1. Introduction

Ensuring the dependability of Integrated Circuits (ICs) has always been a significant concern for the VLSI field. However, the ongoing trend of technological miniaturization, along with the reduction of the supply voltage and node capacitances, is intensifying reliability concerns at an increasing rate [

1]. This problem becomes particularly critical in applications such as aerospace, automotive systems, and medical devices, where reliability, safety, and performance are paramount. As a result, IC failures can have severe consequences. Furthermore, the sensitivity of MOS transistor p–n junctions strongly depends on local electric fields and gate-controlled regions, highlighting gate-level components’ vulnerability to transient physical phenomena [

2]. Additionally, security issues have attracted increasing attention in recent decades due to the globalization of the semiconductor fabrication process [

3], as attackers exploit various vulnerabilities to compromise IC functionality. To this end, reliability and security are becoming increasingly interdependent, making it imperative to address any related problems or issues jointly [

4].

Hardware Trojans (HTs) are intentional malicious modifications to ICs that can cause malfunctions or leak sensitive information. These components can be inserted during various stages of the IC design and manufacturing process, and with a combination of the increasing complexity of ICs and the globalization of the supply chain, they may pose a significant security threat. There are several categories of HTs that depend on their activation mechanism [

5]. The first one is “always-on” HTs, which are always activated and exert their payload, meaning their effect on the IC, every cycle of the clock. Meanwhile, internally activated HTs are triggered by the occurrence of a specific logic value, whereas externally activated HTs wait for an external signal to be detected by an antenna or a sensor. For instance, activation may occur when the IC reaches a predetermined temperature [

6]. Last but not least, the category of HTs is trigger-activated, which means that specific and usually rare conditions are required before their payload is manifested, and it remains dormant until then. This makes them stealthier and harder to detect using conventional IC testing techniques, which test the IC’s behavior during their most common and expected functions.

Over the last few years, reliability-based HTs have attracted interest in the hardware security community as attackers exploit reliability issues to cause malfunctions and disrupt the proper behavior of ICs. Such issues include time-dependent aging or wearout mechanisms such as Negative Bias Temperature Instability (NBTI), Hot Carrier Injection (HCI), Time-Dependent Dielectric Breakdown (TDDB), Electromigration (EM), etc. Several types of reliability-based HTs have been proposed in the literature. More specifically, the concept of process reliability trojans is introduced in [

7]. The authors propose minor process modifications for both NBTI and HCI mechanisms to create an infected IC and potentially reduce its lifetime, making it difficult to detect. In [

8], a reliability trojan is injected into the design to manipulate BTI-induced aging behavior with process variations consideration. Low-reliability trojan circuits that are practically undetectable by side-channel detection techniques are proposed in [

9], accelerating aging due to EM, NBTI, and TDDB effects. Furthermore, in [

10], the authors demonstrate an attack that removes components, specifically decoupling capacitances from the power grid network, to aggravate EM. Exploiting the inherent circuit susceptibility to radiation through laser-based attacks to induce Single-Event Effects (SEEs) is a growing concern [

11].

Radiation-induced transient faults pose a significant threat to the reliability of semiconductor chips. These faults are primarily caused by high-energy particles, which originate either from cosmic radiation, in which primary cosmic rays interact with the atmosphere and generate cascades of secondary particles such as neutrons, or from radioactive decay within IC packaging materials, notably alpha particles [

12]. When these particles strike a sensitive transistor, they generate numerous electron–hole pairs that are absorbed by the transistor’s depletion region, potentially causing a temporary glitch at the output of the corresponding logic gate [

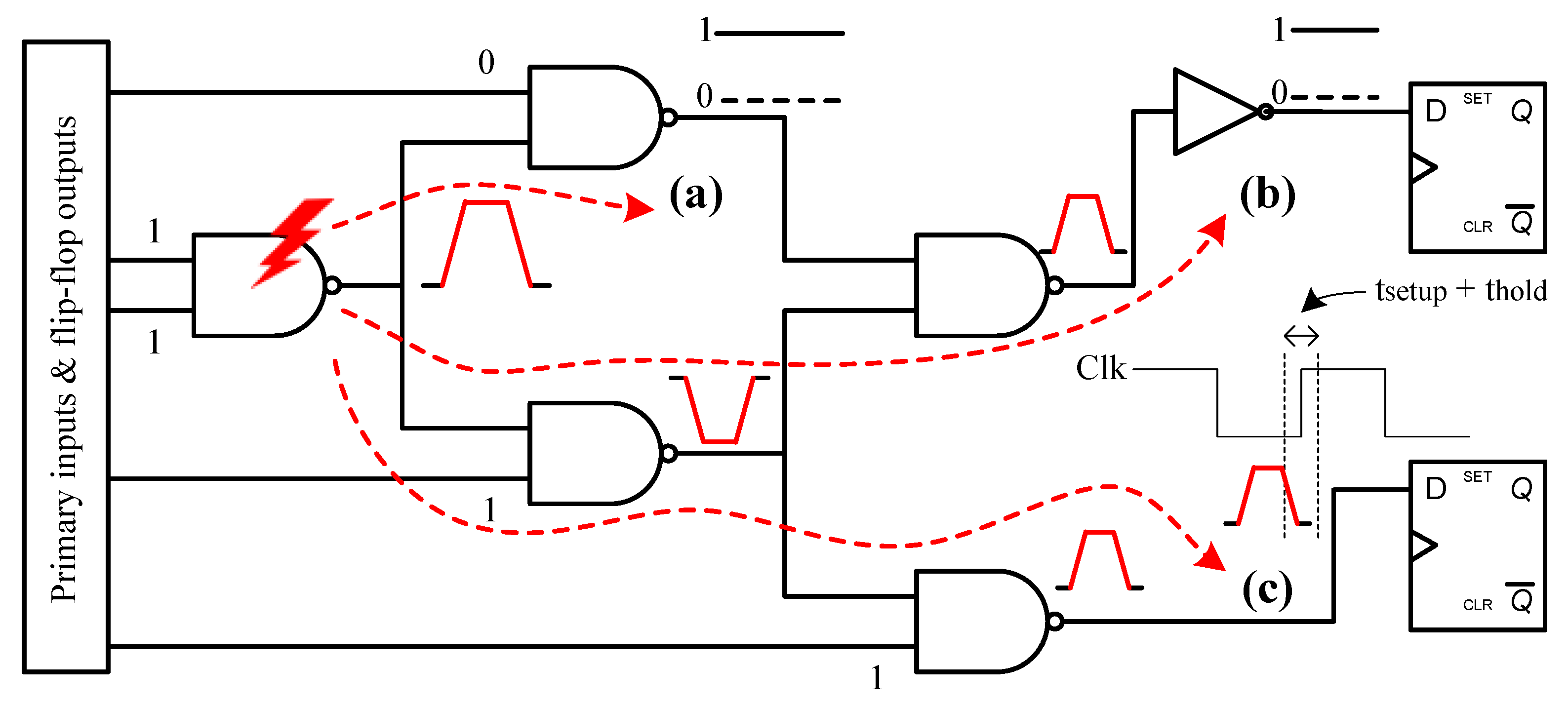

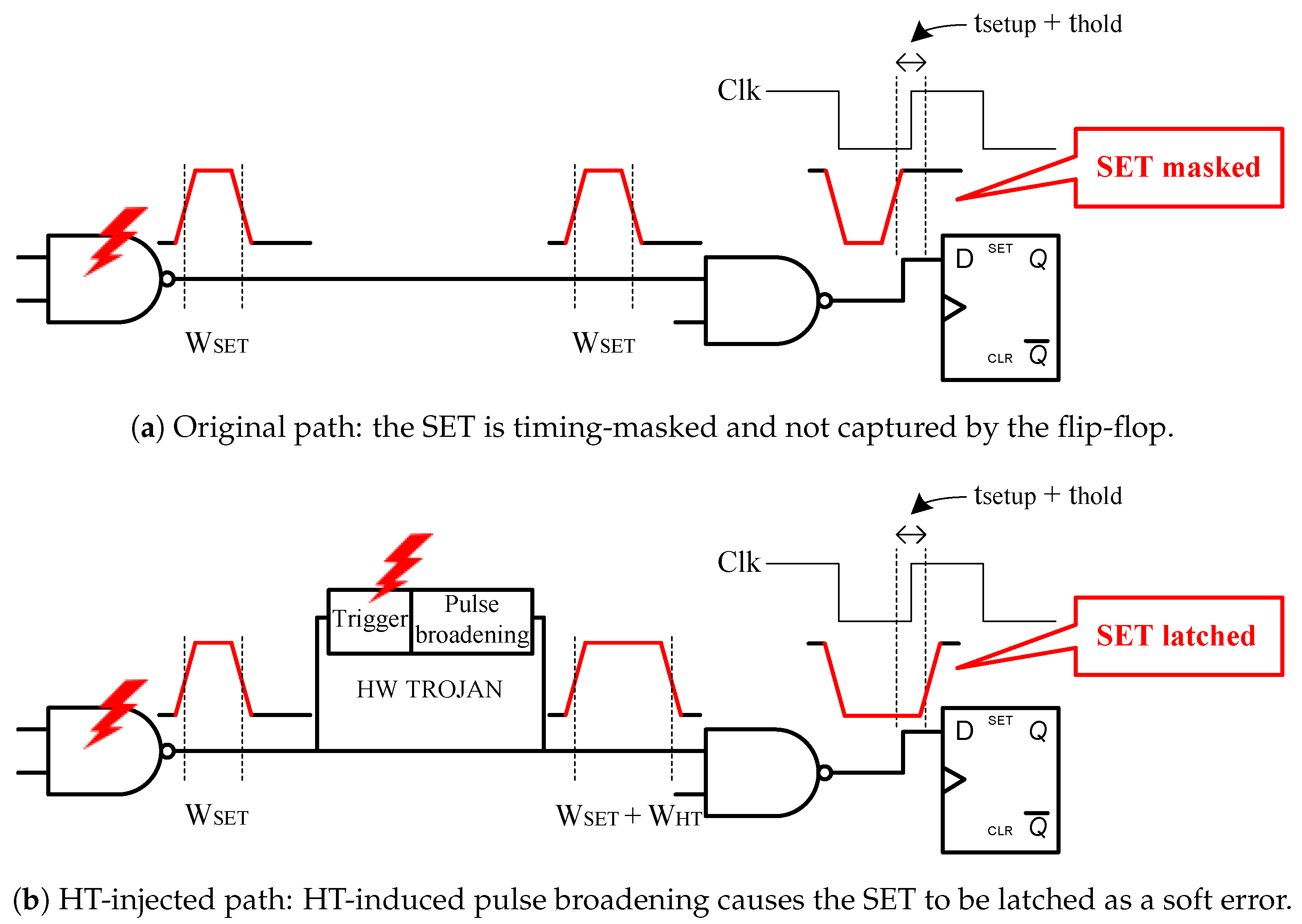

13]. This glitch is referred to as a Single-Event Transient (SET). Although SETs are non-destructive, they can propagate through combinational logic and be captured by a memory element, thereby creating a soft error, also referred to as a Single-Event Upset (SEU).

Inducing a soft error deliberately on a critical memory element can significantly disrupt the IC’s functionality. However, not all disturbances caused by various factors, such as particle hits, necessarily result in a soft error. This is because they might not propagate through the circuit due to several factors, including masking effects, which offer a form of protection to the circuit’s functionality, and the specific characteristics of the SETs, i.e., their pulse width and height. Furthermore, the IC designer can identify sensitive gates by performing a Soft Error Rate (SER) analysis [

14] and thus take radiation-hardening measures. Even with such countermeasures, SET-based attacks can still exploit radiation’s effects on ICs, as introduced in [

15]. A theoretical SET-based HT is also presented in [

16], exploiting SETs as both a trigger and a payload. However, such attacks have not yet been adequately explored.

The most established ways to detect any HT use methods that analyze the side-channel parameters, such as timing, power, voltages, and thermal radiation [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. These methods rely on identifying deviations from the design’s specifications that indicate the presence of an HT and are evaluated on benchmarks with a deliberately inserted HT. Therefore, the placement of a reliability-based HT to exploit a SET that can induce a soft error should be carefully considered to create adequate benchmarks for the proper evaluation of these methods.

In this study, we extend our previous work [

16] by proposing a method to create benchmarks injected with a SET-triggered reliability HT, providing a more reliable evaluation of HT detection techniques. The reliability HT is placed at the output of the target gate to broaden its SET pulse and ensure the generation of a soft error. SET characterization for each gate in the design, along with overall SER analysis, is used to identify the sensitive target gates for HT injection. Another essential condition to be met is the stealthiness of the HT. To this end, the potential target gates are filtered, excluding those that are part of the critical path or prime candidates for radiation hardening, since these would be obvious targets for an HT attack. We evaluate our method on various ISCAS ’89 benchmarks by identifying the increase in the sensitivity of targeted gates following HT injection and demonstrating the extent to which SER is affected.

The rest of the article is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides a detailed background on radiation-induced SET propagation and the concept both of SET-based reliability HT and its design;

Section 3 elaborates on our methodology for the implementation of the proposed sensitivity-aware HT injection;

Section 4 presents the evaluation results of the proposed approach and, finally,

Section 5 concludes this work.

3. Proposed Approach

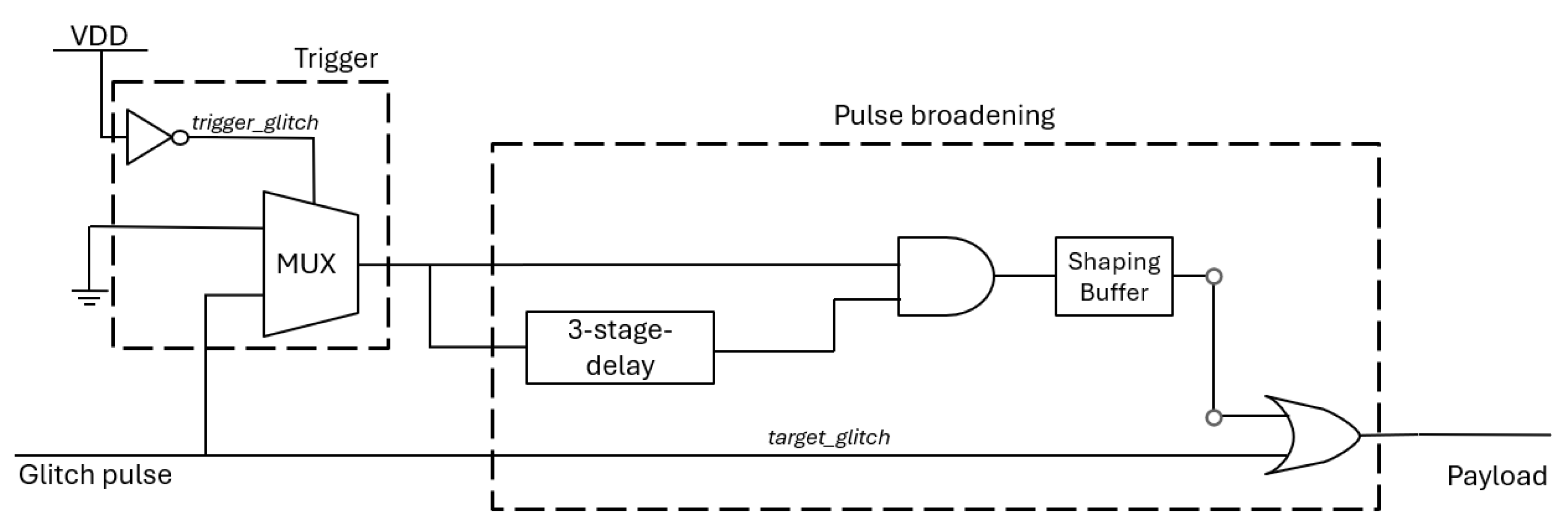

3.1. Implementation of the SET-Based HT

In

Section 2.2, we presented the theoretical function of the SET-based HT. The implementation of the HT is based on the [

15,

31] and its functionality is to extend a positive (0-to-1) SET glitch, ensuring the generation of a soft error. The HT consists of two main parts, the trigger and the payload, as shown in the schematic provided in

Figure 3. The trigger consists of a multiplexer, where one input is grounded and the other is connected to the output of the target gate. The HT is activated when a SET glitch occurs at the gate’s output. The payload is the pulse broadener, which consists of a shaping buffer, a three-stage delay logic, and a final buffer before the broadened signal merges with the original path using an OR gate.

The attack begins with the generation of two SET glitches, one on the trigger of the SET-based HT, the trigger_glitch, and one on the targeted gate, the target_glitch. The trigger_glitch switches the output of the MUX from the grounded input to the output of the targeted gate, allowing the target_glitch to propagate through the trojan. Right after the MUX, the target_glitch has its edges sharpened by a shaping buffer to form a better pulse. The next step is a three-stage delay and a final buffer, both of which contribute to the delay of the target_glitch. Finally, it reconvenes to the original path, merging the original target_glitch, effectively broadening its pulse width and duration.

The broadening of the target_glitch’s pulse width can be tuned and customized without the need to add any further gates to the original design of the SET-based HT. The basic idea is that the OR gate at the end of the HT propagates the original target_glitch and, before the gate returns to logic value 0, the delayed glitch passes as input and extends the gate’s logic value 1 output. The longer the glitch is delayed, the more extended the payload of the HT becomes, as long as there is enough of an overlap with the logic value 1 of the original target_glitch. This is achieved by utilizing the appropriate gates from the chosen library to add the desirable delay.

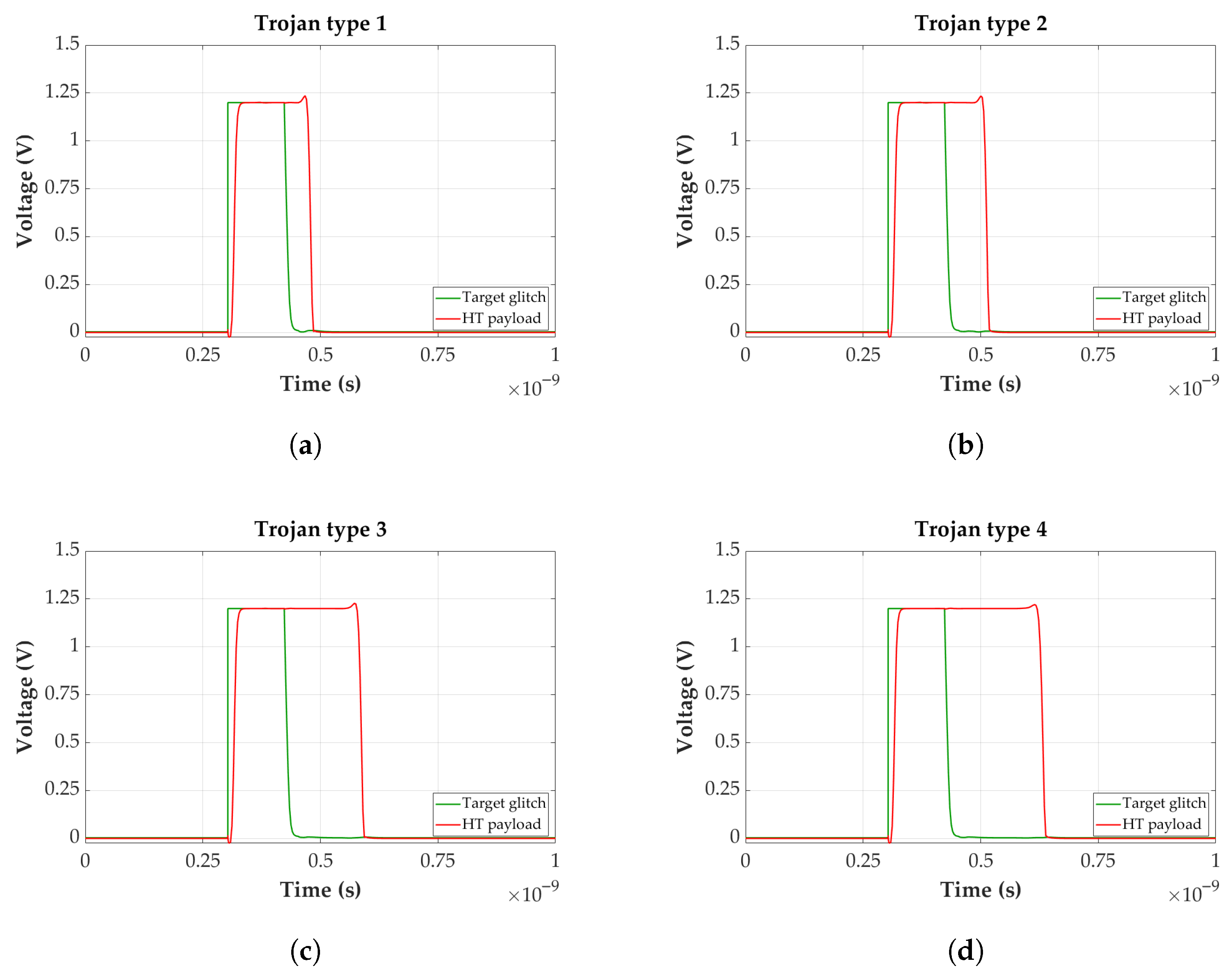

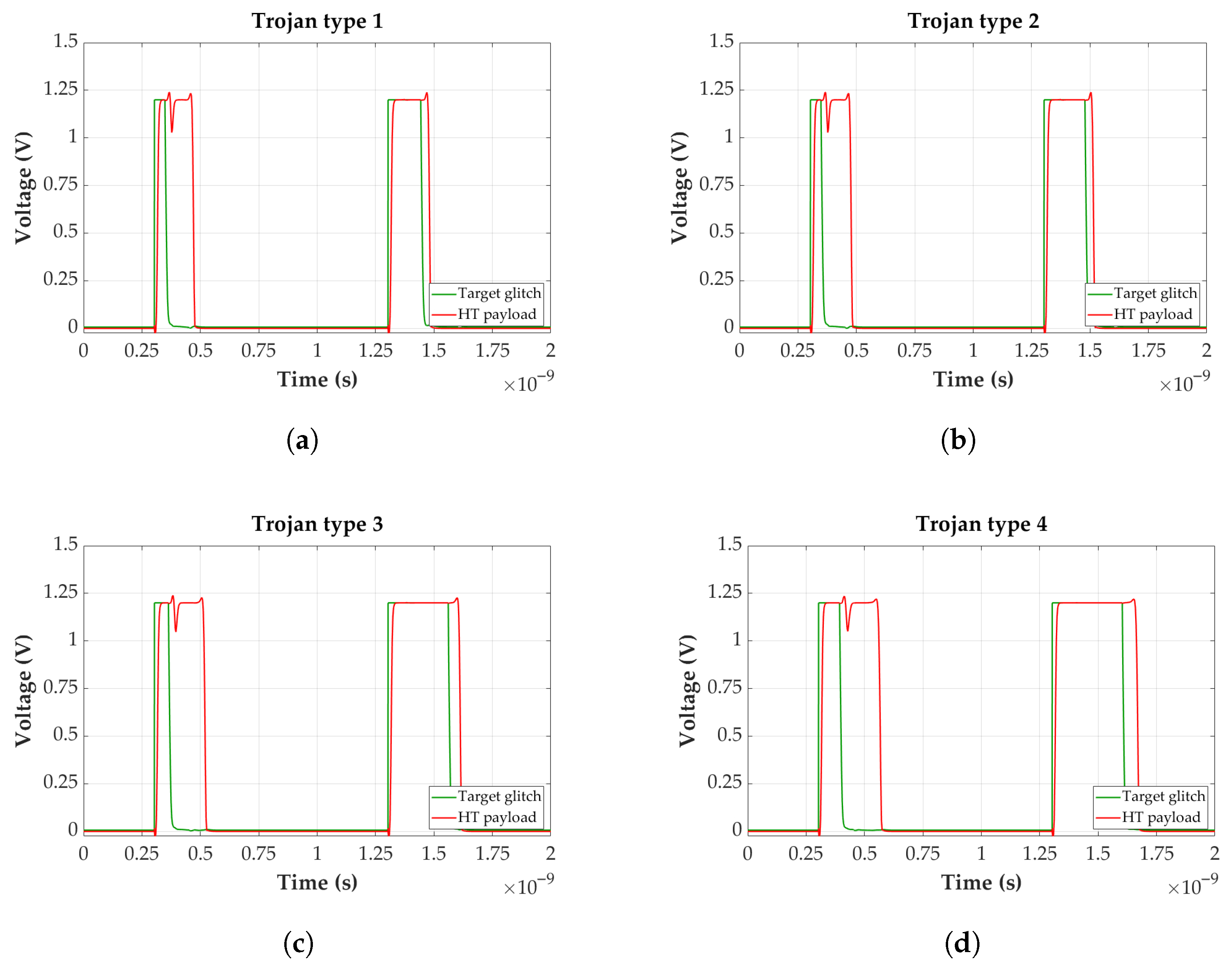

In

Figure 4, examples of the tuning capability of the SET-trigger Trojan are demonstrated for a transient glitch of 120 ps. This particular pulse width was selected as optimal based on being within and in adequate absolute distance from the minimum and maximum functional range of all four tuning configuration types presented. The ranges where each HT type was operating as intended, as shown in

Figure 5, were obtained after several SPICE simulations and will be explained in greater detail later on. Type 1 in

Figure 4a introduces the least amount of delay overhead to the HT-injected path, a mere 34 ps after Synopsys PrimeTime calculations. Even though it achieved the smallest widening of the pulse out of all the possible configurations, the payload still effectively increased the sensitivity of the targeted gate. After SPICE experiments, it was deduced that even though other configurations consisting of smaller gates exist, they did not produce the desired attack as described in

Section 2.2, and thus were rejected. On the other hand, the HT with the configuration shown in

Figure 4d has the greatest impact on the

target_glitch with a byproduct of the added delay to the path being 61 ps, as measured with Synopsys PrimeTime. As can be deduced, any further increase in the inserted path delay would endanger the detection of the SET-based HT, unless the targeted IC can accommodate a longer clock period.

Extensive SPICE simulations were performed to determine the maximum and minimum transient glitch pulses needed for the proposed HT to be successful. As mentioned before, the

target_glitch’s pulse is affected by many factors such as the angle and position of the particle hit and LET. As a result, consistent pulse generation is not easily achieved and variations will appear, calling for a need to study the probability of the attack occurring in the first place.

Figure 5 demonstrates that for each configuration there is a range where the generated pulse would be sufficient to produce an effective payload. The closer the width of the generated glitch is to the minimum and maximum of each type’s functional range, the greater the likelihood that it will not work as designed. As far as the minimum boundaries are concerned, any smaller pulse than that would result in two separate output pulses, since the voltage would pass the threshold to logic 0 and the circuit would fail to broaden the pulse, instead creating two pulses. On the other hand, for any pulse above the maximum values, the pulse-broadening circuitry would be unable to widen it further, and the output pulse would remain

target_glitch unchanged, rendering the HT redundant for those cases. Thus, for these specific four types and after the SPICE simulations were run for various pulses, the glitch’s pulse width was set at 120 ps as a sweet spot. The size range needed for the specific reliability HT to be functional is enough to be a valid concern. The simulations and their results, as shown in

Figure 4a–d, attest to the severity of the threat and reinforce the idea that it needs to be further studied to develop effective countermeasures against it in addition to detection techniques.

3.2. Gate Sensitivity Evaluation Algorithm

The evaluation of every gate’s sensitivity constitutes a crucial step in this work, since it is combined with the HT insertion and identifies which circuit components are most vulnerable. A component is considered sensitive when there is a significant probability that a generated SET at its output will propagate through the circuit and reach a memory element. As outlined in

Section 2.2, the evaluation process starts by determining the gates most susceptible to particle hit injections, which are then selected as candidates for placing the HT at their outputs. The primary objective is to strengthen the pulses of SETs, i.e., the disturbances caused by particle impact, to increase gate vulnerability and assess whether the overall susceptibility of the IC has been affected.

Algorithm 1, which constitutes the basis of the proposed methodology for calculating every gate’s sensitivity, relies on the Monte-Carlo simulation process and focuses on each gate individually, subjecting it to a particular number of particle hits to estimate its vulnerability. In other words, for each evaluation, only one SET is generated at a gate output and then propagated through the circuit. This process involves performing various simulations for different combinations of the primary inputs’ logic state, for diverse pulses of SETs, and for several particle hit injections. The primary objective is to determine the vulnerability of each gate.

In particular, according to Algorithm 1, the DEF file for each circuit is initially parsed to define the connectivity among gates and FFs. Additionally, the SPEF and Liberty files are utilized to obtain accurate timing information for each gate, while a levelization process—organizing gates into hierarchical levels—is performed to facilitate simulation and the propagation of SETs. Then, as outlined in the algorithm, a sufficient number of simulations are performed by applying transient faults with different amplitudes to each gate at various time instances within the clock cycle. In this regard, the resulting pulse is affected by the three masking mechanisms as it propagates through the circuit. Ultimately, the sensitivity of gates corresponds to the probability that such transient faults will be successfully captured by at least one memory element across the performed simulations, as indicated by the observed number of soft errors.

| Algorithm 1 Gate sensitivity analysis |

Parse the design input files (DEF, SPEF, Liberty). Organize the gates into hierarchical levels. For each gate and for each combination of primary input values: Initialize the error counter: Soft_Errors = 0. Inject various SETs at different time instances. Check SET propagation, verifying if they are logically or electrically masked. If not masked, propagate the SETs further to the fanout gates. If a SET reaches a flip-flop input and violates the setup or hold time, increase the error counter (Soft_Errors += 1).

Compute the sensitivity of the gate as

|

Lastly, beyond the scope of optimal HT placement, the evaluation of gate vulnerability can be utilized for hardening techniques applications to enhance IC robustness [

32]. This targeted approach minimizes overhead in delay, area, and power consumption, as these methods are applied only to the most sensitive components rather than the entire circuit.

3.3. Sensitivity-Aware HT Injection Algorithm

In this section, we present the sensitivity-aware HT injection methodology, primarily utilizing the evaluation of the gate vulnerability for the whole design to faults caused by radiation. The importance of the sensitivity analysis, as described, lies in identifying gates that are highly likely to result in soft errors, contributing to determining the optimal regions for attackers to insert a SET-based HT.

A modified version of the SER evaluation presented in [

22] is utilized in the methodology outlined in the Algorithm 1, with the exception that it neglects Single-Event Multiple Transients (SEMTs) as the proposed method targets each gate separately to identify its sensitivity. This study adopts the approach of [

14] incorporating Dynamic Timing Analysis (DTA) for SET propagation, resulting in a more accurate SER analysis. As mentioned, a gate is considered sensitive when there is a high probability that a generated SET will propagate through the circuit and be captured by a memory element. For this reason, the significant number of simulations, involving various primary input vectors, and the circuit complexity, especially in the large-scale ones, are the main critical factors that render this process quite time-consuming. However, it provides an accurate analysis to estimate the sensitivity of the gates, contributing significantly to the ultimate objective of increasing the circuit’s overall susceptibility and, thus, ensuring that more soft errors occur on the memory elements of the design. This outcome will be achieved by injecting the SET-based HT in less vulnerable gates, thereby increasing the probability that they may lead to a soft error. In particular, according to the Algorithm 2, gates are sorted based on the probability that corresponds to their sensitivity levels. The gates chosen for the insertion of the HTs are those pertaining to a moderate susceptibility range—specifically the gates that belong to levels ranging from 50% to 70% of the maximum evaluated sensitivity. The selection of this range stems from the principle that designers focus on enhancing the radiation hardness of the critical gates. Therefore, the potential insertion of the reliability HTs in less susceptible gates will undoubtedly result in a significant increase in sensitivity.

| Algorithm 2 Sensitivity-aware injection methodology of a SET-based HT. |

- 1:

Execute Algorithm 1 to evaluate gate sensitivity. - 2:

Use the obtained results as input for the following steps. - 3:

Sort the gates based on their sensitivity levels. - 4:

Choose the potential target gates with an average susceptibility range from 50% to 70%. - 5:

Extract from the selected gates the ones belonging to the critical timing paths. - 6:

Extract from the selected gates the ones that become part of the critical path when the trojan is inserted. - 7:

For each potential target gate calculate the new delay for every path after the injection of the trojan. - 8:

Calculate the amount of HTs to insert so the added gates do not surpass 10% of the original gate sum. - 9:

Inject no more than the specified number of trojans into a corresponding number of available target gates.

|

Another crucial step in our proposed methodology, and one of the extensions from our original paper, is the meticulous consideration of the trojans’ impact on the timing of the design. The broadening of the glitch pulse, as mentioned in

Section 3.1, is mainly based on delaying it and reconverging it with itself to elongate its duration. The most noticeable alteration would involve a difference in the critical path’s timing, since it would also impact the duration of the clock period. Thus, from the selected gates, the ones that are part of the critical path of the design are excluded. The next step is to ensure that the overhead of delay introduced to all of the targeted gates’ paths does not overcome the critical paths. To that end, the new timing of every path, which includes the selected gates, is calculated, this time including the delay overhead along with the insertion of the HT in the affected paths. If the new potential timing of a path surpasses that of the critical path, the selected gate included in that path is removed from consideration. After the end of these steps, the set of the remaining target gates contains the best candidates for the HT to be injected.

Finally, the last stage of our algorithm is ensuring that zero deviations in the size of the chip exist from the original calculated area. For this reason, the number of HTs inserted needs to be restricted so that their accumulative gates remain below 10% of the original design’s overall gate sum. Once this number has been calculated, up to that many HTs are injected into the design as output of the target gates. One trojan is connected only to one target gate, meaning that not all target gates will necessarily be selected, and vice versa; if not enough target gates exist, less than the maximum number of trojans will be inserted. The aforementioned timing and area criteria, together with the fact that the targeted gates chosen are within the moderate susceptibility range previously set, provide significantly more challenging benchmarks for any side-channel analysis identification method.

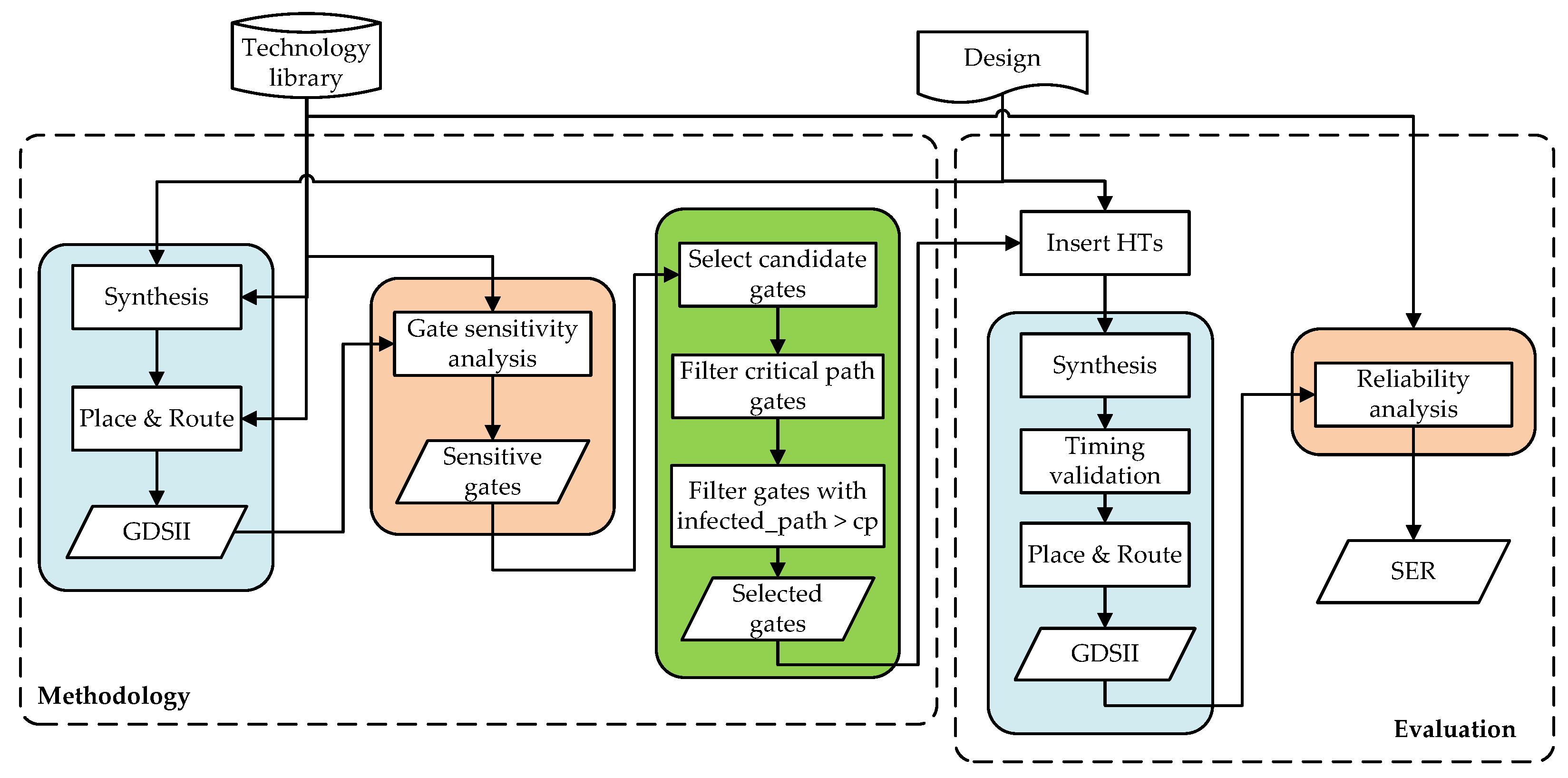

Figure 6 illustrates the overall flow of the proposed sensitivity-aware HT injection methodology. Starting from synthesis and place-and-route of the target design using the selected technology library to generate the layout, a gate-level sensitivity analysis is performed to identify suitable HT insertion points. Subsequently, candidate gates within a moderate sensitivity range are selected and further filtered by excluding gates belonging to the critical timing paths. To evaluate the methodology, the SET-based HTs are then inserted at the outputs of the remaining candidate gates, followed by timing validation to ensure that the delay overhead introduced by the HT does not violate the original critical path constraints. A final reliability analysis is performed to evaluate the impact of the inserted HTs on gate sensitivity and overall SER, enabling a quantitative assessment of the methodology.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

All the experiments are conducted on a Linux workstation with an 8-core Intel Xeon @3.5 GHz and 16 GB of memory. To reliably evaluate our approach, several typical benchmarks from the ISCAS ’89 suite are used. The SET-based HTs are injected at a high description level (HDL), and the benchmarks are synthesized using Synopsys Design Compiler with the 45 nm Nangate OpenCell Library. Place and Route is then performed with Cadence Innovus. Since the CAD tools recognized the HT logic as redundant, they attempted to eliminate it during synthesis and optimization. To avoid this, the HTs are synthesized independently and subsequently inserted into the benchmarks, with the set_dont_touch constraint applied to their cells to ensure they remain intact.

Although the experimental evaluation is performed using a 45 nm technology node, the proposed approach is not tied to a specific process. Technology scaling generally increases the circuit’s susceptibility to SET-induced soft errors due to reduced node capacitances, lower supply voltages, and tighter timing margins, which confine masking effects [

24]. Since the proposed methodology relies on relative gate sensitivity, SET propagation, and masking effects, rather than absolute technology parameters, it can be directly applied to more advanced technology nodes with appropriate calibration of the inserted HT and technology-dependent parameters.

The selection of the benchmarks is based on the following criteria. First, the number of logic gates should be sufficient to provide an adequate number of sensitive gates as targets. Second, the circuit size should be large enough to sufficiently simulate SET propagation on long paths to obtain reliable results while ensuring that the reliability HT will remain stealthy. Last but not least, to ensure a challenging benchmark is created, the pathway in which the HT is introduced should not exceed the critical path delay or, as a result, modify the clock period. Thus, the benchmarks were also filtered based on the additional delay introduced to all the paths of the targeted gate after the insertion of the HT.

4.2. Assessment of the HT Injection Methodology

The size of the benchmark correlates with the critical path. The shorter the critical path, the smaller its delay, and vice versa. This immediately affects the overhead amount of delay that can be added to the rest of the benchmark’s paths before they surpass the critical path and take its place. Simultaneously, the HT itself adds to the gate count and, thus, the total die area needed for fabrication. These factors were taken into consideration when choosing appropriate benchmarks that would enable the stealthy operation of the inserted HTs.

Table 1 summarizes the number of gates, flip-flops, and targeted gates, together with the corresponding increase in the average sensitivity of these gates following the SET-based HT injection, as well as the overall circuit SER. Gate sensitivity is obtained from Algorithm 1, whereas the overall circuit SER is computed as the average sensitivity across all the gates. The results show that the integration of the proposed methodology based on Algorithm 2 increases both the targeted gate sensitivity and overall SER across all benchmarks. The first key conclusion is that the variation in targeted gate sensitivity does not scale directly with the size of the benchmark. In other words, larger designs have a lower relative increase in the sensitivity of the targeted components. This fact can be explained by their longer logic paths to the memory elements and extended clock periods, two factors that mitigate the impact of SETs on circuit operation.

Another important observation is that the increase in SER is not proportional to the number of inserted HTs. For example, the s15850 benchmark shows the highest overall SER increase despite having only one gate combined with an HT, whereas other circuits with a larger number of HTs (e.g., s13207, s5378) exhibit a comparatively lower SER elevation. Therefore, we notice that the quality of the targeted gates, defined by their type, path location, and sensitivity, can be more crucial and effective than the quantity of HTs inserted in the circuits. In other words, specific gates, when affected by particle hits, generate SETs with a higher impact on circuit operation. Hence, if such vulnerable components are combined with HTs, they can significantly disrupt the expected system functionality.

Since each benchmark is of a different size, four trojan configurations, with varied payloads and pulse widths, were used in our experiments. The gate count of each configuration is the same; however, each of them adds a different delay to the timing of the inserted path(s). As such, for each benchmark, the configuration of the trojan inserted in the selected gates imposed the greatest payload while not violating the critical path constraint. As previously shown in

Figure 4, type 1 adds the least amount of timing overhead and type 4 adds the most, while type 1 has the smallest payload and type 4 the maximum. For the experiments, the maximum impact was favored over the maximum stealthiness, and it was decided that only one type would be inserted into every targeted gate per benchmark for clearly measuring the payload of each type of trojan. The total number of the SET-based HTs injected was set so that they do not surpass 10% of the original benchmark’s total gates.

Table 2 provides more details on these conditions and their impact on each benchmark.

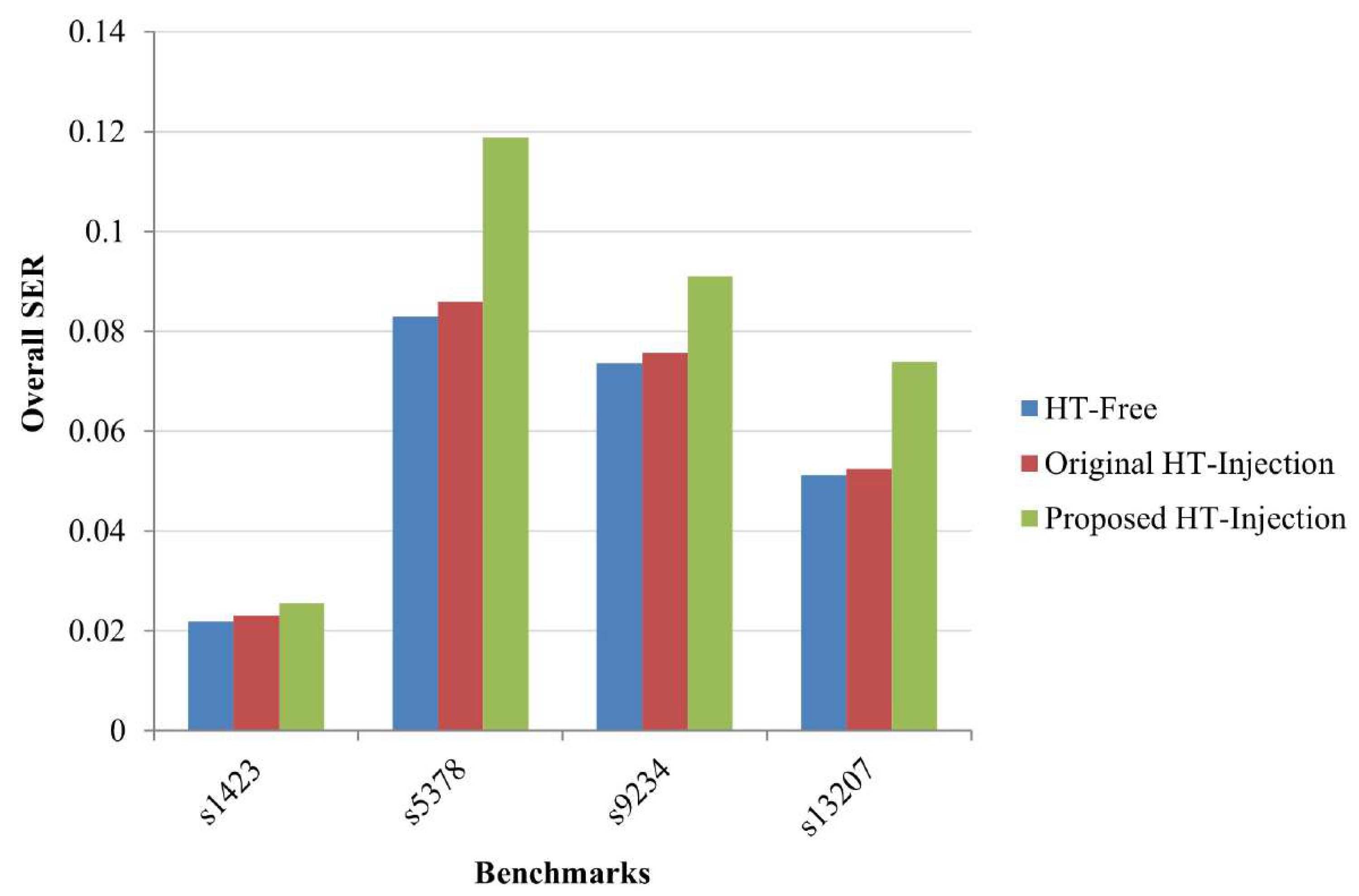

Finally,

Figure 7 depicts the SER evaluation for four ISCAS ’89 benchmarks, comparing the SER in circuits without HTs, the theoretical original HT-injection approach from [

16], and the proposed methodology. The results show that the proposed method results in the highest increase in SER across all benchmarks, even if only a limited number of HTs is integrated. This fact confirms that combining HTs with gates of moderate sensitivity significantly worsens overall circuit susceptibility. The inserted HTs strengthen the generated SETs, thereby increasing the vulnerability of the affected gates and elevating the likelihood that these transients will be captured by memory elements, ultimately amplifying the overall IC vulnerability.