On the Counter-Rotating Tori and Counter-Rotating Parts of the Kerr Black Hole Shadows

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Spacetime Metric

2.1. Geodesics Equations and Constants of Motion

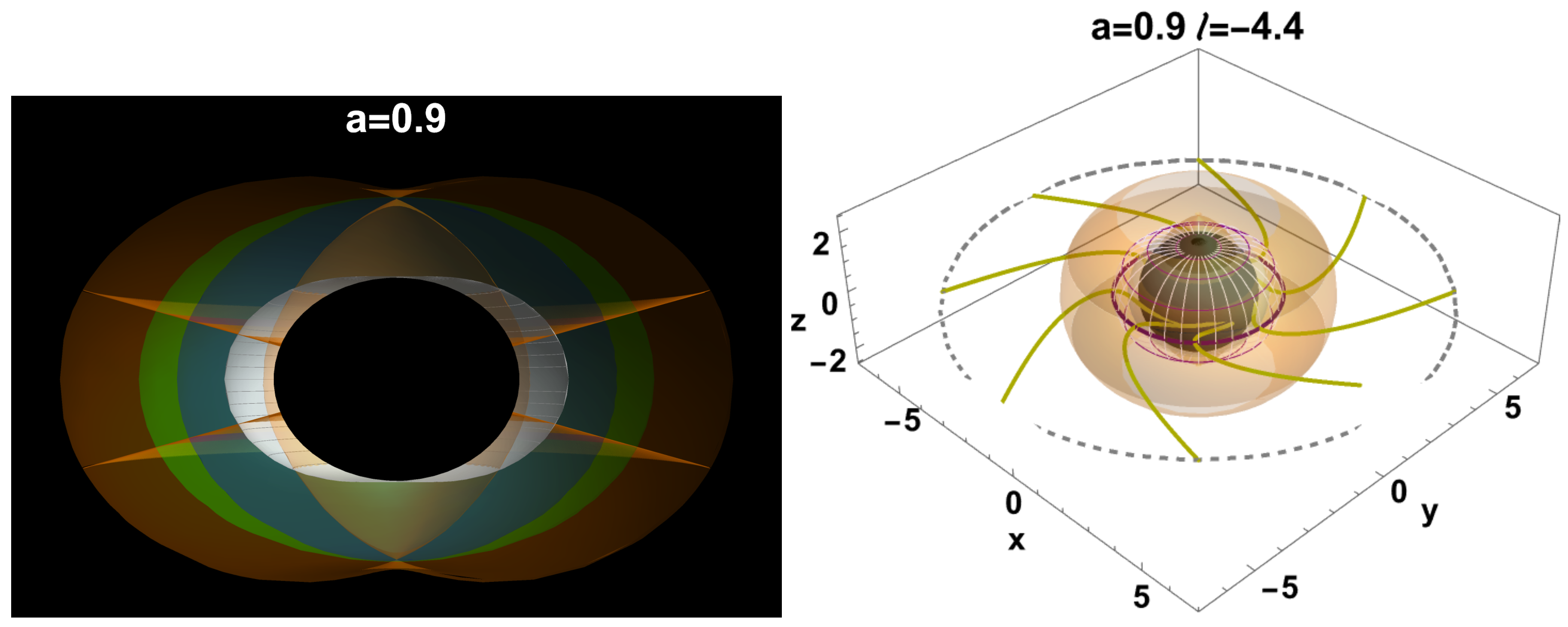

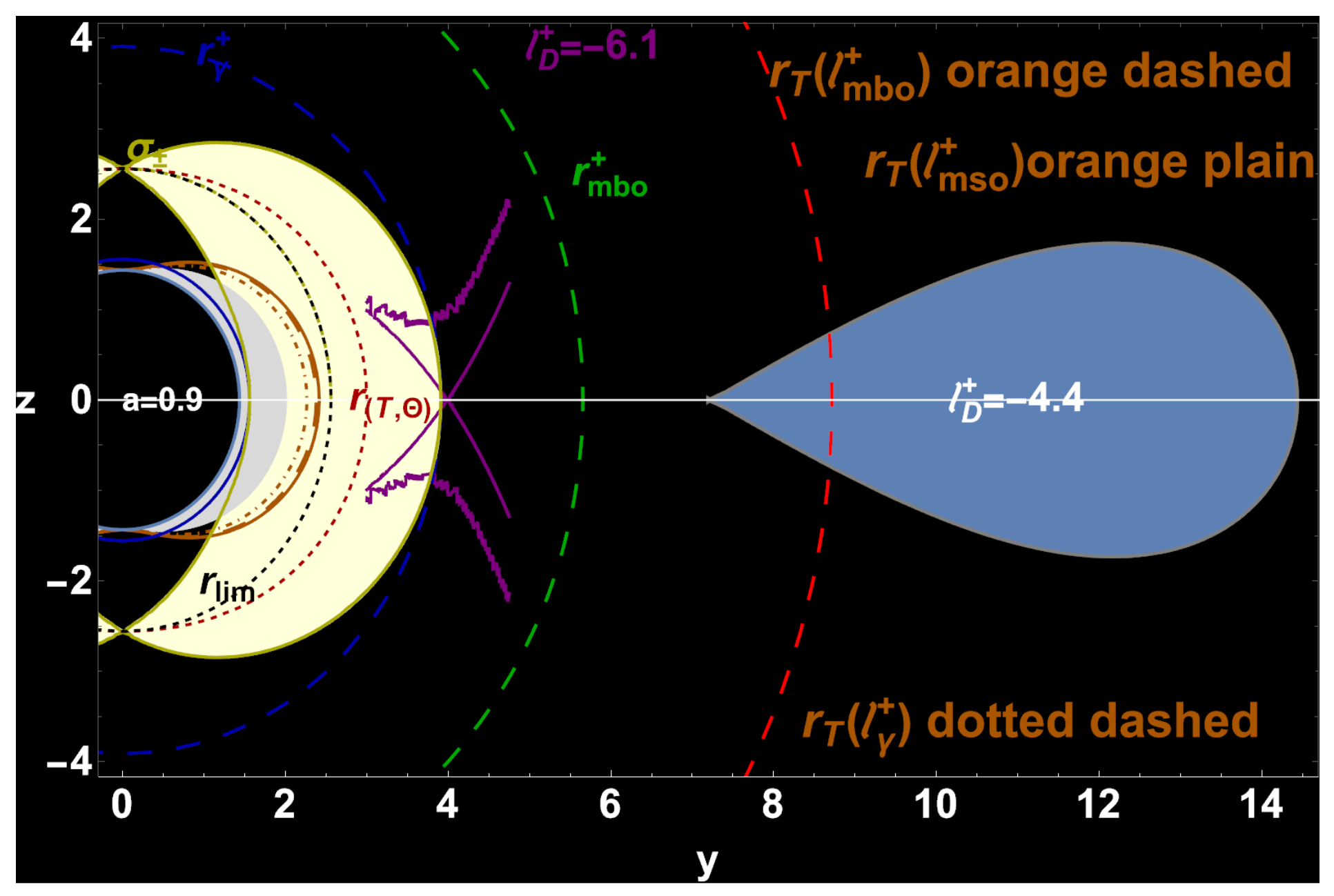

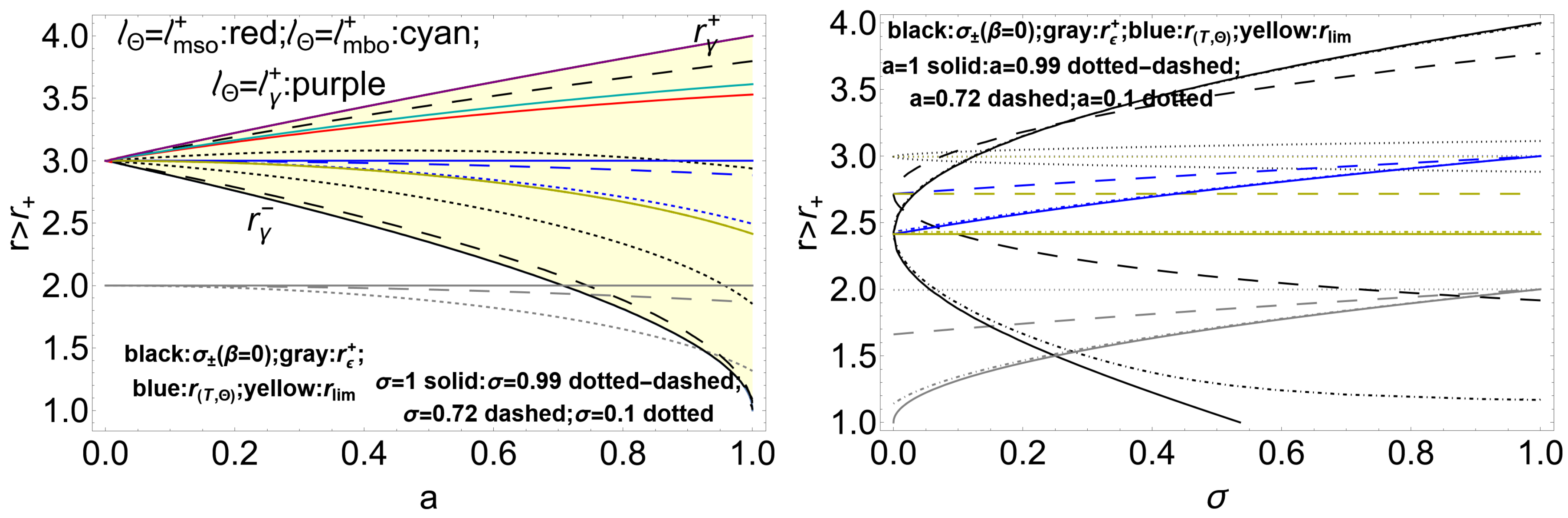

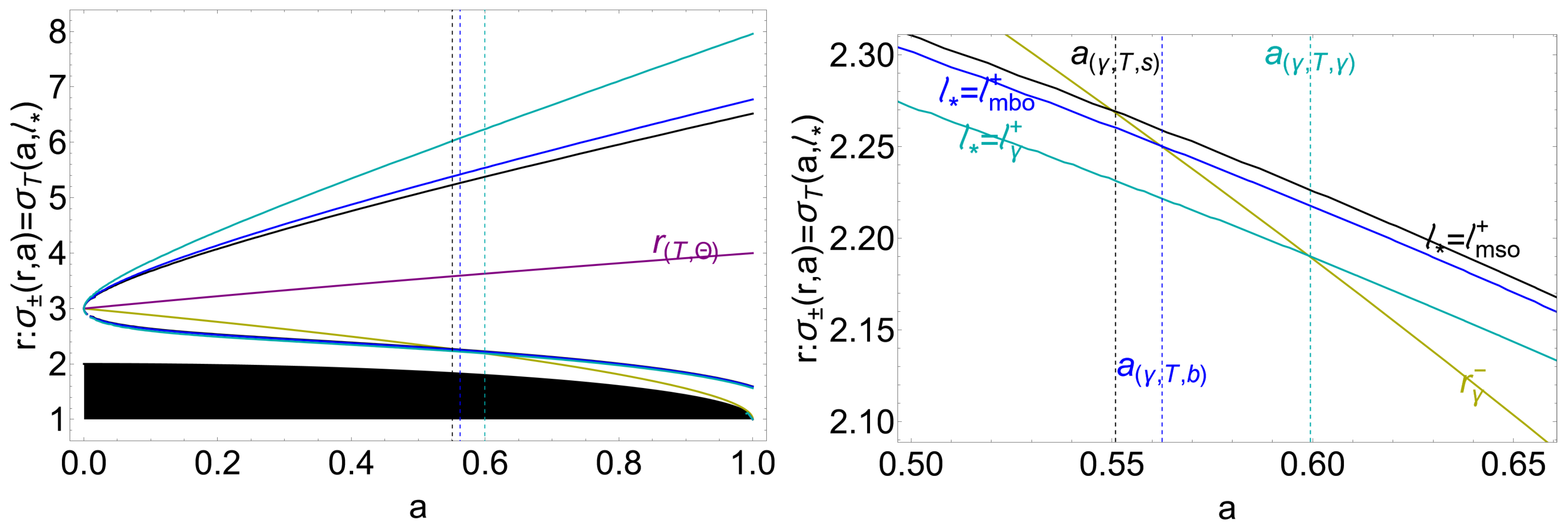

3. Shadows

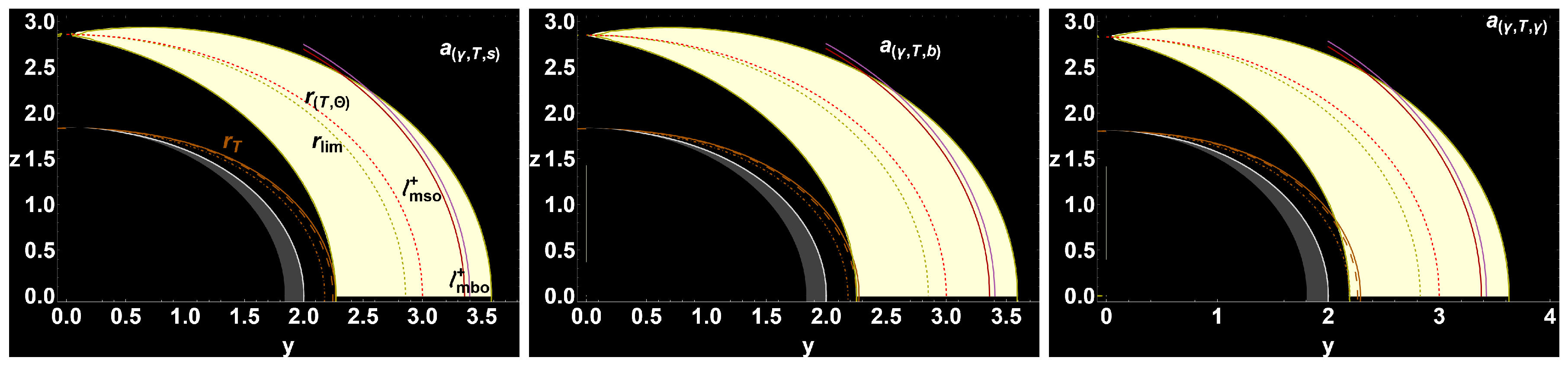

3.1. Counter-Rotating Tori Orbiting the Central BH

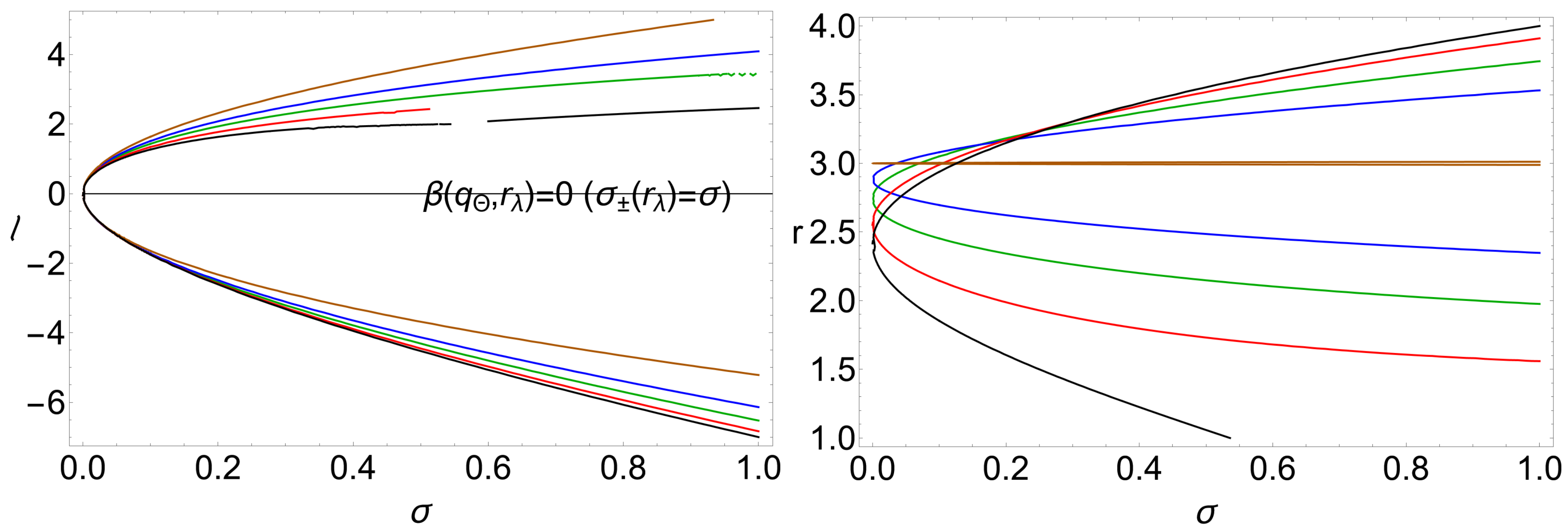

3.2. The Inversion Surfaces

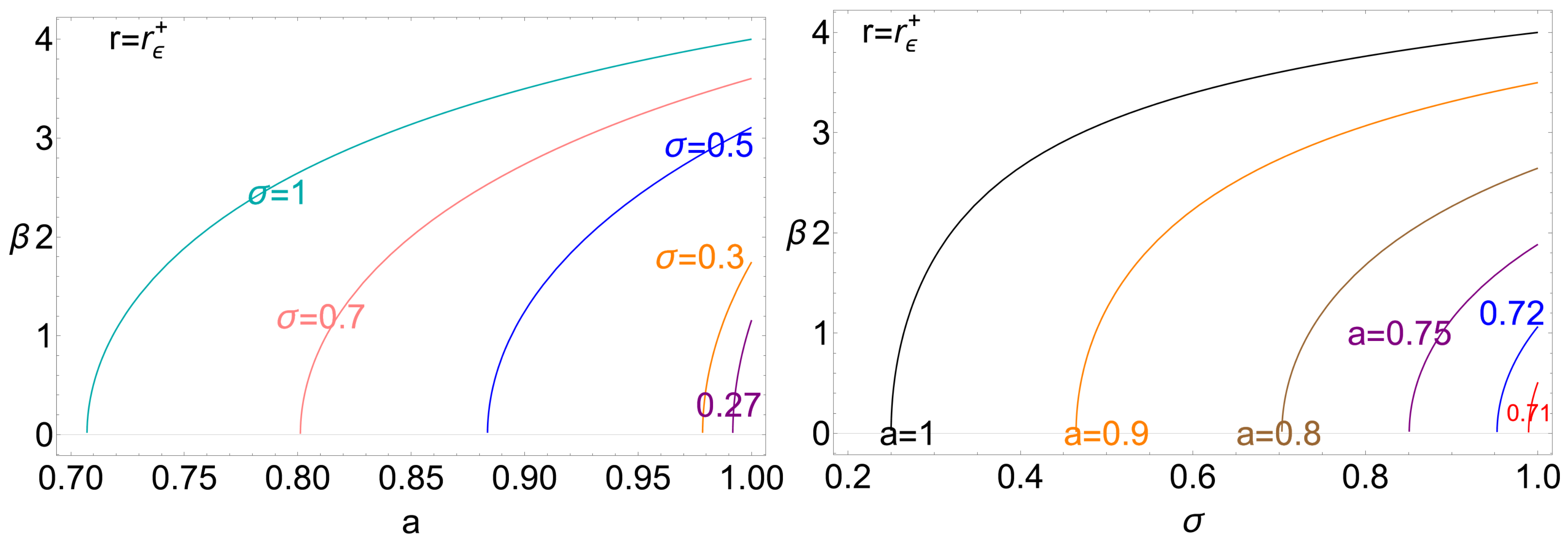

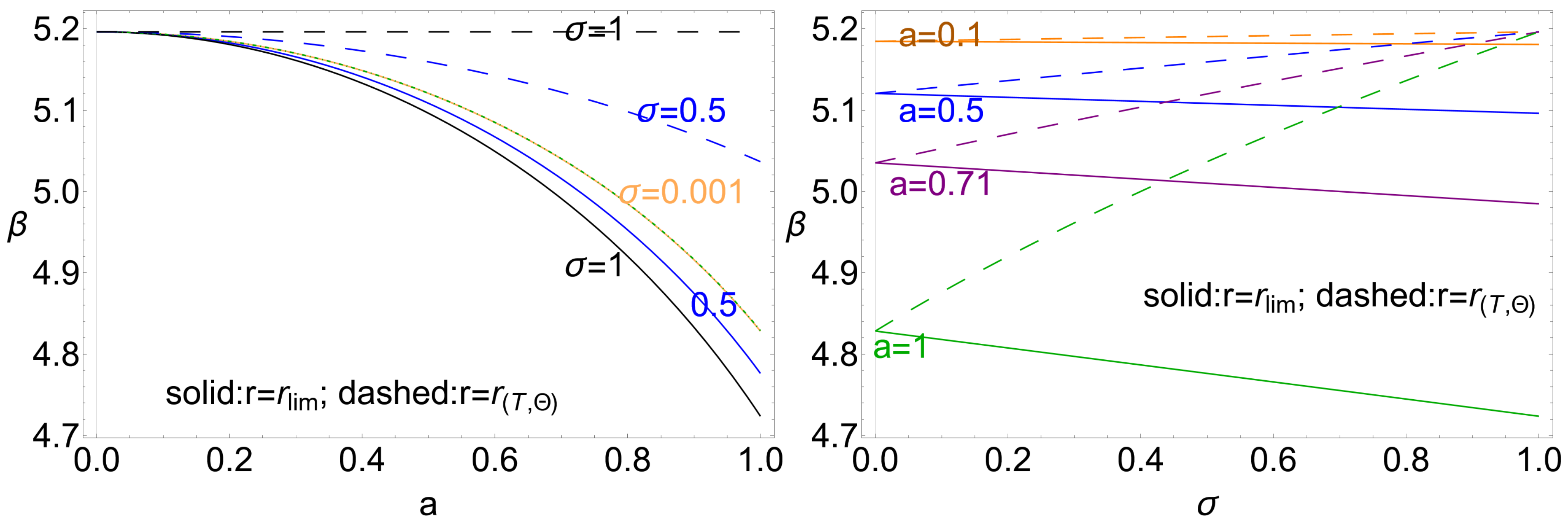

4. Shadow Boundary

5. Redshift Imaging

6. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Following [28], they are classified according to the number of “polar turning points”, or “half polar-orbits” they complete before escaping to infinity; that is, the number of half latitudinal (polar) oscillations around the BH photon’s shell prior to reaching infinity. A discussion on the possibility of fully distinguishing the photon rings (in the emission ring) with future development of EHT and with space-based stations is in [11]. |

| 2 | For more discussion on the relation between the critical curve and event horizon in the radiative simulations and near-horizon synchrotron ring images, see also [32]. |

| 3 | The BH is described, in many analyses, as having spin , determining the rotation orientation (defined by the angular momentum vector) of the (equatorial and axisymmetric) accretion disk and flow (both the direction and alignment of jet emission are also often considered). In this work, we consider a BH with spin , and an equatorial, axisymmetric, disk characterized by a well-defined relativistic specific angular momentum , corresponding to co-rotating and counter-rotating disks, respectively. Note, BH spin constraints in the literature are provided, for M87* and SgrA* accretion disk (and jet) systems; in terms of BH spin values , for co-rotating (or prograde) disks; and in terms of BH spin values for counter-rotating (or retrograde) disks. (Some ambiguities in this convention may arise in the case of accretion models based on a tilted (or misaligned) disk. The alignment axis of the jet within the system may also contribute to potential ambiguities. Further ambiguities emerge when considering multiple accretion disks, which may be relatively counter-rotating, orbiting the central BH, or if an accretion disk has an internal ringed structure with a non-homogeneous distribution of angular momentum featuring co-rotating and counter-rotating parts within its structure, or if the definition of the rotation direction of the accretion flow is understood to refer to the flow components in terms of the toroidal velocity rather than to the relative angular momentum). Within this set-up, we consider particles of the accretion flow with angular momentum (from the disk), and angular velocity , which depends on ℓ and (for counter-rotating flows) can change sign. |

| 4 | The EHT investigation obtained the (polarized) M87* images (of the accretion flows) in close proximity of the BH, i.e., in a region, on the equatorial plane, largely located between the marginally stable orbits and (co-rotating) photon circular orbits (the VLBI has resolved the millimeter wavelength synchrotron images for M87* and SgrA*, close to the central BH in a orbital radial range ). The data are confronted with a library of numerous models, finding consistency with the observations. The comparing models are constructed by fixing the underlying model parameters and varying their values within a prescribed range. These include the BH spin a, the observer viewing angle, the magnetic field strength and geometry, the jet structure, and the accretion disk prescriptions, such as different electron energy distributions and the electron-to-ion temperature ratio (additionally, models incorporating two-temperature plasma evolution have also been considered within radiative and non-ideal GRMHD frameworks). Thus, the libraries produce large sets of different synthetic images (also spectral energy distributions) from general relativistic (GR) ray tracing and GRMHD simulation, across a postulated set of values of BH spins and magnetization states. The GR ray-tracing and synchrotron radiation transfer are able to simulate images of flows close to the central BH, using simulated GRMHD evolution and an (mostly) ad hoc prescription of ion-to-electron temperature ratio. This framework bases the theoretical interpretation of the EHT observations. From the consistency with the simulated scenarios, we can infer information on the central attractor and disks, obtaining constraints on the BH spin, the electron-to-ion temperature ratio, the accretion flow (and disk) rotation orientation and, in some cases, the observer inclination relative to the accretion flow angular momentum. |

| 5 | In [29], different emission models were considered, where the view angle is fixed at 17°, and the BH spin has been fixed at and for co-rotating disks. |

| 6 | In [37,38,39] a library of synthetic images (from the ray-traced GRMHD models simulations) was created and then used to train the neural networks for the inference of the accretion disks-BH systems of SgrA*. It is found SgrA* spin , with a co-rotating accretion flow, a “weak” jet emission, disfavoring a MAD accretion disk with a powerful outflow. (On the other hand, as discussed in [40], a strong magnetic field in SgrA* does not imply a MAD state accompanied by a strong jet.) An assessment of the inclination angles is also given, with the spin axis closely aligned with the line of sight. While M87* is described as a BH with spin , a strong synchrotron emission from its jet and with a MAD counter-rotating accretion flow (disk). In these analyses, the accretion disks are equatorial and a magnetized turbulent accretion flow is also assumed. In [32], a set of radiative, two-temperature GRMHD MAD simulations of M87* is discussed, for different BH spins (considering bremsstrahlung, synchrotron and inverse Compton radiation, Coulomb coupling, viscous heating, adiabatic compression, and expansion). The analysis is a 3-D simulation with self-consistent evolution of electrons temperature and ions temperature. Within the assumptions (and the limitations) of this framework, the simulation favors a (larger) BH spin for counter-rotating disks (flows), and for co-rotating disks (flows). In [41] a library of several images of the MAD equatorial, axially symmetric, accretion disks flows of SgrA* and M87*, was provided, and the BH spin, inclination view angle, and accretion disk parameters such as rotation orientation, magnetic field (polarity), and electron temperature versus ion temperature, were discussed. Within the adopted models and their underlying assumptions, M87* was described as high-spin BH with a counter-rotating disk (and large ion-to-electron temperature ratio) |

| 7 | In [42] a library of ideal, non-radiative, GRMHD simulations for SgrA* is examined in SANE and MAD models and for BH spins is examined for co-rotating and counter-rotating disks. In SANE models, the angular momentum and energy flux features favor a (co-rotating) thin-disk, with BH spin . Also MAD model simulations favor a BH spin , with powerful jets (with sub-Keplerian accretion flow) and a co-rotating disk (leading possibly to a BH spin-down). |

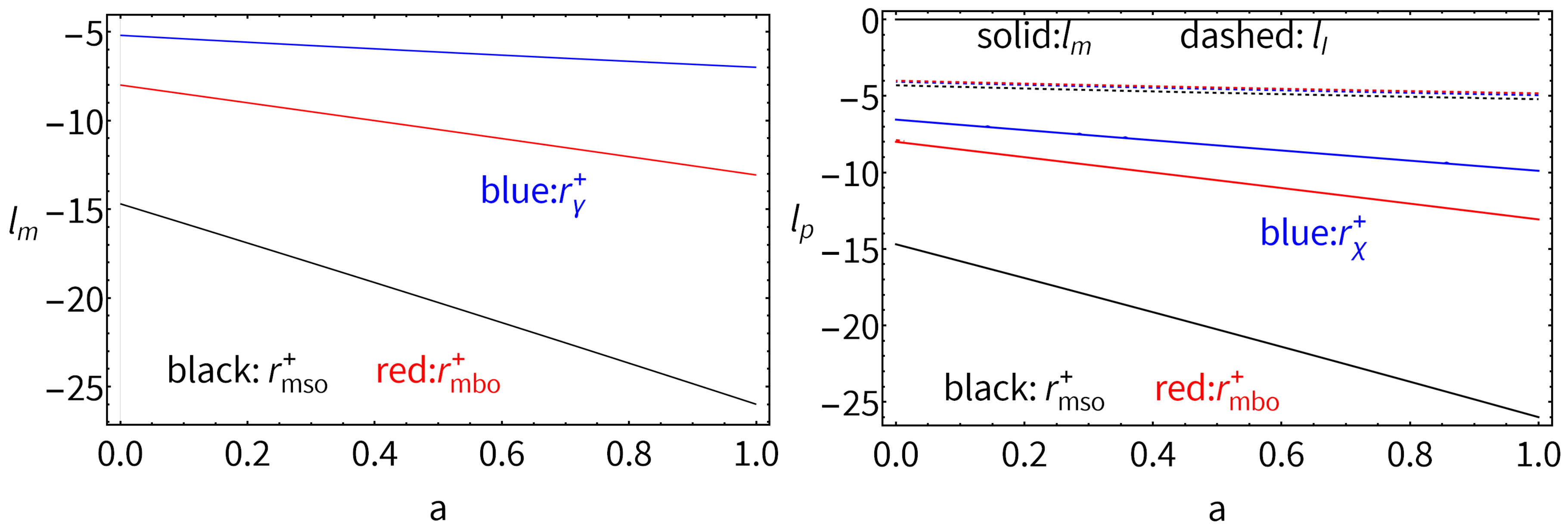

| 8 | Note, radii and also constrain the location of the counter-rotating tori [61]. |

| 9 | Below, we use the notation intended for any quantity evaluated on a radius . |

| 10 | |

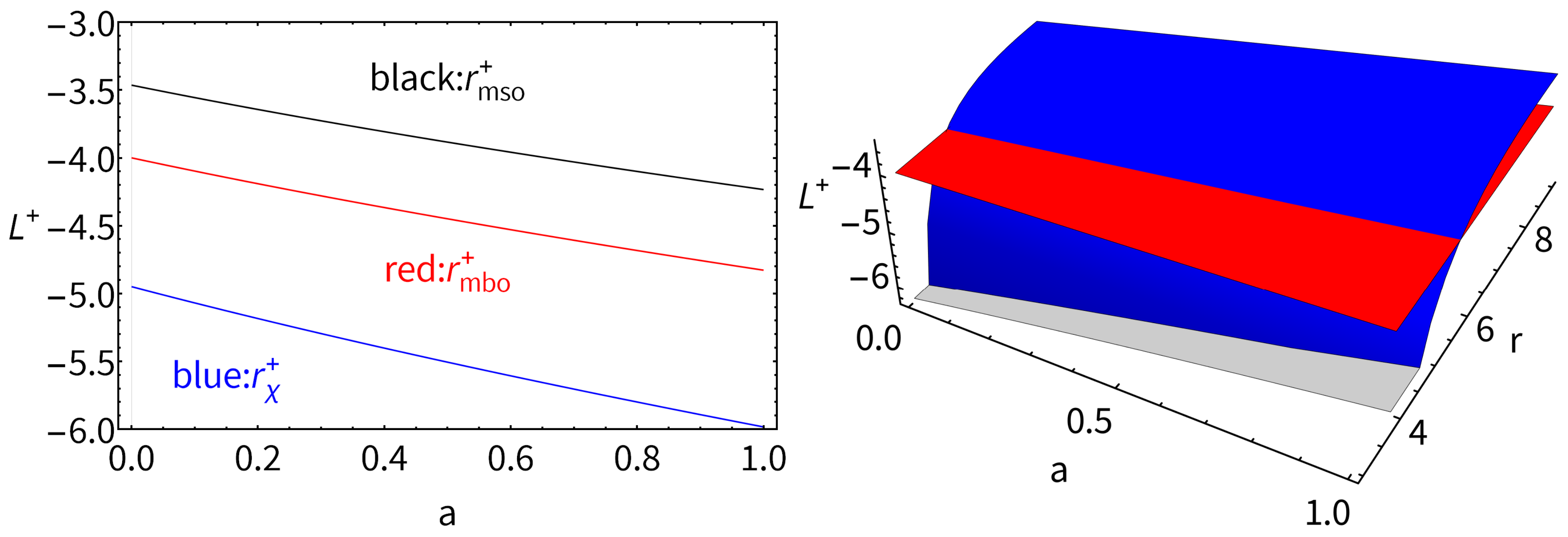

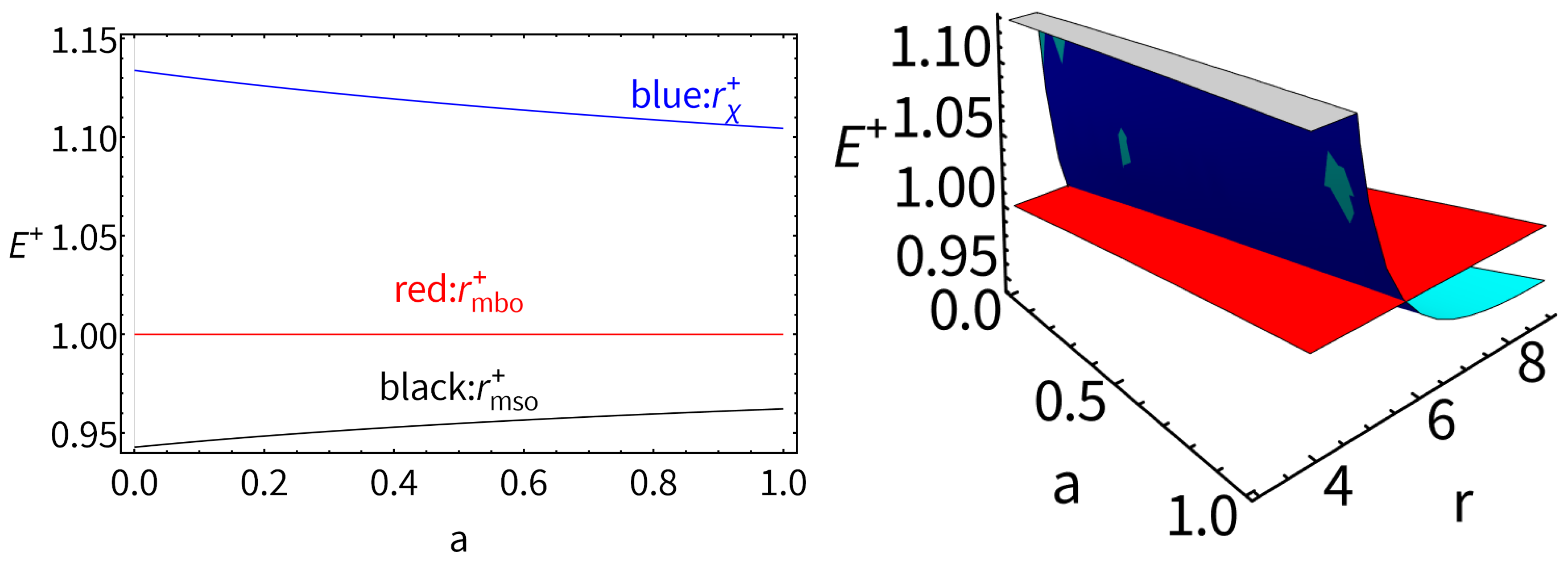

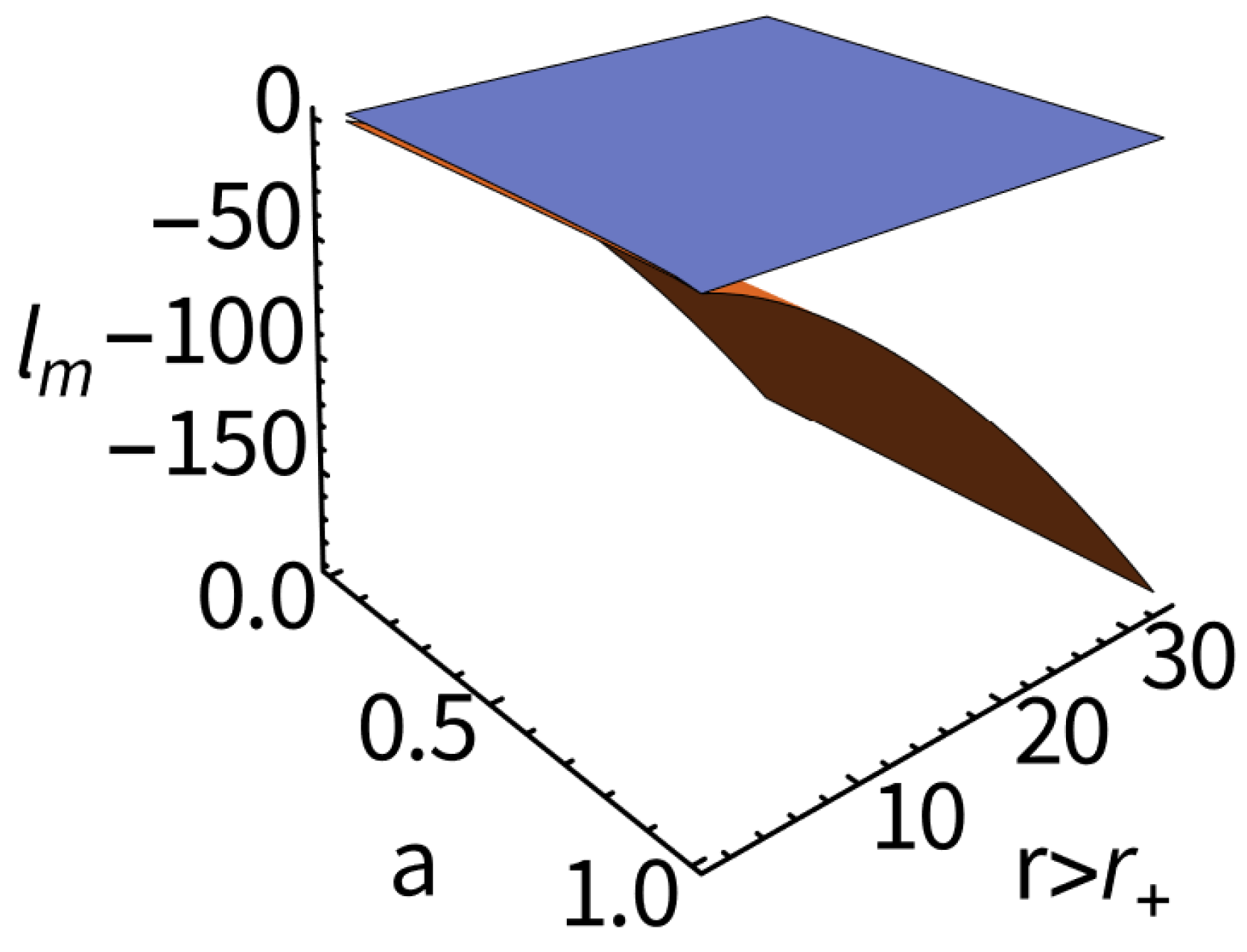

| 11 | The range of values obtained for all quantities in this analysis, when restricted to counter-rotating accretion disk configurations, is relatively narrow. This limited variation provides a distinct advantage in constraining counter-rotating configurations, possibly enhancing the precision with which constraints can be imposed on counter-rotating solutions in the Kerr metric. Here, the inner edge (surface cusp) of a counter-rotating disk in accretion is located in the radial range ; therefore, the values for the quantities referred to this range inform the counter-rotating cusped configurations. |

| 12 | This study also provides the range values for particles energy and momentum, reaching the BH from a counter-rotating cusped disk (or proto-jets). |

| 13 | From this perspective, counter-rotating disks become progressively more constrained at high spin values, reflecting the dynamical limits imposed by the Kerr geometry. |

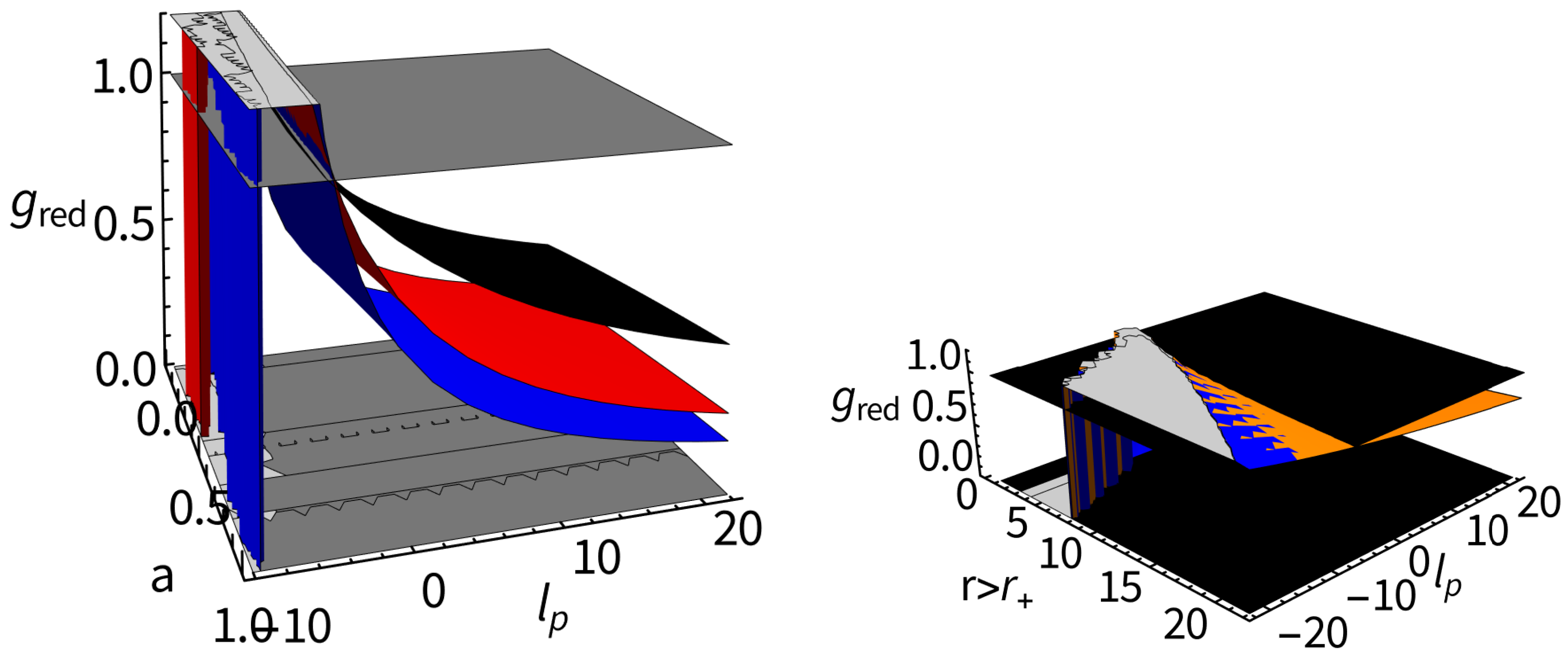

| 14 | Then, the detection of blueshifted signals is potentially significant for constraining the parameter and for determining the orientation of disk rotation. |

| 15 | The gravitational field is primarily responsible for the redshift distortion close to the attractor. At large distances, the (kinetic) relativistic factor becomes predominant. |

References

- The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole. Astrophys. J. 2019, 875, L1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. II. Array and Instrumentation. Astrophys. J. 2019, 875, L2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. III. Data Processing and Calibration. Astrophys. J. 2019, 875, L3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. IV. Imaging the Central Supermassive Black Hole. Astrophys. J. 2019, 875, L4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. V. Physical Origin of the Asymmetric Ring. Astrophys. J. 2019, 875, L5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. VI. The Shadow and Mass of the Central Black Hole. Astrophys. J. 2019, 875, L6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First Sagittarius A* Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole in the Center of the Milky Way. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2022, 930, L12. [Google Scholar]

- Porth, O.; Chatterjee, K.; Narayan, R.; Gammie, C.F.; Mizuno, Y.; Anninos, P.; Baker, J.G.; Bugli, M.; Chan, C.; Davelaar, J. The Event Horizon General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Code Comparison Project. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2019, 243, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralla, S.E.; Holz, D.E.; Wald, R.M. Black hole shadows, photon rings, and lensing rings. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 100, 024018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralla, S.E.; Lupsasca, A. Lensing by Kerr Black Holes. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 101, 044031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Lupsasca, A.; Strominger, A.; Wong, G.N.; Hadar, S.; Kapec, D.; Narayan, R.; Chael, A.; Gammie, C.F.; Galison, P.; et al. Universal interferometric signatures of a black hole’s photon ring. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R.; Johnson, M.D.; Gammie, C.F. The Shadow of a Spherically Accreting Black Hole. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2019, 885, L33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, F.H.; Wielgus, M.; Abramowicz, M.A.; Gourgoulhon, E.; Lasota, J.P.; Paumard, T.; Perrin, G. Geometric modeling of M87* as a Kerr black hole or a non-Kerr compact object. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 646, A37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Falcke, H.; Kadler, M.; Ros, E.; Wielgus, M.; Akiyama, K.; Baloković, M.; Blackburn, L.; Bouman, K.L.; Chael, A.; et al. Event Horizon Telescope observations of the jet launching and collimation in Centaurus A. Nat. Astron. 2021, 5, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Liska, M.; Tchekhovskoy, A.; Markoff, S.B. Accelerating AGN jets to parsec scales using general relativistic MHD simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2019, 490, 2200–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchini, M.; Kraub, F.; Markoff, S. The unique case of the active galactic nucleus core of M87: A misaligned low-power blazar. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2019, 489, 1633. [Google Scholar]

- Emami, R.; Anantua, R.; Chael, A.A.; Loeb, A. Positron Effects on Polarized Images and Spectra from Jet and Accretion Flow Models of M87* and Sgr A*. Astrophys. J. 2021, 923, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantua, R.; Dúran, J.; Ngata, N.; Oramas, L.; Emami, R.; Ricarte, A.; Curd, B.; Röder, J.; Broderick, A.; Wayland, J. Emission Modeling in the EHT—ngEHT Age. Galaxies 2023, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, F.; Thide, B.; Della Valle, M. Measurement of the spin of the M87 black hole from its observed twisted light. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 2020, 492, L22–L27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, D.; Stuchlík, Z. Constraining photon trajectories in black hole shadows. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2024, 139, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlick, V. Gravitational Lensing from a Spacetime Perspective. Living Rev. Relativ. 2004, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, E. Spherical orbits around a Kerr black hole. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2021, 53, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.M. Black Holes; DeWitt, C., DeWitt, B.S., Eds.; Gordon & Breach: New York, NY, USA, 1973; p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, C.T.; Bardeen, J.M. The Optical Appearance of a Star Orbiting an Extreme Kerr Black Hole. Astrophys. J. 1973, 183, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synge, J.L. The escape of photons from gravitationally intense stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1966, 131, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luminet, J.P. Image of a spherical black hole with thin accretion disk. Astron. Asrophys. 1979, 75, 228. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar, S. The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes. In Oxford Classic Texts in the Physical Sciences; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Walia, R.; Kocherlakota, P.; Chang, D.O.; Salehi, K. Spacetime measurements with the photon ring. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 104074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble, L.S.; Cárdenas-Avendaño, A.; Palumbo, D.C.M. Inferring black hole spin from interferometric measurements of the first photon ring: A geometric approach. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 103042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, A.E.; Tiede, P.; Pesce, D.W.; Gold, R. Measuring Spin from Relative Photon-ring Sizes. Astrophys. J. 2022, 927, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricarte, A.; Tiede, P.; Emami, R.; Tamar, A.; Natarajan, P. The ngEHT’s Role in Measuring Supermassive Black-Hole Spins. Galaxies 2023, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chael, A. Survey of radiative, two-temperature magnetically arrested simulations of the black hole M87* I: Turbulent electron heating. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2025, 537, 2496–2515. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, F.H.; Gralla, S.E.; Lupsasca, A.; Wielgus, M. Images and photon ring signatures of thick disks around black holes. Astron. Astrophys. 2022, 667, A170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.S. Observational Constraints onBlack Hole Spin. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 59, 117–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemmen, R. The Spin of M87*. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2019, 880, L26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, D.C.M.; Baubock, M.; Gammie, C.F. Multifrequency Analysis of Favored Models for the Messier 87* Accretion Flow. Astrophys. J. 2024, 970, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Chan, C.K.; Davelaar, J.; Wielgus, M. Deep learning inference with the Event Horizon Telescope-III. ZINGULARITY results from the 2017 observations and predictions for future array expansions. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 698, A62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Chan, C.-K.; Davelaar, J.; Natarajan, I.; Olivares, H.; Ripperda, B.; Röder, J.; Rynge, M.; Wielgus, M. Deep learning inference with the Event Horizon Telescope: I. Calibration improvements and a comprehensive synthetic data library. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 698, A60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Chan, C.-k.; Davelaar, J.; Wielgus, M. Deep learning inference with the Event Horizon Telescope: II. The ZINGULARITY framework for Bayesian artificial neural networks. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 698, A61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galishnikova, A.; Philippov, A.; Quataert, E.; Chatterjee, K.; Liska, M. Strongly magnetized accretion with low angular momentum produces a weak jet. Astrophys. J. 2025, 978, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Ricarte, A.; Narayan, R.; Wong, G.N.; Chael, A.; Palumbo, D. Using Machine Learning to link black hole accretion flows with spatially resolved polarimetric observables. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2023, 520, 4867–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhruv, V.; Prather, B.; Wong, G.N.; Gammie, C.F. A Survey of General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Models for Black Hole Accretion Systems. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 2025, 277, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papavasileiou, T.V.; Kosmas, O.; Kosmas, T.S. Asimplified approach for reproducing fully relativistic spectra in X-ray binary systems: Application to Cygnus X-1. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 693, A75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Sansigre, A.; Taylor, A.M. The Cosmological Consequence of an Obscured Agn Population on the Radiation Efficiency. Astrophys. J. 2009, 692, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajnovic, D.; Weilbacher, P.M.; Urrutia, T.; Emsellem, E.; Carollo, C.M.; Shirazi, M.; Bacon, R.; Contini, T.; Epinat, B.; Kamann, S.; et al. Unveiling the counter-rotating nature of the kinematically distinct core in NGC 5813 with MUSE. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2015, 452, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, R.; Mandel, I. Conditions for accretion disc formation and observability of wind-accreting X-ray binaries. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2021, 38, e056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, D. Counter-rotating black holes from FRII lifetimes. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2023, 10, 1123209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, D. Retrograde versus Prograde Models of Accreting Black Holes. Adv. Astron. 2013, 213105, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshkayev, K.; Konysbayev, T.; Kurmanov, Y.; Luongo, O.; Muccino, M.; Taukenova, A.; Urazalina, A. Luminosity of accretion disks around rotating regular black holes. Eur. Phys. J. C 2024, 84, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-M.; Songsheng, Y.-Y.; Li, Y.-R.; Du, P.; Zhe, Y. Dynamical evidence from the sub-parsec counter-rotating disc for a close binary of supermassive black holes in NGC-1068. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2020, 497, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papavasileiou, T.; Kosmas, O.; Kosmas, T. Implications of the Spin-Induced Accretion Disk Truncation on the X-ray Binary Broadband Emission. Particles 2024, 7, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.A.; Reeves, J.N.; Hardcastle, M.J.; Kraft, R.P.; Lee, J.C.; Virani, S.N. The Hard X-Ray View Of Reflection, Absorption, and the Disk-Jet Connection in the Radio-Loud AGN 3C 33. Astrophys. J. 2010, 710, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.D.; Bhuvana, G.R.; Das, S.; Nandi, A. Revisiting disc-jet coupling in black hole X-ray binaries: On the nature of disc dynamics and jet velocity. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2025, 541, 2934–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, D.; Evans, D.A.; Sambruna, R.M. The evolution of radio-loud active galactic nuclei as a function of black hole spin. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2010, 406, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchekhovskoy, A.; McKinney, J.C. Prograde and retrograde black holes: Whose jet is more powerful? Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2012, 423, L55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, W.; Karas, V.; Dovciak, M. Predictions for reverberating spectral line from a newly formed black hole accretion disk: Case of tidal disruption flares. Astrophys. J. 2015, 807, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.; Reynolds, C.S. X-Ray Reverberation from Black Hole Accretion Disks with Realistic Geometric Thickness. Astrophys. J. 2018, 868, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, D.; Stuchlík, Z. photon shells, Black Hole Shadows, and Accretion Toroids. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2024, 275, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B. Global Structure of the Kerr Family of Gravitational Fields. Phys. Rev. 1968, 174, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowicz, M.A.; Fragile, P.C. Black Hole Accretion Disks. Liv. Rev. Rel. 2013, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, D.; Stuchlík, Z. Ringed accretion disks. Astrophys. J. 2015, 221, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, M.; Jaroszynsk, M.; Abramowicz, M.A. The analytic theory of fluid disks orbiting the Kerr black hole. Astron. Astrophys. 1978, 63, 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowicz, M.; Jaroszynski, M.; Sikora, M. Relativistic, accreting disks. Astron. Astrophys. 1978, 63, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski, A.; Lasota, J.P.; Abramowicz, M.A.; Narayan, R. Black hole feedback from thick accretion discs. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2016, 456, 3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasota, J.P.; Vieira, R.S.S.; Sadowski, A.; Narayan, R.; Abramowicz, M.A. The slimming effect of advection on black-hole accretion flows. Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 587, A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, D.; Stuchlík, Z. Proto-jet configurations in RADs orbiting a Kerr SMBH: Symmetries and limiting surfaces. Class. Quant. Grav. 2018, 35, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyutikov, M. Magnetocentrifugal launching of jets from discs around Kerr black holes. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2009, 396, 1545–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madau, P. Thick accretion disks around black holes & the UV/soft X-ray excess in quasars. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 1988, 327, 116–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sikora, M. Superluminous Accretion Discs. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 1981, 196, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, D.; Stuchlík, Z. Lense—Thirring effect on accretion flow from counter-rotating tori. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2022, 512, 5895–5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pugliese, D.; Stuchlík, Z. On the Counter-Rotating Tori and Counter-Rotating Parts of the Kerr Black Hole Shadows. Universe 2025, 11, 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11120417

Pugliese D, Stuchlík Z. On the Counter-Rotating Tori and Counter-Rotating Parts of the Kerr Black Hole Shadows. Universe. 2025; 11(12):417. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11120417

Chicago/Turabian StylePugliese, Daniela, and Zdenek Stuchlík. 2025. "On the Counter-Rotating Tori and Counter-Rotating Parts of the Kerr Black Hole Shadows" Universe 11, no. 12: 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11120417

APA StylePugliese, D., & Stuchlík, Z. (2025). On the Counter-Rotating Tori and Counter-Rotating Parts of the Kerr Black Hole Shadows. Universe, 11(12), 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11120417