The Role of Depression and Anxiety in Frail Patients with Heart Failure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Definition of Key Concept

2.1. Frailty and Heart Failure

2.2. Assessment of Frailty

2.3. Psychological Factors and Heart Failure

2.3.1. Depression

2.3.2. Anxiety

2.4. Frailty and Psychological Factors in Heart Failure

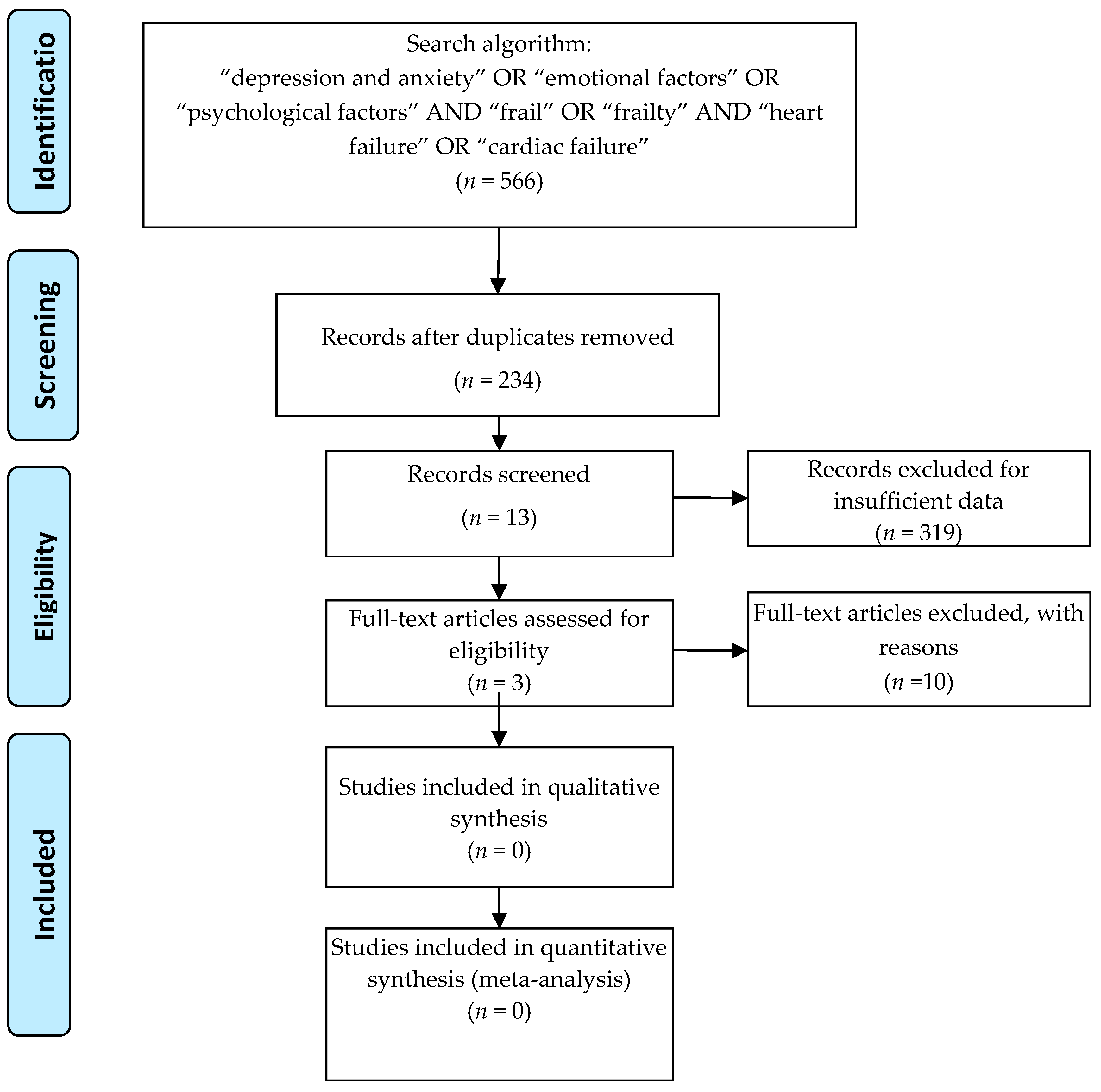

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Search Strategy

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Participants: only published articles enrolling adult patients (diagnosed) with HF, hospitalized or in an ambulatory setting.

- Assessment: HF participants screened for frailty and for depression and anxiety, regardless of the method used.

- Comparisons: control group of non-frail HF patients.

- Outcomes: clinical outcomes (readmission and mortality), functional status, QoL.

- Study design: observational studies, cross-sectional studies, randomized control studies.

3.3. Selection Criteria

3.4. Data Extraction

3.5. Quality Assessment of the Articles

4. Results

Search Result—Study Characteristics

- Studies on HF only = 14

- Studies on HF and frailty = 7

- Studies on frail individuals only = 31

- Recommendations/Guidelines/Position Statement = 17

- Review articles on different topics = 9

- Studies on elderly/geriatrics individuals = 53

- Studies on QoL (on different categories of individuals) = 16

- Pharmacological studies = 12

- Studies other than HF = 63

- Studies other than diseases = 49

- Studies on physical activity/rehabilitation programs = 22

- Frailty and Depression, but not anxiety = 8

- Anxiety and Depression, but not frailty = 5

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| HF | heart failure |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| QoL | quality of life |

| CHF | congestive heart failure |

| MMD | major depressive disorder |

| GDA | generalized anxiety disorder |

| PTSD | post-traumatic stress disorder |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| PCS | physical component scale |

| MCS | mental component scale |

References

- Singh, M.; Stewart, R.; White, H. Importance of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 1726–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.E.; Vellas, B.; Van Kan, G.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bauer, J.M.; Bernabei, R.; Cesari, M.; Chumlea, W.C.; Doehner, W.; Evans, J.; et al. Frailty consensus: A call to action. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, A.; Young, J.; Iliffe, S.; Rikkert, M.O.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013, 381, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, W.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Kawachi, I.; Rexrode, K.M.; Kroenke, C.H.; Glynn, R.J.; Garan, H.; Albert, C.M. Depression and risk of sudden cardiac death and coronary heart disease in women: Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacMahon, K.M.; Lip, G.Y. Psychological factors in heart failure: A review of the literature. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 162, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; Sun, Q.; Okereke, O.I.; Rexrode, K.M.; Hu, F.B. Depression and risk of stroke morbidity and mortality: A meta-analysis and systematic review. JAMA 2011, 306, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roose, S.P.; Dalack, G.W. Treating the depressed patient with cardiovascular problems. J. Clin. Psychiat. 1992, 53, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Strik, J.J.; Denollet, J.; Lousberg, R.; Honig, A. Comparing symptoms of depression and anxiety as predictors of cardiac events and increased health care consumption after myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 42, 1801–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frasure-Smith, N.; Lesperance, F.; Talajic, M. The impact of negative emotions on prognosis following myocardial infarction: Is it more than depression? Health Psychol. 1995, 14, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, V.L.; Weston, S.A.; Redfield, M.M.; Hellermann-Homan, J.P.; Killian, J.; Yawn, B.P.; Jacobsen, S.J. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA 2004, 292, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinmura, K. Cardiac senescence, heart failure, and frailty: A triangle in elderly people. Keio. J. Med. 2016, 65, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzman, D.W.; Little, W.C.; Brubaker, P.H.; Anderson, R.T.; Hundley, W.G.; Marburger, C.T.; Brosnihan, B.; Morgan, T.M.; Stewart, K.P. Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison with heart failure. JAMA 2002, 288, 2144–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, C.; Spoletini, I.; Rosano, G.M.C. Frailty in Heart Failure. Implications for Management. Card. Fail. Rev. 2018, 4, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Mao, G.; Leng, S.X. Frailty syndrome: An overview. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, K.; Song, X.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H.; Hogan, D.B.; McDowell, I.; Mitniski, A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulignano, G.; Del Sindaco, D.; Di Lenarda, A.; Tarantini, L.; Cioffi, G.; Gregori, D.; Tinti, M.D.; Monzo, L.; Minardi, G. Usefulness of frailty profile for targeting older heart failure patients in disease management programs: A cost-effectiveness, pilot study. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2010, 11, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afilalo, J.; Karunananthan, S.; Eisenberg, M.J.; Alexander, K.P.; Bergman, H. Role of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 103, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Haehling, S.; Lainscak, M.; Springer, J.; Anker, S.D. Cardiac cachexia: A systematic overview. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 121, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbens, R.J.; Luijkx, K.G.; Wijnen-Sponselee, M.T.; Schols, J.M. Towards an integral conceptual model of frailty. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2010, 14, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilotta, C.; Bowling, A.; Casè, A.; Nicolini, P.; Mauri, S.; Castelli, M.; Vergani, C. Dimensions and correlates of quality of life according to frailty status: A cross-sectional study on community-dwelling older adults referred to an outpatient geriatric service in Italy. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbens, R.J.; Luijkx, K.G.; Wijnen-Sponselee, M.T.; Schols, J.M. In search of an integral conceptual definition of frailty: Opinions of experts. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2010, 11, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, E.; Hoogendijk, E.O. Psychosocial factors modify the association of frailty with adverse outcomes: A prospective study of hospitalized older people. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaka, J.; Thompson, S.; Palacios, R. The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. J. Aging Health 2006, 18, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.; Yu, R.; Wong, M.; Yeung, F.; Wong, M.; Lum, C. Frailty screening in the community using the FRAIL scale. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, K.; Mitnitski, A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfson, D.B.; Majumdar, S.R.; Tahir, A.; Tsuyuki, R.T.; Rockwood, K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing 2006, 35, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, J.C.; Celano, C.M.; Beach, S.R.; Motiwalla, S.R.; Januzzi, J.L. Depression and cardiac disease: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and diagnosis. Cardiovasc. Psychiatry Neurol. 2013, 2013, 695925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murberg, T.A.; Bru, E.; Svebak, S.; Tveteraas, R.; Aarsland, T. Depressed mood and subjective health symptoms as predictors of mortality in patients with congestive heart failure: A two-years follow-up study. Int. J. Psychiatr. Med. 1999, 29, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, R.L.; Peden, A.R.; Lennie, T.A.; Scooler, M.P.; Mosser, D.K. Living with depressive symptoms: Patients with heart failure. Am. J. Crit. Care 2009, 18, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraska, A.R.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Shah, N.D.; Vickers, K.S.; Rummans, T.A.; Dunlay, S.M.; Spertus, J.A.; Weston, S.A.; McNallan, S.M.; Redfield, M.M.; et al. Depression, healthcare utilization, and death in heart failure: A community study. Circ. Heart Fail. 2013, 6, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedland, K.E.; Carney, R.M.; Rich, M.W. Impact of depression on prognosis in heart failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 2011, 7, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Shiga, T.; Kuwahara, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Suzuki, S.; Nishimura, K.; Suzuki, A.; Minami, T.; Ishigooka, J.; Kasanuki, H.; et al. Impact of clustered depression and anxiety on mortality and rehospitalization in patients with heart failure. J. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutledge, T.; Reis, V.A.; Linke, S.E.; Greenberg, B.H.; Mills, P.J. Depression in heart failure: A meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 48, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, M.H.; Hixon, M.E. Functional status, mood disturbance and quality of life in patients with heart failure. Prog. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 1994, 9, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, K.; Coventry, P.; Lovell, K.; Carter, L.A.; Deaton, C. Prevalence and measurement of anxiety in samples of patients with heart failure: Meta-analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, D.; Kronish, I.M.; Shaffer, J.A.; Falzon, L.; Burg, M.M. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk for coronary heart disease: A meta-analytic review. Am. Heart J. 2013, 166, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, S.L.; Abbey, S.E.; Irvine, J.; Shnek, Z.M.; Steward, D.E. Prospective examination of anxiety persistence and its relationship to cardiac symptoms and recurrent cardiac events. Psychother Psychosom 2004, 73, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.M.; Xue, Q.L.; Simpson, C.F.; Guralnik, J.M.; Fried, L.P. Frailty, hospitalization and progression of disability in a cohort of disabled older women. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 1225–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstam, V.; Moser, D.K.; De Jong, M.J. Depression and anxiety in heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 2005, 11, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, H.G. Depression and hospitalized older patients with congestive heart failure. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1998, 20, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.J.; Eisenberg, S.A.; Maeda, U.; Farell, K.A.; Schwartz, E.R.; Penedo, F.J.; Bauerlein, E.J.; Mallon, S. Depression and anxiety predict decline in physical health functioning in patients with heart failure. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011, 41, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbens, R.J.J.; Van Assen, M.A. The prediction of quality of life by physical, psychological and social components of frailty in community-dwelling older people. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 2289–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.M.; Griffin, J.A. Relationship of physical symptoms and physical functioning to depression in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung 2001, 30, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchmanowicz, I.; Gobbens, R.J. The relationship between frailty, anxiety and depression, and health-related quality of life in elderly patients with heart failure. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, L.D.; Scherrer, J.F.; Hauptman, P.J.; Freedland, K.E.; Chrusciel, T.; Balasubramanian, S.; Carney, R.M.; Newcomer, J.W.; Owen, R.; Buchholz, K.K.; et al. Association of anxiety disorders and depression with incident heart failure. Psychosom. Med. 2014, 76, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoreli, I.; Pauws, S.C.; Steyerberg, E.W.; de Vries, G.J.; Riistama, J.M.; Tesanovic, A.; Kazmi, S.; Pellicori, P.; Cleland, J.G.; Clark, A.L. Prognostic value of psychosocial factors for first and recurrent hospitalizations and mortality in heart failure patients: Insights from the OPERA-HF study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoreli, I.; de Vries, J.J.; Pauws, S.C.; Steyerberg, E.W. Depression and anxiety as predictors of mortality among heart failure patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail. Rev. 2016, 21, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denfeld, Q.E.; Stone, K.W.; Mudd, J.O.; Hiatt, S.O.; Lee, K.S. Identifying a relationship between physical frailty and heart failure symptoms. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2018, 33, E1–E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.J.; Seo, E.J. Depressive symptoms and physical frailty in older adults with chronic heart failure. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2018, 11, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, D.K.; Worster, P.L. Effect of psychosocial factors on physiologic outcomes in patients with heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2000, 14, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hobkirk, J.; Carroll, S.; Pellicori, P.; Clark, A.L.; Cleland, J.G.F. Exploring quality of life in patients with and without heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 202, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Studies | Reference Type | Location | Sample | Mean Age | Characteristics of Population | Assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frailty | Depression and Anxiety | ||||||

| Sokoreli 2018 | Ongoing prospective observational study | UK | 779 participants hospitalized for HF | 75 (67–82) | treatment with loop diuretics and LVEF ≤ 40 | 1. questions about having trouble with bathing and dressing 2. TUG test < 10 s normal > 20 s abnormal | HADS questionnaire Scoring: < 7 no depression or anxiety 8–10 mild depression or anxiety > 11 moderate-to-severe depression or anxiety |

| Denfeld 2017 | Prospective cross-sectional study | USA | 49 participants (outpatient and inpatient) scheduled for a right heart catheterization | 57.4 ± 9.7 | NYHA III or IV, non-ischemic HF | 1. Shrinking (self-report) 2. Weakness (5-repeat chair stands) 3. Slowness (4 m Gait speed) 4. Physical exhaustion (FACIT-F) 5. Level of physical activity (one question) | Depression: 9-item PHQ (valid and reliable measurement of depression in HF) Scoring (range 0–27): 10 = moderate depression > 10 greater depression Anxiety: 6-item BSI (valid and reliable measure of anxiety in HF) Scoring (range 0–4): 4 = worse anxiety |

| Uchmanowicz 2015 | Single-centre observational cohort study | Poland | 100 participants | non-frail, 62.3 ± 6.2 years; frail, 67.9 ± 10.7 years | > 60 years, with a diagnosis of HF, enrolled from clinic |

TFI scale (Polish version) with 15-self-reported questions regarding:

1. physical domain (0–8 points) 2. psychological domain (0–4 points) 3. social domain (0–3 points) | HADS questionnaire Scoring: < 7 no depression or anxiety 8–10 mild depression or anxiety > 11 moderate-to-severe depression or anxiety |

| Studies | Sokorelli, 2018 | Denfeld, 2017 | Uchmanowicz, 2015 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Yes | No | Other (CD, NR, NA) * | Yes | No | Other (CD, NR, NA) * | Yes | No | Other (CD, NR, NA) * |

| 1. Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated? | x | x | x | ||||||

| 2. Was the study population clearly specified and defined? | x | small sample | small sample, recruited from a single center, 89% of the patients were frail | ||||||

| 3. Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%? | NR | NR | NR | ||||||

| 4. Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants? | x | x | x | ||||||

| 5. Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided? | x | x | x | ||||||

| 6. For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured? | x | x | x | ||||||

| 7. Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed? | x | x | x | ||||||

| 8. For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)? | x | x | x | ||||||

| 9. Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | x | x | x | ||||||

| 10. Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| 11. Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | x | x | x | ||||||

| 12. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants? | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

| 13. Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? | x | NA | NA | ||||||

| 14. Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)? | x | x | x | ||||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hiriscau, E.I.; Bodolea, C. The Role of Depression and Anxiety in Frail Patients with Heart Failure. Diseases 2019, 7, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases7020045

Hiriscau EI, Bodolea C. The Role of Depression and Anxiety in Frail Patients with Heart Failure. Diseases. 2019; 7(2):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases7020045

Chicago/Turabian StyleHiriscau, Elisabeta Ioana, and Constantin Bodolea. 2019. "The Role of Depression and Anxiety in Frail Patients with Heart Failure" Diseases 7, no. 2: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases7020045

APA StyleHiriscau, E. I., & Bodolea, C. (2019). The Role of Depression and Anxiety in Frail Patients with Heart Failure. Diseases, 7(2), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases7020045