1. Introduction

Newtonian fractional-dimension gravity (NFDG) is an alternative gravitational model introduced in 2020–2021 through a series of papers ( [

1,

2,

3], hereafter, referred to as papers I–III, respectively), with the goal of modeling galactic dynamics without using any dark matter (DM) component. The main assumption of NFDG is to consider galaxies, and possibly other astrophysical objects, as fractal structures characterized by a fractional-dimension function

, where

D represents a variable Hausdorff-type fractal dimension, which typically depends on the radial coordinate of the structure being studied and can assume any positive real value (usually,

).

1An intuitive understanding of the concept of fractal dimension is based on fractal geometry, as originally introduced by B. Mandelbrot [

5], where a fractal object containing a detailed structure at small scales is characterized by a fractal dimension that can differ from the standard topological dimension (i.e., in contrast to the standard integer dimension

). Fractal phenomena, displaying self-similarity and fractal dimensions, are being uncovered in stellar systems, galaxies, and other astrophysical structures [

6], thus leading to the applications of fractals to astrophysics and cosmology.

The main motivation for considering a theory of gravity based on a fractional dimension

is that it leads to a gravitational potential of the form

(or

for

), as in Equation (

1) below. This gravitational potential interpolates naturally between the standard Newtonian one (

, for

) and those yielding flat galactic rotation curves, without the need to introduce any DM component. We also note that NFDG should be considered [

1,

2,

3] as a pure modification of the laws of gravity, as briefly outlined in

Section 2. Therefore, NFDG will not affect other fundamental interactions such as electromagnetism, or the way electromagnetic waves propagate in the universe, etc.

In papers I–III, this model was shown to work effectively for general structures characterized by spherical or axial symmetries, as well as for three notable cases of rotationally supported galaxies (NGC 6503, NGC 7814, and NGC 3741), by fitting their rotation curves without using any DM contribution. In a subsequent paper IV [

7], a relativistic version of the model was presented, while in our paper V [

8], four more galaxies were analyzed (NGC 5033, NGC 6674, NGC 5055, NGC 1090) in relation to the so-called external field effect (EFE), and accurate fits to their rotation velocity data were obtained also in these cases.

In all these previous papers, we discussed possible points of contact with other existing alternative gravities (modified Newtonian dynamics—MOND [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]; conformal Gravity—CG [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]; modified gravity—MOG [

24,

25,

26]; etc.), as well as the links with fractional gravity theories in multi-scale spacetimes [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. In addition to these alternative theories of gravity, many other ideas have recently been explored, such as gravitational confinement [

35], graviton–graviton interactions [

36], and unexpected relativistic corrections [

37], including gravitomagnetic effects [

38,

39], just to name a few.

In this short paper, we will apply our NFDG methods to the case of galaxies which appear to have little or no dark matter. In

Section 2, we will consider the case of the ultra-diffuse galaxy (UDG) AGC 114905 [

40,

41], while in

Section 3, we will study another UDG, NGC 1052-DF2 [

42,

43,

44], which is another remarkable case of a galaxy lacking dark matter. In

Section 4, we will also briefly analyze the Bullet Cluster merger (1E0657-56), which is usually referred to as empirical proof of the existence of dark matter [

45,

46].

Our NFDG model will prove to be effective in all these cases: for the first two, it will confirm that these galaxies can be considered to be virtually free of DM, while in the case of the Bullet Cluster, we will show that its dynamics can also be explained by NFDG without including DM contributions.

2. NFDG and the Ultra-Diffuse Galaxy AGC 114905

NFDG is based on a heuristic extension of Gauss’s law for gravitation to a lower-dimensional spacetime

, where

can become a non-integer space dimension. In our previous papers, we introduced a fractional-dimension Poisson equation,

, where

is a generalized

D-dimensional Laplacian (see Ref. [

1], or the more detailed discussion in Ref. [

7]), and

here represents the rescaled mass density. The solution to this Poisson equation, for a point-like mass

m placed at the origin, yields the following NFDG gravitational potential [

8]:

where

G is the gravitational constant, the radial coordinate

r is considered to be a rescaled dimensionless coordinate, i.e.,

, and

is an appropriate scale length, which is required for dimensional correctness in fractional gravity models.

This potential is then generalized to extended source mass distributions, particularly spherically symmetric and axially symmetric distributions, and used to model the three main components of galactic baryonic matter: the spherical bulge mass distribution (if present) and the cylindrical stellar disk and gas distributions. It is assumed that the space dimension

D can be a function of the field point coordinates, but we usually neglect its space derivatives in the computation of the NFDG gravitational field:

This field is usually computed just in the galactic disk plane and it is then expressed as a function of the (dimensionless) radial coordinate R in the same plane, with the scale length included for dimensional correctness. Similarly, the variable dimension function is considered a function of the same radial variable and will characterize each particular galaxy studied with NFDG methods.

Finally, the circular velocity, for stars rotating in the main galactic plane, is simply obtained from Equation (

2) as:

where the NFDG field is computed by using the variable dimension function

mentioned above. The observed rotation velocity data for each galaxy are then fitted by plotting these circular velocities as a function of the radial distance from the galactic center and the best

for each galaxy is obtained by matching the experimental data with the NFDG fits. An alternative method for computing

directly from the galactic mass distributions will be introduced later in this section, but this second method is, at the moment, less effective than the one described above. Full details about the NFDG model can be found in our papers I–V, with the latest version of our computations described in paper V [

8].

It should be noted that NFDG does not imply any external field effect [

8], so that the solar system gravity is essentially due to the Sun’s gravitational field, with other nearby sources at most producing minor tidal forces. At the moment, we have not fully analyzed the role of spherically symmetric sources in NFDG, in order to explain why standard gravity (

) is present at the solar system level, or for any other similar star systems. This will be performed in a future publication which will also study other spherically symmetric sources, such as globular clusters or galaxies with spherical symmetry.

However, in our previous papers dealing with axially symmetric sources, we showed how the dynamics of stars orbiting in a disk galaxy depends on the galactic mass distribution, which might be better described by a fractal structure, and thus by an effective NFDG dimension

, also depending on position. This is the main NFDG hypothesis, supported by how the galactic rotation curves can be effectively described by NFDG methods [

2,

3,

8]. The three situations analyzed in this manuscript are meant to provide additional support for this hypothesis. In the following, we will first apply NFDG to the case of AGC 114905.

The gas-rich ultra-diffuse galaxy AGC 114905 has always been considered an outlier of the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation, but the latest observations and analyses of this galaxy [

40] have shown that its rotation curve can be almost entirely explained by the baryonic mass distribution alone, hence the possibility of the existence of dark-matter-free galaxies. This was not the first galaxy to be shown to be lacking dark matter, but since the NFDG methods outlined above can be easily applied to this case, we will consider AGC 114905 as our first and main example.

We note that AGC 114905 represents a challenge for other alternative theories of gravity, such as MOND, as shown in the original paper by Mancera Piña et al. [

40]. However, a subsequent work by Banik et al. [

47] has shown that the MOND analysis can be consistent with the experimental data, by invoking a much lower inclination angle for this galaxy than that assumed in Ref. [

40].

The data and properties of AGC 114905 were obtained from Refs. [

40,

48], beginning with the mass modeling for this galaxy. In

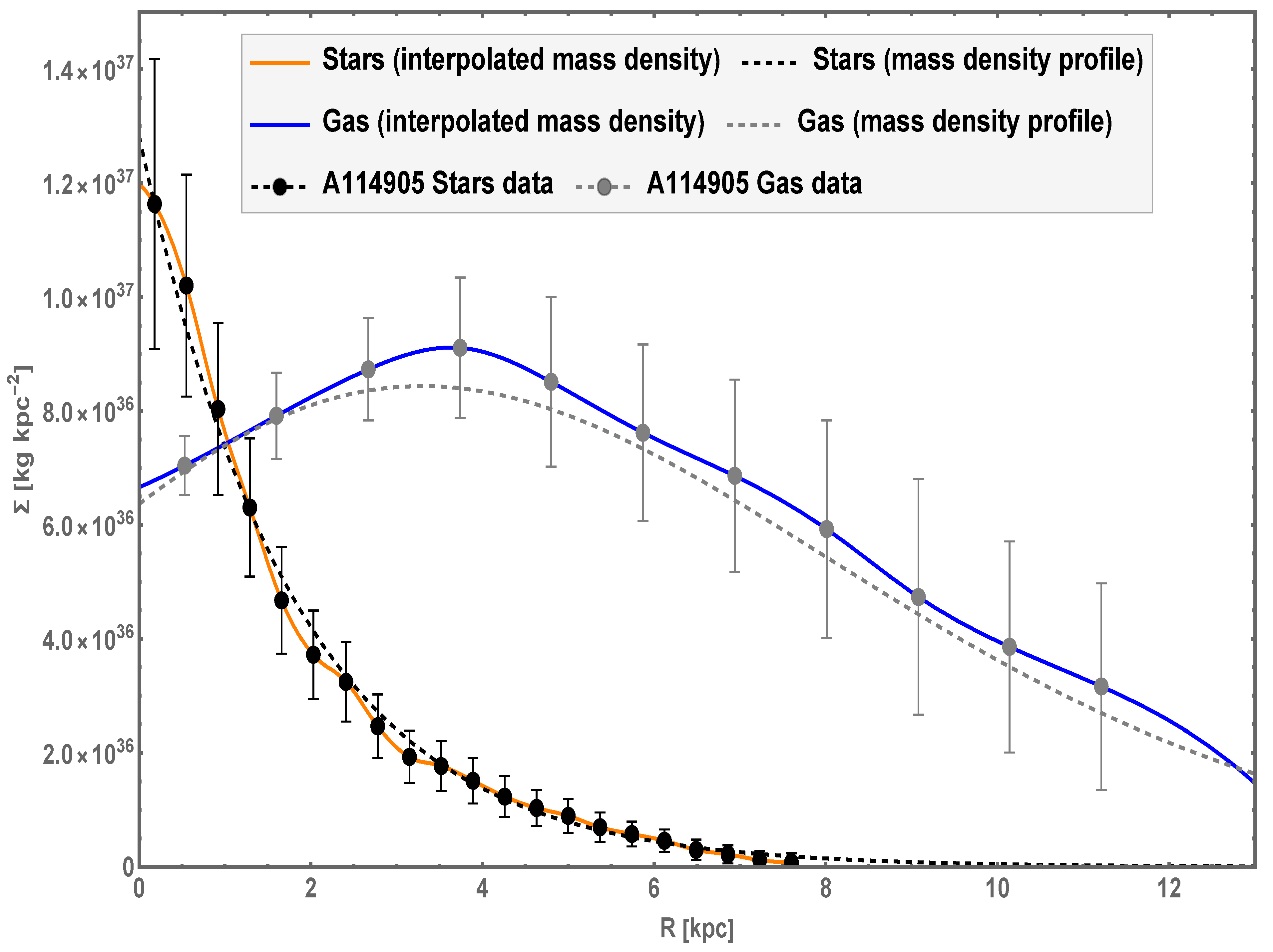

Figure 1, we show the mass data for the two main baryonic components (stars data—black circles; gas data—gray circles) as computed by Mancera Piña et al. [

40,

48] from the original luminosity data. This figure is equivalent to the right panel of Figure 1 in Ref. [

40], although we use different units for the surface mass density

.

These data can then be interpolated with a spline function of the appropriate order (solid-orange curve for stars, and solid-blue curve for the gas component), or we can use the density profiles as in Ref. [

40] (dashed-black curve for stars and dashed-gray curve for the gas component). These profiles for the stellar disk and gas component (HI plus helium) surface mass densities are defined as:

where

and

for the exponential stellar disk profile, while

,

,

and

for the gas profile [

40]. The first profile in Equation (

4) is a simple exponential function typically used to model stellar disks, while the second profile in the same equation is the best analytical fit for the gas component introduced in Ref. [

40].

As in [

40], we adopted a

profile along the vertical direction with a constant thickness of

[

49] for the stellar disk, and a Gaussian profile with a constant vertical scale height

for the gas disk. These vertical profiles, together with the radial ones in Equation (

4), were used as the main input for our NFDG mass distributions.

2

Figure 1.

Surface mass densities for AGC 114905. The data for the stellar and gas components, obtained from Mancera Piña et al. [

40,

48], are interpolated with spline functions (solid-orange and solid-blue curves), or with the mass density profiles in Equation (

4) (dashed curves).

Figure 1.

Surface mass densities for AGC 114905. The data for the stellar and gas components, obtained from Mancera Piña et al. [

40,

48], are interpolated with spline functions (solid-orange and solid-blue curves), or with the mass density profiles in Equation (

4) (dashed curves).

We then used the latest version of the NFDG computation, as detailed in Appendix A of our paper V [

8], in order to obtain the variable dimension function

, which yields the best NFDG fit to the observed circular velocity data for AGC 114905. These experimental data points were obtained from the same sources in Refs. [

40,

48], and are shown in

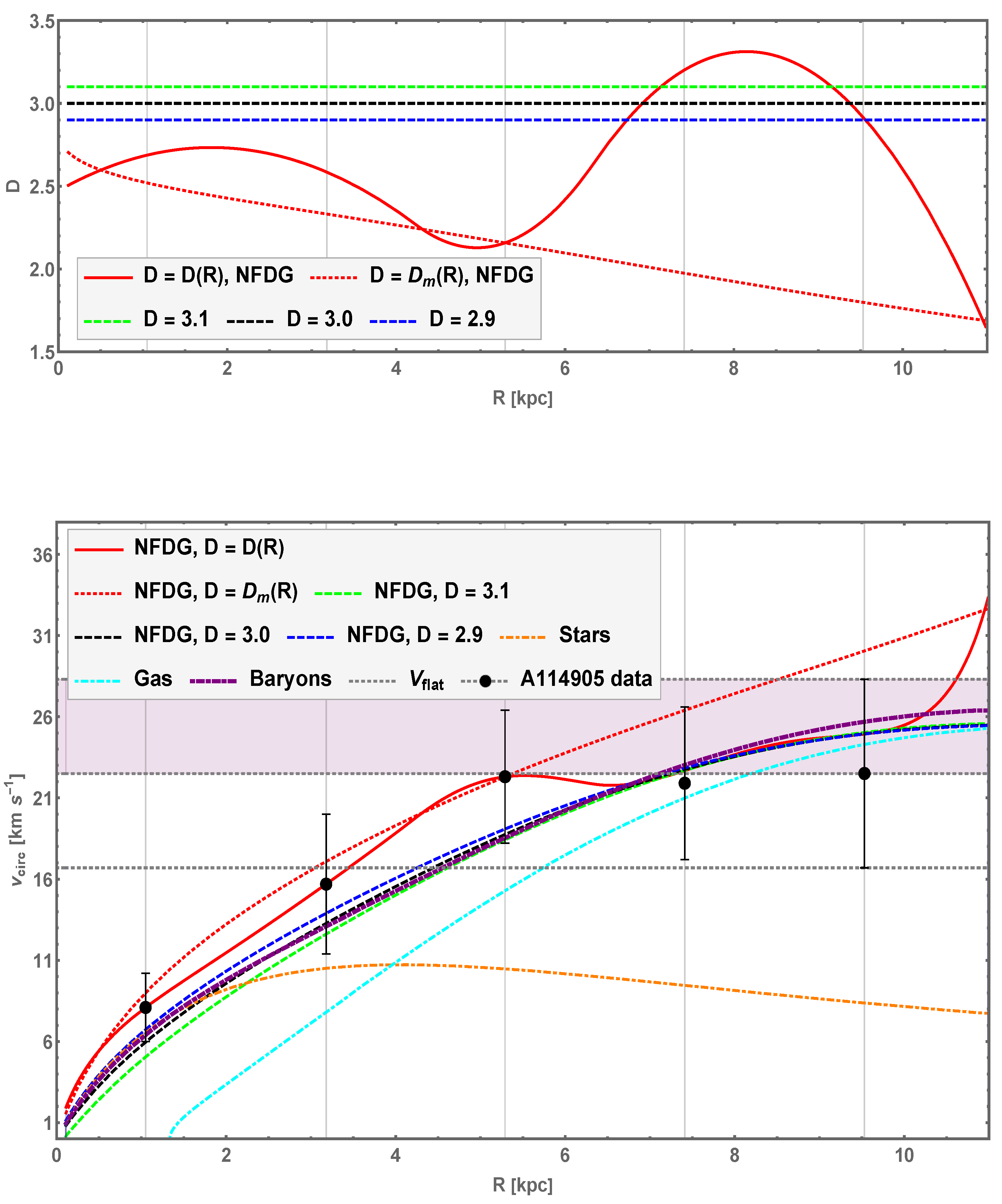

Figure 2 (bottom panel, black circles with error bars), together with the original contributions [

40,

48] expected for the stars (orange—dot-dashed line), gas (cyan—dot-dashed line), and total baryonic mass (stars plus gas—magenta dot-dashed line). These data and related contributions are the same as those shown in Figure 4 of Ref. [

40].

The additional curves shown in both panels of

Figure 2 are instead related to our NFDG computations. In the top panel, we show our best NFDG variable dimension function

as a red-solid line, together with three fixed dimension values

, related to the green, black, and blue dotted lines, respectively. The corresponding NFDG fits to the rotation data are shown in the bottom panel using the lines of the same color/type.

The main NFDG fit is represented by the red-solid line in the bottom panel of the figure. It should be noted that this fit is based on only five experimental data points available for AGC 114905, as opposed to the many experimental points which were available for each of the galaxies studied in our previous papers (based on the SPARC data catalog [

50]). Therefore, the NFDG computations of the variable dimension function

and related rotation velocity (red-solid curves in both panels) were only carried out for the five radial distances of the known experimental data (shown by the vertical gray-thin lines in both panels of

Figure 2), while interpolation was used in between these radial distances, making our predictions somewhat less effective than the results obtained in previous papers.

However, our main NFDG

fit in the bottom panel can effectively match the experimental data: the first three data points are perfectly matched, while for the last two, our red-solid curve is close to the data points and well within their respective error bars. The other NFDG

fits in the bottom panel (in green, black, and blue dashed curves, respectively) were computed in order to compare these fixed-dimension curves with the experimental data, as well as with the original baryonic curve (magenta, dot-dashed). Our NFDG

curve (black-dashed) is close to the original baryonic curve (magenta, dot-dashed, from Ref. [

40]), with minor differences probably due to the different methods used to compute these purely Newtonian components.

Instead considering the NFDG curves (green and blue, dashed lines) over the radial range, we observe that the spread between these curves becomes progressively less pronounced with the increasing radial distances, with all the NFDG fits becoming almost equivalent in the radial region between the last two experimental points. Again, this shows some limitations of our NFDG fits for the last two data points, probably due to the lack of more precise experimental data in this outer radial region.

An alternative NFDG computation is also shown by the red-dotted curves in both panels of

Figure 2. This alternative analysis was based on the discussion in Appendix C of Ref. [

8], where the variable dimension function is considered as a field depending on the radial coordinate

R and denoted by

in the following. In this approach,

is now based on the concept of mass dimension of a fractal system, i.e., the mass dimension of a disk-shaped source is defined as

, with

being the total baryonic mass within radius

R, and

representing a scale length of the system with related mass

.

Following these definitions, it was shown in the same Appendix C of Ref. [

8] that this new field

can be easily computed as:

where

and

. As such, the field

is directly predicted from the baryonic matter distribution alone (described by the total surface mass density

) and not based on the observed rotational velocity data points, as was performed instead using the previous method for

(red-solid curves).

As also discussed in Ref. [

8], the value of

(and related mass

) can be left as a free parameter, or simply chosen by matching one of the experimental data points. We opted for this simpler solution and just arranged this free parameter to match the third data point in the bottom panel of

Figure 2. The resulting circular velocity fit (red-dotted curve) in the bottom panel seems to effectively match the first three data points, as well as the fourth one within its error bar, while the fifth experimental point is not well fitted by this curve. The corresponding red-dotted

curve in the top panel shows a smooth variation in the variable dimension, as opposed to the more pronounced changes in the red-solid

curve, computed with the original NFDG method. We would like to remark that this new method of direct computation of the field

is still a work in progress and will be improved in future publications.

Apart from these limitations of our NFDG fits in the outer radial region, we conclude that our methods also work reasonably well for the case of AGC 114905, as analyzed in this section. We confirm that an NFDG

curve, i.e., purely baryonic, can fit all five experimental data within their error bars, as in the original analysis by Mancera Piña et al. [

40], since our black-dashed curve is close to the magenta dot-dashed curve in the bottom panel of

Figure 2. However, an improved fit to the experimental points is obtained by our NFDG variable

curve, with values for the variable dimension at the radial distances of the experimental points detailed in

Table 1.

From this table and from the top panel of

Figure 2 (red-solid curve), we see that this galaxy is best described in NFDG as having a fractional dimension

2.5–2.7 at lower radial distances around the first two experimental points, then decreasing towards

around the region of the third experimental point, and finally increasing towards

2.9–3.2 in the outer radial region (the last two experimental points). However, the NFDG fits to these last two points are not perfect, as already mentioned above. We conclude that NFDG can also effectively model this galaxy, without any DM contribution, although the quality of our fit is limited by the low number of experimental data points available.

3. NFDG and the Dynamics of NGC 1052-DF2

Another notable case of a galaxy apparently lacking dark matter is the ultra-diffuse galaxy NGC 1052-DF2, as recently studied by van Dokkum et al. [

42,

43,

44]. By measuring the radial velocities of ten globular-cluster objects within this galaxy, it was shown [

43] that the intrinsic velocity dispersion of these clusters is

, leading to a

confidence upper limit of

, with the likelihood level instead giving

(

). These globular-cluster velocity dispersions are very close to the one expected from stars alone,

, thus implying that this galaxy is very deficient in DM and might be the candidate of a purely baryonic galaxy.

Later papers [

44,

51,

52,

53] improved upon the original analysis of NGC 1052-DF2, while confirming the lack of dark matter in this galaxy. In particular, in Ref. [

52], the globular-cluster velocity dispersion was updated as

, in Ref. [

53], the stellar velocity dispersion was revised as

, and in Ref. [

44], the ultra-diffuse galaxy DF2 was seen as part of a group of similar dark-matter free galaxies, probably originated from a bullet–dwarf collision.

It should be noted that the original analysis [

42] of this UDG seemed to be inconsistent with MOND predictions. However, the correct MOND predictions should not only include the internal field of the galaxy, but also the external field due to the proximity to the giant parent galaxy NGC 1052. Including this external field effect into the MOND analysis, it was shown [

54] that MOND predictions (

) are in agreement with the observed velocity dispersions reported above.

3In NFDG, the EFE is not present [

8], but the non-integer variable dimension

D postulated by our model will affect the theoretical computation of the velocity dispersion of NGC 1052-DF2. In this paper, we limit our analysis to a simple argument based on the NFDG version of the virial theorem, while we will leave a more comprehensive analysis of this topic to future work.

In mechanics, the virial theorem [

56] links the average over time of the total kinetic energy

of a stable system of particles with the average over time of the total potential energy of the system

. If the potential energy of a two-particle system is of the form

, i.e., proportional to some power

n of the inter-particle distance

r, it is easy to show that the virial theorem implies

. For the case of standard inverse-square-distance forces, such as Newtonian gravity, we have

and

; however, in NFDG, we instead have

, in view of Equation (

1), and the NFDG virial theorem becomes:

A simple application of the virial theorem to a system of

N astrophysical objects, each of mass

, uniformly distributed inside a sphere of radius

R and total mass

, yields

and

. Using the standard (

) form of the virial theorem and assuming

, the “Newtonian” velocity dispersion

can be estimated from the total mass

M within the radius

R as:

Using the NFDG gravitational potential in Equation (

1) for a constant dimension

and with a rescaled radial coordinate instead of the dimensionless one, i.e.,

(

is the NFDG scale length), it is straightforward to recompute the time-averaged potential energy of the system as

, which can be used in the generalized form of the virial theorem in Equation (

6) to obtain the following NFDG velocity dispersion:

which reduces to Equation (

7) for

. Details of the computations leading to Equations (

7) and (

8) are discussed in

Appendix A.

In order to use Equation (

8), we need to specify the value of the NFDG scale length

, currently undefined. In view of the connections of NFDG with MOND, as described in all our previous papers I–V, we can assume that

, where

is an appropriate reference mass and

is the MOND acceleration constant. In this section, we simply assume that

, the total mass of the spherical system within radius

R.

It should be noted that the choice of the value for the scale length

did not affect the calculations of the rotation curves of AGC 114905 in

Section 2, as well as other rotation curves computed in previous papers, since this quantity is canceled out in the computations. However, in this section and in the following one, we need to use an explicit value for

based on the connection with the MOND acceleration

, as outlined above. Since our first paper [

1], we have heuristically argued that

, as this connection allowed NFDG to recover the MOND flat rotational speed

, the baryonic Tully–Fisher relation, and other fundamental MOND results. In addition, similar connections were used in other fractional gravity models, such as that proposed by Giusti et al. [

57,

58,

59], where the scale length was explicitly set as

, which is practically equivalent to the NFDG relation reported above.

4 Following these considerations, we feel confident that our NFDG relation for

can be used in our current analysis, at least as a first approximation for our study of globular clusters in this section and of the Bullet Cluster in

Section 4.

Although Equations (

7) and (

8) are simplified estimates of the velocity dispersion of a system and should be employed just to determine the order of magnitude of these quantities, we used them in the context of NGC 1052-DF2 to show how

might depend on the effective fractal dimension

D of this galaxy. For example, we considered the original data in Ref. [

43] assuming that the Newtonian velocity dispersion in Equation (

7) corresponds to the one due to stars alone, i.e.,

, as well as used the estimated total stellar mass as the total mass

.

For each of these values of

and

M (central value and errors), we derived the corresponding radius

R from Equation (

7), which was then used in the NFDG velocity dispersion in Equation (

8), together with the appropriate scale length

. This last equation was then numerically solved for the variable dimension

D, assuming that the NFDG velocity dispersion is now set equal to the globular-cluster velocity dispersion, i.e.,

[

43].

The result of this computation is

5:

showing that the increase in the globular-cluster velocity dispersion, compared to the purely baryonic stellar estimate, can be due to an effective decrease in the fractional dimension below the standard

value. However, our NFDG estimate in Equation (

9) is still very close to the standard

, indicating that this galaxy has very little mass discrepancy, and thus confirming the results in the literature.

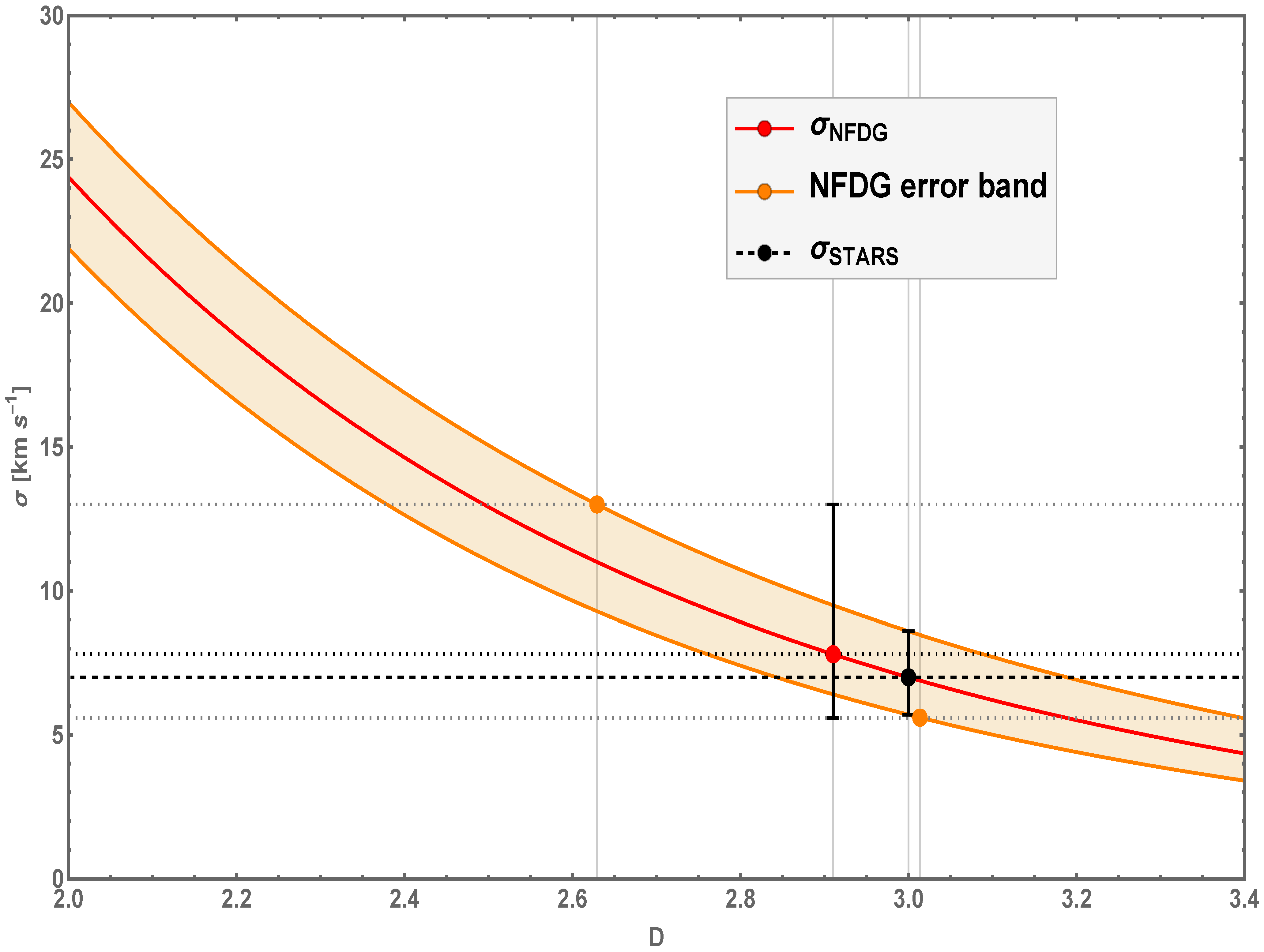

Figure 3 provides a more graphical illustration of our argument. In this figure, we show the dependence of the NFDG velocity dispersion

as a function of the variable dimension

D, following Equation (

8) and the procedure described above. In particular, the stellar velocity dispersion

is shown by the black data point corresponding to a standard

spatial dimension and by the horizontal black-dashed line, while the globular-cluster velocity dispersion

is shown by the red/orange data points (central value/error points, respectively, as also shown with horizontal gray-dotted lines), corresponding to the values of

D reported in Equation (

9):

(red data point),

(orange error data points).

The gray vertical gridlines correspond to all these values of the dimension

D, while the main NFDG red-solid curve and the related orange error band clearly show how an increase in the observed globular-cluster velocity dispersion, compared to the purely baryonic (stellar) one, could be due to a lower fractional dimension of the galaxy, instead of being attributed to the presence of dark matter. In other words, this NFDG analysis based on the extension of the virial theorem in Equations (

6)–(

8) can be used for other galaxies where the discrepancy between baryonic and observed globular-cluster velocity dispersions is usually explained in terms of a DM component. NFDG might be able to explain these discrepancies in terms of a

value of the fractional dimension of the galaxy being studied.

It should again be noted that the NFDG approach to globular-clusters dispersion velocity discussed in this section is only a limited, preliminary study. A more comprehensive analysis should be performed in NFDG by the following methods based on the spherical Jeans equation (see [

60] and the references therein), or others. We will leave this work to future papers on the subject.

4. NFDG and the Bullet Cluster

The Bullet Cluster (BC) merger (1E0657-06) is considered one of the strongest proofs of the existence of DM [

45,

46]. This merger is usually described in terms of the gas components of the two colliding clusters (revealed by the X-ray emissions) which, together with standard luminous matter (stars), represent the baryonic content of the cluster pair. In addition, a strong DM component is revealed by gravitational lensing, pointing towards a direct, empirical evidence of dark matter in this collision [

45].

A simplified but effective way of modeling this collision [

25,

34] can be achieved by considering the two clusters as point masses subject to their reciprocal gravitational attraction.

6 Using the updated values in Ref. [

46], the main cluster is assumed to have a dynamical mass

, while the bullet cluster dynamical mass is estimated as

. These “dynamical” masses include both baryonic and DM contributions, while purely baryonic masses can be obtained using the estimated baryonic-to-total mass ratio,

[

46], i.e.,

and

.

The main objective of this simplified analysis is to obtain the initial infall velocity of the two clusters at a certain separation distance, which was estimated in Ref. [

46] as

at a distance of

Mpc. Treating the system of the two point-mass clusters as isolated and with the clusters at relative rest at infinity, the infall velocity computation follows the standard calculation of the escape velocity, by setting to zero both the total energy and the total momentum of the system:

These equations can be easily solved to obtain the standard, Newtonian, infall velocity

at the separation distance

r:

Using the total cluster masses reported above (including DM) and the separation distance

Mpc, one obtains

, in line with the expected results [

46], while using the purely baryonic masses for the two clusters, also reported above, one would instead obtain

, clearly showing that baryonic masses alone, combined with standard Newtonian gravity, are unable to effectively describe the cluster merger.

However, the same argument can now be used in our NFDG model, by considering the appropriate extension of the gravitational potential energy and using only baryonic masses, since NFDG does not include DM components:

which follows from the NFDG gravitational potential for

in Equation (

1). Using this NFDG potential energy instead of the Newtonian one in Equation (

10) and solving for the NFDG equivalent infall velocity, we obtain:

In this last equation, we introduced the rescaled radial coordinate instead of the dimensionless one, i.e.,

, with

representing as usual the NFDG scale length. It is easy to check that Equation (

13) is reduced to Equation (

11) for

.

We can now assume that the infall velocity is the same as the one obtained with Equation (

11), using the total dynamical masses (including DM) of the two clusters, i.e., set

and solving Equation (

13) for the value of the fractional dimension

D which would yield the above infall velocity at the same separation distance

Mpc. Obtaining a reasonable value for

D (e.g.,

) would show that NFDG can explain the BC dynamics as a fractional-dimension effect, at least within the limits of this simplified model.

In order to numerically solve Equation (

13), we again need to specify the value of the NFDG scale length

, currently undefined. As performed in the previous section, we set

, where

is an appropriate reference baryonic mass and

is the MOND acceleration constant. The reference mass, although arbitrary, should be related to the baryonic masses of the two clusters, with some possible choices being the total baryonic mass

, the individual baryonic masses of each cluster (

, or

), the reduced mass of the cluster system (

), etc.

Table 2 shows the values of the fractional dimension

D which would yield the infall velocity of

in NFDG for different choices of the reference mass

, as outlined above. We can see that all these values for

D are within a reasonable range of

2.4–2.5, similar to the values obtained in previous NFDG studies of the dynamics of individual galaxies. Although our analysis of the BC is based on a simplified model of this merger, we conclude that NFDG is potentially able to describe the nature of this phenomenon without using any DM component.