Extracellular Water and Phase Angle, Markers of Heightened Inflammatory State, and Their Extrapolative Potential for Body Composition Outcomes in Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Bioimpedance Measurements

2.3. Diagnostic Criteria

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Alternating Current Conductivity |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BIA | Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis |

| BIA-ACC | Bioelectric Impedance Analyzer-Alternating Current Conductivity |

| BMD | Bone Mineral Density |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CRP | C-reactive Protein |

| ECW | Extracellular Water |

| ECW/TBW | Extracellular Water-to-Total Body Water Ratio |

| FM | Fat Mass |

| FM% | Fat Mass Percentage |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IMAT | Intramuscular Adipose Tissue |

| IMAT% | Intramuscular Adipose Tissue Percentage |

| PhA or PA | Phase Angle |

| ROC | Receiver Operator Characteristic |

| S-Score | Skeletal Muscle Score |

| TBW | Total Body Water |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| T-Score | Bone Density Score |

References

- Ahmed, B.; Shaw, S.; Pratt, O.; Forde, C.; Lal, S.; Cbe, G.C. Oxygen utilisation in patients on prolonged parenteral nutrition; a case-controlled study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 56, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, C.J.; Racette, S.B. The Utility of Body Composition Assessment in Nutrition and Clinical Practice: An Overview of Current Methodology. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilich, J.Z.; Pokimica, B.; Ristić-Medić, D.; Petrović, S.; Arsić, A.; Vasiljević, N.; Vučić, V.; Kelly, O.J. Osteosarcopenic adiposity and its relation to cancer and chronic diseases: Implications for research to delineate mechanisms and improve clinical outcomes. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 103, 102601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilich, J.Z.; Pokimica, B.; Ristić-Medić, D.; Petrović, S.; Arsić, A.; Vasiljević, N.; Vučić, V.; Kelly, O.J. Osteosarcopenic adi-posity (OSA) phenotype and its connection with cardiometabolic disorders: Is there a cause-and-effect? Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 98, 102326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chung, H.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, M.K.; Roh, Y.K.; Yu, J.M.; Oh, C.-M.; Kim, J.; Moon, S. Association between body composition and the risk of mortality in the obese population in the United States. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1257902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C.K.; Cole, T.J. Disentangling the size and adiposity components of obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 548–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-Y.; Ilich, J.Z.; Brummel-Smith, K.; Ghosh, S. New insight into fat, muscle and bone relationship in women: Determining the threshold at which body fat assumes negative relationship with bone mineral density. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, 1452–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Ilich, J.Z. Nutritional and Behavioral Approaches to Body Composition and Low-Grade Chronic Inflammation Management for Older Adults in the Ordinary and COVID-19 Times. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilich, J.Z.; Gilman, J.C.; Cvijetic, S.; Boschiero, D. Chronic Stress Contributes to Osteosarcopenic Adiposity via Inflammation and Immune Modulation: The Case for More Precise Nutritional Investigation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Levy, B.D. Resolvins in inflammation: Emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2657–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granger, D.N.; Senchenkova, E. Inflammation and the Microcirculation; Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences: San Rafael, CA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, T.; Gilroy, D.W. Chronic inflammation: A failure of resolution? Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2006, 88, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, H.; Swartz, M.A. Interstitial Fluid and Lymph Formation and Transport: Physiological Regulation and Roles in Inflammation and Cancer. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1005–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-X.; Tang, Y.-H.; Zhou, W.-X.; Desiderio, J.; Parisi, A.; Xie, J.-W.; Wang, J.-B.; Cianchi, F.; Antonuzzo, L.; Borghi, F.; et al. Body composition parameters predict pathological response and outcomes in locally advanced gastric cancer after neoadjuvant treatment: A multicenter, international study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4980–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A. Chronic inflammation: The enemy within. J. Med. Allied Sci. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaski, H.C.; Diaz, N.V.; Talluri, A.; Nescolarde, L. Classification of Hydration in Clinical Conditions: Indirect and Direct Approaches Using Bioimpedance. Nutrients 2019, 11, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczyk, E.; Dzięgielewska-Gęsiak, S.; Fatyga, E.; Ziółko, E.; Kokot, T.; Muc-Wierzgon, M. Body composition in healthy older persons: Role of the ratio of extracellular/total body water. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost Agents 2016, 30, 767–772. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa-Silva, M.C.G.; Barros, A.J.; Wang, J.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Pierson, R.N. Bioelectrical impedance analysis: Population reference values for phase angle by age and sex. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Morales, R.; Donate-Correa, J.; Martín-Núñez, E.; Pérez-Delgado, N.; Ferri, C.; López-Montes, A.; Jiménez-Sosa, A.; Navarro-González, J.F. Extracellular water/total body water ratio as predictor of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Ren. Fail. 2021, 43, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson-Newberry, S.J.; Costello, R.B. Bioelectrical Impedance: A History, Research Issues, and Recent Consensus. In Emerging Technologies for Nutrition Research: Potential for Assessing Military Performance Capability; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- D’aDamo, C.R.; Miller, R.R.; Shardell, M.D.; Orwig, D.L.; Hochberg, M.C.; Ferrucci, L.; Semba, R.D.; Yu-Yahiro, J.A.; Magaziner, J.; Hicks, G.E. Higher serum concentrations of dietary antioxidants are associated with lower levels of inflammatory biomarkers during the year after hip fracture. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Tetsunaga, T.; Misawa, H.; Nishida, K.; Ozaki, T. Association of phase angle with sarcopenia in chronic musculoskeletal pain patients: A retrospective study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vona, R.; Pallotta, L.; Cappelletti, M.; Severi, C.; Matarrese, P. The Impact of Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology: Focus on Gastrointestinal Disorders. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, B.R.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Cereda, E.; Prado, C.M. Exploring the potential role of phase angle as a marker of oxidative stress: A narrative review. Nutrition 2022, 93, 111493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.C.; Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Bielemann, R.M.; Gallagher, D.; Heymsfield, S.B. Phase angle and its determinants in healthy subjects: Influence of body composition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvino, V.O.; Barros, K.R.B.; Brito, F.M.; Magalhães, F.M.D.; Carioca, A.A.F.; Loureiro, A.C.C.; Veras-Silva, A.S.; Drummond, M.D.M.; dos Santos, M.A.P. Phase angle as an indicator of body composition and physical performance in handball players. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.D.; Brito, J.P.; Batalha, N.; Oliveira, R.; Parraca, J.A.; Fernandes, O. Phase angle as a key marker of muscular and bone quality in community-dwelling independent older adults: A cross-sectional exploratory pilot study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancello, R.; Brunani, A.; Brenna, E.; Soranna, D.; Bertoli, S.; Zambon, A.; Lukaski, H.C.; Capodaglio, P. Phase angle (PhA) in overweight and obesity: Evidence of applicability from diagnosis to weight changes in obesity treatment. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 24, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.; Cyrino, E.S.; Silva, D.R.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Nabuco, H.C.; Cavalcante, E.F.; Cunha, P.M.; Cyrino, L.T.; dos Santos, L.; Silva, A.M.; et al. Total and regional bone mineral density are associated with cellular health in older men and women. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 90, 104156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Ando, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Hida, T.; Ito, K.; Tsushima, M.; Morozumi, M.; Machino, M.; Ota, K.; Seki, T.; et al. A low phase angle measured with bioelectrical impedance analysis is associated with osteoporosis and is a risk factor for osteoporosis in community-dwelling people: The Yakumo study. Arch. Osteoporos. 2018, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.C.; Gónzalez, P.G.; Fernández, T.F.G.; Bueno, S.C.; Calvo, N.B.; Cardoso, B.S.; Lorido, J.C.A. Bioelectrical impedance-derived phase angle (PhA) in people living with obesity: Role in sarcopenia and comorbidities. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 2511–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savulescu-Fiedler, I.; Mihalcea, R.; Dragosloveanu, S.; Scheau, C.; Baz, R.O.; Caruntu, A.; Scheau, A.-E.; Caruntu, C.; Benea, S.N. The Interplay between Obesity and Inflammation. Life 2024, 14, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Player, E.; Morris, P.; Thomas, T.; Chan, W.; Vyas, R.; Dutton, J.; Tang, J.; Alexandre, L.; Forbes, A. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA)-derived phase angle (PA) is a practical aid to nutritional assessment in hospital in-patients. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1700–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Margáin, A.; Xie, J.J.; Román-Calleja, B.M.; Pauly, M.; White, M.G.; Chapa-Ibargüengoitia, M.; Campos-Murguía, A.; González-Regueiro, J.A.; Macias-Rodríguez, R.U.; Duarte-Rojo, A. Phase Angle from Bioelectrical Impedance for the Assessment of Sarcopenia in Cirrhosis With or Without Ascites. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1941–1949.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, A.E.S.; Ramos-Vázquez, A.G.; Reyes-Torres, C.A.; Castillo-Martínez, L. Body composition by bioelectrical impedance, muscle strength, and nutritional risk in oropharyngeal dysphagia patients. Nutr. Hosp. 2021, 38, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Aprano, S.; Vetrani, C.; de Alteriis, G.; Varcamonti, L.; Verde, L.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S. Phase angle as an easy diagnostic tool for the nutritionist in the evaluation of inflammatory changes during the active stage of a very low-calorie ketogenic diet. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 46, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvijetić, S.; Keser, I.; Boschiero, D.; Ilich, J.Z. Prevalence of Osteosarcopenic Adiposity in Apparently Healthy Adults and Appraisal of Age, Sex, and Ethnic Differences. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, R.H.; Ehrenstein, B.; Günther, F.; Rauch, L.; Trendafilova, N.; Boschiero, D.; Grifka, J.; Fleck, M. Increased extracellular water measured by bioimpedance and by increased serum levels of atrial natriuretic peptide in RA patients—signs of volume overload. Clin. Rheumatol. 2016, 36, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsigos, C.; Stefanaki, C.; Lambrou, G.I.; Boschiero, D.; Chrousos, G.P. Stress and inflammatory biomarkers and symptoms are associated with bioimpedance measures. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 45, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrousos, G.P.; Papadopoulou-Marketou, N.; Bacopoulou, F.; Lucafò, M.; Gallotta, A.; Boschiero, D. Photoplethysmography (PPG)-determined heart rate variability (HRV) and extracellular water (ECW) in the evaluation of chronic stress and inflammation. Hormones 2022, 21, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, A.W.; Chin, G.C.; Looney, D.P.; E Friedl, K. Defining Overweight and Obesity by Percent Body Fat Instead of Body Mass Index. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 110, e1103–e1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, O.J.; Gilman, J.C.; Boschiero, D.; Ilich, J.Z. Osteosarcopenic Obesity: Current Knowledge, Revised Identification Criteria and Treatment Principles. Nutrients 2019, 11, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, J.A.; McNeil, B.J. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 1983, 148, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, U.G.; Schutz, Y.; Dupertuis, Y.M.; Pichard, C. Body composition interpretation: Contributions of the fat-free mass index and the body fat mass index. Nutrition 2003, 19, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schorr, M.; Dichtel, L.E.; Gerweck, A.V.; Valera, R.D.; Torriani, M.; Miller, K.K.; Bredella, M.A. Sex differences in body composition and association with cardiometabolic risk. Biol. Sex Differ. 2018, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Miao, J.; Zhao, T.; Cai, J.; Liu, M.; Cao, J.; Xu, H.; Wei, L.; et al. Sex- and Age-Specific Prevalence of Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: Sampling Survey. JMIR Public Heal. Surveill. 2024, 10, e48947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafrazi, N.; Wambogo, E.A.; Shepherd, J.A. Osteoporosis or Low Bone Mass in Older Adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief 2021, 405, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sulis, S.; Falbová, D.; Beňuš, R.; Švábová, P.; Hozáková, A.; Vorobeľová, L. Sex and Obesity-Specific Associations of Ultrasound-Assessed Radial Velocity of Sound with Body Composition. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, Y.; Tsunoda, K.; Nagata, K.; Lim, N.; Tsuji, T.; Shibuya, K.; Okura, T. Segmental phase angle and the extracellular to intracellular water ratio are associated with functional disability in community-dwelling older adults: A follow-up study of up to 12 years. Nutrition 2025, 133, 112709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Gao, N.; Song, J.; Jia, J.; Dong, A.; Xia, W. The association between tea consumption and non-malignant digestive system diseases: A Mendelian randomized study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 60, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harimawan, A.I.W.; Prabandari, A.A.S.M.; Wihandani, D.M.; Jawi, I.M.; Weta, I.W.; Senapathi, T.G.A.; Dewi, N.N.A.; Sundari, L.P.R.; Ryalino, C. Association between phase angle and ECW/TBW ratio with body composition in individuals with central obesity: A cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1638075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubart, E.; Segal, R.; Wainstein, J.; Marinov, G.; Yarovoy, A.; Leibovitz, A. Evaluation of an intra-institutional diabetes disease management program for the glycemic control of elderly long-term care diabetic patients. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2013, 14, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, L.; Shi, W.; Xu, K.; Shen, Y.; Dai, B. Oxidative stress and inflammation: Roles in osteoporosis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1611932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopiczko, A.; Adamczyk, J.G.; Gryko, K.; Popowczak, M. Bone mineral density in elite master’s athletes: The effect of body composition and long-term exercise. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2020, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fell, C.W.; Nagy, V. Cellular Models and High-Throughput Screening for Genetic Causality of Intellectual Disability. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsura, N.; Yamashita, M.; Ishihara, T. Extracellular water to total body water ratio may mediate the association between phase angle and mortality in patients with cancer cachexia: A single-center, retrospective study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 46, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.-S.; Lee, G.-Y.; Seo, Y.-M.; Seo, S.-H.; Yoo, J.-I. The relationship between extracellular water-to-body water ratio and sarcopenia according to the newly revised Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 2471–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean ± SD | p * | Range | Percentile 25–75% | Reference Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (6412) | Men (3305) | |||||

| Age (yrs) | 47.6 ± 13.5 | 47.8 ± 14.1 | 0.430 | 20.0–90.0 | 38.0–57.0 | / |

| Weight (kg) | 66.7 ± 14.4 | 82.9 ± 15.1 | <0.001 | 40.0–149.0 | 60.0–82.0 | / |

| Height (cm) | 163.1 + 7.0 | 176.4 ± 7.0 | <0.001 | 141.0–199.0 | 160.0–174.0 | / |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.1 ± 5.4 | 26.6 ± 4.6 | <0.001 | 14.5–57.2 | 21.9–28.3 | 18.5–29.9 |

| T-score | −1.1 ± 0.8 | −0.3 ± 0.7 | <0.001 | −3.3–5.2 | −1.5-(−0.3) | >−1 |

| S-score | −0.9 ± 1.4 | −0.1 ± 1.2 | <0.001 | −4.5–9.0 | −1.6–0.1 | >−1 |

| FM (%) | 33.2 ± 8.6 | 32.5 ± 7.3 | <0.001 | 5.0–57.0 | 27.0–39.0 | <30.0 (F) <25.0 (M) |

| IMAT (%) | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | <0.001 | 0–3.5 | 1.7–2.5 | <2% |

| ECW/TBW (%) | 50.0 ± 4.3 | 42.7 ± 2.7 | <0.001 | 36.0–71.0 | 43.0–51.0 | 40% |

| PhA (0) | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 1.3 | <0.001 | −2.1–22.7 | 1.8–3.4 | >3.5 |

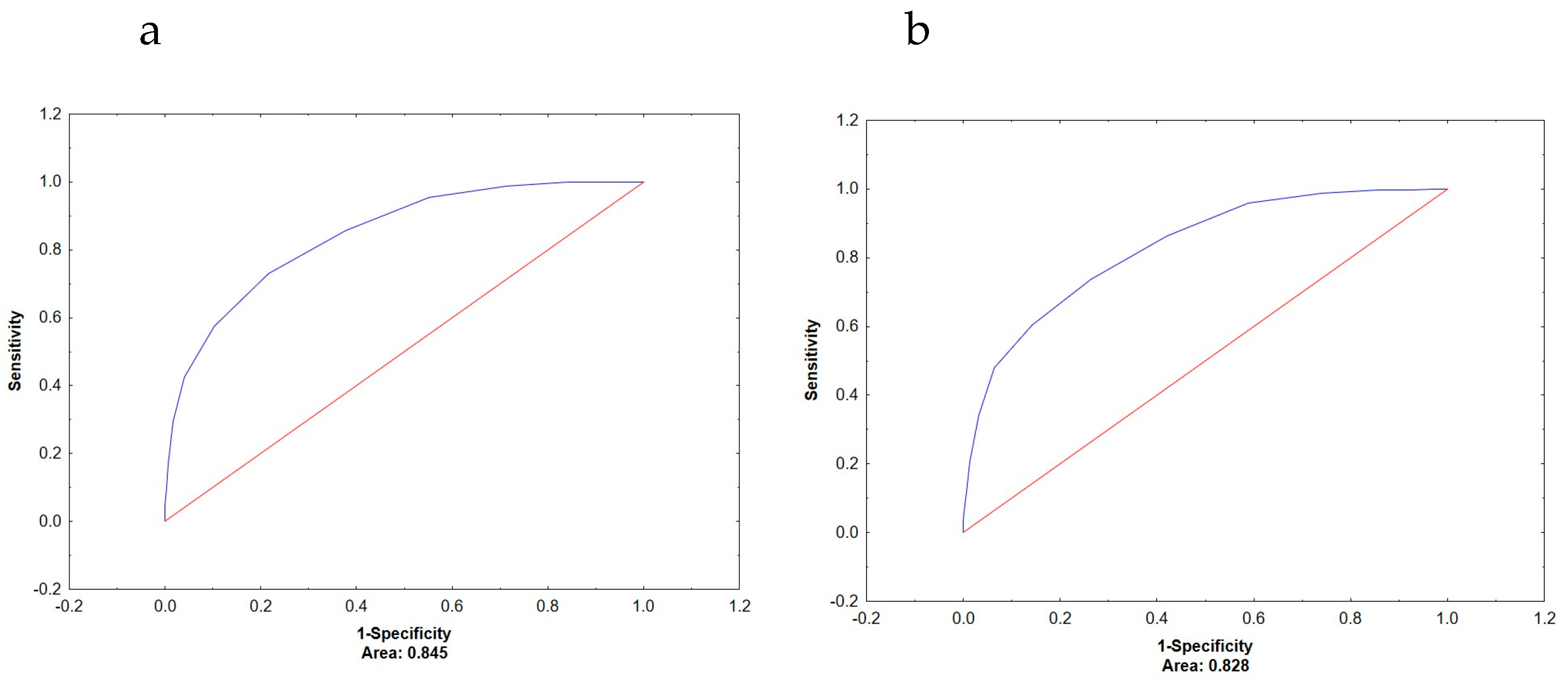

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECW/TBW | PhA | p * | ||

| Women | Low/normal muscle mass | 0.922 | 0.608 | <0.001 |

| Low/normal bone mass | 0.885 | 0.577 | <0.001 | |

| Increased/normal fat mass | 0.713 | 0.574 | <0.001 | |

| Men | Low/normal muscle mass | 0.845 | 0.719 | <0.001 |

| Low/normal bone mass | 0.828 | 0.696 | <0.001 | |

| Increased/normal fat mass | 0.647 | 0.650 | 0.920 | |

| Dependent variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECW/TBW | PhA | |||

| b | p * | b | p * | |

| Intercept | 47.8 | <0.001 | 10.1 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Sex | −6.18 | <0.001 | 0.82 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 0.46 | <0.001 | −0.45 | <0.001 |

| T-score | −1.14 | <0.001 | 1.22 | <0.001 |

| S-score | −1.58 | <0.001 | 2.13 | <0.001 |

| FM% | 0.38 | <0.001 | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| R2 | 0.943 | 0.368 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cvijetić, S.; Boschiero, D.; Shin, H.; Reilly, A.S.; Noorani, S.T.; Vasiljevic, N.; Ilich, J.Z. Extracellular Water and Phase Angle, Markers of Heightened Inflammatory State, and Their Extrapolative Potential for Body Composition Outcomes in Adults. Metabolites 2026, 16, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010040

Cvijetić S, Boschiero D, Shin H, Reilly AS, Noorani ST, Vasiljevic N, Ilich JZ. Extracellular Water and Phase Angle, Markers of Heightened Inflammatory State, and Their Extrapolative Potential for Body Composition Outcomes in Adults. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleCvijetić, Selma, Dario Boschiero, Hyehyung Shin, Andrew S. Reilly, Sarah T. Noorani, Nadja Vasiljevic, and Jasminka Z. Ilich. 2026. "Extracellular Water and Phase Angle, Markers of Heightened Inflammatory State, and Their Extrapolative Potential for Body Composition Outcomes in Adults" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010040

APA StyleCvijetić, S., Boschiero, D., Shin, H., Reilly, A. S., Noorani, S. T., Vasiljevic, N., & Ilich, J. Z. (2026). Extracellular Water and Phase Angle, Markers of Heightened Inflammatory State, and Their Extrapolative Potential for Body Composition Outcomes in Adults. Metabolites, 16(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010040