A Novel Intersection-Statistics-Based Indoor TOA Localization Algorithm with Adaptive Error Correction for NLOS Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

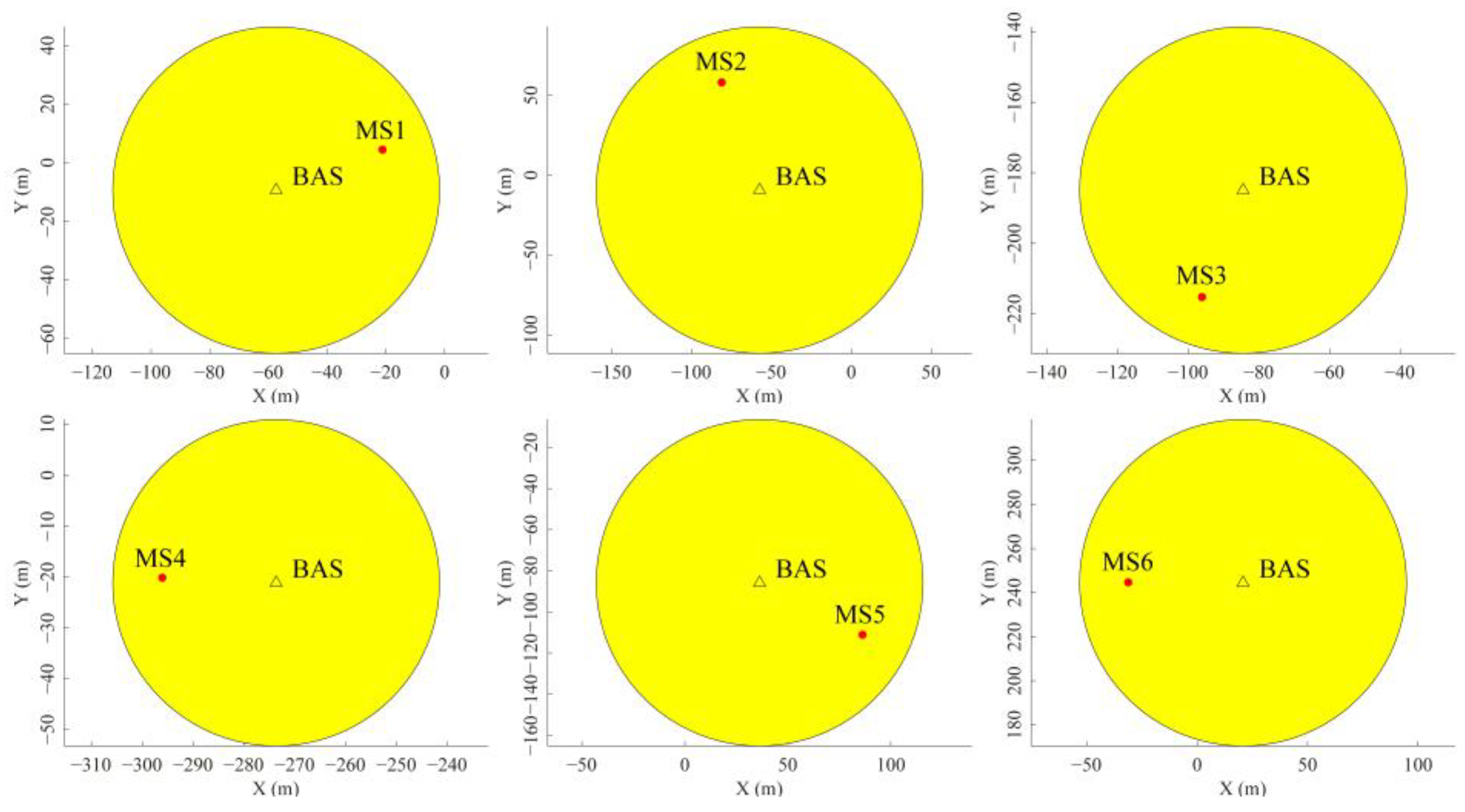

2. Indoor Localization Environment and Experimental Data

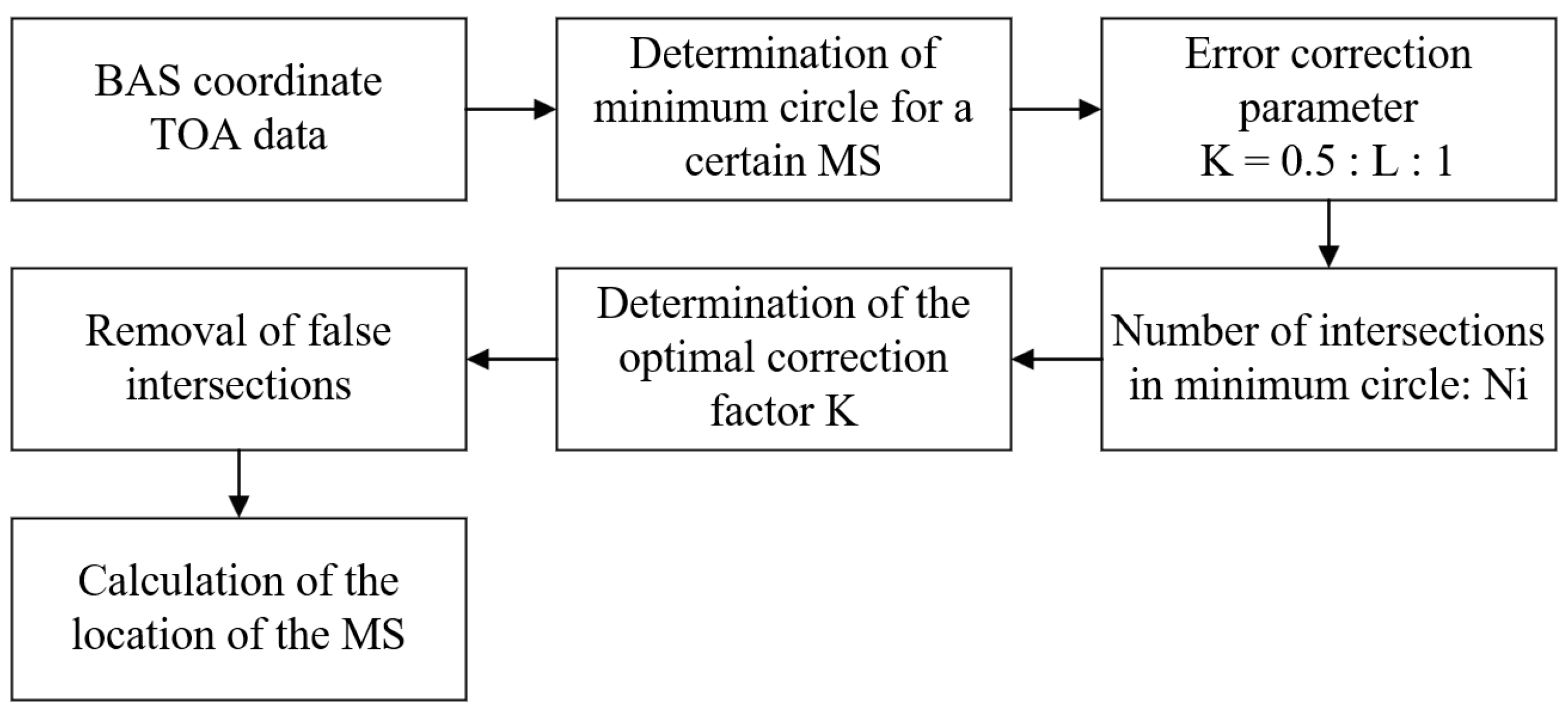

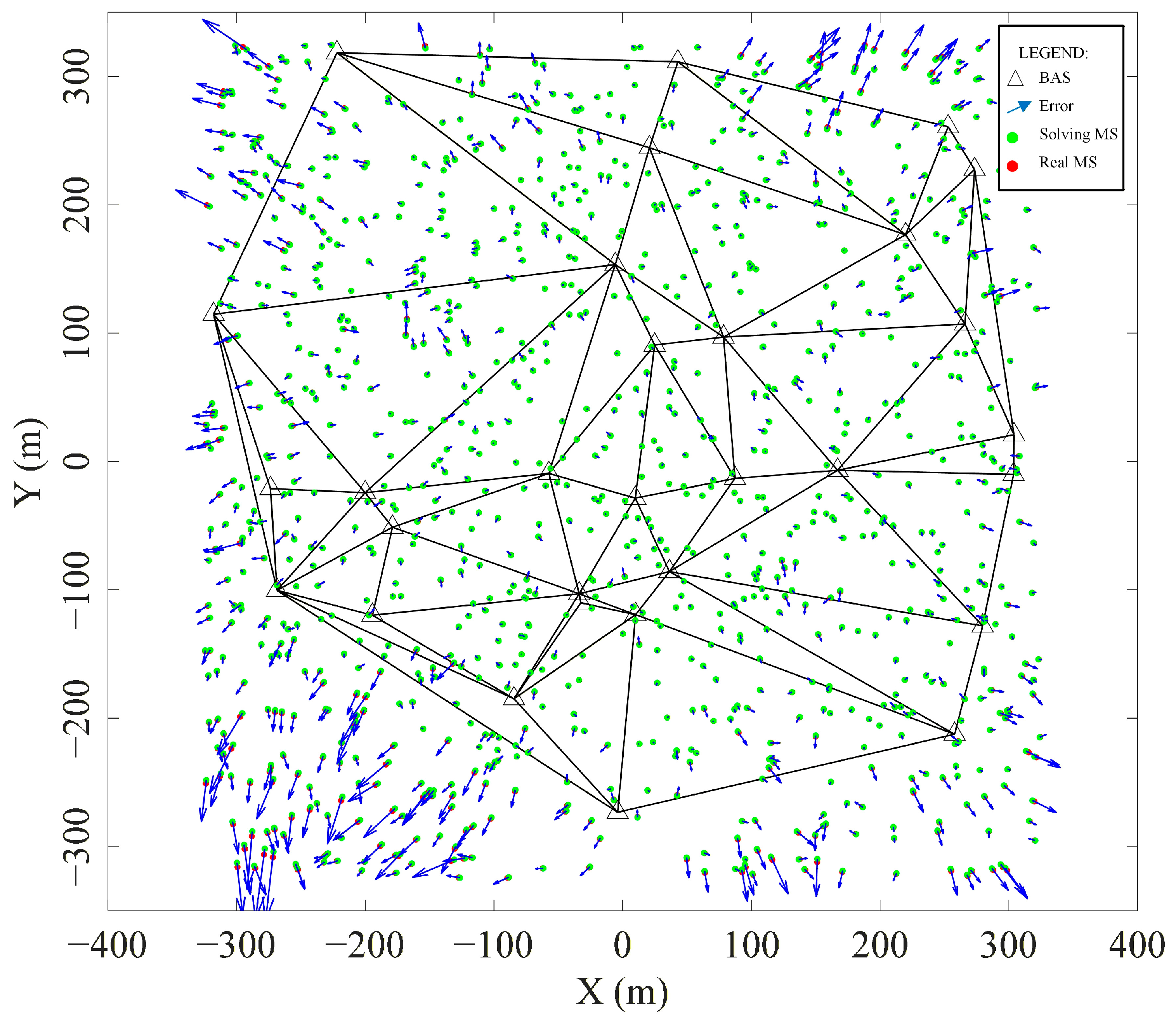

3. Indoor Time-of-Arrival Localization Algorithm Based on Statistics

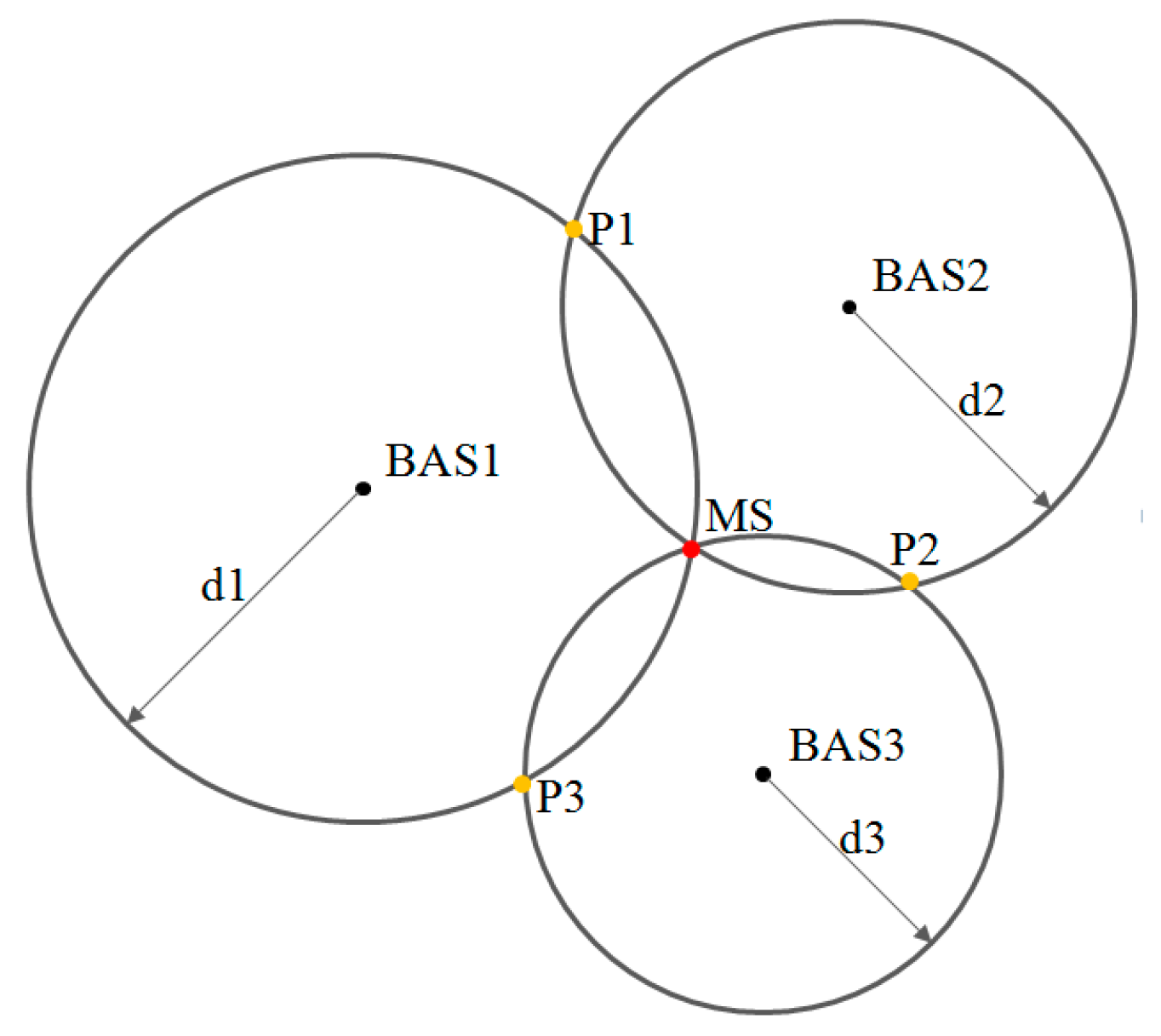

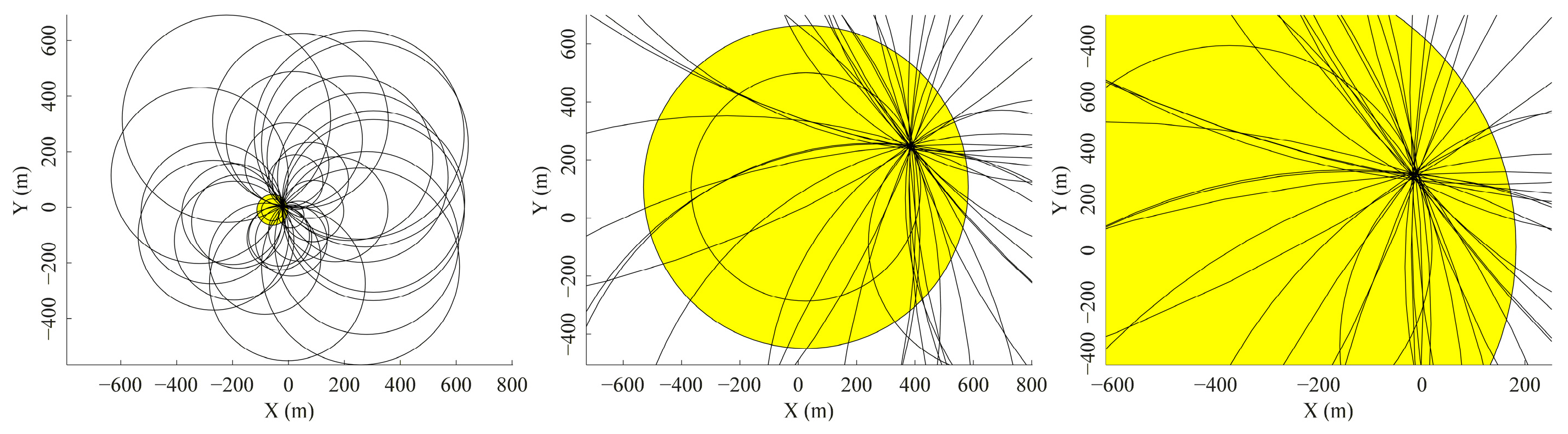

3.1. The Principle of Minimum Circle

3.2. Indoor Time-of-Arrival Localization Algorithm and Model

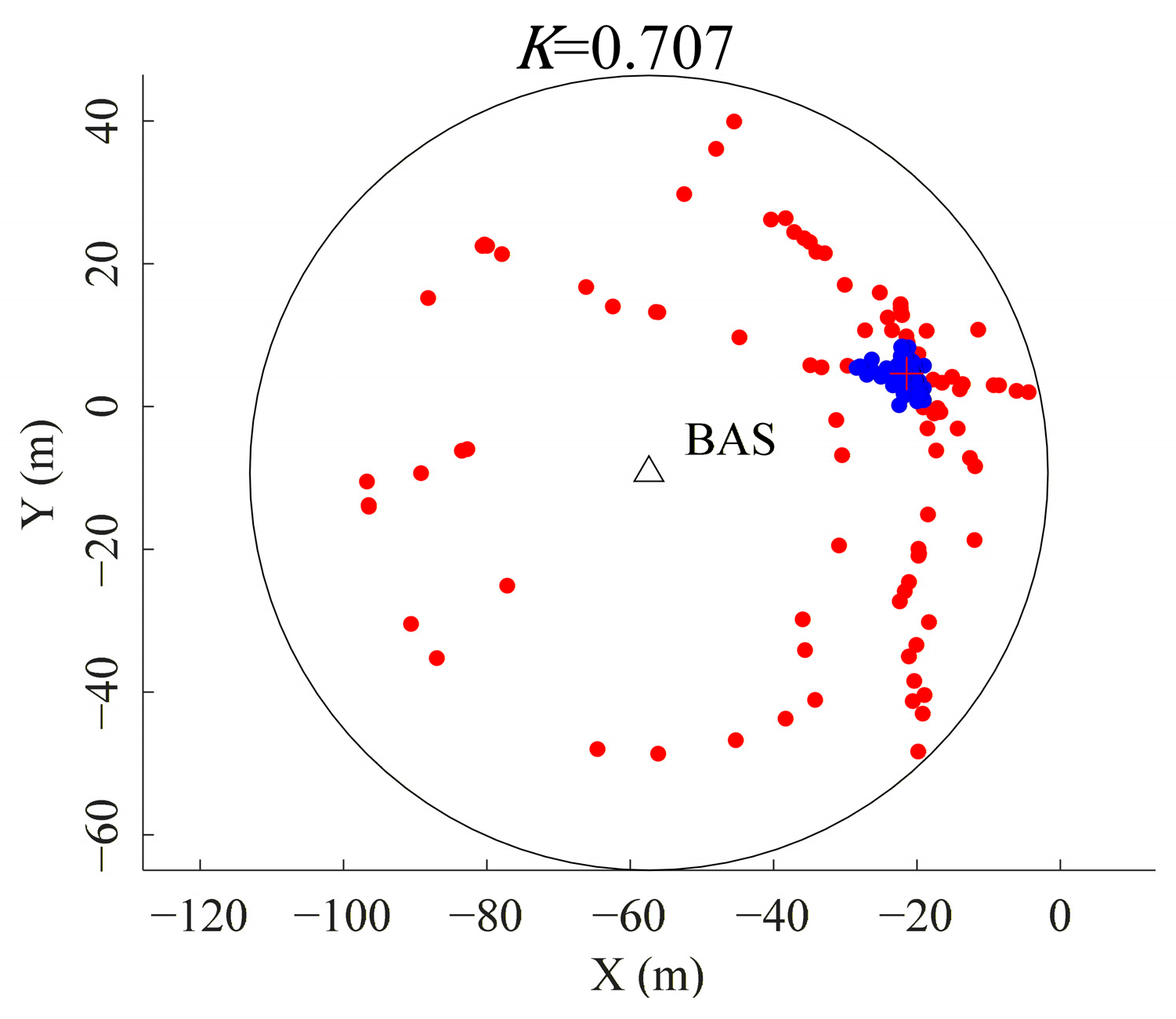

3.3. Calculation of Mobile Station Coordinate

- (1)

- Calculate the centroid coordinate of the intersection set ;

- (2)

- Calculate the distance from each point in the intersection set to the centroid, eliminate the intersections whose distance is greater than the mean of , and obtain the intersection set .

- (3)

- Calculate the mean and standard deviation of the corresponding distance of the intersection set , eliminate the intersections whose distance is greater than , and obtain the intersection set .

- (4)

- The coordinates of each point in the intersection set are , and the MS coordinate is calculated as follows:

3.4. Time Complexity Analysis

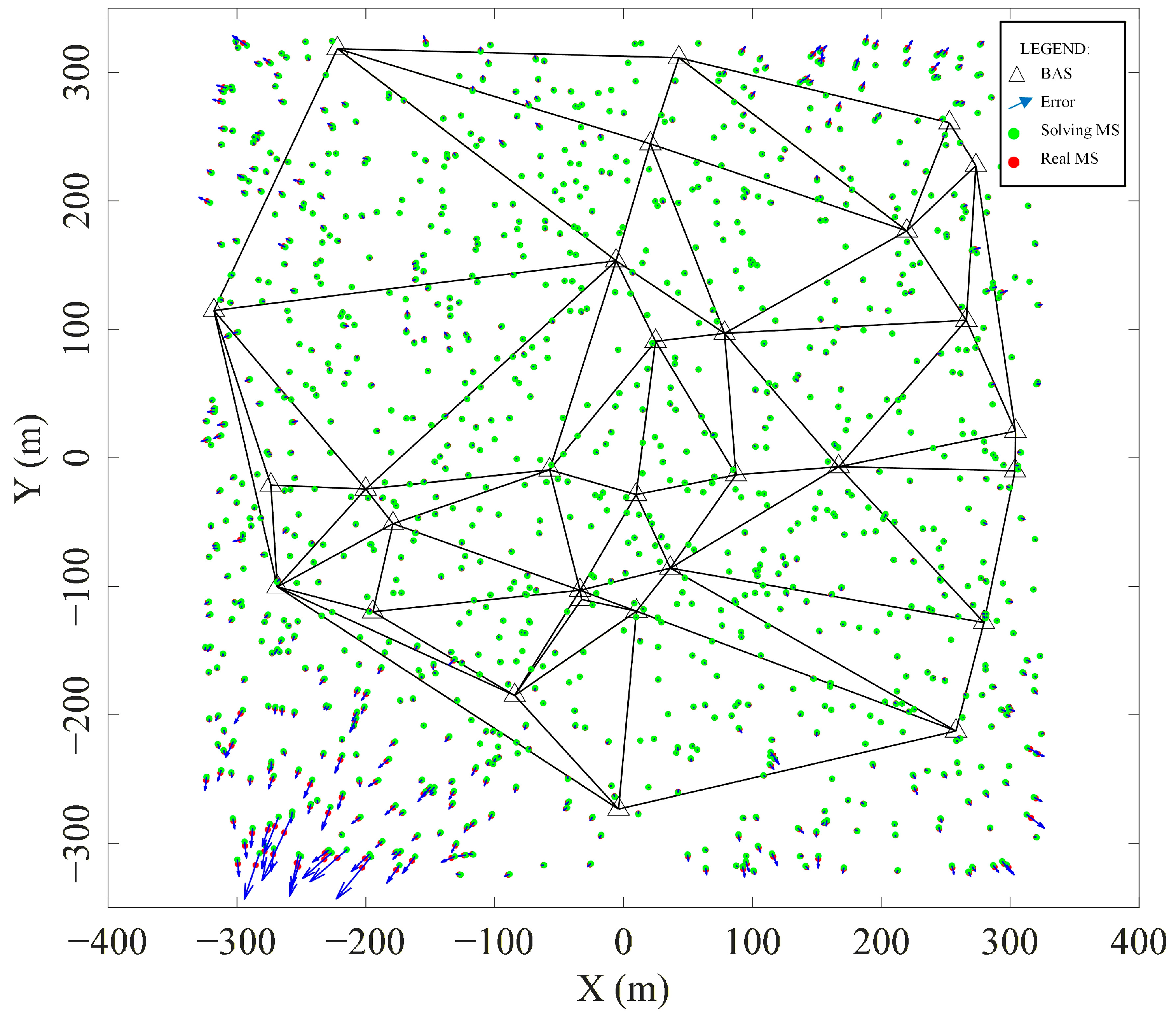

4. Experimental Analysis

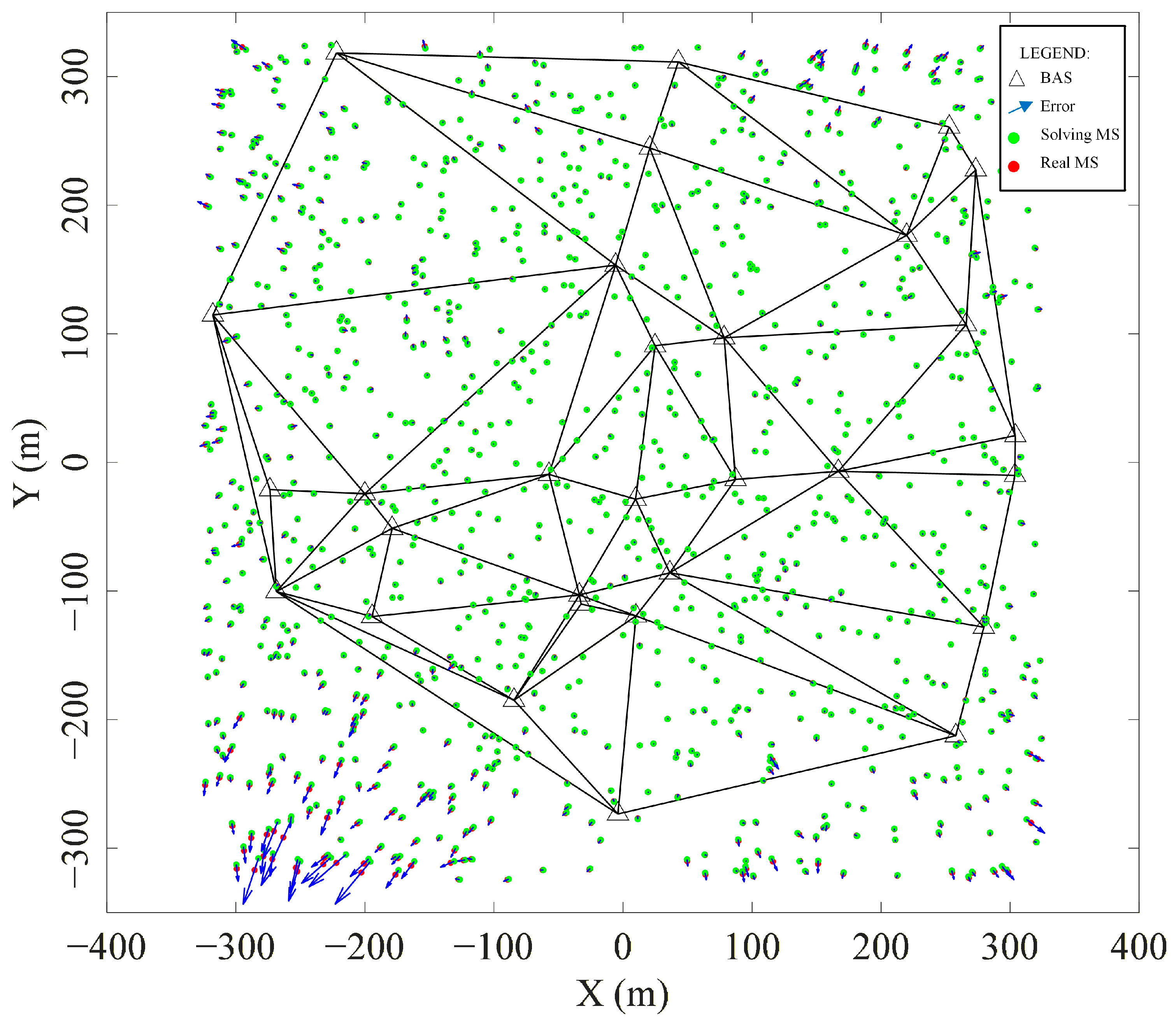

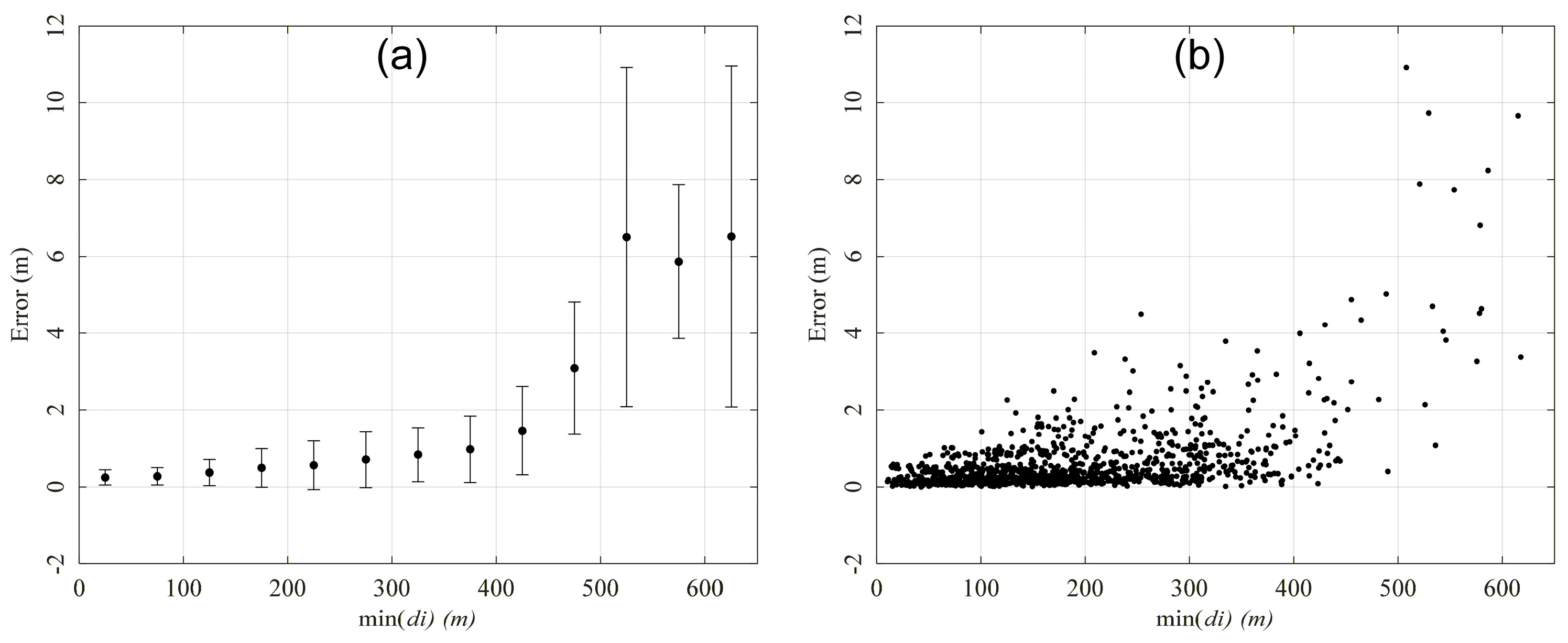

4.1. Analysis of Localization Error

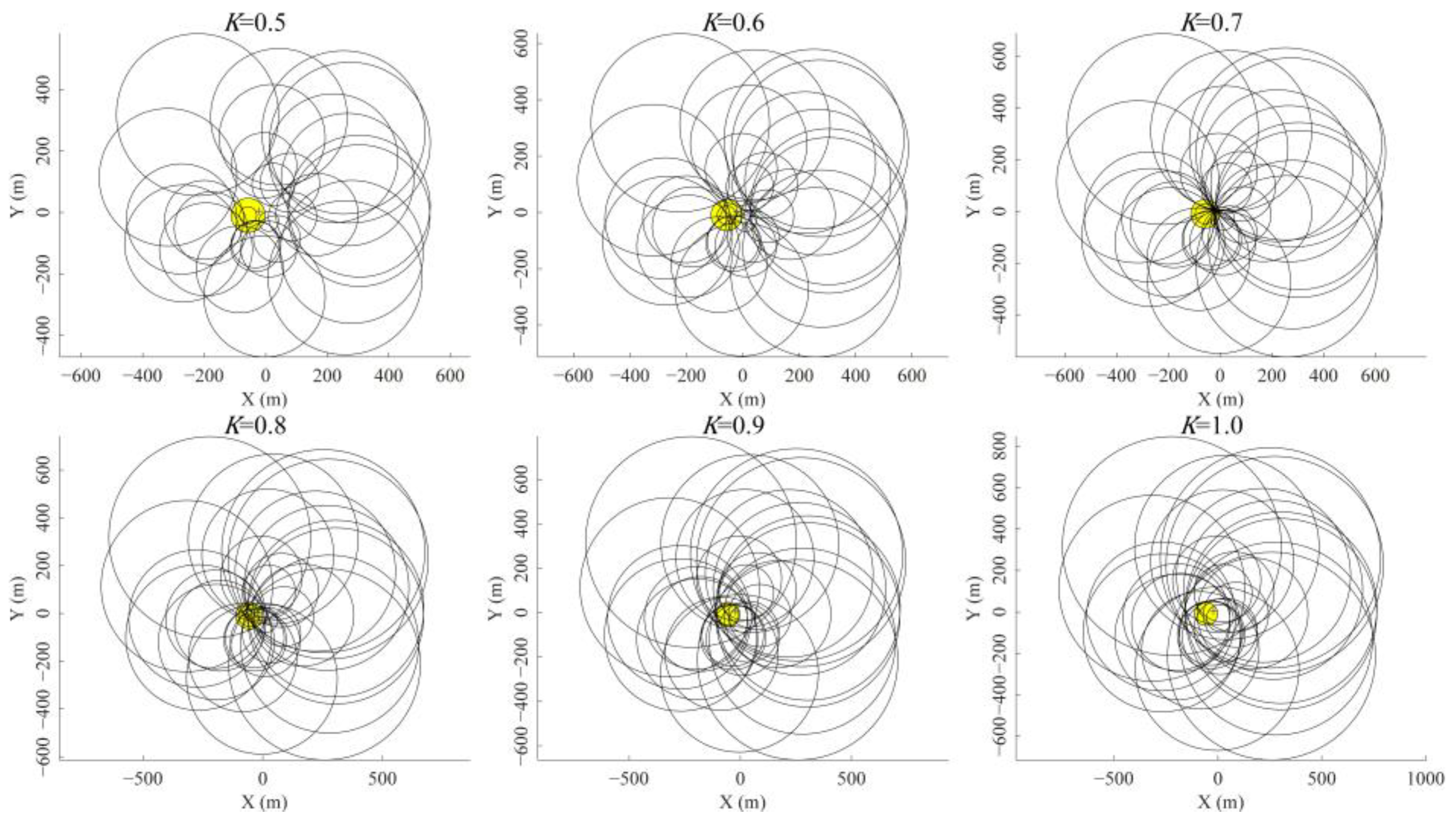

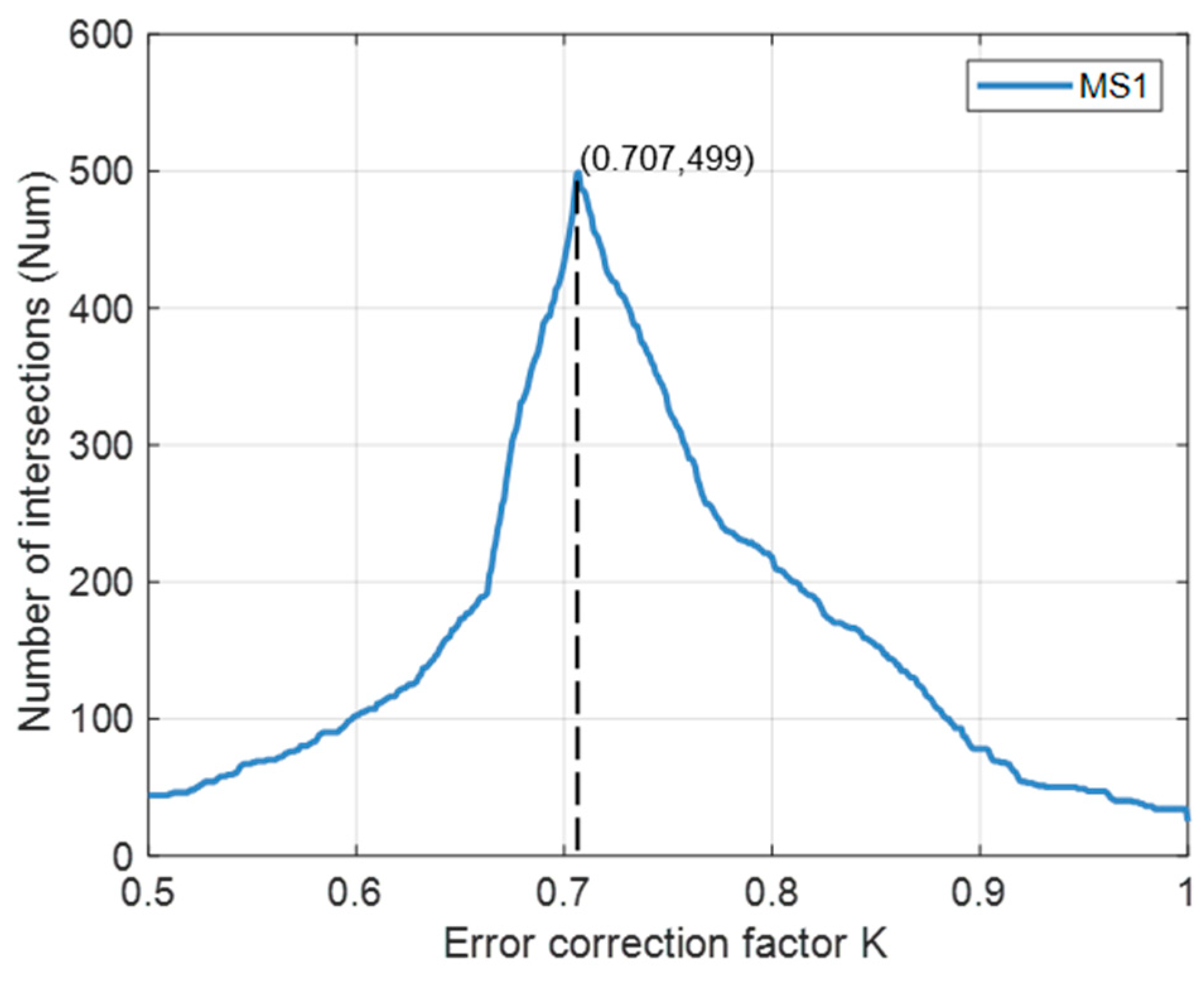

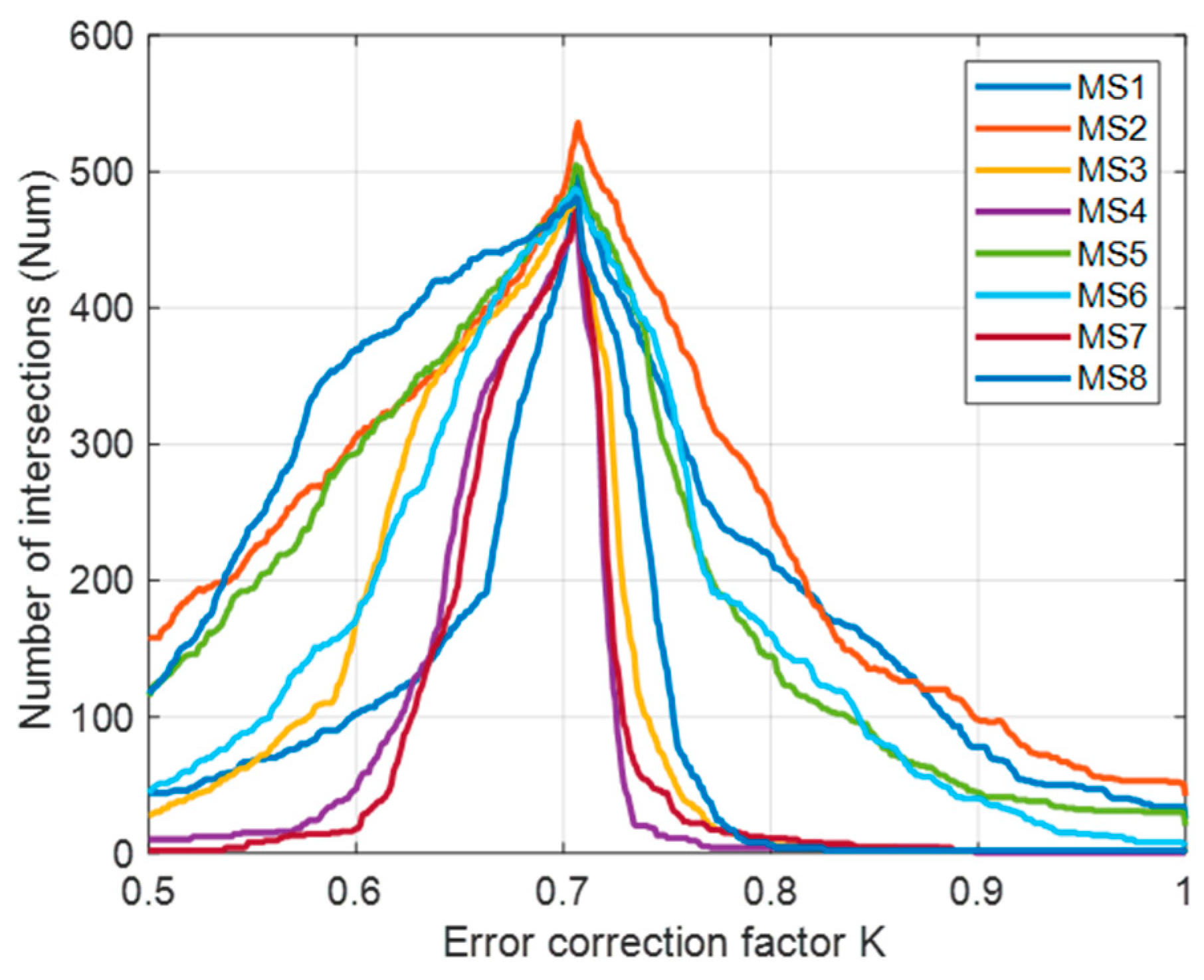

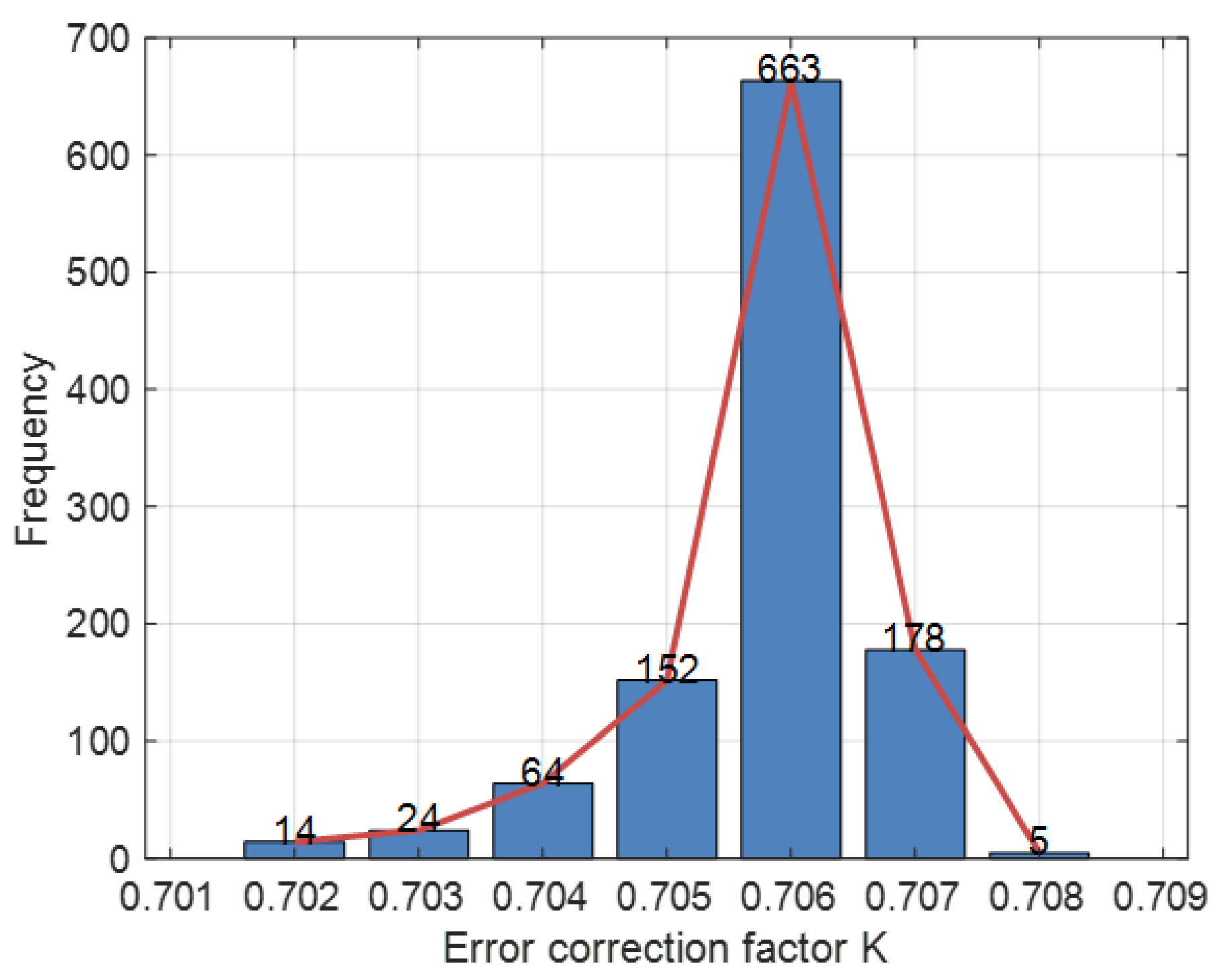

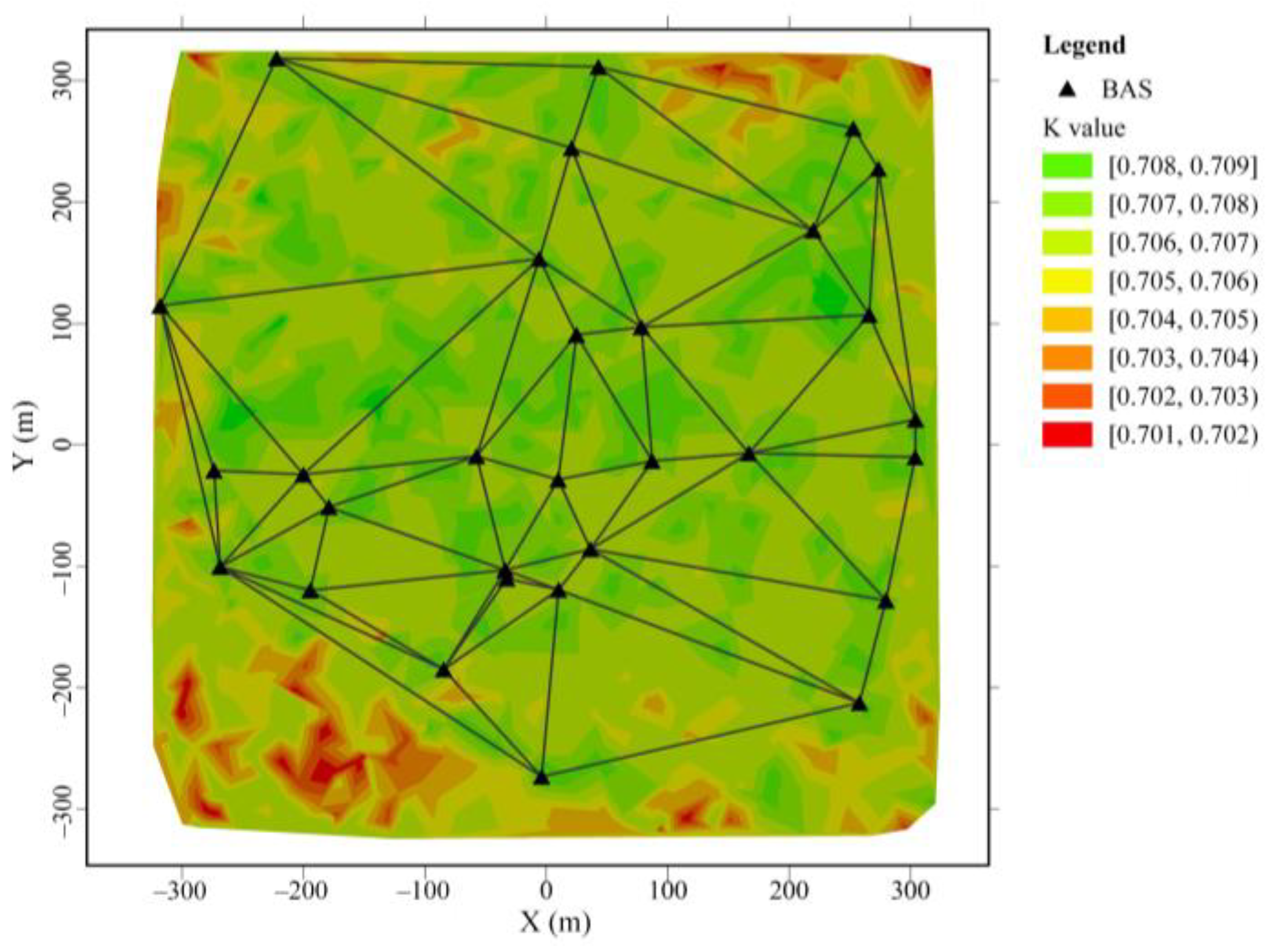

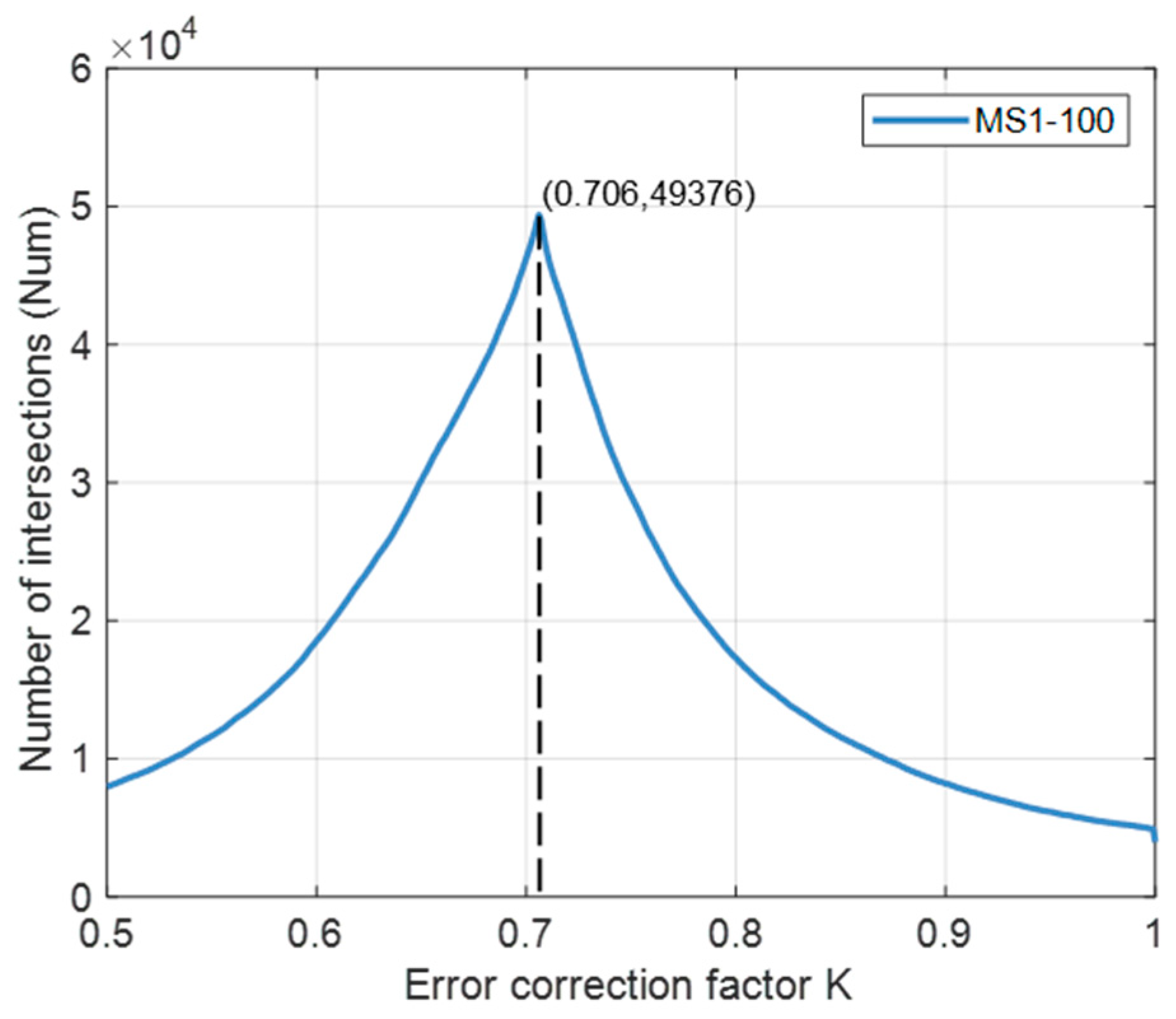

4.2. Analysis of Value Changes in the Same BAS Localization Environment

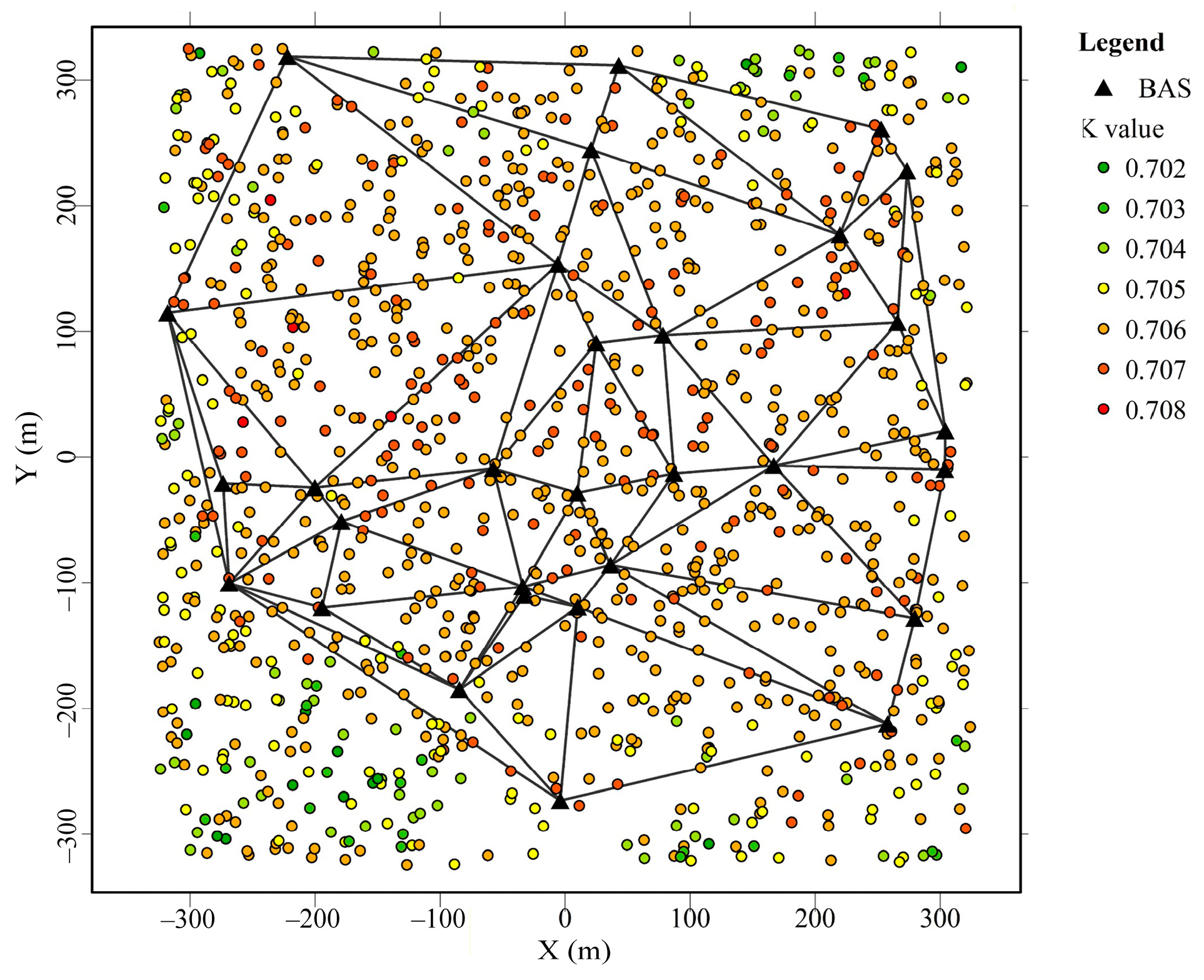

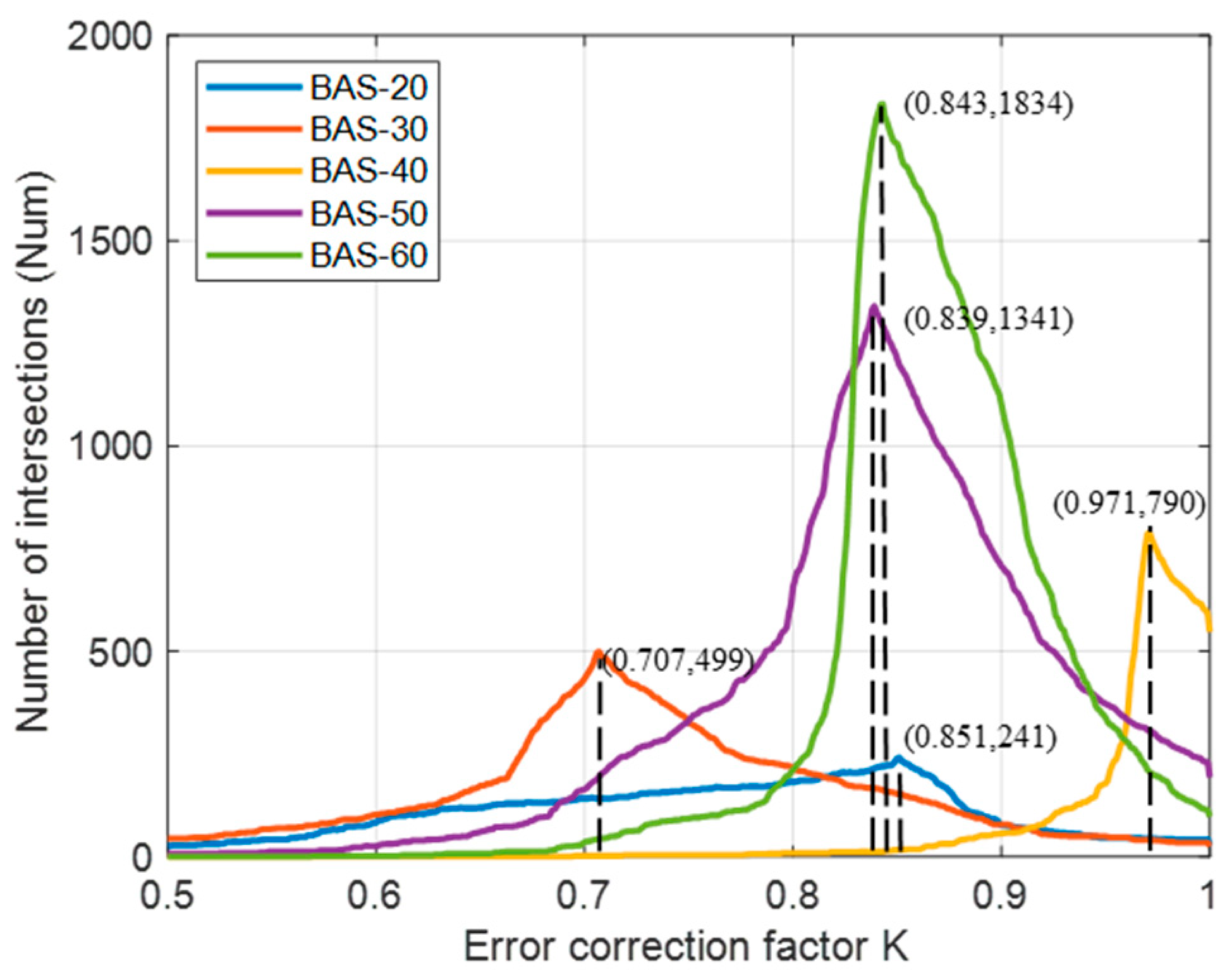

4.3. Analysis of Value Changes in the Different BAS Localization Environments

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NLOS | Non-line of sight |

| LOS | Line of sight |

| LS | Least squares |

| WLS | Weighted least squares |

| BAS | Base station |

| MS | Mobile station |

| TOA | Time of arrival |

| TDOA | Time difference of arrival |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| LPWAN | Low-Power Wide-Area Network |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LoRa | Long Range |

| Wi-Fi | Wireless Fidelity |

| AOA | Angle of arrival |

| RSSI | Received signal strength indication |

| LBS | Location-Based Service |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| REC | Ranging error classification |

| LSTM | Long-short term memory |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| WLANs | Wireless local area networks |

References

- Xia, L.; Lu, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Augmented reality and indoor positioning based mobile production monitoring system to support workers with human-in-the-loop. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 86, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Chen, J.; Tang, H.; Zhang, H. RSSI-based location fingerprint method for RFID indoor positioning: A review. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2024, 39, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, H.; Shuaieb, W.; Obeidat, O.; Abd-Alhameed, R. A review of indoor localization techniques and wireless technologies. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 119, 289–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, S.; Beko, M. Target Localization via Integrated and Segregated Ranging Based on RSS and TOA Measurements. Sensors 2019, 19, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubry, A.; Babu, P.; De Maio, A.; Fatima, G.; Sahu, N. A robust framework to design optimal sensor locations for TOA or RSS source localization techniques. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2023, 71, 1293–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffery, J.; Stuber, G. Overview of Radiolocation in CDMA Cellular Systems. IEEE Commun. Mag. 1998, 36, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Moon, N. Random forest and WiFi fingerprint-based indoor location recognition system using smart watch. Hum.-Centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 2019, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, X. Unscented Kalman Filter Algorithm for WiFi-PDR Integrated Indoor Positioning. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2015, 44, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Bi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, G.; Feng, Y.; Si, M. LOS compensation and trusted NLOS recognition assisted WiFi RTT indoor positioning algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 243, 122867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurdi, R.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ng, B.L.; Dawar, N.; Zhang, C.; Han, J.K.H. WhereArtThou: A WiFi-RTT-based indoor positioning system. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 41084–41101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Ciravegna, F.; Bond, R.; Mulvenna, M. A low-cost indoor positioning system using bluetooth low energy. IEEE Access 2024, 8, 136858–136871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Yang, A.; Fen, L.; QI, X. Review on indoor positioning technology based on visible light communications. J. Nanjing Univ. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2017, 9, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaens, S.; Alijani, M.; Joseph, W.; Plets, D. Visible light positioning as a next-generation indoor positioning technology: A tutorial. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 26, 2867–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, J.; Ahn, C.; Shi, P.; Shmaliy, Y.; Lim, M. Distributed Hybrid Particle/FIR Filtering for Mitigating NLOS Effects in TOA-Based Localization Using Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 5182–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, H.; Mei, Z.; Xu, X.; He, Q. Ultra-wideband high accuracy distance measurement based on hybrid compensation of temperature and distance error. Measurement 2023, 206, 112276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, R.; Flores, J.; Olivera, R.; Perez, J.; Munoz, J. Heuristic Approach to Indoor Localization Using LoRa RSSI Measurements. Radioengineering 2025, 34, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simka, M.; Polak, L. On the RSSI-based Indoor Localization Employing LoRa in the 2.4 GHz ISM Band. Radioengineering 2022, 31, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleny, O.; Fryza, T.; Bravenec, T.; Azizi, S.; Nair, G. Detection of Room Occupancy in Smart Buildings. Radioengineering 2024, 33, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.A.; Saeed, N. Hybrid TOA/AOA localization for indoor multipath-assisted next-generation wireless networks. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Su, S.; Zuo, Z.; Guo, X.; Sun, B.; Wen, X. Time Difference of Arrival (TDoA) Localization Combining Weighted Least Squares Firefly Algorithm. Sensors 2019, 19, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Xu, X.; Zhang, T. Robust Time-Difference-of-Arrival (TDOA) Localization Using Weighted Least Squares with Cone Tangent Plane Constraint. Sensors 2018, 18, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottigliero, S.; Milanesio, D.; Saccani, M.; Maggiora, R. A low-cost indoor real-time locating system based on TDOA estimation of UWB pulse sequences. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 5502211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Three-Dimensional Localization of Heterogeneous Underwater Networks Using Hybrid TOA-AOA Measurements Under Random DoS Attack. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 22257–22266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, S.; Beko, M.; Dinis, R.; Montezuma, P. Estimating Directional Data From Network Topology for Improving Tracking Performance. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2019, 8, 2224–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Fu, J. Study on PDR and RSSI Based Indoor Localization Algorithm. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2015, 36, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Pascacio, P.; Casteleyn, S.; Torres-Sospedra, J.; Lohan, E.S.; Nurmi, J. Collaborative indoor positioning systems: A systematic review. Sensors 2021, 21, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Low-Cost 3D Bluetooth Indoor Positioning with Least Square. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2014, 78, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, F.; Wang, P.; Hu, J. A Weighted TOA Indoor Localization Algorithm for Underground Space. Ind. Control. Comput. 2014, 27, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Nanotron Corporation. NanoLOC development Kit 3.0 factsheet. 2007. Available online: https://nanotron.com/assets/pdf/products/Factsheet_nanoLOC-Dev-Kit.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- Lin, Y.; Yu, K.; Zhu, F.; Bu, J.; Dua, X. The state of the art of deep learning-based Wi-Fi indoor positioning: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 27076–27098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.; Nguyen, M.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y. NLOS Identification in WLANs Using Deep LSTM with CNN Features. Sensors 2018, 18, 4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; He, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, B.; Yu, Y. Ranging error classification based indoor TOA localization algorithm. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2011, 32, 2851–2856. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, S.; Xu, K.; Huang, D. Neural Network Localization with TOA Measurements Based on Error Learning and Matching. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 19089–19099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Chen, D. A TOA Positioning Algorithm Based on Least Square Method and BP Neural Network. Comput. Technol. Dev. 2018, 28, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

| (a) | ||||||

| MS | BAS1 | BAS2 | BAS3 | … | BAS29 | BAS30 |

| 1 | 1.20 × 10−6 | 5.21 × 10−7 | 2.16 × 10−7 | … | 1.54 × 10−6 | 1.54 × 10−6 |

| 2 | 9.85 × 10−7 | 8.63 × 10−7 | 5.94 × 10−7 | … | 1.84 × 10−6 | 1.83 × 10−6 |

| 3 | 1.24 × 10−6 | 1.29 × 10−6 | 1.01 × 10−6 | … | 2.12 × 10−6 | 2.19 × 10−6 |

| 4 | 1.07 × 10−7 | 1.81 × 10−6 | 1.45 × 10−6 | … | 2.83 × 10−6 | 2.84 × 10−6 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | |

| 1098 | 7.40 × 10−7 | 1.03 × 10−6 | 6.98 × 10−7 | … | 2.03 × 10−6 | 2.03 × 10−6 |

| 1099 | 2.18 × 10−6 | 9.09 × 10−7 | 1.04 × 10−6 | … | 1.11 × 10−6 | 1.23 × 10−6 |

| 1100 | 1.47 × 10−6 | 1.85 × 10−6 | 1.58 × 10−6 | … | 2.63 × 10−6 | 2.72 × 10−6 |

| (b) | ||||||

| ID | X | Y | ID | X | Y | |

| 1 | −273.67 | −21.14 | 1 | −21.19 | 4.48 | |

| 2 | 87.23 | −13.20 | 2 | −81.14 | 58.24 | |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | |

| 30 | 304.04 | 20.83 | 1100 | −164.27 | −313.63 | |

| Inside and Outside BAS Network | Inside BAS Network | Outside BAS Network | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average error/m | 0.416 | 0.297 | 0.587 |

| Maximum error/m | 7.187 | 1.301 | 7.187 |

| Minimum error/m | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.163 |

| Variance/m2 | 0.253 | 0.147 | 0.302 |

| Algorithm | Proposed Algorithm | LS | Nano |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average error/m | 0.416 | 4.991 | 0.642 |

| Maximum error/m | 7.187 | 37.514 | 7.071 |

| Variance/m2 | 0.369 | 5.557 | 1.107 |

| Inside and Outside BAS Network | Inside BAS Network | Outside BAS Network | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average error/m | 0.547 | 0.298 | 0.911 |

| Maximum error/m | 7.791 | 2.361 | 7.791 |

| Minimum error/m | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.063 |

| Variance/m2 | 0.596 | 0.258 | 0.844 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, P.; Ding, L.; Lu, Y.; Shang, L.; Wei, M.; Xie, M.; Li, H. A Novel Intersection-Statistics-Based Indoor TOA Localization Algorithm with Adaptive Error Correction for NLOS Environments. Electronics 2026, 15, 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030639

Wang Z, Zhang C, Zhao P, Ding L, Lu Y, Shang L, Wei M, Xie M, Li H. A Novel Intersection-Statistics-Based Indoor TOA Localization Algorithm with Adaptive Error Correction for NLOS Environments. Electronics. 2026; 15(3):639. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030639

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhaohui, Chengchun Zhang, Peng Zhao, Liangkui Ding, Yanmei Lu, Longhua Shang, Mingyang Wei, Mingming Xie, and Hongwei Li. 2026. "A Novel Intersection-Statistics-Based Indoor TOA Localization Algorithm with Adaptive Error Correction for NLOS Environments" Electronics 15, no. 3: 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030639

APA StyleWang, Z., Zhang, C., Zhao, P., Ding, L., Lu, Y., Shang, L., Wei, M., Xie, M., & Li, H. (2026). A Novel Intersection-Statistics-Based Indoor TOA Localization Algorithm with Adaptive Error Correction for NLOS Environments. Electronics, 15(3), 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030639