Economic, Non-Economic and Critical Factors for the Sustainability of Family Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

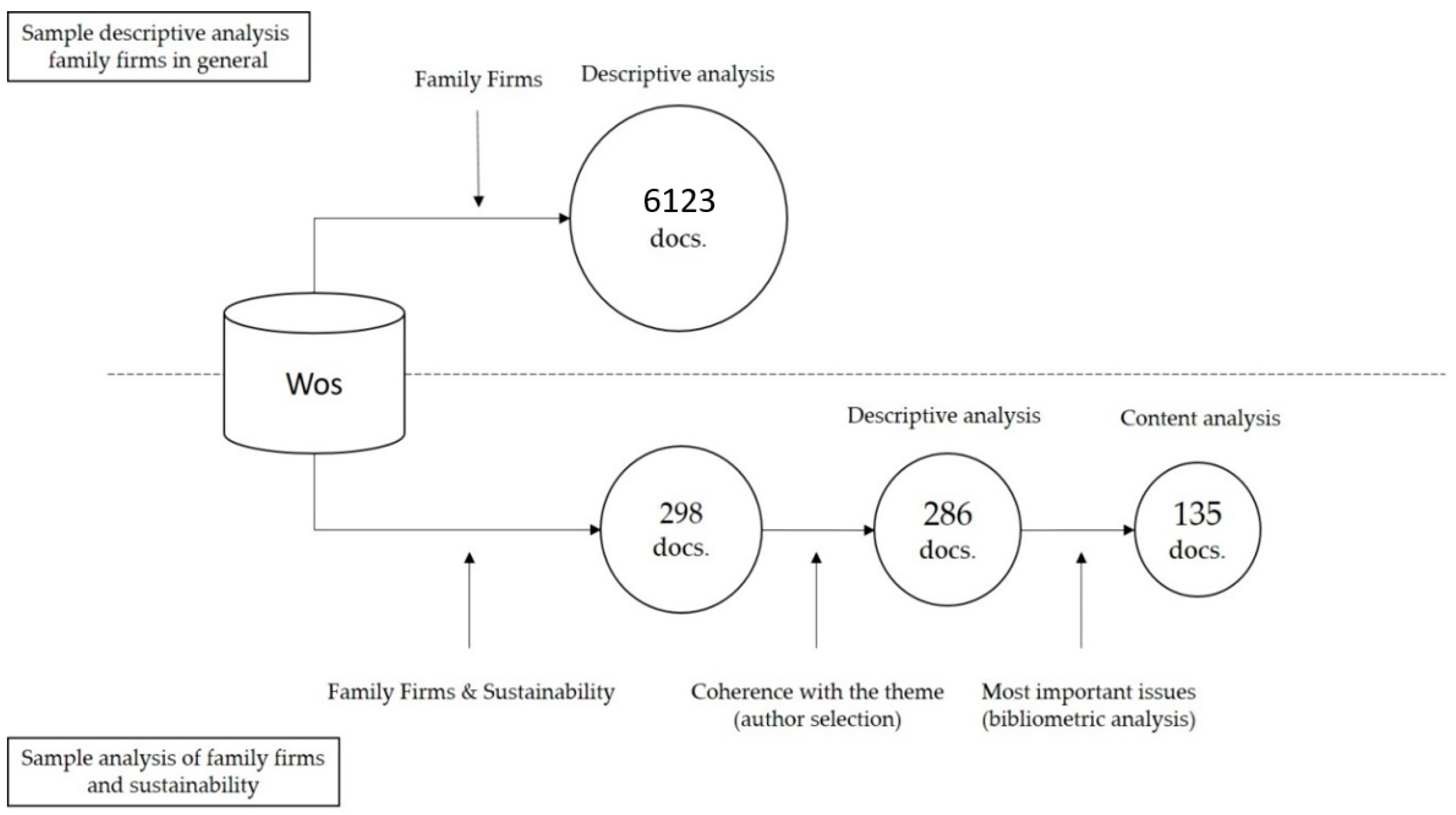

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Software

3. Results

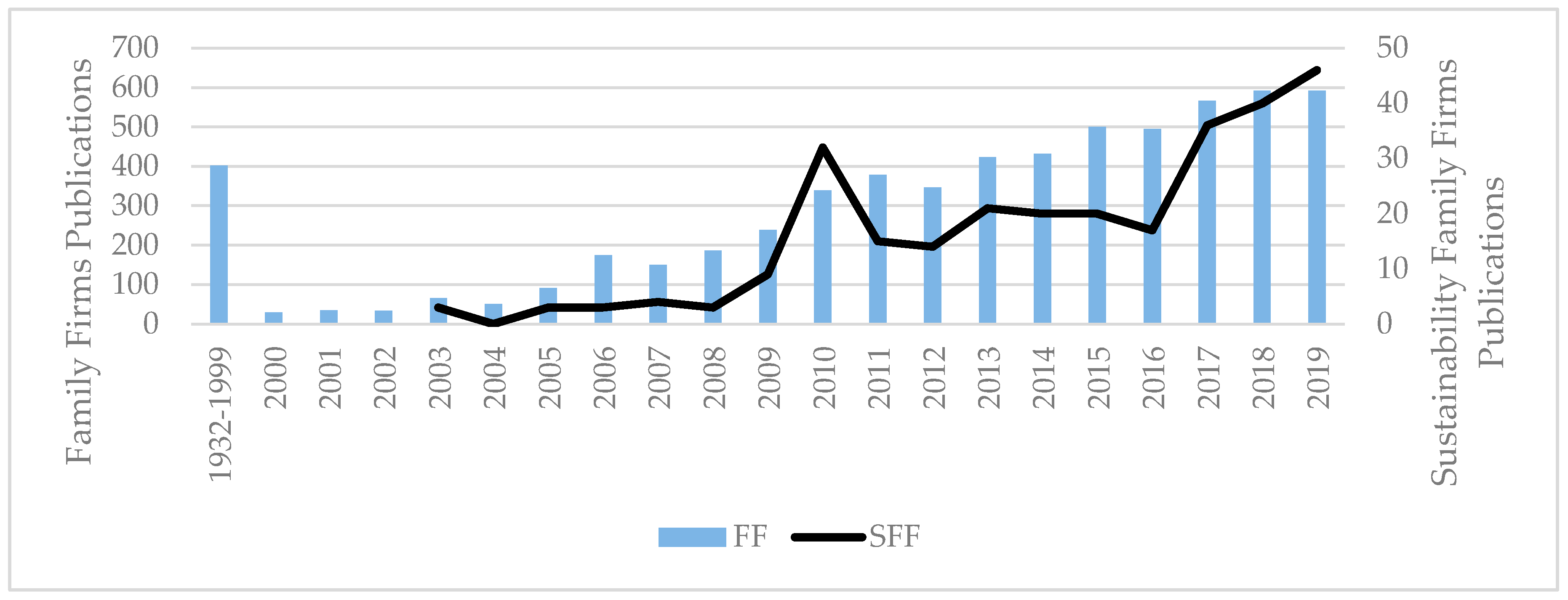

3.1. Indicators of Activity in the Literature on Family Firms and Their Sustainability

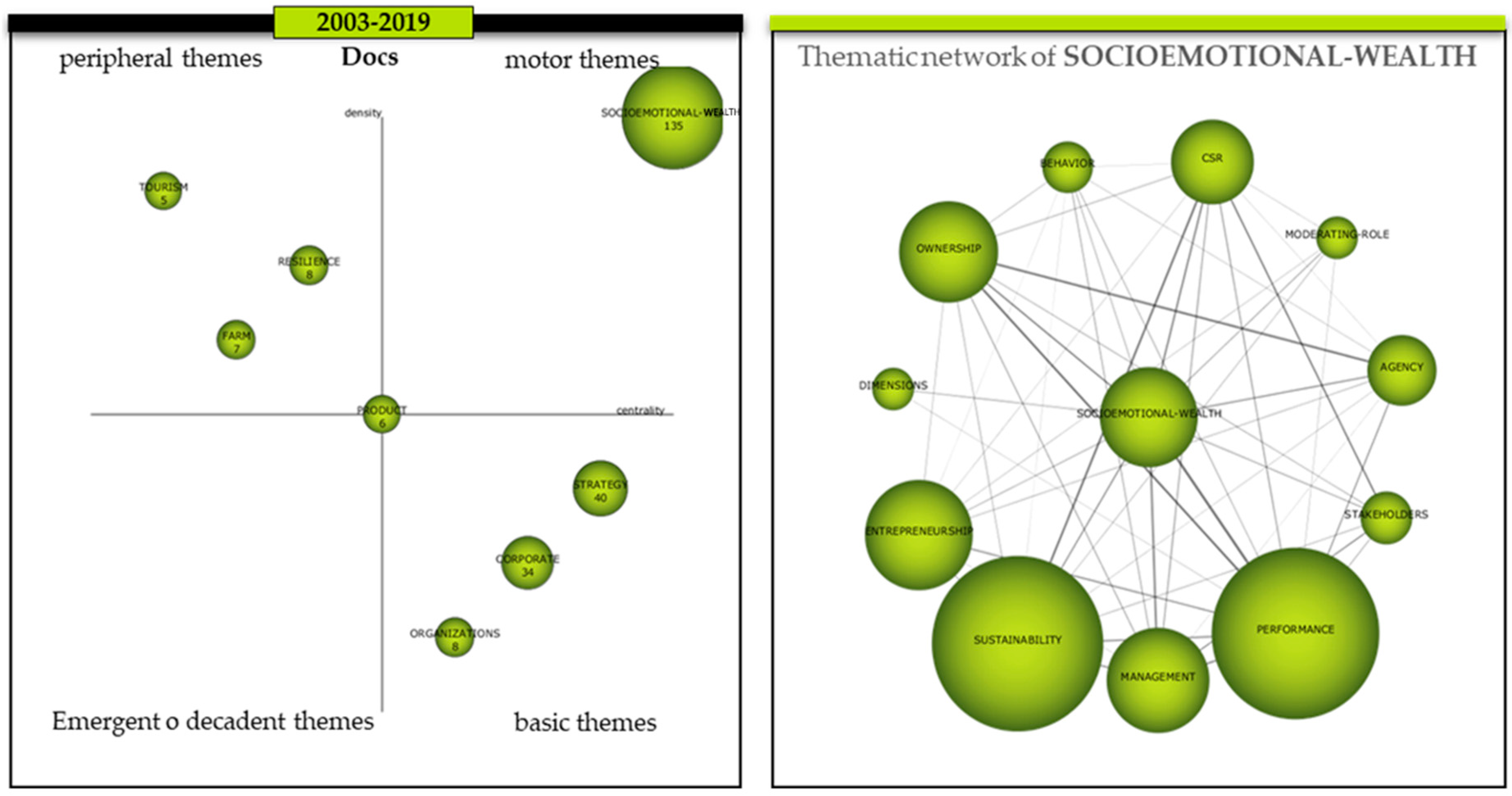

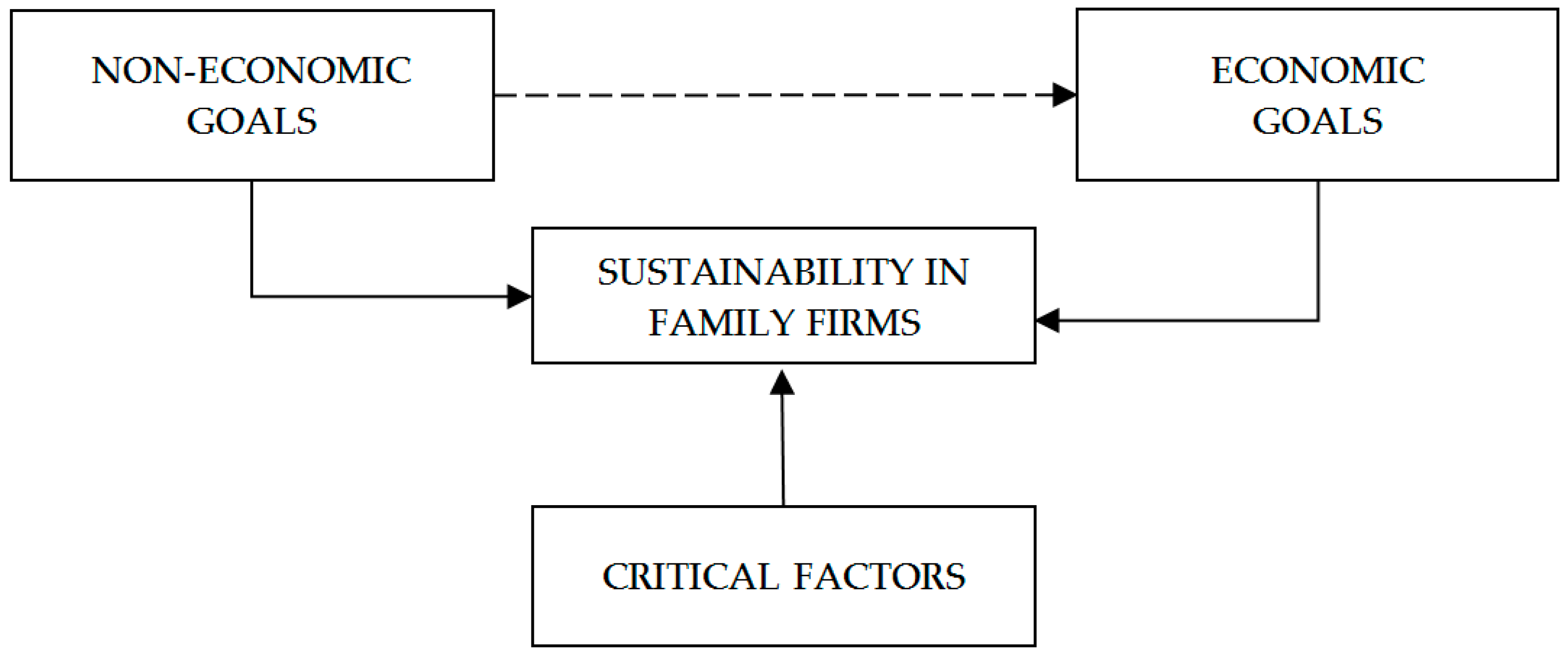

3.2. Analysis of Research on Sustainability in Family Firms

- Research that was interested in analyzing the company’s non-economic objectives.

- Those concerned with economic objectives or economic performance.

- Those that analyzed the critical factors that can affect the sustainability of the organization, from the point of view of survival.

3.2.1. Research Related to the Non-Economic Objectives of Family Firms

3.2.2. Research Related to the Economic Objectives of Family Firms

3.2.3. Critical Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Non-Economic Aspects of the Sustainability of Family Firms

4.2. Economic Aspects of the Sustainability of Family Firms

4.3. Critical Factors for Sustainability in Family Firms

4.4. Sustainability in Family Firms and Open Innovation

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Astrachan, J.; Shanker, M. Family Businesses’ Contribution to the U.S. Economy: A Closer Look. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2016, 16, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Family Enterprise Research Academy (IFERA). Family Businesses Dominate: International Family Enterprise Research Academy (IFERA). Fam. Bus. Rev. 2003, 16, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Kellermanns, F. Family firms: A research agenda and publication guide. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2011, 2, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Report on Family Businesses in Europe (2014/2210 (INI)). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2015-0223_ES.html#title1 (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Chua, J.; Chrisman, J.; Sharma, P. Defining the Family Business by Behavior. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 23, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbershon, T.; Pistrui, J. Enterprising Families Domain: Family-Influenced Ownership Groups in Pursuit of Transgenerational Wealth. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2016, 15, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T.; Nason, R.; Nordqvist, M.; Brush, C. Why Do Family Firms Strive for Nonfinancial Goals? An Organizational Identity Perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansberg, I.; Perrow, E.L.; Rogolsky, S. Family business as an emerging field. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1988, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, P.C.; de Mik, L.; Anderson, R.M.; Johnson, P.A. The Family in Business: Understanding and Dealing with the Challenges Entrepreneurial Families Face; Jossey-Bass: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- James, H. Owner as Manager, Extended Horizons and the Family Firm. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 1999, 6, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.; Brigham, K. Long-Term Orientation and Intertemporal Choice in Family Firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 1149–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memili, E.; Fang, H.; Koç, B.; Yildirim-Öktem, Ö.; Sonmez, S. Sustainability practices of family firms: The interplay between family ownership and long-term orientation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 26, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.; Zanini, R.; Korzenowski, A.; Schmidt Junior, R.; Xavier do Nascimento, K. Evaluation of Sustainability Practices in Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturing Enterprises in Southern Brazil. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Henriques, I. Stakeholder influences on sustainability practices in the Canadian forest products industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.; Larraza-Kintana, M. Socioemotional Wealth and Corporate Responses to Institutional Pressures: Do Family-Controlled Firms Pollute Less? Adm. Sci. Q. 2010, 55, 82–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debicki, B.; Matherne, C.; Kellermanns, F.; Chrisman, J. Family Business Research in the New Millennium: An Overview of the Who, the Where, the What, and the Why. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2009, 22, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Truant, E.; Zicari, A. Internal corporate sustainability drivers: What evidence from family firms? A literature review and research agenda. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De las Heras-Rosas, C.; Herrera, J. Family Firms and Sustainability. A Longitudinal Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Poutziouris, P. Leadership styles, management systems and growth: Empirical evidence from UK owner-managed SMEs. J. Enterp. Cult. 2010, 18, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, W.; Matthews, L.; Matthews, R.; Aaron, J.; Edmondson, D.; Ward, C. The price of success: Balancing the effects of entrepreneurial commitment, work-family conflict and emotional exhaustion on job satisfaction. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlaner, L.; Berent-Braun, M.; Jeurissen, R.; de Wit, G. Beyond Size: Predicting Engagement in Environmental Management Practices of Dutch SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 109, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doluca, H.; Wagner, M.; Block, J. Sustainability and Environmental Behaviour in Family Firms: A Longitudinal Analysis of Environment-Related Activities, Innovation and Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 27, 152–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkarskaya, H.; Marshall, M. Family Structure, Policy Shocks, and Family Business Adjustment Choices. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2010, 31, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanna, C.; Alfredo, D.; Lucio, C. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Survey among SMEs in Bergamo. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 62, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaia, L.; Vrontis, D.; Maizza, A.; Fait, M.; Scorrano, P.; Cavallo, F. Family businesses, corporate social responsibility, and websites. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1442–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Rung-Hoch, N. Sustainable entrepreneurial orientation in family firms. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, V.; Lulseged, A. Does family status impact US firms’ sustainability reporting? Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2013, 4, 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achleitner, A.; Günther, N.; Kaserer, C.; Siciliano, G. Real Earnings Management and Accrual-based Earnings Management in Family Firms. Eur. Account. Rev. Account. Rep. Fam. Firms 2014, 23, 431–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlar, J.; Fang, H.; de Massis, A.; Frattini, F. Profitability Goals, Control Goals, and the RandD Investment Decisions of Family and Nonfamily Firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 1128–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ding, H.; Kao, M. Salient stakeholder voices: Family business and green innovation adoption. J. Manag. Organ. 2009, 15, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Nikolakis, W.; Peters, M.; Zanon, J. Trade-offs between dimensions of sustainability: Exploratory evidence from family firms in rural tourism regions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1204–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavana, G.; Gottardo, P.; Moisello, A. The effect of equity and bond issues on sustainability disclosure. Family vs non-family Italian firms. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 13, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, E. Internationalisation and corporate governance in family businesses: A case study. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, C.; Emprechtinger, S. The role of stewardship in the internationalisation of family firms. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2016, 8, 400–421. Available online: https://www.inderscience.com/info/inarticle.php?artid=82220 (accessed on 2 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kuo, A.; Kao, M.; Chang, Y.; Chiu, C. The influence of international experience on entry mode choice: Difference between family and non-family firms. Eur. Manag. J. 2012, 30, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.; Williams, B. Let the Cork Fly: Creativity and Innovation in a Family Business. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2014, 15, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegtmeier, S.; Classen, C. How do family entrepreneurs recognize opportunities? Three propositions. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2017, 27, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, S. Drivers of Proactive Environmental Strategy in Family Firms. Bus. Ethics Q. 2015, 21, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adendorff, C.; Halkias, D. Leveraging Ethnic Entrepreneurship, Culture and Family Dynamics to Enhance Good Governance and Sustainability in the Immigrant Family Business. J. Dev. Entrep. 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Merwe, S.P. Determinants of family employee work performance and compensation in family businesses. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 40, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddleston, K.; Kellermanns, F.; Sarathy, R. Resource Configuration in Family Firms: Linking Resources, Strategic Planning and Technological Opportunities to Performance. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, T.; Jaskiewicz, P.; Hinings, C. How family, business, and community logics shape family firm behavior and “rules of the game” in an organizational field. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, A.; Torchia, M.; Jimenez, D.; Kraus, S. The role of human capital on family firm innovativeness: The strategic leadership role of family board members. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavana, G.; Gottardo, P.; Moisello, A. Sustainability Reporting in Family Firms: A Panel Data Analysis. Sustainability 2016, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzid, I.; Khachlouf, N.; Soparnot, R. How does family capital influence the resilience of family firms? J. Int. Entrep. 2019, 17, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, A.; Boncinelli, F.; Marone, E. Lifestyle entrepreneurs in winemaking: An exploratory qualitative analysis on the non-pecuniary benefits. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 31, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherchem, N. The relationship between organizational culture and entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: Does generational involvement matter? J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2017, 8, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters, M.; Bichler, B. Innovation research in tourism: Research streams and actions for the future. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 41, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, K.; Bhargava, V.; Danes, S.; Haynes, G.; Brewton, K. Factors Associated with Long-Term Survival of Family Businesses: Duration Analysis. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2010, 31, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella-Carrubi, M.; González-Cruz, T. Context as a Provider of Key Resources for Succession: A Case Study of Sustainable Family Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lušňáková, Z.; Juríčková, Z.; Šajbidorová, M.; Lenčéšová, S. Succession as a sustainability factor of family business in Slovakia. Equilibrium 2019, 14, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayah, S. Succession role of indigenous and non-indigenous family business in Indonesia to achieve business sustainability. In Proceedings of the 16th International Symposium on Management (INSYMA 2019), Manado, Indonesia, 4–6 March 2019; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Porfírio, J.; Carrilho, T.; Hassid, J.; Rodrigues, R. Family business succession in different national contexts: A Fuzzy-Set QCA approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Z.; Lo, F.-Y.; Weng, S.-M. Family businesses successors knowledge and willingness on sustainable innovation: The moderating role of leader’s approval. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Qinghua, Z.; Landström, H. Entrepreneurship research in three regions-the USA, Europe and China. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 861–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koiranen, M. Over 100 Years of Age but Still Entrepreneurially Active in Business: Exploring the Values and Family Characteristics of Old Finnish Family Firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 15, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, A.; Brodie, R. The influence of brand image and company reputation where manufacturers market to small firms: A customer value perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersick, K.E.; Davis, J.; Hampton, M.M.; Lansberg, I. Generation to Generation: Life Cycles of the Family Business; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston, K.; Kellermanns, F. Destructive and productive family relationships: A stewardship theory perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Chrisman, J. Risk abatement as a strategy for RandD investments in family firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowka, G.; Kallmünzer, A.; Zehrer, A. Enterprise risk management in small and medium family enterprises: The role of family involvement and CEO tenure. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.; Haynes, K.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional Wealth and Business Risks in Family-controlled Firms: Evidence from Spanish Olive Oil Mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Cruz, C.; Berrone, P.; de Castro, J. The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Acad. Manag. Annu. 2011, 5, 653–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanos-Contreras, O.; Jabri, M.; Sharma, P. Temporality and the role of shocks in explaining changes in socioemotional wealth and entrepreneurial orientation of small and medium family enterprises. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1269–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J.; Chua, J.; de Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Wright, M. The Ability and Willingness Paradox in Family Firm Innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, A.; Kotlar, J.; Chua, J.; Chrisman, J. Ability and Willingness as Sufficiency Conditions for Family-Oriented Particularistic Behavior: Implications for Theory and Empirical Studies. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2014, 52, 344–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlander, L.; O’Mahony, S.; Gann, D.M. One foot in, one foot out: How does individuals’ external search breadth affect innovation outcomes? Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 280–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizingh, E.K.R.E. Open innovation: State of the art and future perspectives. Technovation 2011, 31, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casprini, E.; de Massis, A.; di Minin, A.; Frattini, F.; Piccaluga, A. How family firms execute open innovation strategies: The Loccioni case. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 1459–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J.; Steier, L.P.; Rau, S.B. Sources of heterogeneity in family firms: An introduction. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koentjoro, S.; Gunawan, S. Managing, Knowledge, Dynamic Capabilities, Innovative Performance, and Creating Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Family Companies: A Case Study of a Family Company in Indonesia. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennamo, C.; Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez–Mejia, L. Socioemotional Wealth and Proactive Stakeholder Engagement: Why Family–Controlled Firms Care More about their Stakeholders. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1153–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; Larraza-Kintana, M.; Garcés-Galdeano, L.; Berrone, P. Are Family Firms Really More Socially Responsible? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 1295–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Ribeiro Soriano, D. A bibliometric analysis of international impact of business incubators. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1775–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xiao, L. Selecting publication keywords for domain analysis in bibliometrics: A comparison of three methods. J. Informetr. 2016, 10, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Martí, A.; Ribeiro Soriano, D.; Palacios Marqués, D. A bibliometric analysis of social entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1651–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. SciMAT: Software Tool for the Analysis of the Evolution of Scientific Knowledge. Proposal for an Evaluation Methodology. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, P.; Zuiker, V.; Danes, S.; Stafford, K.; Heck, R.; Duncan, K. The impact of the family and the business on family business sustainability. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 639–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjuha-Jivraj, S. The sustainability of social capital within ethnic networks. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 47, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, T.T. A novel living agricultural concept in urban communities: Family Business Garden. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2003, 10, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykal, E. Innovativeness in family firms: Effects of positive leadership styles. In Strategic Design and Innovative Thinking in Business Operations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 213–232. [Google Scholar]

- Dangelico, R.; Nastasi, A.; Pisa, S. A comparison of family and nonfamily small firms in their approach to green innovation: A study of Italian companies in the agri-food industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J. Family firm, health resort and industrial colony: The grand hotel and mineral springs at Mondariz Balneario, Spain, 1873–1932. Bus. Hist. 2014, 56, 1037–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannone, B. Sustainability to Improve Knowledge Values and Intangible Capital: A Case Study in Wine Sector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Knowledge Management, Udine, Italy, 3–4 September 2015; p. 367. [Google Scholar]

- Dayan, M.; Ng, P.; Ndubisi, N. Mindfulness, socioemotional wealth, and environmental strategy of family businesses. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Cacho, P.; Molina-Moreno, V.; Corpas-Iglesias, F.; Cortés-García, F. Family Businesses Transitioning to a Circular Economy Model: The Case of “Mercadona”. Sustainability 2018, 10, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, A.; Zhao, J. Staying alive: Entrepreneurship in family-owned media across generations. Balt. J. Manag. 2019, 14, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton-Miller, I.; Miller, D. Family firms and practices of sustainability: A contingency view. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2016, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, M.; Ciaburri, M. Why do they do that? Motives and dimensions of family firms’ CSR engagement. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mittal, S. Analysis of drivers of CSR practices’ implementation among family firms in India: A stakeholder’s perspective. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 27, 947–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campopiano, G.; Rinaldi, F.; Sciascia, S.; de Massis, A. Family and non-family women on the board of directors: Effects on corporate citizenship behavior in family-controlled fashion firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Mazagatos, V.; de Quevedo-Puente, E.; Delgado-García, J. Human resource practices and organizational human capital in the family firm: The effect of generational stage. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Freitas, W.; Jabbour, C.; Mangili, L.; Filho, W.; de Oliveira, J. Building Sustainable Values in Organizations with the Support of Human Resource Management: Evidence from One Firm Considered as the “Best Place to Work” in Brazil. J. Hum. Values 2012, 18, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, Y. Corporate Governance Structure, Financial Capability, and the R&D Intensity in Chinese Sports Sector: Evidence from Listed Sports Companies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosé, L.; Korunka, C.; Frank, H.; Danes, S. Decreasing the Effects of Relationship Conflict on Family Businesses: The Moderating Role of Family Climate. J. Fam. Issues 2017, 38, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odehnalová, P. The sustainability of family firms during an economic crisis. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference of Business Economics Management and Marketing 2018, Prušánky-Nechory, Czech Republic, 6–7 September 2018; Masaryk University: Brno, Czech Republic, 2018; pp. 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Brigham, K.; Payne, G. The Transitional Nature of the Multifamily Business. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.I.; Wong, K.L.; Choong, C.K. Can TQM improve the sustainability of family owned business? Int. J. Innov. Learn. 2015, 17, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, J.L.K.; Gomez, E.T. Advancing tacit knowledge: Malaysian family SMEs in manufacturing. Asian Econ. Pap. 2014, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullens, D. Entrepreneurial orientation and sustainability initiatives in family firms. J. Glob. Responsib. 2018, 9, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, K.; Takehara, H. Firm-level innovation by Japanese family firms: Empirical analysis using multidimensional innovation measures. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2019, 57, 101030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Chen, J.; Tripe, D.; Zhang, N. Family firms, sustainable innovation and financing cost: Evidence from Chinese hi-tech small and medium-sized enterprises. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardito, L.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A.; Pascucci, F.; Peruffo, E. Inter-firm RandD collaborations and green innovation value: The role of family firms’ involvement and the moderating effects of proximity dimensions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, Q. Evaluation on innovation efficiency of successor of Chinese listed family business based on DEA. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2019, 11, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Drivers of Sustainability Strategy in Family Firms. Proc. Int. Assoc. Bus. Soc. 2009, 20, 194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Luo, W.; Luo, B. Sibling Rivalry vs. Brothers in Arms: The Contingency Effects of Involvement of Multiple Offsprings on Risk Taking in Family Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, W. Chief emotional officer and succession of family enterprises: A review based on relational governance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Management Science & Engineering 17th Annual Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 24–26 November 2010; pp. 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.; Gergaud, O. Sustainable Certification for Future Generations: The Case of Family Business. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2014, 27, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudah, M.; Jabeen, F.; Dixon, C. Determinants Linked to Family Business Sustainability in the UAE: An AHP Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Améstica-Rivas, L.; King-Domínguez, A.; Larraín, C.; Parra, Y. Succession, performance and management capacity in family companies. Dimens. Empresarial 2019, 17, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiß, G.; Zehrer, A. Intergenerational communication in family firm succession. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2018, 6, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Won, D.; Park, K. Entrepreneurial cyclical dynamics of open innovation. J. Evol Econ. 2018, 28, 1151–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Liu, Z. Micro- and Macro-Dynamics of Open Innovation with a Quadruple-Helix Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, F.; Voordeckers, W.; Roijakkers, N.; Vanhaverbeke, W. Exploring open innovation in entrepreneurial private family firms in low- and medium-technology industries. Organ. Dyn. 2017, 46, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, N.; Carree, M.; van Gils, A.; Peters, B. Innovation in family and non-family SMEs: An exploratory analysis. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, A.; Kotlar, J. The case study method in family business research: Guidelines for qualitative scholarship. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Patel, P.C. Variations in R&D investments of family and nonfamily firms: Behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 976–997. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, A.W.; Carr, J.C.; Shaw, J.C. Toward a theory of familiness: A social capital perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 949–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, M. Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Park, K.; del Gaudio, G.; della Corte, V. Open innovation ecosystems of restaurants: Geographical economics of successful restaurants from three cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | FF | % | Acc. | SFF | % | Acc. | % SFF-FF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 592 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 46 | 16.1 | 16.1 | 7.8 |

| 2018 | 592 | 9.7 | 19.3 | 40 | 14.0 | 30.1 | 6.8 |

| 2017 | 566 | 9.2 | 28.6 | 36 | 12.6 | 42.7 | 6.4 |

| 2016 | 495 | 8.1 | 36.7 | 17 | 5.9 | 48.6 | 3.4 |

| 2015 | 500 | 8.2 | 44.8 | 20 | 7.0 | 55.6 | 4.0 |

| 2014 | 432 | 7.1 | 51.9 | 20 | 7.0 | 62.6 | 4.6 |

| 2013 | 423 | 6.9 | 58.8 | 21 | 7.3 | 69.9 | 5.0 |

| 2012 | 346 | 5.7 | 64.4 | 14 | 4.9 | 74.8 | 4.0 |

| 2011 | 379 | 6.2 | 70.6 | 15 | 5.2 | 80.1 | 4.0 |

| 2010 | 339 | 5.5 | 76.2 | 32 | 11.2 | 91.3 | 9.4 |

| 2009 | 239 | 3.9 | 80.1 | 9 | 3.1 | 94.4 | 3.8 |

| 2008 | 186 | 3.0 | 83.1 | 3 | 1.0 | 95.5 | 1.6 |

| 2007 | 150 | 2.5 | 85.6 | 4 | 1.4 | 96.9 | 2.7 |

| 2006 | 174 | 2.8 | 88.4 | 3 | 1.0 | 97.9 | 1.7 |

| 2005 | 92 | 1.5 | 89.9 | 3 | 1.0 | 99.0 | 3.3 |

| 2004 | 51 | 0.8 | 90.7 | - | 0.0 | 99.0 | 0.0 |

| 2003 | 66 | 1.1 | 91.8 | 3 | 1.0 | 100.0 | 4.5 |

| 2002 | 34 | 0.6 | 92.4 | - | - | - | - |

| 2001 | 35 | 0.6 | 92.9 | - | - | - | - |

| 2000 | 30 | 0.5 | 93.4 | - | - | - | - |

| 1932–1999 | 402 | 6.6 | 100.0 | - | - | - | - |

| 6123 | 286 |

| Journals | Docs. | % | Accumulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Business Review | 337 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Journal of Family Business Strategy (1) | 204 | 3.3 | 8.8 |

| Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice | 194 | 3.2 | 12.0 |

| Journal of Family Business Management (2) | 139 | 2.3 | 14.3 |

| Business History | 88 | 1.4 | 15.7 |

| Journal | Docs. | % | Accumulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | 20 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Business Strategy and the Environment | 8 | 2.8 | 9.8 |

| Journal of Family Business Management (2) | 7 | 2.4 | 12.2 |

| Journal of Family and Economic Issues | 6 | 2.1 | 14.3 |

| Journal of Family Business Strategy (1) | 5 | 1.7 | 16.0 |

| Authors (FF) | Docs. | Authors (SFF) | Docs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chrisman, JJ | 68 | Danes, SM | 17 |

| Kellermanns, FW | 68 | Haynes, G | 6 |

| From Massis, A | 55 | Stafford, K | 6 |

| Sharma, P | 51 | Fitzgerald, MA | 4 |

| Chua, JH | 46 | Amarapurkar, S | 3 |

| Miller, D | 46 | Lee, YG | 3 |

| Nordqvist, M | 39 | Heck, RKZ | 3 |

| Le Breton-Miller, I | 38 | Kellermanns, FW | 2 |

| Danes, SM | 34 | Zellweger, T | 2 |

| Voordeckers, W | 34 | Lee, J | 2 |

| Name | Centrality | Centrality Range | Density | Density Range | Docs. | Citations | H-Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socioemotional-wealth | 108.92 | 1.00 | 40.18 | 1.00 | 135 | 1882 | 22 |

| Strategy | 50.39 | 0.88 | 7.37 | 0.38 | 40 | 1089 | 15 |

| Corporate | 45.51 | 0.75 | 5.95 | 0.25 | 34 | 428 | 10 |

| Resilience | 5.57 | 0.38 | 18.07 | 0.75 | 8 | 84 | 5 |

| Organizations | 12.32 | 0.62 | 2.78 | 0.12 | 8 | 76 | 4 |

| Tourism | 1.35 | 0.12 | 18.17 | 0.88 | 5 | 8 | 2 |

| Farm | 1.83 | 0.25 | 14.26 | 0.62 | 7 | 65 | 3 |

| Product | 8.59 | 0.50 | 10.83 | 0.50 | 6 | 301 | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrera, J.; de las Heras-Rosas, C. Economic, Non-Economic and Critical Factors for the Sustainability of Family Firms. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040119

Herrera J, de las Heras-Rosas C. Economic, Non-Economic and Critical Factors for the Sustainability of Family Firms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2020; 6(4):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040119

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrera, Juan, and Carlos de las Heras-Rosas. 2020. "Economic, Non-Economic and Critical Factors for the Sustainability of Family Firms" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 6, no. 4: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040119

APA StyleHerrera, J., & de las Heras-Rosas, C. (2020). Economic, Non-Economic and Critical Factors for the Sustainability of Family Firms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040119