Combined Radiations: Biological Effects of Mixed Exposures Across the Radiation Spectrum

Abstract

1. Introduction

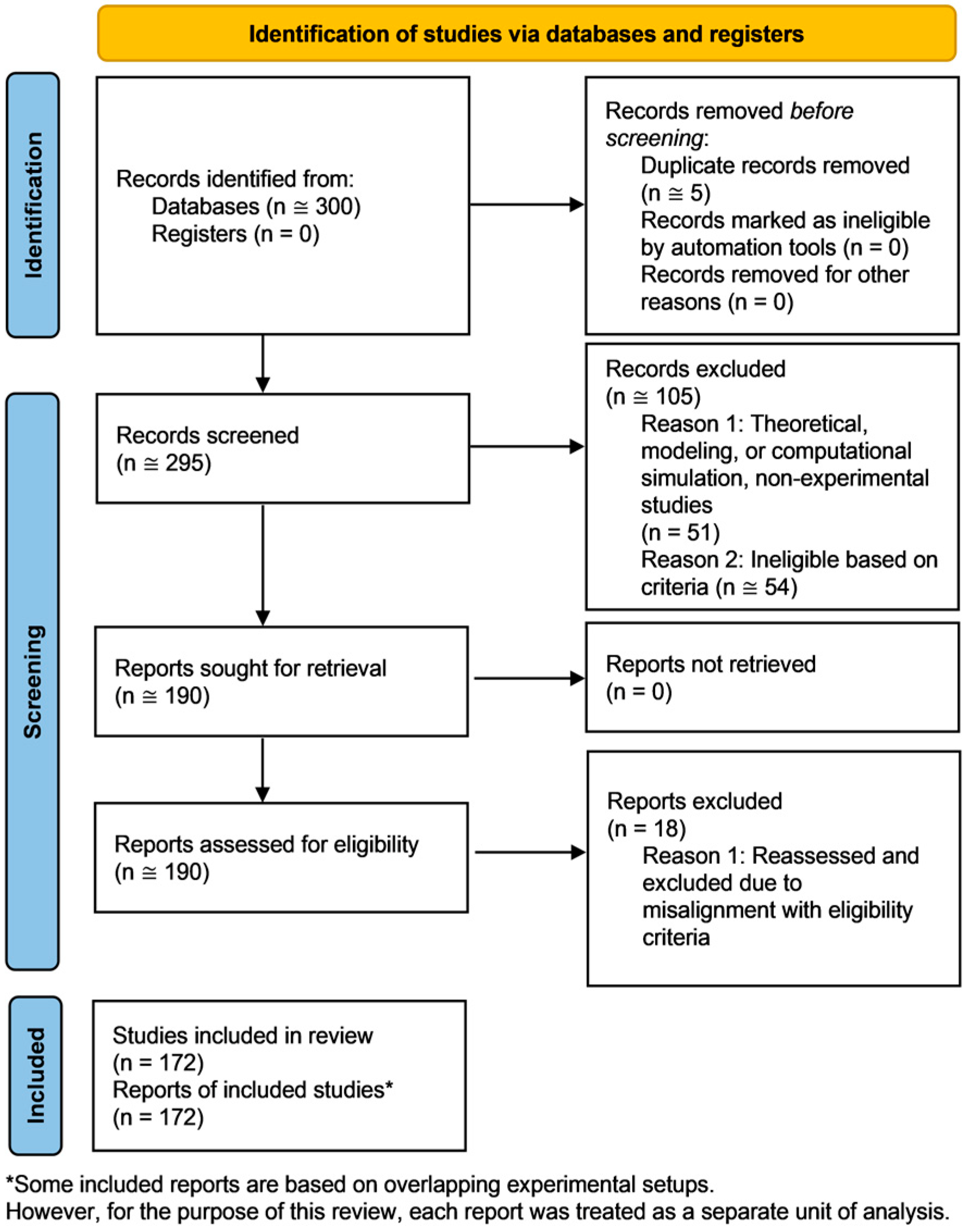

2. Methods

- (“alpha radiation”[tiab] OR “alpha particles”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“X-rays”[MeSH Terms] OR “X radiation”[tiab]).

- (“simultaneous”[tiab] OR “sequential”[tiab]) AND (“irradiation”[tiab] OR “radiation”[MeSH Terms]).

- “proton therapy”[tiab] AND “targeted radionuclide therapy”[tiab].

- “space radiation”[tiab] OR “simulated galactic cosmic rays”[tiab] OR “GCRsim”[tiab].

3. Results

3.1. Radiobiological Studies

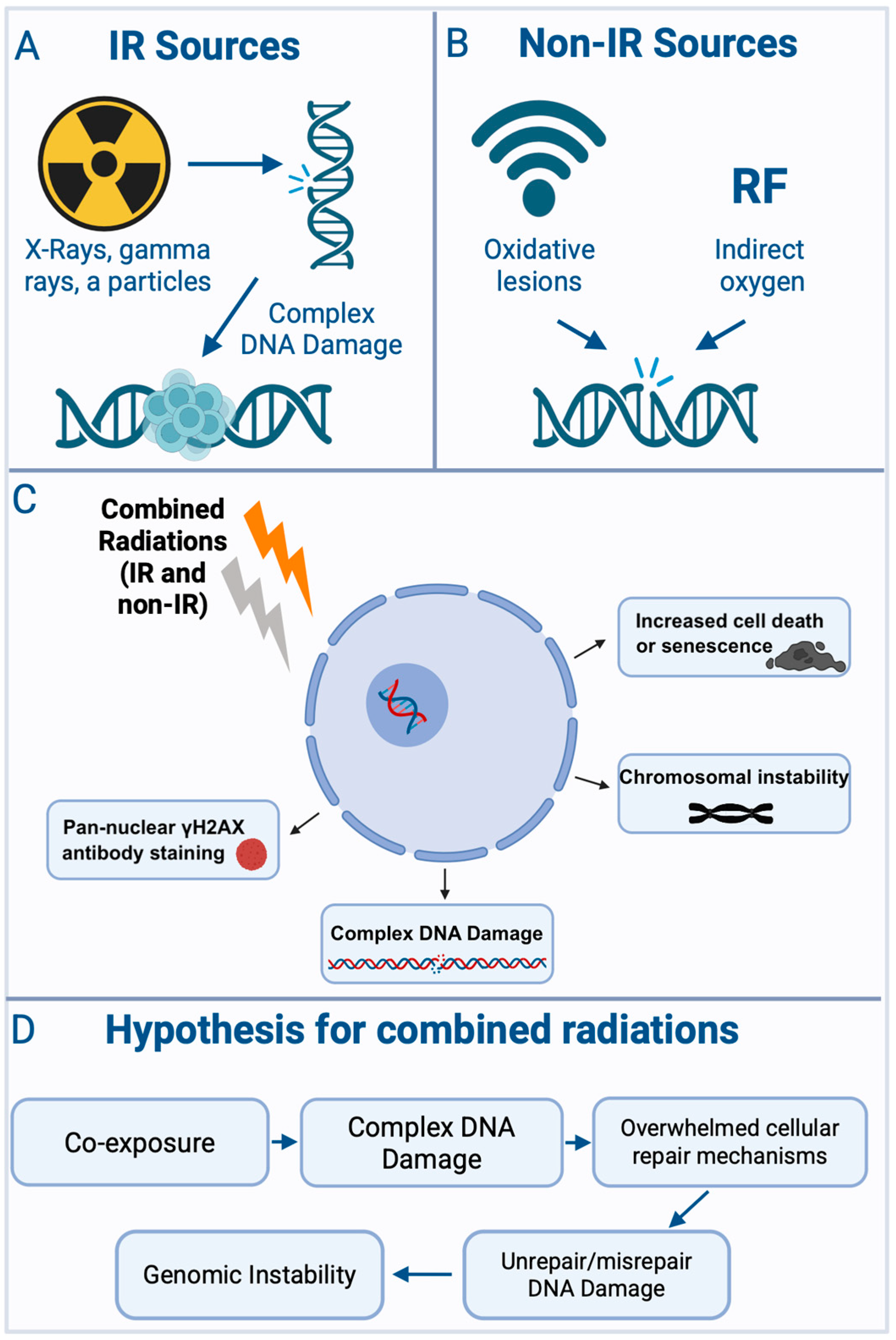

3.1.1. Combinations of Non-Ionizing and Ionizing Radiation

3.1.2. Combinations of Non-Ionizing Radiation Types

3.1.3. Combinations of Ionizing Radiation Types

3.2. Therapeutic Studies

3.3. Space Radiation Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanistic Basis of Mixed-Radiation Effects

4.1.1. Exposure Sequence Dependence in Mixed-Radiation Exposures

4.1.2. DNA Repair Dependencies, Lesion Interactions, and Temporal Modulation

4.1.3. Cell-Cycle-Specific Interaction Effects

4.1.4. Mechanistic Insights from Non-Ionizing Radiation Combinations

4.1.5. Mechanisms and Functional Consequences of Combined Ionizing Radiation Exposure

4.1.6. Multiscale Biological Effects and Uncommon Exposure Scenarios

4.2. Determinants and Mechanisms of Synergy

4.3. Therapeutic and Protective Strategies

4.4. Space and Environmental Risk Contexts

4.5. Methodological Challenges and Experimental Gaps

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EURAMET | European Association of National Metrology Institutes |

| Europe PMC | Europe PubMed Central |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

References

- Blanco, Y.; De Diego-Castilla, G.; Viúdez-Moreiras, D.; Cavalcante-Silva, E.; Rodríguez-Manfredi, J.A.; Davila, A.F.; McKay, C.P.; Parro, V. Effects of gamma and electron radiation on the structural integrity of organic molecules and macromolecular biomarkers measured by microarray immunoassays and their astrobiological implications. Astrobiology 2018, 18, 1497–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljabab, S.; Lui, A.; Wong, T.; Liao, J.; Laramore, G.; Parvathaneni, U. A combined neutron and proton regimen for advanced salivary tumors: Early clinical experience. Cureus 2021, 13, e14844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Moon, B.-H.; Kumar, S.; Angdisen, J.; Kallakury, B.V.S.; Fornace, A.J.; Suman, S. Senolytic agent ABT-263 mitigates low- and high-LET radiation-induced gastrointestinal cancer development in Apc1638N/+ mice. Aging 2025, 17, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, M. Lack of synergistic effect between X-ray and UV irradiation on the frequency of chromosome aberrations in PHA-stimulated human lymphocytes in the G1 stage. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1976, 34, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, M.; Jonasson, J. Synergistic effect of X-ray and UV irradation on the frequency of chromosome breakage in human lymphocytes. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1974, 23, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, B.; Hansson, K.; Bui, T.H.; Funes-Cravioto, F.; Lindsten, J.; Holmberg, M.; Strausmanis, R. DNA repair and frequency of X-ray and U.V.-light induced chromosome aberrations in leukocytes from patients with Down’s syndrome. Ann. Hum. Genet. 1976, 39, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmberg, M.; Strausmanis, R. The repair of chromosome aberrations in human lymphocytes after combined irradiation with UV-radiation (254 nm) and X-rays. Mutat. Res. Lett. 1983, 120, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Elkind, M.M. Ultraviolet light and X-ray damage interaction in Chinese hamster cells. Radiat. Res. 1978, 74, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martignoni, K.D.; Smith, K.C. The synergistic action of ultraviolet and X radiation on mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. Photochem. Photobiol. 1973, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrrell, R.M. The interaction of near U.V. (365 nm) and X-radiations on wild-type and repair-deficient strains of Escherichia coli K-12: Physical and biological measurements. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 1974, 25, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptist, J.E.; Haynes, R.H. The U.V.-X-ray synergism in Escherichia coli B-r. I. Inhibition by the incorporation of 5-bromouracil and by purine starvation. Photochem. Photobiol. 1972, 16, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.; Kiefer, J. Interaction of ionizing radiation and ultraviolet-light in diploid yeast strains of different sensitivity. Photochem. Photobiol. 1976, 24, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentner, N.E.; Werner, M.M. Synergistic interaction between UV and ionizing radiation in wild-type Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG 1978, 164, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, N.F.; Shah, A.R.; Kumta, U.S. Synergistic killing effect in pre-UV-irradiated Micrococcus radiophilus. Photochem. Photobiol. 1975, 22, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, S.A.; Khaliq, S.; Ahmad, S.; Ashraf, N.; Ghauri, M.A.; Anwar, M.A.; Akhtar, K. Application of combined irradiation mutagenesis technique for hyperproduction of surfactin in Bacillus velezensis strain AF_3B. Int. J. Microbiol. 2025, 2025, 5570585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Kondo, S. Synergistic effects of P32 decay and ultraviolet irradiation on inactivation of Salmonella. Radiat. Res. 1964, 22, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, A. Inhibition of the UV-ionizing radiation synergism in Escherichia coli B/r by liquid holding between the two irradiations. Photochem. Photobiol. 1973, 18, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, G.J.; Bance, D.A.; Cox, R.; Preston, R.J.; Richards, V.; Stephens, M.A.; Stretch, A.; Wilkinson, R.E. A synergistic interaction between U.V. and protons in causing loss of reproductive capacity in Escherichia coli B/r. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 1974, 26, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, A.; Zöller, N.; Kippenberger, S.; Bernd, A.; Kaufmann, R.; Layer, P.G.; Heselich, A. Non-thermal near-infrared exposure photobiomodulates cellular responses to ionizing radiation in human full thickness skin models. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 178, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalesskaya, G.A.; Batay, L.E.; Koshlan, I.V.; Nasek, V.M.; Zilberman, R.D.; Milevich, T.I.; Govorun, R.D.; Koshlan, N.A.; Blaga, P. Combined impact of gamma and laser radiation on peripheral blood of rats in vivo. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2017, 84, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreck, A.; Csoma, Z.; Borosgyevi, M.; Ignacz, F.; Bodai, L.; Dobozy, A.; Kemeny, L. Inhibition of immediate type hypersensitivity reaction by combined irradiation with ultraviolet and visible light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2004, 77, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, C.W.; Cho, K.H.; Chung, J.H. Infrared plus visible light and heat from natural sunlight participate in the expression of MMPs and type I procollagen as well as infiltration of inflammatory cell in human skin in vivo. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008, 50, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, R.J.; de Gruijl, F.R.; van der Leun, J.C. Interaction between ultraviolet A and ultraviolet B radiations in skin cancer induction in hairless mice. Cancer Res. 1993, 53, 4212–4217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L.E.; Treible, L.M. Hanging under the ledge: Synergistic consequences of UVA and UVB radiation on scyphozoan polyp reproduction and health. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheang, W.K.; Wong, G.R.; Rahim, A.N.; Kethiravan, D.; Harikrishna, J.A.; Tan, B.C.; Ramakrishnan, N.; Mazumdar, P. Synergistic effects of UV-B and UV-C in suppressing Sclerotinia sclerotiorum infection in tomato plants. J. Crop Health 2024, 76, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst-Rüd, S.; McNeill, K.; Ackermann, M. Thiouridine residues in tRNAs are responsible for a synergistic effect of UVA and UVB light in photoinactivation of Escherichia coli. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst-Rüd, S.; Nyangaresi, P.O.; Adeyeye, A.A.; Ackermann, M.; Beck, S.E.; McNeill, K. Synergistic effect of UV-A and UV-C light is traced to UV-induced damage of the transfer RNA. Water Res. 2024, 252, 121189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangaresi, P.O.; Qin, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhang, B.; Lu, Y.; Shen, L. Effects of single and combined UV-LEDs on inactivation and subsequent reactivation of E. coli in water disinfection. Water Res. 2018, 147, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Blatchley, E.R.; Xie, T.; Qiang, Z. Water disinfection with dual-wavelength (222 + 275 nm) ultraviolet radiations: Microbial inactivation and reactivation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 1448–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, S.E.; Ryu, H.; Boczek, L.A.; Cashdollar, J.L.; Jeanis, K.M.; Rosenblum, J.S.; Lawal, O.R.; Linden, K.G. Evaluating UV-C LED disinfection performance and investigating potential dual-wavelength synergy. Water Res. 2017, 109, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsenter, I.; Garkusheva, N.; Matafonova, G.; Batoev, V. A novel water disinfection method based on dual-wavelength UV radiation of KrCl (222 nm) and XeBr (282 nm) excilamps. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Mohseni, M.; Taghipour, F. Mechanisms investigation on bacterial inactivation through combinations of UV wavelengths. Water Res. 2019, 163, 114875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhang, H.; Lai, A.C. Inactivation of foodborne pathogenic and spoilage bacteria by single and dual wavelength UV-LEDs: Synergistic effect and pulsed operation. Food Control 2021, 125, 107999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, W.; Sun, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, M.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Hu, P.; et al. Effects of multi-wavelength ultraviolet radiation on the inactivation and reactivation of Escherichia coli in recirculating water system. Aquac. Rep. 2025, 41, 102688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahashi, M.; Mawatari, K.; Hirata, A.; Maetani, M.; Shimohata, T.; Uebanso, T.; Hamada, Y.; Akutagawa, M.; Kinouchi, Y.; Takahashi, A. Simultaneous Irradiation with Different Wavelengths of Ultraviolet Light has Synergistic Bactericidal Effect on Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Photochem. Photobiol. 2014, 90, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.; Beck, S.; Boczek, L.; Carlson, K.; Brinkman, N.; Linden, K.; Lawal, O.; Hayes, S.; Ryu, H. Efficacy of inactivation of human enteroviruses by dual-wavelength germicidal ultraviolet (UV-C) light emitting diodes (LEDs). Water 2019, 11, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, N.M.; Linden, K.G. Synergy of MS2 disinfection by sequential exposure to tailored UV wavelengths. Water Res. 2018, 143, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Moraru, C. Synergistic effects of sequential light treatment with 222-nm/405-nm and 280-nm/405-nm wavelengths on inactivation of foodborne pathogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e00650-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollazzo, A.; Shakeri-Manesh, S.; Fotouhi, A.; Czub, J.; Haghdoost, S.; Wojcik, A. Interaction of low and high LET radiation in TK6 cells—Mechanistic aspects and significance for radiation protection. J. Radiol. Prot. 2016, 36, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra Liberal, F.D.C.; Thompson, S.J.; Prise, K.M.; McMahon, S.J. High-LET radiation induces large amounts of rapidly-repaired sublethal damage. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, M.R.; Jett, J.H. RBE and OER Variations of Mixtures of Plutonium Alpha Particles and X-Rays for Damage to Human Kidney Cells (T-1). Radiat. Res. 1974, 60, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Brzozowska-Wardecka, B.; Lisowska, H.; Wojcik, A.; Lundholm, L. Impact of ATM and DNA-PK inhibition on gene expression and individual response of human lymphocytes to mixed beams of alpha particles and X-rays. Cancers 2019, 11, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staaf, E.; Deperas-Kaminska, M.; Brehwens, K.; Haghdoost, S.; Czub, J.; Wojcik, A. Complex aberrations in lymphocytes exposed to mixed beams of 241Am alpha particles and X-rays. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2013, 756, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staaf, E.; Brehwens, K.; Haghdoost, S.; Nievaart, S.; Pachnerova-Brabcova, K.; Czub, J.; Braziewicz, J.; Wojcik, A. Micronuclei in human peripheral blood lymphocytes exposed to mixed beams of X-rays and alpha particles. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2012, 51, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollazzo, A.; Brzozowska, B.; Cheng, L.; Lundholm, L.; Haghdoost, S.; Scherthan, H.; Wojcik, A. Alpha particles and X rays interact in inducing DNA damage in U2OS cells. Radiat. Res. 2017, 188, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staaf, E.; Brehwens, K.; Haghdoost, S.; Czub, J.; Wojcik, A. Gamma-H2AX foci in cells exposed to a mixed beam of X-rays and alpha particles. Genome Integr. 2012, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Brzozowska, B.; Sollazzo, A.; Lundholm, L.; Lisowska, H.; Haghdoost, S.; Wojcik, A. Simultaneous induction of dispersed and clustered DNA lesions compromises DNA damage response in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollazzo, A.; Brzozowska, B.; Cheng, L.; Lundholm, L.; Scherthan, H.; Wojcik, A. Live dynamics of 53BP1 foci following simultaneous induction of clustered and dispersed DNA damage in U2OS cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Roshan, M.; Belikov, S.; Ix, M.; Protti, N.; Balducci, C.; Dodel, R.; Ross, J.A.; Lundholm, L. Fractionated alpha and mixed beam radiation promote stronger pro-inflammatory effects compared to acute exposure and trigger phagocytosis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1440559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, U.-S.; Lee, D.-H.; Kim, E.-H. Characterization of γ-H2AX foci formation under alpha particle and X-ray exposures for dose estimation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staaf, E.; Brehwens, K.; Haghdoost, S.; Pachnerova-Brabcova, K.; Czub, J.; Braziewicz, J.; Nievaart, S.; Wojcik, A. Characterisation of a setup for mixed beam exposures of cells to 241Am alpha particles and X-rays. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2012, 151, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNally, N.J.; De Ronde, J.; Folkard, M. Interaction between X-ray and α-particle damage in V79 cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1988, 53, 917–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.L.; Newton, G.J.; Shyr, L.-J.; Seiler, F.A.; Scott, B.R. The combined effects of α-particles and X-rays on cell killing and micronuclei induction in lung epithelial cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1990, 58, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Randers-Pehrson, G.; Geard, C.R.; Brenner, D.J.; Hall, E.J.; Hei, T.K. Interaction between radiation-induced adaptive response and bystander mutagenesis in mammalian cells. Radiat. Res. 2003, 160, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tartas, A.; Lundholm, L.; Scherthan, H.; Wojcik, A.; Brzozowska, B. The order of sequential exposure of U2OS cells to gamma and alpha radiation influences the formation and decay dynamics of NBS1 foci. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akuwudike, P.; López-Riego, M.; Ginter, J.; Cheng, L.; Wieczorek, A.; Życieńska, K.; Łysek-Gładysińska, M.; Wojcik, A.; Brzozowska, B.; Lundholm, L. Mechanistic insights from high resolution DNA damage analysis to understand mixed radiation exposure. DNA Repair 2023, 130, 103554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, M.S.S.; Madhvanath, U.; Subrahmanyam, P.; Rao, B.S.; Reddy, N.M.S. Synergistic effect of simultaneous exposure to 60Co gamma rays and 210Po alpha rays in diploid yeast. Radiat. Res. 1975, 63, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubryak, I.; Vilensky, E.; Naumenko, V.; Grodzisky, D. Influence of combined alpha, beta and gamma radionuclide contamination on the frequency of waxy-reversions in barley pollen. Sci. Total Environ. 1992, 112, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killion, D.D.; Constantin, M.J. Effects of separate and combined beta and gamma irradiation on the soybean plant. Radiat. Bot. 1974, 14, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.R.; Hahn, F.F.; Snipes, M.B.; Newton, G.J.; Eidson, A.F.; Mauderly, J.L.; Boecker, B.B. Predicted and observed early effects of combined alpha and beta lung irradiation. Health Phys. 1990, 59, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Grilj, V.; Broustas, C.G.; Ghandhi, S.A.; Harken, A.D.; Garty, G.; Amundson, S.A. Human transcriptomic response to mixed neutron-photon exposures relevant to an improvised nuclear device. Radiat. Res. 2019, 192, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broustas, C.G.; Harken, A.D.; Garty, G.; Amundson, S.A. Identification of differentially expressed genes and pathways in mice exposed to mixed field neutron/photon radiation. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.C.; Geard, C.R.; Marino, S.A.; Richards, M.; Randers-Pehrson, G. Oncogenic transformation following sequential irradiations with monoenergetic neutrons and X rays. Radiat. Res. 1991, 125, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, M.C.; Bremner, J.C.; Denekamp, J.; Maughan, R.L. The interaction between X-rays and 3 MeV neutrons in the skin of the mouse foot. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 1984, 46, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, K. Effects of 14 MeV neutrons and X-rays, singly or combined on the reproductive capacity of L cells. J. Radiat. Res. 1970, 11, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marples, B.; Skov, K.A. Small doses of high-linear energy transfer radiation increase the radioresistance of chinese hamster V79 cells to subsequent X irradiation. Radiat. Res. 1996, 146, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNally, N.J.; De Ronde, J.; Hinchliffe, M. The effect of sequential irradiation with X-rays and fast neutrons on the survival of V79 chinese hamster cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 1984, 45, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, F.Q.H.; Han, A.; Elkind, M.M. On the repair of sub-lethal damage in V79 chinese hamster cells resulting from irradiation with fast neutrons or fast neutrons combined with X-rays. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 1977, 32, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, S.; Andreozzi, U.; Warren, P.R. Sublethal damage in cells of the mouse gut after mixed treatment with X rays and fast neutrons. Br. J. Radiol. 1977, 50, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojcik, A.; Obe, G.; Lisowska, H.; Czub, J.; Nievaart, V.; Moss, R.; Huiskamp, R.; Sauerwein, W. Chromosomal aberrations in peripheral blood lymphocytes exposed to a mixed beam of low energy neutrons and gamma radiation. J. Radiol. Prot. 2012, 32, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmqvist, T.; Lopez-Riego, M.; Bucher, M.; Oestreicher, U.; Pojtinger, S.; Giesen, U.; Toma-Dasu, I.; Wojcik, A. Biological effectiveness of combined exposure to neutrons and gamma radiation applied in two orders of sequence: Relevance for biological dosimetry after nuclear emergencies. Radiat. Med. Prot. 2025, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Chai, D.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, J.; Dong, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Dang, X.; Ning, K. Effects of neutron and gamma rays combined irradiation on the transcriptional profile of human peripheral blood. Radiat. Res. 2023, 200, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S. Survival of chinese hamster V79 cells after irradiation with a mixture of neutrons and 60 co g rays: Experimental and theoretical analysis of mixed irradiation. Radiat. Res. 1993, 133, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posypanova, G.A.; Ratushnyak, M.G.; Semochkina, Y.P.; Strepetov, A.N. Response of murine neural stem/progenitor cells to gamma-neutron radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2022, 98, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-K.C.; Zhang, X.; Gifford, I.; Burgett, E.; Adams, V.; Al-Sheikhly, M. Experimental validation of the new nanodosimetry-based cell survival model for mixed neutron and gamma-ray irradiation. Phys. Med. Biol. 2007, 52, N367–N374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Railton, R.; Lawson, R.C.; Porter, D. Interaction of γ-ray and neutron effects on the proliferative capacity of chinese hamster cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 1975, 27, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, P.D.; DeLuca, P.M.; Pearson, D.W.; Gould, M.N. V79 survival following simultaneous or sequential irradiation by 15-MeV neutrons and 60Co photons. Radiat. Res. 1983, 95, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, P.D.; DeLuca, P.M.; Gould, M.N. Effect of pulsed dose in simultaneous and sequential irradiation of V-79 cells by 14.8-MeV neutrons and 60Co photons. Radiat. Res. 1984, 99, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skidmore, W.D.; McHale, C.G. Fluorescence of serum and urine from rats exposed to mixed gamma-neutron radiations. Radiat. Res. 1969, 38, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubasova, T.; Antal, S.; Somosy, Z.; Köteles, G.J. Effects of mixed neutron-gamma irradiation in vivo on the cell surfaces of murine blood cells. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 1984, 23, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodina, A.V.; Semochkina, Y.P.; Vysotskaya, O.V.; Romantsova, A.N.; Strepetov, A.N.; Moskaleva, E.Y. Low dose gamma irradiation pretreatment modulates the sensitivity of CNS to subsequent mixed gamma and neutron irradiation of the mouse head. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2021, 97, 926–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jervis, H.R.; McLaughlin, M.M.; Johnson, M.C. Effect of neutron-gamma radiation on the morphology of the mucosa of the small intestine of germfree and conventional mice. Radiat. Res. 1971, 45, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliakis, G.; Ngo, F.Q.; Roberts, W.K.; Youngman, K. Evidence for similarities between radiation damage expressed by beta-araA and damage involved in the interaction effect observed after exposure of V79 cells to mixed neutrons and gamma radiation. Radiat. Res. 1985, 104, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, A.J.; Giusti, V.; Green, S.; Af Rosenschöld, P.M.; Beynon, T.D.; Hopewell, J.W. Interaction between the biological effects of high- and low-LET radiation dose components in a mixed field exposure. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2011, 87, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiakis, E.C.; Canadell, M.P.; Grilj, V.; Harken, A.D.; Garty, G.Y.; Astarita, G.; Brenner, D.J.; Smilenov, L.; Fornace, A.J. Serum lipidomic analysis from mixed neutron/X-ray radiation fields reveals a hyperlipidemic and pro-inflammatory phenotype. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matchuk, O.N.; Yakimova, A.O.; Saburov, V.O.; Koryakin, S.N.; Ivanov, S.A.; Zamulaeva, I.A. Effects of combined action of neutron and proton radiation on the pool of breast cancer stem cells and expression of stemness genes in vitro. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 173, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, F.Q.; Blakely, E.A.; Tobias, C.A. Sequential exposures of mammalian cells to low- and high-LET radiations. I. Lethal effects following X-ray and neon-ion irradiation. Radiat. Res. 1981, 87, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, F.Q.; Blakely, E.A.; Tobias, C.A.; Chang, P.Y.; Lommel, L. Sequential exposures of mammalian cells to low- and high-LET radiations. II. As a function of cell-cycle stages. Radiat. Res. 1988, 115, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.P.; Zaider, M.; Rossi, H.H.; Hall, E.J.; Marino, S.A.; Rohrig, N. The sequential irradiation of mammalian cells with X rays and charged particles of high LET. Radiat. Res. 1983, 93, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenforde, T.S.; Montoya, V.J.; Afzal, S.M.J.; Parr, S.S.; Curtis, S.B. Response of rat rhabdomyosarcoma tumors to split doses of mixed high- and low-LET radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1989, 16, 1529–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizumoto, M.; Tsuboi, K.; Igaki, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Takano, S.; Oshiro, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Hashii, H.; Kanemoto, A.; Nakayama, H.; et al. Phase I/II trial of hyperfractionated concomitant boost proton radiotherapy for supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 77, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J.D.; Yonemoto, L.T.; Mantik, D.W.; Bush, D.A.; Preston, W.; Grove, R.I.; Miller, D.W.; Slater, J.M. Proton radiation for treatment of cancer of the oropharynx: Early experience at Loma Linda University Medical Center using a concomitant boost technique. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2005, 62, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzenrider, J.E.; Liebsch, N.J. Proton therapy for tumors of the skull base. Strahlenther. Und Onkol. 1999, 175, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troshina, M.V.; Koryakina, E.V.; Potetnya, V.I.; Solov’ev, A.N.; Saburov, V.O.; Lychagin, A.A.; Ivanov, S.A.; Kaprin, A.D.; Koryakin, S.N. Biological response of chinese hamster B14-150 cells to sequential combined exposure to protons and 12C ions. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 176, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; De Prado Leal, M.; Dominietto, M.D.; Umbricht, C.A.; Safai, S.; Perrin, R.L.; Egloff, M.; Bernhardt, P.; Van Der Meulen, N.P.; Weber, D.C.; et al. Combination of Proton Therapy and Radionuclide Therapy in Mice: Preclinical Pilot Study at the Paul Scherrer Institute. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuznikova, D.; Klotsotyra, A.; Uhlmann, L.; Domogalla, L.-C.; Steinacker, N.; Mix, M.; Niedermann, G.; Spohn, S.K.B.; Freitag, M.T.; Grosu, A.L.; et al. Exploring the role of combined external beam radiotherapy and targeted radioligand therapy with 177Lu-PSMA-617 for prostate cancer—From bench to bedside. Theranostics 2024, 14, 2560–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryakina, E.V.; Potetnya, V.I.; Troshina, M.V.; Solov’ev, A.N.; Saburov, V.O.; Lychagin, A.A.; Koryakin, S.N.; Ivanov, S.A.; Kaprin, A.D. Post-irradiation recovery of B14-150 fibrosarcoma cells after combined irradiation with low and high linear energy transfer. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 173, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakin, V.E.; Rozanova, O.M.; Smirnova, E.N.; Belyakova, T.A.; Shemyakov, A.E.; Strelnikova, N.S. Combined effect of neutron and proton radiations on the growth of solid ehrlich ascites carcinoma and remote effects in mice. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2021, 498, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryakin, S.N.; Troshina, M.V.; Koryakina, E.V.; Potetnya, V.I.; Pichkunova, A.A.; Saburov, V.O.; Kazakov, E.I.; Lychagin, A.A.; Ivanov, S.A.; Kaprin, A.D.; et al. The study of effectiveness of combined proton—Neutron irradiation of tumor cells in vitro. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2024, 178, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Nieva, P.; González-Vasconcellos, I.; González-Sánchez, L.; Cobos-Fernández, M.A.; Ruiz-García, S.; Sánchez Pérez, R.; Aroca, Á.; Fernández-Piqueras, J.; Santos, J. Differential molecular response in mice and human thymocytes exposed to a combined-dose radiation regime. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Fish, B.L.; Szabo, A.; Schock, A.; Narayanan, J.; Jacobs, E.R.; Moulder, J.E.; Lazarova, Z.; Medhora, M. Enhanced survival from radiation pneumonitis by combined irradiation to the skin. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2014, 90, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reinhold, A.; Glasow, A.; Nürnberger, S.; Weimann, A.; Telemann, L.; Stolzenburg, J.-U.; Neuhaus, J.; Berndt-Paetz, M. Ionizing radiation and photodynamic therapy lead to multimodal tumor cell death, synergistic cytotoxicity and immune cell invasion in human bladder cancer organoids. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2025, 51, 104459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luksiene, Z.; Kalvelyte, A.; Supino, R. On the combination of photodynamic therapy with ionizing radiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1999, 52, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulin, A.-L.; Broekgaarden, M.; Simeone, D.; Hasan, T. Low dose photodynamic therapy harmonizes with radiation therapy to induce beneficial effects on pancreatic heterocellular spheroids. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 2625–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.D.; Nguyen, H.T.; Chen, H.; Cox, P.B.; Wang, L.; Nagata, K.; Hao, Z.; Wang, A.; Li, Z.; Xie, J. X-Ray Induced Photodynamic Therapy: A Combination of Radiotherapy and Photodynamic Therapy. Theranostics 2016, 6, 2295–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazerabadi, A.R.; Sazgarnia, A.; Bahreyni-Toosi, M.H.; Ahmadi, A.; Aledavood, A. The effects of combined treatment with ionizing radiation and indocyanine green-mediated photodynamic therapy on breast cancer cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2012, 109, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.A.; Kappelhoff, J.; Jüstel, T.; Anderson, R.R.; Purschke, M. UV emitting nanoparticles enhance the effect of ionizing radiation in 3D lung cancer spheroids. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2022, 98, 1484–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Wang, Y.; Squillante, M.R.; Held, K.D.; Anderson, R.R.; Purschke, M. UV scintillating particles as radiosensitizer enhance cell killing after X-ray excitation. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 129, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kargar, S.; Khoei, S.; Khoee, S.; Shirvalilou, S.; Mahdavi, S.R. Evaluation of the combined effect of NIR laser and ionizing radiation on cellular damages induced by IUdR-loaded PLGA-coated Nano-graphene oxide. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 21, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, H.D.A.; Mendez, L.C.; Stuart, S.R.; Guimarães, R.G.R.; Ramos, C.C.A.; Paula, L.A.D.; Sales, C.P.D.; Chen, A.T.C.; Blasbalg, R.; Baroni, R.H. Implementation of image-guided brachytherapy (IGBT) for patients with uterine cervix cancer: A tumor volume kinetics approach. J. Contemp. Brachytherapy 2016, 4, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Míguez, C.; Jiménez-Ortega, E.; Palma, B.A.; Miras, H.; Ureba, A.; Arráns, R.; Carrasco-Peña, F.; Illescas-Vacas, A.; Leal, A. Clinical implementation of combined modulated electron and photon beams with conventional MLC for accelerated partial breast irradiation. Radiother. Oncol. 2017, 124, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, F.; Deng, Y.; Li, B.; Ouyang, R.; Miao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y. X-ray and NIR light dual-triggered mesoporous upconversion nanophosphor/Bi heterojunction radiosensitizer for highly efficient tumor ablation. Acta Biomater. 2020, 113, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, F.; Salehi, F.; Karimi, M.; Vais, R.D.; Mosleh-Shirazi, M.A.; Sattarahmady, N. Combined X-ray radiotherapy and laser photothermal therapy of melanoma cancer cells using dual-sensitization of platinum nanoparticles. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020, 203, 111737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Kou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhan, W.; Li, K.; Li, X. Magnetic-guided nanocarriers for ionizing/non-ionizing radiation synergistic treatment against triple-negative breast cancer. Biomed. Eng. Online 2024, 23, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruoka, Y.; Nagaya, T.; Sato, K.; Ogata, F.; Okuyama, S.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Near infrared photoimmunotherapy with combined exposure of external and interstitial light sources. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 3634–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demizu, Y.; Kagawa, K.; Ejima, Y.; Nishimura, H.; Sasaki, R.; Soejima, T.; Yanou, T.; Shimizu, M.; Furusawa, Y.; Hishikawa, Y.; et al. Cell biological basis for combination radiotherapy using heavy-ion beams and high-energy X-rays. Radiother. Oncol. 2004, 71, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Nakano-Aoki, M.; Matsumoto, Y.; Hirayama, R.; Kobayashi, A.; Konishi, T. Equivalency of the quality of sublethal lesions after photons and high-linear energy transfer ion beams. J. Radiat. Res. 2017, 58, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolker, J.D.; Halpern, H.J.; Krishnasamy, S.; Brown, F.; Dohrmann, G.; Ferguson, L.; Hekmatpanah, J.; Mullan, J.; Wollman, R.; Blough, R.; et al. “Instant-mix” whole brain photon with neutron boost radiotherapy for malignant gliomas. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1990, 19, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laramore, G.E.; Diener-west, M.; Griffin, T.W.; Nelson, J.S.; Griem, M.L.; Thomas, F.J.; Hendrickson, F.R.; Griffin, B.R.; Myrianthopoulos, L.C.; Saxton, J. Randomized neutron dose searching study for malignant gliomas of the brain: Results of an RTOG study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1988, 14, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, K.; Koike, S.; Fukuda, N.; Kanehira, C. Independent effect of a mixed-beam regimen of fast neutrons and gamma rays on a murine fibrosarcoma. Radiat. Res. 1984, 98, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiba, S.; Shimo, T.; Yamanaka, M.; Yagihashi, T.; Sakai, M.; Ohno, T.; Tokuuye, K.; Omura, M. Increased cell killing effect in neutron capture enhanced proton beam therapy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinashi, Y.; Yokomizo, N.; Takahashi, S. DNA double-strand breaks induced by fractionated neutron beam irradiation for boron neutron capture therapy. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 1681–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoenix, B.; Green, S.; Hill, M.A.; Jones, B.; Mill, A.; Stevens, D.L. Do the various radiations present in BNCT act synergistically? Cell survival experiments in mixed alpha-particle and gamma-ray fields. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2009, 67, S318–S320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.; Phoenix, B.; Mill, A.J.; Hill, M.; Charles, M.W.; Thompson, J.; Jones, B.; Ngoga, D.; Detta, A.; James, N.D.; et al. The Birmingham Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT) Project: Developments towards Selective Internal Particle Therapy. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 23, S23–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Okumura, K.; Kinashi, Y.; Kubota, Y.; Kitajima, E.; Okayasu, R.; Ono, K.; Takahashi, S. Relative biological effects of neutron mixed-beam irradiation for boron neutron capture therapy on cell survival and DNA double-strand breaks in cultured mammalian cells. J. Radiat. Res. 2013, 54, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam, M.; Kuthala, N.; Kong, X.; Chiang, C.-S.; Hwang, K.C. Combined gadolinium and boron neutron capture therapies for eradication of head-and-neck tumor using Gd10 B6 nanoparticles under MRI/CT image guidance. JACS Au 2023, 3, 2192–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, Y.; Feola, J.M.; Wierzbicki, J. Study of biological effects of varying mixtures of Cf-252 and gamma radiation on the acute radiation syndromes: Relevance to clinical radiotherapy of radioresistant cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1993, 27, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, M.; Meador, J.A.; Cucinotta, F.A.; Gonda, S.R.; Wu, H. Chromosome aberrations induced by dual exposure of protons and iron ions. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2007, 46, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Magpayo, N.; Held, K.D. Targeted and non-targeted effects from combinations of low doses of energetic protons and iron ions in human fibroblasts. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2011, 87, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, P.V.; Cutter, N.C.; Sutherland, B.M. Split-dose exposures versus dual ion exposure in human cell neoplastic transformation. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2007, 46, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Bennett, P.V.; Cutter, N.C.; Sutherland, B.M. Proton-HZE-particle sequential dual-beam exposures increase anchorage-independent growth frequencies in primary human fibroblasts. Radiat. Res. 2006, 166, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiffer, F.; Carr, H.; Groves, T.; Anderson, J.E.; Alexander, T.; Wang, J.; Seawright, J.W.; Sridharan, V.; Carter, G.; Boerma, M.; et al. Effects of 1H +16O charged particle irradiation on short-term memory and hippocampal physiology in a murine model. Radiat. Res. 2018, 189, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiffer, F.; Alexander, T.; Anderson, J.; Groves, T.; McElroy, T.; Wang, J.; Sridharan, V.; Bauer, M.; Boerma, M.; Allen, A. Late Effects of 1H + 16O on Short-Term and Object Memory, Hippocampal Dendritic Morphology and Mutagenesis. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasi, S.P.; Yan, X.; Zuriaga-Herrero, M.; Gee, H.; Lee, J.; Mehrzad, R.; Song, J.; Onufrak, J.; Morgan, J.; Enderling, H.; et al. Different sequences of fractionated low-dose proton and single iron-radiation-induced divergent biological responses in the heart. Radiat. Res. 2017, 188, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raber, J.; Yamazaki, J.; Torres, E.R.S.; Kirchoff, N.; Stagaman, K.; Sharpton, T.; Turker, M.S.; Kronenberg, A. Combined effects of three high-energy charged particle beams important for space flight on brain, behavioral and cognitive endpoints in B6D2F1 female and male mice. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luitel, K.; Kim, S.B.; Barron, S.; Richardson, J.A.; Shay, J.W. Lung cancer progression using fast switching multiple ion beam radiation and countermeasure prevention. Life Sci. Space Res. 2020, 24, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenarczyk, M.; Kronenberg, A.; Mäder, M.; Komorowski, R.; Hopewell, J.W.; Baker, J.E. Exposure to multiple ion beams, broadly representative of galactic cosmic rays, causes perivascular cardiac fibrosis in mature male rats. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Kumar, S.; Kallakury, B.V.S.; Moon, B.-H.; Angdisen, J.; Datta, K.; Fornace, A.J. Predominant contribution of the dose received from constituent heavy-ions in the induction of gastrointestinal tumorigenesis after simulated space radiation exposure. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2022, 61, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishawi, M.; Lee, F.H.; Abraham, D.M.; Glass, C.; Blocker, S.J.; Cox, D.J.; Brown, Z.D.; Rockman, H.A.; Mao, L.; Slaba, T.C.; et al. Late onset cardiovascular dysfunction in adult mice resulting from galactic cosmic ray exposure. iScience 2022, 25, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.; Wong, K.; Talyansky, Y.; Mhatre, S.D.; Mitchell, C.; Juran, C.M.; Olson, M.; Iyer, J.; Puukila, S.; Tahimic, C.G.T.; et al. Sexual dimorphism during integrative endocrine and immune responses to ionizing radiation in mice. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, P.; Trujillo, M.; McElroy, T.; Binz, R.; Pathak, R.; Allen, A.R. Evaluating the effects of low-dose simulated galactic cosmic rays on murine hippocampal-dependent cognitive performance. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 908632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krukowski, K.; Grue, K.; Becker, M.; Elizarraras, E.; Frias, E.S.; Halvorsen, A.; Koenig-Zanoff, M.; Frattini, V.; Nimmagadda, H.; Feng, X.; et al. The impact of deep space radiation on cognitive performance: From biological sex to biomarkers to countermeasures. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, C.; Schroeder, M.K.; Price, B.R.; Khan, K.A.; Curty Da Costa, E.; Hochman-Mendez, C.; Caldarone, B.J.; Lemere, C.A. Long-term, sex-specific effects of GCRsim and gamma irradiation on the brains, hearts, and kidneys of mice with alzheimer’s disease mutations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemec-Bakk, A.S.; Sridharan, V.; Desai, P.; Landes, R.D.; Hart, B.; Allen, A.R.; Boerma, M. Effects of simulated 5-ion galactic cosmic radiation on function and structure of the mouse heart. Life 2023, 13, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puukila, S.; Siu, O.; Rubinstein, L.; Tahimic, C.G.T.; Lowe, M.; Tabares Ruiz, S.; Korostenskij, I.; Semel, M.; Iyer, J.; Mhatre, S.D.; et al. Galactic cosmic irradiation alters acute and delayed species-typical behavior in male and female mice. Life 2023, 13, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, L.D.; Adkins, A.M.; Boden, A.F.; Gotthold, J.D.; Harris, R.D.; Shuboni-Mulligan, D.; Wellman, L.L.; Britten, R.A. Sleep and core body temperature alterations induced by space radiation in rats. Life 2023, 13, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.T.; Kim, J.; Farmerie, L.; Johnson, M.L.; Trovao, N.S.; Arif, S.; Siew, K.; Tsoy, S.; Bram, Y.; Park, J.; et al. Space radiation damage rescued by inhibition of key spaceflight associated miRNAs. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieg, L.; Ciola, J.C.; Wasén, C.C.; Gaba, F.; Colletti, B.R.; Schroeder, M.K.; Hinshaw, R.G.; Ekwudo, M.N.; Holtzman, D.M.; Saito, T.; et al. Cognitive effects of simulated galactic cosmic radiation are mediated by ApoE status, sex, and environment in APP knock-in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, E.; Reid, F.E.; Tamgue, E.N.; Alvarado Arriaga, P.; Nguyen, C.; Britten, R.A. Sex-dependent changes in risk-taking predisposition of rats following space radiation exposure. Life 2025, 15, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.M.; Parihar, V.K.; Szabo, G.G.; Zöldi, M.; Angulo, M.C.; Allen, B.D.; Amin, A.N.; Nguyen, Q.-A.; Katona, I.; Baulch, J.E.; et al. Detrimental impacts of mixed-ion radiation on nervous system function. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 151, 105252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, S.; Liu, A.; Blackwell, A.A.; Britten, R.A. Multiple decrements in switch task performance in female rats exposed to space radiation. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 449, 114465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.W.; Stanbouly, S.; Chieu, B.; Sridharan, V.; Allen, A.R.; Boerma, M. Low dose space radiation-induced effects on the mouse retina and blood-retinal barrier integrity. Acta Astronaut. 2022, 199, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Nikisher, B.; Haran, H.; Tefft, K.; Adams, J.; Edwards, J.G. High throughput screen of small molecules as potential countermeasures to galactic cosmic radiation induced cellular dysfunction. Life Sci. Space Res. 2022, 35, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.; Adams, J.; Tchernikov, A.; Edwards, J.G. Low-dose X-ray radiation induces an adaptive response: A potential countermeasure to galactic cosmic radiation exposure. Exp. Physiol. 2024, EP091350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britten, R.A.; Fesshaye, A.; Tidmore, A.; Blackwell, A.A. Similar loss of executive function performance after exposure to low (10 cGy) doses of single (4He) ions and the multi-ion GCRSim beam. Radiat. Res. 2022, 198, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutros, S.W.; Zimmerman, B.; Nagy, S.C.; Lee, J.S.; Perez, R.; Raber, J. Amifostine (WR-2721) mitigates cognitive injury induced by heavy ion radiation in male mice and alters behavior and brain connectivity. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 770502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.K.; Diak, D.M.; Bustos-Lopez, S.; Nelman-Gonzalez, M.; Chen, X.; Plante, I.; Stray, S.J.; Tandon, R.; Crucian, B.E. Effect of simulated cosmic radiation on cytomegalovirus reactivation and lytic replication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, A.A.; Fesshaye, A.; Tidmore, A.; Lake, I.R.; Wallace, D.G.; Britten, R.A. Rapid loss of fine motor skills after low dose space radiation exposure. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 430, 113907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, J.; Fuentes Anaya, A.; Torres, E.R.S.; Lee, J.; Boutros, S.; Grygoryev, D.; Hammer, A.; Kasschau, K.D.; Sharpton, T.J.; Turker, M.S.; et al. Effects of six sequential charged particle beams on behavioral and cognitive performance in B6D2F1 female and male mice. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keiser, A.A.; Kramár, E.A.; Dong, T.; Shanur, S.; Pirodan, M.; Ru, N.; Acharya, M.M.; Baulch, J.E.; Limoli, C.L.; Wood, M.A. Systemic HDAC3 inhibition ameliorates impairments in synaptic plasticity caused by simulated galactic cosmic radiation exposure in male mice. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2021, 178, 107367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Angdisen, J.; Ma, J.; Datta, K.; Fornace, A.J.; Suman, S. Simulated galactic cosmic radiation exposure-induced mammary tumorigenesis in Apcmin/+ mice coincides with activation of ERα-ERRα-SPP1 signaling axis. Cancers 2024, 16, 3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaghband, Y.; Klein, P.M.; Kramár, E.A.; Cranston, M.N.; Perry, B.C.; Shelerud, L.M.; Kane, A.E.; Doan, N.-L.; Ru, N.; Acharya, M.M.; et al. Galactic cosmic radiation exposure causes multifaceted neurocognitive impairments. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, R.I.; Kangas, B.D.; Luc, O.T.; Solakidou, E.; Smith, E.C.; Dawes, M.H.; Ma, X.; Makriyannis, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Dayeh, M.A.; et al. Complex 33-beam simulated galactic cosmic radiation exposure impacts cognitive function and prefrontal cortex neurotransmitter networks in male mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, E.A.; Blackwell, A.A.; Oltmanns, J.R.O.; Einhaus, R.; Lake, R.; Hein, C.P.; Baulch, J.E.; Limoli, C.L.; Ton, S.T.; Kartje, G.L.; et al. Differential organization of open field behavior in mice following acute or chronic simulated GCR exposure. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 416, 113577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luitel, K.; Siteni, S.; Barron, S.; Shay, J.W. Simulated galactic cosmic radiation-induced cancer progression in mice. Life Sci. Space Res. 2024, 41, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Kiffer, F.C.; Bancroft, G.L.; Guzman, C.S.; Soler, I.; Haas, H.A.; Shi, R.; Patel, R.; Lara-Jiménez, J.; Kumar, P.L.; et al. The longitudinal behavioral effects of acute exposure to galactic cosmic radiation in female C57BL/6J mice: Implications for deep space missions, female crews, and potential antioxidant countermeasures. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e16225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiffer, F.C.; Luitel, K.; Tran, F.H.; Patel, R.A.; Guzman, C.S.; Soler, I.; Xiao, R.; Shay, J.W.; Yun, S.; Eisch, A.J. Effects of a 33-ion sequential beam galactic cosmic ray analog on male mouse behavior and evaluation of CDDO-EA as a radiation countermeasure. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 419, 113677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Moon, B.-H.; Datta, K.; Fornace, A.J.; Suman, S. Simulated galactic cosmic radiation (GCR)-induced expression of Spp1 coincide with mammary ductal cell proliferation and preneoplastic changes in Apc mouse. Life Sci. Space Res. 2023, 36, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riego, M.L.; Meher, P.K.; Brzozowska, B.; Akuwudike, P.; Bucher, M.; Oestreicher, U.; Lundholm, L.; Wojcik, A. Chromosomal damage, gene expression and alternative transcription in human lymphocytes exposed to mixed ionizing radiation as encountered in space. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkikoudi, A.; Manda, G.; Beinke, C.; Giesen, U.; Al-Qaaod, A.; Dragnea, E.-M.; Dobre, M.; Neagoe, I.V.; Sangsuwan, T.; Haghdoost, S.; et al. Synergistic effects of UVB and ionizing radiation on human non-malignant cells: Implications for ozone depletion and secondary cosmic radiation exposure. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.; Perez, R.; Hall, R.; Fallgren, C.M.; Ponnaiya, B.; Garty, G.; Brenner, D.J.; Weil, M.M.; Raber, J. Effects of acute and chronic exposure to a mixed field of neutrons and photons and single or fractionated simulated galactic cosmic ray exposure on behavioral and cognitive performance in mice. Radiat. Res. 2021, 196, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Aoki, M.; Durante, M. Simultaneous exposure of mammalian cells to heavy ions and X-rays. Adv. Space Res. 2002, 30, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokhan, V.S.; Chaprov, K.; Abaimov, D.A.; Nesterov, M.S.; Pikalov, V.A. Combined irradiation by gamma-rays and carbon-12 nuclei caused hyperlocomotion and change in striatal metabolism of rats. Life Sci. Space Res. 2025, 44, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokhina, I.P.; Anokhin, P.K.; Kokhan, V.S. Combined Irradiation by Gamma Rays and Carbon Nuclei Increases the C/EBP-β LIP Isoform Content in the Pituitary Gland of Rats. Dokl. Biol. Sci. 2019, 488, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett-Bakelman, F.E.; Darshi, M.; Green, S.J.; Gur, R.C.; Lin, L.; Macias, B.R.; McKenna, M.J.; Meydan, C.; Mishra, T.; Nasrini, J.; et al. The NASA Twins Study: A multidimensional analysis of a year-long human spaceflight. Science 2019, 364, eaau8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type and Dose | Biological Systems | Biological Endpoints | Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-C (254 nm): 70 erg/mm2; X-rays: 150 rad; irradiations 2–6 h post-PHA stimulation | PHA-stimulated human lymphocytes (G1 stage) | Dicentric and chromatid-type chromosome aberrations (first mitosis) | • No synergistic effect observed • Dicentric yields from combined exposures matched X-rays alone • UV induced only chromatid-type aberrations • Suggests G1 cells possess enhanced repair capacity preventing UV–X-ray interaction | [4] |

| UV-C (253.7 nm): 40–100 erg/mm2; X-rays (260 kV): 125–200 rad; exposures ≤ 30 s apart | Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (unstimulated, G0 stage) | Dicentric chromosome formation (cytogenetic analysis) | • ~2-fold synergistic ↑* in dicentrics vs. X-rays alone • Synergy consistent across UV doses and exposure order • Suggests interaction between X-ray-induced breaks and UV-mediated repair inhibition or lesion overlap | [5] |

| UV-C (254 nm): 65–95 erg/mm2; X-rays (260 kVp): 150 rad; exposures given in sequence with <30 s interval | Human peripheral blood leukocytes from healthy donors; human peripheral blood leukocytes from Down’s syndrome patients | Chromosome aberrations (dicentrics); DNA repair synthesis ([3H]thymidine incorporation) | • ↑ Dicentrics after combined UV + X-rays vs. X-rays alone (2× in controls, 27% in Down’s syndrome) • ↓* UV-induced DNA repair synthesis in Down’s syndrome cells, synergism suggests shared repair pathways | [6] |

| UV-C (254 nm): 6 J/m2; X-rays (260 kVp, 0.5 Gy/min): 1.5 Gy; timing between irradiations varied from <30 s to 90 min | Human peripheral blood lymphocytes in G0 phase | Dicentric chromosome yield per cell | • UV followed by X-rays produced a stable 2-fold ↑ in dicentrics across all timing intervals • X-rays followed by UV showed decreasing synergistic effect with ~20 min half-life • Indicates short-lived DNA lesions responsible for early chromosome exchange events | [7] |

| UV-C (254 nm): 100–175 erg/mm2; X-rays (50 kVp): 450–700 rad; applied sequentially within <40 s; some experiments up to 6 h intervals | Chinese hamster V79 cells (synchronous populations in mid-S-phase) | Cell survival (colony-forming ability) | • Combined exposure resulted in additive ↓ in survival, removal of shoulder in survival curves • Order of exposure modulated effect, with UV preceding X-rays causing greater loss of sublethal damage repair capacity | [8] |

| UV-C (254 nm): up to 1000 ergs/mm2; X-rays (50 kVp): up to ~10 krads/min | E. coli K-12 wild-type; DNA repair mutants (uvrA, uvrB, uvrC, recA, recB, recC, exrA, polA) | Cell survival; DNA single-strand break repair (alkaline sucrose gradients) | • ↑ X-ray sensitivity after UV pretreatment (wild-type and uvr mutants) • UV inhibits type III repair of X-ray-induced DNA SSBs • No synergism in recA, recB, recC, exrA mutants | [9] |

| Near-UV (365 nm): up to 2.5× 106 J/m2; X-rays (250 kVp): up to 19.6 krad (2 krad/min); UV administered ~3–5 min before X-rays | E. coli K12 strains (wild-type W3110, polA mutant P3478, recA recB mutant SR111) | Clonogenic survival; single-strand break rejoining (alkaline sucrose gradients); DNA degradation (TCA-insoluble material) | • Pretreatment with 365 nm UV enhanced X-ray lethality (up to 3.4× slope ↑ in survival curves) • Synergism absent in recA recB mutants • 365 nm inhibited type II and III DNA repair • Full-medium incubation partially restored repair in wild-type and recA recB but not in polA | [10] |

| UV-C (254 nm): up to 960 ergs/mm2; X-rays (150 kVp): up to 40 krads | E. coli B/r and Bs-1 strains; 5-BU substituted DNA and purine-starved cells | Cell survival (colony-forming ability) | • ↑ X-ray sensitivity after UV pretreatment in B/r (up to 3×) • No synergism in 5-BU-substituted or purine-starved cells • UV and 5-BU inhibit X-ray repair • No effect in Bs-1 cells | [11] |

| UV-C (254 nm): 1–120 J/m2; X-rays (100 kVp): 6.7–26.6 krad or alpha particles (4.5 MeV, LET 140–180 keV/μm): 4–48 krad | Diploid Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains (wild-type, rad2 mutant, rad9 mutant) | Colony-forming ability | • ↑ Synergistic loss of colony-forming ability when X-rays precede UV • Reduced UV survival shoulder, altered slopes depending on repair genotype • Synergism absent or reduced in rad2 and rad9 mutants | [12] |

| UV-C (254 nm): 170 J/m2; gamma rays: 90 krad; sequential exposures, no delay | Schizosaccharomyces pombe (wild-type 972h−) and rad1 mutant | Inactivation (colony survival); recovery kinetics | • Strong synergistic interaction in wild-type cells • Survival dropped > 100× beyond additive prediction • No synergism in recombinational repair-deficient rad1 mutant • Recovery kinetics depend on second radiation type, not first | [13] |

| UV-C (253.7 nm): 270–810 J/m2; gamma rays: 0.1–0.3 Mrad; exposures ≤ 5 min apart | Micrococcus radiophilus | Survival/colony-forming ability | • Synergistic killing effect with UV pretreatment (3.5× increased gamma ray sensitivity) • Additive effect with gamma pretreatment | [14] |

| UV-B (300 nm): 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 s exposure time, fixed distance of 50 cm; gamma rays: 500–3000 Gy | Wild-type and mutant Bacillus velezensis strains from soil and oil samples | Functional microbial endpoints: surfactin yield; isoform distribution (MALDI-TOF); antifungal bioactivity (zone of inhibition); emulsification capacity (E24); colony morphology | • Mutant AF-UVγ2500 showed ~2× higher surfactin yield (1.62 g/L vs. 0.85 g/L) • Stronger antifungal activity, 3× isoform abundance • Sequential UV and gamma ray mutagenesis more effective than either treatment alone | [15] |

| Beta particles (32P, internal): time-integrated decay (up to 25 mc/mg P); UV-C (254 nm): 120–530 erg/mm2; exposures sequential with varied timing and order | Salmonella typhimurium strain LM2 | Inactivation (colony-forming ability) | • Strong synergistic effect between 32P decay and UV damage • Reciprocity observed (UV→32P and 32P→UV) • Synergy eliminated by photoreactivation, suggesting interaction between nonlethal DNA lesions (e.g., thymine dimers and 32P-induced strand breaks) within ~25 nucleotide pairs | [16] |

| Electron beam (32 MeV): 21–28 krad; UV-C (254 nm): 450 erg/mm2; exposures ≤ 2 min apart | E. coli B/r | Survival/colony-forming ability | • Synergism observed • Inhibited by 3 h liquid holding between irradiations regardless of order • Attributed to excision repair activity | [17] |

| UV-C (254 nm): 150 ergs/mm2; Protons (LET 20 keV/µm): 8–40 krads | E. coli B/r (wild-type, log-phase) | Survival (loss of reproductive capacity) | • UV pre-exposure sensitized cells to protons • Survival curve slope increased 1.5–1.7× • Synergy not observed when reverse order applied or with other radiation types • Suggests repair system involvement | [18] |

| NIR (600–1400 nm, non-thermal): 360 kJ/m2 (30 min); X-rays (90 kV, 5.23 Gy/min): 1–4 Gy; sequential exposure with NIR pretreatment 30 min before X-rays; temperature-controlled setup | Human full-thickness skin model (primary dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes) | DNA double-strand breaks (53BP1, γH2AX); cell proliferation (BrdU, Ki-67); apoptosis (TUNEL); morphology (H&E) | • NIR pretreatment delayed repair of X-ray-induced DSBs • Protected fibroblasts from apoptosis • Counteracted X-ray-induced proliferation inhibition in keratinocytes • No morphological disruption observed • Photobiomodulation modulated radiation stress response | [19] |

| Low-intensity laser radiation (670 nm): 5.3–16 J/cm2 over 3–4 days, finished 24 h before gamma irradiation; gamma rays (137Cs): 1 or 3 Gy whole-body; | Wistar rats (peripheral blood in vivo) | Cell counts (RBC, WBC, LYM); enzyme activity (SOD, catalase); blood oxygenation | • No synergistic toxicity • Laser pretreatment ↑ leukocyte counts, antioxidant enzyme activity, and oxygenation • Evidence of radioprotective effects from laser pre-irradiation | [20] |

| Type and Dose | Biological Systems | Biological Endpoints | Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UVA (320–400 nm): 0.5, 1, 2 J/cm2; VIS (395–600 nm): 2, 4, 6, 8 J/cm2; Mixed UVB (5%, 310–320 nm est.), UVA (25%, 320–400 nm), visible light (70%, 395–600 nm) = mUV/VIS: 2, 4, 6, 8 J/cm2 (i.e., 0.1–0.4 J/cm2 UVB) | Human volunteers (ragweed-allergic patients, n = 19); forearm skin tested | Skin prick test (SPT) wheal size; allergen-induced immediate hypersensitivity response | • Only mUV/VIS (not UV-A or VIS alone) caused significant, dose-dependent inhibition of allergen-induced wheal formation (up to 83% at 8 J/cm2) • Inhibition occurred even at suberythematous doses • Suggests synergistic action of UV and VIS light on mast cell-mediated response | [21] |

| UV-B (290–320 nm); UV-A (320–400 nm); VIS (400–740 nm); Near-infrared (predominantly IR-A, 760–1400 nm); combined and filtered exposure (natural sunlight fractions) | Human skin tissue (in vivo biopsies) | Photoaging biomarkers (MMP-1, MMP-9, expression, type I procollagen levels), inflammatory cell infiltration (neutrophils, macrophages) | • Full-spectrum sunlight elicited stronger biomarker changes than UV-filtered or heat-only conditions • Composite effects consistent with contributions from multiple spectral components • Enhanced MMP-1 expression, reduced type I procollagen, inflammatory cell infiltration • Neutrophil recruitment required UV, whereas macrophage infiltration also occurred with visible/IR and heat | [22] |

| UV-A (315–400 nm): 25 J/cm2; UV-B (280–315 nm): 0.014 J/cm2, alone and in combinations over 600 days | Albino hairless mice (SKH:HR1 strain) | Tumor induction (SCC, papillomas, solar keratoses); tumor latency (t50); size-specific incidence | • UV-A and UV-B showed additive effects on SCC induction • No significant synergism or antagonism • Papillomas more frequent under UV-A • UV-B enhanced papilloma induction by UV-A | [23] |

| UV-A (379.68 nm): ~11.65 µW/cm2; UV-B (305.22 nm): ~8.65 µW/cm2; 6 h/day exposure for up to 27 days | Scyphozoan jellyfish polyps (Aurelia sp.) | Asexual reproduction (budding rate), survival (mortality), substrate detachment, tentacle condition (retraction/loss), feeding behavior | • Strong synergistic effect: combined UV-A + UV-B caused 100% mortality by day 21 • No budding, total loss of attachment and feeding • UV-B alone reduced reproduction and health • UV-A alone had minimal impact • Combined exposure drastically worsened all outcomes | [24] |

| UV-B (280–315 nm): 1080–3600 J/m2; UV-C (100–280 nm): 280–930 J/m2 | Sclerotinia sclerotiorum; tomato plants | Sclerotia germination; mycelial growth; ROS production; lipid peroxidation; SOD/CAT activity; disease severity; chlorophyll levels; fruit yield; defense gene expression | • Combination had strongest pathogen suppression and yield/quality improvement • ↑* Defense gene expression and antioxidants | [25] |

| UV-A (365 nm): 49 W/m2; UV-B (311 nm): 8 W/m2; simultaneous exposure for 6–8 h/day | E. coli MG1655 (wild-type and mutant strains) | Colony-forming ability; log10 CFU reduction; whole-genome mutations; tRNA photodamage (UVA absorbance, s4U-mediated) | • Strong synergistic inactivation effect (~100× more than UV-B alone) • Synergy traced to thiouridine (s4U) in tRNA absorbing UV-A and impairing protein synthesis, reducing DNA repair • Mutants with ThiI gene alterations lost synergy, confirming mechanistic link | [26] |

| UV-A (365 nm): 600–1200 mJ/cm2; UV-C (268 nm): 2.5–20 mJ/cm2; sequential exposure with UV-A first, intervals 0–24 h; LED-based setup | E. coli K12 MG1655 (wild type) and SP11 (ThiI mutant) | Inactivation (CFU assay), growth delay (OD600), single-cell division time, tRNA photodamage | • Strong synergistic inactivation in wild type (up to 5.7 log10 reduction with UV-C after UV-A) • Effect absent in ThiI mutant lacking s4U tRNA modification • Synergy linked to UV-A-induced translational arrest via tRNA damage • Effect persists up to 24 h post UV-A | [27] |

| UV-LEDs (267 nm, 275 nm, 310 nm): 0.384 mW/cm2; combined exposures (267/275, 267/310, 275/310 nm) matched for irradiance; fluences of 8.78–23.04 mJ/cm2 for 3–4 log inactivation | E. coli (strain CGMCC 1.3373) in water suspension | Inactivation efficiency (log reduction), photoreactivation and dark repair | • No synergistic effect observed for combined wavelengths • 267 nm UV-LED had highest inactivation efficiency • 275 nm showed strongest resistance to reactivation, likely due to protein damage • Photoreactivation was dominant over dark repair | [28] |

| UV-C (222 nm): 0.32 mW/cm2; UV-C (275 nm): 0.50 mW/cm2; delivered simultaneously for 12–20 s | E. coli ATCC 15597 (bacteria) and PR772 (bacteriophage) in PBS suspension | Log10 microbial inactivation; photoreactivation and dark repair; DNA damage; ROS production | • Marked synergistic inactivation of E. coli (synergism coefficient up to 1.92) • No synergism for PR772 • DWUV suppressed photoreactivation in both organisms • Enhanced ROS and protein damage likely mechanism for synergy in bacteria | [29] |

| UV-C (260 nm): 38–122 mJ/cm2; UV-C (280 nm): 41–89 mJ/cm2; UV-C (260|280 nm): 41–105 mJ/cm2 | E. coli, MS2 coliphage, Human adenovirus type 2 (HAdV2), Bacillus pumilus spores | Inactivation kinetics (log10 reduction), DNA/RNA damage (qPCR) | • No synergistic effect observed • Combined 260|280 nm inactivation matched additive sum of individual wavelengths • No enhanced DNA/RNA damage or energy efficiency • Supports fluence-based independence of dual UV wavelengths | [30] |

| UV-C (222 nm): 1.0–2.4 mJ/cm2; UV-C (282 nm): 0.8–2.1 mJ/cm2; fluences for 5-log inactivation: E. coli 2.4–2.6 mJ/cm2, E. faecalis 3.6–5.4 mJ/cm2 | E. coli and Enterococcus faecalis in synthetic water (pH 6.4–7.0) | Log10 microbial inactivation (CFU count); photoreactivation and dark repair | • Strong time-based synergistic effect in all dual-wavelength combinations (φ = 1.3–3.8) • No dose-based synergy • Complete inactivation achieved rapidly • Synergy linked to combined protein damage and DNA damage mechanisms • No repair observed after DWUV exposure | [31] |

| UVA (365 nm): 1.7–52 J/cm2; UVC (265 nm): 4.2–20 mJ/cm2 | E. coli (ATCC 11229) and coliphage MS2 (ATCC 15597-B1) in PBS suspension | Log10 inactivation; photoreactivation and dark repair; ROS-mediated effects (inferred via scavenger assays) | • UV-A pretreatment significantly enhanced UV-C inactivation of E. coli (up to +2.2 log) • Eliminated photoreactivation by impairing self-repair (via hydroxyl radicals inside cells) • No synergy observed for MS2 • Simultaneous UV-A+UV-C decreased E. coli inactivation (photoreactivation effect) | [32] |

| UVA (369 nm), UVB (288 nm), UVC (271 nm), dual UV (288/271 nm, 369/288 nm, 369/271 nm): 0.75–6.75 mJ/cm2 | E. coli, Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. Typhimurium, Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas alcaligenes on agar (simulated food surface) | Log10 inactivation (colony count) | • Significant synergistic effect observed only for 288/271 nm (UV-B/UV-C) on E. coli, S. epidermidis, and S. Typhimurium • Synergy ratios 0.20–0.87 • No synergy with 369/271 or 369/288 combinations • Pulsed and continuous modes equally effective at same dose | [33] |

| UVA-LED (365 nm): 3240 mJ/cm2; UVC-LED (275 nm): 375–750 mJ/cm2, applied sequentially in recirculating water system | E. coli (ATCC 8099) in aquaculture recirculating water | Survival (log inactivation), photoreactivation and dark reactivation rates | • Sequential UVA-UVC irradiation produced ~2–3 log higher inactivation than UVC alone • UVA pretreatment enhanced bactericidal efficacy and reduced bacterial reactivation • Higher UVC doses further suppressed reactivation | [34] |

| UV-A (365 nm): 700 W/m2; UV-C (254 nm): 0.7 W/m2; simultaneous irradiation for 6 min in 96-well plate format | Vibrio parahaemolyticus WT and recA/lexA mutants; cultures in LB broth | DNA damage (CPDs, 8-OHdG); log survival (colony-forming ability); SOS-dependent repair capacity | • Simultaneous UV-A+UV-C caused synergistic bactericidal effect (log survival −3.3) vs. additive effects of single/seq. exposure (−2.1) • CPD repair suppressed • Synergy absent in SOS-deficient mutants, implicating RecA/LexA-dependent repair in survival | [35] |

| UV-C doses: 5–20 mJ/cm2; irradiance: 0.194 mW/cm2 (260 nm), 0.314 mW/cm2 (280 nm), 0.473 mW/cm2 (260/280 combined); simultaneous exposure | Enteroviruses (CVA10, Echo30, PV1, EV70) in water suspension; propagated in BGMK cells | Log10 inactivation (infectivity via ICC-RTqPCR) | • No synergistic effect observed • 260 nm alone was most effective • Dual 260/280 nm either matched or underperformed vs. 260 nm • 280 nm less effective overall • Results consistent with nucleic acid absorption peak near 260 nm | [36] |

| UV-C (222 nm): 0–25 mJ/cm2; UV-C (254 nm): 0–25 mJ/cm2; UV-C (255/265/285 nm): 0–25 mJ/cm2 each | MS2 bacteriophage (virus surrogate) in water suspension (host: E. coli Famp) | Log10 inactivation (PFU count) | • Significant synergy observed for LP or excimer lamps followed by LEDs • Enhanced disinfection vs. additive predictions • Reverse sequences less effective • Excimer + LP sequence showed highest energy efficiency • Supports order-dependent synergy in UV-UV disinfection | [37] |

| UVC (222 nm or 280 nm); 405-nm blue light; pretreatment: 30 s (222-nm: 7.1 mJ/cm2, 280-nm: 1.2 mJ/cm2); 405-nm: up to 48 h, 86.4 J/cm2 | E. coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, S. Typhimurium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (in vitro) | Survival/colony counts; membrane integrity; ROS generation | • Synergistic bactericidal effect on E. coli, L. monocytogenes, S. Typhimurium • Minor for S. aureus • Antagonistic for P. aeruginosa • Synergy linked to ↑ ROS and membrane damage | [38] |

| Type and Dose | Biological Systems | Biological Endpoints | Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha particles (LET 100–238 keV/µm): 0.1–0.2 Gy; X-rays (80 keV): 0.1–0.6 Gy | Human TK6 cells (wild-type and hMYH knockdown) | Clonogenic survival, mutant frequency | • Mixed beams show synergy in wild-type cells (survival) • MYH− cells resistant to survival loss but show high mutant frequency • Oxidative stress role unclear | [39] |

| Alpha particles (241Am, 2.88 MeV, LET ~129 keV/µm): 0.25–2 Gy; X-rays (225 kVp, 0.59 Gy/min): 0.25–3 Gy; applied sequentially with intervals from 15 min to 6 h | PC-3 prostate cancer cells and U2OS osteosarcoma cells | Clonogenic survival | • Sequential mixed-field exposures showed significant sublethal damage repair • RBESLD ~2.8–3.7 • Repair kinetics similar to X-rays • Order of exposure slightly modulated survival at late timepoints | [40] |

| Alpha particles (2.9 MeV, LET ~140 keV/μm, 11–45% of total dose); X-rays (250 kVp, dose rate 0.1 Gy/min); total dose of 1–10 Gy; sequential exposure (alpha then X-ray) | T-1 human kidney cells; aerobic and hypoxic conditions | Clonogenic survival (aerobic and hypoxic conditions) | • Alpha particle irradiation ↑* RBE (~2.3 at 10% survival) and ↓ OER sharply (~1.0) • Mixed radiation ↓ OER further • Observed trends aligned with theory for mixtures of high- and low-LET radiation | [41] |

| Alpha particles (LET 90.9 keV/μm); X-rays (190 keV); 1:1 dose ratio mixed beam (e.g., 1 Gy = 0.5 Gy alpha particles + 0.5 Gy X-rays); total dose of 0.5–2 Gy; simultaneous exposure using custom irradiation setup | Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (from 4 donors) | DNA damage response gene expression (FDXR, GADD45A, MDM2, BBC3, CDKN1A, XPC, qPCR at 24 h post-exposure) | • Mixed beams induced gene expression levels ≥ alpha alone • Synergy detected in 3 of 4 donors using “envelope of additivity” • FDXR most responsive • ATM inhibition decreased response, indicating role in synergistic effect | [42] |

| Alpha particles (LET 90.92 keV/μm): 0.13–0.54 Gy; X-rays (190 kV): 0.20–0.80 Gy; mixed beams included 0.20X + 0.07 alpha, 0.40X + 0.13 alpha, and 0.40X + 0.27 alpha (doses in Gy); simultaneous exposure via dual-source setup | Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) from 1 donor | Chromosomal aberrations (simple vs. complex, via FISH in chromosomes 2, 8, and 14) | • Significant synergistic effect at the level of complex aberrations for two highest mixed doses • Linear-quadratic dose–response for complex events • ↑ damage complexity suggests higher-than-additive biological effect | [43] |

| Alpha particles (LET 97–238 keV/μm): 0.13–1.33 Gy; X-rays (190 kV): 0.25–2.00 Gy; mixed-beam doses: 0.38, 0.77, 1.53 Gy; simultaneous exposure using custom dual-source irradiator at 37 °C | Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (1 male donor) | Micronucleus (MN) frequency in binucleated cells; MN size | • All mixed-beam doses showed statistically significant synergistic effects (average 1.8× higher MN than additive prediction) • Linear dose–response • Synergy attributed to impaired repair of X-ray-induced damage by prior alpha exposure | [44] |

| Alpha particles (LET 100–172 keV/μm): 0–1 Gy; X-rays (80 keV): 0–1 Gy (always 1:1 ratio in mixed exposures) | Human osteosarcoma U2OS cells expressing 53BP1-GFP | DNA double-strand break focus formation and decay (53BP1 foci); ATM and p53 activation | • Strong synergistic interaction observed in both small and large DSB foci • Slower focus decay and prolonged ATM/p53 signaling suggest overwhelmed DNA repair • Synergy most pronounced at lower total doses | [45] |

| Alpha particles (LET 100–238 keV/μm): 0.13–0.32 Gy; X-rays: 0.20–0.80 Gy; mixed beams: 25% alpha + 75% X-rays (e.g., 0.53 Gy ≅ 0.13 alpha + 0.40 X); simultaneous exposure using MAX dual-source system | Human VH10 fibroblasts (immortalized) | γ-H2AX focus formation and repair kinetics (IRIF); small vs. large focus quantification | • No dose–response synergy detected at 1 h • Mixed-beam exposure delayed formation and decay of large foci compared to predicted additive effect, indicating a transient impairment of DNA damage response | [46] |

| Alpha particles (0.223 Gy/min, LET ~91 keV/μm); X-rays (0.052–0.068 Gy/min); total dose of 0–2 Gy; 1:1 ratio in mixed beam; exposures via dual-source platform on blood discs (simultaneous delivery) | Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs, from 3 donors) | DNA damage (alkaline comet assay), repair kinetics, phosphorylated DDR proteins (ATM, DNA-PK, p53), gene expression (qPCR) | • Mixed beams caused significantly more DNA damage than additive prediction (synergy via envelope analysis) • Delayed repair kinetics • Highest activation of DDR proteins and gene expression vs. either radiation alone • Results support synergistic impairment of repair by clustered + dispersed DNA damage | [47] |

| Alpha (LET 100–238 keV/μm); X-rays (peak 80 keV); 0.5 Gy each; simultaneous delivery using a dual-source irradiator | Human osteosarcoma U2OS cells | 53BP1-GFP foci kinetics, area, intensity, mobility (live microscopy), chromatin dynamics | • Mixed-beam foci showed unique dynamic behavior • Intermediate size, highest intensity, low mobility, and persistent signal • Distinct from additive prediction • Results support synergistic effect via impaired repair and complex DSB clustering at chromatin domains | [48] |

| Alpha particles (LET 91 keV/μm); X-rays (190 kV, 3:1 ratio); total dose of 2 Gy, acute or 0.4 Gy × 5 fractionated | Human microglial HMC3 cells; cultured in vitro on Mylar-covered disks | γH2AX foci, CDKN1A and MDM2 expression (qPCR), IL-1β (ELISA), NF-κB/STING phosphorylation, phagocytosis capacity | • Fractionated alpha or alpha + X-ray exposure→stronger pro-inflammatory response and DNA damage signaling than acute • ↑ IL-1β, CDKN1A, MDM2, STING/NF-κB activation, and phagocytosis • Responses returned to baseline by day 14 | [49] |

| Alpha particles (241Am): 0.05–1 Gy; X-rays (150 kVp, 0.356 Gy/min): 0.05–1 Gy | BEAS-2B (human lung epithelial); SVEC4-10EHR1 (mouse endothelial) cells | γ-H2AX foci count, size distribution, and decay (dephosphorylation rate) over 24 h | • Alpha-induced foci were larger and dephosphorylated more slowly than X-ray-induced foci • Radiation type correctly identified in >80% of blinded tests • Individual alpha and X-ray doses estimated within 12% error using mixed-beam exposure data | [50] |

| Alpha particles: 0.166–0.994 Gy; X-rays: 0.25–1.0 Gy; mixed beam 1: 75% X-rays + 25% alpha (0.333–1.327 Gy); mixed beam 2: 50% X-rays + 50% alpha (0.249–0.999 Gy); simultaneous exposure using custom MAX irradiator at 37 °C | Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (AA8) | Clonogenic survival (colony formation assay) | • No synergistic effect observed • Mixed-beam survival data fell within or near predicted additive models • Envelopes of additivity and mathematical modeling confirmed additivity for both mixed-beam conditions | [51] |

| Alpha particle priming doses (LET ~140 keV/μm): 0.5, 2, or 2.5 Gy; X-rays (250 kV, 3 Gy/min): multiple doses up to ~12 Gy; irradiations separated by ≤3–4 min | V79 Chinese hamster lung fibroblast cells | Clonogenic survival | • Sequential exposure with ≤4 min delay showed strong synergistic effect at 2.5 Gy alpha • Survival curve shoulder (Dq) nearly eliminated • X-ray survival curve slope (Do) unchanged • Synergy attributed to alpha-induced damage interfering with sublethal damage repair from X-rays | [52] |

| Alpha particles (5.50 MeV, 0.18 Gy/min): 0–3 Gy; X-rays (280 kVp, 0.75 Gy/min): 0–15 Gy; mixed exposures: 0.06 or 1 Gy alpha + graded X-ray doses | Rat lung epithelial cells (F344, LEC) | Cell survival (clonogenic), micronuclei induction (FISH), mitotic delay | • Simultaneous exposures caused greater-than-additive effects on cell killing and micronuclei frequency • High-dose alpha (1 Gy) removed shoulder from survival curve • Synergistic slopes observed in micronuclei assays even at low alpha dose (0.06 Gy) | [53] |

| Alpha particles (Columbia University charged-particle microbeam): 1 or 20 particles per nucleus; X-rays: 0.02–0.5 Gy pretreatment, 4h before alpha exposure; 3 Gy challenge, 4 h after alpha exposure | Human–hamster hybrid AL cells (CHO–human chromosome 11) | Mutation at CD59 locus (analysis via multiplex PCR) | • Low-dose X-ray priming (0.02–0.1 Gy) suppressed bystander mutagenesis (~58–62% reduction) • 0.5 Gy priming had minimal effect • Bystander cells showed elevated mutant yield after 3 Gy X-ray challenge (supra-additive) • Priming + alpha exposure increased complex CD59− mutation spectrum | [54] |

| Alpha particles (5.50 MeV, 0.223 Gy/min): 0.83 Gy; gamma rays (662 keV, 0.372 Gy/min): 1.02 Gy; total dose of 1.85 Gy; 5 min transfer time between irradiations | U2OS human osteosarcoma cells stably expressing NBS1-GFP | DNA repair foci frequency, size, intensity, and mobility (NBS1-GFP live-cell imaging) | • Stronger synergistic effect observed for α→γ sequence • Slower repair kinetics, larger and more persistent foci • ↑ Intensity and ↓ mobility • γ→α induced faster decay and lower focus intensity • Results suggest order-dependent DDR engagement and impaired repair after alpha priming | [55] |

| Alpha particles (LET ~91 keV/μm): 2.5 Gy; gamma rays (0.73 Gy/min): 2.5 Gy; fractionated regimens used as well | Breast cancer (MDA-MB-231), Osteosarcoma (U2OS) | γH2AX foci (TEM, immunofluorescence), colony formation, viability | • Mixed beam causes more γH2AX foci • Stronger reduction in viability/colony formation • Delayed chromatin recompaction enhances cell kill | [56] |

| Alpha (LET ~126 keV/μm, 50 rad/min): ~25% of total dose; gamma (LET ~0.31 keV/μm, 154 rad/min): ~75% of total dose | Diploid yeast (S. cerevisiae, strain BZ34) | Mutation frequency (reversion to arginine independence) | • Statistically significant synergistic effect observed • Reversion frequency 1.34× higher than additive prediction • Enhanced mutagenic effect attributed to interaction between low- and high-LET damage pathways | [57] |

| Alpha, beta, and gamma radiation (mixed radionuclides from Chernobyl fallout including 134Cs, 137Cs, 144Ce, 154Eu, etc.): total dose 1–515 mSv (chronic); gamma rays (60Co source): 0.1–29, 600 mSv (chronic) | Barley (Hordeum vulgare, waxy mutant line); field-grown in contaminated plots and gamma-field controls | Waxy-reversion frequency in haploid pollen; mutation frequency in generative cells | • Combined radionuclide IR caused higher mutation rates per mSv than external gamma • Mutagenicity not explained by dose alone • Enhanced genotoxicity linked to multi-type exposure, chemical synergies, and heterogeneous contamination | [58] |

| Beta (90Sr-90Y, low LET): 1.2–4.8 krad; gamma rays (60Co, low LET): 1.2–4.8 krad; beta and gamma combined (varied proportions): total 1.2–4.8 krad at 8.4 or 17.8 rad/min | Soybean plants (Glycine max cv. Hill) at unifoliolate leaf stage; grown to maturity in field | Survival, plant height, lateral growth frequency and length, vegetative yield, seed yield | • Combined exposure affected lateral growth and yield depending on beta/gamma dose component • Gamma slightly more damaging overall • Interaction effects seen in vegetative vs. reproductive response • Dose-rate and composition sensitivity evident | [59] |