Abstract

Anubias (Araceae) is a globally important group of ornamental aquatic plants. However, when temperatures drop to 10 °C, most species suffer obvious frostbite from cold stress, restricting winter cultivation and broader application. This study focused on two Anubias genotypes with distinct cold tolerance, adopting an integrated approach combining phenotypic, physiological, metabolomic, and transcriptomic analyses to reveal the mechanisms underlying their differential cold tolerance. Under 10 °C cold stress, compared with normal temperatures, the leaves of cold-tolerant Anubias sp. ‘Long Leaf’ (Jian) showed no significant frostbite, while cold-sensitive Anubias barteri var. nana ‘Coin Leaf’ (Jin) had clear frost damage. Both genotypes exhibited increased leaf relative electrical conductivity, malondialdehyde (MDA) content, soluble sugar content, and activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT); “Jian” had more notable rises in SOD/CAT activities and maintained higher levels, whereas “Jin” showed greater increases in conductivity, MDA, and soluble sugar. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses revealed “Jian” specifically upregulated metabolites in pathways like flavone and flavonol biosynthesis and tryptophan metabolism, as well as genes related to valine, leucine, isoleucine degradation and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathways. ERFs, WRKYs, NACs and other transcription factors correlated with these differentially expressed genes, suggesting potential transcriptional regulation. These results provides insights for breeding cold-tolerant Anubias and optimizing low-temperature cultivation.

1. Introduction

Low temperature is a common abiotic stress in natural environments. When exposed to cold stress, plants undergo alterations in the composition and function of their cell membrane systems [1]. They also actively accumulate osmoprotectants to enhance their osmotic adjustment capacity. For instance, increasing the levels of key osmoregulatory substances such as proline and soluble sugars helps collectively regulate cellular osmotic pressure, thereby enabling adaptation to changing environmental conditions [2]. Under stress conditions, the plant antioxidant enzyme system is also activated [3]. Enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) [4], catalase (CAT) [5,6], and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) [7] are involved in scavenging excess reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitigating oxidative damage caused by ROS.

Numerous studies have indicated that plant hormones and various metabolites play crucial roles in plant cold tolerance mechanisms [8,9,10]. Abscisic acid (ABA) is currently the most extensively studied hormone in the context of plant response to low-temperature stress. Cold stress can elevate endogenous ABA levels, thereby enhancing cold resistance [11,12,13]. Additionally, low temperature affects auxin transport, which in turn influences organogenesis and morphogenesis regulated by the accumulation and polar distribution of auxin in plant tissues [14]. Other phytohormones, including jasmonic acid (JA) [15], brassinosteroids (BRs) [16], and salicylic acid (SA) [17], also play significant roles in plant cold stress responses. Furthermore, amino acids [18], soluble sugars [19], flavonoids [20], tryptophan-related metabolites [21], and other compounds contribute importantly to cold tolerance across various plant species.

To adapt to low-temperature environments, plants activate cold tolerance mechanisms. Cold signals are perceived by membrane receptors, triggering Ca2+ signaling and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades, which regulate downstream transcription factors and cold-responsive genes [22,23,24,25,26]. The ICE1–CBF–COR pathway plays a central role, where ICE1 induces CBF expression, leading to COR gene activation and enhanced cold tolerance [27]. Other transcription factors, including AP2/ERF [28], bHLH [29,30], MYB [31], NAC [32], and WRKY [33], also contribute by regulating genes involved in hormone signaling and protective compound synthesis.

Plants of the genus Anubias (Araceae) have been commercialized worldwide as highly demanded aquatic ornamentals [34]. However, due to their tropical origin and preference for warm climates, they generally exhibit poor cold tolerance [35,36]. Based on our cultivation experience, Anubias growth nearly ceases when temperatures fall below 15 °C, and chilling injury occurs in most varieties below 10 °C. Thus, in simple greenhouse cultivation, Anubias struggle to overwinter in the Guangzhou region of China without additional heating. To date, research on Anubias has primarily focused on plastid genomes [36], propagation [37], and disease [38,39], with no studies addressing its cold tolerance. In the course of cultivation, it was observed that two varieties, Anubias sp. ‘Long Leaf’ (Jian) and Anubias barteri var. nana ‘Coin Leaf’ (Jin), exhibited significant differences in performance under low winter temperatures (approximately 10 °C). Among them, “Jian” demonstrated greater cold tolerance. We speculate that the two varieties underwent distinct physiological, biochemical, and molecular changes in response to low temperature, leading to the observed divergence in cold resistance.

This study utilizes two Anubias varieties showing differential responses to low temperature, integrating phenotypic, physiological, metabolomic, and transcriptomic data to reveal their physiological, biochemical, and gene expression changes under cold stress. The findings provide new insights into the cold tolerance mechanisms of Anubias, offering important references for breeding cold-resistant varieties and promoting related industry development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Stress Treatment

Two varieties of Anubias, namely Anubias sp. ‘Long Leaf’ (Jian) and Anubias barteri var. nana ‘Coin Leaf’ (Jin), grown for nine months, were used as experimental materials. For cold treatment, plants of both varieties were placed in an artificial climate chamber at 10 °C for three days. Control plants were maintained at 27 ± 2 °C. Each treatment included five plants per replicate, with three biological replicates. After three days, leaf samples were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis. For clarity and consistency in description, the control samples of “Jian” and “Jin” under normal temperature conditions are designated as Jian-CK and Jin-CK, respectively, while the samples subjected to low-temperature stress are referred to as Jian-LT and Jin-LT.

2.2. Measurement of Physiological Indicators

Relative electrolyte conductivity was measured using the soaking method described by Chen et al. [40]. Activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), as well as contents of malondialdehyde (MDA) and soluble sugars, were determined using assay kits manufactured by Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Solarbio, Beijing, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Non-Targeted Metabolomics Analysis Based on UPLC-MS/MS

2.3.1. Metabolite Extraction

The LC/MS system for metabolomics analysis comprises a Waters Acquity I-Class PLUS ultra-high performance liquid chromatograph tandem with a Waters Xevo G2-XS QTof high-resolution mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, CT, USA). The column utilized is a Waters Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (1.8 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm). For both positive and negative ion modes, mobile phase A consists of 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution, while mobile phase B is 0.1% formic acid acetonitrile. The injection volume is set at 2 µL.

2.3.2. LC-MS/MS Analysis

Primary and secondary mass spectrometry data were acquired in MSe mode using the Waters Xevo G2-XS QToF instrument controlled by MassLynx V4.2 software (Waters, Milford, USA). Each acquisition cycle included simultaneous dual-channel data collection at low collision energy (no collision energy) and high collision energy (ramped from 10 to 40 eV), with a scan rate of 0.2 s per spectrum. The electrospray ionization (ESI) parameters were set as follows: capillary voltage at 2500 V (positive mode) or −2000 V (negative mode), cone voltage at 30 V, ion source temperature at 100 °C, desolvation gas temperature at 500 °C, cone gas flow rate at 50 L/h, and desolvation gas flow rate at 800 L/h.

2.3.3. Data Preprocessing, Annotation and Differential Metabolite Screening

Raw data from MassLynx V4.2 were processed using Progenesis QI software (v3.0) for peak picking, alignment, and preprocessing. Metabolites were identified by searching against the online METLIN database and a custom-built library available in Progenesis QI. Identifications were considered confident based on a threshold of a total score ≥ 40. Identified metabolites were classified and assigned to metabolic pathways using the KEGG and HMDB databases. Prior to differential analysis, data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was verified using Levene’s test. For each compound, fold changes between groups were calculated, and significance was assessed using a t-test (p-value). Orthogonal projections to latent structures–discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was performed using the R (v4.5.0) package “ropls” (v1.40.0), and model reliability was evaluated through 200 permutation tests. Variable importance in projection (VIP) values were derived from the OPLS-DA model via cross-validation. Differential metabolites were selected based on the following criteria: fold change (FC) > 1, p-value < 0.05, and VIP > 1. Enrichment significance of KEGG pathways among differential metabolites was tested using a hypergeometric distribution test.

2.4. RNA-Sequence Analysis

2.4.1. Library Construction and Sequencing

RNA sequencing was performed on leaf samples collected from “Jian”, “Jin”, and their respective groups following low-temperature treatment. Each sample included three biological replicates. Total RNA was assessed for purity, concentration, and integrity to ensure the quality of the sequencing libraries. Libraries were constructed from 1 µg of total RNA per sample using the NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Poly-A mRNA was isolated using oligo (dT) magnetic beads and fragmented. First-strand cDNA was synthesized in NEBNext First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5×), followed by second-strand synthesis. After end repair, adapter ligation, and size selection (~240 bp) with the AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), the libraries were treated with USER Enzyme (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) and PCR-amplified. Final libraries were purified and quality-checked on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Indexed libraries were clustered on a cBot system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced on an Illumina platform to generate paired-end reads.

2.4.2. Quality Control and De Novo Assembly

Raw sequencing data were processed with custom Perl scripts to remove adapter sequences, poly-N reads, and low-quality sequences, yielding clean reads. Quality metrics including Q20, Q30, GC content, and duplication rate were calculated. De novo transcriptome assembly was performed using Trinity (v2.15.1) [41] with default parameters and a minimum k-mer coverage of 2.

2.4.3. Gene Annotation and Differential Expression Analysis

Assembled transcripts were annotated against the following databases: NR (Non-Redundant Protein Sequence Database at NCBI), Pfam (Protein Family Database), KOG/COG/eggNOG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups), Swiss-Prot (Curated Protein Sequence Database), KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes), and GO (Gene Ontology). Gene expression levels were estimated using RSEM (v1.3.3) by mapping clean reads to the assembled transcriptome. Differential expression analysis was conducted with the DESeq R package (v1.10.1), applying a negative binomial model. Genes with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 (Benjamini–Hochberg correction) were considered differentially expressed (DEGs). Functional enrichment analyses of DEGs for GO terms and KEGG pathways were performed using topGO (v2.60.1) (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) and KOBAS (v3.0) [42,43], respectively.

2.5. Correlation Network Analysis

To explore associations between transcription factors (TFs) and key enzyme genes in pathways of interest, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted between differentially expressed TFs and structural genes. Significant correlations were defined as those with an absolute correlation coefficient > 0.95 and a p-value < 0.05. The resulting network was visualized using Cytoscape version 3.10.1 [44].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise stated, all statistical analyses were performed in the R (v4.5.0) programming environment. One-way ANOVA, principal component analysis (PCA), and Pearson correlation analyses were carried out using built-in R functions. Hierarchical clustering heatmaps were generated with the “ComplexHeatmap” package (v2.24.1). OPLS-DA and VIP value calculations were implemented using the “ropls” package (v1.40.0).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Low Temperature on Leaf Phenotype and Physiological Indicators

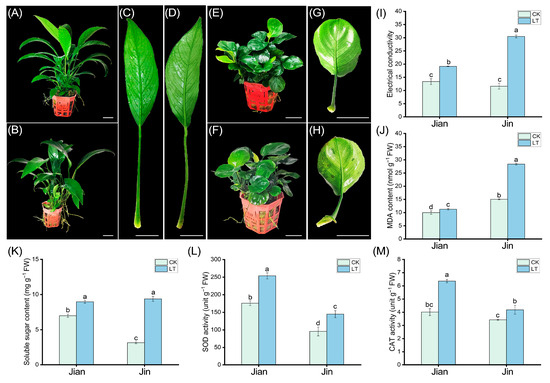

This study investigated the impact of low temperature on two varieties of Anubias: the relatively cold-tolerant Anubias sp. ‘Long Leaf’ (Jian) and the cold-sensitive Anubias barteri var. nana ‘Coin Leaf’ (Jin). Phenotypic observations revealed no significant changes on either the adaxial or abaxial leaf surfaces of “Jian” after cold treatment. In contrast, the abaxial surface of “Jin” exhibited water-soaked lesions symptomatic of chilling injury (Figure 1). These phenotypic results indicate that “Jin” is more susceptible to cold stress than “Jian”. To further evaluate the differences in cold tolerance between the two varieties, key physiological indicators were measured. Following low-temperature stress, the relative electrolyte conductivity of “Jian” increased to 1.4 times that of the control, while that of “Jin” increased to 2.6 times. The malondialdehyde (MDA) content in “Jian” rose to 1.1 times the control level, whereas in “Jin”, it increased to 1.8 times. These results suggest more severe membrane damage in “Jin”. The antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) help alleviate oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation under cold stress. Both varieties showed increased SOD and CAT activities after cold treatment. Specifically, the SOD activity in “Jian” increased to 1.4 times that of the control, compared to 1.5 times in “Jin”. The CAT activity increased to 1.5 times the control in “Jian” and 1.2 times in “Jin”. Additionally, soluble sugar content increased in both varieties under cold stress. “Jian” exhibited a 1.3-fold increase compared to the control, while “Jin” showed nearly a 3-fold increase.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic and physiological effects of low-temperature stress on Anubias sp. ‘Long Leaf’ (Jian) and Anubias barteri var. nana ‘Coin Leaf’ (Jin). (A,B) Phenotype of “Jian” plants under control and low-temperature conditions, respectively. (C,D) Leaf performance of “Jian” under control and low-temperature conditions, respectively. (E,F) Phenotype of “Jin” plants under control and low-temperature conditions, respectively. (G,H) Leaf performance of “Jin” under control and low-temperature conditions, respectively. (I) Relative electrolyte conductivity. (J) MDA content. (K) Soluble sugar content. (L) SOD activity. (M) CAT activity. CK: control group at ambient temperature. LT: low-temperature treatment at 10 °C. Bars with different letters (a, b, c, d) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) according to one-way ANOVA.

3.2. Non-Targeted Metabolite Detection, Identification, and Annotation

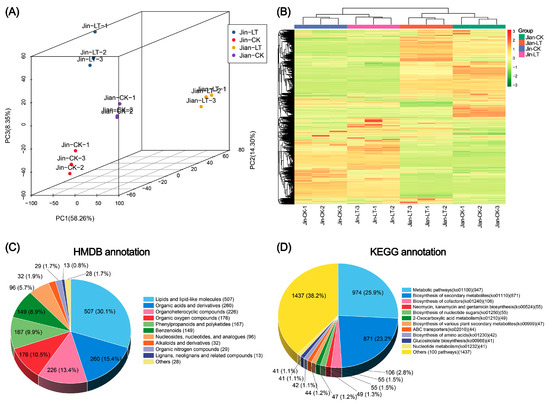

To further investigate metabolic changes in the leaves of the two Anubias varieties under low-temperature conditions, non-targeted metabolomic analysis was performed using UPLC-MS/MS. As shown in Figure 2, distinct metabolic differences were observed between the two species under both normal and low-temperature conditions. Principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) revealed that the three biological replicates within each treatment group clustered closely together, indicating high data quality.

Figure 2.

Non-targeted metabolite profiling and annotation based on UPLC-MS/MS in two Anubias varieties under control and low-temperature stress conditions. (A) PCA score plot. (B) Hierarchical clustering heatmap. (C) HMDB database annotation of metabolites. (D) KEGG database annotation of metabolites.

A total of 3366 metabolites were identified, including 2159 in positive ion mode and 1207 in negative ion mode (Table S1). Metabolite annotation results showed that 1678 metabolites were annotated in the HMDB database, with more than 100 metabolites each in the following categories (Table S2): Lipids and lipid-like molecules (508), organic acids and derivatives (262), organoheterocyclic compounds (227), organic oxygen compounds (177), phenylpropanoids and polyketides (167), and benzenoids (149). In the KEGG database, 2023 compounds were annotated and enriched in 112 metabolic pathways (Table S2). The pathways with the highest number of annotated metabolites were “metabolic pathways” (947, 25.9%), “biosynthesis of secondary metabolites” (871, 23.2%) and “biosynthesis of cofactors” (106, 2.8%). The number of compounds assigned to all other pathways was fewer than 100.

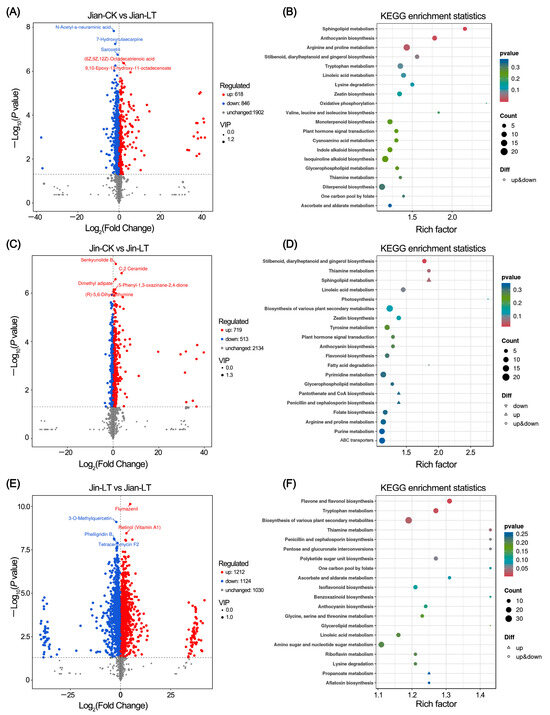

3.3. Metabolic Changes Under Low-Temperature Stress

Further analysis identified changes in leaf metabolites under low-temperature conditions in both varieties (Figure 3). In the cold-tolerant variety “Jian”, 618 metabolites were up-regulated and 846 were down-regulated compared to the control conditions. In the cold-sensitive variety “Jin”, 719 metabolites were up-regulated and 513 were down-regulated under cold stress. KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that the differentially expressed metabolites in “Jian” were significantly enriched in sphingolipid metabolism, anthocyanin biosynthesis, and arginine and proline metabolism pathways. In contrast, the differential metabolites in “Jin” were primarily enriched in stilbenoid, diarylheptanoid and gingerol biosynthesis pathways. Under low-temperature treatment, compared to the cold-sensitive “Jin”, the cold-tolerant “Jian” exhibited 1212 up-regulated and 1124 down-regulated metabolites. These were significantly enriched in flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, tryptophan metabolism, biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites, and thiamine metabolism pathways.

Figure 3.

Identification of differential metabolites in two Anubias varieties under control versus low-temperature stress. (A,B) Volcano plot and KEGG enrichment analysis of differential metabolites in “Jian” under control and low-temperature stress, respectively. (C,D) Volcano plot and KEGG enrichment analysis of differential metabolites in “Jin” under control and low-temperature stress, respectively. (E,F) Volcano plot and KEGG enrichment analysis of differential metabolites in “Jian” versus “Jin” under low-temperature stress.

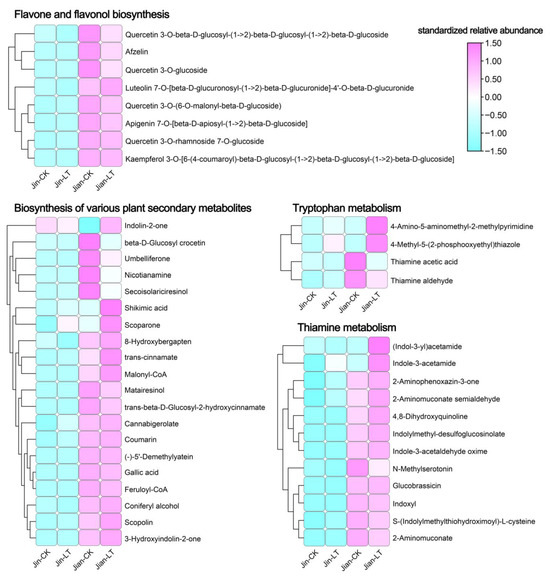

We focused specifically on metabolites in these significantly enriched pathways under low-temperature conditions (Figure 4). Compared to “Jin”, the cold-tolerant “Jian” showed 8, 12, 20, and 4 significantly up-regulated metabolites in the flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, tryptophan metabolism, biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites, and thiamine metabolism pathways, respectively, highlighting their potential role in cold resistance.

Figure 4.

Identification of significantly up-regulated metabolites in key enriched pathways of differential metabolites in Jin-LT versus Jian-LT under low-temperature stress.

3.4. Transcriptomic Analysis Under Low-Temperature Stress

3.4.1. RNA-Seq Quality Assessment, Assembly, and Annotation

To further elucidate the molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying the differential cold tolerance between the two varieties under low-temperature stress, a de novo RNA-seq analysis was conducted. A total of 265,898,237 reads (79.46 Gb) were obtained from the four samples. The GC content ranged from 48.91% to 51.40%, Q20 from 97.11% to 97.51%, and Q30 from 92.28% to 93.16%, indicating high-quality sequencing data (Table S3). After de novo assembly and gene annotation, 99,874 unigenes were annotated across nine databases: COG, GO, KEGG, KOG, Pfam, SwissProt, TrEMBL, eggNOG, and NR, with 6313, 25,196, 18,982, 15,879, 17,359, 17,003, 31,342, 25,211, and 30,296 genes annotated in each database, respectively (Table S4). In total, 32,900 genes were functionally annotated.

The box-plot demonstrates highly consistent distributions of log10(FPKM) across all samples, indicating robust and reproducible transcriptomic data quality (Figure S1). PCA of gene expression levels showed strong correlations among biological replicates of the same sample, which clustered closely together in the PCA score plot (Figure S2). In contrast, different samples exhibited lower correlations and greater spatial separation, confirming good reproducibility of the RNA-seq data and significant transcriptional differences between samples.

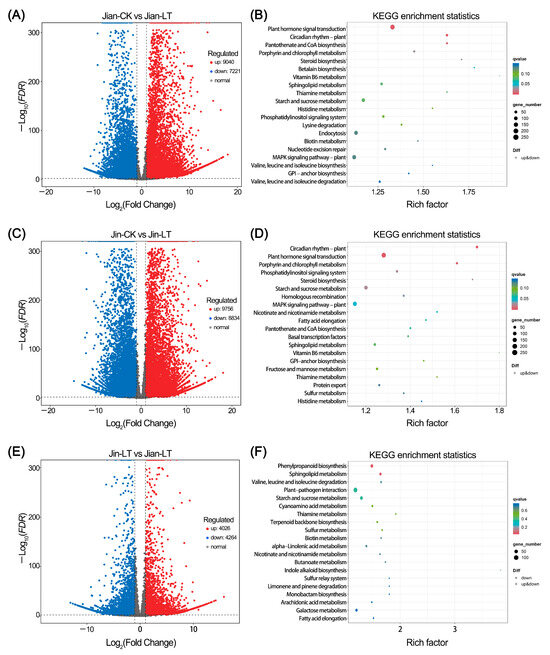

3.4.2. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

The results of differential gene expression analysis are shown in Figure 5. Compared to the control, 9040 genes were up-regulated and 7221 were down-regulated in the cold-treated “Jian”. These DEGs were significantly enriched in pathways including Plant hormone signal transduction, Circadian rhythm-plant, Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis, Porphyrin metabolism, and Steroid biosynthesis. Up-regulated DEGs were notably enriched in the MAPK signaling pathway-plant (122 genes), sphingolipid metabolism (51 genes), endocytosis (107 genes), plant hormone signal transduction (126 genes), valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation (31 genes), phagosome (50 genes), cysteine and methionine metabolism (63 genes), and proteasome (29 genes) (Table S5). Down-regulated DEGs were significantly enriched in circadian rhythm-plant (50 genes), porphyrin metabolism (37 genes), steroid biosynthesis (18 genes), pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis (27 genes), glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis (16 genes), histidine metabolism (14 genes), plant hormone signal transduction (128 genes), and valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis (11 genes) (Table S5).

Figure 5.

Mining of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in two Anubias varieties under control and low-temperature stress. (A,B) Volcano plot and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in “Jian” under control and low-temperature stress, respectively. (C,D) Volcano plot and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in “Jin” under control and low-temperature stress, respectively. (E,F) Volcano plot and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in “Jian” versus “Jin” under low-temperature stress.

In the cold-treated “Jin”, 9756 genes were up-regulated and 8834 were down-regulated. These were significantly enriched in pathways such as circadian rhythm-plant, plant hormone signal transduction, porphyrin metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism, steroid biosynthesis, phosphatidylinositol signaling system, homologous recombination, nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, and MAPK signaling pathway-plant. Up-regulated DEGs were enriched in MAPK signaling pathway-plant (126 genes), sphingolipid metabolism (52 genes), plant hormone signal transduction (126 genes), cysteine and methionine metabolism (67 genes), endocytosis (93 genes), biosynthesis of amino acids (108 genes), proteasome (28 genes), protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum (127 genes), and phagosome (47 genes) (Table S6). Down-regulated DEGs were enriched in circadian rhythm-plant (57 genes), porphyrin metabolism (45 genes), steroid biosynthesis (18 genes), fatty acid biosynthesis (35 genes), GPI-anchor biosynthesis (19 genes), fatty acid elongation (21 genes), homologous recombination (35 genes), and basal transcription factors (25 genes) (Table S6).

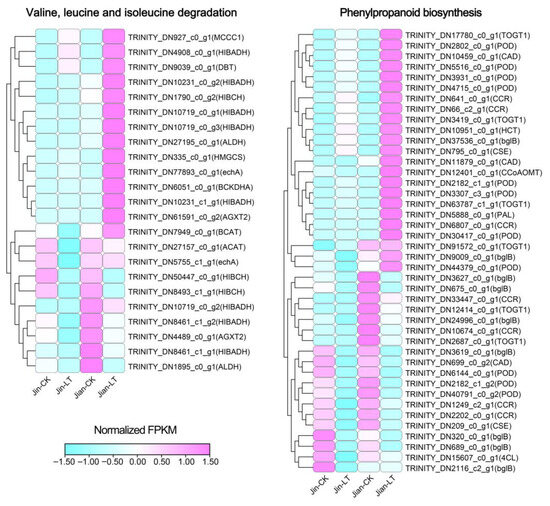

Compared to the cold-sensitive “Jin”, the cold-tolerant “Jian” under low-temperature treatment exhibited 4026 up-regulated and 4264 down-regulated genes. These were mainly enriched in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, sphingolipid metabolism, valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation, and Starch and sucrose metabolism. Up-regulated DEGs were significantly enriched in valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation (23 genes) and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (42 genes), while down-regulated DEGs showed no significant pathway enrichment (Table S7).

We further identified key genes in the significantly enriched pathways among up-regulated DEGs in Jian-LT vs. Jin-LT (Figure 6; Table S8). In valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation, 23 genes were identified, including 8 HIBADH, 3 HIBCH, 2 AGXT2, 2 ALDH, 2 echA, and one each of ACAT, BCAT, BCKDHA, DBT, HMGCS, and MCCC1. The sustained high expression of these genes in “Jian” under cold stress suggests their potential role in maintaining amino acid homeostasis and providing energy for the respiratory chain, thereby contributing to cold tolerance. In phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, 42 genes were identified, including 11 POD, 9 bglB, 7 CCR, 6 TOGT1, 3 CAD, 2 CSE, and one each of PAL, 4CL, HCT, and CCoAOMT. The relatively high expression of these genes may promote the synthesis of downstream antioxidants such as phenylpropanoids and flavonoids, further enhancing cold resistance in “Jian”.

Figure 6.

Relative expression analysis of genes related to the valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathways, which were significantly enriched among up-regulated DEGs in Jin-LT versus Jian-LT.

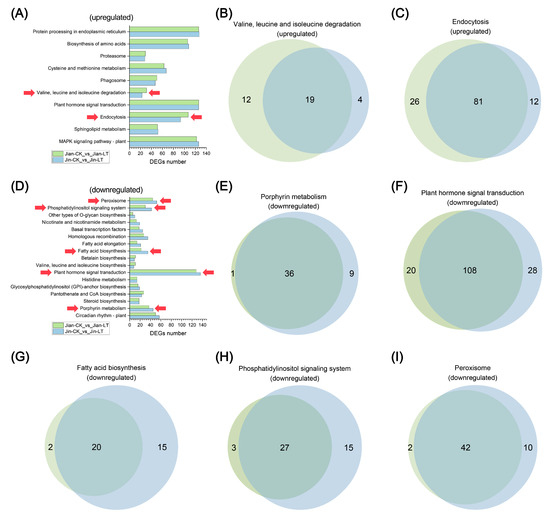

3.4.3. Differences in Gene Numbers in Commonly Enriched Pathways of DEGs Under Control and Low-Temperature Stress

We first analyzed the differences in the number of DEGs between the two comparison groups, Jin-CK vs. Jian-CK and Jin-LT vs. Jian-LT. Among the up-regulated genes, only 624 DEGs were shared by both comparison groups, while 1,604 were unique to Jin-CK vs. Jian-CK and 2164 were unique to Jin-LT vs. Jian-LT. Among the down-regulated genes, 416 DEGs were common to both groups, whereas 1728 were specific to Jin-CK vs. Jian-CK and 1769 were specific to Jin-LT vs. Jian-LT. These results indicate that the transcriptional responses to low temperature are markedly different between “Jin” and “Jian”.

To further investigate key metabolic pathways altered by low-temperature stress in both varieties, we compared the number of DEGs in significantly enriched pathways under cold conditions (Figure 7). Among the significantly up-regulated pathways, notable differences in DEG numbers were observed in Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation and Endocytosis. Only 19 and 81 DEGs were shared between the two varieties in these pathways, respectively. The cold-tolerant variety “Jian” exhibited a substantially greater number of unique up-regulated genes in these pathways compared to “Jin”. For significantly down-regulated pathways, considerable differences in DEG abundance were identified in porphyrin metabolism, plant hormone signal transduction, fatty acid biosynthesis, phosphatidylinositol signaling system, and peroxisome pathways. Specifically, the cold-sensitive variety “Jin” showed markedly more unique down-regulated DEGs in these pathways, with 9, 28, 15, 15, and 10 unique genes, respectively, compared to “Jian”.

Figure 7.

Analysis of differences in gene numbers within commonly enriched pathways of DEGs in two Anubias varieties under control and low-temperature stress. (A) Comparative analysis of the number of up-regulated DEGs. (B) Venn diagram of DEGs in the Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation pathway. (C) Venn diagram of DEGs in the Endocytosis pathway. (D) Comparative analysis of the number of down-regulated DEGs. (E) Venn diagram of DEGs in the porphyrin metabolism pathway. (F) Venn diagram of DEGs in the endocytosis pathway. (G) Venn diagram of DEGs in the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway. (H) Venn diagram of DEGs in the phosphatidylinositol signaling system pathway. (I) Venn diagram of DEGs in the peroxisome pathway.

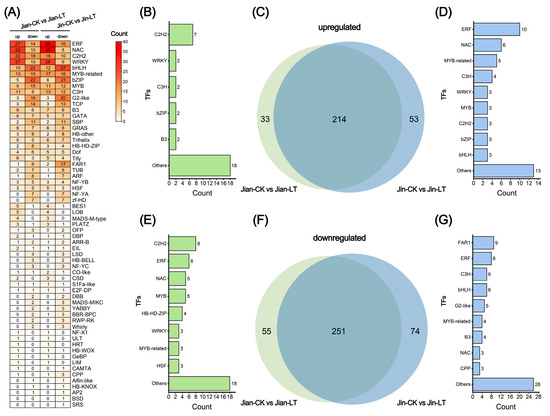

3.4.4. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Transcription Factors

Differentially expressed transcription factors (TFs) were identified and statistically analyzed following low-temperature stress (Figure 8). Compared to the control, 247 TFs were up-regulated and 306 were down-regulated in cold-treated “Jian”. The TF families exhibiting the most pronounced changes (over 20 members each) included ERF, NAC, C2H2, WRKY, bHLH, MYB-related, bZIP, and MYB. Similarly, in cold-treated “Jin”, 247 TFs were up-regulated and 306 down-regulated, with substantial changes (over 20 members each) observed in ERF, NAC, C2H2, WRKY, bHLH, MYB-related, bZIP, MYB, C3H, and G2-like families. The similarity in the TF families showing extensive expression changes suggests a conserved transcriptional response to low-temperature stress in both varieties.

Figure 8.

Statistical analysis of transcription factors (TFs) with significant expression changes under low-temperature stress in two Anubias varieties. (A) Number of differentially expressed TFs in “Jian” and “Jin” compared to control. (B) Number of TFs significantly up-regulated only in Jian-CK vs. Jian-LT. (C) Venn analysis of TFs significantly up-regulated in both Jian-CK vs. Jian-LT and Jin-CK vs. Jin-LT. (D) Number of TFs significantly up-regulated only in Jin-CK vs. Jin-LT. (E) Number of TFs significantly down-regulated only in Jian-CK vs. Jian-LT. (F) Venn analysis of TFs significantly down-regulated in both Jian-CK vs. Jian-LT and Jin-CK vs. Jin-LT. (G) Number of TFs significantly down-regulated only in Jin-CK vs. Jin-LT.

To further investigate varietal differences in TF expression, we examined the consistency of significantly altered TFs under cold stress. Among the significantly up-regulated TFs, 33 were unique to “Jian”, with the C2H2 family being the most abundant. In contrast, 53 were uniquely up-regulated in “Jin”, predominantly from the ERF, NAC, MYB-related, and C3H families. Among the significantly down-regulated TFs, 55 were unique to “Jian”, mainly comprising C2H2, ERF, NAC, and MYB families, while 74 were unique to “Jin”, with FAR1, ERF, C3H, bHLH, and G2-like being the most represented. Overall, the cold-sensitive variety “Jin” exhibited a greater number of significantly altered TFs in response to cold stress compared to the cold-tolerant variety “Jian”.

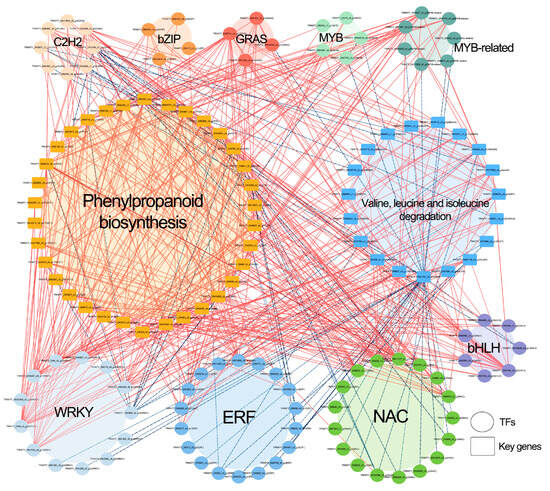

3.5. Correlation Network Analysis Between Transcription Factors and Key Differential Metabolic Pathways

We performed correlation analysis between major reported transcription factor (TF) families—including ERF, MYB, MYB-related, bHLH, NAC, WRKY, C2H2, bZIP, and GRAS—and enzyme-coding genes from two significantly enriched pathways: Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation (Figure 9; Table S9). The results revealed that 83 TFs, including 18 ERF, 17 NAC, 13 WRKY, 8 C2H2, 7 bHLH, 7 MYB-related, 5 MYB, 4 bZIP, and 4 GRAS members, were significantly correlated with 34 genes involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and 19 genes associated with valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation. These correlations were predominantly positive.

Figure 9.

Correlation network analysis between key transcription factors (TFs) responsive to cold stress in Anubias and genes from significantly up-regulated metabolic pathways (Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation). Solid red lines indicate significant positive correlations between a TF and a gene, while blue dashed lines represent significant negative correlations.

Specifically, 47 TFs (9 ERF, 8 WRKY, 7 NAC, 6 bHLH, and 17 others) showed significant positive correlations with 34 Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis genes (10 POD, 8 bglB, 6 CCR, 5 TOGT1, and 5 others). In contrast, 13 TFs (4 NAC, 3 ERF, 3 C2H2, and 3 others) were significantly negatively correlated with 16 Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis genes (6 POD, 5 CCR, and 5 others). Furthermore, 38 TFs (7 WRKY, 6 ERF, 6 NAC, 5 bHLH, and 14 others) exhibited significant positive correlations with 17 Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation genes (6 HIBADH, 3 HIBCH, 2 ALDH, and 6 others). Conversely, 38 TFs (11 NAC, 9 ERF, 5 WRKY, 5 C2H2, and 8 others) were significantly negatively correlated with 11 genes in this pathway (2 HIBADH and 9 others). These findings highlight the potential transcriptional regulatory roles of these TFs in modulating genes involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation pathways.

4. Discussion

In this study, after three days of treatment at 10 °C, the cold-sensitive variety “Jin” exhibited clear symptoms of water-soaked chilling injury, whereas the cold-tolerant variety “Jian” did not. Although both Anubias varieties showed significant increases in relative electrolyte conductivity and MDA content, the increases were more pronounced in “Jin”. Additionally, soluble sugar concentration, SOD activity, and catalase CAT activity were elevated to varying degrees in both varieties. Notably, the cold-tolerant “Jian” maintained significantly higher levels of SOD and CAT activity compared to “Jin”. SOD [45] and CAT [46] play crucial roles in cold resistance by synergistically scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) and protecting plant Biomolecules from oxidative damage under low-temperature stress [47]. Our results clearly demonstrate that the cold-tolerant “Jian” exhibits higher antioxidant enzyme activity under cold stress than the cold-sensitive “Jin”, which is consistent with previous studies.

Numerous metabolites have been implicated in cold stress responses across various plant species. In this study, UPLC-MS/MS analysis revealed that, compared to the cold-sensitive “Jin”, the cold-tolerant “Jian” showed significant up-regulation of metabolites involved in flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, tryptophan metabolism, biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites, and thiamine metabolism. flavonoids, key secondary metabolites in plants, play vital roles in development and stress responses [20]. Under cold stress, plants accumulate flavonoids to provide antioxidant protection by neutralizing free radicals and ROS, thereby preventing cellular damage [48]. Flavonoid accumulation has been documented in multiple plant species under cold stress, including coconut [49], alfalfa [50], mustard [51], and barley [52]. Additionally, thiamine enhances plant immunity and defense systems, playing a key role in protection against biotic and abiotic stresses [53,54]. Cold stress has been reported to activate thiamine metabolism in Arabidopsis [55], grape [56], and Chinese yew [57]. Tryptophan-related metabolites also contribute significantly to stress resistance in plants [58]. Exogenous tryptophan application has been shown to enhance cold tolerance in soybean seedlings [59], and low-temperature storage modulates tryptophan metabolism to maintain the quality of high-moisture maize [60]. These findings support the important role of metabolite accumulation in flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, tryptophan metabolism, biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites, and thiamine metabolism in the cold tolerance of “Jian”.

Compared to control conditions, DEGs in both varieties under cold stress were significantly enriched in pathways such as plant hormone signal transduction, circadian rhythm-plant, porphyrin metabolism, steroid biosynthesis, MAPK signaling pathway-plant, sphingolipid metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, proteasome, and phagosome, highlighting shared response mechanisms between the two varieties. Notably, up-regulated DEGs in the cold-tolerant “Jian” were predominantly enriched in valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis compared to the cold-sensitive “Jin”. Furthermore, when compared to its own control, “Jian” under cold stress also showed significant enrichment of up-regulated DEGs in valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation, whereas “Jin” did not. Branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) catabolism not only contributes to amino acid homeostasis but also serves as an alternative energy source when carbohydrate availability is limited [61]. Under such conditions, BCAAs act as respiratory substrates, providing electrons to the respiratory chain and intermediates to the tricarboxylic acid cycle [62,63]. Studies on abiotic stresses such as drought in sugarcane [64], wheat [65], and Hibiscus mutabilis [66], as well as diurnal temperature variation in tea plants [67], have reported significant enrichment of DEGs in valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation, aligning with our findings and expanding the understanding of this pathway’s role in plant stress responses. The metabolic differences in this pathway between the two Anubias varieties under cold stress may significantly contribute to their differential cold tolerance.

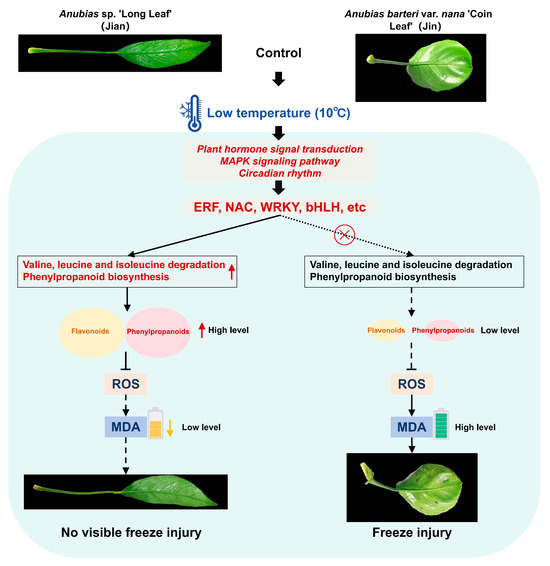

In recent years, multiple TFs involved in cold stress responses have been characterized [68]. TFs play essential roles in regulating growth, development, and physiological adaptation under cold stress. In this study, we identified several TFs with altered expression in both Anubias varieties under low-temperature conditions. Correlation analysis further suggested significant associations between specific TFs and genes in the valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathways, implying potential regulatory relationships. We propose a model for the differential responses of the two varieties under cold stress (Figure 10). Upon exposure to 10 °C, both varieties perceive the low-temperature signal, leading to significant changes in signal transduction pathways such as plant hormone signal transduction, circadian rhythm-plant, and MAPK signaling pathway-plant, which activate various TFs (e.g., ERF, NAC, WRKY). However, unlike the cold-sensitive variety, the cold-tolerant “Jian” may employ these TFs to activate valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation—regulating amino acid homeostasis and providing energy—and to enhance phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, increasing the production of flavonoids and phenylpropanoids that scavenge ROS or reinforce cell walls to reduce oxidative damage, thereby conferring greater cold tolerance.

Figure 10.

Proposed model illustrating the differential response mechanisms of two Anubias varieties under low-temperature stress. A solid arrow indicates a promoting effect, while a dashed arrow suggests a diminished promoting effect. A solid line with a ‘T’ end denotes inhibition, while a dashed line with a ‘T’ end suggests weaker inhibition. The red circle-with-cross symbol indicates a potentially non-existent transcriptional regulatory targeting relationship.

While this study has delineated the physiological, metabolic, and transcriptional changes in two Anubias varieties under low-temperature stress and highlighted the potential roles of key pathways and TFs, the functions of these key candidates—particularly the pivotal TFs—require further validation. This should include dynamic RT-qPCR analyses following low-temperature treatment, as well as genetic transformation experiments (e.g., gene overexpression and silencing) to confirm their roles in cold tolerance. In addition, targeted metabolomics should be applied to accurately quantify metabolites in key pathways implicated in the cold response—such as flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, tryptophan metabolism, biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites, and thiamine metabolism—to identify signature metabolites critical for cold tolerance in Anubias. These follow-up studies will provide a foundation for the precise evaluation and targeted breeding of cold-hardy Anubias varieties.

Although we have preliminarily identified key metabolic pathways contributing to the differential cold tolerance between the two varieties, the central signaling components and key regulators require further experimental validation. Additionally, the regulatory roles of the identified TFs in activating Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation and Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathways need to be verified through molecular biological approaches.

5. Conclusions

This multi-omics investigation reveals that the differential cold tolerance between the two Anubias genotypes stems from distinct molecular and physiological responses to low-temperature stress. The cold-tolerant genotype Anubias sp. ‘Long Leaf’ (Jian) exhibited superior performance through maintaining significantly higher activities of key antioxidant enzymes (SOD and CAT), thereby mitigating oxidative damage more effectively than the cold-sensitive genotype Anubias barteri var. nana ‘Coin Leaf’ (Jin). Furthermore, “Jian” specifically activated biosynthesis of protective metabolites—particularly flavones and flavonols—and enhanced tryptophan metabolism, alongside coordinated upregulation of genes involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation. Critical transcription factor families, including ERFs, WRKYs, and NACs, were implicated in regulating these adaptive responses. These findings provide a comprehensive molecular framework for understanding cold tolerance mechanisms in aquatic plants and offer valuable insights for the targeted breeding of cold-hardy Anubias varieties.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biom15111520/s1. Table S1: UPLC-MS/MS-based non-targeted metabolite profiling of two Anubias cultivars under cold stress; Table S2. HMDB and KEGG database annotation of metabolites; Table S3: Summary of RNA-seq data statistics for the 12 samples; Table S4: Gene annotation statistics based on nine databases; Table S5: KEGG enrichment analysis of up- and down-regulated DEGs in Jian-CK_vs_Jian-LT; Table S6: KEGG enrichment analysis of up- and down-regulated DEGs in Jin-CK vs. Jin-LT; Table S7: KEGG enrichment analysis of up- and down-regulated DEGs in Jin-LT vs. Jian-LT; Table S8: DEG information for two significantly enriched KEGG pathways in Jin-LT vs. Jian-LT; Table S9: Significantly correlated TFs and key genes involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation; Figure S1: Box-plot comparison of Log10(FPKM) values across 12 RNA-seq samples; Figure S2: PCA score plot evaluating the 12 RNA-seq samples; Figure S3. Venn diagram of upregulated DEGs between “Jin-CK vs. Jian-CK” and “Jin-LT vs. Jian-LT;” Figure S4. Venn diagram of downregulated DEGs between “Jin-CK vs. Jian-CK” and “Jin-LT vs. Jian-LT”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and Y.L.; methodology, Y.L. and L.W.; software, W.L. and J.C.; validation, J.Z., Z.Y. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.L. and L.W.; investigation, W.L. and J.C.; resources, J.Z. and Z.Y.; data curation, S.H. and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and L.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and S.H.; visualization, W.L. and J.C.; supervision, S.H. and Y.Z.; project administration, Y.Z. and S.H.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. and S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Guangzhou Municipal Financial Grant Project for Agriculture and Rural Affairs, grant number 25100001; Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, grant number 2023A1515140021; and Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences Talent Introduction Project for 2022, grant number R2022YJ-YB3023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s). The raw RNA-seq data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number PRJNA1348912.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goswami, A.K.; Maurya, N.K.; Goswami, S.; Bardhan, K.; Singh, S.K.; Prakash, J.; Pradhan, S.; Kumar, A.; Chinnusamy, V.; Kumar, P.; et al. Physio-biochemical and molecular stress regulators and their crosstalk for low-temperature stress responses in fruit crops: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1022167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, N.; Li, L.; Fang, Y.; Fan, S.; Wu, C. Comparative physiological and transcriptome analyses of tolerant and susceptible cultivars reveal the molecular mechanism of cold tolerance in Anthurium andraeanum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, L.; Gu, C.; Na, Y.; Xie, B.; Cheng, S.; Pan, G. Application of brassinolide alleviates cold stress at the booting stage of rice. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, W.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, P.; Yao, X.; Lin, J. Cbrci35, a cold responsive peroxidase from capsella bursa-pastoris regulates reactive oxygen species homeostasis and enhances cold tolerance in tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Wei, T.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, J. Overexpression of ptrbhlh, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor from poncirus trifoliata, confers enhanced cold tolerance in pummelo (Citrus grandis) by modulation of H2O2 level via regulating a CAT gene. Tree Physiol. 2019, 39, 2045–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Duan, X.; Yang, J.; Beeching, J.R.; Zhang, P. Coupled expression of cu/zn-superoxide dismutase and catalase in cassava improves tolerance against cold and drought stresses. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e24525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, J.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, S.; Sun, X.; Qiu, Q.; Lu, T. Gene knockout study reveals that cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 2 (OsAPX2) plays a critical role in growth and reproduction in rice under drought, salt and cold stresses. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Wei, A. Plant hormone response to low-temperature stress in cold-tolerant and cold-sensitive varieties of Zanthoxylum bungeanum maxim. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 847202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fu, X. Reprogramming of plant central metabolism in response to abiotic stresses: A metabolomics view. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Mubeen, B.; Hasnain, A.; Rizwan, M.; Adrees, M.; Naqvi, S.; Iqbal, S.; Kamran, M.; El-Sabrout, A.M.; Elansary, H.O.; et al. Role of promising secondary metabolites to confer resistance against environmental stresses in crop plants: Current scenario and future perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 881032. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Shi, H.; Hu, Z.; Liu, A.; Amombo, E.; Chen, L.; Fu, J. Aba is involved in regulation of cold stress response in bermudagrass. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, C.; Prasad, M. Role of drebs in regulation of abiotic stress responses in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 4731–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, R.; Meguro-Maoka, A.; Endo, A.; Shimosaka, E.; Murayama, S.; Nambara, E.; Seo, M.; Kanno, Y.; Abrams, S.R.; Sato, Y. Sustained low abscisic acid levels increase seedling vigor under cold stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A. Auxin: A regulator of cold stress response. Physiol. Plant. 2013, 147, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, F.; Yu, D. Jasmonate regulates the inducer of cbf expression-c-repeat binding factor/dre binding factor1 cascade and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2907–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Halder, K.; Abdin, M.Z.; Majee, M.; Datta, A. Abiotic stress tolerance in plants: Brassinosteroids navigate competently. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Feng, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.W.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Bi, H.G.; Ai, X.Z. Salicylic acid is involved in rootstock-scion communication in improving the chilling tolerance of grafted cucumber. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 693344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, F.; Kopka, J.; Haskell, D.W.; Zhao, W.; Schiller, K.C.; Gatzke, N.; Sung, D.Y.; Guy, C.L. Exploring the temperature-stress metabolome of arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 4159–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, M.R.; Jouve, L.; Hausman, J.F.; Hoffmann, L.; Stewart, J.M. Alteration of oxidative and carbohydrate metabolism under abiotic stress in two rice (Oryza sativa L.) Genotypes contrasting in chilling tolerance. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 164, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgakov, V.P.; Fialko, A.V.; Yugay, Y.A. Involvement of epigenetic factors in flavonoid accumulation during plant cold adaptation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 216, 109096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lv, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, Z. The role of phyto-melatonin and related metabolites in response to stress. Molecules 2018, 23, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dai, X.; Xu, Y.; Luo, W.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, D.; Pan, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; et al. Cold1 confers chilling tolerance in rice. Cell 2015, 160, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Liu, X.; Luo, S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Lin, Q.; Zhu, S.; Wan, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Transcriptional activation and phosphorylation of OsCNGC9 confer enhanced chilling tolerance in rice. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Ming, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, X.; Fu, D.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Gong, Z.; et al. Differential phosphorylation of Ca2+-permeable channel CYCLIC NUCLEOTIDE-GATED CHANNEL20 modulates calcium-mediated freezing tolerance in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 4356–4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zelicourt, A.; Colcombet, J.; Hirt, H. The role of MAPK modules and ABA during abiotic stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, P.; Si, T.; Hsu, C.C.; Wang, L.; Zayed, O.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Dong, J.; Tao, W.A.; et al. MAP kinase cascades regulate the cold response by modulating ice1 protein stability. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yang, L.; Yu, M.; Lai, J.; Wang, C.; Mcneil, D.; Zhou, M.; Yang, C. A novel Zea mays ssp. Mexicana L. MYC-type ICE-like transcription factor gene ZmmICE1, enhances freezing tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 113, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritonga, F.N.; Ngatia, J.N.; Wang, Y.; Khoso, M.A.; Farooq, U.; Chen, S. AP2/ERF, an important cold stress-related transcription factor family in plants: A review. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 1953–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.L.; Lin, L.F.; Hsu, H.C.; Huang, L.F.; Hsiao, C.D.; Chou, M.L. Saussurea involucrata (snow lotus) ICE1 and ICE2 orthologues involved in regulating cold stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.F.; Kang, H.G.; Hong, Q.C.; Park, M.Y.; Sun, H.J.; Kim, J.; Song, P.S.; Lee, H.Y. A novel basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, ZjICE2 from Zoysia japonica confers abiotic stress tolerance to transgenic plants via activating the DREB/CBF regulon and enhancing ros scavenging. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 102, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.S.; Bahk, S.; An, J.; Yoo, Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Chung, W.S. Phosphorylation of the transcriptional repressor MYB15 by mitogen-activated protein kinase 6 is required for freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 6613–6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, X.; Wei, B.; Ji, S. Transcription factor CaNAC1 regulates low-temperature-induced phospholipid degradation in green bell pepper. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 1078–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Ling, J.; Wang, H.; Gu, X.; Huang, S.; Jiang, W. CsWRKY46, a WRKY transcription factor from cucumber, confers cold resistance in transgenic-plant by regulating a set of cold-stress responsive genes in an aba-dependent manner. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 108, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunel, S. Pathway analysis: Aquatic plants imported in 10 eppo countries. Bulletin OEPP 2009, 39, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, C.; Hou, K.; Liu, W. Comparative analyses of plastomes of four Anubias (Araceae) taxa, tropical aquatic plants endemic to africa. Genes 2022, 13, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Wei, J.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, C.; Deng, C.; Zeng, P.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Q. Codon usage patterns and genomic variation analysis of chloroplast genomes provides new insights into the evolution of Aroideae. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4314–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapoom, K.; Chunui, P.; Kanchanapoom, K. Micropropagation of Anubias barteri var. nana from shoot tip culture and the analysis of ploidy stability. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobo. 2012, 40, 148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.L.; Zhao, C.B.; Ding, S.; Zhang, J.F.; Xie, H.; Huang, C.X. First report of root-knot nematode Meloidogyne arenaria infesting roots of Anubias barteri in guangdong, china. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, A.; Minuto, G.; Nicoletti, R.; Gullino, M.L. First report of a blight caused by Rhizoctonia solani on Anubias heterophylla in Italy. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Han, R.; Li, D.; Ling, L.; Luo, H.; Tang, S. A Comparison of two methods for electrical conductivity about plant leaves. J. Guangdong Educ. Insistite 2010, 30, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Araki, M.; Goto, S.; Hattori, M.; Hirakawa, M.; Itoh, M.; Katayama, T.; Kawashima, S.; Okuda, S.; Tokimatsu, T.; et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, D480–D484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Cai, T.; Olyarchuk, J.G.; Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the kegg orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W. Unraveling new functions of superoxide dismutase using yeast model system: Beyond its conventional role in superoxide radical scavenging. J. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sui, L.; Huang, Y.; Geng, C.; Yin, B. Physiological and visible injury responses in different growth stages of winter wheat to ozone stress and the protection of spermidine. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2015, 6, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Caparrós, P.; De Filippis, L.; Gul, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Ozturk, M.; Altay, V.; Lao, M.T. Oxidative stress and antioxidant metabolism under adverse environmental conditions: A review. Bot. Rev. 2021, 87, 421–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, F.; Sayed, M.A.; Shen, X.; Zhou, L.; Liu, X.; Sun, X.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Lu, L.; et al. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic data reveal the cold stress responses molecular mechanisms of two coconut varieties. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1353352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Weng, Y.; Liu, B.; Gao, Q.; Ji, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X. Identification and characterization of regulatory pathways controlling dormancy under lower temperature in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 872839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Song, J. Analysis of widely targeted metabolites of the euhalophyte Suaeda salsa under saline conditions provides new insights into salt tolerance and nutritional value in halophytic species. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Luobu, Z.; Zhuoga, D.; Wei, X.; Tang, Y. Physiological and broadly targeted metabolomic analyses of barley (hordeum vulgare l.) In response to low-temperature stress. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subki, A. The Role of Thiamine in Plants and Current Perspectives in Crop Improvement; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiwal, P.K.; Chhillar, A.K.; Chaudhary, D.; Jaiwal, R. Nutritional Quality Improvement in Plants; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tunc-Ozdemir, M.; Miller, G.; Song, L.; Kim, J.; Sodek, A.; Koussevitzky, S.; Misra, A.N.; Mittler, R.; Shintani, D. Thiamin confers enhanced tolerance to oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecny, T.; Nikoghosyan, M.; Binder, H. Machine learning extracts marks of thiamine’s role in cold acclimation in the transcriptome of Vitis vinifera. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1303542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Yu, X.; Ma, L.; Hu, J.; Liang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yin, H.; Liu, H.; He, X.; Li, D. Transcriptomic response of chinese yew (Taxus chinensis) to cold stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, K.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin biosynthesis in plants: Multiple pathways catalyze tryptophan to melatonin in the cytoplasm or chloroplasts. J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Cheng, T.; Jia, J.; Cao, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, G. Exogenous tryptophan enhances cold resistance of soybean seedlings by promoting melatonin biosynthesis. Physiol. Plantarum 2025, 177, e70189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qi, T.; Cui, C.; Liu, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, S.; Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Lv, H. Effects of different storage temperatures on the quality and metabolome of maize with high moisture content. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 214, 117117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, W.L.; Tohge, T.; Ishizaki, K.; Leaver, C.J.; Fernie, A.R. Protein degradation—An alternative respiratory substrate for stressed plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Uygun, S.; Shiu, S.; Last, R.L. The impact of the branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase complex on amino acid homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1807–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latimer, S.; Li, Y.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Soubeyrand, E.; Fatihi, A.; Elowsky, C.G.; Block, A.; Pichersky, E.; Basset, G.J. Metabolic reconstructions identify plant 3-methylglutaconyl-coa hydratase that is crucial for branched-chain amino acid catabolism in mitochondria. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 95, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Quangkiet, T.; Li, W.; Jian, B.; Yang, X. Integration of transcriptome and metabolome reveals candidate metabolites responding to drought stress in sugarcane. Genomics 2025, 117, 111092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Lian, Y.; Guo, H.; Li, C.; Ren, Y.; Xin, Z.; Lin, T.; Wang, Z. Network analysis of metabolomics, transcriptome and hormones reveals propionic acid-mediated novel survival strategy against drought in wheat. Physiol. Plantarum 2024, 176, e14551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, Q.; Yong, X.; Wu, M.; Jiang, B.; Jia, Y.; Ma, J.; Mou, L.; Tang, S.; Pan, Y. Effects of water deficit on two cultivars of Hibiscus mutabilis: A comprehensive study on morphological, physiological, and metabolic responses. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2024, 217, 109269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Chen, W.; Tang, D.; Wei, C.; Tang, Q. Characterization of the difference between day and night temperatures on the growth, photosynthesis, and metabolite accumulation of tea seedlings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, S.; Verma, S.; Kumar, S.; Kumari, S.; Mishra, B.N. Transcriptional regulation and signalling of cold stress response in plants: An overview of current understanding. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 180, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).