Abstract

Objectives: The therapeutic use of controlled substances, particularly opioids, stimulants, and benzodiazepines, has significantly increased in recent decades. This is often accompanied by non-medical use and diversion, posing challenges for healthcare professionals and forensic experts monitoring potential misuse. As a result, the blurred boundary between legitimate therapy and substance abuse complicates the interpretation of toxicological results in clinical, legal, and occupational contexts. Methods: This review summarizes recent strategies for distinguishing therapeutic from illicit drug use through the analysis of substances and their metabolites in biological samples using sensitive and specific analytical methods. Results: Traditional drug abuse testing methods, based on parent substance detection, often lack the specificity needed to differentiate therapeutic use from illicit intake. Therefore, advanced analytical methods are required to accurately differentiate the source, route, and adherence to therapy. Therapeutic and illicit forms of the same substance can exhibit distinct metabolic profiles, with certain metabolites serving as biomarkers for illicit drug use. In some cases, chiral analysis may also aid in determining the drug source. Other studies have shown that the ratio of the parent compound to its metabolites (or between different metabolites) may reflect the pattern of use, such as chronic versus acute use or the route of administration. Illicit drugs may also contain synthesis by-products or cutting agents, detectable through advanced techniques. Conclusions: Metabolite profiling offers a robust approach for differentiating therapeutic from illicit drug use and is expected to be increasingly applied in clinical toxicology, forensic investigations, workplace testing, and/or doping control.

1. Introduction

The global increase in the therapeutic use of controlled substances, particularly opioids, benzodiazepines, stimulants, cannabinoid-based medicines has paralleled a troubling rise in their non-medical use, diversion, and associated morbidity [1,2]. While these drugs remain essential for managing pain, anxiety, sleep disorders, and other conditions, their misuse has become a major public health and forensic concern. The overlapping biochemical signatures of legitimate therapeutic intake and illicit consumption often blur the boundary between compliance and abuse, creating interpretative challenges in clinical toxicology, workplace testing, and legal settings [3].

Traditional toxicological screening methods, largely based on immunoassays, detect parent compounds or specific metabolites but often lack the specificity required to discriminate between therapeutic dosing, chronic misuse, and illicit analog consumption [4]. The development and application of chromatographic and mass spectrometric techniques such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS), liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) has transformed drug analysis by enabling the precise identification of drug-specific metabolic pathways and biomarkers [5]. These advancements now allow differentiation between pharmaceutical formulations and clandestine preparations, offering insight into both the source and metabolic fate of a given substance [6]. Among opioids, the distinction between therapeutic administration (e.g., morphine, oxycodone) and illicit use (e.g., heroin, fentanyl analogs) can be elucidated through unique metabolite markers such as 6-monoacetylmorphine or norfentanyl [7]. For benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, complex metabolic interconversion such as between diazepam, nordiazepam, and oxazepam, necessitates careful interpretation of parent/metabolite ratios and matrix-specific detection windows [8,9]. Similarly, stimulant analysis increasingly relies on enantiomeric profiling to differentiate legitimate amphetamine-based medications from illicit methamphetamine or designer analogs [10]. In the case of cannabinoids, advanced metabolomic and isotopic approaches can distinguish pharmaceutical formulations (e.g., dronabinol, nabiximols) from recreational cannabis exposure, even in chronic users [11].

Obviously, the metabolite profiling has emerged as a cornerstone strategy for differentiating therapeutic from illicit drug use. By integrating quantitative metabolite ratios, metabolic fingerprinting, and multi-matrix testing (e.g., plasma, urine, hair, oral fluid), it is possible to achieve a nuanced understanding of drug exposure patterns, metabolic dynamics, and compliance with prescribed therapy [12]. This article provides a comprehensive overview of analytical and interpretative approaches for clarifying the often-ambiguous boundary between medical treatment and abuse with key controlled substance classes. The main objective of this review is to provide a critical synthesis of contemporary evidence regarding the utility of metabolite profiling in differentiating therapeutic application from illicit consumption.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to gain a better understanding of differentiating therapeutic from illicit drug use through metabolite profiling, we conducted an in-depth literature review on the Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed and ResearchGate databases. The initial search yielded over 2000 literature sources related to the topic. In result, we selected over 300 articles, mostly published in the last fifteen years, and comprehensively analyzed the available scientific information. Both review and research articles written in English were cited in the manuscript. Additionally, scientific information was retrieved from the internet databases of the European Medicine Agency (EMA), European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA) and other organisations.

3. Opioids

Opioid agonists include natural opiates, semisynthetic alkaloids derived from the opium poppy, and fully synthetic compounds that act via the same mechanism [13]. While some of these substances were originally developed for medical purposes, certain agents, such as heroin, eventually became primarily used for recreational purposes. Opioid receptors, which are G protein–coupled, mediate the effects of both endogenous ligands (e.g., endorphins) and exogenously administered opioids. The three main types of classical opioid receptors are μ (mu), δ (delta), and κ (kappa) [13,14]. Interaction with these receptors can elicit agonist, partial agonist, or antagonist responses. In clinical settings, most opioids exert an agonistic effect, producing analgesia [15]. They remain a primary therapeutic option for managing short- to intermediate-duration moderate-to-severe pain, including in oncological practice. Certain opioids are also employed as anesthetic adjuvants and as antitussive agents [16]. Prolonged opioid use, however, is limited by the risk of multiple adverse effects, the most serious being respiratory depression. Other notable manifestations include constipation, nausea, pruritus, and paradoxical hyperalgesia (enhanced pain sensitivity). Additionally, opioids induce molecular adaptive changes that reduce their efficacy and contribute to the development of dependence, highlighting the complex and nuanced safety profile of these agents [17]. Moreover, due to their pronounced euphoric effects, μ-opioid agonists are among the most frequently abused substances, with substantial health, social, and economic consequences [13].

In response to the profound psychosocial consequences associated with opioid (mis)use, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association) introduced the term Opioid Use Disorder (OUD). This designation characterizes the chronic use of opioids that results in clinically significant distress or functional impairment [18]. The clinical presentation is marked by an irresistible craving for opioids, progressive tolerance, and the emergence of withdrawal symptoms upon cessation of use. Consequently, the spectrum of OUD encompasses conditions ranging from subclinical dependence to full-blown opioid addiction [19,20]. In this context, the opioid crisis remains an urgent global challenge, with the current phase frequently described as the “fourth wave,” characterized by epidemic proliferation, including combined use with stimulants. The prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders is markedly higher compared to previous phases [21,22]. Data from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicate that of roughly 600,000 drug-related deaths recorded globally, approximately 80% involve opioids, with nearly one-quarter resulting directly from overdose [23]. Forecasts suggest that by 2029, as many as 1.2 million people in the United States and Canada alone could succumb to opioid overdoses [24]. These statistics reflect not only heroin misuse but also the extensive and often inappropriate consumption of prescription opioid analgesics [25]. Given that this public health crisis has recently affected other regions, including Australia and Europe, official figures likely significantly underestimate the true magnitude of the epidemic [25,26,27].

The opioid medications most commonly misused include hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, buprenorphine, fentanyl, tramadol, and morphine [28,29,30]. Even in cases of nonmedical use, the preferred route of opioid administration remains oral, followed by intravenous and intranasal routes, with buccal administration being considerably less common [25,31,32,33]. Currently, therapeutic interventions for managing opioid dependence include buprenorphine, methadone, and extended-release naltrexone, as well as the α2-adrenergic agonist lofexidine to mitigate the acute manifestations of opioid withdrawal [20,34]. Despite the availability of treatment options, the most recent United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime report indicates that fewer than 20% of affected individuals globally have access to adequate care. In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that the primary drivers of OUD are substances legally approved for medical use. Estimates suggest that approximately 60 million individuals engaged in nonmedical opioid use in 2021. These data underscore the urgent need to reassess strategies for biomonitoring opioid use while ensuring that the control of illicitly manufactured or diverted pharmaceutical opioids is not neglected [35].

In contemporary practice, toxicochemical analysis of opioids has emerged as an essential tool, extending far beyond its traditional role in toxicology and forensic investigations. Its utility now spans occupational health, military oversight, and sports medicine, where results can directly shape both clinical management and legal outcomes. Within pain management programs, systematic opioid testing, most often via urine analysis has become pivotal for verifying adherence to prescribed therapy and for preventing diversion or substitution of medications. These realities underscore the critical need to distinguish medical use from non-medical opioid consumption with precision and reliability [29,36].

Opioid detection mainly employs immunoassays, which are inexpensive but prone to cross-reactivity [37]. Chromatography coupled with MS remains the gold standard for confirmation, offering superior specificity despite higher complexity and cost [38,39]. In recent years, Mayo Clinic laboratories have advanced opioid analysis with the implementation of high-resolution targeted opioid screening (TOSU), leveraging LC-MS/MS. This approach enables the qualitative identification of 33 distinct opioids and their metabolites in urine without the need for hydrolysis, providing clinicians with a powerful tool to monitor therapeutic compliance and detect unauthorized use (Table 1). Such innovations not only enhance diagnostic accuracy but also reflect the evolving landscape of opioid monitoring, where precision is paramount for both patient care and public health [37,40]. Recent studies combine untargeted ultra high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC)-HRMS metabolomics with machine learning classifiers to detect characteristic exposure signatures and to differentiate natural opioids (for example morphine or codeine) from potent synthetic analogues such as fentanyl derivatives. These workflows often rely on endogenous metabolomic perturbations as indirect biomarkers when parent new synthetic opioid compounds are present at very low concentrations in biological matrices. Such combined mass spectrometry–machine learning strategies substantially improve screening sensitivity for novel opioids and help prioritize candidate metabolites for subsequent tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) confirmation [41].

Table 1.

List of the thirty-three target analytes in the TOSU assay, including parent compounds and their metabolites [37,40,41].

In addition to a thorough command of laboratory analytical techniques, a deep understanding of opioid metabolism is indispensable when interpreting biological specimens—most commonly urine and blood. Many clinically used opioids undergo metabolic conversion into other active opioids and/or may appear as “manufacturing-related impurities”. If such transformations are overlooked, they may yield misleading conclusions regarding patient misuse or drug exposure [39]. Opioid metabolism occurs mainly in the liver through Phase I (cytochrome P450 (CYP)-mediated oxidation/reduction) and Phase II (glucuronidation) reactions. Variability in metabolism arises from CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 activity, influenced by drug interactions and genetic polymorphisms [42]. A key example is the CYP2D6-mediated O-demethylation of codeine to morphine, which accounts for about 10% of the administered dose and underlies codeine’s analgesic effect (Figure 1). Ultra-rapid metabolizers may generate toxic morphine levels, while similar pathways convert oxycodone and hydrocodone to oxymorphone and hydromorphone, respectively. At higher doses, secondary metabolites such as hydrocodone and hydromorphone may appear, complicating toxicological analysis. In contrast, opioids like buprenorphine, fentanyl, meperidine, methadone, and tramadol are metabolically independent, exhibiting distinct pharmacokinetic and toxicological profiles that demand precise analytical characterization [39,43].

Figure 1.

Simplified metabolic pathways of major opioids and their shared metabolites.

3.1. Morphine/Codeine/Diacethylmorphine (Heroin)

In most conventional immunoassays designed to detect opioid misuse, the prototypical opioid, morphine, is employed as the sole calibrator. Beyond serving as a direct analyte for its own detection, morphine also functions as an indirect biomarker of codeine, heroin, and ethylmorphine misuse, owing to its role as their principal metabolite [29]. In clinical practice, a threshold of 300 ng/mL (morphine equivalents) is commonly applied for opioid screening, a level sensitive to morphine and codeine but potentially insufficient for detecting other opioids. For federal and workplace drug testing, however, substantially higher cut-off values have been established—2000 ng/mL for screening and 4000 ng/mL (morphine)/2000 ng/mL (codeine) for confirmatory testing. These thresholds were introduced to minimize the likelihood of false-positive results, such as those arising from the consumption of poppy seeds or the legitimate therapeutic use of prescribed opioids during heroin abuse screening. Consequently, such stringent cut-offs may not always be appropriate for clinical diagnosis or therapeutic monitoring [42].

A major limitation of employing morphine as a biomarker of opioid misuse lies in the fact that this approach cannot distinguish between pharmaceutical-grade heroin and illicit street heroin [44]. Moreover, opioid misuse is not confined to morphine-like compounds, which increases the risk of false-negative results for certain semisynthetic and synthetic agents. At the same time, several commercially available immunoassays exhibit cross-reactivity with semisynthetic opioids. In addition, morphine-3-glucuronide, codeine, and 6-acetylmorphine may also react with morphine-specific antibodies, thereby contributing to the reporting of positive screening results [45]. Advanced immunoassays and LC-MS/MS methods provide substantially greater specificity, yet remain unavailable in many toxicology laboratories. An important step toward improving chromatographic separation in confirmatory testing of natural opioids is the preliminary hydrolysis of glucuronide conjugates, followed by derivatization of the parent compounds [29,46].

Codeine itself is not formed as a metabolite following the use of morphine, ethylmorphine, or pharmaceutical heroin. However, in addition to its presence after the administration of codeine-containing medications, it may also appear in the body after the consumption of street heroin—where it represents a metabolite of one of its common impurities—as well as after ingestion of poppy seed products or opium preparations [47]. For the detection of codeine use, in addition to monitoring its principal metabolite, morphine, the morphine/codeine (M/C) ratio can also be applied. Generally, an M/C ratio of <1 is considered indicative of codeine use alone, whereas a ratio of >1 suggests exposure to morphine or heroin. According to Ellis et al. (2016), an M/C ratio exceeding 1 in intravenous drug users constitutes a reliable indicator of fatal heroin intoxication, even in the absence of 6-MAM, particularly when combined with scene and autopsy findings confirming the heroin origin of morphine and codeine [48]. Nevertheless, this numerical threshold should not be regarded as absolute. In individuals with ultra-rapid CYP2D6 metabolism, the M/C ratio may exceed 1 even following codeine intake alone, underscoring the complexity of metabolic interactions and the necessity for cautious interpretation of toxicological results [49]. To support the reliable differentiation between opium/codeine users and heroin users, Al-Amri et al. proposed neopine as a biomarker. Neopine is detectable in opium, and consequently in the urine of opium and codeine users as well as after poppy seed ingestion, but is absent in heroin and in heroin users. Nonetheless, the possibility of combined use or interference from poppy-derived products cannot be fully excluded [50].

The short half-life of heroin, combined with its poor stability in aqueous environments, renders its direct detection in biological specimens both laborious and highly unsuitable as a reliable confirmation of use [51]. Once introduced into the body, heroin undergoes rapid enzymatic hydrolysis by esterases, yielding 6-MAM within minutes. This metabolite is a unique product of illicit heroin metabolism and is widely regarded as the gold standard biomarker for its monitoring (cut-off: 10 ng/mL). As a precursor to morphine, 6-MAM holds exceptional forensic value; however, its short elimination half-life narrows its window of detection to approximately 6–8 h, with optimal laboratory conditions extending this period to no more than 24 h post-consumption. Consequently, 6-MAM serves as a highly specific marker of very recent heroin use [52,53,54]. Nonetheless, its utility is limited. Detection of 6-MAM is challenging following oral or rectal administration of heroin due to extensive first-pass metabolism to morphine, and it cannot distinguish between pharmaceutical-grade diacetylmorphine—still in use in certain countries—and illicit street heroin [47]. In such scenarios, reliance solely on 6-MAM is insufficient for forensic differentiation. Instead, the analysis of additional opioid derivatives or their metabolites in blood or urine may provide stronger correlations with illicit formulations [51]. One such biomarker is meconin, a metabolite of noscapine—the second most abundant alkaloid in opium after morphine, and frequently encountered as an impurity in street heroin [55,56,57]. Accordingly, meconin should not be present in pharmaceutical-grade heroin [58]. Supporting this, Jones et al. (2015) developed an LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous quantification of codeine, morphine, 6-MAM, and meconin in umbilical cord tissue, demonstrating that meconin can serve as a biomarker of in utero heroin exposure [59]. Caution, however, is warranted when interpreting meconin detection, as noscapine is also found in antitussive formulations, and meconin itself has been identified as a component of the herbal supplement “Golden Seal”, commonly marketed as a dietary additive [60,61,62].

Another secondary biomarker arises from chemical impurities generated during illicit heroin synthesis, namely 6-acetylcodeine (6-AC). This compound is a synthetic by-product formed during the acetylation of morphine in opium extracts [46,63]. It has no therapeutic application and is rarely observed following the use of prescribed opioids. Some sporadic reports indicate that 6-AC can also be formed after the simultaneous administration of high intravenous doses of heroin (120–400 mg) and oral codeine (e.g., 50 mg as an antitussive) [64]. Accordingly, the presence of 6-AC in biological specimens, particularly when detected alongside other characteristic impurities, is generally interpreted as a specific indicator of illicit heroin use rather than legitimate therapeutic opioid intake [65]. Similar to 6-MAM, 6-AC can be detected in urine for approximately 8 h, with codeine as its principal metabolite. However, numerous studies have shown that 6-AC is a less robust and less reliable marker of heroin use compared to 6-MAM, due to its lower peak concentrations and short half-life (~237 min, yielding a diagnostic “window” of ~8 h). As a result, there is a high likelihood that biological samples may test negative for 6-AC despite the presence of 6-MAM. For this reason, 6-AC does not yet have practical value as a primary biomarker, serving instead as supplementary evidence of heroin exposure [66].

Consumption of poppy seed-containing foods can elevate urinary opioid levels above 300 ng/mL—the standard positive threshold for immunoassay-based screening still employed in some laboratories [42,63]. In forensic practice, this phenomenon has been invoked in the so-called “poppy seed defense”, which has led to acquittals in cases of alleged opioid misuse and subsequently motivated the adoption of a higher positive screening cut-off of 2000 ng/mL. In a recent study, Reisfield et al. (2023) highlighted that accurate differentiation between individuals using opioids and those exposed through dietary intake requires consideration of several factors: the specific food product, portion size, pattern of consumption, the time elapsed between ingestion and urine collection, and, when possible, analysis of the particular seed batch consumed [67]. In this context, an official 2024 publication by the U.S. Department of Defense noted that the military’s drug testing program has raised the codeine cut-off to reduce false-positive results among service members. Additionally, the program has introduced a reflex screening test for the opiate thebaine, a minor alkaloid derived from the poppy plant, which can serve as a urinary biomarker of poppy seed consumption. In the pharmaceutical industry, thebaine is employed as a precursor in the synthesis of oxycodone, oxymorphone, naloxone, and buprenorphine [68,69]. It is not available as a therapeutic product and is found only in trace amounts in street heroin—if at all—because it is typically converted into acetylated derivatives alongside morphine [47]. Consequently, some authorities classify urine samples containing 4000–10,000 ng/mL of codeine as negative for opioid misuse, provided that thebaine is also detected at concentrations of ≥ 5 ng/mL, reflecting dietary exposure rather than illicit use [70].

In recent years, attention has focused on the acetylated metabolite of thebaine-4-glucuronide, which is formed during the illicit synthesis of heroin, when thebaine from opium undergoes acetylation and chemical restructuring. Paradoxically, the presence of this thebaine metabolite serves as a forensic indicator of street heroin use, as it is not observed following consumption of poppy seeds or pharmaceutical opioids. It is excreted in the urine and results from the glucuronidation of acetylated thebaine derivatives generated during illicit heroin production. This metabolite is increasingly recognized for its diagnostic value as a forensic biomarker in modern toxicology laboratories [71]. Another potential marker is oripavine, produced via O-demethylation of thebaine [72]. Since thebaine is destroyed during acetylation in heroin synthesis, neither thebaine nor oripavine is expected after consumption of street heroin or pharmaceutical phenanthrene-based morphinomimetics [55]. Therefore, the detection of thebaine and/or oripavine alongside morphine in urine indicates opium or poppy seed intake, though it does not exclude concurrent use of other opioids [73].

According to Maas et al. (2018) noscapine and papaverine are not detectable in urine following the consumption of poppy-derived products containing up to 94 µg of noscapine and 3.3 µg of papaverine [47]. However, desmethylpapaverine and its glucuronide can be detected for up to 48 h post-ingestion [74]. Consequently, these compounds may serve as potential biomarkers of poppy consumption, provided that the possibility of their origin from pharmaceutical products is excluded [63]. Reticuline, a precursor of opium alkaloids, is absent in both heroin and poppy seeds, being present exclusively in opium. Therefore, it has been proposed as a biomarker to differentiate opium use from dietary poppy exposure, as well as to distinguish opium intake from pharmaceutical codeine use [63,75].

Considering the summarized advances in the detection of primary and secondary biomarkers of heroin use, particularly intriguing are efforts to implement comprehensive multi-biomarker analyses in biological specimens. A notable example is the GC-MS method developed by Karakasi et al. (2024), which allows simultaneous determination of five potential heroin biomarkers (meconin, thebaine, papaverine, acetylcodeine, and noscapine), together with the classical opioids morphine, codeine, and 6-MAM, in a variety of biological matrices, including blood, urine, vitreous humor, and bile, from heroin users [51]. This approach aims to provide a more in-depth characterization of heroin exposure, particularly in cases where direct evidence of heroin use is sought. The authors concluded that meconin, primarily, and papaverine, secondarily, could serve as indirect biomarkers of heroin use in biological materials, especially in scenarios where 6-MAM has already been metabolized and is no longer detectable [51]. Using a similar analytical strategy, Al-Asmari et al. emphasized that in postmortem biomarking of heroin, the determination of free morphine in solid tissues is more reliable and informative. In particular, the gastric wall shows a higher frequency of 6-MAM detection compared to other tissues, highlighting the utility of alternative matrices in cases where blood samples are unavailable [76].

3.2. Oxycodone/Oxymorphone/Hydrocodone/Hydromorphone

Oxycodone is well absorbed following oral administration and exhibits a relatively rapid onset of action. Its duration of effect ranges from 4 to 12 h, depending on the formulation. Oxycodone undergoes metabolism via N- and O-demethylation, resulting in the formation of the active metabolite oxymorphone, which is also available as a therapeutic agent for pain management. The majority of the administered dose is excreted in urine as free oxycodone and noroxycodone (with moderate activity), as well as conjugated oxycodone and oxymorphone [28]. Significant interindividual variability in metabolism arises from genetic polymorphisms [46]. Both oxycodone and oxymorphone demonstrate low cross-reactivity with standard opioid immunoassays, and therefore are often undetectable through routine opioid screening tests [29]. Specific immunoassays have been developed for oxycodone due to its high potential for abuse [45]. Hydrocodone is structurally similar to oxycodone. At lower doses, it is used as an antitussive, while at higher doses it is prescribed as an analgesic. Its duration of action ranges from 4 to 6 h, and it is approximately six times more potent than codeine. Like oxycodone, hydrocodone undergoes N- and O-demethylation, producing hydromorphone, an active metabolite approximately 8.5 times more potent than morphine, as well as dihydrocodeine via reduction in the ketone group [28].

Although hydromorphone is a minor metabolite of morphine, oxymorphone is not a metabolite of either morphine or hydromorphone. Therefore, the presence of oxymorphone in the absence of a valid prescription is a clear indicator of opioid misuse. Hydrocodone can also arise as a minor metabolite of morphine and may constitute up to 11% of the codeine concentration. Consequently, the detection of small amounts of hydrocodone in urine with high codeine levels should not be interpreted as evidence of hydrocodone misuse [38]. Most routine opioid immunoassays exhibit weak cross-reactivity with oxycodone and relative cross-reactivity with hydromorphone and hydrocodone. At high urinary concentrations, however, these compounds may still yield positive results, justifying the development of specific immunoassays for oxycodone due to its widespread abuse [45]. Overall, keto-opioids undergo extensive conjugation, necessitating hydrolysis and derivatization for accurate quantitative analysis [28,45].

3.3. Methadone

Methadone is primarily employed for maintenance treatment of opioid dependence, but it can also be used for pain management. It is widely available as a racemic mixture, although the (R)-enantiomer exhibits a tenfold higher affinity for μ- and δ-opioid receptors. Methadone is particularly effective for managing withdrawal symptoms due to its high oral bioavailability, long elimination half-life (up to 55 h), low severity of withdrawal upon discontinuation, and the availability of specific antagonists for overdose management [28]. The opioid is metabolized mainly in the liver via cytochrome P450 enzymes, predominantly CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, CYP2D6, as well as in the intestines. In approximately 10% of Caucasians, who are slow metabolizers with low CYP2D6 activity, the elimination half-life may be prolonged. Methadone and its primary metabolite, EDDP, are excreted in urine. Concomitantly, 2-ethyl-5-methyl-3,3-diphenylpyrrolidine (EDMP) is also formed, although it is quantitatively less significant (Figure 2) [77]. Measurement of both the parent drug and EDDP can be used to assess prolonged exposure, aiding in the differentiation of chronic therapeutic use from single or incidental exposure [78,79,80]. In clinical practice, it is important to measure both compounds because methadone excretion varies considerably depending on dose, metabolism, and urinary pH, whereas urinary EDDP levels are pH-independent and therefore preferred for monitoring treatment adherence [29,77].

Figure 2.

Methadone metabolism and main metabolites.

Commercially available urinary immunoassays for methadone screening utilize antibodies targeting either methadone or EDDP. Typically, standard opioid immunoassays do not detect methadone or its metabolites, and methadone-specific assays may not detect EDDP and vice versa. However, immunoassays designed for methadone often exhibit low cross-reactivity with EDDP, necessitating confirmatory testing [45]. Additionally, the opioid analgesic tapentadol has been reported, albeit rarely, to cross-react with certain methadone immunoassays, potentially producing false-positive results, further highlighting the need for confirmatory analysis [42,81].

Another approach to distinguish the nature of methadone use is chiral analysis. Enantiomeric ratios of methadone and its metabolite EDDP can differentiate therapeutic from illicit use. For patients receiving racemic methadone therapy, the ratio is approximately 1:1, whereas therapy with pure R-methadone (available in some countries) lacks the S-enantiomer. Atypical enantiomeric profiles, inconsistent with approved formulations in a given jurisdiction, suggest illicit origin. Additionally, comparison of methadone and EDDP levels can indicate whether the drug has been metabolized in vivo or deliberately added to adulterate a sample [82,83,84]. Cases have been documented where patients intentionally fail to comply with prescribed opioid therapy for dependence treatment or pain management, sometimes diverting their medications to the illicit market. Routine drug screening is often a requirement for participation in such treatment programs to monitor compliance. To circumvent testing, some individuals employ the so-called “pill shaving” technique, which involves crushing or scraping opioid tablets (e.g., with a razor) into biological specimens to artificially generate a positive result during toxicological analysis [85,86]. Such attempts can be detected by comparing the relative amounts of parent methadone and EDDP. In cases of compromised adherence, the EDDP-to-methadone ratio is markedly low, sometimes below 0.09, revealing manipulation of the sample [29,87,88].

3.4. Fentanyl

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid with a molecular structure distinct from that of morphine. First approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the late 1960s, it is currently employed in pain management and anesthesia. However, the illicit use of fentanyl and its analogs has significantly intensified the opioid crisis in recent years, contributing to a sharp increase in overdose-related fatalities. Despite international regulatory efforts, fentanyl’s extreme potency and low production cost have facilitated widespread dissemination, including via counterfeit formulations. Although naloxone remains the primary antidote, its limited efficacy highlights the urgent need for more potent and long-acting therapeutic interventions. Additional risk factors, such as polypharmacy, prescription misuse, environmental exposure, and potential weaponization, further exacerbate public health challenges [89,90]. In this regard, analytical methodologies capable of distinguishing illicit from medically prescribed fentanyl use have become increasingly critical. A further concern is the emergence of novel fentanyl analogs on the illicit market. Many of these analogs are significantly more potent than fentanyl itself and are present at much lower doses, complicating their detection in blood and urine. This underscores the urgent need for accessible and reliable testing of these substances in both biological specimens and seized drugs [28].

Immunoassays for fentanyl in urine are available; however, their use is largely restricted to laboratories with appropriate licensure. Immunoassays have also been developed for alternative matrices, including oral fluid, blood, and meconium, but these are not widely accessible. Point-of-care tests, such as lateral flow immunoassays and fentanyl test strips, are more broadly available, yet their lower specificity limits clinical utility [91,92,93]. All immunoassays are susceptible to false-positive and false-negative results and vary in their ability to detect fentanyl analogs (e.g., carfentanil, acetylfentanyl, furanylfentanyl, etc.) and other novel synthetic opioids (NSOs) (e.g., U-47700, AH-7921, etc.) [91,94,95]. Confirmatory analysis is typically performed using mass spectrometry, which enables accurate and reliable detection of fentanyl and its primary metabolite, norfentanyl, in urine and oral fluid (Figure 3). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)–MS/MS is the most widely employed method, offering exceptional specificity and sensitivity for fentanyl, norfentanyl, and various fentanyl analogs and NSOs [42,96,97,98,99].

Figure 3.

Main metabolic pathway of fentanyl leading to norfentanyl.

In conclusion, it is important to recognize that certain medications, including over-the-counter products, can induce false-positive results in opioid immunoassays. For example, naloxone and its glucuronide metabolite may cross-react with antibodies in some CEDIA immunoassays at high concentrations. False-positive results for methadone have also been documented following administration of quetiapine and diphenhydramine [100,101]. Additionally, antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones (e.g., levofloxacin, ofloxacin, pefloxacin) and rifampicin may exhibit cross-reactivity in some opioid immunoassays [102]. These observations underscore the continued necessity of confirmatory analysis via chromatography to definitively rule out false-positive results [46]. Furthermore, assessing acceptable ranges for temperature, pH, creatinine concentration, and specific gravity of urine is essential for identifying adulterated, substituted, or diluted specimens [39,103]. Ultimately, all urine drug testing results must be interpreted in the context of the analytical method, prescribed medications, specimen type, time since last dose, specimen collection, specimen validity tests, and patient-specific factors. Unexpected or unexplained results should prompt discussion between the patient and laboratory, and additional confirmatory testing should be performed as needed to ensure accurate interpretation [37]. Table 2 summarizes key pharmacokinetic characteristics, analytical biomarkers, detection matrices, regulatory cut-off limits, and major analytical challenges associated with selected opioids [13,28,39,42,103,104,105].

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic characteristics, analytical biomarkers, detection matrices, regulatory cut-off limits, and major analytical challenges of selected opioids.

4. Amphetamine-Type Stimulants

Amphetamine is the prototype of a broader class of compounds sharing a phenethylamine scaffold, collectively referred to as amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS). Small structural modifications, including substitution on the phenyl ring, α-methylation, β-ketone incorporation, or alteration of the amino group, generate a wide spectrum of ATS derivatives with diverse pharmacological profiles, ranging from classical stimulants to entactogens, hallucinogens, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors [106]. The group includes amphetamine, methamphetamine, and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), as well as synthetic cathinones such as mephedrone, methylone, and methcathinone [107,108].

Although these substances share a common structural backbone, they differ markedly in potency, pharmacokinetics, and clinical as well as toxicological effects. Several ATS were initially developed as pharmaceutical treatments for conditions such as narcolepsy, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or as appetite suppressants. Today, legitimate medical use is mainly restricted to ADHD and narcolepsy. Amphetamine and mixed amphetamine salts are marketed as Adderall®, while methamphetamine hydrochloride is available as Desoxyn® in select cases of severe ADHD or obesity. Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse®) is a prodrug that exclusively releases D-amphetamine, thereby reducing the risk of misuse compared to immediate-release formulations [108,109]. These pharmaceutical formulations are effective when used as prescribed, but they also pose a risk of diversion and abuse. Their strong psychostimulant and euphoric properties, in particular, have contributed to widespread nonmedical use [107,109].

Pharmacologically, ATS primarily target monoaminergic pathways. Acting as substrates for dopamine (DAT), norepinephrine (NET), and serotonin (SERT) transporters, and disrupting vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), they promote monoamine release and inhibit reuptake, thereby elevating extracellular neurotransmitter levels [110,111]. Therapeutically, such actions are beneficial for improving alertness and attention, but chronic or supratherapeutic exposure is linked to acute toxicity, neurotoxicity, tolerance, dependence, and psychosis [112,113]. Reflecting growing psychosocial impact, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders introduced Stimulant Use Disorder (StUD) [18]. This condition is characterized by compulsive consumption of amphetamines and related compounds, resulting in clinically significant distress or impairment. Clinical hallmarks include craving, tolerance, and increased risk of psychiatric and somatic complications, such as anxiety, psychosis, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive impairment [114]. Unlike opioid withdrawal, cessation of ATS is generally non-lethal, yet commonly associated with dysphoria, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and elevated relapse risk [115].

Epidemiologically, ATS are the second most commonly used illicit drug class after cannabis, with highest prevalence in East and Southeast Asia, Australia, North America, and parts of Europe. Methamphetamine-related harms, including overdose fatalities, psychotic episodes, and violent behavior, are sharply increasing worldwide. Notably, beyond psychiatric and somatic harms, ATS, particularly methamphetamine and MDMA, have also been implicated in drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA) due to their ability to induce disinhibition, hypersexuality, and impaired judgment. This forensic dimension underscores their dual role as drugs of abuse and potential tools in sexual crimes [116,117]. Polysubstance use with opioids contributes to the ongoing “fourth wave” of the opioid crisis [107,118].

The ATS most frequently misused include amphetamine, methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), and synthetic cathinones such as mephedrone and methylone [107]. Patterns of nonmedical use vary, with the preferred routes of administration being oral and intranasal, followed by smoking or intravenous injection in the case of methamphetamine, which is associated with particularly severe health risks [114].

Currently, therapeutic interventions specifically approved for ATS use disorder remain limited. Management is based primarily on psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and contingency management, with no pharmacological agent yet demonstrating consistent efficacy [118]. Despite intensive research, candidate medications such as bupropion, mirtazapine, and modafinil have shown only mixed or modest results [119].

In parallel, the modes of ATS acquisition represent a major challenge, encompassing large-scale illicit production and trafficking, diversion of pharmaceutical preparations, and increasingly, internet-based markets. These supply channels contribute substantially to the persistence and expansion of ATS use worldwide [107,120,121]. Diversion of prescription stimulants for nonmedical use is also a growing concern, particularly in high-income countries [122]. Documented cases describe the extraction and misuse of active compounds from pharmaceutical preparations, such as crushing and intranasal administration of Adderall® tablets or chemical isolation of methamphetamine from Desoxyn®. These practices not only enhance rapid onset of psychoactive effects but also increase the risk of overdose and rapid dependence development [123]. In summary, ATS represent a dual-edged phenomenon: indispensable in selected medical contexts yet carrying immense risks of diversion, dependence, and severe societal harms.

Collectively, these findings underscore a dual challenge: the continued global availability of ATS through illicit and diverted channels, and the lack of effective pharmacological therapies. Addressing this issue will require comprehensive strategies that combine improved biomonitoring of stimulant use with strengthened control of illicit manufacturing and pharmaceutical diversion [118,119].

In modern clinical and regulatory practice, the toxicochemical analysis of amphetamines has evolved far beyond its original role in forensic and toxicology laboratories. Today, ATS testing is applied in diverse settings including occupational health, military medicine, and sports, where analytical results directly influence both medical management and regulatory compliance [124,125]. Within psychiatry and addiction medicine, routine urine and hair testing has become central to monitoring therapeutic adherence, detecting relapse, and identifying unprescribed stimulant use [46,126]. At the population level, incorporation of ATS biomarkers into wastewater-based epidemiology has enabled near real-time surveillance of consumption trends, providing valuable insight into community-level stimulant use. In particular, the detection of non-physiological by-products such as paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA) or paramethoxymethamphetamine (PMMA), together with chiral analysis differentiating enantiomerically pure pharmaceutical formulations from racemic illicit preparations, represents a forensic “gold standard” for discriminating legitimate therapeutic exposure from illicit ATS use [127,128,129]. Taken together, these advances highlight the urgent need for validated methodologies capable of distinguishing medically indicated stimulant therapy from illicit or nonmedical consumption. Overall, advances in analytical mothodologies ensure more reliable differentiation between therapeutic and illicit use of ATS, thereby strengthening clinical decision-making and enhancing forensic validity. Beyond urine, other biological matrices offer complementary analytical value as oral fluid enables near real-time detection and is minimally affected by urinary pH. Hair testing provides retrospective monitoring over extended periods and is particularly useful in compliance assessment and forensic investigations whereas plasma and serum are primarily applied in cases of acute intoxication or for medicolegal reconstruction [124,125,126]. An overview of the recommended interpretive workflow for ATS testing, from initial screening to forensic attribution, is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Simplified analytical workflow for distinguishing therapeutic from illicit ATS use.

Selected parent/metabolite ratios (e.g., amphetamine/methamphetamine) help infer recency of use and source attribution when interpreted alongside urine pH, dose, and clinical context [113,130]. For 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, the ratio of the parent compound to its metabolite 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine is used as a temporal marker: a high MDMA/MDA ratio suggests recent ingestion, whereas a decreasing ratio reflects ongoing biotransformation. Because O-demethylenation is CYP2D6-dependent, pharmacogenetic variability and co-medication with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can delay MDA formation and complicate interpretation. Therefore, ratio-based inference should always be contextualized with patient factors and, when clinically or forensically relevant, confirmed by LC-MS/MS [130,131].

In most clinical and regulatory contexts, initial drug detection continues to rely on immunoassays targeting parent compounds or primary metabolites. While these assays are widely accessible and offer rapid results, they are prone to cross-reactivity with structurally related substances, potentially leading to false-positive outcomes. Therefore, any discordant or clinically significant findings should be verified using chromatographic techniques coupled with mass spectrometry. High-resolution LC-MS/MS now enables broad, simultaneous coverage of many stimulants of this class and their metabolites across matrices [46,131]. Specimen validity assessment is essential and includes creatinine concentration, specific gravity, urinary pH, and screening for oxidizing adulterants. As discussed in the pharmacokinetics section, urinary pH markedly affects amphetamine excretion and MA/AM ratios, and should therefore be considered in interpretation. Any suspicion of adulteration should prompt recollection and targeted LC-MS/MS confirmation [46,131]. Individuals attempting to evade detection often resort to urine dilution, ingestion of masking agents or oxidizing adulterants, or even substitution with drug-free samples. In response, laboratories apply specimen validity testing, including creatinine concentration, specific gravity, and oxidant checks, to identify tampering. These safeguards are essential to maintain the integrity of ATS screening in both clinical and forensic settings [132]. In routine practice, bupropion and its metabolites are among the most common causes of apparent “amphetamine” reactivity, and aripiprazole has produced positive screens in children and adolescents, both examples underline the need to confirm before drawing conclusions [133].

Recent metabolomics studies of amphetamine-type stimulants, including methamphetamine and its analogues, employ nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) and LC-MS in untargeted metabolomic profiling, coupled with supervised machine-learning algorithms such as random forest, support vector machines, and artificial neural networks. These approaches identify metabolic pathway perturbations associated with different phases of use or withdrawal and generate biomarker panels that can predict exposure history and time-since-use. The combination of metabolomics and machine learning thus provides both mechanistic insight and potential forensic applications [134].

4.1. Screening and Cross-Reactivity in Clinical and Forensic Settings

Screening in clinical and workplace settings typically uses amphetamine-calibrated immunoassays with thresholds of 500 to 1000 ng/mL expressed as amphetamine equivalents, although United States federal programs use 500 ng/mL for screening and 250 ng/mL for confirmation [46,132]. In Europe, the European Workplace Drug Testing Society (EWDTS) recommends a screening cut-off of 500 ng/mL and confirmation at 250 ng/mL for amphetamine-class stimulants, harmonizing with but not identical to U.S. SAMHSA guidelines [135]. Cross-reactivity is clinically significant, with common interfering substances including bupropion, which is frequently encountered in emergency and outpatient settings, and aripiprazole, particularly relevant in pediatric and adolescent toxicological screens. Additional interferents include pseudoephedrine, phentermine, atomoxetine, metoprolol, the labetalol metabolite 1-methyl-3-phenylpropylamine, and fluoroquinolone antibiotics such as ofloxacin and moxifloxacin [134,136,137]. Discordant or consequential results should be confirmed by gas or liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry to ensure analytical specificity [46,138]. Clinical pearls for ATS testing include several interpretive caveats of practical relevance. Apparent “amphetamine” positivity due to cross-reactants such as bupropion or aripiprazole should always be confirmed by LC-MS/MS before clinical or forensic conclusions are drawn. Conversely, a negative amphetamine-class screen in the setting of suspected MDMA or MDEA use necessitates a targeted LC-MS/MS panel to avoid false reassurance. Finally, detection of a predominant L-methamphetamine enantiomer, particularly when the methamphetamine/amphetamine ratio appears atypical, should raise suspicion for selegiline therapy or over-the-counter decongestant exposure [134]. A summary of common cut-off values, interfering substances, and interpretive caveats is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cut-off values, common cross-reactants, and examples of false positives in ATS immunoassays.

4.2. Metabolic Overview of Amphetamine—Type Stimulants

Across ATS, hepatic Phase I reactions like oxidative deamination, ring and side-chain hydroxylation, and N- or O-dealkylation, occur predominantly via CYP2D6 with contributions from CYP1A2 and CYP3A4, and are followed by Phase II conjugation, mainly glucuronidation and sulfation. Methamphetamine undergoes CYP2D6 mediated N-demethylation to amphetamine, creating intrinsic overlap between parent and metabolite. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine is O-demethylenated to 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine and further hydroxylated to HMMA before conjugation. Interindividual CYP2D6 variability and co-medication may modulate these patterns. The N-ethyl analogue MDEA yields DHEA and HMEA, with minor N-deethylation to MDA; detection of HMEA supports recent MDEA exposure. By contrast, finding PMA or PMMA reflects non-standard synthesis or adulteration rather than endogenous metabolism and has specific forensic value. These overlapping pathways account for cross-detection between parent compounds and metabolites and necessitate that ratio-based findings, supplemented where appropriate by chiral data, be interpreted in clinical context and confirmed by mass spectrometry [114,130,131,140,141,142]. The pharmacokinetic characteristics of the main amphetamine-type stimulants are summarized in Table 4 [109,110,114,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155].

Table 4.

Clinically and illicitly used amphetamine-type stimulants: main representatives.

4.3. Methamphetamine: Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism

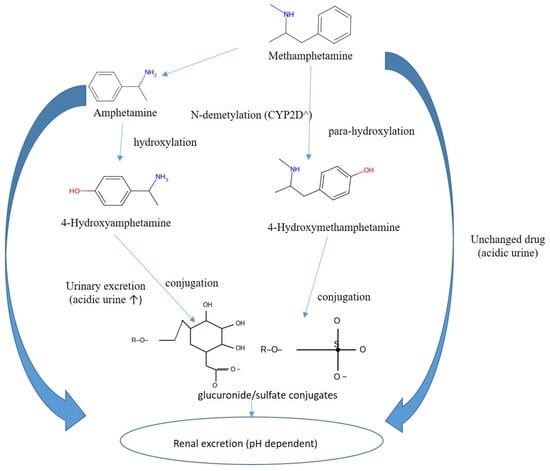

Methamphetamine is efficiently absorbed by oral, intranasal, or intravenous routes, readily penetrates the central nervous system, and typically has a longer duration of action than amphetamine. Biotransformation is dominated by CYP2D6 mediated N-demethylation to amphetamine, with additional para-hydroxylation to 4-hydroxymethamphetamine and 4-hydroxyamphetamine followed by conjugation. Renal elimination is strongly pH-dependent: acidic urine markedly increases excretion of unchanged drug, whereas alkaline urine reduces clearance. For reporting and interpretation, urinary pH should be documented; acidic urine increases the renal elimination of unchanged amphetamine and methamphetamine, whereas alkaline urine reduces it and can inflate MA/AM ratios. For timing and source attribution, the urinary AM/MA ratio generally rises with time after exposure and should be interpreted with urine pH, dose, and clinical context, when attribution remains uncertain, enantioselective testing can distinguish therapeutic or over-the-counter L-methamphetamine exposure from illicit or prescription D-methamphetamine sources [114,130,139]. A simplified scheme of methamphetamine metabolism is shown in Figure 5, while key interpretive considerations regarding methamphetamine versus amphetamine intake are summarized in Table 5.

Figure 5.

Overview of methamphetamine metabolism to amphetamine and hydroxy-metabolites with subsequent conjugation.

Table 5.

Parent/metabolite ratios (methamphetamine/amphetamine), influence of urine pH, forensic notes *.

Key interpretive considerations include high methamphetamine with moderate amphetamine (MA/AM >2–3 in early hours) is consistent with methamphetamine intake. Conversely, high amphetamine with little or no methamphetamine suggests primary amphetamine use or a late collection window. Urinary pH also modifies these ratios: alkalinization prolongs MA half-life and raises ratios, whereas acidification accelerates clearance. When attribution remains uncertain, chiral (D/L) analysis is recommended [114,130]. Thus, methamphetamine interpretation requires careful integration of pharmacokinetics, urine pH, and enantiomeric profiling to avoid misclassification of use.

4.4. MDMA and MDA: Parent-Metabolite Relationships

For 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, the relation between the parent drug and 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine informs recency: higher MDMA/MDA ratio suggests recent ingestion, whereas a rising MDA/MDMA ratio reflects ongoing biotransformation. Given the CYP2D6-dependent O-demethylenation and frequent co-medication with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, ratio-based inference should account for pharmacogenetics and drug–drug interactions and be confirmed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry when results are consequential [131,144]. Taken together, parent-metabolite ratios provide valuable timing information but require confirmatory testing to ensure accurate attribution of MDMA versus MDA intake. An overview of MDMA, its metabolites, and their interpretive significance is provided in Table 6.

Table 6.

Parent drug MDMA and related metabolites: interpretive value for acute vs. late use and polydrug exposure.

4.5. MDEA: Metabolic Pathways and Biomarkers

3,4-Methylenedioxyethylamphetamine is the N-ethyl analogue of MDMA. In humans it undergoes O-demethylenation to 3,4-dihydroxyethylamphetamine (DHEA), followed by O-methylation to 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyethylamphetamine (HMEA) and conjugation; a minor N-deethylation pathway yields MDA. Detection of HMEA in urine or blood supports recent MDEA exposure and complements MDMA: MDA-based timing. Confirmation by targeted liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry is recommended when source attribution is disputed [140,142]. Therefore, MDEA biomarkers, though informative, must always be interpreted in a broader metabolic and analytical context.

4.6. Synthetic Impurities and Adulterants of ATS

Detection of paramethoxyamphetamine or paramethoxymethamphetamine indicates non-standard synthesis or adulteration rather than endogenous metabolism and carries specific forensic and toxicological significance. In practice, simultaneous detection of PMA/PMMA, together with a D-enantiomeric predominance and atypical parent/metabolite ratios, provides compelling forensic evidence of illicit manufacture and is used in judicial and disciplinary investigations [141].

4.7. Synthetic Cathinones: Analytical and Toxicological Considerations

Routine immunoassays calibrated for amphetamines exhibit limited cross-reactivity with synthetic cathinones, often resulting in false-negative findings. Therefore, reliable detection and differentiation necessitate the use of targeted LC-MS/MS panels or, optimally, high-resolution mass spectrometry. Notably, since synthetic cathinones lack approved therapeutic indications, their identification unequivocally indicates illicit or designer-drug use, underscoring the critical importance of confirmatory mass spectrometric analysis for accurate forensic and clinical interpretation [149]. In practice, detection of synthetic cathinones is a direct marker of illicit exposure, making robust analytical confirmation crucial for both forensic and medical evaluations. Representative synthetic and natural cathinones with their main metabolites and analytical challenges are listed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Representative synthetic and natural cathinones: major metabolites and analytical challenges.

4.8. Chiral (Enantiomeric) Analysis for Source Attribution

When patient history and initial screening results are inconsistent, chiral analysis provides decisive clarification. A predominance of the L-enantiomer of methamphetamine supports exposure from selegiline metabolism or inhaled decongestants, whereas enrichment of the D-enantiomer indicates illicit use or prescription D-methamphetamine. Lisdexamfetamine yields only D-amphetamine in vivo, so detection of D-amphetamine alone supports therapeutic adherence. Chiral findings should be interpreted together with the time dependent AM/MA ratio and urine pH [46,138]. Ultimately, enantiomeric profiling serves as a decisive tool for distinguishing legitimate medical therapy from recreational or illicit ATS use. Practical interpretive clues from enantiomeric analysis are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Enantiomeric clues for ATS source attribution.

In conclusion, the interpretation of amphetamine-type stimulant biomarkers requires a multidimensional approach that integrates broad screening with confirmatory mass spectrometry. Parent-metabolite ratios, chiral (enantiomeric) profiles, and impurity markers provide complementary layers of information, but their clinical value emerges only when considered alongside pharmacokinetic factors, urine pH, dosing context, and patient history. Ultimately, refining these analytical strategies is not only essential for forensic accuracy but also for improving clinical management, tailoring therapeutic monitoring, and guiding public health responses to the rising global burden of ATS misuse. Aligning such approaches with those already established for other controlled substances, such as opioids, will further strengthen diagnostic accuracy and enhance both therapeutic and public health outcomes. Future perspectives should focus on standardizing cut-off values, validating novel biomarkers, and further integrating metabolite-based strategies into clinical and forensic practice.

5. Benzodiazepines and Z-Drugs

Benzodiazepines are a class of psychoactive drugs that were originally introduced for therapeutic purposes in the mid-20th century. Since then, benzodiazepines have been widely used for their sedative-hypnotic, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant properties [156,157]. They act as positive allosteric modulators at the γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor. The endogenous ligand for this receptor is γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS). Benzodiazepines enhance the affinity of GABA for its receptor, increasing chloride ion influx and promoting neuronal hyperpolarization, thereby leading to a general CNS depressant effect [157]. Clinically, they are commonly prescribed for the acute management of anxiety disorders, insomnia, alcohol withdrawal, status epilepticus, and as premedication for medical or surgical procedures [156,158]. Benzodiazepines have a relatively high therapeutic index, particularly when compared to older barbiturates, contributed to their widespread adoption in medical practice [159,160]. However, the long-term use of benzodiazepines is constrained by the potential for tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal phenomena [158,160,161]. Chronic administration leads to neuroadaptive changes at the GABAA receptor complex, diminishing therapeutic efficacy and predisposing individuals to withdrawal symptoms upon abrupt cessation. These symptoms can range from rebound anxiety and insomnia to more severe manifestations such as seizures and psychosis [161]. Moreover, benzodiazepines possess a significant potential for misuse, especially when used in conjunction with other CNS depressants such as opioids or alcohol, which can potentiate respiratory depression and increase overdose risk [158,162].

Z-drugs, including zolpidem, zopiclone, and zaleplon, are non-benzodiazepine hypnotics primarily prescribed for short-term treatment of insomnia [163,164]. They act selectively on the benzodiazepine binding site of the GABAA receptor, producing sedative-hypnotic effects with minimal anxiolytic or muscle-relaxant activity compared to classical benzodiazepines [163,165]. Although initially considered safer alternatives due to lower risk of dependence, accumulating evidence indicates that Z-drugs can still lead to tolerance, withdrawal, and misuse, particularly in patients with a history of substance use disorders [164,166]. Adverse events such as cognitive impairment, falls, and complex sleep-related behaviors have also been reported, especially among elderly populations [165,166].

From a public health perspective, the non-medical use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs has become an increasing concern, often associated with polydrug abuse and adverse outcomes as well as an implication in drug-facilitated crimes [160,162]. Therefore, current prescribing guidelines advocate for the lowest effective dose over the shortest duration possible, along with regular monitoring of efficacy and safety as well as periodic reassessment of ongoing need [161,163,164]. In addition to the abuse potential of benzodiazepines, they are well-known for their use in DFSA [167].

Therefore, despite benzodiazepines remain an important pharmacological tool in acute settings, their risk-benefit ratio necessitates careful patient selection and monitoring to mitigate the likelihood of misuse [160,161]. In this regard, data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health from the United States indicated that nearly 17.7% of all individuals who used benzodiazepines and 9.2% of those who took Z-drugs reported misuse within the past year [168]. Data from European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA) indicate that benzodiazepines are frequently implicated in drug-induced deaths across Europe, especially in drug users who also take opioids and other central nervous system depressants. Moreover, designer benzodiazepines such as etizolam have become an increasing public health and forensic toxicology concern due to their growing availability through illicit online markets and the absence of pharmaceutical regulation. They often exhibit high potency, rapid onset, and unpredictable pharmacokinetics, leading to a high risk of overdose and dependence. Their metabolism is poorly characterized compared to traditional benzodiazepines, with recent metabolomic studies identifying numerous phase I and phase II metabolites. This metabolic diversity complicates toxicological interpretation and detection, as parent compounds are often absent in biological samples, while metabolites lack validated reference standards [169,170].

Benzodiazepines encompass a range of compounds and are characterized with varying pharmacokinetic profiles, including differences in onset and duration of action as well as metabolic pathways which impact their clinical use [156,159]. The main clinically used benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are listed in Table 9 along with their pharmacokinetic properties and major metabolites.

Table 9.

The main clinically used benzodiazepines and Z-drugs [171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198].

5.1. Toxicological Analysis of Benzodiazepines and Z-Drugs

Several methods for laboratory detection of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are available. A traditional method is the immunoassay-based analysis, which targets either the parent compound or common metabolites [171,199]. Although these assays are widely accessible and cost-effective, they exhibit variable sensitivity and a considerable risk of cross-reactivity among structurally similar benzodiazepines, leading to potential false positives or negatives [167]. To overcome these limitations, confirmatory analytical methods such as GC–MS and LC–MS/MS are employed as the gold standard for definitive identification and quantification [176,200]. These chromatographic techniques provide superior specificity, sensitivity, and quantitative accuracy, enabling simultaneous detection of multiple benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and their metabolites in complex biological matrices such as plasma, urine, hair, and oral fluid. Recent advances include HRMS and targeted metabolomic profiling, which have markedly improved the discrimination between therapeutic use and misuse through detailed metabolic signatures [171,201].

Recent advances in analytical toxicology are microsampling, particularly dried blood spot (DBS) and volumetric absorptive microsampling (VAMS) techniques, which offer minimally invasive, stable, and logistically convenient alternatives for assessing plasma-equivalent concentrations of both parent drugs and metabolites [202]. These approaches facilitate therapeutic drug monitoring and forensic assessment even in resource-limited or field conditions, without compromising analytical accuracy. Furthermore, hair segmental analysis has gained traction for its ability to provide a retrospective timeline of drug consumption over weeks or months, offering insights into long-term use or accidental intake [203,204]. Recent data emphasizes systematic metabolic characterization using LC-HRMS combined with computational metabolomics and machine-learning-assisted spectral annotation for benzodiazepines’ analysis, particularly for emerging designer or novel benzodiazepines. These approaches facilitate identification of unexpected or low-abundance metabolites and are critical when authentic analytical standards are unavailable. Current reviews highlight the integration of in silico metabolic prediction tools (for example, BioTransformer or GLORYx) with experimental mass-spectrometric data to rapidly expand forensic toxicology panels [205].

Plasma and serum remain the major biological matrices for assessing recent use and pharmacokinetic parameters as they closely reflect the pharmacologically active fraction of the drug. However, due to short detection windows from typically a few hours to days, these matrices may not reliably differentiate between therapeutic use and sporadic misuse, particularly for short-acting agents such as midazolam or zolpidem [206,207]. In contrast, urine testing offers broader detection windows and is ideal for screening and compliance monitoring as it captures both parent compounds and conjugated metabolites. Reported confirmatory cut-offs for benzodiazepines and Z-drugs depend on matrix and method. Additionally, interpretive challenges arise because urinary concentrations are influenced by hydration status, metabolism, and renal clearance, making parent/metabolite ratios less consistent across individuals [46,208]. Hair analysis provides a unique retrospective timeline, allowing assessment of chronic versus isolated use over several weeks or months [209]. Saliva testing has recently gained interest as a non-invasive alternative that reflects the unbound, pharmacologically active fraction of benzodiazepines. Yet, the typically low drug concentrations and lipophilic nature of many benzodiazepines limit sensitivity and quantification reliability [210]. Finally, multi-matrix strategies, combining plasma or urine with hair or oral fluid, provide complementary insights, improving the ability to discriminate legitimate medical exposure from illicit or non-compliant use [211]. Table 10 summarize the available information about appropriate matrices, detection method and typical confirmatory cut-off values for major benzodiazepines and Z-drugs [170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211].

Table 10.

Analytical biomarkers, detection matrices and methods and regulatory cut-off limits for selected benzodiazepines and Z-drugs.

5.2. Interpretation of Analytical Findings

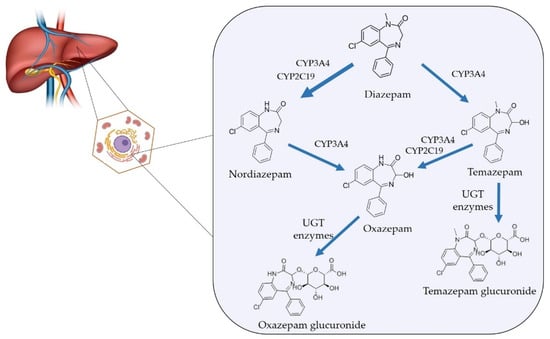

Interpreting analytical findings for benzodiazepines and Z-drugs remains a complex task due to extensive metabolic interconversion, variable pharmacokinetics, and individual differences in CYP450 enzyme activity. Many benzodiazepines such as diazepam, nordiazepam, temazepam, and oxazepam share a common metabolic cascade complicating the attribution of results to a specific parent compound. Therefore, analysis of parent-to-metabolite ratios is crucial to estimate time since exposure or differentiate therapeutic use from abuse [212,213].

5.2.1. Diazepam

Diazepam is among the benzodiazepines frequently implicated in non-medical use and forensic detections, reflecting both its wide availability and frequent prescription [214,215]. Diazepam is a long-acting benzodiazepine owing to its prolonged elimination half-life as well as the formation of long-lived active metabolites (N-desmethyldiazepam/nordiazepam, temazepam and oxazepam), which prolong clinical and toxicological effects and extend detection windows. Diazepam is extensively metabolized in the liver predominantly by cytochrome P450 enzymes, notably CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, which mediate N-demethylation and other reactions to form active metabolites. Interindividual variability in these enzymes contributes to differences in clearance and exposure [170,216,217,218]. Importantly, several metabolites (e.g., temazepam, oxazepam, and nordiazepam) are themselves clinically used benzodiazepines, which further complicates interpretation of toxicological findings because detection of a particular metabolite may reflect direct administration of that metabolite as a prescription drug rather than metabolism of diazepam [170,214,217]. The metabolic pathway of diazepam is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Diazepam metabolism in humans.

After oral or parenteral diazepam administration, the parent drug is relatively rapidly absorbed and distributed while the main active metabolite nordiazepam accumulates and declines more slowly because of its longer elimination half-life. Consequently, the diazepam to nordiazepam concentration ratio falls with time after ingestion. That is confirmed by several controlled-dose pharmacokinetic studies and forensic case series. Higher ratio values are commonly observed soon after diazepam dosing whereas low ratios (metabolite-dominant profiles) are typical later or during chronic exposure [170,219]. In this regard, Wang et al. developed correlation models between diazepam/nordiazepam concertation ratio and time since oral diazepam ingestion and found that concentration-ratio based models predicted time since dose with reasonable accuracy (prediction errors < 20%). This supports the general principle that a relatively high diazepam to nordiazepam concentration ratio favors more recent intake [220].

The pattern and ratio of metabolites along with clinical data, offers a multidimensional framework for interpretation. The presence of all three metabolites (nordiazepam, temazepam and oxazepam) strongly supports diazepam use, particularly when accompanied by measurable diazepam. It indicates sufficient time for sequential metabolism through both N-demethylation and hydroxylation pathways. The relative proportions of nordiazepam and oxazepam reflect the metabolic progression and may also aid in approximating time since ingestion [170,213]. Isolated nordiazepam presence cannot confirm diazepam use without supporting evidence (e.g., parent diazepam or co-occurrence of minor metabolites). A sample containing only nordiazepam, especially at steady-state concentrations, may represent therapeutic use of nordiazepam rather than diazepam ingestion [175]. The presence of temazepam and/or oxazepam without diazepam or nordiazepam may be interpreted in several ways. Temazepam may originate from diazepam, but also from primary therapeutic administration. Oxazepam is the final common metabolite of diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, nordiazepam and temazepam, and is non-specific indicator for the parent compound. Detection of oxazepam alone typically suggests remote exposure or metabolism of another benzodiazepine, especially if diazepam and nordiazepam are absent or below quantitation limits [209]. It should be noted, that genetic polymorphism in CYP2C19 (poor metabolizers) or concurrent CYP inhibitors intake (e.g., omeprazole, fluoxetine) may change diazepam pharmacokinetics yielding higher diazepam and lower nordiazepam concentrations than expected for the time since dose, which could be mistaken for recent ingestion if not contextualized [216]. Although the diazepam to nordiazepam concentration ratio is informative, the literature does not support a universally valid numeric cut-off that applies across matrices and populations. Ratio values are influenced by dose, formulation, time since dose, co-medications, hepatic and renal function, age, and analytical variability. Therefore, the designation of specific threshold values of diazepam/nordiazepam ratio indicating recent and chronic use should be avoided in formal reporting unless supported by validated, lab-specific models [213,219].

5.2.2. Other Benzodiazepines

The interpretation of analytical results for alprazolam and other short- to intermediate-acting benzodiazepines also requires careful consideration of metabolic pathways and analytical limitations. Alprazolam is characterized with a relatively short half-life and rapid addiction [221]. It undergoes predominant oxidation via CYP3A4, yielding α-hydroxyalprazolam and 4-hydroxyalprazolam as its principal metabolites that are further conjugated with glucuronic acid and excreted through the kidney. One of the metabolites, α-hydroxyalprazolam is pharmacologically active and is commonly detected in biological samples [200,212,216]. The parent-to-metabolite ratio may offer qualitative insight into time since ingestion as recent exposure typically yields detectable parent alprazolam with lower α-hydroxyalprazolam, whereas higher levels of the metabolite suggests delayed or past intake [171].

Bromazepam presents a distinct interpretive challenge due to partial metabolism to hydroxybromazepam and minor desmethyl derivatives, which exhibit limited specificity for source identification. The presence of both parent compound and its hydroxy-metabolite in plasma or urine suggests recent exposure, whereas isolated hydroxybromazepam, especially in urine should be interpreted cautiously, as interindividual glucuronidation capacity significantly alters excretion kinetics [68,175].

Flunitrazepam undergoes metabolic processes of reduction, hydroxylation and N-demethylation yielding 7-aminoflunitrazepam, 3-hydroxyflunitrazepam and N-desmethylflunitrazepam, respectively. The major metabolite, 7-aminoflunitrazepam remains a key biomarker for both therapeutic and illicit use. The detection of 7-aminoflunitrazepam without parent compound indicates prior ingestion, while coexistence of unchanged flunitrazepam implies recent use. Because of its metabolic stability 7-aminoflunitrazepam persists in urine longer than other benzodiazepine metabolites, extending interpretive windows up to several days. It should be noted that genetic polymorphism, drug–drug interactions as well as stability of flunitrazepam during storage may result in large interindividual variability in the toxicological results [222,223]. Additionally, in case of suspicion of a crime, flunitrazepam and 7-aminoflunitrazepam may be detected in hair samples more than 6 months later [221]. Moreover, knowing the concentration of flunitrazepam and 7-aminoflunitrazepam as well as its parent-to-metabolite concentration ratios in hair samples may be useful for the differentiation of therapeutic drug intake from random ingestion [224].

5.2.3. Z-Drugs

In contrast to benzodiazepines, Z-drugs have short half-lives and undergo rapid hepatic biotransformation. Zolpidem and zopiclone/eszopiclone are predominantly metabolised by CYP3A4 while zaleplon is metabolized primarily by the enzyme aldehyde oxidase into inactive metabolites. Zopiclone/eszopiclone has an active metabolite, (S)-desmethylzopiclone. The detection window for Z-drugs in urine is longer than in blood/plasma (approximately 24–48 h) [201]. For zopiclone and eszopiclone, metabolite-pattern analysis rather than parent-only detection should be used since unchanged parent drug is excreted in low amounts and major metabolites predominate in biological fluids [225]. Furthermore, hair samples analysis have identified enantiomeric differences in zopiclone metabolites that may be useful in distinguishing legal therapeutic formulations from illicit analogues [226].