Dark Sector Searches at e+e− Colliders

Abstract

1. Introduction

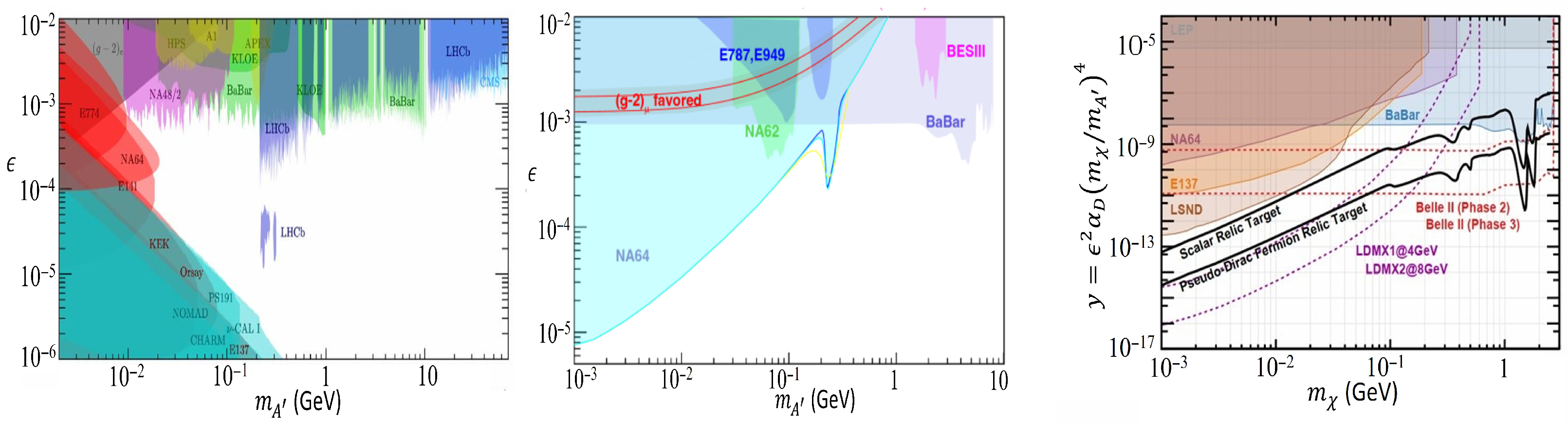

2. Vector Portal

2.1. Massive Dark Photons

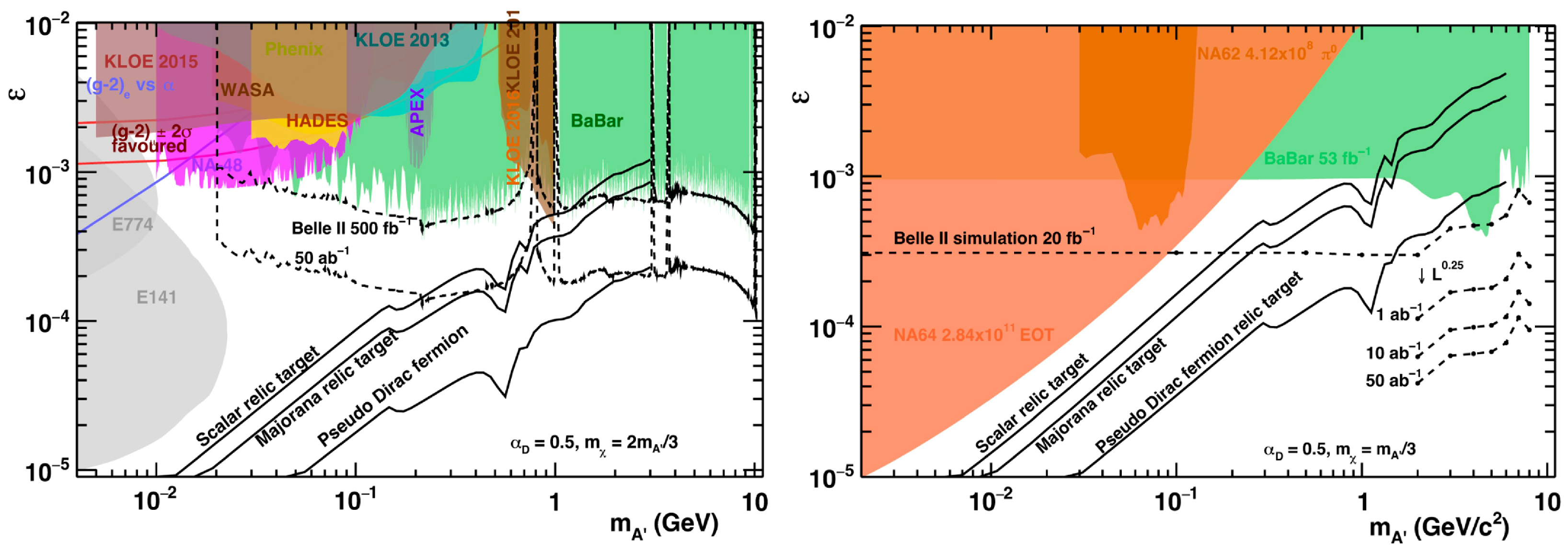

2.1.1. Abelian Dark Photons

2.1.2. Non-Abelian Dark Sector

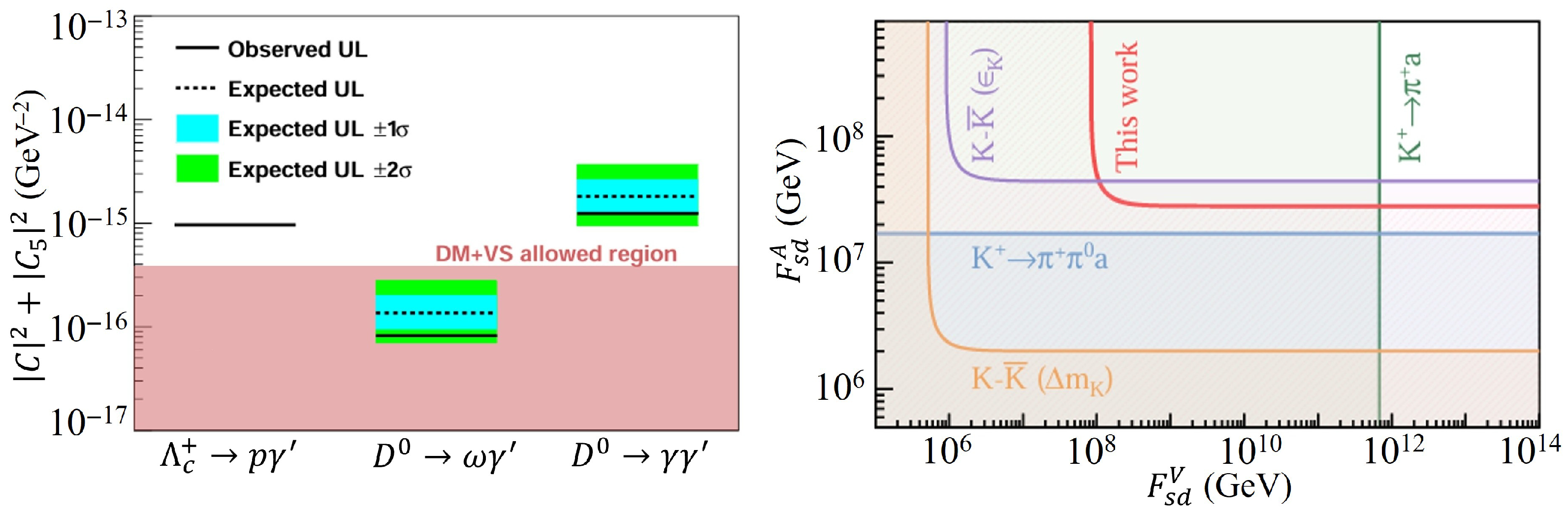

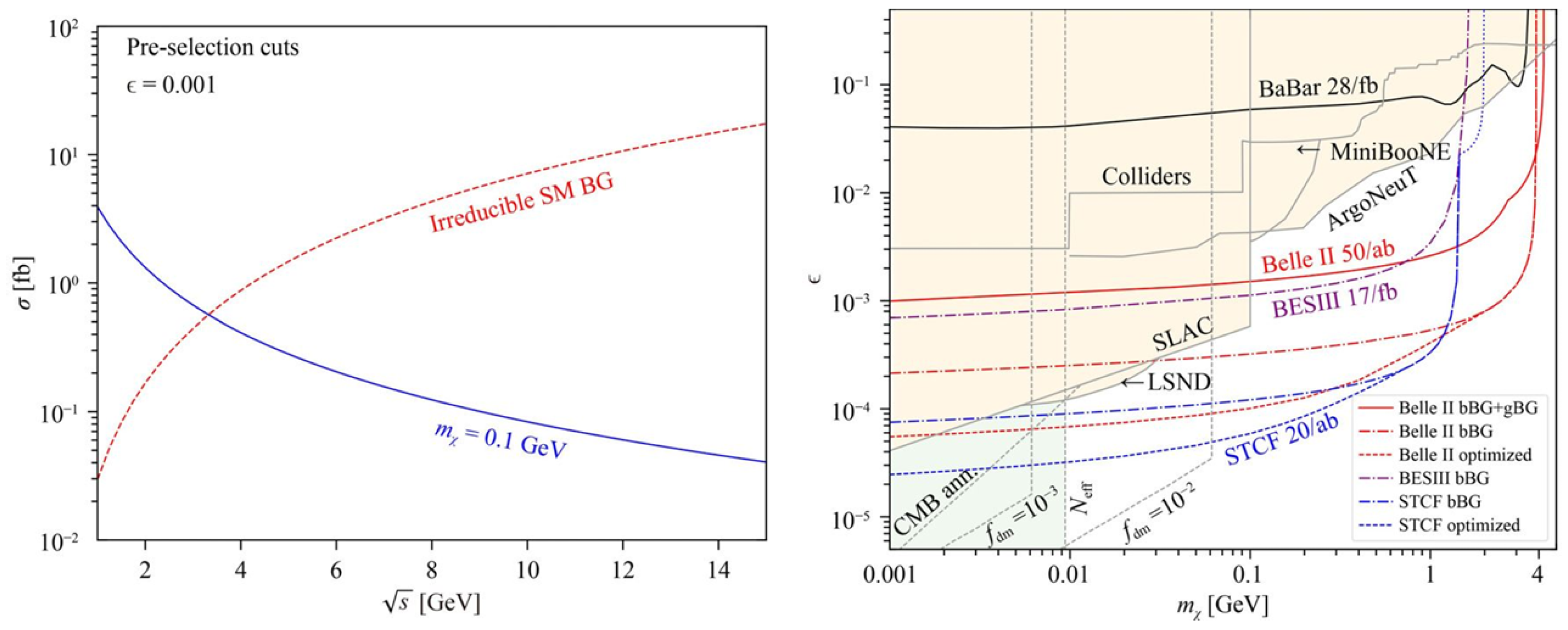

2.2. Massless Dark Photons

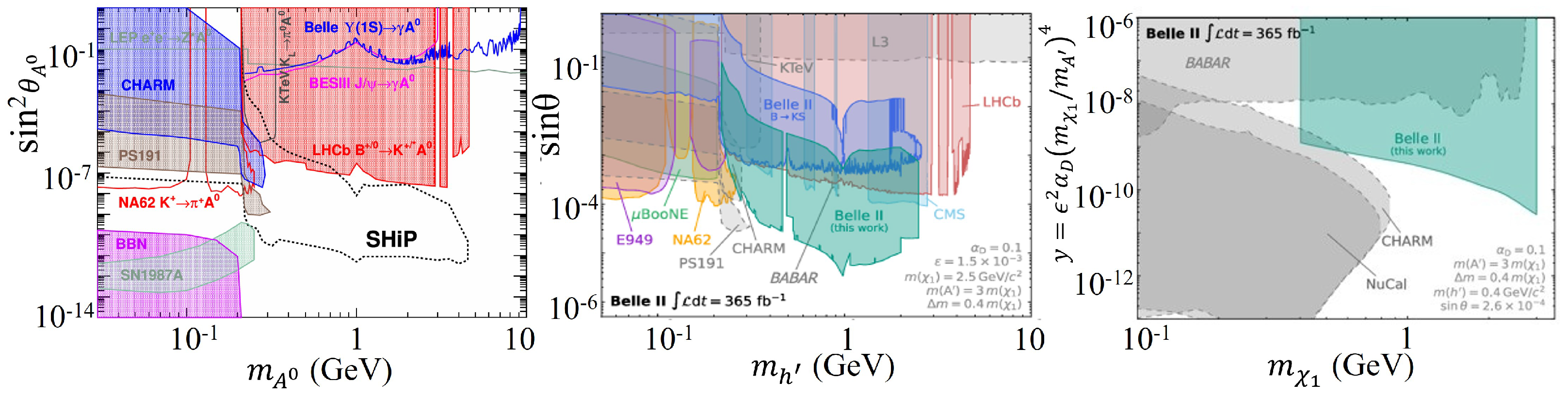

3. Higgs Portal

3.1. Light Higgs Boson

3.2. Dark Higgs Boson

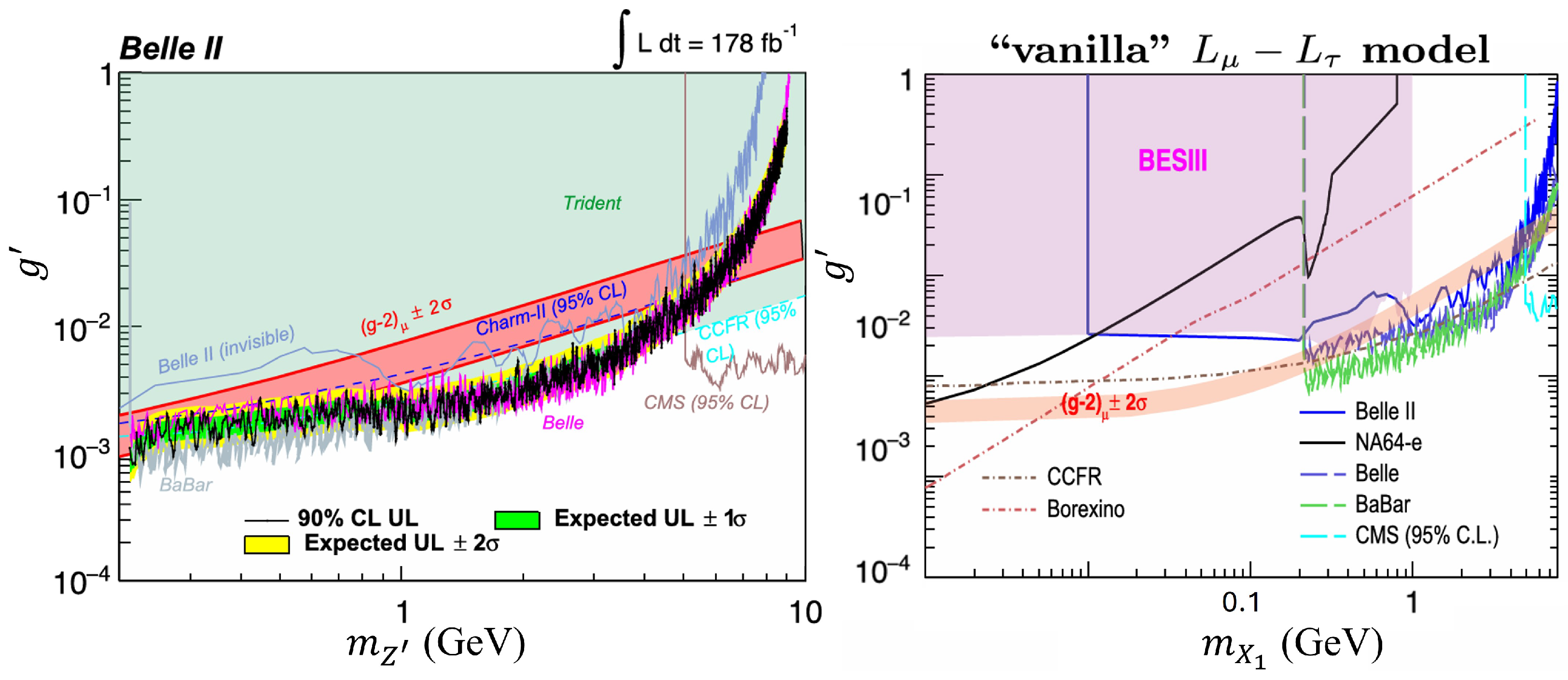

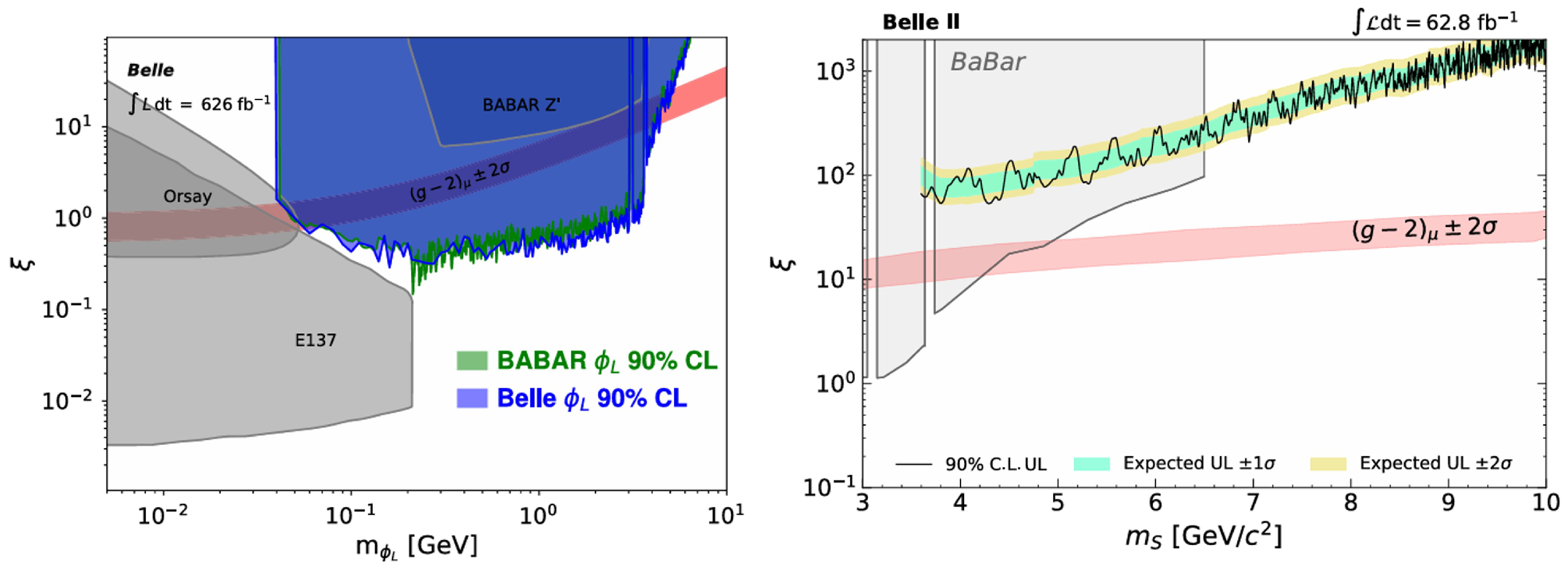

3.3. Muon-Philic Scalar or Vector Bosons

3.4. Search for Dark Baryons

4. Axion Portal

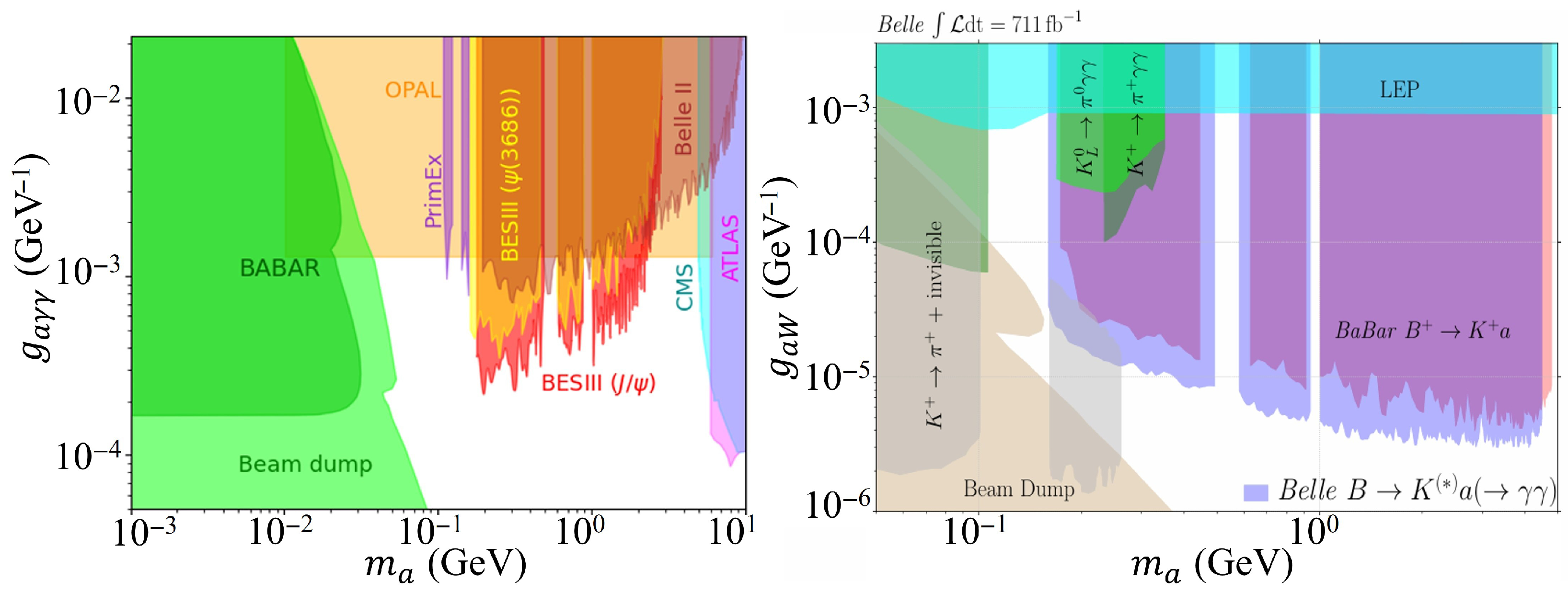

4.1. Coupling to Photon Pairs

4.2. Coupling to W Bosons

4.3. ALP Signature with Invisible Final State

5. Neutrino Portal

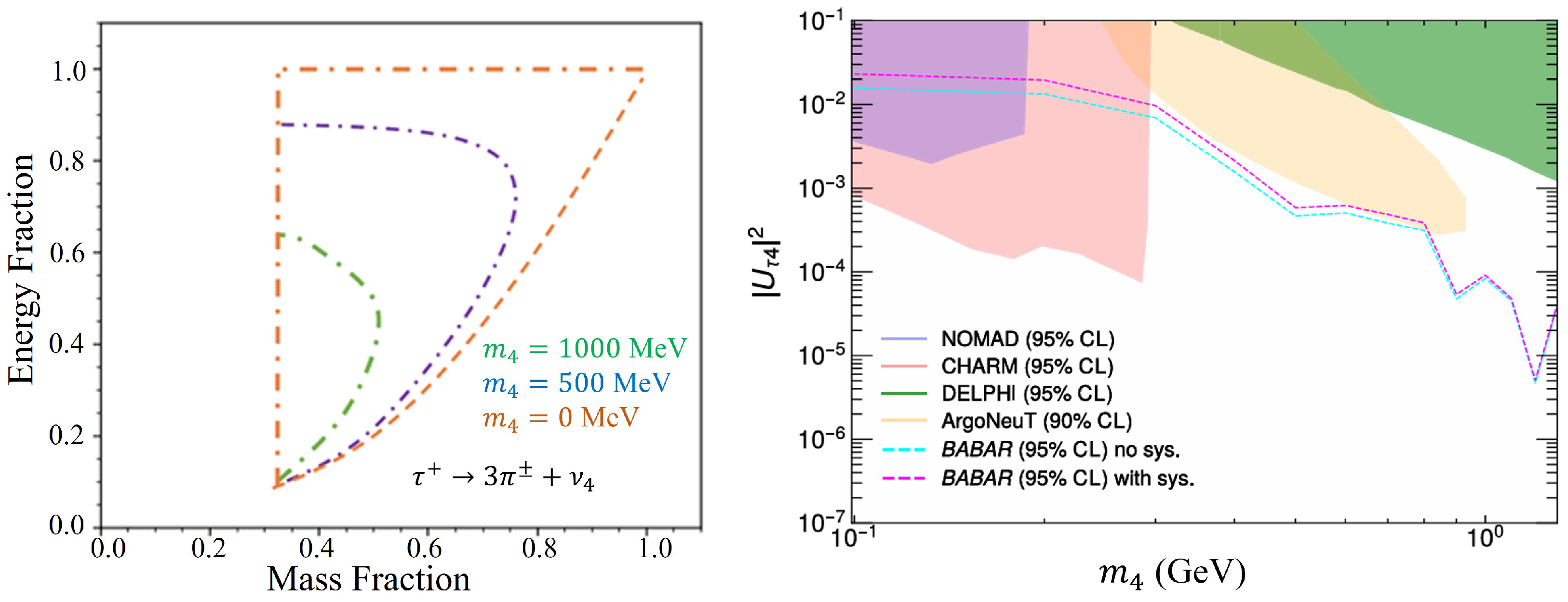

5.1. Search for Heavy Neutral Leptons

5.2. Invisible Decays

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weinberg, S. A model of leptons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 19, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A. Weak and electromagnetic interactions. In Elementary Particle Theory; Svartholm, N., Ed.; Almquist and Wiksells: Stockholm, Sweden, 1969; p. 367. [Google Scholar]

- Glashow, S.L. Partial symmetries of weak interactions. Nucl. Phys. 1961, 22, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glashow, S.L.; Iliopoulos, J.; Maiani, L. Weak interactions with lepton–hadron symmetry. Phys. Rev. D 1970, 2, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P.W. Broken symmetries, masses particles and gauge fields. Phys. Lett. 1964, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P.W. Broken symmetries and the masses of gauge bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1964, 13, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P.W. Spontaneous symmetry breakdown without massless bosons. Phys. Rev. 1966, 145, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englert, F.; Brout, R. Broken symmetry and the mass of gauge vector mesons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1964, 13, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnik, G.S.; Hagen, C.R.; Kibble, T.W.B. Global conservation laws and the massless particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1964, 13, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aad, G. et al. [ATLAS Collaboration] Observation of a new particle in the search for the Standard Model Higgs boson with the ATLAS detector at the LHC. Phys. Lett. B 2012, 716, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatrchyan, S. et al. [CMS Collaboration] Observation of a new boson at a mass of 125 GeV with the CMS experiment at the LHC. Phys. Lett. B 2012, 716, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Baryon- and lepton-nonconserving processes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1979, 43, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospelov, M. Secluded U(1) below the weak scale. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 80, 095002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, A.B. Nobel Lecture: The Sudbury Neutrino Observatory: Observation of flavor change for solar neutrinos. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 030502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajita, T. Nobel Lecture: Discovery of atmospheric neutrino oscillations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 030501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofue, Y.; Rubin, V. Rotation curves of spiral galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2001, 39, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriani, O.; Barbarino, G.C.; Bazilevskaya, G.A.; Bellotti, R.; Boezio, M.; Bogomolov, E.A.; Bonechi, L.; Bongi, M.; Bonvicini, V.; Bottai, S.; et al. An anomalous positron abundance in cosmic rays with energies 1.5–100 GeV. Nature 2009, 458, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, M. et al. [AMS Collaboration] First result from the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer on the International Space Station: Precision measurement of the positron fraction in primary cosmic rays of 0.5–350 GeV. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 141102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Adams, J.H.; Ahn, H.S.; Bashindzhagyan, G.L.; Christl, M.; Ganel, O.; Guzik, T.G.; Isbert, J.; Kim, K.C.; Kuznetsov, E.N.; et al. An excess of cosmic ray electrons at energies of 300–800 GeV. Nature 2008, 456, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M. et al. [Fermi LAT Collaboration] Measurement of separate cosmic-ray electron and positron spectra with the Fermi Large Area Telescope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 011103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghanim, N. et al. [Planck Collaboration] Planck 2018 results. VI Cosmological paramaters. Astron. Atstrophys. 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, S. et al. [Particle Data Group] The review of particle physics (2025), 2025 update. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 030001. [Google Scholar]

- Elor, G.; Escudero, M.; Nelson, A. Baryogenesis and dark matter from B mesons. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 99, 035031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Álvarez, G.; Elor, G.; Escudero, M. Collider signals of baryogenesis and dark matter from B mesons: A roadmap to discovery. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, 035028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.Y.; Tandean, J. Low-energy probes of light pseudoscalars coupled to gluons. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 101, 035044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicoli, M.; Conlon, J.P.; Quevedo, F. Dark radiation in LARGE volume models. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 043520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciapaglia, G.; Deandrea, A.; Isnard, W. Hidden supersymmetric dark sectors. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, 015024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdom, B. Two U(1)’s and epsilon charge shifts. Phys. Lett. B 1986, 166, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglieri, M.; Belloni, A.; Chou, A.; Cushman, P.; Echenard, B.; Essig, R.; Estrada, J.; Feng, J.L.; Flaugher, B.; Fox, P.J.; et al. US Cosmic Visions: New ideas in dark matter 2017: Community report. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.04591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essig, R.; Jaros, J.A.; Wester, W.; Adrian, P.H.; Andreas, S.; Averett, T.; Baker, O.; Batell, B.; Battaglieri, M.; Beacham, J.; et al. Dark sectors and new, light, weakly-coupled particles. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1311.0029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, B. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] The BaBar detector. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 2002, 479, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, E. et al. [Belle II Collaboration] The Belle II physics book. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2019, 2019, 123C01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Future physics programme of BESIII. Chin. Phys. C 2020, 44, 040001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.G.D.; The CEPC Study Group. CEPC conceptual design report: Volume 2—Physics and detector. arxiv 2018, arXiv:1811.10545. [Google Scholar]

- Benedikt, M.; Zimmermann, F.; Auchmann, B.; Bartmann, W.; Burnet, J.P.; Carli, C.; Chancé, A.; Craievich, P.; Giovannozzi, M.; Grojean, C.; et al. Future Circular Collider Feasibility Study Report. Eur. Phys. J. C 2025, 85, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achasov, M.; Ai, X.C.; An, L.P.; Aliberti, R.; An, Q.; Bai, X.Z.; Bai, Y.; Bakina, O.; Barnyakov, A.; Blinov, V.; et al. STCF conceptual design report: Volume 1—Physics and detector. Front. Phys. 2024, 19, 14701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkani-Hamed, N.; Finkbeiner, D.P.; Slatyer, T.R.; Weiner, N. A theory of dark matter. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 79, 015014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrescu, B.A. Massless gauge bosons other than the photon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 151802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.X.; He, M.; He, X.G.; Li, G. Scrutinizing a massless dark photon: Basis independence. Nucl. Phys. B 2020, 953, 114968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruegg, H.; Ruiz-Altaba, M. The Stueckelberg field. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2004, 19, 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, J.M.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, R. Unraveling dark Higgs mechanism via dark photon production at an e+e− collider. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.20208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranchi, G.; Pospelov, M.; Schuster, P. The search for feebly interacting particles. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2021, 71, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batell, B.; Pospelov, M.; Ritz, A. Probing a secluded U(1) at B factories. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 79, 115008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essig, R.; Schuster, P.; Toro, N. Probing dark forces and light hidden sectors at low-energy e+e− colliders. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 80, 015003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Weiner, N.; Xue, W. Signals of a light dark force in the galactic center. J. High Energy Phys. 2015, 08, 050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina Gil, E. et al. [NA62 Collaboration] Search for π0 decays to invisible particles. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 02, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamyan, S. et al. [APEX Collaboration] Search for a New Gauge Boson in Electron-Nucleus Fixed-Target Scattering by the APEX Experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 191804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, H. et al. [A1 Collaboration] Search at the Mainz Microtron for Light Massive Gauge Bosons Relevant for the Muon g-2 Anomaly. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 221802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, H. et al. [A1 Collaboration] Search for Light Gauge Bosons of the Dark Sector at the Mainz Microtron. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 251802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.P. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for a dark photon in e+e− collisions at BaBar. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 201801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Measurement of B(J/ψ → η′e+e−) and search for a dark photon. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 99, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Study of the Dalitz decay J/ψ → e+e−η. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 99, 012006, Erratum in Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, 099901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Dark photon search in the mass range between 1.5 and 3.4 GeV/c2. Phys. Lett. B 2017, 774, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasi, A. et al. [KLOE-2 Collaboration] Limit on the production of a new vector boson in e+e− → Uγ, U → π+π− with the KLOE experiment. Phys. Lett. B 2016, 757, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batley, J.R. et al. [NA48 Collaboration] Search for the dark photon in π0 decays. Phys. Lett. B 2015, 746, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaij, R. et al. [LHCb Collaboration] Search for A′ → μ+μ− decays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 041801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, Y.M. et al. [NA64 Collaboration] Search for Light Dark Matter with NA64 at CERN. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 161801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.P. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for invisible decays of a dark photon produced in e+e− collisions at BaBar. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 131804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for invisible decays of a dark photon using e+e− annihilation data at BESIII. Phys. Lett. B 2023, 839, 137785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, E.; Krnjaic, G.; Shuve, B. Discovering inelastic thermal-relic dark matter at colliders. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 063523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, E.; Krnjaic, G.; Schustera, P.; Toro, N. Analyzing the Discovery Potential for Light Dark Matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 251301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, B. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for a Narrow Resonance in e+e- to Four Lepton Final States. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0908.2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for a massless particle beyond the Standard Model in the Σ0 → p + invisible decays. Phys. Lett. B 2024, 852, 138614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for massless dark photons in → pγ′ decay. Phys. Rev. D 2022, 106, 072008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for a massless dark photon in c → uγ decays. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, L011103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrusaitis, R.M. et al. [MARK-III Collaboration] Direct measurement of charmed-D-meson hadronic branching fractions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 56, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, A.; Kolda, C.; Puente, A.D. Solving the little hierarchy problem with a light singlet and supersymmetric mass terms. Phys. Lett. B 2012, 710, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maniatis, M. The next-to-minimal supersymmetric extension of the Standard Model. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2010, 25, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, F. Decays of Heavy Vector Mesons into Higgs Particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1977, 39, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermisek, R.; Gunion, J.F.; McElrath, B. Probing next-to-minimal-supersymmetric models with minimal fine tuning by searching for decays of the Υ to a light CP-odd Higgs boson. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 76, 051105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for a CP-odd light Higgs boson in J/ψ → γA0. Phys. Rev. D 2022, 105, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.P. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for di-muon decays of a low-mass Higgs boson in radiative decays of the Υ(1S). Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 031102(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S. et al. [Belle Collaboration] Search for a Light Higgs Boson in Single-Photon Decays of Υ(1S) Using Υ(2S) → π+π−Υ(1S) Tagging Method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 128, 081804. [Google Scholar]

- Kolomensky, Y. Searches for Light Higgs Bosons at BaBar. ICHEP 2012 Proceedings. Available online: https://indico.cern.ch/event/181298/contributions/309553/attachments/243619/340902/ichep12$_$kolomensky.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2012).

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for a light exotic particle in J/ψ radiative decays. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 85, 092012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for a light CP-odd Higgs boson in radiative decays of J/ψ. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 052005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for the decays J/ψ → γ + invisible. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 101, 112005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, I. et al. [Belle II Collaboration] Search for a dark Higgs boson in produced in association with inelastic dark matter at the Belle II experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 135, 131801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.P. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for Low-Mass Dark-Sector Higgs Bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 211801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaegle, I. et al. [Belle Collaboration] Search for the Dark Photon and the Dark Higgs Boson at Belle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 211801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudinen, F. et al. [Belle II Collaboration] Search for a dark photon and an invisible dark Higgs boson in μ+μ− and missing energy final states with the Belle II experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 071804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasi, A. et al. [KLOE-2 Collaboration] Search for dark Higgsstrahlung in e+e− → μ+μ− and missing energy events with the KLOE experiment. Phys. Lett. B 2015, 747, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, R.; Aoyama, T.; Balzani, E.; Bashir, A.; Benton, G.; Bijnens, J.; Biloshytskyi, V.; Blum, T.; Boito, D.; Bruno, M.; et al. The anomalous magnetic moment of the muon in the Standard Model: An update. Phys. Rep. 2025, 1143, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, J.; Dyk, D.V.; Langenbruch, C. Flavour anomalies in heavy quark decays. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2021, 120, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foldenauer, P. Light dark matter in a gauged U(1)Lμ−Lτ model. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 99, 035007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.G.; Joshi, G.C.; Lew, H.; Volkas, R.R. New Z′ phenomenology. Phys. Rev. D 1991, 43, R22(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.G.; Joshi, G.C.; Lew, H.; Volkas, R.R. Simplest Z′ model. Phys. Rev. D 1991, 44, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.P. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for a muonic dark force at BaBar. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 94, 011102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirunyan, A.M. et al. [CMS Collaboration] Search for an Lμ − Lτ gauge boson using Z → 4μ events in proton-proton collisions at = 13 TeV. Phys. Lett. B 2019, 792, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czank, T. et al. [Belle Collaboration] Search for Z′ → μ+μ− in the Lμ − Lτ gauge-symmetric model at Belle. Phys. Rev. D 2022, 106, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, I. et al. [Belle II Collaboration] Search for a μ+μ− resonance in four-muon final states at Belle II. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, 112015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for a muon-philic X0 or vector X1 via J/ψ → μ+μ− + invisible decays at BESIII. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, L031102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D. et al. [Belle Collaboration] Search for a dark leptophilic scalar produced in association with τ+τ− pair in e+e− annihilation at center-of-mass energies near 10.58 GeV. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 109, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.P. et al. [BaBaR Collaboration] Search for a dark leptophilic scalar in e+e− collisions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 181801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, I. et al. [Belle II Collaboration] Search for a τ+τ− resonance in e+e− → μ+μ−τ+τ− events with the Belle II experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 121802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogollo, D.; Torres, Y.M.O.; Queiroz, F.S.; Villamizar, Y.; Saa, Z. Search for sub-GeV scalars in e+e− collisions. Eur. Phys. J. C 2025, 85, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakharov, A.D. Violation of CP invariance, C asymmetry, and baryon asymmetry of the universe. JETP Lett. 1967, 6, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Petraki, K.; Volkas, R.R. Review of asymmetric dark matter. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2013, 28, 1330028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, K.M. Asymmetric dark matter: Theories, signatures, and constraints. Phys. Rep. 2014, 537, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornal, B.; Grinstein, B. Dark matter interpretation of the neutron decay anomaly. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 191801, Erratum in Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 219901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.E.; Xiao, H. Baryogenesis from B meson oscillations. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 100, 075002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.P. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for B mesogenesis at BaBar. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 107, 092001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.P. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for Evidence of Baryogenesis and Dark Matter in B+ → ψD + p decays at BaBar. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 201801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.P. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for baryogenesis and dark matter in B+ → + invisible decays. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, L031101. [Google Scholar]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for invisible decays of the Λ baryon. Phys. Rev. D 2022, 105, L071101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for Λ– oscillation in J/ψ → Λ decay. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 052014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for a dark baryon in the Ξ− → π− + invisible decay. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2505.22140. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. A new light boson? Phys. Rev. Lett. 1978, 40, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, F. Problem of strong P and T invariance in the presence of instantons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1978, 40, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, G.C.; Ferreira, P.M.; Lavoura, L.; Rebelo, M.N.; Sher, M.; Silva, J.P. Theory and phenomenology of two-Higgs-doublet models. Phys. Rep. 2012, 516, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringwald, A. Searching for axions and ALPs from string theory. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 485, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for axion-like particles in radiative J/ψ decays. Phys. Lett. B 2023, 838, 137698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Search for diphoton decays of an axionlike particle in radiative J/ψ decays. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 110, L031101.

- Adachi, I. et al. [Belle II Collaboration] Search for an axion-like particle in B → K(*)a( → γγ) decays at Belle. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.01249. [Google Scholar]

- Calibbi, L.; Redigolo, D.; Ziegler, R.; Zupan, J. Looking forward to lepton-flavor-violating ALPs. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 09, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, I. et al. [Belle II Collaboration] Search for Lepton-Flavor-Violating τ Decays to a Lepton and an Invisible Boson at Belle II. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 181803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for Sub-GeV Invisible Particles in Inclusive Decays of J/ψ to ϕ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 135, 151804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for heavy Majorana neutrino in lepton number violating decays of D → Kπe+e+. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 99, 112002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liventsev, D. et al. [Belle Collaboration] Search for heavy neutrinos at Belle. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 071102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liventsev, D. et al. [Belle Collaboration] Search for heavy neutrino in τ decays at Belle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 211802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lees, J.P. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for heavy neutral leptons using tau lepton decays at BaBar. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 107, 052009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, B. et al. [BaBar Collaboration] Search for invisible decays of the Υ(1S). Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 251801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BES Collaboration] Search for the invisible decay of J/ψ in ψ(2S) → π+π−J/ψ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 192001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L. et al. [Belle Collaboration] Search for B0 decays to invisible final states at Belle. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 86, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Álvarez, G.; Abenza, M.E. The first limit on invisible decays of Bs mesons comes from LEP. Eur. Phys. J. C 2024, 84, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for η and η′ invisible decays in J/ψ → ϕη and ϕη′. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BES Collaboration] Search for invisible decays of η and η′ in J/ψ → ϕη and ϕη′. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 202002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.T. et al. [Belle Collaboration] Search for D0 decays to invisible final states at Belle. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 95, 011102. [Google Scholar]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for invisible decays of the ω and ϕ mesons with J/ψ data at BESIII. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://indico.pnp.ustc.edu.cn/event/4580/contributions/32042/attachments/11770/18351/Invisible_decays_of%20light_mesons.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Gninenko, S.N. Search for invisible decays of π0, η, η′, KS, and KL: A probe of new physics and tests using the Bell-Steinberger relation. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 015004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W. Invisible decays of neutral hadrons. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.10746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, R.N. Dark matter and mirror world. Entropy 2024, 26, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, M. et al. [BESIII Collaboration] Search for invisible decays. J. High Energy Phys. 2025, 05, 092. [Google Scholar]

- Hearty, C.; Pachal, K.; Aitken, B.; Curtin, D.; Diamond, M.; Grewal, J.S.; Hallman, Z.; Miller, C.; Owh, G.; Ren, R.; et al. Accelerator-based dark matter searches. Can. J. Phys. 2025, 103, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, M.J.; Ferber, T.; Hearty, C.; Kahlhoefer, F.; Hoberg, K.S. Revised constraints and Belle II sensitivity for visible and invisible axion-like particles. J. High Energy Phys. 2017, 12, 094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Hearty, C.; Williams, M. Searches for dark photons at Accelerators. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part Sci. 2021, 71, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerr, M.; Ferber, T.; Hearty, C.; Kahlhoefer, F.; Hoberg, K.S.; Tunney, P. Invisible and displaced dark matter signatures at Belle II. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 02, 039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Prasad, V. Dark Sector Searches at e+e− Colliders. Universe 2026, 12, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010020

Prasad V. Dark Sector Searches at e+e− Colliders. Universe. 2026; 12(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010020

Chicago/Turabian StylePrasad, Vindhyawasini. 2026. "Dark Sector Searches at e+e− Colliders" Universe 12, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010020

APA StylePrasad, V. (2026). Dark Sector Searches at e+e− Colliders. Universe, 12(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010020