Image-Based Spatio-Temporal Graph Learning for Diffusion Forecasting in Digital Management Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A parcel-level structured pest diffusion graph modeling strategy is proposed, enabling unified representation of UAV imagery, meteorological data, and terrain information within a graph framework and facilitating efficient modeling of irregular farmland spatial relationships;

- A GNN framework (STAGE) combining temporal convolution and dynamic spatial attention is designed to learn time-varying diffusion intensity and propagation directions of pest spread;

- An environment-driven diffusion response modeling mechanism (EEF) is introduced to automatically learn the influence of wind direction, wind speed, and terrain barriers on pest propagation;

- An interpretable diffusion path simulation module (DPSE) is developed to identify dominant diffusion channels and key contributing nodes, enhancing the practical applicability of the model in agricultural management;

- Extensive validation is conducted on multi-region and multi-crop field datasets, demonstrating clear advantages in prediction accuracy, diffusion consistency, and generalization capability.

2. Related Work

2.1. Application of UAV and Remote Sensing Imagery in Pest Monitoring

2.2. Pest Diffusion Modeling and Ecological Dynamic Prediction

2.3. Graph Neural Networks and Spatio-Temporal Attention in Ecological Scenarios

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Data Collection

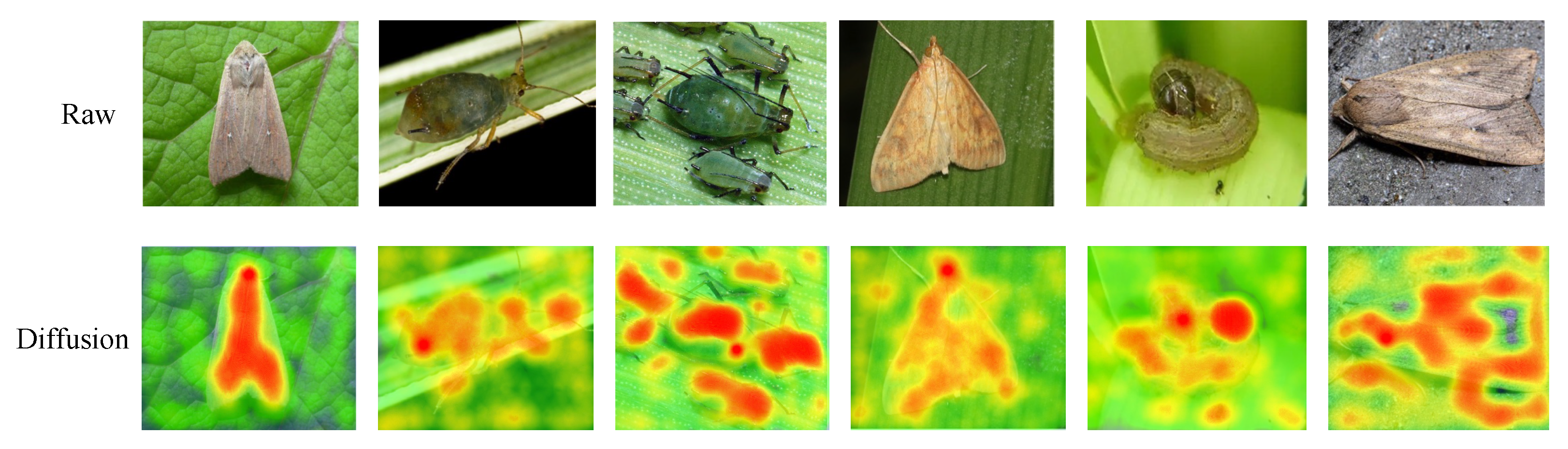

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

3.3. Proposed Method

3.3.1. Overall

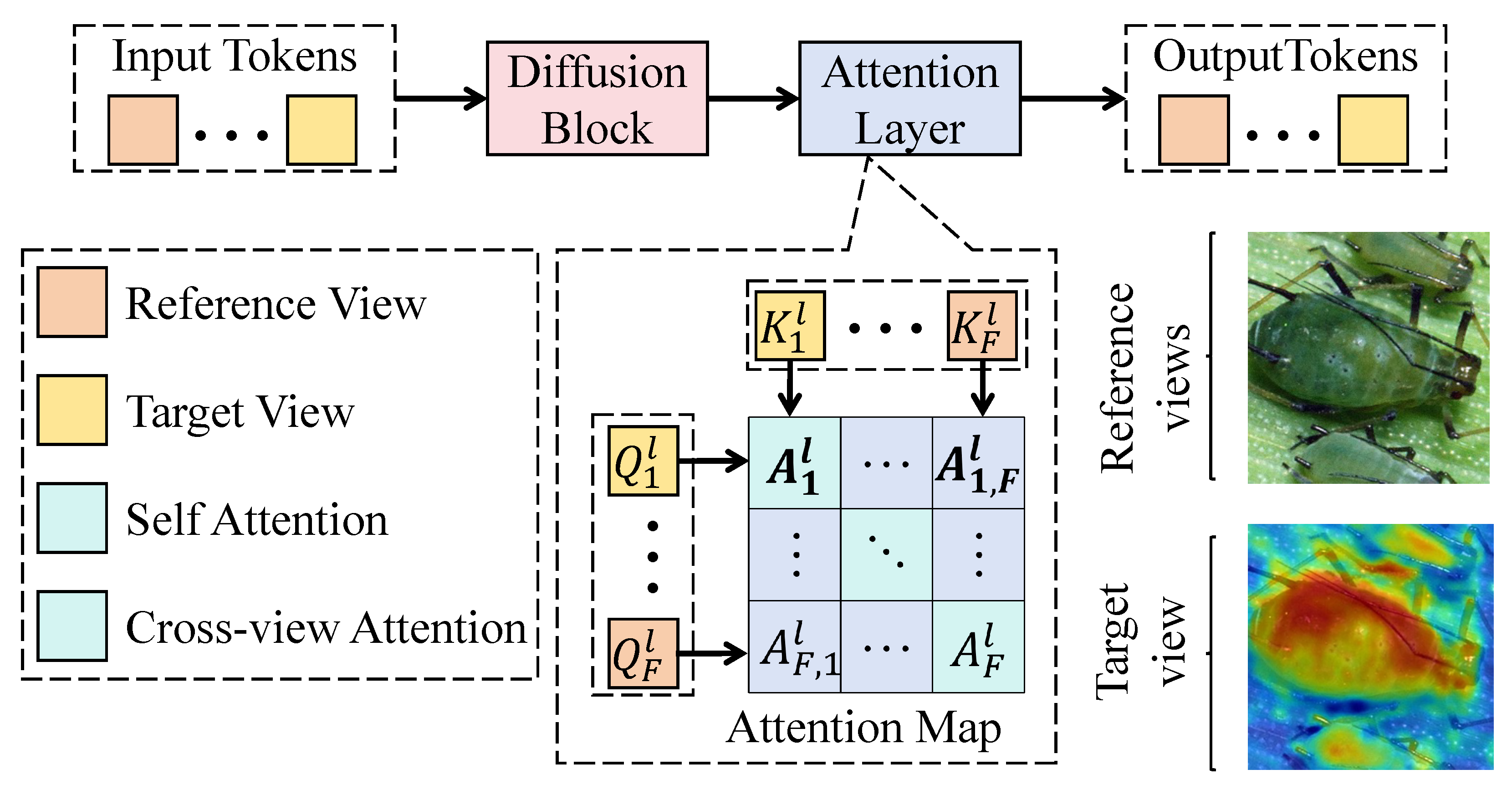

3.3.2. Spatio-Temporal Attention Graph Encoder

3.3.3. Environmental Embedding Fusion

3.3.4. Diffusion Path Simulation and Explainability

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Settings

4.1.1. Platform and Training Configuration

4.1.2. Baseline Models and Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Performance Comparison on the Bayan Nur Dataset

4.3. Performance Comparison on the Tangshan Dataset

4.4. Ablation Study of Different Modules on Two Datasets

4.5. Discussion

4.5.1. Support for Agricultural Information Systems and Decision-Making

4.5.2. Failure Modes and Limitations

4.6. Limitation and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Mathematical Formulations for Data Preprocessing

Appendix A.1. Radiometric Calibration and Geometric Correction

Appendix A.2. Cloud Removal and Label Generation

Appendix A.3. Data Augmentation and Feature Standardization

Appendix B. Mathematical Formulations for STAGE

Appendix C. Mathematical Formulations for EEF

Appendix C.1. Feature Encoders

Appendix C.2. Environmental Attention

References

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Jleli, M. A numerical analysis for fractional model of the spread of pests in tea plants. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 2022, 38, 540–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, C.; Athanassiou, C.; Carvalho, M.O.; Emekci, M.; Gvozdenac, S.; Hamel, D.; Riudavets, J.; Stejskal, V.; Trdan, S.; Trematerra, P. Changes in the distribution and pest risk of stored product insects in Europe due to global warming: Need for pan-European pest monitoring and improved food-safety. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2022, 97, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zeng, J.; Wu, K. Research and Application of Crop Pest Monitoring and Early Warning Technology in China. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.A.; Salifu, D.; Mwalili, S.; Dubois, T.; Collins, R.; Tonnang, H.E. An expert system for insect pest population dynamics prediction. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X. A new strategy for tuning ReLUs: Self-adaptive linear units (SALUs). In Proceedings of the ICMLCA 2021; 2nd International Conference on Machine Learning and Computer Application, Shenyang, China, 17–19 December 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Koralewski, T.E.; Wang, H.H.; Grant, W.E.; Brewer, M.J.; Elliott, N.C.; Westbrook, J.K. Modeling the dispersal of wind-borne pests: Sensitivity of infestation forecasts to uncertainty in parameterization of long-distance airborne dispersal. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 301, 108357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, T. Pest and disease prediction and management for sugarcane using a hybrid autoregressive integrated moving average—A long short-term memory model. Agriculture 2025, 15, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkan, E.; Aydin, A. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Insect Damage Spread Using Auto-ARIMA Model. Croat. J. For. Eng. J. Theory Appl. For. Eng. 2024, 45, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Alami, M.M.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Abbas, Q.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; Rao, M.J.; Mosa, W.F.; Abbas, Q.; et al. Drones in plant disease assessment, efficient monitoring, and detection: A way forward to smart agriculture. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendžić, S.; Novak, H.; Zovko, M.; Pajač Živković, I.; Lešić, V.; Maričević, M.; Lemić, D. Hyperspectral Sensing and Machine Learning for Early Detection of Cereal Leaf Beetle Damage in Wheat: Insights for Precision Pest Management. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, D.; Rafiq, S.; Saini, P.; Ahad, I.; Gonal, B.; Rehman, S.A.; Rashid, S.; Saini, P.; Rohela, G.K.; Aalum, K.; et al. Remote sensing and artificial intelligence: Revolutionizing pest management in agriculture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1551460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, L. Detection and discrimination of disease and insect stress of tea plants using hyperspectral imaging combined with wavelet analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 193, 106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.; Gupta, V.; Aamash, M.; Upadhyay, T. Machine learning for pest detection and infestation prediction: A comprehensive review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2024, 14, e1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wa, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Q. A dilated segmentation network with the morphological correction method in farming area image Series. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wa, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Sun, P.; Ma, Q. High-accuracy detection of maize leaf diseases CNN based on multi-pathway activation function module. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Liu, Y.; Khan, A.; Ahmed, B.; Sarker, S.K.; Ghadi, Y.Y.; Bhatti, U.A.; Al-Razgan, M.; Ali, Y.A. Crop monitoring using remote sensing land use and land change data: Comparative analysis of deep learning methods using pre-trained CNN models. Big Data Res. 2024, 36, 100448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyuddin, G.; Khan, M.A.; Haseeb, A.; Mahpara, S.; Waseem, M.; Saleh, A.M. Evaluation of machine learning approaches for precision farming in smart agriculture system: A comprehensive review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 60155–60184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, M.O.; Zahid, A. Deep learning in controlled environment agriculture: A review of recent advancements, challenges and prospects. Sensors 2022, 22, 7965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Jin, H.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Hu, C.; Lv, C. Integrating Stride Attention and Cross-Modality Fusion for UAV-Based Detection of Drought, Pest, and Disease Stress in Croplands. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Zhang, B.; Hou, Y.; Xiong, X.; Dong, C.; Lu, W.; Li, L.; Lv, C. A Spatiotemporal Attention-Guided Graph Neural Network for Precise Hyperspectral Estimation of Corn Nitrogen Content. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Lao, J.; Liu, Y.; Chang, C.C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Zhou, H. Pine pest detection using remote sensing satellite images combined with a multi-scale attention-UNet model. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 72, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Tian, T.; Yin, J. A review of unmanned aerial vehicle low-altitude remote sensing (UAV-LARS) use in agricultural monitoring in China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Huang, X.; Ma, J. Application progress of UAV-LARS in identification of crop diseases and pests. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Wang, L.; Yin, D.; Sun, K.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Li, D. Deep learning for change detection in remote sensing: A review. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 26, 262–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Xu, W.; Lin, J.; Duan, L.; Gao, P.; Zhang, C.; Lv, X. Combining multi-dimensional convolutional neural network (CNN) with visualization method for detection of aphis gossypii glover infection in cotton leaves using hyperspectral imaging. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 604510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschauer, N.; Parnell, S. Analysis of mathematical modelling approaches to capture human behaviour dynamics in agricultural pest and disease systems. Agric. Syst. 2025, 226, 104303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Hong, S.; Xu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cui, B.; Yang, M.H. Diffusion models: A comprehensive survey of methods and applications. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgroom, M.G. Epidemiology and sir models. In Biology of Infectious Disease: From Molecules to Ecosystems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Montes de Oca Munguia, O.; Pannell, D.J.; Llewellyn, R. Understanding the adoption of innovations in agriculture: A review of selected conceptual models. Agronomy 2021, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, R.; Sciarretta, A. Spatial patchiness and association of pests and natural enemies in agro-ecosystems and their application in precision pest management: A review. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 1836–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Gong, X.; Zhao, L. Graph neural network for spatiotemporal data: Methods and applications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.00012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, H.; Martí, L.; Sanchez-Pi, N. A graph neural network with spatio-temporal attention for multi-sources time series data: An application to frost forecast. Sensors 2022, 22, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Xiu, Y.; Kong, J.; Yang, C.; Zhao, C. An effective pyramid neural network based on graph-related attentions structure for fine-grained disease and pest identification in intelligent agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, S.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, J.; Fan, D.; Lin, J.; Wang, Q. Atrous Pyramid GAN Segmentation Network for Fish Images with High Performance. Electronics 2022, 11, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Xie, P.; Teng, F.; Wang, B.; Ji, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, T. HiSTGNN: Hierarchical spatio-temporal graph neural network for weather forecasting. Inf. Sci. 2023, 648, 119580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.A.; Li, F.; Li, A.; Niu, Z.; Liu, Z. Urban intersection traffic flow prediction: A physics-guided stepwise framework utilizing spatio-temporal graph neural network algorithms. Multimodal Transp. 2025, 4, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zeng, Z. Challenges in remote sensing based climate and crop monitoring: Navigating the complexities using AI. J. Cloud Comput. 2024, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yu, L.; Liu, X.; Peng, D.; Chen, X.; Du, Z.; Tu, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Q. A Global Review of Monitoring Cropland Abandonment Using Remote Sensing: Temporal–Spatial Patterns, Causes, Ecological Effects, and Future Prospects. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 5, 0584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Li, W.; Shen, J.; Zhou, C.; Li, S.; Suo, J.; Yang, J.; Jia, R.; Lv, C. A Diffusion-Based Detection Model for Accurate Soybean Disease Identification in Smart Agricultural Environments. Plants 2025, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.Y.; Wong, W.K.; Woo, W.C. Convolutional LSTM network: A machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Lin, D. Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Xie, X.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y. Map-matching for low-sampling-rate GPS trajectories. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 4–6 November 2009; pp. 352–361. [Google Scholar]

| Data Type | Source | Quantity/Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Study regions | Bayan Nur (Inner Mongolia), Tangshan (Hebei) | 2 regions |

| Crop types | Maize, Wheat | 2 crop categories |

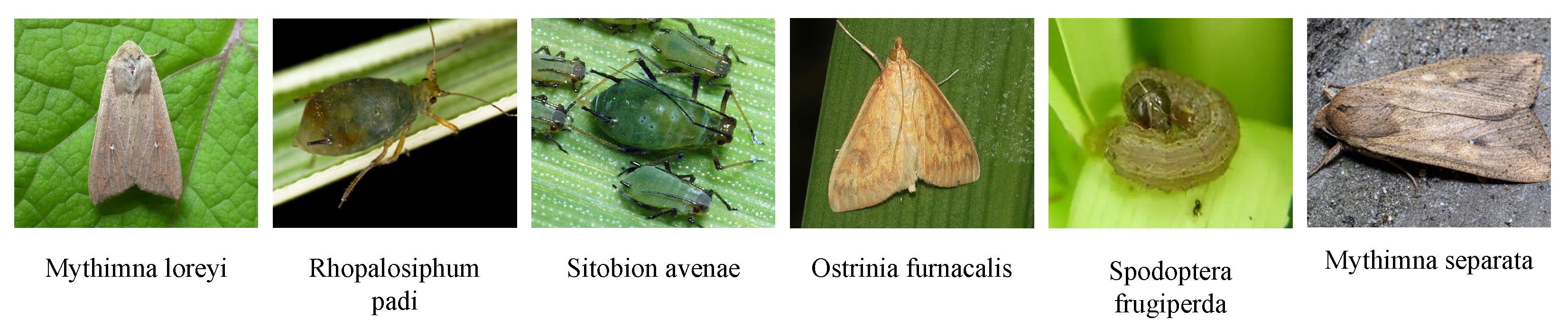

| Target pests | Mythimna separata, Spodoptera frugiperda, Ostrinia furnacalis, Sitobion avenae, Rhopalosiphum padi, Mythimna loreyi | 6 species |

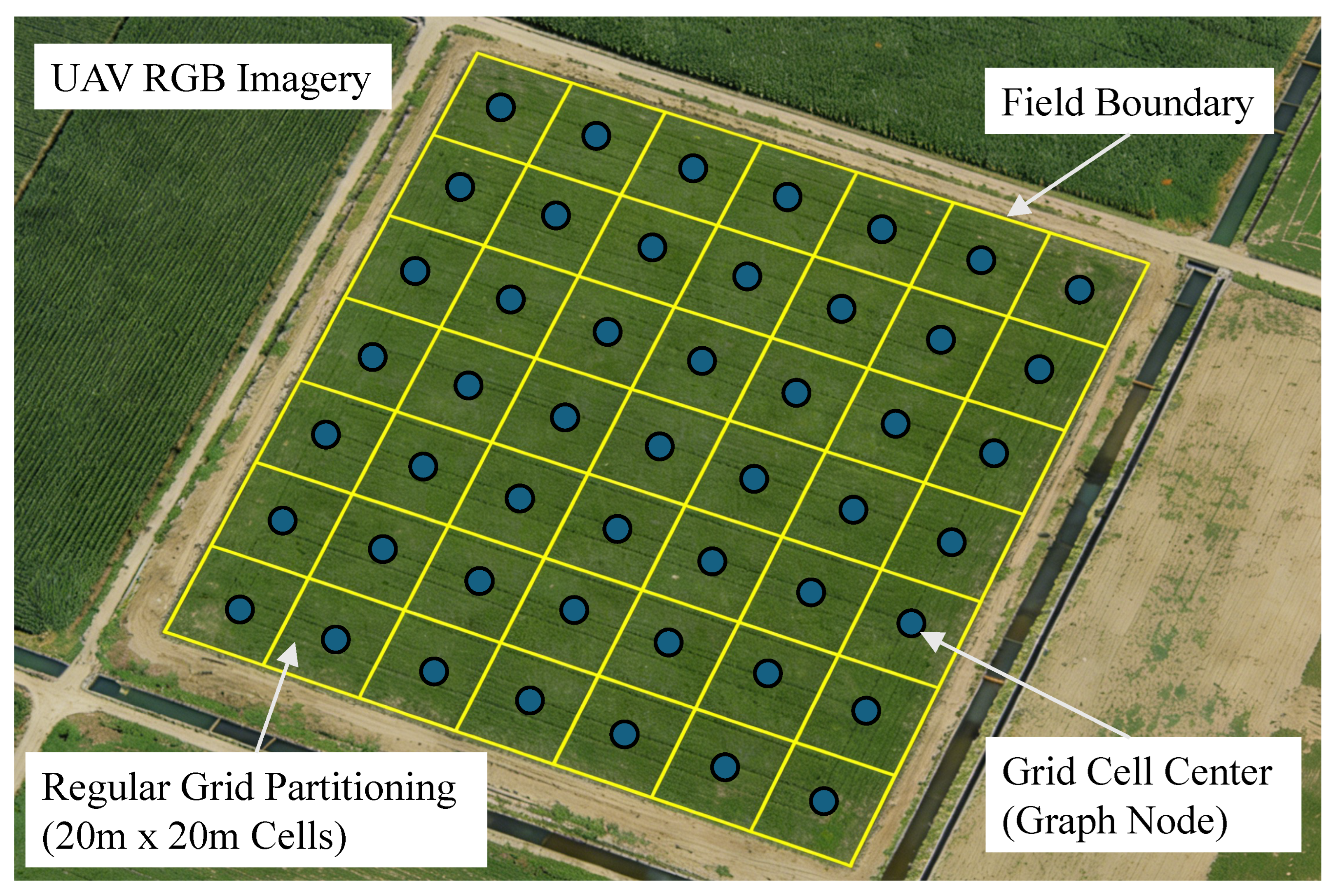

| UAV RGB images | Multirotor UAV platform | 10 cm/pixel |

| UAV multispectral images | Multispectral camera | Blue, Green, Red, NIR bands |

| Acquisition frequency | Periodic UAV flights | Every 5 days |

| Meteorological variables | Automatic weather stations | Temperature, humidity, wind, rainfall |

| Terrain data | Digital elevation model (DEM) | Spatially aligned |

| Vegetation indices | NDVI, EVI | Multispectral-derived |

| Graph nodes | Parcel-level grid units | ∼3000 nodes |

| Graph edges | Spatial and wind-weighted connections | ∼12,000 edges |

| Temporal snapshots | Time-aligned sequences | 8 time steps |

| Temporal information | Textual knowledge records | Time stamps aligned with UAV flights |

| Spatial information | Textual spatial indexing | Parcel IDs, adjacency relations |

| Textual knowledge data | Field records and annotations | Spatio-temporal metadata |

| Method | MAE ↓ | MSE ↓ | R ↑ | F1 ↑ | PMR ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 0.192 | 0.061 | 0.681 | 0.712 | 0.642 |

| ConvLSTM | 0.176 | 0.054 | 0.705 | 0.734 | 0.667 |

| ViT-Spatio | 0.168 | 0.050 | 0.721 | 0.748 | 0.683 |

| ST-GCN | 0.160 | 0.046 | 0.739 | 0.761 | 0.694 |

| UAV-GNN-Pest (Ours) | 0.130 | 0.036 | 0.814 | 0.821 | 0.779 |

| Method | MAE ↓ | MSE ↓ | R ↑ | F1 ↑ | PMR ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 0.185 | 0.058 | 0.694 | 0.723 | 0.651 |

| ConvLSTM | 0.171 | 0.051 | 0.719 | 0.741 | 0.676 |

| ViT-Spatio | 0.162 | 0.047 | 0.736 | 0.756 | 0.691 |

| ST-GCN | 0.155 | 0.043 | 0.753 | 0.769 | 0.704 |

| UAV-GNN-Pest (Ours) | 0.128 | 0.034 | 0.827 | 0.834 | 0.790 |

| Model Variant | Bayan Nur Dataset | Tangshan Dataset | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE ↓ | MSE ↓ | R ↑ | F1 ↑ | PMR ↑ | MAE ↓ | MSE ↓ | R ↑ | F1 ↑ | PMR ↑ | |

| Full Model (STAGE + EEF + DPSE) | 0.130 | 0.036 | 0.814 | 0.821 | 0.779 | 0.128 | 0.034 | 0.827 | 0.834 | 0.790 |

| w/o STAGE | 0.167 | 0.049 | 0.724 | 0.746 | 0.683 | 0.162 | 0.047 | 0.739 | 0.756 | 0.694 |

| w/o EEF | 0.149 | 0.042 | 0.763 | 0.782 | 0.721 | 0.145 | 0.041 | 0.771 | 0.790 | 0.736 |

| w/o DPSE | 0.134 | 0.037 | 0.801 | 0.819 | 0.692 | 0.131 | 0.035 | 0.815 | 0.829 | 0.701 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, C.; Fu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, J.; Liu, S.; Zhan, Y. Image-Based Spatio-Temporal Graph Learning for Diffusion Forecasting in Digital Management Systems. Electronics 2026, 15, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020356

Du C, Fu Z, Hu Y, Liu Y, Cao J, Liu S, Zhan Y. Image-Based Spatio-Temporal Graph Learning for Diffusion Forecasting in Digital Management Systems. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020356

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Chenxi, Zhengjie Fu, Yifan Hu, Yibin Liu, Jingwen Cao, Siyuan Liu, and Yan Zhan. 2026. "Image-Based Spatio-Temporal Graph Learning for Diffusion Forecasting in Digital Management Systems" Electronics 15, no. 2: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020356

APA StyleDu, C., Fu, Z., Hu, Y., Liu, Y., Cao, J., Liu, S., & Zhan, Y. (2026). Image-Based Spatio-Temporal Graph Learning for Diffusion Forecasting in Digital Management Systems. Electronics, 15(2), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020356