LRP1 Interacts with the Rift Valley Fever Virus Glycoprotein Gn via a Calcium-Dependent Multivalent Electrostatic Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein Expression and Purification

2.2. Size-Exclusion Chromatography and Western Blot

2.3. Negative-Staining Sample Preparation

2.4. Bio-Layer Interferometry Binding Assay

2.5. AlphaFold3-Based Structural Modeling and Interface Analysis

3. Results

3.1. LRP1 Directly Interacts with the RVFV Gn Head in a Calcium-Dependent Manner

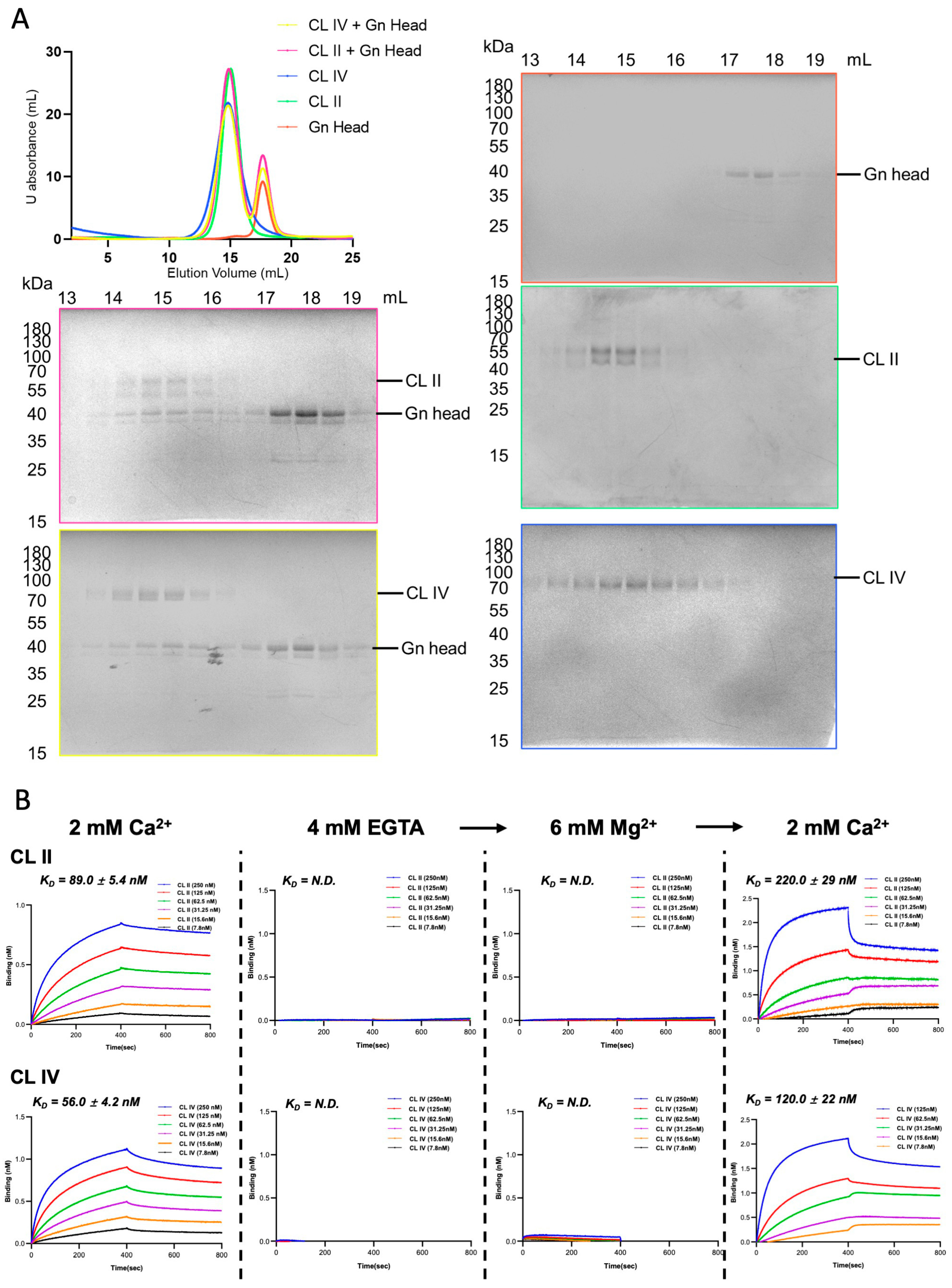

3.2. Both the CL II and CL IV Domains of Human LRP1 Interact with RVFV Gn in a Ca2+-Dependent Manner

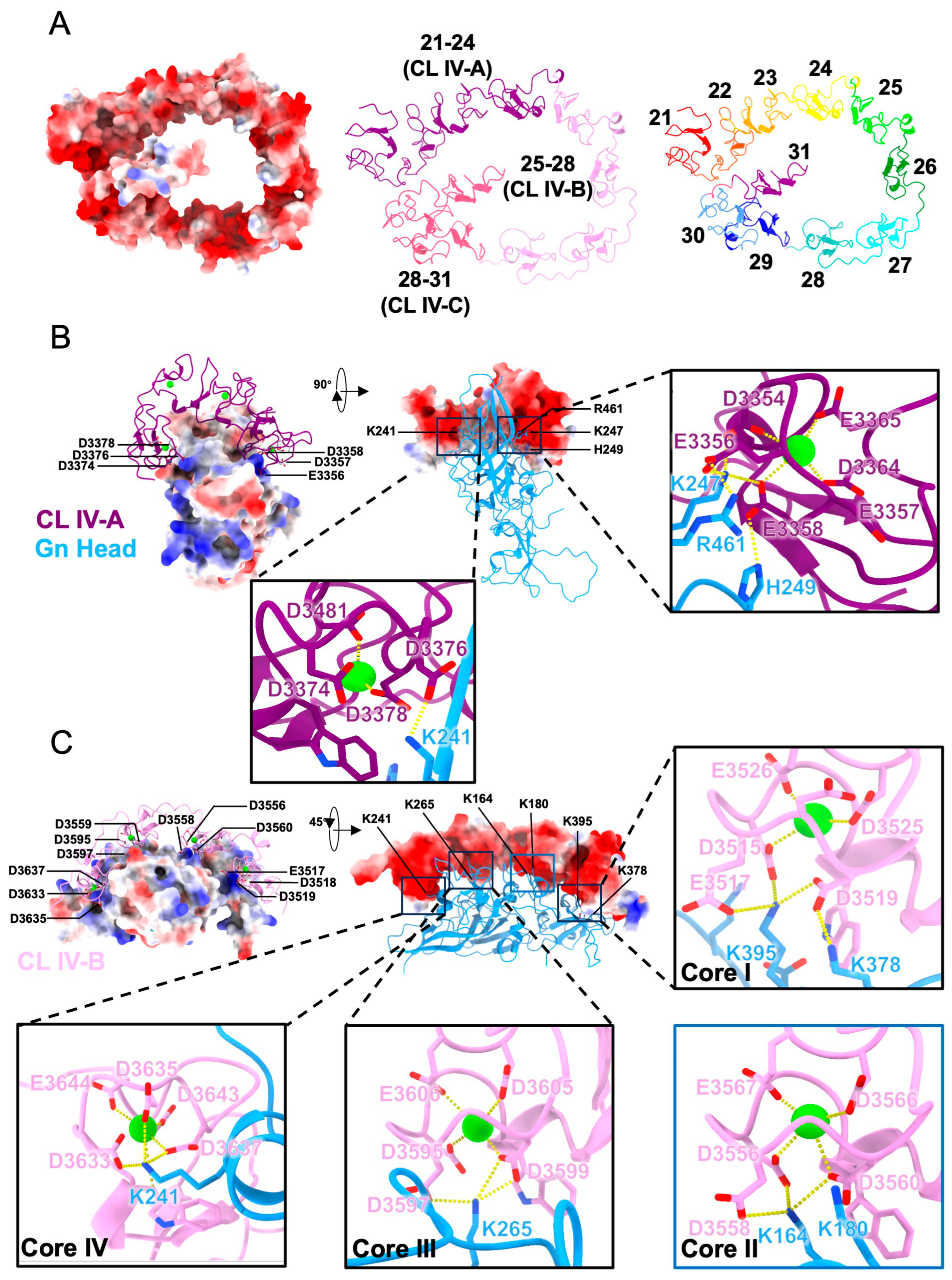

3.3. Predicted Structures of Gn-CL IV Complexes Reveal Ca2+-Stabilized Multivalent Electrostatic Interfaces

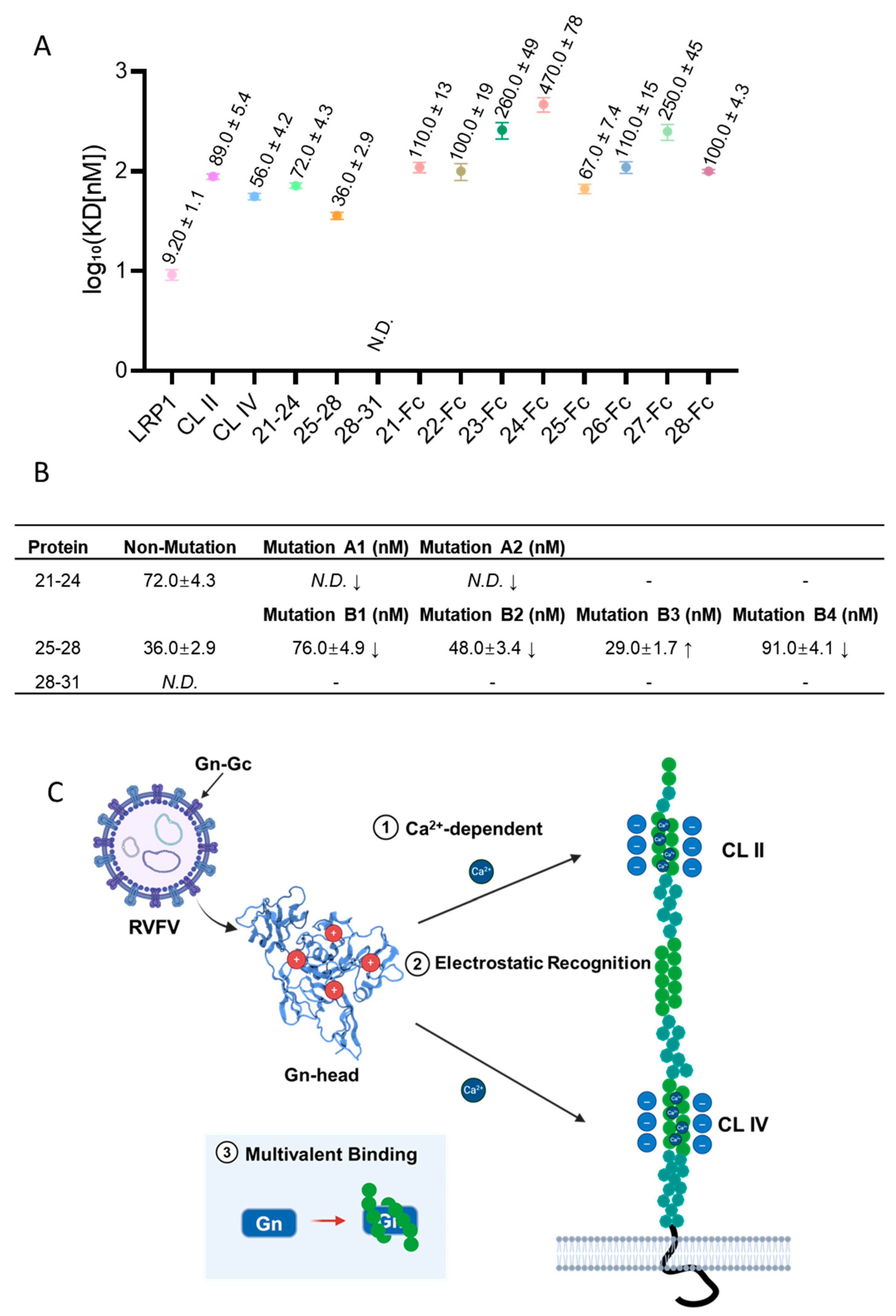

3.4. Mutational and Domain Analyses Reveal That Ca2+ Coordination and Electrostatic Complementarity Cooperatively Mediate Gn–LRP1 Interaction

3.5. Proposed Model of the Gn-LRP1 Interaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Afshar Moghaddam, N.; Yekanipour, Z.; Akbarzadeh, S.; Molavi Nia, S.; Abarghooi Kahaki, F.; Kalantar, M.H.; Gholizadeh, O. Recent advances in treatment and detection of Rift Valley fever virus: A comprehensive overview. Virus Genes 2025, 61, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubney, R.; Hudson, J.R.; bacteriology. Enzootic Hepatitis or Rift Valley Fever. An Un–described Virus Disease of Sheep, Cattle and Man from East Africa. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1931, 34, 545–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Arm race between Rift Valley fever virus and host. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1084230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostal, M.K.; Thompson, P.N.; Anyamba, A.; Bett, B.; Cetre–Sossah, C.; Chevalier, V.; Guarido, M.; Karesh, W.B.; Kemp, A.; LaBeaud, A.D.; et al. Rift Valley fever epidemiology: Shifting the paradigm and rethinking research priorities. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, 101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapa, D.; Pauciullo, S.; Ricci, I.; Garbuglia, A.R.; Maggi, F.; Scicluna, M.T.; Tofani, S. Rift Valley Fever Virus: An Overview of the Current Status of Diagnostics. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitandwe, P.K.; McKay, P.F.; Kaleebu, P.; Shattock, R.J. An Overview of Rift Valley Fever Vaccine Development Strategies. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, S.; Zhang, L. Research trends in Rift Valley fever virus: A bibliometric analysis from 1936 to 2024. Front Vet Sci 2025, 12, 1611642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkan, C.; Jurado-Cobena, E.; Ikegami, T. Advancements in Rift Valley fever vaccines: A historical overview and prospects for next generation candidates. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkin, D.; Wright, D.; Folegatti, P.M.; Platt, A.; Poulton, I.; Lawrie, A.; Tran, N.; Boyd, A.; Turner, C.; Gitonga, J.N.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a ChAdOx1 vaccine against Rift Valley fever in UK adults: An open–label, non-randomised, first–in–human phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroline, A.L.; Powell, D.S.; Bethel, L.M.; Oury, T.D.; Reed, D.S.; Hartman, A.L. Broad spectrum antiviral activity of favipiravir (T–705): Protection from highly lethal inhalational Rift Valley Fever. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, K.A.; Chapman, N.S.; McMillen, C.M.; Hoehl, R.M.; McGaughey, J.J.; Frey, Z.D.; Midgett, M.; Williams, C.; Reed, D.S.; Crowe, J.E.; et al. Potent neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies protect from Rift Valley fever encephalitis. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e180151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Celma, C.C.; Roy, P. Rift Valley fever virus structural proteins: Expression, characterization and assembly of recombinant proteins. Virol. J. 2008, 5, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiskonen, J.T.; Overby, A.K.; Weber, F.; Grünewald, K. Electron cryo–microscopy and single–particle averaging of Rift Valley fever virus: Evidence for GN–GC glycoprotein heterodimers. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 3762–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorsson, S.; Li, S.; Li, M.; Harlos, K.; Bowden, T.A.; Huiskonen, J.T. Shielding and activation of a viral membrane fusion protein. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganaie, S.S.; Leung, D.W.; Hartman, A.L.; Amarasinghe, G.K. Host entry factors of Rift Valley Fever Virus infection. Adv. Virus Res. 2023, 117, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganaie, S.S.; Schwarz, M.M.; McMillen, C.M.; Price, D.A.; Feng, A.X.; Albe, J.R.; Wang, W.; Miersch, S.; Orvedahl, A.; Cole, A.R.; et al. Lrp1 is a host entry factor for Rift Valley fever virus. Cell 2021, 184, 5163–5178.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, M.M.; Ganaie, S.S.; Feng, A.; Brown, G.; Yangdon, T.; White, J.M.; Hoehl, R.M.; McMillen, C.M.; Rush, R.E.; Connors, K.A.; et al. Lrp1 is essential for lethal Rift Valley fever hepatic disease in mice. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, A.P.; Van Duyn, L.B.; Murphy–Ullrich, J.E.; Strickland, D.K. LDL receptor–related protein 1: Unique tissue–specific functions revealed by selective gene knockout studies. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 887–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, W.; Tang, M.; Jiang, H.; Xu, W.; Hao, W.; Sui, Y.; Hou, Y.; Nie, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; et al. Low–density–lipoprotein–receptor–related protein 1 mediates Notch pathway activation. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 2902–2919.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, C.; Xu, B.; Chen, J.; Yang, M.; Gao, L.; Zhou, J. The LDL Receptor–Related Protein 1: Mechanisms and roles in promoting Abeta efflux transporter in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 231, 116643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Scilabra, S.D.; Bonelli, S.; Jensen, A.; Scavenius, C.; Enghild, J.J.; Strickland, D.K. Novel insights into the multifaceted and tissue–specific roles of the endocytic receptor LRP1. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neels, J.G.; van Den Berg, B.M.; Lookene, A.; Olivecrona, G.; Pannekoek, H.; van Zonneveld, A.J. The second and fourth cluster of class A cysteine–rich repeats of the low density lipoprotein receptor–related protein share ligand–binding properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 31305–31311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O.M.; Vorum, H.; Honore, B.; Thogersen, H.C. Ca2+ binding to complement–type repeat domains 5 and 6 from the low–density lipoprotein receptor–related protein. BMC Biochem. 2003, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E.; Henrick, K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 372, 774–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ‘Protein Interfaces, Surfaces and Assemblies’ Service PISA at the European Bioinformatics Institute. Available online: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/prot_int/pistart.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ma, B.; Huang, C.; Ma, J.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, X. Structure of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus with its receptor LDLRAD3. Nature 2021, 598, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Ma, B.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, Y. Structure of Semliki Forest virus in complex with its receptor VLDLR. Cell 2023, 186, 2208–2218 e2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Ma, B.; Cao, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, Y. The receptor VLDLR binds Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus through multiple distinct modes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gommet, C.; Billecocq, A.; Jouvion, G.; Hasan, M.; Zaverucha do Valle, T.; Guillemot, L.; Blanchet, C.; van Rooijen, N.; Montagutelli, X.; Bouloy, M.J.P.n.t.d. Tissue tropism and target cells of NSs–deleted rift valley fever virus in live immunodeficient mice. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendaal, L.; Davis, A.S.; Venter, E.H. Insights into the Pathogenesis of Viral Haemorrhagic Fever Based on Virus Tropism and Tissue Lesions of Natural Rift Valley Fever. Viruses 2021, 13, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.G.; Lv, J.; Hu, X.D.; Shi, L.L.; Chang, K.W.; Chen, X.L.; Qian, Y.H.; Yang, W.N.; Qu, Q.M. The p38 mitogen–activated protein kinase signaling pathway is involved in regulating low–density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 1–mediated beta–amyloid protein internalization in mouse brain. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 76, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Li, S.; Wang, A.; Zhe, M.; Yang, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, G.; et al. p38 mitogen–activated protein kinase: Functions and targeted therapy in diseases. MedComm–Oncol. 2023, 2, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Rao, G.; Zhang, C.; Guan, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, S.; Lozach, P.Y.; Cao, S.; Peng, K. Rift Valley fever virus coordinates the assembly of a programmable E3 ligase to promote viral replication. Cell 2024, 187, 6896–6913.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, Y.; Qiu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Gou, K.; et al. Epigenetic regulation in cancer therapy: From mechanisms to clinical advances. MedComm–Oncol. 2024, 3, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Song, X.; Chen, W.; Liang, H.; Nakatsukasa, H.; Zhang, D. cGAS–STING signaling in cancer: Regulation and therapeutic targeting. MedComm–Oncol. 2023, 2, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, H.; Chen, H.; Jiang, W.; Yan, R. LRP1 Interacts with the Rift Valley Fever Virus Glycoprotein Gn via a Calcium-Dependent Multivalent Electrostatic Mechanism. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010014

Yang H, Chen H, Jiang W, Yan R. LRP1 Interacts with the Rift Valley Fever Virus Glycoprotein Gn via a Calcium-Dependent Multivalent Electrostatic Mechanism. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Haonan, Haojin Chen, Wanyan Jiang, and Renhong Yan. 2026. "LRP1 Interacts with the Rift Valley Fever Virus Glycoprotein Gn via a Calcium-Dependent Multivalent Electrostatic Mechanism" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010014

APA StyleYang, H., Chen, H., Jiang, W., & Yan, R. (2026). LRP1 Interacts with the Rift Valley Fever Virus Glycoprotein Gn via a Calcium-Dependent Multivalent Electrostatic Mechanism. Biomolecules, 16(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010014