Molecular Evolution of the NLR Gene Family Reveals Diverse Innate Immune Strategies in Bats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genome Data Collection and Sequence Alignment

2.2. Molecular Evolution Analysis

2.3. Protein Three-Dimensional Structure Prediction

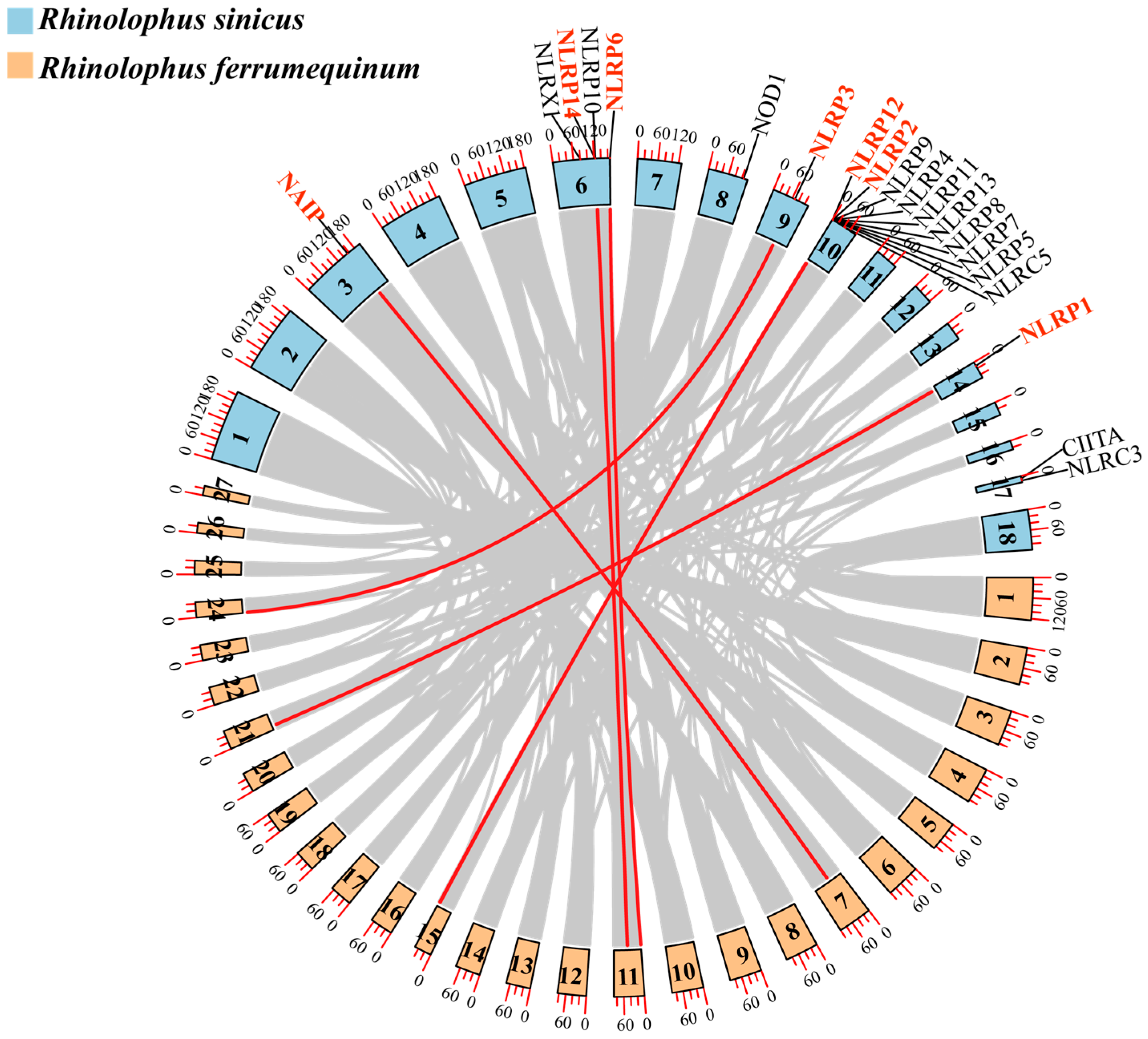

2.4. Collinearity Analysis

3. Results

3.1. NLR Gene Identification and Gene Tree Reconstruction

3.2. Evolutionary Selection Characteristics of NLR Genes

3.3. Prediction of the Three-Dimensional Structure of NLR Gene Proteins and Positive Selection Site Marking

3.4. NLR Gene Family Collinearity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janeway, C.A., Jr. Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1989, 54 Pt 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchi, L.; Warner, N.; Viani, K.; Nuñez, G. Function of Nod-like receptors in microbial recognition and host defense. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 227, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chai, J. Molecular actions of NLR immune receptors in plants and animals. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 1303–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Coveney, A.P.; Wu, M.; Huang, J.; Blankson, S.; Zhao, H.; O’Leary, D.P.; Bai, Z.; Li, Y.; Redmond, H.P.; et al. Activation of Both TLR and NOD Signaling Confers Host Innate Immunity-Mediated Protection Against Microbial Infection. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, B.R. Structure of fish Toll-like receptors (TLR) and NOD-like receptors (NLR). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1602–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiserlian, D.; Cerf-Bensussan, N.; Hosmalin, A. The mucosal immune system: From control of inflammation to protection against infections. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005, 78, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, S.W.; Bonham, K.S.; Zanoni, I.; Kagan, J.C. Innate immune pattern recognition: A cell biological perspective. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 33, 257–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broz, P.; Dixit, V.M. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, E.; Broz, P. Evolutionary Convergence and Divergence in NLR Function and Structure. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velloso, F.J.; Trombetta-Lima, M.; Anschau, V.; Sogayar, M.C.; Correa, R.G. NOD-like receptors: Major players (and targets) in the interface between innate immunity and cancer. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20181709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paerewijck, O.; Lamkanfi, M. The human inflammasomes. Mol. Asp. Med. 2022, 88, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, Z.; Yu, L.; Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J. Nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors in teleost fish: Current knowledge and future perspectives. J. Fish Dis. 2018, 41, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.X.; Xiong, F.; Wu, X.M.; Hu, Y.W. The expanding and function of NLRC3 or NLRC3-like in teleost fish: Recent advances and novel insights. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2021, 114, 103859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Cao, L.; Jiang, C.; Che, Y.; Zhang, S.; Takahashi, S.; Wang, G.; Gonzalez, F.J. Farnesoid X Receptor Regulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Underlies Cholestasis-Associated Sepsis. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 856–867.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmanski, J.M.; Petnicki-Ocwieja, T.; Kobayashi, K.S. NLR proteins: Integral members of innate immunity and mediators of inflammatory diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008, 83, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, J.P.; Willingham, S.B.; Bergstralh, D.T. NLRs at the intersection of cell death and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Rehman, N.; Fakhar Zaman, F.; Naeem, M.K.; Jamal, A.; Tellier, A.; Ilyas, M.; Silva Arias, G.A.; Khan, M.R. Genome-wide characterization of the NLR gene family in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and their relatedness to disease resistance. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 931580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Kim, S.; Yeom, S.I.; Choi, D. Genome-wide comparative analyses reveal the dynamic evolution of nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat gene family among Solanaceae plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, S.; Peng, Q.; Liu, W.; Yan, J.; Cai, J.; Xie, D.; Jiang, B.; Lin, Y.; et al. Genome-wide identification and comparative analyses of NLR gene families in Cucumis sativus and its related species. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 351, 114382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Chen, Q.; Liu, W.; Li, T.; Ji, T. Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Evolution of NLR Gene Family in Capsicum annuum. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhai, W.; Song, R.; Ning, H.; Li, S.; Gao, W.J. Comparative analysis of the NLR gene family in the genomes of garden asparagus (Asparagus officinalis) and its wild relatives. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1681919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Baker, M.L.; Kulcsar, K.; Misra, V.; Plowright, R.; Mossman, K. Novel insights into immune systems of bats. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zeng, J.; Jiao, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L.; Lei, C.Q.; Rossiter, S.J.; Zhao, H. Comparative analyses of bat genomes identify distinct evolution of immunity in Old World fruit bats. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd0141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papenfuss, A.T.; Baker, M.L.; Feng, Z.P.; Tachedjian, M.; Crameri, G.; Cowled, C.; Ng, J.; Janardhana, V.; Field, H.E.; Wang, L.F. The immune gene repertoire of an important viral reservoir, the Australian black flying fox. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggadone, M.D.; Grailer, J.J.; Fattahi, F.; Zetoune, F.S.; Ward, P.A. Bidirectional Crosstalk between C5a Receptors and the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Macrophages and Monocytes. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 1340156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerard, N.P.; Lu, B.; Liu, P.; Craig, S.; Fujiwara, Y.; Okinaga, S.; Gerard, C. An anti-inflammatory function for the complement anaphylatoxin C5a-binding protein, C5L2. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 39677–39680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scola, A.M.; Johswich, K.O.; Morgan, B.P.; Klos, A.; Monk, P.N. The human complement fragment receptor, C5L2, is a recycling decoy receptor. Mol. Immunol. 2009, 46, 1149–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Pascal, G.; Monget, P. Evolution and functional divergence of NLRP genes in mammalian reproductive systems. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, W.J.; Vacquier, V.D. The rapid evolution of reproductive proteins. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.L.; Aagaard, J.E.; Swanson, W.J. Evolution of reproductive proteins from animals and plants. Reproduction 2006, 131, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, G.; Ma, L.; Shi, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhan, X.; Qin, N.; He, T.; Guo, Y.; Niu, M.; et al. Icariside I specifically facilitates ATP or nigericin-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and causes idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity. Cell Commun. Signal.: CCS 2021, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Ding, H.; Li, Y.; Pearson, J.A.; Zhang, X.; Flavell, R.A.; Wong, F.S.; Wen, L. NLRP3 deficiency protects from type 1 diabetes through the regulation of chemotaxis into the pancreatic islets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11318–11323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Li, Y.; Yao, X.; Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Sun, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhong, L.; et al. Identification of key proteins of cytopathic biotype bovine viral diarrhoea virus involved in activating NF-κB pathway in BVDV-induced inflammatory response. Virulence 2022, 13, 1884–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenster, L.M.; Lange, K.E.; Normann, S.; vom Hemdt, A.; Wuerth, J.D.; Schiffelers, L.D.J.; Tesfamariam, Y.M.; Gohr, F.N.; Klein, L.; Kaltheuner, I.H.; et al. P38 kinases mediate NLRP1 inflammasome activation after ribotoxic stress response and virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 2023, 220, e20220837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsu, B.V.; Beierschmitt, C.; Ryan, A.P.; Agarwal, R.; Mitchell, P.S.; Daugherty, M.D. Diverse viral proteases activate the NLRP1 inflammasome. eLife 2021, 10, e60609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, R.; Tsakem Lenou, E.; Basrur, V.; Kontoyiannis, D.L.; Ioakeimidis, F.; Mosialos, G.; Theiss, A.L.; Flavell, R.A.; Venuprasad, K. Deubiquitination of NLRP6 inflammasome by Cyld critically regulates intestinal inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Wen, H.; Yu, Y.; Taxman, D.J.; Zhang, L.; Widman, D.G.; Swanson, K.V.; Wen, K.W.; Damania, B.; Moore, C.B.; et al. The mitochondrial proteins NLRX1 and TUFM form a complex that regulates type I interferon and autophagy. Immunity 2012, 36, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Wen, H.; Ting, J.P. The NLR protein, NLRX1, and its partner, TUFM, reduce type I interferon, and enhance autophagy. Autophagy 2013, 9, 432–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchimura, T.; Oyama, Y.; Deng, M.; Guo, H.; Wilson, J.E.; Rampanelli, E.; Cook, K.D.; Misumi, I.; Tan, X.; Chen, L.; et al. The Innate Immune Sensor NLRC3 Acts as a Rheostat that Fine-Tunes T Cell Responses in Infection and Autoimmunity. Immunity 2018, 49, 1049–1061.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Mo, J.; Swanson, K.V.; Wen, H.; Petrucelli, A.; Gregory, S.M.; Zhang, Z.; Schneider, M.; Jiang, Y.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. NLRC3, a member of the NLR family of proteins, is a negative regulator of innate immune signaling induced by the DNA sensor STING. Immunity 2014, 40, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.Y.; Chen, K.R.; Li, Y.C.; Kuo, P.L. NLRP7 Is Involved in the Differentiation of the Decidual Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, F.; Kodani, M.; Emori, C.; Kiyozumi, D.; Mori, M.; Fujihara, Y.; Ikawa, M. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing Reveals Oosp Family Genes are Dispensable for Female Fertility in Mice. Cells 2020, 9, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soellner, L.; Begemann, M.; Degenhardt, F.; Geipel, A.; Eggermann, T.; Mangold, E. Maternal heterozygous NLRP7 variant results in recurrent reproductive failure and imprinting disturbances in the offspring. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG 2017, 25, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Li, R.; Negro, R.; Cheng, J.; Vora, S.M.; Fu, T.M.; Wang, A.; He, K.; Andreeva, L.; Gao, P.; et al. Phase separation drives RNA virus-induced activation of the NLRP6 inflammasome. Cell 2021, 184, 5759–5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Ding, S.; Wang, P.; Wei, Z.; Pan, W.; Palm, N.W.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, H.B.; Wang, G.; et al. Nlrp9b inflammasome restricts rotavirus infection in intestinal epithelial cells. Nature 2017, 546, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, B.; Chen, J. NLRP9 in innate immunity and inflammation. Immunology 2021, 162, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marleaux, M.; Anand, K.; Latz, E.; Geyer, M. Crystal structure of the human NLRP9 pyrin domain suggests a distinct mode of inflammasome assembly. FEBS Lett. 2020, 594, 2383–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrent, L.; Juste, J.; Garin, I.; Aihartza, J.; Dalton, D.L.; Mamba, M.; Tanshi, I.; Powell, L.L.; Padidar, S.; Garcia Mudarra, J.L.; et al. Taxonomic revision of African pipistrelle-like bats with a new species from the West Congolean rainforest. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2025, 204, zlaf020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pan, Y.F.; Yang, L.F.; Yang, W.H.; Lv, K.; Luo, C.M.; Wang, J.; Kuang, G.P.; Wu, W.C.; Gou, Q.Y.; et al. Individual bat virome analysis reveals co-infection and spillover among bats and virus zoonotic potential. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Wang, Y.; Lü, L.; Jiang, C.; Ahmad, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, D. Bats and birds as viral reservoirs: A physiological and ecological perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.; To, K.K.; Tse, H.; Jin, D.Y.; Yuen, K.Y. Interspecies transmission and emergence of novel viruses: Lessons from bats and birds. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollentze, N.; Streicker, D.G. Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9423–9430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, E.M.; Kumulungui, B.; Pourrut, X.; Rouquet, P.; Hassanin, A.; Yaba, P.; Délicat, A.; Paweska, J.T.; Gonzalez, J.P.; Swanepoel, R. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 2005, 438, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, B.A.; Wang, L.F.; Marsh, G.A. Henipaviruses: An updated review focusing on the pteropid reservoir and features of transmission. Zoonoses Public Health 2013, 60, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Shi, Z.; Yu, M.; Ren, W.; Smith, C.; Epstein, J.H.; Wang, H.; Crameri, G.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science 2005, 310, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, H.A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) origin and animal reservoir. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, M.J.; Bermejo-Martin, J.F.; Danesh, A.; Muller, M.P.; Kelvin, D.J. Human immunopathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Virus Res. 2008, 133, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Speranza, E.; Muñoz-Fontela, C.; Haldenby, S.; Rickett, N.Y.; Garcia-Dorival, I.; Fang, Y.; Hall, Y.; Zekeng, E.G.; Lüdtke, A.; et al. Transcriptomic signatures differentiate survival from fatal outcomes in humans infected with Ebola virus. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totura, A.L.; Baric, R.S. SARS coronavirus pathogenesis: Host innate immune responses and viral antagonism of interferon. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampieri, C.A.; Sullivan, N.J.; Nabel, G.J. Immunopathology of highly virulent pathogens: Insights from Ebola virus. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Gonzalez, G.; Sheng, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, F.; Xu, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, A.; Qu, Y.; Tu, C.; et al. Extensive Genetic Diversity of Polyomaviruses in Sympatric Bat Communities: Host Switching versus Coevolution. J. Virol. 2020, 94, 101128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Yang, X.; Ren, Z.; Hu, B.; Zhao, H.; Yang, K.; Shi, P.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, Q.; Nawenja, C.V.; et al. Substantial viral diversity in bats and rodents from East Africa: Insights into evolution, recombination, and cocirculation. Microbiome 2024, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, P.; Han, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Lu, J.; Daszak, P.; et al. Unveiling bat-borne viruses: A comprehensive classification and analysis of virome evolution. Microbiome 2024, 12, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Dong, T.; Chen, H.; Wu, C.; Su, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, W.; et al. Bat-infecting merbecovirus HKU5-CoV lineage 2 can use human ACE2 as a cell entry receptor. Cell 2025, 188, 1729–1742.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinne, A.; Hu, B.; Olival, K.J.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, L.B.; Li, H.; Chmura, A.A.; Field, H.E.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Epstein, J.H.; et al. Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.R.; Wu, K.; Su, J.; Dong, T.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, Z.L.; Zhou, P. Individual virome analysis reveals the general co-infection of mammal-associated viruses with SARS-related coronaviruses in bats. Virol. Sin. 2024, 39, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, T.B.; Li, A.; Biswas, A.; Lee, K.H.; Liu, Y.J.; Bayir, E.; Iliopoulos, D.; van den Elsen, P.J.; Kobayashi, K.S. NLR family member NLRC5 is a transcriptional regulator of MHC class I genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 13794–13799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wu, X.; Shang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, H. Adaptive evolution of the OAS gene family provides new insights into the antiviral ability of laurasiatherian mammals. Animals 2023, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, B.R.C.; dos Santos, L.K.C.; Ferreira, J.M.; dos Santos, A.C.M.; Sortica, V.A.; de Souza Figueiredo, E.V.M. Toll-like receptors polymorphisms and COVID-19: A systematic review. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2025, 480, 2677–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.E.; Dong, Y.; Brown, T.; Baid, K.; Kontopoulos, D.; Gonzalez, V.; Huang, Z.; Ahmed, A.W.; Bhuinya, A.; Hilgers, L.; et al. Bat genomes illuminate adaptations to viral tolerance and disease resistance. Nature 2025, 638, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Qiao, F.; Yang, B.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wulff, B.B.H.; Hu, P.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, R.; Chen, P.; et al. Genome-wide identification of the NLR gene family in Haynaldia villosa by SMRT-RenSeq. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, F. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the NLR gene family in Medicago ruthenica. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1088763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, F.; Mehmood, A.; Khan, S.A.; Bilal, M.; Urooj, F.; Alyas, M.; Ijaz, J.; Zain, M.; Noreen, F.; Rani, S.; et al. Macroevolution of NLR genes in family Fabaceae provides evidence of clade specific expansion and contraction of NLRome in Vicioid clade. Plant Stress. 2023, 10, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, H.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Cai, J.; Huang, G. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the Nucleotide-Binding Leucine-Rich Repeat Gene Families in Rubber Tree. Phytopathology 2025, 1943–7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Madden, T.L.; Schäffer, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Miller, W.; Lipman, D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 3389–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhuang, L.; He, J. Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of the AIG Family in Vertebrates. Genes 2021, 12, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccolo, J.; Bau, J.; Childs, S.J.; Goss, G.G.; Sensen, C.W.; Deans, J.P. Phylogenetic Analysis of the MS4A and TMEM176 Gene Families. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wong, W.S.; Nielsen, R. Bayes empirical bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005, 22, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007, 24, 1586–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Amparo, R.; Branco, C.; Arenas, J.; Vicens, A.; Arenas, M. Analysis of selection in protein-coding sequences accounting for common biases. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashbrooke, J.; Adato, A.; Lotan, O.; Alkan, N.; Tsimbalist, T.; Rechav, K.; Fernandez-Moreno, J.P.; Widemann, E.; Grausem, B.; Pinot, F.; et al. The Tomato MIXTA-Like Transcription Factor Coordinates Fruit Epidermis Conical Cell Development and Cuticular Lipid Biosynthesis and Assembly. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 2553–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Dong, Y.; Sun, G.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Gao, X.; Sha, W.; Yang, G.; Zhang, H. FGF gene family characterization provides insights into its adaptive evolution in Carnivora. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 9837–9847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Shang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, H. Evolutionary Impacts of Pattern Recognition Receptor Genes on Carnivora Complex Habitat Stress Adaptation. Animals 2022, 12, 3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pond, S.L.K.; Frost, S.D.W. Datamonkey: Rapid detection of selective pressure on individual sites of codon alignments. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 2531–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Nielsen, R.; Yang, Z. Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005, 22, 2472–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.L.; Dunn, K.A.; Mingrone, J.; Wood, B.A.; Karpinski, B.A.; Sherwood, C.C.; Wildman, D.E.; Maynard, T.M.; Bielawski, J.P. Functional Divergence of the Nuclear Receptor NR2C1 as a Modulator of Pluripotentiality During Hominid Evolution. Genetics 2016, 203, 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D493–D496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Kucukural, A.; Zhang, Y. I-TASSER: A unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, P.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, P.; Li, L.; et al. PCBP2 maintains antiviral signaling homeostasis by regulating cGAS enzymatic activity via antagonizing its condensation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Ma, L.; Yan, C.; Wang, H.; Ran, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Liang, X.; Chai, L.; Li, X. Mouse Ocilrp2/Clec2i negatively regulates LPS-mediated IL-6 production by blocking Dap12-Syk interaction in macrophage. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 984520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Pardo Manuel de Villena, F.; McMillan, L.; Wang, W. GeneScissors: A comprehensive approach to detecting and correcting spurious transcriptome inference owing to RNA-seq reads misalignment. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, i291–i299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisu, C.; Muir, P.; Frankish, A.; Fiddes, I.; Diekhans, M.; Thybert, D.; Odom, D.T.; Flicek, P.; Keane, T.M.; Hubbard, T.; et al. Transcriptional activity and strain-specific history of mouse pseudogenes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, F.; Muzio, M. Updates on Toll-Like Receptor 10 Research. Eur. J. Immunol. 2025, 55, e202551840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Luo, R.; Lan, J.; Lu, Z.; Qiu, H.J.; Wang, T.; Sun, Y. The Multigene Family Genes-Encoded Proteins of African Swine Fever Virus: Roles in Evolution, Cell Tropism, Immune Evasion, and Pathogenesis. Viruses 2025, 17, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Minias, P.; Dunn, P.O. Long-Read Genome Assemblies Reveal Extraordinary Variation in the Number and Structure of MHC Loci in Birds. Genome Biol. Evol. 2020, 13, evaa270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, N.P.; Wafula, E.K.; Timilsena, P.R.; Ralph, P.E.; Maximova, S.N.; dePamphilis, C.W.; Guiltinan, M.J.; Marden, J.H. Local gene duplications drive extensive NLR copy number variation across multiple genotypes of Theobroma cacao. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2025, 15, jkaf147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Jin, Y.; Xu, X.; Han, G.Z. Extent and evolution of gene duplication in DNA viruses. Virus Res. 2017, 240, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Loriere, E.; Holmes, E.C. Gene duplication is infrequent in the recent evolutionary history of RNA viruses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, C.E.J.C.m.r. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 778–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, A. Identification of the carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase genes and functional analysis reveal DoCCD1 is potentially involved in beta-ionone formation in Dendrobium officinale. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 967819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barribeau, S.M.; Sadd, B.M.; du Plessis, L.; Brown, M.J.; Buechel, S.D.; Cappelle, K.; Carolan, J.C.; Christiaens, O.; Colgan, T.J.; Erler, S.; et al. A depauperate immune repertoire precedes evolution of sociality in bees. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I.C.; Scull, M.A.; Moore, C.B.; Holl, E.K.; McElvania-TeKippe, E.; Taxman, D.J.; Guthrie, E.H.; Pickles, R.J.; Ting, J.P. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity 2009, 30, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirel, I.; Persson, A.; Brauner, A.; Särndahl, E.; Kruse, R.; Persson, K. Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway by Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Is Virulence Factor-Dependent and Influences Colonization of Bladder Epithelial Cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Bentley, J.K.; Rajput, C.; Lei, J.; Ishikawa, T.; Jarman, C.R.; Lee, J.; Goldsmith, A.M.; Jackson, W.T.; Hoenerhoff, M.J.; et al. Inflammasome activation is required for human rhinovirus-induced airway inflammation in naive and allergen-sensitized mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2019, 12, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.N.; Pascarella, A.; Licursi, V.; Caiello, I.; Taranta, A.; Rega, L.R.; Levtchenko, E.; Emma, F.; De Benedetti, F.; Prencipe, G. NLRP2 Regulates Proinflammatory and Antiapoptotic Responses in Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heluany, C.S.; Donate, P.B.; Schneider, A.H.; Fabris, A.L.; Gomes, R.A.; Villas-Boas, I.M.; Tambourgi, D.V.; Silva, T.A.D.; Trossini, G.H.G.; Nalesso, G.; et al. Hydroquinone Exposure Worsens Rheumatoid Arthritis through the Activation of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and Interleukin-17 Pathways. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Bai, J.; Gao, Y.; Jin, L.; Wang, X.; Cao, M.; Liu, X.; Jiang, P. Peroxiredoxin 1 Interacts with TBK1/IKKε and Negatively Regulates Pseudorabies Virus Propagation by Promoting Innate Immunity. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0092321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, A.; Speen, A.M.; Kim, H.H.; Hoffman, J.R.; Clapp, P.W.; Rivera Martin, W.; Snouwaert, J.N.; Koller, B.H.; Porter, N.A.; Jaspers, I. Oxysterols Modify NLRP2 in Epithelial Cells, Identifying a Mediator of Ozone-induced Inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 65, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Behlke, M.A.; Apicella, M.A.; McCray, P.B., Jr.; Davidson, B.L. Platelet Activating Factor Receptor Activation Improves siRNA Uptake and RNAi Responses in Well-differentiated Airway Epithelia. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2014, 3, e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Delgado, M.; Martin-Trujillo, A.; Tayama, C.; Vidal, E.; Esteller, M.; Iglesias-Platas, I.; Deo, N.; Barney, O.; Maclean, K.; Hata, K.; et al. Absence of Maternal Methylation in Biparental Hydatidiform Moles from Women with NLRP7 Maternal-Effect Mutations Reveals Widespread Placenta-Specific Imprinting. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Deng, Y.; Hou, L.; Fan, X.; Lin, L.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, K.; Sun, C. Genipin Ameliorates Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Injury in Mice via the Concomitant Inhibition of Inflammation and Induction of Autophagy. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 3729051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, T.; Wu, X.; An, P.; Wu, X.; Dang, H. Autophagy in the HTR-8/SVneo Cell Oxidative Stress Model Is Associated with the NLRP1 Inflammasome. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 2353504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Sheng, C.; Gao, S.; Yao, C.; Li, J.; Jiang, W.; Chen, H.; Wu, J.; Pan, C.; Chen, S.; et al. SOCS3 Drives Proteasomal Degradation of TBK1 and Negatively Regulates Antiviral Innate Immunity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015, 35, 2400–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Juliana, C.; Hong, S.; Datta, P.; Hwang, I.; Fernandes-Alnemri, T.; Yu, J.W.; Alnemri, E.S. The mitochondrial antiviral protein MAVS associates with NLRP3 and regulates its inflammasome activity. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 4358–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangopadhyay, A.; Devi, S.; Tenguria, S.; Carriere, J.; Nguyen, H.; Jäger, E.; Khatri, H.; Chu, L.H.; Ratsimandresy, R.A.; Dorfleutner, A.; et al. NLRP3 licenses NLRP11 for inflammasome activation in human macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begemann, M.; Rezwan, F.I.; Beygo, J.; Docherty, L.E.; Kolarova, J.; Schroeder, C.; Buiting, K.; Chokkalingam, K.; Degenhardt, F.; Wakeling, E.L.; et al. Maternal variants in NLRP and other maternal effect proteins are associated with multilocus imprinting disturbance in offspring. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 55, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Cao, S.; Fu, H.; Fan, X.; Xiong, J.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Xie, K.; Meng, T.G.; Liu, Y.; et al. A noncanonical role of NOD-like receptor NLRP14 in PGCLC differentiation and spermatogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 22237–22248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.N.; Zhang, T.; Gao, W.Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.B.; Cai, J.Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, C.R.; Chen, X.C.; Zeng, W.T.; et al. Fam70A binds Wnt5a to regulate meiosis and quality of mouse oocytes. Cell Prolif. 2020, 53, e12825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubínová, D.; Irwin, N.; Hulva, P.; Koubek, P.; Zima, J. Hidden diversity in Senegalese bats and associated findings in the systematics of the family Vespertilionidae. Front. Zool. 2013, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L.; Shi, B.; Wu, H.; Feng, J.; Jiang, T. Who’s for dinner? Bird prey diversity and choice in the great evening bat, Ia io. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 8400–8409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Geng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lin, A.; Wu, H.; Feng, L.; Huang, Z.; Wu, H.; Feng, J.; Jiang, T. Behavioral innovation and genomic novelty are associated with the exploitation of a challenging dietary opportunity by an avivorous bat. iScience 2022, 25, 104973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Gu, H.; Chang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, B.; Lin, A.; Wu, H.; Feng, J.; Jiang, T. Seasonal variation of population and individual dietary niche in the avivorous bat, Ia io. Oecologia 2023, 201, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, F.; Behrens, M. Bitter taste receptors of the common vampire bat are functional and show conserved responses to metal ions in vitro. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2021, 288, 20210418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ke, C.; Feng, J.; He, B.; Jiang, T. The links between dietary diversity and RNA virus diversity harbored by the great evening bat (Ia io). Microbiome 2024, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moecking, J.; Laohamonthonkul, P.; Chalker, K.; White, M.J.; Harapas, C.R.; Yu, C.H.; Davidson, S.; Hrovat-Schaale, K.; Hu, D.; Eng, C.; et al. NLRP1 variant M1184V decreases inflammasome activation in the context of DPP9 inhibition and asthma severity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 2134–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Colchicine in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertheim, J.O.; Murrell, B.; Smith, M.D.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Scheffler, K. RELAX: Detecting Relaxed Selection in a Phylogenetic Framework. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 32, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Zhong, Z.; Zeng, F.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Ren, W.; Yang, G.; Wang, H.; Xu, S. Evolution of canonical circadian clock genes underlies unique sleep strategies of marine mammals for secondary aquatic adaptation. PLOS Genet. 2025, 21, e1011598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.S.; Bergland, A.O. Patterns of Gene Family Evolution and Selection Across Daphnia. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ng, Y.K.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Shen, B.; Li, S.C. GeneFamily: A comprehensive mammalian gene family database with extensive annotation and interactive visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, gkaf1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancaldi, F.; van Loo, E.N.; Schranz, M.E.; Trindade, L.M. Genomic Architecture and Evolution of the Cellulose synthase Gene Superfamily as Revealed by Phylogenomic Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itan, Y.; Shang, L.; Boisson, B.; Patin, E.; Bolze, A.; Moncada-Vélez, M.; Scott, E.; Ciancanelli, M.J.; Lafaille, F.G.; Markle, J.G.; et al. The human gene damage index as a gene-level approach to prioritizing exome variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA 2015, 112, 13615–13620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespi, B. Evolutionary medical insights into the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Evol. Med. Public Health 2020, 2020, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, N.A. Everything in its place. Conservation of gene order among distantly related plant species. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 723–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Hu, B.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Zhou, J.H.; Luo, C.M.; Yang, X.L.; Wu, L.J.; et al. Coexistence of multiple coronaviruses in several bat colonies in an abandoned mineshaft. Virol. Sin. 2016, 31, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, L.; Ren, X.; He, G.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Qian, Z.; Dong, J.; Sun, L.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Deciphering the bat virome catalog to better understand the ecological diversity of bat viruses and the bat origin of emerging infectious diseases. ISME J. 2016, 10, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.K.; Woo, P.C.; Li, K.S.; Huang, Y.; Tsoi, H.W.; Wong, B.H.; Wong, S.S.; Leung, S.Y.; Chan, K.H.; Yuen, K.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 14040–14045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.Y.; Li, J.L.; Yang, X.L.; Chmura, A.A.; Zhu, G.; Epstein, J.H.; Mazet, J.K.; Hu, B.; Zhang, W.; Peng, C.; et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2013, 503, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Yang, W.; Yang, F.; Feng, Y.; Xia, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhen, W.; Feng, Y.; et al. Identification of diverse alphacoronaviruses and genomic characterization of a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome-like coronavirus from bats in China. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 7070–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.K.; Feng, Y.; Chen, H.; Luk, H.K.; Yang, W.H.; Li, K.S.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Huang, Y.; Song, Z.Z.; Chow, W.N.; et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Coronavirus ORF8 Protein Is Acquired from SARS-Related Coronavirus from Greater Horseshoe Bats through Recombination. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 10532–10547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.C.; Zhang, J.X.; Zhang, S.Y.; Wang, P.; Fan, X.H.; Li, L.F.; Li, G.; Dong, B.Q.; Liu, W.; Cheung, C.L.; et al. Prevalence and genetic diversity of coronaviruses in bats from China. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 7481–7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.K.; Li, K.S.; Huang, Y.; Shek, C.T.; Tse, H.; Wang, M.; Choi, G.K.; Xu, H.; Lam, C.S.; Guo, R.; et al. Ecoepidemiology and complete genome comparison of different strains of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related Rhinolophus bat coronavirus in China reveal bats as a reservoir for acute, self-limiting infection that allows recombination events. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 2808–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Qiao, H.; Huyan, L.; Liu, B.; Li, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, F.; Wang, H.; Yan, J. ISG15 is downregulated by KLF12 and implicated in maintenance of cancer stem cell-like features in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 4395–4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Care, M.A.; Stephenson, S.J.; Barnes, N.A.; Fan, I.; Zougman, A.; El-Sherbiny, Y.M.; Vital, E.M.; Westhead, D.R.; Tooze, R.M.; Doody, G.M. Network Analysis Identifies Proinflammatory Plasma Cell Polarization for Secretion of ISG15 in Human Autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawage, S.S.; Tiwari, P.M.; Singh, A.; Dixit, S.; Pillai, S.R.; Dennis, V.A.; Singh, S.R. Gold nanorods inhibit respiratory syncytial virus by stimulating the innate immune response. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, S.; Kim, J.K.; Shin, H.J.; Park, E.J.; Kim, I.S.; Jo, E.K. Updated insights into the molecular networks for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 563–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.I.; Ernst, R.K.; Bader, M.W. LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubier, T.G.; Galipaud, M.; Erten, E.Y.; Kokko, H. Transmissible cancers and the evolution of sex under the Red Queen hypothesis. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Lenarcic, E.M.; Yamane, D.; Wauthier, E.; Mo, J.; Guo, H.; McGivern, D.R.; González-López, O.; Misumi, I.; Reid, L.M.; et al. NLRX1 promotes immediate IRF1-directed antiviral responses by limiting dsRNA-activated translational inhibition mediated by PKR. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; König, R.; Deng, M.; Riess, M.; Mo, J.; Zhang, L.; Petrucelli, A.; Yoh, S.M.; Barefoot, B.; Samo, M.; et al. NLRX1 Sequesters STING to Negatively Regulate the Interferon Response, Thereby Facilitating the Replication of HIV-1 and DNA Viruses. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Han, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, B. Progress in targeting the NLRP3 signaling pathway for inflammatory bowel disease (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2025, 32, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theivanthiran, B.; Nguyen, Y.V.; Howell, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Plebanek, M.; DeVito, N.; Hanks, B. 547 Tumor NLRP3 amplification suppresses NLRC5 expression and MHC class I antigen processing and presentation while driving anti-PD-1 immunotherapy resistance. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, A621. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, G.; Han, F.; Guo, X.; Yang, L.; Du, N.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, C.; Peng, J.; Zhang, K.; Feng, J.; et al. Molecular Evolution of the NLR Gene Family Reveals Diverse Innate Immune Strategies in Bats. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121715

Liu G, Han F, Guo X, Yang L, Du N, Zhao X, Zhang C, Peng J, Zhang K, Feng J, et al. Molecular Evolution of the NLR Gene Family Reveals Diverse Innate Immune Strategies in Bats. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121715

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Gang, Fujie Han, Xinya Guo, Liya Yang, Nishan Du, Xue Zhao, Chen Zhang, Jie Peng, Kangkang Zhang, Jiang Feng, and et al. 2025. "Molecular Evolution of the NLR Gene Family Reveals Diverse Innate Immune Strategies in Bats" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121715

APA StyleLiu, G., Han, F., Guo, X., Yang, L., Du, N., Zhao, X., Zhang, C., Peng, J., Zhang, K., Feng, J., & Liu, Y. (2025). Molecular Evolution of the NLR Gene Family Reveals Diverse Innate Immune Strategies in Bats. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121715