1. Introduction

Nuclear reaction models and simulation codes, grounded in nuclear physics principles, are used to calculate and analyze reactions when experimental data are limited or unavailable. Theoretical predictions for nuclear reaction models are crucial for generating reliable reaction cross-section data [

1]. Code COMPLET is an invaluable tool in educational contexts when direct experimentation is not possible, allowing students and researchers to investigate nuclear physics concepts. COMPLET is the nuclear reaction code developed to generate theoretical data on reaction mechanisms and cross-sections [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The computational algorithms used in code COMPLET can efficiently calculate complex reactions and interactions, making it a powerful tool for researchers in the field. The code advances detailed modeling that helps accurately predict reaction rates, energy patterns, and directions of particles released. It incorporates modern theoretical frameworks and experimental data to enhance its predictive power, making it a valuable tool for researchers in nuclear physics and related fields. This study focuses on alpha-induced reactions on cobalt-59, aiming to reproduce excitation functions and compare theoretical outputs with experimental data from EXFOR [

7,

8,

9]. The COMPLET code, based on the exciton model, was selected for its adaptability and reliability in predicting pre-equilibrium contributions. Despite previous uses of COMPLET, no systematic study has explored its performance across multiple alpha-induced cobalt reactions at energies up to 120 MeV. This gap motivates the present work, which aims to systematically compare COMPLET code predictions with existing experimental data across the full 10–120 MeV range, refine the model inputs, and assess the reliability and limitations of the COMPLET framework for alpha-induced reactions on cobalt.

2. Results and Discussion

The results of this study were gathered using the COMPLET code to explore how alpha particles interact with cobalt-59 targets in nuclear reactions. The data were analyzed through tables and graphs, which included projectile energy (E

α), theoretical cross-sections, and experimental values. Multiple parameters were used to establish theoretical predictions of excitation functions and evaluate their effects on reaction cross-sections. One key factor is the initial exciton number, which is essential for achieving accurate calculated values. The level density parameter also plays a crucial role in the statistical calculations used in nuclear reaction models. The COMPLET code calculated theoretical cross-sections using fixed input parameters: an initial exciton number (n

0 = 4) and level density parameter a = ACN/10. Here, the initial exciton numbers and the level density parameter (a) [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] have been adjusted to match the experimental data. The level density parameter a is determined using the formula a = ACN/K, where ACN is the mass number of the compound nucleus, and K is an adjustable constant selected and optimized to achieve the best agreement with the experimental data [

13,

14,

15]. The K-value was adjusted from 8 to 10, and the level density parameter that produced the best agreement with the experimental data was used for each reaction channel. The specific value of the level density parameter was selected based on the degree of agreement between calculated and experimental excitation functions.

This study compared theoretical computations generated by the COMPLET code with experimental data obtained from various authors through the EXFOR library [

16,

17,

18,

19]. The current study can be divided into two categories: one involving alpha particles alongside nucleons in the exit channels, and another that includes only nucleons in the exit channels. Several authors [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] explain pre-equilibrium processes on exciton models. They calculate particle emission rates by applying reciprocity to the ejectiles under consideration, rather than the entire system. This approach works well when only nucleons are considered, as their presence within nuclei is generally accepted, and there is solid theoretical guidance regarding their behavior. However, when it comes to clusters, there is a lack of information about their pre-formation and behavior within the nuclei based on a priori knowledge. The predictions made by the COMPLET code exhibit different levels of consistency when compared to the experimental data.

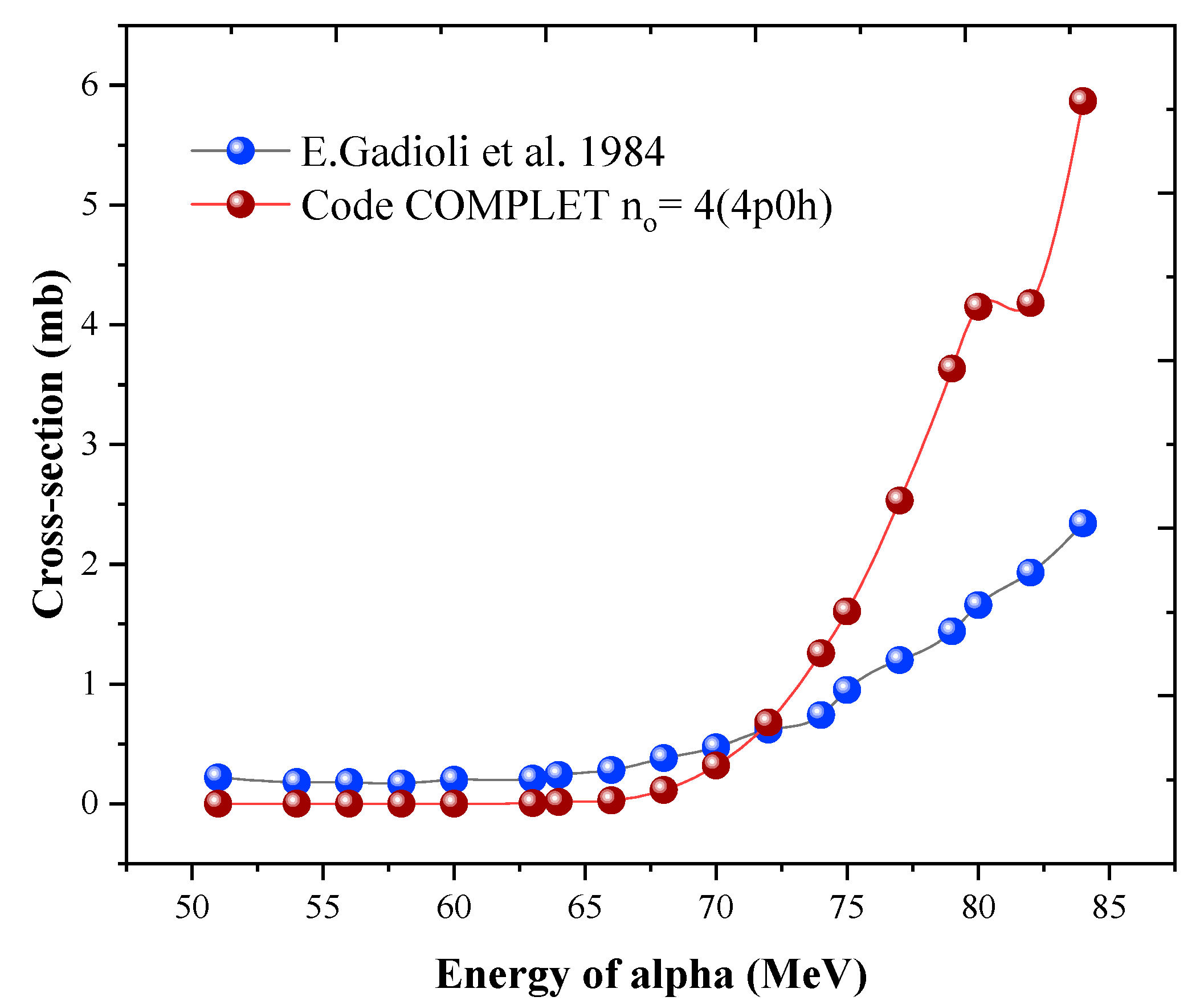

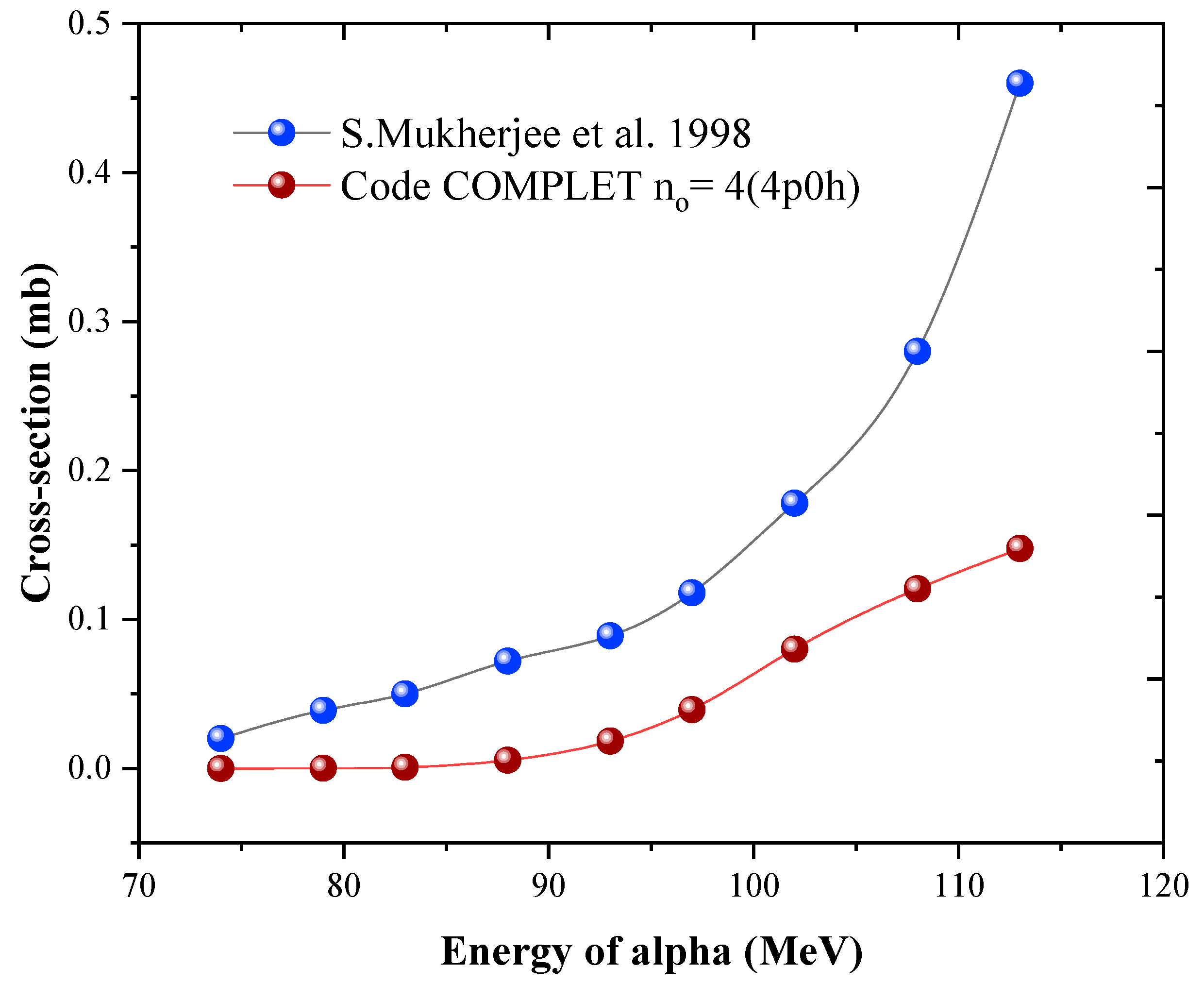

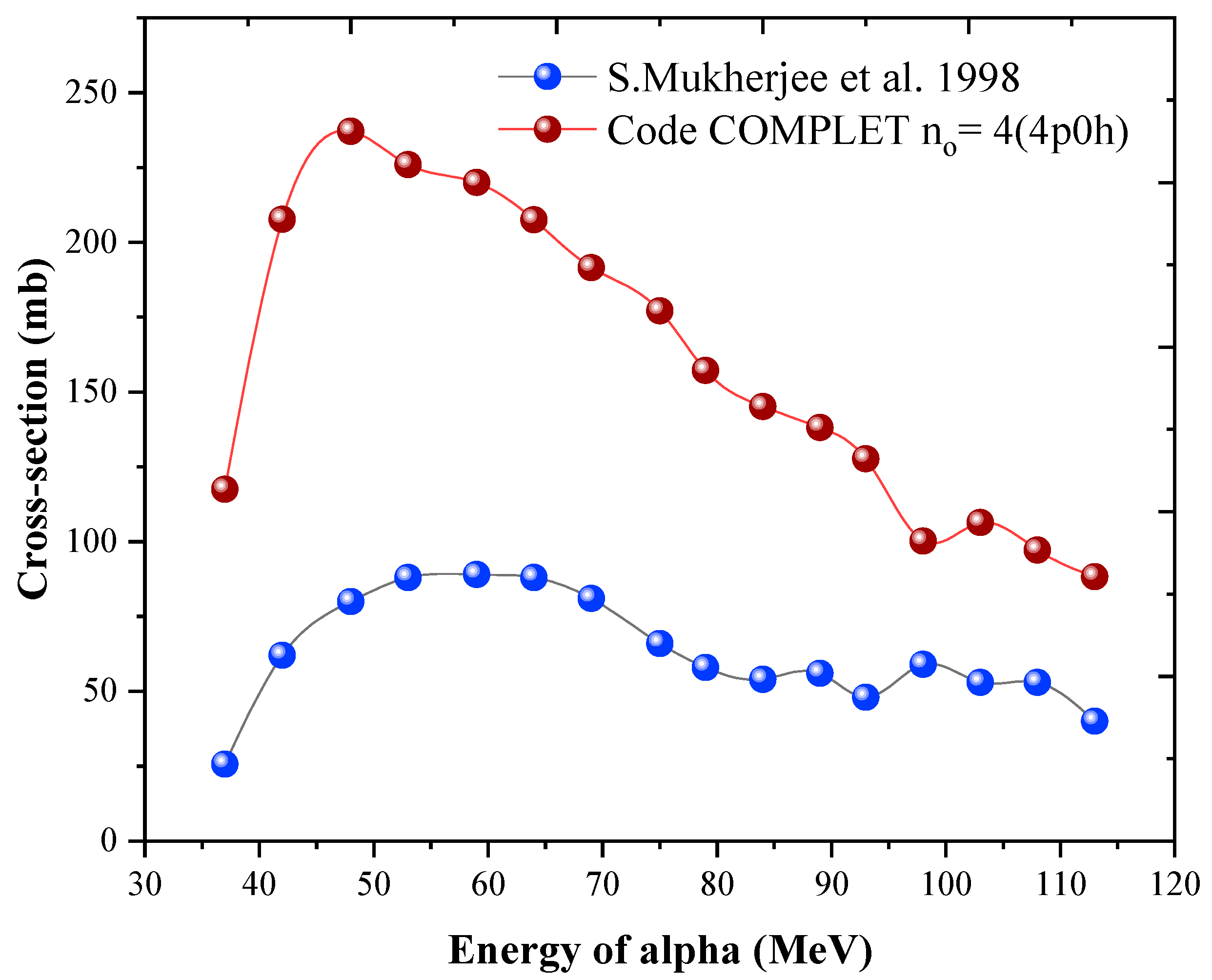

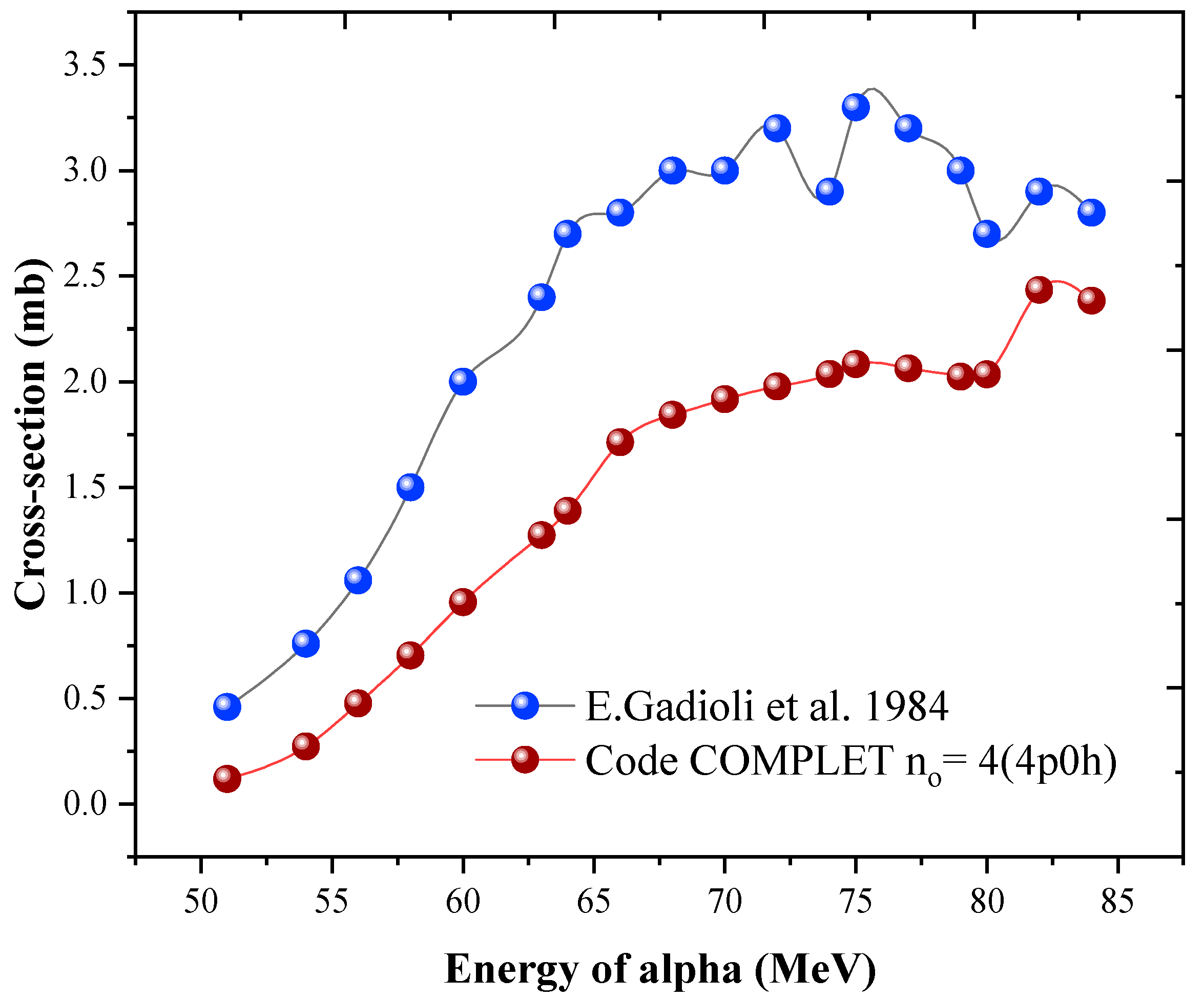

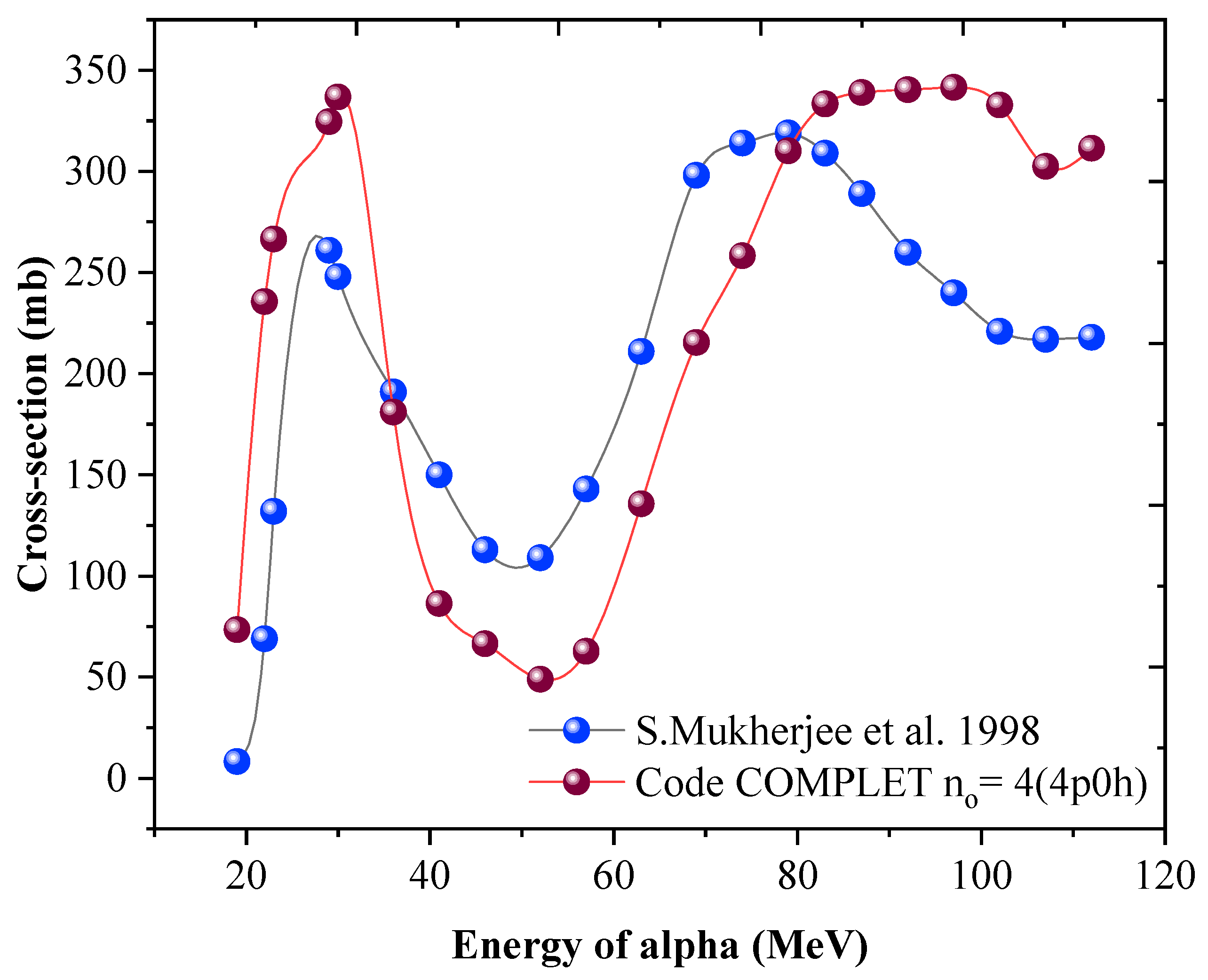

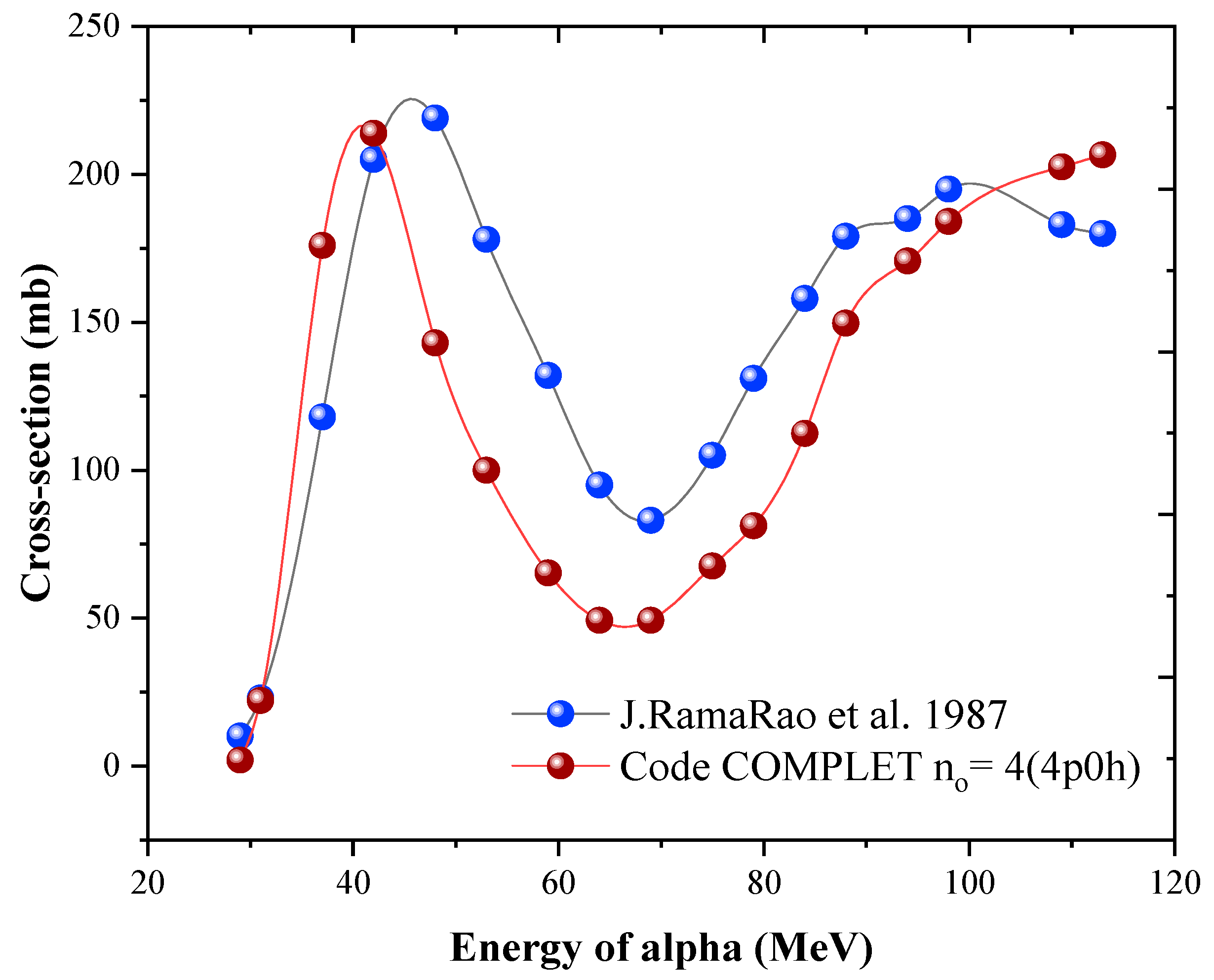

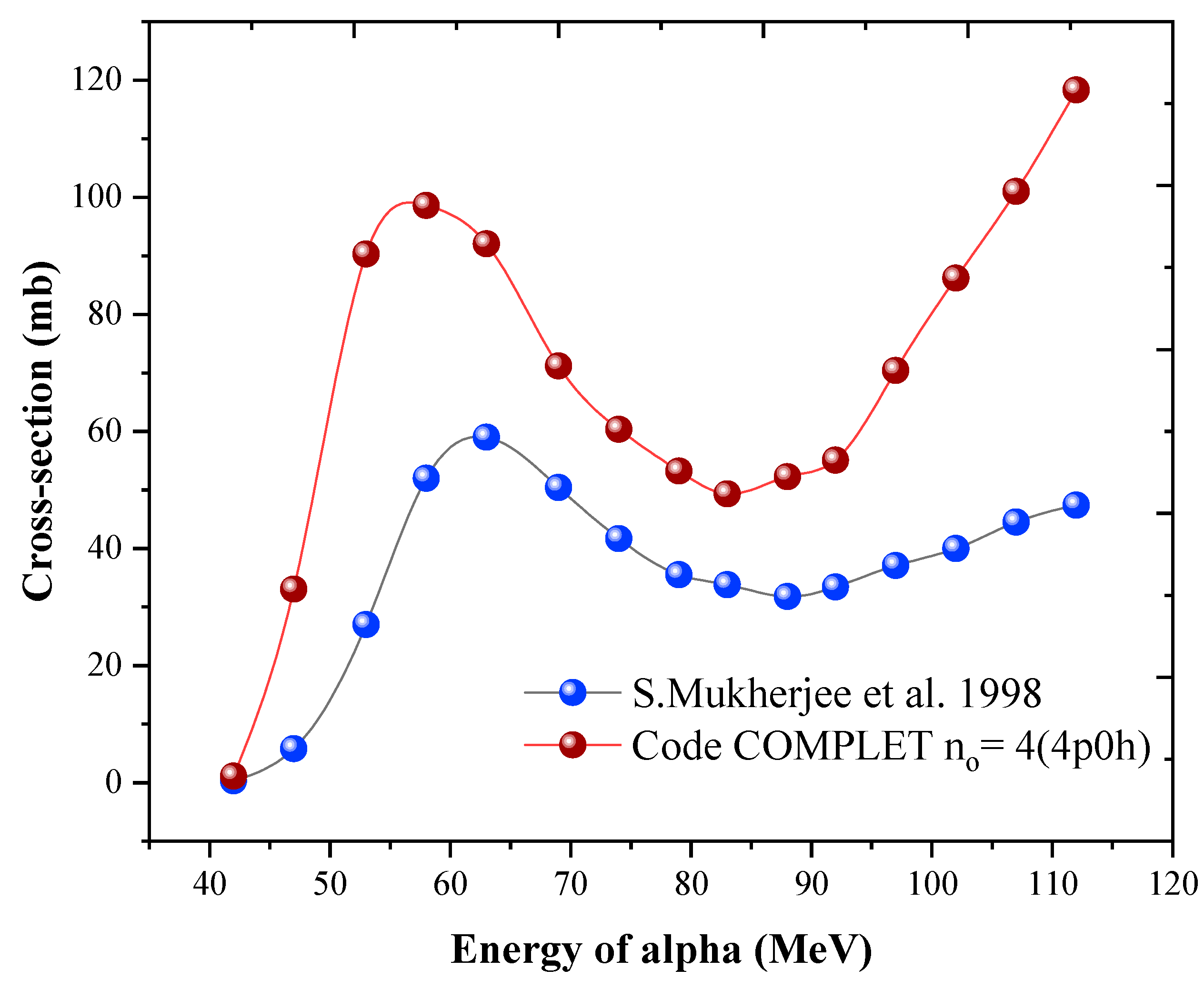

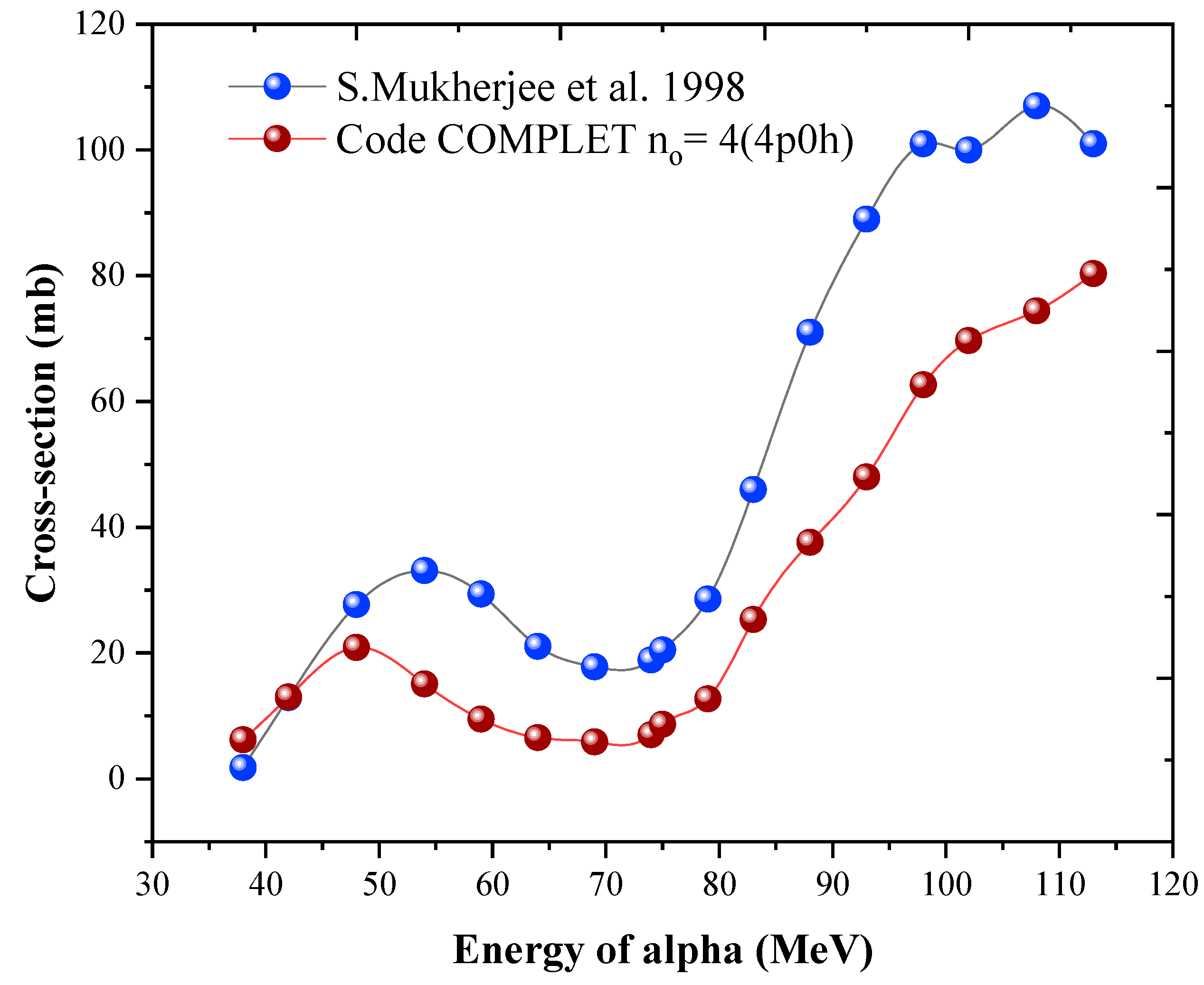

The first group includes the multiparticle emissions such us

59Co(α, p5n),

59Co(α, p6n),

59Co(α, 2pn), and

59Co(α, 3pn), these reactions are shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. It is observed that in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, while there is a good agreement between the experimental values and the COMPLET code predictions, there are discrepancies observed beyond 70 MeV. These differences are observed by a factor of 5 in

Figure 3. The reaction

59Co(α, 3pn) in

Figure 4, has extremely low cross-section values both in experimental and theoretical predications. This reaction yield is suppressed by the emission of 3 protons hindered by coulomb barrier. Overall, in all these

59Co(α, xynp) type of reactions, the code COMPLET predicts fairly good results up to 70 MeV.

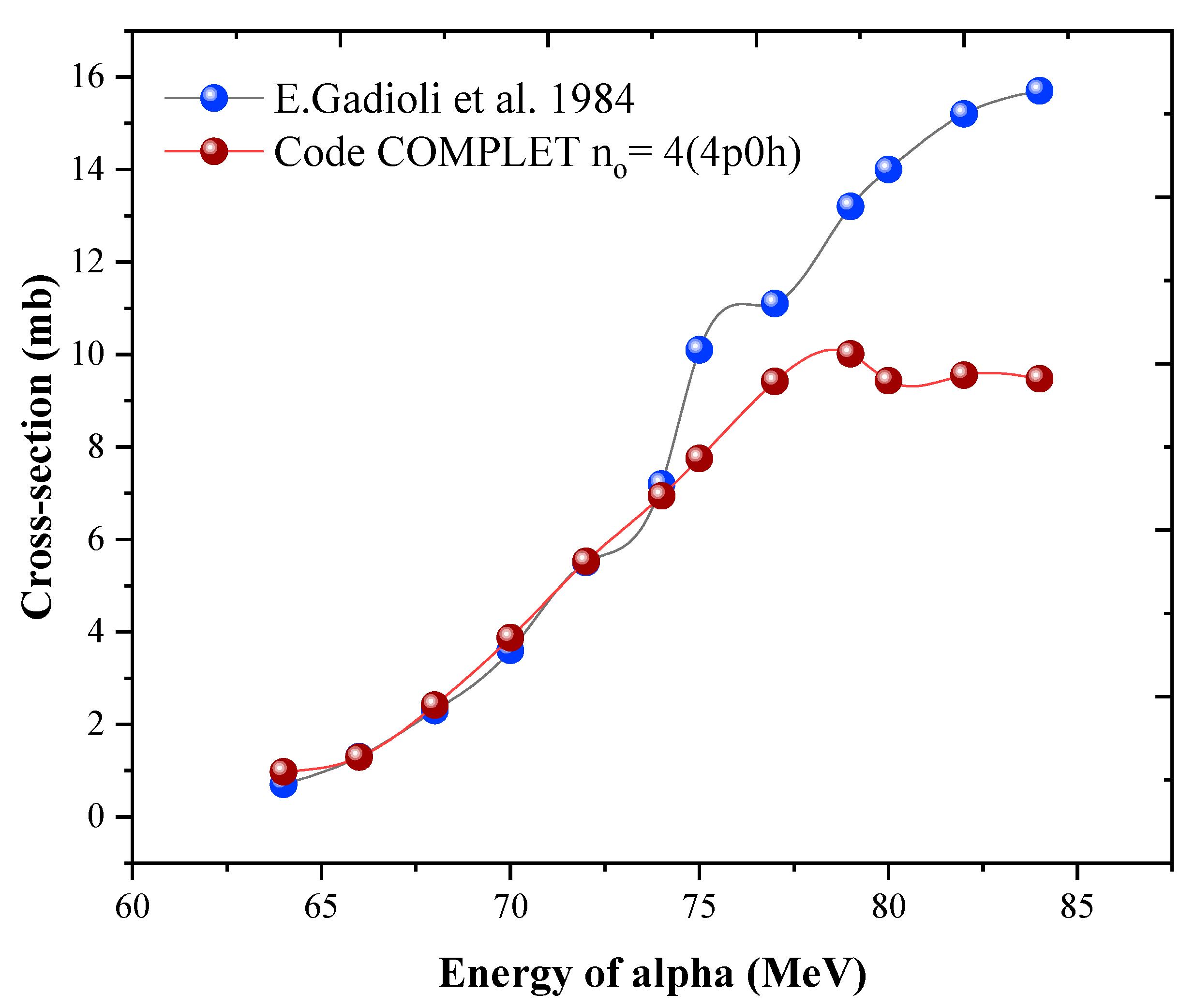

The second group includes reactions such as

59Co (α, αn), (α, α2n), (α, α3n), (α, 2αn), and (α, 2α3n). For these reactions, the shapes of the excitation functions are reasonably well-reproduced by the COMPLET code as shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. While the theoretical magnitudes generally fall below the experimental values by about a factor of two, one exception is the

59Co(α, 2α3n)

52Mn reaction as observed in

Figure 9, where a notable agreement occurs in the 65–75 MeV energy range. It may be observed that the peak-to-valley energy difference is around 30 MeV in all these reactions (

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), which is more than the binding energy of the alpha particle. Perhaps a different reaction mechanism may be operating in this energy range, and certainly not the pre-equilibrium emission. The detailed experimental and theoretical data supporting these findings are provided in the

Appendix A.

3. Materials and Methods

In this study, experimental cross-section data for alpha particle-induced reactions on the cobalt isotope (

59Co) were obtained from the EXFOR library, which provides a comprehensive collection of nuclear reaction data acquired from various experimental studies [

26,

27,

28,

29]. We utilized the experimental data as a benchmark to validate and refine our nuclear reaction models. The data selection focused on measurements relevant to incident alpha particle energies up to 120 MeV, ensuring the inclusion of high-energy reaction channels and minimizing uncertainties associated with low-energy measurements. Nine reactions were studied using datasets by [

16,

17,

18]. To facilitate a meaningful comparison, only data with well-documented uncertainties and standardized measurement techniques were considered.

Theoretical predictions were generated using the COMPLET code, a sophisticated nuclear reaction modeling tool capable of simulating alpha particle interactions with target nuclei across a broad energy spectrum [

6,

30]. The COMPLET code provides reliable predications for many alpha-induced reactions on

59Co, especially when model parameters are optimized. However, significant discrepancies can occur for certain reaction channels due to limitations in modeling complex nuclear mechanisms. The code incorporates various nuclear models, including pre-equilibrium and equilibrium reaction mechanisms, which are essential for accurately describing reactions at different energy ranges. In the present study, the input parameters such as target isotope (

59Co), incident energy grid (up to 120 MeV), nuclear level density options, and optical model potentials were carefully selected based on the recent literature and recommended standards to ensure the consistency and reliability of the simulations [

6,

31,

32,

33].

Simulation procedures involved setting up the input parameters within the COMPLET framework, executing the calculations across the specified energy range, and extracting the resulting cross-sections for various reaction channels. Graphical comparisons, including overlay plots of experimental and calculated cross-sections, complemented the quantitative analysis.

4. Conclusions

Nuclear data models often require precise parameter adjustments to align with experimental results, yet perfect agreement is sometimes unattainable. In such cases, the discrepancies must be factored into uncertainty assessments, while efforts continue to improve the models. Large, and occasionally unphysical, parameter changes can mask true physics, blending physical meaning with empirical corrections. Multiple parameter sets may fit data equally well, creating ambiguity. These challenges stress the need for advanced, microscopic nuclear models with fewer approximations. Although no model will be flawless, adopting superior models reduces parameter tuning and enhances agreement with experiments, thereby minimizing model-related uncertainties. This study highlights the strengths and limitations of the COMPLET code in modeling alpha-induced pre-equilibrium nuclear reactions on cobalt. Theoretically calculated results using the COMPLET code were compared with experimental data from the EXFOR library of the IAEA. The code performs well for simple reaction channels but has difficulty with complex ones, particularly those that emit multiple nucleons. The findings also show that the theoretical predictions are sensitive to input parameters such as exciton number and level density, which significantly affect the results. These demonstrate the significance of optimizing input parameters for accurate nuclear reaction modeling. Although the COMPLET code does not currently support built-in statistical error propagation, its importance is worth considering. Future studies should incorporate uncertainty analysis and compare COMPLET results with those from other nuclear reaction codes, such as TALYS and EMPIRE, to enhance the accuracy and reliability.