Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of death and illness in Europe and worldwide, responsible for a staggering 47% of deaths in Europe. Over the past few years, there has been increasing evidence pointing to bioactive sphingolipids as drivers of CVDs. Among them, most studies place emphasis on the cardiovascular effect of ceramides and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), reporting correlation between their aberrant expression and CVD risk factors. In experimental in vivo models, pharmacological inhibition of de novo ceramide synthesis averts the development of diabetes, atherosclerosis, hypertension and heart failure. In humans, levels of circulating sphingolipids have been suggested as prognostic indicators for a broad spectrum of diseases. This article provides a comprehensive review of sphingolipids’ contribution to cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and metabolic diseases, focusing on the latest experimental and clinical findings. Cumulatively, these studies indicate that monitoring sphingolipid level alterations could allow for better assessment of cardiovascular disease progression and/or severity, and also suggest them as a potential target for future therapeutic intervention. Some approaches may include the down-regulation of specific sphingolipid species levels in the circulation, by inhibiting critical enzymes that catalyze ceramide metabolism, such as ceramidases, sphingomyelinases and sphingosine kinases. Therefore, manipulation of the sphingolipid pathway may be a promising strategy for the treatment of cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases.

1. Introduction

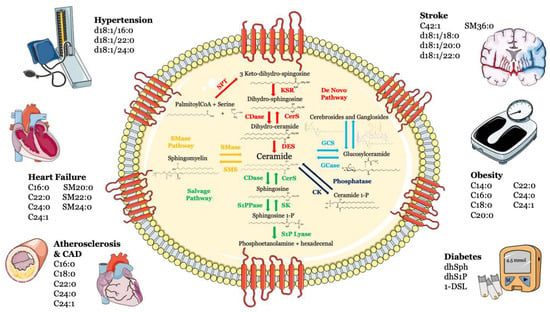

Sphingolipids, including sphingosine, ceramide, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and ceramide-1-phosphate, are bioactive components in cell membranes that participate in and regulate numerous biological processes, such as cell proliferation and survival, maturation, senescence and apoptosis [1,2,3]. Sphingolipids can be synthesized via the de novo synthesis pathway, but they can also be formed through the sphingomyelinase pathway and/or the so-called “salvage” pathway (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Metabolism and structure of sphingolipids and their implication in cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases. Sphingolipid metabolism and structure are illustrated inside the cell. Ceramide is the heart of the sphingolipid metabolic pathway. Ceramide can be synthesized through several steps: (i) de novo synthesis pathway starting from l-serine and palmitoyl-CoA (red); (ii) SMase pathway, through hydrolysis of sphingomyelin (yellow); (iii) salvage pathway, long-chain sphingoid bases are reused to form ceramide through the action of ceramide synthase (green); (iv) or through hydrolysis of glycosphingolipids and sulfatites (azure). Ceramide can also be synthesized from ceramide-1-phosphate through the action of ceramide-1-phosphate phosphatase (blue). The main cardiovascular diseases and risk factors in which sphingolipids may be used as biomarkers are summarized outside the cell. Abbreviations: serine palmitoyl-CoA-acyltransferase (SPT), 3-ketosphinganine reductase (KSR), (dihydro)-ceramide synthase (CerS), ceramide desaturase (DES), ceramide kinase (CK), glucosylceramide synthase (GCS), glucosyl ceramidase (GCase), ceramidase (CDase), sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase (S1P lyase), sphingosine kinase (SK), sphingosine 1-phosphate phosphatase (S1PPase), sphingomyelin (SM) synthase (SMS), sphingomyelinase (SMase).

Over the last decade, growing numbers of studies have highlighted the role of sphingolipids in the pathogenesis of CVDs [4,5,6,7,8,9]. In mice and rats, repression of sphingolipid biosynthesis attenuates cardiometabolic risk factors, including glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, diabetes, hypertension, atherosclerotic plaque development, arterial dysfunction and heart failure (HF) [10,11,12,13,14]. Data from patients have also indicated associations of tissue and circulating levels of sphingolipids with increased risk of CVDs, including HF, hypertension, metabolic syndrome and coronary artery disease (CAD) [12,15,16,17,18].

The aim of this article is to summarize recent clinical and experimental findings suggesting sphingolipids as potential cardiovascular risk biomarkers and drug targets.

2. Atherosclerosis and Coronary Artery Disease

Sphingolipids, and in particular, ceramide, can contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [19], an inflammatory and potentially lethal condition characterized by the generation of atheromatous plaques, consisting of cholesterol and other lipids [20], in medium- and large-sized arteries [21]. Ceramide can be generated from sphingomyelin (SM) via the activation of the de novo synthesis pathway or from sphingomyelinases (SMases). The development of an atherosclerotic lesion involves a large number of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) [22], which, along with oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), can stimulate ceramide generation via sphingomyelin hydrolysis [23]. In their work, Laulederkind and colleagues [24] demonstrated that C2-ceramid is able to induce interleukin 6 (IL-6) gene expression in human fibroblasts, a cytokine known to be involved in inflammation [25] and for its ability to induce the liver’s production of the greatest predictor of future cardiovascular risk that has direct proinflammatory effects: C-reactive protein [26]. It has also been proven that oxLDL stimulates an enzymatic cascade that includes neutral SMase, ceramidase and sphingosine kinase, thereby promoting the production of S1P to stimulate mitogenesis [27] and proliferation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) [28,29], a hallmark of atherosclerotic lesion development. Moreover, Li and collaborators [30] showed that endogenous ceramides contribute to the subendothelial infiltration of oxLDL into the vessel wall.

Deficiency in or pharmacologic inhibition of neutral SMase2 in an Apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-null mouse model resulted in a decrease in atherosclerotic lesions and macrophage infiltration and lipid deposition via a mechanism involving the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway [31]. S1P is also released from activated platelets and interacts with endothelial cells during the atherosclerotic process [32]. It has also been proven that S1P can induce platelet shape change and aggregation [33] and that ceramide stimulates the release of the plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) [23,34,35], contributing, once again, to a variety of pathophysiological processes, such as thrombosis and atherosclerosis. In line, high endogenous S1P levels exaggerated atherosclerotic lesion development and increased plasma cholesterol levels in ApoE-null mice [36].

As mentioned above, tumor necrosis factor is able to activate a neutral sphingomyelinase [37], causing an increase in ceramide that, during the inflammation process, can act as an intermediate in TNF signaling in endothelial cells [38]. Furthermore, treatment of these cells with a water-soluble synthetic C8-ceramide or sphingomyelinase C led to the evidence that ceramide can induce NF-κB translocation to the nucleus and an increase in surface expression of E-selectin [38], which mediates the interaction of leukocytes with endothelium [39], thus, contributing to the initial stage of the disease. These sphingolipids can also evoke endothelial cell apoptosis [40,41,42], causing plaque erosion and unleashing other complications combined with the atherosclerotic process [23].

Another mechanism involved in the plaque formation induced by sphingolipids is represented by ceramide’s inclination to self-aggregate. It has a primary role in atherosclerosis’s onset since it contributes to the accumulation of LDL rich in this sphingolipid [43,44]. This notion is also supported by the evidence that ceramide content in LDL present in the atheromatous plaques is significantly higher than the plasma LDL and this sphingolipid was found only in aggregated LDL [45]. Furthermore, ceramide and other sphingolipids’ levels were increased in human atherosclerotic plaques and associated with plaque inflammation and instability [46,47].

Several clinical trials have highlighted the role of sphingolipids in atherosclerosis, reporting increased plasma concentrations of ceramides, sphingomyelins, sphinganine and sphingosine in patients with CAD [48]. An interesting clinical trial through a large-scale metabolomic analysis on a total of 200 patients tried to identify potential biomarkers for early-stage atherosclerosis. Analyses showed increased levels of 24 metabolites and a decrease in another 18 metabolites. Overall, nine metabolites were found to be suitable as combinatorial biomarkers, with an acceptable diagnostic accuracy [49]. In patients with CAD, the new PCSK9 has also been shown to significantly alter plasma lipidome composition and not only lipoprotein particles (LDL-C). Although the target for CVD prevention remains the lowering of LDL-C, the lipidome represents an asset for cardiovascular risk prediction and modification [50]. Similarly, treatment with fenofibrate showed not only the expected decrease in triglycerides, LDL-C and total cholesterol, but also an independent reduction in ceramide levels and of plasma apoC-II, apoC-III, apoB100 and SMase, with an increase in apoA-II and adiponectin levels [51]. A bi-ethnic angiographic case-control study showed increased plasma levels of SM in patients with coronary artery disease [48]. This was observed in both African-American and white participants, with a multivariate logistic regression analysis independent of other cardiovascular risk factors [48]. Using an unbiased machine learning approach, Poss et al. [52] identified 30 sphingolipids that were significantly elevated in the serum of patients with CAD (n = 462) compared with healthy controls (n = 212). Circulating ceramides were strongly correlated with disease severity since their levels were higher in subjects with CAD severity and major adverse cardia and cerebrovascular events (MACEs) [52,53,54,55]. Moreover, elevated levels of specific ceramide species (C16:0, C18:0, C22:0, C24:0 and C24:1) were associated with increased thrombotic risk, adverse CAD incidents and all-cause mortality [8,56,57,58,59,60]. Based on these findings, the authors of the study suggest serum ceramides as powerful biomarkers of CAD that could be useful to improve risk stratification [52].

3. Heart Failure

One of the major mechanisms connecting ceramides to impaired cardiomyocyte function can be ascribed to their pathological actions in mitochondria, where they can accumulate, increase permeability to cytochrome c and ultimately initiate apoptosis [12,61,62]. Accumulation of ceramide has been reported to drive insulin resistance, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in human-induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes [63]. Experimental myocardial infarction (MI) performed on C57B/L6 mice induced altered sphingolipid metabolism, with increased expression of the first and rate-limiting enzyme in the de novo pathway, serine palmitoyl transferase (SPT), and consequently increased ceramide levels [12]. In the same study, failing myocardium had elevated levels of the serine-palmitoyl transferase long-chain 2 subunit (SPTLC2), and its overexpression resulted in a marked accumulation of cellular ceramide, together with increased apoptosis in a human cardiomyocyte cell line. These observations suggest a role for the de novo ceramide synthesis pathway. Accordingly, inhibition of SPT with myriocin decreased C16:0, C24:1 and C24:0 ceramide accumulation, prevented adverse cardiac remodeling [12] and reduced infarcted area, oxidative stress and inflammatory markers [64]. In line with these in vivo findings, lipidomic analysis revealed significantly increased ceramide levels in the myocardium and serum of patients with advanced HF [12], and its circulating levels were associated with adverse cardiac outcome during a median follow-up of 4.7 years [16]. Recently, sphingolipid metabolism gene dysregulation was found in HF human cardiac tissue, with the major changes occurring in the expression of genes involved in the de novo and salvage pathways [65]. Even more interesting, the authors demonstrated, for the first time, that, along with ceramide elevation, S1P is enhanced in HF cardiac tissue [65].

Only one clinical trial has associated plasma ceramides and sphingomyelins with heart failure. In this study, plasma Cer and SM species were analyzed with Cox regression to highlight the risk of incident HF. In a large cohort of 4249 older adults, higher plasma levels of ceramide and sphingomyelin were indicative of increased heart-failure risk, in-dependently of sex, age, race, body mass index (BMI) and baseline coronary heart disease, whereas higher levels of C22:0, SM20:0, SM22:0 and SM24:0 were indicative of a lower risk of heart failure [66].

4. Hypertension

Hypertension is a major cause of death and disability in Europe and in the rest of the World, responsible for an estimated 8 million deaths and 148 million disability life-years lost worldwide in 2015 [67].

Although some clinical and experimental studies reported altered sphingolipid metabolism in hypertension [7,68,69], the mechanism through which S1P promotes disease onset and propagation remains mainly elusive. Previous work conducted by Spijkers et al. [7] showed increased total ceramide and sphingosine circulating levels in a spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) model. Moreover, the authors observed, for the first time, an increase in ceramide level in patients with stage 1–3 hypertension and its concentration correlated with disease severity [7].

Deficiency in the rate-limiting enzymes in the generation of S1P, sphingosine kinases (SphK) 1 and 2, resulted in a significant decrease in blood pressure as well as artery contractility in angiotensin II (AngII)-induced hypertension in the wild type (C57BL/6J) [68,70]. Accordingly, S1P plasma levels were positively correlated with systolic BP in in a murine model of AngII-mediated slowly developing hypertension [71]. Yogi and co-workers [69] reported a novel molecular process that, starting from S1P, induced vascular inflammation in stroke-prone SHR rats (SHRSP) through epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFR) transactivation. The authors demonstrated that these effects were abrogated by the use of VPC23019, a potent S1P receptor (S1PR) 1 inhibitor, thus, indicating the role of the S1P1 receptor in this process.

Recently, our group elucidated the molecular mechanism by which dysregulated sphingolipid metabolism is involved in hypertension [72]. We demonstrated that in vivo administration of recombinant sortilin—a member of the vacuolar protein sorting 10 protein family of sorting receptors—altered the sphingolipid balance by initiating a signaling cascade that, starting from acid SMase activation, leads to increased levels of S1P at the expense of ceramides [72]. Mechanistically, sortilin acts as a pathological modulator of bioactive sphingolipids, through which it impairs endothelial function and leads to high blood-pressure levels, effects that were mediated by an oxidative-stress-dependent activation mechanism [72].

We and others [71,72] have shown that circulating levels of S1P are elevated in humans with arterial hypertension. Through proteomic profiling, Jujic and collaborators [71] revealed that plasma S1P was associated with increased systolic blood pressure, multiple cardiovascular, inflammation and metabolism biomarkers. Importantly, these findings were observed in a relatively young study cohort with very few cardiovascular incidents, thus, indicating that these alterations might be associated with the pathogenesis of CVDs rather than the end stage of the disease [71].

In line with this elegant study and in a translational approach, we identified S1P as a powerful biomarker associated with high blood pressure, since the increase in circulating S1P (alongside soluble NADPH oxidase 2-derived (NOX2-derived) peptide) was more pronounced in uncontrolled hypertensive patients and linearly correlated with each other in the entire hypertensive cohort [72]. The only clinical study available was conducted on 920 patients in Beijing between 2016 and 2018 with a mean follow-up of 2.3 years [73]. These hypertensive patients’ plasma was evaluated using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem spectrometry and the risk of MACE, including acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, stroke and CV death, was correlated with sphingolipid levels. The plasma levels of the 71 patients that experienced MACE showed a significant increase in three specific ceramides (d18:1/16:0, d18:1/22:0 and d18:1/24:0), all of which were highly significant in predicting MACE. This clinical trial highlights the possible use of sphingolipids as a biomarker for improving the identification of hypertensive patients at high risk of CVD [73].

5. Stroke

Through an in vivo experimental model of stroke, Kim and co-workers [74] demonstrated the critical role of S1PR2 in the induction of cerebrovascular permeability, neurovascular injury and intracerebral hemorrhage. In particular, pharmacological or genetic deficiency in S1PR2 resulted in a marked decrease in both infarct ratio and total cerebral oedema ratio and improved neurological scores after transient focal ischemia induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) [74]. Moreover, global alterations in sphingolipid metabolism were observed in the brain tissue of two spontaneously hypertensive models, the stroke-prone (SHRSP) and the stroke-resistant (SHRSR) rat strains [75].

The activity of the rate-limiting kinase in the generation of S1P, SphK1, has also been reported to be detrimental in ischemia-induced brain injury [76]. Pharmacological inhibition or siRNA-mediated knockdown of Sphk1 reduced infarct volumes and improved the neurological deficits after MCAO via the attenuation of pro-inflammatory mediators in the cortical penumbra [76]. Long-chain ceramides were markedly increased in mouse brain tissue after 1 h of MCAO [77]. In vivo experiments performed in mice revealed a dramatic increase in circulating sphingolipid levels 24 h after the injury in the stroke compared to sham animals [78]. In particular, the authors identified C42:1 and SM36:0 as the top-performing species, with an increase of up to 60-fold. These findings were further corroborated in a small cohort of patients with acute ischemic stroke, in which the two sphingolipid species identified in the animal model positively correlated with the severity of injury [78]. Recently, plasma ceramide levels were found to be significantly increased in patients with acute ischemic stroke with large artery occlusion and cerebral small-vessel disease [79,80,81]. Even more interestingly, higher levels of Cer (d18:1/18:0), Cer (d18:1/20:0) and Cer (d18:1/22:0) significantly correlated with poor functional outcomes 3 months after stroke [79]. A line of clinical research born towards the end of the 1980s has investigated the use of gangliosides in stroke. Gangliosides are compounds belonging to the general class of glycolipids, particularly abundant in the brain. They owe their name to the fact that they were isolated for the first time in the ganglia and are functionally qualified constituents of membrane receptor sites to which specific effectors bind, for example, neurotransmitters, hormones, bacterial toxins, etc., to evoke specific responses at the synapse level. Starting from 1984, with a double-blind clinical trial with monosialoganglioside (GM1) [82], various attempts have been made to identify possible beneficial effects from these molecules in stroke. Different dosages [83] and timings [84] have been investigated as well as effects at follow-up [85]. Although demonstrated to be safe [86], ganglioside GM1 did not show established clinical efficacy and was unfortunately set aside [87,88].

6. Vascular Dysfunction

Previous studies have shown that at physiological concentration, S1P induces vasculoprotective signaling by stimulating eNOS-derived NO production through engagement of S1P1 and S1P3 [89,90]. In contrast, higher S1P levels promote S1P3-mediated vascular barrier dysfunction [91]. These differences could be explained by the dynamic signaling model proposed by Kerage et al., showing that S1P signaling differentially regulates vascular tone at a dynamic range [92]. This notion is supported by numerous studies that have identified altered sphingolipid metabolism in blood vessels as an important trigger of vascular dysfunction [14,72,93], a key contributor to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disorders. Ex vivo studies showed impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilation of vessels after ceramide stimulation, an effect that was mediated by increased ROS production and reduced nitric oxide levels NO [94,95]. In their work, Li et al. [96] incubated human endothelial cells with exogenous cell-permeable C6 or C8 ceramide or with bacterial SMase, thus, demonstrating that while ceramides enhance endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) transcription on the one hand, this causes ROS production to evoke endothelial dysfunction and an impairment in NO-mediated vasorelaxation, on the other. This process appears to be mediated by different mechanisms, such as activation of the NAD(P)H oxidase family—the main enzyme responsible for ROS generation—[97], the interaction with the mitochondrial electron transport chain [98] and the uncoupling of eNOS [96]. This last phenomenon occurs in the presence of a reduced availability of a pivotal enzymatic cofactor required for the synthesis of NO (tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)) and is caused by an increased oxidation of BH4 itself by ROS [99]. In these conditions, eNOS, which is the primary enzyme responsible for NO generation in the vascular endothelium, contributes to ROS production in lieu of NO. The involvement of sphingolipids in this harmful process is confirmed by the finding that the ceramide-induced reduction of NO is rescued by the treatment with BH4 and by the evidence that the treatment with the eNOS inhibitor L-NG-Nitro arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), limited, in part, endothelial ROS generation [96]. In line with the impairment in NO signaling, further studies have shown that inhibition of ceramide synthesis or lysosomal acid SMase preserves eNOS-mediated signaling and vascular function in diet-induced obesity [13,14] and after TNF-α exposure [93], respectively. S1P also plays an important role in the modulation of vascular reactivity. Chronic S1P-infused wild-type C57BL/6J mice were shown to have increased vasoconstriction and endothelial dysfunction of mesenteric arteries [70], thus, suggesting S1P as an important marker of endothelial dysfunction. These findings were further supported by human observation in which elevation of S1P serum levels was positively correlated with impaired endothelial function as well as with increased vessels contractility [70].

7. Diabetes

Diabetes represents a global health issue, with an estimated 415 million people afflicted worldwide, more than 90% of whom had type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [100]. In order to reduce this high burden, one of the most effective ways could be the detection of novel biomarkers able to predict the onset of T2DM. Recent studies have demonstrated that sphingolipids, in particular ceramides, could contribute to insulin resistance by inhibiting the activation of protein kinase B (PKB), which leads to the blocking of the translocation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) and the consequent suppression of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis. Incubation of muscle cells with C2 ceramid stimulates an atypical member of PKC family, PKCζ, which phosphorylates the PKB’s PH domain on Thr34. In the absence of insulin, PKB is present in the cytosol in its inactive state where it forms a pre-activation complex with 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) [101]. After insulin stimulation, this complex translocates to the plasma membrane and hooks onto the membrane lipid phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) [102], where it is converted to the active phosphorylated form, p-PKB [101,103], and causes insulin-induced glucose uptake into cells by stimulating the translocation of GLUT4 to the cell surface [104]. The phosphorylation induced by C2 ceramide reduces the effects induced by insulin on the glucose metabolism through the inhibition of the binding of PIP3 to the PH domain. Mechanistically, in the presence of ceramide, the hormone is not only enabled to induce PKB’s activation, but loses its ability to dissociate the PKCζ/PKB complex [105]. Several studies have also demonstrated that C2 ceramide is able to completely inhibit insulin-stimulated PKB phosphorylation at both the T308 and S473 regulatory sites, causing a 90–95% loss in constitutive kinase activity [106]. The dephosphorylation induced by ceramide is entirely abolished by pretreatment with okadaic acid, a phosphatase inhibitor [107]. This discovery suggests that C2 ceramide is implied in the development of insulin resistance by keeping PKB in an inactive state as well as, probably, through the involvement of the principal phosphatase that dephosphorylates the serine/threonine protein kinase in adipocytes [108]: protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which is okadaic-acid-sensitive [107]; this hypothesis was confirmed by the suppression of the sphingolipid’s effects through the expression of a PP2A inhibitor: the SV40 small T antigen [103]. In the presence of C2 dihydroceramide, a biologically inactive ceramide analog, these effects were abolished [107]. Insulin resistance could also be caused by the blocking of the insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of a hormone receptor substrate IRS-1 induced by ceramides [109,110,111] and by the ceramide-stimulated phosphorylation of its inhibitory serine residue [112], resulting in a severe impairment in insulin signal transduction. Indeed, ceramides have been shown to be able to regulate mTORC1 activity [113] and to activate some kinases, such as c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and IκKβ [114], involved in inactivation due to the phosphorylation of serine 307 of IRS-1 [113,115,116]. Several studies have shown that SphK2, the enzyme predominantly responsible for catalyzing the conversion of dihydrosphingosine (dhSph) to dihydro-S1P (dhS1P), is involved in both core features of diabetes: pancreatic β-cell lipotoxicity and dysfunction [117], and insulin resistance and glucose intolerance [118]. It is known that excessive ectopic deposition of sphingolipids in the pancreas precedes organ failure, β-cell dysfunction and death [119] and the consequent reduced insulin production [120], a phenomenon known as gluco-lipotoxicity [121]. Indeed, due to their capacity to increase the activity of phosphatase PP2A, ceramides are able to catalyze, in the islet of Langerhans and pancreatic β-cell lines, the inactivation of the extracellular-signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), leading to a decrease in proinsulin gene transcription [122]. Moreover, ceramides inhibit the nuclear translocation of PDX-1 and Mafa, two important transcription factors for insulin-induced gene expression [119], and may block the glucose-induced expression of PASK (Per-Arnt-Sim domain-containing kinase), a serine/threonine protein kinase involved in the control of pancreatic islet hormone release and insulin sensitivity [123]. In addition, pancreatic sphingolipid accumulation leads to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [124], mitochondrial dysfunction [125] and NADPH oxidase activation and consequent ROS production [126], which, in turn, induce β-cell apoptosis [121], as well as through the stimulation of pro-apoptotic agents, such as caspase [127], serine/threonine protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) [114] and the SAPK/JNK signaling pathway [128]. At last, ceramides appear to play a role in both β-cell apoptosis [129] and insulin resistance [130] induced by proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) [131].

Multivariable analysis demonstrated that a small number of specific sphingolipid species were independent predictors of future cardiovascular events and deaths in individuals with T2DM [132]. In a population-based cohort study of approximately 2000 Chinese individuals, the authors identified a novel panel of sphingolipids positively associated with increased T2DM risk [133]. These findings are consistent with other previous studies, in which higher concentrations of distinct SM and ceramides have been correlated with incident T2DM [134,135,136]. In their work, Chen and collaborators [136] highlighted the involvement of sphingolipids in the onset of diabetes. They demonstrated that dihydrosphingosine (dhSph) and dihydro-S1P (dhS1P) could be candidates as potential biomarkers for the early diagnosis of T2DM. They showed that, in patients who developed diabetes, the levels of dhS1P and its ratio to dhSph were elevated 4.2 years before the disease was diagnosed [136]. Similarly, quantitative analysis of circulating sphingolipids in individuals from two prospective cohorts revealed a significant increase in specific long-chain fatty-acid-containing dihydroceramides in humans up to 9 years before T2DM onset [134].

A growing number of studies suggest that one atypical sphingolipid (deoxyceramide-Cer(m)) species, which is formed by abnormal SPT activity, accumulates in patients with metabolic syndrome or T2DM [137,138,139]. In detail, variants in the genes SPTLC1 or SPTLC2 induce a shift in the substrate preference of SPT from serine to alanine and glycine, thereby leading to the formation of the two atypical deoxy-sphingoid bases: 1-deoxy-sphinganine and 1-deoxymethyl-sphinganine, defined as 1-deoxysphingolipids (1-DSL) [140]. Both of these metabolites lack the C1 hydroxyl group of sphinganine and, therefore, cannot be converted to more complex sphingolipids or degraded [140]. Deoxysphingolipids have been shown to cause toxicity in various cell types, including neurons, myoblasts, β cells and retinal cells [141,142,143,144,145]. In vitro studies reported that 1-DSL significantly lowered the viability of C2C12 myoblasts in a concentration- and time-dependent manner and induced necrosis, apoptosis as well as cellular autophagy [145]. Additionally, 1-DSL significantly compromises the functionality of skeletal muscle cells, by impairing migration, differentiation and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. The authors suggested that increased levels of 1-DSL detected in T2DM patients may contribute to the pathophysiology of muscle dysfunction associated with this disease [145].

8. Obesity

Growing evidence indicates that ceramides can affect different metabolic pathways depending on the specific fatty acyl chain lengths, a process regulated by six ceramide synthases, namely (CerS1–CerS6), whose expression differs throughout the body [146]. In line with this discovery, the reduction in specific ceramide pools in a tissue-specific manner resulted in a significant improvement in metabolic phenotype in a mouse model of obesity [147].

Genetic mouse studies suggest that the specific sphingolipid C16:0 ceramide produced by CerS6 represents a critical player for the onset of insulin resistance. Using an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) approach in an obese diabetic ob/ob mouse model, CerS6 knockdown significantly reduced body-weight gain and whole-body fat and fed/fasted blood-glucose levels, accompanied by a 1% reduction in glycated hemoglobin [148]. Moreover, ASO-treated mice exhibited improved insulin sensitivity and oral glucose tolerance [148]. Accordingly, a critical role of CerS6-dependent C16:0 ceramide production emerged in the regulation of adipose tissue function in obesity conditions. CerS6 mRNA expression and C16:0 ceramide levels were found elevated in the white adipose tissue (WAT) of 439 obese subjects, and this increase was correlated with insulin resistance, body-fat content and hyperglycemia [149]. Accordingly, deficiency in CerS6 in mice reduced ceramide concentration and prevented high-fat-diet-mediated obesity and glucose intolerance [149]. Of note, these effects were also replicated in brown adipose tissue- and liver-specific CerS6 knockout mice [149]. A central role of CerS1-derived C18:0 ceramide was demonstrated in the development of obesity-associated insulin resistance. Skeletal muscle is considered a major tissue involved in the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Global or skeletal muscle-specific deletion of CerS1 resulted in reduced C18:0 ceramide content, improved insulin-stimulated suppression of hepatic glucose production and systemic glucose homeostasis in a Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21)-dependent manner [150,151]. In line with this, cell-specific deficiency in CerS5- and CerS6- derived C16:0 failed to prevent insulin resistance in obese mice [150]. Genome-wide association studies identified the SPT suppressor ORMDL3 as an obesity-related gene, and its expression in human subcutaneous WAT was inversely correlated with BMI [152]. Importantly, ORMDL3 is downregulated in the WAT of obese mice and humans, and its deletion resembles the metabolic phenotypes of obesity induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) [153]. In fact, Ormdl3 deficiency in mice raised WAT ceramide levels, body weight and insulin resistance, all prevented by an inhibition in ceramide production with the SPT inhibitor myriocin [153]. A diverse range of clinical trials have investigated the relationship between obesity and sphingolipids. Muscle sphingolipids during exercise training evaluated with VO2 max, in three different subgroups of patients (athletes, obese and DM type II), showed a significant direct relation to levels of muscle C18:0 ceramide and an inverse relation with insulin resistance [154,155]. In the same subgroups of patients, a study on intracellular localization thanks to muscle biopsy showed that C18:0 ceramide is inversely related to insulin sensitivity [156]. Interestingly, after exercise training, improvements in insulin sensitivity were associated with a significant improvement in BMI, adiposity and a reduction in C14:0, C16:0, C18:0 and C24:0 ceramide, in both obese and T2DM patients [157]. Patients with metabolic syndrome in treatment with pioglitazone for 6 months showed a significant reduction in C16:0, C18:0, C20:0, C22:0 and C24:1 as compared to placebo. However, correlation with insulin sensitivity was not homogeneously positive [158]. Studies on human subjects demonstrated high serum levels of SM species with distinct saturated acyl chains (C18:0, C20:0, C22:0 and C24:0) in the obese as compared to age-matched healthy subjects [159]. Notably, the authors found that these sphingolipids were closely associated with the parameters of obesity, insulin resistance, lipid metabolism and liver function, thus, their involvement in the development of metabolic syndrome and their use as novel biomarkers of metabolic syndrome [159]. Similarly, dihydroceramide species 18:0, 20:0, 22:0 and 24:1 as well as sphingomyelin species 31:1 and 41:1 were significantly correlated with waist circumferences, a clinical marker of central obesity [160].

Even though each had a different scope, these studies highlighted the relation between sphingolipids and obesity. Evidence and future clinical trials and larger-scale human metabolomics studies are still needed.

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Cardiovascular diseases represent a major burden for global health, reducing quality of life and increasing mortality. All the evidence summarized in this review sheds some light on the mechanisms by which altered sphingolipid metabolism is involved in the pathogenesis of CVDs, paving the way for the use of these sphingolipids as promising biomarkers to improve risk stratification for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. The overall outcomes from clinical studies are summarized in Table 1. Cumulatively, these studies suggest that monitoring the imbalance in sphingolipid levels in the circulation could offer relevant tools to better assess the progression and/or severity of metabolic, cardio- and cerebrovascular disease. Therefore, using multiple sphingolipids as biomarkers in combination with clinical parameters might be useful to guide interventions focused on the prevention of adverse cardiovascular risk factors that might improve patients’ survival. Moreover, in light of recent findings, sphingolipids hold great promise for improvements in treatment strategies. Some approaches may include the development of enzyme inhibitors, such as sphingosine kinases, sphingomyelinases or ceramidases, that catalyze ceramide catabolism or its conversion to the bioactive form of S1P. Despite the efficacy of common pharmacological treatments, a large percentage of patients remain non-responders to drug therapy. Therefore, targeting sphingolipid metabolism appears to be important for the development of future therapeutic agents or to increase current treatment effectiveness.

Table 1.

Summary of the main findings from the clinical studies discussed in the review.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D.P., A.C. and C.V.; Original draft preparation, P.D.P., C.I., A.C.A., P.I., M.R.R., E.V. and V.V.; Review and editing, E.S., M.C., A.C. and C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Ricerca Finalizzata of the Italian Ministry of Health—Young Researcher project (GR-2018-12366268) to AC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rosenfeldt, H.M.; Hobson, J.P.; Maceyka, M.; Olivera, A.; Nava, V.E.; Milstien, S.; Spiegel, S. EDG-1 links the PDGF receptor to Src and focal adhesion kinase activation leading to lamellipodia formation and cell migration. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 2649–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; He, Q.; Sharma, R.P. Sphingosine kinase activity confers resistance to apoptosis by fumonisin B1 in human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2004, 151, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venable, M.E.; Webb-Froehlich, L.M.; Sloan, E.F.; Thomley, J.E. Shift in sphingolipid metabolism leads to an accumulation of ceramide in senescence. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2006, 127, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitru, C.A.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Gulbins, E. Ceramide: A novel player in reactive oxygen species-induced signaling? Antioxid Redox Signal 2007, 9, 1535–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Becker, K.A.; Zhang, Y. Ceramide in redox signaling and cardiovascular diseases. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 26, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levade, T.; Auge, N.; Veldman, R.J.; Cuvillier, O.; Negre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R. Sphingolipid mediators in cardiovascular cell biology and pathology. Circ. Res. 2001, 89, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spijkers, L.J.; van den Akker, R.F.; Janssen, B.J.; Debets, J.J.; De Mey, J.G.; Stroes, E.S.; van den Born, B.J.; Wijesinghe, D.S.; Chalfant, C.E.; MacAleese, L.; et al. Hypertension is associated with marked alterations in sphingolipid biology: A potential role for ceramide. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen, R.; Ekroos, K.; Sysi-Aho, M.; Hilvo, M.; Vihervaara, T.; Kauhanen, D.; Suoniemi, M.; Hurme, R.; Marz, W.; Scharnagl, H.; et al. Plasma ceramides predict cardiovascular death in patients with stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes beyond LDL-cholesterol. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Walsh, M.T.; Hammad, S.M.; Hussain, M.M. Sphingolipids and Lipoproteins in Health and Metabolic Disorders. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, W.L.; Brozinick, J.T.; Wang, L.P.; Hawkins, E.D.; Sargent, K.M.; Liu, Y.; Narra, K.; Hoehn, K.L.; Knotts, T.A.; Siesky, A.; et al. Inhibition of ceramide synthesis ameliorates glucocorticoid-, saturated-fat-, and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2007, 5, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojjati, M.R.; Li, Z.; Zhou, H.; Tang, S.; Huan, C.; Ooi, E.; Lu, S.; Jiang, X.C. Effect of myriocin on plasma sphingolipid metabolism and atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 10284–10289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, R.; Akashi, H.; Drosatos, K.; Liao, X.; Jiang, H.; Kennel, P.J.; Brunjes, D.L.; Castillero, E.; Zhang, X.; Deng, L.Y.; et al. Increased de novo ceramide synthesis and accumulation in failing myocardium. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e82922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.J.; Holland, W.L.; Wilson, L.; Tanner, J.M.; Kearns, D.; Cahoon, J.M.; Pettey, D.; Losee, J.; Duncan, B.; Gale, D.; et al. Ceramide mediates vascular dysfunction in diet-induced obesity by PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation of the eNOS-Akt complex. Diabetes 2012, 61, 1848–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharath, L.P.; Ruan, T.; Li, Y.; Ravindran, A.; Wan, X.; Nhan, J.K.; Walker, M.L.; Deeter, L.; Goodrich, R.; Johnson, E.; et al. Ceramide-Initiated Protein Phosphatase 2A Activation Contributes to Arterial Dysfunction In Vivo. Diabetes 2015, 64, 3914–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaitre, R.N.; Yu, C.; Hoofnagle, A.; Hari, N.; Jensen, P.N.; Fretts, A.M.; Umans, J.G.; Howard, B.V.; Sitlani, C.M.; Siscovick, D.S.; et al. Circulating Sphingolipids, Insulin, HOMA-IR, and HOMA-B: The Strong Heart Family Study. Diabetes 2018, 67, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anroedh, S.; Hilvo, M.; Akkerhuis, K.M.; Kauhanen, D.; Koistinen, K.; Oemrawsingh, R.; Serruys, P.; van Geuns, R.J.; Boersma, E.; Laaksonen, R.; et al. Plasma concentrations of molecular lipid species predict long-term clinical outcome in coronary artery disease patients. J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilvo, M.; Vasile, V.C.; Donato, L.J.; Hurme, R.; Laaksonen, R. Ceramides and Ceramide Scores: Clinical Applications for Cardiometabolic Risk Stratification. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 570628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, K.J.; Elbasan, S.; Keul, P.; Elter-Schulz, M.; Bode, C.; Graler, M.H.; Brocker-Preuss, M.; Budde, T.; Erbel, R.; Heusch, G.; et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate levels in plasma and HDL are altered in coronary artery disease. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2010, 105, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, J.D.; Abel, E.D. Lipotoxicity contributes to endothelial dysfunction: A focus on the contribution from ceramide. Rev Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2013, 14, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, W.L.; Summers, S.A. Sphingolipids, insulin resistance, and metabolic disease: New insights from in vivo manipulation of sphingolipid metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 2006, 47, C7–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plutzky, J. Inflammatory pathways in atherosclerosis and acute coronary syndromes. Am. J. Cardiol. 2001, 88, 10K–15K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auge, N.; Negre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R.; Levade, T. Sphingomyelin metabolites in vascular cell signaling and atherogenesis. Prog. Lipid Res. 2000, 39, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laulederkind, S.J.; Bielawska, A.; Raghow, R.; Hannun, Y.A.; Ballou, L.R. Ceramide induces interleukin 6 gene expression in human fibroblasts. J. Exp. Med. 1995, 182, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Narazaki, M.; Kishimoto, T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a016295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, G.J.; Ridker, P.M. Novel clinical markers of vascular wall inflammation. Circ. Res. 2001, 89, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auge, N.; Escargueil-Blanc, I.; Lajoie-Mazenc, I.; Suc, I.; Andrieu-Abadie, N.; Pieraggi, M.T.; Chatelut, M.; Thiers, J.C.; Jaffrezou, J.P.; Laurent, G.; et al. Potential role for ceramide in mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells induced by oxidized low density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 12893–12900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornfeldt, K.E.; Graves, L.M.; Raines, E.W.; Igarashi, Y.; Wayman, G.; Yamamura, S.; Yatomi, Y.; Sidhu, J.S.; Krebs, E.G.; Hakomori, S.; et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate inhibits PDGF-induced chemotaxis of human arterial smooth muscle cells: Spatial and temporal modulation of PDGF chemotactic signal transduction. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 130, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, S.; Chapman, J.; Steele, L.; Pyne, N.J. Sphingomyelin-derived lipids differentially regulate the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (ERK-2) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signal cascades in airway smooth muscle. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996, 237, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, X.; Xing, S.; Bian, F.; Yao, W.; Bai, X.; Zheng, T.; Wu, G.; Jin, S. Endogenous ceramide contributes to the transcytosis of oxLDL across endothelial cells and promotes its subendothelial retention in vascular wall. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2014, 2014, 823071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemand, T.; Rouahi, M.; Swiader, A.; Grazide, M.H.; Geoffre, N.; Alayrac, P.; Recazens, E.; Coste, A.; Salvayre, R.; Negre-Salvayre, A.; et al. nSMase2 (Type 2-Neutral Sphingomyelinase) Deficiency or Inhibition by GW4869 Reduces Inflammation and Atherosclerosis in Apoe(-/-) Mice. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 1479–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatomi, Y.; Ohmori, T.; Rile, G.; Kazama, F.; Okamoto, H.; Sano, T.; Satoh, K.; Kume, S.; Tigyi, G.; Igarashi, Y.; et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate as a major bioactive lysophospholipid that is released from platelets and interacts with endothelial cells. Blood 2000, 96, 3431–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatomi, Y.; Ruan, F.; Hakomori, S.; Igarashi, Y. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: A platelet-activating sphingolipid released from agonist-stimulated human platelets. Blood 1995, 86, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeda, S.; Honda, O.; Shimeno, H.; Nagamatsu, A. Sphingomyelinase and cell-permeable ceramide analogs increase the release of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 from cultured endothelial cells. Thromb. Res. 1995, 80, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeda, S.; Tsunoda, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Shimeno, H. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced release of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 from human umbilical vein endothelial cells: Involvement of intracellular ceramide signaling event. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1448, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keul, P.; Peters, S.; von Wnuck Lipinski, K.; Schroder, N.H.; Nowak, M.K.; Duse, D.A.; Polzin, A.; Weske, S.; Graler, M.H.; Levkau, B. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P) Lyase Inhibition Aggravates Atherosclerosis and Induces Plaque Rupture in ApoE(-/-)Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressler, K.A.; Mathias, S.; Kolesnick, R.N. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha activates the sphingomyelin signal transduction pathway in a cell-free system. Science 1992, 255, 1715–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modur, V.; Zimmerman, G.A.; Prescott, S.M.; McIntyre, T.M. Endothelial cell inflammatory responses to tumor necrosis factor alpha. Ceramide-dependent and -independent mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 13094–13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEver, R.P.; Moore, K.L.; Cummings, R.D. Leukocyte trafficking mediated by selectin-carbohydrate interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 11025–11028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimovitz-Friedman, A.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Bayoumy, S.; Garzotto, M.; McLoughlin, M.; Gallily, R.; Edwards, C.K., 3rd; Schuchman, E.H.; Fuks, Z.; Kolesnick, R. Lipopolysaccharide induces disseminated endothelial apoptosis requiring ceramide generation. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 186, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escargueil-Blanc, I.; Andrieu-Abadie, N.; Caspar-Bauguil, S.; Brossmer, R.; Levade, T.; Negre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R. Apoptosis and activation of the sphingomyelin-ceramide pathway induced by oxidized low density lipoproteins are not causally related in ECV-304 endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 27389–27395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada-Shiba, M.; Kinoshita, M.; Kamido, H.; Shimokado, K. Oxidized low density lipoprotein induces apoptosis in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells by common and unique mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 9681–9687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holopainen, J.M.; Lehtonen, J.Y.; Kinnunen, P.K. Lipid microdomains in dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine-ceramide liposomes. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1997, 88, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holopainen, J.M.; Lemmich, J.; Richter, F.; Mouritsen, O.G.; Rapp, G.; Kinnunen, P.K. Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine/C16:0-ceramide binary liposomes studied by differential scanning calorimetry and wide- and small-angle x-ray scattering. Biophys. J. 2000, 78, 2459–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schissel, S.L.; Tweedie-Hardman, J.; Rapp, J.H.; Graham, G.; Williams, K.J.; Tabas, I. Rabbit aorta and human atherosclerotic lesions hydrolyze the sphingomyelin of retained low-density lipoprotein. Proposed role for arterial-wall sphingomyelinase in subendothelial retention and aggregation of atherogenic lipoproteins. J. Clin. Invest. 1996, 98, 1455–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.B.; Dey, S.; Shi, W.Y.; Thomas, K.; Hutchins, G.M. Accumulation of glycosphingolipids in human atherosclerotic plaque and unaffected aorta tissues. Glycobiology 1997, 7, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edsfeldt, A.; Duner, P.; Stahlman, M.; Mollet, I.G.; Asciutto, G.; Grufman, H.; Nitulescu, M.; Persson, A.F.; Fisher, R.M.; Melander, O.; et al. Sphingolipids Contribute to Human Atherosclerotic Plaque Inflammation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.C.; Paultre, F.; Pearson, T.A.; Reed, R.G.; Francis, C.K.; Lin, M.; Berglund, L.; Tall, A.R. Plasma sphingomyelin level as a risk factor for coronary artery disease. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000, 20, 2614–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ke, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Li, K.; Yu, B.; Sun, M. Large-scale Metabolomic Analysis Reveals Potential Biomarkers for Early Stage Coronary Atherosclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilvo, M.; Simolin, H.; Metso, J.; Ruuth, M.; Oorni, K.; Jauhiainen, M.; Laaksonen, R.; Baruch, A. PCSK9 inhibition alters the lipidome of plasma and lipoprotein fractions. Atherosclerosis 2018, 269, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croyal, M.; Kaabia, Z.; Leon, L.; Ramin-Mangata, S.; Baty, T.; Fall, F.; Billon-Crossouard, S.; Aguesse, A.; Hollstein, T.; Sullivan, D.R.; et al. Fenofibrate decreases plasma ceramide in type 2 diabetes patients: A novel marker of CVD? Diabetes Metab. 2018, 44, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poss, A.M.; Maschek, J.A.; Cox, J.E.; Hauner, B.J.; Hopkins, P.N.; Hunt, S.C.; Holland, W.L.; Summers, S.A.; Playdon, M.C. Machine learning reveals serum sphingolipids as cholesterol-independent biomarkers of coronary artery disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130, 1363–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Xie, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Ni, W.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Zeng, Y. Association between ceramides and coronary artery stenosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Bonapace, S.; Lunardi, G.; Canali, G.; Dugo, C.; Vinco, G.; Calabria, S.; Barbieri, E.; Laaksonen, R.; Bonnet, F.; et al. Associations between specific plasma ceramides and severity of coronary-artery stenosis assessed by coronary angiography. Diabetes Metab. 2020, 46, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilvo, M.; Meikle, P.J.; Pedersen, E.R.; Tell, G.S.; Dhar, I.; Brenner, H.; Schottker, B.; Laaperi, M.; Kauhanen, D.; Koistinen, K.M.; et al. Development and validation of a ceramide- and phospholipid-based cardiovascular risk estimation score for coronary artery disease patients. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.D.; Toledo, E.; Hruby, A.; Rosner, B.A.; Willett, W.C.; Sun, Q.; Razquin, C.; Zheng, Y.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Guasch-Ferre, M.; et al. Plasma Ceramides, Mediterranean Diet, and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in the PREDIMED Trial (Prevencion con Dieta Mediterranea). Circulation 2017, 135, 2028–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, J.W.; Donato, L.J.; Bryant, S.C.; Baudhuin, L.M.; Berger, P.B.; Jaffe, A.S. Plasma Ceramides. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 1933–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.R.; Xanthakis, V.; Duncan, M.S.; Gross, S.; Friedrich, N.; Volzke, H.; Felix, S.B.; Jiang, H.; Sidhu, R.; Nauck, M.; et al. Ceramide Remodeling and Risk of Cardiovascular Events and Mortality. J. Am. Heart Assoc 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Yu, J.; Shi, R.; Yan, L.; Yang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, G.; Bai, Y.; Schuchman, E.H.; et al. Elevation of ceramide and activation of secretory acid sphingomyelinase in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Coron Artery Dis. 2014, 25, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, V.C.; Meeusen, J.W.; Medina Inojosa, J.R.; Donato, L.J.; Scott, C.G.; Hyun, M.S.; Vinciguerra, M.; Rodeheffer, R.R.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Jaffe, A.S. Ceramide Scores Predict Cardiovascular Risk in the Community. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 1558–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paola, M.; Cocco, T.; Lorusso, M. Ceramide interaction with the respiratory chain of heart mitochondria. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 6660–6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeid, L.M.; Linardic, C.M.; Karolak, L.A.; Hannun, Y.A. Programmed cell death induced by ceramide. Science 1993, 259, 1769–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekhite, M.; Gonzalez-Delgado, A.; Hubner, S.; Haxhikadrija, P.; Kretzschmar, T.; Muller, T.; Wu, J.M.F.; Bekfani, T.; Franz, M.; Wartenberg, M.; et al. The role of ceramide accumulation in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes on mitochondrial oxidative stress and mitophagy. Free Radic Biol. Med. 2021, 167, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reforgiato, M.R.; Milano, G.; Fabrias, G.; Casas, J.; Gasco, P.; Paroni, R.; Samaja, M.; Ghidoni, R.; Caretti, A.; Signorelli, P. Inhibition of ceramide de novo synthesis as a postischemic strategy to reduce myocardial reperfusion injury. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2016, 111, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Carrillo, L.; Gimenez-Escamilla, I.; Martinez-Dolz, L.; Sanchez-Lazaro, I.J.; Portoles, M.; Rosello-Lleti, E.; Tarazon, E. Implication of Sphingolipid Metabolism Gene Dysregulation and Cardiac Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Accumulation in Heart Failure. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, R.N.; Jensen, P.N.; Hoofnagle, A.; McKnight, B.; Fretts, A.M.; King, I.B.; Siscovick, D.S.; Psaty, B.M.; Heckbert, S.R.; Mozaffarian, D.; et al. Plasma Ceramides and Sphingomyelins in Relation to Heart Failure Risk. Circ. Heart Fail 2019, 12, e005708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzanfar, M.H.; Liu, P.; Roth, G.A.; Ng, M.; Biryukov, S.; Marczak, L.; Alexander, L.; Estep, K.; Hassen Abate, K.; Akinyemiju, T.F.; et al. Global Burden of Hypertension and Systolic Blood Pressure of at Least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990–2015. JAMA 2017, 317, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, A.; Miro, F.; Jimenez-Altayo, F.; Jurado, A.; Vila, E.; Planas, A.M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signalling-a key player in the pathogenesis of Angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogi, A.; Callera, G.E.; Aranha, A.B.; Antunes, T.T.; Graham, D.; McBride, M.; Dominiczak, A.; Touyz, R.M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate-induced inflammation involves receptor tyrosine kinase transactivation in vascular cells: Upregulation in hypertension. Hypertension 2011, 57, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlinski, M.; Nosalski, R.; Szczepaniak, P.; Ludwig-Galezowska, A.H.; Mikolajczyk, T.; Filip, M.; Osmenda, G.; Wilk, G.; Nowak, M.; Wolkow, P.; et al. Vascular transcriptome profiling identifies Sphingosine kinase 1 as a modulator of angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jujic, A.; Matthes, F.; Vanherle, L.; Petzka, H.; Orho-Melander, M.; Nilsson, P.M.; Magnusson, M.; Meissner, A. Plasma S1P (Sphingosine-1-Phosphate) Links to Hypertension and Biomarkers of Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease: Findings From a Translational Investigation. Hypertension 2021, 78, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pietro, P.; Carrizzo, A.; Sommella, E.; Oliveti, M.; Iacoviello, L.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Acernese, F.; Damato, A.; De Lucia, M.; Merciai, F.; et al. Targeting the ASMase/S1P pathway protects from sortilin-evoked vascular damage in hypertension. J. Clin. Invest. 2022, 132, e146343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Li, F.; Tan, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, W.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. Plasma Ceramides and Cardiovascular Events in Hypertensive Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk. Am. J. Hypertens. 2021, 34, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, H.; Selim, M.; McCullough, L.D.; Kluk, M.J.; Sanchez, T. Critical role of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-2 in the disruption of cerebrovascular integrity in experimental stroke. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, G.; Cotugno, M.; Marracino, F.; Giova, S.; Capocci, L.; Forte, M.; Stanzione, R.; Bianchi, F.; Marchitti, S.; Di Pardo, A.; et al. Differential Expression of Sphingolipid Metabolizing Enzymes in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats: A Possible Substrate for Susceptibility to Brain and Kidney Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wei, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, H.; Jia, J.; Cheng, J. Sphingosine kinase 1 mediates neuroinflammation following cerebral ischemia. Exp. Neurol. 2015, 272, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, H.C.; Lee, T.H.; Chiang, C.S.; Yang, S.Y.; Kuo, C.H.; Tang, S.C. Sphingolipidomics Investigation of the Temporal Dynamics after Ischemic Brain Injury. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 3470–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, S.A.; Iavarone, A.T.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Won, S.J.; Swanson, R.A. Targeted Lipid Profiling Discovers Plasma Biomarkers of Acute Brain Injury. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Cheng, C.N.; Chao, H.C.; Lee, C.H.; Kuo, C.H.; Tang, S.C.; Jeng, J.S. Plasma ceramides are associated with outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients. J. Med. Assoc. 2022, 121, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Cheng, C.N.; Lee, C.W.; Kuo, C.H.; Tang, S.C.; Jeng, J.S. Investigating sphingolipids as biomarkers for the outcomes of acute ischemic stroke patients receiving endovascular treatment. J. Med. Assoc. 2022, 122, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Q.; Peng, Q.; Yu, Z.; Jin, H.; Zhang, J.; Sun, W.; Huang, Y. Plasma lipidomic analysis of sphingolipids in patients with large artery atherosclerosis cerebrovascular disease and cerebral small vessel disease. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, S.; Albizzati, M.G.; Sbacchi, M.; Frattola, L.; Massarotti, M. Double-blind evaluation of monosialoganglioside (GM1) therapy in stroke. J. Neurosci. Res. 1984, 12, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffbrand, B.I.; Bingley, P.J.; Oppenheimer, S.M.; Sheldon, C.D. Trial of ganglioside GM1 in acute stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1988, 51, 1213–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argentino, C.; Sacchetti, M.L.; Toni, D.; Savoini, G.; D’Arcangelo, E.; Erminio, F.; Federico, F.; Milone, F.F.; Gallai, V.; Gambi, D.; et al. GM1 ganglioside therapy in acute ischemic stroke. Italian Acute Stroke Study--Hemodilution + Drug. Stroke 1989, 20, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldi, C.; Masi, M.C.; Manetti, M.; Carabelli, E.; Martini, A. A pilot study with monosialoganglioside GM1 on acute cerebral ischemia. Acta Neurol. 1990, 12, 214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi, G.L.; Grigoletto, F.; Gent, M.; Roberts, R.S.; Walker, M.D.; Easton, J.D.; Carolei, A.; Dorsey, F.C.; Rocca, W.A.; Bruno, R.; et al. Early treatment of stroke with monosialoganglioside GM-1. Efficacy and safety results of the Early Stroke Trial. Stroke 1994, 25, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocca, W.A.; Dorsey, F.C.; Grigoletto, F.; Gent, M.; Roberts, R.S.; Walker, M.D.; Easton, J.D.; Bruno, R.; Carolei, A.; Sancesario, G.; et al. Design and baseline results of the monosialoganglioside early stroke trial. The EST Study Group. Stroke 1992, 23, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The SASS Trial. Ganglioside GM1 in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 1994, 25, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalupo, A.; Zhang, Y.; Kothiya, M.; Galvani, S.; Obinata, H.; Bucci, M.; Giordano, F.J.; Jiang, X.C.; Hla, T.; Di Lorenzo, A. Nogo-B regulates endothelial sphingolipid homeostasis to control vascular function and blood pressure. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1028–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theilmeier, G.; Schmidt, C.; Herrmann, J.; Keul, P.; Schafers, M.; Herrgott, I.; Mersmann, J.; Larmann, J.; Hermann, S.; Stypmann, J.; et al. High-density lipoproteins and their constituent, sphingosine-1-phosphate, directly protect the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo via the S1P3 lysophospholipid receptor. Circulation 2006, 114, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarova, Y.A.; Mehta, D.; Malik, A.B. Dual regulation of endothelial junctional permeability. Sci. STKE 2007, 2007, re8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerage, D.; Brindley, D.N.; Hemmings, D.G. Review: Novel insights into the regulation of vascular tone by sphingosine 1-phosphate. Placenta 2014, 35, S86–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Chen, J.; Pang, L.; Chen, C.; Ye, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, B.; et al. The Acid Sphingomyelinase Inhibitor Amitriptyline Ameliorates TNF-alpha-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2022. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.X.; Zou, A.P.; Li, P.L. Ceramide reduces endothelium-dependent vasodilation by increasing superoxide production in small bovine coronary arteries. Circ. Res. 2001, 88, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Altura, B.T.; Altura, B.M. Sphingomyelinase and ceramide analogs induce contraction and rises in [Ca(2+)](i) in canine cerebral vascular muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000, 278, H1421–H1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Junk, P.; Huwiler, A.; Burkhardt, C.; Wallerath, T.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Forstermann, U. Dual effect of ceramide on human endothelial cells: Induction of oxidative stress and transcriptional upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation 2002, 106, 2250–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, A.K.; Han, H.; Snowden, A.; Chatterjee, S. Redox-regulated signaling by lactosylceramide in the proliferation of human aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 15642–15649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollnau, H.; Wendt, M.; Szocs, K.; Lassegue, B.; Schulz, E.; Oelze, M.; Li, H.; Bodenschatz, M.; August, M.; Kleschyov, A.L.; et al. Effects of angiotensin II infusion on the expression and function of NAD(P)H oxidase and components of nitric oxide/cGMP signaling. Circ Res 2002, 90, E58–E65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauersachs, J.; Schafer, A. Tetrahydrobiopterin and eNOS dimer/monomer ratio—A clue to eNOS uncoupling in diabetes? Cardiovasc. Res. 2005, 65, 768–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2017, 389, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.W.; Coster, A.C.F. From insulin to Akt: Time delays and dominant processes. J. Biol. 2020, 507, 110454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, A.F.; Fazakerley, D.J.; James, D.E. Mapping insulin/GLUT4 circuitry. Traffic 2011, 12, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavez, J.A.; Knotts, T.A.; Wang, L.P.; Li, G.; Dobrowsky, R.T.; Florant, G.L.; Summers, S.A. A role for ceramide, but not diacylglycerol, in the antagonism of insulin signal transduction by saturated fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 10297–10303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garofalo, R.S.; Orena, S.J.; Rafidi, K.; Torchia, A.J.; Stock, J.L.; Hildebrandt, A.L.; Coskran, T.; Black, S.C.; Brees, D.J.; Wicks, J.R.; et al. Severe diabetes, age-dependent loss of adipose tissue, and mild growth deficiency in mice lacking Akt2/PKB beta. J. Clin. Invest. 2003, 112, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.J.; Hajduch, E.; Kular, G.; Hundal, H.S. Ceramide disables 3-phosphoinositide binding to the pleckstrin homology domain of protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt by a PKCzeta-dependent mechanism. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 23, 7794–7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinda, M.J.; Vlahos, C.J.; Lai, M.T. Ceramide induces the dephosphorylation and inhibition of constitutively activated Akt in PTEN negative U87 mg cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 280, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruel, T.; Hernandez, R.; Lorenzo, M. Ceramide mediates insulin resistance by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in brown adipocytes by maintaining Akt in an inactive dephosphorylated state. Diabetes 2001, 50, 2563–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resjo, S.; Goransson, O.; Harndahl, L.; Zolnierowicz, S.; Manganiello, V.; Degerman, E. Protein phosphatase 2A is the main phosphatase involved in the regulation of protein kinase B in rat adipocytes. Cell Signal 2002, 14, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, K.; Hemi, R.; LeRoith, D.; Karasik, A.; Elhanany, E.; Kanety, H.; Zick, Y. A molecular basis for insulin resistance. Elevated serine/threonine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and IRS-2 inhibits their binding to the juxtamembrane region of the insulin receptor and impairs their ability to undergo insulin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 29911–29918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peraldi, P.; Hotamisligil, G.S.; Buurman, W.A.; White, M.F.; Spiegelman, B.M. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibits insulin signaling through stimulation of the p55 TNF receptor and activation of sphingomyelinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 13018–13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanety, H.; Hemi, R.; Papa, M.Z.; Karasik, A. Sphingomyelinase and ceramide suppress insulin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 9895–9897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, S.A. Ceramides in insulin resistance and lipotoxicity. Prog. Lipid Res. 2006, 45, 42–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denhez, B.; Rousseau, M.; Spino, C.; Dancosst, D.A.; Dumas, M.E.; Guay, A.; Lizotte, F.; Geraldes, P. Saturated fatty acids induce insulin resistance in podocytes through inhibition of IRS1 via activation of both IKKbeta and mTORC1. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvolo, P.P. Intracellular signal transduction pathways activated by ceramide and its metabolites. Pharm. Res. 2003, 47, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gual, P.; Le Marchand-Brustel, Y.; Tanti, J.F. Positive and negative regulation of insulin signaling through IRS-1 phosphorylation. Biochimie 2005, 87, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, V.; Werner, E.D.; Giraud, J.; Lee, Y.H.; Shoelson, S.E.; White, M.F. Phosphorylation of Ser307 in insulin receptor substrate-1 blocks interactions with the insulin receptor and inhibits insulin action. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, N.; Yan, S.; Rong, K.; Lan, T.; Xia, P. Sphingosine kinase 2 promotes lipotoxicity in pancreatic beta-cells and the progression of diabetes. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 3636–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, G.; Huang, Y.; Ng, M.L.; Wang, W.; Lan, T.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, R.; Yan, S.; et al. Regulation of hepatic insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis by sphingosine kinase 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 24434–24442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitout, V.; Robertson, R.P. Glucolipotoxicity: Fuel excess and beta-cell dysfunction. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Herpen, N.A.; Schrauwen-Hinderling, V.B. Lipid accumulation in non-adipose tissue and lipotoxicity. Physiol. Behav. 2008, 94, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veret, J.; Bellini, L.; Giussani, P.; Ng, C.; Magnan, C.; Le Stunff, H. Roles of Sphingolipid Metabolism in Pancreatic beta Cell Dysfunction Induced by Lipotoxicity. J. Clin. Med. 2014, 3, 646–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Qian, Y.; Xi, X.; Hu, X.; Zhu, J.; Han, X. Blockage of ceramide metabolism exacerbates palmitate inhibition of pro-insulin gene expression in pancreatic beta-cells. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2010, 338, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontes, G.; Semache, M.; Hagman, D.K.; Tremblay, C.; Shah, R.; Rhodes, C.J.; Rutter, J.; Poitout, V. Involvement of Per-Arnt-Sim Kinase and extracellular-regulated kinases-1/2 in palmitate inhibition of insulin gene expression in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2048–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boslem, E.; Weir, J.M.; MacIntosh, G.; Sue, N.; Cantley, J.; Meikle, P.J.; Biden, T.J. Alteration of endoplasmic reticulum lipid rafts contributes to lipotoxicity in pancreatic beta-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 26569–26582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veluthakal, R.; Palanivel, R.; Zhao, Y.; McDonald, P.; Gruber, S.; Kowluru, A. Ceramide induces mitochondrial abnormalities in insulin-secreting INS-1 cells: Potential mechanisms underlying ceramide-mediated metabolic dysfunction of the beta cell. Apoptosis 2005, 10, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, I.; Szulc, Z.M.; Ogretmen, B.; Kowluru, A. L- threo -C6-pyridinium-ceramide bromide, a novel cationic ceramide, induces NADPH oxidase activation, mitochondrial dysfunction and loss in cell viability in INS 832/13 beta-cells. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 30, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galadari, S.; Rahman, A.; Pallichankandy, S.; Galadari, A.; Thayyullathil, F. Role of ceramide in diabetes mellitus: Evidence and mechanisms. Lipids Health Dis. 2013, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheij, M.; Bose, R.; Lin, X.H.; Yao, B.; Jarvis, W.D.; Grant, S.; Birrer, M.J.; Szabo, E.; Zon, L.I.; Kyriakis, J.M.; et al. Requirement for ceramide-initiated SAPK/JNK signalling in stress-induced apoptosis. Nature 1996, 380, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Ullrich, S.; Gulbins, E. Ceramide formation as a target in beta-cell survival and function. Expert Opin. Targets 2011, 15, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, N.; Grambergs, R.; Mondal, K.; Basu, S.K.; Tahia, F.; Dagogo-Jack, S. Role of ceramides in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus and its complications. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2021, 35, 107734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnop, M.; Welsh, N.; Jonas, J.C.; Jorns, A.; Lenzen, S.; Eizirik, D.L. Mechanisms of pancreatic beta-cell death in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: Many differences, few similarities. Diabetes 2005, 54 (Suppl. 2), S97–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehry, Z.H.; Mundra, P.A.; Barlow, C.K.; Mellett, N.A.; Wong, G.; McConville, M.J.; Simes, J.; Tonkin, A.M.; Sullivan, D.R.; Barnes, E.H.; et al. Plasma Lipidomic Profiles Improve on Traditional Risk Factors for the Prediction of Cardiovascular Events in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 2016, 134, 1637–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, H.; Sun, L.; Wu, Q.; Zong, G.; Qi, Q.; Li, H.; Zheng, H.; Zeng, R.; Liang, L.; Lin, X. Associations among circulating sphingolipids, beta-cell function, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes: A population-based cohort study in China. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigger, L.; Cruciani-Guglielmacci, C.; Nicolas, A.; Denom, J.; Fernandez, N.; Fumeron, F.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Ktorza, A.; Kramer, W.; Schulte, A.; et al. Plasma Dihydroceramides Are Diabetes Susceptibility Biomarker Candidates in Mice and Humans. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 2269–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, W.S.; Torta, F.; Ji, S.; Choi, H.; Begum, H.; Sim, X.; Khoo, C.M.; Khoo, E.Y.H.; Ong, W.Y.; Van Dam, R.M.; et al. Large-scale lipidomics identifies associations between plasma sphingolipids and T2DM incidence. JCI Insight 2019, 5, e126925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, W.; Xia, M.F.; Lu, Y.L.; Bian, H.; Yu, C.; Li, X.Y.; Vadas, M.A.; Gao, X.; Lin, H.D.; et al. Identification of circulating sphingosine kinase-related metabolites for prediction of type 2 diabetes. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridman, V.; Zarini, S.; Sillau, S.; Harrison, K.; Bergman, B.C.; Feldman, E.L.; Reusch, J.E.B.; Callaghan, B.C. Altered plasma serine and 1-deoxydihydroceramide profiles are associated with diabetic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes and obesity. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2021, 35, 107852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwinyi, J.; Bostrom, A.; Fehrer, I.; Othman, A.; Waeber, G.; Marti-Soler, H.; Vollenweider, P.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Schioth, H.B.; von Eckardstein, A.; et al. Plasma 1-deoxysphingolipids are early predictors of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; Saely, C.H.; Muendlein, A.; Vonbank, A.; Drexel, H.; von Eckardstein, A.; Hornemann, T. Plasma 1-deoxysphingolipids are predictive biomarkers for type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2015, 3, e000073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penno, A.; Reilly, M.M.; Houlden, H.; Laura, M.; Rentsch, K.; Niederkofler, V.; Stoeckli, E.T.; Nicholson, G.; Eichler, F.; Brown, R.H., Jr.; et al. Hereditary sensory neuropathy type 1 is caused by the accumulation of two neurotoxic sphingolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 11178–11187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantner, M.L.; Eade, K.; Wallace, M.; Handzlik, M.K.; Fallon, R.; Trombley, J.; Bonelli, R.; Giles, S.; Harkins-Perry, S.; Heeren, T.F.C.; et al. Serine and Lipid Metabolism in Macular Disease and Peripheral Neuropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guntert, T.; Hanggi, P.; Othman, A.; Suriyanarayanan, S.; Sonda, S.; Zuellig, R.A.; Hornemann, T.; Ogunshola, O.O. 1-Deoxysphingolipid-induced neurotoxicity involves N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor signaling. Neuropharmacology 2016, 110, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.R.; Kugathasan, U.; Abramov, A.Y.; Clark, A.J.; Bennett, D.L.H.; Reilly, M.M.; Greensmith, L.; Kalmar, B. Hereditary sensory neuropathy type 1-associated deoxysphingolipids cause neurotoxicity, acute calcium handling abnormalities and mitochondrial dysfunction in vitro. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 117, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuellig, R.A.; Hornemann, T.; Othman, A.; Hehl, A.B.; Bode, H.; Guntert, T.; Ogunshola, O.O.; Saponara, E.; Grabliauskaite, K.; Jang, J.H.; et al. Deoxysphingolipids, novel biomarkers for type 2 diabetes, are cytotoxic for insulin-producing cells. Diabetes 2014, 63, 1326–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, D.; Myers, S.; McGowan, C.; Henstridge, D.; Eri, R.; Sonda, S.; Caruso, V. 1-Deoxysphingolipids, Early Predictors of Type 2 Diabetes, Compromise the Functionality of Skeletal Myoblasts. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 772925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmidt, P.; Bruning, J.C. Contribution of specific ceramides to obesity-associated metabolic diseases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin-Nolan, S.M.; Bruning, J.C. The role of ceramides in metabolic disorders: When size and localization matters. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raichur, S.; Brunner, B.; Bielohuby, M.; Hansen, G.; Pfenninger, A.; Wang, B.; Bruning, J.C.; Larsen, P.J.; Tennagels, N. The role of C16:0 ceramide in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes: CerS6 inhibition as a novel therapeutic approach. Mol. Metab. 2019, 21, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, S.M.; Nicholls, H.T.; Willmes, D.M.; Mourier, A.; Brodesser, S.; Wunderlich, C.M.; Mauer, J.; Xu, E.; Hammerschmidt, P.; Bronneke, H.S.; et al. Obesity-induced CerS6-dependent C16:0 ceramide production promotes weight gain and glucose intolerance. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin-Nolan, S.M.; Hammerschmidt, P.; Chen, W.; Jais, A.; Timper, K.; Awazawa, M.; Brodesser, S.; Bruning, J.C. CerS1-Derived C18:0 Ceramide in Skeletal Muscle Promotes Obesity-Induced Insulin Resistance. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 1–10e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachnio-Zabielska, A.U.; Roszczyc-Owsiejczuk, K.; Imierska, M.; Pogodzinska, K.; Rogalski, P.; Daniluk, J.; Zabielski, P. CerS1 but Not CerS5 Gene Silencing, Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Glucose Uptake in Skeletal Muscle. Cells 2022, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.Z.; Garske, K.M.; Alvarez, M.; Bhagat, Y.V.; Boocock, J.; Nikkola, E.; Miao, Z.; Raulerson, C.K.; Cantor, R.M.; Civelek, M.; et al. Integration of human adipocyte chromosomal interactions with adipose gene expression prioritizes obesity-related genes from GWAS. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Zan, W.; Qin, L.; Han, S.; Ye, L.; Wang, M.; Jiang, B.; Fang, P.; Liu, Q.; Shao, C.; et al. Ablation of ORMDL3 impairs adipose tissue thermogenesis and insulin sensitivity by increasing ceramide generation. Mol. Metab. 2022, 56, 101423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, B.C.; Brozinick, J.T.; Strauss, A.; Bacon, S.; Kerege, A.; Bui, H.H.; Sanders, P.; Siddall, P.; Wei, T.; Thomas, M.K.; et al. Muscle sphingolipids during rest and exercise: A C18:0 signature for insulin resistance in humans. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]