Impact of Becoming a Certified Oncologic Center of Pancreatic Surgery: Evaluation of Single-Center Perioperative Results and Quality of Life Before and After Implementation of a Certified Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Surgical Case Numbers of German Pancreatic Cancer Centers

1.2. Surgical Experience for Pancreatic Cancer Centers

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

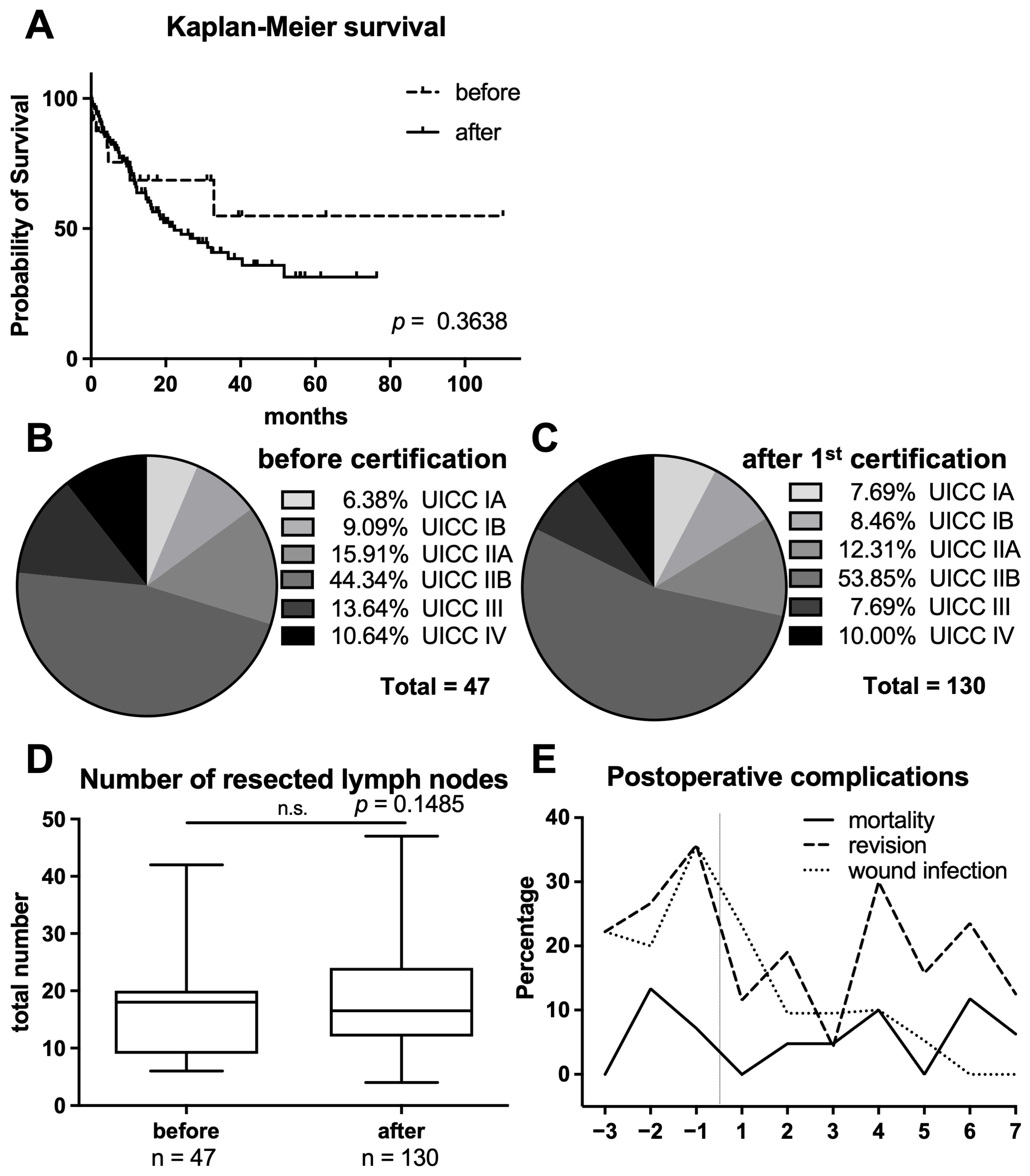

3.1. Comparison of Surgical Performance Characteristics

3.2. Analysis of Perioperative Morbidity and Mortality

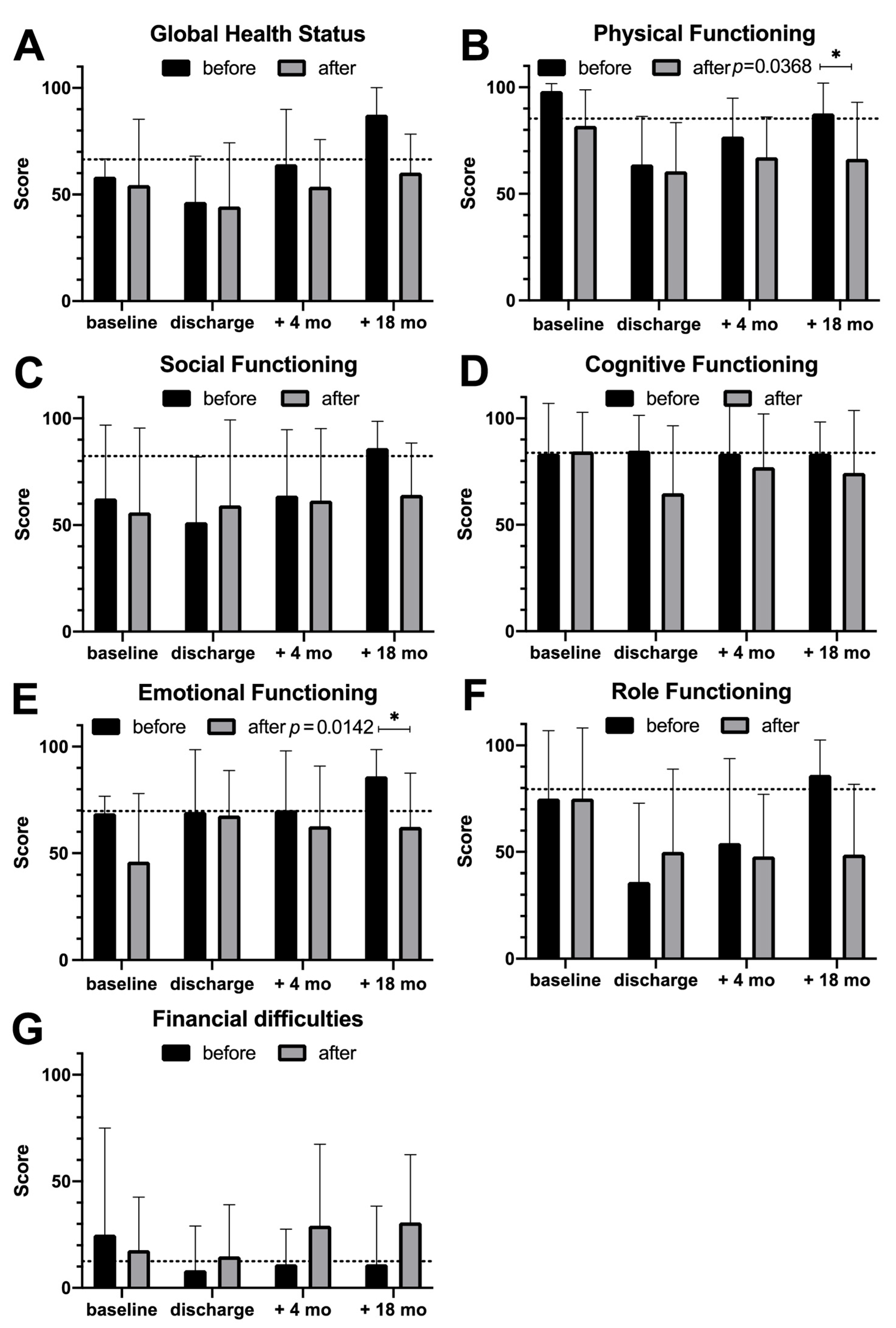

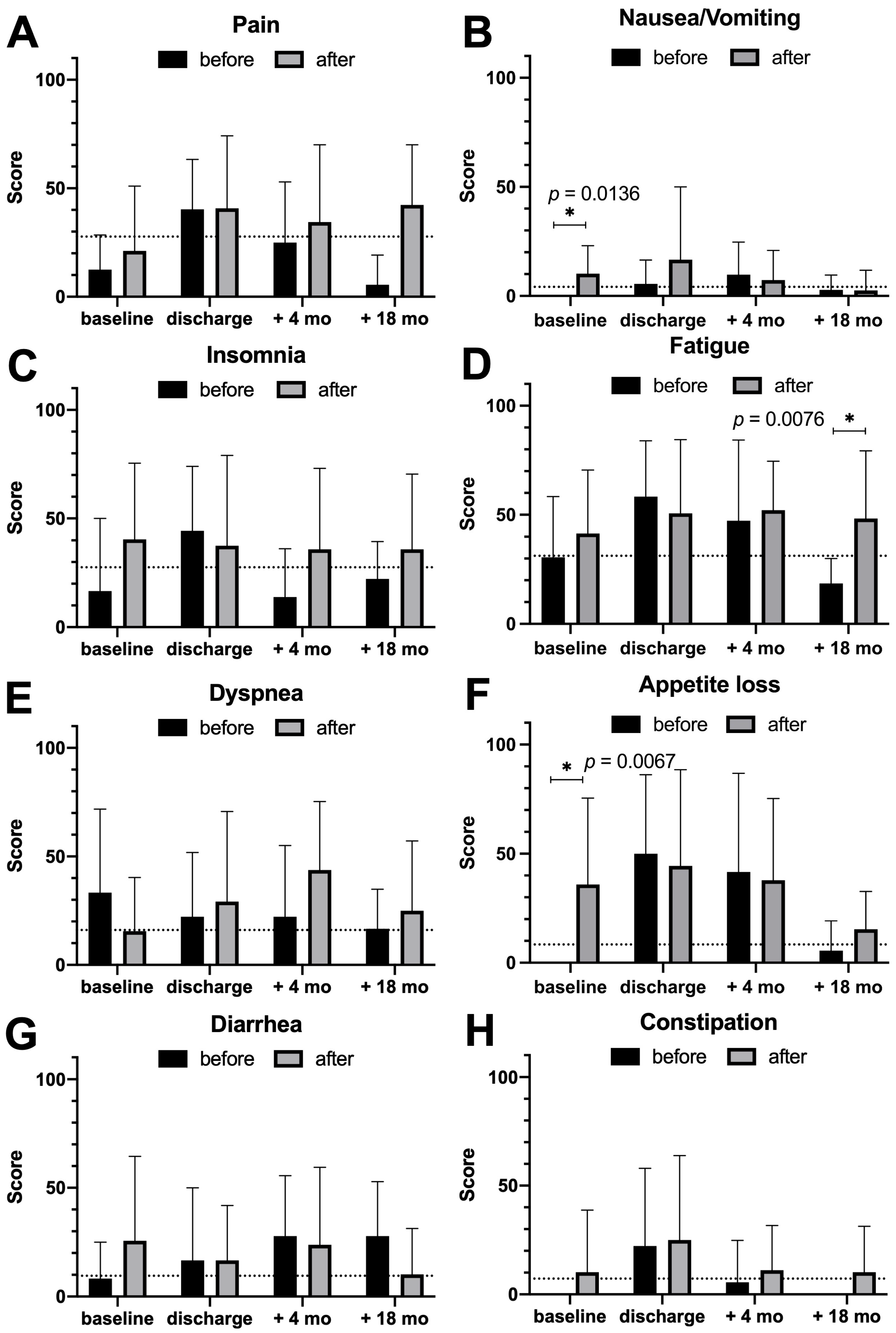

3.3. Quality of Life Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Apart from Missing Surgical Changes, Patient Treatment Improved Significantly

4.2. Comparison of Surgical Performance Characteristics

4.3. Analysis of Perioperative Morbidity and Mortality as Well as Quality of Life Assessment

4.4. Certified Centers Have a Pioneer Role and Other Hospitals Will Follow

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRM | Circumferential resection margin |

| DKG | Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, German Cancer Society |

| PAC | Pancreatic cancer |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| UICC | Union internationale contre le cancer |

| FOLFIRINOX | 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, oxaliplatin |

References

- Vonlanthen, R.; Lodge, P.; Barkun, J.S.; Farges, O.; Rogiers, X.; Soreide, K.; Kehlet, H.; Reynolds, J.V.; Kaser, S.A.; Naredi, P.; et al. Toward a Consensus on Centralization in Surgery. Ann. Surg. 2018, 268, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonski, A.; Izbicki, J.R.; Uzunoglu, F.G. Centralization of Pancreatic Surgery in Europe. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2019, 23, 2081–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.; Drebin, J.A.; Callery, M.P.; Fraker, D.; Kent, T.S.; Gates, J.; Vollmer, C.M., Jr. A contemporary analysis of survival for resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. HPB 2013, 15, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartwig, W.; Werner, J.; Jager, D.; Debus, J.; Buchler, M.W. Improvement of surgical results for pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, e476–e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strobel, O.; Neoptolemos, J.; Jager, D.; Buchler, M.W. Optimizing the outcomes of pancreatic cancer surgery. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, C.; Graeven, U.; von Kalle, C.; Lang, H.; Beckmann, M.W.; Blohmer, J.U.; Burchardt, M.; Ehrenfeld, M.; Fichtner, J.; Grabbe, S.; et al. Shifting cancer care towards Multidisciplinarity: The cancer center certification program of the German cancer society. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, e.V.; Zertifizierungskommission Viszeralonkologische Zentren/Pankreaskarzinomzentren; Mayerle, J.; Reißfelder, C.; Wesselmann, S.; Rückher, J.; Utzig, M.; Barth, C.; Dudu, F. Jahresbericht der Zertifizierten Pankreaskarzinomzentren. Auditjahr 2024/Kennzahlenjahr 2023; Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (DKG): Berlin, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, e.V.; Zertifizierungskommission Viszeralonkologische Zentren/Pankreaskarzinomzentren; Seufferlein, T.; Post, S.; Wesselmann, S.; Rückher, J.; Rommel, M.; Dudu, F.; Ferencz, J. Jahresbericht der Zertifizierten Pankreaskarzinomzentren. Auditjahr 2020/Kennzahlenjahr 2019; Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (DKG): Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gastinger, I.; Meyer, F.; Shardin, A.; Ptok, H.; Lippert, H.; Dralle, H. Investigations on in-hospital mortality in pancreatic surgery: Results of a multicenter observational study. Chirurg 2019, 90, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krautz, C.; Haase, E.; Elshafei, M.; Saeger, H.D.; Distler, M.; Grutzmann, R.; Weber, G.F. The impact of surgical experience and frequency of practice on perioperative outcomes in pancreatic surgery. BMC Surg. 2019, 19, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.; Thomas, A.S.; Rosario, V.L.; Sugahara, K.N.; Schrope, B.A.; Chabot, J.A.; Genkinger, J.M.; Kwon, W.; Kluger, M.D. Long-term quality of life and global health following pancreatic surgery for benign and malignant pathologies. Surgery 2021, 170, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, S.M.; Heerkens, H.D.; Tseng, D.S.J.; Intven, M.; Molenaar, I.Q.; van Santvoort, H.C. Systematic review on the impact of pancreatoduodenectomy on quality of life in patients with pancreatic cancer. HPB 2018, 20, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, A.; Schubert, D.; Katalinic, A. Normative data of the EORTC QLQ-C30 for the German population: A population-based survey. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74149. [Google Scholar]

- Egberts, J.H.; Schniewind, B.; Bestmann, B.; Schafmayer, C.; Egberts, F.; Faendrich, F.; Kuechler, T.; Tepel, J. Impact of the site of anastomosis after oncologic esophagectomy on quality of life--a prospective, longitudinal outcome study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 15, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemanno, G.; Bergamini, C.; Martellucci, J.; Somigli, R.; Prosperi, P.; Bruscino, A.; Sturiale, A.; Valeri, A. Surgical outcome of pancreaticoduodenectomy: High volume center or multidisciplinary management? Minerva Chir. 2016, 71, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Huthmann, D.; Seufferlein, T.; Post, S.; Benz, S.; Stinner, B.; Wesselmann, S. Certified stomach cancer centres as seen by their directors: Results of a questionaire to key personnel. Z. Gastroenterol. 2012, 50, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vollmer, C.M., Jr. The economics of pancreas surgery. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 93, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellner, U.F.; Keck, T. Quality Indicators in Pancreatic Surgery: Lessons Learned from the German DGAV StuDoQ|Pancreas Registry. Visc. Med. 2017, 33, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellner, U.F.; Grutzmann, R.; Keck, T.; Nussler, N.; Witzigmann, H.E.; Buhr, H.J.; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie e. V., Qualitätskommission. Quality indicators for pancreatic surgery: Scientific derivation and clinical relevance. Chirurg 2018, 89, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangl, O.; Sahora, K.; Kornprat, P.; Margreiter, C.; Primavesi, F.; Bareck, E.; Schindl, M.; Langle, F.; Ofner, D.; Mischinger, H.J.; et al. Preparing for prospective clinical trials: A national initiative of an excellence registry for consecutive pancreatic cancer resections. World J. Surg. 2014, 38, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, T.M.; Wellner, U.F.; van Rijssen, L.B.; Stoop, T.F.; Busch, O.R.; Groot Koerkamp, B.; Bausch, D.; Petrova, E.; Besselink, M.G.; Keck, T.; et al. Variation in pancreatoduodenectomy as delivered in two national audits. Br. J. Surg. 2019, 106, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Liu, J.; Ni, Q.; He, J.; Zheng, L.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Determining the optimal number of examined lymph nodes for accurate staging of pancreatic cancer: An analysis using the nodal staging score model. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Jansen, L.; Balavarca, Y.; van der Geest, L.; Lemmens, V.; Groot Koerkamp, B.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Grutzmann, R.; Besselink, M.G.; Schrotz-King, P.; et al. Significance of Examined Lymph Node Number in Accurate Staging and Long-term Survival in Resected Stage I-II Pancreatic Cancer-More is Better? A Large International Population-based Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. 2021, 274, e554–e563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzomati, D.; Perrone, G.; Nappo, G.; Valeri, S.; Amato, M.; Petitti, T.; Muda, A.O.; Coppola, R. Microscopic Residual Tumor After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Is Standardization of Pathological Examination Worthwhile? Pancreas 2016, 45, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeke, C.S.; Knapp, J.; Gladhaug, I.P. Tumour growth is more dispersed in pancreatic head cancers than in rectal cancer: Implications for resection margin assessment. Histopathology 2011, 59, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, D.K.; Johns, A.L.; Merrett, N.D.; Gill, A.J.; Colvin, E.K.; Scarlett, C.J.; Nguyen, N.Q.; Leong, R.W.; Cosman, P.H.; Kelly, M.I.; et al. Margin clearance and outcome in resected pancreatic cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 2855–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, K.; Hirao, T.; Unno, M.; Fujii, T.; Yoshitomi, H.; Suzuki, S.; Satoi, S.; Takahashi, S.; Kainuma, O.; Suzuki, Y. Postoperative infectious complications after pancreatic resection. Br. J. Surg. 2015, 102, 1551–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyaev, O.; Herzog, T.; Chromik, A.M.; Meurer, K.; Uhl, W. Early and late postoperative changes in the quality of life after pancreatic surgery. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2013, 398, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerkens, H.D.; Tseng, D.S.; Lips, I.M.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Vriens, M.R.; Hagendoorn, J.; Meijer, G.J.; Borel Rinkes, I.H.; van Vulpen, M.; Molenaar, I.Q. Health-related quality of life after pancreatic resection for malignancy. Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, I.; Sand, J.; Peromaa, P.; Nordback, I.; Laukkarinen, J. Quality of life in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Pancreatology 2017, 17, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbah, N.; Brown, R.E.; St Hill, C.R.; Bower, M.R.; Ellis, S.F.; Scoggins, C.R.; McMasters, K.M.; Martin, R.C. Impact of post-operative complications on quality of life after pancreatectomy. JOP 2012, 13, 387–393. [Google Scholar]

- Schniewind, B.; Bestmann, B.; Henne-Bruns, D.; Faendrich, F.; Kremer, B.; Kuechler, T. Quality of life after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. Br. J. Surg. 2006, 93, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaiber, U.; Probst, P.; Huttner, F.J.; Bruckner, T.; Strobel, O.; Diener, M.K.; Mihaljevic, A.L.; Buchler, M.W.; Hackert, T. Randomized Trial of Pylorus-Preserving vs. Pylorus-Resecting Pancreatoduodenectomy: Long-Term Morbidity and Quality of Life. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 24, 341–352. [Google Scholar]

- Huttner, F.J.; Fitzmaurice, C.; Schwarzer, G.; Seiler, C.M.; Antes, G.; Buchler, M.W.; Diener, M.K. Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (pp Whipple) versus pancreaticoduodenectomy (classic Whipple) for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, CD006053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epelboym, I.; Winner, M.; DiNorcia, J.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, J.A.; Schrope, B.; Chabot, J.A.; Allendorf, J.D. Quality of life in patients after total pancreatectomy is comparable with quality of life in patients who undergo a partial pancreatic resection. J. Surg. Res. 2014, 187, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettle, H.; Post, S.; Neuhaus, P.; Gellert, K.; Langrehr, J.; Ridwelski, K.; Schramm, H.; Fahlke, J.; Zuelke, C.; Burkart, C.; et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy With Gemcitabine vs. Observation in Patients Undergoing Curative-Intent Resection of Pancreatic Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2007, 297, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neoptolemos, J.P.; Stocken, D.D.; Tudur Smith, C.; Bassi, C.; Ghaneh, P.; Owen, E.; Moore, M.; Padbury, R.; Doi, R.; Smith, D.; et al. Adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid vs. observation for pancreatic cancer: Composite data from the ESPAC-1 and -3(v1) trials. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, T.; Hammel, P.; Hebbar, M.; Ben Abdelghani, M.; Wei, A.C.; Raoul, J.L.; Choné, L.; Francois, E.; Artru, P.; Biagi, J.J.; et al. FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2395–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.E.; Lacchetti, C.; Alici, Y.; Barton, D.L.; Bruner, D.; Canin, B.E.; Escalante, C.P.; Ganz, P.A.; Garland, S.N.; Gupta, S.; et al. Management of Fatigue in Adult Survivors of Cancer: ASCO–Society for Integrative Oncology Guideline Update. JCO. 2024, 42, 2456–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellner, U.F.; Klinger, C.; Lehmann, K.; Buhr, H.; Neugebauer, E.; Keck, T. The pancreatic surgery registry (StuDoQ|Pancreas) of the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV)—Presentation and systematic quality evaluation. Trials 2017, 18, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, N.R.; Dalton, M.; Cutler, D.M.; Birkmeyer, J.D.; Chandra, A. Surgeon specialization and operative mortality in United States: Retrospective analysis. BMJ 2016, 354, i3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaiber, U.; Leonhardt, C.S.; Strobel, O.; Tjaden, C.; Hackert, T.; Neoptolemos, J.P. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2018, 403, 917–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackert, T.; Sachsenmaier, M.; Hinz, U.; Schneider, L.; Michalski, C.W.; Springfeld, C.; Strobel, O.; Jager, D.; Ulrich, A.; Buchler, M.W. Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Neoadjuvant Therapy With Folfirinox Results in Resectability in 60% of the Patients. Ann. Surg. 2016, 264, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorn, S.; Demir, I.E.; Reyes, C.M.; Saricaoglu, C.; Samm, N.; Schirren, R.; Tieftrunk, E.; Hartmann, D.; Friess, H.; Ceyhan, G.O. The impact of neoadjuvant therapy on the histopathological features of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 55, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, F.; Coinu, A.; Borgonovo, K.; Cabiddu, M.; Ghilardi, M.; Lonati, V.; Aitini, E.; Barni, S.; Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dei Carcinomi dell’Apparato Digerente. FOLFIRINOX-based neoadjuvant therapy in borderline resectable or unresectable pancreatic cancer: A meta-analytical review of published studies. Pancreas 2015, 44, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, V.; Li, J.; Lin, C. Neoadjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer: Systematic Review of Postoperative Morbidity, Mortality, and Complications. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 39, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; Song, L.; Zhao, R.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Z.Q. Serum exosomal hsa-let-7f-5p: A potential diagnostic biomarker for metastatic pancreatic cancer detection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 109500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| A | Histopathology | UICC Scoring | R-Status | Hospitalization | ||||||||||||

| year | n | ♀ | age ± SD | AC | NE | CA | n/a | 1A | 1B | 2A | 2B | 3 | 4 | 0/1/2/x | duration | † |

| −3 | 18 | 8 | 62.6 ± 9.0 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 15/1/1/1 | 27.5 ± 21.3 | 0 |

| −2 | 15 | 7 | 64.5 ± 13.7 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 12/2/1/0 | 25.9 ± 17.8 | 1 |

| −1 | 14 | 6 | 67.3 ± 10.9 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 10/1/0/3 | 28.9 ± 22.3 | 1 |

| total | 47 | 21 | 64.6 ± 11.0 | 39 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 22 | 6 | 5 | 37/4/2/4 | 27.4 ± 20.3 | 2 |

| B | Histopathology | UICC Scoring | R-Status | Hospitalization | ||||||||||||

| year | n | ♀ | age ± SD | AC | NE | CA | n/a | 1A | 1B | 2A | 2B | 3 | 4 | 0/1/2/x | duration | † |

| 1 | 26 | 14 | 66.8 ± 8.3 | 23 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 22/3/1/0 | 27.0 ± 16.8 | 0 |

| 2 | 21 | 11 | 67.7 ± 8.0 | 16 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 13 | 0 | 2 | 16/5/0/0 | 20.9 ± 10.8 | 1 |

| 3 | 21 | 11 | 64.4 ± 12.8 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 15/4/2/0 | 22.2 ± 11.6 | 1 |

| 4 | 10 | 4 | 70.4 ± 7.0 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 9/1/0/0 | 29.8 ± 19.3 | 1 |

| 5 | 19 | 9 | 67.8 ± 10.6 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 14/5/0/0 | 23.9 ± 15.6 | 0 |

| 6 | 17 | 11 | 69.4 ± 10.3 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 15/2/0/0 | 22.1 ± 9.7 | 2 |

| 7 | 16 | 6 | 59.9 ± 10.5 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 11/5/0/0 | 23.7 ± 13.2 | 1 |

| total | 130 | 67 | 63.7 ± 15.2 | 105 | 19 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 16 | 70 | 10 | 13 | 102/25/3/0 | 23.3 ± 13.6 | 6 |

| Years Before Certification | Years After 1st Certification | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −3 | −2 | −1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Total number of patients [n] | 25 | 19 | 19 | 29 | 31 | 30 | 15 | 24 | 20 | 23 |

| Completed resection [n (%)] | 18 (72.0) | 15 (78.9) | 14 (73.7) | 26 (89.7) | 21 (67.7) | 21 (70.0) | 10 (66.6) | 19 (79.2) | 17 (85.0) | 16 (69.6) |

| Exploration only [n (%)] | 7 (28.0) | 4 (21.1) | 5 (26.3) | 3 (10.3) | 10 (32.3) | 9 (30.0) | 5 (33.3) | 5 (20.8) | 3 (15.0) | 7 (30.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gundlach, J.-P.; Fedders, T.; Heckl, S.M.; Becker, T.; Pochhammer, J. Impact of Becoming a Certified Oncologic Center of Pancreatic Surgery: Evaluation of Single-Center Perioperative Results and Quality of Life Before and After Implementation of a Certified Center. Diseases 2025, 13, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13110353

Gundlach J-P, Fedders T, Heckl SM, Becker T, Pochhammer J. Impact of Becoming a Certified Oncologic Center of Pancreatic Surgery: Evaluation of Single-Center Perioperative Results and Quality of Life Before and After Implementation of a Certified Center. Diseases. 2025; 13(11):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13110353

Chicago/Turabian StyleGundlach, Jan-Paul, Thorben Fedders, Steffen Markus Heckl, Thomas Becker, and Julius Pochhammer. 2025. "Impact of Becoming a Certified Oncologic Center of Pancreatic Surgery: Evaluation of Single-Center Perioperative Results and Quality of Life Before and After Implementation of a Certified Center" Diseases 13, no. 11: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13110353

APA StyleGundlach, J.-P., Fedders, T., Heckl, S. M., Becker, T., & Pochhammer, J. (2025). Impact of Becoming a Certified Oncologic Center of Pancreatic Surgery: Evaluation of Single-Center Perioperative Results and Quality of Life Before and After Implementation of a Certified Center. Diseases, 13(11), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13110353