Impacts of Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku) in Female Participants with Depression/Depressive Tendencies

Abstract

1. Introduction

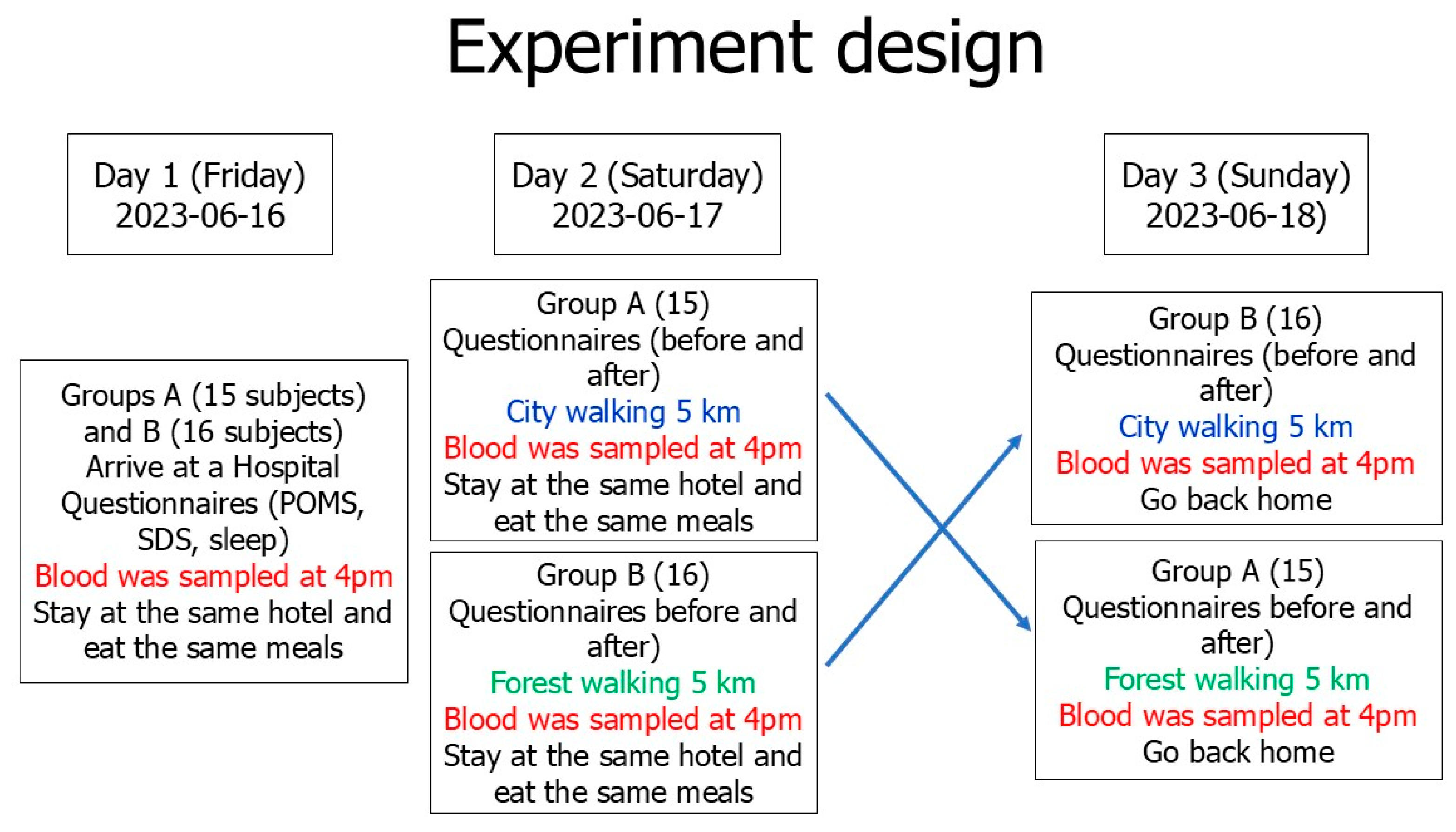

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Forest Bathing and Urban Walks

- Increased efficiency: Each participant serves as their own control, which minimizes the variability caused by differences between individuals. This requires fewer participants to achieve statistically significant results.

- Direct comparisons: Participants receive the interventions (forest bathing and city walking) in a randomized order, making it easier to compare the effects of different interventions directly.

- Control of individual differences: Since each participant experiences both interventions (forest bathing and city walking), the design controls for individual differences in response to interventions, leading to more reliable results.

- Cost-effectiveness: With fewer participants needed, the overall costs of the study can be reduced, making it more feasible to conduct.

- Because we used the randomized crossover design, all subjects experienced forest bathing and urban walking, even though the participants experienced the forest and city treatments on different dates. The differences in participants’ responses to the two different environments could be analyzed.

- Carryover effects: There is a risk that the effects of one treatment may carry over into the next period, potentially confounding results.

- Not suitable for all conditions: Crossover designs may not be appropriate for treatments that have long-lasting effects or when the condition being studied cannot be reversed.

- Dropout issues: If participants drop out after receiving one treatment, it can lead to imbalances in the groups and affect the validity of the results.

2.3. Blood Tests and Questionnaire Surveys

2.3.1. Serotonin in Serum

2.3.2. Oxytocin in Plasma

2.3.3. Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) Concentration in Plasma

2.3.4. Lactic Acid Concentration in Serum

2.3.5. SDS Scores

2.3.6. POMS Test

2.3.7. Questionnaire for Subjective Fatigue Symptoms

2.3.8. Questionnaire for Subjective Sleep Quality

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Walking Time, Distance, and Speed

3.2. Lactic Acid Concentrations in Serum During the Forest Bathing and Urban Area Walking

3.3. Impacts of Forest and City Walks on Blood Serotonin

3.4. Impacts of Forest and City Walks on Blood Oxytocin

3.5. Impacts of Forest and City Walks on Blood IGF-1

3.6. Impacts of Forest and City Walks on SDS Scores

3.7. Impacts of Forest and City Walks on the Scores in the POMS

3.8. Impacts of Forest Bathing on Subjective Fatigue Symptom Scores

3.9. Impact of Forest and City Walks on Subjective Sleep Quality

4. Discussion

Limitations

- Participants were recruited from three different clinics in Tokyo and Kawasaki. The geographic location or specific characteristics of these clinics may affect the generalizability of the results to a broader population of women with depression in other regions or countries. However, this is a field study, and recruiting subjects was very difficult as needed to participate in a three-day, two-night trip. The representativeness of these three clinics is a study limitation.

- Only female participants were investigated, and male participants with depression should also be investigated. We intend to conduct a study including male participants with depression next time.

- As another limitation of this study, various factors such as deep breathing, differences between forest and urban in ambient illuminance, temperature, and humidity, the inclines and declines during walking and the conditions underfoot while walking, may affect blood serotonin and oxytocin concentrations and symptoms of depression; however, in this study, it was not possible to exclude the influence of some of these factors. In addition, this study was a field study, not a laboratory experiment; therefore, it is difficult to control all confounding factors. This should be addressed in the future research. However, both the city walking route (Figure 4) and the forest walking route (Figure 2 and Figure 3) are flat roads, and the forest walking route is wheelchair accessible. Therefore, the impact of the differences in the inclines and declines between city walks and forest walks should be limited. In fact, the effects of forest bathing are the total effect of the forest environment, including the quiet atmosphere, beautiful scenery, calm climate, pleasant aromas, and clean fresh air compared with city environments.

- The number of participants was only 31 and more participants should be investigated. However, since the forest bathing study measures many indicators in a field study, the number of participants is limited in one experiment. In addition, all participants had to stay at the same hotel to control their diet; however, there is no bigger hotel in Akasawa Shizen Kyuyourin and the hotel has a limited capacity, with a maximum of 31 subjects. In addition, it is necessary to keep a distance between the subjects when walking in the city, and when there are many people, the traffic will be affected; therefore, permission from the city authorities could be obtained. In consideration of various factors, the number of participants was finally limited to 31. On the other hand, although the number of participants was only between 12 and 20 [3,4,14] in our previous studies, statistically significant differences were obtained.

- In this study, we examined how much forest bathing and urban walking changed each indicator compared to the baseline measures. We took several measures to minimize potential biases in the baseline assessments as much as possible. However, it is difficult to eliminate all potential bias in the baseline assessment in a field survey. This is also one of the limitations of this study.

- It is the first study to find that forest bathing increased blood serotonin, oxytocin and IGF-1 in females with depression/depressive tendencies.

- This study is also the first to find that forest bathing improves SDS scores in female participants with depression/depressive tendencies. The impact was sustained for one week after forest bathing.

- We used a randomized crossover research design to eliminate order bias and improve the statistical efficiency [14]. Although the impacts of the first forest bathing may have an impact on the city walking next day, even in this situation, forest bathing was found to be more effective at improving depressive symptoms and other indicators than city walking; therefore, this design does not affect the conclusions of this study, as there may be an underestimation, but no overestimation, of the impacts of forest bathing.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Improvement in oxytocin, serotonin and IGF-1 in blood.

- (2)

- Improvement in SDS, the effect of which lasted for one week.

- (3)

- Improvement subjective sleep quality as assessed by the OSA-MA.

- (4)

- Decrease in negative moods and increase in positive feelings of vigor and friendliness in the POMS test.

- (5)

- Improvement in subjective fatigue symptoms.

6. Directions for Future Research

- (1)

- In the next phase of research, we plan to conduct a study on males with depression or participants with other mental illnesses.

- (2)

- We would like to recommend exploring brain-derived neurotrophic factor and measurement of cerebral blood flow to strengthen the evidence for the therapeutic potential of forest bathing in future research.

- (3)

- The present study was conducted in June, a time when both deciduous and evergreen trees emit phytoncides, which, when inhaled, could have a role in improving the studied parameters. We have previously conducted forest bathing experiments in this forest in autumn (September) [3], but have not conducted an experiment in winter. This will be the subject of future research. However, phytoncides in the air of this forest throughout the four seasons have been measured and the concentration of phytoncides was very low in winter [69].

- (4)

- Future clinical research will verify the improvement of depression through forest bathing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Q. Effects of forest environment (Shinrin-yoku/Forest bathing) on health promotion and disease prevention—The Establishment of ‘Forest Medicine’. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2022, 27, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q. (Ed.) Forest Medicine; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–316. Available online: https://novapublishers.com/shop/forest-medicine/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Li, Y.; Wakayama, Y.; et al. Visiting a forest, but not a city, increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2008, 21, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Shimizu, T.; Li, Y.J.; Wakayama, Y.; et al. A forest bathing trip increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins in female subjects. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2008, 22, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Otsuka, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Wakayama, Y.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Li, Y.J.; Hirata, K.; Shimizu, T.; et al. Acute effects of walking in forest environments on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 2845–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.J.; Miyazaki, Y. Trends in research related to “Shinrin-yoku” (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing) in Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Deguchi, M.; Miyazaki, Y. The effects of exercise in forest and urban environments on sympathetic nervous activity of normal young adults. J. Int. Med. Res. 2006, 34, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.J.; Ishii, H.; Hirano, H.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest) in an old-growth broadleaf forest in Yamagata Prefecture, Japan. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2007, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuyashiki, A.; Tabuchi, K.; Norikoshi, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Oriyama, S. A comparative study of the physiological and psychological effects of forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku) on working age people with and without depressive tendencies. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.P.; Lin, C.M.; Tsai, M.J.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chen, C.Y. Effects of Short Forest Bathing Program on Autonomic Nervous System Activity and Mood States in Middle-Aged and Elderly Individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Ohira, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Effect of forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Public Health 2011, 125, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queirolo, L.; Fazia, T.; Roccon, A.; Pistollato, E.; Gatti, L.; Bernardinelli, L.; Zanette, G.; Berrino, F. Effects of forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku) in stressed people. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1458418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ochiai, H.; Ochiai, T.; Takayama, N.; Kumeda, S.; Miura, T.; Aoyagi, Y.; Imai, M. Effects of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on serotonin in serum, depressive symptoms and subjective sleep quality in middle-aged males. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2022, 27, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Depression. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). Available online: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/d780dffbe8a381b25e1416884959e88b (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Tao, R.; Li, H. High serum uric acid level in adolescent depressive patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 174, 464–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidina, T.V.; Trushnikova, T.N.; Danilova, M.A. Interferon-induced depression and peripheral blood serotonin in patients with multiple sclerosis. Zhurnal Nevrol. I Psikhiatrii Im. S.S. Korsakova 2018, 118, 77–81, (Article in Russian; Abstract in English). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, A.; Rajkumar, R.P.; Shewade, D.G.; Sundaram, R.; Muthuramalingam, A.; Paul, A. Evaluation of interleukin-6 and serotonin as biomarkers to predict response to fluoxetine. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 31, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworek, A.K.; Jaworek, M.; Makara-Studzińska, M.; Szafraniec, K.; Doniec, Z.; Szepietowski, J.; Wojas-Pelc, A.; Pokorski, M. Depression and Serum Content of Serotonin in Adult Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Montes, L.G.; Valles-Sanchez, V.; Moreno-Aguilar, J.; Chavez-Balderas, R.A.; García-Marín, J.A.; Cortés Sotres, J.F.; Hheinze-Martin, G. Relation of serum cholesterol, lipid, serotonin and tryptophan levels to severity of depression and to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2000, 25, 371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Moroianu, L.A.; Cecilia, C.; Ardeleanu, V.; Pantea Stoian, A.; Cristescu, V.; Barbu, R.E.; Moroianu, M. Clinical Study of Serum Serotonin as a Screening Marker for Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Medicina 2022, 58, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Kim, Y.K. The Role of the Oxytocin System in Anxiety Disorders. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1191, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsoy, S.; Esel, E.; Kula, M. Serum oxytocin levels in patients with depression and the effects of gender and antidepressant treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 169, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, L.; Carolino, E.; Santos, I.; Veríssimo, C.; Almeida, A.; Grilo, A.; Brito, M.; Santos, M.C. Depressive symptomatology, temperament and oxytocin serum levels in a sample of healthy female university students. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.W.; Garner, J.P.; Carson, D.S.; Keller, J.; Lembke, A.; Hyde, S.A.; Kenna, H.A.; Tennakoon, L.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Parker, K.J. Plasma oxytocin concentrations are lower in depressed vs. healthy control women and are independent of cortisol. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 51, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, T.; Uysal, C.; Asdemir, A.; Kiliç, E. May oxytocin be a trait marker for bipolar disorder? Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 2890–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trejo, L.J.; Carro, E.; Torres-Aleman, I. Circulating insulin-like growth factor I mediates exercise-induced increases in the number of new neurons in the adult hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberg, N.D.; Brywe, K.G.; Isgaard, J. Aspects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I related to neuroprotection, regeneration, and functional plasticity in the adult brain. Sci. World J. 2006, 6, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempin, F.; Beis, D.; Mosienko, V.; Kempermann, G.; Bader, M.; Alenina, N. Serotonin is required for exercise-induced adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 8270–8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M. Molecular Mechanisms of Exercise-induced Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Antidepressant Effects. JMA J. 2023, 6, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S.; Tokuda, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Sawai, H.; Shibahara, H.; Takeshima, Y.; Shima, M. Association between the serum insulin-like growth factor-1 concentration in the first trimester of pregnancy and postpartum depression. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 75, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş Dürmüş, P.; Vardar, M.E.; Kaya, O.; Tayfur, P.; Süt, N.; Vardar, S.A. Evaluation of the Effects of High Intensity Interval Training on Cytokine Levels and Clinical Course in Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. Turk. Psikiyatri. Derg. 2020, 31, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zung, W.W.; Richards, C.B.; Short, M.J. Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic. Further validation of the SDS. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1965, 13, 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman, M.V. Psychopathology in women and men: Focus on female hormones. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 1641–1647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weissman, M.M.; Klerman, G.L. Sex differences and the epidemiology of depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1977, 34, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory. Psychol. Bull. 1987, 101, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brody, D.J.; Pratt, L.; Hughes, J. Prevalence of Depression Among Adults Aged 20 and over: United States, 2013–2016; NCHS Data Brief No. 303; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db303.htm (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Kanda, F.; Oishi, K.; Sekiguchi, K.; Kuga, A.; Kobessho, H.; Shirafuji, T.; Higuchi, M.; Ishihara, H. Characteristics of depression in Parkinson’s disease: Evaluating with Zung’s Self-Rating Depression Scale. Park. Relat. Disord. 2008, 14, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kazama, S.; Kazama, J.J.; Wakasugi, M.; Ito, Y.; Narita, I.; Tanaka, M.; Horiguchi, F.; Tanigawa, K. Emotional disturbance assessed by the Self-Rating Depression Scale test is associated with mortality among Japanese Hemodialysis patients. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2018, 64, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, A.; McCabe, P.M.; Nation, D.A.; Tabak, B.A.; Rossetti, M.A.; McCullough, M.E.; Schneiderman, N.; Mendez, A.J. Evaluation of enzyme immunoassay and radioimmunoassay methods for the measurement of plasma oxytocin. Psychosom. Med. 2011, 73, 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Takase, M.; Yamazaki, K.; Azumi, K.; Shirakawa, S. Standardization of revised version of OSA sleep inventory for middle age and aged. Brain Sci. Ment. Disord. 1999, 10, 401–409. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Japan Organization of Better Sleep. OSA Sleep Inventory MA Version. Available online: https://www.jobs.gr.jp/osa_ma.html (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Wakui, N.; Togawa, C.; Ichikawa, K.; Matsuoka, R.; Watanabe, M.; Okami, A.; Shirozu, S.; Yamamura, M.; Machida, Y. Relieving psychological stress and improving sleep quality by bergamot essential oil use before bedtime and upon awakening: A randomized crossover trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2023, 77, 102976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Ju, H.J.; Jang, B.J.; Wang, T.K.; Kim, Y.I. Effect of Forest Therapy for Menopausal Women with Insomnia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawada, T.; Li, Q.; Nakadai, A.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Shimizu, T.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H. Chapter 8. Effect of forest bathing on sleep and physical activity. In Forest Medicine; Li, Q., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 25–34, 104–107. Available online: https://novapublishers.com/shop/forest-medicine/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Elhwuegi, A.S. Central monoamines and their role in major depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 28, 435–451. [Google Scholar]

- Holck, A.; Wolkowitzb, O.M.; Mellonc, S.H.; Reusb, V.I.; Nelsonb, J.C.; Westrina, Å.; Lindqvista, D. Plasma serotonin levels are associated with antidepressant response to SSRIs. J. Afect. Disord. 2019, 250, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, J.C.; Gluck, N.; Fallet, A.; Grégoire, A.; Chevalier, J.F.; Advenier, C.; Spreux-Varoquaux, O. Plasma serotonin level after 1 day of fluoxetine treatment: A biological predictor for antidepressant response? Psychopharmacology 1999, 143, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Neavin, D.; Liu, D.; Biernacka, J.; Hall-Flavin, D.; Bobo, W.V.; Frye, M.; Skime, M.; Jenkins, G.D.; Batzler, A.; et al. TSPAN5, ERICH3 and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depressive disorder: Pharmacometabolomics-informed pharmacogenomics. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 1717–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djalovski, A.; Kinreich, S.; Zagoory-Sharon, O.; Feldman, R. Social dialogue triggers biobehavioral synchrony of partners’ endocrine response via sex-specific, hormone-specific, attachment-specific mechanisms. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.S.; Kenkel, W.M.; MacLean, E.L.; Wilson, S.R.; Perkeybile, A.M.; Yee, J.R.; Ferris, C.F.; Nazarloo, H.P.; Porges, S.W.; Davis, J.M.; et al. Is Oxytocin “Nature’s Medicine”? Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 829–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.M.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, J.; Yu, Y. The relationship between sleep efficiency and clinical symptoms is mediated by brain function in major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddie, D.; Bentley, K.H.; Bernard, R.; Yeung, A.; Nyer, M.; Pedrelli, P.; Mischoulon, D.; Winkelman, J.W. Major depressive disorder and insomnia: Exploring a hypothesis of a common neurological basis using waking and sleep-derived heart rate variability. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 123, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, E.; Imai, M.; Okawa, M.; Miyaura, T.; Miyazaki, S. A before and after comparison of the effects of forest walking on the sleep of a community-based sample of people with sleep complaints. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2011, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, E.; Kadotani, H.; Yamada, N.; Sasakabe, T.; Kawai, S.; Naito, M.; Tamura, T.; Wakai, K. The Inverse Association between the Frequency of Forest Walking (Shinrin-yoku) and the Prevalence of Insomnia Symptoms in the General Japanese Population: A Japan Multi-Institutional Collaborative Cohort Daiko Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Yu, S.; Xia, L.; Ying, M. Effect of Forest-Based Health and Wellness on Sleep Quality of Middle-Aged People. J. Sens. 2022, 2022, 1553716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Zhang, D. Impact of sleeping in a forest on sleep quality and mental well-being. Explore 2024, 20, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, M.; Lim, P.J.; Tsubosaka, M.; Kim, H.K.; Miyashita, M.; Suzuki, K.; Tan, E.L.; Shibata, S. Effects of increased daily physical activity on mental health and depression biomarkers in postmenopausal women. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2019, 31, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, B.; Cheng, D.; Clark, S.; Camargo, A.J. Positive association between altitude and suicide in 2584 U.S. counties. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2011, 12, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kious, B.M.; Bakian, A.; Zhao, J.; Mickey, B.; Guille, C.; Renshaw, P.; Sen, S. Altitude and risk of depression and anxiety: Findings from the intern health study. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2019, 31, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Z. A Large Sample Survey of Tibetan People on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Current Situation of Depression and Risk Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjrek, E.; Friedrich, M.E.; Cambioli, L.; Dold, M.; Jäger, F.; Komorowski, A.; Lanzenberger, R.; Kasper, S.; Winkler, D. The Efficacy of Light Therapy in the Treatment of Seasonal Affective Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 89, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazienė, A.; Venclovienė, J.; Vaičiulis, V.; Lukšienė, D.; Tamošiūnas, A.; Milvidaitė, I.; Radišauskas, R.; Bobak, M. Relationship between Depressive Symptoms and Weather Conditions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kobayashi, M.; Wakayama, Y.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Shimizu, T.; Kawada, T.; Park, B.; et al. Effect of phytoncide from trees on human natural killer cell function. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2009, 22, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, V.; Scognamiglio, P.L.; Caruso, U.; Vicidomini, C.; Roviello, G.N. Evaluating In Silico the Potential Health and Environmental Benefits of Houseplant Volatile Organic Compounds for an Emerging ‘Indoor Forest Bathing’ Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zildzic, M.; Salihefendic, D.; Masic, I. Non-Pharmacological Measures in the Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19 Infection. Med. Arch. 2021, 75, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Shinrin-yoku: The Art and Science of Forest Bathing; Penguin Random House UK: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ohira, T.; Matsui, N. Chapter 3. Phytoncides in forest atmosphere. In Forest Medicine; Li, Q., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 25–34. Available online: https://novapublishers.com/shop/forest-medicine/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

| Degree of | Condition | (Score) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Questions | No | Sometimes | Quite Often | Almost Always | Scores |

| 1 | Depressed affect | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 2 | Diurnal variation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 3 | Crying spells | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 4 | Sleep disturbance | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 5 | Decreased appetite | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 6 | Decreased libido | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 7 | Weight loss | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 8 | Constipation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 9 | Tachycardia | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 10 | Fatigue | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 11 | Confusion | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 12 | Psychomotor retardation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 13 | Agitation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 14 | Hopelessness | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 15 | Irritability | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 16 | Indecisiveness | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 17 | Personal devaluation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 18 | Emptiness | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 19 | Suicidal ideation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 20 | Dissatisfaction | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Total |

| Group A (n = 15) | Group B (n = 16) | p Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 40.7 | 14.0 | 39.6 | 12.5 | >0.05 |

| SDS (Recruit) * | 50.3 | 6.7 | 50.3 | 5.7 | >0.05 |

| Depression-related medications # | 11/15 | 11/16 | >0.05 | ||

| Smoking # | 2/15 | 2/16 | >0.05 | ||

| Alcohol # | 4/15 | 5/16 | >0.05 | ||

| Daily exercise habits # | 7/15 | 9/16 | >0.05 | ||

| Sleep time (h) | 6.6 | 1.1 | 6.8 | 1.1 | >0.05 |

| WBC (×103/μL) | 5.9 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 1.9 | >0.05 |

| RBC (×106/μL) | 4.3 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 0.3 | >0.05 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.4 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 0.9 | >0.05 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 37.8 | 2.9 | 38.8 | 2.3 | >0.05 |

| Platelet (×103/μL) | 264 | 83.5 | 231.4 | 52.0 | >0.05 |

| Forest Area | City Area | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a.m. | p.m. | a.m. | p.m. | ||

| 17 June (Day 1) | Time | 10:01–11:26 | 12:45–14:09 | 09:59–11:25 | 12:44–14:13 |

| Walking time | 1:25:16 | 1:24:44 | 1:26:01 | 1:29:36 | |

| Distance (km) | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.3 | |

| Speed (km/h) | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | |

| Altitude (m) | 1110–1158 | 1101–1166 | 633–646 | 632–645 | |

| 18 June (Day 2) | Time | 10:00–11:28 | 12:45–14:12 | 10:01–11:26 | 12:45–14:12 |

| Walking time | 1:28:52 | 1:27:03 | 1:25:09 | 1:27:47 | |

| Distance (km) | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | |

| Speed (km/h) | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | |

| Altitude (m) | 1110–1165 | 1112–1171 | 634–647 | 631–645 | |

| Illuminance (lx) | Temperature (°C) | Humidity (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sites | Group | N | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Forest on 17 June | B | 360 | 16,173.2 ** | 28,937.2 | 23.8 ** | 2.9 | 49.7 ** | 10.3 |

| City on 17 June | A | 338 | 56,398.4 | 49,372.2 | 34.2 | 4.3 | 23.4 | 8.4 |

| Forest on 18 June | A | 386 | 12,096.1 ** | 20,389.8 | 24.1 ** | 3.6 | 58.8 ** | 14.8 |

| City on 18 June | B | 335 | 58,500.1 | 33,539.2 | 34.9 | 4.2 | 26.6 | 7.1 |

| No. | Questions | Not at All | A Little | A Fair Amount | Quite a Lot | Very Much |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I enjoy socializing | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | I feel tense | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | I feel angry | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | I feel exhausted | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | I feel lively | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6 | I feel confused | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7 | I care about others | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8 | I feel sad | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9 | I feel positive | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10 | I feel depressed | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11 | I feel full of energy | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12 | I feel confused | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13 | I feel hopeless | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14 | I feel anxious | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 15 | I can’t concentrate | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 16 | I’m tired | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 17 | I feel like I can be useful to others | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 18 | I feel nervous | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 19 | I feel miserable | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 20 | I can’t think clearly | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 21 | I’m exhausted | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 22 | I feel really angry inside | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 23 | I worry about things | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 24 | I can be kind to others | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 25 | I can’t do anything myself | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 26 | I feel fed up | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 27 | I feel helpless | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 28 | I feel very angry | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 29 | I trust others | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 30 | I get angry easily | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 31 | I feel worthless | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 32 | I feel energized | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 33 | I’m not sure about things | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 34 | I’m exhausted | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 35 | I’m full of motivation | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Name of participant: | Date: | ||||||||

| I would like to ask you about your current situation. If you have any of the following symptoms, please enter 1. If not, please enter 0. | |||||||||

| Group I | Group II | Group III | |||||||

| No. | Symptoms | Score | No. | Symptoms | Score | No. | Symptoms | Score | |

| 1 | My head is heavy | 1 or 0 | 11 | I can’t think straight | 1 or 0 | 21 | I have a headache | 1 or 0 | |

| 2 | My whole body feels tired | 1 or 0 | 12 | I don’t like talking | 1 or 0 | 22 | My shoulders are stiff | 1 or 0 | |

| 3 | My legs feel tired | 1 or 0 | 13 | I am frustrated | 1 or 0 | 23 | I have lower back pain | 1 or 0 | |

| 4 | I yawn | 1 or 0 | 14 | Make more mistakes in doing | 1 or 0 | 24 | It’s hard to breathe | 1 or 0 | |

| 5 | My brain is foggy | 1 or 0 | 15 | I am distracted | 1 or 0 | 25 | I am thirsty | 1 or 0 | |

| 6 | Sleepy | 1 or 0 | 16 | I can’t be enthusiastic about things | 1 or 0 | 26 | My voice becomes hoarse | 1 or 0 | |

| 7 | My eyes get tired | 1 or 0 | 17 | I can’t remember little things | 1 or 0 | 27 | I feel dizzy | 1 or 0 | |

| 8 | My movement is clumsy | 1 or 0 | 18 | I care about things | 1 or 0 | 28 | My eyelids and muscles twitch | 1 or 0 | |

| 9 | I can’t rely on my feet | 1 or 0 | 19 | I can’t stay tidy | 1 or 0 | 29 | My limbs tremble | 1 or 0 | |

| 10 | I want to lie down | 1 or 0 | 20 | I’m running out of patience | 1 or 0 | 30 | I don’t feel well | 1 or 0 | |

| No. | Question Items | Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Almost Always | Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I still felt tired | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | I couldn’t concentrate | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 3 | I couldn’t sleep well | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | I felt stressed | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 5 | I felt tired | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6 | I had no appetite | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 7 | I dozed off a lot | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 8 | I felt dazed | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 9 | I had a lot of nightmares | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 10 | I had trouble falling asleep | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 11 | I felt uncomfortable | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12 | I had a lot of dreams | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 13 | I woke up a lot | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 14 | I was too embarrassed to answer | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 15 | My sleep time was shorter | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 16 | My sleep was shallow | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Before Walks (16 June) | After City Walking | After Forest Bathing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 4.56 ± 1.91 | 4.73 ± 1.56 | 4.61 ± 1.31 |

| N | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| Age (Years) | Before (16 June) | After City Walking | After Forest Bathing | Scores of SDS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 36.4 ± 11.3 | 30.25 ± 39.88 | 28.75 ± 38.38 | 28.50 ± 37.80 | 51.64 ± 6.15 |

| N | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| Age (Years) | Before (16 June) | After City Walking | After Forest Bathing | Scores of SDS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 49.2 ± 13.0 | 136.79 ± 38.77 | 132.60 ± 36.97 | 138.43 ± 40.59 * | 46.44 ± 4.39 |

| N | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Age (Years) | After City Walking | After Forest Bathing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 49.2 ± 13.0 | −4.19 ± 11.14 | 1.64 ± 8.48 * |

| N | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Before Walk (16 June) | After City Walk | After Forest Bathing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 8.36 ± 2.65 | 9.29 ± 3.00 * | 10.41 ± 3.87 **,$ |

| N | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| Before (16 June) | After City Walking | After Forest Bathing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 150.19 ± 46.92 | 149.52 ± 50.95 | 156.06 ± 55.07 * |

| N | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| Recruit | Before (16 June) | After City Walking | After Forest Bathing | After 1 Week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 50.29 ± 6.09 | 48.61 ± 8.27 | 43.84 ± 9.64 ** | 40.74 ± 8.72 **,## | 43.20 ± 12.16 ** |

| N | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| AH | CB | DD | FI | TA | VA | F | TMD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 16 June | 2.16 ± 3.62 | 5.55 ± 4.86 | 4.36 ± 5.06 | 7.71 ± 5.56 | 6.26 ± 5.05 | 5.74 ± 4.84 | 8.77 ± 4.32 | 20.42 ± 22.98 |

| City walking | 1.48 ± 3.15 | 4.35 * ± 4.8 | 3.58 ± 5.03 | 9.16 ± 4.67 | 4.16 ** ± 4.81 | 6.74 * ± 5.78 | 9.65 ± 5.40 | 16 ± 23.05 |

| Forest bathing | 0.74 **,$ ± 2.77 | 3.26 **,$ ± 4.53 | 2.87 * ± 4.31 | 4.61 **,$$ ± 4.21 | 2.94 **,$ ± 4.12 | 10.55 **,$$ ± 5.21 | 11.03 **,$$ ± 5.06 | 2.90 **,$$ ± 21.43 |

| Groups | Before (16 June) | After City Walking | After Forest Bathing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 5.29 ± 2.04 | 5.19 ± 2.40 | 3.35 ± 2.29 **,$$ |

| Group 2 | 4.10 ± 2.96 | 3.26 ± 3.51 * | 2.71 ± 3.12 ** |

| Group 3 | 2.55 ± 1.55 | 2.61 ± 1.60 | 1.58 ± 1.29 ** |

| N | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| Forest Bathing (Mean ± SD) | N | City Walking (Mean ± SD) | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor I | Before | 39.15 ± 6.83 | 16 | 38.98 ± 8.8 | 15 |

| After | 45.77 ± 10.84 * | 16 | 43.91 ± 10.88 | 15 | |

| Factor II | Before | 39.03 ± 13.32 | 16 | 40.97 ± 11.8 | 15 |

| After | 42.06 ± 11.77 | 16 | 40.68 ± 11.24 | 15 | |

| Factor III | Before | 41.74 ± 16.21 | 16 | 48.11 ± 13.85 | 15 |

| After | 43.26 ± 12.59 | 16 | 40.27 ± 14.83 * | 15 | |

| Factor IV | Before | 40.2 ± 10.08 | 16 | 42.34 ± 7.77 | 15 |

| After | 45.79 ± 9.3 | 16 | 45.38 ± 11.69 | 15 | |

| Factor V | Before | 41.15 ± 8.92 | 16 | 41.85 ± 15.75 | 15 |

| After | 51.14 ± 12.49 * | 16 | 51.25 ± 10.53 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; Takayama, N.; Katsumata, M.; Takayama, H.; Kimura, Y.; Kumeda, S.; Miura, T.; Ichimiya, T.; Tan, R.; Shimomura, H.; et al. Impacts of Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku) in Female Participants with Depression/Depressive Tendencies. Diseases 2025, 13, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040100

Li Q, Takayama N, Katsumata M, Takayama H, Kimura Y, Kumeda S, Miura T, Ichimiya T, Tan R, Shimomura H, et al. Impacts of Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku) in Female Participants with Depression/Depressive Tendencies. Diseases. 2025; 13(4):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040100

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Qing, Norimasa Takayama, Masao Katsumata, Hiroshi Takayama, Yukako Kimura, Shigeyoshi Kumeda, Takashi Miura, Tetsuya Ichimiya, Ruei Tan, Haruka Shimomura, and et al. 2025. "Impacts of Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku) in Female Participants with Depression/Depressive Tendencies" Diseases 13, no. 4: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040100

APA StyleLi, Q., Takayama, N., Katsumata, M., Takayama, H., Kimura, Y., Kumeda, S., Miura, T., Ichimiya, T., Tan, R., Shimomura, H., Tateno, A., Kitagawa, T., Aoyagi, Y., & Imai, M. (2025). Impacts of Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku) in Female Participants with Depression/Depressive Tendencies. Diseases, 13(4), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13040100