5.1. Experimental Design

5.1.1. Experimental Scenario

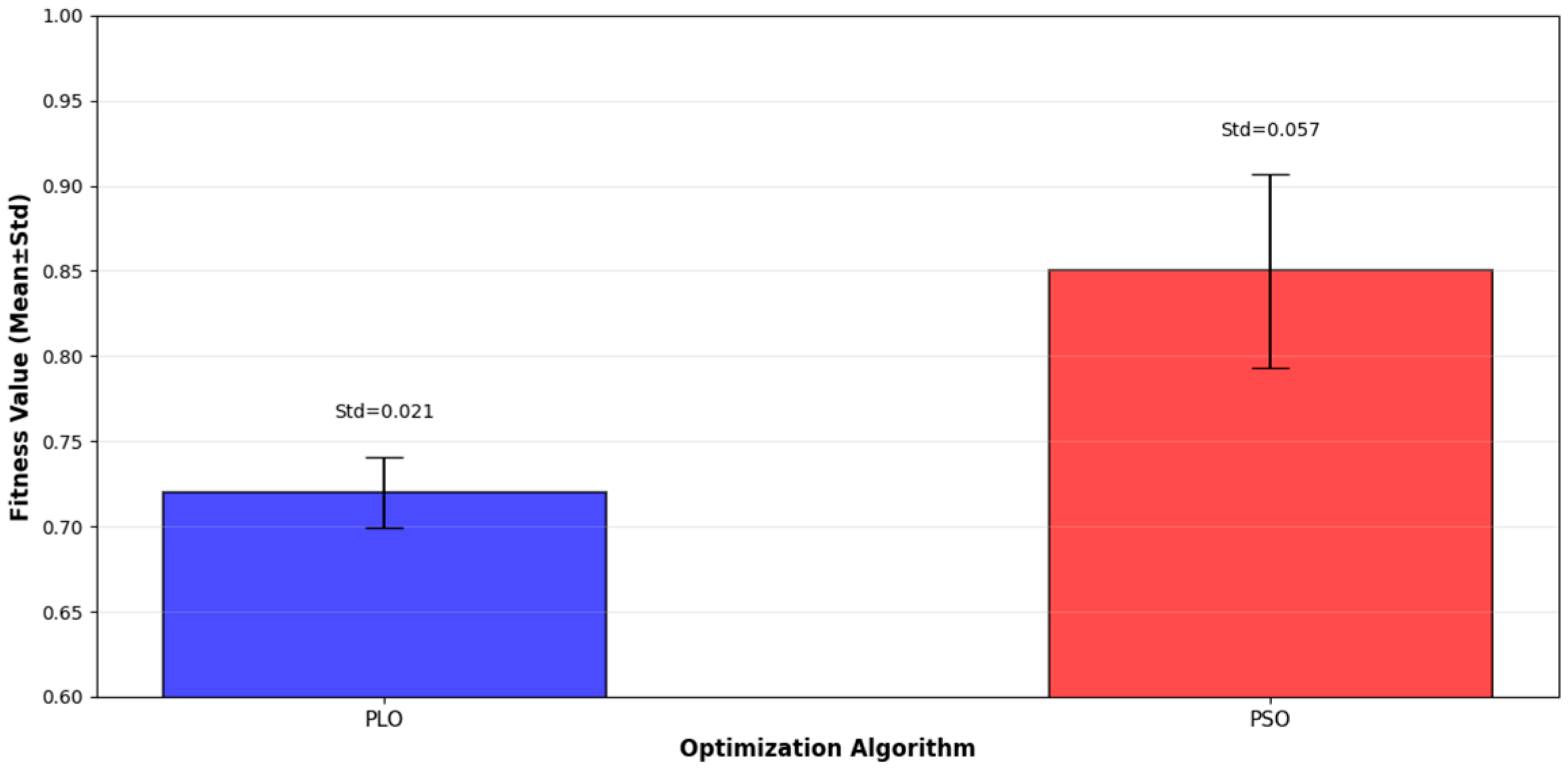

The experiment uses the complex maneuvering processes of three aerial targets (A, B, C) as the test scenario and constructs a high-fidelity, reproducible distributed simulation verification environment to support the training and evaluation of the DR model. On this basis, target A is selected as the typical validation subject, and a specific scenario covering the entire process of extreme maneuvering–normal cruise-cooperative avoidance is designed (

Figure 7).

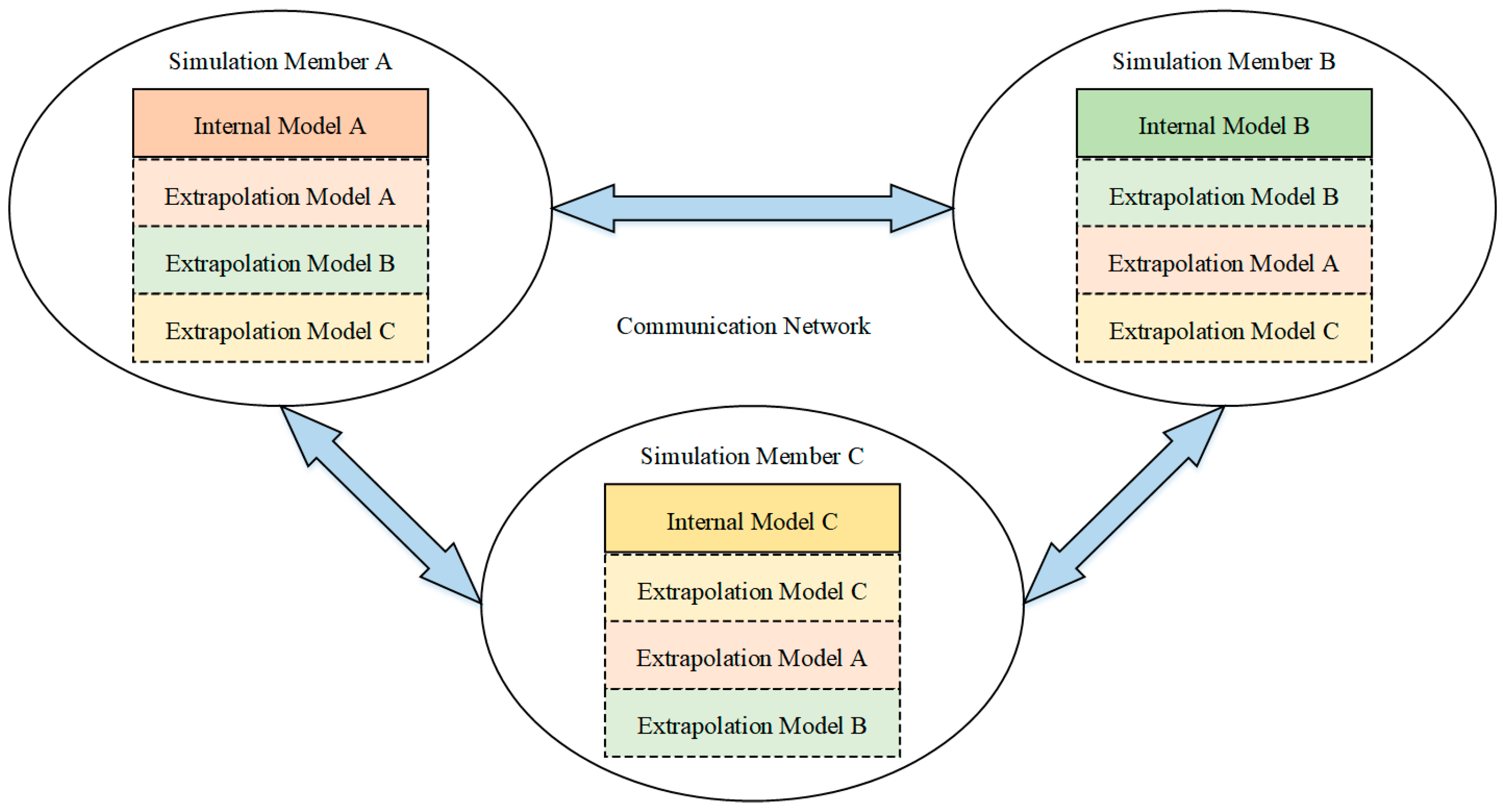

(1) Extreme large-angle climb/dive: Simulating the strong nonlinear maneuver process of the short-distance penetration of flight targets, large-angle attitude adjustment and high-overload vertical acceleration were set to focus on testing the model’s adaptability to dynamic mutation scenarios. The parameter design is as follows: The displacement in the X direction ranges from 0 to 10,000 m, there is no lateral offset in the Y direction (fixed at 0), and the Z direction completes a climb from 0 to 6000 m altitude, followed by a dive to 3000 m; the corresponding average climb angle is approximately 50°, the average dive angle is approximately 45°, and the vertical acceleration is controlled at ±5~6 G. This scenario focuses on verifying the model’s adaptability to dynamic mutation scenarios.

(2) Conventional small-angle cruising: Simulating the stable movement process of the long-distance cruising of flight targets, the small-amplitude lateral offset and altitude elevation were set to focus on verifying the model’s ability to suppress error accumulation under long-time sequence operating conditions. The parameter design is as follows: the displacement in the X direction ranges from 10,000 m to 30,000 m, the Y direction gently offsets from 0 to 600 m, and the Z direction slightly rises from 3000 m to 3200 m; the turning angle is approximately 3°, and the cruising speed remains stable. This scenario focuses on verifying the model’s ability to control the error accumulation effect under conventional operating conditions.

(3) Snake-like evasive maneuver: Simulating the multi-group S-type series maneuver process of flight targets evading interception, a time-series coupled scenario was constructed through reciprocating lateral fluctuations and vertical undulations to focus on verifying the model’s fitting accuracy of the coupled parameters and the interference elimination capability. The parameter design is as follows: The displacement in the X direction ranges from 30,000 m to 40,000 m, the Y direction fluctuates reciprocally based on 600 m (fluctuation range ±500 m), and the Z direction undulates, with 3200 m as the benchmark (fluctuation range ±500 m); the turning angle is ±25°, and a total of five groups of S-turns are distributed within a 10 km distance. This scenario focuses on verifying the model’s fitting accuracy of the time-series coupled parameters.

Furthermore, a full-process continuous composite maneuver integrating the above three types of scenarios, i.e., a complete movement link in the X direction from 0 to 40,000 m, was formed to realize the smooth switching of “climb–dive–cruise–snake-like” maneuvers, focusing on verifying the long-term prediction stability of the model employing the alternation of complex continuous operating conditions.

5.1.2. Experimental Platform Configuration

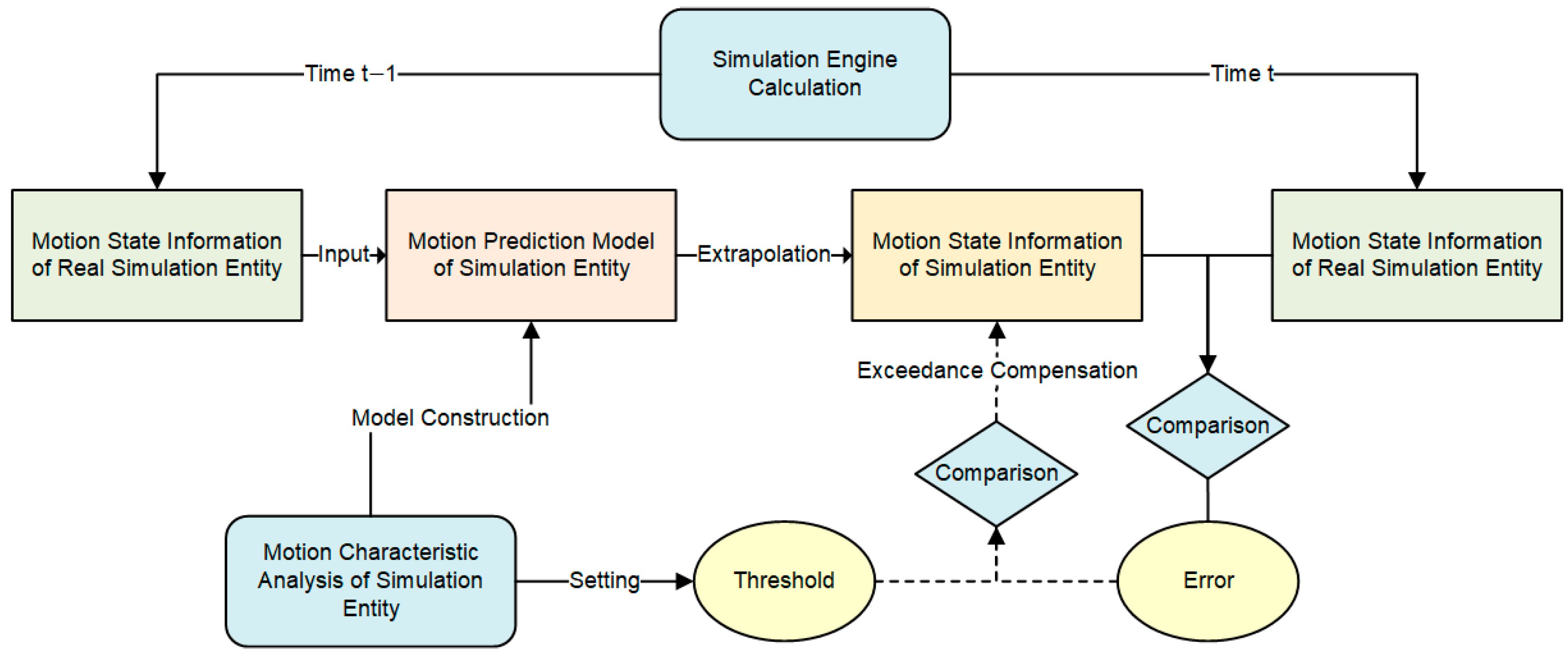

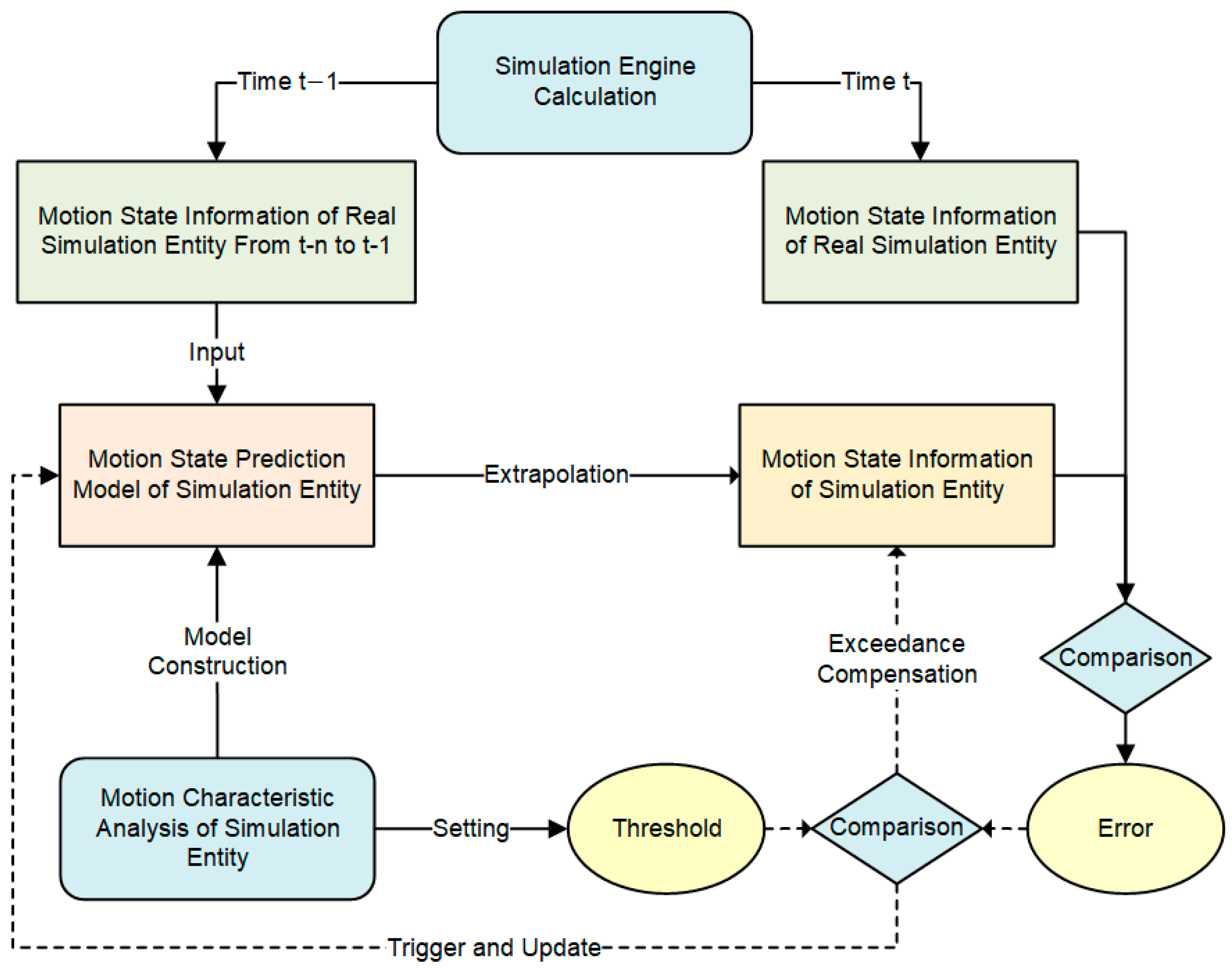

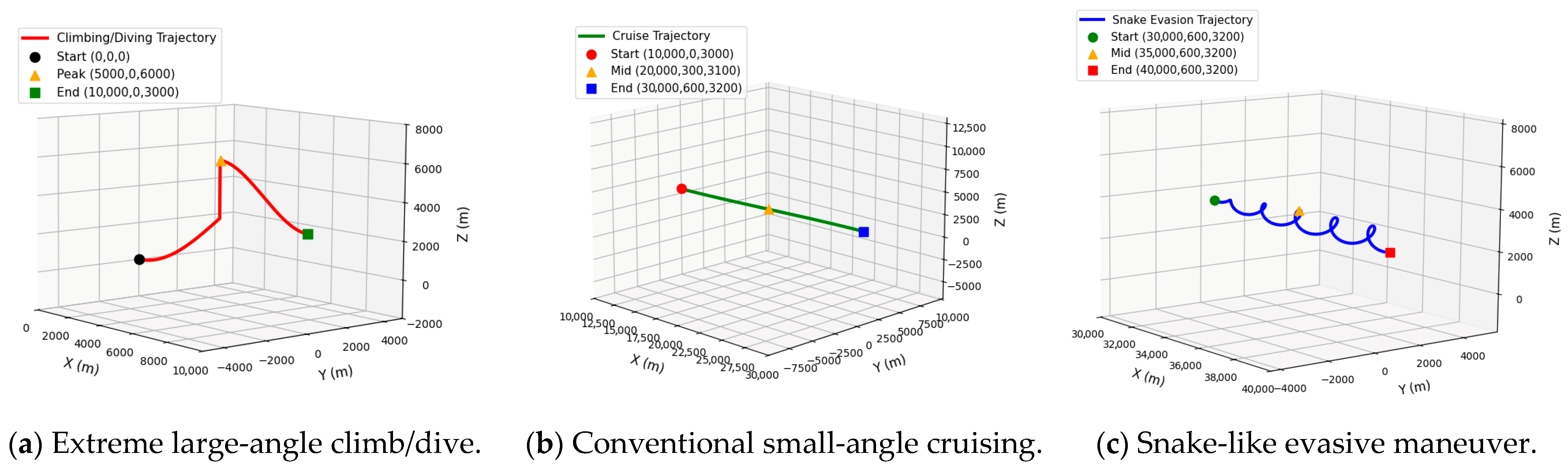

To verify the superiority of the DR algorithm based on the PLO–Transformer–LSTM model, a distributed interactive simulation experimental environment consistent with

Figure 8 was constructed. Taking simulation member A as an example, A’s internal model reflects the true motion state of target A, and A’s extrapolation model reflects the estimated state of fighter A. During the maneuver, if the state information deviation between A’s internal and A’s extrapolation is not significant, then A’s extrapolation information does not need to be updated to the true value. Only when the deviation exceeds a certain threshold will A’s extrapolation initiate an update and send the relevant information synchronously to members B and C.

The experimental platform for simulation nodes A, B, and C is uniformly configured as follows:

(1) Hardware: Intel Core i7-13700K CPU (3.4 GHz), NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB GDDR6X), 64 GB DDR5 RAM (4800 MHz).

(2) Operating System: Ubuntu 22.04 LTS (64-bit).

(3) Software: Python 3.11 (PyTorch 2.1.0, CUDA 12.1, NumPy 1.26.0, SciPy 1.11.4) for PLO–Transformer–LSTM model training and PLO optimization algorithm implementation; AFSIM v2.9 (an air and space simulation tool) was employed to model the motion of and generate trajectory data for the complex maneuvering targets [

28], and the precision of its generated motion states is well-established within the aviation simulation community.

(4) Network: 10 GbE Ethernet (latency < 1 ms that follows a uniform distribution in the range of [0.1 ms, 1 ms]) with TCP/IP protocol for real-time node communication, which is consistent with the actual latency characteristics of distributed interactive simulation systems.

(5) Dataset: The target motion data were generated based on realistic aerial maneuver templates, including position, velocity, acceleration, and heading angle, with random perturbations added as needed to simulate real motion noise. The dataset was divided into a training set (70%), a validation set (15%), and a test set (15%). The training set was used for model parameter training, the validation set was applied for the hyperparameter tuning of PLO optimization, and the test set was utilized for the independent evaluation of model generalization ability. To eliminate dimensional differences among features, all data were normalized to the range of [0, 1] using the min-max normalization method.

5.1.3. Comparison Models

The following five types of mainstream models were selected for comparison to cover the technical routes, including traditional mechanism-driven, single deep learning; hybrid deep learning; and different intelligent optimization algorithm-assisted approaches, ensuring fair comparison among all models:

(1) Traditional EKF model: A classic mechanism-driven DR algorithm using a constant acceleration motion model as the state transition equation. The process noise covariance and observation noise covariance were set through cross-validation, and the data were synchronized using min-max normalization.

(2) Pure LSTM model: Consistent in structure with the LSTM layer in the proposed model (two layers, hidden dimension is 256), with hyperparameters optimized via grid search with 3-fold cross-validation.

(3) Pure Transformer model: Consistent in structure with the modified Transformer encoder in the proposed model (two layers, embedding dimension is 256, number of attention heads is 4), with hyperparameters optimized via grid search with 3-fold cross-validation.

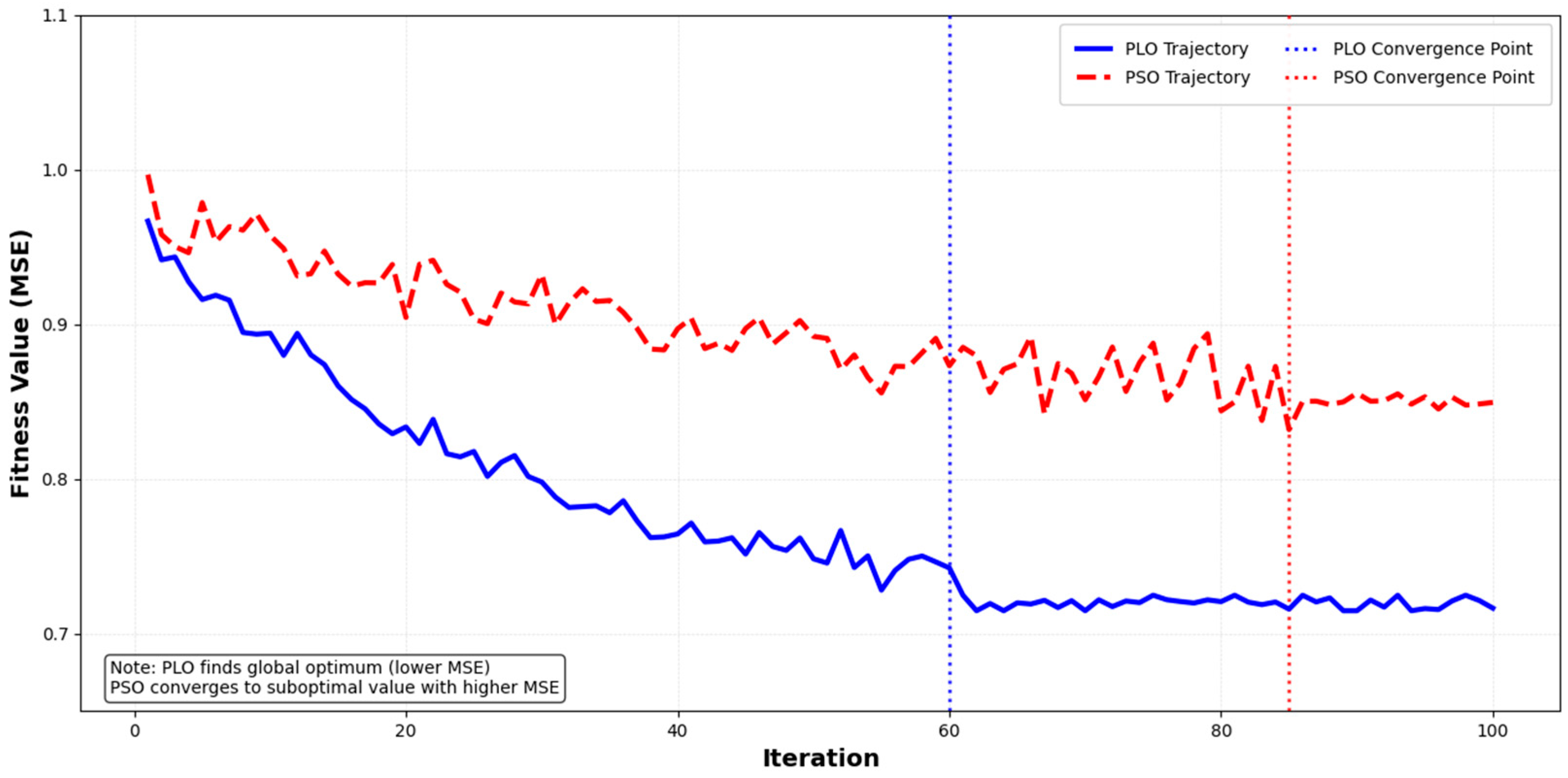

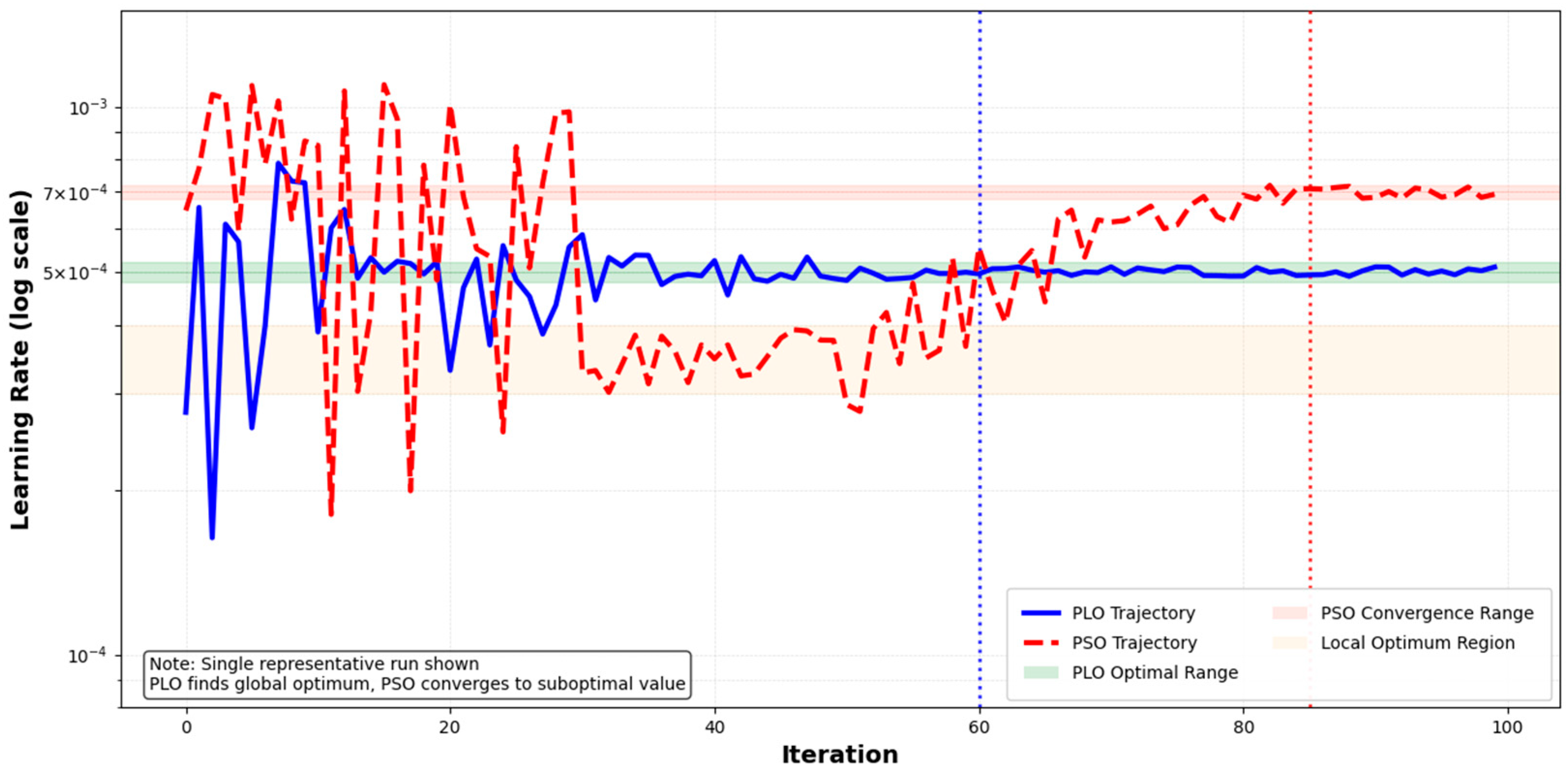

(4) PSO–Transformer–LSTM model: Identical in structure to that of the proposed model but using Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) instead of PLO for hyperparameter tuning (PSO parameters: number of particles is 30, maximum iterations is 100, inertia weight is 0.7, acceleration coefficient is 2.0).

(5) PLO–Stacked Transformer–LSTM model: A comparative model with simple sequential connection (Transformer encoder–fully connected layer–LSTM layer, no feature fusion layer). Hyperparameters are optimized via PLO with the same search range as that of the proposed model.

5.1.4. Evaluation Metrics

- (1)

Prediction accuracy metric

Overall accuracy: Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), and coefficient of determination (R2).

Single-feature error: position error (Euclidean distance of x/y/z coordinates, unit: m), velocity error (unit: m/s), acceleration error (unit: G), and heading angle error (unit: °), focusing on the prediction performance of core motion features.

Weighted comprehensive error: Weighted sum of normalized errors of each feature (Formula (4)), reflecting the actual error judgment logic of DR.

- (2)

Real-time performance metric

Average prediction time per sample (ms), reflecting computational efficiency, statistically based on GPU batch processing with batch size 32 and mixed precision training (FP16).

- (3)

Communication overhead metric

Information interaction frequency among simulation nodes (times/s): triggered when the position error exceeds the preset threshold of 1 m, calculated as (number of threshold-exceeding time steps/total number of time steps) × 100 Hz (time step frequency). Position error calculation formula is

where

are the true position coordinates, and

are the predicted position coordinates.

Position error threshold-exceeding ratio: percentage of time steps where position error exceeds the preset threshold (1 m), calculated as (number of threshold-exceeding time steps/total number of time steps) × 100%, reflecting the probability of triggering synchronization.

- (4)

Computational complexity metric

Number of model parameters (Params) and floating-point operations per second (FLOPs), reflecting the model’s resource consumption.

- (5)

Robustness evaluation metric

Noise sensitivity: R2, MSE, and node synchronization frequency under different noise intensities, quantifying the model’s anti-interference ability.

Threshold sensitivity: R2, MSE, and node synchronization frequency under different error thresholds, verifying the model’s ability to balance accuracy and communication overhead.

5.1.5. Training Configuration

All deep learning models were implemented using PyTorch 2.1.0 and optimized with the AdamW optimizer. Training proceeded for a maximum of 200 epochs, with early stopping (patience is 20 epochs) monitored on the validation loss. A batch size of 32 was used throughout. The loss function was Mean Squared Error (MSE). To ensure statistical significance, all experiments were repeated three times with different random seeds, and the reported results are the mean. The PLO and PSO optimization processes were also run independently three times, and the best-performing hyperparameter set was selected for final evaluation.

5.2. Results and Analysis

5.2.1. Model Performance Verification

To verify the multi-parameter collaborative fitting capability and working condition adaptability of the PLO model, the performance of the proposed model is evaluated against the traditional EKF baseline across the three maneuver scenarios described in

Section 5.1.1 (

Figure 8), and the results are summarized in

Table 3. In the three independent maneuver scenarios and the full-process continuous composite maneuver, all evaluation indicators of the proposed model are significantly better than those of the traditional EKF model. Among them, the reduction range of single-item errors is generally between 79% and 87%, and the reduction range of weighted comprehensive errors is stably between 84.5% and 86.6%. Moreover, the advantages are more prominent in extreme maneuver and snake-like evasive scenarios with strong nonlinearity and high coupling, which fully verifies the adaptability and prediction accuracy advantages of the model under different flight operating conditions.

5.2.2. Prediction Accuracy Comparison

Table 4 presents the prediction accuracy metrics of each model for the test set, with all data satisfying the mathematical logic of a negative correlation between

,

and consistent trends between MAE/MAPE. The key observations are as follows:

(1) The proposed PLO–Transformer–LSTM model achieved the best performance across all metrics, with goodness of fit reaching excellent levels in the field.

(2) Compared with the traditional EKF model, the proposed model reduced MSE by 42% ((1.24 − 0.72)/1.24 ≈ 0.419), MAE by 38%, RMSE by 39%, MAPE by 41% and increased by 0.183, significantly breaking through the limitations of traditional mechanism models relying on preset motion assumptions.

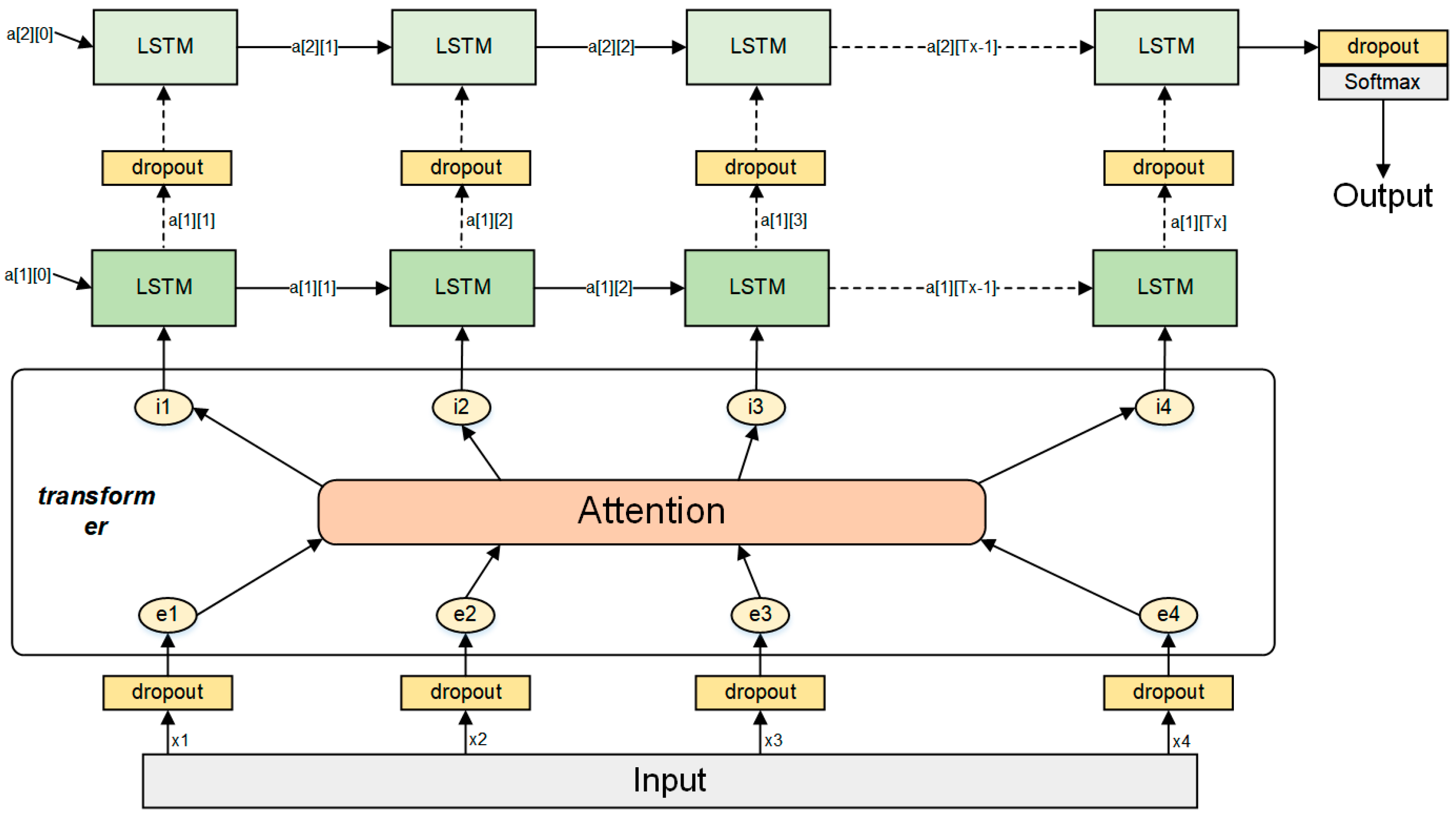

(3) The pure LSTM ( = 0.93, = 0.887) and pure Transformer ( = 0.98, = 0.880) models exhibited similar performance, both of which were lower than that of the hybrid models, verifying the complementary effect of “global dependency capture + local temporal modeling”; the pure Transformer had a slightly lower than that of the pure LSTM due to its neglect of local maneuvering details.

(4) The proposed model reduced MSE by 15.3% compared with the results for the PSO–Transformer–LSTM model ((0.85 − 0.72)/0.85 ≈ 0.153), demonstrating that the PLO algorithm outperforms PSO in global search capability and convergence speed, enabling better hyperparameter combinations.

(5) The PLO–Stacked Transformer–LSTM model has an MSE of 0.82, which is 12.7% higher than that of the proposed model, verifying the superiority of the targeted integration strategy over simple stacking.

5.2.3. Ablation Experiment

To verify the contribution of each core component (modified Transformer, LSTM, PLO) of the model, ablation experiments were designed. All ablation models use the same hyperparameter search space (shown in

Table 5) and optimization strategy (PLO, except Model 3 uses grid search) to ensure fair comparison.

(1) Model 1: With an MSE of 0.85 (8.6% lower than that of the pure LSTM model at 0.93), this result indicates that the PLO optimization can enhance the performance of a single model. However, after removing the Transformer’s global dependency capture capability, the MSE still increases by 18.1% compared to that of the Proposed Model. This verifies the necessity of the Transformer for predicting complex trajectory trends.

(2) Model 2: Achieving an MSE of 0.89 (9.2% lower than that of the pure Transformer model at 0.98), the PLO optimization similarly improves the performance of the single Transformer model. Nevertheless, the absence of LSTM’s local detail fitting leads to a 23.6% higher MSE than that of the Proposed Model, and its performance is inferior to that of Model 1. This highlights the core role of the Transformer in capturing global trends.

(3) Model 3: Although it achieved a similar MSE (0.89), its value (0.885) was lower than that of Model 2 (0.891). This result indicates that the grid search was less effective than PLO in optimizing the hyperparameters, as it was unable to locate the optimal combination. It further validates the superiority of the PLO algorithm in balancing global exploration and local exploitation.

5.2.4. Real-Time Performance Comparison

Table 6 shows the average prediction time per sample for each model, statistically based on GPU batch processing results. The key observations include the following:

(1) The traditional EKF model achieved the fastest prediction speed (0.02 ms/sample) due its reliance solely on mathematical formula recursion without complex neural network computations, making it suitable for scenarios with extreme real-time requirements (latency < 0.1 ms) but low accuracy demands.

(2) The pure LSTM and pure Transformer models exhibited similar prediction times (0.35 ms/sample and 0.38 ms/sample, respectively). The LSTM’s recurrent structure requires sequential computation by time step, resulting in general parallel efficiency; the Transformer’s multi-head attention mechanism supports parallel computation but has a slightly more complex layer structure, leading to comparable computational overhead between the two.

(3) The PSO–Transformer–LSTM and the proposed models had prediction times of 0.42 ms/sample and 0.43 ms/sample, respectively, only 0.05–0.08 ms longer than those for the pure models. Benefiting from the lightweight architecture (two layers for both Transformer and LSTM) + GPU parallel acceleration, the computational overhead is controllable. PLO optimization only affects the training process, without additional inference time costs.

(4) The proposed model comprises 2.8 M parameters and 3.2 G FLOPs, 133% more parameters than pure LSTM but only 77% more FLOPs, realizing a balance between accuracy and efficiency.

(5) The prediction time of all models was far below the real-time threshold (5 ms) in the DIS field. Even in scenarios with 1000 simultaneous entities, the total latency can be controlled within 20 ms through batch processing optimization, fully meeting engineering application requirements.

5.2.5. Communication Overhead Comparison

Table 7 presents the statistics for information interaction frequency and threshold-exceeding ratio among simulation nodes based on different models, with an error threshold of 1 m. The key observations include the following:

(1) The traditional EKF model had the highest interaction frequency (12.5 times/s) with a position error threshold-exceeding ratio of 38%. Due to a peak error of approximately 15 m, the threshold trigger mechanism was frequently activated, leading to excessive information interaction.

(2) The pure LSTM and pure Transformer models had interaction frequencies of 7.8 times/s and 7.5 times/s, respectively, representing reductions of 37.6% and 40.0% compared with the results for EKF, with the threshold-exceeding ratio decreasing to 22% and 21%, positively correlated with their error reduction rates (21–25%).

(3) The PSO–Transformer–LSTM model had an interaction frequency of 5.2 times/s, representing a 58.4% reduction compared with the results for EKF, with the threshold-exceeding ratio dropping to 15%, verifying the dual optimization effect of the hybrid architecture + intelligent optimization.

(4) The PLO–Stacked Transformer–LSTM model had an interaction frequency of 5.5 times/s, 25.5% higher than that of the proposed model, further confirming the advantage of the targeted integration strategy.

(5) The proposed model had the lowest interaction frequency (4.1 times/s), representing a 67.2% reduction compared with that of the EKF, with a threshold-exceeding ratio of only 12%. This result aligns with the core mechanism of DR algorithms: reduced errors directly decrease the number of threshold-exceeding triggers, and the impact of error peaks on interaction frequency is more significant in complex maneuvering scenarios (nonlinear correlation).

5.2.6. Robustness Experiment

- (1)

Noise Sensitivity Analysis

To verify the robustness of the proposed model under noise interference, comparative experiments involving three noise intensity levels (variance = 0.1, 0.5, 1.0) were conducted. The anti-noise performance and communication overhead of different models were quantitatively evaluated, and the experimental results are summarized in

Table 8.

The coefficient of determination of the proposed PLO–Transformer–LSTM model remains above 0.90 across all noise intensity conditions: achieves 0.962 when the noise variance is 0.1 and still maintains a result of 0.903 even as the variance increases to 1.0. In contrast, the of the EKF model drops drastically to 0.651 under the strong interference condition, with a noise variance of 1.0, exhibiting a significantly higher performance degradation rate than that of the proposed model. These findings fully demonstrate that the proposed model possesses superior anti-noise interference capability.

From the perspective of the state synchronization frequency metric, as noise intensity increases, the synchronization frequency of the proposed model slightly rises from 4.1 times per second to 7.3 times per second, whereas that of the EKF model increases from 12.5 times per second to 18.7 times per second during the same period. Even under strong noise conditions, the state synchronization frequency of the proposed model is still significantly lower than that of the comparative models, thereby effectively retaining the technical advantage of low communication overhead.

- (2)

Threshold Sensitivity Analysis

To verify the robustness of the proposed model across different error thresholds, comparative experiments involving four thresholds (0.5 m, 1.0 m, 1.5 m, 2.0 m) were conducted. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 9.

(1) As the threshold increases, the information interaction frequency of all models decreases, while the MSE slightly increases, reflecting the trade-off between prediction accuracy and communication overhead.

(2) The proposed model maintains a high (>0.9) across all thresholds. Its MSE increases from 0.70 to 0.78 (11.4% growth), which is lower than the EKF’s 32.3% growth and the PLO–Stacked model’s 18.3% growth; this verifies its strong robustness.

(3) At the threshold of 1.0 m, the proposed model achieves the optimal balance between accuracy ( = 0.962) and communication overhead (4.1 times/s), which is the recommended threshold for engineering applications.