Impact of Stress on Adrenal and Neuroendocrine Responses, Body Composition, and Physical Performance Amongst Women in Demanding Tactical Occupations: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

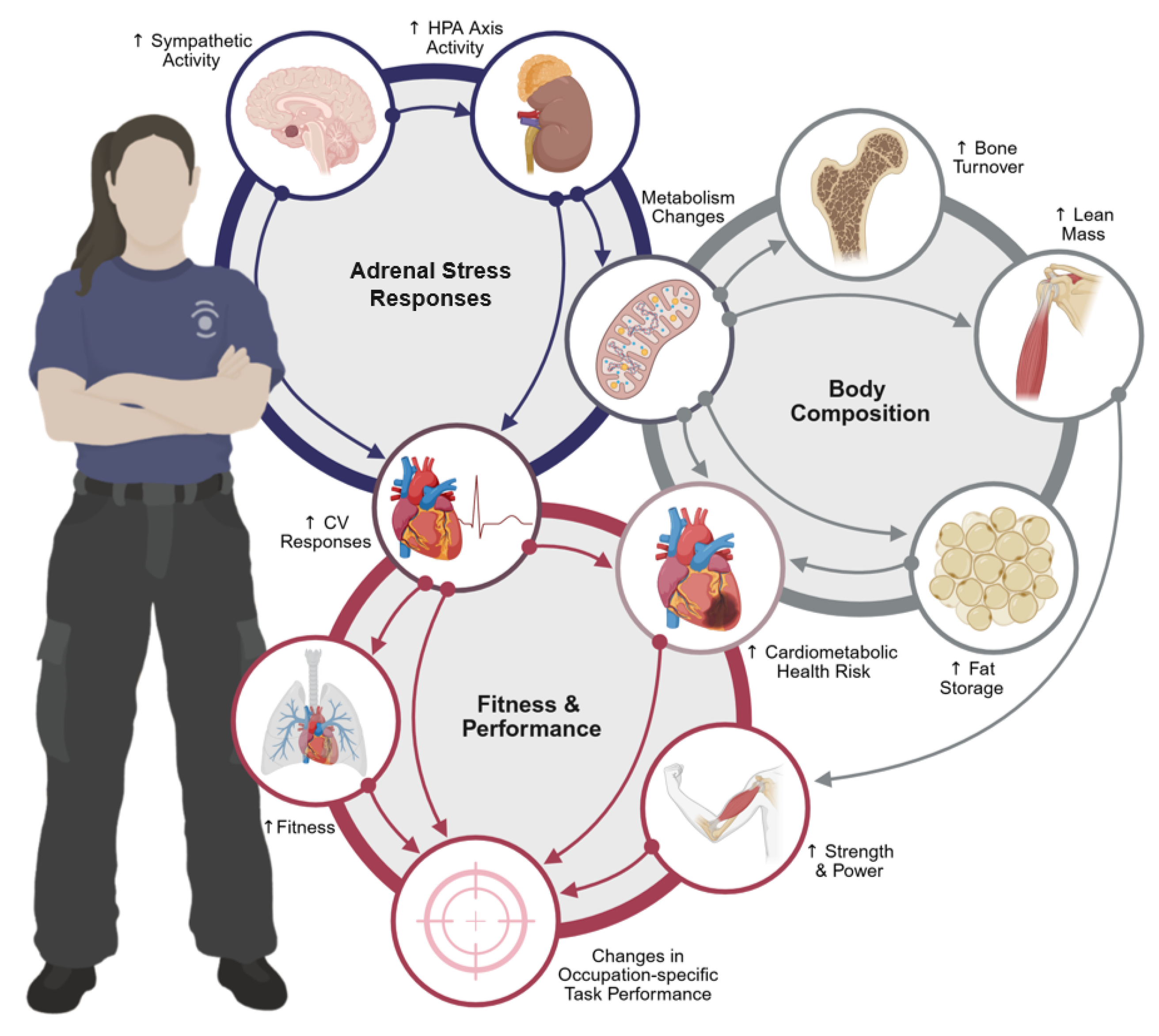

3.2. Adrenal Stress and Neuroendocrine Responses

3.3. Body Composition

3.4. Occupational Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Adrenal Stress Response

4.2. Body Composition

4.3. Occupational Performance

4.4. Limitations

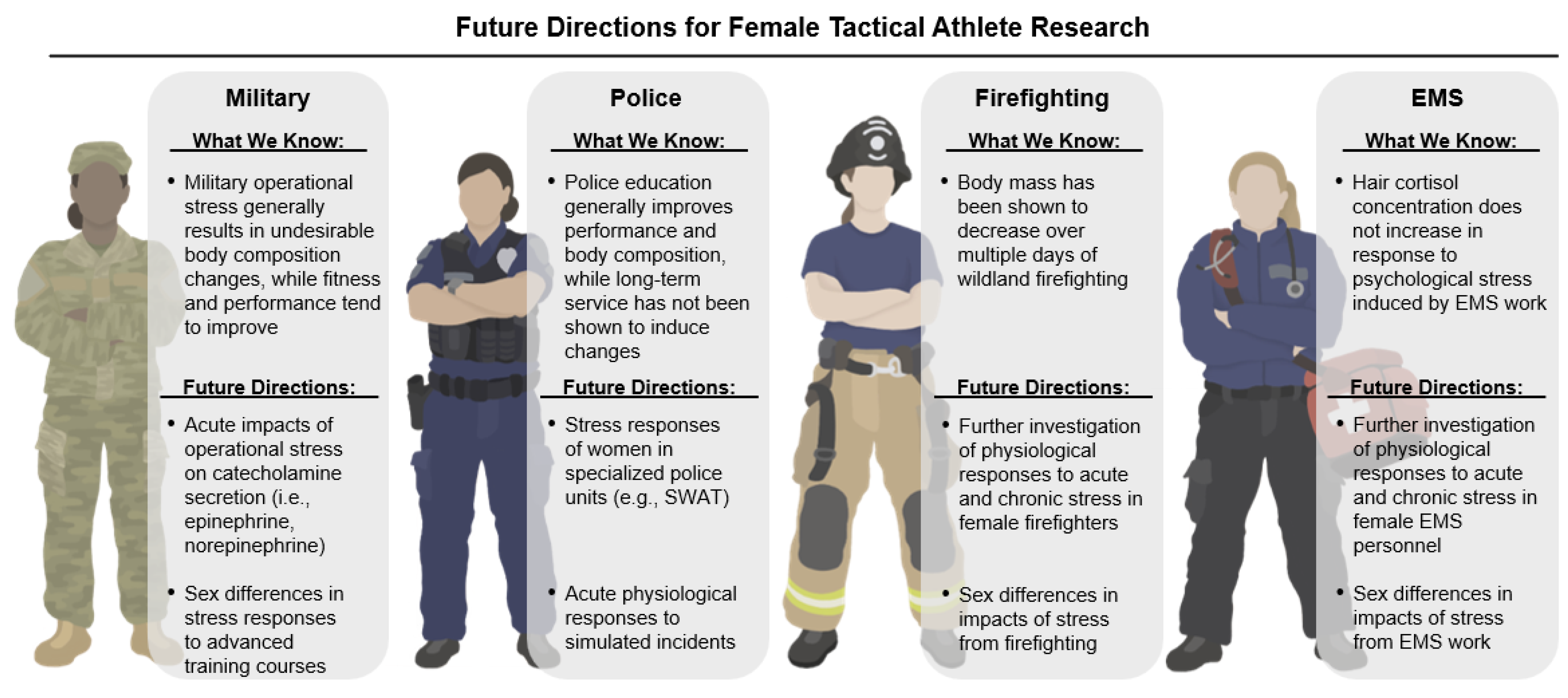

4.5. Evidence-Informed Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BF | Body fat |

| BM | Body mass |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BMM | Bone mineral mass |

| CCP | Combined contraceptive pill |

| CFT | Combat fitness test |

| CK | Creatine kinase |

| CMJ | Countermovement jump |

| CMJREL | CMJ relative to body mass |

| COCP | Combined oral contraceptive |

| CRH | Corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CTT-2 | Color trails test |

| CTx | C-telopeptide cross-links of type I collagen |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| DHEA | Dihydroepiandrostenedione |

| DHEA-S | Dihydroepiandrostenedione sulfate |

| DLM | Dry lean mass |

| DLW | Doubly labeled water |

| DXA | Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| EEREL | Energy expenditure relative to body mass |

| EMS | Emergency medical services |

| F | Female |

| FAI | Free androgen index |

| FFA | Free fatty acids |

| FFM | Fat-free mass |

| FM | Fat mass |

| FSH | Follicle-stimulating hormone |

| GnRH | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GPX | Glutathione peroxidase |

| HCC | Hair cortisol concentration |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| HOMA2 IR | Homeostatic modeling assessment of insulin resistance 2 |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| HPG | Hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal |

| HPO | Hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian |

| HR | Heart rate |

| HRV | Heart rate variability |

| IFN-γ | Interferon γ |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor |

| LEA | Low energy availability |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| REDs | Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

| U.S. | United States |

References

- Washington, D.L.; Farmer, M.M.; Mor, S.S.; Canning, M.; Yano, E.M. Assessment of the healthcare needs and barriers to VA use experiences by women veterans: Findings from the national survey of women Veterans. Med. Care 2015, 53, S23–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, V. Gender Distribution of Full-Time U.S. Law Enforcement Employees in the United States in 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/195324/gender-distribution-of-full-time-law-enforcement-employees-in-the-us/ (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- McClung, H.L.; Spiering, B.A.; Bartlett, P.M.; Walker, L.A.; Lavoie, E.M.; Sanford, D.P.; Friedl, K.E. Physical and physiological characterization of female elite warfighters. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendel, E.; MacEachern, K.H.; Haxhiu, A.; Waruszynski, B.T. “Proud, brave, and tough”: Women in the Canadian combat arms. Front. Sociol. 2024, 9, 1304075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesniak, A.Y.; Bergstrom, H.C.; Clasey, J.L.; Stromberg, A.J.; Abel, M.G. The effect of personal protective equipment on firefighter occupational performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 2165–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, R.G.; Dawes, J.J.; Kornhauser, C.L.; Holmes, R.J. Cross-sectional and retrospective cohort analysis of the effects of age on flexibility, strength endurance, lower-body power, and aerobic fitness in law enforcement officers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, A.; Wiley, A.; Orr, R.M.; Schram, B.; Dawes, J.J. The impact of load carriage on measures of power and agility in tactical occupations: A critical review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; Chong, N.-S.; Zhang, M.; Agnew, R.J.; Xu, C.; Li, Z.; Xu, X. Face-to-face with scorching wildfire: Potential toxicant exposure and the health risks of smoke for wildland firefighters at the wildland-urban interface. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023, 21, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wei, B.; Zhu, H.; Wu, M.; Lan, X.; Yin, Q.; Cao, Y. High-altitude acute hypoxia endurance and comprehensive lung function in pilots. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 2025, 96, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; McLeod, E.; Périard, J.; Rattray, B.; Keegan, R.; Pyne, D.B. The impact of environmental stress on cognitive performance: A systematic review. Hum. Factors 2019, 61, 1205–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, E.A.; Chapman, C.L.; Castellani, J.W.; Looney, D.P. Energy expenditure during physical work in cold environments: Physiology and performance considerations for military service members. J. Appl. Physiol. 2024, 137, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyal, M.-A.A.; Smith, T.D.; DeJoy, D.M.; Moore, B.A. Occupational stress and burnout in the fire service: Examining the complex role and impact of sleep health. Behav. Modif. 2022, 46, 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purba, A.; Demou, E. The relationship between organisational stressors and mental well-being within police officers: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Violanti, J.M.; Charles, L.E.; McCanlies, E.; Hartley, T.A.; Baughman, P.; Andrew, M.E.; Fekedulegn, D.; Ma, C.C.; Mnatsakanova, A.; Burchfiel, C.M. Police stressors and health: A state-of-the-art review. Polic. Int. J. Police Strateg. Manag. 2017, 40, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, P.; Tiesman, H.M.; Wong, I.S.; Bernzweig, D.; James, L.; James, S.M.; Navarro, K.M.; Patterson, P.D. Working hours, sleep, and fatigue in the public safety sector: A scoping review of the research. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2022, 65, 878–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, S.; Roberts, L.; Willis, E.; Couzner, L.; Mohammadi, L.; Goble, E. The effects of emergency medical service work on the psychological, physical, and social well-being of ambulance personnel: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angehrn, A.; Fletcher, A.J.; Carleton, R.N. “Suck it up, buttercup”: Understanding and overcoming gender disparities in policing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilias, M.; Riach, K.; Demou, E. Understanding the interplay between organisational injustice and the health and wellbeing of female police officers: A meta-ethnography. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimerling, R.; Street, A.E.; Pavao, J.; Smith, M.W.; Cronkite, R.C.; Holmes, T.H.; Frayne, S.M. Military-related sexual trauma among Veterans Health Administration patients returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1409–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. Br. Med. J. 1950, 1, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, S.L.; Roberts, S.; Warmington, S.; Drain, J.; Main, L.C. Monitoring stress and allostatic load in first responders and tactical operators using heart rate variability: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szivak, T.K.; Lee, E.C.; Saenz, C.; Flanagan, S.D.; Focht, B.C.; Volek, J.S.; Maresh, C.M.; Kraemer, W.J. Adrenal stress and physical performance during military survival training. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 2018, 89, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Workman, J.L.; Lee, T.T.; Innala, L.; Viau, V. Sex differences in the HPA axis. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 1121–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conkright, W.R.; Beckner, M.E.; Sinnott, A.M.; Eagle, S.R.; Martin, B.J.; Lagoy, A.D.; Proessl, F.; Lovalekar, M.; Doyle, T.L.A.; Agostinelli, P.; et al. Neuromuscular performance and hormonal responses to military operational stress in men and women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, J.R.; Martin, B.J.; Rarick, K.R.; Alemany, J.A.; Staab, J.S.; Kraemer, W.J.; Hymer, W.C.; Nindl, B.C. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I molecular weight isoform responses to resistance exercise are sex-dependent. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, D.E.; McAllister, M.J.; Waldman, H.S.; Ferrando, A.A.; Joyce, J.M.; Barringer, N.D.; Dawes, J.J.; Kieffer, A.J.; Harvey, T.; Kerksick, C.M.; et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Tactical athlete nutrition. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2022, 19, 267–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, B.N.; Volek, J.S.; Kraemer, W.J.; Saenz, C.; Maresh, C.M. Sex differences in energy metabolism: A female-oriented discussion. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 2033–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.; et al. CONSORT 2025 statement: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. Br. Med. J. 2015, 388, e081123. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, L.K.; Out, D.; Hammermeister, J.J.; Ohlson, C.J.; Pickering, M.A.; Granger, D.A. Nature, correlates, and consequences of stress-related biological reactivity and regulation in Army nurses during combat casualty simulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Mandic, I.; Desilets, E.; Smith, I.; Sullivan-Kwantes, W.; Jones, P.J.; Goodman, L.; Jacobs, I.; L’Abbé, M. Energy balance of Canadian Armed Forces personnel during an arctic-like field training exercise. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, A.M.; Kantor, M.A. Oxidative stress increases in overweight individuals following an exercise test. Mil. Med. 2010, 175, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Beckner, M.E.; Thompson, L.; Radcliffe, P.N.; Cherian, R.; Wilson, M.; Barringer, N.; Margolis, L.M.; Karl, J.P. Sex differences in body composition and serum metabolome responses to sustained, physical training suggest enhanced fat oxidation in women compared with men. Physiol. Genom. 2023, 55, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, L.E.; Burchfiel, C.M.; Violanti, J.M.; Fekedulegn, D.; Slaven, J.E.; Browne, R.W.; Hartley, T.A.; Andrew, M.E. Adiposity measures and oxidative stress among police officers. Obesity 2008, 16, 2489–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, G.J.; Han, S.W.; Shin, J.-H.; Kim, T. Effects of intensive trainng on menstrual function and certain serum hormones and peptides related to the female reproductive system. Medicine 2017, 96, e6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coge, M.; Neiva, H.P.; Pereira, A.; Faíl, L.; Ribeiro, B.; Esteves, D. Effects of 34 weeks of military service on body composition and physical fitness in military cadets of Angola. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conkright, W.R.; Beckner, M.E.; Sahu, A.; Mi, Q.; Clemens, Z.J.; Lovalekar, M.; Flanagan, S.D.; Martin, B.J.; Ferrarelli, F.; Ambrosio, F.; et al. Men and women display dinstinct extracellular vesicle biomarker signatures in response to military operational stress. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 132, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, J.S.; Sol, J.A.; Hailes, W.S.; Ruby, B.C. Work patterns dictate energy demands and thermal strain during wildland firefighting. Wild Environ. Med. 2015, 26, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J.J.; dos Santos, M.L.; Kornhauser, C.; Holmes, R.J.; Alvar, B.A.; Lockie, R.G.; Orr, R.M. Longitudinal changes in health and fitness measures among state patrol officers by sex. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, N.D.; Shoemaker, M.E.; DeShaw, K.J.; Carper, M.J.; Hackney, K.J.; Barry, A.M. Contributions from incumbent police officer’s physical activity and body composition to occupational assessment performance. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1217187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.K.; Antczak, A.J.; Lester, M.; Yanovich, R.; Israeli, E.; Moran, D.S. Effects of a 4-month recruit training program on markers of bone metabolism. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, S660–S670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegr, J.; Hampl, R.; Černochová, D.; Preiss, M.; Bičíková, M.; Sieger, L.; Příplatová, L.; Kaňková, Š.; Klose, J. The relation of cortisol and sex hormone levels to results of psychological, performance, IQ and memory tests in military men and women. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2012, 33, 224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R.M.; O’Leary, T.J.; Double, R.L.; Wardle, S.L.; Wilson, K.; Boyle, L.D.; Homer, N.Z.M.; Kirschbaum, C.; Greeves, J.P.; Woods, D.; et al. Positive adaptation of HPA axis function in women during 44 weeks of infantry-based military training. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 110, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R.M.; O’Leary, T.J.; Wardle, S.L.; Double, R.L.; Homer, N.Z.M.; Howie, A.F.; Greeves, J.P.; Anderson, R.A.; Woods, D.; Reynolds, R.M. Reproductive and metabolic adaptation to multistressor training in women. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 321, E281–E291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R.M.; O’Leary, T.J.; Knight, R.L.; Wardle, S.L.; Doig, C.L.; Anderson, R.A.; Greeves, J.P.; Reynolds, R.M.; Woods, D. Sex-related hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis adaptation during military training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 138, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, J.A.; Heye, K.R.; McGlynn, A.; Johansson, S.; Vaccaro, C.M. Association of pelvic floor disorders, perceived psychological stress, and military service in U.S. Navy servicewomen: A cross-sectional survey. Urogynecology 2023, 29, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, A.M.; Theodorsson, E.; Broström, A.; Wagman, P.; Fransson, E.I. Work-related factors and hair cortisol concentrations among men and women in emergency medical services in Sweden. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargl, C.K.; Gage, C.R.; Forse, J.N.; Koltun, K.J.; Bird, M.B.; Lovalekar, M.; Martin, B.J.; Nindl, B.C. Inflammatory and oxidant responses to arduous military training: Associations with stress, sleep, and performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2024, 56, 2315–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugly, S.; Bjärsholm, D.; Jansson, A.; Hansen, A.R.; Hansson, O.; Brehm, K.; Datmo, A.; Östenberg, A.H.; Vikman, J. A retrospective study of physical fitness and mental health among police students in Sweden. Police J. Theory Pract. Princ. 2023, 96, 430–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.R.; Kellogg, M.D.; Bathalon, G.P. Female Marine recruit training: Mood, body composition, and biochemical changes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, S671–S676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.R.; Kellog, M.D.; Kramer, F.M.; Bathalon, G.P. Lipid and other plasma markers are associated with anxiety, depression, and fatigue. Health Psychol. 2012, 31, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClung, J.P.; Karl, J.P.; Cable, S.J.; Williams, K.W.; Nindl, B.C.; Young, A.J.; Lieberman, H.R. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of iron supplementation in female soldiers during military training: Effects on iron status, physical performance, and mood. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, B.A.; Cintineo, H.P.; Chandler, A.J.; Mastrofini, G.F.; Vincenty, C.S.; Peterson, P.; Lovalekar, M.; Nindl, B.C.; Arent, S.M. A sex comparison of the physical and physiological demands of United States Marine Corps recruit training. Mil. Med. 2024, 189, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, B.A.; Cintineo, H.P.; Chandler, A.J.; Peterson, P.; Lovalekar, M.; Nindl, B.C.; Arent, S.M. United States Marine Corps recruit training demands associated with performance outcomes. Mil. Med. 2024, 189, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nindl, B.C.; Scofield, D.E.; Strohbach, C.A.; Centi, A.J.; Evans, R.K.; Yanovich, R.; Moran, D.S. IGF-I, IGFBPs, and inflammatory cytokine responses during gender-integrated Israeli Army basic combat training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, S73–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øfsteng, S.J.; Garthe, I.; Jøsok, Ø.; Knox, S.; Helkala, K.; Knox, B.; Ellefsen, S.; Rønnestad, B.R. No effect of increasing protein intake during military exercise with severe energy deficit on body composition and performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, T.J.; Saunders, S.C.; McGuire, S.J.; Izard, R.M. Sex differences in neuromuscular fatigability in response to load carriage in British Army recruits. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2018, 21, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, T.J.; Coombs, C.V.; Edwards, V.C.; Blacker, S.D.; Knight, R.L.; Koivula, F.N.; Tang, J.C.Y.; Fraser, W.D.; Wardle, S.L.; Greeves, J.P. The effect of sex and protein supplementation on bone metabolism during 36-h military field exercise in energy deficit. J. Appl. Physiol. 2023, 134, 1481–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, T.J.; Gifford, R.M.; Knight, R.L.; Wright, J.; Handford, S.; Venables, M.C.; Reynolds, R.M.; Woods, D.; Wardle, S.L.; Greeves, J.P. Sex differences in energy balance, body composition, and metabolic and endocrine markers during prolonged arduous military training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2024, 136, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, T.J.; Evans, H.A.; Close, M.-E.O.; Izard, R.M.; Walsh, N.P.; Coombs, C.V.; Carswell, A.T.; Oliver, S.J.; Tang, J.C.Y.; Fraser, W.D.; et al. Hormonal contraceptive use and physical performance, body composition, and musculoskeletal injuries during military training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2025, 57, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasiakos, S.M.; Karl, J.P.; Lutz, L.J.; Murphy, N.E.; Margolis, L.M.; Rood, J.C.; Williams, K.W.; Young, A.J.; McClung, J.P. Cardiometabolic risk in US Army recruits and the effects of basic combat training. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, L.M.; Pasiakos, S.M.; Karl, J.P.; Rood, J.C.; Cable, S.J.; Williams, K.W.; Young, A.J.; McClung, J.P. Differential effects of military training on fat-free mass and plasma amino acid adaptations in men and women. Nutrients 2012, 4, 2035–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, K.L.; Bozzini, B.N.; Reynoso, M.; Coulombe, J.; Guerriere, K.I.; Proctor, S.P.; Castellani, C.M.; Walker, L.A.; Zurinaga, N.; Kuhn, K.; et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis suppression is common among women during US Army Basic Combat Training. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahler, J.; Ziegert, T. Psychobiological stress response to a simulated school shooting in police officers. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 51, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szivak, T.K.; Thomas, M.M.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Nguyen, D.R.; Ryan, D.M.; Mazure, C.M. Obesity risk among West Point graduates later in life. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 1284–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomei, G.; Ciarrocca, M.; Fiore, P.; Rosati, M.V.; Pimpinella, B.; Anzani, M.F.; Giubilati, R.; Cangemi, C.; Tomao, E.; Tomei, F. Exposure to urban stressor and effects on free testosterone in female workers. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 392, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vikmoen, O.; Teien, H.K.; Raustøl, M.; Aandstad, A.; Tansø, R.; Gulliksrud, K.; Skare, M.; Raastad, T. Sex differences in the physiological response to a demanding military field exercise. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 1348–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, G.; Lenart, D.; Lachowicz, M.; Zebrowski, K.; Jamro, D. Factors influencing the executive functions of male and female cadets. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdella-Kam, L.; Bloedon, T.K.; Stone, M.S. Body composition as a marker of performance and health in military personnel. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1223254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, C.; Hooper, S.; Orange, T.; Knight, A.; Barragan, M.; Lynch, T.; Remenapp, A.; Coyle, K.; Winters, C.; Hausenblas, H. Effect of a free-living ketogenic diet on feasibility, satiety, body composition, and metabolic health in women: The grading level of optimal carbohydrate for women (GLOW) study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2021, 40, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harty, P.S.; Friedl, K.E.; Nindl, B.C.; Harry, J.R.; Vellers, H.L.; Tinsley, G.M. Military body composition standards and physical performance: Historical perspectives and future directions. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 3551–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinson, R.J.; Williams, N.I.; Hill, B.R.; De Souza, M.J. Body composition and reproductive function exert unique influences on indices of bone health in exercising women. Bone 2013, 56, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C.L.; Giersch, G.E.W.; Gwin, J.A.; Goldenstein, S.; Schafer, E.A.; Roberts, B.M.; Potter, A.W. Body composition and physical readiness in military servicemembers: Cross-disciplinary advances and current challenges. Exerc. Sport. Mov. 2025, 3, e00050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, T.J.; Wardle, S.L.; Greeves, J.P. Energy deficiency in soldiers: The risk of the Athlete Triad and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport syndromes in the military. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabre, H.E.; Moore, S.R.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Hackney, A.C. Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Scientific, clinical, and practical implications for the female athlete. Dtsch. Z. Sportmed. 2022, 73, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popp, K.L.; Cooke, L.M.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Hughes, J.M. Impact of low energy availability on skeletal health in physically active adults. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2022, 110, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, T.J.; Perrett, C.; Coombs, C.V.; Double, R.L.; Keay, N.; Wardle, S.L.; Greeves, J.P. Menstrual disturbances in British Servicewomen: A cross-sectional observational study of prevalence and risk factors. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 984541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Burke, L.; Carter, S.; Constantini, N.; Lebrun, C.; Meyer, N.; Sherman, R.; Steffen, K.; Budgett, R.; et al. The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the Female Athlete Triad--Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Heikura, I.A.; Hackney, A.C.; Stellingwerff, T. Mapping the complexities of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs): Development of a physiological model by a subgroup of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Consensus on REDs. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.R.; Mallard, J.; Wight, J.T.; Conway, K.L.; Pujalte, G.G.A.; Pontius, K.M.; Saenz, C.; Hackney, A.C.; Tenforde, A.S.; Ackerman, K.E. Performance and health decrements associated with Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport for Division I women athletes during a collegiate cross-country season: A case series. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 524762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, C.; Jordan, A.; Loriz, L.; Schill, K.; Colletto, M.; Rodriguez, J. Low energy intake leads to body composition and performance decrements in a highly-trained, female athlete: The WANDER (Woman’s Activity and Nutrition during an Extensive Hiking Route) case study. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2023, 43, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chee, J.; Tanaka, M.J.; Lee, Y.H.D. Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) and knee injuries: Current concepts for female athletes. J. Isakos 2024, 9, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saenz, C.; Sanders, D.J.; Brooks, S.J.; Bracken, L.; Jordan, A.; Stoner, J.; Vatne, E.; Wahler, M.; Brown, A.F. The relationship between dance training volume, body composition, and habitual diet in female collegiate dancers: The Intercollegiate Artistic Athlete Research Assessment (TIAARA) study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Chang, C.-C.; Lin, M.-P.; Lin, C.-C.; Chen, P.-Y.; Juan, C.-H. Chapter three-Association between physical activity, body composition, and cognitive performance among female office workers. Prog. Brain Res. 2024, 286, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cataldi, D.; Bennett, J.P.; Wong, M.C.; Quon, B.K.; Liu, Y.E.; Kelly, N.N.; Kelly, T.; Schoeller, D.A.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Shepherd, J.A. Accuracy and precision of multiple body composition methods and associations with muscle strength in athletes of varying hydration: The Da Kine study. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, B.S.; Esco, M.R.; Bishop, P.A.; Kliszczewicz, B.M.; Williford, H.N.; Park, K.-S.; Welborn, B.A.; Snarr, R.L.; Tolusso, D.V. Effects of heat exposure on body water assessed using single-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis and bioimpedance spectroscopy. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2017, 10, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Mock, M.G.; Ryan, E.D.; Gerstner, G.R.; Trexler, E.T.; Hirsch, K.R. Validity and reliability of a 4-compartment body composition model using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry-derived blood volume. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nindl, B.C. Physical training strategies for military women’s performance optimization in combat-centric occupations. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, S101–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterczala, A.J.; Krajewski, K.T.; Peterson, P.A.; Sekel, N.M.; Lovalekar, M.; Wardle, S.L.; O’Leary, T.J.; Greeves, J.P.; Flanagan, S.D.; Connaboy, C.; et al. Twelve weeks of concurrent resistance and interval training improves military occupational task performance in men and women. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2023, 23, 2411–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, K.L.; Taim, B.C.; Freemas, J.A.; Hassan, A.; Brantner, C.L.; Oleka, C.T.; Scott, D.; Howatson, G.; Moore, I.S.; Yung, K.K.; et al. Research across the female life cycle: Reframing the narrative for health and performance in athletic females and showcasing solutions to drive advancements in research and translation. Women Sport. Phys. Act. J. 2024, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.M.; Reynolds, R.M.; Greeves, J.P.; Anderson, R.A.; Woods, D.R. Reproductive dysfunction and associated pathology in women undergoing military training. J. R. Army Med. Corps 2017, 163, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szivak, T.K.; Mala, J.; Kraemer, W.J. Physical performance and integration strategies for women in combat arms. Strength Cond J. 2015, 37, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Szivak, T.K. Strength training for the warfighter. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, S107–S118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conkright, W.R.; O’Leary, T.J.; Wardle, S.L.; Greeves, J.P.; Beckner, M.E.; Nindl, B.C. Sex differences in the physical performance, physiological, and psycho-cognitive responses to military operational stress. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2022, 22, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giersch, G.E.W.; Charkoudian, N.; McClung, H.L. The rise of the female warfighter: Physiology, performance, and future directions. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartman, N.E.; Hess, H.W.; Colburn, D.; Temple, J.; Hostler, D. Heat strain in different hot environments hiking in wildland firefighting garments. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryman, C.E.; McClung, H.L.; Sepowitz, J.J.; Gaffney-Stomberg, E.; Ferrando, A.A.; McClung, J.P.; Pasiakos, S.M. Testosterone status following short-term, severe energy deficit is associated with fat-free mass loss in U.S. Marines. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.M.; Tang, X.; Dreer, L.E.; Driver, S.; Pugh, M.J.; Martin, A.M.; McKenzie-Hartman, T.; Shea, T.; Silva, M.A.; Nakase-Richardson, R. Change in body mass index within the first-year post-injury: A VA Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) model systems study. Brain Inj. 2018, 32, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulmer, S.; Aisbett, B.; Drain, J.R.; Roberts, S.; Gastin, P.B.; Tait, J.; Main, L.C. Sleep of recruits throughout basic military training and its relationships with stress, recovery, and fatigue. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitra, T.; Karunanidhi, S. The Impact of Resilience Training on Occupational Stress, Resilience, Job Satisfaction, and Psychological Well-being of Female Police Officers. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2021, 36, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Schnall, P.; Dobson, M. Twenty-four-hour work shifts, increased job demands, and elevated blood pressure in professional firefighters. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 1111–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christison, K.S.; Gurney, S.C.; Sol, J.A.; Williamson-Reisdorph, C.M.; Quindry, T.S.; Quindry, J.C.; Dumke, C.L. Muscle Damage and Overreaching During Wildland Firefighter Critical Training. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christison, K.S.; Sol, J.A.; Gurney, S.C.; Dumke, C.L. Wildland Firefighter Critical Training Elicits Positive Adaptations to Markers of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Health. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2023, 34, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, A.; Christophi, C.A.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Moffatt, S.; Kales, S.N. Eating Habits among US Firefighters and Association with Cardiometabolic Outcomes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, R.H.; Murphy, C.J.; Johannsen, M.; Galvin, G.; Ruby, B.C. Wildland Firefighting. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, e91–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, C.V.; Wardle, S.L.; Shroff, R.; Eisenhauer, A.; Tang, J.C.Y.; Fraser, W.D.; Greeves, J.P.; O’Leary, T.J. The effect of calcium supplementation on calcium and bone metabolism during load carriage in women: Protocol for a randomised controlled crossover trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, J.; Wright, J.; Tipton, M.J. Sex differences in response to exercise heat stress in the context of the military environment. BMJ Mil. Health 2020, 169, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nota, P.M.; Scott, S.C.; Huhta, J.-M.; Gustafsberg, H.; Andersen, J.P. Physiological Responses to Organizational Stressors Among Police Managers. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2024, 49, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Manzano, M.; Fuentes, J.P.; Fernandez-Lucas, J.; Aznar-Lain, S.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Higher use of techniques studied and performance in melee combat produce a higher psychophysiological stress response. Stress Health 2018, 34, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drain, J.R.; Groeller, H.; Burley, S.D.; Nindl, B.C. Hormonal response patterns are differentially influenced by physical conditioning programs during basic military training. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, S98–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Y.; Yanovich, R.; Moran, D.S.; Heled, Y. Physiological employment standards IV: Integration of women in combat units physiological and medical considerations. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 113, 2673–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagnant, H.S.; Armstrong, N.J.; Lutz, L.J.; Nakayama, A.T.; Guerriere, K.I.; Ruthazer, R.; Cole, R.E.; McClung, J.P.; Gaffney-Stomberg, E.; Karl, J.P. Self-reported eating behaviors of military recruits are associated with body mass index at military accession and change during initial military training. Appetite 2019, 142, 104348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, E.K.; Taylor, J.C.; Means, G.E.; Murphy, N.E.; Pasiakos, S.M.; Lieberman, H.R.; McClung, J.P. Effects of deployment on diet quality and nutritional status markers of elite U.S. Army special operations forces soldiers. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, E.K.; Stein, J.A.; Thompson, L.A.; Knapik, J.J.; Pasiakos, S.M.; McClung, J.P.; Lieberman, H.R. Longitudinal changes in psychological, physiological, and nutritional measures and predictors of success in Special Forces training. Physiol. Behav. 2025, 291, 114790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flood, A.; Keegan, R.J. Cognitive Resilience to Psychological Stress in Military Personnel. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 809003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forse, J.N.; Koltun, K.J.; Bird, M.B.; Lovalekar, M.; Feigel, E.D.; Steele, E.J.; Martin, B.J.; Nindl, B.C. Low psychological resilience and physical fitness predict attrition from US Marine Corps Officer Candidate School training. Mil. Psychol. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, K.E. Biomedical Research on Health and Performance of Military Women: Accomplishments of the Defense Women’s Health Research Program (DWHRP). J. Women’s Health 2005, 14, 764–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney-Stomberg, E.; Lutz, L.J.; Rood, J.C.; Cable, S.J.; Pasiakos, S.M.; Young, A.J.; McClung, J.P. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation maintains parathyroid hormone and improves bone density during initial military training: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Bone 2014, 68, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnacinski, S.L.; Ebersole, K.T.; Cornell, D.J.; Mims, J.; Zamzow, A.; Meyer, B.B. Firefighters’ cardiovascular health and fitness: An observation of adaptations that occur during firefighter training academies. Work 2016, 54, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.K.M.; Charles, L.E.; Burchfiel, C.M.; Fekedulegn, D.; Sarkisian, K.; Andrew, M.E.; Ma, C.; Violanti, J.M. Long Work Hours and Adiposity Among Police Officers in a US Northeast City. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 54, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, J.; Blodgett, K.; Stedman, J.; Pojednic, R. Dietary Supplementation on Physical Performance and Recovery in Active-Duty Military Personnel: A Systematic Review of Randomized and Quasi-Experimental Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heblich, F.; Kähler, W. Increased stress for firefighters due to wearing full-face masks? Zentralblatt Arb. 2020, 70, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hormeño-Holgado, A.J.; Perez-Martinez, M.A.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Psychophysiological response of air mobile protection teams in an air accident manoeuvre. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 199, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourani, L.L.; Williams, T.V.; Kress, A.M. Stress, Mental Health, and Job Performance among Active Duty Military Personnel: Findings from the 2002 Department of Defense Health-Related Behaviors Survey. Mil. Med. 2006, 171, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ibrahim, F.; Schumacher, J.; Schwandt, L.; Herzberg, P.Y. The first shot counts the most: Tactical breathing as an intervention to increase marksmanship accuracy in student officers. Mil. Psychol. 2023, 36, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, J.M.; Ayala, R.; Karl, J.P.; Deschamps, B.A.; McGraw, S.M.; O’Connor, K.; DiChiara, A.J.; Cole, R.E. Body weight status, perceived stress, and emotional eating among US Army Soldiers: A mediator model. Eat. Behav. 2020, 36, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, J.M.; Blake, C.E.; Frongillo, E.A.; Liese, A.D.; Cai, B.; Nelson, D.A.; Kurina, L.M.; Funderburk, L. Stressful Life Changes and Their Relationship to Nutrition-Related Health Outcomes Among US Army Soldiers. J. Prev. 2020, 41, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korre, M.; Loh, K.; Eshleman, E.J.; Lessa, F.S.; Porto, L.G.; Christophi, C.A.; Kales, S.N. Recruit fitness and police academy performance: A prospective validation study. Occup. Med. 2019, 69, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukić, F.; Koropanovski, N.; Jankovic, R.; Cvorovic, A.; Dawes, J.J.; Lockie, G.R.; Orr, R.M.; Dopsaj, M. Association of Sex-Related Differences in Body Composition to Change of Direction Speed in Police Officers While Carrying Load. Int. J. Morphol. 2020, 38, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukić, F.; Streetman, A.; Heinrich, K.M.; Popović-Mančević, M.; Koropanovski, N. Association between police officers’ stress and perceived health. Polic. A J. Policy Pract. 2023, 17, paad058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, F.-Y.; Yiannakou, I.; Scheibler, C.; Hershey, M.S.; Cabrera, J.L.R.; Gaviola, G.C.; Fernandez-Montero, A.; Christophi, C.A.; Christiani, D.C.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; et al. The Effects of Fire Academy Training and Probationary Firefighter Status on Select Basic Health and Fitness Measurements. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.R.; Thompson, L.A.; Caruso, C.M.; Niro, P.J.; Mahoney, C.R.; McClung, J.P.; Caron, G.R. The catecholamine neurotransmitter precursor tyrosine increases anger during exposure to severe psychological stress. Psychopharmacology 2015, 232, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.-H.; Su, F.-Y.; Yang, S.-N.; Liu, M.-W.; Kao, C.-C.; Nagamine, M.; Lin, G.-M. Body Mass Index and Association of Psychological Stress with Exercise Performance in Military Members: The Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Hospitalization Events in Armed Forces (CHIEF) Study. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord.-Drug Targets 2021, 21, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, M.J.; Martaindale, M.H.; Rentería, L.I. Active Shooter Training Drill Increases Blood and Salivary Markers of Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, M.J.; Martaindale, M.H. Women demonstrate lower markers of stress and oxidative stress during active shooter training drill. Compr. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 6, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClung, J.P.; Karl, J.P.; Cable, S.J.; Williams, K.W.; Young, A.J.; Lieberman, H.R. Longitudinal decrements in iron status during military training in female soldiers. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.L.; Wooldridge, J.S.; Herbert, M.S.; Afari, N. The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior Engagement and Psychological and Physical Health Among Active Duty Military Enrolled in a Weight Management Intervention: An Exploratory Study. Mil. Med. 2024, 189, e1840–e1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojanen, T.; Häkkinen, K.; Hanhikoski, J.; Kyröläinen, H. Effects of Task-Specific and Strength Training on Simulated Military Task Performance in Soldiers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penatzer, J.A.; Miller, J.V.; Han, A.A.; Prince, N.; Boyd, J.W. Salivary cytokines as a biomarker of social stress in a mock rescue mission. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2020, 4, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda Calderón, C.F.; Monteros Luzuriaga, G.S.; Yepez Herrera, E.R.; Guerron Varela, E.R. Physical conditioning and its relationship with stress in the National Police of the Metropolitan District of Quito. Retos 2023, 48, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proessl, F.; Canino, M.C.; Beckner, M.E.; Conkright, W.R.; LaGoy, A.D.; Sinnott, A.M.; Eagle, S.R.; Martin, B.J.; Sterczala, A.J.; Roma, P.G.; et al. Use-dependent corticospinal excitability is associated with resilience and physical performance during simulated military operational stress. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 132, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, S.L.; Downing, N.R.; Franke, W.D.; Perkhounkova, Y.; Alasagheirin, M.H. Relationships Among Stress Measures, Risk Factors, and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Law Enforcement Officers. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2011, 14, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodas, K.A.; Dulla, J.M.; Moreno, M.R.; Bloodgood, A.M.; Thompson, M.B.; Orr, R.M.; Dawes, J.J.; Lockie, R.G. The Effects of Traditional versus Ability-Based Physical Training on the Health and Fitness of Custody Assistant Recruits. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2022, 15, 1641–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalky, D.S.; Hostler, D.; Webb, H.E. Work duration does not affect cortisol output in experienced firefighters performing live burn drills. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 58, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, R.; Colledge, F.; Ludyga, S.; Pühse, U.; Brand, S.; Gerber, M. Does Cardiorespiratory Fitness Moderate the Association between Occupational Stress, Cardiovascular Risk, and Mental Health in Police Officers? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, R.; Herrmann, C.; Ludyga, S.; Colledge, F.; Brand, S.; Pühse, U.; Gerber, M. Does Cardiorespiratory Fitness Buffer Stress Reactivity and Stress Recovery in Police Officers? A Real-Life Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, R.; Colledge, F.; Pühse, U.; Gerber, M.; Vandoni, M. Stress-buffering effects of physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness on metabolic syndrome: A prospective study in police officers. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.M.; Kazman, J.B.; Palmer, J.; McClung, J.P.; Gaffney-Stomberg, E.; Gasier, H.G. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on salivary immune responses during Marine Corps basic training. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, J.L.; Drain, J.R.; Corrigan, S.L.; Drake, J.M.; Main, L.C.; Lomonaco, T. Impact of military training stress on hormone response and recovery. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.K.; Stone, M.; Laurent, H.K.; Rauh, M.J.; Granger, D.A. Neuroprotective–neurotrophic effect of endogenous dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate during intense stress exposure. Steroids 2014, 87, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegeler, C.L.; Gerdes, L.; Shaltout, H.A.; Cook, J.F.; Simpson, S.L.; Lee, S.W.; Tegeler, C.H. Successful use of closed-loop allostatic neurotechnology for post-traumatic stress symptoms in military personnel: Self-reported and autonomic improvements. Mil. Med. Res. 2017, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingestad, H.C.; Filion, L.G.; Martin, J.; Spivock, M.; Tang, V.; Haman, F. Stress and immune mediators in the Canadian Armed Forces: Association between basal levels and military physical performance. J. Mil. Veterans Health 2019, 27, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Toczko, M.; Fyock-Martin, M.; McCrory, S.; Martin, J. Effects of fitness on self-reported physical and mental quality of life in professional firefighters: An exploratory study. Work 2023, 76, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente-Rodríguez, M.; Fuentes-Garcia, J.P.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Psychophysiological Stress Response in an Underwater Evacuation Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, L.M.; Palombo, L.J.; Givens, A.C.; Turcotte, L.P.; Kelly, K.R. Stress Response to Winter Warfare Training: Potential Impact of Location. Mil. Med. 2024, 189, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, E.R.; Hayes, M.; Watt, P.; Richardson, A.J. Heat tolerance of Fire Service Instructors. J. Therm. Biol. 2019, 82, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (k = 40) N = 3693 | Military (k = 32) n = 2702 | Police (k = 6) n = 864 | EMS (k = 1) n = 28 | Fire (k = 1) n = 3 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | M | SD | Min, Max | k | M | SD | Min, Max | k | M | SD | Min, Max | k | M | SD | Min, Max | k | M | SD | Min, Max | |

| Age (y) | 38 | 26.9 | 7.5 | 18.8, 47.6 | 30 | 24.4 | 5.4 | 18.8, 44.1 | 6 | 35.6 | 4.4 | 27.5, 39.6 | 1 | 47.6 | 9.4 | - | 1 | 26 | 3 | - |

| Recruits/ Cadets, n (%) | 28 | 3228 | 87.4% | 24 | 1917 | 70.9% | 1 | 682 | 78.9% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | |||||

| Servicewomen, n (%) | 12 | 953 | 25.8% | 3 | 673 | 24.9% | 4 | 249 | 28.8% | 1 | 28 | 100% | 1 | 3 | 100% | |||||

| Service (y) | 6 | 8.2 | 4.1 | 3.0, 14.1 | 2 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 3.0, 3.3 | 4 | 9.8 | 2.4 | 7.4, 13.1 | 1 | 14.1 | 8.2 | - | 1 | 6 | 2 | - |

| Body mass (kg) | 31 | 67.1 | 5.6 | 60.9, 82.3 | 33 | 66.8 | 5.6 | 60.9, 82.3 | 3 | 72.2 | 6.2 | 67.8, 76.5 | - | 1 | 66.7 | 4.4 | - | |||

| BF (%) | 14 | 28.3 | 4.9 | 17.2, 36.0 | 13 | 27.9 | 4.8 | 17.2, 36.0 | 1 | 33.7 | - | - | - | |||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26 | 25.1 | 2.1 | 22.4, 30.2 | 25 | 25.1 | 2.1 | 22.4, 30.2 | 6 | 25.4 | 2.2 | 23.0, 28.0 | - | 1 | 24.3 | 1.7 | - | |||

| WC (cm) | 2 | 76.0 | 6.3 | 71.5, 80.4 | 1 | 71.5 | - | 1 | 80.4 | - | - | - | ||||||||

| VO2max (mL/kg/min) | 9 | 36.0 | 4.3 | 27.2, 40.5 | 6 | 36.5 | 7.0 | 32.5, 40.5 | 3 | 35.2 | 7.0 | 27.2, 40.4 | - | - | ||||||

| Author, Year | Tactical Domain and Study Characteristics | Sample Characteristics | Adrenal and Neuroendocrine Responses | Other Markers Analyzed | Impact of Stress and Sex on Adrenal and Neuroendocrine Responses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes and Assessment Details | Aggregate-Level Study Data (Mean ± SD) a | |||||

| Andrews et al., 2010 † [33] RQ: 51.6% | Military Design: Cross-sectional; service members completing the Army Physical Fitness Test (Washington, DC, USA) Primary outcomes: Oxidative stress |

| Oxidative stress biomarkers: Creatine kinase, C-reactive protein, glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase Methods: Serum (Creatine kinase and C-reactive protein) and plasma (glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase) Fasted status: NR | Creatine kinase, U/L (F): Pre (n = 18): 117.0 ± 57.3 Post (n = 17): 153.9 ± 63.5 Post 24 h (n = 7): 169.0 ± 70.2 * C-reactive protein, mg/dL (F): Pre (n = 17): 0.29 ± 0.28 Post (n = 14): 0.29 ± 0.23 Post 24 h (n = 7): 0.34 ± 0.27 Glutathione peroxidase, ng/dL (F): Pre (n = 17): 76.2 ± 42.0 Post (n = 17): 70.8 ± 29.3 Superoxide dismutase, ng/dL (F): Pre (n = 16): 0.80 ± 0.62 Post (n = 16): 0.95 ± 0.63 * p < 0.05 (time) | Baseline: Body composition, fitness level, dietary intake |

|

| Cho et al., 2017 [36] RQ: 42.4% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (8 wk); during 16-wk Officer training course at the Korea Third Military Academy (Yeongcheon, South Korea) Primary outcomes: Reproductive function |

| Hormones: Cortisol, CRH, estradiol Methods: Serum Fasted status: Overnight | Cortisol, μg/dL: Baseline: 16.1 ± 3.9 Wk 4: 18.1 ± 2.2 Wk 8: 18.7 ± 2.2 * CRH, pg/dL: Baseline: 84.4 ± 65.1 Wk 4: 57.7 ± 28.3 Wk 8: 22.0 ± 21.7 * Estradiol, pg/dL: Baseline: 106.0 ± 120.7 Wk 4: 44.6 ± 24.4 Wk 8: 55.1 ± 43.1 * * p < 0.01 (time) | Reproductive function: regularity, prolactin, endorphin-β, NPY, leptin, orexin-A, ghrelin, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroxine |

|

| Conkright et al., 2021 ‡ [24] RQ: 57.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort; 5-day simulated military operational stress protocol (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) Primary outcomes: Neuromuscular performance, mood state, and hormonal responses |

| Hormones: Cortisol, IGF-1 Methods: Serum (PRE and POST tactical mobility test) Fasted status: Overnight | Cortisol, μg/dL (PRE) (F): Day 1: 14.4 ± 3.8 Day 3: 12.6 ± 4.7 Day 4: 12.7 ± 4.3 Cortisol, μg/dL (POST) (F): Day 1: 23.5 ± 5.7 * Day 3: 26.8 ± 6.5 * Day 4: 25.1 ± 9.2 * IGF-1, ng/mL (PRE) (F): Day 1: 409.3 ± 118.9 Day 3: 353.1 ± 93.3 Day 4: 321.7 ± 95.8 IGF-1, ng/mL (POST) (F): Day 1: 397.7 ± 93.3 Day 3: 360.6 ± 108.1 * Day 4: 335.8 ± 98.2 *,** * p < 0.05 (time, POST vs. PRE), ** p < 0.05 (day) | Neuromuscular performance: Lower body power, tactical mobility test Mood state: POMS subscales (tension, depression, anger, fatigue, confusion, vigor) Other hormones: Growth hormone, brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

|

| Flegr et al., 2012 [43] RQ: 43.8% | Military Design: Cross-sectional; psychological performance battery as part of entrance examination (Central Military Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic) Primary outcomes: Psychological health and performance, hormones |

| Hormones: Cortisol, testosterone, estradiol Methods: Serum Fasted status: NR | Cortisol, nmol/L (F): 728 ± 121 * Testosterone, nmol/L (F): 1.10 ± 3.87 * Estradiol, nmol/L (F): 0.29 ± 0.03 * * p < 0.001 (sex) | Psychological health: Questionnaires (N-70, OD-1, Buss–Dürker Inventory) Psychological performance: Meili selective memory test, TOPP test (attention and short-term memory), Wiener Matrizen-Test, OTIS test (verbal intelligence) |

|

| Gifford et al., 2019 ‡ [44] RQ: 78.8% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (11 months); Commissioning Course (infantry-based training) at the Royal Military Academy (Sandhurst, UK) Primary outcomes: HPA axis function, mental health Part of the Female Endocrinology in Arduous Training (FEAT) Study |

| Hormones: Cortisol Methods: HCC and salivary cortisol (measured AM and PM), plasma cortisol (measured in AM, separated into non-CCP vs. CCP users) Fasted status: Overnight (plasma only) | HCC, pg/mg (ln): Month 1: 2.0 ± 0.9 * Month 2: 2.1 ± 0.8 * Month 3: 2.1 ± 1.0 * Month 4: 2.0 ± 1.1 * Month 5: 2.0 ± 0.9 Month 6: 2.2 ± 0.7 Month 7: 2.2 ± 0.9 Month 8: 2.1 ± 0.9 Month 9: 2.2 ± 0.9 * Month 10: 2.4 ± 0.9 * Month 11: 2.4 ± 0.7 * Month 12: 2.2 ± 0.9 * Cortisol (saliva), μg/dL ** T1: Wk 1 = 0.4 ± 0.3, Wk 7 = 0.6 ± 0.2, Wk 14 = 0.5 ± 0.3 T2: Wk 1 = 0.6 ± 0.3, Wk 5 = 0.5 ± 0.1, Wk 14 = 0.4 ± 0.3 T3: Wk 1 = 0.5 ± 0.2, Wk 5 = 0.5 ± 0.2, Wk 14 = 0.4 ± 0.2 Cortisol (plasma), nmol/L: non-CCP users ** T1: Wk 1 = 701.0 ± 134.6 T2: Wk 14 = 669.3 ± 162.4 T3: Wk 13 = 558.4 ± 182.2 CCP users ** T1: Wk 1 = 1061.4 ± 198.0 T2: Wk 14 = 966.3 ± 166.4 T3 Wk 13 = 855.4 ± 190.1 * p < 0.05 (time, vs. pre-6 to pre-4), ** p < 0.001 (main effect, time) | Mental health: Anxiety, depression, resilience |

|

| Gifford et al., 2025 ‡ [46] RQ: 72.7% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (11 months); Commissioning Course (infantry-based training) at the Royal Military Academy (Sandhurst, UK) Primary outcomes: HPA axis function, HPG axis function Part of the Female Endocrinology in Arduous Training (FEAT) Study |

| Hormones: Cortisol Methods: HCC, saliva, plasma (in response to 1 μL ACTH over 1 h) Fasted status: Overnight (plasma) | Ln-HCC, pg/mg (F): Month 0: 2.1 (0.2) Month 1: 2.3 (0.1) Month 2: 2.1 (0.2) Month 3: 2.0 (0.2) Month 4: 1.8 (0.2) Month 5: 2.1 (0.2) * Month 6: 2.2 (0.1) * Month 7: 2.0 (0.2) * Month 8: 2.2 (0.2) Month 9: 2.3 (0.2) * Month 10: 2.4 (0.2) * Month 11: 2.1 (0.2) * Cortisol, μg/dL—saliva (F): Wk 1: AM = 0.45 (0.06) vs. PM = 0.11 (0.01) Wk 8: AM = 0.62 (0.05) * vs. PM = 0.09 (0.03) Wk 14: AM = 0.55 (0.05) vs. PM = 0.09 (0.02) Wk 16: AM = 0.58 (0.06) vs. PM = 0.09 (0.02) Wk 20: AM = 0.47 (0.04) * vs. PM = 0.11 (0.03) Wk 29: AM = 0.44 (0.05) vs. PM = 0.15 (0.03) Cortisol, nmol/L—plasma (F) * Wk 1 Min 0: 197.0 (24.1) Wk 29 Min 0: 255.6 (53.0) Wk 1 Min 20: 512.1 (27.9) Wk 29 Min 20: 574.1 (23.4) Wk 1 Min 30: 564.2 (35.5) Wk 29 Min 30: 672.2 (25.9) Wk 1 Min 40: 532.4 (35.6) Wk 29 Min 40: 540.7 (18.6) Wk 1 Min 60: 466.3 (30.5) Wk 29 Min 60: 479.0 (18.5) * p < 0.05 (sex × time) | Other hormones: Gonadotrophins (follicle-stimulating hormone, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone, luteinizing hormone) |

|

| Johnsen et al., 2023 [48] RQ: 71.9% | Emergency medical services Design: Cross-sectional Primary outcomes: Physiological and psychosocial stress |

| Hormones: Cortisol Methods: HCC Fasted status: NR | Cortisol, pg/mg (F): 23.5 [IQR: 11.6–47.0] p = 0.719 (sex) | Psychosocial stress: 17-item Demand–Control–Support Questionnaire |

|

| Lieberman et al., 2008 [51] RQ: 66.7% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (13 wk); U.S. Marine Corps basic training (Parris Island, SC, USA) Primary outcomes: Body composition, metabolic status, mood state |

| Hormones: Cortisol Methods: Serum Fasted status: Overnight | Cortisol, μg/dL: Wk 1: 13.2 ± 0.7 Wk 12: 10.4 ± 0.7 p < 0.003 (time) | Body composition: BM, FM, FFM, BF, BMM Metabolic status: Cholesterol (total, LDL, HDL), free fatty acids, glucose Mood state: POMS subscales (fatigue, confusion, depression, tension, anger, vigor) |

|

| Lieberman et al., 2012 [52] RQ: 60.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (12 wk); U.S. Marine Corps basic training (Parris Island, SC, USA) Primary outcomes: Body composition, mood state, metabolic status |

| Hormones: ACTH Methods: Serum Fasted status: Overnight | ACTH, pg/mL: Pre: 16.2 ± 9.7 Post: 15.4 ± 8.0 p = 0.583 (time) | Body composition: BM, FM, LM, BMM Mood state: POMS subscales (fatigue, confusion, depression, tension, anger, vigor) Metabolic status: Substance P, fructosamine, cholesterol (total, HDL, LDL), triglycerides, free fatty acids, DHEA-S |

|

| McFadden et al., 2024a ‡ [54] RQ: 72.7% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (13 wk); U.S. Marine Corps basic training (Parris Island, SC, USA) Primary outcomes: Sex differences in workload, sleep, stress, and performance Part of a larger study, the U.S. Marine Corps Gender-Integrated Recruit Training study |

| Hormones: Cortisol Methods: Saliva Fasted status: NR | Cortisol, μg/dL: Wk 2: 0.78 (0.03) Wk 7/8: 0.63 (0.02) Wk 11: 0.77 (0.07) p = 0.01 (sex × time) | Performance: Lower body strength and power Workload: Relative energy expenditure, distance, steps Sleep: Continuity and duration |

|

| McFadden et al., 2024b [55] RQ: 72.7% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (11 wk); U.S. Marine Corps basic training (Parris Island, SC, USA) Primary outcomes: Performance, resilience, wearable tracking Part of a larger study, the U.S. Marine Corps Gender-Integrated Recruit Training study |

| Hormones: Cortisol Methods: Saliva Fasted status: NR | Cortisol, μg/dL: Wk 2: 0.8 ± 0.4 Wk 7: 0.6 ± 0.3 Wk 11: 0.8 ± 0.7 p-value NR | Performance: U.S. Marine Corps—specific performance, lower body strength, and power Resilience: Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, workload, self-reported sleep, stress Wearable tracking: energy expenditure, distances, sleep, acceleration |

|

| McGraw et al., 2013 † [31] RQ: 64.3% | Military Design: Quasi-experimental (within-subjects, repeated measures); 10-min combat casualty simulation Primary outcomes: Biological reactivity |

| Hormones: Cortisol, α-amylase Cardiovascular: HR, SBP, DBP Methods: Saliva (cortisol, α-amylase); measured at baseline (−20 min), immediately pre-simulation (−5 min), midway simulation (+5 min), post-simulation (+10 min), and during recovery (+20 min and +40 min) Fasted status: NR | Cortisol, μg/dL (F): Baseline (−20 min): 0.2 ± 0.1 Pre (−5 min): 0.2 ± 0.1 Mid (+5 min): 0.2 ± 0.1 * Post (+10 min): NR Post 2 (+20 min): 0.2 ± 0.1 * Post 3 (+40 min): 0.2 ± 0.1 * α-amylase, U/mL (F): Baseline (−20 min): 122.1 ± 69.7 Pre (−5 min): 136.6 ± 82.4 * Mid (+5 min): 193.1 ± 142.9 * Post (+10 min): NR Post 2 (+20 min): 141.3 ± 120.6 Post 3 (+40 min): 117.7 ± 91.5 HR, beats/min (F): Baseline (−20 min): 78.9 ± 13.7 Pre (−5 min): 81.6 ± 15.3 * Mid (+5 min): 126.9 ± 18.3 * Post (+10 min): 89.9 ± 17.1 Post 2 (+20 min): 84.9 ± 13.4 Post 3 (+40 min): 76.6 ± 12.8 SBP, mmHg (F): Baseline (−20 min): 116.0 ± 11.0 Pre (−5 min): 128.1 ± 12.7 * Mid (+5 min): NR Post (+10 min): 128.6 ± 11.4 Post 2 (+20 min): 118.6 ± 11.2 Post 3 (+40 min): 115.9 ± 10.3 DBP, mmHg (F): Baseline (−20 min): 74.5 ± 8.5 Pre (−5 min): 80.2 ± 8.4 * Mid (+5 min): NR Post (+10 min): 81.7 ± 7.9 Post 2 (+20 min): 76.0 ± 8.4 Post 3 (+40 min): 73.9 ± 9.3 * p < 0.01 (time, vs. baseline) | None |

|

| Nindl et al., 2012 [56] RQ: 57.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (~4 months); Israeli Defense Force gender-integrated basic recruit training program (Tel Hashomer, Israel) Primary outcomes: Body composition, inflammation, fitness |

| Hormones: IGF-1, free IGF-1 Methods: Serum Fasted status: Overnight | IGF-1 (F): Pre: 470.0 (15.8) ng/mL Post: 524.6 (15.3) ng/mL p > 0.05 (sex) p < 0.05 (time) Free IGF-1 (F): Pre: 0.49 (0.04) ng/mL Post: 0.52 (0.05) ng/mL p > 0.05 (Sex) p > 0.05 (Time) | Body composition: BM, FM, FFM, BF Inflammation: IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-2, IGFBP-3, IGFBP-4, IGFBP-5, IGFBP-6 |

|

| O’Leary et al., 2023 †,‡ [59] RQ: 87.9% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (36 h); field exercise in energy deficit as part of Commissioning Course at the Royal Military Academy (Sandhurst, UK) Primary outcomes: Bone turnover, diet, energy expenditure |

| Hormones: Cortisol, testosterone Methods: Plasma Fasted status: Overnight | Cortisol, nmol/L: Baseline: 650.8 ± 229.9 Post: 578.5 ± 219.5 Recovery: 606.9 ± 165.3 p > 0.05 (time) Testosterone, nmol/L: Baseline: 1.4 ± 1.2 Post: 0.8 ± 0.5 Recovery: 0.8 ± 0.3 p > 0.05 (time) | Bone turnover: βCTX, PINP, parathyroid hormone, total 25(OH)D, albumin-adjusted calcium, total 1,25(OH)2D, phosphate, total 24,25(OH)2D Diet: carbohydrate, protein, and fat intake Energetics: energy expenditure and balance (accelerometry and doubly labeled water) |

|

| O’Leary et al., 2024 ‡ [60] RQ: 66.7% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (44 wk); Commissioning Course (basic combat training program) at the Royal Military Academy (Sandhurst, UK) Primary outcomes: Energy balance, bone turnover, metabolic and endocrine statuses |

| Hormones: Cortisol, IGF-1, testosterone Methods: Plasma (cortisol, testosterone) and serum (IGF-1) Fasted status: Overnight | Cortisol, nmoll/L (F) * Baseline: 776.3 ± 174.6 Term 2: 724.3 ± 226.6 Term 3: 733.6 ± 202.4 IGF-1, nmmol/L (F) Baseline: 215.5 ± 52.5 Term 2: 230.4 ± 65.2 Term 3: 233.7 ± 52.7 Testosterone, nmoll/L (F) * Baseline: 0.7 ± 0.2 Term 2: 0.7 ± 0.3 Term 3: 1.2 ± 1.5 * p < 0.05 (time) | Body composition: LM, FM, BF Energetics: energy intake, energy balance, energy expenditure, macronutrient intake Bone turnover: Bone alkaline phosphatase, βCTX, PINP Metabolic and endocrine statuses: Leptin, triiodothyronine, free thyroxine, thyroid-stimulating hormone, sex hormone-binding globulin, free androgen index |

|

| Strahler et al., 2015 ‡ [65] RQ: 65.6% | Police Design: Cross-sectional; simulated school shooting exercise as part of basic or refresher training session Primary outcomes: Psychobiological stress |

| Hormones: α-amylase Methods: Saliva Fasted status: NR | α-amylase, U/mL (F): Basal: 125.8 (26.6) +1 min: 259.2 (69.2) +20 min: 199.7 (40.4) +40 min: 218.2 (32.9) p-value NR | Psychological state: Chronic and acute stress, mood Physiological stress: Cortisol, HR, HR variability (only α-amylase data were disaggregated by sex) |

|

| Szivak et al., 2018 †,# [22] RQ: 65.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (2 wk); U.S. Navy SERE training (Kittery and Rangeley, ME, USA) Primary outcomes: Neuroendocrine markers and performance |

| Hormones: Epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine, cortisol, testosterone, NPY Methods: Serum (cortisol, testosterone), plasma (NPY, epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine) Fasted status: Yes (time-period not specified) | Cortisol, nmol/L (F): Baseline: 139.8 ± 60.6 Stress: 937.4 ± 276.4 Recovery: 251.1 ± 60.5 Testosterone, nmol/L (F): Baseline: 1.1 ± 0.2 Stress: 1.8 ± 0.3 Recovery: 1.0 ± 0.2 NPY, pg/mL (F): Baseline: 356.7 ± 53.5 Stress: 317.3 ± 92.2 Recovery: 174.3 ± 26.6 Epinephrine, pmol/L (F): Baseline: 234.7 ± 88.8 Stress: 361.6 ± 155.5 Recovery: 182.8 ± 82.3 Norepinephrine, pmol/L (F): Baseline: 2291.5 ± 360.0 Stress: 6511.0 ± 2089.6 Recovery: 3855.5 ± 1267.4 Dopamine, pmol/L (F): Baseline: 87.0 ± 13.3 Stress: 169.6 ± 36.0 Recovery: 133.7 ± 30.8 p-values: NR for all outcomes | Physical performance: Dominant handgrip strength, vertical jump height |

|

| Tomei et al., 2008 [67] RQ: 34.4% | Police Design: Cross-sectional; urban stressor exposure (Rome, Italy) Primary outcomes: Testosterone |

| Hormones: Free testosterone Methods: Plasma Fasted status: Overnight | Free testosterone, pg/mL: Baseline: 1.4 ± 0.6 p < 0.001 (control) | None |

|

| Vikmoen et al., 2020 † [68] RQ: 63.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (14 days) during a 6-day field-based Selection Exercise at Rena Military Camp (Rena, Norway) Primary outcomes: Body composition and performance |

| Hormones: Cortisol, IGF-1, testosterone Methods: Serum Fasted status: Overnight | Cortisol, ug/dL (F): Pre: 343 ± 219 Post 24 h: 771 ± 155 * Post 72 h: 677 ± 196 * Post 1 wk: 666 ± 101 * Post 2 wk: 711 ± 82 * IGF-1, nmol/L (F): Pre: 17.6 ± 5.1 Post 24 h: 10.1 ± 2.6 * Post 72 h: 13.7 ± 4.3 * Post 1 wk: 23.7 ± 6.9 * Post 2 wk: 26.8 ± 7.9 * Testosterone, nmol/L (F): Pre: 1.0 ± 0.5 Post 24 h: 1.2 ± 0.4 Post 72 h: 1.1 ± 0.4 Post 1 wk: 1.1 ± 0.3 Post 2 wk: 1.0 ± 0.3 * p < 0.05 (time, vs. pre) | Body composition: BM, MM, FM Performance: CMJ height and maximal power, medicine ball throw, anaerobic performance (Evacuation test) Other: Creatine kinase |

|

| Author, Year | Tactical Domain and Study Characteristics | Sample Characteristics | Body Composition Assessment and Outcomes | Other Markers Analyzed | Impact of Stress and Sex on Body Composition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes and Assessment Details | Aggregate-Level Study Data (Mean ± SD) a | |||||

| Ahmed et al., 2020 [32] RQ: 53.1% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (5 days); artic-like field training exercise at the Canadian Forces Base (Meaford, Ontario, Canada) Primary outcomes: Energy intake and expenditure |

| Total: BMI (clothed), BM (clothed), FM, FFM, BF Methods: Deuterium isotope dilution (0.12 g 2H per est. kg TBW) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: NR | BMI (F): Pre: 29.0 ± 4.5 kg/m2 Post: 28.3 ± 4.4 kg/m2 * Total BM (F): Pre: 81.8 ± 11.7 kg Post: 80.1 ± 11.0 kg * Total FM (F): Pre: 27.9 ± 6.4 kg Post: 24.9 ± 7.9 kg * Total FFM (F): Pre: 53.9 ± 5.2 kg Post: 55.3 ± 3.2 kg * Total BF (F): Pre: 31.4 ± 6.1% Post: 27.4 ± 8.2% * * p < 0.05 (time) | Energetics: energy expenditure, energy intake, energy deficit, energy availability |

|

| Andrews et al., 2010 † [33] RQ: 51.6% | Military Design: Cross-sectional; service members completing the Army Physical Fitness Test (Washington, DC, USA) Primary outcomes: Oxidative stress |

| Total: BMI, BM, LM, FM, BF Regional: Trunk FM and trunk BF Methods: DXA (Hologic QDR Discovery Wi, Bedford, MA, USA) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: NR | BMI (F): 29.9 ± 2.3 kg/m2 Total BM (F): 82.3 ± 11.0 kg * Total LM (F): 48.4 ± 5.9 kg * Total FM (F): 28.7 ± 4.0 kg Total BF (F): 36.0 ± 3.7% * Trunk FM (F): 13.1 ± 2.8 kg Trunk BF (F): 35.4 ± 5.2 kg * * p < 0.05 (sex) | Baseline: Fitness level, dietary intake Oxidative stress: Creatine kinase, C-reactive protein, glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase |

|

| Beckner et al., 2023 [34] RQ: 84.4% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (17 days); Cadet Leader Development Training at the U.S. Military Academy (West Point, NY, USA) Primary outcomes: Body composition, performance, energy expenditure, endocrine and metabolic status, metabolomics |

| Total: BM, dry LM, FM, TBW Methods: BIA (InBody 770, Cerritos, CA, USA) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: NR | Total BM: Pre: 71.2 ± 10.6 kg * Post: 68.6 ± 10.7 kg ** Total dry LM: Pre: 14.2 ± 1.3 kg * Post: 14.2 ± 1.4 kg Total FM: Pre: 18.6 ± 7.6 kg * Post: 15.7 ± 7.3 kg Total TBW: Pre: 38.5 ± 3.3 kg Post: 38.7 ± 3.9 kg * p ≤ 0.05 (sex) ** p ≤ 0.05 (sex, post vs. pre change) | Energetics: total daily energy expenditure (doubly labeled water) Endocrine status: estradiol, progesterone, total testosterone, free testosterone Metabolic status: serum glycerol, free fatty acids, serum leptin Metabolomics: all metabolites within the lipid super pathway Performance: lower body power |

|

| Charles et al., 2008 [35] RQ: 75.0% | Police Design: Cross-sectional; Buffalo Cardio-metabolic Occupational Police Stress Study (Buffalo Police Department, Buffalo, NY, USA) Primary outcomes: Adiposity and oxidative stress |

| Total: BMI, WC, waist-to-hip ratio, waist-to-height ratio, abdominal height Methods: Digital scale (clothed, without shoes), tape measure after exhale (nearest 0.5 cm) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: 12-h (for blood collection) | BMI (F): 26.3 ± 4.6 kg/m2 * WC (F): 80.4 ± 10.2 cm * Waist-to-hip ratio (F): 0.77 ± 0.06 * Waist-to-height ratio (F): 0.48 ± 0.06 * Abdominal height (F): 19.0 ± 3.0 cm * * p < 0.001 (sex) | Oxidative stress: Oxidative stress score, glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, vitamin C, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity |

|

| Cho et al., 2017 [36] RQ: 42.4% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (8 wk); during 16-wk Officer training course at the Korea Third Military Academy (Yeongcheon, South Korea) Primary outcomes: Reproductive function |

| Total: BM, BMI, WC Methods: Tape measurement during minimal respiration (WC) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: Overnight | Total BM: 4 wk: 60.0 ± 6.8 kg 8 wk: 59.3 ± 6.4 kg * BMI: 4 wk: 22.7 ± 2.3 kg/m2 8 wk: 22.4 ± 2.2 kg/m2 * WC: 4 wk: 67.0 ± 5.8 cm 8 wk: 67.1 ± 4.6 cm * p < 0.05 (time) | Reproductive function: regularity, CRH, cortisol, prolactin, endorphin-β, NPY, leptin, orexin-A, ghrelin, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estradiol, thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroxine |

|

| Coge et al., 2024 ‡ [37] RQ: 65.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (34 wk); recruit basic training (Instituto Superior Técnico Militar of Angola) Primary outcomes: Body composition, fitness, and performance |

| Total: BM, BMI, FM Methods: BIA (OMRON HBF 510, Omron Healthcare, Inc., Hoffman Estates, IL, USA) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: NR | Total BM (F): Pre: 65.5 ± 12.0 kg Post: 63.8 ± 11.4 kg *, ** BMI (F): Pre: 24.9 ± 5.3 kg/m2 Post: 24.2 ± 5.0 kg/m2 ** FM (F): Pre: 28.7 ± 4.6 kg Post: 27.2 ± 4.4 kg * p < 0.05 (sex), ** p < 0.01 (time) | Fitness: VO2max, sprint performance Performance: CMJ, medicine ball throw, push-ups, curl-ups |

|

| Conkright et al., 2022 [38] RQ: 68.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (5 days); simulated military operational stress protocol with restricted sleep and caloric intake Primary outcomes: Extracellular vesicle biomarkers |

| Total: BM, BF Methods: Air displacement plethysmography (BOD POD, Cosmed, Concord, CA, USA) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: Overnight | Total BM (F): 70.8 ± 8.1 kg * Total BF (F): 28.2 ± 6.7% * * p < 0.05 (sex) | Performance: Baseline VO2peak, average knee extensor maximal voluntary contraction Extracellular vesicle biomarkers: Concentration, size Other: Contraceptive use, sleep, caloric intake, perceived exertion, myoglobin, creatine kinase |

|

| Cuddy et al., 2015 [39] RQ: 27.3% | Fire Design: Prospective cohort (3 days); live wildland fire suppression (Fort Collins, CO, USA) Primary outcomes: Physiological strain, thermal responses, energy expenditure |

| Total: BM Methods: Digital scale Hydration status: NR Fasted status: NR | Total BM (F): Pre: 66.7 ± 4.4 Post: 65.7 ± 4.7 p-value NR | Physiological strain: Physiological strain index rating, heart rate Thermal responses: Core and skin (chest) temperature Energetics: Energy expenditure, activity, water turnover |

|

| Dawes et al., 2023 [40] RQ: 64.5% | Police Design: Retrospective cohort; archived health and fitness records from officers with ≥5 y experience Primary outcomes: Body composition and performance |

| Total: BM, BMI Methods: Digital scale Hydration status: NR Fasted status: NR | Total BM (F, n = 23): Year 1: 76.5 ± 14.9 kg Year 5: 79.1 ± 15.9 kg p = 0.106 (time) BMI (F, n = 24): Year 1: 26.2 ± 4.3 kg/m2 Year 5: 27.1 ± 4.4 kg/m2 p = 0.105 (time) | Performance: Vertical jump height, sit-ups, push-ups Fitness: VO2max |

|

| Dicks et al., 2023 [41] RQ: 56.3% | Police Design: Cross-sectional; physical readiness assessment (Midwestern Police Department) Primary outcomes: Physical Readiness Assessment performance and body composition |

| Total: BM, BMI, BF, FFM Methods: BIA (Tanita, TBF-300A, Tokyo, Japan) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: NR | Total BM (F): 73.3 ± 12.2 kg * BMI (F): 26.6 ± 2.5 kg/m2 Total BF (F): 33.7 ± 5.0% Total FFM (F): 48.2 ± 5.6 kg ** ** p < 0.001 (sex), * p < 0.05 (sex) | Performance: Handgrip strength, physical activity rating, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, time to complete the physical readiness assessment |

|

| Evans et al., 2008 [42] RQ: 60.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (~4 months); Israeli Defense Force gender-integrated basic recruit training program (Tel Hashomer, Israel) Primary outcomes: Body composition, fitness, bone turnover, endocrine regulation, inflammation |

| Total: LM, FM, BF Methods: four-site skinfolds (BF); weight multiplied by BF (FM); FM subtracted from weight (LM) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: Overnight | Total LM (F): Pre: 41.9 ± 5.3 kg Post: 43.8 ± 5.0 kg * Total FM (F): Pre: 19.0 ± 5.8 kg Post: 18.3 ± 5.4 kg * Total BF (F): Pre: 30.7 ± 4.9% Post: 29.0 ± 4.5% * p < 0.002 (time) | Fitness: VO2max, 2-km run time Bone turnover: Bone alkaline phosphatase, PINP, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, C-telopeptide cross-links of type I collagen Endocrine regulation: Albumin, calcium, PTH Inflammation: TNF-α, IL-1b, IL-6 |

|

| Gifford et al., 2021 [45] RQ: 81.8% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (11 months); Commissioning Course (basic combat training) at the Royal Military Academy (Sandhurst, UK) Primary outcomes: Reproductive and metabolic function Part of the Female Endocrinology in Arduous Training (FEAT) Study |

| Total: BM, FM, FFM, VAT Regional: FM and FFM for arms, legs, trunk, gynoid, android Methods: DXA (GE Lunar iDXA, GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: 12-h | Total BM: 14 wk: 63.3 ± 7.2 kg 29 wk: 64.7 ± 6.8 kg 43 wk: 64.3 ± 6.9 kg * Total FM: 14 wk: 14.5 ± 3.4 kg 29 wk: 16.2 ± 3.2 kg 43 wk: 15.6 ± 3.3 kg *** Total FFM: 14 wk: 49.1 ± 5.1 kg 29 wk: 48.5 ± 4.9 kg 43 wk: 48.7 ± 4.9 kg * VAT: 14 wk: 95.4 ± 72.5 g 29 wk: 132.5 ± 93.4 g 43 wk: 137.2 ± 72.6 g ** Regional FM—arms: 14 wk: 1.7 ± 0.4 kg 29 wk: 1.9 ± 0.4 kg 43 wk: 1.8 ± 0.4 kg ** Regional FM—legs: 14 wk: 6.2 ± 1.4 kg 29 wk: 6.7 ± 1.4 kg 43 wk: 6.5 ± 1.4 kg *** Regional FM—trunk: 14 wk: 5.8 ± 1.8 kg 29 wk: 6.8 ± 1.8 kg 43 wk: 6.4 ± 1.8 kg *** Regional FM—gynoid: 14 wk: 3.0 ± 0.7 kg 29 wk: 3.4 ± 0.7 kg 43 wk: 3.3 ± 0.7 kg *** Regional FM—android: 14 wk: 0.7 ± 0.3 kg 29 wk: 0.9 ± 0.3 kg 43 wk: 0.8 ± 0.3 kg *** Regional FFM—arms: 14 wk: 5.2 ± 0.7 kg 29 wk: 5.3 ± 0.7 kg 43 wk: 5.1 ± 0.7 kg * Regional FFM—legs: 14 wk: 16.8 ± 2.0 kg 29 wk: 61.6 ± 1.9 kg 43 wk: 16.6 ± 1.8 kg Regional FFM—trunk: 14 wk: 23.6 ± 2.5 kg 29 wk: 23.1 ± 2.4 kg 43 wk: 23.5 ± 2.6 kg *** p < 0.0001 (time) Regional FFM—gynoid: 14 wk: 7.7 ± 0.9 kg 29 wk: 7.5 ± 0.9 kg 43 wk: 7.6 ± 1.0 kg ** Regional FFM—android: 14 wk: 3.2 ± 0.4 kg 29 wk: 3.2 ± 0.4 kg 43 wk: 3.3 ± 0.4 kg * *** p < 0.0001, ** p ≤ 0.001, * p ≤ 0.02 (time) | Fasting metabolic: Leptin, HOMA2 IR, IGF-1, glucose, nonesterified fatty acids, total triiodothyronine, free thyroxine, thyroid-stimulating hormone Basal reproductive: Luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone (and its ratio), gonadotropin-releasing hormone, inhibin B, SHBG, free androgen index, DHEA, androstenedione, progesterone Others: C-peptide, creatinine, estradiol, anti-Müllerian hormone, prolactin, testosterone |

|

| Kargl et al., 2024 [49] RQ: 60.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (10 wk); U.S. Marine Corps Officer Candidate School Primary outcomes: Inflammation, oxidative stress, stress, sleep, performance |

| Total: BM, BMI Methods: Digital scale Hydration status: NR Fasted status: Not fasted | Total BM (F): Wk 0: 66.3 ± 6.6 kg Wk 10: 66.2 ± 6.0 kg p > 0.05 (time) p < 0.05 (sex) BMI (F): Wk 0: 24.2 ± 1.7 kg/m2 Wk 10: 24.2 ± 1.9 kg/m2 p > 0.05 (time) p < 0.05 (sex) | Inflammation: C-reactive protein, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, interferon-γ Oxidative stress: Peroxidized lipid, protein carbonyls, and antioxidative capacity Sleep: Disturbances (Athlete Sleep Screening Questionnaire) Stress: Perceived Stress Scale Performance: Physical fitness and combat fitness test scores |

|

| Krugly et al., 2023 [50] RQ: 54.5% | Police Design: Retrospective cohort; three semesters of police education in Sweden Primary outcomes: Fitness and mental health |

| Total: BM, BMI Methods: Digital scale Hydration status: NR Fasted status: NR | Total BM (F): Semester 1: 67.8 ± 7.9 kg Semester 3: 68.4 ± 7.9 kg BMI (F): Semester 1: 23.3 ± 2.4 kg/m2 Semester 3: 23.5 ± 2.3 kg/m2 p-values: NR | Fitness: Push-ups, sit-ups, grip strength, VO2max, standing long jump, agility (Harres test and L-run test), self-reported physical activity Mental health: Self-reported mental health and perceived police ability |

|

| Lieberman et al., 2008 [51] RQ: 66.7% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (13 wk); U.S. Marine Corps basic training (Parris Island, SC, USA) Primary outcomes: Body composition, metabolic status, mood state |

| Total: BM, FM, FFM, BF, BMM Methods: DXA (DPX-L, Lunar Radiation Corp) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: Overnight | Total BM: Wk 1: 63.9 ± 0.8 kg Wk 5: 61.8 ± 0.8 kg Wk 8: 61.4 ± 0.8 kg Wk 12: 61.7 ± 0.7 kg * Total FM: Wk 1: 19.5 ± 0.6 kg Wk 5: 16.2 ± 0.6 kg Wk 8: 15.2 ± 0.5 kg Wk 12: 14.7 ± 0.5 kg * Total FFM: Wk 1: 41.7 ± 0.5 kg Wk 5: 42.7 ± 0.5 kg Wk 8: 43.3 ± 0.5 kg Wk 12: 44.1 ± 0.5 kg * Total BF: Wk 1: 30.2 ± 0.7% Wk 5: 26.1 ± 0.7% Wk 8: 24.6 ± 0.7% Wk 12: 23.7 ± 0.7% * Total BMM: Wk 1: 2.8 ± 0.1 kg Wk 5: 2.8 ± 0.1 kg Wk 8: 2.8 ± 0.1 kg Wk 12: 2.9 ± 0.1 kg * p < 0.001 (time, vs. wk 1) | Metabolic status: Cholesterol (total, LDL, HDL), free fatty acids, cortisol, glucose Mood state: POMS subscales (fatigue, confusion, depression, tension, anger, vigor) |

|

| Lieberman et al., 2012 [52] RQ: 60.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (12 wk); U.S. Marine Corps basic training (Parris Island, SC, USA) Primary outcomes: Body composition, mood state, metabolic status |

| Total: BM, FM, LM, BMM Methods: DXA (model DPX-L, LUNAR Radiation Corp, Madison, WI, USA) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: Overnight | Total BM: Pre: 63.6 ± 5.5 kg Post: 62.1 ± 4.9 kg * Total FM: Pre: 19.0 ± 4.4 kg Post: 14.8 ± 3.4 * Total LM: Pre: 41.7 ± 3.7 kg Post: 44.4 ± 3.9 kg * Total BMM: Pre: 2.9 ± 0.4 kg Post: 3.0 ± 0.4 kg * p ≤ 0.001 (time) | Mood state: POMS subscales (fatigue, confusion, depression, tension, anger, vigor) Metabolic status: Substance P, fructosamine, adrenocorticotropic hormone, cholesterol (total, HDL, LDL), triglycerides, free fatty acids, DHEA-S |

|

| McClung et al., 2009 [53] RQ: 60.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (8 wk); U.S. Army basic combat training course (Fort Jackson, SC, USA) Primary outcomes: Iron status, performance, mood state |

| Total: BM Methods: Digital scale Hydration status: NR Fasted status: Overnight | Total BM—Iron: Pre: 61.8 ± 9.4 kg Post: 61.8 ± 8.2 kg Total BM—Placebo: Pre: 62.2 ± 8.5 kg Post: 61.9 ± 6.9 kg p-values: NR | Iron status: Hemoglobin, red blood cell distribution width, ferritin, transferrin saturation, soluble transferrin receptor Performance: 2-mile run time Mood state: POMS subscales (fatigue, confusion, depression, tension, anger, vigor) |

|

| McFadden et al., 2024b [55] RQ: 72.7% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (11 wk); U.S. Marine Corps basic training (Parris Island, SC, USA) Primary outcomes: Performance, resilience, wearable tracking Part of a larger study, the U.S. Marine Corps Gender-Integrated Recruit Training study |

| Total: BM Methods: Digital scale Hydration status: NR Fasted status: NR | Total BM (F): Wk 2: 62 ± 8 kg Wk 11: 61 ± 7 kg p-value NR | Performance: Physical and combat fitness tests, lower body strength and power Resilience: Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, workload, self-reported sleep, stress Wearable tracking: energy expenditure, distances, sleep, acceleration Other: Salivary cortisol |

|

| Nindl et al., 2012 [56] RQ: 57.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (~4 months); Israeli Defense Force gender-integrated basic recruit training program (Tel Hashomer, Israel) Primary outcomes: Body composition, inflammation, fitness |

| Total: BM, FM, FFM, BF Methods: Digital scale, four-site skinfolds (biceps, triceps, suprailiac, subscapular) Hydration status: NR Fasted status: Overnight (for blood collection) | Total BM (F): Pre: 61.6 (1.1) kg Post: 62.7 (1.1) kg * Total FM (F): Pre: 19.6 (0.6) kg Post: 19.0 (0.6) kg *,** Total FFM (F): Pre: 42.0 (0.6) kg Post: 43.7 (0.5) kg *,** Total BF (F): Pre: 31.3 (0.5)% Post: 29.7 (0.5)% *,** * p < 0.05 (sex), ** p < 0.05 (time) | Inflammation: IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IGF-1, free IGF-1, IGF binding proteins-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, and -6 Fitness: VO2max |

|

| Øfsteng et al., 2020 † [57] RQ: 63.6% | Military Design: Prospective cohort (17 days); 10-day military field exercise followed by 7 days of recovery Primary outcomes: Body composition and performance |