Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal the Molecular Mechanism of Flower Color Variations in Rosa chinensis Cultivar ‘Rainbow’s End’

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

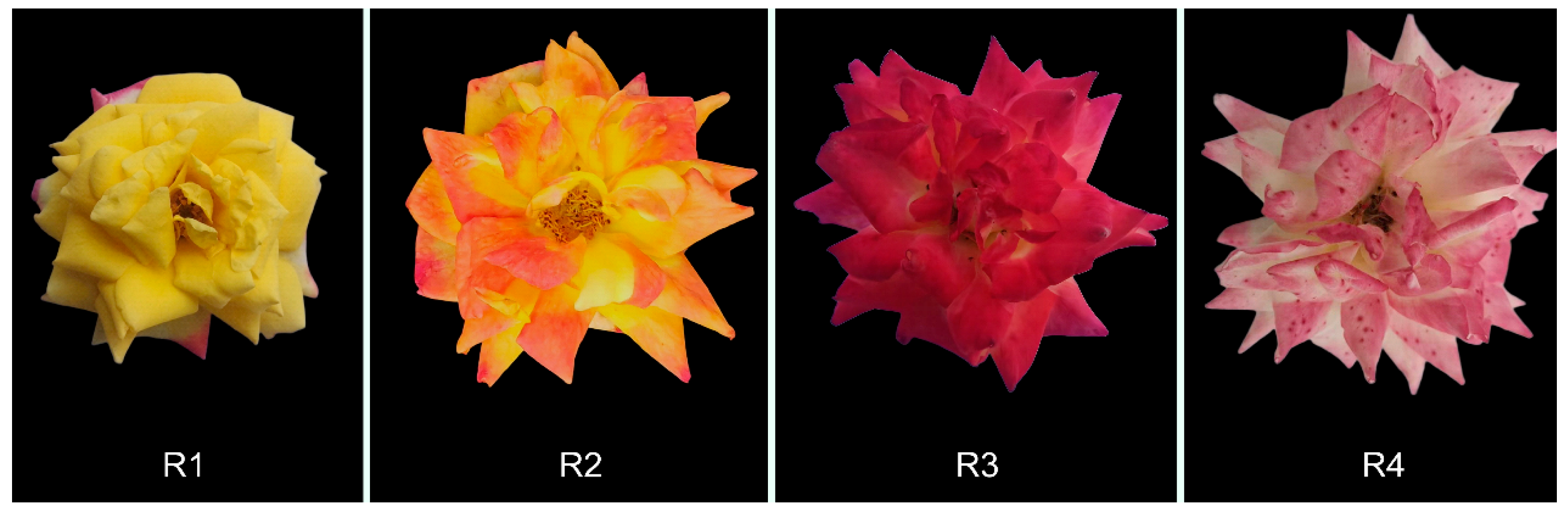

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Pigment Separation

2.3. Targeted Metabolome Profiling and Analysis

2.4. RNA-Seq

2.5. qRT-PCR

3. Result

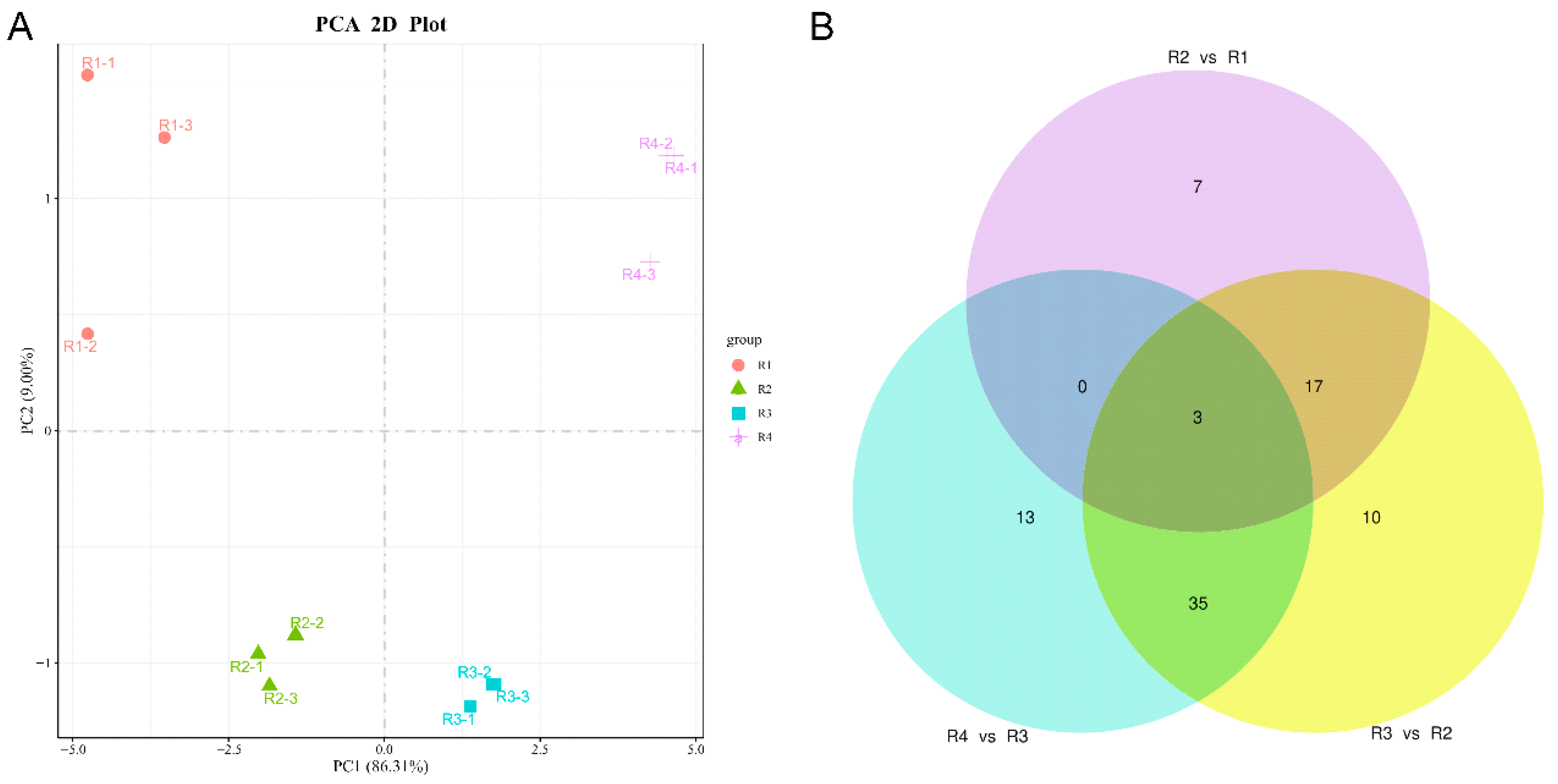

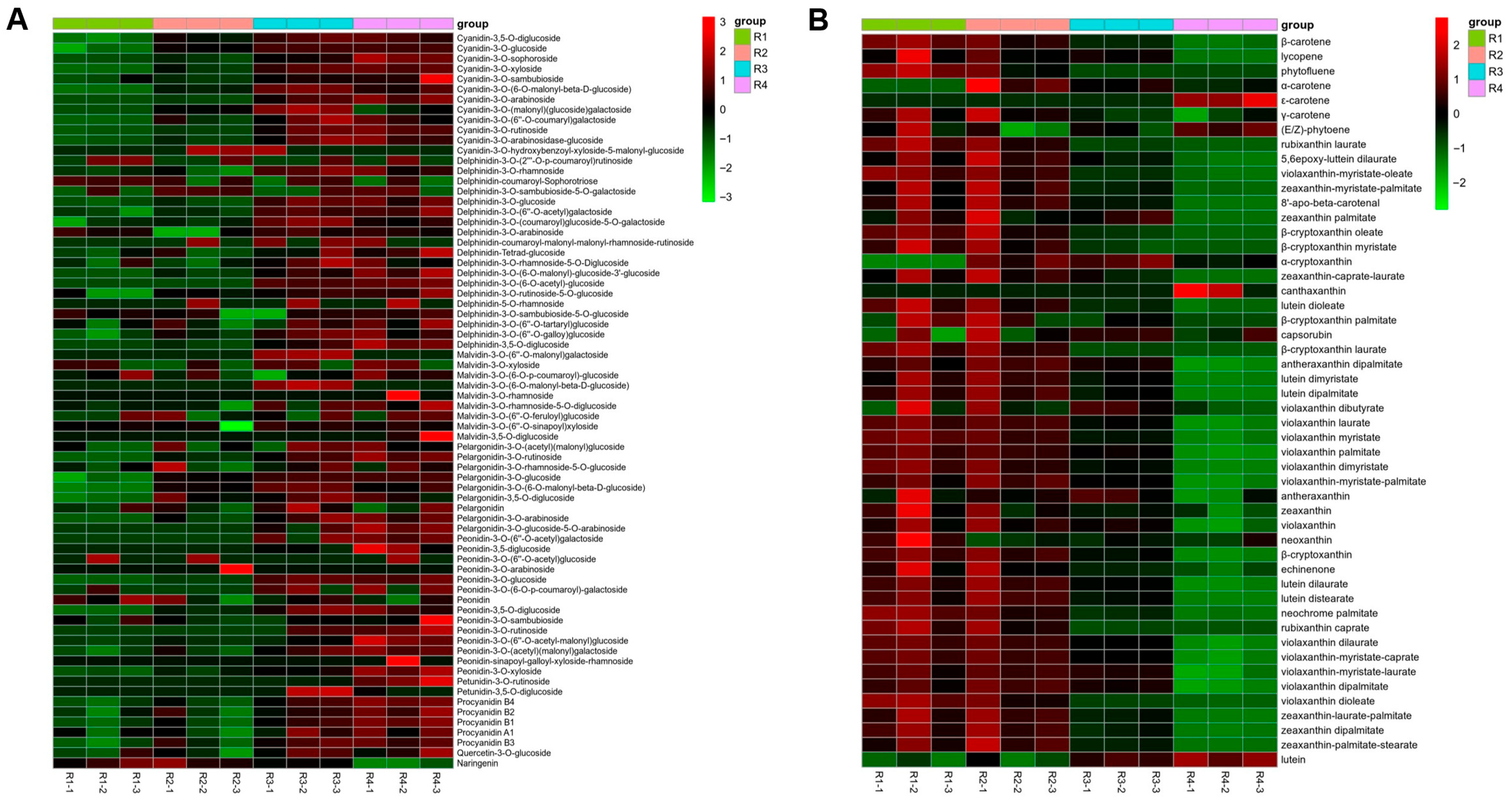

3.1. Analysis of Targeted Anthocyanin and Carotenoid Metabolites in Flowers of Various Colors

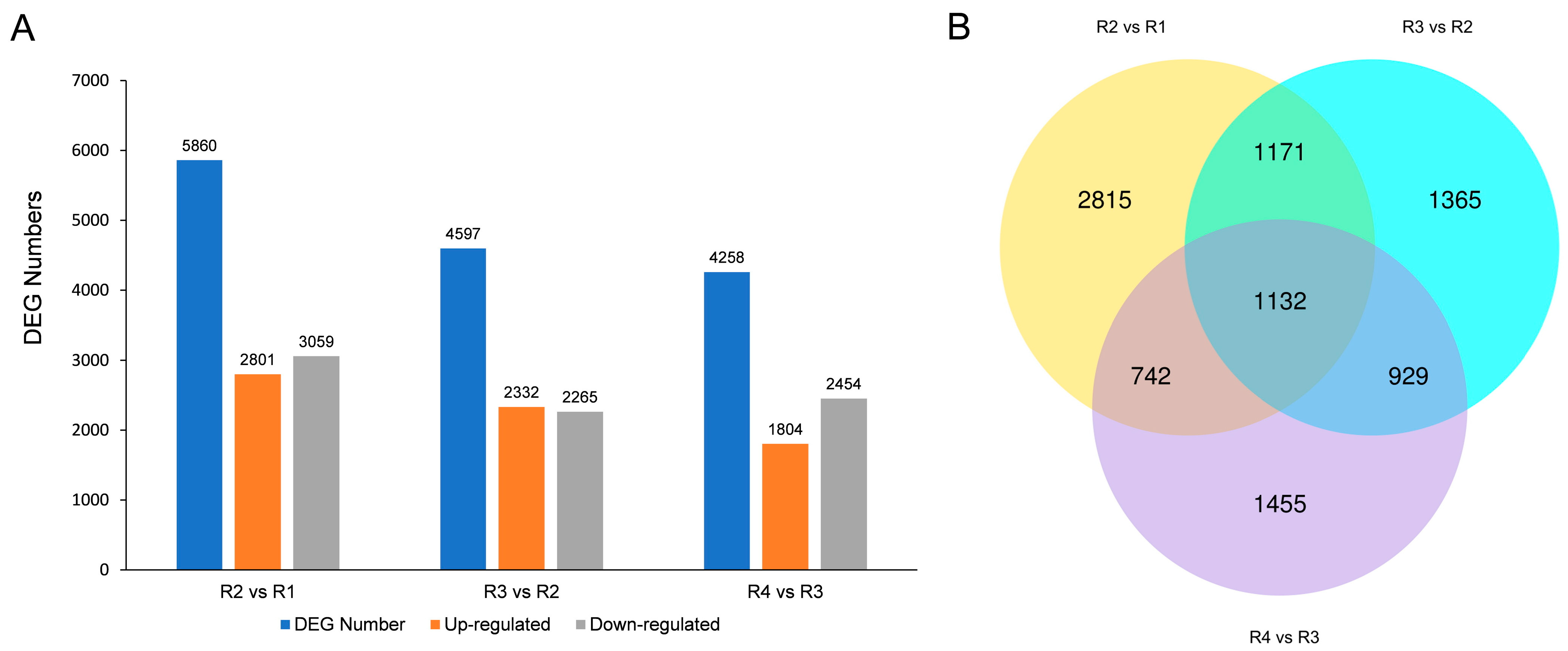

3.2. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Analysis

3.3. Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis of DEGs

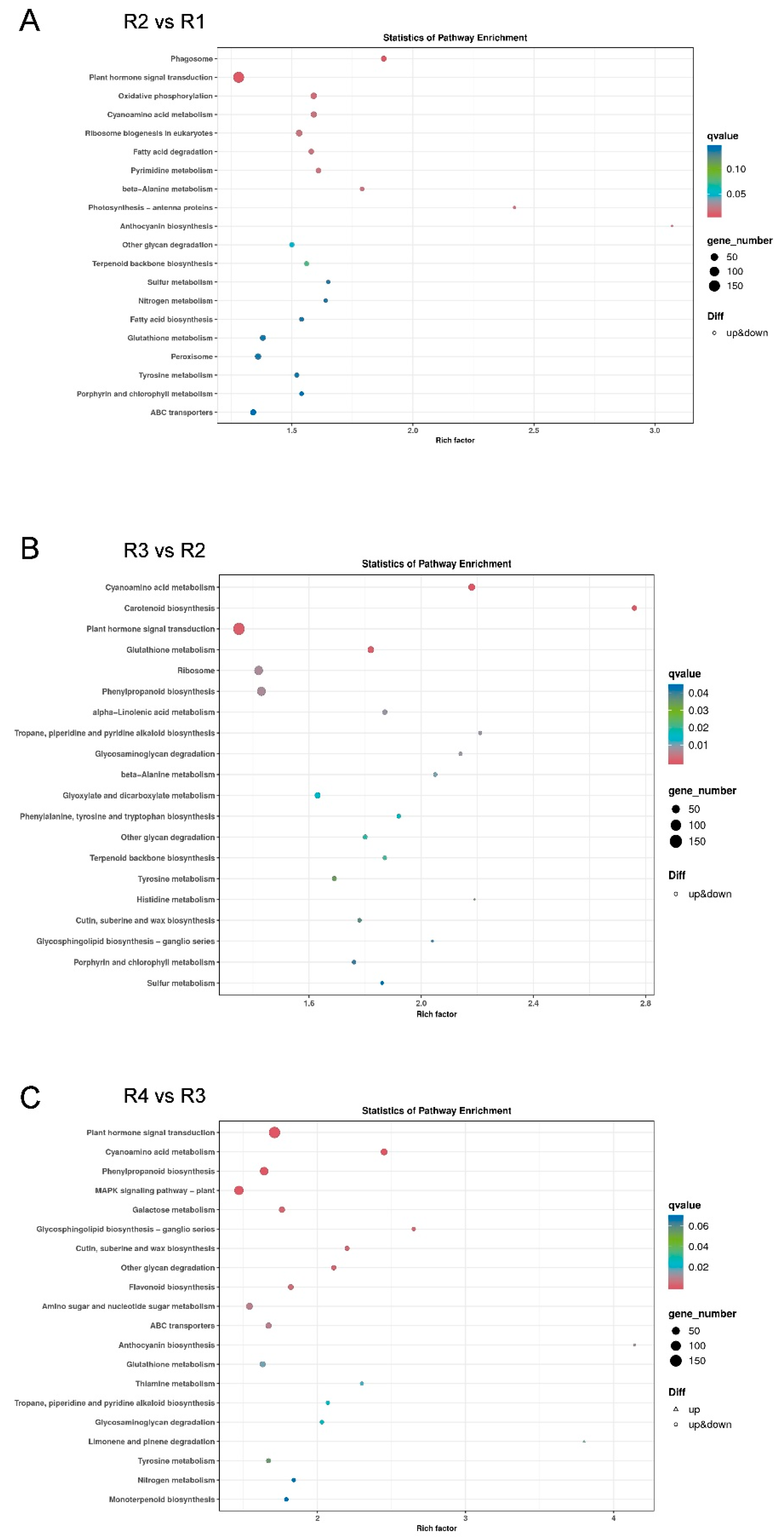

3.4. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Analysis of DEGs

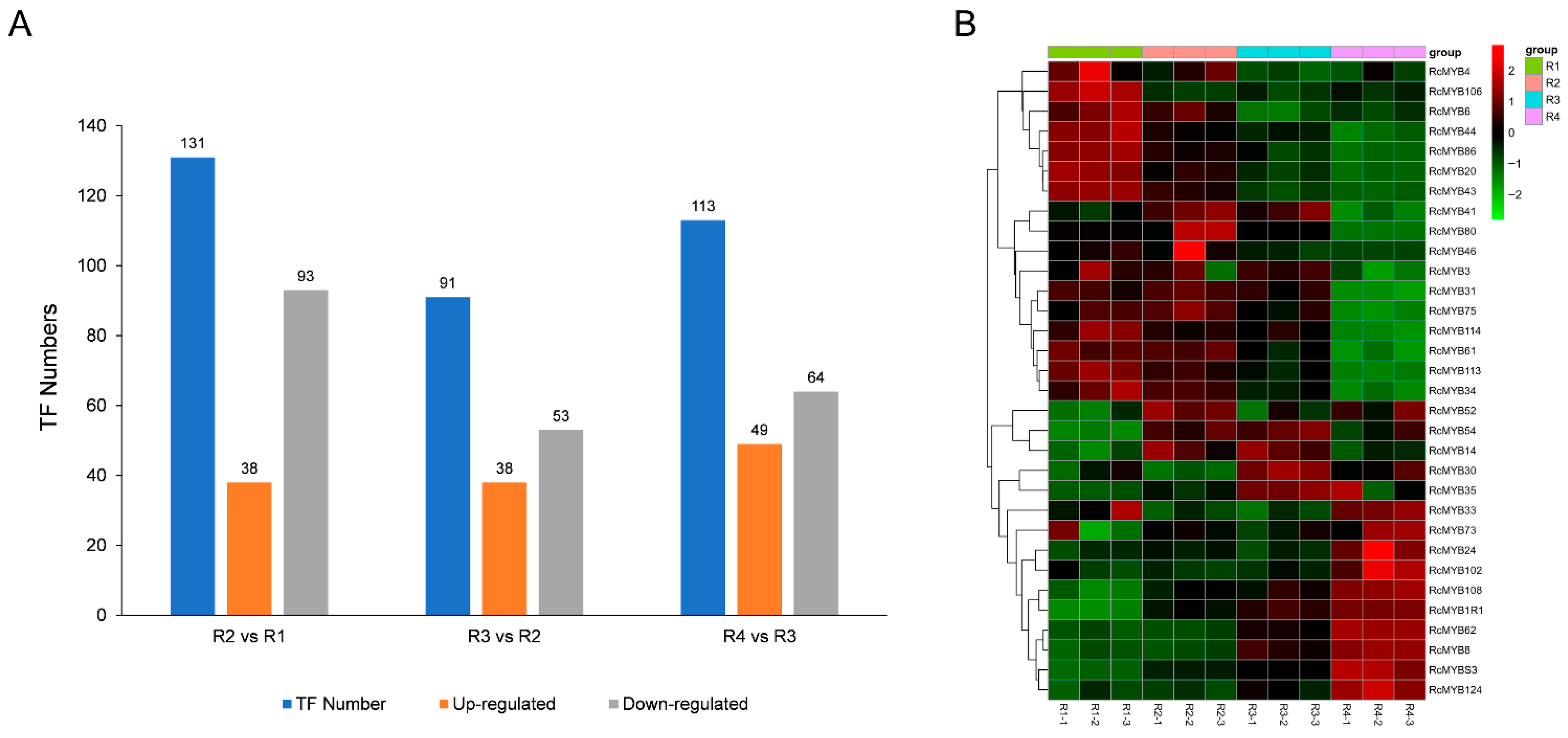

3.5. Transcription Factors (TFs) Analysis

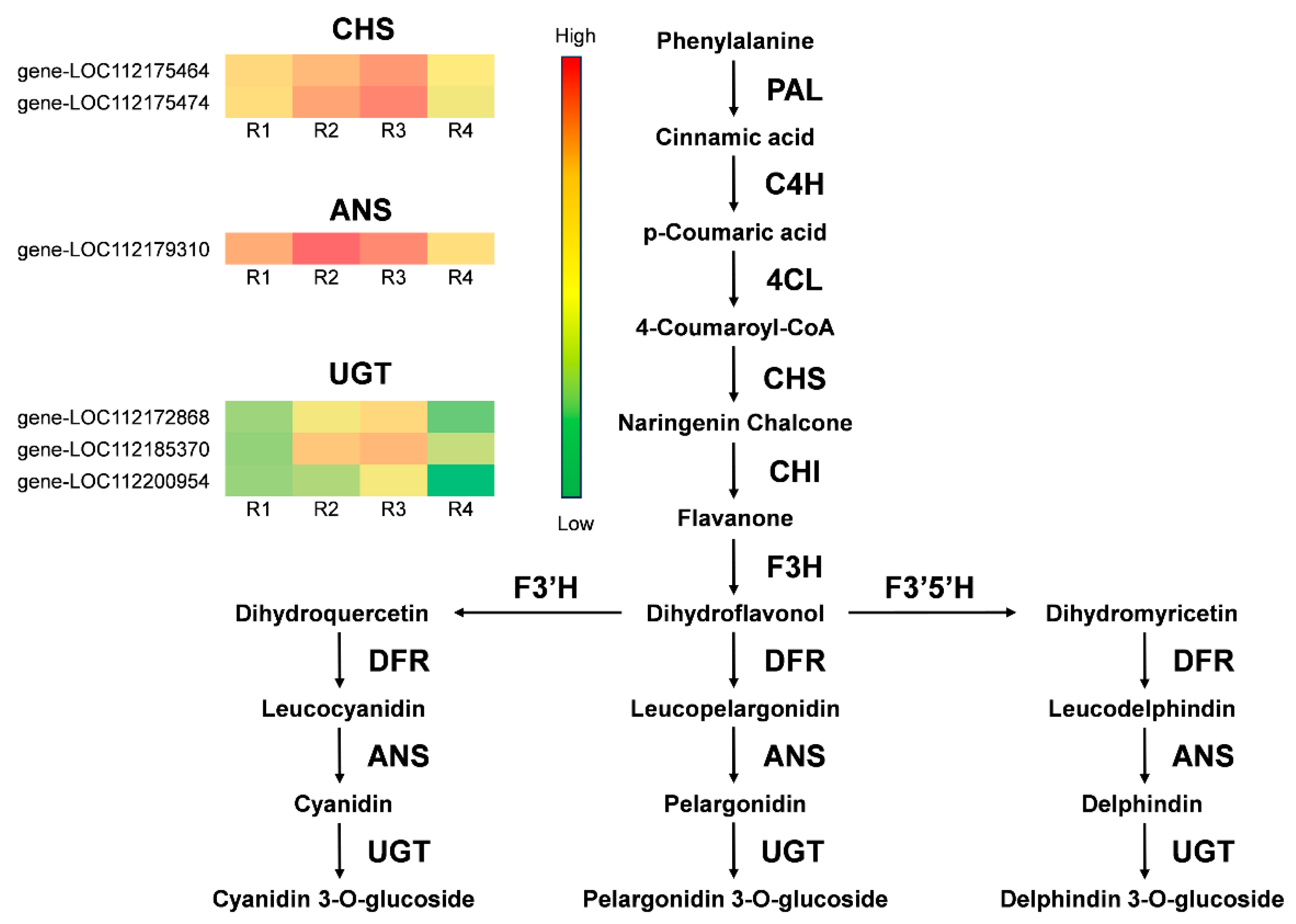

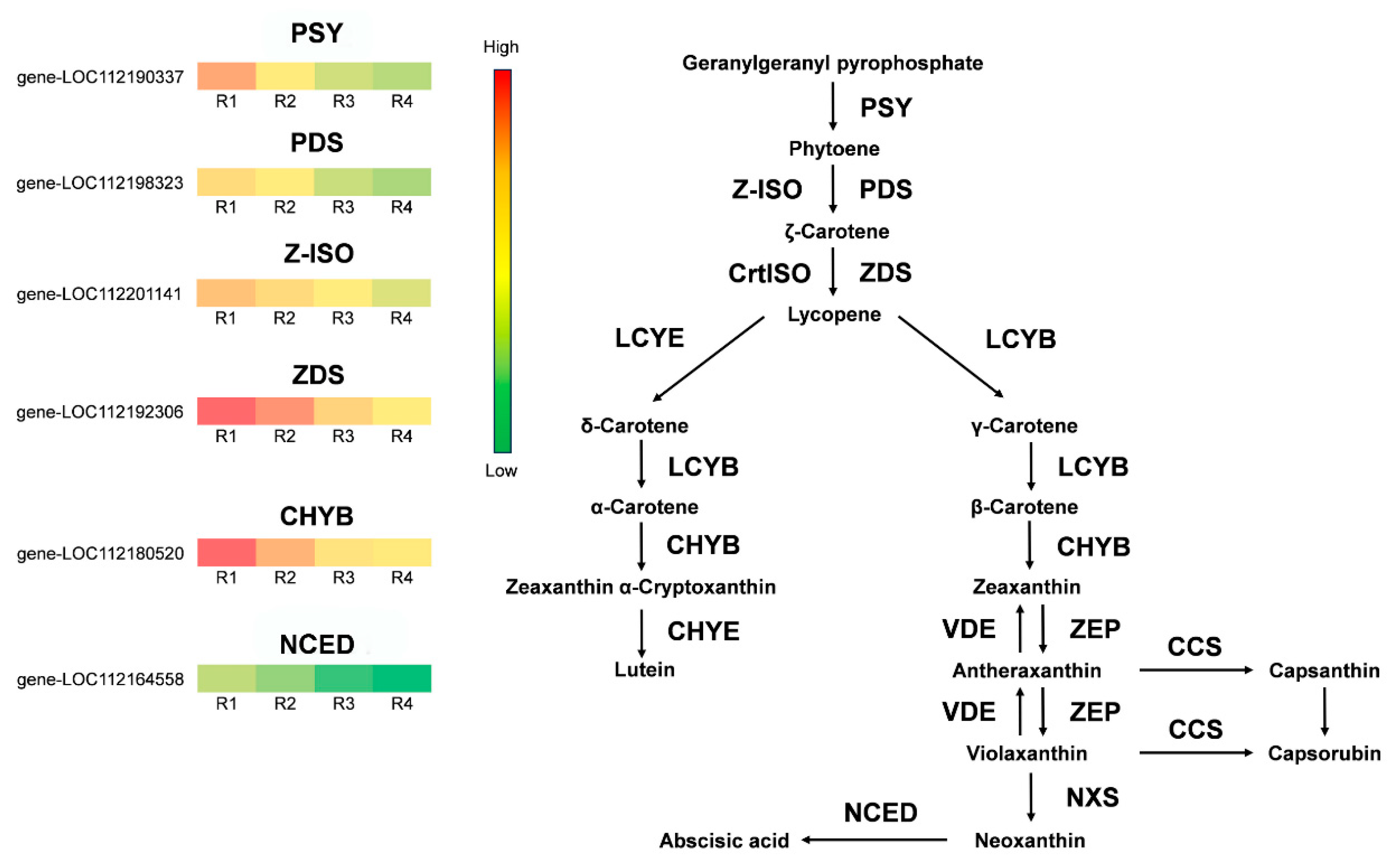

3.6. Differential Expression Gene Screening in the Anthocyanin and Carotenoid Biosynthetic Pathway

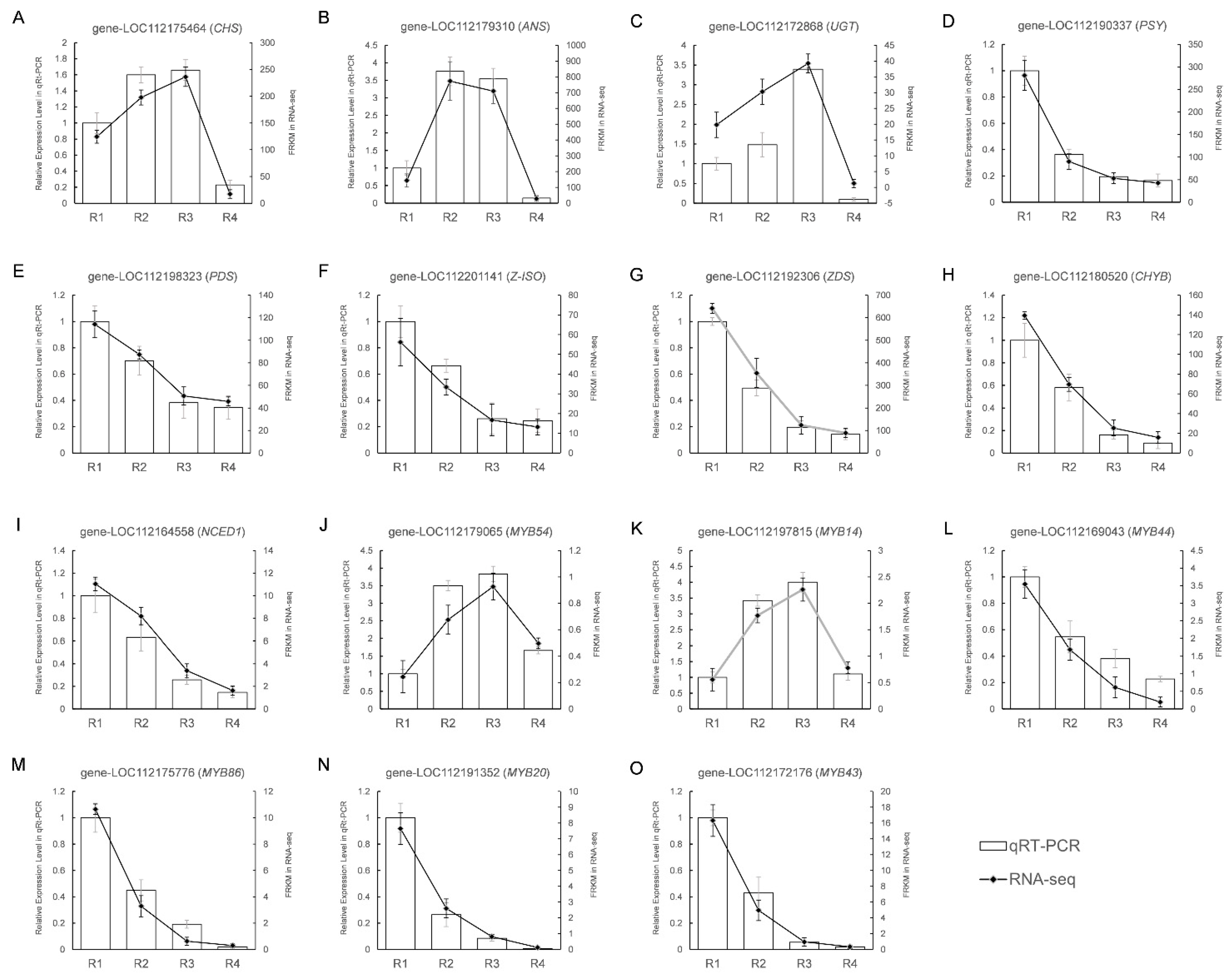

3.7. Verifying DEGs Expression in the Transcriptome Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Noman, A.; Aqeel, M.; Deng, J.; Khalid, N.; Sanaullah, T.; Shuilin, H. Biotechnological Advancements for Improving Floral Attributes in Ornamental Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Recinos, M.F.; Pucker, B. Genetic factors explaining anthocyanin pigmentation differences. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugliera, F.; Tao, G.Q.; Tems, U.; Kalc, G.; Mouradova, E.; Price, K.; Stevenson, K.; Nakamura, N.; Stacey, I.; Katsumoto, Y.; et al. Violet/blue chrysanthemums—metabolic engineering of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway results in novel petal colors. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 1696–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.J.; Möller, M.; Luo, Y.H.; Zou, J.Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Y.H.; Liu, J.; Zhu, A.D.; Hu, J.Y.; Li, D.Z.; et al. Differential expressions of anthocyanin synthesis genes underlie flower color divergence in a sympatric Rhododendron sanguineum complex. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, W.W.; Smith, S.D. Molecular evolution of anthocyanin pigmentation genes following losses of flower color. BMC Evol. Biol. 2016, 16, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Rao, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, L. Plant carotenoids: Recent advances and future perspectives. Mol. Hortic. 2022, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacson, T.; Ronen, G.; Zamir, D.; Hirschberg, J. Cloning of tangerine from tomato reveals a carotenoid isomerase essential for the production of beta-carotene and xanthophylls in plants. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zheng, T.; Yang, Y.; Li, P.; Qiu, L.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Q. Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Overexpression of MYB Transcription Factors on the Regulatory Mechanisms of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 781343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Cui, Y.; Yao, Y.; An, L.; Bai, Y.; Li, X.; Yao, X.; Wu, K. Genome-wide identification of WD40 transcription factors and their regulation of the MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complex related to anthocyanin synthesis in Qingke (Hordeum vulgare, L. var. nudum Hook. f.). BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liang, S.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Ma, N.; Zhou, X. The transcription factor RhMYB17 regulates the homeotic transformation of floral organs in rose (Rosa hybrida) under cold stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 2965–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zou, X.; Liang, Z.; Wu, D.; He, J.; Xie, K.; Jin, H.; Wang, H.; Shen, Q. Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal molecular response of anthocyanins biosynthesis in perilla to light intensity. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 976449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Lin-Wang, K.; Zhu, J.; Bi, Z.; Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; Bai, J. Integrative analysis of metabolome and transcriptome reveals a dynamic regulatory network of potato tuber pigmentation. iScience 2023, 26, 105903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, N.W.; Davies, K.M.; Lewis, D.H.; Zhang, H.; Montefiori, M.; Brendolise, C.; Boase, M.R.; Ngo, H.; Jameson, P.E.; Schwinn, K.E. A conserved network of transcriptional activators and repressors regulates anthocyanin pigmentation in eudicots. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 962–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, S.; Wang, H.; Ming, F. The MYB transcription factor RcMYB1 plays a central role in rose anthocyanin biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Zhou, H.; Ren, T.; Yu, E.R.; Feng, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, C.; Li, Y. Integrated transcriptome and metabolome analysis revealed that HaMYB1 modulates anthocyanin accumulation to deepen sunflower flower color. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, S.; Ohmiya, A. Carotenoid isomerase is key determinant of petal color of Calendula officinalis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kljak, K.; Carovic-Stanko, K.; Kos, I.; Janjecic, Z.; Kis, G.; Duvnjak, M.; Safner, T.; Bedekovic, D. Plant Carotenoids as Pigment Sources in Laying Hen Diets: Effect on Yolk Color, Carotenoid Content, Oxidative Stability and Sensory Properties of Eggs. Foods 2021, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Liang, F.; Qin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cong, R.; Xin, H.; Zhang, Z. Carotenoid metabolite and transcriptome dynamics underlying flower color in marigold (Tagetes erecta L.). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Sun, L.; Song, S.; Sun, Y.; Fan, X.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Sun, H. Integrated metabolome and transcriptome analysis of anthocyanin accumulation during the color formation of bicolor flowers in Eustoma grandiflorum. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 314, 111952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Joung, J.G.; McQuinn, R.; Chung, M.Y.; Fei, Z.; Tieman, D.; Klee, H.; Giovannoni, J. Combined transcriptome, genetic diversity and metabolite profiling in tomato fruit reveals that the ethylene response factor SlERF6 plays an important role in ripening and carotenoid accumulation. Plant J. 2012, 70, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Q.; Asim, M.; Zhang, R.; Khan, R.; Farooq, S.; Wu, J. Transcription Factors Interact with ABA through Gene Expression and Signaling Pathways to Mitigate Drought and Salinity Stress. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Kang, K.; Shim, Y.; Yoo, S.C.; Paek, N.C. Inactivating transcription factor OsWRKY5 enhances drought tolerance through abscisic acid signaling pathways. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 1900–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Debnath, P.; Roohi Sane, A.P.; Sane, V.A. Expression of the tomato WRKY gene, SlWRKY23, alters root sensitivity to ethylene, auxin and JA and affects aerial architecture in transgenic Arabidopsis. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Huang, J.; Lei, S.K.; Sun, X.G.; Li, X. Comparative gene expression profile analysis of ovules provides insights into Jatropha curcas, L. ovule development. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, K.; Chen, M.; Su, W.; Liu, Z.; Guo, X.; Ma, M.; Qian, S.; Deng, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. ALLENE OXIDE SYNTHASE (AOS) induces petal senescence through a novel JA-associated regulatory pathway in Arabidopsis. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 30, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.Y.; Shin, J.Y.; Ahn, M.S.; Kim, S.J.; An, H.R.; Kim, Y.J.; Kwon, O.H.; Lee, S.Y. Callus Derived from Petals of the Rosa hybrida Breeding Line 15R-12-2 as New Material Useful for Fragrance Production. Plants 2023, 12, 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simin, N.; Zivanovic, N.; Bozanic Tanjga, B.; Lesjak, M.; Narandzic, T.; Ljubojevic, M. New Garden Rose (Rosa x hybrida) Genotypes with Intensely Colored Flowers as Rich Sources of Bioactive Compounds. Plants 2024, 13, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, Y.; Ren, J.; Chen, Z.; Shi, D. Integrated transcriptome and metabolome analyses provide molecular insights into the transition of flower color in the rose cultivar ‘Juicy Terrazza’. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Hu, C.; Xie, C.; Lu, A.; Luo, Y.; Peng, T.; Huang, W. Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis Reveal the Role of Metabolites and Genes in Modulating Flower Color of Paphiopedilum micranthum. Plants 2023, 12, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-J.; Zheng, B.-Q.; Wang, J.-Y.; Tsai, W.-C.; Lu, H.-C.; Zou, L.-H.; Wan, X.; Zhang, D.-Y.; Qiao, H.-J.; Liu, Z.-J.; et al. New insight into the molecular mechanism of colour differentiation among floral segments in orchids. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Peacock, A.D.; White, D.C.; Lytle, C.; Van Berkel, G.J. Atmospheric pressure chemical ionization and atmospheric pressure photoionization for simultaneous mass spectrometric analysis of microbial respiratory ubiquinones and menaquinones. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2004, 39, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Ferrars, R.M.; Czank, C.; Saha, S.; Needs, P.W.; Zhang, Q.; Raheem, K.S.; Botting, N.P.; Kroon, P.A.; Kay, C.D. Methods for isolating, identifying, and quantifying anthocyanin metabolites in clinical samples. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 10052–10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Yeo, H.J.; Kim, N.S.; Park, Y.E.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Park, S.U. Metabolomic Profiling of the White, Violet, and Red Flowers of Rhododendron schlippenbachii Maxim. Molecules 2018, 23, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.-M.; Chia, L.-S.; Goh, N.-K.; Chia, T.-F.; Brouillard, R. Corrigendum to “Analysis and biological activities of anthocyanins” [Phytochemistry 64 (2003) 923–933]. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 1939–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhu, P. Simultaneous changes in anthocyanin, chlorophyll, and carotenoid contents produce green variegation in pink-leaved ornamental kale. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Zhu, C.; Fan, Z.; Huang, M.; Lin, H.; Chen, X.; Deng, C.; Chen, Y.; Kou, Y.; Tong, Z.; et al. Comprehensive metabolome and transcriptome analyses demonstrate divergent anthocyanin and carotenoid accumulation in fruits of wild and cultivated loquats. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1285456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, L.; Qiang, X.; Meng, Y.; Li, Z.; Huang, F. Integrated Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Profiles Provide Insights into the Mechanisms of Anthocyanin and Carotenoid Biosynthesis in Petals of Medicago sativa ssp. sativa and Medicago sativa ssp. falcata. Plants 2024, 13, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ma, X.; Gao, X.; Wu, W.; Zhou, B. Light Induced Regulation Pathway of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quian-Ulloa, R.; Stange, C. Carotenoid Biosynthesis and Plastid Development in Plants: The Role of Light. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takos, A.M.; Jaffe, F.W.; Jacob, S.R.; Bogs, J.; Robinson, S.P.; Walker, A.R. Light-induced expression of a MYB gene regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 1216–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Gu, C.; Wang, X.; Gao, S.; Li, C.; Zhao, C.; Li, C.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Q. Identification of the Eutrema salsugineum EsMYB90 gene important for anthocyanin biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, G.; Bartley, G.E.; Scolnik, P.A. Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis during tomato development. Plant Cell 1993, 5, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Y.; Rao, D.; Wu, E.; Gan, R.; Li, T.; Tian, M. High-density genetic map construction using whole-genome resequencing of the Cymbidium eburneum (‘Duzhan Chun’) x Cymbidium insigne (‘Meihua Lan’) F1 population and localization of flower color genes. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1685531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Peng, Y.; Li, Z. Uncovering Hierarchical Regulation among MYB-bHLH-WD40 Proteins and Manipulating Anthocyanin Pigmentation in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, B.; Gu, G.; Yuan, J.; Shen, S.; Jin, L.; Lin, Z.; Lin, J.; Xie, X. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the R2R3-MYB gene family in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagawa, J.M.; Stanley, L.E.; LaFountain, A.M.; Frank, H.A.; Liu, C.; Yuan, Y.W. An R2R3-MYB transcription factor regulates carotenoid pigmentation in Mimulus lewisii flowers. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, C.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, H. MYB transcription factor PdMYB118 directly interacts with bHLH transcription factor PdTT8 to regulate wound-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in poplar. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Huang, Y.; Ma, T.; Ma, X.; Li, R.; Shen, J.; Wen, J. BnaABF3 and BnaMYB44 regulate the transcription of zeaxanthin epoxidase genes in carotenoid and abscisic acid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 2372–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.M.; Zhang, W.; Tu, M.; Zhang, S.B. Spatial and Temporal Regulation of Flower Coloration in Cymbidium lowianum. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 3844–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metabolites Class | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanidin | 13.71% | 36.41% | 72.03% | 83.69% |

| Delphinidin | 0.70% | 0.40% | 0.48% | 0.46% |

| Malvidin | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% |

| Pelargonidin | 2.33% | 8.11% | 10.65% | 12.19% |

| Peonidin | 0.13% | 0.17% | 0.64% | 0.59% |

| Petunidin | N/A | N/A | 0.01% | 0.01% |

| Carotenes | 5.31% | 1.90% | 0.37% | 0.25% |

| Xanthophylls | 77.80% | 53.00% | 15.81% | 2.80% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, J.; Ren, F.; Meng, X.; Dong, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal the Molecular Mechanism of Flower Color Variations in Rosa chinensis Cultivar ‘Rainbow’s End’. Metabolites 2026, 16, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010032

Sun J, Ren F, Meng X, Dong G, Zhang X, Li Y. Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal the Molecular Mechanism of Flower Color Variations in Rosa chinensis Cultivar ‘Rainbow’s End’. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Junfei, Fengshan Ren, Xianshui Meng, Guizhi Dong, Xiaohong Zhang, and Yi Li. 2026. "Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal the Molecular Mechanism of Flower Color Variations in Rosa chinensis Cultivar ‘Rainbow’s End’" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010032

APA StyleSun, J., Ren, F., Meng, X., Dong, G., Zhang, X., & Li, Y. (2026). Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal the Molecular Mechanism of Flower Color Variations in Rosa chinensis Cultivar ‘Rainbow’s End’. Metabolites, 16(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010032