A Review of CYP-Mediated Drug Interactions: Mechanisms and In Vitro Drug-Drug Interaction Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Reaction Phenotyping

2.1. Overview of Reaction Phenotyping

2.1.1. Fraction Metabolized (fm)

2.1.2. In Vitro Pharmacokinetic Parameters

2.1.3. Drug-Drug Interaction Implications

2.2. Reaction Phenotyping Approaches

2.2.1. Chemical Inhibition Approach

2.2.2. Recombinant CYP Panel (RAF/ISEF Method) Approach

2.2.3. Correlation Analysis Approach

2.2.4. Qualitative-then-Quantitative Approach

2.2.5. Additional Methodologies

2.3. Limitations of Reaction Phenotyping

3. CYP Inhibition

3.1. Mechanisms of CYP Inhibition

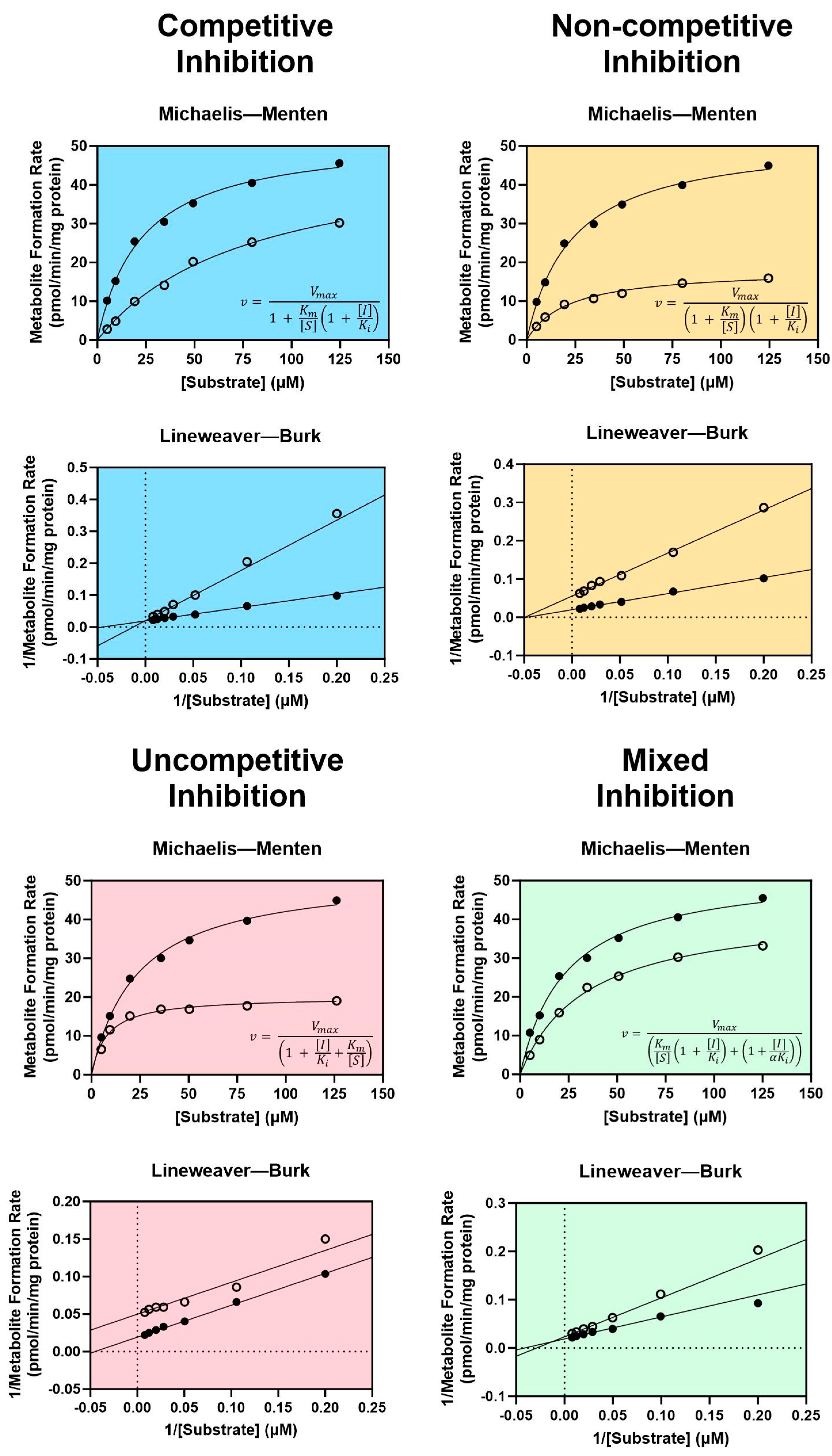

3.1.1. Reversible Inhibition

3.1.2. Quasi-Irreversible Inhibition

3.1.3. Irreversible Inhibition

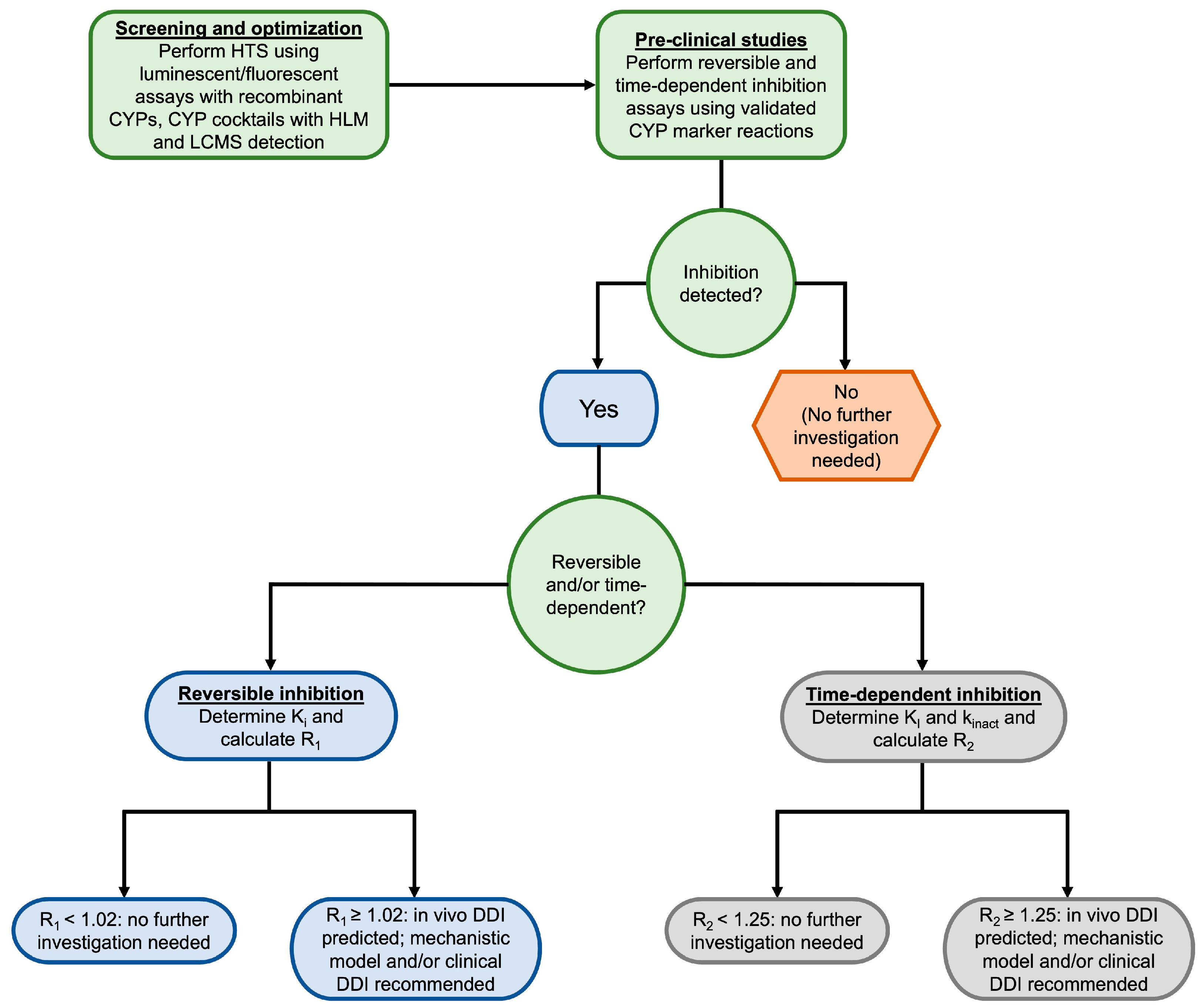

3.2. Methods for Assessing CYP Inhibition

3.2.1. Early High-Throughput Screening

3.2.2. Probe Assays for CYP Inhibition

3.2.3. Model-Based Approaches for Predicting CYP Inhibition

4. CYP Induction

4.1. Mechanisms of CYP Induction

4.1.1. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor

4.1.2. Nuclear Receptors

4.1.3. Crosstalk between Receptors

4.2. Methods for Assessing CYP Induction

4.2.1. Primary Human Hepatocytes

4.2.2. Immortalized Hepatocytes

4.2.3. High Throughput Assays

5. Additional Considerations for Drug Interactions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tornio, A.; Filppula, A.M.; Niemi, M.; Backman, J.T. Clinical Studies on Drug-Drug Interactions Involving Metabolism and Transport: Methodology, Pitfalls, and Interpretation. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 105, 1345–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Di, L. In vitro and in vivo methods to assess pharmacokinetic drug- drug interactions in drug discovery and development. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2020, 41, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinz, M.; Wallace, G.; Sahi, J. Current industrial practices in assessing CYP450 enzyme induction: Preclinical and clinical. AAPS J. 2008, 10, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienkers, L.C.; Heath, T.G. Predicting in vivo drug interactions from in vitro drug discovery data. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- In Vitro Drug Interaction Studies—Cytochrome P450 Enzyme- and Transporter-Mediated Drug Interactions Guidance for Industry; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020.

- Sun, L.; Mi, K.; Hou, Y.; Hui, T.; Zhang, L.; Tao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, L. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Drug-Drug Interactions: Research Methods and Applications. Metabolites 2023, 13, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, U.M.; Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Maeda, K.; Sugiyama, Y. Hepatic and intestinal drug transporters: Prediction of pharmacokinetic effects caused by drug-drug interactions and genetic polymorphisms. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 581–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, M.; Daniel, W.A. The relative contribution of human cytochrome P450 isoforms to the four caffeine oxidation pathways: An in vitro comparative study with cDNA-expressed P450s including CYP2C isoforms. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 76, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcikowski, J.; Daniel, W.A. Perazine at therapeutic drug concentrations inhibits human cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 1A2 (CYP1A2) and caffeine metabolism—An in vitro study. Pharmacol. Rep. 2009, 61, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcikowski, J.; Danek, P.J.; Basinska-Ziobron, A.; Puklo, R.; Daniel, W.A. In vitro inhibition of human cytochrome P450 enzymes by the novel atypical antipsychotic drug asenapine: A prediction of possible drug-drug interactions. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 72, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, E.; Fujita, K.; Kamataki, T.; Arimoto-Kobayashi, S.; Okamoto, K.; Negishi, T. Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 1B1, 1A1 and 1A2 by antigenotoxic compounds, purpurin and alizarin. Mutat. Res. 2002, 508, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, T.; Inoue-Yamamoto, S.; Shiraga, T.; Takagi, A. Effect of antifungal drugs on cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP2E1 activities in human liver microsomes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 1813–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, S.; Murayama, N.; Higuchi, Y.; Yoneda, N.; Yamazaki, H.; Suemizu, H. Comparison of mouse and human cytochrome P450 mediated-drug metabolising activities in hepatic and extrahepatic microsomes. Xenobiotica 2022, 52, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnham, E.A.; Abouda, A.A.; Bissada, J.E.; Nardone-White, D.T.; Beers, J.L.; Lee, J.; Vergne, M.J.; Jackson, K.D. Interindividual Variability in Cytochrome P450 3A and 1A Activity Influences Sunitinib Metabolism and Bioactivation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhu, X.; Badawy, S.; Ihsan, A.; Liu, Z.; Xie, C.; Wang, X. Metabolism and Mechanism of Human Cytochrome P450 Enzyme 1A2. Curr. Drug Metab. 2021, 22, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Kim, S.K. Direct and metabolism-dependent cytochrome P450 inhibition assays for evaluating drug-drug interactions. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2013, 33, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsky, R.L.; Obach, R.S. Validated assays for human cytochrome P450 activities. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.G.; Au, N.T.; Rettie, A.E. P450-Based Drug-Drug Interactions of Amiodarone and its Metabolites: Diversity of Inhibitory Mechanisms. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinger, J.; Woods, C.; Brandt, S.D.; Meyer, M.R.; Maurer, H.H. Cytochrome P450 inhibition potential of new psychoactive substances of the tryptamine class. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 241, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.; Pickwell, G.V.; Guenette, D.K.; Bilir, B.; Quattrochi, L.C. Species differences in hepatocyte induction of CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 by omeprazole. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1999, 18, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.; Albet, C.; Agundez, J.A.; Herrero, E.; Carrillo, J.A.; Marquez, M.; Benitez, J.; Ortiz, J.A. Comparative in vitro and in vivo inhibition of cytochrome P450 CYP1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP3A by H2-receptor antagonists. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 65, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderink, G.J.; Bournique, B.; Stevens, J.; Petry, M.; Martinet, M. Involvement of human CYP1A isoenzymes in the metabolism and drug interactions of riluzole in vitro. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997, 282, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weiss, J.; Sawa, E.; Riedel, K.D.; Haefeli, W.E.; Mikus, G. In vitro metabolism of the opioid tilidine and interaction of tilidine and nortilidine with CYP3A4, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2008, 378, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, E.P.; Wienkers, L.C.; Stapleton, P.L.; Kunze, K.L.; Eaton, D.L. Role of human microsomal and human complementary DNA-expressed cytochromes P4501A2 and P4503A4 in the bioactivation of aflatoxin B1. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Granfors, M.T.; Backman, J.T.; Laitila, J.; Neuvonen, P.J. Tizanidine is mainly metabolized by cytochrome p450 1A2 in vitro. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 57, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, R.O.; Jokinen, E.M.; Javaid, A.; Lehtonen, M.; Raunio, H.; Pentikainen, O.T. Inhibition of human CYP1 enzymes by a classical inhibitor alpha-naphthoflavone and a novel inhibitor N-(3,5-dichlorophenyl)cyclopropanecarboxamide: An in vitro and in silico study. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2020, 95, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.M.; Kuffel, M.J.; Miller, J.K.; Rios, R.; Ames, M.M. Metabolic activation of dacarbazine by human cytochromes P450: The role of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP2E1. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 2192–2197. [Google Scholar]

- Faucette, S.R.; Hawke, R.L.; Lecluyse, E.L.; Shord, S.S.; Yan, B.; Laethem, R.M.; Lindley, C.M. Validation of bupropion hydroxylation as a selective marker of human cytochrome P450 2B6 catalytic activity. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2000, 28, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Desta, Z.; Saussele, T.; Ward, B.; Blievernicht, J.; Li, L.; Klein, K.; Flockhart, D.A.; Zanger, U.M. Impact of CYP2B6 polymorphism on hepatic efavirenz metabolism in vitro. Pharmacogenomics 2007, 8, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiya, Y.; Hagihara, K.; Ito, T.; Tajima, M.; Miura, S.; Kurihara, A.; Farid, N.A.; Ikeda, T. Mechanism-based inhibition of human cytochrome P450 2B6 by ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and the thiolactone metabolite of prasugrel. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009, 37, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsky, R.L.; Astuccio, A.V.; Obach, R.S. Evaluation of 227 drugs for in vitro inhibition of cytochrome P450 2B6. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006, 46, 1426–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faucette, S.R.; Wang, H.; Hamilton, G.A.; Jolley, S.L.; Gilbert, D.; Lindley, C.; Yan, B.; Negishi, M.; LeCluyse, E.L. Regulation of CYP2B6 in primary human hepatocytes by prototypical inducers. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbal-Chaloin, S.; Daujat, M.; Pascussi, J.M.; Pichard-Garcia, L.; Vilarem, M.J.; Maurel, P. Transcriptional regulation of CYP2C9 gene. Role of glucocorticoid receptor and constitutive androstane receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Welch, M.A.; Li, Z.; Mackowiak, B.; Heyward, S.; Swaan, P.W.; Wang, H. Mechanistic Insights of Phenobarbital-Mediated Activation of Human but Not Mouse Pregnane X Receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 96, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madan, A.; Graham, R.A.; Carroll, K.M.; Mudra, D.R.; Burton, L.A.; Krueger, L.A.; Downey, A.D.; Czerwinski, M.; Forster, J.; Ribadeneira, M.D.; et al. Effects of prototypical microsomal enzyme inducers on cytochrome P450 expression in cultured human hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesse, L.M.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Court, M.H.; von Moltke, L.L.; Duan, S.X.; Shader, R.I.; Greenblatt, D.J. CYP2B6 mediates the in vitro hydroxylation of bupropion: Potential drug interactions with other antidepressants. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2000, 28, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Turpeinen, M.; Nieminen, R.; Juntunen, T.; Taavitsainen, P.; Raunio, H.; Pelkonen, O. Selective inhibition of CYP2B6-catalyzed bupropion hydroxylation in human liver microsomes in vitro. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsky, R.L.; Obach, R.S. A comparison of 2-phenyl-2-(1-piperidinyl)propane (ppp), 1,1′,1″-phosphinothioylidynetrisaziridine (thioTEPA), clopidogrel, and ticlopidine as selective inactivators of human cytochrome P450 2B6. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2007, 35, 2053–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.S.; Yang, L.P.; Li, X.T.; Liu, J.P.; Zhou, Z.W.; Zhou, S.F. Human CYP2C8: Structure, substrate specificity, inhibitor selectivity, inducers and polymorphisms. Curr. Drug Metab. 2009, 10, 1009–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Bjorkman, A.; Andersson, T.B.; Ridderstrom, M.; Masimirembwa, C.M. Amodiaquine clearance and its metabolism to N-desethylamodiaquine is mediated by CYP2C8: A new high affinity and turnover enzyme-specific probe substrate. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 300, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, J.W.; Oh, K.S.; Choi, C.S.; Kim, K.H.; Han, W.S.; Yoon, C.N.; Chung, E.S.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, J.G. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor nilotinib selectively inhibits CYP2C8 activities in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 28, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.S.; Neuvonen, M.; Wen, X.; Backman, J.T.; Neuvonen, P.J. Gemfibrozil inhibits CYP2C8-mediated cerivastatin metabolism in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002, 30, 1352–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raucy, J.L.; Mueller, L.; Duan, K.; Allen, S.W.; Strom, S.; Lasker, J.M. Expression and induction of CYP2C P450 enzymes in primary cultures of human hepatocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 302, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VandenBrink, B.M.; Foti, R.S.; Rock, D.A.; Wienkers, L.C.; Wahlstrom, J.L. Evaluation of CYP2C8 inhibition in vitro: Utility of montelukast as a selective CYP2C8 probe substrate. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011, 39, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polasek, T.M.; Elliot, D.J.; Lewis, B.C.; Miners, J.O. Mechanism-based inactivation of human cytochrome P4502C8 by drugs in vitro. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 311, 996–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leemann, T.; Transon, C.; Dayer, P. Cytochrome P450TB (CYP2C): A major monooxygenase catalyzing diclofenac 4′-hydroxylation in human liver. Life Sci. 1993, 52, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, N.; Yajima, K.; Hikawa, M.; Shimura, K.; Ishii, Y.; Takada, M.; Uno, Y.; Utoh, M.; Iwasaki, K.; Yamazaki, H. Assessment of multiple cytochrome P450 activities in metabolically inactivated human liver microsomes and roles of P450 2C isoforms in reaction phenotyping studies. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2018, 39, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Mohutsky, M.A.; Harrelson, J.P.; Wrighton, S.A.; Hall, S.D. Predictions of cytochrome P450-mediated drug-drug interactions using cryopreserved human hepatocytes: Comparison of plasma and protein-free media incubation conditions. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2012, 40, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Shou, M.; Mei, Q.; Rushmore, T.H.; Rodrigues, A.D. Major role of human liver microsomal cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP2C9) in the oxidative metabolism of celecoxib, a novel cyclooxygenase-II inhibitor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 293, 453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Giancarlo, G.M.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Granda, B.W.; von Moltke, L.L.; Greenblatt, D.J. Relative contributions of CYP2C9 and 2C19 to phenytoin 4-hydroxylation in vitro: Inhibition by sulfaphenazole, omeprazole, and ticlopidine. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001, 57, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ferguson, S.S.; Negishi, M.; Goldstein, J.A. Induction of human CYP2C9 by rifampicin, hyperforin, and phenobarbital is mediated by the pregnane X receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 308, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Hashimoto, H.; Takatsu, H.; Tsuda-Tsukimoto, M.; Kume, T. Cocktail-substrate assay system for mechanism-based inhibition of CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A using human liver microsomes at an early stage of drug development. Xenobiotica 2009, 39, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrighton, S.A.; Stevens, J.C.; Becker, G.W.; VandenBranden, M. Isolation and characterization of human liver cytochrome P450 2C19: Correlation between 2C19 and S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993, 306, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kneller, M.B.; Haining, R.L.; Trager, W.F.; Rettie, A.E. (+)-N-3-Benzyl-nirvanol and (−)-N-3-benzyl-phenobarbital: New potent and selective in vitro inhibitors of CYP2C19. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002, 30, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.W.; Desta, Z.; Soukhova, N.V.; Tracy, T.; Flockhart, D.A. In vitro inhibition of the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) system by the antiplatelet drug ticlopidine: Potent effect on CYP2C19 and CYP2D6. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000, 49, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barecki, M.E.; Casciano, C.N.; Johnson, W.W.; Clement, R.P. In vitro characterization of the inhibition profile of loratadine, desloratadine, and 3-OH-desloratadine for five human cytochrome P-450 enzymes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2001, 29, 1173–1175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khojasteh, S.C.; Prabhu, S.; Kenny, J.R.; Halladay, J.S.; Lu, A.Y. Chemical inhibitors of cytochrome P450 isoforms in human liver microsomes: A re-evaluation of P450 isoform selectivity. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2011, 36, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, M.J.; Wurm, R.M.; Muir, K.T.; Generaux, G.T.; St John-Williams, L.; McConn, D.J. An in vitro mechanistic study to elucidate the desipramine/bupropion clinical drug-drug interaction. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 1198–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandenBrink, B.M.; Foti, R.S.; Rock, D.A.; Wienkers, L.C.; Wahlstrom, J.L. Prediction of CYP2D6 drug interactions from in vitro data: Evidence for substrate-dependent inhibition. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2012, 40, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen, K.M.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Von Moltke, L.L.; Obach, R.S.; Greenblatt, D.J. Apparent mechanism-based inhibition of human CYP2D6 in vitro by paroxetine: Comparison with fluoxetine and quinidine. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira, M.; Levine, M.; Chang, T.K.; Mirfazaelian, A.; Bellward, G.D. The effect of cimetidine on dextromethorphan O-demethylase activity of human liver microsomes and recombinant CYP2D6. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otton, S.V.; Ball, S.E.; Cheung, S.W.; Inaba, T.; Rudolph, R.L.; Sellers, E.M. Venlafaxine oxidation in vitro is catalysed by CYP2D6. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996, 41, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Fallon, J.K.; Smith, P.C.; Jackson, K.D. Formation of CYP3A-specific metabolites of ibrutinib in vitro is correlated with hepatic CYP3A activity and 4beta-hydroxycholesterol/cholesterol ratio. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2023, 16, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsky, R.L.; Obach, R.S.; Hyland, R.; Kang, P.; Zhou, S.; West, M.; Geoghegan, K.F.; Helal, C.J.; Walker, G.S.; Goosen, T.C.; et al. Selective mechanism-based inactivation of CYP3A4 by CYP3cide (PF-04981517) and its utility as an in vitro tool for delineating the relative roles of CYP3A4 versus CYP3A5 in the metabolism of drugs. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2012, 40, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissada, J.E.; Truong, V.; Abouda, A.A.; Wines, K.J.; Crouch, R.D.; Jackson, K.D. Interindividual Variation in CYP3A Activity Influences Lapatinib Bioactivation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2019, 47, 1257–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellum, B.H.; Hu, Z.; Nilsen, O.G. The induction of CYP1A2, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 by six trade herbal products in cultured primary human hepatocytes. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 100, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, A.C.; Burchett, W.; Landers, C.; Gualtieri, G.M.; Balesano, A.; Eng, H.; Dantonio, A.L.; Goosen, T.C.; Obach, R.S. Defining the Selectivity of Chemical Inhibitors Used for Cytochrome P450 Reaction Phenotyping: Overcoming Selectivity Limitations with a Six-Parameter Inhibition Curve-Fitting Approach. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2022, 50, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientek, M.A.; Youdim, K. Reaction phenotyping: Advances in the experimental strategies used to characterize the contribution of drug-metabolizing enzymes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.Y.; Wang, R.W.; Lin, J.H. Cytochrome P450 in vitro reaction phenotyping: A re-evaluation of approaches used for P450 isoform identification. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.D. Integrated cytochrome P450 reaction phenotyping: Attempting to bridge the gap between cDNA-expressed cytochromes P450 and native human liver microsomes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 57, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Davis, C.D.; Sinz, M.W.; Rodrigues, A.D. Cytochrome P450 reaction-phenotyping: An industrial perspective. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2007, 3, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantonio, A.L.; Doran, A.C.; Obach, R.S. Intersystem Extrapolation Factors Are Substrate-Dependent for CYP3A4: Impact on Cytochrome P450 Reaction Phenotyping. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2022, 50, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L. Reaction phenotyping to assess victim drug-drug interaction risks. Expert. Opin. Drug Discov. 2017, 12, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, A.C.; Dantonio, A.L.; Gualtieri, G.M.; Balesano, A.; Landers, C.; Burchett, W.; Goosen, T.C.; Obach, R.S. An improved method for cytochrome p450 reaction phenotyping using a sequential qualitative-then-quantitative approach. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2022, 50, 1272–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagar, S.; Argikar, U.A.; Tweedie, D.J. Enzyme kinetics in drug metabolism: Fundamentals and applications. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1113, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientek, M.A.; Goosen, T.C.; Tseng, E.; Lin, J.; Bauman, J.N.; Walker, G.S.; Kang, P.; Jiang, Y.; Freiwald, S.; Neul, D.; et al. In Vitro Kinetic Characterization of Axitinib Metabolism. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016, 44, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.M.; Houston, J.B. Substrate depletion approach for determining in vitro metabolic clearance: Time dependencies in hepatocyte and microsomal incubations. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, M.; Matin, S.B. Kinetics of drug-drug interactions. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1973, 1, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornsson, T.D.; Callaghan, J.T.; Einolf, H.J.; Fischer, V.; Gan, L.; Grimm, S.; Kao, J.; King, S.P.; Miwa, G.; Ni, L.; et al. The conduct of in vitro and in vivo drug-drug interaction studies: A Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) perspective. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnert, T.; Patel, A.; Templeton, I.; Chen, Y.; Lu, C.; Lai, G.; Leung, L.; Tse, S.; Einolf, H.J.; Wang, Y.H.; et al. Evaluation of a New Molecular Entity as a Victim of Metabolic Drug-Drug Interactions—An Industry Perspective. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016, 44, 1399–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drug Development and Drug Interactions|Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-interactions-labeling/drug-development-and-drug-interactions-table-substrates-inhibitors-and-inducers (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Gelboin, H.V.; Krausz, K. Monoclonal antibodies and multifunctional cytochrome P450: Drug metabolism as paradigm. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006, 46, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsky-Fisher, S.L.; Cao, H.; Lu, P.; Gibson, C.R. Effect of cytochromes P450 chemical inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies on human liver microsomal esterase activity. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Nguyen, K.; Fretland, A.J. Utility of intersystem extrapolation factors in early reaction phenotyping and the quantitative extrapolation of human liver microsomal intrinsic clearance using recombinant cytochromes P450. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011, 39, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, Y.A.; Lai, W.G. Impact of Probe Substrate Selection on Cytochrome P450 Reaction Phenotyping Using the Relative Activity Factor. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2017, 45, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obach, R.S. Linezolid Metabolism Is Catalyzed by Cytochrome P450 2J2, 4F2, and 1B1. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2022, 50, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynalda, M.A.; Hauer, M.J.; Wienkers, L.C. Oxidation of the novel oxazolidinone antibiotic linezolid in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2000, 28, 1014–1017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, R.; Kawata, T.; Ueda, S.; Shinbo, T.; Higashimori, M.; Natsume-Kitatani, Y.; Mizuguchi, K. Prediction of the Contribution Ratio of a Target Metabolic Enzyme to Clearance from Chemical Structure Information. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefer, C.E.; Chang, G.; Di, L.; Woody, N.A.; Tess, D.A.; Osgood, S.M.; Kapinos, B.; Racich, J.; Carlo, A.A.; Balesano, A.; et al. The Comparison of Machine Learning and Mechanistic In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation Models for the Prediction of Human Intrinsic Clearance. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 5616–5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youdim, K.A.; Zayed, A.; Dickins, M.; Phipps, A.; Griffiths, M.; Darekar, A.; Hyland, R.; Fahmi, O.; Hurst, S.; Plowchalk, D.R.; et al. Application of CYP3A4 in vitro data to predict clinical drug-drug interactions; predictions of compounds as objects of interaction. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 65, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagling, V.A.; Tjia, J.F.; Back, D.J. Differential selectivity of cytochrome P450 inhibitors against probe substrates in human and rat liver microsomes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998, 45, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirogi, R.; Palacharla, R.C.; Uthukam, V.; Manoharan, A.; Srikakolapu, S.R.; Kalaikadhiban, I.; Boggavarapu, R.K.; Ponnamaneni, R.K.; Ajjala, D.R.; Bhyrapuneni, G. Chemical inhibitors of CYP450 enzymes in liver microsomes: Combining selectivity and unbound fractions to guide selection of appropriate concentration in phenotyping assays. Xenobiotica 2015, 45, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, R.E.; McIntyre, C.J.; Madan, A.; Sanzgiri, U.; Draper, A.J.; Bullock, P.L.; Cook, D.C.; Burton, L.A.; Latham, J.; Nevins, C.; et al. Effects of freezing, thawing, and storing human liver microsomes on cytochrome P450 activity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996, 331, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaut, G.; Papeleu, P.; Vinken, M.; Henkens, T.; Snykers, S.; Vanhaecke, T.; Rogiers, V. Hepatocytes in suspension. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006, 320, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringer, R.; Nicklin, P.L.; Houston, J.B. Reliability of human cryopreserved hepatocytes and liver microsomes as in vitro systems to predict metabolic clearance. Xenobiotica 2008, 38, 1313–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.S.; Yu, H.; Moore, A.; Khetani, S.R.; Tweedie, D. Meeting the Challenge of Predicting Hepatic Clearance of Compounds Slowly Metabolized by Cytochrome P450 Using a Novel Hepatocyte Model, HepatoPac. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2019, 47, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klammers, F.; Goetschi, A.; Ekiciler, A.; Walter, I.; Parrott, N.; Fowler, S.; Umehara, K. Estimation of Fraction Metabolized by Cytochrome P450 Enzymes Using Long-Term Cocultured Human Hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2022, 50, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A.Y. Liver microsomal drug-metabolizing enzyme system: Functional components and their properties. Fed. Proc. 1976, 35, 2460–2463. [Google Scholar]

- Asha, S.; Vidyavathi, M. Role of human liver microsomes in in vitro metabolism of drugs—A review. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010, 160, 1699–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerny, M.A. Prevalence of Non-Cytochrome P450-Mediated Metabolism in Food and Drug Administration-Approved Oral and Intravenous Drugs: 2006–2015. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016, 44, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, B.; Wrighton, S.A.; Mohutsky, M. Reversible mechanisms of enzyme inhibition and resulting clinical significance. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1113, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.H.; Lu, A.Y. Inhibition and induction of cytochrome P450 and the clinical implications. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1998, 35, 361–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibert, E.; Tracy, T.S. Fundamentals of enzyme kinetics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1113, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, M.L.; Kirby, B.; Ragueneau-Majlessi, I.; Galetin, A.; Chien, J.Y.; Einolf, H.J.; Fahmi, O.A.; Fischer, V.; Fretland, A.; Grime, K.; et al. Evaluation of various static in vitro-in vivo extrapolation models for risk assessment of the CYP3A inhibition potential of an investigational drug. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 95, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, S.W.; Einolf, H.J.; Hall, S.D.; He, K.; Lim, H.K.; Ling, K.H.; Lu, C.; Nomeir, A.A.; Seibert, E.; Skordos, K.W.; et al. The conduct of in vitro studies to address time-dependent inhibition of drug-metabolizing enzymes: A perspective of the pharmaceutical research and manufacturers of America. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009, 37, 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, R.J.; Grime, K.; Weaver, R. Time-dependent CYP inhibition. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2007, 3, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, M.; Bellward, G.D. Effect of cimetidine on hepatic cytochrome P450: Evidence for formation of a metabolite-intermediate complex. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1995, 23, 1407–1411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takakusa, H.; Wahlin, M.D.; Zhao, C.; Hanson, K.L.; New, L.S.; Chan, E.C.; Nelson, S.D. Metabolic intermediate complex formation of human cytochrome P450 3A4 by lapatinib. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011, 39, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, A.; Nakamura, K.; Okudaira, N.; Okazaki, O.; Sudo, K. Risk assessment for drug-drug interaction caused by metabolism-based inhibition of CYP3A using automated in vitro assay systems and its application in the early drug discovery process. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2007, 35, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenberg, P.F.; Kent, U.M.; Bumpus, N.N. Mechanism-based inactivation of human cytochromes p450s: Experimental characterization, reactive intermediates, and clinical implications. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Gao, J. Targeting biomolecules with reversible covalent chemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 34, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, R.B. Mechanism-based enzyme inactivators. Methods Enzymol. 1995, 249, 240–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, H.; Kotegawa, T.; Ohashi, K. Duration of drug interactions: Putative time courses after mechanism-based inhibition or induction of CYPs. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 4, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohutsky, M.; Hall, S.D. Irreversible enzyme inhibition kinetics and drug-drug interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1113, 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlokarnik, G.; Grootenhuis, P.D.; Watson, J.B. High throughput P450 inhibition screens in early drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2005, 10, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, S.; Zhang, H. In vitro evaluation of reversible and irreversible cytochrome P450 inhibition: Current status on methodologies and their utility for predicting drug-drug interactions. AAPS J. 2008, 10, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespi, C.L.; Miller, V.P.; Stresser, D.M. Design and application of fluorometric assays for human cytochrome P450 inhibition. Methods Enzymol. 2002, 357, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obach, R.S.L.K. Drug interaction studies in the drug development process: Studies in vitro. In Handbook of Drug Metabolism; Paul, G., Pearson, L.C.W., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 429–466. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, B.; Donzelli, M.; Maseneni, S.; Boess, F.; Roth, A.; Krahenbuhl, S.; Haschke, M. Comparison of Liver Cell Models Using the Basel Phenotyping Cocktail. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.D.; Kukulka, M.J.; Surber, B.W.; Thomas, S.B.; Uchic, J.T.; Rotert, G.A.; Michel, G.; Thome-Kromer, B.; Machinist, J.M. Measurement of liver microsomal cytochrome p450 (CYP2D6) activity using [O-methyl-14C]dextromethorphan. Anal. Biochem. 1994, 219, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikov, M.; Danic, M.; Pavlovic, N.; Stanimirov, B.; Golocorbin-Kon, S.; Stankov, K.; Al-Salami, H. The Role of Drug Metabolites in the Inhibition of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 42, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Wang, R.W.; Lu, A.Y. Utility of recombinant cytochrome p450 enzymes: A drug metabolism perspective. Curr. Drug Metab. 2005, 6, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, W.C.; Chenge, J.; Chen, T. Structural Perspectives of the CYP3A Family and Their Small Molecule Modulators in Drug Metabolism. Liver Res. 2019, 3, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, H. Computational prediction of cytochrome P450 inhibition and induction. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2020, 35, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plonka, W.; Stork, C.; Sicho, M.; Kirchmair, J. CYPlebrity: Machine learning models for the prediction of inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Bioorg Med. Chem. 2021, 46, 116388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racz, A.; Bajusz, D.; Miranda-Quintana, R.A.; Heberger, K. Machine learning models for classification tasks related to drug safety. Mol. Divers. 2021, 25, 1409–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, F.; Goller, A.H.; Hillisch, A. Utility of protein structures in overcoming ADMET-related issues of drug-like compounds. Drug Discov. Today 2011, 16, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Guenthner, T.; Gan, L.S.; Humphreys, W.G. CYP3A4 induction by xenobiotics: Biochemistry, experimental methods and impact on drug discovery and development. Curr. Drug Metab. 2004, 5, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, M.; Backman, J.T.; Neuvonen, M.; Neuvonen, P.J.; Kivisto, K.T. Effects of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of glyburide and glipizide. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, M.; Kivisto, K.T.; Backman, J.T.; Neuvonen, P.J. Effect of rifampicin on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of glimepiride. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000, 50, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.H. CYP induction-mediated drug interactions: In vitro assessment and clinical implications. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 1089–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickins, M. Induction of cytochromes P450. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2004, 4, 1745–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelkonen, O.; Turpeinen, M.; Hakkola, J.; Honkakoski, P.; Hukkanen, J.; Raunio, H. Inhibition and induction of human cytochrome P450 enzymes: Current status. Arch. Toxicol. 2008, 82, 667–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itkin, B.; Breen, A.; Turyanska, L.; Sandes, E.O.; Bradshaw, T.D.; Loaiza-Perez, A.I. New Treatments in Renal Cancer: The AhR Ligands. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, J.D.; Schuetz, E.G.; Thottassery, J.V.; Guzelian, P.S.; Strom, S.; Sun, D. Identification of a novel dexamethasone responsive enhancer in the human CYP3A5 gene and its activation in human and rat liver cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996, 49, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pascussi, J.M.; Drocourt, L.; Gerbal-Chaloin, S.; Fabre, J.M.; Maurel, P.; Vilarem, M.J. Dual effect of dexamethasone on CYP3A4 gene expression in human hepatocytes. Sequential role of glucocorticoid receptor and pregnane X receptor. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 6346–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zeng, L.; Wang, Y.; Tolleson, W.H.; Knox, B.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z.; Guo, L.; Mei, N.; Qian, F.; et al. The expression, induction and pharmacological activity of CYP1A2 are post-transcriptionally regulated by microRNA hsa-miR-132-5p. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 145, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroccio, A.; Wu, D.; Cederbaum, A.I. Ethanol increases content and activity of human cytochrome P4502E1 in a transduced HepG2 cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 203, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Surapureddi, S.; Coulter, S.; Ferguson, S.S.; Goldstein, J.A. Human CYP2C8 is post-transcriptionally regulated by microRNAs 103 and 107 in human liver. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012, 82, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tolleson, W.H.; Yu, D.; Chen, S.; Guo, L.; Xiao, W.; Tong, W.; Ning, B. Regulation of cytochrome P450 expression by microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs: Epigenetic mechanisms in environmental toxicology and carcinogenesis. J. Environ. Sci. Health C Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 2019, 37, 180–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkola, J.; Hukkanen, J.; Turpeinen, M.; Pelkonen, O. Inhibition and induction of CYP enzymes in humans: An update. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 3671–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, Z.; Pavek, P. Regulation of drug-metabolizing cytochrome P450 enzymes by glucocorticoids. Drug Metab. Rev. 2010, 42, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.P.; Bradfield, C.A. The search for endogenous activators of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddick, D.S. Fifty Years of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Research as Reflected in the Pages of Drug Metabolism and Disposition. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2023, 51, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, Z.; Dai, W. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor: Its roles in physiology. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 185, 114428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, U.H.; Lee, S.O.; Safe, S. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR)-active pharmaceuticals are selective AHR modulators in MDA-MB-468 and BT474 breast cancer cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012, 343, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolwick, K.M.; Schmidt, J.V.; Carver, L.A.; Swanson, H.I.; Bradfield, C.A. Cloning and expression of a human Ah receptor cDNA. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993, 44, 911–917. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, K.W. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR): From selected human target genes and crosstalk with transcription factors to multiple AHR functions. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 168, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpiainen, S.; Raffalli-Mathieu, F.; Lang, M.A.; Pelkonen, O.; Hakkola, J. Regulation of the Cyp2a5 gene involves an aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent pathway. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 67, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, S.P.; Saarikoski, S.T.; Hankinson, O. Identification of a novel dioxin-inducible cytochrome P450. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002, 61, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarikoski, S.T.; Rivera, S.P.; Hankinson, O.; Husgafvel-Pursiainen, K. CYP2S1: A short review. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 207, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, R.E.; Wisely, G.B.; Moore, L.B.; Collins, J.L.; Lambert, M.H.; Williams, S.P.; Willson, T.M.; Kliewer, S.A.; Redinbo, M.R. The human nuclear xenobiotic receptor PXR: Structural determinants of directed promiscuity. Science 2001, 292, 2329–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Redinbo, M.R. Activation of the human nuclear xenobiotic receptor PXR by the reverse transcriptase-targeted anti-HIV drug PNU-142721. Protein Sci. 2011, 20, 1713–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchman, C.D.; Chai, S.C.; Chen, T. A current structural perspective on PXR and CAR in drug metabolism. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kliewer, S.A.; Goodwin, B.; Willson, T.M. The nuclear pregnane X receptor: A key regulator of xenobiotic metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnahan, V.E.; Redinbo, M.R. Structure and function of the human nuclear xenobiotic receptor PXR. Curr. Drug Metab. 2005, 6, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.A.; Moore, L.B.; Shenk, J.L.; Wisely, G.B.; Hamilton, G.A.; McKee, D.D.; Tomkinson, N.C.; LeCluyse, E.L.; Lambert, M.H.; Willson, T.M.; et al. The pregnane X receptor: A promiscuous xenobiotic receptor that has diverged during evolution. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000, 14, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.B.; Parks, D.J.; Jones, S.A.; Bledsoe, R.K.; Consler, T.G.; Stimmel, J.B.; Goodwin, B.; Liddle, C.; Blanchard, S.G.; Willson, T.M.; et al. Orphan nuclear receptors constitutive androstane receptor and pregnane X receptor share xenobiotic and steroid ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 15122–15127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.M.; McKee, D.D.; Watson, M.A.; Willson, T.M.; Moore, J.T.; Kliewer, S.A. The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 102, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglich, J.M.; Parks, D.J.; Moore, L.B.; Collins, J.L.; Goodwin, B.; Billin, A.N.; Stoltz, C.A.; Kliewer, S.A.; Lambert, M.H.; Willson, T.M.; et al. Identification of a novel human constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) agonist and its use in the identification of CAR target genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 17277–17283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzameli, I.; Pissios, P.; Schuetz, E.G.; Moore, D.D. The xenobiotic compound 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene is an agonist ligand for the nuclear receptor CAR. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 20, 2951–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.J.; Kapelyukh, Y.; Scheer, N.; Rode, A.; McLaren, A.W.; MacLeod, A.K.; Lin, D.; Wright, J.; Stanley, L.A.; Wolf, C.R. An Extensively Humanized Mouse Model to Predict Pathways of Drug Disposition and Drug/Drug Interactions, and to Facilitate Design of Clinical Trials. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2019, 47, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Cheung, C.; Krausz, K.W.; Shah, Y.M.; Wang, T.; Idle, J.R.; Gonzalez, F.J. A double transgenic mouse model expressing human pregnane X receptor and cytochrome P450 3A4. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 2506–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, J.; Plummer, S.M.; Rode, A.; Scheer, N.; Bower, C.C.; Vogel, O.; Henderson, C.J.; Wolf, C.R.; Elcombe, C.R. Human constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) and pregnane X receptor (PXR) support the hypertrophic but not the hyperplastic response to the murine nongenotoxic hepatocarcinogens phenobarbital and chlordane in vivo. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 116, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheer, N.; Kapelyukh, Y.; Rode, A.; Oswald, S.; Busch, D.; McLaughlin, L.A.; Lin, D.; Henderson, C.J.; Wolf, C.R. Defining Human Pathways of Drug Metabolism In Vivo through the Development of a Multiple Humanized Mouse Model. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 1679–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, M.; Naito, S.; Yokoi, T. Tissue-specific mRNA expression profiles of human nuclear receptor subfamilies. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2004, 19, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miki, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Tazawa, C.; Blumberg, B.; Sasano, H. Steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR), cytochrome P450 3A4 and multidrug resistance gene 1 in human adult and fetal tissues. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2005, 231, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, B.; Redinbo, M.R.; Kliewer, S.A. Regulation of CYP3A gene transcription by the pregnane x receptor. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002, 42, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyushova, L.S.; Perepechaeva, M.L.; Grishanova, A.Y. The Role of CYP3A in Health and Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toriyabe, T.; Nagata, K.; Takada, T.; Aratsu, Y.; Matsubara, T.; Yoshinari, K.; Yamazoe, Y. Unveiling a new essential cis element for the transactivation of the CYP3A4 gene by xenobiotics. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 75, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, K.; Wan, Y.J. Retinoids activate RXR/CAR-mediated pathway and induce CYP3A. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 79, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsit, Y.E.; Negishi, M. CAR and PXR: The xenobiotic-sensing receptors. Steroids 2007, 72, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, B.; Moore, L.B.; Stoltz, C.M.; McKee, D.D.; Kliewer, S.A. Regulation of the human CYP2B6 gene by the nuclear pregnane X receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 60, 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitz, J.E.; Kalgutkar, A.S.; Nulick, K.; Johnson, N.; Lin, Z.; Goosen, T.C.; Weng, Y. Establishing Transcriptional Signatures to Differentiate PXR-, CAR-, and AhR-Mediated Regulation of Drug Metabolism and Transport Genes in Cryopreserved Human Hepatocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2018, 365, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.Y.; Shen, J.H.; Lemler, S.M.; Skaar, T.C.; Li, L.; Blievernicht, J.; Zanger, U.M.; Kim, K.B.; Shin, J.G.; Flockhart, D.A.; et al. Rifampin enhances cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2B6-mediated efavirenz 8-hydroxylation in healthy volunteers. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2016, 31, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahmi, O.A.; Shebley, M.; Palamanda, J.; Sinz, M.W.; Ramsden, D.; Einolf, H.J.; Chen, L.; Wang, H. Evaluation of CYP2B6 Induction and Prediction of Clinical Drug-Drug Interactions: Considerations from the IQ Consortium Induction Working Group—An Industry Perspective. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016, 44, 1720–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Daujat-Chavanieu, M.; Gerbal-Chaloin, S. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor decreases rifampicin-induced CYP3A4 expression in primary human hepatocytes and HepaRG. Toxicol. Lett. 2017, 277, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Cunningham, M.; Kim, S.; Burn, T.; Lin, J.; Sinz, M.; Hamilton, G.; Rizzo, C.; Jolley, S.; Gilbert, D.; et al. CYP3A4 induction by drugs: Correlation between a pregnane X receptor reporter gene assay and CYP3A4 expression in human hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002, 30, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Lin, J.; Fiske, W.D.; Dai, R.; Yang, T.J.; Kim, S.; Sinz, M.; LeCluyse, E.; Solon, E.; Brennan, J.M.; et al. Concurrent induction and mechanism-based inactivation of CYP3A4 by an L-valinamide derivative. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsui, H.; Kuramoto, S.; Ozeki, K. Evaluation of Methods to Assess CYP3A Induction Risk in Clinical Practice Using in Vitro Induction Parameters. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 44, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, L.; Abernethy, D.R.; Rekic, D.; Reynolds, K.S.; Galetin, A.; Huang, S.M. In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation of Metabolism- and Transporter-Mediated Drug-Drug Interactions-Overview of Basic Prediction Methods. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 2209–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.C.; Rollison, H.; Johansson, S.; Kanebratt, K.P.; Lambert, C.; Vishwanathan, K.; Andersson, T.B. Managing the Risk of CYP3A Induction in Drug Development: A Strategic Approach. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2017, 45, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatow, V.Y.; Lecluyse, E.L.; Griffith, L.G.; Rusyn, I. In vitro models for liver toxicity testing. Toxicol. Res. 2013, 2, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Braver-Sewradj, S.P.; den Braver, M.W.; Vermeulen, N.P.; Commandeur, J.N.; Richert, L.; Vos, J.C. Inter-donor variability of phase I/phase II metabolism of three reference drugs in cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes in suspension and monolayer. Toxicol. Vitr. 2016, 33, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, C.C.; Dankers, A.C.A.; Lauschke, V.M.; Sison-Young, R.; Jenkins, R.; Rowe, C.; Goldring, C.E.; Park, K.; Regan, S.L.; Walker, T.; et al. Comparison of Hepatic 2D Sandwich Cultures and 3D Spheroids for Long-term Toxicity Applications: A Multicenter Study. Toxicol. Sci. 2018, 162, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, C.; Gerrard, D.T.; Jenkins, R.; Berry, A.; Durkin, K.; Sundstrom, L.; Goldring, C.E.; Park, B.K.; Kitteringham, N.R.; Hanley, K.P.; et al. Proteome-wide analyses of human hepatocytes during differentiation and dedifferentiation. Hepatology 2013, 58, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, C.C.; Hendriks, D.F.; Moro, S.M.; Ellis, E.; Walsh, J.; Renblom, A.; Fredriksson Puigvert, L.; Dankers, A.C.; Jacobs, F.; Snoeys, J.; et al. Characterization of primary human hepatocyte spheroids as a model system for drug-induced liver injury, liver function and disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvinen, E.; Hammer, H.S.; Potz, O.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Stage, T.B. 3D Spheroid Primary Human Hepatocytes for Prediction of Cytochrome P450 and Drug Transporter Induction. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 113, 1284–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.B.; Rose, K.A.; Sadagopan, N.; Sahi, J.; de Morais, S.M. Induction of drug metabolism enzymes and MDR1 using a novel human hepatocyte cell line. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 309, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripp, S.L.; Mills, J.B.; Fahmi, O.A.; Trevena, K.A.; Liras, J.L.; Maurer, T.S.; de Morais, S.M. Use of immortalized human hepatocytes to predict the magnitude of clinical drug-drug interactions caused by CYP3A4 induction. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 1742–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariparsad, N.; Carr, B.A.; Evers, R.; Chu, X. Comparison of immortalized Fa2N-4 cells and human hepatocytes as in vitro models for cytochrome P450 induction. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aninat, C.; Piton, A.; Glaise, D.; Le Charpentier, T.; Langouet, S.; Morel, F.; Guguen-Guillouzo, C.; Guillouzo, A. Expression of cytochromes P450, conjugating enzymes and nuclear receptors in human hepatoma HepaRG cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antherieu, S.; Chesne, C.; Li, R.; Camus, S.; Lahoz, A.; Picazo, L.; Turpeinen, M.; Tolonen, A.; Uusitalo, J.; Guguen-Guillouzo, C.; et al. Stable expression, activity, and inducibility of cytochromes P450 in differentiated HepaRG cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2010, 38, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanebratt, K.P.; Andersson, T.B. HepaRG cells as an in vitro model for evaluation of cytochrome P450 induction in humans. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinnity, D.F.; Zhang, G.; Kenny, J.R.; Hamilton, G.A.; Otmani, S.; Stams, K.R.; Haney, S.; Brassil, P.; Stresser, D.M.; Riley, R.J. Evaluation of multiple in vitro systems for assessment of CYP3A4 induction in drug discovery: Human hepatocytes, pregnane X receptor reporter gene, and Fa2N-4 and HepaRG cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009, 37, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grime, K.; Ferguson, D.D.; Riley, R.J. The use of HepaRG and human hepatocyte data in predicting CYP induction drug-drug interactions via static equation and dynamic mechanistic modelling approaches. Curr. Drug Metab. 2010, 11, 870–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, A.; Kato, M.; Sekiguchi, N.; Mitsui, T.; Takeda, K.; Aso, Y. In vitro model for the prediction of clinical CYP3A4 induction using HepaRG cells. Xenobiotica 2009, 39, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guengerich, F.P. Human Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. In Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry; Ortiz de Montellano, P.R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 523–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guengerich, F.P. Cytochrome P-450 3A4: Regulation and role in drug metabolism. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999, 39, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekroos, M.; Sjogren, T. Structural basis for ligand promiscuity in cytochrome P450 3A4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 13682–13687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Ong, S.S.; Chai, S.C.; Chen, T. Role of CAR and PXR in xenobiotic sensing and metabolism. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2012, 8, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, C.K.; Chrisman, C.R.; Baciewicz, A.M.; Self, T.H. Rifampin and rifabutin drug interactions: An update. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002, 162, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasaka, Y.; Chang, S.Y.; Grubb, M.F.; Peng, C.C.; Thummel, K.E.; Isoherranen, N.; Rodrigues, A.D. Effect of CYP3A5 expression on the inhibition of CYP3A-catalyzed drug metabolism: Impact on modeling CYP3A-mediated drug-drug interactions. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2013, 41, 1566–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmann, R.; Smuszkiewicz, P. Pharmacokinetics of antifungal drugs: Practical implications for optimized treatment of patients. Infection 2017, 45, 737–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, M.; Grogan, J.; Mancewicz, J.A.; Krausz, K.W.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Gelboin, H.V.; Korzekwa, K.R. Activation of CYP3A4: Evidence for the simultaneous binding of two substrates in a cytochrome P450 active site. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 6450–6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutzler, J.M.; Tracy, T.S. Atypical kinetic profiles in drug metabolism reactions. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002, 30, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leow, J.W.H.; Chan, E.C.Y. Atypical Michaelis-Menten kinetics in cytochrome P450 enzymes: A focus on substrate inhibition. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 169, 113615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CYP Enzyme | Substrate Marker Reactions | Inhibitors | Inducers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1A2 | Caffeine 3-N-demethylation [9,10,11] 7-ethoxyresorufin O-deethylation [12,13,14] Phenacetin O-deethylation [15,16,17,18] | Amiodarone [19,20] | Omeprazole [15,21] |

| Cimetidine [22,23,24] | |||

| Furafylline [15,18,25,26] | |||

| α-Naphthoflavone [27,28] | |||

| 2B6 | Bupropion hydroxylation [17,18,29] Efavirenz hydroxylation [30] | Clopidogrel [31,32] | Phenobarbital [33,34,35,36] |

| Ticlopidine [31,32] | |||

| Sertraline [32,37] | |||

| Thiotepa [31,38] | |||

| 2-phenyl-2-(1-piperidyl)propane [32,39] | |||

| 2C8 | Amodiaquine N-deethylation [18,40,41] Paclitaxel 6α-hydroxylation [40,42] | Gemfibrozil [43] | Rifampicin [34,36,44] |

| Montelukast [45] | |||

| Phenelzine [46] | |||

| 2C9 | Diclofenac 4′-hydroxylation [18,47,48,49] | Sulfaphenazole [18,49,50,51] | Rifampicin [34,36,44,52] |

| S-warfarin 7-hydroxylation [48] | Tienilic acid [17,53] | ||

| 2C19 | S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation [54] | N-3-benzylnirvanol [55] | Rifampicin [36] |

| Ticlopidine [51,56] | |||

| Loratadine [57] | |||

| Nootkatone [58] | |||

| 2D6 | Bufuralol 1′-hydroxylation [49,59] | Quinidine [18,49,60,61] | |

| Dextromethorpan O-demethylation [18,62] | Paroxetine [61,63] | ||

| 3A4/5 | Midazolam 1′-hydroxylation [17,49,64,65,66] | Ketoconazole [17,49,50,64,65,66] | Rifampicin [15,34,36,67] |

| Testosterone 6β-hydroxylation [17] | CYP3Cide (3A4 specific) [65,66] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Beers, J.L.; Geffert, R.M.; Jackson, K.D. A Review of CYP-Mediated Drug Interactions: Mechanisms and In Vitro Drug-Drug Interaction Assessment. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14010099

Lee J, Beers JL, Geffert RM, Jackson KD. A Review of CYP-Mediated Drug Interactions: Mechanisms and In Vitro Drug-Drug Interaction Assessment. Biomolecules. 2024; 14(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jonghwa, Jessica L. Beers, Raeanne M. Geffert, and Klarissa D. Jackson. 2024. "A Review of CYP-Mediated Drug Interactions: Mechanisms and In Vitro Drug-Drug Interaction Assessment" Biomolecules 14, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14010099

APA StyleLee, J., Beers, J. L., Geffert, R. M., & Jackson, K. D. (2024). A Review of CYP-Mediated Drug Interactions: Mechanisms and In Vitro Drug-Drug Interaction Assessment. Biomolecules, 14(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14010099