1. Introduction

In a complex and rapidly changing business world in which planning is falling to growing uncertainty, creativity has become a key resource [

1,

2]. “Wicked problems” as discussed by Rittel and Webber [

3] (p. 160) cannot be solved by rational, analytic approaches. When proven action patterns malfunction, approaches that help to develop novel, future-proof ideas are required.

As “art is a question and an attempt to answer it” (Alicja Kwade, visual artist) [

4] (para 16), artists are used to coping with uncertainty and well adapted to moving in complex environments. The artistic process is about exploring unknown paths, radically changing directions if necessary, making detours, abandoning failure and starting anew. Artists are working with methods that differ from rational, systematic management procedures by candour, mindfulness and intuition [

5,

6]. As artistic labour reaches far beyond analytical methods, artistic attitudes open different interpretations of reality (sensemaking) [

7,

8].

Discussing the relevance of the artistic process, Grant notes that artists are able to master ambiguous, uncertain situations with “unregulated inspiration, … and a lack of rules and limits” [

9] (p. 9). Inventive rule-breaking as an essential artistic guiding principle is supposed to start innovation in business contexts just the same. Artists are turned into role models: “Like artists, business people today need to be constantly creating new ideas. As we enter the 21st century, organizations’ scarcest resource has become their dreamers, not their testers”, Adler claims linking artistic qualities to leadership [

7] (p. 492).

Applying the arts to business environments is supposed to add value to corporate identity and branding, to leadership, human resources development and organizational change [

10,

11,

12]. Companies involve artists in strategic development [

13], entrust them with operational activities, such as in brand communication [

14] or simulate workflows common in performing arts [

15]. In project and product management, the self-organization within ensembles has inspired agile methodologies like scrum in software development.

Since the end of the ‘90s, arts-based or artistic interventions respectively have established themselves in organizational and personnel development. In their most widespread form, artists have company staff pass through a creative process based on the visual arts, the performing arts, music or poetry [

10,

16,

17]. The different approaches usually aim at improving problem-solving skills and the development of key competencies particularly with regard to social skills. The empirical research at this intersection between art and business focuses both on presumed individual effects (see, for example, [

18]) and organizational impact (see [

19] for an overview).

Arts-based interventions that are more ambitious and putatively sustainable range from coaching [

20] to residency [

21]. They are meant to initiate a system change within the organization. In fact, the support of corporate change and a positive impact on the capability for innovation belong to the most prominent empirically based effects of arts-based interventions [

12]. In this context, it is noteworthy that for the academic discourse on arts-based interventions as well as for the approach itself a western understanding of creativity is formative. Eastern cultural traditions prioritize collectivism and usefulness. According to western traditions, however, creativity tends to be associated with individuality and is commonly equated with novelty, originality and innovation. From the western point of view, creativity is closely linked to problem-solving [

22].

Manifestations of collaboration between artists and companies that target a mutual transfer of knowledge and innovative practices seem to be less prevalent than interventions for staff and organizational development. They are a blind spot of empirical research—despite their long historical tradition in engineering and technology. There are well-known examples for successful residency programs but none of them has turned into an object of research.

Technologists at Bell Labs have partnered with artists for more than 50 years. Within the scope of Experiments in Arts and Technology (E.A.T.), nine performances emerged involving big names like John Cage, Lucinda Childs and Robert Rauschenberg. The Arts/Industry residency program hosted by Kohler Co. has been fostering exchange since 1974 with the participating artists stretching technical boundaries engineers and craftspeople would not have turned to. During PAIR (PARC Artist-in-Residence), the artist in residence program Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) established in 1993, artists and scientists were working on similar ideas or shared materials and methods. In 2013 Microsoft started studio99, a project that has granted artists access to technologies and know-how ever since. The resulting artworks are presented in a gallery space maintained by the company’s research and development division.

Bosch recently had two artists arrange a whole floor as an unpredictable and challenging experimental space at its research campus. To the artists it is “no idea machine but a place that is putting out questions” [

23] (p. 578, translation from German by the author). In between misset clocks and other irritation objects on platform 12, employees commit themselves to Design Thinking. Visiting artists, who independently create their own works in reaction to these surroundings, are constantly challenging the Bosch researchers by their mere presence [

23,

24].

Whereas there is a growing pool of research on the mechanisms of action of arts-based interventions (see [

19]) and learning (see [

25]), aimed studies on artistic activities in research and development or business innovation are rare. That is particularly true with respect to the role artists play in collaborations that are meant to support product development or idea finding for organizational issues (see [

8,

26]).

The potential of collaborations lies in the disclosure of implicit knowledge. Artists do not have the same perception as managers and construct knowledge differently than engineers would. For the company hosting a residency, the artists’ intuition becomes a resource that opens up new vistas on working contexts and points out alternative courses of action [

8]. Artists encourage new ways of thinking, when they interfere as “artistic agents” [

23] (p. 558, translation from German by the author), who are constantly around, reflecting and commenting on the situation. On the other hand the encounter of artists and employees is causing friction [

23] and due to cultural differences, there may be communication problems the actors have to overcome [

26].

Other than such general observations and propositions there seems to be little evidence about artistic behaviour in situations that are meant to spark innovation. Artists are introduced as moderators or facilitators of arts-based interventions or creative labs and the course of their intervention is described (see [

13,

23,

26,

27]) but it remains unclear what is genuinely artistic in their approach and behaviour.

Against this background, the aim of this paper is twofold. Firstly, it will introduce Art Hacking, a creative method that is based on artistic strategies and work attitudes. Secondly, it will explore if and how artists demonstrate profession-specific attitudes in dealing with non-artistic assignments. The elements of Art Hacking provide the conceptual background for the examined case: an intervention with the participation of four artists aiming at idea generation for a business problem. The case is used to go into the following research questions on the roles of artists in business innovation.

How do artists operate in a collective idea generation process with heterogenous actors? How do they unfold their individual creative personality competence in an unfamiliar professional environment? How do they apply artistic strategies such as gathering, irritation, improvisation, alienation and derangement [

28] to a non-artistic subject? Which typical professional behaviour patterns are shown beyond individual idiosyncrasies?

The answers to these questions are supposed to provide clues for arts-based intervention frameworks with goals like innovation or organizational change. Does it make a difference if the artist is present?

2. The Conceptual Framework of Art Hacking

2.1. Core Idea and Theoretical Background

The intervention format Art Hacking, which was created by the author, aims at collective idea generation and the development of solutions for complex, possibly socially constructed business problems afflicted with uncertainty, which from a management point of view cannot simply be solved with common economic tools.

In a workshop for Art Hacking, groups of multidisciplinary stakeholders and artists from different genres work on a business problem that the participating organization brings in. The process is set off in a laboratory-like environment, which ideally includes inspiring architecture and allows for a change of location. In this respect, the design of Art Hacking is based on four insights from innovation research.

- (1)

Diversity in teams stimulates divergent thinking and fosters idea generation, because different perspectives collide [

29,

30]. From different angles, novel questions and new meanings emerge [

31]. Collective mindfulness allows for a perception of significant details, which have been overlooked before [

32].

- (2)

In every innovation process space is essential. Temporarily relocating staff from their usual workplace to physical environments that are designed for creative confrontation makes idea generation more effective [

33]. Innovation labs as well as other creative spaces need to be adaptable places for communication and collaboration with strong elements for the wellbeing of diverse users [

34].

- (3)

Materials have an intermediary function. Visualizing situations and organizational procedures can lead to a more profound understanding of the problem at hand [

8]. By sketches, prototypes, movement phrases and other means of expression, players not only can test novel solutions but also enter learning paths while exploring alternative opportunities step by step [

35]. Playing with material and its potential symbolic power as well as a non-verbal encounter with fellow players will open a different view on reality than a primarily rational, merely linguistic discourse [

36].

There are necessary conditions for emergent innovation, meaning radical change. These are certain attitudes, values and behaviours such as openness, perceptive faculty, reflectivity and the ability to recognize the “right moment” [

37]. The latter point is key for the method presented here, as it is artists who are gifted with all these traits [

38].

The core idea of the approach is to apply artistic attitudes and ways of dealing with an issue to problem-solving in a non-artistic environment. Insofar, the approach is both an instruction for idea generation and a training in artistic strategies. In this context, the immediate participation of artists in the process is supposed to facilitate access to artistic attitudes for other participants.

Apart from positive side benefits to human resource development, Art Hacking is a chance for organizations to incorporate the expertise of outside parties (artists, scientists, customers, etc.) in organizational change or product development. As regards the latter, a joint Art Hacking workshop can be part of an open innovation strategy serving an outside-in process. In general, the approach aims at business innovation in the sense of improving or even inventing processes, products, or services. By targeting idea generation however, it is limited to the very first stage of the innovation process.

2.2. Objective and Philosophy

The basic idea of the intervention is to convey artistic working styles to members of other professional groups and to apply characteristics of the artistic process to a business problem. The solution for the problem, the relevant ideas or a final concept respectively are quasi the work the players are creating together while they are exploring and solving the matter.

The method simulates the artistic process: picking up on an issue, doing preliminary research and conducting a dialogue with the material without preconceived views as to its outcome [

39]. Artists choose a motif or an issue they love to explore but they do not have a clearly defined objective in doing so [

28]. Artistic labour is about finding solutions in “non-linear explorative movements” [

28] (p. 127) and on creative roundabout routes. In the words of composer John Cage “the residual purpose of art is purposeless play” [

40] (p. 71).

An arts-based intervention is not purposeless in its nature even if its course and outcome are unpredictable. Adopting artistic strategies to idea generation and problem-solving has if any at all connections to applied art. However, the playful, sensuous approach is an essential feature, because “ideas are discovered by intuition” (Sol LeWitt, visual artist) [

41] (p. 79). Art Hacking initiates a process, in which artistic attitudes and strategies are used to solve creative challenges without going digital though.

Basically, the word “hacking” refers to a technique for doing or improving something. The term has its roots in journalism referring to unorthodox methods. It spread to computing and is currently transferred to areas such as cultural change and the arts [

42,

43]. In the artworld, hacks “have been used … as a strategy to generate discourse, collaboration and a starting point for new artworks and ideas” [

44] (p. 27). However, those hacks are usually about building digital prototypes from specific arts data sets [

44].

Basically, the word “hacking” refers to a technique for doing or improving something. The term has its roots in journalism referring to unorthodox methods. It spread to computing and is currently transferred to areas such as cultural change and the arts [

42,

43]. In the artworld, hacks “have been used … as a strategy to generate discourse, collaboration and a starting point for new artworks and ideas” [

44] (p. 27). However, those hacks are usually about building digital prototypes from specific arts data sets [

44].

Hacking is associated to creatively improvised solutions and a targeted undermining of patterns and attribution of meanings. It is about ignoring rules and rewriting them in favour of innovation. Therefore, a typical hack will combine the serious game with playful seriousness and an experimental, tinkering approach. A hacker is a person who explores a foreign system and finds his way in it thus being able to implement a disorientation and initiate new structures without predetermining their precise features [

42]—a working principle that strongly resembles the systemic nature of arts-based interventions in business.

In idea generation, letting go of rules and routines and making up new ones is of similar importance as in a genuine artistic process. Therefore, there are elements in Art Hacking that encourage participants to leave their thinking patterns aside, bend reality and sound out alternative solutions they would not have dared to even think about in the beginning. The format shall set up a space for purposeful play and divergent thinking [

45].

In this space, experimenting is meant to be safe, although expectations of clients towards the players may be high. Aiming at a certain outcome would not correspond to artistic attitudes. Even if they have to subject themselves to time schedules of rehearsals and are working towards the premiere, performance artists do not expect something predefined to happen in a given timeframe or predictable order [

39]. They “trust the process” [

46]. As with artistic labour itself the artistic intervention entails the risk of failure. Clients need a minimum of courage to take the plunge into the experimental arrangement.

In order to minimize this risk, the different stages in the process are scripted. Art Hacking has a certain sequence of elements that may be varied, switched and even skipped sometimes if the situation or the progress of the working groups require adjustments. The elements are chosen and arranged in a way that seems most suitable for the issue. For instance, if the workshop is essentially about leadership other film footage and image material will be used than if the matter was customer communications. However, the participants do not receive any schedule or detailed information on the process sequence before and during the workshop in order to have them experience the uncertainty of being in an open-ended and unpredictable creative process full of surprises.

At every stage of the process, the participants are confronted with tasks that are supposed to convey artistic attitudes and/or meant to foster an in-depth reflection and debate about the issue. In order to establish the next step in the process, each assignment is introduced by a story about the genesis of an artwork or by statements from artists who comment on a certain phase in their labour. These examples are implemented in the plenum as well as flanking rituals (varying welcoming and farewell routines) and energizers (active breaks). The assignments are elaborated in the working groups or in even more fragmented constellations through to pair work. Within this frame, specific activities of participants and the interaction within the working groups are free to unfold.

The tasks the players have to complete explicitly refer to artistic strategies such as deconstruction, reversal, improvisation, cut-up and chance operations. The players are using dictated artistic media that may support or undermine their almost unavoidable verbal discourse. The permanent change of work techniques and varying content-related approaches results in a change of perspective. Both the issue and possible solutions are patiently and persistently turned back and forth.

The joint quest is not finished when the first viable idea appears. Ideally, it is pursued for several days. Participants usually reach solutions that are more inventive this way. Experience shows that the starting problem always recedes into the background during the process and gives way to a fundamental question, the players were not able to see in the beginning. This question will lead them “out of the box” and to more original and sometimes even disruptive solutions.

Although Art Hacking does not claim to be a variety or a distant relative of applied arts, it latches on to the view that other than design art is not about solving problems but “finding solutions for questions yet unknown” (Daniel Richter, painter) [

47] (para 27, translation from German by the author).

2.3. Process Sequence

Artistic labour never begins with a cold start. An ensemble will start their rehearsal process by warming up so as to focus and tune into each other [

48]. Visual artists have similar rituals for getting connected with the task they address themselves to. The next step of the process is an in-depth analysis of the chosen issue or the material, respectively. It is a playful, explorative and non-linear questioning [

28,

39]. Based on these insights, the artwork is formed organically in a constant interplay of tentative action, perception and reflection—a process in which the space of possibilities gradually narrows. The artwork is finished when a harmonious expression is achieved [

39]. In performance arts, this is not necessarily the date of the premiere: often artists will continue filing after the first performance. Visual artists usually let their work rest and finally abandon it while presenting it to the public.

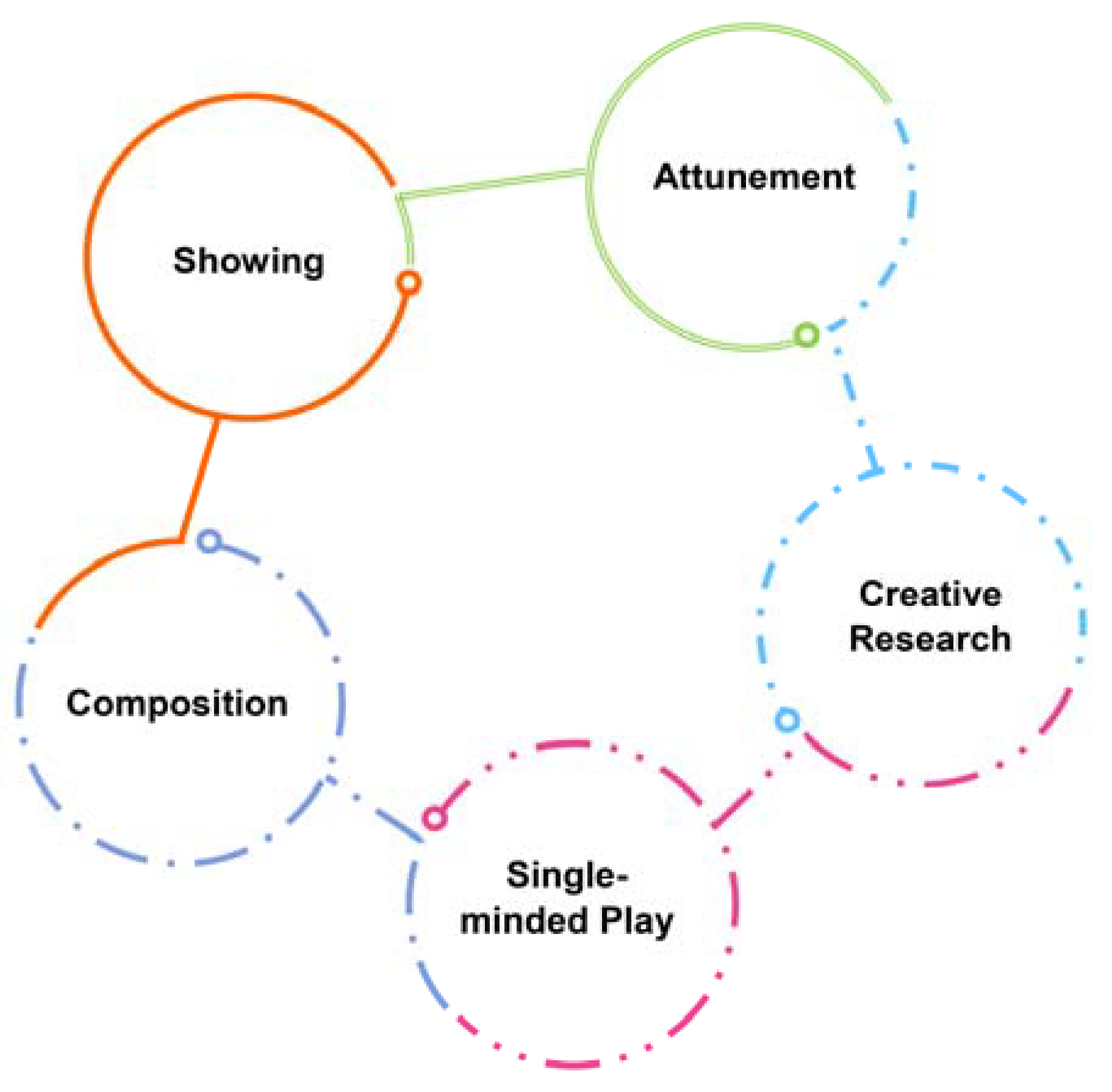

Art Hacking picks up on these stages but leaves them as overlapping, as they are in a genuine artistic process. The format has five phases during which solution approaches for the given issue are developed: attunement, creative research, single-minded play, composition, and showing (see

Figure 1). These phases are not strictly separated. Some explorative tasks are only introduced at the third stage and there are tricks to keep both the penultimate stage playful and to overcome blocks.

The five phases are described below. Each passage is illustrated by an artists’ quotation that reflects a typical attitude to the respective part of the artistic process to be emulated. Empirical studies show that other artists usually share these attitudes regardless of their genre or reputation [

38,

39].

Phase 1. Attunement

The great thing about the band was that whoever had the best idea (it didn’t matter who) that was the one we’d use.

(Ringo Starr, musician, on The Beatles) [

49] (p. 241).

The radar is on whether you know it or not.

(Keith Richards, musician) [

50] (p. 183).

At the beginning of the joint work, the participants are transformed into an ensemble-like entity. Meeting each other without prejudice is more important, the more heterogenous the group is. The first objective at this stage is to have the participants develop mutual trust and esteem for the different qualities they are bringing in. Targeted team building activities shall equalize any difference in status and sensitize the players in taking turns as leader and followers. The participants are invited to reflect on the actual and the desirable distribution of roles within their working group.

The second objective of “attunement” is to focus, sharpen the senses and invite intuition. Suitable training tasks, which address different levels of perception, support attentiveness. Moreover, there are exercises in depicting, listening and understanding for improving the dialog capability and avoiding killer phrases.

A simple creative exercise with a minimum of rules allows the players to experience an inventive process that has no preconceived result. Each player is asked to transform a cheap everyday object whose form and material composition will prevent a functional, assessable solution. This exercise is a foretaste of the open process that is to follow.

Phase 2. Creative Research

You‘re doing research. You‘re exploring, in the really deepest sense. When I start to work on a piece, I talk to people, I read.

(Meg Stuart, choreographer) [

51] (para 11).

Anywhere I ask the dancers questions … and everybody thinks about them. … Initially, all this together is only a material, a collection of material, yet it is not a piece at all.

(Pina Bausch, choreographer) [

52] (p. 92, translation from German by the author).

The real process of idea generation starts with creative research on the issue. Participating representatives of the organization introduce the problem in small groups. This very first input is not given by a classical presentation but in the form of a controlled dialogue in order to deepen mutual understanding and to avoid premature interpretations.

Afterwards, the players actively explore the issue. The most important tool for drilling out the problem is to ask consecutive questions without answering them and to follow just the crucial questions later on. The players gather information on the problem, including approaches that have not worked in the past.

Similar to a process of artistic inquiry, the players are requested to visualize the problem. They may work on a common collage, a sculpture or some other form of visual expression. In search of a suitable shape they are getting to the bottom of the problem. The object will probably uncover aspects that were underrated or out of sight beforehand, as well as bringing irrational influences to light.

The creative research results in a common understanding of the problem within each working group. As this phase partly overlaps with the next one—single-minded play— the players are usually working on the obvious symptoms first, before they get to the real cause of the problem. Since this insight is more a flow than a moment, it is unpredictable. It is rooted to the act of decentration: while turning the gaze away from the starting position its meaning will change.

Phase 3. Single-minded Play

Mostly I will do the work that I am afraid of. If I am really afraid of an idea this is exactly the point I have to go.

(Marina Abramović, performance artist) [

53] (4 min, 14 s).

You always reach for the easy solution before you, in defeat, submit to the more difficult solution.

(Jonathan Franzen, novelist) [

54] (p. 45).

The first assignment for the participants in the so-called single-minded play phase is gathering ideas between two workshop units without evaluating them. This is brainstorming outside the group, so to say. Back at the workshop, the challenge is not to take up the first agreeable idea that comes along. Therefore, the discussion begins with the rejected ideas the players did not even note because they seemed weird or unfeasible and then expanded with the presumably good ideas. With the help of deepening questions and a successive comparison of alternatives, the idea pool is downsized.

The players continue with selected ideas and are working on the approaches in a mode of purposeful play. The objective of this stage is to be prolific and to produce material. The participants shall find different solution variants to play with. In doing so, improvisation principles are helpful. Other than a destructive “Yes, but…” an open attitude will expand the potential space of possibilities. “Yes, and…” means accepting whatever another player states and to expand on that line of thinking by adding new information or insights.

Improvisation is only one of several artistic strategies the players are taught to apply during the process. They are encouraged to abandon premises, question everything, break patterns and disobey rules. By changing restrictive framework conditions and parameters of the situation, in their minds they will imagine solutions that are feasible.

Each element at this stage is an arts-based impulse fostering fluency. The players are urged to alter the familiar and change definitions. They use metaphors and indulge in absurd analogies, such as envisioning the organization and its environment as a zoo. In addition, there are random irritations that distract them from linear, convergent thinking. An example for combining incompatible things is to integrate a term like ‘sauce thickener’ in an emerging concept.

Phase 4. Composition

Ideas flow out of work. You open a door, you are looking around. And if you do not like it, you shut the door and open the next one.

(Chuck Close, painter) [

55] (p. 54, translation from German by the author).

Sometimes adding words or verbalizing an idea is actually counterproductive … So sometimes I just make a model.

(Olafur Eliasson, visual artist) [

56] (2 min, 11 s).

In the next-to-last stage, particular ideas are elaborated and merged into a concept. The players file the elements of a looming solution. The fourth stage marks a state of continuous reflection and doubt as well as a procedure of gradual refinement. The approaches are meant to be condensed and reduced to the point while the concept is visualized as a collage, sculpture, installation, storyboard or mini drama. The artistic maxim at this point is: “Kill your darlings!” Despite positive experiences with the format, it cannot be ruled out that the process ends in an act of complete destruction and will start over at an earlier stage or begin completely anew.

Phase 5. Showing

Each exhibition is … an inspection. Will my work last?

(Thomas Schütte, visual artist) [

57] (para 35, translation from German by the author).

I change things in each performance series. I skip breaks, I shift sequences.

(Sasha Waltz, choreographer) [

58] (para 11, translation from German by the author).

Depending on the timeframe of the workshop, the stages of composition and showing are more or less intertwined and extended. Showing may refer to the presentation of a draft to other participants or uninvolved external persons who are confronted with the embodiment of the idea and engaged in conversation. Based on the criticism of the draft and a possible exchange of ideas, a refined solution and another object are developed, respectively.

Other times showing may mean just a single presentation. With a tight schedule, the reality check is skipped in favour of a display among the participants, followed only by a debate of the different ideas in the plenary.

3. Methodology

As the theoretical and empirical state of knowledge about artistic behaviour in non-artistic settings was low, the present study pursued a descriptive-explorative objective. The qualitative research approach allowed hypotheses on the role of artists in arts-based interventions to be developed [

59].

The study is based on a case the above-described approach of Art Hacking was rolled out into. In other words, a given concept was applied to the case according to the above-mentioned sequences. The starting point for the arts-based idea-finding process was an unsolved problem that a big provider of child day-care establishments introduced: How can you encourage parents to engage in voluntary activities in the establishments and have them participate in joint efforts for child education in big cities? As four artists were working simultaneously on the issue, the case promised rich and concise information (homogenous sampling) [

60].

24 people joined the five-day workshop, which took place in Berlin, Germany. In each of the six-person groups that were working on the issue in parallel, one or two staff members from the central administration, two (leading) educators from day-care centres, one or two parents, one business student and one artist were always, continuously participating.

Artist 1 is a painter. Visual artist 2 has a focus on sculpture and installation art. Artist 3 is trained as an actress, mime and dancer. Artist 4 is working in improvisation theatre. All of them have worked in their artistic profession for more than ten years and possess appropriate experience and expertise. Only artist 4 is a parent who has experience with a day-care centre.

Before the workshop started, the artists had been asked to participate actively but they had not received beforehand any information about the five stages of Art Hacking, process details or specific tasks. They knew the arts-based philosophy of the approach and the issue in broad outline but not any work step or assignment given to the participants. Their role in the format was vaguely described to them as facilitators and reduced to a “Just be yourself!”

The research team consisted of the author who moderated the workshop, an assistant that supported the event and deliberately observed the happenings and the above-mentioned students. These were actively working on the issue and their assignment as observers. In order to enhance the necessary objectivity during the participatory observation, the author stayed out of the collection of data and the assistant was not involved in the work process of the participants other than setting its frame. With the exception of two students, all members of the research team had some experience with the format and other participating artists, which favoured the awareness of interesting behavioural aspects.

For structuring the observation and analysing the collected data, the critical incident technique after Flanagan [

61] was used. Originally, the critical incident technique was designed for creating job profiles but it can be applied flexibly to other social-science aspects as well. The essential methodical element is a semi-structured questioning technique: Test persons report on situations in which individual behaviour had any positive or negative effects on the main goal of the activity in question. Thereby, key behaviours are identified and categorized [

61].

Accordingly, both human behaviour and its significance for other actors involved were considered during the arts-based event. The objective of the analysis were the approaches the artists applied during the event and the role they played in their working groups. The artists’ expert status is proved by their professional self-conception and experience.

With regard to the requirements for defining critical incidents (see [

62]) 17 longer sequences in the workshop format were determined as relevant situations. Each of the chosen sequences was related to an explorative and/or creative assignment for either the small groups or the plenum, which was supposed to promote solutions to the issue. It was assumed that artistic behaviour patterns of interest would show at these points in particular.

The rule of not letting the participants know anything about the process sequence (see Chapter 2.2) had to be eased in favour of participant observation. With the critical incidents both the assistant and the student observers had a rough outline of the workshop at hand. Thus, they knew about the consecutive stages of Art Hacking but were asked not to share this information with other participants. The students received a short questionnaire for capturing artistic approaches and positions:

When do the artists interfere in the process?

What do they do?

How do they proceed?

What consequences does their behaviour have for the working process?

What role do they play and what effect does that have on the small group?

The participating observers were asked to outline the situation as well as to give a detailed description of behaviour and its effects on process and fellow players for every critical incident. Immediately after the workshop, an in-depth group discussion with the observers took place, methodically derived from a behavioural event interview [

63].

The minutes of all five observers and the content of the group discussion were supplemented by anonymous, short written statements of non-artistic participants. Near the end of the workshop, these were requested to name situations and related activities of the artists that were striking from their point of view, as they differed from attitudes of other participants and/or promoted the process in a special way.

The written material underwent a thematic content analysis in order to categorize the observations made at the critical incidents. Categories are “groups of work behaviours that share some common theme” [

62] (p. 1128). In order to objectify the findings, the observations were broken down independently by two persons at first, namely the author and her assistant. Starting from that, a pattern of main and subcategories [

61] emerged.

4. Findings

4.1. Overview

Although the artists who participated in the workshop come from diverse art forms and seemed to be different in their personality in terms of extraversion, there were strong parallels in their individual behaviour. The aspects that appeared with all of them and repeated independently from the individuals at various points in the process can be mapped in two dimensions.

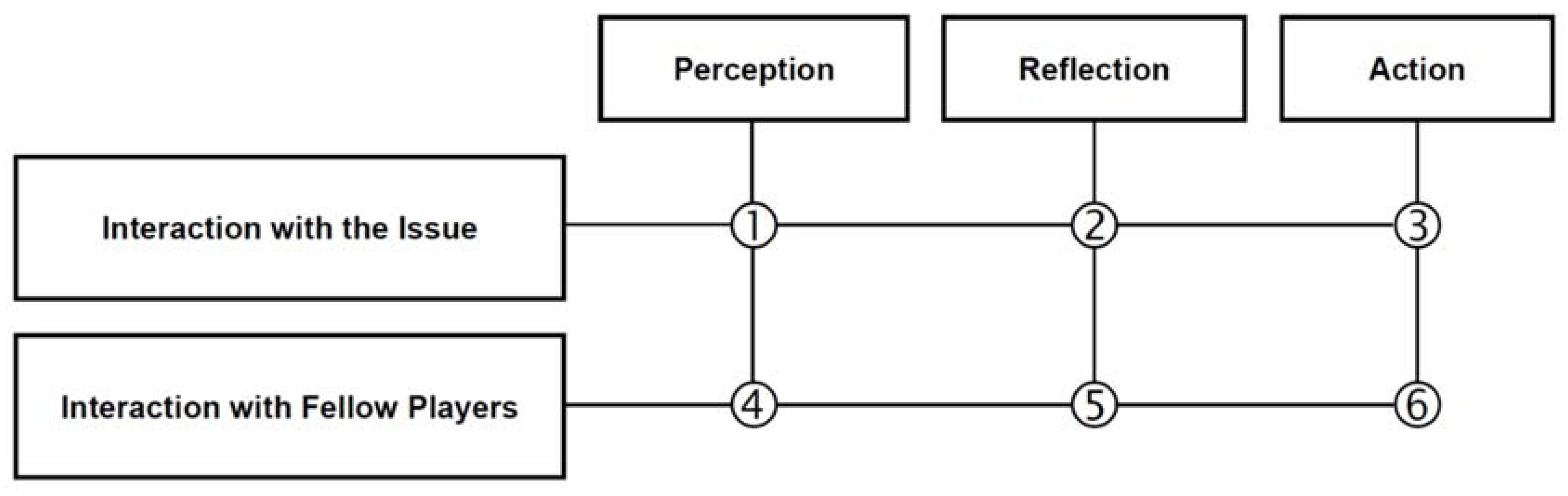

The first dimension represents interaction. Interaction has two levels: on the one hand the interaction with the issue and on the other interaction with fellow players. From an artistic point of view, interaction with the issue is the dialogue with the material out of which an art work arises. In the given context, it refers to handling the task, dealing with ideas and working with media in order to visualize solutions. The interaction with fellow players comprises any behaviour within the group or towards other participants during the process.

The second dimension represents three different aspects of doing. These are perception (information acquisition from the environment), reflection (scrutinizing, comparative consideration) and action (targeted activity including communicative action). In combination with the two levels of interaction, a grid of six categories arises (see

Figure 2) the findings are displayed in.

4.2. Findings on Interaction with the Issue

Category 1. Interaction with the Issue/Perception

The first category comprises sensory and cognitive perception relating to the issue and to (visualized) ideas, as far as it showed up in observable characteristics or behaviour.

The other participants described the artists as exceptionally alert and sensitive. The artists were observing intensely. However, it was noticeable that they often paused for a moment to take in impressions of the situation. In these minutes, they seemed to be slightly absent, cautious and thoughtful. It was the artists who were the first to perceive the change of the central problem.

The artists had different views and information filters. Whereas artist 1 always tried to see the big picture, artist 4 was attentive about little things. Artist 2 and 3 switched between overview and attention to detail.

Category 2. Interaction with the Issue/Reflection

The second category includes observations on how the participating artists processed information and sensory impressions and how they penetrated aspects intellectually and emotionally.

All artists handled impulses with unconditional openness. They welcomed every single idea, accepted and recorded it. There was no “No!” to them, no right or wrong. They were wary of premature evaluations or spontaneous refusal and played with the thoughts instead. The artists picked up all ideas and worked with them. Their reflection followed while they were dealing with a proposition.

The artists’ behaviour in a field phase is particularly noteworthy. At stage 5 of Art Hacking (showing), the working groups were prompted to obtain feedback from bystanders. Other than the other participants, the artists were not frustrated by negative comments on the draft at all. To them the criticism was important input that made them get back to work and enabled them to get closer to a sound solution.

I still have so many questions!

(Artist 2)

Every artist had a strong disposition to scrutiny. The artists enjoyed asking questions and in fact not only with the workshop elements that were meant to explore the core. Each had a different speed in developing questions; Artists 4, the improv player, was in her element and very quick. But all artists alike demonstrated analytical strength while asking prudent, profound questions—especially in stage 2 of Art Hacking (exploration) when it came down to accumulating questions.

The other participants tried to identify limits in order to obey any rule. Analogously: What are we allowed to do and what not? In contrast, queries from artists aimed at a better understanding of facts or the significance of a particular task: What does that mean? The artists scrutinized ideas and pointed out alternative meanings of an approach.

They questioned the meaning of facts and were aware both of different interpretations of reality and of possible consequences of certain views, including the unfavourable ones. All four had a distinct sense of imagery. The two actors (artists 3 and 4) stood out with their efforts to clarify the meaning of terms and state messages more precisely.

I don‘t like it that way. This is not consistent yet.

(Artist 4)

In the beginning the artists moved away from the supposed problem with their questions and opened up new perspectives. But later on, they repeatedly returned to the core and refined the solution in continuous reflection. In an advanced stage, they asked a genuinely artistic question: Is it consistent? When visualizing ideas and concepts, the artists did not hesitate to scrutinize approaches their fellow players had already agreed upon. Despite (or actually due to) being unfamiliar with specific business problems in their everyday working life, they played the role of neutral observers whose reflection process stimulated reflections with their fellow players.

Category 3. Interaction with the Issue/Action

The third category accumulates activities with regard to the issue and tasks in the process, respectively. It includes communicative activities like phrasing an idea or commenting on the thoughts of others.

One especially pronounced activity to be observed with the artists was documenting information and ideas. The two actors (artists 3 and 4) did so during the whole process; artist 2 at times. They took notes and made sketches for themselves but recorded for the group as well by visualizing the process and its interim results. Artist 1 worked on the written reminders of his group if they lacked structure.

Apart from that, the artists stood out by their inventiveness. They did not wonder very long but followed their intuition and communicated instant thoughts more often than other participants. Frequently they were the first ones to come forward with a proposal on an assignment. They were not reluctant to express spontaneous ideas nor afraid to dismiss unsuitable ideas after a while.

In general, their ideas were wittier and more original. Other participants commented on this in statements like: “Nobody else would have come up with such an idea.” The originality of their thoughts was particularly significant at the task to retrieve ideas they had turned down when they sprang to their minds because of their absurdity. While looking for analogies to the issue, this showed as well. Whereas other participants thought of a retirement home and a university, the artists suggested replacing the child day-care centre with a church, museum or zoo.

The artists were obviously moving beyond common ways of thinking. Given that they constantly changed thinking directions, the atmosphere within the groups relaxed. With unconventional ideas, both on the matter or working process the artists encouraged other players to leave their thought patterns and play with unusual ideas, too.

You will find ideas along the way.

(Artist 2)

The artists took up unpredictable impulses and ideas of others and guided the groups through a gradual process of content related concentration. Not only did they approve other ideas but reinforced them by verbal repetition. They picked up ideas and elaborated them by complementing a point or linking it to their own considerations.

Sometimes the artists consciously tried to distract the others from a certain aspect and open the space of possibilities. Later they led them back to the matter with fresh ideas found on the detour. To avoid getting bogged down in approaches, the artists would only ask questions that would return the search to the core problem from a certain point on.

Is our mission being merely creative or is it being clear and explicit, too?

(Artist 1)

For the artists, reduction was easier than for other participants. They used to structure ideas and interim results and were able to focus discussions and condense them to core ideas with general consensus. They clarified approaches and reduced them to the point, thereby striving to refine the message. The artists acted very process-oriented—and this process never seemed finished. They gave the joint activities momentum with striking statements that expressed their artistic work attitude. In doing so, they assumed the function of role models to others.

4.3. Interim Conclusion on Interaction with the Issue

Just do it. And later we will look at if it fits.

(Artist 1)

That the behaviour patterns observed in terms of perception, reflection and action are closely linked was especially apparent with creative assignments. The artists did not have a rational approach to such tasks; even in group work, they took action without thinking twice or discussing forms of depiction. For instance, when the participants were asked to visualize the problem with collage technique, all artists literally took matters into their own hands and grabbed some material. Basically, they started with an action followed by perception and appraisal of its effects. This was a strong message to their fellow players.

For the artists, it was important to start doing something and make anything happen—everything else would stem from that. One participant mentioned clearly: “[Artist 2] was not as highbrow as we were. She used to visualize and test the possibilities immediately: How can we do this? She took material in her hands at once, while the others were still talking about how you might do it.” The artists approached the tasks consciously and yet playfully without having a plan or a result in mind: “At first glance, it seemed as if [artist 3] had a plan. But she creates something and considers afterwards what it might be”.

The artists differed from other participants in not being afraid to make mistakes. Apparently, they did not fear failure, as failure did not have a negative connotation to them. If something did not work out creatively, they patiently checked out other approaches and dealt with barren ideas in a similar way. With many tasks, they had more endurance than other players—all the more even during periods of stagnation.

4.4. Findings on Interaction with Fellow Players

Category 4. Interaction with Fellow Players/Perception

Category 4 captures impressions that indicate how the artists perceived personal sensitivities and the joint process.

How do you see this?

(Artist 2)

The artists did not only demonstrate their distinct power of observation in dealing with the issue but in dealing with others as well. Participants characterized each of them as empathic. The artists had an open ear for everyone and were able to read between the lines both on a content-related and a personal level. They perceived in which mental state the others in the group were in and reacted to moods that threatened to affect the process, such as overall exhaustion. Artist 2 in particular was attentive when somebody had not participated in the joint work for some time and inquired as to the reason.

Category 5. Interaction with Fellow Players/Reflection

The fifth category displays in how far the artists reflected on their interplay with others and on cooperation behaviour within the group.

This is not about what I want but about exploiting the possibilities.

(Artist 2)

The artists are characterized by the ability to accept offers without prejudice and discrimination towards others. Unless they temporarily withdrew from the joint process, they got involved with their fellow players. It was obvious that they were aware of the prerequisites for successful collaboration including their personal responsibility, because in contrast to other participants they shaped the interchange consciously. In favour of the issue, they forwent dominating the process. However, they subtly took on leadership (see Category 6).

Every idea counts.

(Artist 3)

One element of Art Hacking is having the players define guidelines for good collaboration at stage 1 (attunement). With this task, some artists moderated the discussion actively. In general, the artists gave precedence to the idea over its initiator, thus fostering collaboration at eye level.

Those positive attitudes were in part thwarted by ignorance towards the effects of wayward behaviour. At times, two artists did not meet the expectations and backed out of tasks they did not like. One was aware of her rebellion, while the other was indifferent.

Category 6. Interaction with Fellow Players/Action

Category 6 is about how the artists acted and communicated with their fellow players.

Other participants described the artists as cautious actors who did not claim a special status for themselves. However, their strong presence and constructive behaviour made them secret leaders. With suitable tasks (object design, role play, etc.), they demonstrated their craft without taking centre stage, dispensing advice that was always supportive and reinforced their leading role. Aside from that, each of the four artists took the lead in their group’s work process in a sensitive way. They were always careful with their groups. The others perceived them as of equal rank while simultaneously being in a subtle leadership role.

Now, just be creative!

(Artist 1)

The artists motivated and challenged the others, not imposing their own ideas but stating them as offers, thereby scarcely noticeably pushing their decisions through. Oftentimes, those were first impulses and definitions that would promote the process. However, their target orientation considerably varied—time management was only an issue for artist 3. The artists began new stages in the work process, gently determined the direction and set impulses that allowed a change of perspective: “Without [artist 3] the group would have been spinning in a circle, because no one took the lead”.

“[Artist 1] was leading and guiding us through the creative process thus steering idea generation.” The artists took over moderating every now and then, structured ideas in support of their group or interfered at critical stages. However, they did not go it alone but fed back their suggestions and took the others along. Lastly, they pushed the process forward by asking questions like “What exactly do you want?” or “How would you like to express that?”

If the group was insecure—like with questioning bystanders at stage 5 of Art Hacking (showing)—even those artists who used to be cautious observers in other situations offensively went into a leading role. By springing into action, they absorbed the others’ hesitance. The same applies to situations in which the work process stagnated: In periods of crisis the artists took the initiative and drove the process forward with persistence: “When all of us sagged, [artist 1] rearranged our ideas so that there was some new input.” The artists took care that the groups did not lose their focus. They fetched the others back to the real issue when they were lost in discussion or drifting away from the current task. “When the group was stuck, [artist 4] tried to bring us back to the problem by asking questions”.

4.5. Interim Conclusion on Interaction with Fellow Players

The artists helped the other players to see possibilities that were not obvious and used several strategies to achieve a change of perspective and to get the groups going. They reversed ideas, incited to dreaming and “thinking big” or broke out, physically taking their fellow players to other places. During stage 4 of Art Hacking (composition), it was especially apparent that they conveyed their creative power to the groups. When the objects that were meant to symbolize the concept were built, all four artists were very active. After a short discussion about different ideas and methods, they instructed the others while quickly making clear choices.

As empathic process leaders, the artists took the role of primus inter pares. By taking care of their fellow players, they held their groups together. In doing so, they undermined a common prejudice: “Their cautious attitude surprised me. For some reason, I had the notion that artists are extrovert personalities who love to be in the limelight. In general, all four were always there for the collective and open to every proposal.”

5. Discussion

Beyond Art Hacking, there is little evidence regarding how artists conduct themselves in arts-based interventions that are about developing approaches for intra-organizational problems and setting an impulse for change. In two cases—in which artists designed and executed the intervention backed by a process leader responsible for the whole arrangement—the artists unfolded three main areas of competence in guiding the process: “technical competence, … competence to build trust [and,] … an open process orientation” [

27] (p. 45).

With Art Hacking, there were similar observations. While the artists applied basic craft techniques rather sparingly, they benefited from their special ability in passing through an open-ended, unbiased creative process. They succeeded in contributing to a relaxed situation and had the groups collaborate harmoniously. Whereas their technical advice was less important, their model function became a decisive factor in course of the process. They encouraged the other participants to engage themselves in unfamiliar working methods by demonstrating their artistic attitude, which goes way beyond being able to move in uncertain terrain.

During Art Hacking, the artists followed a course of action that is similar to the one that literature describes as genuinely artistic [

28,

38,

39,

48,

64,

65]. Essentially, the participating artists conducted themselves as if they were working on a piece of art by themselves. As far as generalizable basic attitudes to perception, reflection and action are concerned, they dealt with the assignment in a similar way. They adapted themselves to the situation without assuming the working styles of other participants. In the dimension of interaction with the issue, the artists remained absolutely authentic, thereby supporting the assumption they would use artistic attitudes in the intervention.

The artists met every problem with a positive approach. They did not hang on to any rules in order to obtain assurance but enjoyed facing the uncertain with intense susceptibility and in a proactive way [

28,

38,

39]. Similar to improvisation the artists instantly took up ideas and developed them further. They switched constantly between exploring suggestions and reflection on how they would fit into a concept [

48]. Decisions were not balanced rationally but made perceptively, situational and stepwise without having a certain goal in mind [

39]. The artists stayed focused on the issue, recognized incoherence and guided the process accordingly. Artists think in a medium, not imposing an idea on the process but finding it by dealing with the material [

64] in “a steady change between action and reaction, perception and action, question and answer” [

28] (p. 22, translation from German by the author).

The artists had a manifest strength in divergent thinking including fluency, flexibility, originality and elaboration [

45]. Although the extent of their individual creativity was not tested using methods such as the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking [

66], indications of pertinent mental abilities could be observed. The artists came up with a variety of unorthodox thoughts, promoted a change of perspective and organized the details of emerging ideas more often than other participants did. Beyond divergent thinking there were some other indications for creative thinking. These were the artists’ sensitivity to the issue as well as their ability to redefine the problem and to look beyond a single functional solution [

45]. Research on factors that facilitate visual artists’ creativity confirms that insight (selective combination and comparison) as well as divergent thinking are important aspects [

65].

Considering creativity not as an expression of personal characteristics but as a process, there are distinctions to be drawn between artistic ways of problem-solving and designerly ways of thinking. The latter are the paragon for Design Thinking, which conveys procedural elements from industrial design such as observation and understanding, draft and refinement to idea generation [

67]. In design, the concept determines the action, meaning that the idea is imposed on the process. Designers tend to act solution-oriented without necessarily exploring the whole range of possible approaches. In search for the simplest explanation for a problem, they eliminate obvious options step by step. As prototyping is a way to implement and test preconceived ideas, abstract requirements are translated into concrete objects [

68,

69]. In terms of logic of cognition, designerly thinking means abductive reasoning without calling the premise into question [

70]. Generally, the initial objective is not contested.

In contrast, the artists who were working in the Art Hacking framework applied behaviour patterns that are rooted in artistic labour. Playing with ideas and materials comes before rational judgement and integration into the bigger picture. For an artist, the objects created are media for deeply exploring the issue and developing even seemingly unreasonable solutions. This process seems to evade any logic and allows for expanding the solution space by asking radically different questions [

65,

71].

In general, artists score high on cognitive characteristics like self-criticism, openness to new experiences and risk-taking [

65]. In the fifth stage of the Art Hacking process (showing), the artists were more present than their fellow players. They were comparatively open to critique and took it as a starting point for further development. Along with their willingness to experiment and to accept potential failure this recognition indicates, that the artists’ self-conception is flexible in the sense of Dweck’s goal orientation theory [

72], which has proven useful for explaining the mechanisms of radical innovation.

Artists are said to be motivated by two drivers: either the wish to expose personal expression to an audience or an urge for learning in the course of creation: “artists who long to be seen and heard and artists who long to listen and understand” [

73] (p. 70). Although this distinct categorization must be doubted—a continuum seems more appropriate—, there is a promising link to Alexander and van Knippenberg’s model of successful team innovation. Among other factors, radical innovation success depends on the team’s willingness to prove their performance and on their learning ability. A performance prove orientation designates the desire to demonstrate competence and to receive public recognition, whereas a learning orientation comes to the fore through experimentation and fault tolerance. It is presumed that teams that share these goal orientations will conceive highly innovative ideas [

74]. Regarding Art Hacking or other arts-based interventions, the question is if and to what extent the artists succeeded in conveying their mindset to the other participants. This would be a promising area for psychological research.

Whereas the findings on “artistic idea generation” match descriptions of artistic labour, the group dynamics that unfolded during Art Hacking yielded some unexpected results: Every one of the four artists took leadership in their group, although there was no assignment to do so at all. In addition, none of the artists is a leader in their profession—none of them is a director, a choreographer or a conductor. It is no surprise that the two performance artists demonstrated a strong sense of co-creation but the visual artists did just the same although they are not used to working in a group.

While the author moderated the course of the whole workshop thus setting the frame, the artists guided the groups through idea generation. Although participants from different divisions and management levels met and despite of presumed differences in the social status between professionals and students, all groups explicitly went for a collaboration at eye level. In fact, the work process was obviously free from any hierarchy. However, the artists took the lead without enjoying a special status. If this coequal collaboration is to be attributed to targeted team building efforts as part of Art Hacking or if it is due to the artists’ social skills must remain unanswered at this point.

However, the artists’ leading role certainly goes beyond an emotional approach to dealing with uncertainty [

27]. Like every other participant, the artists did not know the format in advance. Nevertheless, they were able to deal with the open situation and the creative assignments effortlessly because of their professional experience. They demonstrated aesthetic skills, took the initiative with fluency, encouraged lateral thinking by coming up with original ideas and led the process while stimulating a change of perspective by profound questions. With their ability to structure and reduce the abundant material, they pushed the process towards a convincing solution without having a clearly defined mission. When the groups transferred their concepts into objects, the artists instructed their fellow players. Last but not least, their perseverance in crisis situations pulled the others along. Usually it was the artists who set impulses that allowed for progress.

In a process that was decisively dependent on creativity, their professional attitudes and artistic strategies elevated them to leadership simply because of their expertise. Their good instinct for the dynamics of the process turned them into moderators, pacesetters, facilitators and solicitors for artistic attitudes that the non-artistic workshop leader alone would very probably not have been able to similarly convey.

In Amabile’s componential model, individual and group-level creativity respectively depends on three major conditions: domain knowledge, creative skills and intrinsic task motivation [

75]. If at all, the artists’ intrinsic task motivation was potentially lower compared to other participants, because they were not faced with the initial problem in their professional life. Other than representatives and stakeholders of the organization that presented the problem, none but one of the artists had a direct personal connection to the issue let alone specific knowledge of the field. The artists had to rely on information they received from the participating experts.

This suggests that the artists’ informal leading role was primarily based on creative skills they unfolded in the process, namely personal characteristics such as a tolerance for risk, ambiguity and errors as well as cognitive strengths conducive to novel thinking [

75]. In turn, this leads to the proposition that in collective idea generation artists overcompensate knowledge gaps by their extraordinary creative skills. From the experts’ point of view, professional domain knowledge seems to be leveraged by artistic abilities and made fruitful for innovative solutions. This effect is a strong indication that artistic abilities can be effectively applied to demands for innovation.

The concept of Art Hacking is based on a premise shared by other proponents of arts-based interventions: artistic ways of working can be transferred to non-artistic settings [

8,

15,

76]. Some studies suggest that it is possible to achieve convincing results for business problems via mere “artistic experimentation” [

8] (p. 1516)—that is, by imitating creative techniques without having an artist around. According to subjective impressions of participants in one similar case, they were stepping out of their comfort zones while an innovation-friendly climate developed [

18]. Another case shows that organizations can successfully apply artistic practices in their own studio spaces without any personal artistic guidance at all [

77]. This is somewhat contrary to the multi-layered leadership position the artists took in Art Hacking. However, the settings are not directly comparable and there is no data on a run of Art Hacking without participating artists yet.

The fact that the artists took the lead in the process refers to research on collective creativity that suggests that leaders are less directive than integrative through dialogue and interaction [

78]. Creative leadership is described as “leading others toward the attainment of a creative outcome“ [

79] (p. 393). In Art Hacking the artists are not just mere facilitators, who foster the creative potential of their followers, or directors, who have others carry out their ideas. Their behaviour falls into a third conceptualization of creative leadership as a combination of facilitation and direction that stresses the creative process as a collaborative effort. This third strand highlights the creative leader as a person who integrates ideas by others with their own [

79].

Furthermore, the artists’ unexpected leadership qualities can be linked to the concept of “Leadership as Art” [

80], which pleads for an integration of artistic skills and attitudes into management. Accordingly, leadership should have an aesthetic dimension that comprises not only cognition and analytical knowledge but implicit knowledge, physical presence and expression through interaction as well. Artful leadership is based on expanded awareness and approves reflection dedicated to the endurance of ambiguity and contradiction [

80].

Regarding findings from psychological research on personality, the artists’ behaviour during Art Hacking is plausible at least as far as interaction with the issue—or even their willingness to participate—is concerned. Compared to scientists, who explore reality likewise, artists are more open, sensitive, non-conformist and original. Artists are seeking change and are open to experience [

81]. It stands to reason to involve them in idea generation, because of their very nature. “By being receptive to different perspectives, ideas, people and situations, open people are able to have at their disposal a wide range of thoughts, feelings and problem-solving strategies, the combination of which may lead to novel and useful solutions or ideas” [

81] (p. 300).

On the other hand, artists are demonstrably known for strong asocial tendencies such as introversion and hostility [

81]. Although one artist who participated in Art Hacking was prone to evade interaction, the overall experience seems to contradict this notion. Openness and flexibility might explain the cooperativeness the artists exploited.

6. Conclusions

Artists have distinguished art-making from their “way of organizing and acquiring knowledge” [

82] (27 s) by naming the latter Art Thinking [

82], whereas business people start using the term for a transfer of insights from the art into the business world. Inspired by the extensive discourse on Design Thinking [

83] the term Art Thinking is used to describe “a framework and set of habits to protect space for inquiry” [

84] (p. 12). In this sense, Art Thinking is just an arts-based view on management tools favouring divergent over coherent thinking [

84]. Art Thinking has not been conceptualized yet but it is characterized by “its focus on options, not outcomes; on possibilities, not certainty” [

85] (p. 16).

In contrast to this quite general view, Art Hacking is a specific creative method and problem-solving-activity based on the course of the artistic process, on artistic attitudes and strategies. Its lack of straightforwardness combined with a sensuous and playful approach makes it suitable for addressing determinate organizational problems. The key for a change of perspective is asking different questions, persistently scrutinizing the sense that is attributed to key variables and exploring absurd ideas. Art Hacking does not guarantee a particular result but it creates a framework that makes innovative approaches more likely to emerge. However, the present study did not aim at assessing the innovation process and putting the method to a comparative suitability test. The intention was to shed light on the role artists take in non-artistic co-creation with other professional groups.

Although data on this matter was not systematically collated, it is noteworthy that igniting sparks usually did not occur when the players were working on an assignment but while talking casually during breaks. Often it was not the flashy points that were decisive but secondary aspects and casual remarks. It was obviously helpful to have people around whose professional characteristics encompass a strong awareness and the ability to turn tiny starting points into a comprehensive body of work.

One central finding of the study at hand that was not stated in the literature as clearly and extensively before is the fact that the artists dealt with the business problem quite similarly to the creation of an artwork. They demonstrated that artistic working styles can successfully be applied to non-artistic tasks in particular with regard to those aiming at radical innovation. As highly creative persons, the artists unfolded creative skills and used artistic strategies despite the fact that they were not treading on familiar ground. They proved above-average innovative strength and pushed the process by offering different angles and stimuli towards action. This is what made the artists strong supporters of the first step towards innovation established with Art Hacking, namely idea generation.

Another insight other studies have not touched on at all yet is the artists’ leading role in the process. In other depicted cases, artists had developed the concept of the intervention and moderated the process. With Art Hacking, they had a different assignment. Surprisingly, the artists took the lead anyway, cautiously and persistently guiding their fellow players through the process by being role models in creative behaviour without reclaiming a special status within the group, acting out an integrative form of creative leadership instead.

As there are different leadership styles in the performance arts as well as in management, it would be interesting to explore that aspect both in the context of Art Hacking and regarding arts-based interventions in general. Are arts-based interventions more likely to succeed if there is a director or some other experienced creative leader involved? What are the effects of different creative leadership styles in innovative settings? And finally, is it necessary to have someone from the creative industries to enact creative leadership or can other people do likewise?

Other cases show that organizations can successfully apply artistic practices without any personal artistic guidance at all [

18,

77]. This possible contradiction to the findings presented here might be due to the limited generability of qualitative research and single case studies, respectively. Therefore, there is need for comparative research on the effectiveness of artistic conduct. Moreover, the different approaches to implement artistic attitudes and labour strategies in business settings deserve further research on success factors for applied artistic practice. At present, there is no research that opposes processes with artistic participation to interventions in control groups with respect to their innovative capacity.

However, there is evidence for the assumption that the active participation of artists during a collective innovation process is an effective catalyst. In any case, the leadership role the artists took in Art Hacking deserves a closer look, given that it would help debunk the outdated romantic myth of the artist as a lone genius with outsider status.