Abstract

X-ray flares are frequently detected in the X-ray afterglow light curves and are highly correlated with the prompt emission of gamma-ray bursts (GRBs). We compile a comprehensive sample of X-ray flares up to 2021 April, comprising 697 flares. We classify the total sample into four types: early flares ( s), late flares ( s), long gamma-ray burst (LGRB) flares and short gamma-ray burst (SGRB) flares, and analyze the distributions and relationships of the flare parameters. It is found that the early flares have a higher frequency, shorter duration, and more asymmetrical structure. In addition, the distributions of the morphological parameters of the SGRB flares are similar to those of the LGRB flares. We also find that the durations and rising (decay) times of the early flares are positively correlated with the peak times, but the late flares follow the different dependent relations. There is a strong anti-correlation between the peak luminosities () and the peak times of the flares, e.g., for the LGRB flares, and for the SGRB flares, respectively. Furthermore, the peak luminosity is highly dependent on the isotropic energy () for the early LGRB flares, the best fit is (). We also find a tight three-parameter correlation, (). All the late flares fall into the confidence region defined by the early flares. In terms of the point of kinematic arguments, both the SGRB and LGRB flares support a common scheme of internal origin. The SGRB flares have similar properties to the LGRB flares, suggesting that both of them share a similar physical mechanism from the late-time activity of central engine.

1. Introduction

Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are the most energetic and mysterious phenomena in the universe. Traditionally, GRBs are roughly classified into two subgroups based on their duration distribution: long gamma-ray bursts (LGRBs) with s and short gamma-ray bursts (SGRBs) with s [1,2]. It is generally accepted that LGRBs originate from the collapse of rapidly rotating massive stars [3,4], while SGRBs are associated with the coalescence of binary compact objects (double neutron stars or a neutron star and a black hole) [5,6,7].

Since the narrow-field instrument X-ray Telescope (XRT) on board Swift was operated with more rapid locating capability and higher sensitivity [6,8,9,10,11,12,13], the well-sampled GRBs with early afterglow detection and available redshift measurement were significantly accumulated [12,14,15,16]. Especially, a canonical X-ray afterglow light curve characterized by five components is revealed [17,18,19]: an initial steep decay (with a typical slope index around 3 or steeper), a shallow decay (the so-called plateau, with a typical slope index around 0.5), a normal decay (with a typical slope index around 1.2), a possible steep decay component following a jet break, as well as one or more X-ray flares. Flares can be detected in almost half of the early X-ray light curves [19,20], which show a steep rise and then steep decay characteristics. There is also a clustering phenomenon in the peak time of X-ray flares, most of which occur at the early time interval around s [21]. Statistically, X-ray flares can appear in different types of GRBs [22,23], and even different environments. Meanwhile, Ref. [24] reported the temporal behaviors and the spectral properties of the X-ray flares are similar to those of the prompt emission of GRBs. It is believed that the flares may share the same physical origin as the prompt emission pulse, indicating that both of them originate from the same central engine [8,11,12,17,19,25,26,27,28,29]. Ref. [30] found that flare lags evolve with time after collecting the multi-flare GRBs, which is consistent with the prompt emission pulses. The central engine of GRBs does not seem to shut down immediately after the prompt emission phase, the duration can be very long. Especially, the X-ray flares provide the important clues to the late-time activity of the central engine [31].

Ref. [8] reported two GRBs with strong X-ray flaring activity. The energy contained in the first flare of GRB 050502B is roughly consistent with the prompt emission phase detected in Swift/BAT, which puts the energy budget of the flare in doubt. From the kinematic view, Ref. [32] proposed a criterion to separate the internal and external origin of flares. Ref. [19] shaped the early X-ray light curves and explained that flares favor internal shock or similar energy dissipation at a later time, rather than the afterglow effect. Ref. [27] analyzed the rapid decay components of the flares and those of the prompt emissions, suggesting an erratic and unpredictable central engine. Each X-ray flare forms a unique and distinct central engine activity episode, and the central engine remains active after the termination of the prompt emission. Ref. [33] focused on seven extremely late X-ray flares (the peak time s) to investigate the central engine of such flares based on the hypothesis of internal origin, a fast-rotating neutron star with strong bipolar magnetic fields may be responsible for such flares. Various models have been proposed to explain the flares, such as the fragmentation of a collapsing star [34], fragmentation of an accretion disk [35], and the magnetic reconnection process [20,36]. Another similar schemes can be referred to [11,28,37,38,39,40,41].

Previous studies have also found some correlations of the X-ray flares with continuously updated samples. Ref. [26] found that the width and the energy of the early flares (with a temporal boundary s) follow a power-law correlation and the 0.3–10 keV peak luminosity of the early flares decays with the peak time, i.e., and , respectively. Ref. [36] fitted a hybrid sample of X-ray flares and re-found that the peak luminosity correlated with the peak time: . In addition, the power-law distributions of the energies, durations, peak fluxes, and waiting times of the X-ray flares are similar to those of solar flares, indicating that the physical origins of these two phenomena are similar, which can be explained by a fractal-diffusive, self-organized, criticality model [20,36]. Ref. [23] studied the possible SGRB X-ray flares in a small sample for the first time. They claimed that the SGRB flares show similar mechanisms to the long ones, despite the distributions of the SGRB flares being located at lower energies. However, due to the limited size of SGRB flares (only 8 SGRBs), the quantitative conclusion may require further investigation. In this work, we further analyze the characteristics and physical nature of the flares based on a large sample.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the sample selection and the data analysis are described. In Section 3, the distributions and correlations of X-ray flares with different classes are presented. In Section 4, we give the constraints on flares through the kinematic parameters. Conclusions and discussions are shown in Section 5. The cosmological parameters in a flat universe with km s−1 Mpc−1, , and is adopted throughout this paper.

2. Sample Selection and Data Analysis

The 0.3–10 keV flux data of X-ray light curves (LCs) are taken from the website of the UK Swift Science Data Centre at the University of Leicester http://www.swift.ac.uk/xrtcurves/ (accessed date: 1 May 2021) [10,42]. We select all GRBs with X-ray flares observed from the Swift/XRT instrument for the last 15 years (up to April 2021). To extract the physical parameters of the flares, we adopt the following criteria: flare candidates can be obviously distinguished from the X-ray afterglow and generally have a complete structure, including significant rising and decaying phases. Then, we obtain 697 bright X-ray flares, including 677 LGRB flares and 20 SGRB flares. Based on the peak time of the fares, there are also 636 early flares ( s) and 61 late flares ( s).

An X-ray afterglow LC contains one or more power-law segments and some flares, various LCs can be assembled from different components [36]. We adopt the fitting method used by [15] to fit the X-ray afterglow LCs. First, the global feature of the LCs is examined based on visual inspection. Then, the minimum number of basic components was introduced. Sometimes, it must add potential components by judging whether the chi-square value is close to 1. This fitting method is also similar to that of [15,33,36,43,44]. Usually a smooth broken power-law (SBPL) function,

and a single power-law function,

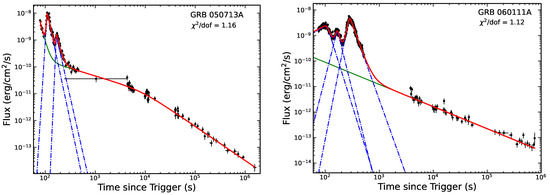

were applied to fit the the flares and underlying continuums [15,33,36,43], where , and are the temporal slopes, is the break time, and represents the sharpness of the peak. The selection of does not significantly affect the value of [43]. is usually fixed to 3 or 1 in the flare fitting. However, in some flares, can significantly affect the goodness of fitting, because the peaks of some flares are not sharp but rather smooth. Occasionally, the steep decay, the shallow decay and the jet break might appear in the LC, which can be jointly fitted by the above empirical formulas. The two examples of the best-fitting LCs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Best-fits for the X-ray LCs of GRB 050713A and GRB 060111A. The blue dot-dash lines show the best fit of individual flare, and the green lines show the underlying continuum component. The red lines show the best-fits of whole LCs of GRBs. GRB 050713A is a typical LC that two flares superimpose on the Nousek-Zhang power-law. In some cases, such as 060111A, the underlying continuum deviates from the Nousek-Zhang power-law with incomplete structure.

The other parameters of flares are derived as follows. The peak time of a flare can be transferred from the break time as [33]:

and the peak flux of a flare at is

The duration (Δt) of a flare is defined as full width at half maximum (FWHM), which refer to [15,21,33]. The start time (the end time ) is defined as the start point (the end point) at half peak. The rise time can be derived from and the decay time . Each X-ray flare can be fitted with its corresponding SBPL function, as shown in the Equation (1). We also calculate , relative variability of flux and relative temporal variability , where is the increased flux of the flare at , and F is the flux of the underlying continuum at [16,21,25,26,32,33,45].

For the GRBs with measured redshift, we can calculate the flare parameters in the rest frame and explore the intrinsic properties of flares. The 0.3–10 keV isotropic energy () of a flare can be calculated by the following formula [33,36,46]:

Here, the flare fluence () is calculated by integrating the corresponding SBPL function of the flare from the start time to the end time in the energy band of Swift/XRT [12,33,36]. Additionally, is the luminosity distance of GRBs [47,48]:

The peak luminosity of a flare can be derived from the formula . Cautiously, the k-correction is not considered in this paper like [33]. All the observed temporal parameters can be transferred to the rest frame by .

The fitting and derived parameters of the flares are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, where the errors of these quantities are calculated by the error propagation formula. We take 10 percent of the central value as the error if the data have no error, or its error is greater than itself.

Table 1.

The Main Physical quantities of Flares.

Table 2.

The Derived Physical Quantities of Flares with Redshift.

3. Statistical Properties of the X-ray Flares

3.1. Distributions of Flare Parameters

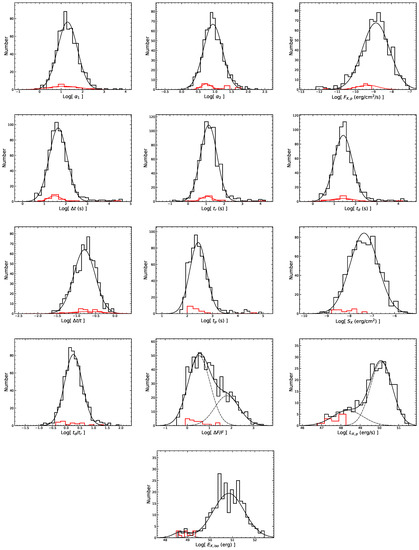

The distributions of the observed X-ray flare parameters (i.e., , , , , , , and ) from the fitting and the other derived quantities (i.e., , , , and ) are demonstrated in Figure 2. For the LGRB flares, it is found that all distributions of the flare parameters are lognormal or logarithmic bimodal. We use a single or double Gaussian function to fit the distributions. The distributions of , , , , , , , , and can be fitted by a single Gaussian function. The median values and the standard deviations of these parameters are ∼ ( ∼ ), ∼ 8.71 ( ∼ ), ∼ erg cm−2 s−1 ( ∼ ), ∼ s ( ∼ ), ∼ s ( ∼ ), ∼ s ( ∼ ), ∼ ( ∼ ), ∼ s ( ∼ ), ∼ erg cm−2 ( ∼ ) and ∼ ( ∼ ), respectively. In addition, the distributions of the , , , and slightly deviate from lognormal distribution, we still use the Gaussian function to fit these quantities. Apart from , the other quantities all extend to the larger value. We also find that , and deviate from the lognormal distributions significantly and show the obvious bimodal distributions. Thus, a double Gaussian function is adopted to the fitting. We obtain the median values and the standard deviations are ∼ ( ∼ ), ∼ erg s−1 ( ∼ ) and ∼ erg ( ∼ ) for the high peak, and ∼ ( ∼ ), ∼ erg s−1 ( ∼ ) and ∼ erg ( ∼ ) for the low peak. The distribution results are listed in Table 3.

Figure 2.

The distributions of the parameters for the X-ray flares. The black (red) solid lines represent the best fitting results for the LGRB (SGRB) flares with single or double Gaussian functions.

Table 3.

Best-fit Parameters of X-ray Flare Distributions.

For the SGRB flares, , , , , , and are basically lognormal. However, , and for the SGRB flares obviously deviate from the lognormal distribution. The median values and the standard deviations of , , , , , and for the SGRB flares are ∼ ( ∼ ), ∼ ( ∼ ), ∼ erg cm−2 s−1 ( ∼ ), ∼ s ( ∼ ), ∼ s ( ∼ ), ∼ s ( ∼ ) and ∼ ( ∼ ), respectively. Similarity, , , , and are slightly span to the larger value. Unfortunately, we can not give the statistical results of , and for the SGRB flares due to the small numbers. We find that , and are all located at the weak region. Noteworthily, in SGRB sample is the only quantity located at the high peak defined by the LGRB flares, which is in agreement with the distribution shown by [23].

As shown in Figure 2, the distributions of the temporal parameters for the SGRB flares (, , , , , , and ) are similar to those of the long ones. It is a self-similar behavior in the flare profile through flare emission [45], whether different types of GRBs or different time sequences. Then, the values of , , , and of the SGRB flares are weaker or smaller than those of the long ones. It is known that the isotropic energy and luminosity during the prompt emission phase of SGRBs are different from those of the long ones, and the flare is tightly related to the prompt emission phase. The morphology of distribution obtained from the previous studies [25,36,50] is similar to our results. The mean value of derived by [36] is 24.64. Our result is smaller than their result. It is more likely that the duration time is defined in a different way compared to [36]. We consider the significant part of a flare, which shows how strict the definition of the duration time in describing the burst or the flare [25]. in the LGRB sample obtained from [16] by the double Gaussian function fitting are 0.50 () and 2.10 (), which is consistent with our result for the LGRB sample. In addition, there are no cases of the SGRB flare with exceeding 2, which is consistent with [16]. It can generally exclude the origin of external shock [25]. Ref. [45] obtained a similar result of as well. The median values for the late flares and the early flares are 0.28 and 0.23, respectively. But the late flares have a larger standard deviation ( compared with ), which is not dependent with redshift. Again, the smaller value of in this paper may be due to a different definition of the duration. The distribution of the peak luminosity , which span from erg/s to erg/s, is wider than that of [36].

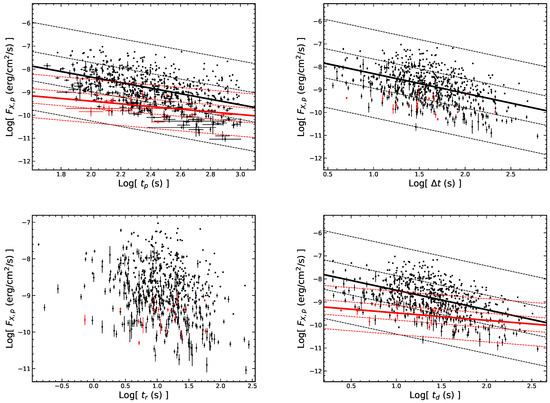

3.2. Two-Parameter Correlations of Early Flares and Late Flares

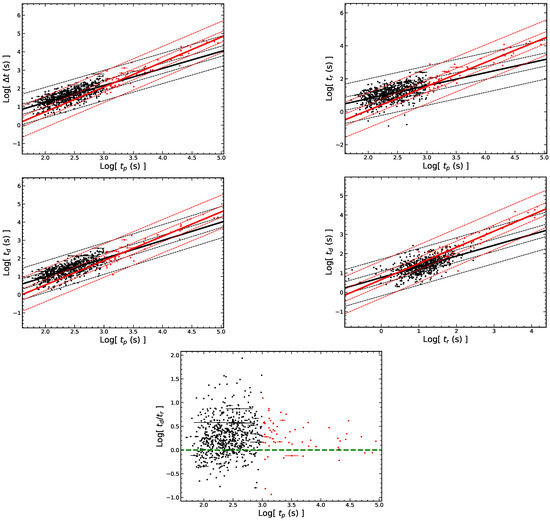

We first study the relationships among the observed temporal quantities. , and of the flares as a function of are shown in Figure 3. We find that is correlated with both for the early and late flares. We perform the regression analysis for the total sample, i.e., with a Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.86 and a chance probability . This result is similar to the - correlation found in [26,36,45]. Similarly, and are also correlated with . Besides, there is a strong correlation between the rise time and the decay time, i.e., for the total flares, with r = 0.80 and . It is known that the ratio can reflect the asymmetry of the flares and we find that the early flares are more asymmetric with a larger . As shown in the last panel of Figure 3, the value of gradually tend to at later time. The results of the correlations are shown in Table 4.

Figure 3.

The correlations among the temporal parameters of flares. The black (red) dots represent the early (late) flares. The black (red) solid lines represent the best fits for the early (late) flares. The dashed lines represent the 1 and 3 confidence regions. The green dashed line in the last graph represents the axis of = 1. The regression results with a correlation coefficient less than 0.3 are not shown on the figure.

Table 4.

The correlations of early and late flares.

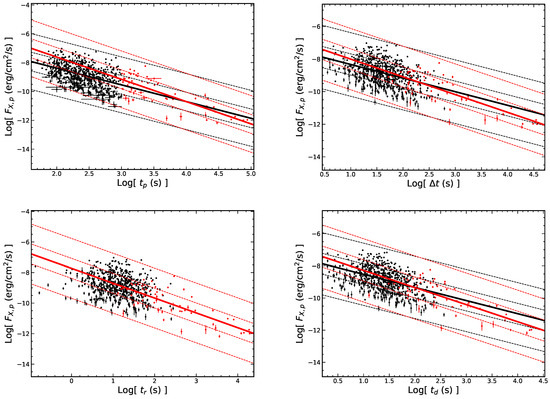

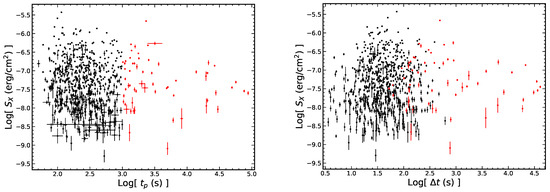

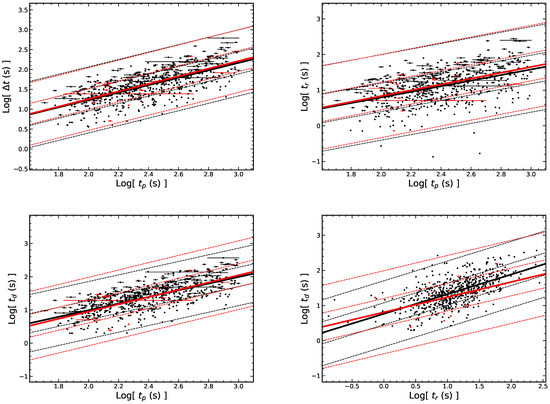

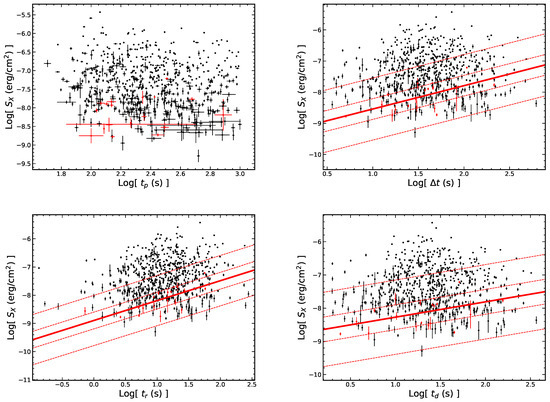

The relationships between the peak flux () and the temporal quantities of the flares are demonstrated in Figure 4. We find that there is a anti-correlation between and for all the sample, i.e., with r = and . Obviously, the - correlation for the late flares is tighter than the early flares. As shown in Figure 5, we find that the fluence of the flares () is independent of the temporal quantities of the flares. Figure 6 (upper left) shows the relationship between and . For the early flares, with r = 0.85 and . For the late flares, with r = 0.67 and .

Figure 4.

The correlations between the peak flux of flares and the temporal quantities in the observer frame. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 3.

Figure 5.

Relationships between the flare fluence and the temporal quantities in the observer frame. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 3.

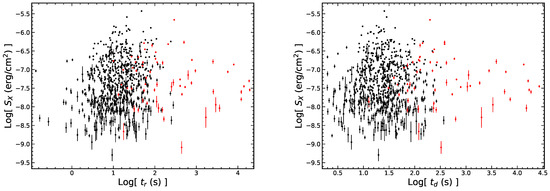

Figure 6.

The - correlation and the - correlation are shown at top and bottom panel, respectively. The left panel are derived from the early and late flares, while the right panel are derived from the total flares. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 3.

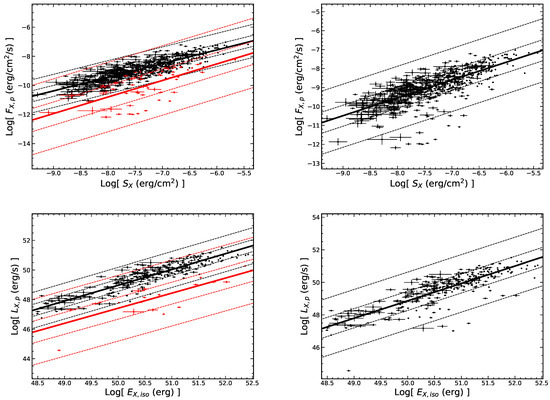

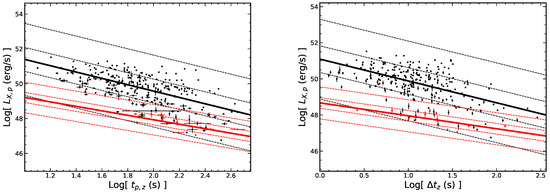

It is known that the rest frame relationships can reflect the physical nature of the flares. We investigate the relations among the rest frame quantities of the flares and find that the peak luminosity () is correlated with the temporal parameters of the flares as shown in Figure 7. For all flares, with r = and , which is consistent with the total sample of [36,45]. This result indicate that the dimmer X-ray flares are more likely to appear at the later time and have a longer duration. Besides, the flare energy () is independent of the temporal parameters as shown in Figure 8. From the Figure 6 (bottom panel), a more tight correlation between and in the rest frame is found. For the early flares, with r = 0.91 and . For the late flares, with r = 0.78 and . Ref. [36] obtained a similar result, i.e., .

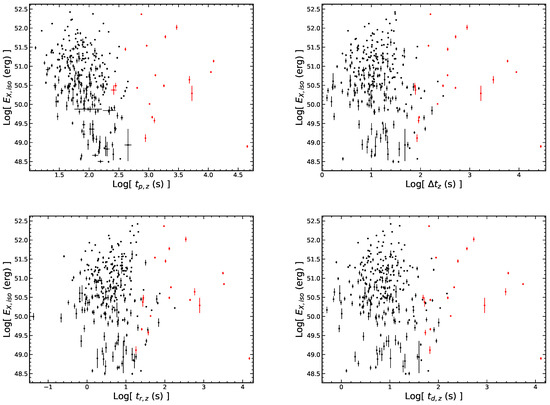

Figure 7.

The peak luminosity () of flares is correlated with the temporal parameters in the rest frame. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 3.

Figure 8.

No correlations are found between the and the temporal quantities in the rest frame. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 3.

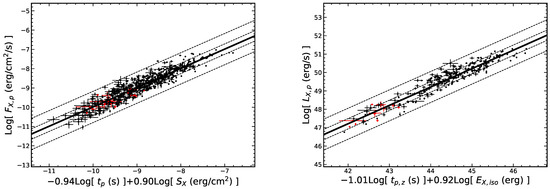

3.3. Two-Parameter Correlations of LGRB Flares and SGRB Flares

We further analyze the correlations for the LGRB flares and SGRB flares and find that the correlations among the temporal parameters of the LGRB flares are similar to that of the short ones as shown in Figure 9. We also find that the relationships between and the temporal quantities/fluence are different for the LGRB flares and SGRB flares (see Figure 10 and Figure 11). For the LGRB flares, with r = and , and with r = 0.85 and . For the SGRB flares, with r = and p = 0.0983, and with r = 0.59 and p = 0.0079. The integrated fluence of the flare is independent of the temporal quantities for both the LGRB flares and SGRB flares as well (Figure 12). The results of correlations are shown in Table 5.

Figure 9.

The correlations between LGRB and SGRB flares about the temporal parameters are similar. The black (red) dot represents LGRB (SGRB) flares. The dashed lines represent the 1 and 3 confidence regions. The regression results with a correlation coefficient less than 0.3 are not shown on the figure.

Figure 10.

The correlations between the peak flux of flares and the temporal quantities in the observer frame. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 9.

Figure 11.

The - correlation and the - correlation are shown at left and right panel of the figure, respectively. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 9.

Figure 12.

The correlations between the flare fluence and the temporal quantities are shown in the observer frame. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 9.

Table 5.

The correlations of LGRB flares and SGRB flares.

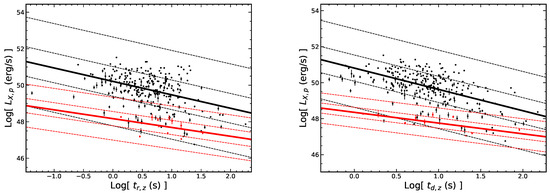

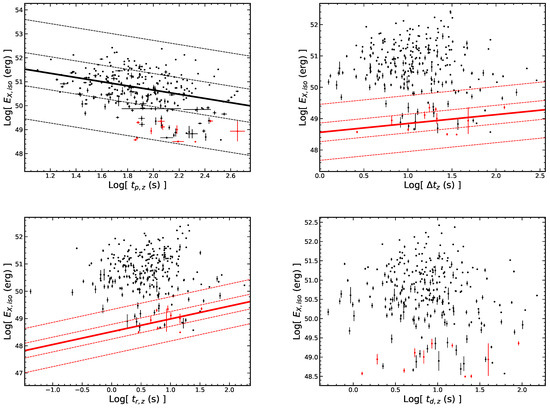

Similarly, we analyze the rest frame correlations for the LGRB flares and SGRB flares. As shown in Figure 13, For the LGRB flares, (r = and ). For the SGRB flares, (r = and ). The - correlation in our SGRB flares quantitatively confirms the conclusion of [23] that there is a factor of approximately 0.01 smaller than the long ones. is also correlated with the other temporal quantities (, and ) for the LGRB flares and SGRB flares. In addition, we do not find the significant dependence of the X-ray flare total energy () with the temporal quantities in the rest frame for either the LGRB flares or SGRB flares as shown in Figure 14. We also analyze the relationship between the peak luminosity and the total energy for the LGRB flares and SGRB flares and find that these two quantities are correlated, and the correlation of the SGRB flares may not be as tight as that of the long ones (see the right panel of Figure 11). For the LGRB flares, with r = 0.81 and . For the SGRB flares, with r = 0.19 and p = 0.5532.

Figure 13.

The peak luminosity () of flares is correlated with the temporal parameters of flares in the rest frame. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 9.

Figure 14.

No correlations are found between the and the temporal quantities in the rest frame. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 9.

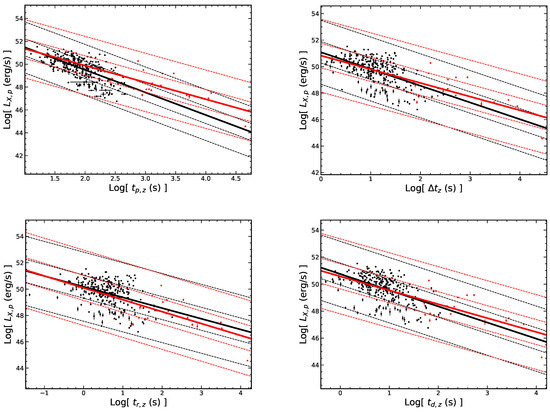

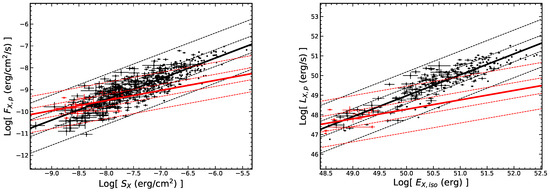

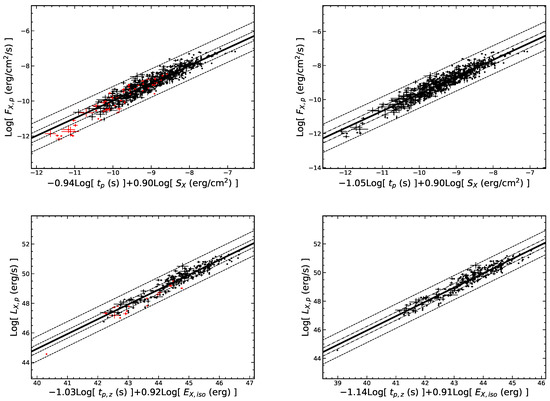

3.4. Three-Parameter Correlations of Flares

We extend the - correlation and the - correlation by adding a third parameter (the peak time of the flare) and find that the -- correlation and the -- correlation become much tighter. For the early flares, with r = 0.93 and , and (r = 0.96, ). As shown in the Figure 15, all late events almost fall into the 3 confidence region of the three-parameter correlations defined by the early flares. The results of the regression analysis are listed in Table 6.

Figure 15.

The -- correlation and -- of flares. The black (red) dot represent the early (late) flares. The left panel is derived from early and late flares, while the right panel is derived from total flares. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 3.

Table 6.

The three-parameter correlations of flares.

We also analyze the above three-parameters for the LGRB flares and SGRB flares and obtain (r = 0.93 and and (r = 0.95 and ) for LGRB flares, while (r = 0.80 and ) and (r = 0.86 and p = 0.0008) for SGRB flares. The results are presented in the Figure 16 and Table 6. It can be seen from the fitting results that the slope index of varies significantly, while the slope index of the peak time is consistent within the error range.

Figure 16.

The -- and -- correlation of LGRB and SGRB flares are shown at left and right panel, respectively. All symbols and descriptions are the same as in Figure 9.

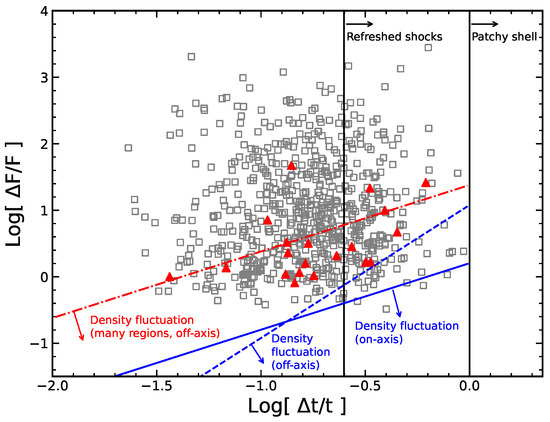

4. Origin of the Flares

The kinematic arguments proposed by [32] can give limits on the flux variability and timescale variability . In Figure 17, all the X-ray flares in our sample are demonstrated in the - plane, where the fraction of cooling energy and are adopted referring to [32]. We find an apparent discrepancy existing between our sample and that of [23]. The of the second flare in GRB 050724 is 0.62 in our sample, while [33] obtained the value of 1.46. Additionally, the of GRB 050724 in our sample is close to that derived by [21]. It is shown that this analysis is significantly affected by the fitting model and the goodness of fitting. All flares in our sample are located on the left side of the axis , confirming that flares cannot be responsible for the scheme of patchy shells [25]. The flare with may occur at an extremely late-time, but our samples prefer that a majority of flares can be explained by internal shocks. Contrarily, regardless of the LGRB flares or SGRB flares, more flares prefer the constraint of refreshed shock and off-axis density fluctuations. These results are in agreement with [21,23,25,26].

Figure 17.

The relative variability of flux and relative temporal variability plotted on the constraint plane of the kinematic parameters [32]. Besides, the LGRB flares (grey squares) and the SGRB flares (red triangles) are demonstrated, respectively. The black solid lines shown are the case of patchy shells () and refreshed shocks (). Off-axis density fluctuation of single variable regions () and of many variable regions () are demonstrated by blue dash line and red dot dash line, respectively. The case of on-axis density fluctuations () is plotted by blue solid line. The fraction of cooling energy ∼ and ∼ 1 are adopted here. More detailed description can refer to Ref. [32].

Compared to the LGRB flares, none of the SGRB flares in our sample conform to on-axis density fluctuations and off-axis density fluctuations of single variable regions. 4/20 SGRB flares can only be interpreted as internal shocks. Although the promising explanation for flares is the internal shock origin, the SGRB flares may have a discrepancy compared to the long ones. Ref. [45] studied the late flares and showed that quite a few late flares satisfy the scheme of on-axis fluctuations. Thus, we speculate that the scarcity of the late SGRB flares is the main reason accounting for this phenomenon. Whether it is due to the scarcity of the late SGRB flares or the observational selection effect is worth exploring in the future.

5. Conclusions

In this work, 697 bright X-ray flares of GRBs detected by Swift/XRT are extensively analyzed up to 2021 April, including 677 LGRB flares and 20 SGRB flares. Among this sample, there are 636 early flares ( s) and 61 late flares ( s). We apply the smooth broken power-law function to fit all the X-ray flares, and obtain their physical parameters.

Obvious features are found after analyzing the morphological structures of X-ray flares in the time domain: The peak times of the flares span from s to s, and there is clustering around s. In addition, the flare durations are mainly distributed between and s. The early flares appear with higher frequency, shorter duration, and more asymmetry. Especially, the morphological features of the SGRB flares are similar to those of the LGRB flares. This implies that the flares with different origins may have similar radiative mechanisms. The 0.3–10 keV isotropic energy (peak luminosity) of the flares is mainly distributed from to erg ( to erg/s). It is noted that the isotropic energy and peak luminosity of the SGRB flares is about two or three orders of magnitude less than that of the LGRB flares. The distributions of and for the LGRB flares are mainly bimodal. Although the SGRB flares are not statistically significant due to their limited number, they are concentrated at the weak end of the LGRB flares. The SGRB flares are less energetic on average than the LGRB flares, which is similar to the prompt emission.

We also analyze the relationships between the parameters of the X-ray flares, and find some tight correlations. There is an anti-correlation between the peak luminosity and the peak time of the flares, i.e., , which indicates that the later flares are usually dimmer. Furthermore, - correlation () and the distribution of show that the later flares have a broader duration and a more symmetric structure. We also find that the peak luminosities of the flares are tightly correlated with their total energy, i.e., . By adding the third parameter (the peak time of the flare), we obtain a more tighter three-parameter correlation (r = 0.96). There is no significant time evolution of the correlations between the early flares and late flares. In addition, we do the first quantitative analysis on the - correlation of SGRB flares, confirming the conclusion that this correlation of the SGRB flares differ from the long ones by a factor of 0.01 [23].

From the point of kinematic arguments, the SGRB flares and LGRB flares have a similar appearance in the - plane, irrespective of the possible observational selection effect of the SGRB flares. Almost all flares support a common scheme of internal origin as shown in Figure 17. From the different viewpoint, some studies also concluded that the LGRB flares and SGRB flares may have a common origin [20,23]. Our results confirm this scheme. To sum up, we conclude that the flare emission of LGRBs and SGRBs have similar physical mechanisms, but the energy budgets of these two types are different.

Author Contributions

Y.-R.S. and F.-W.Z. led the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. X.-K.D., S.-Y.Z. and W.-P.S. helped with the data analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by NSFC under grants 11763003, and by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (No. 2022GXNSFDA035083).

Data Availability Statement

The data are available at the UK Swift Science Data Centre at the University of Leicester http://www.swift.ac.uk/xrtcurves/.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewer for important suggestions that helped us to improve the presentation of our results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kouveliotou, C.; Meegan, C.A.; Fishman, G.J.; Bhat, N.P.; Briggs, M.S.; Koshut, T.M.; Paciesas, W.S.; Pendleton, G.N. Identification of Two Classes of Gamma-ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. 1993, 413, L101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-B.; Choi, C.-S. An Analysis of the Durations of Swift Gamma-ray Bursts. Astron. Astrophys. 2008, 484, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFadyen, A.I.; Woosley, S.E. Collapsars: Gamma-ray Bursts and Explosions in ”Failed Supernovae”. Astrophys. J. 1998, 524, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; de Ugarte Postigo, A.; Leloudas, G.; Krühler, T.; Cano, Z.; Hjorth, J.; Malesani, D.; Fynbo, J.P.U.; Thöne, C.C.; Sánchez-Ramírez, R.; et al. Discovery of the Broad-lined Type Ic SN 2013cq Associated with the Very Energetic GRB 130427A. Astrophys. J. 2013, 776, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, E. The Environments of Short-duration Gamma-ray Bursts and Implications for Their Progenitors. New Astron. Rev. 2011, 55, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrels, N.; Ramirez-Ruiz, E.; Fox, D.B. Gamma-ray Bursts in the Swift Era. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2009, 47, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakar, E. Short-hard Gamma-ray Bursts. Phys. Rep. 2007, 442, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, D.N.; Romano, P.; Falcone, A.; Kobayashi, S.; Zhang, B.; Moretti, A.; O’Brien, P.T.; Goad, M.R.; Campana, S.; Page, K.L.; et al. Bright X-ray Flares in Gamma-ray Burst Afterglows. Science 2005, 309, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, N.R.; Kocevski, D.; Bloom, J.S.; Curtis, J.L. A Complete Catalog of Swift Gamma-ray Burst Spectra and Durations: Demise of a Physical Origin for Pre-Swift High-Energy Correlations. Astrophys. J. 2007, 671, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.A.; Beardmore, A.P.; Page, K.L.; Osborne, J.P.; O’Brien, P.T.; Willingale, R.; Starling, R.L.C.; Burrows, D.N.; Godet, O.; Vetere, L.; et al. Methods and Results of an Automatic Analysis of a Complete Sample of Swift-XRT Observations of GRBs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2009, 397, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, A.D.; Burrows, D.N.; Lazzati, D.; Campana, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Zhang, B.; Mészáros, P.; Page, K.L.; Kennea, J.A.; Romano, P.; et al. The Giant X-ray Flare of GRB 050502B: Evidence for Late-Time Internal Engine Activity. Astrophys. J. 2006, 641, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, A.D.; Morris, D.; Racusin, J.; Chincarini, G.; Moretti, A.; Romano, P.; Burrows, D.N.; Pagani, C.; Stroh, M.; Grupe, D.; et al. The First Survey of X-ray Flares from Gamma-ray Bursts Observed by Swift: Spectral Properties and Energetics. Astrophys. J. 2007, 671, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P.T.; Willingale, R.; Osborne, J.; Goad, M.R.; Page, K.L.; Vaughan, S.; Rol, E.; Beardmore, A.; Godet, O.; Hurkett, C.P.; et al. The Early X-ray Emission from GRBs. Astrophys. J. 2006, 647, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Avanzo, P. Short Gamma-ray Bursts: A Review. J. High Energy Astrophys. 2015, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liang, E.-W.; Tang, Q.-W.; Chen, J.-M.; Xi, S.-Q.; Lü, H.-J.; Gao, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Yi, S.-X.; et al. A Comprehensive Study of Gamma-ray Burst Optical Emission. I. Flares and Early Shallow-decay Component. Astrophys. J. 2012, 758, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margutti, R.; Bernardini, G.; Barniol Duran, R.; Guidorzi, C.; Shen, R.F.; Chincarini, G. On the Average Gamma-ray Burst X-ray Flaring Activity. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2011, 410, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousek, J.A.; Kouveliotou, C.; Grupe, D.; Page, K.L.; Granot, J.; Ramirez-Ruiz, E.; Patel, S.K.; Burrows, D.N.; Mangano, V.; Barthelmy, S.; et al. Evidence for a Canonical Gamma-ray Burst Afterglow Light Curve in the Swift XRT Data. Astrophys. J. 2006, 642, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffini, R.; Wang, Y.; Aimuratov, Y.; Barres de Almeida, U.; Becerra, L.; Bianco, C.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Karlica, M.; Kovacevic, M.; Li, L.; et al. Early X-ray Flares in GRBs. Astrophys. J. 2018, 852, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Fan, Y.Z.; Dyks, J.; Kobayashi, S.; Mészáros, P.; Burrows, D.N.; Nousek, J.A.; Gehrels, N. Physical Processes Shaping Gamma-ray Burst X-ray Afterglow Light Curves: Theoretical Implications from the Swift X-ray Telescope Observations. Astrophys. J. 2006, 642, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Y.; Dai, Z.G. Self-organized Criticality in X-ray Flares of Gamma-ray-Burst Afterglows. Nat. Phys. 2013, 9, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.A.; Starling, R.L.C.; O’Brien, P.T.; Godet, O.; van der Horst, A.J.; Wijers, R.A.M.J. On the nature of late X-ray flares in Swift gamma-ray bursts. Astron. Astrophys. 2008, 487, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.; Tagliaferri, G.; Lazzati, D.; Chincarini, G.; Covino, S.; Page, K.; Romano, P.; Moretti, A.; Cusumano, G.; Mangano, V.; et al. The X-ray Afterglow of the Short Gamma Ray Burst 050724. Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 454, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Margutti, R.; Chincarini, G.; Granot, J.; Guidorzi, C.; Berger, E.; Bernardini, M.G.; Gehrels, N.; Soderberg, A.M.; Stamatikos, M.; Zaninoni, E. X-ray Flare Candidates in Short Gamma-ray Bursts. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2011, 417, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Aimuratov, Y.; Moradi, R.; Peresano, M.; Ruffini, R.; Shakeri, S. Revisiting the Statistics of X-ray Flares in Gamma-ray Bursts. Mem. Soc. Astron. Ital. 2018, 89, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chincarini, G.; Moretti, A.; Romano, P.; Falcone, A.D.; Morris, D.; Racusin, J.; Campana, S.; Covino, S.; Guidorzi, C.; Tagliaferri, G.; et al. The First Survey of X-ray Flares from Gamma-ray Bursts Observed by Swift: Temporal Properties and Morphology. Astrophys. J. 2007, 671, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chincarini, G.; Mao, J.; Margutti, R.; Bernardini, M.G.; Guidorzi, C.; Pasotti, F.; Giannios, D.; Della Valle, M.; Moretti, A.; Romano, P.; et al. Unveiling the Origin of X-ray Flares in Gamma-ray Bursts. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2010, 406, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, E.W.; Zhang, B.; O’Brien, P.T.; Willingale, R.; Angelini, L.; Burrows, D.N.; Campana, S.; Chincarini, G.; Falcone, A.; Gehrels, N.; et al. Testing the Curvature Effect and Internal Origin of Gamma-ray Burst Prompt Emissions and X-ray Flares with Swift Data. Astrophys. J. 2006, 646, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Mao, J. GRB X-ray Flare Properties among Different GRB Subclasses. Astrophys. J. 2019, 884, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.-X.; Du, M.; Liu, T. Statistical Analyses of the Energies of X-ray Plateaus and Flares in Gamma-ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. 2022, 924, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.Z.; Peng, Z.Y.; Chen, J.M.; Yin, Y.; Wang, D.Z.; Wu, H. A Comprehensive Study of Multiflare GRB Spectral Lag. Astrophys. J. 2021, 922, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.-X.; Xie, W.; Ma, S.-B.; Lei, W.-H.; Du, M. Constraining Properties of GRB Central Engines with X-ray Flares. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 507, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioka, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Zhang, B. Variabilities of Gamma-ray Burst Afterglows: Long-acting Engine, Anisotropic Jet, or Many Fluctuating Regions? Astrophys. J. 2005, 631, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.-J.; Gu, W.; Hou, S.-J.; Liu, T.; Lin, D.-B.; Yi, T.; Liang, E.-W.; Lu, J.-F. Central Engine of Late-time X-ray Flares with Internal Origin. Astrophys. J. 2016, 832, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; O’Brien, P.T.; Goad, M.R.; Osborne, J.; Olsson, E.; Page, K. Gamma-ray Bursts: Restarting the Engine. Astrophys. J. 2005, 630, L113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Perna, R.; Armitage, P.J.; Zhang, B. Flares in Long and Short Gamma-ray Bursts: A Common Origin in a Hyperaccreting Accretion Disk. Astrophys. J. 2006, 636, L29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.-X.; Xi, S.-Q.; Yu, H.; Wang, F.Y.; Mu, H.-J.; Lü, L.Z.; Liang, E.-W. Comprehensive Study of the X-ray Flares from Gamma-ray Bursts Observed by Swift. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2016, 224, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, R.; Beniamini, P.; Daigne, F.; Mochkovitch, R. Flares in Gamma-ray Burst X-ray Afterglows as Prompt Emission from Slightly Misaligned Structured Jets. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 513, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.Z.; Wei, D.M. Late Internal-shock Model for Bright X-ray Flares in Gamma-ray Burst Afterglows and GRB 011121. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 2005, 364, L42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, P.; Moretti, A.; Banat, P.L.; Burrows, D.N.; Campana, S.; Chincarini, G.; Covino, S.; Malesani, D.; Tagliaferri, G.; Kobayashi, S.; et al. X-ray Flare in XRF 050406: Evidence for Prolonged Engine Activity. Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 836, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Gao, H.; Lei, W.; Lan, L.; Liu, L. Giant X-ray and Optical Bump in GRBs: Evidence for Fallback Accretion Model. Astrophys. J. 2021, 906, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.-C.; Li, L.; Zou, L.; Wang, X.-G. X-ray Flares Raising upon Magnetar Plateau as an Implication of a Surrounding Disk of Newborn Magnetized Neutron Star. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 21, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.A.; Beardmore, A.P.; Page, K.L.; Tyler, L.G.; Osborne, J.P.; Goad, M.R.; O’Brien, P.T.; Vetere, L.; Racusin, J.; Morris, D.; et al. An online repository of Swift/XRT light curves of γ-ray bursts. Astron. Astrophys. 2007, 469, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, E.-W.; Zhang, B.-B.; Zhang, B. A Comprehensive Analysis of Swift XRT Data. II. Diverse Physical Origins of the Shallow Decay Segment. Astrophys. J. 2007, 670, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.G.; Zhang, B.; Liang, E.W.; Lu, R.J.; Lin, D.B.; Li, J.; Li, L. Gamma-ray burst jet breaks revisited. Astrophys. J. 2018, 859, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, M.G.; Margutti, R.; Chincarini, G.; Guidorzi, C.; Mao, J. Gamma-ray Burst Long Lasting X-ray Flaring Activity. Astron. Astrophys. 2011, 526, A27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, E.; Zhang, B. Model-independent Multivariable Gamma-ray Burst Luminosity Indicator and Its Possible Cosmological Implications. Astrophys. J. 2005, 633, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainotti, M.G.; Del Vecchio, R.; Tarnopolski, M. Gamma-ray Burst Prompt Correlations. Adv. Astron. 2018, 2018, 4969503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, B.E. The Hubble Diagram to Redshift >6 from 69 Gamma-ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. 2007, 660, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.B.; Zhang, C.T.; Zhao, Y.X.; Luo, J.J.; Jiang, L.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Han, X.L.; Terheide, R.K. Spectrum-energy Correlations in GRBs: Update, Reliability, and the Long/Short Dichotomy. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2018, 130, 054202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, C.A.; Roming, P.W.A. Gamma-ray Burst Flares: X-ray Flaring. II. Astrophys. J. 2014, 788, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).