Metabolomics Plasma Biomarkers Associated with the HRD Phenotype in Ovarian Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Sample Materials and Sample Preparation

2.3. 1H-NMR Spectroscopy

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. NMR Analysis on Basal Serum Samples of OT Patients and Healthy Donors

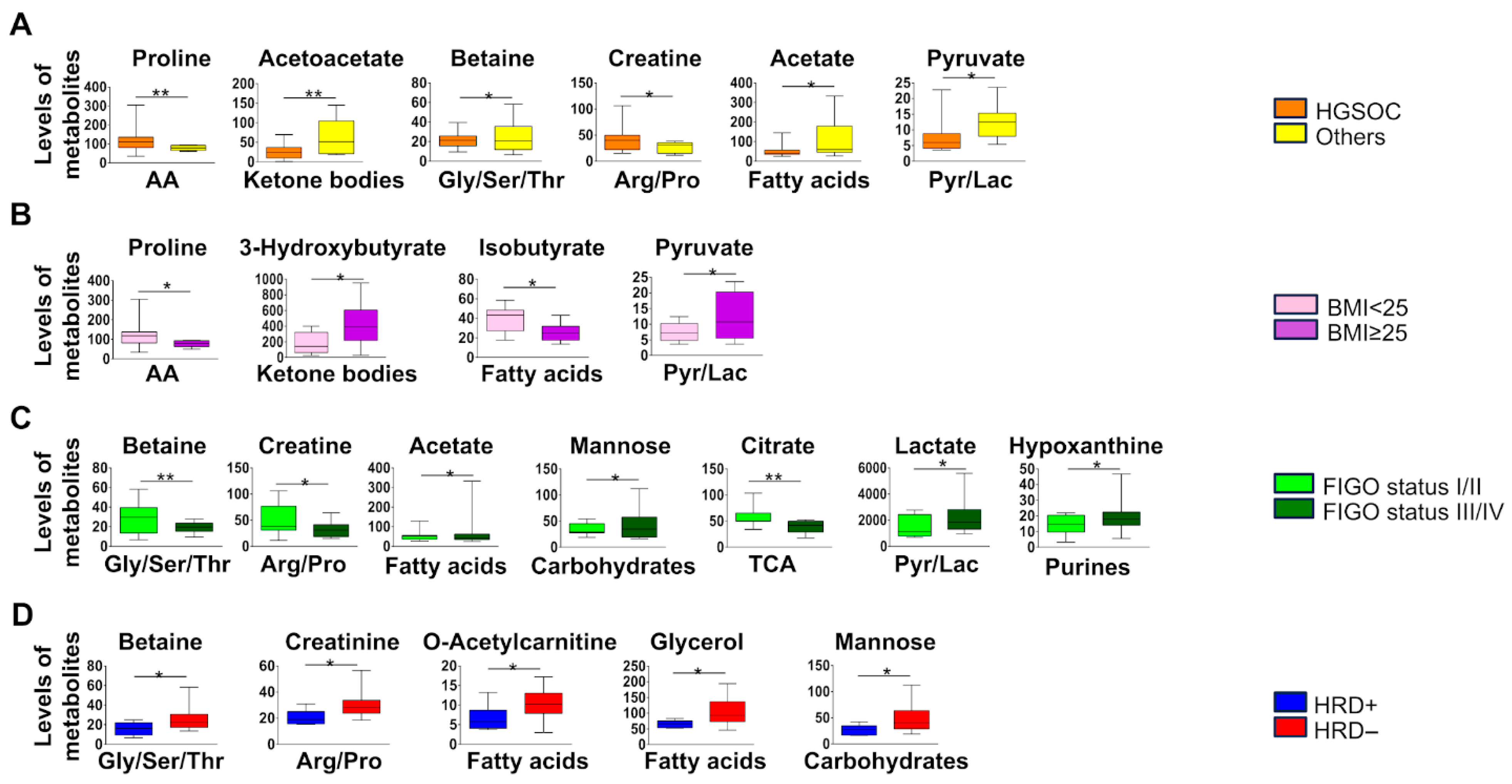

3.2. Metabolic Profile in Malignant OC Patients

3.3. Metabolic Profile in HRD-Positive Malignant OC Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | body mass index |

| CNTR | control |

| CT | chemotherapy |

| FC | fold change |

| HGEOC | high-grade endometroid carcinoma |

| HGSOC | high-grade serous carcinoma |

| H-NMR | nuclear magnetic resonance |

| PCD | programmed cell death |

| HRD | homologous recombination deficiency |

| OC | ovarian cancer |

| OCB | benign ovarian cancer |

| OCM | malignant ovarian cancer |

| OT | ovarian tumor |

| PC | principal component |

| PLS-DA | partial least squares discriminant analysis |

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424, Erratum in CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 313. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Caruso, G.; Weroha, S.J.; Cliby, W. Ovarian Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2025, 334, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledermann, J.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Amant, F.; Concin, N.; Davidson, B.; Fotopoulou, C.; González-Martin, A.; Gourley, C.; Leary, A.; Lorusso, D.; et al. ESGO–ESMO–ESP consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: Pathology and molecular biology and early, advanced and recurrent disease. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Martín, A.; Harter, P.; Leary, A.; Lorusso, D.; Miller, R.; Pothuri, B.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Tan, D.; Bellet, E.; Oaknin, A.; et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; Ceccaldi, R.; Shapiro, G.I.; D’Andrea, A.D. Homologous Recombination Deficiency: Exploiting the Fundamental Vulnerability of Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1137–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Petrillo, M.; Anchora, L.P.; Scambia, G.; Fagotti, A. Cytoreductive Surgery Plus Platinum-Based Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: A Promising Integrated Approach to Improve Locoregional Control. Oncologist 2016, 21, 532–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ray-Coquard, I.; Pautier, P.; Pignata, S.; Pérol, D.; González-Martín, A.; Berger, R.; Fujiwara, K.; Vergote, I.; Colombo, N.; Mäenpää, J.; et al. Olaparib plus Bevacizumab as First-Line Maintenance in Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2416–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín, A.; Pothuri, B.; Vergote, I.; DePont Christensen, R.; Graybill, W.; Mirza, M.R.; McCormick, C.; Lorusso, D.; Hoskins, P.; Freyer, G.; et al. Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2391–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; Colombo, N.; Scambia, G.; Kim, B.-G.; Oaknin, A.; Friedlander, M.; Lisyanskaya, A.; Floquet, A.; Leary, A.; Sonke, G.S.; et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, B.J.; Parkinson, C.A.; Lim, M.C.; O’Malley, D.M.; Oaknin, A.; Wilson, M.K.; Coleman, R.L.; Lorusso, D.; Bessette, P.; Ghamande, S. A randomized, phase III trial to evaluate rucaparib monotherapy as maintenance treatment in patients with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer (ATHENA-MONO/GOG-3020/ENGOT-ov45). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3952–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.L.; Oza, A.M.; Lorusso, D.; Aghajanian, C.; Oaknin, A.; Dean, A.; Colombo, N.; Weberpals, J.I.; Clamp, A.; Scambia, G.; et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1949–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.R.; Monk, B.J.; Herrstedt, J.; Oza, A.M.; Mahner, S.; Redondo, A.; Fabbro, M.; Ledermann, J.A.; Lorusso, D.; Vergote, I.; et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2154–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Ledermann, J.A.; Selle, F.; Gebski, V.; Penson, R.T.; Oza, A.M.; Korach, J.; Huzarski, T.; Poveda, A.; Pignata, S.; et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempel, E.; Kluck, K.; Beck, S.; Ourailidis, I.; Kazdal, D.; Neumann, O.; Volckmar, A.L.; Kirchner, M.; Goldschmid, H.; Pfarr, N.; et al. Pan-cancer analysis of genomic scar patterns caused by homologous repair deficiency (HRD). npj Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coleman, R.L.; Fleming, G.F.; Brady, M.F.; Swisher, E.M.; Steffensen, K.D.; Friedlander, M.; Okamoto, A.; Moore, K.N.; Efrat Ben-Baruch, N.; Werner, T.L.; et al. Veliparib with First-Line Chemotherapy and as Maintenance Therapy in Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2403–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Turkoglu, O.; Zeb, A.; Graham, S.; Szyperski, T.; Szender, J.B.; Odunsi, K.; Bahado-Singh, R. Metabolomics of biomarker discovery in ovarian cancer: A systematic review of the current literature. Metabolomics 2016, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahmed-Salim, Y.; Galazis, N.; Bracewell-Milnes, T.; Phelps, D.L.; Jones, B.P.; Chan, M.; Munoz-Gonzales, M.D.; Matsuzono, T.; Smith, J.R.; Yazbek, J.; et al. The application of metabolomics in ovarian cancer management: A systematic review. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 754–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, D.; Lai, Z.; Dearden, S.; Barrett, J.; Harrington, E.; Timms, K.; Lanchbury, J.; Wu, W.; Allen, A.; Senkus, E.; et al. Analysis of mutation status and homologous recombination deficiency in tumors of patients with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and metastatic breast cancer: OlympiAD. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, H.Y.; Purcell, E.M. Effects of Diffusion on Free Precession in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Experiments. Phys. Rev. J. 1954, 94, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, J.A.; Nilsson, M.; Bodenhausen, G.; Morris, G.A. Spin echo NMR spectra without J modulation. Chem. Commun. 2011, 48, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, J.A.; Cassani, J.; Probert, F.; Palace, J.; Claridge, T.D.W.; Botana, A.; Kenwright, A.M. Reliable, high-quality suppression of NMR signals arising from water and macromolecules: Application to bio-fluid analysis. Analyst 2019, 144, 7270–7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasso, D.; Pillozzi, S.; Tazza, I.; Bertelli, M.; Campanacci, D.A.; Palchetti, I.; Bernini, A. An improved NMR approach for metabolomics of intact serum samples. Anal. Biochem. 2022, 654, 114826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Chong, J.; Zhou, G.; de Lima Morais, D.A.; Chang, L.; Barrette, M.; Gauthier, C.; Jacques, P.-É.; Li, S.; Xia, J.; et al. MetaboAnalyst 5.0: Narrowing the gap between raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W388–W396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, N.N.; Thompson, C.B. The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- D’Aniello, C.; Patriarca, E.J.; Phang, J.M.; Minchiotti, G. Proline Metabolism in Tumor Growth and Metastatic Progression. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee-Rueckert, M.; Canyelles, M.; Tondo, M.; Rotllan, N.; Kovanen, P.T.; Llorente-Cortes, V.; Escolà-Gil, J.C. Obesity-induced changes in cancer cells and their microenvironment: Mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives to manage dysregulated lipid metabolism. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 93, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Li, X.; Ren, A.; Du, M.; Du, H.; Shu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, W. Choline and betaine consumption lowers cancer risk: A meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kotsopoulos, J.; Hankinson, S.E.; Tworoger, S.S. Dietary betaine and choline intake are not associated with risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kar, F.; Hacioglu, C.; Kacar, S.; Sahinturk, V.; Kanbak, G. Betaine suppresses cell proliferation by increasing oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis and inflammation in DU-145 human prostate cancer cell line. Cell Stress Chaperones 2019, 24, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lafleur, J.; Hefler-Frischmuth, K.; Grimm, C.; Schwameis, R.; Gensthaler, L.; Reiser, E.; Hefler, L.A. Prognostic Value of Serum Creatinine Levels in Patients with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 5127–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rosa, S.; Greco, M.; Rauseo, M.; Annetta, M.G. The Good, the Bad, and the Serum Creatinine: Exploring the Effect of Muscle Mass and Nutrition. Blood Purif. 2023, 52, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peng, Z.; Saito, S. Creatine supplementation enhances anti-tumor immunity by promoting adenosine triphosphate production in macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1176956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, L.; Bu, P. The two sides of creatine in cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2022, 32, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atallah, G.A.; Abd Aziz, N.H.; Teik, C.K.; Shafiee, M.N.; Kampan, N.C. New Predictive Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancer. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Lv, X.; Gao, Y.; Guo, Q.; Ren, Y.; He, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; et al. CRAT downregulation promotes ovarian cancer progression by facilitating mitochondrial metabolism through decreasing the acetylation of PGC-1α. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mukherjee, A.; Bezwada, D.; Greco, F.; Zandbergen, M.; Shen, T.; Chiang, C.-Y.; Tasdemir, M.; Fahrmann, J.; Grapov, D.; La Frano, M.R.; et al. Adipocytes reprogram cancer cell metabolism by diverting glucose towards glycerol-3-phosphate thereby promoting metastasis. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 1563–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marchan, R.; Büttner, B.; Lambert, J.; Edlund, K.; Glaeser, I.; Blaszkewicz, M.; Leonhardt, G.; Marienhoff, L.; Kaszta, D.; Anft, M.; et al. Glycerol-3-phosphate Acyltransferase 1 Promotes Tumor Cell Migration and Poor Survival in Ovarian Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 4589–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, P. HPLC for simultaneous quantification of free mannose and glucose concentrations in serum: Use in detection of ovarian cancer. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1289211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Allavena, P.; Chieppa, M.; Bianchi, G.; Solinas, G.; Fabbri, M.; Laskarin, G.; Mantovani, A. Engagement of the mannose receptor by tumoral mucins activates an immune suppressive phenotype in human tumor-associated macrophages. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2010, 2010, 547179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jaynes, J.M.; Sable, R.; Ronzetti, M.; Bautista, W.; Knotts, Z.; Abisoye-Ogunniyan, A.; Li, D.; Calvo, R.; Dashnyam, M.; Singh, A.; et al. Mannose receptor (CD206) activation in tumor-associated macrophages enhances adaptive and innate antitumor immune responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaax6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Total Number Pts (%) = 24 (100%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 65 (84–43) |

| Stage | |

| I–II | 7 (29%) |

| III–IV | 17 (71%) |

| Histology | |

| HGSOC | 17 (71%) |

| HGEOC | 3 (13%) |

| Mucinous OC | 2 (8%) |

| Other histotypes | 2 (8%) |

| BRCA1/2 mutations/HRD-positive * | |

| Yes | 8 (40%) |

| gBRCA1/2 mutations | 3 (15%) |

| sBRCA1/2 mutations | 3 (15%) |

| HRD-positive | 2 (10%) |

| No | 12 (60%) |

| First-line Chemotherapy | 17 (71%) |

| Yes | 15 (63%) |

| Olaparib | 4 (17%) |

| Olaparib plus bevacizumab | 2 (8%) |

| Niraparib | 5 (21%) |

| Bevacizumab | 4 (17%) |

| No | 2 (8%) |

| BMI, median (range) | 24.3 (18.3–33.7) |

| BMI ≥ 25 | 10 (42%) |

| BMI < 25 | 14 (58%) |

| Blood glucose level > 100 mg/dL | 4 (17%) |

| Blood glucose level ≤ 100 mg/dL | 20 (83%) |

| Premenopausal | 4 (17%) |

| Postmenopausal | 20 (83%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes type 2 | 3 (13%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia/Hypertriglyceridemia | 5 (21%) |

| Hypertension | 5 (21%) |

| Hypothyroidism | 4 (17%) |

| Thromboembolism disorder | 3 (13%) |

| Drugs | |

| Metformin/SGL2 inhibitor | 3 (13%) |

| Antihypertensive | 10 (42%) |

| Statins/ezetimibe | 5 (21%) |

| β-blockers | 2 (8%) |

| Levothyroxine | 2 (8%) |

| PPI | 3 (13%) |

| Antidepressants | 5 (21%) |

| Antihormonal therapy | 1 (4%) |

| Bisphosphonates | 1 (4%) |

| IFN-γ | 1 (4%) |

| Immunosuppressants | 1 (4%) |

| Antiaggregants | 2 (8%) |

| Anticoagulants | 2 (8%) |

| FIGO-STATUS | HISTOLOGY | BRCA/HRD | BMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | Proline | Proline | ||

| Ketone bodies | Acetoacetate | |||

| Ketone bodies | 3-Hydroxibutirate | |||

| Gly/Ser/Thr | Betaine | Betaine | Betaine | |

| Arg/Pro | Creatine | Creatine | ||

| Arg/Pro | Creatinine | |||

| Fatty acids | Acetate | Acetate | ||

| Fatty acids | O-Acetyl-Carnitine | |||

| Fatty acids | Glycerol | Isobutirate | ||

| Carbohydrates | Mannose | Mannose | ||

| TCA | Citrate | |||

| Pyr/Lac | Lactate | |||

| Pyr/Lac | Pyruvate | Pyruvate | ||

| Purines | Hypoxanthine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tubita, A.; De Angelis, C.; Grasso, D.; Sorbi, F.; Castiglione, F.; Anela, L.; Petrella, M.C.; Fambrini, M.; Scolari, F.; Bernini, A.; et al. Metabolomics Plasma Biomarkers Associated with the HRD Phenotype in Ovarian Cancer. Metabolites 2026, 16, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010002

Tubita A, De Angelis C, Grasso D, Sorbi F, Castiglione F, Anela L, Petrella MC, Fambrini M, Scolari F, Bernini A, et al. Metabolomics Plasma Biomarkers Associated with the HRD Phenotype in Ovarian Cancer. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleTubita, Alessandro, Claudia De Angelis, Daniela Grasso, Flavia Sorbi, Francesca Castiglione, Lorenzo Anela, Maria Cristina Petrella, Massimiliano Fambrini, Federico Scolari, Andrea Bernini, and et al. 2026. "Metabolomics Plasma Biomarkers Associated with the HRD Phenotype in Ovarian Cancer" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010002

APA StyleTubita, A., De Angelis, C., Grasso, D., Sorbi, F., Castiglione, F., Anela, L., Petrella, M. C., Fambrini, M., Scolari, F., Bernini, A., Petroni, G., Pillozzi, S., & Antonuzzo, L. (2026). Metabolomics Plasma Biomarkers Associated with the HRD Phenotype in Ovarian Cancer. Metabolites, 16(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010002