Metabolomic Analysis of Aqueous Humor to Predict Glaucoma Progression and Overall Survival After Glaucoma Surgery—The MISO II Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Ethics Statement

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

| POAG (n = 19) | NTG (n = 15) | ALL (n = 34) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72 | 70 | 71 |

| Female n (%) | 11 (58) | 13 (87) | 24 (70) |

| Smoking n (%) | |||

| No | 12 (63) | 8 (53) | 20 (59) |

| Current | 2 (11) | 3 (20) | 5 (15) |

| Previous | 5 (26) | 4 (27) | 9 (26) |

| Main systemic diseases | |||

| Arterial hypertension n (%) | 9 (47) | 8 (53) | 15 (50) |

| Hyperlipidemia n (%) | 6 (32) | 5 (33) | 11 (33) |

| Heart surgery n (%) | 3 (16) | 1 (7) | 4 12) |

| Transient ischemic attack n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Migraine n (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (7) | 2 (6) |

| Cancer n (%) | 1 (5) | 3 (20) | 4 (12) |

| Psoriasis n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis n (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (7) | 2 (6) |

| Thyroid disease n (%) | 1 (5) | 3 (20) | 4 (12) |

| Ocular characteristics | |||

| Previous surgery n (%) | |||

| Trabeculectomy | 8 (42) | 13 (87) | 21 (62) |

| XEN gel stent® | 9 (47) | 2 (13) | 11 (32) |

| Phacoemulsification | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) |

| Surgery during trial n (%) | |||

| Phacoemulsification | 7 (37) | 5 (33) | 12 (35) |

| Previous laser n (%) | |||

| YAG iridotomy | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| YAG capsulotomy | 1 (5) | 2 (13) | 3 (9) |

| Selective laser trabeculoplasty | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| IOP lowering meds n (%) | 18 (95) | 14 (93) | 32 (94) |

| PGA n (%) | 16 (84) | 13 (87) | 29 (85) |

| BB n (%) | 3 (16) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) |

| CAI n (%) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| AA n (%) | 2 (10) | 2 (13) | 4 (12) |

| BB_PGA n (%) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| BB_CAI n (%) | 12 (63) | 13 (87) | 25 (74) |

| BB_AA n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| AA_CAI n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| CAI oral n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

3.2. Systemic Medication Use

| Systemic Medication | POAG (n = 19) | NTG (n = 15) | ALL (n = 34) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium supplements n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Magnesium supplements n (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (7) | 2 (6) |

| Vitamin D supplements n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Allopurinol n (%) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) |

| Antihistamine n (%) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Steroid n (%) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) |

| Anticoagulant n (%) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) |

| Aspirin n (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (7) | 2 (6) |

| Statin n (%) | 6 (32) | 4 (27) | 10 (29) |

| Antihypertensives n (%) | 9 (47) | 8 (53) | 17 (50) |

| BB n (%) | 4 (21) | 4 (27) | 8 (24) |

| CCB n (%) | 3 (16) | 3 (20) | 6 (18) |

| ACEI n (%) | 3 (16) | 3 (20) | 6 (18) |

| ARB n (%) | 3 (16) | 2 (13) | 5 (15) |

| Diuretics n (%) | 4 (21) | 2 (13) | 6 (18) |

| Thyroid hormone n (%) | 1 (5) | 2 (13) | 3 (9) |

| SSRI n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 2 (6) |

| Benzodiazepines n (%) | 2 (11) | 2 (13) | 4 (12) |

| Proton pump inhibitors n (%) | 5 (26) | 1 (7) | 6 (18) |

3.3. Metabolic Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Glutamate—A (Toxic) Metabolic Hub in the Excitatory Synapse

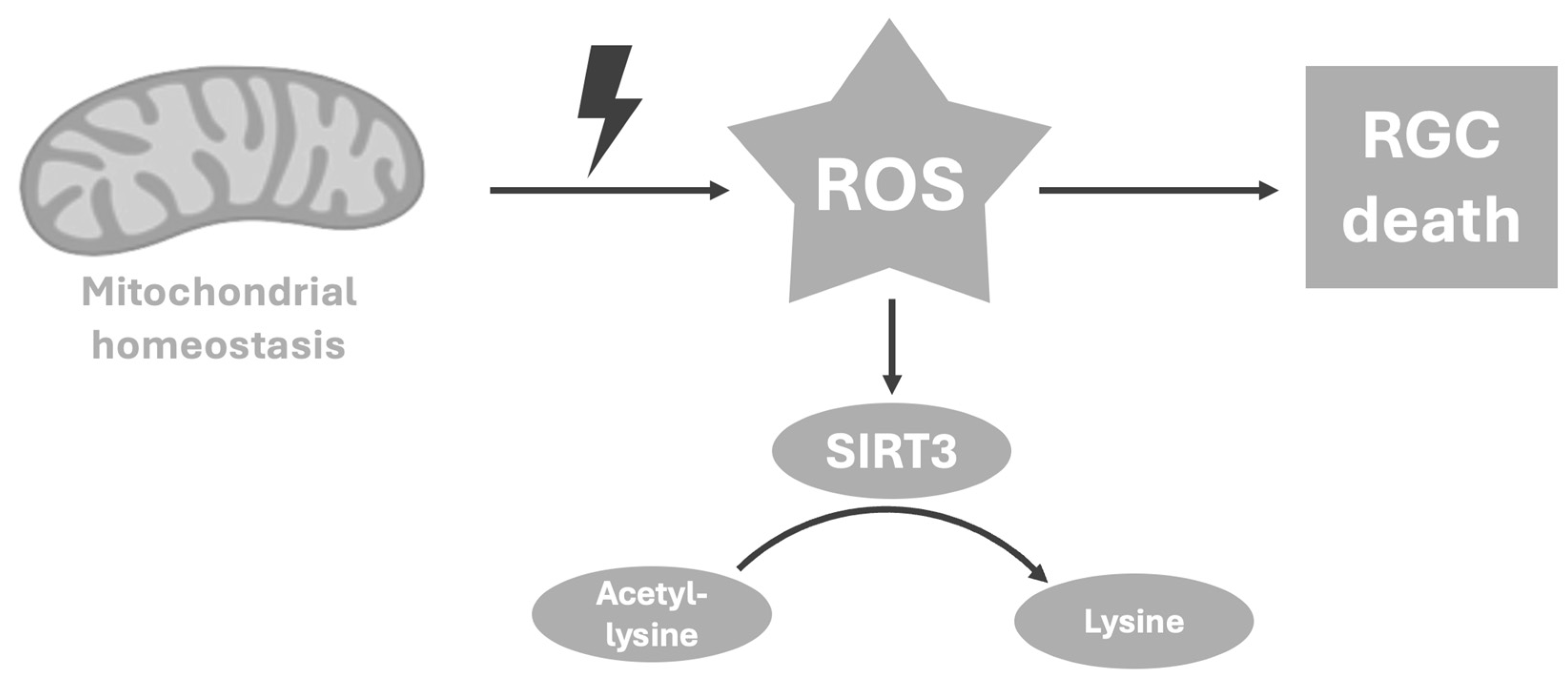

4.2. Lysine—A Reflector of Mitochondrial Hemostasis

4.3. Creatine—A Possible Neuroprotector as a Counterreaction Against Oxidative Stress

4.4. Methionine—A Circulating Precursor Linked to Metabolic and Vascular Disease

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MISO | The Metabolomics In Surgical Ophthalmological Patients Study |

| AH | Aqueous humor |

| IOP | Intraocular pressure |

| OHT | Ocular hypertension |

| POAG | Primary open-angle glaucoma |

| NTG | Normal tension glaucoma |

| VF | Visual field |

| MD | Mean deviation |

| NMDARs | N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors |

| RGCs | Retinal ganglion cells |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| HD | Huntington’s disease |

| NF-kB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer |

| COX-2 | Cucmppcygenase-2 |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| GS | Glutamine synthetase |

| PAG | Phosphate-activated glutaminase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SIRT | Sirtuin |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

References

- Tham, Y.C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.Y. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, N.N.; Núñez-Álvarez, C.; Joglar, B.; Del Olmo-Aguado, S. Glaucoma: Focus on mitochondria in relation to pathogenesis and neuroprotection. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 787, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa Breda, J.; Croitor Sava, A.; Himmelreich, U.; Somers, A.; Matthys, C.; Rocha Sousa, A.; Vandewalle, E.; Stalmans, I. Metabolomic profiling of aqueous humor from glaucoma patients—The metabolomics in surgical ophthalmological patients (MISO) study. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 201, 108268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buisset, A.; Gohier, P.; Leruez, S.; Muller, J.; Amati-Bonneau, P.; Lenaers, G.; Bonneau, D.; Simard, G.; Procaccio, V.; Annweiler, C.; et al. Metabolomic Profiling of Aqueous Humor in Glaucoma Points to Taurine and Spermine Deficiency: Findings from the Eye-D Study. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayanan, G.; Nabanita, H.; Singh, S.B.; Jayasundar, R. Untargeted metabolomics in the aqueous humor reveals the involvement of TAAR pathway in glaucoma. Exp. Eye Res. 2023, 234, 109592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo, A.; Marin, S.; Serrano-Marín, J.; Binetti, N.; Navarro, G.; Cascante, M.; Sánchez-Navés, J.; Franco, R. Targeted Metabolomics Shows That the Level of Glutamine, Kynurenine, Acyl-Carnitines and Lysophosphatidylcholines Is Significantly Increased in the Aqueous Humor of Glaucoma Patients. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 935084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, C.; Perez, J.; Abdelrahman, L.; Mendez, R.; Khattri, R.B.; Junk, A.K.; Bhattacharya, S.K. Differentiation of soluble aqueous humor metabolites in primary open angle glaucoma and controls. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 194, 108024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulukool, S.K.; Bhagavatham, S.K.S.; Kannan, V.; Sukumar, P.; Dandamudi, R.B.; Ghaisas, S.; Kunchala, H.; Saieesh, D.; Naik, A.A.; Pargaonkar, A.; et al. Elevated dimethylarginine, ATP, cytokines, metabolic remodeling involving tryptophan metabolism and potential microglial inflammation characterize primary open angle glaucoma. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Kong, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Tang, G.; Wu, J.; Sun, X. Metabolomic Profiling of Aqueous Humor and Plasma in Primary Open Angle Glaucoma Patients Points Towards Novel Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategy. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 621146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Shah, S.; Cho, K.-S.; Sun, X.; Chen, D.F. Metabolomics in Primary Open Angle Glaucoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 835736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monu, M.; Kumar, B.; Asfiya, R.; Nassiri, N.; Patel, V.; Das, S.; Syeda, S.; Kanwar, M.; Rajeswaren, V.; Hughes, B.A.; et al. Metabolomic Profiling of Aqueous Humor from Glaucoma Patients Identifies Metabolites with Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Potential in Mice. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.V.; Markussen, K.H.; Jakobsen, E.; Schousboe, A.; Waagepetersen, H.S.; Rosenberg, P.A.; Aldana, B.I. Glutamate metabolism and recycling at the excitatory synapse in health and neurodegeneration. Neuropharmacology 2021, 196, 108719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa-Breda, J.; Himmelreich, U.; Ghesquière, B.; Rocha-Sousa, A.; Stalmans, I. Clinical Metabolomics and Glaucoma. Ophthalmic Res. 2018, 59, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, E.B.; Zurakowski, D.; Schumer, R.A.; Podos, S.M.; Lipton, S.A. Elevated glutamate levels in the vitreous body of humans and monkeys with glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1996, 114, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayordomo-Febrer, A.; López-Murcia, M.; Morales-Tatay, J.M.; Monleón-Salvado, D.; Pinazo-Durán, M.D. Metabolomics of the aqueous humor in the rat glaucoma model induced by a series of intracamerular sodium hyaluronate injection. Exp. Eye Res. 2015, 131, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bak, L.K.; Schousboe, A.; Waagepetersen, H.S. The glutamate/GABA-glutamine cycle: Aspects of transport, neurotransmitter homeostasis and ammonia transfer. J. Neurochem. 2006, 98, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, L.; Rothman, D.L. Glucose, Lactate, β-Hydroxybutyrate, Acetate, GABA, and Succinate as Substrates for Synthesis of Glutamate and GABA in the Glutamine–Glutamate/GABA Cycle. In The Glutamate/GABA-Glutamine Cycle; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.P.; Koutsilieri, E.; Bartl, J.; Neuen-Jacob, E.; Arzberger, T.; Zander, N.; Ravid, R.; Roggendorf, W.; Riederer, P.; Grünblatt, E. Alterations in expression of glutamatergic transporters and receptors in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2007, 11, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.A.; Gebhardt, F.M.; Mitrovic, A.D.; Vandenberg, R.J.; Dodd, P.R. Glutamate transporter variants reduce glutamate uptake in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 553.e1–553.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotte, N.H.; Andersen, J.V.; Santos, A.; Aldana, B.I.; Willert, C.W.; Nørremølle, A.; Waagepetersen, H.S.; Nielsen, M.L. Integrative Characterization of the R6/2 Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease Reveals Dysfunctional Astrocyte Metabolism. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2211–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, I.; Lu, B.; Yang, N.; Huang, K.; Wang, P.; Tian, N. The Susceptibility of Retinal Ganglion Cells to Glutamatergic Excitotoxicity Is Type-Specific. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nasser, M.N.; Mellor, I.R.; Carter, W.G. Is L-Glutamate Toxic to Neurons and Thereby Contributes to Neuronal Loss and Neurodegeneration? A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroni, D.; Tsai, J.; Mondal, D.; George, W. Attenuation of low dose methylmercury and glutamate induced-cytotoxicity and tau phosphorylation by an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in human neuroblastoma (SHSY5Y) cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2013, 28, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.J.; Han, A.R.; Kim, E.A.; Yang, J.W.; Ahn, J.Y.; Na, J.M.; Cho, S.W. KHG21834 attenuates glutamate-induced mitochondrial damage, apoptosis, and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 856, 172412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, T.N.; Yayla, M.; Halici, Z.; Cadirci, E.; Polat, B.; Kose, D. Protective effect of 5-HT7 receptor activation against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells via antioxidative and antiapoptotic pathways. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2019, 72, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yon, J.-M.; Kim, Y.-B.; Park, D. The Ethanol Fraction of White Rose Petal Extract Abrogates Excitotoxicity-Induced Neuronal Damage In Vivo and In Vitro through Inhibition of Oxidative Stress and Proinflammation. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosp, F.; Lassowskat, I.; Santoro, V.; De Vleesschauwer, D.; Fliegner, D.; Redestig, H.; Mann, M.; Christian, S.; Hannah, M.A.; Finkemeier, I. Lysine acetylation in mitochondria: From inventory to function. Mitochondrion 2017, 33, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Leem, Y.-H. The potential role of creatine supplementation in neurodegenerative diseases. Phys. Act. Nutr. 2023, 27, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.; Bhinge, A.; Chandran, V. Lysine: Is it worth more? Cytotechnology 2001, 36, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.T.; Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 2006, 443, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elson, J.L.; Herrnstadt, C.; Preston, G.; Thal, L.; Morris, C.M.; Edwardson, J.A.; Beal, M.F.; Turnbull, D.M.; Howell, N. Does the mitochondrial genome play a role in the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease? Hum. Genet. 2006, 119, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalimonchuk, O.; Becker, D.F. Molecular Determinants of Mitochondrial Shape and Function and Their Role in Glaucoma. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023, 38, 896–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, P.; Simpson, D.A.; Sambare, C.; Duffy, S.; Lechner, J.; Dastane, A.; Dervan, E.W.; Vallabh, N.; Chelerkar, V.; Deshpande, M.; et al. Whole-mitochondrial genome sequencing in primary open-angle glaucoma using massively parallel sequencing identifies novel and known pathogenic variants. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciregia, F. Mitochondria Lysine Acetylation and Phenotypic Control. In Acetylation in Health and Disease; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.N. Neuroinflammatory Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neurodegeneration in Glaucoma. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 2021, 4581909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, E.; Söderlund, K.; Timmons, J.A.; Cederblad, G.; Greenhaff, P.L. Muscle creatine loading in men. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996, 81, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sia, P.I.; Wood, J.P.M.; Chidlow, G.; Casson, R. Creatine is Neuroprotective to Retinal Neurons In Vitro But Not In Vivo. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, L.E.; Machado, L.B.; Santiago, A.P.S.A.; Da-Silva, W.S.; De Felice, F.G.; Holub, O.; Oliveira, M.F.; Galina, A. Mitochondrial Creatine Kinase Activity Prevents Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 37361–37371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastula, D.M.; Moore, D.H.; Bedlack, R.S. Creatine for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 12, Cd005225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, R.B.; Stout, J.R. Creatine in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, O.; Chen, R.W.S. Central retinal vein occlusion associated with creatine supplementation and dehydration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2021, 23, 101128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.S.P.; Oliveira, P.S.; Debom, G.N.; Da Silveira Mattos, B.; Polachini, C.R.; Baldissarelli, J.; Morsch, V.M.; Schetinger, M.R.C.; Tavares, R.G.; Stefanello, F.M.; et al. Chronic administration of methionine and/or methionine sulfoxide alters oxidative stress parameters and ALA-D activity in liver and kidney of young rats. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhitko, A.A.; Jouandin, P.; Mohr, S.E.; Perrimon, N. Methionine metabolism and methyltransferases in the regulation of aging and lifespan extension across species. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e13034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bykowski, E.A.; Petersson, J.N.; Dukelow, S.; Ho, C.; Debert, C.T.; Montina, T.; Metz, G.A.S. Identification of Serum Metabolites as Prognostic Biomarkers Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Study. Metabolites 2023, 13, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doganay, S.; Cankaya, C.; Alkan, A. Evaluation of corpus geniculatum laterale and vitreous fluid by magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients with glaucoma; a preliminary study. Eye 2012, 26, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolvatzis, C.; Tsakiridis, I.; Kalogiannidis, I.A.; Tsakoumaki, F.; Kyrkou, C.; Dagklis, T.; Daniilidis, A.; Michaelidou, A.-M.; Athanasiadis, A. Utilizing Amniotic Fluid Metabolomics to Monitor Fetal Well-Being: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Cureus 2023, 15, e36986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Chemical Shift Region | Main Metabolites | Progression; p-Value | Progression Category; p-Value | Death; p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.48–1.54 | Alanine | 0.151 | 0.243 | 0.064 |

| 2 | 1.55–1.65 | Lysine, leucine | 0.248 | 0.472 | 0.632 |

| 3 | 1.88–1.92 | N-acetylglutamateLysine | 0.242 | 0.309 | 0.048 |

| 4 | 1.93–1.95 | Acetate | 0.317 | 0.806 | 0.592 |

| 5 | 2.1–2.2 | Glutamine and glutamate | 0.081 | 0.212 | 0.038 |

| 6 | 2.22–2.25 | Valine, β-hydroxybutyrate | 0.855 | 0.373 | 0.534 |

| 7 | 2.38–2.42 | Glutamate, succinate, β-hydroxybutyrate | 0.337 | 0.171 | 0.628 |

| 8 | 2.44–2.52 | Glutamine, α-ketoglutarate | 0.030 | 0.176 | 0.019 |

| 9 | 2.5–2.8 | Citrate | 0.635 | 0.3945 | 0.954 |

| 10 | 3.05–3.1 | Lysine, creatine, phosphocreatine, creatinine, α-ketoglutarate | 0.176 | 0.605 | 0.023 |

| 11 | 3.24–3.32 | Glucose, taurine, betaine | 0.250 | 0.517 | 0.072 |

| 12 | 3.4–3.98 | Glucose and Hα of amino acids | 0.578 | 0.890 | 0.263 |

| 13 | 4.0–4.08 | β-hydroxybutyrate | 0.260 | 0.692 | 0.258 |

| 14 | 4.1–4.2 | Lactate | 0.362 | 0.843 | 0.674 |

| Region | Chemical Shift Region | Main Metabolites | Progression; p-Value | Progression Category; p-Value | Death; p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.48–1.54 | Alanine | 0.265 | 0.431 | 0.454 |

| 2 | 1.55–1.65 | Lysine, leucine | 0.456 | 0.195 | 0.555 |

| 3 | 1.88–1.92 | N-acetylglutamateLysine | 0.337 | 0.561 | 0.012 |

| 4 | 1.93–1.95 | Acetate | 0.501 | 0.831 | 0.226 |

| 5 | 2.1–2.2 | Glutamine and glutamate | 0.081 | 0.212 | 0.038 |

| 6 | 2.22–2.25 | Valine, β-hydroxybutyrate | 0.985 | 0.578 | 0.883 |

| 7 | 2.38–2.42 | Glutamate, succinate, β-hydroxybutyrate | 0.608 | 0.466 | 0.978 |

| 8 | 2.44–2.52 | Glutamine, α-ketoglutarate | 0.034 | 0.176 | 0.019 |

| 9 | 2.5–2.8 | Citrate | 0.051 | 0.204 | 0.557 |

| 10 | 3.05–3.1 | Lysine, creatine, phosphocreatine, creatinine, α-ketoglutarate | 0.358 | 0.828 | 0.085 |

| 11 | 3.24–3.32 | Glucose, taurine, betaine | 0.250 | 0.517 | 0.072 |

| 12 | 3.4–3.98 | Glucose and Hα of amino acids | 0.578 | 0.890 | 0.263 |

| 13 | 4.0–4.08 | β-hydroxybutyrate | 0.344 | 0.604 | 0.186 |

| 14 | 4.1–4.2 | Lactate | 0.689 | 0.551 | 0.924 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Detremmerie, L.; Sava, A.C.; Himmelreich, U.; Stalmans, I.; Van Eijgen, J.; Barbosa-Breda, J. Metabolomic Analysis of Aqueous Humor to Predict Glaucoma Progression and Overall Survival After Glaucoma Surgery—The MISO II Study. Metabolites 2026, 16, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16020100

Detremmerie L, Sava AC, Himmelreich U, Stalmans I, Van Eijgen J, Barbosa-Breda J. Metabolomic Analysis of Aqueous Humor to Predict Glaucoma Progression and Overall Survival After Glaucoma Surgery—The MISO II Study. Metabolites. 2026; 16(2):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16020100

Chicago/Turabian StyleDetremmerie, Laurens, Anca Croitor Sava, Uwe Himmelreich, Ingeborg Stalmans, Jan Van Eijgen, and João Barbosa-Breda. 2026. "Metabolomic Analysis of Aqueous Humor to Predict Glaucoma Progression and Overall Survival After Glaucoma Surgery—The MISO II Study" Metabolites 16, no. 2: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16020100

APA StyleDetremmerie, L., Sava, A. C., Himmelreich, U., Stalmans, I., Van Eijgen, J., & Barbosa-Breda, J. (2026). Metabolomic Analysis of Aqueous Humor to Predict Glaucoma Progression and Overall Survival After Glaucoma Surgery—The MISO II Study. Metabolites, 16(2), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16020100