Comparison of Metabolomic Signatures Between Low and Heavy Parasite Burden of Haemonchus contortus in Meat Goats Fed with Cynodon dactylon (Bermudagrass) and Crotalaria juncea L. (Sunn Hemp)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.2. Feces Extraction for 1H-NMR and LC/MS Analysis

2.3. 1H-NMR Sample Preparation and Data Collection

2.4. 1H-NMR Data Processing

2.5. LC/MS Sample Preparation

2.6. LC/MS Data Collection and Processing

3. Results

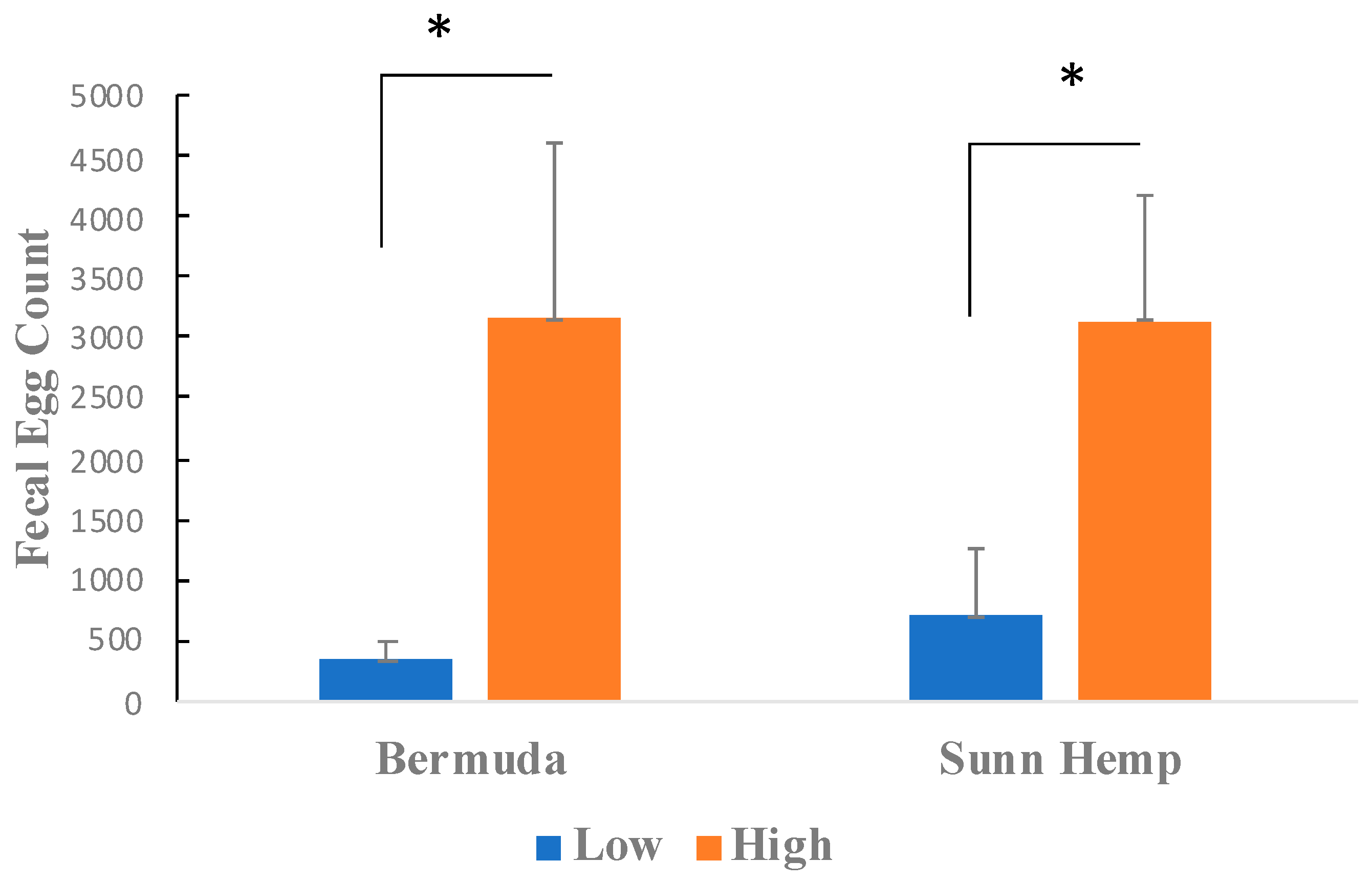

3.1. Bermudagrass and Sunn Hemp FEC Measurements

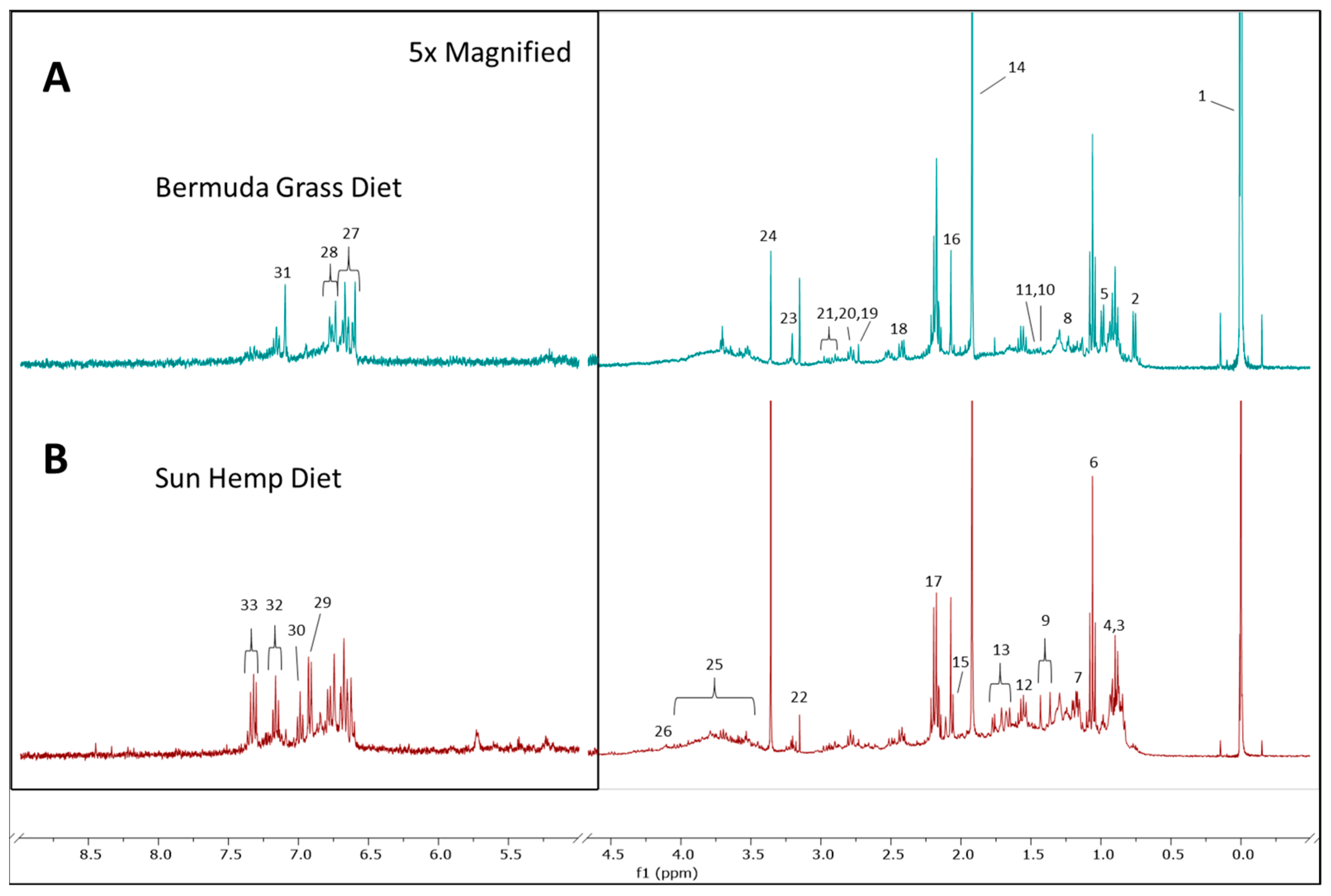

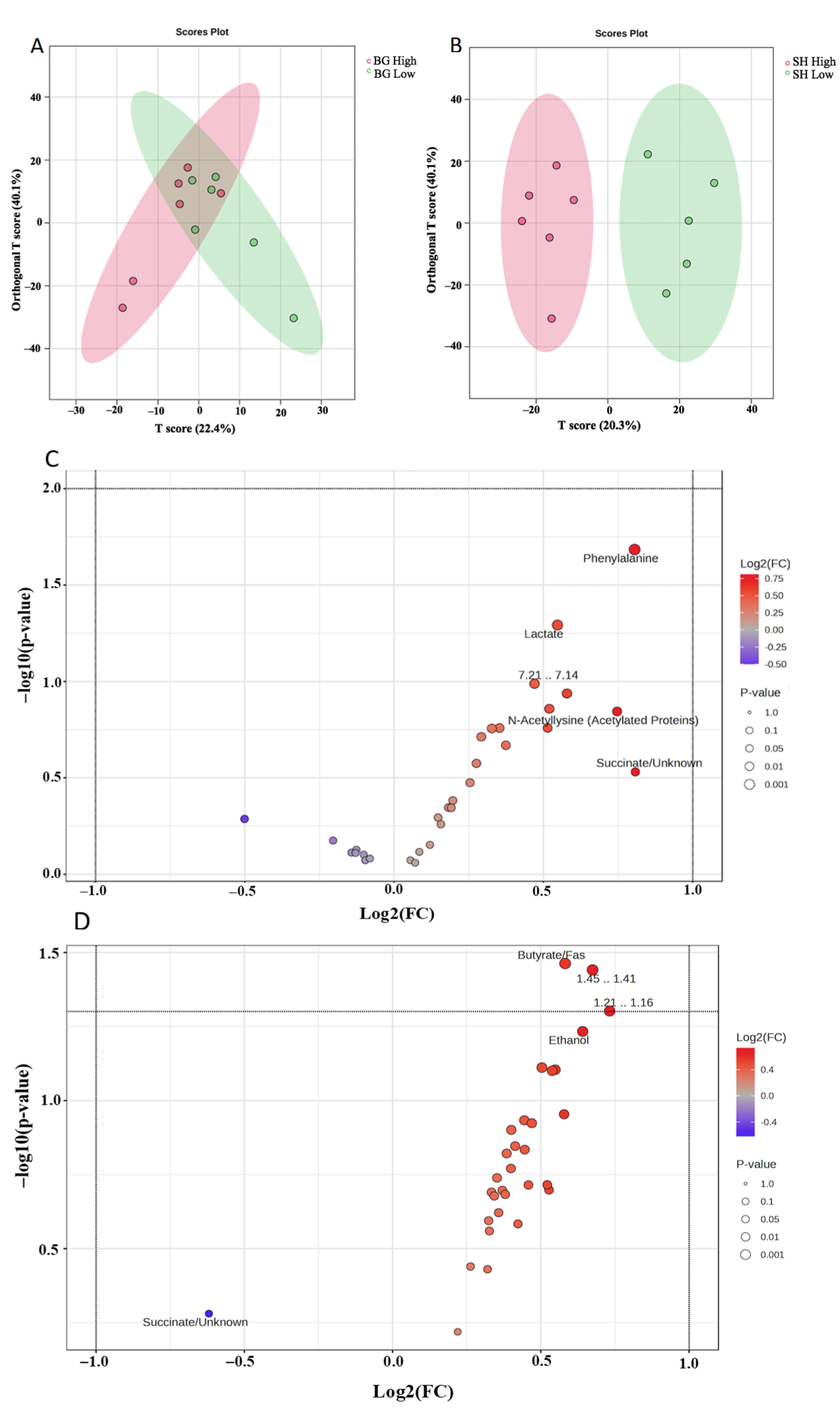

3.2. Metabolomic Profile for Goat Feces

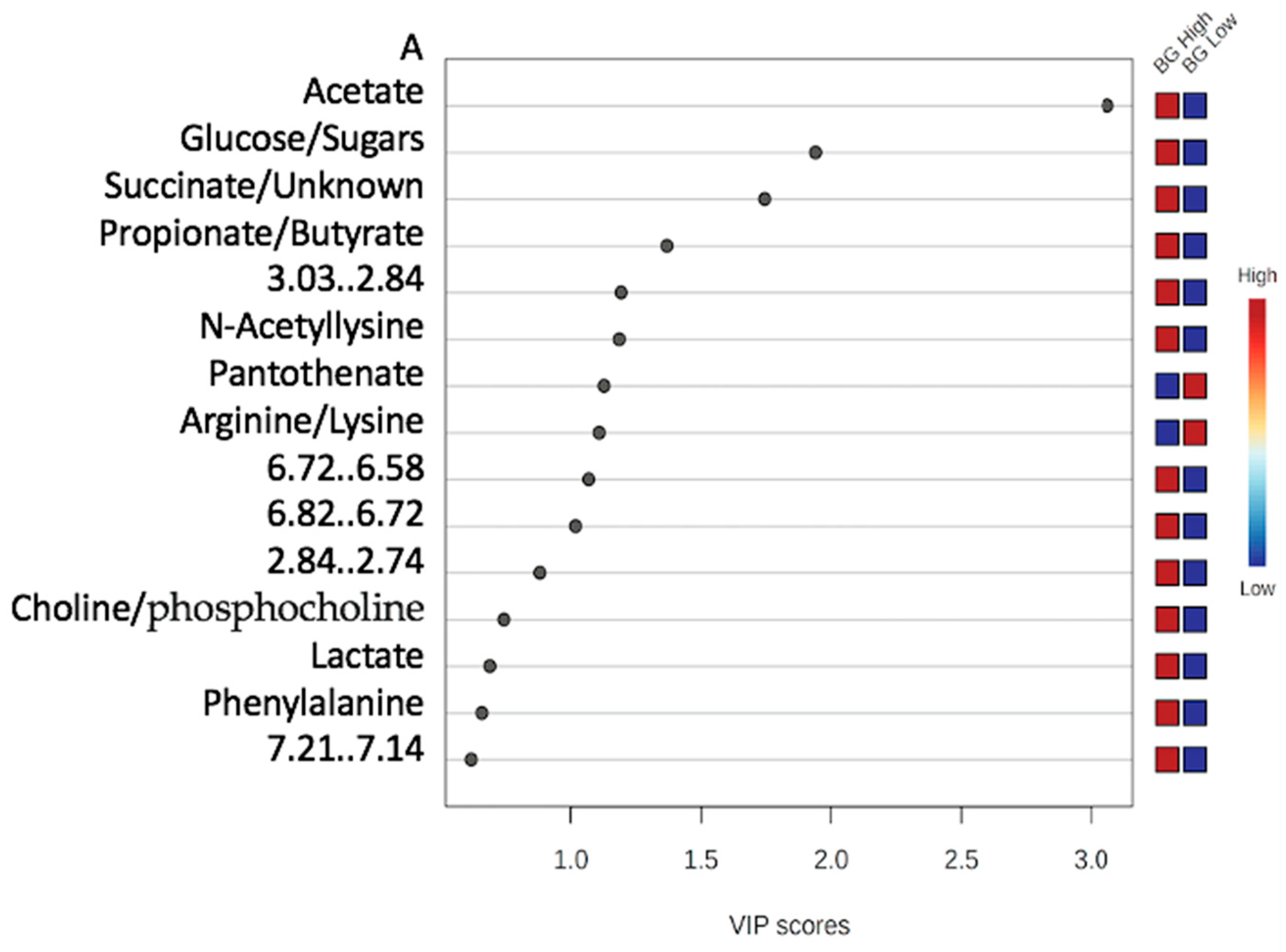

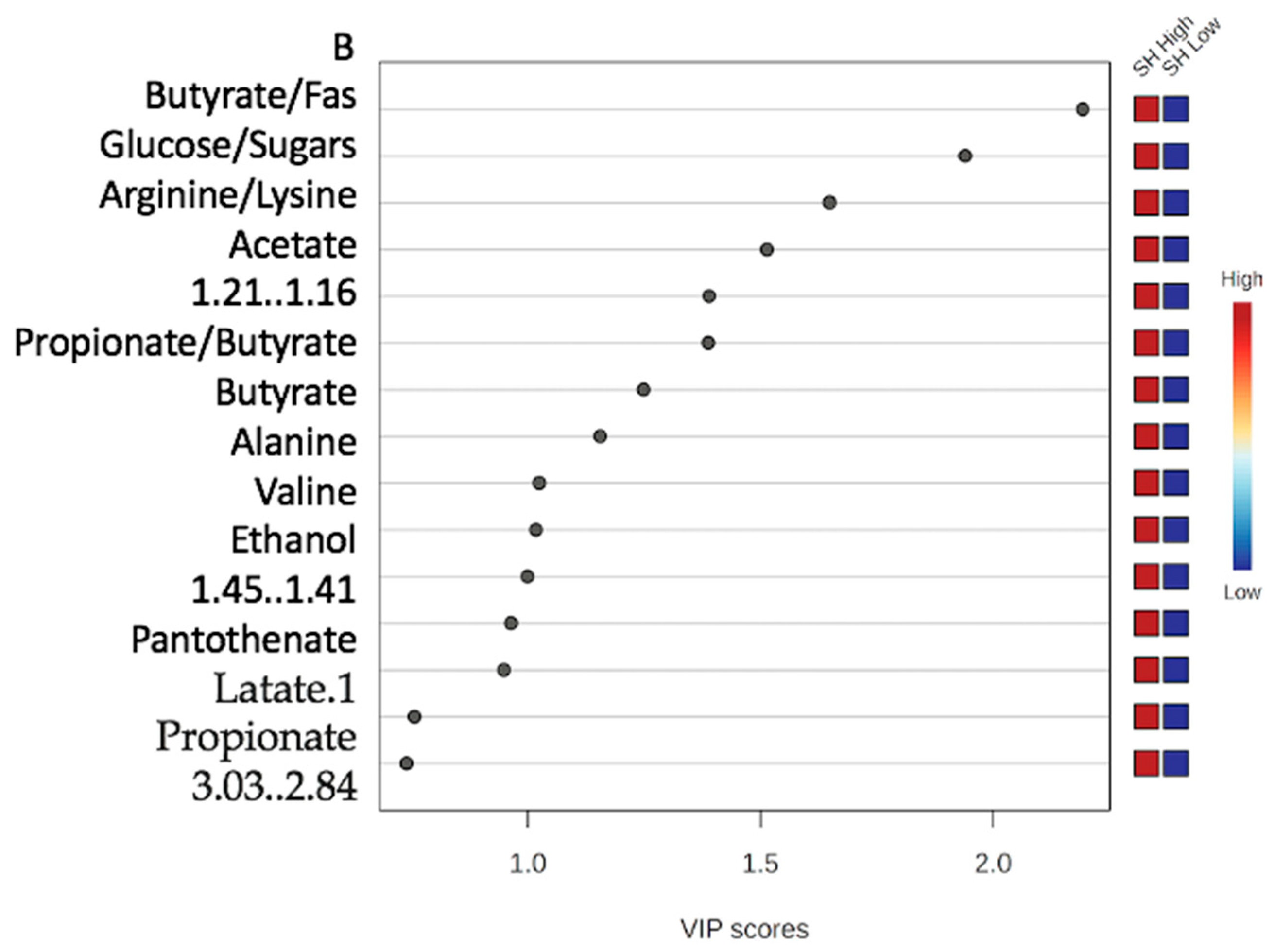

3.2.1. Variable Importance Plot (VIP)

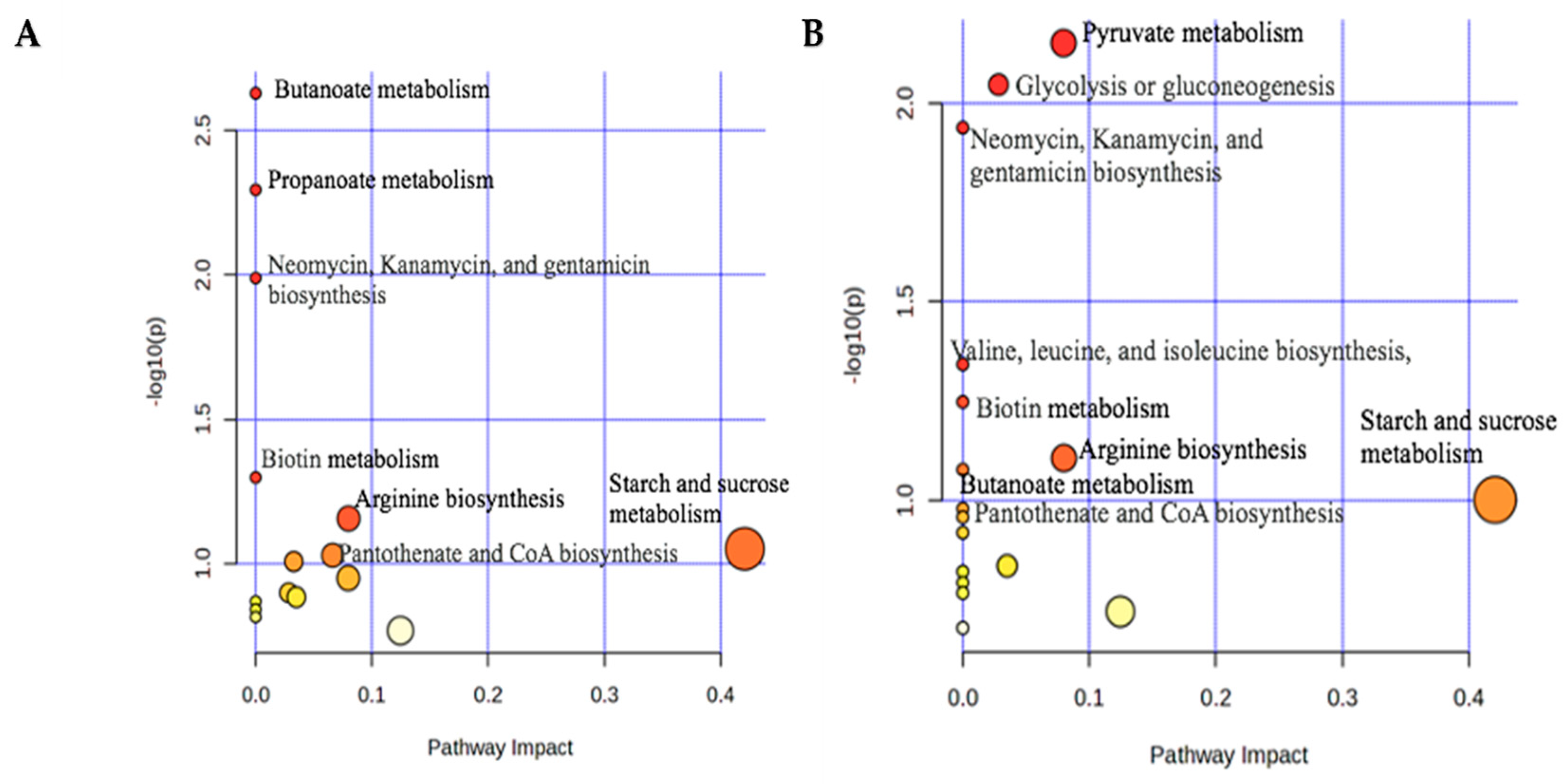

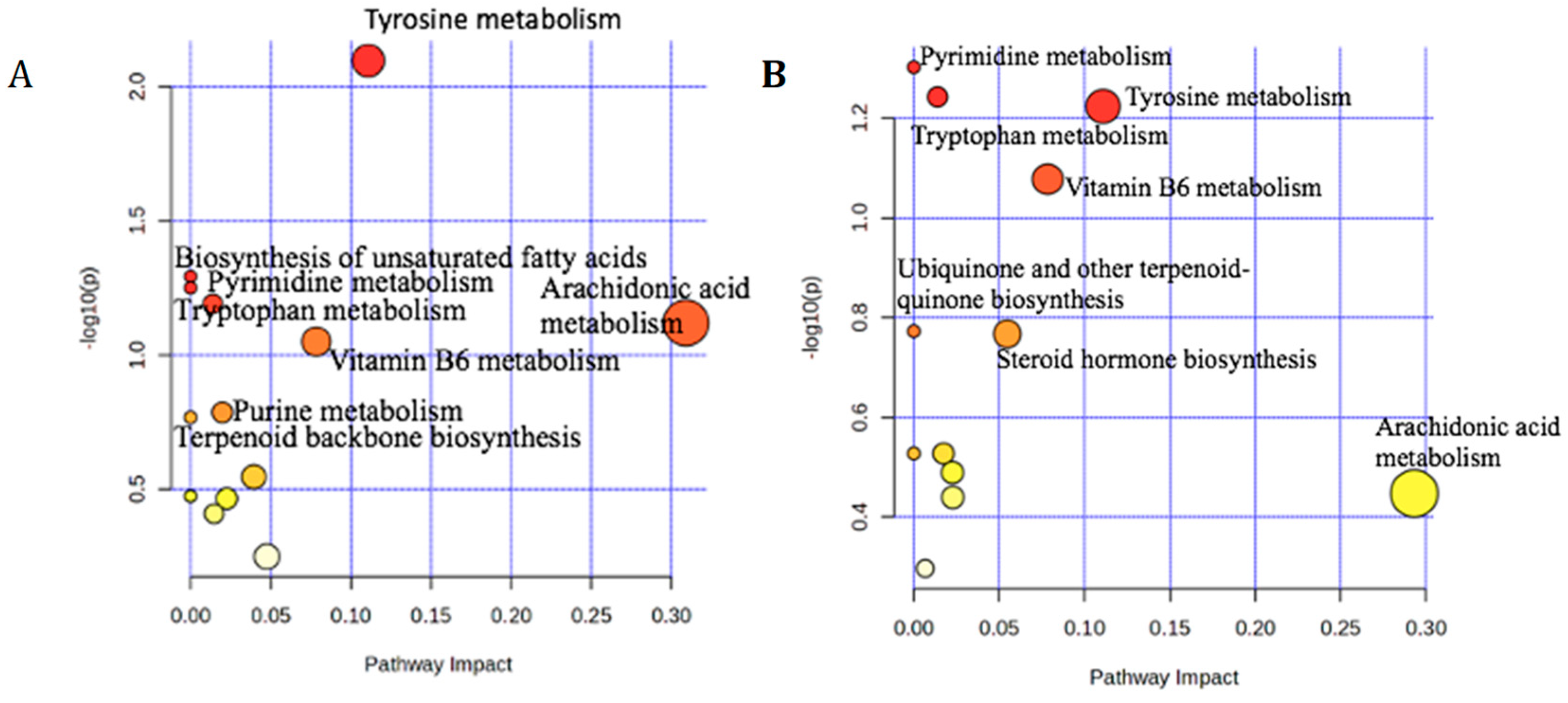

3.2.2. Pathway Analysis for 1H-NMR

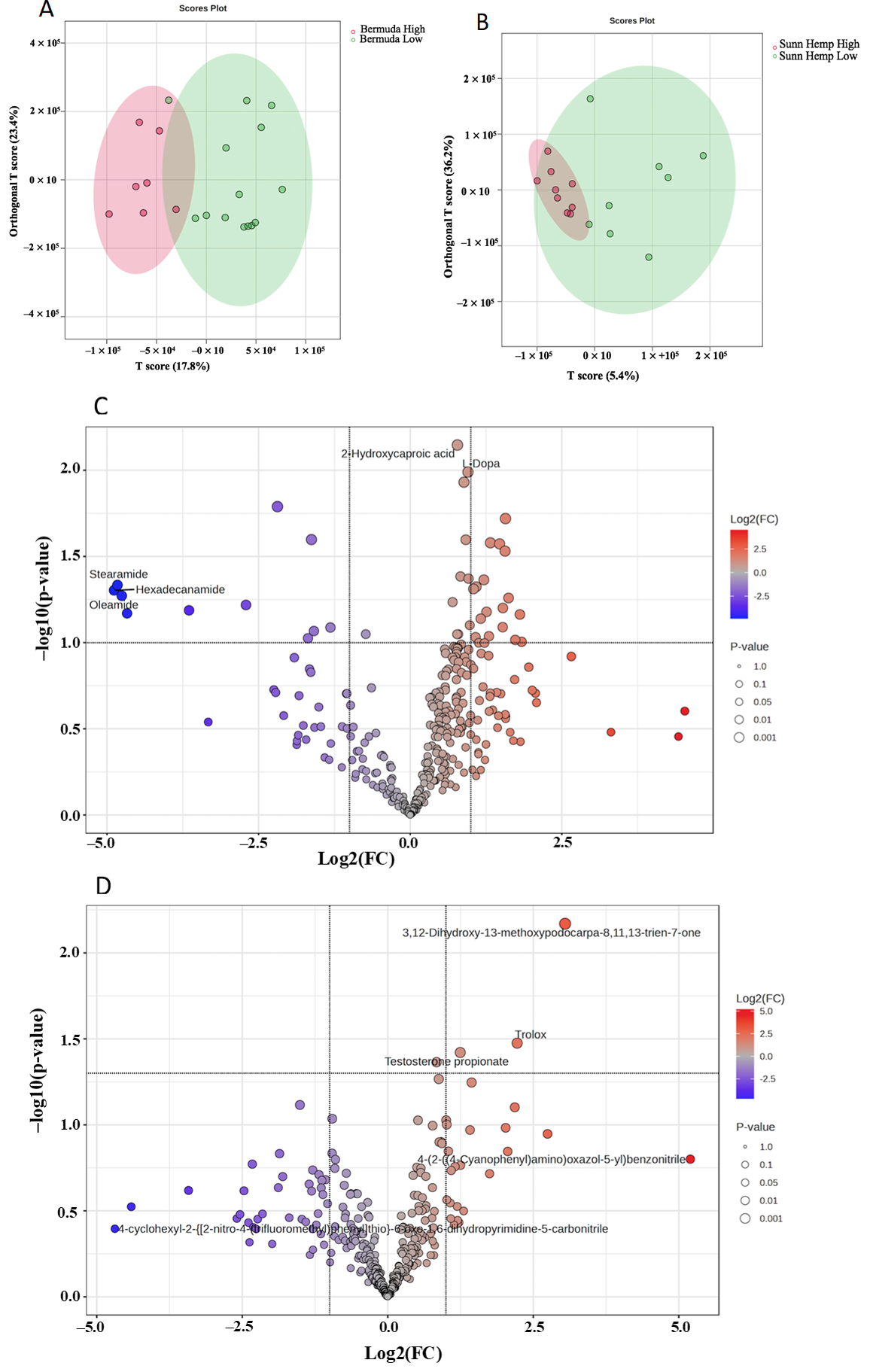

3.2.3. Fecal Metabolomics Profile for LC/MS

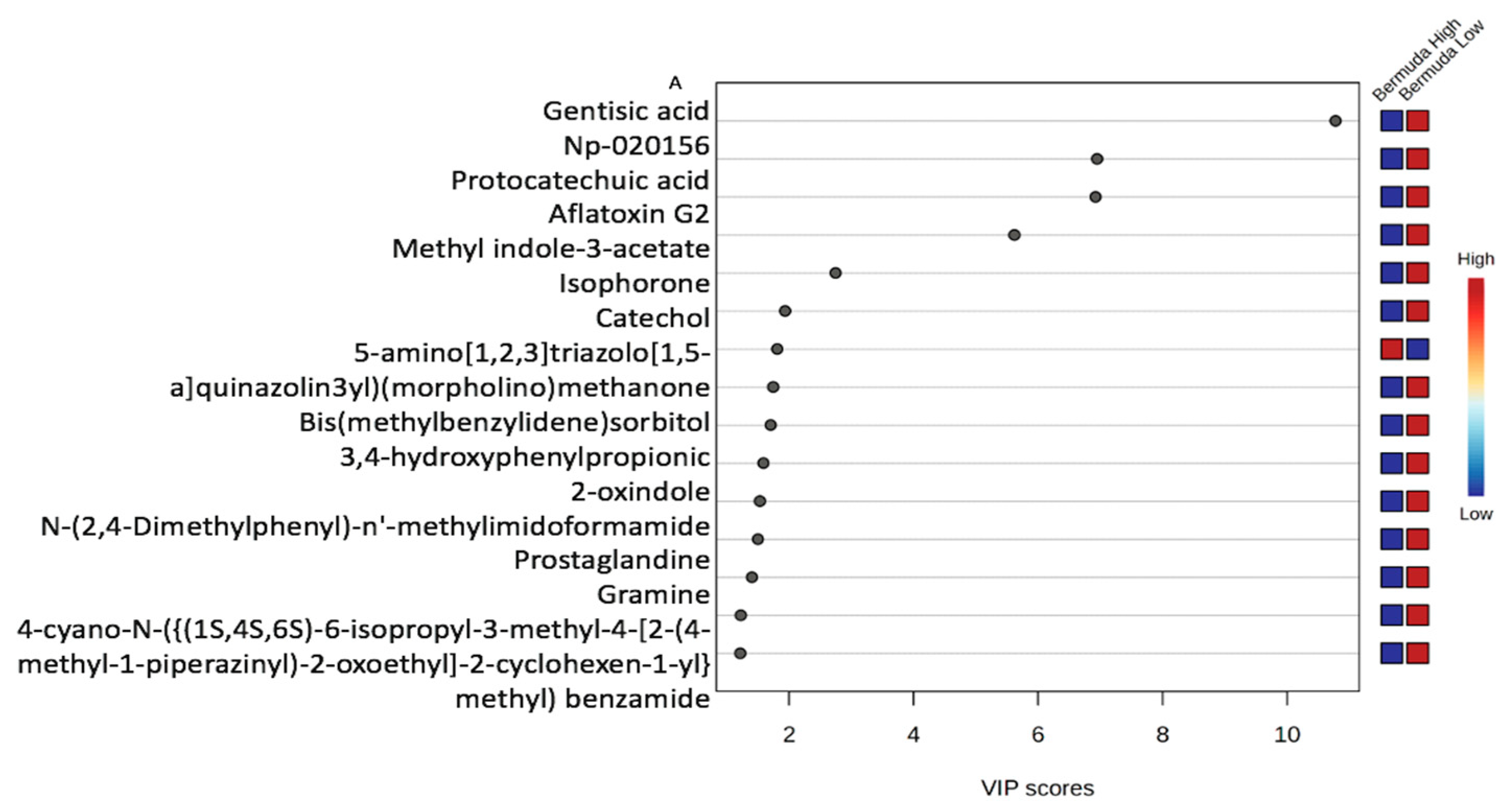

3.2.4. Variable Importance Plot (VIP) and Metabolites

3.2.5. Pathway Analysis for LC-MS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matysik, S.; Ray, C.I.L.; Liebisch, G.; Claus, S.P. Metabolomics of fecal samples: A practical consideration. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 57, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarate, J.J.; Ogunade, M.A.; Arriola, I.M.; Adesogan, K.G. Tropical plant supplementation effects on the performance and parasite burden of goats. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 31, 208. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Kell, P.; Scherrer, D.; Dietzen, D.J.; Vite, C.H.; Berry-Kravis, E.; Davidson, C.; Cologna, S.M.; Porter, F.D.; Ory, D.S.; et al. Accumulation of alkyl-lysophosphatidylcholines in Niemann-Pick disease type C1. J. Lipid Res. 2024, 65, 100600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gines, B.R.; Collier, W.E.; Abdalla, M.A.; Yehualaeshet, T. Metabolomic Responses of Yersinia Enterocolitica Under Acid Stress. Metabolomics 2021, 38, 30271–30280. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H.; McConville, M.; Loukopoulos, P. Metabolomics in the study of spontaneous animal diseases. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2020, 32, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S.A.; Terrill, T.H.; Miller, J.E.; Kouakou, B.; Kannan, G.; Kaplan, R.M.; Mosjidis, J.A. Sericea lespedeza hay acts as a natural deworming agent against gastrointestinal nematode infection in goats. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 139, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommuru, D.S.; Whitley, N.C.; Miller, J.E.; Mosjidis, J.A.; Burke, J.M.; Gujja, S.; Terrill, T.H. Effect of sericea lespedeza leaf meal pellets on adult female Haemonchus contortus in goats. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 207, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.R. On-Farm Evaluation and Use of Sunn Hemp (Crotalaria juncea L.) Legume to Improve Sustainable Meat Goat Production and Health in the Southern USA. Final Report for OS14-088—SARE Grant Management System. 2018. Available online: https://projects.sare.org/project-reports/os14-088/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Besier, R.B.; Kahn, L.P.; Sargison, N.D.; Van Wyk, J.A. Diagnosis, treatment, and management of Haemonchus contortus in small ruminants. Adv. Parasitol. 2016, 93, 181–238. [Google Scholar]

- Martias, C.; Gatien, J.; Roch, L.; Baroukh, N.; Mavel, S.; Lefèvre, A.; Nadal-Desbarats, L. Analytical methodology for a metabolome atlas of goat plasma, milk, and feces using 1H-NMR and UHPLC-HRMS. Metabolites 2021, 11, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammack, K.M.; Austin, K.J.; Lamberson, W.R.; Conant, G.C.; Cunningham, H.C. Ruminant nutrition symposium: Tiny but mighty—The role of the rumen microbes in livestock production. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 752–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Cao, Z.; Ji, S.; Zhang, H. Effect of dietary forage-to-concentrate ratios on dynamic profile changes and interactions of ruminal microbiota and metabolites in Holstein heifers. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Laghi, L. Characterization of yak common biofluids metabolome by means of proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Metabolites 2019, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-H.; Nuria, C.; Mihai, V.C.; Mette, S.H. Untargeted metabolomics as a tool to assess the impact of dietary approaches on pig gut health: A review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 16, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Goldansaz, S.A.; Guo, A.C.; Sajed, T.; Steele, M.A.; Plastow, G.S.; Wishart, D.S. Livestock metabolomics and the livestock metabolome: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batchu, P.; Terrill, T.H.; Kouakou, B.; Estrada-Reyes, Z.M.; Kannan, G. Plasma metabolomic profiles as affected by diet and stress in Spanish goats. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, V.; Farimani, M.M.; Fathi, F.; Ghassempour, A. A targeted metabolomics approach toward understanding metabolic variations in rice under pesticide stress. Anal. Biochem. 2015, 478, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Yang, Z.; Yang, F.; Yang, Y.; Laghi, L. Metabolomic analysis of multiple biological specimens (feces, serum, and urine) by 1H-NMR spectroscopy from dairy cows with clinical mastitis. Animals 2023, 13, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, B.; Wang, R.; Hu, J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Analysis of fecal microbiome and metabolome changes in goats with pregnancy toxemia. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gines, B.R.; Collier, W.E.; Abdalla, M.A.; Yehualaeshet, T. Influence of metabolite extraction methods on 1H-NMR-based metabolomic profiling of Enteropathogenic yersinia. Methods Protoc. 2018, 1, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malheiros, J.M.; Correia, B.S.B.; Ceribeli, C.; Cardoso, D.R.; Colnago, L.A.; Junior, S.B.; de Almeida Regitano, L.C. Comparative untargeted metabolome analysis of ruminal fluid and feces of Nelore steers (Bos indicus). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, A.; Wang, W.; Peng, W.; Mao, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, H. Analysis of fecal microbiome and metabolome changes in goats when consuming a lower-protein diet with varying energy levels. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Ara, I.; Faizi, S.; Mahmood, T.; Siddiqui, B.S. Phenolic tricyclic diterpenoids from the bark of Azadirachta indica. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 3903–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Deng, S.; Lu, N.; Yao, W.; Xia, D.; Tu, W.; Gan, Y. Fecal microbial composition associated with testosterone in the development of Meishan male pigs. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1257295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangu, A.; Ashrafi, A.M.; Sýs, M.; Arbneshi, T.; Metelka, R.; Adam, V.; Richtera, L. Determination of trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity in berries using an amperometric tyrosinase biosensor based on multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimratch, S.; Thammapat, P.; Mungkunkamchao, T. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in flowers and seeds of sunn hemp. Prawarun Agric. J. 2022, 19, 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante, F.M.L.; Almeida, I.V.; Düsman, E.; Mantovani, M.S.; Vicentini, V.E.P. Cytotoxicity, mutagenicity, and antimutagenicity of gentisic acid on HTC cells. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 41, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiplakou, E.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Liapis, K.; Haroutounian, A.S.; Zervas, G. Determination of mycotoxins in feedstuffs and ruminant׳ s milk using an easy and simple LC–MS/MS multiresidue method. Talanta 2014, 130, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R.; Rai, R.V.; Karim, A.A. Rai, and Abd A. Karim. Mycotoxins in food and feed: Present status and future concerns. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010, 9, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskandari, M.H.; Pakfetrat, S. Aflatoxins and heavy metals in animal feed in Iran. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2014, 7, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga-Torres, B.; Ron, L.; Gomez, C. Dietary aflatoxin B1-related risk factors for the presence of aflatoxin M1 in raw milk of cows from Ecuador. Open Vet. J. 2022, 12, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfuz, S.; Mun, H.S.; Dilawar, M.A.; Ampode, K.M.B.; Yang, C.J. Potential role of protocatechuic acid as a natural feed additive in farm animal production. Animals 2022, 12, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; El Khoury, S.; Pérez-Carrascal, O.M.; DeSousa, C.; Jung, D.K.; Bohley, S.; Shapira, M. Gut microbiome remodeling provides protection from an environmental toxin. iScience 2025, 28, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Wan, P.; Cheng, L.; Yan, X. Integrated microbiome and metabolome analysis reveals altered gut microbial communities and metabolite profiles in dairy cows with subclinical mastitis. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metabolite | Range (ppm) |

|---|---|

| TSP | −0.09–0.1 |

| Unknown | 0.68–0.8 |

| Butyrate acid/FA signals | 0.81–0.93 |

| Panthotenic acid | 0.93–0.96 |

| Valine | 0.97–1.01 |

| Propionate | 1.07–1.08 |

| Unknown | 1.13–1.16 |

| Ethanol | 1.16–1.21 |

| Lactate | 1.32–1.36 |

| Unknown | 1.41–1.45 |

| Alanine | 1.44–1.5 |

| Butyrate | 1.52–1.6 |

| Arginine/Lysine/Unknown | 1.61–1.85 |

| Acetic Acid | 1.86–1.94 |

| N-acetyllysine acetylated proteins | 1.98–2.02 |

| N-acetyl/proteins/Carbohydrates | 2.04–2.09 |

| Propionate/Butyrate | 2.13–2.24 |

| Succinate/Unknown | 2.38–2.45 |

| Unknown | 2.71–2.74 |

| Unknown | 2.74–2.84 |

| Unknown | 2.84–3.04 |

| Dimethyl sulfone | 3.14–3.17 |

| Choline, phosphocholine/carnitine | 3.17–3.26 |

| Glucose/sugar | 3.4–3.9 |

| Lactate | 4.07–4.17 |

| Unknown | 6.58–6.72 |

| Unknown | 6.72–6.82 |

| Tyrosine | 6.89–6.96 |

| Unknown | 7.07–7.14 |

| Unknown | 6.96–7.05 |

| Unknown | 7.14–7.21 |

| Phenylalanine | 7.28–7.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hilaire, M.; Gines, B.; Collier, W.E.; Wang, H.; Chaudhary, S.; Kanyi, V.; Abdo, H.; Ismael, H.; St. Preux, E.C.; Boersma, M.; et al. Comparison of Metabolomic Signatures Between Low and Heavy Parasite Burden of Haemonchus contortus in Meat Goats Fed with Cynodon dactylon (Bermudagrass) and Crotalaria juncea L. (Sunn Hemp). Metabolites 2025, 15, 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15110741

Hilaire M, Gines B, Collier WE, Wang H, Chaudhary S, Kanyi V, Abdo H, Ismael H, St. Preux EC, Boersma M, et al. Comparison of Metabolomic Signatures Between Low and Heavy Parasite Burden of Haemonchus contortus in Meat Goats Fed with Cynodon dactylon (Bermudagrass) and Crotalaria juncea L. (Sunn Hemp). Metabolites. 2025; 15(11):741. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15110741

Chicago/Turabian StyleHilaire, Mariline, Brandon Gines, Willard E. Collier, Honghe Wang, Santosh Chaudhary, Vivian Kanyi, Heba Abdo, Hossam Ismael, Erick Cathsley St. Preux, Melissa Boersma, and et al. 2025. "Comparison of Metabolomic Signatures Between Low and Heavy Parasite Burden of Haemonchus contortus in Meat Goats Fed with Cynodon dactylon (Bermudagrass) and Crotalaria juncea L. (Sunn Hemp)" Metabolites 15, no. 11: 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15110741

APA StyleHilaire, M., Gines, B., Collier, W. E., Wang, H., Chaudhary, S., Kanyi, V., Abdo, H., Ismael, H., St. Preux, E. C., Boersma, M., & Min, B. R. (2025). Comparison of Metabolomic Signatures Between Low and Heavy Parasite Burden of Haemonchus contortus in Meat Goats Fed with Cynodon dactylon (Bermudagrass) and Crotalaria juncea L. (Sunn Hemp). Metabolites, 15(11), 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15110741