1. Introduction

Understanding the dynamics of the universe in its early stages remains one of the main challenges of modern cosmology. It is postulated that during its initial moments, when the energy density and spacetime curvature were extreme, the gravitational interaction was quantized [

1]. In this quantum-gravitational regime, the geometry of the universe could not be described by classical general relativity but instead behaved as a highly fluctuating structure, resembling a resonant quantum foam, where multiple spatial configurations coexist in superposition [

2]. This concept implies that the universe may have begun in an inhomogeneous and anisotropic state, far from the symmetric and uniform picture we observe today. However, over time and driven by mechanisms such as accelerated expansion, this primordial universe would have evolved toward a simpler configuration: homogeneous and isotropic on large scales, as described by the standard Friedmann-Robertson-Walker (FRW) cosmological model [

3,

4].

In this context, studies on the process of isotropization and how an initially anisotropic universe can evolve into an isotropic one have been widely developed with the aim of reconstructing the history of the early universe and exploring possible imprints of its quantum origin. From a classical perspective, it has been shown that homogeneous anisotropic models of Bianchi type [

5,

6] tend to isotropic solutions in the presence of a positive cosmological constant [

7] or in the presence of a reduced relativistic gas (RRG) [

8]. The same process of isotropization also takes place in Kantowski-Sachs cosmological models filled with a phantom perfect fluid [

9] or with a running cosmological constant [

10]. Moreover, dynamical investigations of these models have identified various conditions and mechanisms, such as cosmic viscosity, the presence of a radiation fluid, interactions with scalar fields, or even the action of dark energy, that can favor such evolution toward isotropy [

11,

12,

13]. In the specific case of Bianchi I cosmological models, we may mention several works dealing with the above-mentioned and other aspects of these models. In Ref. [

14], the authors investigated how the presence of a viscous fluid influences the isotropization of a Bianchi I model. A nonminimal extension of the Einstein-Maxwell equations was coupled to Bianchi I models in the presence of a magnetic field in Ref. [

15]. The authors obtained several exact solutions of the nonminimal system, including those that described isotropization, inflation, and an isotropic de Sitter solution characterized by a ‘screening’ of the magnetic field as a consequence of the nonminimal coupling. In Ref. [

16], the authors considered the effects of the presence of Skyrmes and a positive cosmological constant in two anisotropic cosmologies. They studied Kantowski-Sachs and Bianchi-I universes and determined the conditions for the late time isotropization of both universes. The authors discussed in Ref. [

17] the possible description of the big bang–big crunch cosmological singularities crossing in a Bianchi I universe filled with minimally and conformally coupled massless scalar fields. In Ref. [

18], the authors studied the effects of a spatially homogeneous magnetic field in Bianchi I cosmological models. They considered three models filled with a spatially homogeneous magnetic field (SHMF) and different matter contents. In the first one, there was just the SHMF, in the second one, an extra dust fluid, and in the third, an extra massless scalar field (stiff matter). They paid special attention to the identification of the initial and final states of these models and the transition between them. Another important application of the study of anisotropic cosmological models has to do with the presence of anomalies in CMB radiation and the low-quadrupole moment of that radiation. These anomalies in the CMB may be explained by plane-mirroring symmetry on large scales. The low-quadrupole moment in the CMB may indicate an ellipsoidal expansion of the universe [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. In the quantum context, research developed within loop quantum cosmology has shown that specific anisotropic models, such as Bianchi I, can undergo isotropization as a natural result of the evolution of the universe in quantum-corrected geometries without the need to impose additional external conditions [

29,

30]. There are also works that studied Bianchi I cosmological models, at the quantum level, using the formalism of quantum cosmology [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

The Bianchi III model, which represents an anisotropic universe with negative spatial curvature, has been extensively investigated in both classical contexts and modified gravity theories. It has been used to study isotropization mechanisms in anisotropic cosmologies [

36], the dynamics of dark energy in general relativity [

37], and alternative formulations such as Lyra geometry with quadratic equations of state [

38]. Within modified gravity theories, the Bianchi III model has been analyzed in

gravity, exhibiting accelerated expansion and non-singular behaviors [

39]. Furthermore, quantum extensions of the model have been explored, for instance, within Hořava–Lifshitz gravity and in Bianchi III minisuperspace models coupled to electromagnetic fields, where both canonical classical quantization and Wheeler–DeWitt approaches have been employed [

40]. These studies illustrate the use of the Bianchi III metric as a framework for examining anisotropies, isotropization, and cosmic acceleration within different theoretical approaches.

Beyond these classical and modified gravity frameworks, another promising approach involves spacetime noncommutativity, which was first introduced by Snyder in the 1940s as an attempt to regularize divergences in quantum field theory without breaking Lorentz symmetry [

41]. In his proposal, spacetime coordinates ceased to commute, giving rise to a modified geometric structure at tiny scales. Although initially overlooked, this idea experienced a significant resurgence due to developments in string theory, membrane theory, and M-theory, where noncommutativity naturally emerges in specific physical regimes [

42,

43,

44]. In this new context, spacetime noncommutativity has become the subject of intense investigation, particularly in cosmology. Various studies have shown that noncommutative (NC) effects can profoundly alter the dynamics of the early universe [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51], even contributing to the elimination of singularities and modifying the expansion process. This suggests that noncommutativity played an active role throughout all stages of cosmic evolution. One of the primary motivations for incorporating this structure into classical cosmological models is the possibility that residual observable effects may persist to the present day.

Consequently, a growing line of research in cosmology involves extending anisotropic models by incorporating NC structures in phase space. This proposal, motivated by advances in string theory and quantum gravity, introduces a parameter

that deforms the Poisson algebra between dynamical variables. These modifications allow for the exploration of alternative evolutionary trajectories and have been associated with mechanisms that could suppress anisotropies, induce accelerated expansion, or eliminate singularities [

45,

46]. However, the specific study of the Bianchi I (flat curvature) and Bianchi III (negative curvature) models during the radiation-dominated era within this NC framework remains limited. We may mention Refs. [

47,

50,

51], where NC Bianchi I models are studied. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, the noncommutative deformation of Bianchi III cosmologies has not yet been explored, providing motivation for its consideration in the present work.

Therefore, this study aims to analyze the dynamical evolution of the locally rotationally symmetric (LRS) NC Bianchi I and Bianchi III cosmological models, coupled to a perfect radiation fluid, investigating the effects of the NC parameter

on the expansion and isotropization processes. Since we believe noncommutativity was more important during the early stages of the universe, we consider as the matter content of the cosmological model described here a radiation fluid, which was dominant during that period. Our main motivation to choose the LRS version of these spacetimes is the similarities between the metrics. As we shall see later, these similarities will allow us to compare some results coming from Bianchi I and III cosmological models in a simple way. As a matter of completeness, we mention that the LRS version of Bianchi I and III lets the metric of these spacetimes be very similar to the metric of the Kantowski–Sachs spacetime (positive curvature) [

52]. Unfortunately, as we shall see later, the Kantowski–Sachs model will not be studied in the present work because it does not produce expanding solutions under the conditions considered here. The parameter

is introduced due to a deformed Poisson bracket algebra. More precisely, it appears because we introduce four nontrivial Poisson brackets between all geometrical variables and the matter variables of the model. We associate the same NC parameter

with all nontrivial Poisson brackets. An important difference between the present paper and the Refs. [

47,

50,

51], is that here we use the LRS form of the Bianchi I metric. Also, we may say that the present model is more noncommutative than the one considered in Ref. [

50]. This is the case because the authors of Ref. [

50] considered only two nontrivial Poisson brackets between the geometrical variables and the matter variables of the model. The content of matter in the model of Ref. [

50] is the same as in the present model. On the other hand, the authors in Ref. [

51] introduced six nontrivial Poisson brackets and in Ref. [

47] four nontrivial Poisson brackets, all just between the geometrical variables of the model. The model in Ref. [

51] differs from the present model and from the ones in Refs. [

47,

50], because the content of matter there was given by an RRG. Another important difference between the present model and the one in Ref. [

51] is the use of the symplectic formalism to introduce the deformed Poisson bracket algebra. Finally, in Ref. [

47], the authors solved the dynamical equations in the WKB approximation, while here we solve the complete equations numerically. Besides, they considered a cosmological constant. Additionally, here a quantitative estimation of

is proposed on the basis of the assumption that the universe has evolved toward a homogeneous and isotropic state at present. This work seeks to evaluate whether noncommutativity may have played a significant role in the early universe and whether its influence can be distinguished from that of commutative models. Furthermore, a systematic comparison was made between the flat (Bianchi I) and open (Bianchi III) models, exploring their differences in terms of sensitivity to the NC deformation. This approach not only enriches the theoretical framework of anisotropic cosmology but may also open new avenues for connecting predictions from NC models with current or future cosmological observations.

Finally, the structure of this work is organized as follows. In

Section 2, the Bianchi I and Bianchi III cosmological models coupled to a perfect fluid are introduced, and the superhamiltonian of the models is derived. In

Section 3, we define the NC Poisson brackets through the parameter

, and the equations of motion are obtained in terms of new commutative variables. In

Section 4, we consider the case of a radiation fluid. We numerically solve the system of dynamical equations and obtain the behaviors of the scale factor and the anisotropy parameter. We present a detailed study of their various behaviors and a comparison with the commutative case. In

Section 5, the parameter

is estimated from observational data, assuming a homogeneous and isotropic universe. Finally, in

Section 6, we discuss and summarize the most relevant results of the paper.

2. The Bianchi Models for Any Perfect Fluid

The LRS line element, which encompasses the spacetimes of Bianchi I (BI), Bianchi III (BIII), and Kantowski-Sachs (KS) [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56], allows a unified description of such homogeneous and anisotropic universes. Inspired by Misner’s parametrization [

57], this LRS line element can be expressed as [

9],

Here,

represents the isotropic scale factor,

is the parameter describing anisotropy,

is the lapse function,

takes the specific forms:

, respectively, for the following spacetimes BI, KS, BIII. In the present work, we use

geometrized units first introduced in Ref. [

58]. In these units the speed of light

c, Newton’s gravitational constant

, and Boltzman’s constant

are all equal to unity. The standard unit, in terms of which everything is measured in this paper, is centimeters. If one wants to recover the standard units, one has to multiply or divide the quantity by a particular factor of unity. For example, if one has a time value in

geometrized units and wants to obtain it in seconds, one must divide it by the following factor unity:

cm/s. For a full list of factors of unity see Ref. [

58]. However, in

Section 5 we use conventional units to estimate the NC parameter

. The main motivation to use the

geometrized units is that we may use time scales and parameter values that allow the numerical calculations and the production of graphics where the behavior of the functions are easily shown. In the metric

, the anisotropy depends on the parameter

, which produces differences in the expansion rates along different spatial directions. It is expected that

at late times, implying that the universe, although initially anisotropic, evolves toward an isotropic FRW-like state. It is known in the literature that the Bianchi I and the Kantowski-Sachs spacetimes tend to the FRW spacetime at late times. However, the Bianchi III spacetime does not reach an exact FRW spacetime at late times. However, it becomes very similar to an FRW spacetime for a period of its evolution [

59]. Here, we are going to study the conditions in which the Bianchi III spacetime becomes very similar to an FRW spacetime.

The energy content of the universe can be represented by a perfect fluid. The four-velocity of this fluid, typically expressed as

, defines a comoving frame where matter exhibits no spatial motion and evolves only in time. This assumption significantly simplifies the calculations and provides a convenient basis for defining the energy-momentum tensor as

where

represents the energy density,

p the pressure, and

is the metric tensor. The equation of state of the fluid is given by

where

is a constant that characterizes the type of fluid.

As we mentioned in

Section 1, in the present paper, we introduce the noncommutativities as deformations in the Poisson algebra between the phase space variables of the model. Then, we must write the geometrical and matter Hamiltonians of the model. The Schutz’s variational formalism [

60] was developed to write the Hamiltonian of a perfect fluid with the equation of state (

3). Therefore, in the present paper we use Schutz’s variational formalism to write the Hamiltonian of a generic perfect fluid with equation of state (

3). In this approach, the four-velocity (

) of the fluid is expressed in terms of six thermodynamic potentials (

,

,

,

,

,

s) as follows,

where

is the specific enthalpy,

s is the specific entropy,

and

are associated with the vorticity of the fluid, while

and

lack a clear physical interpretation in this context. Additionally, the four-velocity must satisfy the normalization condition,

For these models, which do not assume vorticity, the potentials

and

vanish. In a comoving coordinate system with the perfect fluid, the expression for

simplifies, and the specific enthalpy

takes the form of

where the dot means derivative with respect to time

t and

N is a simplification in the notation of

, the lapse function, first introduced in the metric Equation (

1).

Considering the equation of state (

3), it can be shown by thermodynamic considerations that the pressure in this formalism has the form [

61],

This formulation links the thermodynamic properties of the fluid with the dynamical variables in Schutz’s formalism.

The action of the theory will be determined by the sum of the Einstein-Hilbert term and the action associated with the perfect fluid, and the total action can be written as

where

g is the determinant of the metric tensor,

R is the Ricci scalar and

is the Lagrangian density of matter, which is equal to the fluid pressure

p.

By computing the Ricci scalar

R from the metric (

1) and substituting

p Equation (

7), the action takes the explicit form

where

, with

corresponding to the BI model,

to the BIII model, and

to the KS model [

53,

62].

The Lagrangian density can be obtained from the action of the model Equation (

9) and using it, one may write the corresponding superhamiltonian, using the geometrodynamic formulation of general relativity [

2],

where

,

,

,

and

, are the canonically conjugate momenta of the dynamical variables of the model. The superhamiltonian (

10) can be simplified by performing the following canonical transformations [

61,

63],

Using the transformations (

11) in the matter term of the superhamiltonian (

10), it becomes a simpler expression,

Here,

is the only remaining canonical variable associated with matter [

61]. For simplicity, here we use the gauge

.

3. The Noncommutative Bianchi Models for Any Perfect Fluid

We consider that the NC Hamiltonian has the same form as the commutative Hamiltonian (

12). Our main motivation to write the NC Hamiltonian in the same form as the commutative one is simplicity. We believe that the introduction of other terms, not present in the commutative Hamiltonian, would be difficult to justify. It can be rewritten simply by placing the

index in the commutative variables, which we call NC variables, to differentiate it from the old variables. As we write below,

Here,

are, respectively, the canonically conjugated momenta to the coordinates

in the NC model.

The NC model is particularly relevant for exploring the early universe, where quantum gravity effects could be significant [

44]. In NC cosmology, it is assumed that some of the classical phase space variables do not commute, which introduces a modified algebra in this space [

45,

46,

48,

64]. For the present model, we introduce the following Poisson brackets (PBs):

Here,

is the NC parameter that should be a small, dimensionless quantity in our current universe. All effects resulting from noncommutativity are concentrated in this parameter. From a general point of view, the deformed Poisson brackets algebra introduces a modification in the phase space of theory. In particular, since Equation (

16) are Poisson brackets between geometrical and matter phase space variables and momenta, we expect new physical phenomena appearing in the geometrical as well as matter sectors of the NC model. In the present paper, we investigate the modifications introduced in the dynamics of the model due to the presence of the NC parameter

. More precisely, we want to know how the expansion of the universe is influenced by the NC structure. The main motivation for our choice of the commutation relations in Equation (

16) is an extension of a previous choice made in Ref. [

50]. It introduces a novelty in the part of the paper associated with the Bianchi I cosmological model, and it is, also, easier to compare.

Now, instead of working directly with the physical NC variables of the Hamiltonian (

13), as a matter of simplicity, we introduce new auxiliary canonical variables

, defined as

Here,

and

are new coordinates and momenta in a commutative phase space. They satisfy the usual commutative Poisson brackets:

and all other Poisson brackets are zero. It is possible to show that the new expressions of the NC variables, given in terms of the commutative variables and

Equation (

17), fully satisfy the Poisson brackets (

14)–(

16), up to the first order in

. These transformations Equation (

17) are also known as Bopp shifts [

65]. This technique of Bopp shift transformations is particularly significant in cosmology, as it provides a method to incorporate noncommutativity into classical systems by modifying the phase space coordinates [

45,

64].

With the aid of the transformations Equation (

17), we can rewrite the Hamiltonian (

13) in terms of the new coordinates and momenta, up to the first order in

, which gives us

Here,

represents the NC Hamiltonian, expressed in terms of the auxiliary commutative variables denoted by the subscript

c.

The Hamiltonian formalism provides a framework that describes the time evolution of a system through Hamilton’s equations. Using the Hamiltonian

(

18), the equations of motion for the BI, KS, and BIII models are given by:

To analyze the evolution of the universe, our goal is to solve the equations corresponding to the variables , , and , which are related to the physical variables and , as mentioned earlier. To achieve this, it is necessary to rewrite the equations of motion derived from the Hamiltonian , expressing them exclusively in terms of these variables and their time derivatives, thus eliminating explicit dependencies on the conjugate momenta. This approach simplifies the description of the dynamics of the system and makes it easier to analyze the impact of the corrections in on the evolution of the dynamic variables.

We observe that

Equation (

24) is proportional to

Equation (

20) with a factor of

. This implies

. Integrating this equation, we obtain the following expression for the canonical momentum,

where

C is a positive integration constant that represents the initial energy density of the fluid. This constant is a quantity that is conserved during the evolution of the system and is determined by the initial conditions.

Also, if we choose (

19) and (

21) from the equations of motion above and combine them, with the aid of Equation (

25), we may obtain the following expressions for canonical momenta

and

,

These equations express the canonical momenta

and

in terms of the variables

,

,

, and their time derivatives.

Now, substituting the canonical momenta

,

, and

from Equations (

25)–(

27) into the time evolution of the matter-associated variable Equation (

23), we obtain the following expression for

,

This equation describes the variable

in terms of

,

, and

, up to the first order in the NC parameter

.

Next, it is necessary to derive

(

19) and

(

21) with respect to time. This process allows for obtaining second-order differential equations, which is important to fully describe the temporal evolution of the system’s variables. Differential equations provide detailed information on how

and

evolve over time. Furthermore, deriving these expressions ensures a consistent physical description aligned with the system’s initial conditions and constraints. These second derivatives are as follows:

and

In this case, the derivatives of the canonical momenta

(

20),

(

22),

(

24) and the conjugate canonical momenta

(

26),

(

25),

(

27) were substituted.

The Hamiltonian

plays a crucial role as a constraint in the system

, ensuring that the dynamic trajectories satisfy the equations of motion along with the physical conditions established by the model. By substituting the conjugate canonical momenta

(

27) into the expression (

18), we obtain

This expression illustrates the dynamics dictated by the constraints of the Hamiltonian system, where the geometry of the universe (

) and the corrections due to the NC parameter

are incorporated within

.

4. Numerical Solution for a Radiation-Dominated Anisotropic Universe

From now on, we restrict our attention to the case of a radiation perfect fluid where

. The analytical solution of the coupled system of Equations (

28)–(

31) is unfeasible due to the nonlinearity of the terms in its variables for

. Therefore, we must solve it numerically. Furthermore, as mentioned above

. Then, using this property, in terms of the equations where

appears in the denominator, a Taylor expansion is performed up to the first order in

, which keeps all the

’s in the numerator. With these modifications, the system of equations and the Hamiltonian constraint are rewritten in such a way that they contain only terms up to the first order in

, allowing for the determination of numerical solutions for the variables

,

, and

. These equations are given by:

and the constraint

is:

This system of equations describes the temporal evolution of the commutative variables

,

, and

. These variables are related to the physical variables, the scale factor

and the anisotropy parameter

, according to the transformations in Equation (

17). Furthermore, the equations are highly coupled and non-linear, with the presence of terms involving

, which adjust the effects of anisotropy and corrections to the expansion of the universe. The constraint

represents an additional condition that must be satisfied for the system to be consistent. In the rest of this section we numerically solve these Equations (

32)–(

35) for many different values of the parameters

and

C, we also tested different initial conditions and let them evolve for many different periods of time, both for

and

. The results displayed in the following Figures and Tables are examples that show in a nice way the conclusions we obtained in our numerical studies.

4.1. For the Case of

The system of Equations (

32)–(

35), corresponding to case

, which represents a BIII cosmological model with open spatial curvature, was numerically solved due to the intrinsic complexity of the expressions involved. To this end, the initial conditions

,

,

,

, and

were specified, along with the values of the NC parameter

and the integration constant

C. Then it was verified that these initial values satisfied the dynamical constraint

, as required by the Hamiltonian formalism. This constraint must hold for all times

t, ensuring the consistency of the system’s evolution within the canonical framework.

In practice, the procedure was carried out by treating

as a free variable while fixing the other parameters, adjusting its value so that Equation (

35) was fulfilled. Alternatively, if

was chosen instead as fixed, the constant

C was determined accordingly to satisfy the constraint. The choice between treating

C or

as the adjustable parameter is arbitrary and does not affect the validity or generality of the numerical solution obtained.

The numerical solutions for the variables

,

, and

enable the reconstruction of the physical variables through the transformations defined in (

17). These are the scale factor

, which characterizes the expansion of the universe, and the anisotropy parameter

, which encodes the anisotropic features present in the early stages of cosmic evolution. A detailed analysis of the behavior of these physical variables will be presented in the following sections. The graphs that we are going to present are examples that show the general behavior of the solutions in a clear way. In these examples, we choose the numerical values of the parameters and initial conditions to show the different behaviors in the clearest way.

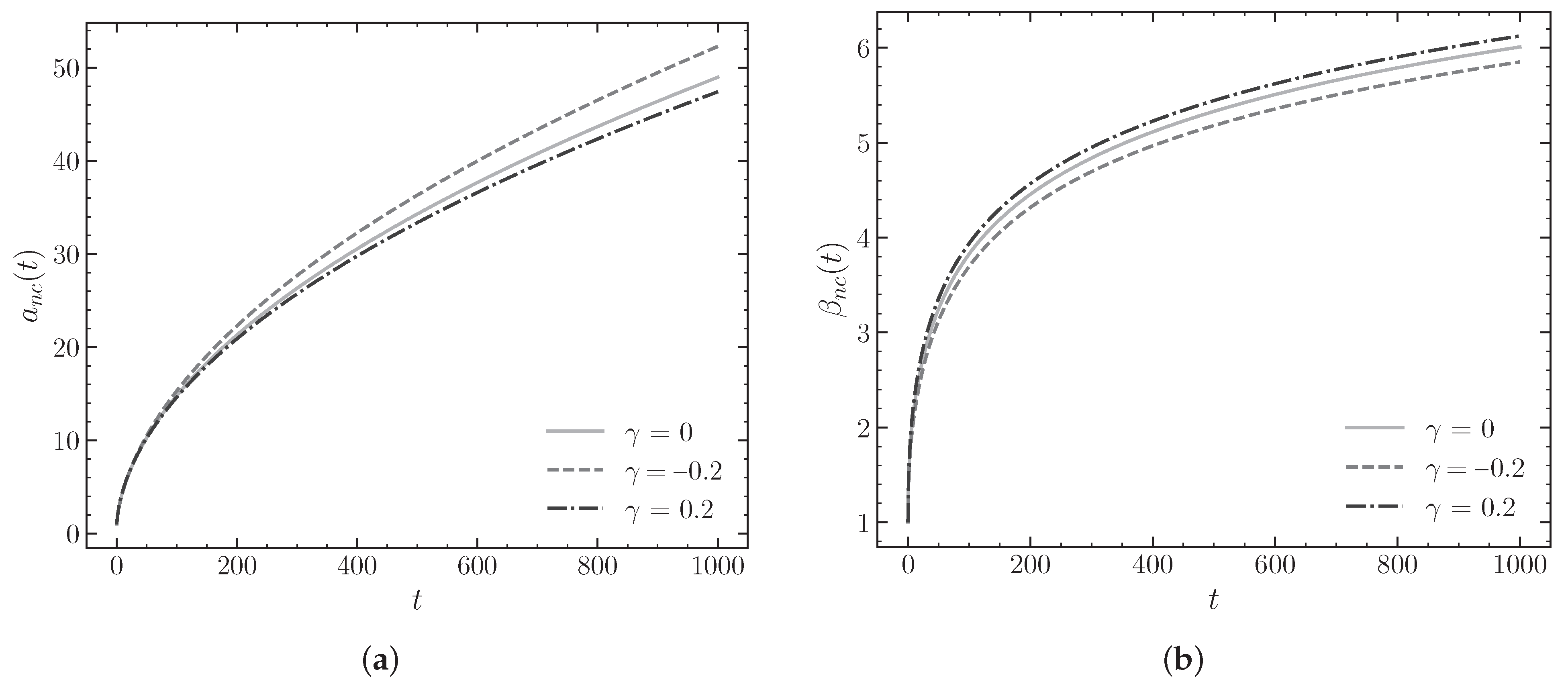

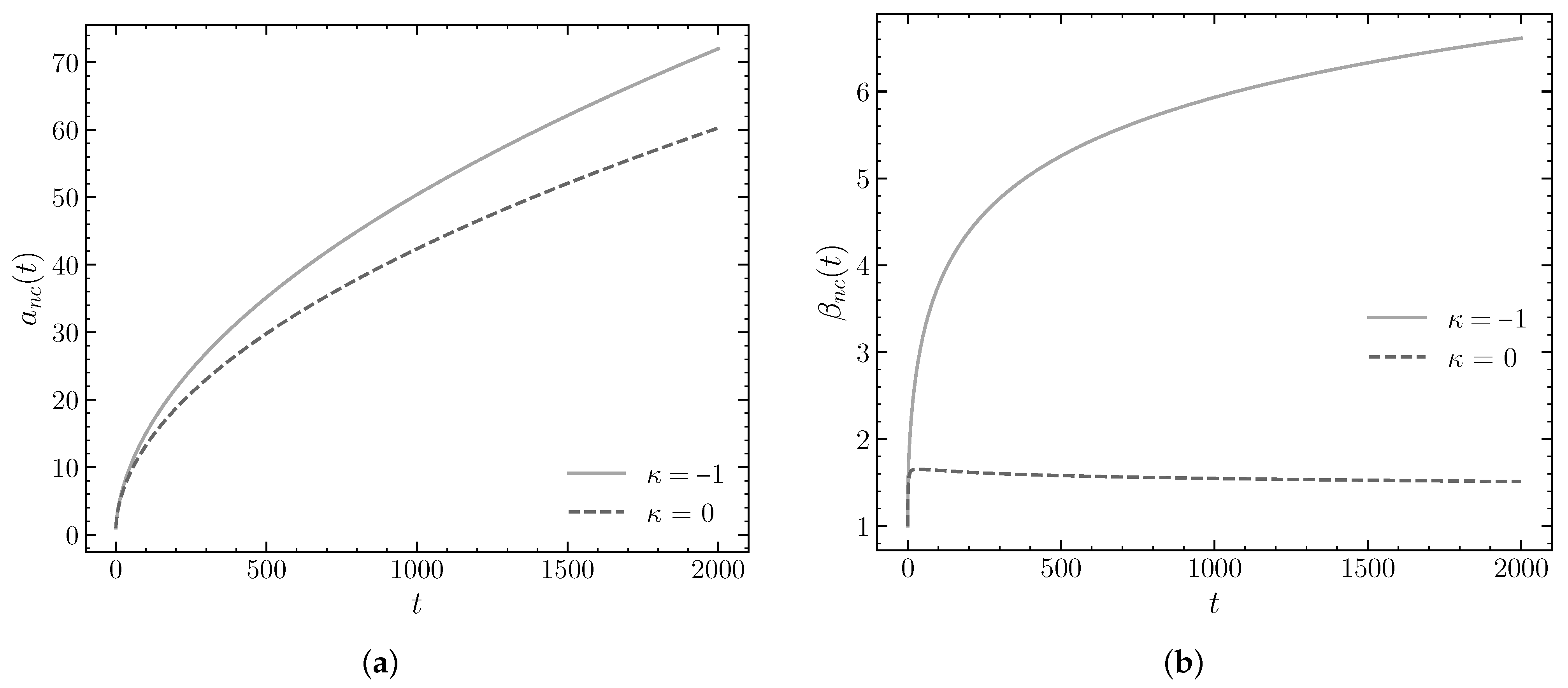

4.1.1. Varying the NC Parameter

In

Figure 1, an analysis of the effect of the NC parameter

on the evolution of the scale factor

and the anisotropy parameter

is initiated. In

Table 1, numerical data on its behavior at different time instants are presented, showing how the different values of

influence the expansion of the universe and the stabilization of anisotropy in later times.

Specifically, with respect to the evolution of the scale factor

, we observe from

Figure 1a that the solutions are always expansive. On the other hand, depending on the value of the NC parameter

, we identify a subtle but noticeable effect. From

Table 1, we observe that: for

100,000, the scale factor reaches the value of

when

,

when

, and

when

. These results indicate that a negative value of

slightly increases the expansion, while a positive value of

slightly reduces it. Therefore, the expansion rate is slightly more pronounced for negative values of

, suggesting that the parameter influences the rate of growth of the universe.

Regarding the anisotropy parameter

, we observe from

Figure 1b that this parameter shows rapid growth in the initial stages, followed by stabilization toward a more stable value that varies with

. From

Table 1, we observe that: for

100,000, the obtained values are

for

,

for

, and

for

. These results show that a positive value of

slightly increases the residual anisotropy, while a negative value of

reduces it. Furthermore, the rate of change

decreases progressively over time, indicating that the anisotropy tends to a constant in the late-time regime. For

100,000, the values of

are

for all cases, confirming that the evolution of anisotropy becomes practically negligible at late times, regardless of the value of

.

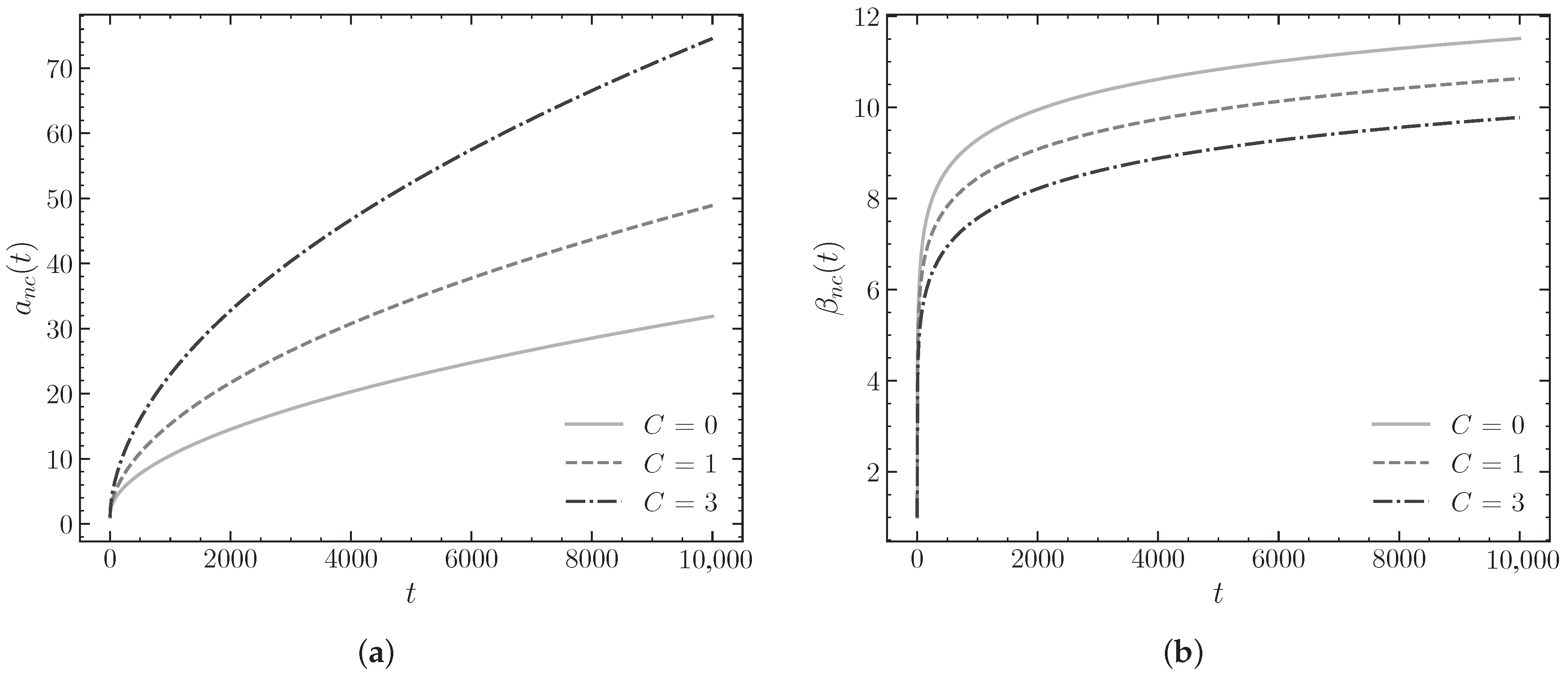

4.1.2. Varying the Energy Density C

Next, the effect of varying the energy density

C is studied. As shown in

Figure 2a, an increase in

C leads to a more accelerated growth of the scale factor

, indicating that a higher energy density in the system significantly influences the rate of expansion of the universe. This effect becomes particularly evident in later times, where the curves clearly separate and highlight a strong dependence of expansion on the value of

C. Regarding the evolution of anisotropy

, we observe from

Figure 2b that this parameter shows rapid growth in the early stages, followed by a smooth stabilization toward an asymptotic regime. Furthermore, as

C increases, the value of anisotropy decreases.

The numerical analysis presented in

Table 2 shows that for

100,000, the scale factor reaches a value of

when

, and

when

, confirming that higher values of

C significantly intensify the expansion of

. On the other hand, the anisotropy parameter

tends to stabilize at finite values of

for

and

for

, indicating that the anisotropy does not disappear, but its magnitude reduces as the energy density increases. Furthermore, the rate of change

decreases rapidly over time, reaching values on the order of

at

100,000 in both cases. This suggests that anisotropy evolves toward an equilibrium state as time progresses, although the value at which it stabilizes depends on the value of

C.

4.2. For the Case of

In this case, the system of Equations (

32)–(

35) was solved for a BI cosmological model with no curvature, specifically

, using the same approach as in the previous subsection. The initial conditions

,

,

,

, and

were defined, together with the values of the parameters

C and

, to ensure that the restriction due to Equation (

35) was satisfied. Based on the numerical solutions obtained for the commutative variables

,

, and

, the physical variables related to the expansion of the universe,

, and the anisotropy parameter,

, were calculated. Then, a detailed analysis of these physical variables was carried out, including their asymptotic behavior and consistency with an isotropic radiation-dominated universe. The graphs that we are going to present are examples that show the general behavior of the solutions in a clear way. In these examples, we choose the numerical values of the parameters and initial conditions to show the different behaviors in the clearest way.

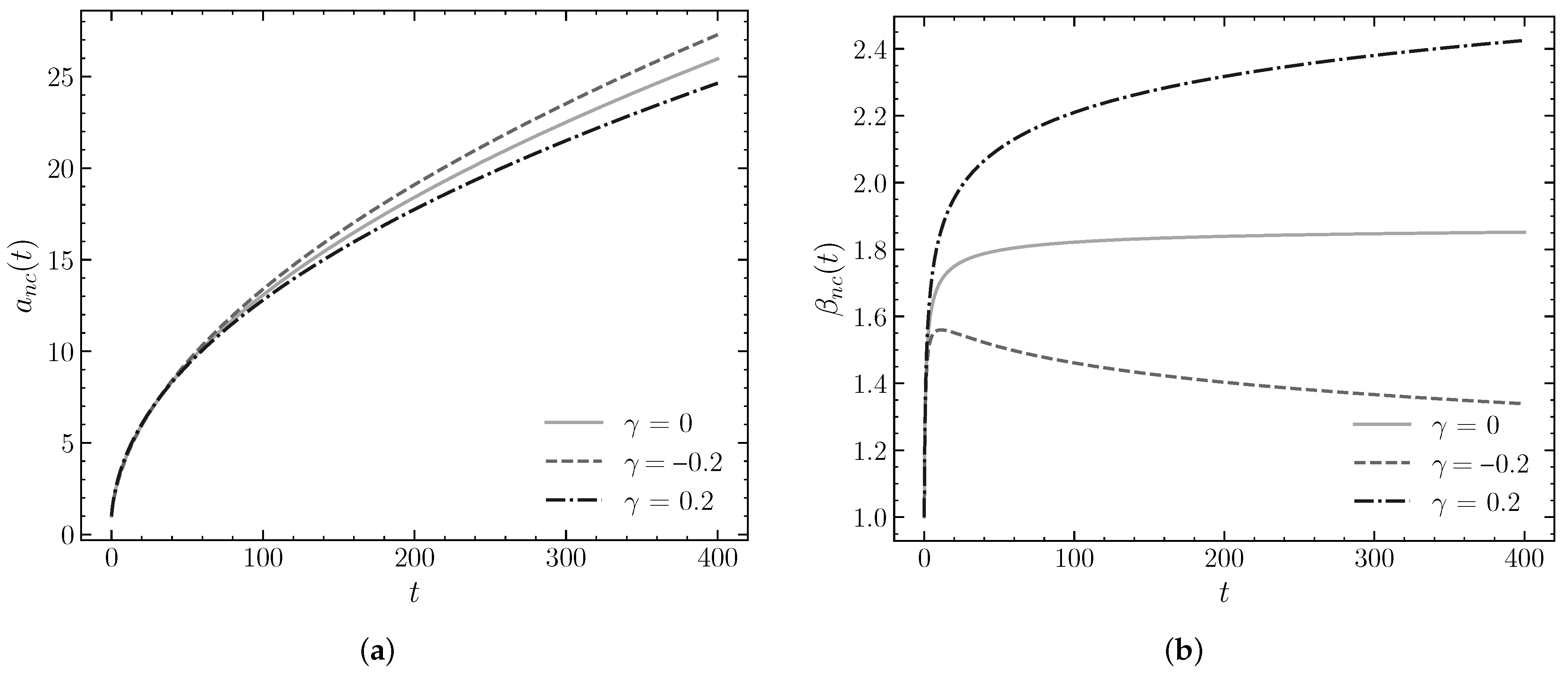

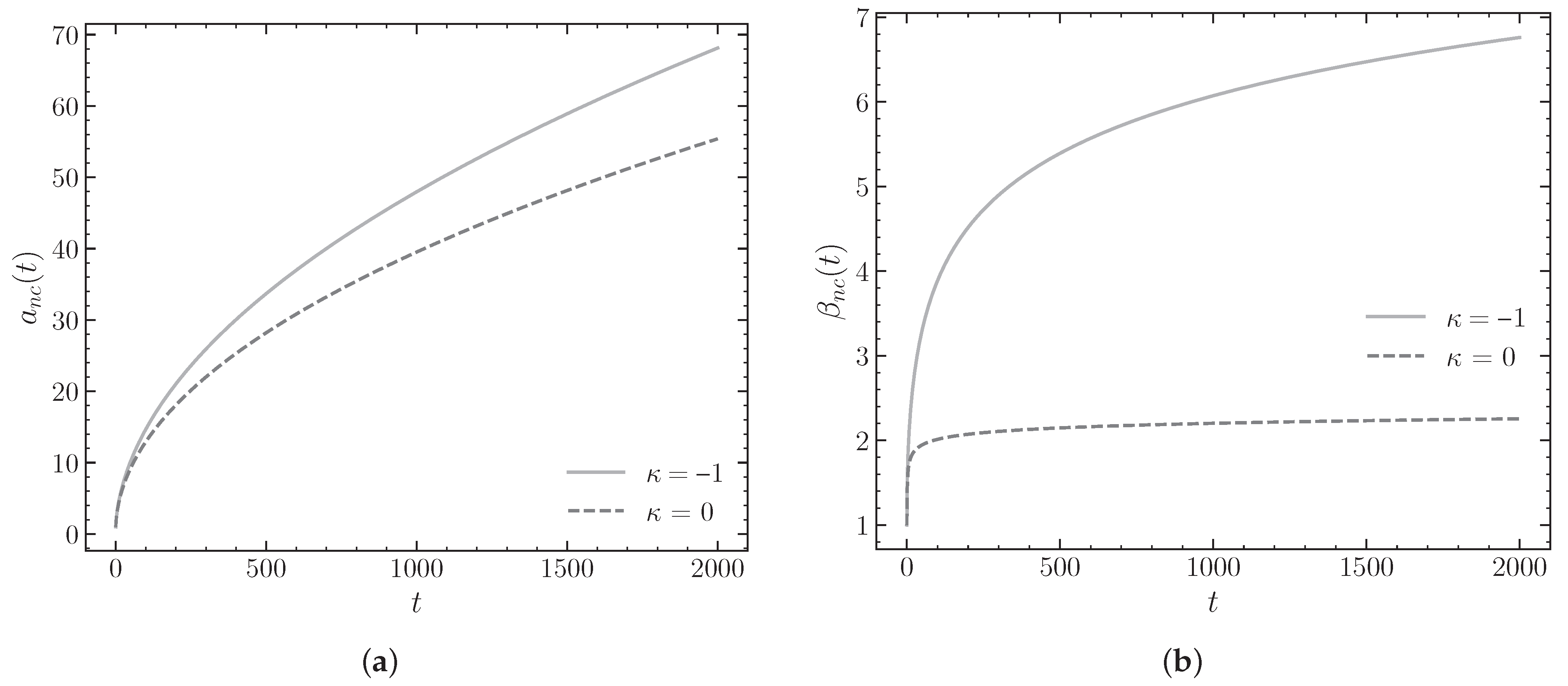

4.2.1. Varying the NC Parameter

To begin the analysis of the flat model

, the impact of the NC parameter

on the evolution of the scale factor

and the anisotropy parameter

is studied, as shown in

Figure 3, along with the numerical results presented in

Table 3. These results illustrate how different values of

influence both the expansion rate of the universe and the stabilization of anisotropies at later times.

In particular, regarding the evolution of the scale factor

, it is observed that the presence of the NC parameter

modifies the expansion dynamics of the universe. Although all cases show an accelerated growth, the expansion is more pronounced for

, while it is slightly smaller for

, compared to the commutative case

. From

Table 3, we observe that for

100,000, the scale factor reaches a value of

when

,

for

, and

for

. These results indicate that negative values of

increase the expansion rate, while positive values tend to reduce it, confirming that the

parameter has a significant effect on the evolution of

. The parameter

encapsulates geometric deformations that modify the dynamic equations of the early universe, affecting the expansion rate even in the absence of additional exotic components.

Regarding the anisotropy parameter

, its behavior follows the expected pattern: rapid growth in the initial stages, followed by stabilization toward an asymptotic value. From

Table 3, we observe that the final value of

in

100,000 is approximately

for

,

for

, and

for

. This confirms that positive values of

lead to higher residual anisotropy, while negative values favor greater isotropization.

Furthermore, the time derivative

decreases over time in all cases, confirming that the anisotropy tends to stabilize at late times. Again, from

Table 3, we see that for

100,000, the values obtained are

for

,

for

, and

for

. The lowest rate of change is observed in the commutative case, indicating that the anisotropy is nearly stabilized. In contrast, for

, although the variation is small, anisotropy takes longer to reach its asymptotic state.

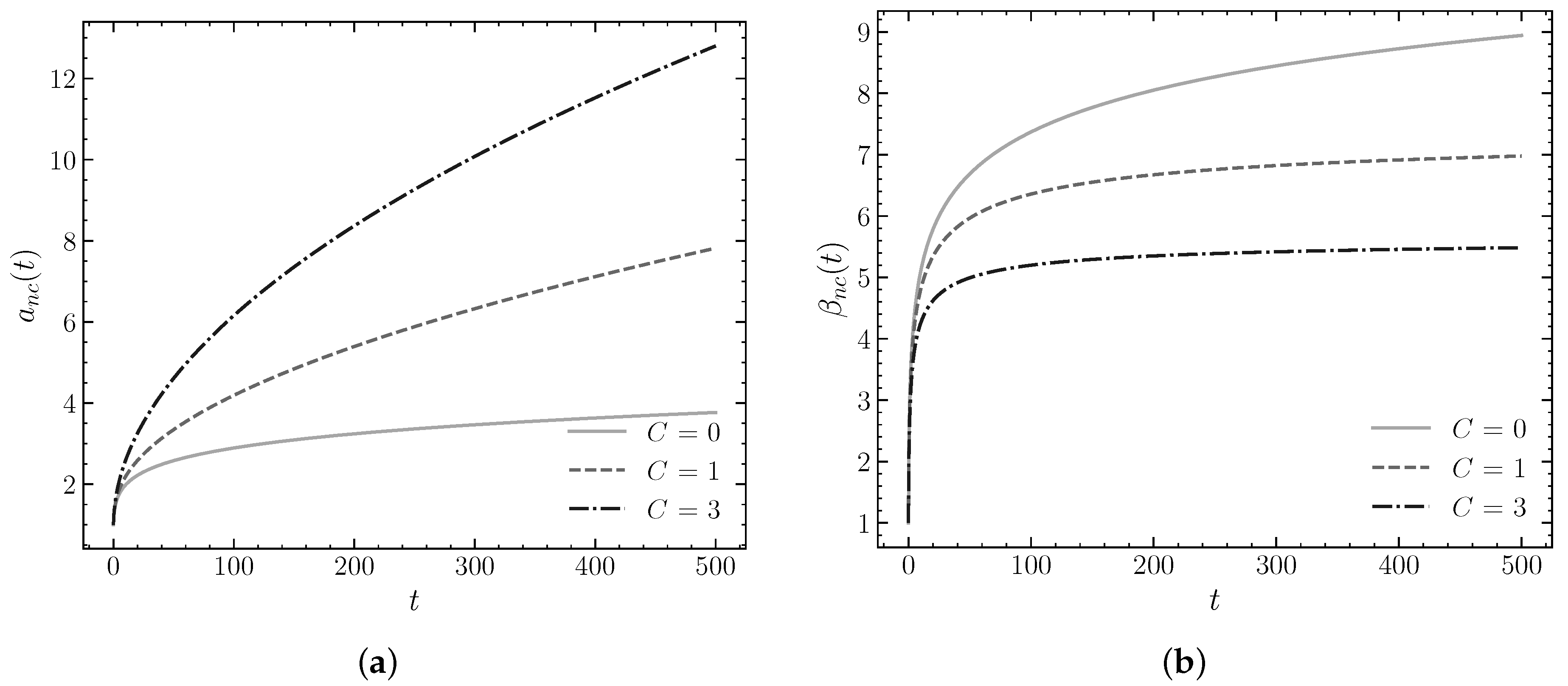

4.2.2. Varying the Energy Density C

Once the effect of the parameter

has been explored, the impact of the energy density parameter

C on the dynamics of the system is examined. As shown in

Figure 4, a higher value of

C increases the growth of the scale factor

, suggesting that the energy density of the system significantly influences the expansion rate of the universe. Regarding the evolution of the anisotropy parameter

, it shows rapid growth in the initial stages, followed by stabilization toward an asymptotic value, indicating that the universe reaches a more stable isotropic state after some time. Furthermore, as

C increases, the asymptotic value of

decreases.

The numerical analysis of these results, presented in

Table 4, shows that for

100,000, the scale factor reaches a value of

when

, and

when

, confirming that higher values of

C lead to a more pronounced expansion of the scale factor

. On the other hand, the anisotropy parameter

tends to asymptotic values of

for

and

for

, highlighting the influence of the energy density on the evolution of anisotropy. This behavior indicates that anisotropy does not disappear completely, but rather converges toward finite values in the asymptotic regime. Moreover, the time derivative of the anisotropy parameter,

, decreases rapidly with time, reaching values on the order of

for

and

for

. These results suggest that a higher energy density accelerates the isotropization process of the model, promoting a more efficient evolution toward a dynamic equilibrium state.

4.3. For the Case of

In contrast to the solutions of the system of Equations (

32)–(

35) for

and

, corresponding to the BI and BIII cosmological models, respectively, the solution for

, associated with the Kantowski-Sachs cosmological model, exhibits dynamic features of gravitational collapse. In particular, this model does not show sustained expansive behavior in its scale factor, and its anisotropy parameter does not tend toward isotropy in the asymptotic regime during the radiation era. For these reasons, the numerical analysis of the solution corresponding to

falls outside the scope and interest of the present work, which focuses on models that tend toward isotropic and expansive evolution.

4.4. Influence of Spatial Curvature on NC Dynamics

Here, we compare how different spatial curvatures, specifically flat () and open () geometries, affect the evolution of the universe under the influence of a NC parameter . Both negative and positive values of are considered.

4.4.1. Case of Negative NC Parameter ()

Following the detailed analysis of the cases with

and

, presented in

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2, respectively, we now proceed to a direct comparison between both scenarios. This comparison focuses on the regime

, with the aim of clearly visualizing the dynamical differences induced by spatial curvature. In particular, the evolution of both the scale factor and the anisotropy parameter is evaluated together.

The results in

Figure 5 indicate that the inclusion of a negative curvature improves the universe’s expansion and substantially modifies the anisotropic behavior. The scale factor

exhibits an accelerated growth in both cases, though with a significantly higher rate when

, suggesting that the open curvature acts as an amplifier of the expansive effect generated by noncommutativity. Meanwhile, the anisotropy parameter

, which tends to stabilize in the flat case, continues to grow under negative curvature, even at a decreasing rate. This behavior suggests that open geometry not only supports expansion but also delays the isotropization of the universe, extending the presence of anisotropies in the

regime.

4.4.2. Case of Positive NC Parameter ()

After analyzing the dynamical behavior of the model for

in

Figure 6, it is observed that the inclusion of negative spatial curvature (

) continues to exert an amplifying effect on the expansion of the universe, although to a smaller extent than in the

regime. The scale factor

grows in both scenarios, but reaches significantly higher values in the presence of negative curvature, suggesting that this type of geometry improves the expansion rate even when the positive NC parameter tends to reduce it. On the other hand, the anisotropy parameter

exhibits a notably different behavior in each case: while in the flat model (

) anisotropy stabilizes at late times, in the

case it continues to grow, reaching much higher values. This result indicates that the combination of open geometry and noncommutativity with

obstructs the isotropization process, prolonging the presence of anisotropies in the universe over time.

5. Estimations of the NC Parameter Value with Observational Data

In this section, we estimate the value of the parameter

using current observational data. This choice is motivated by the fact that it is easier to obtain good observational data of some cosmological parameters, needed for the estimations of

, for the present age rather than the early age of the Universe. Therefore, we decided to compute the estimations of

during the matter dominated universe. Another important motivation is that, during the matter dominated universe, we may assume that isotropization already took place, which simplifies the equations. To this end, we employ the NC Hamiltonian given in Equation (

13) of the model corresponding to

, which describes an open universe in the context of Bianchi III. Our choice to consider a BIII instead of a BI model is due to the fact that, as far as we know, it is the first time the NC deformations of BIII cosmologies are explored. Initially, we assume the conditions of isotropy and homogeneity for the current Universe, implying that

and its associated canonical momentum

. Within this framework, we consider that the observed accelerated expansion is entirely attributed to the presence of

, which plays a crucial role in the dynamics of the Universe. Under these conditions, the NC Hamiltonian of the model reduces to

Unlike the previous sections, in this section we work directly with the physical variables, that is, the NC variables. This will allow us to determine the isotropic scale factor

as a function of time. As mentioned above, in this section, we use conventional units to estimate the NC parameter

.

Starting from the NC Hamiltonian in Equation (

36), we calculate the dynamic equations using the deformed Poisson brackets described in Equations (

14)–(

16). These modified brackets allow us to obtain the time evolution of the system’s variables under the influence of noncommutativity. The resulting dynamic equations are:

We can observe that Equations (

38) and (

40) are proportionally connected through the parameter

. This connection is

This expression can be easily integrated, resulting in

where

is a constant related to the energy density of the fluid.

Since we are interested in deriving a dynamic equation for the scale factor

, we can use Equation (

37) to solve for

, which leads us to

Now, we impose the constraint

, which leads to Equation (

36) being expressed as

Then, substituting the values of

and

given in Equations (

42) and (

43), we obtain

Furthermore, in the matter-dominated phase, the constant

, and the accelerated expansion is entirely due to the presence of the NC parameter

. Thus, solving for

from the previous equation with

, we obtain

From Equation (

46), it is possible to determine a relationship between the NC scale factor

and the age of the universe

t. This is done by integrating the above equation from

to

t and

to

, where the initial conditions

and

represent, respectively, the age and the scale factor of the universe when the densities of matter and radiation were equal. The resulting relationship is

with

with

and

.

By comparing the Hubble function in the standard Friedmann–Robertson–Walker (FRW) cosmological model, given by

, with Equation (

46), we identify

and

,

(

c is the speed of light). Here,

is the density parameter of matter,

is the curvature parameter,

, and

is the Hubble constant. These values of the cosmological parameters were extracted from the 2018 Planck results [

66]. It is known from the literature that local observations produce higher values of

[

67]. This fact is called the Hubble tension. Let us compute the

estimates with the following higher value of the Hubble constant:

, and

[

67]. The choice of these two values of

, will give an idea of how sensitive are the

estimates with respect to the value of

.

To estimate the value of the NC parameter

, it is necessary to provide the value of the scale factor

and the age of the universe

Kyr corresponding to the epoch when the densities of matter and radiation were equal [

68]. Additionally, the values of the scale factor at another moment in the history of the universe,

, and the age of the universe

associated with that scale factor must also be provided. These will be determined using a “cosmological calculator” for an open-curvature universe (

) [

69]. This “cosmological calculator” computes for given values of

,

, and the redshift

z (or scale factor) the corresponding age of the universe, by solving a Friedmann equation for a FRW spacetime with

, coupled to a dust perfect fluid. The choice of considering an open-curvature FRW spacetime instead of a flat FRW spacetime, resulted in smaller values for the age of the universe for a given scale factor or redshift. In particular, for

(or

) the “cosmological calculator” gives

Gyr (for

) and

Gyr (for

), instead of the value

Gyr, which would be obtained under the same conditions from a Friedmann equation for a flat FRW spacetime. Finally, substituting these values into Equation (

47), the estimated value of the NC parameter can be obtained for the model. In

Table 5, we present the estimated values of

.

In

Table 5, it is observed that as the scale factor decreases to smaller values, the age of the Universe also decreases. Similarly, the parameter

steadily increases with the decrease of

and the age of the universe

t. This behavior suggests that the NC effects represented by

are more significant during the early stages of the evolution of the Universe and decrease as the Universe expands. This result is exactly what we expected and can be qualitatively compared with other results already published in the literature [

48,

49,

50,

51]. It is also clear from

Table 5 that the estimated values of

increase with increasing

.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The results obtained in this study provide a new perspective on the evolution of the universe in Bianchi I and Bianchi III cosmological models, incorporating an NC parameter . This parameter, which extends the classical geometry of phase space into an NC context, has a significant impact on the dynamics expansion of the universe. It is observed that, for , the expansion of the universe is increased compared to the commutative case (), while for , the expansion is slightly reduced. This behavior can be attributed to the correction introduced by the term to the scale factor , which effectively modifies the value of the NC scale factor. Although this term does not represent a force in the physical sense, it reflects how the structure of the NC phase space alters the geometry and, therefore, the dynamics of the expansion. Thus, in the context of the model, the negative values of tend to amplify the expansion, while positive values attenuate it, suggesting that the effects of noncommutativity can significantly influence cosmic evolution without resorting to additional exotic energy terms.

This finding suggests that the NC model could be a viable alternative to the cosmological constant , as both parameters have similar effects on the expansion of the universe, although with important differences in their dynamics. In particular, the presence of significantly affects the temporal evolution of the anisotropy . In the flat curvature model (Bianchi I), favors the isotropization of the universe, which is comparable to the behavior observed with a positive cosmological constant (). However, in the negative curvature model (Bianchi III), the anisotropy persists for a longer time, which could be explained by the influence of negative curvature, which slows down the isotropization of the universe.

The increase in energy density C also shows a more accelerated expansion of the universe, which is consistent with standard cosmological theory. Moreover, the estimated values of for a homogeneous and isotropic universe indicate that this parameter was more relevant in the early stages of the universe, matching the values predicted by previous studies. This behavior underscores the dynamic nature of noncommutativity in the cosmological context, especially in the early phases of the universe.

Regarding the estimation of

, it was found that the current values of this parameter are small, with

, indicating that the influence of noncommutativity has diminished over time in a homogeneous and isotropic universe. However, the values of

were slightly higher during the early stages of the universe, as shown in the simulated results. This behavior is expected, as noncommutativity should have had greater relevance in the early moments when the universe was denser and spatial scales were smaller. This ‘evolution’ of

qualitatively agrees with the values estimated by other studies, reinforcing the validity of this model in describing the evolution of the early universe [

48,

49,

50,

51]. Another important result obtained from

Table 5 is that the estimated values of

increase with increasing

.

In conclusion, noncommutativity may provide a powerful tool for explaining cosmic acceleration and the early evolution of the universe, opening new avenues for understanding phenomena such as accelerated expansion and isotropization in different cosmological models. This study suggests that in certain contexts, noncommutativity could act as an alternative to the cosmological constant , offering a distinct way of modelling the expansion of the universe in its early stages.