Optimization of High-Frequency Transmission Line Reflection Wave Compensation and Impedance Matching Based on a DQN-GA Hybrid Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Works

1.2. Contributions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Problem Modeling and Circuit Structure

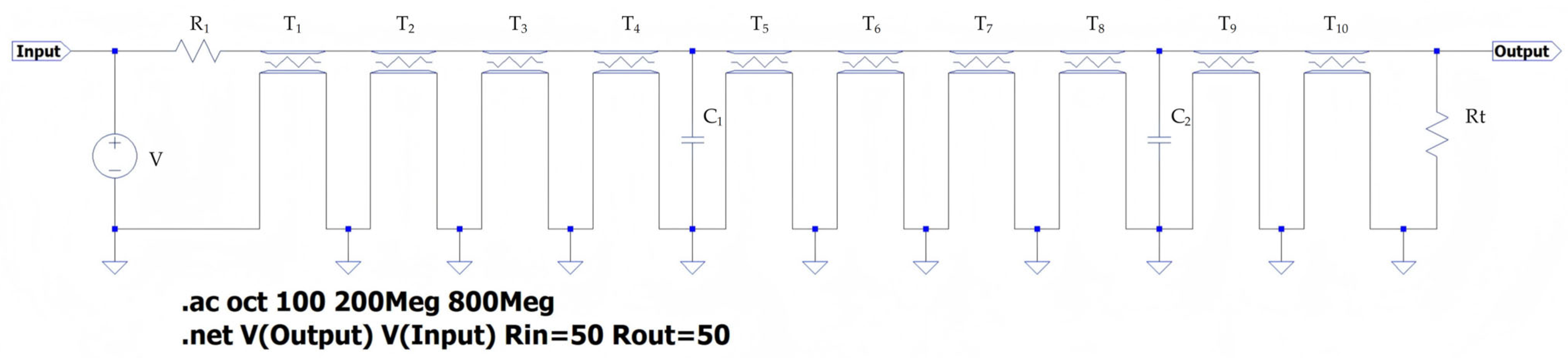

2.1.1. Circuit Model and Optimization Problem Definition

- V: AC excitation source (1 V, frequency sweep from 200 to 800 MHz);

- R1: Series input resistor (optimization variable);

- Rt: Parallel termination resistor (optimization variable);

- C1 = 10 pF: Capacitive load located between the fourth and fifth transmission line segments;

- C2 = 20 pF: Capacitive load located between the eighth and ninth transmission line segments;

- T1–T10: Ten transmission line segments, each with its characteristic impedance Z0,i and time delay Td (corresponding to physical length li) as optimization variables.

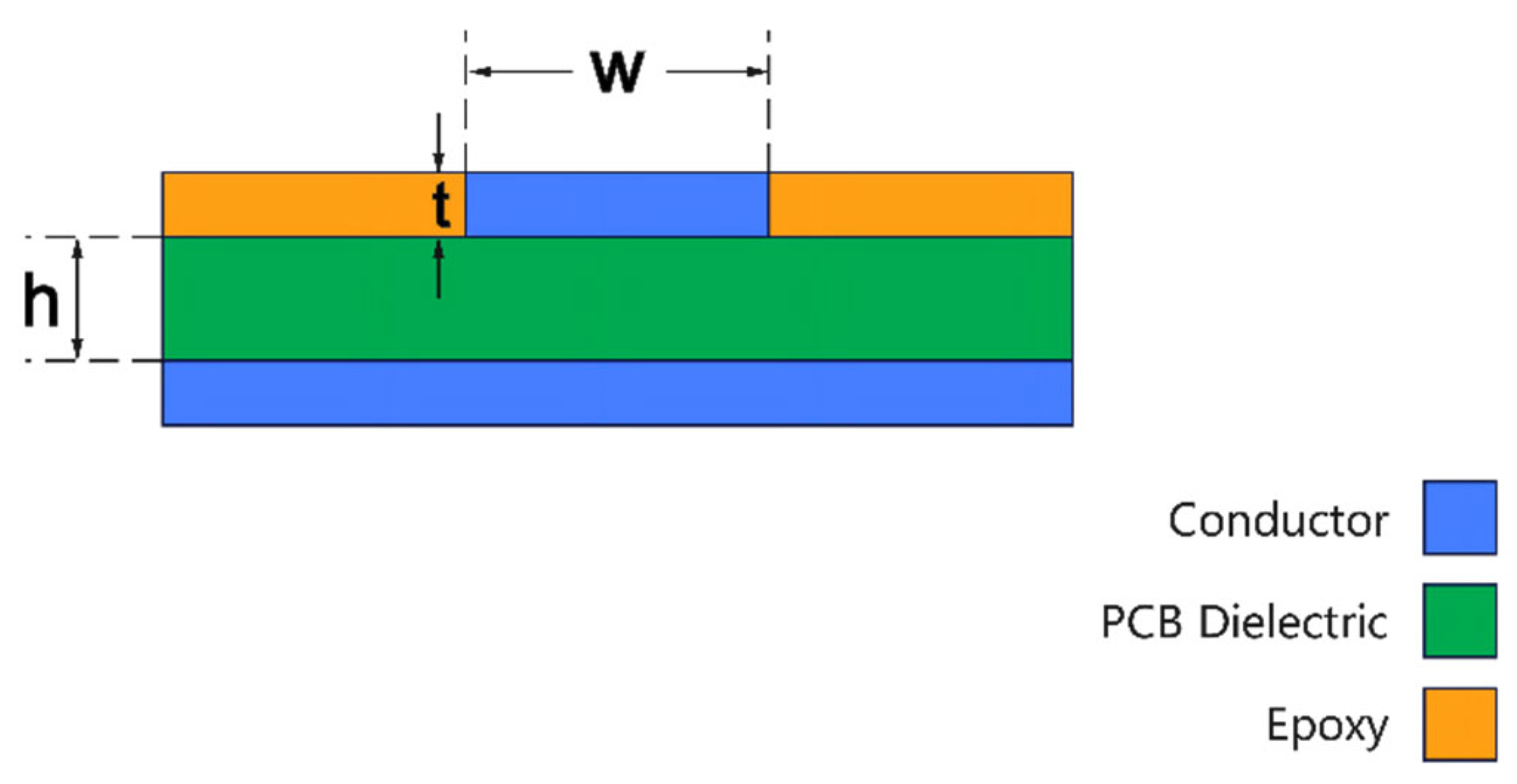

2.1.2. Physical Implementation and Modeling Assumptions

2.1.3. Reflected Wave Compensation Mechanism

- The amplitude of the reflected wave, which is determined by the impedance ratio Z0,(i+1)/Z0,i of adjacent segments.

- The phase of the reflected wave, which is determined by the propagation delay 2 × ΣTdi.

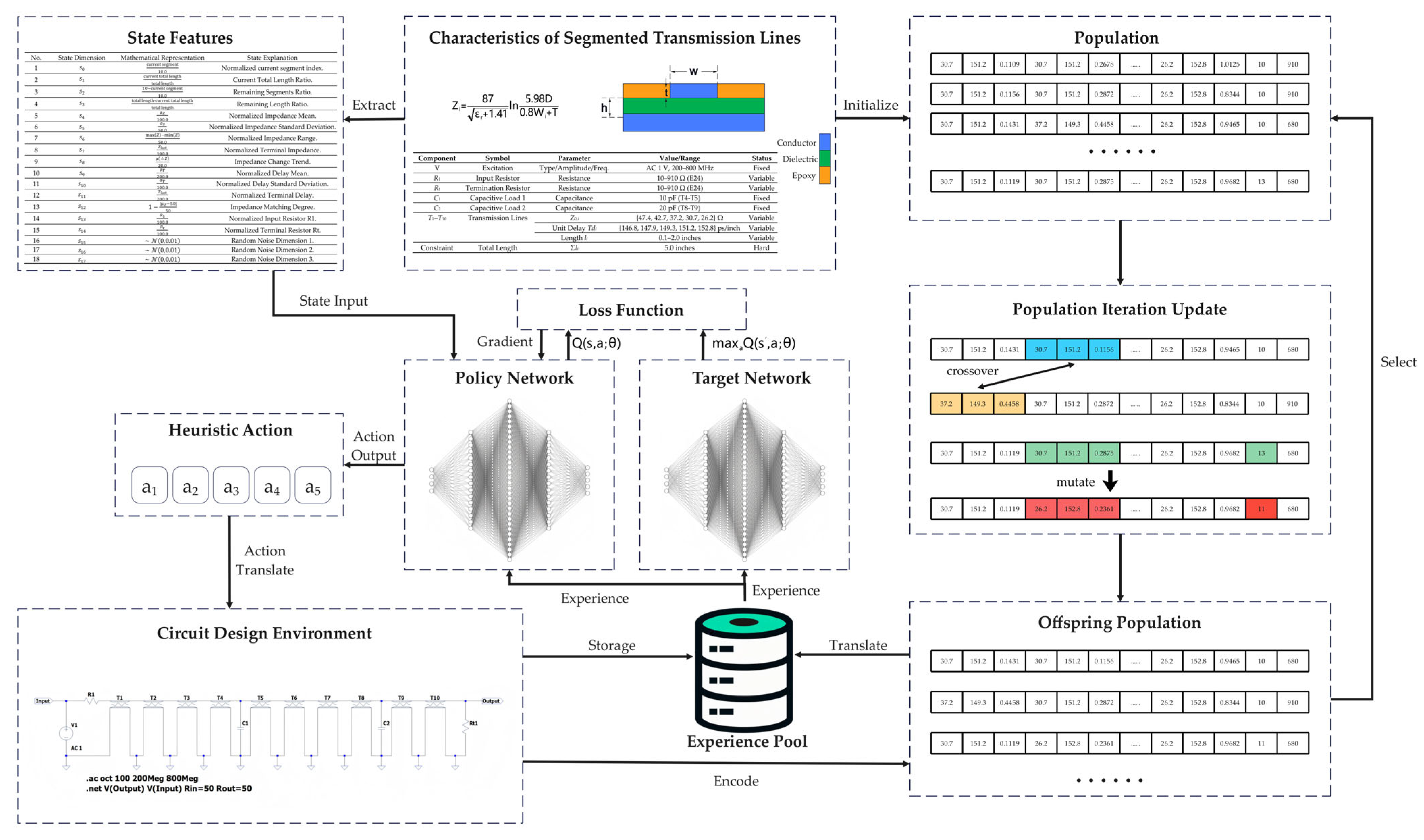

2.2. The DQN-GA Algorithm: Integrating Deep Q-Learning with Genetic Algorithm

- DQN Component (left side):

- State Network: Receives the transmission line parameter state vector st.

- Experience Replay Pool: Stores historical experiences (st, at, rt+1, st+1).

- Q-value Update: Updates network parameters via temporal-difference learning.

- Storage: Store the optimal solution in the experience pool.

- GA Component (right side):

- Population Initialization: Generates an initial set of chromosomes.

- Genetic Operations: Selection, crossover, and mutation.

- Fitness Evaluation: Computes the fitness value for each individual.

- Translate and storage: Select optimal offspring and store them in the experience pool.

- Bidirectional interaction mechanism (center):

- DQN → GA direction: The policy parameters learned by the DQN are encoded into GA chromosomes to guide population evolution.

- GA → DQN direction: The elite individuals discovered by the GA search are decoded into training experiences for the DQN, thereby enriching the experience pool.

2.2.1. DQN Component Design

- 1.

- Segment progress information (dimensions 0–3):

- Current segment index normalization (): Reflects the progress of transmission line construction.

- Current total length normalization (): Represents the proportion of constructed length to the total length (5.0 inches).

- Remaining segment count normalization (): Quantifies the number of segments yet to be completed.

- Remaining length normalization (): Indicates the remaining construction space.

- 2.

- Impedance statistical features (dimensions 4–8):

- Impedance mean normalization (): Captures the average level of historical impedance.

- Impedance standard deviation normalization (): Measures the degree of impedance fluctuation.

- Impedance range normalized (): Reflects the range of impedance variation.

- Terminal impedance normalized (): Emphasizes the impedance value of the most recent segment.

- Impedance change trend (): Calculates the mean of impedance differences between adjacent segments, characterizing the sequence dynamics.

- 3.

- Delay statistical features (dimensions 9–11):

- Delay mean normalized ().

- Delay standard deviation normalized ().

- Terminal delay normalized ().

- 4.

- Impedance Matching Degree (dimension 12):

- Target Matching Degree (): Quantifies the deviation of the current average impedance from the target value (50 Ω). A value closer to 1 indicates better matching.

- 5.

- Resistance Information (dimensions 13–14):

- Normalized Input Resistance R1 ().

- Normalized Termination Resistance Rt ().

- 6.

- Exploration–Enhancing Noise (dimensions 15–17):

- Feature Selection: The agent selects an action index from a predefined feature set, employing either an ε-greedy strategy or neural network Q-value prediction.

- Length Determination: Once a feature is selected, the length of the transmission line segment is determined via an adaptive mechanism:

- Parameter Update: The selected features and the computed length are added to the current transmission line structure, updating the environment state.

- Total Length Constraint: The sum of all segment lengths is strictly equal to the total length of 5.0 inches, enforced via a dynamic adjustment mechanism. The scaling factor is calculated as follows:

- Fabrication Feasibility Constraint: All impedance values are drawn from a predefined set achievable with practical microstrip line fabrication processes, preventing unrealistic design proposals.

- Sequence Integrity Constraint: When the current segment index reaches 10, the action selection process is terminated, completing the construction of the transmission line structure.

- Length matching reward:

- Impedance matching reward (intermediate step):

- Multi-Objective Optimization Strategy: The design of the reward function embodies a balance among the following optimization objectives:

- Maximizing transmission efficiency: The term S21,500 MHz encourages a high transmission coefficient, directly corresponding to a core metric of signal integrity.

- Minimizing reflection loss: The term |S11,500 MHz| suppresses reflection phenomena. Its weight coefficient of 0.02 was experimentally tuned to ensure an effective balance between these two objectives.

- Ensuring physical feasibility: Auxiliary rewards guarantee that the design adheres to engineering constraints: the total length is strictly constrained to 5.0 inches, the impedance distribution is reasonable, and extreme mismatch conditions are avoided.

- Reward Calculation Process: Based on the code implementation, the specific workflow for calculating rewards is as follows:

| Algorithm 1. Reward Calculation Process |

| Input: Current transmission line structure parameters, resistor configuration Output: Reward value r 1: Execute LTspice simulation to obtain S-parameter data 2: Extract S21 and S11 values at 500 MHz 3: Calculate base reward: rbase = S21,500 + 0.02 × |S11,500| 4: Verify total length constraint: 5: if |totallength − 5.0| < 0.01 then 6: rlength = 0.5 7: else 8: rlength = 0 9: end if 10: Calculate current average impedance Zavg 11: Calculate impedance matching reward: rimpedance = (1 − |Zavg − 50|/50) × 0.1 12: Comprehensive reward: r = rbase + rlength + rimpedance 13: Return r |

- Input Layer: 18 neurons, corresponding to the 18 dimensions of the state vector;

- Hidden Layer 1: 256 neurons, using the ReLU activation function;

- Hidden Layer 2: 512 neurons, using the ReLU activation function;

- Hidden Layer 3: 256 neurons, using the ReLU activation function;

- Output Layer: 5 neurons, corresponding to the 5 selectable transmission line features in the action space.

- Experience pool capacity: 20,000 transition samples .

- Batch processing sampling: Each training step randomly samples 512 experiences, breaking the temporal correlation in the data.

- Prioritized Experience Replay: Sampling based on Temporal Difference error to enhance learning efficiency.

- Initial exploration rate: (complete random exploration).

- Decay mechanism: , decaying at each step.

- Minimum exploration rate: , ensuring sustained exploration ability.

- Initial learning rate: 0.0005;

- Dynamic decay: The learning rate is multiplied by 0.95 every 50 training epochs;

- Gradient clipping: Gradient norm threshold of 1.0 to prevent gradient explosion;

| Algorithm 2. DQN Training Main Loop |

| Input: Environment Env, Training episodes EPISODES Output: Trained Q-network parameters 1: Initialize prediction network Q and target network Qtarget parameters 2: Initialize experience replay buffer D 3: Initialize exploration rate ε, learning rate α 4: for episode = 1 to EPISODES do 5: Initialize environment, obtain initial state s 6: Calculate current temperature T ← max(Tmin, 1.0 − episode/EPISODES × δ) 7: for step = 1 to SEGMENT_COUNT do # Construct transmission line segments 8: # Action selection: Combine ε-greedy and temperature scheduling 10: # Environment interaction: Execute action and observe feedback 11: Execute action a, observe reward r and next state s’ 12: Store experience (s,a,r,s’) to experience buffer D 13: # Network training: Experience replay and parameter update 14: if |D| ≥ BATCH_SIZE then 15: Randomly sample a batch of experiences from D 18: Update Q-network parameters using Adam optimizer 20: end if 21: s ← s’ # State transition 22: end for 23: # Parameter decay: Gradually reduce exploration rate and learning rate 24: ε ← max(εmin, ε × εdecay) 25: if episode % LR_DECAY_FREQ == 0 then 26: α ← α × LR_DECAY_RATE 27: end if 28: end for 29: Return trained Q-network parameters |

2.2.2. GA Component Design

- Randomly select two crossover points, dividing the chromosome into head, middle, and tail sections.

- Exchange the middle gene segments of the two parent chromosomes.

- Perform length normalization on the offspring to ensure the total length constraint is satisfied.

2.2.3. Bidirectional Interaction Mechanism

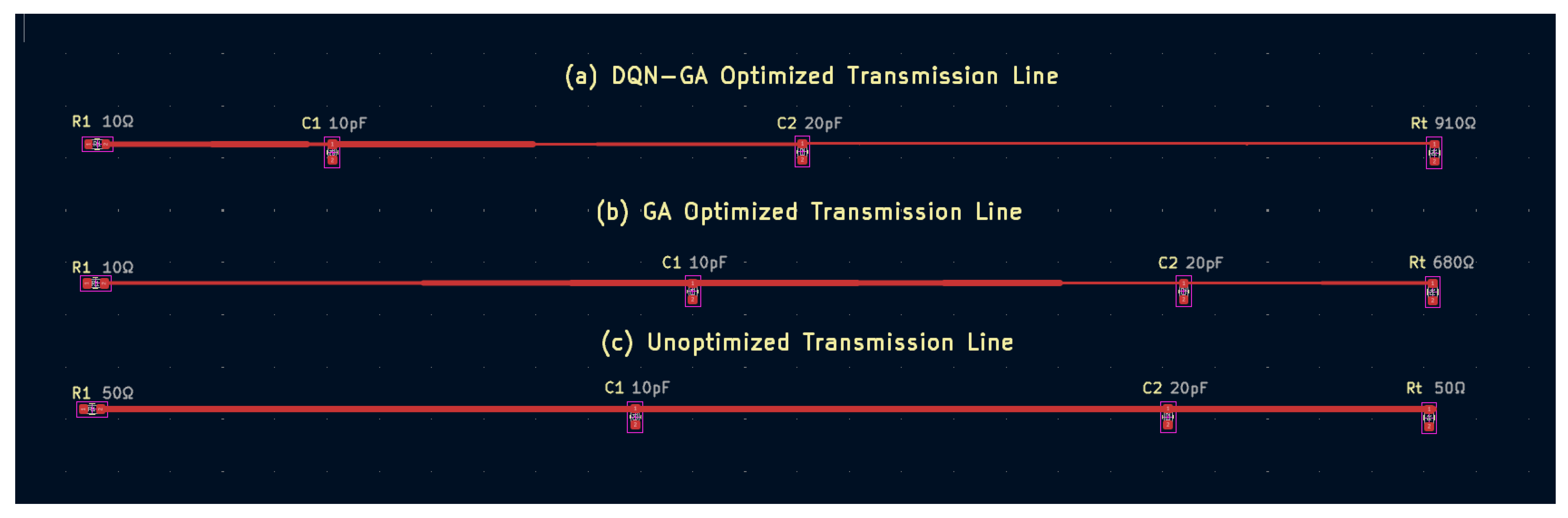

3. Simulation and Results

3.1. Simulation Setup

3.1.1. Simulation Environment

3.1.2. Algorithm Hyperparameters

3.1.3. Training Configuration

3.1.4. Performance Evaluation Metrics

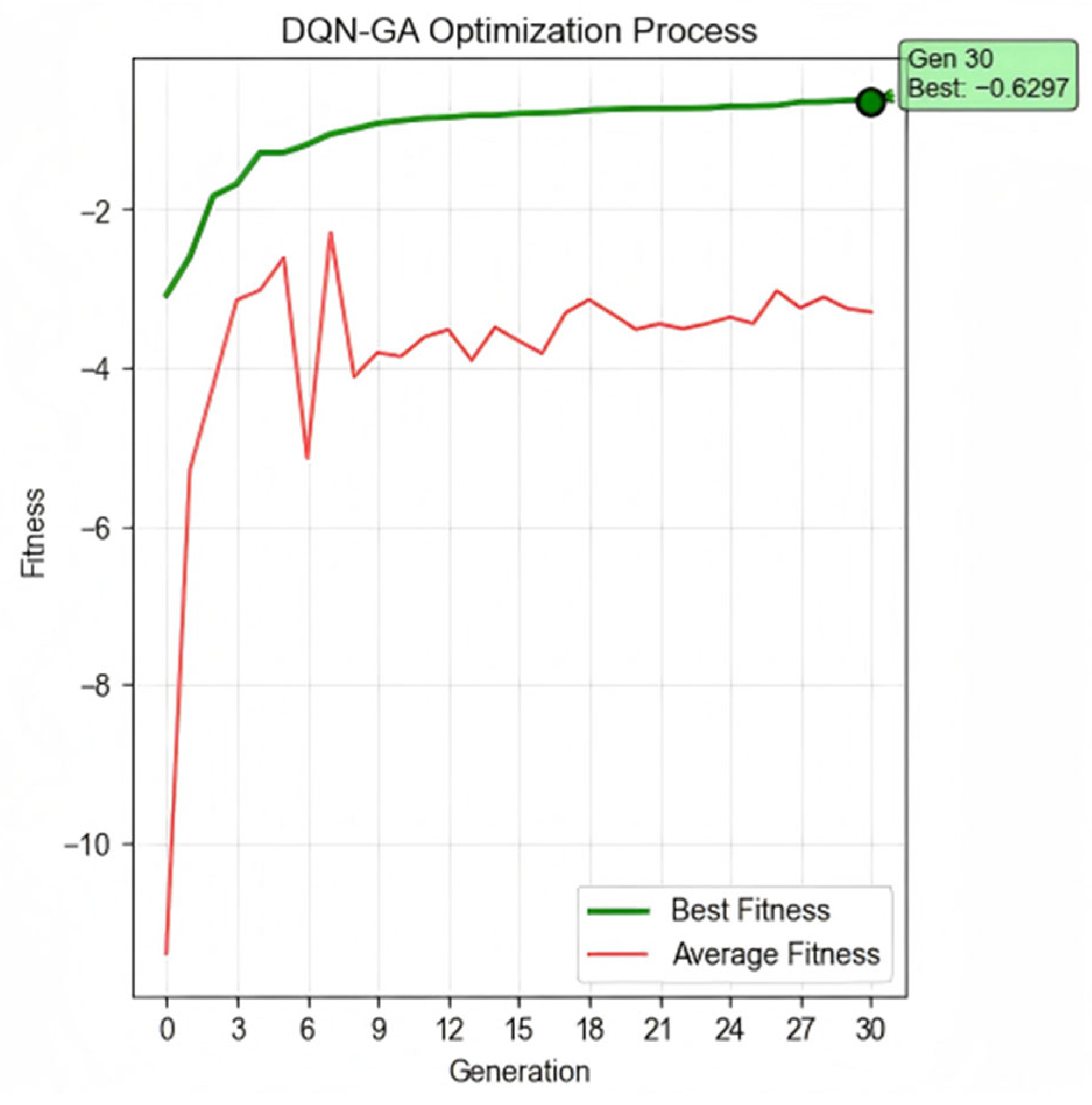

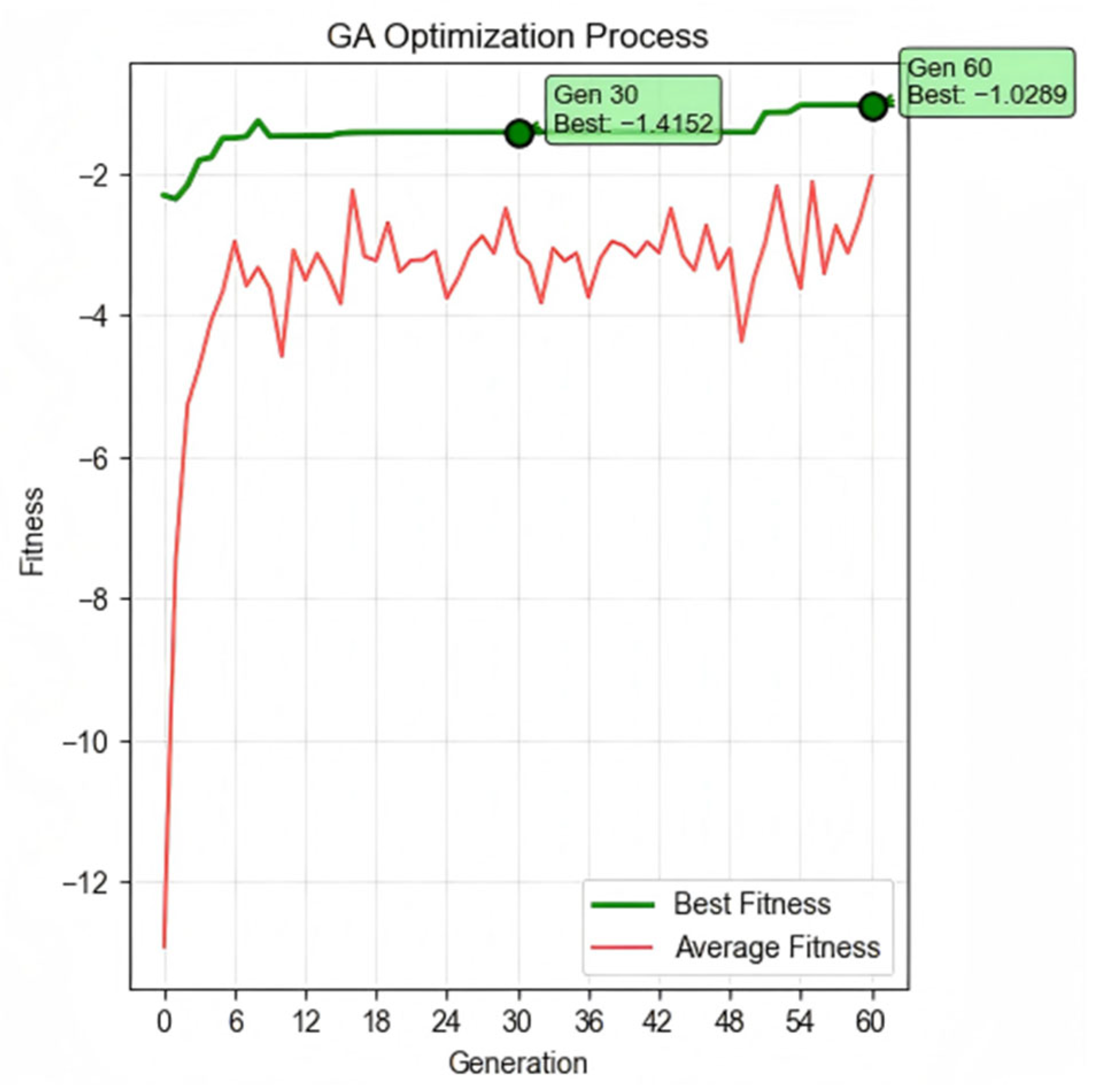

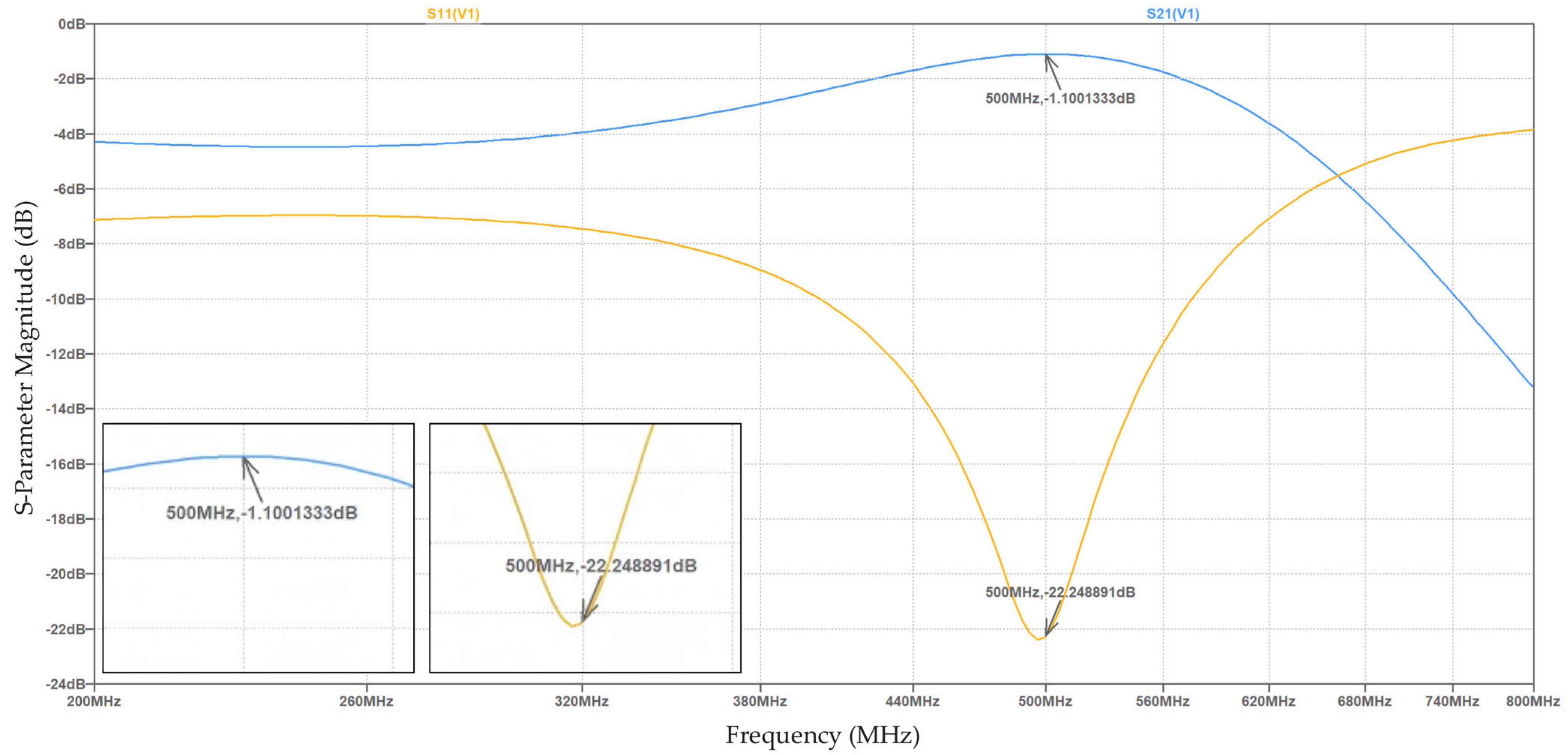

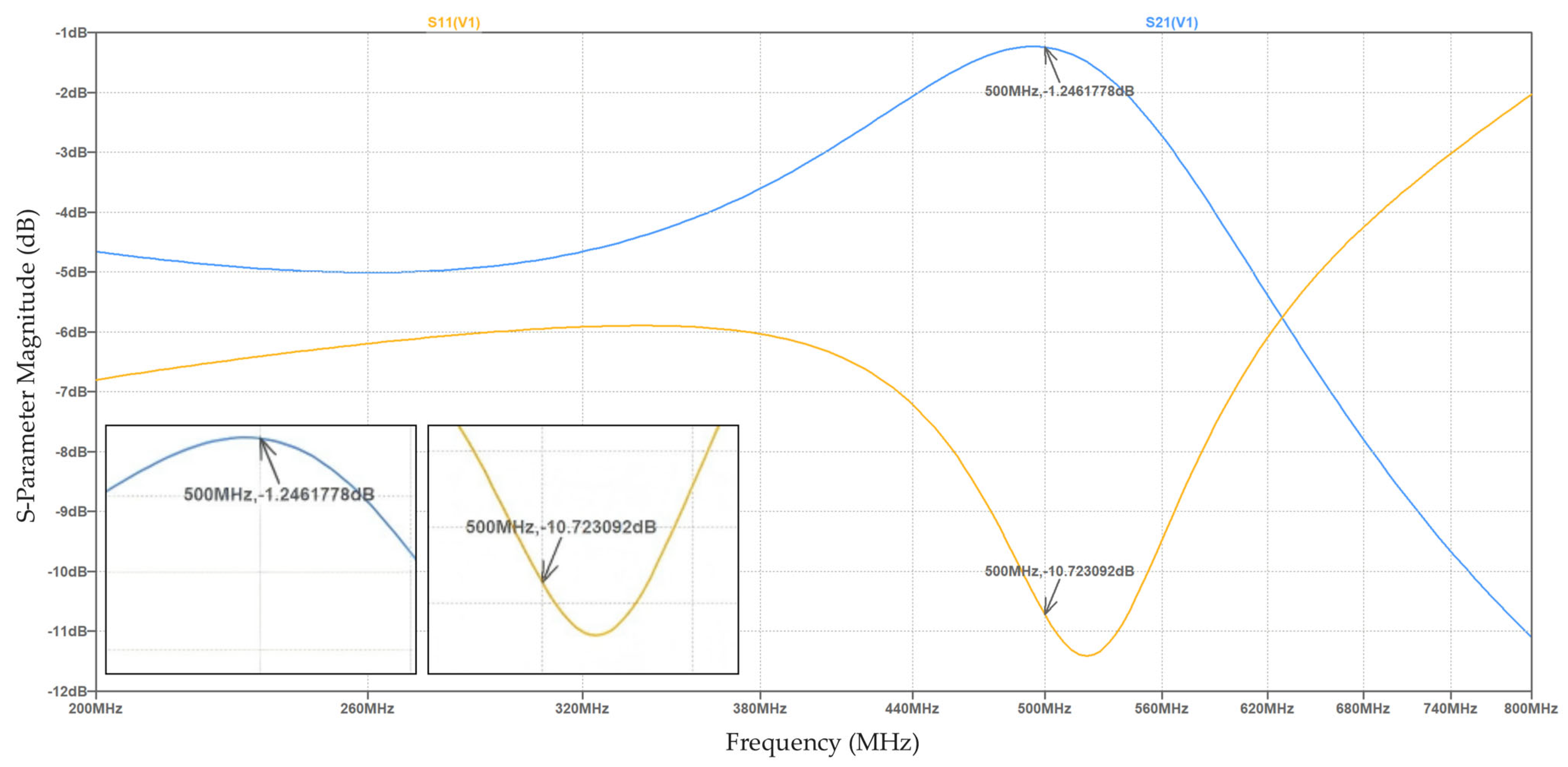

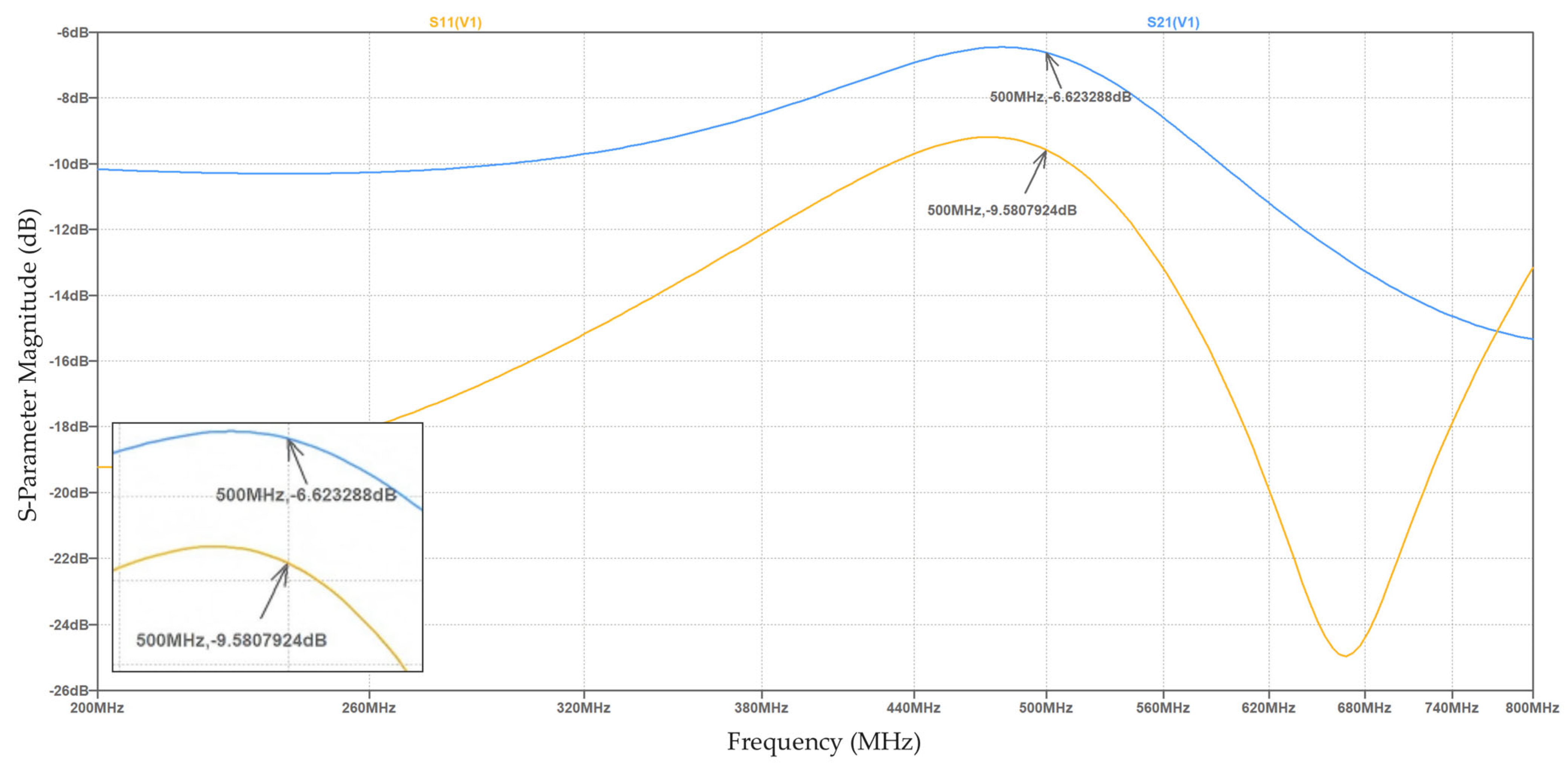

3.2. Optimization Results

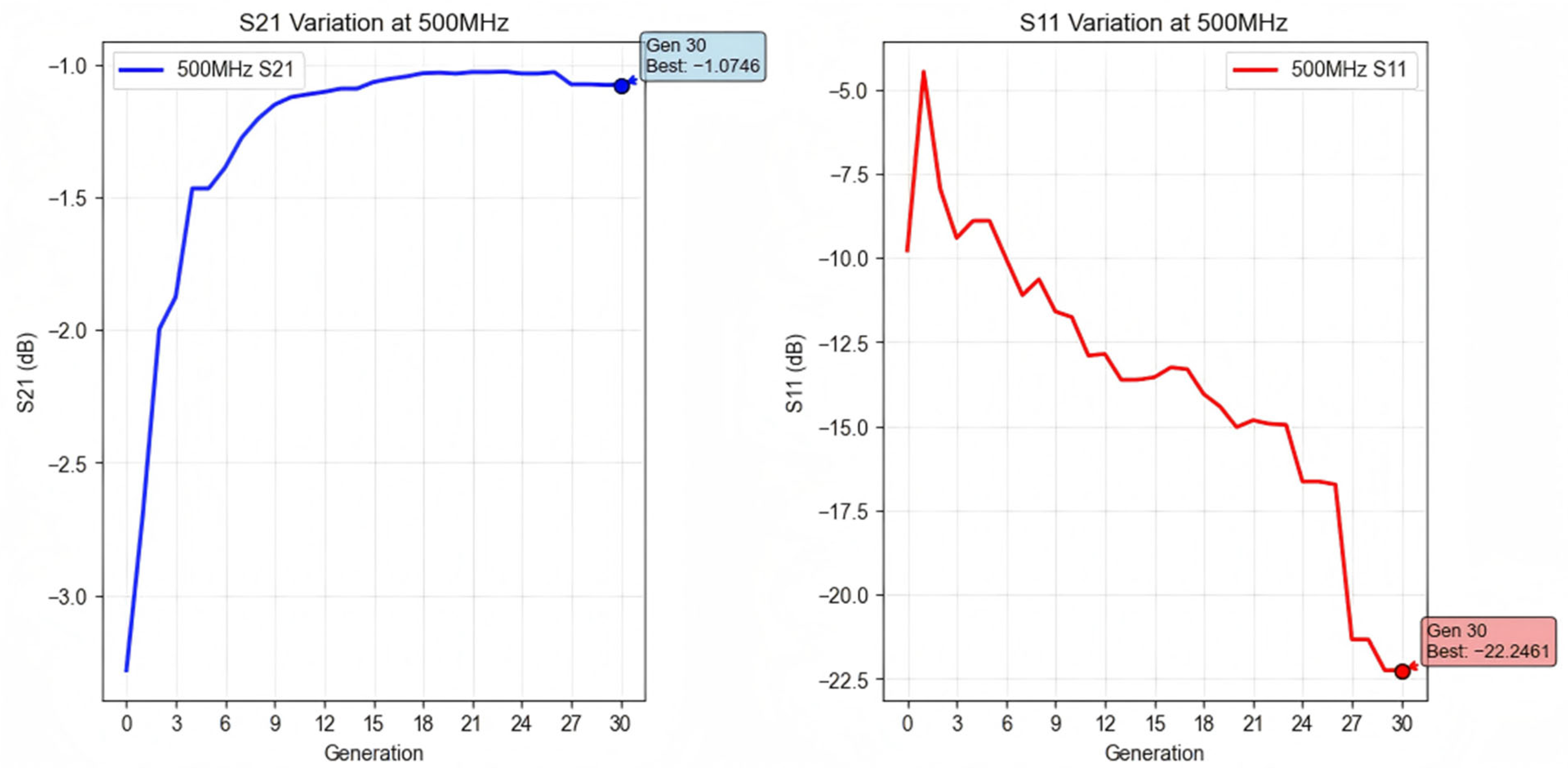

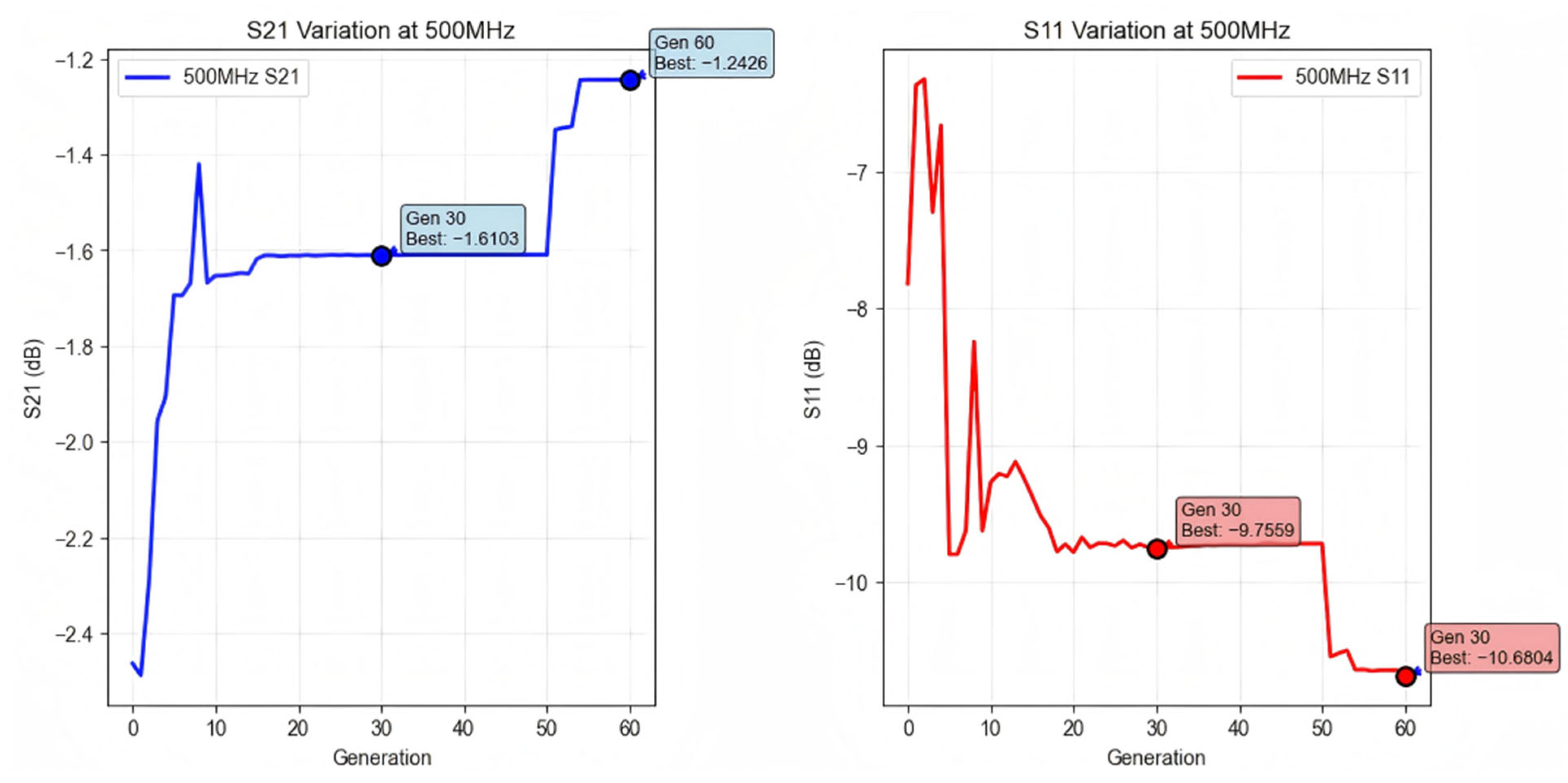

- The GA approach achieved a fitness of −1.4152 at the 30th generation, representing a 78.0% improvement;

- The DQN-GA algorithm reached an optimal solution fitness of −0.6297, achieving a 90.2% improvement over the unoptimized baseline.

- GA optimization achieved −10.723 dB, representing an 11.9% improvement;

- DQN-GA optimization achieved −22.249 dB, representing a 132.2% improvement.

- GA optimization achieved −1.246 dB, representing an 81.2% improvement in transmission efficiency;

- DQN-GA optimization achieved −1.100 dB, representing an 83.4% improvement.

3.3. Comparative Analysis

3.4. Computational Cost Analysis

3.4.1. Simulation Platform and Implementation Details

3.4.2. Execution Time Comparison

3.4.3. Simulation Call Analysis

- DQN-GA: 30,000 simulations (300 episodes × 100 steps per episode).

- GA: 3000 simulations (60 generations × 50 population size).

- Ratio: 10:1 (DQN-GA requires 10 times more simulations).

3.4.4. Hardware Resource Utilization

3.4.5. Scalability and Practical Deployment

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Optimization Results

4.2. Analysis of Computational Efficiency Trade-Offs

4.3. Practical Implications and Applications

4.4. Methodological Insights and Algorithm Behavior

5. Conclusions

5.1. Concluding Summary

5.2. Principal Contributions

5.3. Research Limitations

5.3.1. Limitations of Simulation Verification

5.3.2. Limitations in Model Simplification and Optimization Scope

5.4. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, T.; Sun, J.; Wu, K.; Yang, Z. High-Speed Channel Modeling with Machine Learning Methods for Signal Integrity Analysis. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2018, 60, 1957–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.H.; Xue, Z.S.; Liu, X.Y.; Li, P.; Jiang, L.; Shi, G.M. Optimization of High-Speed Channel for Signal Integrity with Deep Genetic Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2022, 64, 1270–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Chen, J.; Zheng, J.; Wang, C.; Qian, W. Fast and Data-Efficient Signal Integrity Analysis Method Based on Generative Query Scheme. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manufact. Technol. 2024, 14, 2062–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Hang, W.; Mirhoseini, A.; Tucker, G.; Wang, J.; Wei, W. Reinforcement Learning Driven Heuristic Optimization. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.06639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, M.; Deng, W. Combining Deep Reinforcement Learning with Heuristics to Solve the Traveling Salesman Problem. Chinese Phys. B 2025, 34, 018705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyedabbasi, A.; Aliyev, R.; Kiani, F.; Gulle, M.U.; Basyildiz, H.; Shah, M.A. Hybrid Algorithms Based on Combining Reinforcement Learning and Metaheuristic Methods to Solve Global Optimization Problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 223, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Sun, H.; Fang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z. Deep Learning Framework Testing via Hierarchical and Heuristic Model Generation. J. Syst. Softw. 2023, 201, 111681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, D.; Bartels, T.S.; Pucic, A.; Schröder, B.; Stube, B. AI Driven Power Integrity Compliant Design of High-Speed PCB. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Brugge, Belgium, 2–5 September 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Shoaee, N.G.; Hua, B.; John, W.; Brüning, R.; Götze, J. Enhanced Reinforcement Learning Methods for Optimization of Power Delivery Networks on PCB. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Brugge, Belgium, 2–5 September 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z. Signal Integrity Analysis of Electronic Circuits Based on Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Automation, Electronics and Electrical Engineering (AUTEEE), Shenyang, China, 27–29 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 861–867. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, W.; Tan, C.S.; Rotaru, M.D. Signal Integrity Optimization for CoWoS Chiplet Interconnection Design Assisted by Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 10th Electronics System-Integration Technology Conference (ESTC), Berlin, Germany, 11–13 September 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–6.

- Kim, M.; Park, H.; Kim, S.; Son, K.; Kim, S.; Son, K.; Choi, S.; Park, G.; Kim, J. Reinforcement Learning-Based Auto-Router Considering Signal Integrity. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 29th Conference on Electrical Performance of Electronic Packaging and Systems (EPEPS), San Jose, CA, USA, 5–7 October 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- John, W.; Ecik, E.; Modayil, P.V.; Withöft, J.; Shoaee, N.G.; Brüning, R.; Götze, J. AI-Based Hybrid Approach (RL/GA) Used for Calculating the Characteristic Parameters of a Single Surface Microstrip Transmission Line. In Proceedings of the 2025 Asia-Pacific International Symposium and Exhibition on Electromagnetic Compatibility (APEMC), Taipei, Taiwan, 19–23 May 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Wei, L.; Yang, Q.; Wu, J.; Xing, L.; Chen, Y. RL-GA: A Reinforcement Learning-Based Genetic Algorithm for Electromagnetic Detection Satellite Scheduling Problem. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 77, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasunaga, M.; Matsuoka, S.; Hoshinor, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Odaira, T. AI-Based Design Methodology for High-Speed Transmission Line in PCB. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE CPMT Symposium Japan (ICSJ), 18–20 November 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Vassallo, L.; Bajada, J. Learning Circuit Placement Techniques Through Reinforcement Learning with Adaptive Rewards. In Proceedings of the 2024 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), Valencia, Spain, 25–27 March 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Jia, B.; Xu, N.; Zhao, N. Reinforcement Learning-Based Placement Method for Printed Circuit Board. In Proceedings of the 2024 13th International Conference on Communications, Circuits and Systems (ICCCAS), Xiamen, China, 10–12 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ooi, K.S.; Kong, C.L.; Goay, C.H.; Ahmad, N.S.; Goh, P. Crosstalk Modeling in High-Speed Transmission Lines by Multilayer Perceptron Neural Networks. Neural Comput. Applic 2020, 32, 7311–7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Gao, W.; Tong, W. A Deep Reinforcement Learning Assisted Adaptive Genetic Algorithm for Flexible Job Shop Scheduling. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 149, 110447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaideh, M.I.; Shirvan, K. Rule-Based Reinforcement Learning Methodology to Inform Evolutionary Algorithms for Constrained Optimization of Engineering Applications. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 217, 106836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zong, Z.; Li, Y.; Jin, D. NeuroCrossover: An Intelligent Genetic Locus Selection Scheme for Genetic Algorithm Using Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 146, 110680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zou, X.; Yao, B.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, X.; Ba, M. Dynamic Sequence Planning of Human-Robot Collaborative Assembly Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning and Genetic Algorithm. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S. Signal Integrity Analysis and Optimization Design of Transmission Lines and vias in High-Speed PCB. Master’s Thesis, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Component | Symbol | Parameter | Value/Range | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V | Excitation | Type/Amplitude/Freq. | AC 1 V, 200–800 MHz | Fixed |

| R1 | Input Resistor | Resistance | 10–910 Ω (E24) | Variable |

| Rt | Termination Resistor | Resistance | 10–910 Ω (E24) | Variable |

| C1 | Capacitive Load 1 | Capacitance | 10 pF (T4-T5) | Fixed |

| C2 | Capacitive Load 2 | Capacitance | 20 pF (T8-T9) | Fixed |

| T1–T10 | Transmission Lines | Z0,i | {47.4, 42.7, 37.2, 30.7, 26.2} Ω | Variable |

| Unit Delay Tdi | {146.8, 147.9, 149.3, 151.2, 152.8} ps/inch | Variable | ||

| Length li | 0.1–2.0 inches | Variable | ||

| Constraint | Total Length | Σli | 5.0 inches | Hard |

| No. | State Dimension | Mathematical Representation | State Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normalized current segment index. | ||

| 2 | Current Total Length Ratio. | ||

| 3 | Remaining Segments Ratio. | ||

| 4 | Remaining Length Ratio. | ||

| 5 | Normalized Impedance Mean. | ||

| 6 | Normalized Impedance Standard Deviation. | ||

| 7 | Normalized Impedance Range. | ||

| 8 | Normalized Terminal Impedance. | ||

| 9 | Impedance Change Trend. | ||

| 10 | Normalized Delay Mean. | ||

| 11 | Normalized Delay Standard Deviation. | ||

| 12 | Normalized Terminal Delay. | ||

| 13 | Impedance Matching Degree. | ||

| 14 | Normalized Input Resistor R1. | ||

| 15 | Normalized Terminal Resistor Rt. | ||

| 16 | Random Noise Dimension 1. | ||

| 17 | Random Noise Dimension 2. | ||

| 18 | Random Noise Dimension 3. |

| Action Index | Characteristic Impedance Z0 (Ω) | Unit Delay Td (ps/inch) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 47.4 | 146.8 |

| 1 | 42.7 | 147.9 |

| 2 | 37.2 | 149.3 |

| 3 | 30.7 | 151.2 |

| 4 | 26.2 | 152.8 |

| Segment | Characteristic Impedance Z0 (Ω) | Unit Delay Tdunit (ps/in) | Length (in) | Segment Delay Tdactual (ps) | Line Width (mil) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30.7 | 151.2 | 0.1119 | 16.9240 | 20 |

| 2 | 30.7 | 151.2 | 0.2875 | 43.4628 | 20 |

| 3 | 26.2 | 152.8 | 0.3582 | 54.7258 | 25 |

| 4 | 37.2 | 149.3 | 0.0948 | 14.1471 | 15 |

| 5 | 26.2 | 152.8 | 0.1877 | 28.6838 | 25 |

| 6 | 26.2 | 152.8 | 0.5669 | 86.6271 | 25 |

| 7 | 47.4 | 146.8 | 0.2440 | 35.8249 | 10 |

| 8 | 42.7 | 147.9 | 0.7670 | 113.4457 | 12 |

| 9 | 47.4 | 146.8 | 1.3603 | 199.6870 | 10 |

| 10 | 26.2 | 152.8 | 1.0217 | 156.1169 | 25 |

| Total | - | - | 5.0000 | 749.65 | - |

| Segment | Characteristic Impedance Z0 (Ω) | Unit Delay Tdunit (ps/inch) | Length (inch) | Segment Delay Tdactual (ps) | Line Width (mil) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37.2 | 149.3 | 0.5303 | 79.18 | 15 |

| 2 | 37.2 | 149.3 | 0.6733 | 100.53 | 15 |

| 3 | 30.7 | 151.2 | 0.5557 | 84.03 | 20 |

| 4 | 26.2 | 152.8 | 0.4621 | 70.61 | 25 |

| 5 | 26.2 | 152.8 | 0.6204 | 94.80 | 25 |

| 6 | 30.7 | 151.2 | 0.3271 | 49.45 | 20 |

| 7 | 26.2 | 152.8 | 0.4375 | 66.85 | 25 |

| 8 | 47.4 | 146.8 | 0.4626 | 67.92 | 10 |

| 9 | 47.4 | 146.8 | 0.5204 | 76.39 | 10 |

| 10 | 42.7 | 147.9 | 0.4105 | 60.72 | 12 |

| Total | - | - | 5.0000 | 749.48 | - |

| Optimization Algorithm | Fitness | S11 Parameter (dB) | S21 Parameter (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DQN-GA | −0.6297 | −22.249 | −1.100 |

| GA | −1.0289 | −10.723 | −1.246 |

| None | −6.4314 | −9.581 | −6.623 |

| Metric | DQN-GA | GA | Ratio (DQN-GA/GA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total computation time (hours) | 3.5 | 0.8 | 4.38 |

| Fitness improvement (%) | 90.2 | 78.0 | 1.156 |

| Time per iteration (seconds) | 42 | 48 | 0.875 |

| Time per 1% improvement (minutes) | 2.33 | 0.615 | 3.79 |

| Memory usage (GB) | 4.2 | 0.8 | 5.25 |

| Cost–performance ratio * | - | - | 0.305 |

| Design Type | S11 Parameter (dB) | S21 Parameter (dB) |

|---|---|---|

| DQN-GA optimized | −12.089 | −6.594 |

| GA optimized | −11.696 | −6.625 |

| Unoptimized | −11.037 | −7.978 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Hu, C.; Feng, K.; Ge, S.; Li, J. Optimization of High-Frequency Transmission Line Reflection Wave Compensation and Impedance Matching Based on a DQN-GA Hybrid Algorithm. Electronics 2026, 15, 645. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030645

Liu T, Li J, Zhang X, Zhang D, Hu C, Feng K, Ge S, Li J. Optimization of High-Frequency Transmission Line Reflection Wave Compensation and Impedance Matching Based on a DQN-GA Hybrid Algorithm. Electronics. 2026; 15(3):645. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030645

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Tieli, Jie Li, Xi Zhang, Debiao Zhang, Chenjun Hu, Kaiqiang Feng, Shuangchao Ge, and Junlong Li. 2026. "Optimization of High-Frequency Transmission Line Reflection Wave Compensation and Impedance Matching Based on a DQN-GA Hybrid Algorithm" Electronics 15, no. 3: 645. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030645

APA StyleLiu, T., Li, J., Zhang, X., Zhang, D., Hu, C., Feng, K., Ge, S., & Li, J. (2026). Optimization of High-Frequency Transmission Line Reflection Wave Compensation and Impedance Matching Based on a DQN-GA Hybrid Algorithm. Electronics, 15(3), 645. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030645