Responsible Research and Innovation in Enterprises: Benefits, Barriers and the Problem of Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

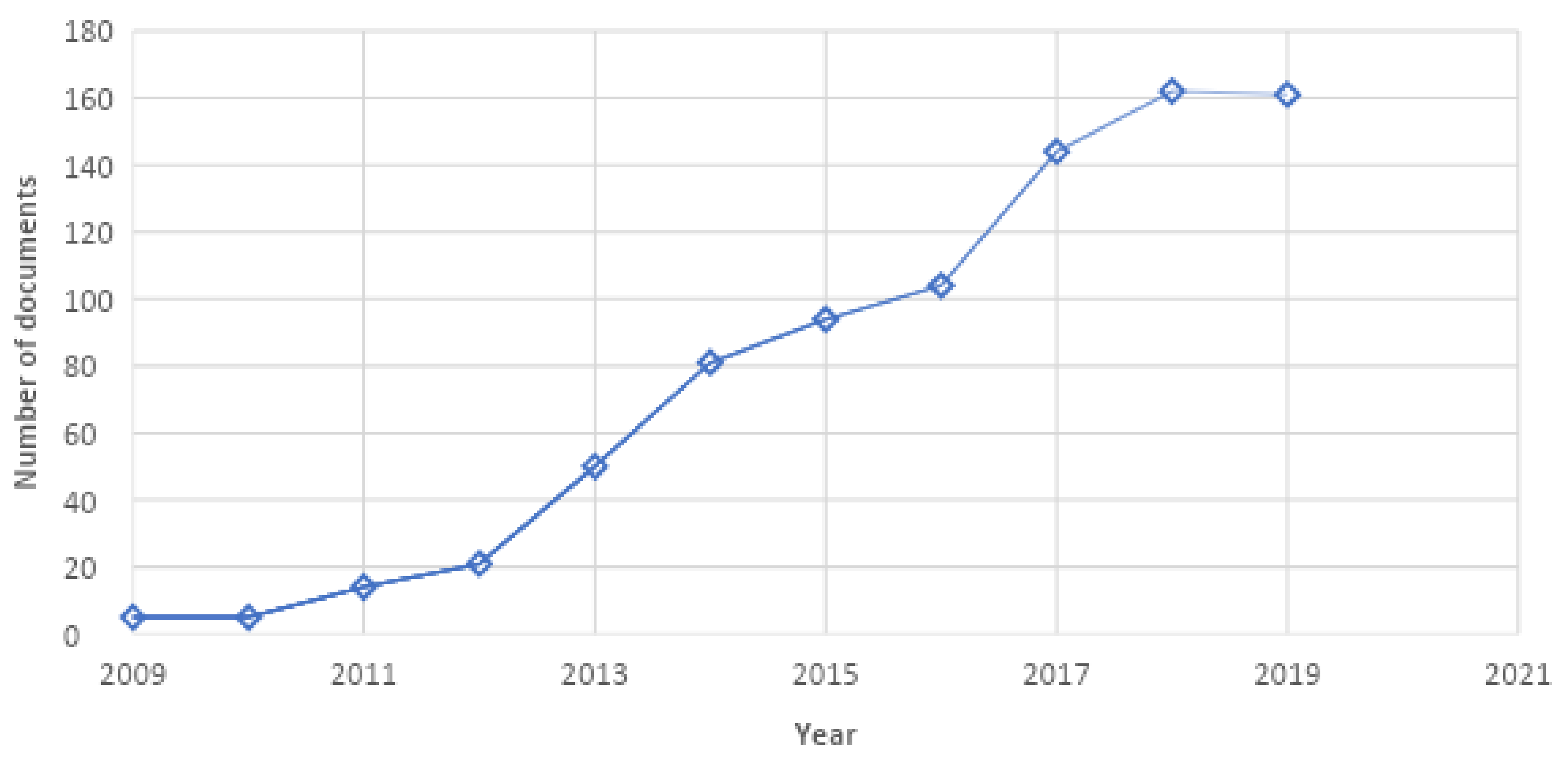

2. Responsible Research and Innovation—Overview of Current Discourse

3. Promised Benefits and Criticism of RRI

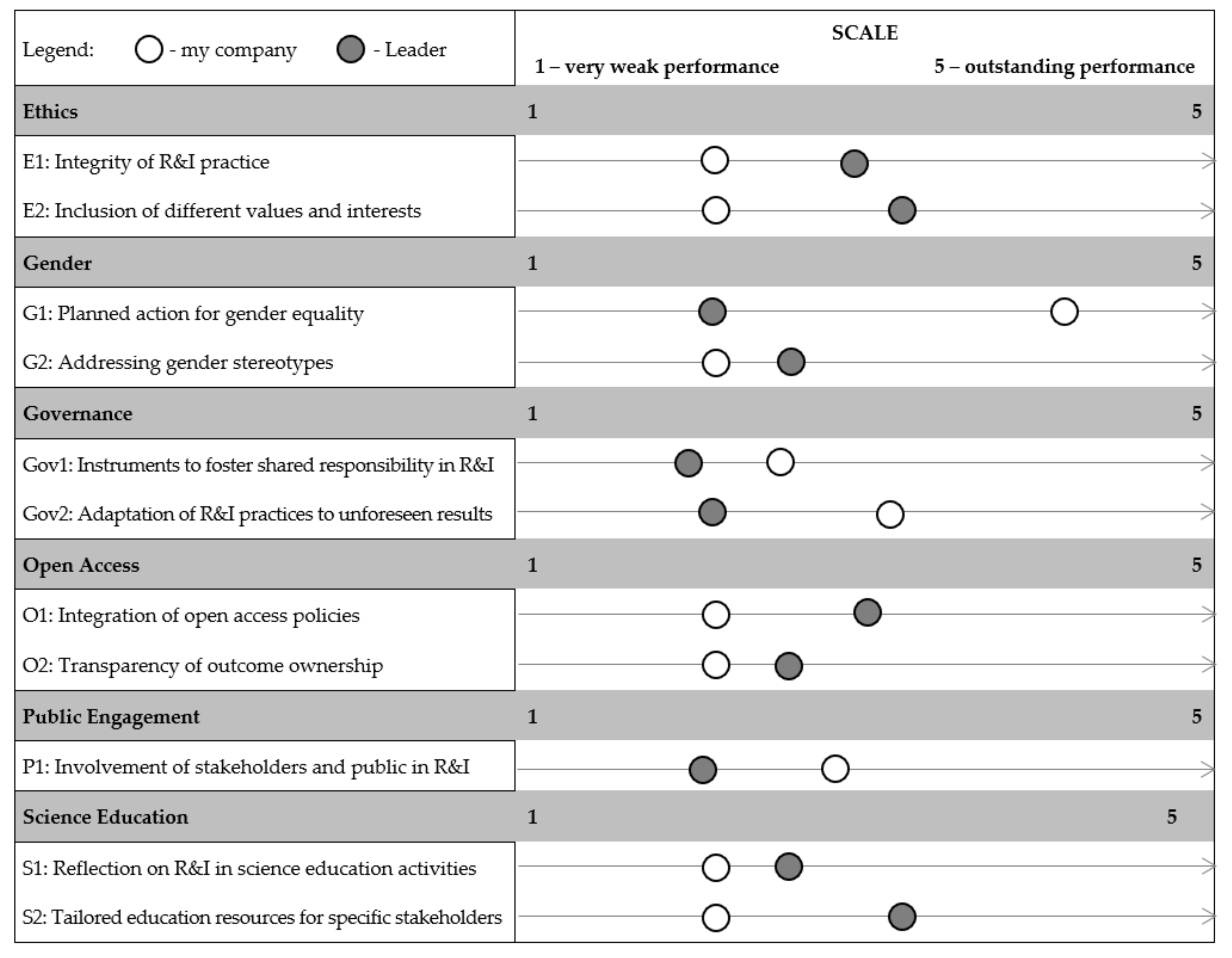

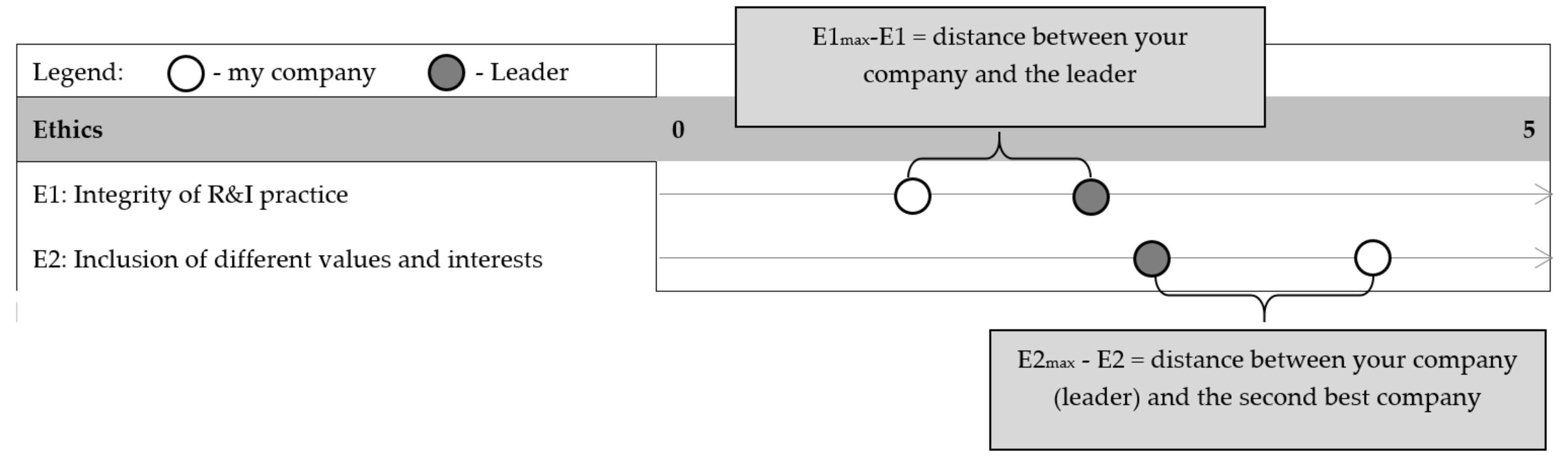

4. Towards an RRI index for Innovating Organizations

4.1. One RRI Index Does Not Fit All

4.2. Proposal of RRI Index for Innovating Organizations

- It is based on respondent’s subjective/arbitrary judgement (semi-quantitative nature);

- Its ingredients may be customized according the needs of a particular sector or a group of enterprises;

- Components of the index are weighted. Weights are also arbitrarily determined by the users of the index.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pathways Declaration. The Future of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) in “Horizon Europe”. Available online: http://pathways2019.eu/declaration/ (accessed on 22 December 2019).

- Von Schomberg, R. Prospects for Technology Assessment in A Framework of Responsible Research and Innovation. In Technikfolgen abschätzen lehren: Bildungspotenziale transdisziplinärer Methoden; Dusseldorp, M., Beecroft, R., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, F.; Dwyer, N.; Raicevich, S.; Grifoni, P.; Altiok, H.; Andersen, H.T.; Laouris, Y.; Silvestri, C. Preface. In Governance and Sustainability of Responsible Research and Innovation Processes. Cases and Experiences; Ferri, F., Dwyer, N., Raicevich, S., Grifoni, P., Altiok, H., Andersen, H.T., Laouris, Y., Silvestri, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. v–x. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Community Innovation Survey 2016; Eurostat: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D. Co-evolutionary scenarios: An application to prospecting futures of the responsible development of nanotechnology. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2009, 76, 1222–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, V.; Maier, F.; Spaini, C.; Woolley, R.; Meijer, I.; Costa, R.; Bloch, C.; Mejlgaard, N. Monitoring the Evolution and Benefits of Responsible Research and Innovation. The evolution of Responsible Research and Innovation—The Indicators Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cuppen, E.; van de Grift, E.; Pesch, U. Reviewing responsible research and innovation: lessons for a sustainable innovation research agenda? In Handbook of Sustainable Innovation; Boons, F., McMeekin, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 142–164. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans, J. Mapping the RRI Landscape: An Overview of Organisations, Projects, Persons, Areas and Topics. In Responsible Innovation 3. A European Agenda? Asveld, L., van Dam-Mieras, R., Swierstra, T., Lavrijssen, S., Linse, K., van den Hoven, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarko, L. Responsible research and innovation—A conceptual contribution to theory and practice of technology management. Bus. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.; Mejlgaard, N.; Alnor, E.; Griessler, E.; Meijer, I. Ensuring Societal Readiness: A thinking tool. Available online: https://www.thinkingtool.eu/Deliverable_6.1_Final_April%2030_THINKING_TOOL.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Horizon Europe. The next EU Research & Innovation Programme (2021–2027). Available online: https://prod5.assets-cdn.io/event/4336/assets/8428823124-12a7724d30.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2019).

- Owen, R.; Pansera, M. Responsible Innovation and Responsible Research and Innovation. In Handbook of Research on Public Policy; Simon, D., Kuhlmann, S., Stamm, J., Canzler, W., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 26–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J.; Park, K.; LM, C.; Shin, C.; Lee, S. Dynamics of Social Enterprises—Shift from Social Innovation to Open Innvation. In Proceedings of the SOItmC & CSCOM 2016 Conference, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA, USA, 31 May–3 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.; Egbetoku, A.; Zhao, X. How Does a Social Open Innovation Succeed? Learning from Burro Battery and Grassroots Innovation Festival of India. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2019, 24, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.; Park, J. How Social Entrepreneurs’ Value Orientation Affects the Performance of Social Enterprises in Korea: The Mediating Effect of Social Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walecka-Jankowska, K.; Zimmer, J. Open innovation in the context of organisational strategy. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2019, 11, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Liu, Z. Micro-and-Macro-Dynamics of Open Innovation with a Quadruple-Helix Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergvall-Kareborn, B.; Stahlbrost, A. Living Lab: An open and citizen-centric approach for innovation. Int. J. Innov. Reg. Dev. 2009, 1, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Stilgoe, J.; Macnaghten, P.; Gorman, M.; Fisher, E.; Guston, D. A framework for responsible innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Rmergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Bessant, J., Heintz, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2013; pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, E.; Guston, D. Making Responsible Innovators. In Does America Need More Innovators? Wisnioski, M., Hintz, E., Kleine, M., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 345–366. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarko, L. Responsible Research and Innovation in Industry: from Ethical Acceptability to Social Desirability. In Corporate Social Responsibility in the Manufacturing and Services Sectors; Golinska-Dawson, P., Spychała, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ceicyte, J.; Petraite, M. Networked Responsibility Approach for Responsible Innovation: Perspective of the Firm. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzawska, A.; Makinen, M.; Brey, P. Implementation of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) Practices in Industry: Providing the Right Incentives. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, J.; Yaghmaei, E.; Stahl, B.C.; Brem, A. Research and innovation processes revisited - networked responsibility in industry. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2017, 8, 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Foley, R.; Guston, D.; Bernstein, M. Broken promises and breaking ground for responsible innovation—Intervention research to transform business-as-usual in nanotechnology innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2016, 28, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, V.; Hoffmans, L.; Wubben, E.F.M. Stakeholder engagement for responsible innovation in the private sector: Critical issues and management practices. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2015, 15, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavie, X. Responsible Innovation: From Concept to Practice; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P.; Stilgoe, J. Responsible research and innovation: From science in society to science for society, with society. Sci. Public Policy 2012, 39, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B. Responsible research and innovation: The role of privacy in an emerging framework. Sci. Public Policy 2013, 40, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarko, L.; Melnikas, B. Responsible Research and Innovation in Engineering and Technology Management: Concept, Metrics and Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Technology & Engineering Management Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 12–14 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Inzelt, A.; Csonka, L. The Approach of the Business Sector to Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI). Foresight Sti Gov. 2017, 11, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.B.; Blok, V. Integrating the management of socio-ethical factors into industry innovation: Towards a concept of Open Innovation 2.0. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schomberg, R. Why Responsible Innovation. In International Handbook on Responsible Innovation: A Global Resource; Schomberg, R.V., Hankins, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 12–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji, A.K.; Levine, D.I.; Toffel, M.W. How Well Do Social Ratings Actually Measure Corporate Social Responsibility? J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2009, 18, 125–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, P.; Szutowski, D. Exploring the relationship between CSR and innovation. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn, T.; Nielsen, M.W.; Mejlgaard, N. Metrics and Indicators of Responsible Research and Innovation. Progress Report D3.2; MoRRI Project: Woluwe-Saint-Pierre, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, R.; Rafols, I. Progress Report D6: Definition of Metrics and Indicators for RRI Benefits; MoRRI Project: Woluwe-Saint-Pierre, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Singh, R. Responsible Innovation: A New Approach to Address the Theoretical Gaps for Innovating in Emerging E-Mobility Sector. In Governance and Sustainability of Responsible Research and Innovation Processes. Cases and Experiences; Ferri, F., Dwyer, N., Raicevich, S., Grifoni, P., Altiok, H., Andersen, H.T., Laouris, Y., Silvestri, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- RRI self-reflection tool. Available online: https://www.rri-tools.eu/self-reflection-tool (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Kupper, F.; Klaassen, P.; Rijnen, M.; Vermeulen, S.; Broerse, J. Report on the Quality Criteria of Good Practice Standards in RRI. Available online: https://www.rri-tools.eu/documents/10184/107098/D1.3_QualityCriteriaGoodPracticeStandards.pdf/ca4efe26-6fb2-4990-8dde-fe3b4aed1676 (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Čeičytė, J. Implementing Responsible Innovation at the Firm Level; Kaunas University of Technology: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Klippe, W. From MoRRI to SUPER_MoRRI: Monitoring as reflection and learning, not representation and control. Available online: https://blog.rri-tools.eu/-/from-morri-to-super_morri-monitoring-as-reflection-and-learning-not-representation-and-control (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Hedstrom, G.S. Sustainability: What It Is and How to Measure It; Walter de Gruyter Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarko, L.; Melnikas, B. Operationalising Responsible Research and Innovation—Tools for enterprises. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2019, 11, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, R. Responsibility and Freedom: The Ethical Realm of RRI; Wiley: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, M.; Chefneux, L.; Goldberg, A.; Von Heimburg, J.; Patrignani, N.; Schofield, M.; Shilling, C. Responsible Innovation: A Complementary View from Industry with Proposals for Bridging Different Perspectives. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejdys, J.; Matuszak-Flejszman, A.; Szymanski, M.; Ustinovichius, L.; Shevchenko, G.; Lulewicz-Sas, A. Crucial factors for improving the ISO 14001 environmental management system. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 17, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B.C.; Wright, D. Ethics and Privacy in AI and Big Data: Implementing Responsible Research and Innovation. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2018, 16, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarko, J.; Ejdys, J.; Halicka, K.; Magruk, A.; Nazarko, L.; Skorek, A. Application of Enhanced SWOT Analysis in the Future-oriented Public Management of Technology. Procedia Eng. 2017, 182, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicka, K. Main Concepts of Technology Analysis in the Light of the Literature on the Subject. Procedia Eng. 2017, 182, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkowski, C. Classification of forecasting methods in production engineering. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2019, 11, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarko, L. Future-Oriented Technology Assessment. Procedia Eng. 2017, 182, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.; Gianni, R.; Ikonen, V.; Haick, H. From technology assessment to responsible research and innovation (RRI). In Proceedings of the 2016 Future Technologies Conference (FTC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 6–7 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge, D. The Social Control of Technology; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Garst, J.; Blok, V.; Jansen, L.; Omta, O. Responsibility versus Profit: The Motives of Food Firms for Healthy Product Innovation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turovets, Y.; Vishnevskiy, K. Patterns of digitalisation in machinery-building industries: Evidence from Russia. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2019, 11, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ROSIE Project. Available online: https://www.interreg-central.eu/Content.Node/ROSIE.html (accessed on 22 December 2019).

- Halicka, K. Gerontechnology—The assessment of one selected technology improving the quality of life of older adults. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2019, 11, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund Declaration. Available online: https://era.gv.at/object/document/130 (accessed on 22 December 2019).

- Dijkstra, A.; Schuijff, M.; Yin, L.; Mkansi, S. RRI in China and South Africa: Cultural Adaptation Report: Deliverable 3.3; NUCLEUS project: Enschede, The Netherland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, D.; Kaplan, D. Responsible inclusive innovation: Tackling grand challenges globally. In International Handbook on Responsible Innovation: A Global Resource; Hankins, J., Schomberg, R.V., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 308–324. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarko, J.; Kuźmicz, K.A.; Szubzda-Prutis, E.; Urban, J. The general concept of benchmarking and its application in higher education in Europe. High. Educ. Eur. 2009, 34, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodakowska, E.; Nazarko, J. Environmental DEA method for assessing productivity of European countries. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2017, 23, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarko, J.; Chodakowska, E.; Kaplinski, O.; Paslawski, J.; Zavadskas, E.; Gajzler, M. Measuring productivity of construction industry in Europe with Data Envelopment Analysis. Innov. Solut. Constr. Eng. Manag. Flex. Approach 2015, 122, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, S.; Derler, H.; Rehorska, R.; Pabst, S.; Seebacher, U. Roadmapping to Enhance Local Food Supply: Case Study of a City-Region in Austria. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, G.; Yuan, B. Utilizing a Novel Approach at the Fuzzy Front-End of New Product Development: A Case Study in a Flexible Fabric Supercapacitor. Sustainability 2016, 8, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdtner, W.; Siebert, R.; Busse, M.; Freisinger, U. Regional Open Innovation Roadmapping: A New Framework for Innovation-Based Regional Development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2301–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

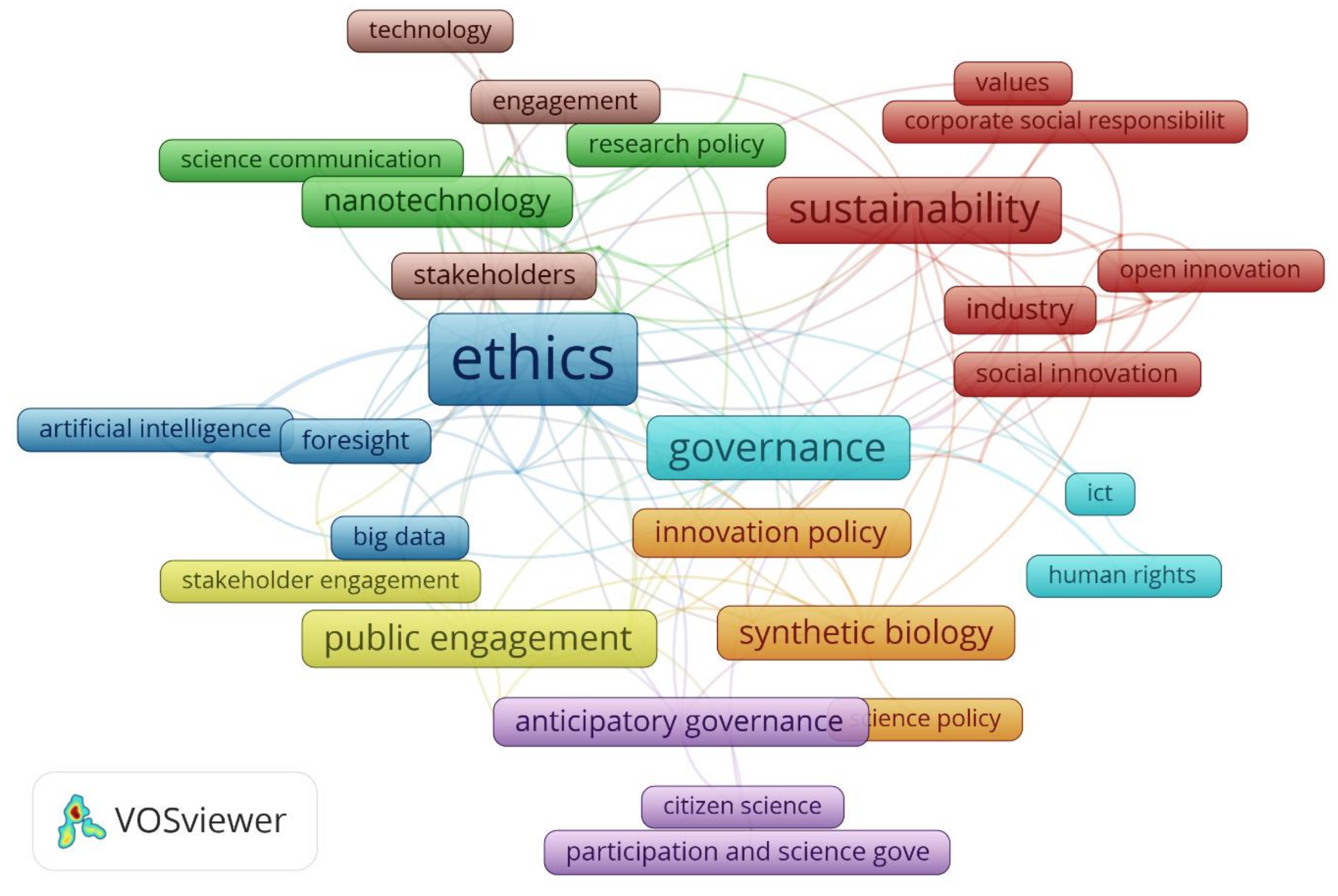

| Category | Keywords | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Epistemological foundations of RRI | values, Grand Challenges, ethics, human rights |

| 2 | Concepts and frameworks related to RRI | Corporate Social Responsibility, sustainability, sustainable development, social responsibility, value-sensitive design |

| 3 | Discussion on RRI principles | responsiveness, anticipation, participation, engagement |

| 4 | Analysis of RRI as a policy framework | research policy, anticipatory governance, participation and science governance, governance, innovation policy, science policy |

| 5 | Conceptualizing entrepreneurship and innovation in line with RRI principles | entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship, social innovation, open innovation |

| 6 | Sectoral approach to RRI | industry, emerging technologies, nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, big data, human brain project, ICT, synthetic biology, technology |

| 7 | Educational and participatory aspect of RRI | science communication, public engagement, science education, stakeholder engagement, citizen science, science and society, stakeholders |

| 8 | Tools and methods for RRI | foresight, technology assessment, risk assessment |

| 9 | Institutional origin and source of funding | Horizon 2020 |

| RRI Principle | Promised Benefits | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anticipation | Awareness of possible future legislation Increased foresight competences and better risk management “First mover” advantage |

| 2 | Reflexivity | Higher quality of innovation outcomes due to third-party critical appraisal Higher probability of innovation success |

| 3 | Transparency | Better ability to interpret available information thanks to the culture of sharing knowledge Higher effectiveness and efficiency of collaboration initiatives Better ability to match social expectations |

| 4 | Responsiveness | Increased trust from customers Improved corporate image and increased public trust in offered goods Better insight into needs and preferences of customers |

| Problematic Issue | Implications for Innovating Organizations | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | RRI concept under constant development; different views and understandings of RRI framework in the literature | Indifference towards the RRI idea Little comprehension of the notion of RRI |

| 2 | Western Eurocentrism of the RRI concept | Little chance of buy-in at the global level Regulatory and cultural differences between countries even within EU |

| 3 | No clear “division of labor” in the sphere of responsibility in the innovation activity as a consequence of the “shared responsibility” [29] or “meta-responsibility” [30] concepts | No clear indication of what is actually expected and at what stage from innovating businesses |

| 4 | Tension between “excellence” and “responsibility” both in science and business | Treating all activities related to RRI as an additional burden that makes innovation more costly and time consuming |

| 5 | Insistence on transparency and open access | Corporate strategies of intellectual property management not aligned with the open access paradigm |

| 6 | Shortage of understandable and easy-to-use tools to measure responsible innovation in business | Little interest in filling out long surveys and exhausting self-reflection forms |

| RRI Policy Agenda | Names of Indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender equality | share of organizations with gender equality plans, share of female researchers, share of female authors and inventors, gender wage gap |

| 2 | Science literacy and science education | importance of societal aspects of science in science curricula, availability of RRI-related training at higher education institutions, number of citizen science publications in Scopus, organizational membership in European Citizen Science Association |

| 3 | Public engagement | models of public involvement in science and technology (S&T) decision-making, Active information search about controversial technologies innovation democratization |

| 4 | Open Access | share of Open Access publications, citation scores for Open Access publications, incentives and barriers for data sharing |

| 5 | Ethics | presence and performance of research ethics structures at research performing and research funding organizations |

| 6 | Governance | use of science in policy making, RRI-related governance mechanisms within research-funding and performing organizations |

| RRI Policy Agenda | Names of Metric/Indicator | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender equality | Implementation of a gender equality plan and practices regarding team composition, management positions, work spaces, salary levels, contract conditions Systematic evaluation of the state of gender equality in the organization Provision of gender equality training Identification of gender stereotypes present in R&I activity |

| 2 | Science literacy and science education | Supporting citizens in making informed decisions Increasing stakeholder awareness that R&I can create solutions that have impact on their lives Using different outreach channels and adapting contents according to the target group |

| 3 | Public engagement | Engagement of relevant stakeholders in the innovation process (civil society organizations, local government, education community, customers, patients, families, etc.) Conducting outreach activities and reflecting on them Addressing conflicts of interests |

| 4 | Open Access | Ensuring transparency and open access throughout the innovation process Clear traceability of ownership and authorship |

| 5 | Ethics | Anticipation of the benefits and risks of innovation project (including long-term side effects) Ensuring project outcomes are used responsibly even after the project Alignment with the Code of Conduct for Research Integrity Encouragement of critical peer review and internal discussion on ethical issues throughout the process Consultation with external ethics experts or committees |

| 6 | Governance | Openness to emerging societal needs Readiness to change the research plan or innovation project in response to unforeseen results or as a result of a dialogues with the stakeholders Providing time for reflection during the innovation processes Appointment of a staff RRI expert Providing RRI training to employees |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazarko, L. Responsible Research and Innovation in Enterprises: Benefits, Barriers and the Problem of Assessment. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6010012

Nazarko L. Responsible Research and Innovation in Enterprises: Benefits, Barriers and the Problem of Assessment. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2020; 6(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazarko, Lukasz. 2020. "Responsible Research and Innovation in Enterprises: Benefits, Barriers and the Problem of Assessment" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 6, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6010012

APA StyleNazarko, L. (2020). Responsible Research and Innovation in Enterprises: Benefits, Barriers and the Problem of Assessment. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6010012