Optimized Method for Establishing Primary Human Mesothelial Cell Cultures Preserving Epithelial Phenotype

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Primary MCs Isolation and Culture

2.2. RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR)

2.3. Immunocytochemistry

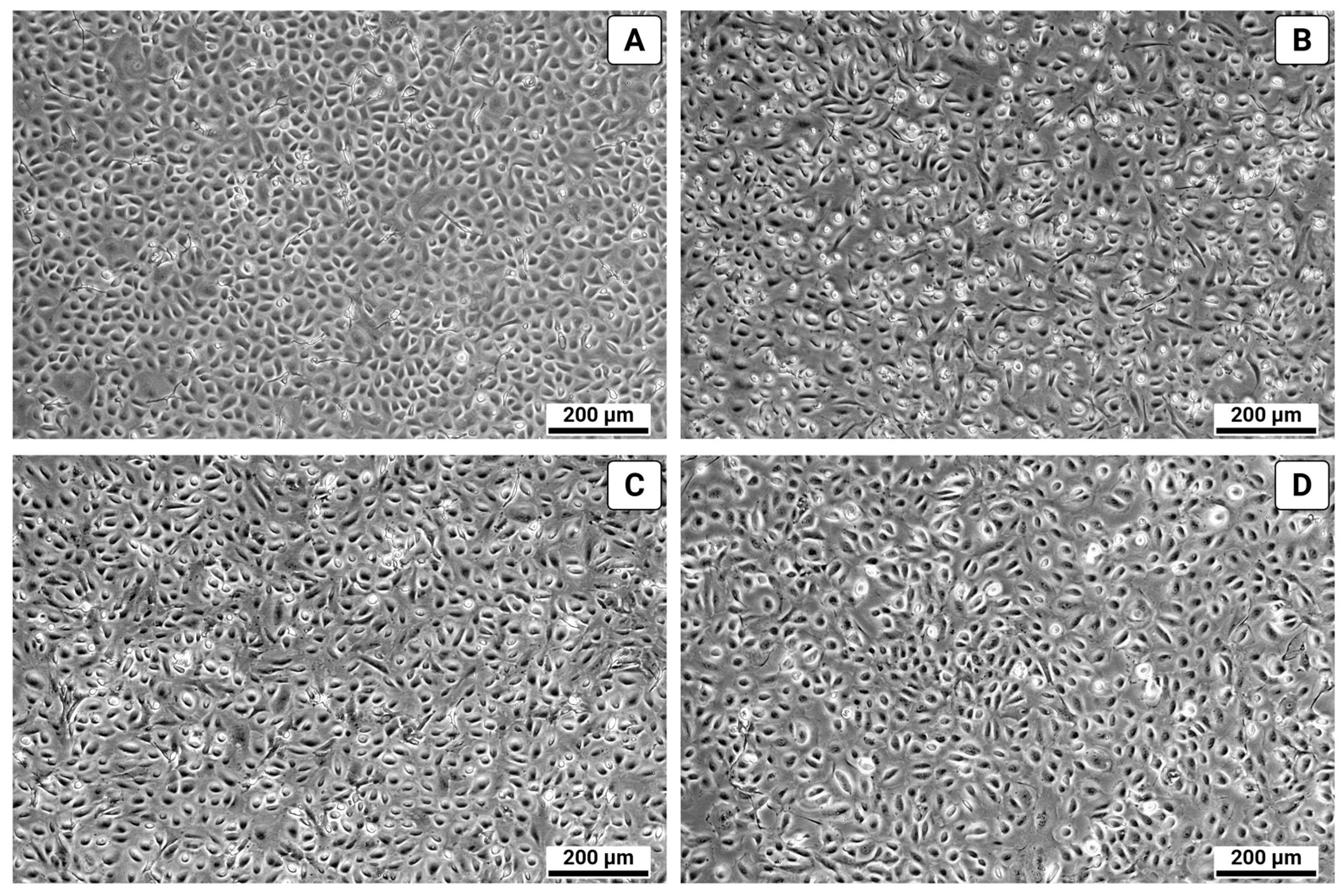

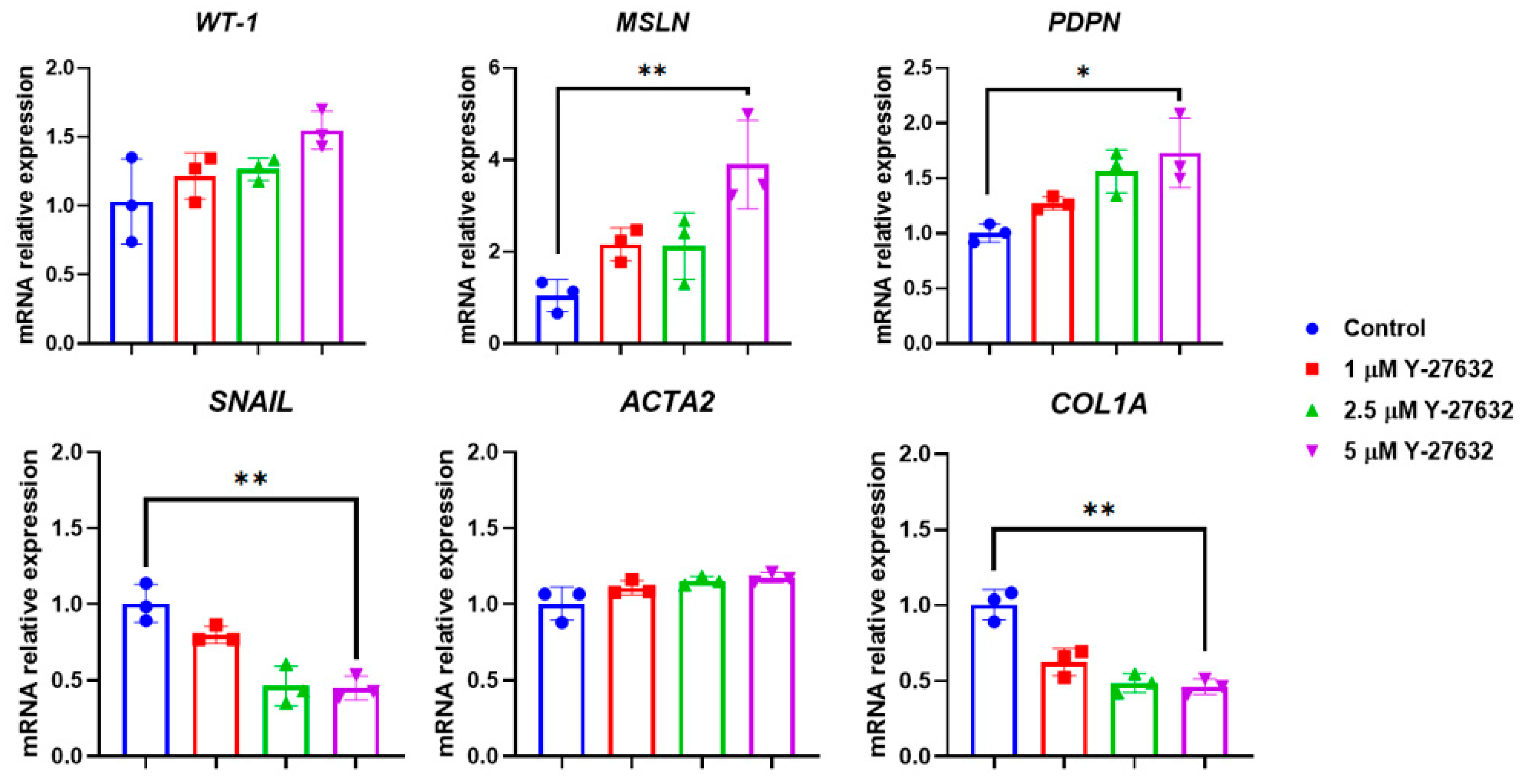

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mutsaers, S.E.; Birnie, K.; Lansley, S.; Herrick, S.E.; Lim, C.B.; Prele, C.M. Mesothelial Cells in Tissue Repair and Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López Cabrera, M. Mesenchymal Conversion of Mesothelial Cells Is a Key Event in the Pathophysiology of the Peritoneum during Peritoneal Dialysis. Adv. Med. 2014, 2014, 473134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmont, C.S.; Raby, A.C.; Dioszeghy, V.; LeBouder, E.; Foster, T.L.; Jones, S.A.; Labéta, M.O.; Fielding, C.A.; Topley, N. Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells Respond to Bacterial Ligands through a Specific Subset of Toll like Receptors. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 4079–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, H.; Antony, V.B. Pleural Mesothelial Cells in Pleural and Lung Diseases. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvar, S.; Woolf, A.S.; Zeef, L.A.; Wilm, T.; Wilm, B.; Herrick, S.E. Functional Molecules in Mesothelial-to-mesenchymal Transition Revealed by Transcriptome Analyses. J. Pathol. 2018, 245, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, H.; Fushida, S.; Harada, S.; Miyashita, T.; Oyama, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Tsukada, T.; Kinoshita, J.; Tajima, H.; Ninomiya, I.; et al. Importance of Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells in the Progression, Fibrosis, and Control of Gastric Cancer: Inhibition of Growth and Fibrosis by Tranilast. Gastric. Cancer 2018, 21, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomero Sanz, H.; Jiménez Heffernan, J.A.; Fernández Chacón, M.C.; Cristóbal García, I.; Sainz de la Cuesta, R.; González Cortijo, L.; López Cabrera, M.; Sandoval, P. Detection of Carcinoma Associated Fibroblasts Derived from Mesothelial Cells via Mesothelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Primary Ovarian Carcinomas. Cancers 2024, 16, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, J.M. Primary Cell Culture as a Model System for Evolutionary Molecular Physiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul, M.; Roslani, A.C.; Cheah, S.H. Heterogeneity in Cancer Cells: Variation in Drug Response in Different Primary and Secondary Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines in Vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2017, 53, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben David, U.; Siranosian, B.; Ha, G.; Tang, H.; Oren, Y.; Hinohara, K.; Strathdee, C.A.; Dempster, J.; Lyons, N.J.; Burns, R.; et al. Genetic and Transcriptional Evolution Alters Cancer Cell Line Drug Response. Nature 2018, 560, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, E.; Jenner, L.A.; Davies, M.; Coles, G.A.; Williams, J.D. Isolation, Culture and Characterization of Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. Kidney Int. 1990, 37, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holl, M.; Becker, L.; Keller, A.L.; Feuerer, N.; Marzi, J.; Carvajal Berrio, D.A.; Jakubowski, P.; Neis, F.; Pauluschke Fröhlich, J.; Brucker, S.Y.; et al. Laparoscopic Peritoneal Wash Cytology Derived Primary Human Mesothelial Cells for In Vitro Cell Culture and Simulation of Human Peritoneum. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, S.; Li, F.K.; Chan, T.M. Peritoneal Mesothelial Cell Culture and Biology. Perit. Dial. Int. 2006, 26, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obacz, J.; Valer, J.A.; Nibhani, R.; Adams, T.S.; Schupp, J.C.; Veale, N.; Lewis Wade, A.; Flint, J.; Hogan, J.; Aresu, G.; et al. Single Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Human Pleura Reveals Stromal Heterogeneity and Informs in Vitro Models of Mesothelioma. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 63, 2300143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, M.; Noia, H.; Fuh, K. Culturing Primary Human Mesothelial Cells. In Ovarian Cancer; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauleh, S.; Santeramo, I.; Fielding, C.; Ward, K.; Herrmann, A.; Murray, P.; Wilm, B. Characterisation of Cultured Mesothelial Cells Derived from the Murine Adult Omentum. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung Welch, N.; Patton, W.F.; Shepro, D.; Cambria, R.P. Human Omental Microvascular Endothelial and Mesothelial Cells: Characterization of Two Distinct Mesodermally Derived Epithelial Cells. Microvasc. Res. 1997, 54, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riera, M.; McCulloch, P.; Pazmany, L.; Jagoe, T. Optimal Method for Isolation of Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells from Clinical Samples of Omentum. J. Tissue Viability 2006, 16, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.H.K.; Ogando, C.R.; Wang See, C.; Chang, T.Y.; Barabino, G.A. Changes in Phenotype and Differentiation Potential of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Aging in Vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistyakova, I.V.; Bakalenko, N.I.; Malashicheva, A.B.; Atyukov, M.A.; Petrov, A.S. The Role of Notch Dependent Differentiation of Resident Fibroblasts in the Development of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Transl. Med. 2022, 9, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwocka, O.; Musielak, M.; Ampuła, K.; Piotrowski, I.; Adamczyk, B.; Fundowicz, M.; Suchorska, W.M.; Malicki, J. Navigating Challenges: Optimising Methods for Primary Cell Culture Isolation. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, P.; Lim, W.K. The Strategic Uses of Collagen in Adherent Cell Cultures. Cell Biol. Int. 2023, 47, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H.; Wikström, B.; Klominek, J.; Gay, R.E.; Gay, S.; Hjerpe, A. Immunocytochemical Demonstration of Collagen Types I and IV in Cells Isolated from Malignant Mesothelioma and in Lung Cancer Cell Lines. Lung Cancer 1990, 6, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Tchah, H.; Hwang, C. Effect of Rho Associated Kinase Inhibitor and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived Conditioned Medium on Corneal Endothelial Cell Senescence and Proliferation. Cells 2021, 10, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, P.C.; Bereiter--Hahn, J.; Missler, C.; Brzoska, M.; Schubert, R.; Gauer, S.; Geiger, H. Conditioned Medium from Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells Initiates Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cell Prolif. 2009, 42, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, D.G.; Perry, S.L.; Morrison, E.; Farmery, S.M.; Guillou, P.J. Activated Mesothelial Cells Produce Heparin-Binding Growth Factors: Implications for Tumour Metastases. Br. J. Cancer 2000, 82, 1233–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaney, J.; Dick, I.M.; Leon, J.S.; Robinson, B.W.S. A Proteomic Analysis of the Malignant Mesothelioma Secretome Using ITRAQ. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2017, 14, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.; Liu, X.; Meyers, C.; Schlegel, R.; McBride, A.A. Human Keratinocytes Are Efficiently Immortalized by a Rho Kinase Inhibitor. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 2619–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.C.; Chiu, H.T.; Lin, Y.F.; Lee, K.Y.; Pang, J.H.S. Y 27632, a ROCK Inhibitor, Promoted Limbal Epithelial Cell Proliferation and Corneal Wound Healing. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yi, B.; Yu, X. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition of Rat Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells via Rhoa/Rock Pathway. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2011, 47, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Becker, B.N.; Hoffmann, F.M.; Mertz, J.E. Complete Reversal of Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition Requires Inhibition of Both ZEB Expression and the Rho Pathway. BMC Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Das, S.; Surve, V.; Srivastava, A.; Kumar, S.; Jain, N.; Sawant, A.; Nayak, C.; Purwar, R. Blockade of ROCK Inhibits Migration of Human Primary Keratinocytes and Malignant Epithelial Skin Cells by Regulating Actomyosin Contractility. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra, H.; Antony, V.B. The Pleural Mesothelium in Development and Disease. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, A.M.; Tracy, R.P.; Craighead, J.E. Cytokeratin Expression in Rat Mesothelial Cells in Vitro Is Controlled by the Extracellular Matrix. J. Cell Sci. 1990, 95, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachali, C.; Eltoum, I.; Horton, D.; Chhieng, D.C. Use of Mesothelin as a Marker for Mesothelial Cells in Cytologic Specimens. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2006, 23, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, N.; Kimura, I. Podoplanin as a Marker for Mesothelioma. Pathol. Int. 2005, 55, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes | Primers |

|---|---|

| glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | F: 5′-ACAATTTGCTATCGTGGAAGG-3′ R: 5′-CCTTCCACGATAGCAAATTGT-3′ |

| mesothelin (MSLN) | F: 5′-CCTGAGGACATTCGCAAGTGGA-3′ R: 5′-CTTGAGGACATTCGCAAGTGGA-3′ |

| keratin 5 (KRT5) | F: 5′-CAGTGGAGAAGGAGTTGGACC-3′ R: 5′-TGCTGCTGGAGTAGTAGCTT-3′ |

| actin alpha 2 (ACTA2) or alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) | F: 5′-CTATGCCTCTGGACGCACAACTCAGATC-3′ R: 5′-CAGACGCATATGATGGCA-3′ |

| Wilms tumor protein 1 (WT-1) | F: 5′-CGAGAGCGATAACCACACAACG-3′ R: 5′-GTCTCAGATGCCGACCGTACAA-3′ |

| vimentin (VIM) | F: 5′-GAGAACTTTGCCGTTGAAGC-3′ R: 5′-GCTTCCTGTAGGTGGCAATC-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuznetsova, E.; Bakalenko, N.; Gaifullina, L.; Atyukov, M.; Dergilev, K.; Beloglazova, I.; Malashicheva, A. Optimized Method for Establishing Primary Human Mesothelial Cell Cultures Preserving Epithelial Phenotype. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121669

Kuznetsova E, Bakalenko N, Gaifullina L, Atyukov M, Dergilev K, Beloglazova I, Malashicheva A. Optimized Method for Establishing Primary Human Mesothelial Cell Cultures Preserving Epithelial Phenotype. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121669

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuznetsova, Evdokiya, Nadezhda Bakalenko, Liana Gaifullina, Mikhail Atyukov, Konstantin Dergilev, Irina Beloglazova, and Anna Malashicheva. 2025. "Optimized Method for Establishing Primary Human Mesothelial Cell Cultures Preserving Epithelial Phenotype" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121669

APA StyleKuznetsova, E., Bakalenko, N., Gaifullina, L., Atyukov, M., Dergilev, K., Beloglazova, I., & Malashicheva, A. (2025). Optimized Method for Establishing Primary Human Mesothelial Cell Cultures Preserving Epithelial Phenotype. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121669