Right Ventricular Strain and Left Ventricular Strain Using Speckle Tracking Echocardiography—Independent Prognostic Associations in COPD Alongside NT-proBNP

Abstract

1. Introduction

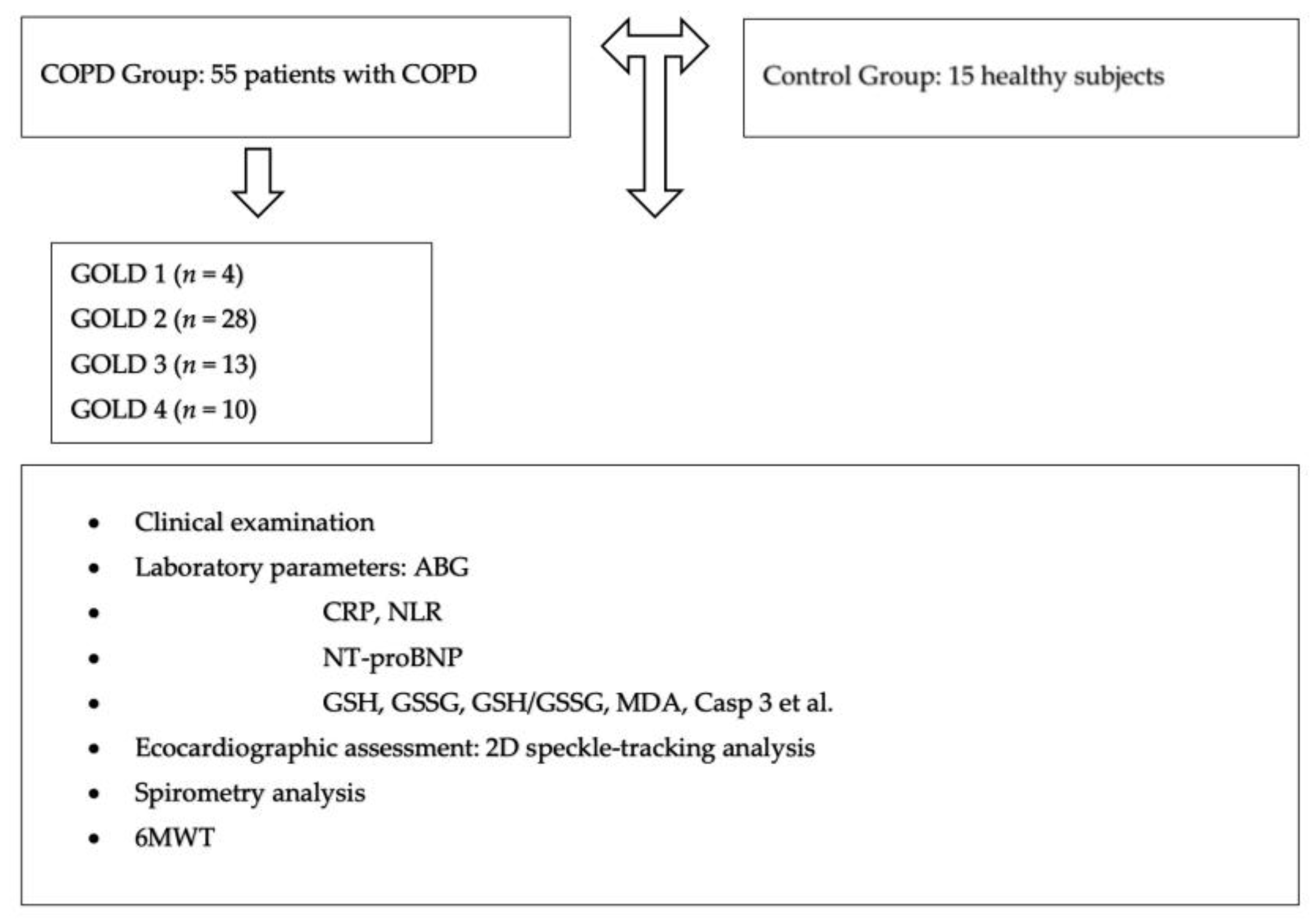

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Characteristics of the Groups

2.2. Laboratory Parameter Analysis

2.3. Echocardiographic Assessment

2.4. Spirometry

2.5. Statistical Analysis

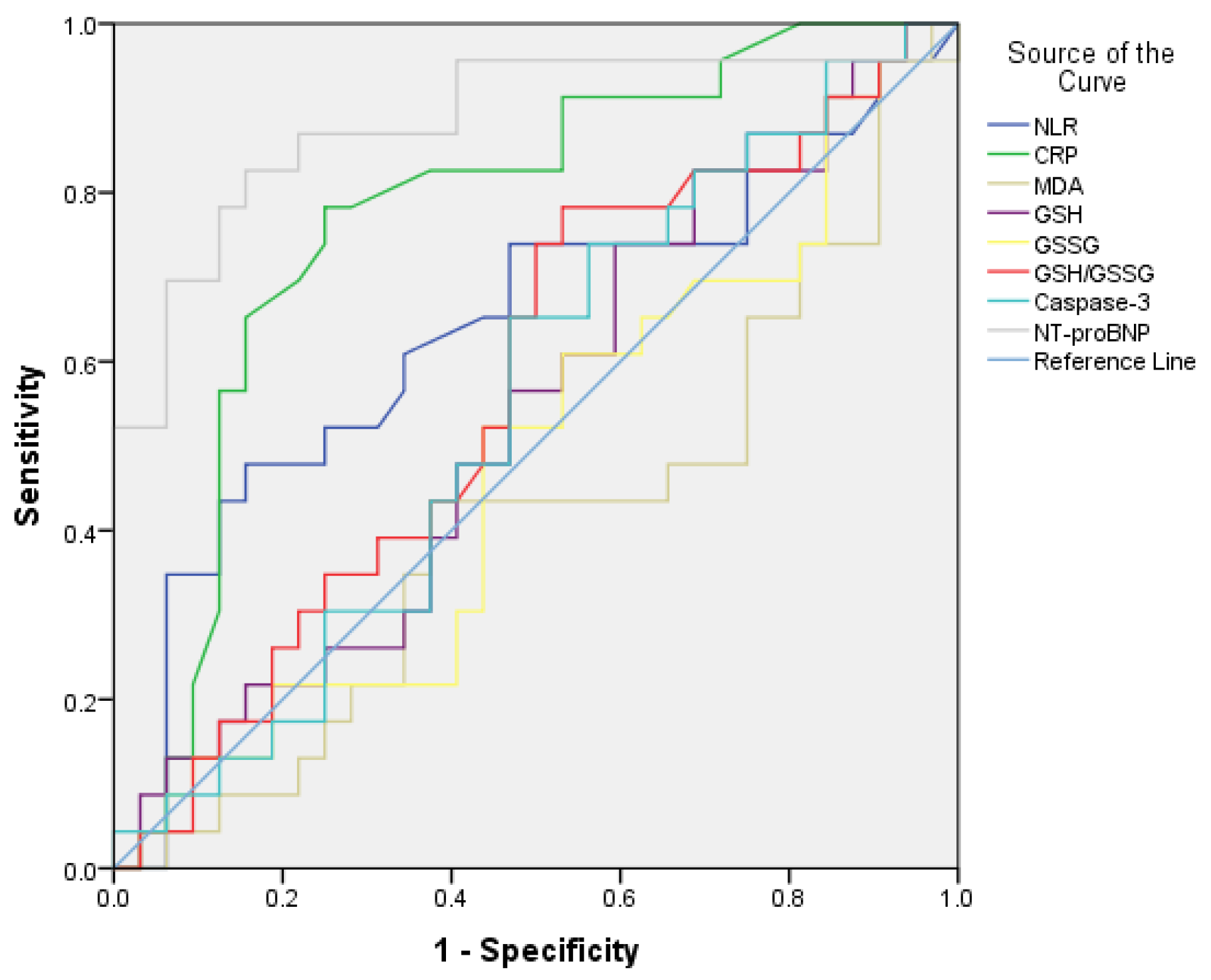

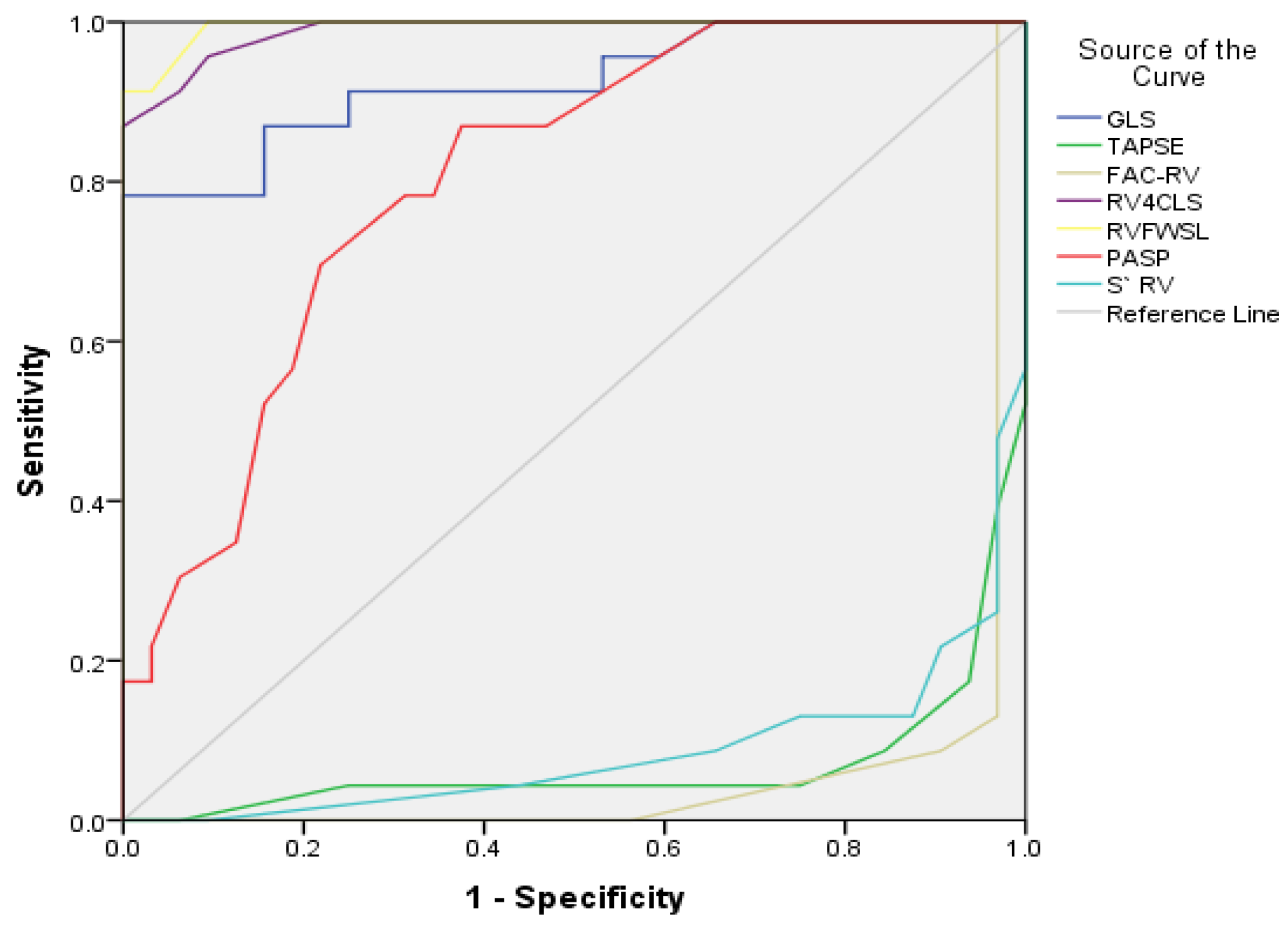

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sin, D.D.; Doiron, D.; Agusti, A.; Anzueto, A.; Barnes, P.J.; Celli, B.R.; Criner, G.J.; Halpin, D.; Han, M.K.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Air Pollution and COPD: GOLD 2023 Committee Report. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2202469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, I.A.; Jenkins, C.R.; Salvi, S.S. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Never-Smokers: Risk Factors, Pathogenesis, and Implications for Prevention and Treatment. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesan, P. GOLD COPD Report: 2025 Update. Lancet Respir. Med. 2025, 13, e7–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppel, G.L.; Carlin, B.W.; Hart, M.; Doherty, D.E. Office Spirometry in Primary Care for the Diagnosis and Management of COPD: National Lung Health Education Program Update. Respir. Care 2018, 63, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlyarov, S. Involvement of the Innate Immune System in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Maloney, J.; Grove, L.; Wrona, C.; Berenson, C.S. Airway Inflammation and Bronchial Bacterial Colonization in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 173, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogea, S.; Tudorache, E.; Fildan, A.P.; Fira-Mladinescu, O.; Marc, M.; Oancea, C. Risk Factors of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations. Clin. Respir. J. 2020, 14, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearn, C.P.; Gallo, M.C.; Murphy, T.F. Insights on Persistent Airway Infection by Non-Typeable Haemophilus Influenzae in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Pathog. Dis. 2017, 75, ftx042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razia, D.E.M.; Gao, C.; Wang, C.; An, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, L.; Lin, H. Targeting Non-Eosinophilic Immunological Pathways in COPD and AECOPD: Current Insights and Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2025, 20, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promsrisuk, T.; Boonla, O.; Kongsui, R.; Sriraksa, N.; Thongrong, S.; Srithawong, A. Oxidative Stress Associated with Impaired Autonomic Control and Severity of Lung Function in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2023, 19, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentaher, A.; Glehen, O.; Degobert, G. Pulmonary Emphysema: Current Understanding of Disease Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalpando-Rodriguez, G.E.; Gibson, S.B. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Regulates Different Types of Cell Death by Acting as a Rheostat. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 9912436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demedts, I.K.; Demoor, T.; Bracke, K.R.; Joos, G.F.; Brusselle, G.G. Role of Apoptosis in the Pathogenesis of COPD and Pulmonary Emphysema. Respir. Res. 2006, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Ping, P.; Wang, F.; Luo, L. Synthesis, Secretion, Function, Metabolism and Application of Natriuretic Peptides in Heart Failure. J. Biol. Eng. 2018, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Lei, T.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Feng, Z.; Shuai, T.; Guo, H.; Liu, J. NT-proBNP in Different Patient Groups of COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023, 18, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, M.; Morand, P.C.; Levillain, P.; Lemonnier, A. Improved Fluorometric Determination of Malonaldehyde. Clin. Chem. 1991, 37, 1273–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.-L. Measurement of Protein Thiol Groups and Glutathione in Plasma. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 233, pp. 380–385. ISBN 978-0-12-182134-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vats, P.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, S.N.; Singh, S.B. Glutathione Metabolism Under High-Altitude Stress and Effect of Antioxidant Supplementation. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2008, 79, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, V.; Cardim, N.; Cosyns, B.; Donal, E.; Flachskampf, F.; Galderisi, M.; Gerber, B.; Gimelli, A.; Haugaa, K.H.; Kaufmann, P.A.; et al. Criteria for Recommendation, Expert Consensus, and Appropriateness Criteria Papers: Update from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging Scientific Documents Committee. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 19, 835–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraru, D.; Badano, L.P. Shedding New Light on the Fascinating Right Heart. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23, 863–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraru, D.; Haugaa, K.; Donal, E.; Stankovic, I.; Voigt, J.U.; Petersen, S.E.; Popescu, B.A.; Marwick, T. Right Ventricular Longitudinal Strain in the Clinical Routine: A State-of-the-Art Review. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.N.N.; Luong, T.V.; Tran, T.T. Evaluating Left Atrial Function Changes by Speckle Tracking Echocardiography in Type 2 Diabetes Patients in Central Vietnam: A Cross-Sectional Comparative Study. Egypt. Heart J. 2024, 76, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, N.; Bismee, N.N.; Abbas, M.T.; Scalia, I.G.; Pereyra, M.; Baba Ali, N.; Attaripour Esfahani, S.; Awad, K.; Farina, J.M.; Ayoub, C.; et al. Left Atrial Strain: State of the Art and Clinical Implications. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. Corrigendum to: 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure: Developed by the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the Special Contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galderisi, M.; Cosyns, B.; Edvardsen, T.; Cardim, N.; Delgado, V.; Di Salvo, G.; Donal, E.; Sade, L.E.; Ernande, L.; Garbi, M.; et al. Standardization of Adult Transthoracic Echocardiography Reporting in Agreement with Recent Chamber Quantification, Diastolic Function, and Heart Valve Disease Recommendations: An Expert Consensus Document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 18, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govind, S.C. Right Ventricular Strain: Clinical Application. J. Indian Acad. Echocardiogr. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 7, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Zeng, W.; Wang, H.; Ren, S. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) and Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (MLR) as Biomarkers in Diagnosis Evaluation of Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Retrospective, Observational Study. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2024, 19, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaypak, M.K.; Annakkaya, A.N.; Davran, F.; Yıldız Gülhan, P.; Yüregir, U. The Effect of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Therapy on Serum Caspase-3 Level in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA). Sleep Breath 2024, 28, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Tripathi, Y.; Yadav, B.; Garg, R. Echocardiographic study of right ventricle changes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients of different severity. Int. J. Med. Biomed. Stud. 2019, 3, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suma, K.R.K.R.; Srinath, S.S.; Praveen, P. Electrocardiographic and echocardiographic changes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) of different grades of severity. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2015, 4, 5093–5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, N.M.; Khosla, A.; Virani, S.A.; McMurray, J.J.V.; FitzGerald, J.M. B-Type Natriuretic Peptides in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavasini, R.; Tavazzi, G.; Biscaglia, S.; Guerra, F.; Pecoraro, A.; Zaraket, F.; Gallo, F.; Spitaleri, G.; Contoli, M.; Ferrari, R.; et al. Amino Terminal pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide Predicts All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chronic Respir. Dis. 2017, 14, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preiss, H.; Mayer, L.; Furian, M.; Schneider, S.R.; Müller, J.; Saxer, S.; Mademilov, M.; Titz, A.; Shehab, A.; Reimann, L.; et al. Right Ventricular Strain Impairment Due to Hypoxia in Patients with COPD: A Post Hoc Analysis of Two Randomised Controlled Trials. Open Heart 2025, 12, e002837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, S.; Singh, S.; Fotedar, M.; Chaudhari, S.; Sethi, K. Echocardiographic Evaluation of Right Ventricular Function and Its Role in the Prognosis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Echogr. 2020, 30, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulen, S.T.; Eryilmaz, U.; Yilmaz, M.; Karadag, F. Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Relation with Systemic Inflammation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.N.N.; Luong, T.V.; Nguyen, N.T.Y.; Tran, H.K.; Tran, H.T.N.; Vu, H.M.; Van Ho, T.; Vo, N.T.M.; Tran, T.T.; Do, T.S.; et al. Assessment of the Right Ventricular Strain, Left Ventricular Strain and Left Atrial Strain Using Speckle Tracking Echocardiography in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2025, 12, e002706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz Elçioğlu, B.; Kamat, S.; Yurdakul, S.; Şahin, Ş.T.; Sarper, A.; Yıldız, P.; Aytekin, S. Assessment of Subclinical Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction and Structural Changes in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Intern. Med. J. 2022, 52, 1791–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.Q. Association between Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Systemic Inflammation: A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis. Thorax 2004, 59, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaltekin, İ.; Gökçen, E.; Albayrak, L.; Atik, D.; Savrun, A.; Kuşdoğan, M.; Kaya, H.; Vural, S.; Savrun, Ş.T. Inflammatory Markers and Blood Gas Analysis in Determining the Severity of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Eurasian J. Crit. Care 2020, 2, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, K.C.; De, S.; Mishra, P.K. Role of Proteases in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Anes, A.; Fetoui, H.; Bchir, S.; Ben Nasr, H.; Chahdoura, H.; Chabchoub, E.; Yacoub, S.; Garrouch, A.; Benzarti, M.; Tabka, Z.; et al. Increased Oxidative Stress and Altered Levels of Nitric Oxide and Peroxynitrite in Tunisian Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Correlation with Disease Severity and Airflow Obstruction. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2014, 161, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, Z.H.; El Hakim, M.A.E.A.; Mohamed, N.R. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Non-Smokers: Role of Oxidative Stress. Egypt. J. Bronchol. 2021, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.; Kalita, J.; Weldon, S.; Taggart, C.C. Proteases and Their Inhibitors in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schermer, T.R. Validity of Spirometric Testing in a General Practice Population of Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Thorax 2003, 58, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Stockley, R.; Anzueto, A.; Agusti, A.; Bourbeau, J.; Celli, B.R.; Criner, G.J.; Han, M.K.; Martinez, F.J.; Montes De Oca, M.; et al. GOLD Science Committee Recommendations for the Use of Pre- and Post-Bronchodilator Spirometry for the Diagnosis of COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2025, 65, 2401603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, M.; Sisó-Almirall, A.; Ocaña, A.; Agustí, A.; Faner, R.; Borras-Santos, A.; González-de Paz, L. Prevalence, Diagnostic Accuracy, and Healthcare Utilization Patterns in Patients with COPD in Primary Healthcare: A Population-Based Study. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2025, 35, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, A.; Tsuge, M.; Miyahara, N.; Tsukahara, H. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidative Defense in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Ahmad, M.K.; Nischal, A.; Singh, S.K.; Dixit, R.K. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Status in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Scand. J. Immunol. 2017, 85, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detcheverry, F.; Senthil, S.; Narayanan, S.; Badhwar, A. Changes in levels of the antioxidant glutathione in brain and blood across the age span of healthy adults: A systematic review. NeuroImage Clin. 2023, 40, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.-R.; Jang, J.; Park, S.-M.; Ryu, S.M.; Cho, S.-J.; Yang, S.-R. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Respiratory Response: Insights into Cellular Processes and Biomarkers. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, M.L.; Novelli, F.; Costa, F.; Malagrinò, L.; Melosini, L.; Bacci, E.; Cianchetti, S.; Dente, F.L.; Di Franco, A.; Vagaggini, B.; et al. Malondialdehyde in Exhaled Breath Condensate as a Marker of Oxidative Stress in Different Pulmonary Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2011, 2011, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingale, P.; Rai, P.; Salunkhe, V.; Awad, N.T. Is Malondialdehyde(MDA) Used as a Oxidative Stress Marker in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease(COPD) & Cigarette Smokers. JK Sci. J. Med. Educ. Res. 2022, 24, 239–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Moussa, S.; Sfaxi, I.; Tabka, Z.; Ben Saad, H.; Rouatbi, S. Oxidative stress and lung function profiles of male smokers free from COPD compared to those with COPD: A case-control study. Libyan J. Med. 2014, 9, 23873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, K.; Mercer, B.A.; Schulman, L.L.; Sonett, J.R.; D’ARmiento, J.M. Correlation of lung surface area to apoptosis and proliferation in human emphysema. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 25, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables/Normal Values | COPD Group (n = 55) | Control Group (n = 15) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (%)/>50% | 55 ± 4.3 | 57 ± 3.6 | 0.43 |

| GLS LV avg (%)/>18% | −19.9 ± 1.93 | −20.9 ± 0.9 | <0.001 * |

| S’ RV (cm/s)/>10 cm/s | 12.0 ± 2.7 | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 0.03 * |

| TAPSE (mm)/>16 mm | 18.8 ± 3.1 | 23.3 ± 1.5 | <0.001 * |

| FAC-RV (%)/>35% | 32.1 ± 9.8 | 36.7 ± 2.1 | <0.001 * |

| RVFWSL%/–26.7% ± 5.2 | −18.3 ± 1.7 | −23.0 ± 1.2 | <0.001 * |

| RV4CSL%/–21.7% ± 3.4% | −15.9 ± 1.8 | −23.0 ± 1.2 | <0.001 * |

| RA aria (cm2)/>18 cm2 | 17.3 ± 2.1 | 15.4 ± 2.4 | 0.06 |

| RA volume (mL/m2)/>31 mL/m2 | 29.1 ± 5.4 | 27.2 ± 3.4 | 0.07 |

| LA volume (mL/m2)/<34 mL/m2 | 33.9 ± 4.9 | 32.4 ± 1.5 | 0.09 |

| LASr (%)/35.9% ± 10.6% | 31.4 ± 6.9 | 37.9 ± 5.4 | 0.08 |

| LAScd (%)/−21.9% ± 9.3% | −21.1 ± 5.7 | −24.1 ± 6.8 | 0.06 |

| LASct (%)−13.9% ± 3.6% | −16.8 ± 3.2 | −17.1 ± 1.8 | 0.09 |

| PASP (mmHg)/15–30 mmHg | 34.8 ± 5.7 | 22.3 ± 4.3 | <0.001 * |

| Variables/Normal Values | COPD GOLD 1 | COPD GOLD 2 | COPD GOLD 3 | COPD GOLD 4 | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (%)/>50% | 56.7 ± 2.5 | 56.6 ± 2.7 | 53 ± 4.9 | 51.5 ± 4.5 | <0.06 |

| GLS LV avg (%)/>18% | −21.3 ± 0.8 | −20.1 ± 1 | −17.9 ± 1.4 | −16.6 ± 1.2 | <0.001 * |

| S’ RV (cm/s)/>10 cm/s | 15.2 ± 0.5 | 13.4 ± 1.8 | 9.8 ± 1.4 | 9.4 ± 2.5 | <0.001 * |

| TAPSE (mm)/>16 mm | 21.2 ± 0.9 | 20.7 ± 2.1 | 17.3 ± 2 | 14.5 ± 0.9 | <0.001 * |

| FAC-RV (%)/>35% | 43.7 ± 2.2 | 37.1 ± 7.2 | 29.3 ± 4.3 | 17.3 ± 2 | <0.001 * |

| RVFWSL%/–26.7% ± 5.2 | −21 ± 0.3 | −19.3 ± 0.4 | −17.5 ± 0.9 | −15.4 ± 0.7 | <0.001 * |

| RV4CSL%/–21.7% ± 3.4% | −18.7 ± 0.4 | −17 ± 0.4 | −15.2 ± 0.9 | −13 ± 0.7 | <0.001 * |

| RA aria (cm2)/>18 cm2 | 15.5 ± 1.2 | 17.5 ± 2.1 | 17.3 ± 1.8 | 17.6 ± 2.3 | 0.31 |

| RA volume (mL/m2)/>31 mL/m2 | 24.7 ± 1.7 | 29 ± 4.9 | 30.3 ± 6.5 | 29.5 ± 5.9 | 0.37 |

| LA volume (mL/m2)/<34 mL/m2 | 31.2 ± 2 | 34.1 ± 4.4 | 34.1 ± 6.5 | 34.1 ± 5 | 0.75 |

| LASr (%)/35.9% ± 10.6% | 31 ± 6.7 | 30.2 ± 5.2 | 28 ± 6.6 | 28.7 ± 4.5 | 0.07 |

| LAScd (%)/−21.9% ± 9.3% | −22.2 ± 2.8 | −22.4 ± 4.5 | −21 ± 6.6 | −19.8 ± 6.4 | 0.06 |

| LASct (%)−13.9% ± 3.6% | −17.7 ± 1.8 | −17.3 ± 3.3 | −15.3 ± 2.1 | −16.2 ± 3.7 | 0.08 |

| PASP (mmHg)/15–30 mmHg | 27.7 ± 2 | 33 ± 4.9 | 35.4 ± 4.3 | 42 ± 3.5 | <0.001 * |

| Variables/Normal Values | COPD Group (n = 55) | Control Group (n = 15) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLR (%)/0.78–3.53% | 4.46 ± 3.1 | 2.62 ± 0.5 | 0.030 * |

| CRP (mg/L)/0–5 mg/L | 22.1 ± 24.9 | 3 ± 0.7 | 0.004 * |

| MDA (nmol/mL)/0.5–40 nmol/mL | 2952.4 ± 948.3 | 1442.0 ± 959.5 | 0.001 * |

| GSH (nmol/mL)/0.36–30 nmol/mL | 6.9 ± 2.0 | 8.6 ± 2.4 | 0.008 * |

| GSSG (nmol/mL)/0.32–15 nmol/mL | 1.2 ± 0.50 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.004 * |

| GSH/GSSG | 5.9 ± 2.7 | 14.6 ± 8.65 | 0.001 * |

| Casp 3 (pg/mL)/78.13–5000 pg/mL | 240.8 ± 119.2 | 170.1 ± 75.0 | 0.03 * |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL)/<300 pg/mL | 480.0 ± 471.6 | 78.3 ± 17.9 | 0.002 * |

| Variables/Normal Values | COPD GOLD 1 | COPD GOLD 2 | COPD GOLD 3 | COPD GOLD 4 | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory | |||||

| NLR (%)/0.78–3.53% | 2.1 ± 2 | 4.1 ± 3 | 4.3 ± 2.8 | 6.6 ± 3.4 | 0.05 * |

| CRP (mg/L)/0–5 mg/L | 13.7 ± 20 | 21.1 ± 16 | 26.3 ± 24.9 | 45.2 ± 27.2 | 0.005 * |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL)/<300 pg/mL | 148.5 ± 39.5 | 301.2 ± 111.3 | 598.6 ± 685.8 | 958.9 ± 496.2 | <0.001 * |

| Spirometry | |||||

| FEV 1%/>80% [3] | 85 ± 3.3 | 65.7 ± 8.5 | 45.2 ± 3.4 | 27 ± 7.3 | <0.001 * |

| FVC (L)/3.2–4.5 L [3] | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | <0.001 * |

| Number of Patients | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPD GOLD 1 | 4 | 109.00 | 196.00 | 148.50 | 39.53 |

| COPD GOLD 2 | 28 | 117.00 | 580.00 | 301.29 | 111.35 |

| COPD GOLD 3 | 13 | 103.00 | 2830.00 | 598.69 | 685.89 |

| COPD GOLD 4 | 10 | 632.00 | 2300.00 | 958.90 | 496.29 |

| Variables | 1 Exacerbation/Year | 2 Exacerbations/Year | 3 Exacerbations/Year | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory parameter values | ||||

| NLR (%)/0.78–3.53% | 3.2 ± 2.1 | 4.1 ± 2.8 | 6.4 ± 3.7 | 0.006 * |

| CRP (mg/L)/0–5 mg/L | 16.6 ± 21.1 | 29.2 ± 3.3 | 35.9 ± 1.8 | 0.007 * |

| Casp 3 (pg/mL)/78.13–5000 pg/mL | 180.4.6 ± 37.6 | 279.6 ± 142.1 | 276.3 ± 134.5 | 0.01 * |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL)/<300 pg/mL | 332.1 ± 183.6 | 313.8 ± 148.2 | 861 ± 715.8 | <0.001 * |

| Spirometry values | ||||

| FEV 1%/>80% [3] | 63.3 ± 19.1 | 60.2 ± 10.3 | 38.8 ± 14.6 | <0.001 * |

| FVC (L)/3.2–4.5 L [3] | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | <0.001 * |

| Echocardiography parameter values | ||||

| LVEF (%)/>50% | 56.8 ± 2.8 | 55.5 ± 3.5 | 52 ± 5.2 | 0.05 |

| GLS LV avg (%)/>18% | −19.9.3 ± 1.6 | −19.5 ± 1.4 | −17.4 ± 1.8 | <0.001 * |

| S’ RV (cm/s)/>10 cm/sec | 12.3 ± 2.5 | 13.1 ± 2.1 | 10.2 ± 2.8 | 0.005 * |

| TAPSE (mm)/>16 mm | 19.3 ± 2.6 | 20.2 ± 2.5 | 16.8 ± 3.5 | 0.004 * |

| FAC-RV (%)/>35% | 34.4 ± 10 | 36.7 ± 5.3 | 24 ± 8.7 | <0.001 * |

| RVFWSL %/–26.7% ± 5.2 | −19.2 ± 1.2 | −18.8 ± 1.1 | −16.6 ± 1.8 | <0.001 * |

| RV4CSL %/–21.7% ± 3.4% | −16.8 ± 1.3 | −16.5 ± 1 | −14.2 ± 1.8 | <0.001 * |

| PASP (mmHg)/15–30 mmHg | 33.6 ± 5.3 | 32.6 ± 4.7 | 38.8 ± 5.6 | <0.001 * |

| Variables | GSH | GSSG | GSH/GSSG | Casp 3 | NT-proBNP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking index (pack/year) | −0.07; 0.56 | 0.16; 0.21 | −0.27; 0.03 * | 0.15; 0.26 | 0.23; 0.51 |

| Age, years | −0.27; 0.05 * | 0.2; 0.13 | −0.37; 0.005 * | 0.32; 0.01 * | 0.17; 0.19 |

| FEV1 (%) | −0.08; 0.55 | −0.04; 0.74 | −0.10; 0.42 | −0.08; 0.54 | −0.68; 0.001 * |

| FVC (L) | 0.27; 0.05 * | 0.08; 0.53 | 0.27; 0.04 * | −0.02; 0.84 | −0.65; 0.001 * |

| LV GLS (%) | 0.11; 0.39 | −0.06; 0.63 | 0.24; 0.06 | 0.13; 0.32 | −0.54; 0.001 * |

| S’ RV (cm/s) | −0.02; 0.86 | 0.01; 0.91 | −0.08; 0.55 | −0.08; 0.54 | −0.47; 0.001 * |

| TAPSE (mm) | −0.15; 0.24 | −0.10; 0.44 | −0.07; 0.59 | −0.05; 0.71 | −0.53; 0.001 * |

| FAC-RV (%) | −0.01; 0.92 | −0.02; 0.83 | −0.13; 0.34 | −0.21; 0.11 | −0.75; 0.001 * |

| RVFWSL % | 0.19; 0.15 | 0.01; 0.90 | 0.22; 0.09 | 0.15; 0.27 | −0.66; 0.001 * |

| RV4CSL % | 0.22; 0.09 | 0.01; 0.97 | 0.26; 0.05 | 0.13; 0.3 | −0.66; 0.001 * |

| PASP (mmHg) | −0.03; 0.82 | −0.19; 0.15 | 0.16; 0.24 | 0.02; 0.84 | 0.65; 0.001 * |

| Severity Stages of COPD | Variables | [95% CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Mild/moderate stages of COPD (GOLD grades 1 and 2) Severe/very severe stages of COPD (GOLD grades 3 and 4) | CRP NT-proBNP | [3.241–29.325] [246.965–699.269] | 0.015 * 0.000 * |

| Model 2 | |||

| Mild/moderate stages of COPD (GOLD grades 1 and 2) Severe/very severe stages of COPD (GOLD grades 3 and 4) | CRP NT-proBNP | [3.821–30.112] [276.313–714.513] | 0.012 * 0.000 * |

| Model 3 | |||

| Mild/moderate stages of COPD (GOLD grades 1 and 2) Severe/very severe stages of COPD (GOLD grades 3 and 4) | CRP NT-proBNP | Y (severity stages of COPD) = −0.962 + 0.028 × CRP Y (severity stages of COPD) = −4.125 + 0.009 × NT-proBNP | 0.024 * 0.000 * |

| Severity Stages of COPD | Variables | [95% CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Mild/moderate stages of COPD (GOLD grades 1 and 2) Severe/very severe stages of COPD (GOLD grades 3 and 4) | LV GLS TAPSE FAC-RV RV4CLS RVFWSL PASP S’RV | [−19.204–−18.506] [17.892–19.039] [29.105–32.994] [−16.032–−15.439] [−18.384–−17.821] [33.946–36.703] [11.173–12.203] | 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.000 * |

| Model 2 | |||

| Mild/moderate stages of COPD (GOLD grades 1 and 2) Severe/very severe stages of COPD (GOLD grades 3 and 4) | LV GLS TAPSE FAC-RV RV4CLS RVFWSL PASP S’RV | [−19.204–−18.501] [17.887–19.051] [29.097–32.961] [−16.026–−15.462] [−18.380–−17.840] [33.922–36.698] [11.174–12.205] | 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.001 * 0.000 * |

| Model 3 | |||

| Mild/moderate stages of COPD (GOLD grades 1 and 2) Severe/very severe stages of COPD (GOLD grades 3 and 4) | LV GLS TAPSE FAC-RV PASP S’ RV | Y (severity stages of COPD) = 28.901 + 1.542 × GLS Y (severity stages of COPD) = 16.245–0.903 × TAPSE Y (severity stages of COPD) = 8.176–0.263 × FAC-RV Y (severity stages of COPD) = −7.855 + 0.214 × PASP Y (severity stages of COPD) = 9.241–0.823 × S’ RV | 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.000 * 0.001 * 0.000 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hojda, S.-E.; Mocan, T.; Pop, A.-L.; Rusnak, R.; Bidian, C.; Clichici, S.V. Right Ventricular Strain and Left Ventricular Strain Using Speckle Tracking Echocardiography—Independent Prognostic Associations in COPD Alongside NT-proBNP. Diseases 2025, 13, 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13100344

Hojda S-E, Mocan T, Pop A-L, Rusnak R, Bidian C, Clichici SV. Right Ventricular Strain and Left Ventricular Strain Using Speckle Tracking Echocardiography—Independent Prognostic Associations in COPD Alongside NT-proBNP. Diseases. 2025; 13(10):344. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13100344

Chicago/Turabian StyleHojda, Silvana-Elena, Teodora Mocan, Alexandra-Lucia Pop, Ramona Rusnak, Cristina Bidian, and Simona Valeria Clichici. 2025. "Right Ventricular Strain and Left Ventricular Strain Using Speckle Tracking Echocardiography—Independent Prognostic Associations in COPD Alongside NT-proBNP" Diseases 13, no. 10: 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13100344

APA StyleHojda, S.-E., Mocan, T., Pop, A.-L., Rusnak, R., Bidian, C., & Clichici, S. V. (2025). Right Ventricular Strain and Left Ventricular Strain Using Speckle Tracking Echocardiography—Independent Prognostic Associations in COPD Alongside NT-proBNP. Diseases, 13(10), 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases13100344