Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis in an Adolescent Girl: An Atypical Presentation of an Unexpected Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

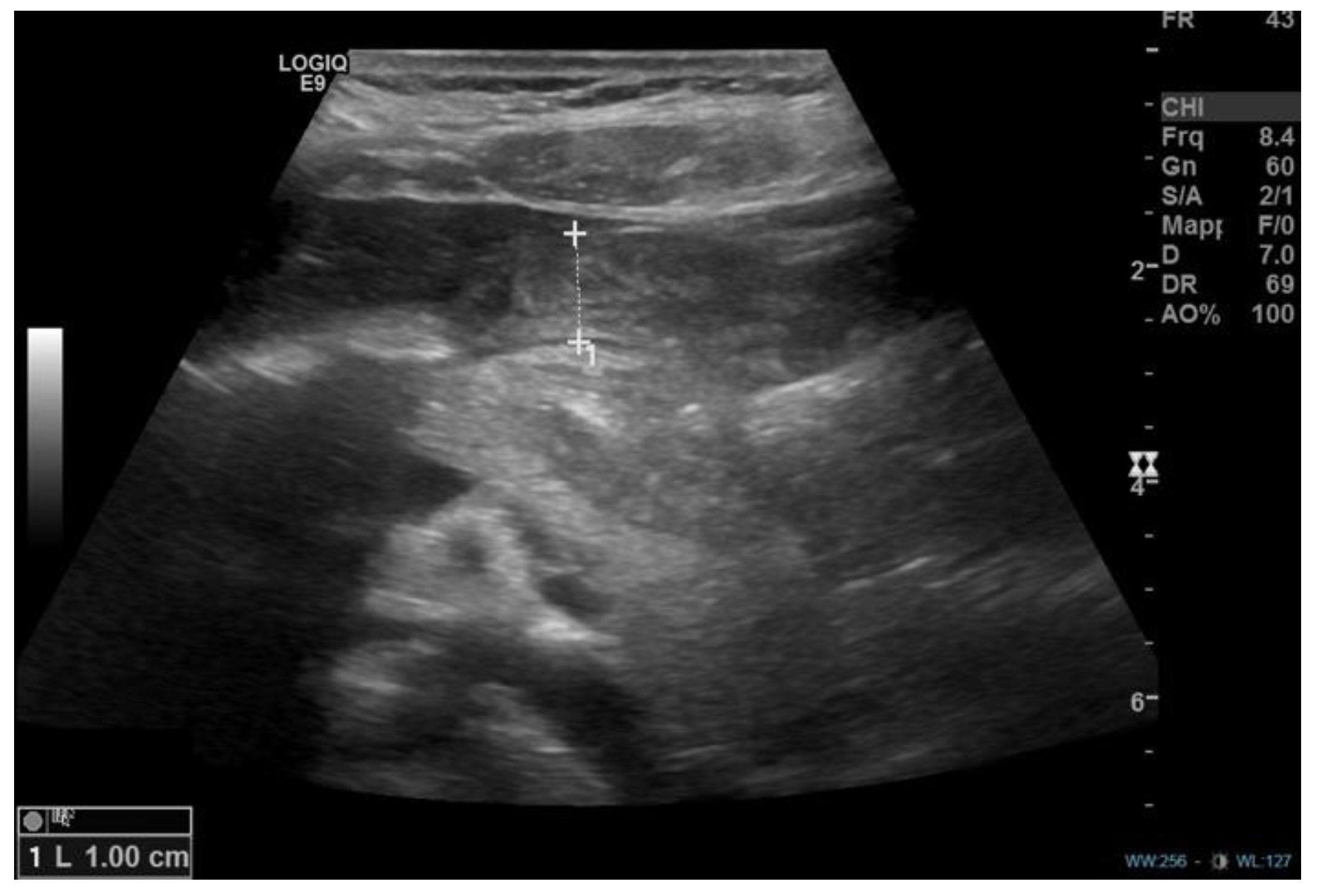

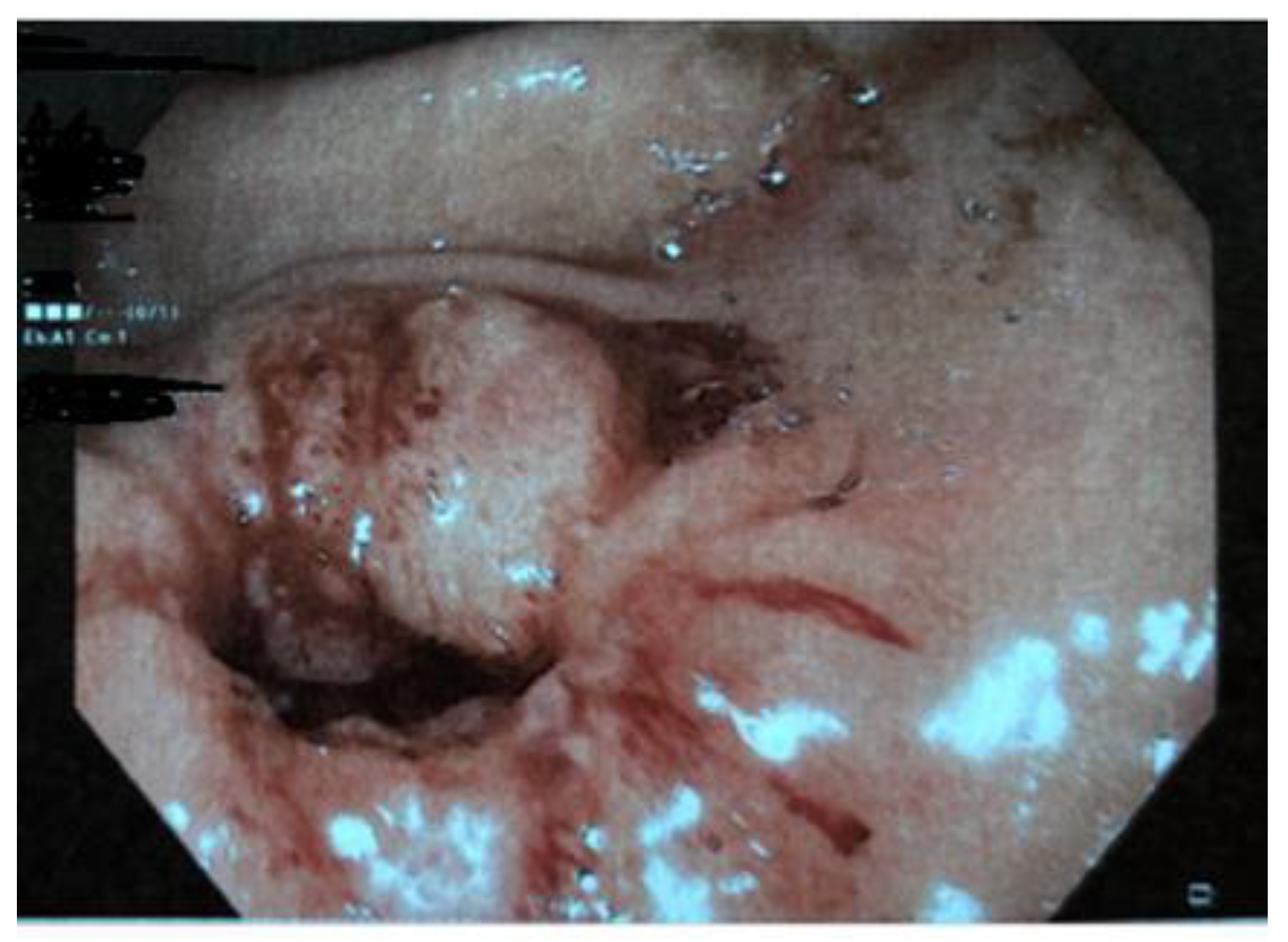

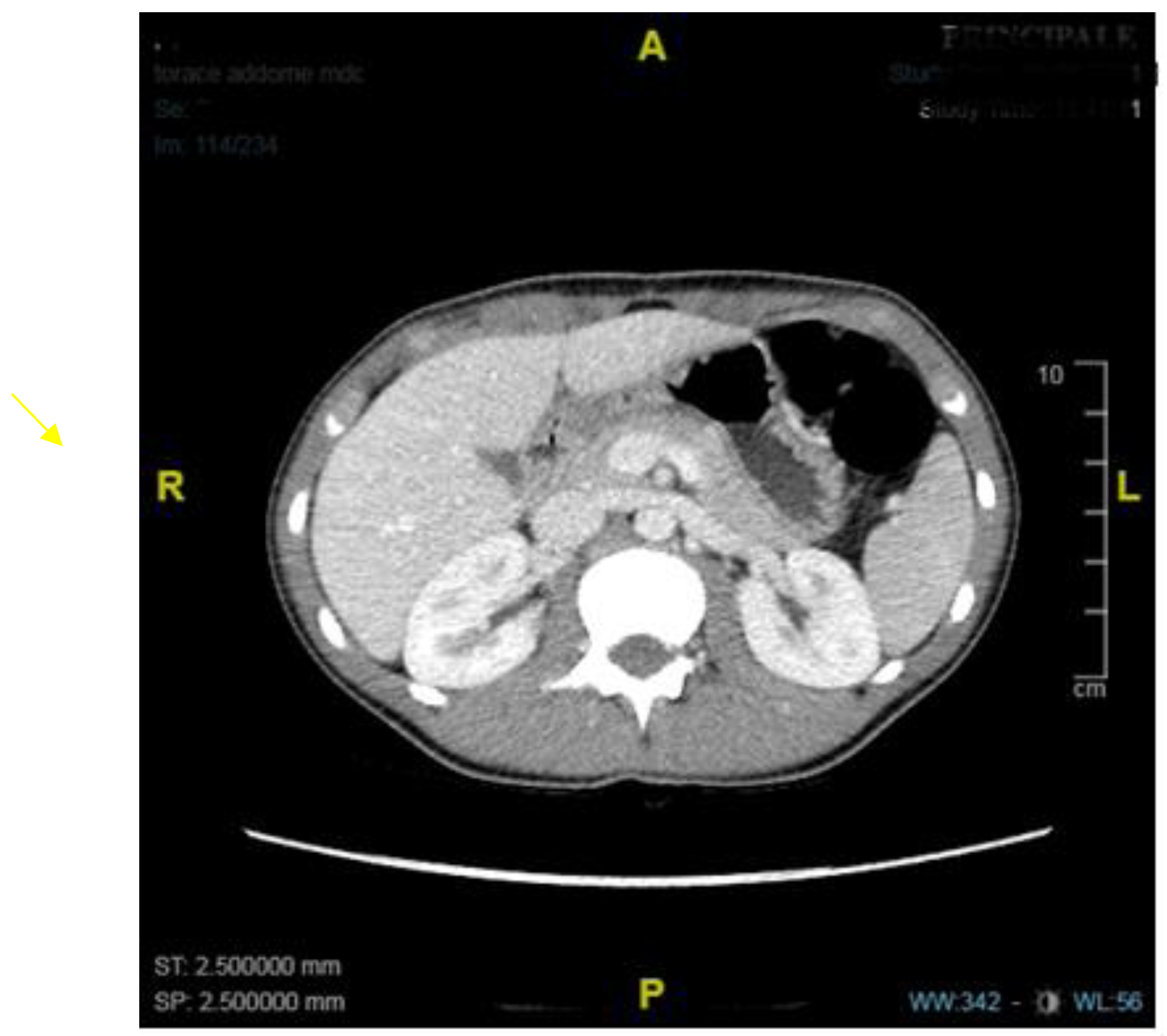

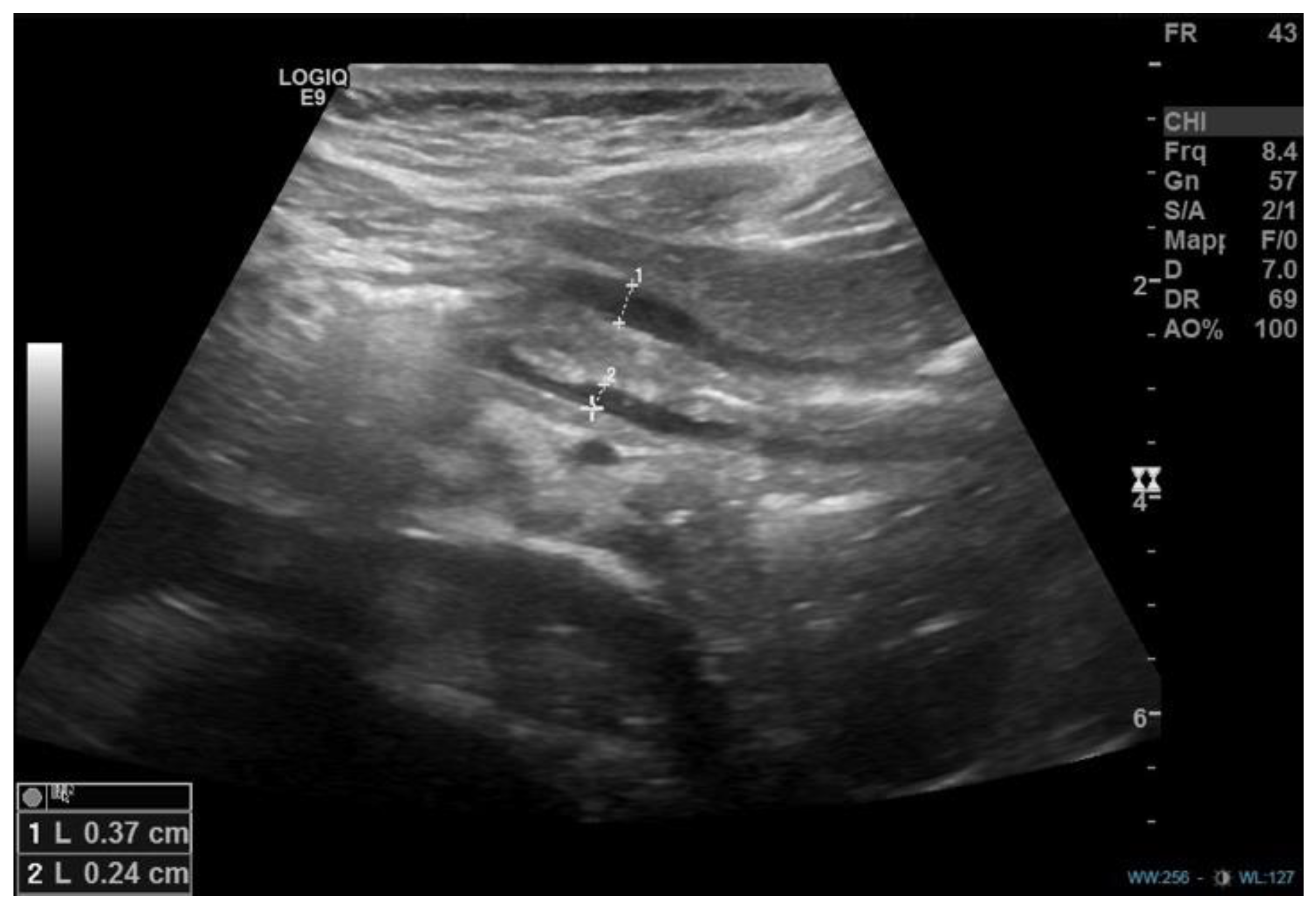

2. Discussion

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cook, R.C.; Rickham, P.P. Gastric outlet obstruction. Neonatal. Surg. 1978, 6, 335–352. [Google Scholar]

- Jobson, M.; Hall, N. Contemporary management of pyloric stenosis. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2016, 25, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taliaferro, L.; Barnett, T.A.; Mann, N.S. Adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Case report. Texas Med. 1986, 82, 27.e8. [Google Scholar]

- Thielemann, H.; Anders, S.; Na¨veke, R.; Diermann, J.H. Primary hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. A rare form and stomach outlet stenosis in the adult. Zentralbl. Chir. 1999, 124, 947–949. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simson, J.N.L.; Thomas, A.J.; Stoker, T.A.M. Adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and gastric carcinoma. Br. J. Surg. 1986, 73, 379–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selzer, D.; Croffie, J.; Breckler, F.; Rescorla, F. Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in an adolescent. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2009, 19, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnall, T.; Caldwell, K.; Noel, J.; Russell, J.; Reyes, C. Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a 15-year-old male. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2016, 15, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, L.; Nijagal, A.; Flores, A.; Buchmiller, T. Late-onset hypertrophic pyloric stenosis with gastric outlet obstruction: Case report and review of the literature. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2016, 32, 1013–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Agrawal, P.; Toshniwal, H. Acquired gastric outlet obstruction during infancy and childhood: A report of five unusual cases. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1997, 32, 928–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Ranka, P.; Goyal, P.; Dabi, D. Gastric outlet obstruction in children: An overview with report of Jodhpur disease and Sharma’s classification. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2008, 43, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajal, P.; Bhutani, N.; Kadian, Y.S. Primary acquired gastric outlet obstruction (Jodhpur disease). J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2019, 40, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynes, W.M. Simple and complicated hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in the adult. Gut 1965, 6, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, J.A. Adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Br. J. Surg. 1973, 60, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plessi, C.; Sica, M.; Molinaro, F.; Fusi, G.; Rossi, F.; Costantini, M.; Roviello, F.; Marano, L.; D’ignazio, A.; Spinelli, C.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) in older children. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 69, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, S.; Prasad, A.; Sinha, A.; Kulshrestha, R. Delayed presentation of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A rare case. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2010, 45, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boybeyi, O.; Karnak, I.; Ekinci, S.; Ciftci, A.O.; Akçören, Z.; Tanyel, F.C.; Senocak, M.E. Late-onset hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Definition of diagnostic criteria and algorithm for the management. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2010, 45, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, M.; Singh, A.; Panda, S.S.; Chand, K.; Rafey, A.R. Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in an older child: A rare presentation with successful standard surgical management. Case Rep. 2013, 20, bcr2013201834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mayoof, A.F.; Doghan, I.K. Late onset infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2018, 30, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, E.; Carlisle, E.; Mak, G. Gastric outlet obstruction in a 12 year old male. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2018, 31, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswari, H.; Kresnawati, W.; Yani, A.; Handjari, D.; Alatas, F. Abdominal injury induced gastric outlet obstruction in primary hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in adolescent. Indian J. Surg. 2020, 83, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello, O.; Verriello, G.; Castellaneta, S.; Palladino, S.; Wong, M.; Mattioli, G.; Giordano, P.; Francavilla, R.; Cristofori, F. Case report: Late-onset hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a 3-year-old boy: It is never too late. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 949144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumhageen, J.; Krauter, D.; Rosenbaum, D.; Weinberger, E. Sonographic diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1988, 150, 1367–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, C.; Swinson, S.; Torrão, S.; Gonçalves, L.; Kurochka, S.; Vaz, C.P.; Mendes, V. Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Tips and tricks for ultrasound diagnosis. Insights Imaging 2012, 3, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenaga, T.; Honmyo, U.; Takano, S.; Murakami, A.; Harada, K.; Mizumoto, S.; Yoshinaka, I.; Hirata, T.; Maeda, M.; Kiyohara, H. Primary hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in the adult. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1992, 7, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, S.R.; Colodny, A.H. A useful maneuver to simplify pyloromyotomy for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Surgery 1964, 55, 735–736. [Google Scholar]

- Binet, A.; Klipfel, C.; Meignan, P.; Bastard, F.; Cook, A.R.; Braïk, K.; Le Touze, A.; Villemagne, T.; Robert, M.; Ballouhey, Q.; et al. Laparoscopic pyloromyotomy for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A survey of 407 children. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2018, 34, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, C.M.; Vinocur, C.; Berman, L. Postoperative outcomes of open versus laparoscopic pyloromyotomy for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J. Surg. Res. 2018, 224, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podboy, A.; Hwang, J.H.; Nguyen, L.A.; Garcia, P.; Zikos, T.A.; Kamal, A.; Triadafilopoulos, G.; Clarke, J.O. Gastric per-oral endoscopic myotomy: Current status and future directions. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 2581–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year | Number of Cases | Age | Symptoms | Investigations (Prior to Surgery) | Further Endoscopic Findings | Treatments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selzer et al. [6], 2009 | 1 | 14 years | Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain | UGI series | Eosinophilic esophagitis | HMP |

| Mahalik et al. [15], 2010 | 1 | 4,5 years | Non bilious vomiting | US, UGI series, CT scan | - | OP |

| Boybeyi et al. [16], 2010 | 11 | 3,6 (2–8) years (mean age, range) | Vomiting (5 cases) Vomiting + abdominal pain (4 cases) Vomiting + weight loss (2 cases) | US + UGI series (6 cases), UGI series (5 cases), EGDS | Gastric edema and hyperemia (2 cases) | EBD (4 cases)–EBD + B-I (1 case)–B-I (6 cases) |

| Bajpai et al. [17], 2013 | 1 | 8 years | Non bilious vomiting and poor growth | US and X-Ray, EGDS, CT scan, UGI series | - | HMP + temporary jejunostomy |

| Parnall et al. [7], 2016 | 1 | 15 years | Vomiting, early satiety, failure to thrive | US, CT | Prepyloric ulcer (Hp positive) | Botulinum toxin injection (failure), distal gastrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction |

| Wolf et al. [8], 2016 | 1 | 17 years | Abdominal pain, bloating, early satiety, one episode of upper gastrointestinal hemorrage, anemia | EGDS (2), MRI enterography, gastric emptying study using Technetium-99 | Severe gastritis | Botulinum injection (failure), LP |

| Al-Mayoofet al. [18], 2016 | 1 | 7 months | Vomiting, weight loss | UGI series, US | - | OP |

| Bartlett et al. [19], 2018 | 1 | 12 years | Vomiting, failure to thrive | EGDS, US. | Previous history of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastritis. | EBD + Botulinum injection (failure) HMP + temporary gastrostomy |

| Oswari et al. [20], 2020 | 1 | 11 years | Vomiting, previous history of epigastric trauma | UGI series, EGDS, CT scan | B-I | |

| Plessi et al. [14], 2021 | 1 | 12 years | Vomiting, growth failure (underlying diagnosis: Down’s Syndrome) | Abdominal US, UGI series (2), MRI, EGDS (2) | - | EBD + electrosurgical incisions (failure), distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-y reconstruction |

| Iacoviello et al. [21], 2022 | 1 | 3 years | Vomiting, rumination and weight loss | Abdominal US and X-Ray, UGI series (2), CT scan, EGDS, MRI. | - | EBD (failure) OP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gatti, S.; Piloni, F.; Bindi, E.; Cruccetti, A.; Catassi, C.; Cobellis, G. Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis in an Adolescent Girl: An Atypical Presentation of an Unexpected Disease. Diseases 2023, 11, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases11010019

Gatti S, Piloni F, Bindi E, Cruccetti A, Catassi C, Cobellis G. Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis in an Adolescent Girl: An Atypical Presentation of an Unexpected Disease. Diseases. 2023; 11(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases11010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleGatti, Simona, Francesca Piloni, Edoardo Bindi, Alba Cruccetti, Carlo Catassi, and Giovanni Cobellis. 2023. "Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis in an Adolescent Girl: An Atypical Presentation of an Unexpected Disease" Diseases 11, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases11010019

APA StyleGatti, S., Piloni, F., Bindi, E., Cruccetti, A., Catassi, C., & Cobellis, G. (2023). Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis in an Adolescent Girl: An Atypical Presentation of an Unexpected Disease. Diseases, 11(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases11010019