Abstract

Background/Objectives: The exposome includes all environmental exposures throughout a lifetime and profoundly influences health and disease, reflecting the totality of environmental chemical exposures throughout an individual’s life, encompassing both natural and anthropogenic chemicals from external sources. Conventional methods for environmental chemical analysis have generally concentrated on individual representatives or substance classes; however, single analyte/class techniques are impractical for extensive epidemiological studies that require the analysis of thousands of samples, as anticipated for forthcoming exposome-wide association studies. This narrative review analyzes the evolution and implementation of multiclass assays for measuring ambient chemical exposure, emphasizing analytical techniques that provide the concurrent quantification of various chemical classes. Methods: This narrative review consolidates existing literature on multiclass analytical methodologies for measuring exposure to environmental chemical mixtures, encompassing mass spectrometry platforms, sample preparation techniques, chromatographic separation methods, and validation strategies for thorough exposure assessment in human biomonitoring research. The review includes liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry techniques, solid-phase extraction methods, and data analysis strategies for both targeted and non-targeted study. Results: Multi-class methodologies provide the concurrent quantification of compounds from many classes without the necessity for distinct conventional procedures, thus minimizing time, expense, and sample volume. The robustness of the method indicates appropriate extraction recovery and matrix effects between 60 and 130%, inter-/intra-day precision under 30%, and remarkable sensitivity with detection limits from 0.015 to 50 pg/mL for 60–80% of analytes in the examined human matrices. The methodology facilitates the concurrent identification of the endogenous metabolome, food-associated metabolites, medicines, home chemicals, environmental contaminants, and microbiota derivatives, including over 1000 chemicals and metabolites in total. Conclusions: These thorough analytical methods deliver the requisite performance for extensive exposome-wide association studies, yielding quantitative results and uncovering unforeseen exposures, thereby augmenting our comprehension of the chemical exposome, which is essential for advancing disease prevention in public health and personalized medicine.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Exposome Paradigm and Environmental Health

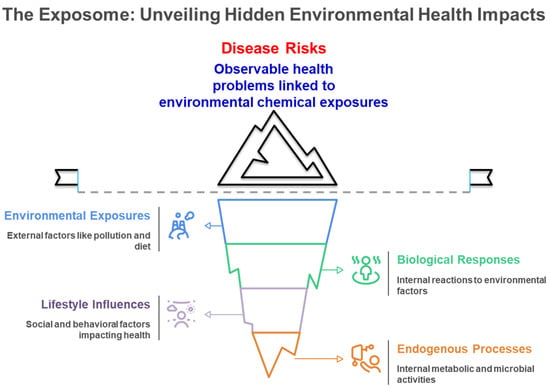

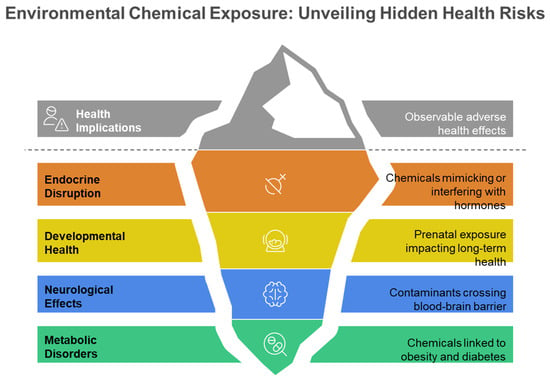

The exposome signifies a transformative approach in environmental health research, including the entirety of environmental exposures experienced by an individual over their lifetime and their significant influence on human health and disease [1,2,3,4,5]. The exposome paradigm was initially proposed by Wild in 2005 [2] and is defined as the aggregate of exposures that individual encounters during their lifetime [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Figure 1 illustrates the comprehensive nature of the exposome paradigm, demonstrating how external environmental exposures, lifestyle influences, and endogenous processes interact to produce biological responses that ultimately manifest as observable disease risks, representing the cumulative environmental influences on human health throughout the lifespan. The chemical exposome covers the totality of environmental chemical exposures experienced by an individual over their lifetime, incorporating both natural and anthropogenic chemicals from external sources—such as inhalation of polluted air, the intake of food compounds and medications, along with the consumption of tainted food and water—as well as internal exposure sources, including metabolic byproducts from gut microbiota (Figure 1) [3,6,7]. Environmental factors significantly influence health status, surpassing the previously acknowledged impact of the intrinsic genome. Factors such as individual food, smoking, and air pollution may account for approximately 46% of global mortality [8,9]. Environmental exposure has emerged as a significant risk factor for public health, correlating with unknown illness risks such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, respiratory disorders, and other chronic conditions [5,6,10]. Figure 2 depicts the varied health consequences of environmental chemical exposures, highlighting the role of the chemical exposome in multiple disease pathways, such as endocrine disruption, developmental disorders, neurological effects, and metabolic dysfunction throughout the human lifespan. These diverse health endpoints reflect the complex toxicological effects of the chemical exposome on human health. This comprehensive understanding of environmental influences has driven the need for more sophisticated analytical approaches capable of capturing the complexity of human chemical exposures.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of the Exposome and Its Health Impacts.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of major health implications associated with environmental chemical exposures.

1.2. Evolution of Multiclass Analytical Approaches

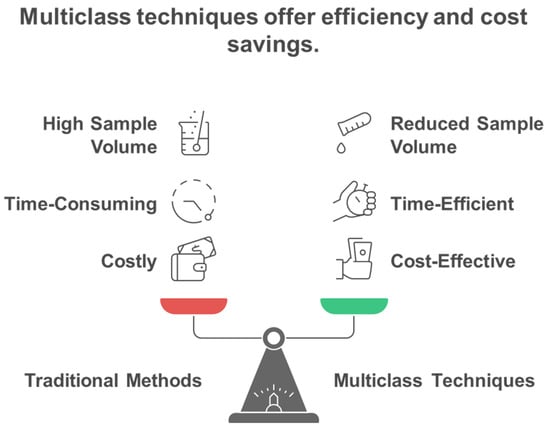

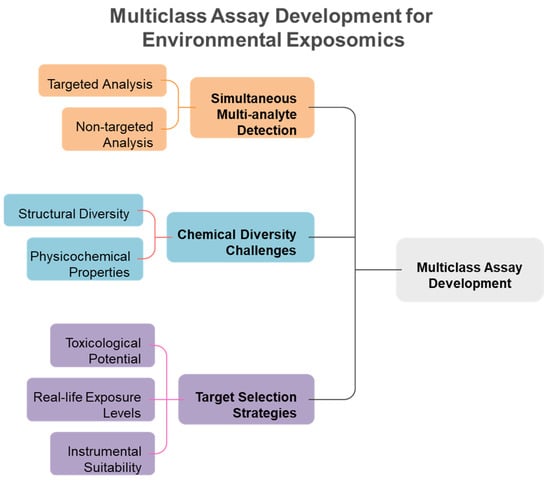

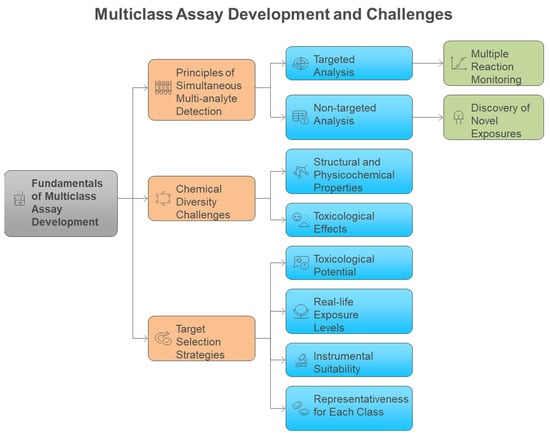

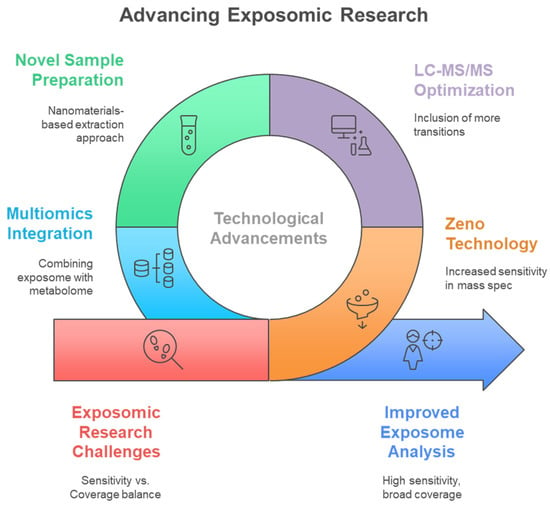

Traditional single-analyte approaches have proven inadequate for comprehensive exposome measurement, leading to the development of innovative multiclass analytical methodologies that can simultaneously quantify diverse chemical classes. Conventional methods for analyzing environmental chemicals have generally concentrated on individual representatives or specific substance classes. Consequently, this focus may lead to the banning of certain chemicals, only to be replaced by less studied analogs that could potentially exhibit similar or even more severe toxicological effects [11]. Methods focusing on a single analyte or class are not suitable for extensive epidemiological studies that require the analysis of thousands of samples, as suggested for upcoming exposome-wide association studies [11]. Most targeted analytical methods quantify fewer than 15 biomarkers of exposure from a singular chemical class within each biospecimen, employing class-specific extractions and instrumental analyses for substances such as dialkyl phosphates (DAPs), EP, herbicides, OPFR, OP pesticides, PAH, PHTH, pyrethroids, tobacco smoke, and VOC [12]. To address these challenges, multi-class techniques are becoming increasingly favored by utilizing extractions that enhance various classes of chemicals in human specimens and enabling simultaneous detection. This approach allows for the measurement of multiple classes of chemicals without the need for separate conventional workflows, ultimately leading to reductions in time, cost, and sample volume [12,13]. Figure 3 illustrates the fundamental advantage of multiclass analytical approaches over traditional single-class methods, demonstrating how simultaneous measurement of diverse chemical classes achieves significant improvements in analytical efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and sample conservation for large-scale exposome studies. Traditional approaches require separate analytical workflows for each chemical class, creating significant bottlenecks in large-scale studies. Multi-class techniques overcome these limitations by enabling simultaneous detection of diverse chemical classes without separate conventional workflows, providing substantial reductions in analysis time, cost, and required sample volumes while maintaining comprehensive chemical coverage. The shift towards multiclass analytical methods has been motivated by the necessity to tackle the intricacies of the exposome, where food-derived metabolites and endogenous compounds typically exist in the millimolar to picomolar concentration range, whereas pollutants may be detected at levels three orders of magnitude lower [14,15]. Recent advancements in analytical instrumentation have accelerated the detection of trace amounts of xenobiotics in human tissues and biofluids, enabling a more accurate quantitative evaluation of an individual’s chemical burden [16]. However, analytical challenges remain, including matrix effects, sensitivity issues, and the need for non-discriminatory sample preparation methods that balance interference reduction with broad chemical coverage [17,18]. The recent technological advancements allow for the concurrent analysis of numerous compounds spanning various chemical classes, transforming the capabilities of exposome research (Table 1). Figure 4 illustrates the comprehensive framework for multiclass assay development in exposomics research, highlighting the integration of targeted and non-targeted approaches while addressing the fundamental challenges posed by chemical diversity in environmental exposure assessment. The framework encompasses both targeted and non-targeted analytical approaches, target selection strategies based on toxicological relevance and exposure prevalence, and the fundamental challenges posed by the vast chemical diversity of environmental contaminants spanning multiple orders of magnitude in physicochemical properties.

Figure 3.

Comparison of traditional single class versus multiclass analytical approaches for environmental chemical exposure measurement.

Table 1.

Overview of Multiclass Assays for Environmental Chemical Mixtures Exposure Measurement in Humans: Study Characteristics, Analytical Platforms, and Performance Metrics.

Figure 4.

Schematic overview of the key components and challenges in developing multiclass analytical methods for comprehensive exposome characterization.

1.3. Scope and Objectives of This Narrative Review

This narrative review provides a comprehensive examination of multiclass assays for measuring environmental chemical mixture exposure, with particular focus on analytical methodologies that enable simultaneous quantification of diverse chemical classes in biological matrices [12,14,40]. This narrative review examines the development and application of multiclass assays for environmental chemical exposure measurement, focusing on analytical methodologies that enable simultaneous quantification of diverse chemical classes [41,42]. The scope encompasses mass spectrometry platforms, sample preparation strategies, and validation approaches for comprehensive exposure measurement in human biomonitoring studies, with particular emphasis on the technical challenges and solutions for analyzing complex chemical mixtures in biological matrices [40,41,43]. This review highlights the necessity for thorough analytical methods that include all significant environmental chemical classes in biological matrices to facilitate accurate exposure and risk evaluation [41,42,44]. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of recent multiclass analytical studies for environmental chemical exposure measurement, summarizing study designs, analytical platforms, target analyte numbers, and primary research objectives across diverse human biomonitoring applications. The methodology facilitates, for the first time, the concurrent characterization of the food-derived metabolites, endogenous metabolome, medicines, environmental contaminants, home chemicals, and microbial derivatives, encompassing over 1000 metabolites in total [14]. The distinction between exposomics and metabolomics is critical for understanding the scope of multiclass analytical approaches. While metabolomics focuses on comprehensive measurement of endogenous metabolites and biological responses, exposomics specifically targets environmental chemical exposures and their biomarkers throughout the human lifespan. The novel exposomics methodology complements metabolomics techniques and is scalable to facilitate extensive exposome research. Through systematic evaluation of current methodologies and their applications, this review aims to guide future developments in exposome-scale analytical approaches and their implementation in large-scale epidemiological studies (Table 1) [12,14,41].

2. Fundamentals of Multiclass Assay Development

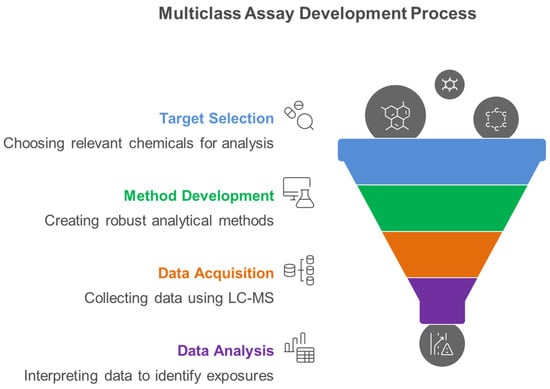

Figure 5 illustrates the systematic four-phase workflow essential for developing robust multiclass analytical methods that can simultaneously quantify diverse environmental chemical classes, representing the methodological foundation for comprehensive exposome characterization in human biomonitoring studies. The systematic workflow encompasses four critical phases: target selection based on toxicological relevance and exposure prevalence, method development utilizing advanced LC-MS platforms, data acquisition through optimized analytical protocols, and comprehensive data analysis for exposome characterization.

Figure 5.

Multiclass Assay Development Process for Measuring Environmental Chemical Mixture Exposure.

2.1. Principles of Simultaneous Multi-Analyte Detection

The foundation of multiclass assay development lies in leveraging advanced mass spectrometry platforms that enable simultaneous detection and quantification of chemically diverse compounds exhibiting excellent sensitivity and specificity. Liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS) is presently the leading technique in exposome-wide association studies (ExWAS) and is applicable for both targeted and non-targeted analysis [16,17,40]. Targeted assays concentrate on measuring a specific group of compounds with exceptional sensitivity, accuracy, and precision. In contrast, non-targeted analysis and suspect screening seek to identify and characterize chemicals without prior knowledge of the sample’s composition, potentially uncovering novel or unexpected exposures [24,40,42]. Owing to their excellent assay robustness, sensitivity, and quantitative capabilities, multi-analyte targeted LC-MS/MS approaches are frequently the preferred option, enabling the detection and quantification of a diverse array of compounds at trace concentration levels and forming the foundation for exposomics [16,23,24,45]. Multiple reaction monitoring is the preferred method for targeted analysis, relying on the observation of typically two transitions per analyte, which facilitates excellent sensitivity and specificity [45]. A triple quadruple mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source was employed in the research, utilizing multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) mode for data collecting of each target analyte [12,16]. The most significant primary ion transition was utilized for quantification, while the most intense secondary ion transition served for confirmation [12,16]. These instrumental capabilities form the technical backbone for achieving the sensitivity and selectivity required for comprehensive exposome analysis. Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of mass spectrometry platforms, sample preparation strategies, chromatographic approaches, and validation parameters employed across multiclass environmental chemical analysis methods, demonstrating the diversity of analytical approaches used in exposome research.

Table 2.

Mass Spectrometry Platforms, Sample Preparation and Chromatographic Separation Strategies, and Method Validation Parameters for Multiclass Analysis of this Review.

2.2. Chemical Diversity Challenges in Environmental Exposomics

The simultaneous analysis of multiple chemical classes presents unprecedented analytical challenges due to the vast physicochemical diversity of environmental contaminants, spanning orders of magnitude in polarity, molecular weight, and chemical properties [16,22,46,47]. The wide range of structural and physicochemical characteristics of toxicants presents a significant challenge for the simultaneous analysis of various chemical classes [16]. The diverse chemical properties of multiclass CECs make their simultaneous analysis quite challenging. The extensive variety in physical and chemical properties, including the broad polarity range, poses a significant challenge for concurrent screening through a single LC-MS analysis. The varied chemical properties of the extracted compounds necessitate chromatographic columns capable of retaining molecules across a wide spectrum of polarities, while also efficiently separating multiple isomers that share the same mass to charge (m/z) ratios [16]. The extensive physicochemical variety of xenobiotics suggests a broad spectrum of toxicological impacts on humans, including liver carcinogenicity, nephrotoxicity, and estrogenicity (Figure 2) [22]. Approximately 5000 environmental chemicals are believed to be distributed and accumulated in humans. Residues can undergo various transformations into multiple metabolite and product forms through phase-I and -II reactions, including oxidation, hydroxylation, and dealkylation in biological metabolism, thereby broadening their characteristics and the list for screening exogenous mixtures. The integration and thorough assessment of the metabolome and exposome present significant challenges due to the vast range of concentrations of metabolites, drugs, food components, and environmental pollutants, which cover around ten orders of magnitude and include a wide variety of chemical classes [22]. These chemical diversity challenges necessitate sophisticated analytical strategies that can accommodate the full spectrum of environmental contaminants while maintaining analytical performance (Figure 4) [46,48]. The boundaries between exposome and metabolome research domains are defined by their distinct analytical targets and biological significance, though both utilize similar mass spectrometry platforms for chemical characterization. The exposome focuses on external environmental chemical exposures and their biomarkers, while the metabolome encompasses endogenous biochemical processes. The overlap occurs in the analytical detection of chemical compounds in biological matrices, where environmental chemicals typically detected at minimal levels (pg-ng/mL range) coexist with endogenous metabolites found at much higher concentrations (picomolar to millimolar range) [22,39]. This concentration gap of approximately 1000-fold between endogenous substances and environmental pollutants represents a key analytical challenge requiring specialized sample preparation and detection methods [28,35].

2.3. Target Selection Strategies for Comprehensive Coverage

Strategic selection of target analytes requires balancing toxicological relevance, exposure prevalence, analytical feasibility, and representativeness across chemical classes to ensure comprehensive exposome coverage [49,50,51]. The selection of chemicals was informed by their toxicological significance (i.e., is the compound relevant in a health context?), actual exposure levels (i.e., does this compound exist in quantities that can be measured?), compatibility with the instrumental platform (i.e., is retention through reversed-phase LC and ionization via ESI-MS adequate for sensitive analysis?), and being representative for each class of toxicants to ensure comprehensive monitoring of various adverse exposures [49,50]. Target analytes suitable for the multiclass HBM method were chosen according to priority lists of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EDC-relevant EU legislations on endocrine disruptors, or novel or emerging compounds recently identified in the scientific literature [49,50,52]. The analyte panel was developed from prior research and covered air pollutants, disinfectants and their byproducts, endogenous estrogens, flame retardants, food processing by-products, industrial products, medical drugs, mycotoxins, personal care products, pesticides, phytoestrogens, phytotoxins, plastic-related chemicals, and PFAS compounds [11,50,53,54]. A multiclass targeted analyte list was established beforehand to direct method development, with the choice of anthropogenic contaminants, natural dietary substances, and tobacco markers limited to substances that are regularly tracked in human serum or urine by the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and European HBM4EU priority substances [41,49,50]. The choice of target analytes and analyte classes aimed to be as extensive as technically possible, encompassing various structures, everyday life exposure levels, and toxicological pathways of action [41,51,54]. These systematic selection criteria ensure that multiclass methods capture the most toxicologically relevant and prevalent exposures while maintaining analytical feasibility for large-scale studies (Figure 4) [49,50,51].

3. Mass Spectrometry Platforms for Multiclass Analysis

3.1. Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry (QQQ-MS/MS)

Triple quadrupole mass spectrometry represents the gold standard for targeted multiclass analysis, providing exceptional sensitivity and quantitative precision essential for trace-level environmental contaminant detection in biological matrices. A triple quadruple MS instrument featuring an Agilent Jet Stream electrospray ionization (AJS-ESI) source was utilized in studies, employing mass spectrometry in multiple-reaction monitoring mode (MRM) for data acquisition of each target analyte [39]. A Sciex 6500+ triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (MS) (SCIEX, Framingham, Massachusetts, USA) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source was employed in either positive or negative ionization mode, operating sequentially or concurrently, to detect and quantify the analytes of interest [12]. Although high-resolution, nontargeted methods are suggested as the future cornerstone for exposomics research, targeted methods using triple quadrupole instrumentation continue to deliver superior sensitivity, linearity, and less demanding data processing requirements [16,40,41]. Detection and quantification of biomarkers were carried out using a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer functioning in multiple reaction monitoring mode, utilizing both positive and negative electrospray ionization [29]. The superior quantitative capabilities of triple quadrupole systems make them indispensable for comprehensive exposome studies requiring precise measurement of hundreds of analytes.

3.1.1. Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) Optimization

Optimization of multiple reaction monitoring parameters constitutes a pivotal phase in methodological advancement, requiring systematic tuning of mass spectrometric conditions to achieve maximum sensitivity and selectivity for each target analyte. Enhancing the method for multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions involved selecting precursor ion (Q1) and product ion (Q3), fine-tuning entrance potential (EP), collision energy (CE), and collision cell exit potential (CXP) [24]. Values of Q1, Q3, EP, and CE were refined for numerous compounds on a new Qtrap 7500 instrument, utilizing method parameters from previous methods on a Qtrap 6500+ as the foundation [24]. Parameters specific to the analyte, including declustering potential, entrance potential, collision exit potential, and collision energy, were optimized individually through direct syringe infusion of each compound into the mass spectrometer [12]. Two fragment ions were selected for each analyte as quantifier and qualifier ions. To ensure optimal data quality, dwell periods were modified for all analytes to secure adequate data points for each chromatographic peak [24]. The MRM method utilizing quantifier and qualifier ion transitions enables both detection and quantification, as well as identification and confirmation, which is crucial for targeted analyses [12]. These comprehensive optimization procedures ensure robust analytical performance across diverse chemical classes while maintaining the specificity required for complex mixture analysis (Table 2) (Figure 5).

3.1.2. Sensitivity and Selectivity Considerations

The exceptional sensitivity achieved through optimized triple quadrupole methods enables detection of environmental chemicals at extremely low concentrations, with limits of detection typically in the sub-ng/mL range across diverse biological matrices [11,55,56,57,58,59]. For the majority of compounds, the detection and quantitation limits (LODs/LOQs) were found to be within the range of 0.001–0.1 ng/mL [16]. Detection limits varied from 0.01 to 1.0 ng/mL of urine, with most being ≤0.5 ng/mL (42 out of 50) [12]. The evaluation of method robustness showed appropriate extraction recovery and matrix effects (SSE) ranging from 60 to 130%, inter-/intra-day precision (RSD) below 30%, and outstanding sensitivity (limit of detection, 0.015–50 pg/mL) for 60–80% of the analytes across the studied matrices [24]. The method shows remarkable sensitivity with detection limits ranging from 0.01 to 1.0 ng/mL, outstanding precision with relative standard deviations under 20%, and extraction recoveries ranging from 80% to 110% [29]. These sensitivity achievements enable reliable quantification of environmental exposures at levels relevant for human health risk assessment [11,55,56,57,58]. Table 3 provides comprehensive detection performance data for multiclass analytical methods across diverse chemical classes and human biological matrices, demonstrating the analytical capabilities achieved in exposome research.

Table 3.

Chemical Classes, Target Analytes, and Detection Performance Across Different Human Biological Matrices.

3.2. High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS)

High-resolution mass spectrometry platforms offer complementary capabilities for multiclass analysis, providing accurate mass determination and structural elucidation essential for non-targeted screening and discovery of unknown exposures [41,48,51,60,61,62,63]. Liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry-based approaches offer the potential to enhance our understanding of the exposome in future exposome-wide association studies, as this technique can identify a wide range of small molecules with various chemical properties, from environmental xenobiotics to endogenous metabolites [41,51,60,62,64]. External stressors, such as xenobiotics and environmental changes, are assessed concurrently alongside phenotypical changes resulting from these exposures, positioning LC-HRMS as an excellent platform for creating comprehensive methods to investigate the exposome [41,51,60,62]. Advancements in high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) have resulted in an increasing number of HRMS-based screening methods being published in recent years [41,48,51,60,61,65,66]. While these methods could cover a broader chemical space, they presently lack the necessary sensitivity to effectively monitor a large number of pollutants in the environment at ultra-trace levels [41,60,64]. The broad chemical coverage and retrospective analysis capabilities of HRMS make it invaluable for comprehensive exposome characterization [41,51,61,62,67].

3.2.1. Data-Dependent and Data-Independent Acquisition Approaches

Data-dependent or independent acquisition strategies enable systematic fragmentation of detected compounds, providing structural information essential for compound identification and confirmation in complex biological matrices [68,69]. Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) focuses on choosing the n “n” most intense m/z detected at the MS1 level for subsequent selection and fragmentation, typically resulting in high-quality MS2 spectra of several detected features [25]. Data-dependent acquisition (DIA) focuses on the systematic separation and fragmentation of all precursor ions across an extensive window, facilitating a thorough examination of mass spectra [25]. Data-dependent acquisition utilizing an inclusion list of the precursor ions was employed for analyte confirmations [35]. Data-dependent acquisition was used for analyte confirmation, as it provides higher confidence and cleaner MS2 spectra [34]. Since the levels of exogenous residues in serum are typically 100–1000 times lower than those of internal metabolites, it is challenging to acquire adequate fragments of external residues through multiple DDA during a single injection screening [37]. Despite the challenges related to concentration, the DDA and DIA strategies offer crucial structural information that enables confident compound identification, provided they are properly optimized. This is especially true when these strategies are used in conjunction with accurate mass determination and spectral library matching techniques in non-targeted exposome studies [68,69].

3.2.2. Accurate Mass Determination and Structural Elucidation

Accurate mass determination combined with MS/MS fragmentation patterns enables confident structural elucidation and compound identification, supporting both targeted quantification and discovery of unknown exposures [48,70,71,72,73,74]. To ensure the precision of MS1 and MS2 data, the precursor ions and fragments from clean standards produced experimentally must align with theoretic calculations within ±10 ppm [37]. In MS1 searching, the variations in retention time and mass accuracy across experimental data and the database were established from ±0.30 min and ±10 ppm, respectively. Compounds that achieved an MS1 score above 50 were categorized as tentatively positive findings. [37]. Following the identification of potential candidates whose precursors exhibited mass differences aligned with the suspect list (Δmass < 5 ppm), a comparison was made between their MS/MS spectra and those found in the Mass Bank database or predicted through MetFrag [38]. Spectral matching for annotations with a confidence level of 2 takes into account an accurate MS1 mass deviation of up to 0.005 Da within the detected precursor ion and the library record, along with a total identification score exceeding 700 [34]. These structural elucidation capabilities enable discovery and identification of previously unknown exposures in human biomonitoring studies [48,62,70,71,72,73,74,75]. Computational tools and databases play a critical role in non-targeted identification of environmental chemicals in exposome research. Once potential candidates with precursors mass matched to suspect lists are identified, MS/MS spectra are compared with those located in the MassBank database or predicted via MetFrag for structural elucidation [38]. Spectral matching for annotations considers accurate MS1 mass deviation and total identification scores, with European Mass Bank, MS-DIAL, and Mass Bank of North America databases being used for metabolite annotation [34,35]. These computational approaches enable confident identification of previously unknown exposures while maintaining appropriate confidence levels for structural assignments.

3.3. Hybrid Approaches and Method Integration

Integration of targeted and non-targeted approaches within single analytical workflows maximizes the benefits of both methodologies, enabling sensitive quantification of priority analytes while maintaining discovery potential for unknown exposures [76]. A single-injection LC-MS approach to integrated exposomics and metabolomics, whether targeted or untargeted, merges the strengths of both strategies, offering high sensitivity through targeted analysis and extensive coverage with the ability for retrospective data examination in untargeted analysis [25]. The implementation of Zeno technology, a linear ion trap stage preceding the TOF analyzer that enables duty cycles of up to 90%, leads to notable enhancements in sensitivity [25]. The results showed a notable enhancement in sensitivity, as evidenced by the ability to detect lower concentrations in spiked SRMs. The mean values for SRMs 1950 [77] and 1958 [78] were 2.2 and 3 times lower, respectively. Additionally, there was an overall increase in detection frequency by sixty-eight percent in the MRM-HR + SWATH mode as opposed to the SWATH-only approach [25]. The integrated approach of targeted and untargeted chemical exposomics facilitated accurate and detailed measurement of key analytes while also allowing for the identification of unforeseen exposures that may have health implications. These hybrid approaches represent the future of exposome analysis, combining the quantitative precision of targeted methods with the discovery potential of non-targeted screening in a single analytical workflow.

4. Sample Preparation Strategies for Diverse Chemical Classes

4.1. Extraction Method Development and Optimization

Effective sample preparation represents the cornerstone of successful multiclass analysis, requiring sophisticated extraction strategies that can simultaneously recover chemically diverse compounds while minimizing matrix interferences and maintaining analytical performance [17,23,79,80,81]. The creation of multiclass assays necessitates careful refinement of the complete analytical workflow, influencing sample preparation procedures, to minimize interferences, isolate, and concentrate analytes across various matrices [23]. Effective sample pretreatment prior to instrumental analysis can minimize interferences, isolate, and enhance analytes in different matrices, and numerous sample preparation methods have been refined to examine the exposome [17,23,79]. The presence of target analytes with diverse physicochemical properties, such as polarity, poses an important hurdle for solid-phase extraction techniques in exposomics, stemming from the differences in analyte-sorbent interactions [17,23,80]. Appropriate sample preparation methods are crucial, as components of the sample matrix can significantly influence signal intensities, especially for trace level compounds. Additionally, a limited duty cycle can affect data quality in extensive LC-MS/MS assays aimed at analyzing hundreds of analytes in one run [23,79,80]. The selection and optimization of extraction methods must balance chemical coverage, recovery efficiency, and practical considerations for high-throughput applications [17,23,80,81,82].

4.1.1. Liquid–Liquid Extraction Approaches

Liquid–liquid extraction methods offer broad chemical coverage and compatibility with diverse analyte classes [83,84], making them particularly suitable for comprehensive exposome analysis despite requiring careful optimization to achieve acceptable recoveries across all target compounds. The sample preparation involved two rounds of liquid–liquid extraction using 3 mL of a combination of ethyl acetate and n-hexane (3:2, v/v) with 0.6% formic acid. Prior to the extraction procedure, 200 μL of plasma was combined with isotope-labeled surrogate standards to compensate for analyte loss throughout sample preparation and to mitigate any matrix effects [28]. The suggested LLE method aligns better with a variety of target CEC classes compared to solid-phase extraction using different sorbents, and conventional SPE-based methods tend to be more time-intensive and significantly pricier than the LLE approach [28]. For serum and urine extraction, a volume of 200 μL was augmented with 10 μL of internal standard solution and extracted using 790 μL of ACN/MeOH (1/1) via sonication (10 min, 4 °C), followed by protein precipitation during a freeze-out phase (2 h, −20 °C) [11]. The liquid extraction and precipitation of proteins are commonly employed extraction methods in exposomics because of their relatively broad chemical coverage [23]. These liquid–liquid extraction approaches provide cost-effective and broadly applicable methods for multiclass compound recovery [84], though they may require additional cleanup steps for optimal performance.

4.1.2. Solid-Phase Extraction Techniques

Solid-phase extraction (SPE) represents the preferred approach for many multiclass applications, offering superior cleanup capabilities, enhanced selectivity, and improved method robustness compared to traditional liquid–liquid extraction methods [85,86]. SPE is typically recognized for its effective cleanup, enhanced selectivity, and reduced solvent consumption, making it appropriate for large sample sizes and high throughput, especially when compared with liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) in a multi-class method [12]. Oasis HLB SPE, a polymeric sorbent with a balanced hydrophilic-lipophilic nature, was found to be appropriate for this study after evaluating different sorbent materials; it has also been a favored universal sorbent in various multi-class methods [12]. A refined SPE protocol employing 96-well plates was implemented based on a recently established method, in which the SPE was preconditioned with methanol (MeOH) and subsequently with water (H2O) [24]. Recently, solid-phase extraction has garnered increased attention as an effective method for sample preparation in exposomics and is considered a promising strategy for future large-scale applications due to its ability to mitigate matrix effects, improve sensitivity, and ensure consistency in high-throughput studies [23]. The hydrophilic-lipophilic-balanced sorbent made from the polymeric N-vinylpyrrolidone-divinylbenzene is a flexible sorbent known for its effective recovery in extracting substances from water and wastewater. A 96-well plate version of HLB-SPE has been previously utilized for blood extraction [19]. The versatility and automation potential of SPE methods make them particularly attractive for large-scale exposome studies requiring consistent performance across thousands of samples [23,86].

4.1.3. Passive Equilibrium Sampling Methods

Passive equilibrium sampling (PES) offers a unique approach for extracting neutral and hydrophobic compounds from biological matrices, providing clean extracts with minimal matrix interference while being particularly effective for lipophilic environmental contaminants [87,88,89]. Passive equilibrium sampling is an approach developed for extracting compounds from tissue and biological samples, involving the placement of a defined mass of polymer into the sample, allowing chemicals to be extracted through diffusion directly into the polymer [19]. The selected polymer was polydimethylsiloxane, known for its ability to extract a range of hydrophobic as well as neutral chemicals with fairly rapid uptake kinetics, attributed to the high diffusion constants within the PDMS, though it can only extract charged organic molecules to a very limited extent [19]. PES using PDMS provides clean extraction of hydrophobic and neutral compounds without co-extracting undesirable matrix components such as proteins and salts, and the minimal lipid uptake that may occur from lipid-rich matrices does not compromise analytical performance in plasma samples [19]. While PES methods provide excellent cleanup for hydrophobic compounds, their limited applicability to polar and ionic species necessitates combination with complementary extraction techniques for comprehensive coverage [90].

4.2. Matrix-Specific Considerations

4.2.1. Biological Matrix Challenges

Biological matrices present complex analytical challenges due to high concentrations of endogenous compounds, varying protein and lipid content, and the need to extract trace-level contaminants from matrices dominated by endogenous substances [91,92]. Human biomonitoring samples can include various matrices, with typical examples being blood (full blood, serum, and plasma), breast milk, urine, and even organs like the placenta or post-mortem tissues such as the liver, brain, and adipose tissue [19]. The issue with chemical exposomics in plasma from humans lies in the significant concentration disparity, with endogenous substances being 1000 times more prevalent than environmental pollutants [34,93]. Phospholipids constitute the primary endogenous small molecules found in plasma, characterized by a rich and diverse mixture of more than 2000 chemical species [34]. Given the elevated fat and protein levels in milk, a two-phase extraction procedure was employed to reduce the organic layer of the matrix components [16]. The cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) is the most closely associated biological fluid with the brain, meaning that any deviations in the matrix are directly linked to pathological changes occurring in the brain [36]. Although it holds biological importance, the quantity of metabolomics/exposomics studies conducted on CSF samples is limited due to the invasive and valuable nature of the sample (which necessitates a lumbar puncture) along with methodological hurdles, such as the absence of standard materials and the relatively low concentrations of chemicals in CSF relative to other matrices like blood [36]. These biological matrix challenges require specialized extraction and cleanup procedures to achieve adequate sensitivity for trace-level environmental contaminants while managing high concentrations of interfering endogenous compounds [17,91].

4.2.2. Environmental Sample Complexity

Environmental samples present additional complexity due to variable matrix composition, potential for high levels of interfering compounds, and the need to accommodate samples with widely varying chemical compositions and concentrations [91,94,95]. The enhanced “all-in-one” method combined with QQQ MS was utilized to assess the concentrations of CECs in a range of aqueous specimens, which include two human urine samples, three sewage effluents, and thirteen surface waters [39]. The matrix effects from urine were more pronounced than those from the sewage effluent, probably because of the increased levels of urea, inorganic salts, and creatinine present in urine matrices [39]. The salt constituents in sample matrices might reduce the trapping efficiency and present significant matrix effects on the CECs that eluted on the MMIE column [39]. Environmental sample complexity necessitates robust analytical methods capable of handling variable matrix compositions while maintaining consistent analytical performance [91,95,96].

4.3. Recovery and Matrix Effect Assessment

Comprehensive evaluation of extraction recovery and matrix effects across all target analytes is essential for method validation and ensuring reliable quantitative results in multiclass exposome analysis [12,14,16,19,62]. The extraction efficiency from urine and serum samples were elevated (median of 93% and 87%, respectively), whereas recoveries from breast milk were diminished (median of 54%) [16]. Extraction recoveries ranged from 83 to 109% [12]. Matrix effects were mitigated through the utilization of matrix-matched calibration standard curves and stable isotope-labeled internal standards [12]. Signal suppression or enhancement (SSE) was assessed as the ratio of the slope of the calibration curve created in a urine matrix to that of a curve constructed in a reagent-based water [12]. The average chemical recovery were 61% for SolvPrec, 38% for PES + SPE, and 27% for SPE, with PES + SPE significantly improving the mean chemical recovery relative to SPE, particularly for neutral hydrophobic compounds [19]. The use of internal standards for recovery correction in bioassays is unfeasible and presents difficulties for analytical target lists containing numerous chemicals, necessitating the attainment of consistent and uniformly distributed recoveries across hydrophilic to hydrophobic, charged to neutral, and to nonpersistent to persistent compounds [19]. Systematic assessment of recovery and matrix effects ensures that multiclass methods provide reliable quantitative data across the full range of target analytes, forming the foundation for accurate exposome characterization and subsequent health risk assessment [11,14,62].

5. Chromatographic Separation Strategies

5.1. Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography

Reversed-phase (RP) liquid chromatography serves as the primary separation technique for multiclass environmental analysis, providing effective retention and separation for the majority of target compounds across diverse chemical classes [97,98,99]. A RP column (Poroshell 120 EC-C18, 3.0 mm × 50 mm, 2.7 μm) was used as the first column to enrich and separate the majority of the CECs [39]. As expected, a majority of the CECs (compounds 1–87) demonstrated appropriate retention times and acceptable peak forms on the RP column [39]. However, a small subset of CECs (compounds 88–102) showed minimal retention, eluting near the void time with poor chromatography peaks [39]. Chromatographic separation was achieved using a Zorbax Eclipse Plus RRHD C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm; with corresponding Eclipse Plus guard column; Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, Delaware, USA) and a Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 RRHD delay column (4.6 × 50 mm, 3.5 μm) [31]. The analytical coverage is primarily influenced by the capabilities of various liquid chromatography configurations in capturing and separating molecules, with a one-dimensional reversed-phase C18 liquid chromatography concentrating on the analysis of exogenous chemical residues with medium and low polarity [37]. Specific liquid chromatography configurations utilizing phenyl columns and polar embedded columns were designed for the analysis of higher polarity residues and residue metabolites with enhanced polarity [37]. While reversed-phase chromatography provides excellent separation for most environmental contaminants, its limitations with highly polar and ionic compounds necessitate complementary separation strategies [98,100,101].

5.2. Mixed-Mode and Ion Exchange Chromatography

Mixed-mode and ion exchange (MMIE) chromatographic approaches address the limitations of traditional reversed-phase separation by providing retention mechanisms for highly polar and ionic compounds that are poorly retained on conventional C18 columns [102,103]. The MMIE column, examined as a third option, demonstrated the best performance among the three candidate columns [39]. This is likely due to its trimodal separation mechanisms, which include reversed phase, strong cation exchange, and weak anion exchange. It is compatible with aqueous samples and can separate both cationic and anionic compounds, thereby minimizing the effect of the residual aqueous solvent on the peak shapes [39]. A homemade trap column (3.0 mm × 20 mm) filled with a layered combination of WAX and WCX sorbents (Strata X-AW, Strata X-CW, Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, California, USA) was employed to trap ionic and highly polar CECs that are not retained by the RP column [39]. The mixed-mode sorbent was synthesized by combining equal weights of two solid-phase extraction sorbents, main secondary amine (PSA) and C18 (PSA + C18), prior to packing [23]. Given the robust anion-exchange interactions of PSA with frequently encountered acidic chemicals in exposomics, a basic methanol solution (3% NH3) was employed as the elution solvent to evaluate the recovery of the mixed-mode sorbent [23]. These mixed-mode approaches significantly expand the analytical coverage of multiclass methods by accommodating compounds across the full polarity spectrum [102].

5.3. Column-Switching and Multi-Dimensional Approaches

Column-switching and multi-dimensional chromatographic systems enable comprehensive analysis of chemically diverse compounds by combining multiple separation mechanisms within a single analytical run, maximizing both coverage and efficiency [39,104,105,106,107,108]. The concept of an “all-in-one” LC-MS system, or a “column-switching method”, employed in previous studies for the analysis of all chain-length PFAS, has been adapted with modifications in this study [39]. Instead of using two duo two-position, eight-port 2D-LC valves, two switching valves were implemented: a two-position, six-port valve and a two-position, 10-port valve, which are more commonly found in LC systems [39]. When the trap column was connected to the RP column, the highly polar and ionic CECs were enriched and trapped in the trap column during the first 6.5 min of the run [39]. Then, the valves were switched to position II, placing the trap column in standby mode, while the majority of CECs (compounds 1–87) were separated on the RP column and analyzed by MS [39]. A 2D-LC separation system was modified using an Agilent UPLC combination system, where a short Acquity BEH C18 column (2.1 × 5 mm, 1.7 μm) served as the pre-column to separate the initial sample into two fractions: a more polar portion and a less polar/nonpolar fraction [37]. A Discovery HS F5-5 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 3.0 μm) was optimized for the separation of relatively polar compounds, and for the segregation of less polar and nonpolar molecules, an Acquity BEH C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 μm) was used [37]. The methodology employs a dual-column system, utilizing both a reversed-phase (RP) column and a hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) column operating concurrently to address polar chemicals and predominantly nonpolar xenobiotics [22,60]. These multi-dimensional approaches represent a significant advancement in analytical capability, enabling comprehensive coverage of the chemical exposome within practical analysis times [41,106,107,108].

5.4. Large Volume Injection Techniques

Large volume injection techniques provide a powerful approach for enhancing method sensitivity by concentrating analytes at the column head, enabling detection of trace-level contaminants without extensive sample preconcentration steps [39,109,110,111]. Large volume injection (LVI) is another technique that can enhance method sensitivity via direct injection of a large sample volume into a LC column with minimal pretreatment [39]. The target analytes are concentrated at the column head and subsequently separated by gradient elution [39]. For the setup of LVI (900 μL), the RP gradient started at 97% of the aqueous mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.6 mL min−1, held for 6.5 min, with the injection valve in the main pass position [39]. LVI significantly increased the method sensitivity, achieving quantifying limits for 93 of the 102 CECs in different water matrices at <10 ng L−1 [39]. However, LVI also faces several limitations, as analytes with poor retention on LC columns exhibit deteriorated peak shapes, and matrix effects pose great challenges, particularly for the analytes that elute early, which compromises the quantitative accuracy and necessitates that the initial column eluate be discarded [39]. Greater injection volume with little matrix interference enabled precise multiclass targeted detection of 77 key analytes: Median MLOQ = 0.05 ng/mL for 200 μL of plasma [34]. While large volume injection techniques offer significant sensitivity enhancements [39,110,111,112], their implementation requires careful consideration of matrix effects and chromatographic performance to maintain analytical quality across all target analytes [39,109].

6. Biological Matrix Applications

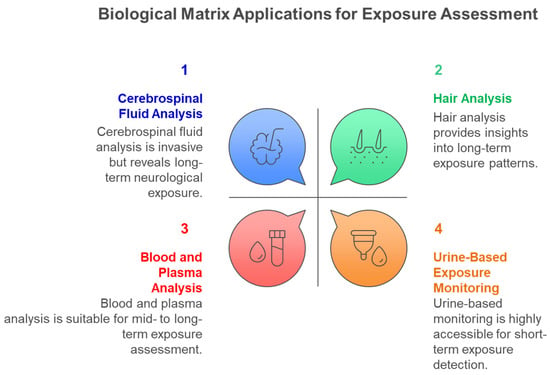

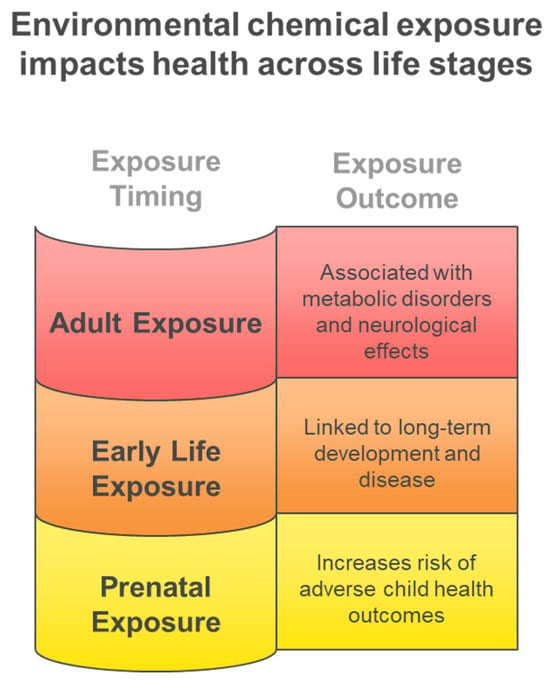

Figure 6 illustrates the diverse biological matrices employed in multiclass exposome analysis, each providing unique temporal windows and accessibility characteristics that complement comprehensive environmental chemical exposure assessment across different study designs and population requirements. Cerebrospinal fluid provides direct evidence of central nervous system exposure despite its invasive collection requirements, hair analysis enables assessment of chronic exposure patterns over extended periods, blood and plasma analysis offers systemic exposure characterization with moderate temporal resolution, and urine-based monitoring provides highly accessible short-term exposure detection capabilities for large-scale biomonitoring studies. Figure 7 illustrates the critical importance of exposure timing in determining health outcomes, demonstrating how the exposome paradigm encompasses diverse environmental influences across the entire lifespan, from prenatal development through adulthood, each presenting unique vulnerabilities and health consequences. Early life exposures are particularly critical for long-term health outcomes, while adult exposures contribute to chronic disease development.

Figure 6.

Biological Matrix Applications for Multiclass Environmental Chemical Exposure Assessment.

Figure 7.

Environmental chemical exposure impacts health across life stages.

6.1. Blood and Plasma Analysis

6.1.1. Comprehensive Plasma Exposome Characterization

Comprehensive plasma exposome characterization enables simultaneous quantification of diverse chemical classes in blood samples, revealing the complex mixture of environmental contaminants present in human circulation [15,18,34,113,114,115]. Plasma samples were produced and analyzed using a previously established methodology combining untargeted and targeted chemical exposomics, with the chemical exposomics method being validated for 83 targeted analytes, including dietary chemicals, environmental contaminants, drugs, tobacco markers, and endogenous steroid hormones [35]. Among all plasma samples, 57 of the 83 target analytes were detected and quantified, with these substances belonging to 14 diverse chemical classes, including pesticides (organophosphate and neonicotinoid), flame retardants, PFAS, personal care products, pharmaceuticals, plasticizers, dietary substances, polycyclic aromatic compounds, a nicotine metabolite, and endogenous steroid hormones [35]. In each adult plasma (100 μL, n = 34), 28 analytes were identified and quantified across 10 chemical classes, with the quantification of per- and polyfluoroalkyl compounds externally verified using independent targeted analysis [34]. The methodologies have been effectively verified for the analysis of human blood concerning manmade phenolic compounds, with 21 analytes assessed in Swedish young adults, revealing the presence of synthetic phenolic antioxidants in numerous persons at elevated blood concentrations [20]. These comprehensive characterization studies demonstrate the feasibility of detecting complex chemical mixtures in plasma samples, providing a foundation for understanding systemic exposure patterns (Table 3) [15,34,114]. Recent applications of multiclass exposome methods have demonstrated direct quantitative relationships between chemical exposures and health outcomes through sophisticated statistical modeling approaches. Studies utilizing Bayesian kernel machine regression analysis have revealed significant associations between co-exposure to chemical mixtures and disease risk, with joint effects being statistically significant across exposure percentiles [28]. For instance, mixed-effect modeling has identified statistically significant exposome-metabolome interactions indicative of endocrine disruption, with positive correlations observed between testosterone and several PFAS compounds remaining significant in adjusted models [35]. Additionally, multiclass methods have enabled identification of significant positive associations between oxidative stress biomarkers and urinary biomarkers of exposure to various xenobiotics including flame retardants, pesticides, phthalates, and volatile organic compounds [29].

6.1.2. Longitudinal Exposure Assessment

Longitudinal exposure assessment in plasma samples reveals the temporal dynamics of chemical exposures and enables identification of stable versus variable exposure patterns over time, providing critical insights for exposure misclassification in epidemiological studies [116,117,118]. This study applied chemical exposomics to recurrent plasma samples of 46 healthy Swedish adults, each sampled 6 times over 2 years in a multiomics wellness profiling study [35]. Repeated sampling of identical individuals over time facilitated the identification of novel exposure types and uncovered both unusual and common co-exposures pertinent to precision health [35]. The majority of annotated chemicals in plasma (306 of 519 analytes) exhibited ICCs < 0.40, with the mean ICC substantially greater for endogenous metabolites (0.40) compared to the chemical exposome (0.30, Student’s t test, two-tailed, p < 0.001) [35]. The PCA scores plot, differentiated by S3WP participant ID, frequently clustered the six samples from each subject, suggesting a consistent stability of the target exposome throughout a two-year period [35]. These longitudinal studies underscore the significance of repeated assessments of the chemical exposome in epidemiological research to reduce exposure misclassification. In longitudinal multiomics studies, the exposome should be evaluated as frequently, or more frequently, than other biomolecular profiles [116,117,118].

6.2. Urine-Based Exposure Monitoring

6.2.1. Pediatric Population Studies

Pediatric population studies using urine-based exposure monitoring reveal unique exposure patterns in children and highlight the vulnerability of early life stages to environmental chemical exposures [32,119,120,121]. This research utilized the nationwide Environmental Impacts on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Cohort to evaluate chemical exposures in 201 children aged 2 to 4 years from 2010 to 2021 [32]. A total of 111 analytes from various chemical classes were concurrently measured in individual spot urinary specimens obtained from all children and their mother during pregnancy, with concentrations assessed between kid and prenatal maternal samples [32]. Of the 111 chemicals, 96 were identified in a minimum of five children, whereas 48 analytes were present in more than 50% of the children [32]. Thirty-four substances were universally identified (>90%), nine of which are absent from the United States national biomonitoring: triethyl phosphate, benzophenone-1, and six phthalate metabolites together with one alternative plasticizer [32]. After having demonstrated the feasibility of urine collection at this young age group, NHANES recently expanded its protocols to include the collection of urine specimens from children aged 3–5 years, beginning with the 2015–2016 survey period, for the measurement of nonpersistent chemical biomarkers [32]. These pediatric studies demonstrate widespread exposure to environmental chemicals in young children [32,119,121] and identify emerging contaminants not previously monitored in national surveillance programs [32].

6.2.2. Adult Exposure Patterns

Adult exposure patterns revealed through comprehensive urine analysis demonstrate the complexity of environmental chemical exposures in the general population and provide insights into sources and determinants of exposure variability [122,123,124,125,126]. The assay was validated to quantify 50 exposure biomarkers in urine, categorized into 7 chemical classes and 16 sub-classes, encompassing metabolites of 5 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), 12 personal care and consumer product chemicals (PCPs), 18 pesticides, 5 organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs), 4 tobacco alkaloids, 5 volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and 1 drug of abuse [12]. Human urine (0.2 mL) was augmented with isotope-labeled internal standards, enzymatically deconjugated, subjected to solid-phase extraction, and evaluated via high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry [12]. A multi-class analytical technique for measuring biomarkers of environmental chemical exposure and biological responses in human urine has been created and validated, facilitating the simultaneous study of 125 biomarkers spanning 10 chemical classes, consisting of parent compounds and/or metabolites of volatile organic compounds, tobacco smoke, psychosocial stress, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, phytoestrogens, phthalates and phthalate alternatives, pesticides, personal care and consumer product chemicals, oxidative stress, and flame retardants [29]. These adult exposure studies reveal significant inter-individual variability in chemical exposures and highlight age-related differences in exposure patterns and metabolic capacity [122,123,124].

6.3. Alternative Matrices for Exposure Assessment

6.3.1. Hair Analysis for Long-Term Exposure

Hair analysis provides a unique window into long-term exposure patterns, offering integrated exposure assessment over extended periods and revealing chronic exposure patterns not captured by traditional biomonitoring approaches [127,128,129]. A study assessed the correlation between multiple classes organic contaminants and sex steroid hormones using hair analysis in 196 healthy Chinese women between 25 and 45 years [33]. Hair analysis has been employed to investigate the impact of a combination of 19 pesticides from various chemical classes and a mix of 13 PAHs on hormones levels in female rats, revealing significant reductions in hair E2 concentration due to pesticide exposure and in hair thyroid hormone concentrations due to PAH exposure [33]. Hair measurements indicate average analyte levels over prolonged durations, potentially spanning several months, contingent upon the length of hair sections analyzed; hence, short-term exposure fluctuations exert no impact on the amounts identified in hair [33]. The outcomes of this study revealed that each hormone correlated with a combination of at least 10 analyzed pollutants, with hair E2 content linked to 19 contaminants, including propoxur, γ-hexachlorocyclohexane, fipronil, permethrin, prochloraz, mecoprop, and carbendazim [33]. Hair analysis demonstrates the potential for assessing chronic exposure patterns and their associations with endocrine disruption, providing insights into long-term exposure-health relationships (Figure 6) [33,128,130,131].

6.3.2. Cerebrospinal Fluid for Neurological Exposure

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis represents a specialized application for assessing chemical exposure to the central nervous system, providing direct evidence of blood–brain barrier penetration and potential neurological effects of environmental contaminants [132,133]. Cerebrospinal fluid is the most proximate biological fluid to the brain, with anomalies in this matrix directly correlating to pathological alterations in the brain (Figure 6) [36]. Notwithstanding its biological importance, the quantity of metabolomics/exposomics studies conducted on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples is limited due to the invasive and valuable nature of the sample (necessitating lumbar puncture) coupled with methodological obstacles, such as the absence of standardized materials and the fairly low levels of chemicals in CSF relative to other matrices like blood [36]. The 28 pollutants analyzed displayed median values varying from the LOD to 10.5 ng/mL in blood and from LOD to 1.2 ng/mL in CSF. Four PFAS compounds were found in at least 60% of cerebrospinal fluid samples (n ≥ 108), namely perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), 6:2 chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonate (6:2 Cl-PFESA), and perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), with median concentrations varying from 0.001 to 0.042 ng/mL [36]. Research indicates that several environmental pollutants can penetrate the blood- brain barrier into the brain’s central nervous system (CNS), thereby impairing neuronal development and functions (Figure 2) [36]. CSF analysis provides critical insights into central nervous system exposure to environmental chemicals and demonstrates that molecular size is a key determinant of blood–brain barrier penetration, with important implications for neurotoxicity assessment [132,133].

7. Method Validation and Quality Assurance

7.1. Analytical Performance Criteria

7.1.1. Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Achievement of exceptional sensitivity with detection limits in the sub-ng/mL range represents a critical requirement for multiclass exposome methods, enabling quantification of environmental contaminants at levels relevant for human health risk assessment [12,14,17,23,62]. For the majority of chemicals, the limits of detection and quantitation (LODs/LOQs) were within the range of 0.001–0.1 ng/mL [16]. The detection limits varied between 0.01 and 1.0 ng/mL in urine, with most of them being ≤0.5 ng/mL (42 out of 50) [12]. LVI significantly improved technique sensitivity, achieving quantification limits below 10 ng L−1 for 93 out of 102 CECs across diverse water matrices [39]. The robustness of the method was assessed, showing adequate extraction recovery and matrix effects (SSE) between 60 and 130%, inter-/intra-day precision (RSD) under 30%, and remarkable sensitivity (limit of detection, 0.015–50 pg/mL) for 60–80% of the analytes throughout the examined matrices [24]. The detection limits for human estrogens and xenobiotics varied from 0.01 to 5.7 ng/mL, with a median of 0.08 ng/mL in the solvent. In the matrix, the median limit of detection rose to 0.7 ng/mL in urine and 0.5 ng/mL in plasma, possibly attributable to matrix effects and interferences [22]. The technique detection limit ranged from 0.003 to 0.838 ng/mL, while the limit of quantification (LOQ) spanned 0.009 to 2.794 ng/mL. The accuracy of all substances was from 85% and 115%, while the precision was below 15% [13]. The overall technique sensitivity was rated as excellent to satisfactory for the majority of targeted analytes, with a median MLOQ of 0.05 ng/mL. Specifically, 62% of analytes exhibited MLOQ values ranging from 0.01 to 0.1 ng/mL, 34% from 0.2 to 1 ng/mL, and a mere 4% from 1 to 5 ng/mL [34]. These exceptional sensitivity achievements enable detection of environmental exposures at concentrations that are toxicologically relevant and support comprehensive characterization of the human exposome (Table 3) [12,14,17,23,62].

7.1.2. Precision and Accuracy Assessment

Rigorous assessment of precision and accuracy across all target analytes ensures reliable quantitative performance and demonstrates method robustness for large-scale epidemiological applications [134,135]. Analytical precision, quantified as the relative standard deviation of intra- and inter-batch variability, was less than 20% [12]. The 1 ng/mL spiking quality control pool exhibited analyte recoveries between 83% and 109% efficiency, with a median of 97% efficiency [12]. The inter-batch precision (range, median) exhibited a relative standard deviation (RSD) of 0–18% (3.5%) and a coefficient of variation (CV) of 2–19% (9.5%) [12]. Quality assurance/control (QA/QC) tests indicated that analyte recoveries from spiking tests varied between 72% and 128%, matrix effects ranged from 74% to 119%, inter-batch coefficients of variation were below 20% (with 50 samples per batch), and there was no evidence of background contaminants in field and procedural blanks (one blank processed alongside ten samples) for the target analytes [38]. The approach exhibited adequate recovery (81–120%) for the majority of the added analytes, with acceptable relative standard deviations (<20%) across three spiking levels [27]. The accuracy for all compounds was between 85% and 115%, and the precision was less than 15% [13]. The relative standard deviations for intra- and inter-day precision ranged 0.1–16.4% and 0.3–18.9% for plasma, while for urine, they ranged from 0.1 to 16.1% and from 1.5 to 19.6%, respectively, remaining below the 20% acceptability threshold set by the FDA [14]. These precision and accuracy results demonstrate that multiclass methods can achieve performance standards suitable for quantitative exposome research while maintaining reliability across hundreds of target analytes (Table 3) [134,135].

7.2. Matrix Effect Evaluation

Comprehensive evaluation of matrix effects across diverse biological and environmental matrices is essential for ensuring accurate quantification and understanding the impact of sample composition on analytical performance [136,137,138,139,140,141]. Matrix effects provide significant problems for LC-MS analysis, arising from the co-elution of sample matrices with analytes during liquid chromatography separation [39]. The matrix effects from urine were more pronounced than those from the sewage effluent, likely due to the higher concentrations of inorganic salts, urea, and creatinine present in urine matrices [39]. Matrix effects were mitigated through the utilization of matrix-matched calibration standard curves and stable isotope-labeled internal standards [12]. Signal suppression or enhancement was evaluated as the ratio of the slope of the calibration curve generated in a urine matrix to that of a curve developed in reagent-based water [12]. The SSE of the 50 analytes in this investigation ranged from 0.8 to 1.2, a ratio that was deemed suitable [12]. The majority of veterinary drugs, pesticides, and antibiotics (69%) showed matrix effects within a range of 50–140% [27]. The matrix effects were quantified, ranging from −18% to 63%, indicating either suppression or augmentation of ESI-MS/MS signals for the target compounds. To alleviate such matrix effects, structurally analogous and stable isotope- labeled compounds were utilized as internal standards [30]. Matrix effects at concentrations of 0.5 and 5 ng/mL were predominantly minimal for the phospholipid-free matrix, exhibiting medians of 91% and 107%, respectively [34]. Systematic evaluation of matrix effects demonstrates that multiclass methods can achieve acceptable performance across diverse sample types through appropriate use of internal standards and matrix-matched calibration approaches [136,137,138,139,140,141].

7.3. Reference Materials and Standardization

The use of certified reference materials and involvement in proficiency testing programs provide external validation of technique efficacy and guarantees traceability and comparability of results among laboratories and research [62,142,143,144]. The outcomes from the optimized multi-class technique were validated in formal international proficiency testing programs [12]. The procedure performed satisfactorily; the submitted findings generally fell within the tolerance range of the proficiency testing reference values, and were therefore deemed validated [12]. Additionally, standard reference materials (SRMs) (SRM 3672 [145] and SRM 3673 [146]; National Institute of Standards and Technology) and three aliquots each of HHEAR urine quality control (QC) pools A and B were analyzed in every batch [32]. The SRMs contained 20 analytes, but mean recoveries were calculated for 19, excluding one analyte with a spiked level below the LOD, ranging from 70 to 129% [32]. The testing of SRM 1957 [147] indicated that the mean concentrations of selected compounds (PFAS) varied between 89.6% to 110.2% in accordance with established levels, thereby confirming the analytical precision [28]. Six analytes having certified reference values in NIST SRM 3672 (Organic Contaminants in Smokers’ Urine) were identified and measured, exhibiting a relative error of less than 20% compared to the reference value for all analytes [22]. The laboratory engages in external proficiency testing programs, including the German External Quality Assessment Scheme (G-EQUAS) for biological material analyses and the Organic Substances in Urine Quality Assessment Scheme (OSEQAS) administered by the Centre de Toxicologie du Quebec in Canada, to validate method performance and ensure result quality [12,29]. The successful performance in proficiency testing programs and accurate quantification of certified reference materials demonstrate the reliability and traceability of multiclass analytical methods, providing confidence in their application to large-scale exposome studies and regulatory monitoring programs [62,142,143,144]. Standardization efforts through proficiency testing programs and certified reference materials represent essential components for ensuring data quality and comparability across laboratories conducting multiclass exposome analysis. The successful performance in international proficiency testing programs demonstrates method reliability and enables harmonized data integration across different analytical platforms and study populations. These standardization approaches are particularly critical for large-scale exposome-wide association studies where data from multiple laboratories must be integrated to achieve sufficient statistical power and population representation for meaningful health risk assessment.

7.4. Practical Solutions for Standardizing Methods Between Different Laboratories

Standardization of multiclass analytical methods across laboratories requires a comprehensive approach that encompasses multiple quality assurance elements to ensure reproducible and comparable results. Participation in formal international proficiency testing programs represents a cornerstone of method standardization, as demonstrated by successful qualification of multiclass methods in established programs where submitted results typically fall within tolerance ranges of reference values, thus validating analytical performance. Implementation of certified reference materials provides essential benchmarks for method validation, with studies showing accurate quantification of target analytes in standard reference materials such as SRM 1957 for PFAS analysis and SRM 3672 for organic contaminants in smokers’ urine. Standardized quality control protocols should include the regular analysis of quality control pools and standard reference materials in each analytical batch. Established acceptance criteria should be set for recovery (for example, 70–130%), matrix effects (for example, 70–130%), and inter-batch coefficients of variation (for example, <20%). Laboratory participation in external quality assessment schemes such as the German External Quality Assessment Scheme (G-EQUAS) for biological materials and the Organic Substances in Urine Quality Assessment Scheme (OSEQAS) and AMAP Ring Test for Persistent Organic Pollutants in Human Serum (AMAP) conducted by the Centre de Toxicologie du Quebec provides ongoing validation of method performance and ensures result quality. Adoption of standardized sample preparation protocols utilizing consistent extraction methods, such as optimized solid-phase extraction with 96-well plates or standardized liquid–liquid extraction procedures with defined solvent compositions and extraction cycles, ensures reproducible recovery across laboratories. Implementation of uniform analytical parameters including standardized multiple reaction monitoring transitions, optimized collision energies, and consistent chromatographic conditions enables comparable sensitivity and selectivity across different laboratory platforms. Establishing common validation criteria that address the unique challenges of multiclass methods is essential. This includes defining acceptable ranges for extraction recovery (for example, 70–130%), precision (for example, RSD < 30%), and sensitivity requirements (such as sub-ng/mL detection limits). These criteria provide consistent performance benchmarks.

8. Health Implications and Exposure-Response Relationships

Multiclass exposome approaches have enabled groundbreaking exposome-wide association studies that identify environmental chemical risk factors for human health outcomes, demonstrating the critical importance of comprehensive chemical exposure assessment in understanding disease etiology. A notable example is the nested gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) case–control study where multiclass analysis of 325 chemicals revealed significant associations between chemical mixture exposure and GDM risk [28]. The Bayesian kernel machine regression analysis revealed a robust linear positive correlation between co-exposure to 33 chemicals and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). The joint effect was statistically significant when exposure levels of all chemicals were between the 25th and 75th percentiles. In comparison to the 50th percentile, the predicted probit of GDM prevalence at the 75th percentile indicated a 92% increase [28]. The research determined that significant contributions to the combined impacts originated from PFAS, as indicated by the group posterior inclusion probability (groupPIP) of 1.00, synthetic antioxidants with groupPIP of 1.00, and non-PAE plasticizers with groupPIP of 0.80, with key chemicals including PFHxS with conditional PIP (condPIP) of 0.64, DPG with condPIP of 1.00, and DBF with condPIP of 0.91 driving the joint effect [28]. Similarly, hair analysis studies in Chinese women revealed that exposure to multiclass organic contaminants correlated with altered sex steroid hormone levels, with each hormone linked to a mixture of at least 10 pollutants. Notably, hair E2 concentration was associated with 19 xenobiotics, including propoxur, γ-hexachlorocyclohexane, fipronil, permethrin, prochloraz, mecoprop, and carbendazim [33]. Further ExWAS applications encompass the CIRCA CHEM chrononutrition trial, which expanded from two pesticide biomarkers to 125 biomarkers of exposure to food contaminants utilizing exposomics tools. This study unveiled significant positive correlations between oxidative stress biomarkers HNEMA and F2A8IP and a range of urinary biomarkers indicative of exposure to various xenobiotics, which includes VOCs, flame retardants, phthalates, pesticides, tobacco metabolites, PAHs, and phytoestrogens [29]. Longitudinal plasma exposome studies demonstrated mixed-effect modeling with statistically significant interactions between the exposome and metabolome, suggesting endocrine disruption. Positive correlations were identified between testosterone and various PFAS, including perfluorononanoate, linear PFOS, and perfluorodecanoate in females, with these associations maintaining statistical significance in adjusted models accounting for baseline age and BMI [35]. These ExWAS examples illustrate how multiclass analytical approaches enable the identification of complex exposure-health relationships that would be missed by traditional single-analyte methods, providing critical evidence for environmental health risk assessment and regulatory decision-making while supporting the development of precision medicine approaches for environmental health protection.

9. Current Challenges and Limitations

9.1. Analytical Challenges

9.1.1. Chemical Diversity and Physicochemical Properties