Abstract

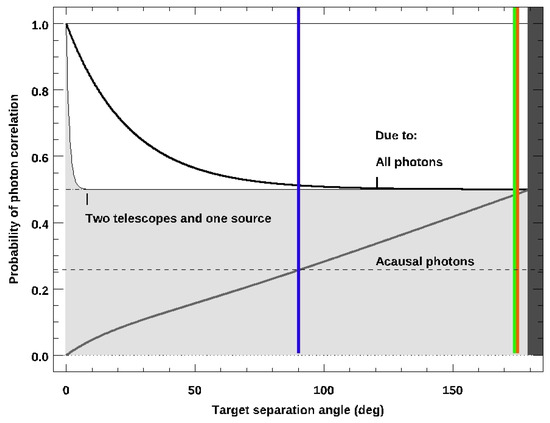

Viewing high-redshift sources at near-opposite directions on the sky can ensure, using light-travel-time arguments, acausality between their emitted photons. One utility would be true random-number generation through sensing these via two independent telescopes that each flip a switch based on the latest-arrived colours; for example, to autonomously control a quantum-mechanical (QM) experiment. Although demonstrated with distant quasars, those were not fully acausal pairs, which are restricted when simultaneously viewed from the ground at any single observatory. In optical light, such faint sources also require a large telescope aperture to avoid sampling assumptions when imaged at fast camera framerates: unsensed intrinsic correlations between them or equivalently correlated noise may ruin the expectation of pure randomness. One such case that could spoil a QM test is considered. Based on that, the allowed geometries and instrumental limits are modelled for any two ground-based sites, and their data are simulated. For comparison, an analysis of photometry from the Gemini twin 8 m telescopes is presented using the archival data of well-separated bright stars obtained with the instruments ‘Alopeke (on Gemini North in Hawai’i) and Zorro (on Gemini-South in Chile) simultaneously in two bands (centred at and ) with 17 Hz framerate. No flux correlation is found; these results were used to calibrate an analytic model predicting where a search with a signal-to-noise over 50 at 50 Hz can be made using the same instrumentation. Finally, the software PDQ (Predict Different Quasars) is presented, which searches a large catalogue of known quasars, reporting those with a brightness and visibility suitable to verify acausal, uncorrelated photons at these limits.

1. Introduction

That quantum mechanics (QM) must be incomplete, allowing “spooky” outcomes requiring either super-luminal signals or hidden variables—essentially, unsensed influences on the outcome—was posited by Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen [1]. Bell showed, however, that correlations in a QM experiment could allow for tests to obtain evidence against such hidden-variable theories [2]. Repeated Bell-theorem tests have since routinely found that QM is correct through tightly and simultaneously restricting the necessary conditions on measurements (e.g., [3] and references therein), including the influence of experimenter interaction: the so-called “freedom-of-choice” loophole. One route to this has been to set experimental parameters via photons from astronomical sources [4,5], requiring that interference in such settings is somehow orchestrated between distant sources and the Earth-based observer. Proof-of-concept tests using stars within the Milky Way were achieved [6] forcing any collusion in the outcome back hundreds of years. Additionally, the extension to quasars [7,8,9] pushed this to , combining high redshift z with large angular separation on the sky to increasingly place these outside each others’ light cone; where apart would be complete if both sources have [4]. Smaller separations could be compensated by higher source redshifts, although possibly at the cost of the objects being fainter. The motivation to reach this limit is to achieve independence from the settings triggered via those photons, which are unspoiled by communication. However, that is true only if no correlated errors are introduced via scattered photons from the sky, or otherwise via optical inefficiencies and detector electronics, which corrupt their unsychronized fluxes just prior to detection.

To outline the timescales and error limits that need to be met so that the flux of two quasars is truly acausal and measured as sufficiently uncorrelated, consider the one quasar-based Bell test undertaken so far by Rauch et al. [9]. This followed the methodology of Clauser [10], where an entangled pair of photons emitted from a central source are split between two optical arms and their polarizations are detected at receivers. While those entangled photons were in flight, a switching mechanism at each receiver (also co-located with a telescope) selected between two polarization measurements at pre-fixed relative angles, which were chosen to test the maximum potentially observable difference from QM. This switch was set using the colour of the most recently detected quasar photon: a dichroic splitting flux into two broad colour-bands that did not systematically favour either selection. Bright pairs were viewed separately via two 4 m class telescopes from Observatorio del Roque de los Muchachos on La Palma. One quasar pair was separated by on the sky, with and ; another pair was apart with and . Both quasar fluxes (in ) were brighter than the sky background () and a relative polarization measurement was retained only if both quasar photons arrived within microseconds while the entangled photons were in flight. Fair sampling was assumed; that is, thousands of individual trials were obtained non-continuously (achieving a duty cycle up to several seconds apart; the cadence ) during runs lasted 12 and 17 min and so each quasar-photon sample initiating a switch was considered independent, providing no information that could be exploited to predict the next outcome. This meant that at least one in four correlated switching photons were needed to spoil a Bell test, although possibly as little as 14% is enough [11]. Thw analysis showed that neither the colours of the two quasars nor the background noise hindering their detection (i.e., sky-line fluctuations) were correlated among all trials beyond such measurement-error margins.

Optical or near-infrared (NIR) photometry from any single observatory site hinders a QM-test experimental cadence fast enough to remove the fair-sampling assumption for quasars separated by more than where both have . That is due to the two switching telescopes being, at most, kilometers apart, where is in light travel time, i.e., ∼1 MHz rates. However, a typical quasar has a V-band AB-magnitude of about 20 [12] (roughly the same as the dark sky in ) and similar to 1 micron, which, even for an idealized unobstructed 8 m class telescope with perfect throughput (that splits light into two bandpasses), provides a fluence of less than 18 photons in 10 milliseconds under photometric skies at low elevation when operating at a reasonable observing limit of extinction. Despite a good vision of , this would be against a background of below 2 photons, providing an individual exposure signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of over 10 for each quasar. A sampling cadence of would then be the fastest possible means of retaining a sufficient SNR against the sky background flux for the simultaneous two-band photometry of both quasars while reaching a colour-discrimination per sample of uncertainty, and this would work less well for realistic efficiencies. Finding brighter sources or choosing broader passbands could double the SNR, but this would still be four orders of magnitude slower than the telescope-to-telescope signalling rate. That is a problem because millisecond and longer-lasting oscillatory correlations might naturally arise due to the self-similar Kolmogorov scaling of wavefront aberrations, particularly at smaller telescope angular separations, without any ability to discriminate those against fluctuations due to the sources themselves. Adaptive optics (AO) may help, as such systems routinely sense these phase errors at kilohertz rates at wavelengths of near and utilize their index-of-refraction behaviour to manipulate them longward of or so into the NIR: these photons can be redirected with a fast-moving optic. This results in a sharpened image that may be diffraction-limited at , more readily improving photometry by a factor of 2 or so and leaving an uncorrected fraction at lower frequencies (e.g., [13]). However, even with this assistance, the practical sampling cadence is too slow to exclude all higher-frequency intrinsic correlations (or correlated noise) that can provide a prediction for the next experimental outcome, whether the quasar switching-photon sample of either band at each telescope falls inside the seeing disk or not.

Instead, telescopes situated at two well-separated sites could rule out such correlations, because then both high-angular separations of up to (and, therefore, known acausal sources) and fluctuations in seeing (and, therefore, source versus background flux per sample) need only be monitored at timescales closer to the Earth light-crossing time, roughly less than or at , to measure and exclude any influence (or temporally correlated errors) in their simultaneous photometry. Interestingly, no such case has been reported so far, and no monitoring campaign simultaneously viewing quasars outside each observatory’s horizon seems to have been undertaken, at any wavelength. For -rays and X-rays, and through to far-ultraviolet rays, this would require a specially designed spaceborne mission, which is not yet planned. This difficulty extends to the radio as, when on the ground, dish elevations must remain above the horizon regardless of Sun position. From Earth’s nightside, optical/NIR telescopes are restricted to separations below two airmasses, incurring about twice the zenith extinction and instrumental zeropoint error for each. Even so, non-AO corrected photometry to within 10% accuracy can still be achieved for these sources. Therefore, the goal of achieving simultaneous photometry at 10 Hz for 100 Hz-framerates of acausal quasar pairs with two independent telescopes may be within reach. What should they see?

The first step to answering that is to define a plausible correlated signal to look for, sufficient to spoil a Bell test, in order to characterize what might be detected within the observational noise—at best, within just the instrumental zeropoints—without assuming instrinsic randomness. Second is the characterization of instrumental limits, and demonstration of simultaneous high-framerate optical photometry from two widely separated sites, setting a benchmark. An active galactic nucleus (AGN) need not be the source. So, at least one useful dataset to probe is already available at Gemini, providing data on Maunakea in Hawaii ( N, W, 4213 m) and Cerro Pachon in Chile ( S, W, 2722 m); when each viewing a target near zenith, these data place those apart on the sky. These twin 8.1 m telescopes have operated as near-identical high-framerate (up to ) optical imagers for several years, as ‘Alopeke and Zorro, and their public archive contains some serendipitous, simultaneous observations of bright stars. Although such data do not constitute a QM experiment, they do provide a baseline when devising a future one: at over 10,600 km apart, no collusion is possible on timescales less than this distance divided by the speed of light or , which, in the restframe at , corresponds to .

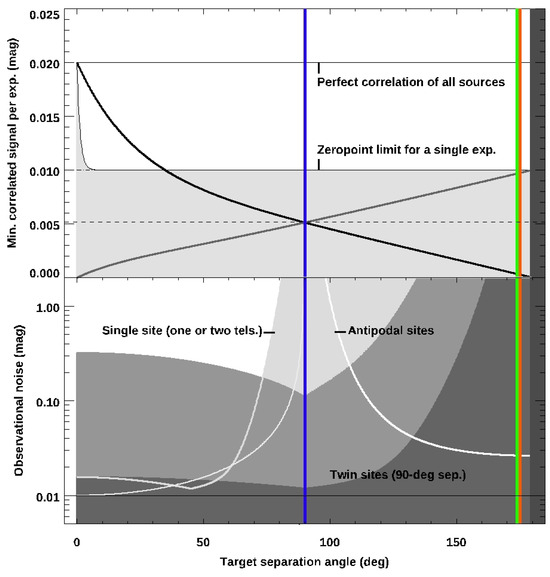

The next section describes how the geometry of an experiment allowing for the simultaneous photometry of quasar pairs restricts their best relative SNR, if not due simply to correlated errors, AGN-physics can, at the short timescales relevant here, cause such an intrinsic signal to arise. Simulated observational data are generated. A method of sensing the correlation of flux differences will be described for conditions where point-source photometry has sufficient sampling and sensitivity to reach the zeropoints of two identical instruments within about 2% error. This is then extended to any two observation sites on Earth, including paired antipodal ones, and to fainter pairs appropriate for quasars. Following that, the available Gemini dataset is described: four observational pairs of bright stars with separations up to nearly in the sky and at a peak SNR consistent with the model, providing a calibration at sampling rate towards tests with quasars. Software is described that can finds these for follow-up tests at a framerate over . The discussion concludes with a short list of potential quasar-pairs and their upcoming best nights for observation via simultaneous Gemini photometry with ‘Alopeke/Zorro, which reaches the necessary photometric accuracy to prove suitability in a Bell test.

3. Observations

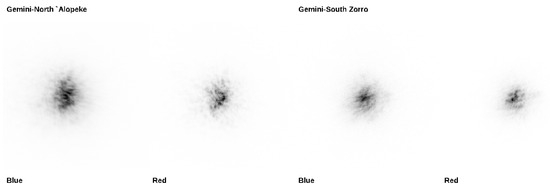

Gemini provides a suitable dataset for the demonstration of the search, as it operates identical high-framerate (up to ), low-noise, 1024 by 1024, Electron-Multiplying, Charge-Coupled Device (EMCCD) optical imagers ‘Alopeke and Zorro: dual-channel photometers, splitting flux into a blue (centred at , wide) and red (, ) passbands [17]. Installed in 2018, these are normally utilized (independently) in speckle interferometry, although the recorded limited-vision raw images are uncorrected. A typical set of four images is shown in Figure 7. The observations made using either instrument are normally a long sequence of 1000 exposures; the fast readout electronics allow for nearly integrations to be achieved, each timestamped to within microseconds. The absolute accuracy of the sequences is better than . The public archive was searched for serendipitous, simultaneous observations when both ‘Alopeke and Zorro obtained sequences starting within 5 s of each other. Four cases of three sets of observations of two bright stars (a total of twelve observations, listed by start time in Table 2) were found that met these timing restrictions, with the assurance that a loss of no more than 10% of the combined dataset was obtained. Equivalently, each has more than a 90% overlapping period of simultaneous observations.

Figure 7.

Sample images from the Gemini ‘Alopoke/Zorro dataset with blue and red filters. These are the simultaneous integrations of two bright stars, one from the North and one from the South.

Table 2.

Stars imaged simultaneously for three minutes, each with Gemini ‘Alopeke and Zorro.

4. Analysis and Results

Aperture photometry was carried out on all images; a 5 arcsec synthetic aperture was applied, with a 1 arcsec-wide annulus surrounding it to obtain a sky estimate. A custom IDL code was written to perform this, which also generated the statistics for the combined data over the full 60 s of each sequence. The difference in flux for blue-red is the colour; this was converted to an AB magnitude via the published bandpasses and throughputs for the instruments, with close to 90% for blue and 70% for red.

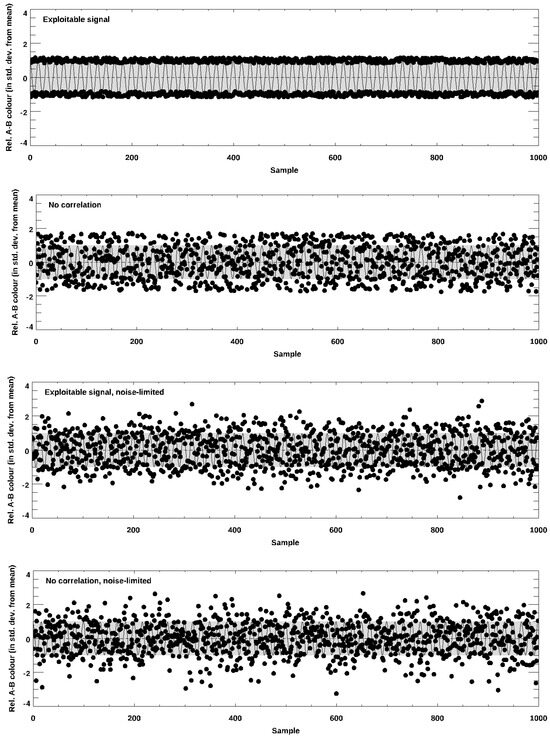

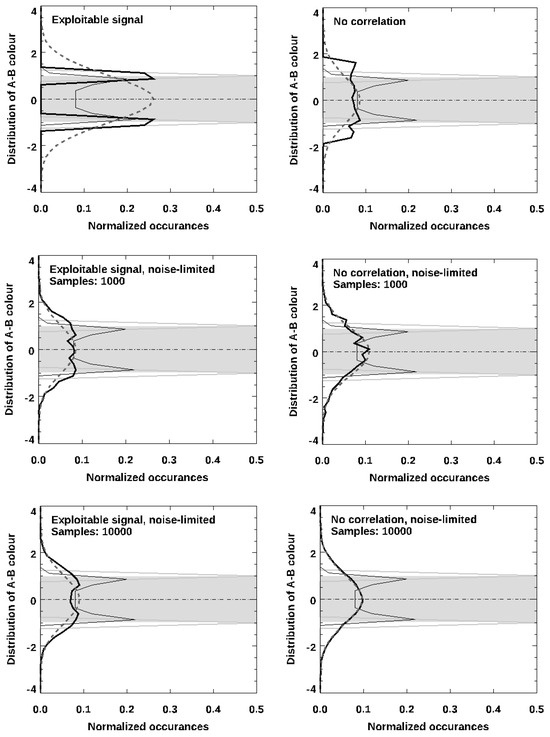

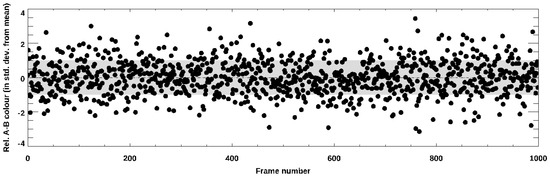

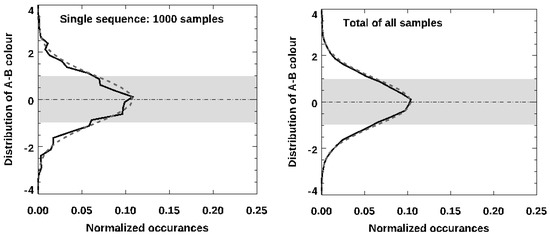

This photometry was then converted to a difference relative to the standard deviation of the colour for the whole sequence; hence, it was reported as the std. dev. from the mean, as defined in Section 2.1. The results for one sequence are shown in Figure 8; that is, the A-B colour of the two stars in each frame. The chosen convention was that the object labelled A was that observed with ‘Alopeke and object B was that observed with Zorro. A linear fit for colour over the sequence was also subtracted to ensure that no trend was due to airmass changes, although this was found to have a negligible effect, well under 1%. The grey band in Figure 8 delineates 1 std. dev. above and below the slope-corrected mean. The resulting distributions are shown in Figure 9; both show one individual sequence of 60 s (left shows those from the same sequence as shown in Figure 8), and the combination of all 12 available observations is shown on the right; both of these are indistinguishable from the Gaussian (dashed curve) normalized to the same peak.

Figure 8.

Sample A-B colour photometry for one 1000-sample sequence of ‘Alopeke/Zorro data. This is the first sequence from the data of 9 October 2019.

Figure 9.

Colour distributions for ‘Alopeke/Zorro data; for the 1000-frame sequence in Figure 8 (left panel) and for all 12 available archival observations (right panel) for a total of 12,000 samples.

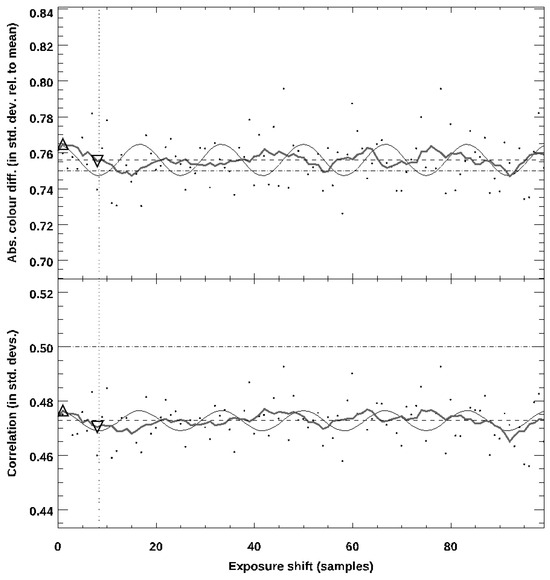

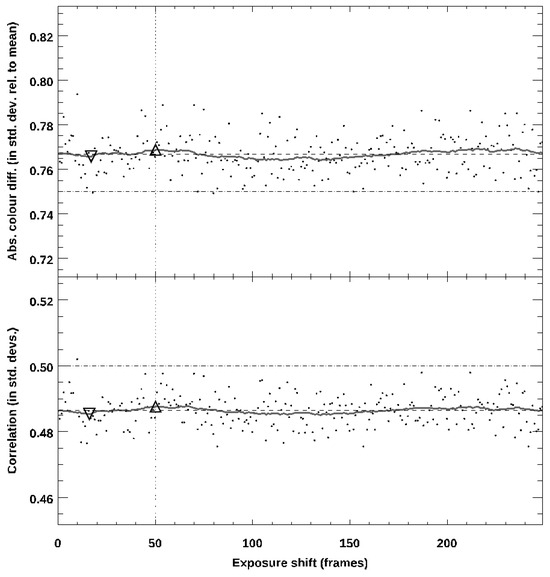

An auto-correlation analysis identical to that described in Section 2.2 was also carried out, which confirms the random nature of the observed colours, as shown in Figure 10. Shifts of up to 5 s were allowed; the vertical dotted line indicates the time period during which the two local instrument clocks could be out of sync; there is no evidence of an improved correlation within that window. It is perhaps no surprise that the simultaneous colours of these stars are random, but it is still a useful excercise. That is because although these observations were undertaken at 0.06 s cadence, ‘Alopeke/Zorro are capable of 0.01 s exposures—shorter than the telescope-to-telescope light-travel time—as will be shown in the next section, which can allow for a test to be conducted for two quasars, which are both much fainter, but still provide sufficient photons to obtain an image at the highest framerate.

Figure 10.

Auto-correlation of ‘Alopeke/Zorro data in Figure 8. No detectable correlation is seen, allowing for shifts of up to for different start times (Zorro precedes ‘Alopeke) and ensuring the accuracy of the clock.

Finding Quasar Pairs to Complete a True Acausal–Photons Correlations Test

A software tool was developed to predict where pairs of quasars with the potentially observable and exploitable A-B colour signal of Section 2.1 might be found. It incorporates the expected noise limitations imposed at different sites and instrument properties (telescope aperture, framerate, and throughputs), as in Section 2.3, and then reports an SNR for those selected quasar pairs, based on catalogued brightnesses. The code can be set for Gemini (8.1 m apertures, geographic coordinates) and calculates the visibility of sources for the upcoming year and outputs a target list indicating the best night during that time. It can also restrict the allowed sky-offsets from a single object (for example, a calibration star) to be simultaneously visible at both sites on that night. The best time in the night is when both targets are at the lowest combined airmass for both sites, where both sources reach their highest ascension in both the North and South skies. The outputs are the target names for each of the two selected telescope sites, appending A and B with the convention that target A is rising and B is setting on the best night. This program is called PDQ (Predict Different Quasars), written in IDL, and is freely available via GitHub. The target list remains unvetted in this version of the code: neither the brightness of the quasars nor their redshifts are verified. A sample is listed in Table 3. Manual checking with slightly relaxed settings does find some suitable pairs that are bright enough to image with ‘Alopeke/Zorro.

Table 3.

Potential acausal quasar pairs that are visible for over two weeks with Gemini ‘Alopeke and Zorro.

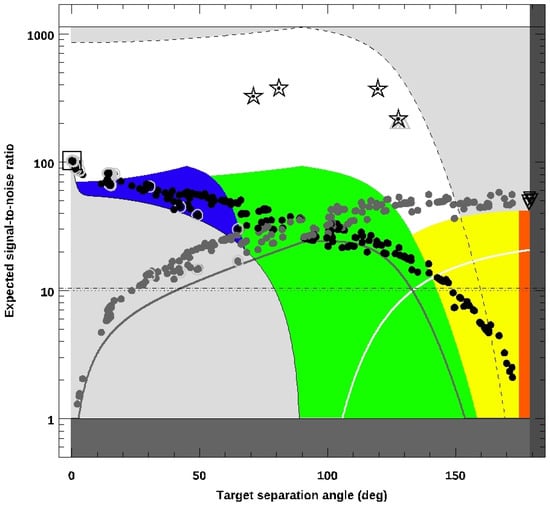

Using the results from Section 4 on bright stars for comparison, the tool’s output is plotted in Figure 11: A-B observed-colour SNR for 3000 samples at 50 Hz. Alopeke/Zorro results are indicated by black-outlined stars; all others show the 18.5 R-mag and brighter quasars selected from the MILLIQUAS sample [12]; either (the mean sample reshift) separated by , or each has a (possibly photometric) redshift of ; those with a separation of are indicated by open down-pointing triangles. At all smaller separation angles, these are indicated by the minimal fraction of acausal photons per sample (dark grey filled circles) and causal (black). Where these would be visible to both telescopes, they are outlined by a grey circle; a black square indicates when it is, in fact, the same source, with zero separation. Coloured and shaded regions indicate the expected model-SNR limits for fair-sampling at other telescope site choices (Equation (2), with ): light grey is a limiting case if a single telescope has a field of view over the whole sky; blue denotes a single site with two telescopes; green indicates two sites with exactly separation on Earth; yellow indicates antipodal sites. There is an upper limit (for separation) from the model at 50 Hz, but the flux matches that of the observed stars (dashed curve).

Figure 11.

Predicted A-B colour SNR for acausal photons (filled grey circles) from quasar pairs with Gemini ‘Alopeke and Zorro, as found with the PDQ software, plotted for instances when objects are visible for at least two weeks; the same is also shown for the causal fraction of photons (filled black circles), where the down-pointing triangles are for , acausal quasar pairs. For comparison, up-pointing triangles are a transitional case at peak SNR photons (but not fully acausal) near separation for 10,000 samples of , quasars; open circles flag those cases that could be observed by either site; an open square indicates both telescopes are observing one source (causal, with the same brightness as the acausal pairs); open stars denote the stellar sources that were previously observed by Gemini with 3000 samples each. The outer grey-shaded boundary shows the model results for fair-sampling (indistinguishable between causal and acausal photons; equation 2 shows ) and -separated sites and sources; sources (green), a single site (blue), and two antipodal sites (yellow) were obtained via the model presented in Section 2. Notice that, on optimal nights, Gemini provides the necessary conditions for viewing fully acausal sources (red), with an SNR similar to that of the antipodal sites.

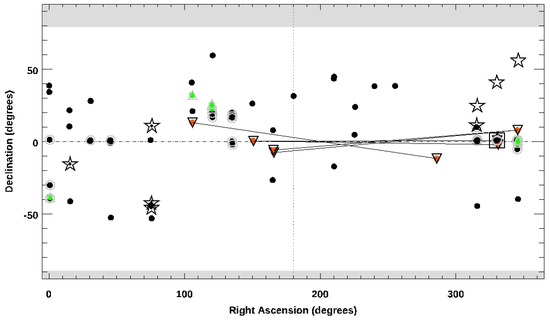

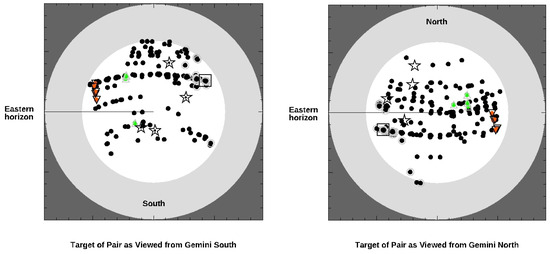

Two further outputs help to visualize the orientation of the potential targets on the sky, and possible scheduling of observations: Figure 12 is a plot of right ascension and a declination of the targets displayed in Figure 11 as being visible in the coming year. Note the East–West alignment of acausal quasar pairs that are separated by (down-pointing tringles, with red filled circles). For comparison, the previously observed stars are shown; a black central dot indicates those viewed from Gemini South. In Figure 13, the polar projections of the visibility of the targets are shown for Gemini South (left) and Gemini North (right); again, it is clear that suitable acasual quasar pairs are visible towards the low eastern horizon (Gemini South) and western sky (Gemini North) simultaneously.

Figure 12.

Source pairs on the sky; symbols are those shown in Figure 11; here, the acausal quasar pairs are connected by a thin black line segmment; the South (B) star of the pair is indicated by a central black dot.

Figure 13.

Same as Figure 12, in polar projection from the zenith, as each is best viewed from either Gemini North or South at the lowest combined airmasses: a preferential East–West alignment is evident.

5. Summary and Conclusions

True random-number generation can be demonstrated via high-framerate photometric observations of quasar pairs that are separated by angles on the sky that make them inaccessible to any single ground-based observatory site. When apart, and each at , their emitted photons are acausal: no signalling between the sources could have spoiled the independence of a Bell-test setting procedure. So far, no such observations have been undertaken, and thus this is not proved. An analysis was carried out that sets boundaries on how observably correlated those two sources might be and the statistical signature of detecting that correlation relative to local noise sources. Simulated data were generated, and then an analytic model was used to compare among telescopes in three potential observing scenarios for any two observatory sites. It was found that two 8 m class telescopes at good sites at over separation on Earth are able, at reasonable observational limits and choices of optical bandpasses, and at high but practical camera framerates of , to to achieve a suitable SNR to overcome the seeing and sky-noise conditions, and therefore to rule out correlated noise ruining observations of suitable quasar pairs in QM tests. Details of the experimental procedures are left for other work.

To demonstrate the observational method and the utility of Gemini for the task, archival observations of four sets of bright star pairs obtained simultaneously (and serendipitously) in two bandpasses with ‘Alopeke/Zorro were presented. These do not meet the required framerate, obtained at only , but the necessary sampling speed is obtainable with this instrumental setup at its highest setting, . This also provides a calibration of the achievable SNR; the described model can extrapolate to fainter quasars observed at that framerate: typical sky conditions at the Gemini sites suggest that acausal 18.5 mag quasars can achieve an SNR of 50 in 3000 samples, ruling out correlations that are sufficient to spoil a QM test lasting minutes. Finally, a tool for finding suitable quasars to carry out such an observation and confirm there is no detectable correlation at the required framerate was presented, with example results obtained after running this PDQ code set for observations with Gemini ‘Alopeke/Zorro. It was found that several potential quasar pairs could be visible in the coming semesters, and so actual observations with Gemini may be considered. In the meantime, that code is freely provided via GitHub for the community, for example, when planning further QM tests.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data discussed herein are freely available via public archives using the links indicated in the text, and their references. The data are also all downloadable from https://github.com/ericsteinbring/PDQ (accessed on 1 April 2025) in formatted data tables, together with the analysis code, written in IDL. In its default settings, that code generates the figures shown here.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments from the anonymous referees, which improved the manuscript. This research used the facilities of the Canadian Astronomy Data Centre operated by the National Research Council of Canada with the support of the Canadian Space Agency. Archival observations employed the High-Resolution Imaging instruments ‘Alopeke and Zorro, funded by the NASA Exoplanet Exploration Program and built at the NASA Ames Research Center by Steve B. Howell, Nic Scott, Elliott P. Horch, and Emmett Quigley. ‘Alopeke and Zorro were mounted on the Gemini North and South telescopes of the international Gemini Observatory, a program of NSF NOIRLab, which is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with the U.S. National Science Foundation on behalf of the Gemini partnership: the U.S. National Science Foundation (United States), National Research Council (Canada), Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (Chile), Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Argentina), Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações (Brazil), and Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (Republic of Korea).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGN | Active Galactic Nucleus |

| AO | Adaptive Optics |

| IDL | Interactive Data Language |

| NIR | Near Infrared |

| QM | Quantum Mechanics |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

References

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? Phys. Rev. 1935, 47, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox. Physics 1964, 1, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, W.; Burchardt, D.; Garthoff, R.; Redeker, K.; Ortegel, N.; Rau, M.; Weinfurter, H. Event-Ready Bell Test Using Entangled Atoms Simultaneously Closing Detection and Locality Loopholes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 010402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, A.S.; Kaiser, D.I.; Gallicchio, J. The Shared Causal Pasts and Futures of Cosmological Events. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 88, 044038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallicchio, J.; Friedman, A.S.; Kaiser, D.I. Testing Bell’s Inequality with Cosmic Photons: Closing the Setting-Independence Loophole. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 110405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handsteiner, J.; Friedman, A.S.; Rauch, D.; Gallicchio, J.; Liu, B.; Hosp, H.; Kofler, J.; Bricher, D.; Fink, M.; Leung, C.; et al. Cosmic Bell Test: Measurement Settings from Milky Way Stars. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 060401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Bai, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, M.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, H.; Shi, X.; et al. Random Number Generation with Cosmic Photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 140402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.; Brown, A.; Nguyen, H.; Friedman, A.S.; Kaiser, D.I.; Gallicchio, J. Astronomical Random Numbers for Quantum Foundations Experiments. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 042120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, D.; Handsteiner, J.; Hochrainer, A.; Gallicchio, J.; Friedman, A.S.; Leung, C.; Liu, B.; Bulla, L.; Ecker, S.; Steinlechner, F.; et al. Cosmic Bell Test Using Random Measurement Settings from High-Redshift Quasars. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 080403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clauser, J.F.; Horne, M.A.; Shimony, A.; Holt, R.A. Proposed Experiment to Test Local Hidden-Variable Theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1969, 23, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.S.; Guth, A.H.; Hall, M.J.W.; Kaiser, D.I.; Gallichio, J. Relaxed Bell Inequalities with Arbitrary Measurement Dependence for Each Observer. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 012121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flesch, E.V. The Million Quasars (Milliquas) Catalogue, V8. Open J. Astrophys. 2023, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbring, E. A Star-Forming Shock Front in Radio Galaxy 4C+ 41.17 Resolved with Laser-Assisted Adaptive Optics Spectroscopy. Astron. J. 2014, 148, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.-Z.; Bai, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, Z. Test of Local Realism into the Past without Detection and Locality Loopholes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 080404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudd, D.; Martini, P.; Zu, Y.; Kochanek, C.; Peterson, B.M.; Kessler, R.; Davis, T.M.; Hoormann, J.K.; King, A.; Lidman, C.; et al. Quasar Accretion Disk Sizes from Continuum Reverberation Mapping from the Dark Energy Survey. Astrophs. J. 2018, 862, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasten, F. A New Table and Approximation Formula for the Relative Optical Air Mass. Arch. Meteorol. Geophys. Bioklimatol. Ser. B 1965, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.J.; Howell, S.B.; Gnilka, C.L.; Stephens, A.W.; Salinas, R.; Matson, R.A.; Furlan, E.; Horch, E.P.; Everett, M.E.; Ciardi, D.R.; et al. Twin High-Resolution, High-Speed Imagers for the Gemini Telescopes: Instrument Description and Science Verification Results. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2021, 8, 716560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).