extracellular matrix in skeletal muscle injury and atrophy: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. J. Orthop. Translat 2025, 52, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, M.Y.; Shoelson, S.E. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Bai, F.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Zou, D.; Qu, S.; Tian, G.; Song, L.; Zhang, T.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF21) protects mouse liver against D-galactose-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis via activating Nrf2 and PI3K/Akt pathways. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2015, 403, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Huang, J.; Wen, M.; Zhang, X.; Lyu, D.; Li, S.; Xiao, H.; Li, M.; Shen, C.; Huang, H. Gentiopicroside ameliorates glucose and lipid metabolism in T2DM via targeting FGFR1. Phytomedicine 2024, 132, 155780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Choi, M.J.; So, B.; Kim, H.J.; Seong, J.K.; Song, W. The Preventive Effects of 8 Weeks of Resistance Training on Glucose Tolerance and Muscle Fiber Type Composition in Zucker Rats. Diabetes Metab. J. 2015, 39, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Kim, C. Resistance Training for Glycemic Control, Muscular Strength, and Lean Body Mass in Old Type 2 Diabetic Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2017, 8, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenami, E.; Iwamoto, S.; Shiraishi, N.; Kato, A.; Watanabe, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Yamada, S.; Ishii, N. Effects of low-intensity resistance training on muscular function and glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Investig. 2019, 10, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, T.; Lin, M.H.; Kim, K. Intensity Differences of Resistance Training for Type 2 Diabetic Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, M.; Gu, L.; Zeng, Y.; Gao, W.; Cai, C.; Chen, Y.; Guo, X. The efficacy of resistance exercise training on metabolic health, body composition, and muscle strength in older adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 222, 112079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesinovic, J.; Zengin, A.; De Courten, B.; Ebeling, P.R.; Scott, D. Sarcopenia and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A bidirectional relationship. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2019, 12, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambelu, T.; Teferi, G. The impact of exercise modalities on blood glucose, blood pressure and body composition in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 15, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Manzano, P.; Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Acosta, F.M.; Niederseer, D.; Niebauer, J. Beyond general resistance training. Hypertrophy versus muscular endurance training as therapeutic interventions in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, J.; Cui, C.; Hu, H.; Zang, N.; Yang, M.; Yang, J.; Zou, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorate diabetes-induced muscle atrophy through exosomes by enhancing AMPK/ULK1-mediated autophagy. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Singh, A.; Phogat, J.; Dahuja, A.; Dabur, R. Magnoflorine prevent the skeletal muscle atrophy via Akt/mTOR/FoxO signal pathway and increase slow-MyHC production in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 267, 113510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J.; Garofolini, A.; Orazem, J.; Sabol, F.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Pedisic, Z. Effects of Resistance Training on Muscle Size and Strength in Very Elderly Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1983–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmati, M.; Shariatzadeh Joneydi, M.; Koyanagi, A.; Yang, G.; Ji, B.; Won Lee, S.; Keon Yon, D.; Smith, L.; Il Shin, J.; Li, Y. Resistance training restores skeletal muscle atrophy and satellite cell content in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portilla-Cueto, K.; Medina-Pérez, C.; Romero-Pérez, E.M.; Hernández-Murúa, J.A.; Vila-Chã, C.; de Paz, J.A. Reliability of Isometric Muscle Strength Measurement and Its Accuracy Prediction of Maximal Dynamic Force in People with Multiple Sclerosis. Medicina 2022, 58, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo García, J.C.; Ruiz Rengifo, G.M.; Cardona Nieto, D.; Echeverri Chica, J.; Arcila Arango, J.C.; Campuzano Zuluaga, G.; Ramos-Álvarez, O. Effects of Strength Training Assessed by Anthropometry and Muscle Ultrasound. Muscles 2025, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Shi, S.; Pan, S.; Liu, Z. Advanced glycation end products induce skeletal muscle atrophy and insulin resistance via activating ROS-mediated ER stress PERK/FOXO1 signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 324, E279–E287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Yin, F. Hypoglycemic drug liraglutide alleviates low muscle mass by inhibiting the expression of MuRF1 and MAFbx in diabetic muscle atrophy. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2023, 86, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zou, P.; Peng, Y.; An, Y.; Chen, H.; Luo, P.; Wei, S. The Role of Grifola frondosa Polysaccharide in Preventing Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Life 2024, 14, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKendry, J.; Coletta, G.; Nunes, E.A.; Lim, C.; Phillips, S.M. Mitigating disuse-induced skeletal muscle atrophy in ageing: Resistance exercise as a critical countermeasure. Exp. Physiol. 2024, 109, 1650–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Liu, C.; Jiang, N.; Liu, Y.; Luo, S.; Li, C.; Zhao, H.; Han, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, L.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 in metabolic syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1220426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oost, L.J.; Kustermann, M.; Armani, A.; Blaauw, B.; Romanello, V. Fibroblast growth factor 21 controls mitophagy and muscle mass. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yu, L.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Yu, N.; Peng, D.; Ou, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Poria cocos polysaccharides alleviate obesity-related adipose tissue insulin resistance via gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids activation of FGF21/PI3K/AKT signaling. Food Res. Int. 2025, 215, 116671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y. FGF21 restores metabolic function in Alzheimer’s disease via activation of PI3K/Akt signaling. Neurol. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. The PI3K/AKT pathway in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Song, W. Resistance training increases fibroblast growth factor-21 and irisin levels in the skeletal muscle of Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J. Exerc. Nutrition Biochem. 2017, 21, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodine, S.C.; Stitt, T.N.; Gonzalez, M.; Kline, W.O.; Stover, G.L.; Bauerlein, R.; Zlotchenko, E.; Scrimgeour, A.; Lawrence, J.C.; Glass, D.J.; et al. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuthbertson, D.J.; Babraj, J.; Leese, G.; Siervo, M. Anabolic resistance does not explain sarcopenia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, compared with healthy controls, despite reduced mTOR pathway activity. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdy, M.A.A. Skeletal muscle fibrosis: An overview. Cell Tissue Res. 2019, 375, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, Q.; Zou, Y.; Wang, B.; Huang, S.; Tian, J.; Zheng, L.; Peng, X.; Tang, C. Type 2 Diabetes Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Zebrafish Skeletal Muscle Leading to Diabetic Myopathy via the miR-139-5p/NAMPT Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berria, R.; Wang, L.; Richardson, D.K.; Finlayson, J.; Belfort, R.; Pratipanawatr, T.; De Filippis, E.A.; Kashyap, S.; Mandarino, L.J. Increased collagen content in insulin-resistant skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 290, E560–E565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Sanotra, M.R.; Huang, C.C.; Hsu, Y.J.; Liao, C.C. Aerobic Exercise Modulates Proteomic Profiles in Gastrocnemius Muscle of db/db Mice, Ameliorating Sarcopenia. Life 2024, 14, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Takahashi, F.; Okamura, T.; Hamaguchi, M.; Fukui, M. Diet, exercise, and pharmacotherapy for sarcopenia in people with diabetes. Metabolism 2023, 144, 155585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Q.; Shi, H.; Gan, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Y. Aerobic exercise improves inflammation and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle by regulating miR-221-3p via JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1534911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jun, B.G.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, C.H.; Lim, Y. Effects of Bioconverted Guava Leaf (Psidium guajava L.) Extract on Skeletal Muscle Damage by Regulation of Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Apoptosis in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirvani, H.; Mirnejad, R.; Soleimani, M.; Arabzadeh, E. Swimming exercise improves gene expression of PPAR-γ and downregulates the overexpression of TLR4, MyD88, IL-6, and TNF-α after high-fat diet in rat skeletal muscle cells. Gene 2021, 775, 145441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molanouri Shamsi, M.; Hassan, Z.H.; Gharakhanlou, R.; Quinn, L.S.; Azadmanesh, K.; Baghersad, L.; Isanejad, A.; Mahdavi, M. Expression of interleukin-15 and inflammatory cytokines in skeletal muscles of STZ-induced diabetic rats: Effect of resistance exercise training. Endocrine 2014, 46, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. Podophyllotoxin Alleviates DSS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis via PI3K/AKT Pathway Activation. Physiol. Res. 2025, 74, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Lv, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; et al. Insulin inhibits inflammation and promotes atherosclerotic plaque stability via PI3K-Akt pathway activation. Immunol. Lett. 2016, 170, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Rao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Chen, P.; Xiao, W. High-Intensity Interval Training Restores Glycolipid Metabolism and Mitochondrial Function in Skeletal Muscle of Mice With Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, L.; Robinson, M.; Geetha, T.; Broderick, T.L.; Babu, J.R. Prevalence and Mechanisms of Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Metabolic Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, J.F.; Luiken, J.J.; Bonen, A. Membrane fatty acid transporters as regulators of lipid metabolism: Implications for metabolic disease. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 367–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.Y.; Ren, L.P.; Chen, S.C.; Wang, C.; Liu, N.; Wei, L.M.; Li, F.; Sun, W.; Peng, L.B.; Tang, Y. Similar changes in muscle lipid metabolism are induced by chronic high-fructose feeding and high-fat feeding in C57BL/J6 mice. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2012, 39, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron-Smith, D.; Burke, L.M.; Angus, D.J.; Tunstall, R.J.; Cox, G.R.; Bonen, A.; Hawley, J.A.; Hargreaves, M. A short-term, high-fat diet up-regulates lipid metabolism and gene expression in human skeletal muscle. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.C.; Mullen, K.L.; Junkin, K.A.; Nickerson, J.; Chabowski, A.; Bonen, A.; Dyck, D.J. Metformin and exercise reduce muscle FAT/CD36 and lipid accumulation and blunt the progression of high-fat diet-induced hyperglycemia. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 293, E172–E181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Zhang, H.; He, C.; An, Y.; Huang, Y.; Fu, W.; Wang, M.; Du, Y.; Xie, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. High-Protein Mulberry Leaves Improve Glucose and Lipid Metabolism via Activation of the PI3K/Akt/PPARα/CPT-1 Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.J.; Choung, S.Y. Codonopsis lanceolata ameliorates sarcopenic obesity via recovering PI3K/Akt pathway and lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle. Phytomedicine 2022, 96, 153877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palamiuc, L.; Schlagowski, A.; Ngo, S.T.; Vernay, A.; Dirrig-Grosch, S.; Henriques, A.; Boutillier, A.L.; Zoll, J.; Echaniz-Laguna, A.; Loeffler, J.P.; et al. A metabolic switch toward lipid use in glycolytic muscle is an early pathologic event in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 526–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pin, F.; Novinger, L.J.; Huot, J.R.; Harris, R.A.; Couch, M.E.; O’Connell, T.M.; Bonetto, A. PDK4 drives metabolic alterations and muscle atrophy in cancer cachexia. Faseb j 2019, 33, 7778–7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abi Akar, E.; Weill, L.; El Khoury, M.; Caradeuc, C.; Bertho, G.; Boutary, S.; Bezier, C.; Clerc, Z.; Sapaly, D.; Bendris, S.; et al. The analysis of the skeletal muscle metabolism is crucial for designing optimal exercise paradigms in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Creer, A.; Jemiolo, B.; Trappe, S. Time course of myogenic and metabolic gene expression in response to acute exercise in human skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2005, 98, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Gan, J.; Wang, B.; Lei, W.; Zhen, D.; Yang, J.; Wang, N.; Wen, C.; Gao, X.; Li, X.; et al. FGF21 protects against HFpEF by improving cardiac mitochondrial bioenergetics in mice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Sun, H.; Song, G.; Yang, Y.; Zou, X.; Han, P.; Li, S. Resveratrol Improves Muscle Atrophy by Modulating Mitochondrial Quality Control in STZ-Induced Diabetic Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1700941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Qi, X.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Cheng, P.; Yu, X.; Sun, X.; Wu, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Flavonoids extracted from mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaf improve skeletal muscle mitochondrial function by activating AMPK in type 2 diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 248, 112326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, F.; Jiang, P. Effect of sitagliptin on expression of skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α and irisin in a rat model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060519885569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mey, J.T.; Blackburn, B.K.; Miranda, E.R.; Chaves, A.B.; Briller, J.; Bonini, M.G.; Haus, J.M. Dicarbonyl stress and glyoxalase enzyme system regulation in human skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2018, 314, R181–R190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Kreutz, T.; Schiffer, T.; Opitz, D.; Hermann, R.; Gehlert, S.; Bloch, W.; Brixius, K.; Brinkmann, C. Training-induced alterations of skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis proteins in non-insulin-dependent type 2 diabetic men. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012, 90, 1634–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliavacca, E.; Tay, S.K.H.; Patel, H.P.; Sonntag, T.; Civiletto, G.; McFarlane, C.; Forrester, T.; Barton, S.J.; Leow, M.K.; Antoun, E.; et al. Mitochondrial oxidative capacity and NAD(+) biosynthesis are reduced in human sarcopenia across ethnicities. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theilen, N.T.; Kunkel, G.H.; Tyagi, S.C. The Role of Exercise and TFAM in Preventing Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232, 2348–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.C. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Its Involvement in Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2020, 15, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Gan, M.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; Liao, T.; Zhao, M.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; et al. The role of mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy in skeletal muscle atrophy: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic insights. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2024, 29, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salagre, D.; Raya Álvarez, E.; Cendan, C.M.; Aouichat, S.; Agil, A. Melatonin Improves Skeletal Muscle Structure and Oxidative Phenotype by Regulating Mitochondrial Dynamics and Autophagy in Zücker Diabetic Fatty Rat. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiwan, N.C.; Appell, C.R.; Wang, R.; Shen, C.L.; Luk, H.Y. Geranylgeraniol Supplementation Mitigates Soleus Muscle Atrophy via Changes in Mitochondrial Quality in Diabetic Rats. In Vivo 2022, 36, 2638–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, R.; Pedersen, A.J.; Kristensen, J.M.; Petersson, S.J.; Wojtaszewski, J.F.; Højlund, K. Intact initiation of autophagy and mitochondrial fission by acute exercise in skeletal muscle of patients with Type 2 diabetes. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, D.; Arai, K.; Iijima, M.; Sesaki, H. Mitochondrial division, fusion and degradation. J. Biochem. 2020, 167, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefis, M.; Dargegen, M.; Marcangeli, V.; Taherkhani, S.; Dulac, M.; Leduc-Gaudet, J.P.; Mayaki, D.; Hussain, S.N.A.; Gouspillou, G. MFN2 overexpression in skeletal muscles of young and old mice causes a mild hypertrophy without altering mitochondrial respiration and H(2)O(2) emission. Acta Physiol. 2024, 240, e14119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaoka, Y.; Ogasawara, R.; Tamura, Y.; Fujita, S.; Hatta, H. Effect of electrical stimulation-induced resistance exercise on mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins in rat skeletal muscle. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 40, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Chen, Y.F.; Zou, S.Y.; Wang, W.J.; Zhang, N.N.; Sun, Z.Y.; Xian, W.; Li, X.R.; Tang, B.; Wang, H.J.; et al. ALDH2 attenuates ischemia and reperfusion injury through regulation of mitochondrial fusion and fission by PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 195, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Liang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Hong, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Liu, Z.; Wang, P. Non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction via PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway in diabetic tubulopathy. Redox Biol. 2023, 68, 102946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | Sequences | |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | Forward Reverse | ATCACTATTGGCAACGAGCGGTTC CAGCACTGTGTTGGCATAGAGGTC |

| HMGCR | Forward Reverse | GACCAACCTTCTACCTCAGCAAGC CCAGCCATCACAGTGCCACATAC |

| SCD1 | Forward Reverse | AGCCTGTTCGTTAGCACCTTCTT GGTGTGGTGGTAGTTGTGGAAGC |

| SREBF1 | Forward Reverse | CGACATCGAAGACATGCTTCAG GGAAGGCTTCAAGAGAGGAGC |

| PPARα | Forward Reverse | ACGATGCTGTCCTCCTTGATGAAC GATGTCACAGAACGGCTTCCTCAG |

| TFAM | Forward Reverse | GGAATGTGGAGCGTGCTAAAA TGCTGGAAAAACACTTCGGAATA |

| NRF1 | Forward Reverse | GTTGCCCAAGTGAATTACTCTG TCGTCTGGATGGTCATTTCAC |

| TGF-β1 | Forward Reverse | TGCGCTTGCAGAGATTAAAA CGTCAAAAGACAGCCACTCA |

| COL-3 | Forward Reverse | GTTCACGTACACTGCCCTGA AAGGCGTGAGGTCTTCTGTG |

| IL-1β | Forward Reverse | GAAATGCCACCTTTTGACAGTG TGGATGCTCTCATCAGGACAG |

| IL-6 | Forward Reverse | CAGCCACTGCCTTCCCTACT CAGTGCATCAT CGCTGTTCAT |

| TNF-α | Forward Reverse | CTTCTGTCTACTGAACTTCGGG CACTTGGTGGTTTGCTACGAC |

| IL-10 | Forward Reverse | CAAGGAGCATTTGAATTCCC GGCCTTGTAGACACCTTGGTC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, X.; Rao, Z.; Jin, Z.; Lu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, L. Resistance Exercise Counteracts Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in T2DM Mice by Upregulating FGF21 and Activating PI3K/Akt Pathway. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010003

Ma X, Rao Z, Jin Z, Lu Y, Sun Z, Zheng L. Resistance Exercise Counteracts Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in T2DM Mice by Upregulating FGF21 and Activating PI3K/Akt Pathway. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Xiaojie, Zhijian Rao, Zhihai Jin, Yibing Lu, Zhitong Sun, and Lifang Zheng. 2026. "Resistance Exercise Counteracts Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in T2DM Mice by Upregulating FGF21 and Activating PI3K/Akt Pathway" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010003

APA StyleMa, X., Rao, Z., Jin, Z., Lu, Y., Sun, Z., & Zheng, L. (2026). Resistance Exercise Counteracts Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in T2DM Mice by Upregulating FGF21 and Activating PI3K/Akt Pathway. Biomolecules, 16(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010003