Metabolomics Analysis Reveals the Potential Advantage of Artificial Diet-Fed Bombyx Batryticatus in Disease Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Silkworms Rearing and B. bassiana Infection

2.2. Samples Preparation and Metabolite Extraction

2.3. UPLC-MS/MS

2.4. Processing and Statistical Analysis of Metabolomics Data

2.4.1. Raw Data Processing and Quality Control

2.4.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA)

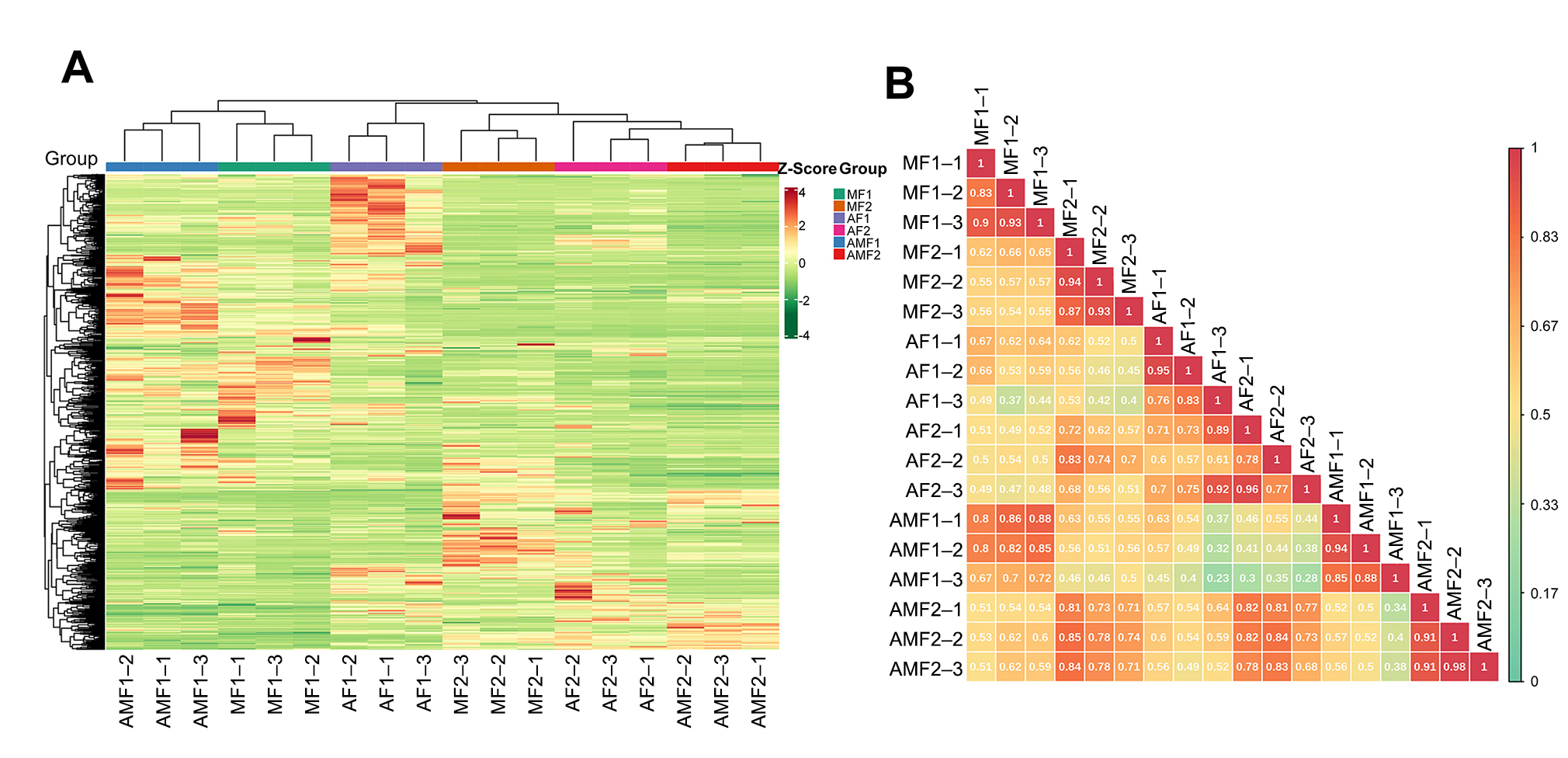

2.4.3. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis and Pearson Correlation Coefficients

2.4.4. Differential Metabolite Identification

2.4.5. KEGG Annotation and Enrichment Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quality Control and Variance Statistics

3.2. Effects of Artificial Diet Feeding on the Stiff Stage of BB

3.3. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DMs

3.4. Analysis of Metabolites Related to Artificial Diet Addition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramirez, J.L.; Gore, H.M.; Payne, A.; Pinto, S.M.; Flor-Weiler, L.B.; Fernandes, E.K.K.; Muturi, E.J. Larvicidal and immunomodulatory effects of conidia and blastospores of Beauveria bassiana and Beauveria brongniartii in Aedes aegypti. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, N.; Fernandes, É.K.K.; Dubovskiy, I.M. Multifaceted Beauveria bassiana and other insect-related fungi. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chang, M.; Feng, K.; Wang, Q.; Li, B.; Gao, W. The Therapeutic Potential of Bombyx Batryticatus for Chronic Atrophic Gastritis Precancerous Lesions via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway Based on Network Pharmacology of Blood-Entering Components. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.; Shen, G.; Li, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xia, Q. Quality Formation Mechanism of Stiff Silkworm, Bombyx batryticatus Using UPLC-Q-TOF-MS-Based Metabolomics. Molecules 2019, 24, 3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Fan, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Xiao, H.; Li, Y.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. Traditional Uses, Origins, Chemistry and Pharmacology of Bombyx batryticatus: A Review. Molecules 2017, 22, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Y. Research progress on processing historical evolution, chemical constituents, and pharmacological action of Bombyx batryticatus. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2023, 48, 3269–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, R.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, L.; Meng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Chen, B.; Wang, J. Anticonvulsant Activity of Bombyx batryticatus and Analysis of Bioactive Extracts Based on UHPLC-Q-TOF MS/MS and Molecular Networking. Molecules 2022, 27, 8315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-y.; Sheikho, A.; Ma, H.; Li, T.-c.; Zhao, Y.-q.; Zhang, Y.-l.; Wang, D. Molecular mechanisms of Bombyx batryticatus ethanol extract inducing gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells apoptosis. Cytotechnology 2017, 69, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xu, L.; Dou, Y.; Wang, J. Bombyx batryticatus Cocoonase Inhibitor Separation, Purification, and Inhibitory Effect on the Proliferation of SMCC-7721 HeLa-Derived Cells. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 4064829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, B.S.; An, H.-G.; Moon, S.-K.; Lee, Y.-C.; Kim, H.-M.; Ko, J.-H.; Kim, C.-H. Bombycis corpus extract (BCE) protects hippocampal neurons against excitatory amino acid-induced neurotoxicity. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2003, 25, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.N.; Jang, J.-P.; Shin, H.J.; Jang, J.-H.; Ahn, J.S.; Jung, H.J. Cytotoxic Activities and Molecular Mechanisms of the Beauvericin and Beauvericin G1 Microbial Products against Melanoma Cells. Molecules 2020, 25, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Z.; Shi, L. Structural elucidation and in vitro antitumor activity of a novel oligosaccharide from Bombyx batryticatus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 103, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Sun, Y.; Chang, W.; Zhang, J.; Sang, J.; Zhao, J.; Song, M.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, M.; et al. The silkworm (Bombyx mori) gut microbiota is involved in metabolic detoxification by glucosylation of plant toxins. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Deng, J.; Deng, X.; Liu, L.; Zha, X. Metabonomic Analysis of Silkworm Midgut Reveals Differences between the Physiological Effects of an Artificial and Mulberry Leaf Diet. Insects 2023, 14, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Wang, G.; Dong, Z.; Xia, Q.; Zhao, P. Comparative Fecal Metabolomes of Silkworms Being Fed Mulberry Leaf and Artificial Diet. Insects 2020, 11, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W.; Lan, B.; Tang, Q.; Dong, G.; Li, A.; Jia, X.; Bin, R.; Zhang, G. The Research Advancement of Artificial Diet Rearing for Larvae of Silkworms in China. Guangxi Seric. 2020, 57, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Sun, F.; Li, B.; Ye, C. Haemolymph metabolomic differences in silkworms (Bombyx mori) under mulberry leaf and two artificial diet rearing methods. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 109, e21851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.-L.; Zhang, S.-X.; Tao, H.; Chen, Z.-H.; Li, X.; Qiu, J.-F.; Cui, W.-Z.; Sima, Y.-H.; Cui, W.-Z.; Xu, S.-Q. Metabolomics differences between silkworms (Bombyx mori) reared on fresh mulberry (Morus) leaves or artificial diets. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Qi, J.; Shen, G.; Qin, D.; Wu, J.; Song, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, P.; Xia, Q. Effects of Microbial Transfer during Food-Gut-Feces Circulation on the Health of Bombyx mori. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02357-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, J.; Parween, G.; Khator, R.; Monga, V. A comprehensive review of apigenin a dietary flavonoid: Biological sources, nutraceutical prospects, chemistry and pharmacological insights and health benefits. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 4529–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruganathan, N.; Dhanapal, A.R.; Baskar, V.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Selvaraj, D.; Aara, H.; Shiek Abdullah, M.Z.; Sivanesan, I. Recent Updates on Source, Biosynthesis, and Therapeutic Potential of Natural Flavonoid Luteolin: A Review. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Venditti, A.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kręgiel, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Santini, A.; Souto, E.B.; Novellino, E.; et al. The Therapeutic Potential of Apigenin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.F.; Braidy, N.; Gortzi, O.; Sobarzo-Sanchez, E.; Daglia, M.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Nabavi, S.M. Luteolin as an anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective agent: A brief review. Brain Res. Bull. 2015, 119, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franza, L.; Carusi, V.; Nucera, E.; Pandolfi, F. Luteolin, inflammation and cancer: Special emphasis on gut microbiota. BioFactors 2021, 47, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradi, E.; Schmidt, N.; Räber, N.; De Mieri, M.; Hamburger, M.; Butterweck, V.; Potterat, O. Metabolite Profile and Antiproliferative Effects in HaCaT Cells of a Salix reticulata Extract. Planta Med. 2017, 83, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdowska, I.; Zieliński, B.; Matusiewicz, M.; Fecka, I. Modulatory Impact of Lamiaceae Metabolites on Apoptosis of Human Leukemia Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 867709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-O.; Kwon, T.-K.; Choi, S.-W. Diferuloylputrescine, a Predominant Phenolic Amide in Corn Bran, Potently Induces Apoptosis in Human Leukemia U937 Cells. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Song, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Fan, L. Widely target metabolomics analysis of the differences in metabolites of licorice under drought stress. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 202, 117071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Pang, D.; Chen, L.; Bian, Y.; Wan, H.; He, W.; Cao, M. Response of growth and metabolism of Artemisia scoparia toprecipitation change in desert steppe. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2022, 44, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, T.; Doi, U.; Osawa, T. Inhibitory Activity of Corn-Derived Bisamide Compounds against α-Glucosidase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Jia, T.Z.; Cao, Q.C.; Tian, F.; Ying, W.T. A Crude 1-DNJ Extract from Home Made Bombyx batryticatus Inhibits Diabetic Cardiomyopathy-Associated Fibrosis in db/db Mice and Reduces Protein N-Glycosylation Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, L.; An, X.; Li, J.; Niu, C.; Zhang, J.; Geng, Z.; Xu, T.; Yang, B.; Xu, Z.; et al. Hybridization promotes growth performance by altering rumen microbiota and metabolites in sheep. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1455029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.M.; Higashiguchi, S.; Horie, K.; Kim, M.; Hatta, H.; Yokogoshi, H. Relaxation and immunity enhancement effects of γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) administration in humans. BioFactors 2006, 26, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.-r.; Lu, H.-t.; Wang, Y.-z.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.-m. Highly Efficient Formal Synthesis of Cephalotaxine, Using the Stevens Rearrangement−Acid Lactonization Sequence as A Key Transformation. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2213–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Formula | Compounds | Class I | Log2FC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF2 vs. MF1 | AMF2 vs. AMF1 | |||

| C8H8O5 | 3-O-Methylgallic acid | Phenolic acids | 4.99 | 7.77 |

| C14H20O8 | 5-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-2-O-glucosylphenol | Phenolic acids | −17.82 | −7.01 |

| C17H22O10 | 4-O-Glucosyl-sinapate | Phenolic acids | −1.56 | −5.36 |

| C21H20O11 | Kaempferol-3-O-galactoside (Trifolin) | Flavonoids | −21.18 | −22.02 |

| C14H17N5O8 | Succinyladenosine | Nucleotides and derivatives | −2.92 | −2.39 |

| C23H48NO7P | LysoPC 15:0 (2n isomer) | Lipids | −3.56 | −5.17 |

| C24H48NO7P | LysoPC 16:1 | Lipids | −2.89 | −4.75 |

| C26H46NO7P | LysoPC 18:4 | Lipids | −1.69 | −3.19 |

| C27H50NO7P | LysoPC 19:3 | Lipids | −2.76 | −2.56 |

| C28H48NO7P | LysoPC 20:5 | Lipids | −3.30 | −3.95 |

| C28H36O13 | Syringaresinol-4′-O-g−lucoside | Lignans and Coumarins | −2.66 | −3.82 |

| C4H6O4 | Methylmalonic acid | Organic acids | −2.16 | −2.43 |

| C4H6O4 | Succinic acid | Organic acids | −2.16 | −2.43 |

| C5H10O6 | D-Xylonic acid | Others | −1.06 | −2.04 |

| C6H15O9P | Sorbitol-6-phosphate | Others | −4.99 | −6.93 |

| Formula | Compounds | Class I | Log2FC (AF2 vs. AF1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C14H20N6O5S | S-(5′-Adenosy)-L-homocysteine | Amino acids and derivatives | 1.57 |

| C10H13N5O3 | 5′-Deoxyadenosine | Nucleotides and derivatives | 15.76 |

| C6H5N5O2 | Isoxanthopterin | Nucleotides and derivatives | 2.47 |

| C7H6O2 | 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | Phenolic acids | −1.64 |

| C21H20O10 | Galangin-7-O-glucoside | Flavonoids | −3.72 |

| C15H10O6 | Kaempferol (3,5,7,4′-Tetrahydroxyflavone) | Flavonoids | −2.76 |

| C15H10O7 | Quercetin | Flavonoids | −2.61 |

| C15H10O7 | Morin | Flavonoids | −1.95 |

| C13H10N2O | 1-Acetyl-β-carboline | Alkaloids | −1.87 |

| C11H20O4 | Undecanedioic acid | Lipids | −1.74 |

| C18H30O4 | 13(s)-hydroperoxy-(9z,11e,15z)-octadecatrienoic acid | Lipids | −1.23 |

| C8H16NO9P | N-Acetyl-D-glucosamine-1-phosphate | Others | −2.03 |

| Comparison | All Significant Difference | Relative Down | Relative Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMF1_vs_AF1 | 366 | 171 | 195 |

| MF1_vs_AF1 | 337 | 191 | 146 |

| MF1_vs_AMF1 | 264 | 185 | 79 |

| AMF2_vs_AF2 | 301 | 209 | 92 |

| MF2_vs_AF2 | 309 | 134 | 175 |

| MF2_vs_AMF2 | 326 | 72 | 254 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Feng, Y.; Pang, D.; Yang, Q.; Zou, Y.; Lin, P.; Shen, G.; Xing, D. Metabolomics Analysis Reveals the Potential Advantage of Artificial Diet-Fed Bombyx Batryticatus in Disease Treatment. Metabolites 2026, 16, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010051

Chen H, Feng Y, Pang D, Yang Q, Zou Y, Lin P, Shen G, Xing D. Metabolomics Analysis Reveals the Potential Advantage of Artificial Diet-Fed Bombyx Batryticatus in Disease Treatment. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Han, Yuting Feng, Daorui Pang, Qiong Yang, Yuxiao Zou, Ping Lin, Guanwang Shen, and Dongxu Xing. 2026. "Metabolomics Analysis Reveals the Potential Advantage of Artificial Diet-Fed Bombyx Batryticatus in Disease Treatment" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010051

APA StyleChen, H., Feng, Y., Pang, D., Yang, Q., Zou, Y., Lin, P., Shen, G., & Xing, D. (2026). Metabolomics Analysis Reveals the Potential Advantage of Artificial Diet-Fed Bombyx Batryticatus in Disease Treatment. Metabolites, 16(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010051