A Dual Regulatory Mechanism of Hormone Signaling and Fungal Community Structure Underpin Dendrobine Accumulation in Dendrobium nobile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Collection

2.2. RNA Sequencing

2.3. Sequencing of Endophytic Fungi

2.4. RNA-Seq Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Elevation Gradient Shaping the Gene Expression Patterns of Dendrobium nobile

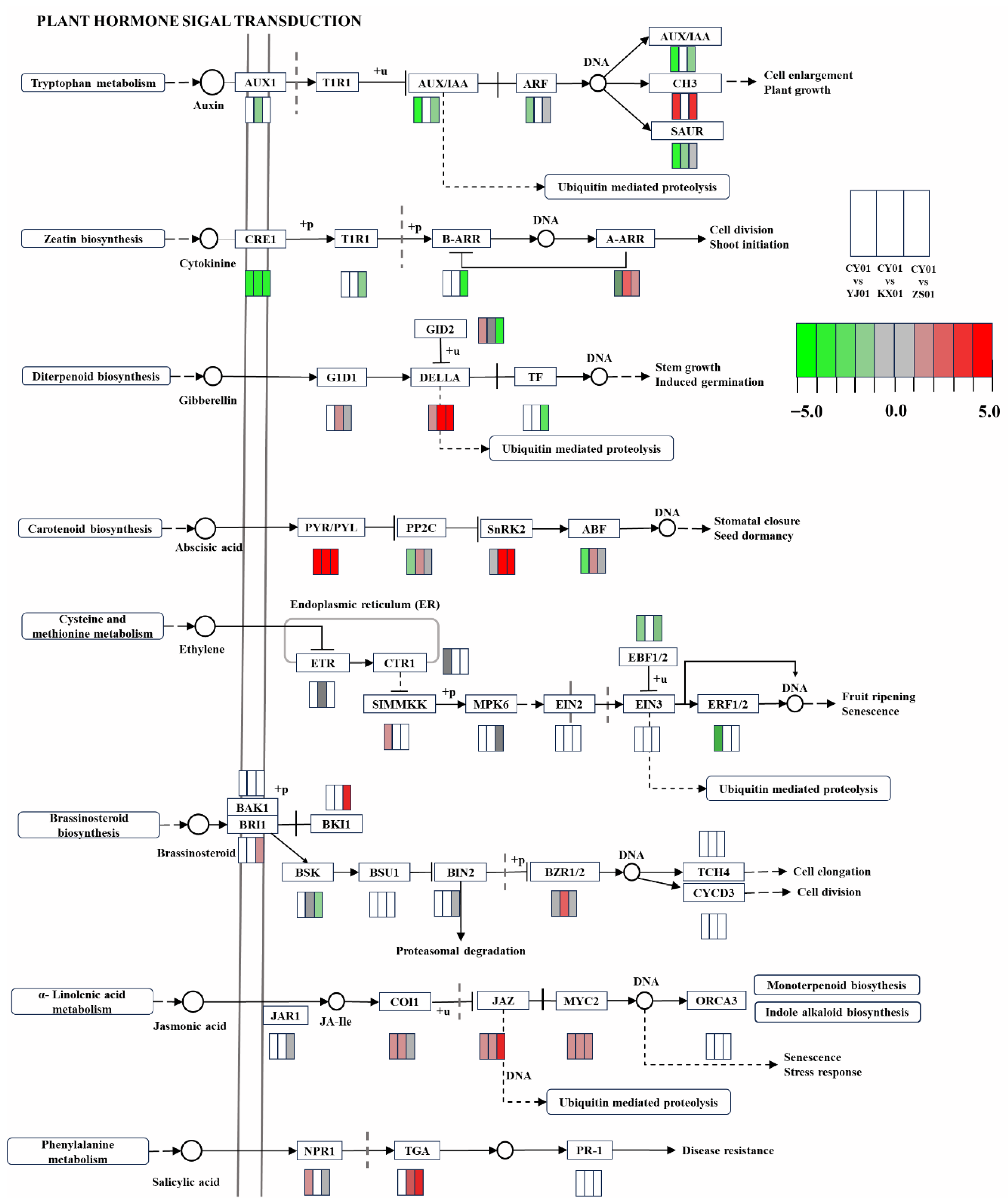

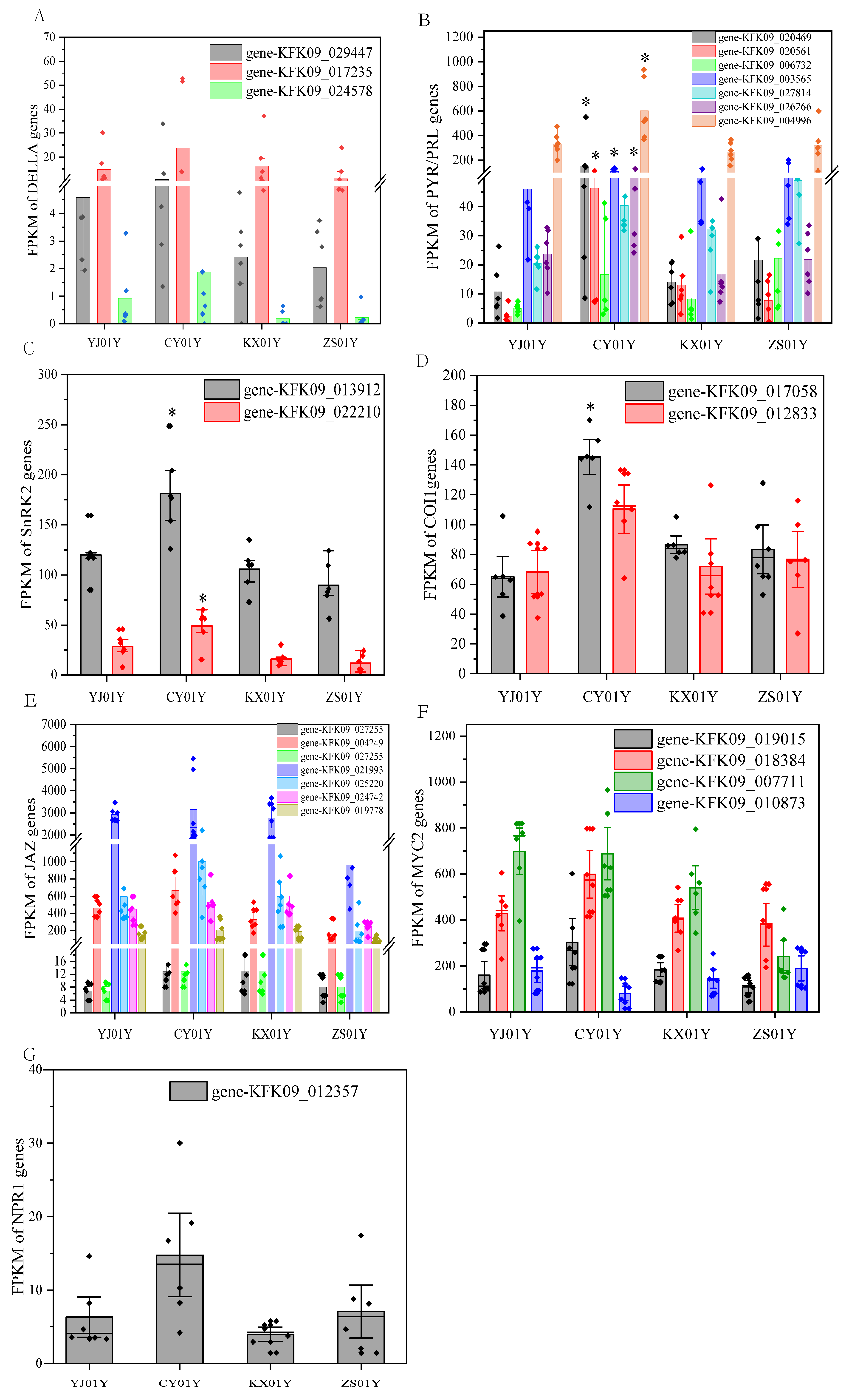

3.2. Plant Hormone Signal Transduction as the Core Regulatory Pathway in the Elevation Response

3.3. Structural Stability and Functional Differentiation of Endophytic Fungal Communities in Dendrobium nobile Along an Elevation Gradient

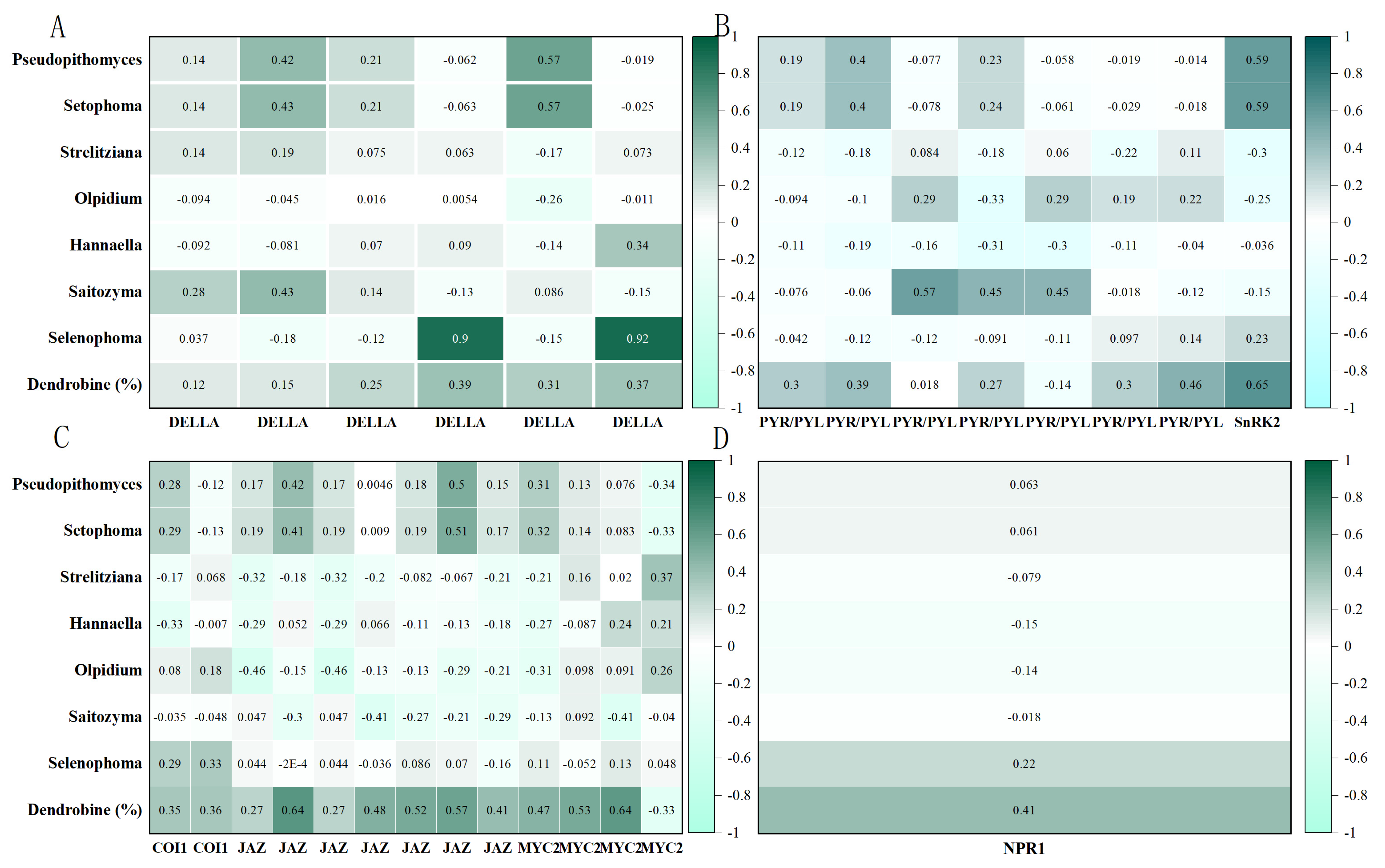

3.4. Elevation-Dependent Functional Variations in Endophytic Fungal Communities Reveal Microbial-Mediated Ecological Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Correlation Between Hormone-Related Gene Expression and Environmental Changes

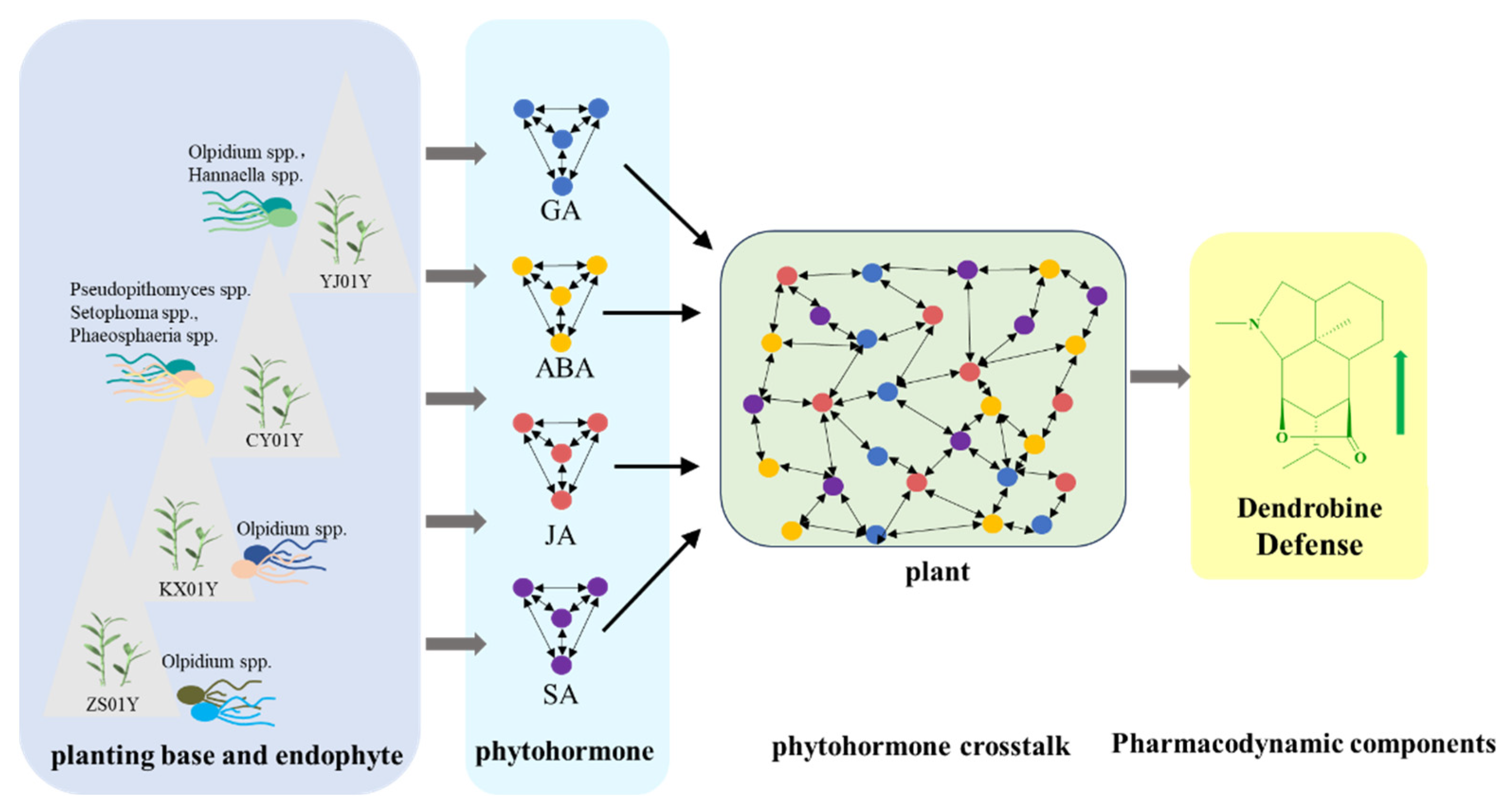

4.2. Endophytic Fungal Populations and Co-Regulation of Metabolite Synthesis by Plant Hormones

4.3. Complexity and Synergy of Hormone Signal Transduction Networks

4.4. Systemic Regulation of Environment-Microbe-Hormone-Metabolism Interactions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| D. nobile | Dendrobium nobile |

| Aux | Auxin |

| CK | Cytokinin |

| GA | Gibberellin |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| ETH | Ethylene |

| BR | Brassinosteroid |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| FUNGuild | Fungi functional guild |

References

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Peng, H.; Cai, Q.; Li, B.; Yang, H.; Zhang, H.; et al. Herbal textual research on Dendrobii caulis in famous classical formulas. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae 2022, 28, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kumar, S.; Vats, S.K.; Ahuja, P.S. Effect of altitude on the primary products of photosynthesis and the associated enzymes in barley and wheat. Photosynth. Res. 2006, 88, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Guo, F.; Shao, C.; Du, D.; Chen, F.; Luo, M. Geodiversity characterization of the Danxiashan UNESCO global geopark of China. Int. J. Geoherit. Parks 2022, 10, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qin, L.; Tan, D.; Wu, D.; Wu, X.; Fan, Q.; Bai, C.; Yang, J.; Xie, J.; He, Y. Fatty acid metabolites of Dendrobium nobile were positively correlated with representative endophytic fungi at altitude. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1128956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terletskaya, N.V.; Erbay, M.; Mamirova, A.; Ashimuly, K.; Korbozova, N.K.; Zorbekova, A.N.; Kudrina, N.O.; Hoffmann, M.H. Altitude-dependent morphophysiological, anatomical, and metabolomic adaptations in Rhodiola linearifolia Boriss. Plants 2024, 13, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.; Chen, Q.; Xu, F.; Fu, H.; Liang, G.; Guo, Q. Exploring the interplay between angiosperm chlorophyll metabolism and environmental factors. Planta 2024, 260, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, M.; Klutsch, J.G.; Cale, J.A.; Hussain, A.; Zhao, S.; Whitehouse, C.; Erbilgin, N. Primary and secondary metabolite profiles of lodgepole pine trees change with elevation, but not with latitude. J. Chem. Ecol. 2021, 47, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Zeng, J.; Ning, Q.; Liu, H.; Bu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, J.; Zhuo, R.; Cui, K.; Qin, Z.; et al. Ferroptosis induction in host rice by endophyte OsiSh-2 is necessary for mutualism and disease resistance in symbiosis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed-Ab-Rahman, S.F.; Arkhipov, A.; Wass, T.J.; Xiao, Y.; Carvalhais, L.C.; Schenk, P.M. Rhizosphere bacteria induce programmed cell death defence genes and signalling in chilli pepper. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 3111–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Ji, X.; Liu, X.; Qin, L.; Tan, D.; Wu, D.; Bai, C.; Yang, J.; Xie, J.; He, Y. Age-dependent dendrobine biosynthesis in Dendrobium nobile: Insights into endophytic fungal interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1294402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taulé, C.; Vaz-Jauri, P.; Battistoni, F. Insights into the early stages of plant-endophytic bacteria interaction. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, K.; Raza, S.A.K.; Mayer, T.; Reichelt, M.; Stuttmann, J.; Hielscher, A.; Wittstock, U.; Gershenzon, J.; Agler, M.T. Glucosinolate structural diversity shapes recruitment of a metabolic network of leaf-associated bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.; Wang, J.; Cao, L.; Yang, D.; Lu, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Fan, Q.; Yang, Z.; et al. UDP-glycosyltransferases play a crucial role in the accumulation of alkaloids and sesquiterpene glycosides in Dendrobium nobile. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waadt, R.; Seller, C.A.; Hsu, P.-K.; Takahashi, Y.; Munemasa, S.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizza, A.; Jones, A.M. The makings of a gradient: Spatiotemporal distribution of gibberellins in plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2019, 47, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantzouni, O.; Alkofer, A.; Falter-Braun, P.; Schwechheimer, C. Growth-regulating factors interact with DELLAs and regulate growth in cold stress. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 1018–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Lee, L.Y.C.; Xia, K.; Yan, Y.; Yu, H. DELLAs modulate jasmonate signaling via competitive binding to JAZs. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, G.-J.; Bressan, R.A.; Song, C.-P.; Zhu, J.-K.; Zhao, Y. Abscisic acid dynamics, signaling, and functions in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, M.; Yan, J.; Khurshid, M.; Weng, W.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, K. Jasmonic acid signaling pathway in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Chen, G.; Luo, G.; Shen, X.; Ouyang, B.; Bie, Z. Transcription factor slwrky50 enhances cold tolerance in tomato by activating the jasmonic acid signaling. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, T.; Szalai, G.; Pál, M. Salicylic acid signalling in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Withers, J.; Li, H.; Zwack, P.J.; Rusnac, D.-V.; Shi, H.; Liu, L.; Yan, S.; Hinds, T.R.; Guttman, M.; et al. Structural basis of salicylic acid perception by Arabidopsis NPR proteins. Nature 2020, 586, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, G. How plants recruit their microbiome? New insights into beneficial interactions. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 40, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosz, F. On the TPPP protein of the enigmatic fungus, Olpidium—Correlation between the incidence of p25alpha domain and that of the eukaryotic flagellum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Rochon, D.; Sekimoto, S.; Wang, Y.; Chovatia, M.; Sandor, L.; Salamov, A.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Stajich, J.E.; Spatafora, J.W. Genome-scale phylogenetic analyses confirm Olpidium as the closest living zoosporic fungus to the non-flagellated, terrestrial fungi. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, C.-Y.; Hamel, C.; St-Arnaud, M. Taxonomy and pathogenicity of Olpidium brassicae and its allied species. Fungal Biol. 2018, 122, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNguild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.; Grillo, M.A. Effects of domestication on plant–microbiome interactions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2022, 63, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichmann, R.; Richards, L.; Schäfer, P. Hormones as go-betweens in plant microbiome assembly. Plant J. 2021, 105, 518–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, N.; Pereira Mendes, M.; Van Wees, S.C.M. Multiple levels of crosstalk in hormone networks regulating plant defense. Plant J. 2021, 105, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, M.; Omae, N.; Tsuda, K. Inter-organismal phytohormone networks in plant-microbe interactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2022, 68, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Lim, J.Y.; Yang, J.; Luskin, M.S. When do Janzen–Connell effects matter? A phylogenetic meta-analysis of conspecific negative distance and density dependence experiments. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Nazir, F.; Maheshwari, C.; Kaur, H.; Gupta, R.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Khan, M.I.R. Plant hormones and secondary metabolites under environmental stresses: Enlightening defense molecules. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Feng, Y.; Qi, F.; Hao, R. Research progress of Piriformospora indica in improving plant growth and stress resistance to plant. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Salicylic acid: The roles in plant immunity and crosstalk with other hormones. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Xiong, N.; Ji, X.; Zhang, D.; Jia, Q.; Qin, L.; Wu, X.; Tan, D.; Xie, J.; He, Y. A Dual Regulatory Mechanism of Hormone Signaling and Fungal Community Structure Underpin Dendrobine Accumulation in Dendrobium nobile. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101366

Zhao Y, Xiong N, Ji X, Zhang D, Jia Q, Qin L, Wu X, Tan D, Xie J, He Y. A Dual Regulatory Mechanism of Hormone Signaling and Fungal Community Structure Underpin Dendrobine Accumulation in Dendrobium nobile. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(10):1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101366

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yongxia, Nian Xiong, Xiaolong Ji, Dongliang Zhang, Qi Jia, Lin Qin, Xingdong Wu, Daopeng Tan, Jian Xie, and Yuqi He. 2025. "A Dual Regulatory Mechanism of Hormone Signaling and Fungal Community Structure Underpin Dendrobine Accumulation in Dendrobium nobile" Biomolecules 15, no. 10: 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101366

APA StyleZhao, Y., Xiong, N., Ji, X., Zhang, D., Jia, Q., Qin, L., Wu, X., Tan, D., Xie, J., & He, Y. (2025). A Dual Regulatory Mechanism of Hormone Signaling and Fungal Community Structure Underpin Dendrobine Accumulation in Dendrobium nobile. Biomolecules, 15(10), 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101366