1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver tumor, accounting for approximately 90% of primary liver cancers [

1]. Among all malignancies, it ranks as the sixth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related death [

2]. Its incidence and mortality are both on the rise. It is estimated that the number of annual cases will increase from around 900,000 in 2020 to approximately 1,400,000 by 2040. This rise is primarily driven by population aging, persistent exposure to risk factors, and the growing prevalence of chronic liver disease in both developed and developing countries [

3].

The development of HCC is strongly associated with advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD), which confers an annual risk of up to 2% [

4]. Historically, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections have been the predominant etiologies [

5,

6]. However, in recent years, alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) have emerged as major drivers of HCC [

7]. MASLD, formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is now recognized as a major cause of chronic liver disease globally, paralleling the worldwide epidemics of obesity and metabolic syndrome. ALD, similarly, remains a persistent and growing public health burden, especially in high-income countries with increasing alcohol consumption trends [

8,

9,

10].

The epidemiology of HCC is undergoing a substantial transition. In many regions, universal HBV vaccination and the introduction of highly effective antiviral therapies for HBV and HCV have led to a decline or stabilization of virus-related HCC incidence [

11]. At the same time, MASLD and ALDs are increasing in prevalence, positioning both as the leading causes of HCC in the near future [

11,

12]. Also, genetic predisposition further modulates disease risk in these populations. Polymorphisms in genes such as PNPLA3 (I148M), TM6SF2 (E167K), and HSD17B13 have been associated with increased susceptibility to fibrosis progression and HCC development in MASLD. This highlights the complexity and heterogeneity of MASLD-related HCC [

13].

HCC arising from MASLD and ALD frequently presents with distinct biological and clinical features compared to viral etiologies. These patients often have lower alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) secretion, more advanced tumor stages at diagnosis, higher levels of systemic inflammation, and a greater burden of metabolic comorbidities [

14,

15]. Moreover, these tumors are frequently diagnosed outside of established screening programs, reducing the likelihood of early-stage detection. This creates a substantial clinical challenge, as existing prognostic models, largely developed in viral HCC populations, may not adequately capture the unique risk profiles of MASLD- and ALD-related HCC [

16,

17].

Identifying reliable prognostic factors at the time of diagnosis is clinically critical. Early mortality in HCC is often determined not only by tumor burden but also by the underlying hepatic functional reserve, systemic inflammation, and patient performance status. Accurate risk stratification at this early stage could support individualized therapeutic strategies, better resource allocation, and improved patient counseling. It could also provide a foundation for optimizing surveillance and treatment algorithms tailored to this growing subgroup of patients.

Machine learning (ML) approaches offer a promising framework to address these challenges. Unlike traditional statistical models, which rely on predefined linear assumptions, ML algorithms can detect complex, nonlinear, and high-dimensional relationships between demographic, clinical, biochemical, and tumor-related variables [

18,

19,

20]. These capabilities make them well suited to model heterogeneous data such as that encountered in real-world hepatology. ML has been increasingly applied in liver diseases for early detection of fibrosis, noninvasive diagnosis, prognostication, and treatment outcome prediction in HCC [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Importantly, these methods can incorporate both liver function and systemic inflammation biomarkers, variables often overlooked or underweighted in conventional prognostic scores.

Among the various ML methods, the Random Forest (RF) algorithm has emerged as a particularly attractive option for clinical modeling. RF is robust to overfitting, can handle missing data and mixed variable types, and provides interpretable variable importance measures [

25,

26]. Its strong performance across diverse biomedical applications suggests that it may outperform traditional prognostic models in MASLD- and ALD-related HCC, where classical tumor markers have limited utility.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify the main risk factors associated with early mortality at diagnosis in patients with HCC secondary to ALD and MASLD, using ML-based predictive modeling. We hypothesized that markers of liver functional reserve and systemic inflammation, such as albumin levels and CRP/albumin ratio, would outperform classical tumor markers for early mortality prediction in this specific patient population. Furthermore, by comparing different ML algorithms with RF as the reference model, we sought to evaluate their predictive performance and potential applicability to routine clinical practice in this emerging and high-risk group of HCC patients.

2. Materials and Methods

This multicenter study was conducted at Virgen de la Luz Hospital in Cuenca and the University Hospital of Guadalajara, reference hospitals in their provinces. It had a retrospective design, with data collection spanning from January 2008 to December 2023. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Guadalajara, which waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the analysis.

Inclusion criteria were defined as patients over 18 years of age with a diagnosis of HCC. This diagnosis could be made either through typical imaging characteristics in patients with ACLD [

27]; or via histological confirmation in cases of diagnostic uncertainty or in patients without ACLD [

28]. Exclusion criteria included patients diagnosed at other institutions and those lacking the necessary clinical data in their medical records to fulfill the study variables.

Three categories of variables were collected and classified as follows:

This group included age, sex, date of HCC diagnosis, date of death, or date of censoring (defined as the last outpatient visit for those still alive at the end of the study period). Data were also collected on the presence of hypertension [

29], diabetes mellitus (DM) [

30], dyslipidemia (DL) [

31], active alcohol and tobacco use. The diagnosis of MASLD was based on current clinical guidelines (alcohol consumption < 140 g/week for women and <210 g/week for men) [

32]. For alcohol consumption above these thresholds, diagnosis of ALD was established [

33].

- ‑

Analytical variables:

Laboratory parameters were collected at the time of HCC diagnosis or within the first month after diagnosis. These included the white blood cell count (cells/mm3), focusing on neutrophils and total leukocytes; international normalized ratio (INR); platelet count (103/dL); bilirubin (mg/dL); aspartate aminotransferase (AST, U/L); alanine aminotransferase (ALT, U/L); alkaline phosphatase (ALP, U/L); gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) (U/L); alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) (ng/mL); creatinine (mg/dL); albumin (g/dL); sodium (mEq/L); potassium (mEq/L); and C-reactive protein (CRP).

- ‑

Tumor-related variables

Patients included in the analysis had HCC secondary to ALD or MASLD. Collected tumor-related variables included BCLC stage [

34], Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) stage [

35], Child–Pugh score, Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD), MELD-Na, MELD 3.0 [

36], TNM stage [

37], Child–Pugh score [

38], Albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score [

39], Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score [

40], AST-to-Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) [

41], presence of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) [

42], presence of ACLD [

43], and if diagnosis was established in the screening program.

RF algorithm was proposed as the reference method for this study because of its well-documented strengths in handling complex and heterogeneous biomedical data. RF is an ensemble learning technique that constructs multiple decision trees on random subsets of both the data and predictor variables, combining their outputs through majority voting. This strategy substantially reduces variance and overfitting, which are common limitations of single-tree approaches. Moreover, RF naturally accommodates both numerical and categorical variables without requiring extensive preprocessing such as scaling or transformation, making it particularly suitable for real-world clinical datasets characterized by heterogeneity and noise [

44]. While some studies have explored the application of ML in HCC, the number of publications focusing specifically on MASLD- and ALD-related HCC remains limited. To rigorously evaluate the discriminative performance of the proposed RF model, we compared it with four widely used ML algorithms representing different methodological families: Gaussian Naïve Bayes (GNB) [

45], Decision Tree (DT) [

46], Support Vector Machine (SVM) [

47] y K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) [

48]. The resulting models were developed using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA; MATLAB.Version R2025a).

Continuous variables were standardized using z-score scaling for algorithms sensitive to feature magnitude (SVM and KNN). Tree-based models (RF and DT) and GNB were trained without scaling, as their performance is not affected by variable scale. To maximize predictive performance and prevent suboptimal parameterization, hyperparameters for each algorithm were tuned using Bayesian optimization. This sequential, model-based approach iteratively identifies the most promising hyperparameter configurations by learning from previous evaluations, thereby improving efficiency and reducing computational cost [

49]. For RF, we optimized the number of trees (ranging from 50 to 500), minimum leaf size, maximum number of splits, and number of predictors sampled at each split. For SVM, kernel function (linear vs. Gaussian), box constraint, and kernel scale were tuned. KNN optimization included the number of neighbors and distance metric, while DT tuning focused on maximum splits, minimum leaf size, and split criterion (Gini vs. deviance). The following hyperparameter search spaces were defined:

Random Forest (RF):

- -

Number of trees: 50–500

- -

Maximum number of splits: 10–200

- -

Minimum leaf size: 1–20

- -

Number of predictors sampled per split: 1–√p

Support Vector Machine (SVM):

- -

Kernel function: linear or RBF

- -

Box constraint (C): 10−3 to 102

- -

Kernel scale (RBF): 10−3 to 102

k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN):

- -

Number of neighbors (k): 1–30

- -

Distance metric: Euclidean, cosine, or cityblock

- -

Neighbor weighting: uniform or distance-weighted

Decision Tree (DT):

- -

Maximum number of splits: 10–200

- -

Minimum leaf size: 1–20

- -

Split criterion: Gini or deviance

Gaussian Naïve Bayes (GNB):

- -

Variance smoothing parameter: 10−9 to 10−1

- -

Prior class probabilities: automatic or uniform

Feature importance for the RF was computed using the mean decrease in impurity (Gini importance). This method quantifies the contribution of each predictor to reducing node impurity across all splits in the ensemble, averaged over all trees. Higher values indicate variables that contribute more substantially to the model’s discriminatory performance.

Each optimization process was repeated 100 times to ensure stable mean and standard deviation estimates, thereby minimizing random variability and enhancing the reliability of model selection [

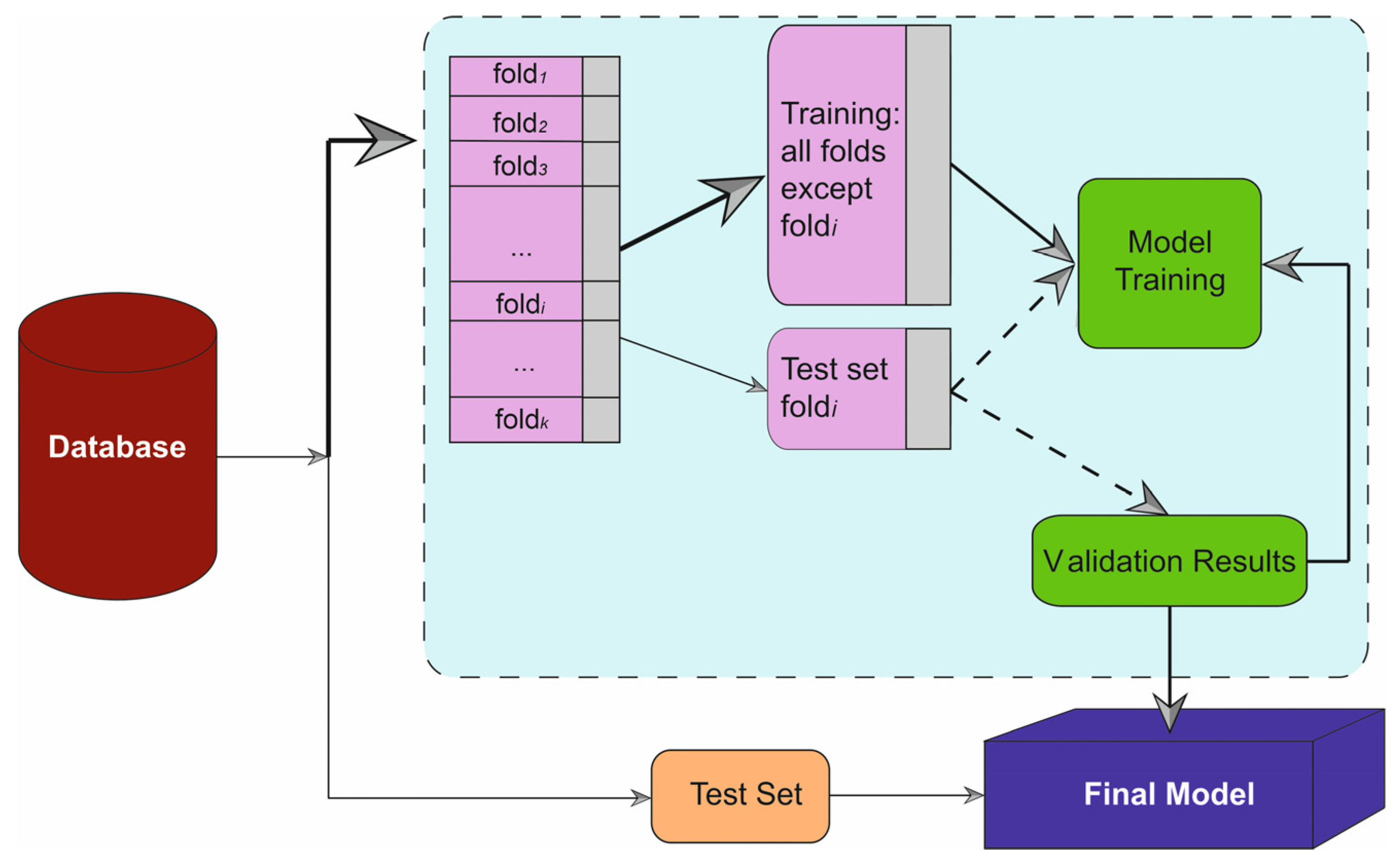

50]. A five-fold cross-validation strategy was employed to mitigate overfitting, with the dataset divided into a training set (70%) and a testing set (30%), ensuring no overlap of patient data between phases to avoid leakage (

Figure 1). Beyond discrimination, model calibration was evaluated using calibration plots and the Brier score. For each algorithm, predicted probabilities of early mortality were obtained on the independent test set. Patients were grouped into risk strata and observed event rates were plotted against mean predicted probabilities to generate calibration curves. Overall calibration performance was summarized using the Brier score, defined as the mean squared difference between predicted probabilities and the observed binary outcome (mortality vs. survival). Final model evaluation was performed on the independent test set, and all performance metrics were computed based on this validation procedure.

3. Results

Initially, a total of 219 patients were included in the study. Considering that the aim was to evaluate patients whose primary etiology of HCC was secondary to ALD or MASLD, 91 patients were ultimately analyzed. Of these, 68.13% belonged to the ALD group. Notably, alcohol was the leading cause of HCC in the entire cohort, surpassing HCV infection. A flow diagram summarizing the cohort selection process, including initial screening, exclusion criteria, and final sample size, has been added as

Figure 2. In addition,

Table 1 provides a summarized overview of the baseline characteristics of the 91 patients included in the study.

Figure 3 displays the relative importance of each predictor to the final RF mortality prediction model. Serum albumin emerged as the most influential variable, followed closely by the CRP/albumin ratio and the BCLC staging system. These findings emphasize the central role of liver functional reserve and systemic inflammation in early mortality among patients with HCC arising from ALD and MASLD. Albumin levels reflect the synthetic capacity of the liver and are also influenced by systemic inflammatory activity, making them a sensitive indicator of both hepatic reserve and disease severity. Similarly, the CRP/albumin ratio has been recognized as a composite marker that captures both the inflammatory state and nutritional status, two key prognostic domains in advanced liver disease. The BCLC stage, TNM classification, ECOG performance status, and ALBI score also demonstrated substantial weight, highlighting the relevance of tumor burden, patient functional capacity, and liver function in prognostication.

The performance of the different algorithms used is presented in the subsequent tables. These metrics were selected as they are commonly employed in scientific literature. All performance metrics are presented together with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of uncertainty. In the first table (

Table 2), values for accuracy, recall, precision, and Area Under the Curve (AUC) are shown. As observed, RF algorithm outperforms all other implemented algorithms across these metrics. RF model exceeds SVM, DT, and GNB by nearly or more than 10%. The only algorithm approaching the performance of RF is KNN. However, while RF achieves accuracy and precision values of 91.32% and 90.67%, respectively, KNN scores 87.35% and 86.73%. RF is also the only algorithm to surpass 90% in AUC.

Table 3 presents the results for the F1 score, Youden’s Dependent Index (DYI), Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), and Kappa metrics. In this case, the performance of the RF model again surpasses that of the other final models. For instance, the differences between RF and GNB, the algorithm with the poorest results, exceed 10% across all metrics. Focusing on MCC values, one of the most reliable indices due to its relationship with the four categories of the confusion matrix [

51], RF also outperforms the other models. The MCC for RF was slightly above 80%, while for SVM, the third-best performing algorithm, it was 73.03%, a clearly significant difference in favor of RF.

According to the calibration performance, the RF model achieved the lowest Brier score (0.13), indicating the best overall agreement between predicted and observed mortality risk, followed by KNN (0.15). SVM, DT, and GNB showed higher Brier scores (0.18, 0.19, and 0.21, respectively), consistent with their lower discriminative performance. Calibration plots for the test sets are shown in

Figure 4 and confirm that RF maintains the closest alignment to the ideal diagonal, whereas the other algorithms tend to under- or overestimate risk in specific probability ranges.

To provide a comprehensive visualization of all performance metrics, a radar plot was generated (

Figure 5). This figure integrates accuracy, recall, precision, AUC, specificity, F1 score, Youden’s Index, and MCC for each algorithm, enabling a global interpretation of their discriminative and calibration capacities. The upper panel corresponds to the training phase, whereas the lower panel depicts the test phase, allowing direct comparison between development and validation performance.

The RF model enclosed a nearly identical area in both phases, suggesting limited overfitting in internal validation. Nevertheless, these results derive from a single multicenter cohort, and the generalizability of the model to other populations remains to be established. This finding has important clinical implications. It indicates that the algorithm is able to maintain stable predictive performance when applied to new patients outside the training set, which is essential for any tool intended to support real-world clinical decision-making. In practice, this means that the probability of correct risk classification for an individual newly diagnosed with HCC of ALD or MASLD etiology would remain consistently high, irrespective of whether the patient belonged to the original training cohort.

Moreover, the RF model showed not only superior accuracy but also high MCC and specificity, which are key indicators of reliability in clinical predictive models. High specificity minimizes false-positive risk classifications, reducing unnecessary alarm or inappropriate escalation of care. Meanwhile, MCC value indicates that the RF model achieved balanced performance across all four categories of the confusion matrix (true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives). This is particularly relevant in HCC, where misclassification of high-risk patients could delay life-saving interventions or, conversely, lead to overtreatment in lower-risk individuals.

In contrast, the other algorithms displayed smaller and less balanced enclosed areas between training and testing phases, suggesting lower robustness and generalization capacity. This reflects a higher susceptibility to performance drops when exposed to unseen data, which could limit their clinical applicability in dynamic and heterogeneous patient populations. The strong and stable performance of the RF model across all evaluated metrics positions RF as a promising tool for early risk stratification in this specific cohort. Future external and temporal validations are needed to confirm its performance and clinical applicability in other settings.

Taken together, these findings highlight the central role of hepatic functional reserve and systemic inflammation as major determinants of early mortality in patients with HCC secondary to ALD and MASLD. The predominance of albumin and CRP/albumin ratio over conventional tumor markers underscores that, in this specific population, host factors may be more decisive than tumor burden itself in shaping short-term prognosis. The strong and stable performance of the RF model, with high accuracy, specificity, and MCC across both training and internal validation phases, supports its potential utility as a risk stratification tool in patients with HCC secondary to ALD and MASLD. Such an approach could help clinicians identify high-risk patients at the time of diagnosis, allowing earlier referral to specialized centers, closer monitoring, and more aggressive therapeutic strategies when appropriate. In parallel, patients classified as lower risk could benefit from tailored follow-up strategies, potentially optimizing resource allocation and clinical outcomes. Nonetheless, external and temporal validation in larger, independent cohorts is required before considering it a clinically reliable tool for routine practice.

4. Discussion

Although globally HBV and HCV remain the leading causes of HCC due to their endemicity in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, mainly reflecting limited vaccination programs and restricted access to antiviral therapy [

1], a paradigm shift toward metabolic and alcohol-related etiologies is underway [

52]. As antiviral coverage expands and universal HBV vaccination becomes more widespread, the incidence of viral-related HCC is expected to continue declining. In parallel, the global rise in obesity, the increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome, particularly diabetes mellitus, and growing alcohol consumption are redefining the epidemiology of this tumor [

53,

54,

55].

The recent redefinition of NAFLD to MASLD, along with the introduction of Metabolic dysfunction-associated alcohol-related liver disease (MetALD), reflects this clinical and biological transition. These new categories highlight the continuous and overlapping spectrum between metabolic dysfunction and alcohol consumption as synergistic risk factors for the development and progression of ACLD [

32,

56]. This interaction is particularly relevant because even moderate alcohol intake in patients with metabolic syndrome significantly increases the risk of developing HCC, often even in the absence of cirrhosis [

21,

57,

58,

59]. Importantly, the introduction of MetALD does not displace ALD as an etiology: chronic alcohol consumption, often underrecognized due to coexisting use disorders, continues to be one of the most important drivers of liver disease worldwide [

33]. In the United States, ALD accounts for nearly 50% of hospital deaths related to cirrhosis and over 40% of liver transplants [

60,

61]. The steady increase in alcohol use, accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, underscores the urgency of implementing preventive strategies and optimizing risk stratification in these populations [

62].

Our study highlights the prognostic significance of host- and liver-related factors in patients with HCC secondary to ALD and MASLD. Among all variables analyzed, serum albumin emerged as the strongest predictor of early mortality, closely followed by the CRP/albumin ratio, BCLC stage, and CRP itself. This pattern is particularly noteworthy, as tumor stage often dominates prognostic models, yet in this cohort markers of hepatic functional reserve and systemic inflammation outperformed traditional tumor characteristics [

63,

64]. Low albumin levels reflect not only impaired liver synthetic capacity but also the degree of systemic inflammation and nutritional status. Hypoalbuminemia has been repeatedly associated with worse outcomes in chronic liver disease, influencing both tumor progression and patient resilience to therapy [

65,

66,

67]. Similarly, the CRP/albumin ratio integrates the systemic inflammatory response with nutritional and hepatic functional status [

68,

69,

70], providing a composite marker that captures the multifactorial determinants of early mortality. The fact that these two variables rank at the top of the model emphasizes their potential clinical value for risk stratification at the time of diagnosis.

The ALBI score also demonstrated a strong predictive contribution, exceeding the performance of the Child–Pugh and MELD scores. Unlike Child-Pugh, ALBI is based exclusively on objective laboratory parameters, thereby eliminating the subjectivity associated with ascites or encephalopathy grading [

71,

72]. MELD scores, although valuable in many liver disease settings, often underestimate mortality in nonviral HCC, particularly in MASLD [

73,

74,

75]. In our cohort, MELD 3.0 performed better than classical MELD and MELD-Na, likely because of the incorporation of albumin and sex into its calculation [

76].While still inferior to albumin and CRP/albumin ratio, this finding suggests that MELD 3.0 may offer better risk stratification in patients with MASLD- and ALD-related HCC and warrants further validation in larger, external cohorts.

AFP, in contrast, was among the least relevant variables for mortality prediction at diagnosis. AFP levels in these patients may be confounded by protein-calorie malnutrition, sarcopenia, and chronic systemic inflammation, factors that are common in this population and can reduce marker sensitivity [

77]. Furthermore, MASLD-related tumors frequently exhibit lower AFP production, diminishing its prognostic and diagnostic utility compared with viral HCC. This reinforces the need to investigate alternative noninvasive biomarkers and integrated models capable of more accurately reflecting disease biology in this group [

78,

79,

80].

The application of ML in this context represents an important step toward more personalized prognostication. Unlike conventional statistical approaches, ML methods do not rely on linearity assumptions or variable independence. Instead, they learn directly from the data, identifying nonlinear interactions and complex patterns among clinical, biochemical, and tumor-related variables. This results in more flexible, data-driven predictive models with enhanced discrimination and calibration capabilities [

81,

82,

83,

84]. In this study, the RF algorithm was proposed as the reference method, given its excellent performance in heterogeneous clinical datasets. By combining multiple decision trees through bagging and random predictor selection, RF reduces variance, mitigates overfitting, and is robust to noise and missing data [

85,

86]. Moreover, its ability to output variable importance measures provides transparency and interpretability, key attributes for integrating predictive models into clinical workflows.

Our results show that RF outperformed SVM, DT, GNB, and KNN by more than 10 percentage points across several performance metrics, including AUC, F1, specificity, and MCC, while maintaining nearly identical performance between training and test phases. This stability is clinically relevant: it indicates that the model is capable of maintaining its predictive accuracy when applied to new patients, which is crucial for real-world applicability. A robust, interpretable ML model focusing on hepatic functional reserve and inflammation could support clinicians in early risk stratification, guiding therapeutic prioritization and follow-up intensity. In a setting where tumor burden is often not the primary prognostic driver, this approach could help identify patients who might benefit most from early intervention or closer monitoring.

Although the AUC was highlighted due to its strong performance, we acknowledge that the interpretation of ROC-based metrics may be influenced by outcome imbalance. In our cohort, the distribution of early mortality and survival showed only a modest class imbalance, which limits this concern. Precision–recall curves, typically more informative under severe imbalance, were therefore not included. Instead, to enhance transparency and reliability, we report 95% confidence intervals for all metrics, which are now incorporated in the updated tables.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. A key limitation of this work is the relatively modest sample size, which reflects the real-world prevalence and availability of well-characterized ALD/MASLD-related HCC cases in our region. Although the cohort was multicenter, larger regional or national datasets would allow more extensive external validation and potentially improve model generalizability. The restriction to two centers within the same regional healthcare system may limit the representativeness of our cohort. Second, although we employed a rigorous internal validation strategy using 5-fold cross-validation and a 70/30 train–test split, we did not have access to an external cohort or to a sufficiently large dataset to perform a robust temporal validation (e.g., training on earlier years and testing on later years). Therefore, our findings should be considered hypothesis-generating, and the reported performance of the RF model may not directly extrapolate to other populations or healthcare settings.

Another limitation is the retrospective design of the study. Future studies using larger national or international registries, including external and temporal validation, are warranted to confirm the generalizability and clinical utility of the proposed model. It is necessary to add that our model was developed exclusively in patients with ALD- and MASLD-related HCC. Therefore, its performance in HCC secondary to viral hepatitis or other etiologies remains unknown. Comparative analyses across etiologies, ideally in independent external cohorts, are warranted to determine whether the same RF model can be generalized to non-ALD/MASLD HCC or whether etiology-specific models should be derived.

Finally, our retrospective dataset did not include standardized longitudinal follow-up, which precluded the construction of formal survival curves for albumin, CRP/albumin ratio, or other variables. Accordingly, the prognostic interpretation of these markers in our work is derived from their importance within the RF mortality-risk model at diagnosis and from previously published survival studies, rather than from time-to-event analyses performed in this cohort.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., S.G.-R., P.M.-B., A.M.T., N.M.-G., M.T. and J.M.; methodology, M.S., S.G.-R., M.T. and J.M.; software, A.M.T. and J.M.; validation, A.M.T. and J.M.; formal analysis, A.M.T. and J.M.; investigation, M.S., S.G.-R., P.M.-B., A.M.T., N.M.-G., M.T. and J.M.; resources, M.S. and J.M.; data curation, M.S., S.G.-R., P.M.-B., A.M.T., N.M.-G., M.T. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S., S.G.-R., P.M.-B., A.M.T., N.M.-G., M.T. and J.M.; visualization, M.S., S.G.-R., P.M.-B., A.M.T., N.M.-G., M.T. and J.M.; supervision, M.S. and J.M.; project administration, M.S., S.G.-R., M.T. and J.M.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital of Guadalajara, CEIm 2023.16.EO approval date 16 March 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the number of patients, study design (retrospective), absence of medical prescription, and the number of deceased patients.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Virgen de la Luz Hospital of Cuenca (Spain), Institute of Technology (University of Castilla-La Mancha), Chair of Artificial Intelligence (sponsored by Bayer), Castilla-La Mancha Institute of Health Research (IDISCAM) and University Hospital of Guadalajara (Spain).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFP | Alpha-Fetoprotein |

| ALBI | Albumin-Bilirubin score |

| ALD | Alcohol-associated Liver Disease |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| APRI | AST to Platelet Ratio Index |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BCLC | Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer |

| CRP | C Reactive Protein |

| CSPH | Clinically Significant Portal Hypertension |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| DL | Dyslipidemia |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| DYI | Youden’s Dependent Index |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| FIB-4 | Fibrosis-4 score |

| GNB | Gaussian Naïve Bayes |

| GGT | Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase |

| HBV | Hepatitis B Virus |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| MASLD | Metabolic Associated Steatotic Liver Disease |

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| MELD | Model for End-stage Liver Disease |

| MetALD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated Alcohol-related Liver Disease |

| Na | Sodium |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TNM | Tumor, Node, Metastasis staging |

References

- McGlynn, K.A.; Petrick, J.L.; El-Serag, H.B. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2021, 73, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shan, T.; Zhang, D.; Ma, F. Nowcasting and forecasting global aging and cancer burden: Analysis of data from the GLOBOCAN and Global Burden of Disease Study. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2024, 4, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Zhu, X.; Beeraka, N.M.; Zhao, R.; Li, S.; Li, F.; Mahesh, P.A.; Nikolenko, V.N.; Fan, R.; Liu, J. Projected epidemiological trends and burden of liver cancer by 2040 based on GBD, CI5plus, and WHO data. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.G.; Llovet, J.M.; Yarchoan, M.; Mehta, N.; Heimbach, J.K.; Dawson, L.A.; Jou, J.H.; Kulik, L.M.; Agopian, V.G.; Marrero, J.A. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1922–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; de Lédinghen, V.; Aubé, C.; Krag, A.; Strassburg, C.; Castéra, L.; Dumortier, J.; Friedrich-Rust, M.; Pol, S.; Grgurevic, I. Hepatocellular cancer surveillance in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. NEJM Evid. 2024, 3, EVIDoa2400062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, M.R.; Wong, E.Y.T.; Wong, S.H.; Ng, A.W.T.; Loo, L.-H.; Chow, P.K.-H.; Ngeow, J. Global epidemiology and genetics of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, 766–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, E.; de Castro, T.; Zeitlhoefler, M.; Sung, M.W.; Villanueva, A.; Mazzaferro, V.; Llovet, J.M. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, B.M.; Masarone, M.; Torre, P.; Persico, M. From non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Epidemiology, incidence, predictions, risk factors, and prevention. Cancers 2023, 15, 5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgurevic, I.; Bozin, T.; Mikus, M.; Kukla, M.; O’Beirne, J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: From epidemiology to diagnostic approach. Cancers 2021, 13, 5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Q.; Mathurin, P.; Cortez-Pinto, H.; Loomba, R. Global epidemiology of alcohol-associated cirrhosis and HCC: Trends, projections and risk factors. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Cai, J.; Yang, Z.; He, X.; Xing, Z.; Zu, J.; Xie, E.; Henry, L.; Chong, C.R.; John, E.M. Trends in hepatocellular carcinoma mortality rates in the US and projections through 2040. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2445525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G.; Kanwal, F.; Llovet, J.M. Global trends in hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology: Implications for screening, prevention and therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 864–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gellert-Kristensen, H.; Richardson, T.G.; Davey Smith, G.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Stender, S. Combined effect of PNPLA3, TM6SF2, and HSD17B13 variants on risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in the general population. Hepatology 2020, 72, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai-Kitahata, F.; Asahina, Y.; Kakinuma, S.; Inada, K.; Mochida, T.; Watakabe, K.; Nobusawa, T.; Shimizu, T.; Tsuchiya, J.; Miyoshi, M. Genetic alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma after sustained virological response in relation to the molecular characterization of metabolic diseases. Hepatol. Res. 2025, 55, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganne-Carrié, N.; Nahon, P. Differences between hepatocellular carcinoma caused by alcohol and other aetiologies. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Taherifard, E.; Saeed, A.; Saeed, A. MASLD-related HCC: A comprehensive review of the trends, pathophysiology, tumor microenvironment, surveillance, and treatment options. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 5965–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, K.; Ye, T.; Zhu, L.; Pan, C.Q. Risk-stratified hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in non-cirrhotic patients with MASLD. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2025, 13, goaf018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourou, K.; Exarchos, K.P.; Papaloukas, C.; Sakaloglou, P.; Exarchos, T.; Fotiadis, D.I. Applied machine learning in cancer research: A systematic review for patient diagnosis, classification and prognosis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 5546–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.; Matin, R.; Van der Schaar, M.; Bhayankaram, K.P.; Ranmuthu, C.; Islam, M.; Behiyat, D.; Boscott, R.; Calanzani, N.; Emery, J. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms for early detection of skin cancer in community and primary care settings: A systematic review. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e466–e476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Shi, H.; Wang, H. Machine learning and AI in cancer prognosis, prediction, and treatment selection: A critical approach. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.; Gil-Rojas, S.; Martínez-Blanco, P.; Torres, A.M.; Ramón, A.; Blasco-Segura, P.; Torralba, M.; Mateo, J. Machine learning-based assessment of survival and risk factors in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma for optimized patient management. Cancers 2024, 16, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audureau, E.; Carrat, F.; Layese, R.; Cagnot, C.; Asselah, T.; Guyader, D.; Larrey, D.; De Lédinghen, V.; Ouzan, D.; Zoulim, F. Personalized surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis–using machine learning adapted to HCV status. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.; Laguna, A.; Ikeda, I.; Maxwell, A.W.; Chapiro, J.; Nadolski, G.; Jiao, Z.; Bai, H.X. Using machine learning to predict response to image-guided therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiology 2023, 309, e222891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.-T.; Tan, E.C.-H.; Lee, P.-C.; Chu, C.-J.; Huang, Y.-H.; Huo, T.-I.; Su, Y.-H.; Hou, M.-C.; Wu, J.-C.; Su, C.-W. Conventional and machine learning-based risk scores for patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2024, 30, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigatti, S.J. Random forest. J. Insur. Med. 2017, 47, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, A.B.; Srinivasan, S. A brief survey on random forest ensembles in classification model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Computing and Communications: Proceedings of ICICC 2018, Singapore, 20 November 2018; Springer: Singapore, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Candita, G.; Rossi, S.; Cwiklinska, K.; Fanni, S.C.; Cioni, D.; Lencioni, R.; Neri, E. Imaging diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: A state-of-the-art review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.H.; Park, J.Y.; Hwang, C.; Lee, H.J.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Ryu, J.H.; Yang, K.H.; Lee, T.B.; Lee, J.H. Histological subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma: Their clinical and prognostic significance. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2023, 64, 152134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Schmieder, R.E. Diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension 2021. Kidney Int. 2022, 101, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; Aroda, V.R.; Collins, B.S.; Gabbay, R.A.; Green, J.; Maruthur, N.M.; Rosas, S.E.; Del Prato, S.; Mathieu, C.; Mingrone, G. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia 2022, 65, 1925–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, C.F.; Sikand, G.; Petersen, K.S.; Anderson, C.A.; Aspry, K.E.; Bolick, J.P.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Maki, K.C. Nutrition interventions for adults with dyslipidemia: A clinical perspective from the National Lipid Association. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2023, 17, 428–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jophlin, L.L.; Singal, A.K.; Bataller, R.; Wong, R.J.; Sauer, B.G.; Terrault, N.A.; Shah, V.H. ACG clinical guideline: Alcohol-associated liver disease. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol.|ACG 2024, 119, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevisani, F.; Vitale, A.; Kudo, M.; Kulik, L.; Park, J.-W.; Pinato, D.J.; Cillo, U. Merits and boundaries of the BCLC staging and treatment algorithm: Learning from the past to improve the future with a novel proposal. J. Hepatol. 2024, 80, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sok, M.; Zavrl, M.; Greif, B.; Srpčič, M. Objective assessment of WHO/ECOG performance status. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3793–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.R.; Mannalithara, A.; Heimbach, J.K.; Kamath, P.S.; Asrani, S.K.; Biggins, S.W.; Wood, N.L.; Gentry, S.E.; Kwong, A.J. MELD 3.0: The model for end-stage liver disease updated for the modern era. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1887–1895.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Z.J.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Ruff, S.M.; Mohseni, A.; Kamel, I.R.; Cloyd, J.M.; Pawlik, T.M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: A review. JAMA Surg. 2023, 158, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wei, Q.; He, Y.; Xie, Q.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xia, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhao, J. ALBI versus child-pugh in predicting outcome of patients with HCC: A systematic review. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 14, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ran, L.; Zhang, H.; Ren, H.; Jiang, X.; Liao, P.; Ou, M. Comparison of Child-Pugh, MELD, MELD-Na, and ALBI Scores in Predicting In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with HCC. Int. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 14, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, Y.; Yoon, J.S.; Lee, M.; Kye, S.S.; Kim, S.W.; Cho, Y. The FIB-4 index is a useful predictor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with coexisting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic hepatitis B. Cancers 2021, 13, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.; Martínez, R.; Torres, A.M.; Torres, B.; Mateo, J. A Machine Learning Method to Identify the Risk Factors for Liver Fibrosis Progression in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 3801–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Franchis, R.; Bosch, J.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Reiberger, T.; Ripoll, C.; Abraldes, J.G.; Albillos, A.; Baiges, A.; Bajaj, J.; Bañares, R. Baveno VII–renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canillas, L.; Pelegrina, A.; Álvarez, J.; Colominas-González, E.; Salar, A.; Aguilera, L.; Burdio, F.; Montes, A.; Grau, S.; Grande, L. Clinical guideline on perioperative management of patients with advanced chronic liver disease. Life 2023, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcift, A.; Gulten, A. Classifier ensemble construction with rotation forest to improve medical diagnosis performance of machine learning algorithms. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2011, 104, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuvaneswari, R.; Kalaiselvi, K. Naive Bayesian classification approach in healthcare applications. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Telecommun. 2012, 3, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Charbuty, B.; Abdulazeez, A. Classification based on decision tree algorithm for machine learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 2021, 2, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, M.; Goyal, A.; Choudhary, A. A comparative analysis of K-nearest neighbor, genetic, support vector machine, decision tree, and long short term memory algorithms in machine learning. Decis. Anal. J. 2022, 3, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Haque, I.; Lu, H.; Moni, M.A.; Gide, E. Comparative performance analysis of K-nearest neighbour (KNN) algorithm and its different variants for disease prediction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurer, M.; Hutter, F. Hyperparameter Optimization; Springer International Publishing: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Patel, H. Survey of data mining techniques used in healthcare domain. Int. J. Inf. 2016, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y. Changing etiology and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: Asia and worldwide. J. Liver Cancer 2024, 24, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Y.H.; Abdelmalek, M.; Khan, S.; Moylan, C.A.; Rodriquez, L.; Villanueva, A.; Yang, J.D. Current and emerging strategies for the prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 22, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Fujiwara, N.; Singal, A.G.; Baumert, T.F.; Chung, R.T.; Kawaguchi, T.; Hoshida, Y. Prevention of liver cancer in the era of next-generation antivirals and obesity epidemic. Hepatology. 2024. Online ahead of print.

- Polpichai, N.; Saowapa, S.; Danpanichkul, P.; Chan, S.-Y.; Sierra, L.; Blagoie, J.; Rattananukrom, C.; Sripongpun, P.; Kaewdech, A. Beyond the Liver: A Comprehensive Review of Strategies to Prevent Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Loomba, R.; Rinella, M.E. Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease: Update and impact of new nomenclature on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidance on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2024, 79, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Jung, J.; Han, S.; Kim, G.A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and MetALD increases the risk of liver cancer and gastrointestinal cancer: A nationwide cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 60, 1599–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Esteban, J.; Muñoz-Martínez, S.; Higuera, M.; Sena, E.; Bermúdez-Ramos, M.; Bañares, J.; Martínez-Gomez, M.; Cusidó, M.S.; Jiménez-Masip, A.; Francque, S.M. Phenotypes of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease–associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 1774–1789.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayares, G.; Diaz, L.A.; Idalsoaga, F.; Alkhouri, N.; Noureddin, M.; Bataller, R.; Loomba, R.; Arab, J.P.; Arrese, M. MetALD: New Perspectives on an Old Overlooked Disease. Liver Int. 2025, 45, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.K.; Arsalan, A.; Dunn, W.; Arab, J.P.; Wong, R.J.; Kuo, Y.F.; Kamath, P.S.; Shah, V.H. Alcohol-associated liver disease in the United States is associated with severe forms of disease among young, females and Hispanics. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 54, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, G.; Hookey, L.; Richardson, H.; Flemming, J.A. Alcohol-associated liver disease is now the most common indication for liver transplant waitlisting among young American adults. Transplantation 2022, 106, 2000–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, J.; Ayer, T.; Tapper, E.B.; Barbosa, C.; Dowd, W.N.; Chhatwal, J. Effect of increased alcohol consumption during COVID-19 pandemic on alcohol-associated liver disease: A modeling study. Hepatology 2022, 75, 1480–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.; Martínez-Blanco, P.; Gil-Rojas, S.; Torres, A.M.; Torralba-González, M.; Mateo, J. Assessment of Albumin-Incorporating Scores at Hepatocellular Carcinoma Diagnosis Using Machine Learning Techniques: An Evaluation of Prognostic Relevance. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Blanco, P.; Suárez, M.; Gil-Rojas, S.; Torres, A.M.; Martínez-García, N.; Blasco, P.; Torralba, M.; Mateo, J. Prognostic Factors for Mortality in Hepatocellular Carcinoma at Diagnosis: Development of a Predictive Model Using Artificial Intelligence. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bağırsakçı, E.; Şahin, E.; Atabey, N.; Erdal, E.; Guerra, V.; Carr, B.I. Role of albumin in growth inhibition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 2017, 93, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariyama, K.; Hiraoka, A.; Kumada, T.; Yasuda, S.; Toyoda, H.; Tsuji, K.; Hatanaka, T.; Kakizaki, S.; Naganuma, A.; Tada, T. Chronological change in serum albumin as a prognostic factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib: Proposal of albumin simplified grading based on the modified albumin–bilirubin score (ALBS grade). J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 57, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, K.G.; Sandow, T.; Patel, J.; Hibino, M.; Fort, D.; Cohen, A.J.; Thevenot, P. Hypoalbuminemia is a hepatocellular carcinoma independent risk factor for tumor progression in low-risk bridge to transplant candidates. Cancers 2022, 14, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Li, J.; Ke, Q.; Wang, L.; Cao, Y.; Liu, J. Clinical significance of C-reactive protein to albumin ratio in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Dis. Markers 2020, 2020, 4867974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkiz, H.; Carr, B.I.; Bag, H.G.; Karaoğullarından, Ü.; Yalçın, K.; Ekin, N.; Özakyol, A.; Altıntaş, E.; Balaban, H.Y.; Şimşek, H. Serum levels of inflammatory markers CRP, ESR and albumin in relation to survival for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e13593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, T.; Kumada, T.; Hiraoka, A.; Hirooka, M.; Kariyama, K.; Tani, J.; Atsukawa, M.; Takaguchi, K.; Itobayashi, E.; Fukunishi, S. C-reactive protein to albumin ratio predicts survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.J.; Berhane, S.; Kagebayashi, C.; Satomura, S.; Teng, M.; Reeves, H.L.; O’Beirne, J.; Fox, R.; Skowronska, A.; Palmer, D. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A new evidence-based approach—The ALBI grade. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.K.; Yim, S.Y.; Suh, S.J.; Jung, Y.K.; Kim, J.H.; Seo, Y.S.; Yim, H.J.; Yeon, J.E.; Byun, K.S.; Um, S.H. ALBI versus Child-Pugh grading systems for liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinato, D.J.; Sharma, R.; Allara, E.; Yen, C.; Arizumi, T.; Kubota, K.; Bettinger, D.; Jang, J.W.; Smirne, C.; Kim, Y.W. The ALBI grade provides objective hepatic reserve estimation across each BCLC stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carteri, R.B.; Marroni, C.A.; Ferreira, L.F.; Pinto, L.P.; Czermainski, J.; Tovo, C.V.; Fernandes, S.A. Do Child–Turcotte–Pugh and nutritional assessments predict survival in cirrhosis: A longitudinal study. World J. Hepatol. 2025, 17, 99183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yardeni, D.; Shiloh, A.; Lipnizkiy, I.; Nevo-Shor, A.; Abufreha, N.; Munteanu, D.; Novack, V.; Etzion, O. MELD-Na score may underestimate disease severity and risk of death in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.E.; Han, S.K.; Kim, T.H.; Yim, H.J.; Jung, Y.K.; Song, D.S.; Yoon, E.L.; Kim, H.Y. Validation of MELD 3.0 in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis using prospective KACLiF cohort. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 39, 1932–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.K.; Wong, R.J.; Dasarathy, S.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Limketkai, B.N.; Petrey, J.; McClain, C.J. ACG Clinical Guideline: Malnutrition and Nutritional Recommendations in Liver Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 120, 950–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Rojas, S.; Suárez, M.; Martínez-Blanco, P.; Torres, A.M.; Martínez-García, N.; Blasco, P.; Torralba, M.; Mateo, J. Application of Machine Learning Techniques to Assess Alpha-Fetoprotein at Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Masuda, A.; Nakano, D.; Amano, K.; Sano, T.; Nakano, M.; Kawaguchi, T. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD)-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cells 2025, 14, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.C.-T.; Yang, B.; Lee, H.W.; Lin, H.; Tsochatzis, E.A.; Petta, S.; Bugianesi, E.; Yoneda, M.; Zheng, M.-H.; Hagström, H. Non-invasive risk-based surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Gut 2025, 74, 2050–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, R.C. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation 2015, 132, 1920–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.H.; Milstein, A.; Bagley, S.C. Making machine learning models clinically useful. JAMA 2019, 322, 1351–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlung, L.; Cohen, Y.; Mor, U.; Elinav, E. Machine learning in clinical decision making. Med 2021, 2, 642–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M. Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of machine learning in the health sector. J. Artif. Intell. Gen. Sci. (JAIGS) 2024, 2, 36–61, ISSN: 3006-4023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Xia, J.; Jin, X.; Yan, M.; Cai, G.; Yan, J.; Ning, G. Class weights random forest algorithm for processing class imbalanced medical data. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 4641–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Rahman, M.S.; Rahman, M.S. A Random Forest based predictor for medical data classification using feature ranking. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2019, 15, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Graphical summary of the machine learning workflow used in this study. The dataset was divided into k folds for cross-validation. At each iteration, one fold (fold i) was used as the test set, while the remaining folds were used for model training. The ellipses (“…”) indicate intermediate folds omitted for graphical simplicity. Purple blocks represent data partitions (training and test folds), the green block represents the model training process, solid arrows indicate data flow during training, and dashed arrows indicate the testing phase.

Figure 2.

Flowchart summarizing the patient selection process for the study. ALD: Alcohol-associated Liver Disease. MASLD: Metabolic disfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease.

Figure 3.

Final predictive model developed, showing the variables with the greatest relative weight. MELD: Model for End-stage Liver Disease; APRI: AST to Platelet Ratio Index; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; ALBI: Albumin-bilirubin score; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group stage; CRP: C-Reactive Protein; BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage.

Figure 4.

Calibration plots of all models. The RF model shows the best calibration with the lowest Brier score (0.13), while KNN, SVM, DT, and GNB exhibit progressively poorer agreement between predicted and observed mortality risk. RF: Random Forest; KNN: K-Nearest Neighbors; SVM: Support Vector Machine; DT: Decision Tree; GNB: Gaussian Naïve Bayes.

Figure 5.

Summary of all analyzed metrics represented using a radar plot for all algorithms. The upper panel shows the training phase, while the lower panel depicts the test phase. AUC: Area Under the Curve; DYI: Youden’s Dependent Index; MCC: Matthews Correlation Coefficient; SVM: Support Vector Machine; DT: Decision Tree; GNB: Gaussian Naïve Bayes; KNN: K-Nearest Neighbors; RF: Random Forest.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with ALD- and MASLD-related HCC at diagnosis. CSPH: Clinically Significant Portal Hypertension. CRP: C-Reactive Protein.

| Characteristic | Category/Unit | n (%) or Median (IQR) |

|---|

| Age at Diagnosis | Years | 67.00 (60.00–74.00) |

| Overall Survival | Months | 14.93 (6.77–25.10) |

| Demographics and Comorbidities | | |

| Sex | Male | 143 (79.0%) |

| | Female | 38 (21.0%) |

| Alcohol Consumption | Yes | 73 (40.3%) |

| Smoking Status | Smoker | 82 (45.3%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | Yes | 72 (39.8%) |

| Obesity | Yes | 33 (18.2%) |

| Dyslipidemia | Yes | 67 (37.0%) |

| Hepatic Function and Disease Status | | |

| Cirrhosis | Yes | 155 (85.6%) |

| CSPH | Yes | 22 (12.1%) |

| Ascites | Yes | 33 (18.2%) |

| Encephalopathy | Yes | 6 (3.3%) |

| MELD Score | | 9.00 (7.00–12.00) |

| Albumin | g/dL | 3.50 (3.10–3.90) |

| INR | | 1.10 (1.00–1.20) |

| Sodium | | 137.00 (135.00–139.00) |

| Tumor Staging and Prognosis | | |

| Portal Vein Thrombosis | Yes | 57 (31.5%) |

| Metastasis | Yes | 22 (12.1%) |

| ECOG Performance Status | 0 | 121 (66.9%) |

| | 1 | 48 (26.5%) |

| | 2 | 12 (6.6%) |

| BCLC Stage | A | 78 (43.1%) |

| | B | 67 (37.0%) |

| | C | 32 (17.7%) |

| | D | 4 (2.2%) |

| Milan Criteria | Meets Criteria | 78 (43.1%) |

| Diagnosis and Surveillance | | |

| Diagnostic Method | Imaging/Clinical | 164 (90.6%) |

| | Biopsy | 17 (9.4%) |

| Surveillance/Screening | Yes | 63 (34.8%) |

| Inflammatory Parameters | | |

| CRP | mg/L | 4.80 (1.70–14.60) |

| CRP/Albumin Ratio | Ratio (quantitative) | 1.34 (0.44–4.09) |

Table 2.

Performance results of all analyzed algorithms for accuracy, recall, precision, and AUC. SVM: Support Vector Machine; DT: Decision Tree; GNB: Gaussian Naïve Bayes; KNN: K-Nearest Neighbors; RF: Random Forest; AUC: Area Under the Curve.

| Methods | Accuracy (95% CI) | Recall (95% CI) | Precision (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|

| SVM | 82.30% (80.1–84.1) | 82.40% (80.3–84.5) | 81.72% (79.5–83.1) | 0.82 (0.80–0.84) |

| DT | 80.49% (78.2–82.6) | 80.59% (78.3–82.2) | 79.92% (77.6–82.1) | 0.80 (0.78–0.82) |

| GNB | 77.15% (74.9–79.3) | 77.24% (75.0–79.4) | 76.60% (74.3–78.5) | 0.77 (0.75–0.79) |

| KNN | 87.35% (85.2–88.3) | 87.45% (85.3–88.7) | 86.73% (84.6–88.4) | 0.87 (0.85–0.89) |

| RF | 91.32% (89.3–93.3) | 91.43% (89.4–93.4) | 90.67% (88.7–92.7) | 0.91 (0.89–0.93) |

Table 3.

Summary of the different performance metrics analyzed for the algorithms employed. SVM: Support Vector Machine; DT: Decision Tree; GNB: Gaussian Naïve Bayes; KNN: K-Nearest Neighbors; RF: Random Forest; DYI: Youden’s Dependent Index; MCC: Matthews Correlation Coefficient.

| Methods | Kappa (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | F1 Score (95% CI) | DYI (95% CI) | MCC (95% CI) |

|---|

| SVM | 73.27% (71.3–75.3) | 82.21% (80.1–84.3) | 82.06% (80.0–84.1) | 82.30% (80.2–84.4) | 73.03% (71.0–75.1) |

| DT | 71.66% (69.6–73.7) | 80.40% (78.3–82.5) | 80.25% (78.1–82.4) | 80.49% (78.3–82.6) | 71.42% (69.3–73.6) |

| GNB | 68.68% (66.7–70.7) | 77.06% (74.9–79.2) | 76.92% (74.8–79.0) | 77.15% (75.0–79.4) | 68.46% (66.4–70.5) |

| KNN | 77.76% (75.7–79.8) | 87.25% (85.1–89.4) | 87.09% (84.9–89.3) | 87.35% (85.2–89.4) | 77.51% (75.4–79.6) |

| RF | 80.58% (78.5–82.7) | 91.22% (89.3–93.2) | 91.05% (89.0–93.1) | 91.32% (89.3–93.3) | 80.32% (78.3–82.4) |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |