1. Introduction

Renewable energy sources, which have been widely installed in recent years, typically use voltage source converters (VSCs) to interface to power systems [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Since 2013, the annual addition of renewable energy capacity has surpassed that of fossil fuels and nuclear sources combined [

5]. However, there are inherent differences between generation based on VSCs and synchronous generators (SGs). VSCs lack the intrinsic ability to provide grid inertia and strength, making power systems more vulnerable during large disturbances [

6,

7].

Unlike grid-following (GFL) VSC, grid-forming (GFM) VSC can provide inertia and damping for power system and exhibits better stability in weak grids, which make it a research hotspot in recent years [

8,

9]. Nevertheless, even when equilibrium points are present, the second-order dynamics of droop control incorporating low-pass filters (LPFs) and virtual synchronous generator (VSG) control—also known as inertial GFM control—may become unstable as a result of insufficient damping [

10]. Introducing inertia into the power synchronization loop (PSL) diminishes the system’s effective damping, potentially triggering an overshoot in the power angle following a large disturbance. Such an overshoot might drive the power angle beyond the unstable equilibrium, ultimately leading to system instability.

Hybrid synchronization control (HSC), the incorporation of phase-locked loop (PLL) and PSL, is prone to exhibiting better dynamic response compared to conventional GFM control [

11]. Analysis of the transient model of HSC indicates that the incorporated PLL functions similarly to the damper windings in SG [

12], enhancing system damping and thereby improving system’s large-signal stability. By adjusting the ratio between the PLL and PSL in HSC, the VSC’s active power reference can be reduced which allows the VSC to maintain an equilibrium point after deeper voltage dips [

13]. Furthermore, a low-voltage ride-through (LVRT) strategy specifically designed for HSC-based VSCs has been proposed in recent study [

14]. This strategy significantly enhances the system’s transient stability and enables precise limitation of the fault current. Using the impedance method to perform small-signal stability analysis of the HSC-based VSC system reveals that adjusting the proportions of the PLL and PSL within the HSC can enhance the small-signal stability of the VSC under varying grid strengths [

15].

Recent advancements in HSC research have further expanded its application potential. A fault ride-through strategy based on HSC integrates the advantages of PLL and virtual synchronous generator (VSG) phase-locking to achieve stable fault ride-through without control mode switching during grid voltage sags [

16]. A current saturation ratio (CSR)-based HSC method weights PSL and PLL components by the current limiter’s CSR, collaborating with GFM converters’ current limiting to enhance synchronization stability under large disturbances and achieve precise power setpoint tracking [

17]. A modified HSC method improves the power-based synchronization loop with power reference feedforward and the voltage-based synchronization loop with a first-order inertial damping mechanism, enhancing power tracking accuracy, suppressing low-frequency oscillations, and boosting transient synchronization stability [

18]. Additionally, an HSC strategy combining power synchronization control (PSC) and PLL resolves the stability trade-off between weak and strong grids, with impedance modeling and Nyquist analysis used to evaluate the impacts of hybrid coefficients and virtual admittance on system stability [

19].

The controller of the PLL in HSC across the aforementioned research varies, and so do the voltage control loop (VCL) strategies. In [

12,

13,

14,

17,

18,

19], the PLL in HSC utilizes proportional control or improved synchronization loops, while the VCL is based on virtual impedance (VI) control or optimized damping mechanisms. Conversely, in [

15,

16,

19], both the PLL and VCL use PI controllers. Furthermore, Reference [

15] adopts reactive power-voltage droop control to generate the voltage reference value, while References [

12,

13,

14] employ constant voltage control with a directly specified voltage reference. Existing study has explored the first-swing transient synchronization stability mechanism of power-synchronized converters from the perspective of whether a stable equilibrium point exists after faults, combined with the equal-area criterion [

20,

21]. These studies also indicate that the presence of the reactive voltage control loop in VSCs reduces the transient stability margin. However, the specific underlying mechanism remains unclear. In addition, as both the HSC and the VCL incorporate the q-axis component of the point of common coupling (PCC) voltage, interaction between the two control loops may be introduced. Existing studies have not yet comprehensively investigated how the coupling between the HSC and VCL influences the system’s large-signal stability, nor have they explicitly mapped control strategy choices to physical meanings for intuitive understanding. Moreover, the impact of employing different controller combinations and key parameters on the system’s large-signal stability still lacks quantitative analysis across multiple operating conditions, and the boundaries of stability conclusions remain ambiguous. Therefore, further research is needed to systematically investigate the synergistic interaction and coupling mechanisms between HSC and VCL under different control combinations, quantify the influence of controllers and parameters on large-signal stability, and clarify the physical essence and applicable scenarios of HSC-based control strategies.

This paper investigates the large signal stability of the HSC-based VSC system under different control methods and parameters. In this paper, a Takagi-Sugeno (T-S) fuzzy model [

20,

21,

22] is employed to construct a Lyapunov function, which serves to both confirm the system’s asymptotic stability and evaluate the system’s region of asymptotic stability (RAS). Previous research has shown that employing a Lyapunov function derived from the T-S fuzzy model reduces conservatism and facilitates more straightforward evaluation of parameter influences on system stability [

23,

24,

25].

- (1)

This paper provides the first systematic investigation into the transient stability mechanism of grid-connected VSCs based on HSC when the PLL and VCL adopt different controller combinations.

- (2)

The power-angle curve method is employed to qualitatively analyze the transient stability characteristics of VSCs under different controller combinations, with and without the reactive voltage control loop.

- (3)

By establishing a T–S fuzzy model and validating the results through PSCAD electromagnetic transient simulations, the research quantitatively evaluates the system’s RAS under various controller combinations.

This paper is organized as follows: The HSC-based VSC system and its control methods are presented in

Section 2. In

Section 3, power angle curve is applied to evaluate the transient stability of VSCs under different control methods. Then

Section 4 will present the T-S fuzzy model of the HSC-based VSC and the control methods and parameters’ impact on the RAS is discussed. Then simulation results are provided to validate the analysis results in

Section 5.

Section 6 gives conclusions.

2. System Description and Modeling

Figure 1 represents the equivalent circuit of the HSC-based VSC system, where

Lf and

Cf are the filtering inductor and filtering capacitor.

All subsequent analyses in this paper are based on the simplified system depicted in

Figure 1, which serves as a simplified model of renewable energy converters transmitting power to the grid via AC transmission lines. This configuration is intentionally adopted for two key reasons: first, it isolates the core dynamics of converter-grid interaction, enabling a clear and concise investigation into how different control strategies and parameters influence system transient stability. Second, the fundamental mechanisms revealed through this simplified system ensure the conclusions retain a degree of generalizability to practical power systems.

Notably, complex benchmark systems were not selected due to modeling constraints: overly intricate system topologies would result in high-order mathematical models, introducing excessive computational complexity and obscuring the intrinsic stability mechanisms.

State equations of the equivalent circuit can be expressed as follows:

As shown in

Figure 2, the core of HSC is the adaptive coefficient

Kh, which can vary the ratio of the PLL and PSL properties, combining their respective advantages [

13]. The two most commonly employed control strategies for the PLL are proportional controller and PI controller. The VSC’s synchronization angle in the HSC can be written as:

where

In (2), θ represents the synchronization angle of HSC, ω is the angular frequency, ω0 is the reference value of the angular frequency, ΔP = Pref − P, J is the moment of inertia, D is the damping coefficient, and usq is the q-axis component of internal potential.

From (2), the power angle

δ can be obtained as

As shown in

Figure 3, the control method of the VCL employed in this paper is VI control and PI controller, and the corresponding control equation is presented below

where

In (6) and (7), usq_ref is the q-axis component of the internal potential reference; ivd_ref and ivq_ref are the dq-axis components of the current references; Lv and Rv are the VI parameters.

Since usq is controlled in both the PLL and the VCL with different types of controllers, a brief analysis of the coupling relationship between these two control loops is presented below.

The physical mechanism of the coupling between the PLL and VCL originates from their shared regulation target—the q-axis component of the PCC voltage usq, which inherently links the two loops’ functional objectives: synchronization tracking and voltage regulation. Physically, the PLL adjusts the synchronization angle based on usq to maintain grid synchronization, directly influencing the power angle δ and active power exchange between the VSC and the grid. Meanwhile, the VCL regulates the output current with reference to usq to stabilize the PCC voltage, which affects reactive power balance and further modulates the amplitude and phase of the PCC voltage. This mutual interplay forms a closed-loop coupling: variations in usq trigger concurrent adjustments in both the PLL and VCL, whose responses feedback to usq through grid-VSC interactions.

The impact of this coupling on system stability is determined by the matching degree of the control characteristics of the PLL and VCL. When the two loops adopt compatible control strategies, the coupling effect is mitigated, as their coordinated adjustments suppress oscillations in usq and enhance system damping. In contrast, conflicting control objectives amplify coupling-induced disturbances: the rigid regulation of usq by the PI-PLL conflicts with the VCL’s voltage adaptation. This physical insight explains why different control combinations exhibit distinct stability performances under large disturbances.

3. Analysis of Large Signal Stability with Different Controller Based on Power Angle Curves

In existing studies, the PLL in HSC has been implemented using either a PI controller [

15] or a proportional controller [

13,

14]. Similarly, the VCL is commonly designed using either a PI controller [

15] or a VI control method [

13,

14]. To investigate the impact of these control strategies on the large-signal stability of VSC, four control combinations are formed by pairing different PLL and VCL controllers. Each combination is analyzed individually to assess its influence on system large-signal stability.

3.1. PLL with Proportional Control and VCL with VI Control

When the PLL in the HSC adopts proportion control, the transient model of the HSC can be expressed as follows:

By comparing (8) with the rotor equation of SG, it can be concluded that

From (9), it can be seen that the adaptive coefficient Kh affect the active power reference, the equivalent inertia, and the equivalent damping coefficient. Moreover, the following rule can be easily obtained: reducing Kh increases the system’s equivalent inertia and damping coefficient, thereby enhancing the system’s transient stability.

From the above derivation, it can be concluded that when the PLL adopts proportional control, the PLL branch acts as an additional damper winding, providing extra damping to the system and improving its transient stability. In contrast, when the PLL employs PI control, the fast response and zero-steady-state-error control characteristics of the PI controller accelerate the synchronization speed of the HSC, strengthen its grid-following characteristics, and enable the VSC to adapt to stronger grids [

15].

Since the VCL adopts the VI control strategy, the equivalent circuit of the system can be represented by

Figure 4.

Based on

Figure 4, the following relationships can be obtained.

Based on the above equation, the equivalent vector diagram of the system with the VCL adopting VI control can be obtained, as shown in

Figure 5.

When the red vector in

Figure 5 is examined, it can be observed that when the voltage outer loop adopts VI control, the PCC voltage

does not strictly align with the

-axis. As a result,

does not strictly equal its reference value

, and

is not exactly zero. Moreover, when the system experiences a fault or other large disturbance, the increased current further enlarges the deviation between the PCC voltage and its reference value.

According to (10), when

is not aligned with the

-axis, the system’s equivalent active power reference becomes smaller than the given active power reference. During a fault, the rise in current increases the angle difference between

and

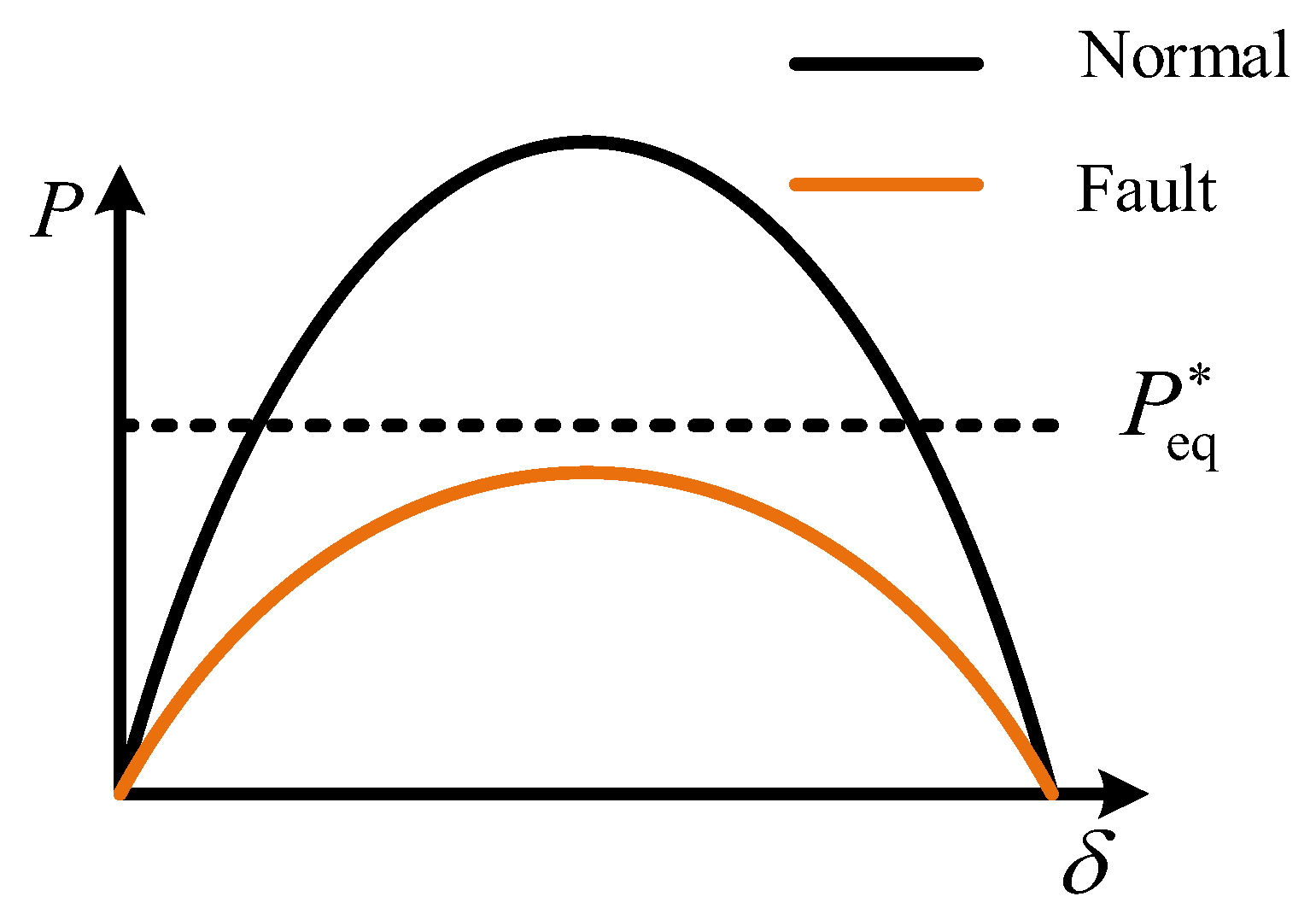

, which further reduces the equivalent active power reference. Based on the power-angle curve, the existence of an intersection between the active power reference and the power-angle curve indicates the presence of a stable operating point, which is a necessary condition for system stability. Therefore, the reduction in the equivalent active power reference allows the system to maintain a stable operating point under deeper voltage sags, as illustrated in

Figure 6a.

However, the existence of a stable operating point is only a necessary condition for maintaining system stability. If the power angle experiences large oscillations after a major disturbance and crosses the unstable equilibrium point, the system will fail to recover stability. According to (10), reducing

decreases the system’s equivalent active power reference, which enables the existence of a stable operating point. Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 6b, decreasing

enlarges the deceleration area and reduces the acceleration area, thereby enhancing the system’s transient stability. Finally, (10) indicates that reducing

increases the system damping coefficient, which suppresses the post-disturbance power-angle oscillation amplitude and effectively mitigates the risk of instability caused by the power angle exceeding the unstable equilibrium point.

3.2. VCL with PI Control

When the VCL adopts PI control, both

and

are tightly regulated around their reference values, and the corresponding phasor diagram of the system is shown in

Figure 7.

In this case,

is aligned with the d-axis, and

. Therefore, according to (10), the equivalent active power reference is equal to the given active power reference, as shown below:

As a result, when the voltage control loop uses PI control, the active power reference value will not decrease when the grid voltage drops.

When the grid voltage drops, the output power of the VSC is expressed as follows:

where

usF and

ugF is PCC voltage and grid voltage during faults, respectively.

Zg is the grid impedance.

As shown in

Figure 8, when the voltage drops, the power-angle curve shifts downward. However, since

usF remains equal to its pre-fault value and only

ugF decreases, the degree of downward shift is smaller compared to the PLL with proportional control and VCL with VI control (P + VI). In the following text, control combinations are denoted in the format of “P + VI”, where the term before the plus sign represents the controller used for the PLL, and the term after the plus sign represents the controller used for the VCL. When the voltage dip is deeper, the VSC may lose its stable equilibrium point and become unstable. Therefore, the large-signal stability of VCL with PI controller is slightly weaker than that of P + VI control.

Since the VSC output voltage is always maintained near its rated value, a deeper voltage sag on the grid side will result in a large voltage difference between the grid voltage and the VSC output voltage. This voltage difference leads to a significant fault current, which poses a threat to the transient stability of the system.

Since the characteristics of the PLL using proportional control and PI control show little difference when the VCL employs PI control, the following and previous analysis simplifies the study by focusing only on the P + PI control combination.

3.3. PLL with PI Control and VCL with VI Control

When the PLL in the HSC adopts PI control,

usq is strictly controlled near 0 by the integral part of the PI controller. Therefore, according to (11), the system’s active power reference value will not decrease after the grid voltage drops. Moreover, since the VCL uses VI control,

usd will decrease after the grid voltage drops. Therefore, from (12), it can be seen that after the grid voltage drops, the system’s power angle curve will shift significantly downward, causing the system to lose its stable operating point, as shown in

Figure 9.

From the above analysis, it can be concluded that when the PI + VI control combination exhibits the worst transient stability.

3.4. Q-U Control

This part investigates how

Q-U control affects transient stability. By ignoring the line resistance, the active and reactive power output of the VSC can be approximately described using the following expressions:

As shown in

Figure 10, The control equation for the

Q-U control loop is as follows:

where

kq is the

Q-U control sag coefficient and

u0 is a constant 1.

By combining (13) to (15), the expression for the PCC voltage under grid voltage dip can be obtained as:

Define intermediate variable

Then (17) can be expressed as

Take the partial derivative of both sides of (18) with respect to

.

According to (17), the partial derivatives of

with respect to

kq,

δ, and

ugF can be obtained as follows:

When δ ∈ [0, π/2], is directly proportional to both ugF and usF. Therefore, usF is also directly proportional to ugF. On the other hand, is inversely proportional to δ, which implies that usF is inversely proportional to both usF and δ.

As a result, when the grid voltage drops, the power angle

δ increases and

usF decreases, leading to a further downward shift in the power-angle curve and a degradation of the system’s transient stability.

Figure 11 clearly illustrates the above conclusion.

From the preceding analysis, implementing Q-U control leads to a further downward shift in the power-angle curve after a grid voltage dip, which deteriorates the system’s transient stability. Consequently, for the subsequent comparisons of transient stability across various control schemes, Q-U control is disabled, and the usd_ref is maintained at 1.

4. Large Signal Stability Analysis with Different Control Based on T-S Fuzzy Model

While the power angle curve analysis above can qualitatively illustrate the system’s transient stability under various control strategies, it lacks a quantitative assessment. To address this limitation, numerical approaches have been introduced for evaluating the transient stability of VSCs. Among these, numerical simulation and the Lyapunov function method are commonly used for transient stability analysis in power systems. Previous research has shown that the Lyapunov energy function formulated with the T-S fuzzy model offers reduced conservatism and simplifies the evaluation of how different parameters affect system stability. Accordingly, the transient stability analysis for the control strategies discussed here will be performed using this approach.

4.1. Principle of T-S Fuzzy Modelling Method

Reference [

25] presents an algorithm to estimate the attraction domain of a nonlinear system expressed as

x = A(x)x by employing the T-S fuzzy model. For each nonlinear element within the matrix function

A(

x), lower and upper bounds are assigned, resulting in two matrices

Ai. When the system’s state equation contains

r nonlinearities, 2

r matrices of

A(

x) are generated. Reference [

26] presents the stability criterion for this method, indicating that if the Linear Matrix Inequality (LMI) in (23) has a solution, the nonlinear system is asymptotically stable.

where

M represents a positive definite matrix. The following expression defines the Lyapunov function for the nonlinear system:

The specific steps are as follows [

27,

28,

29,

30]:

The steps for developing the Lyapunov energy function are summarized below:

Step 1: Represent the nonlinear system and define the nonlinear matrix function A(x).

Step 2: Determine the lower and upper bounds for each nonlinear term within A(x).

Step 3: Implement a program to solve (23). If a solution exists, the matrix M will be automatically derived, and the Lyapunov energy function can then be computed.

Step 4: The Lyapunov energy function characterizes the system’s RAS, serving as a tool to evaluate its large-signal stability. A smaller RAS indicates a higher likelihood of system instability.

Following the steps outlined above, we have established the T-S fuzzy model for this paper, as shown in

Appendix A.

To verify the accuracy of the T-S fuzzy model established above, all other parameters are kept constant, and the critical active power obtained through simulations under different SCR values is compared with the critical active power calculated by the T-S fuzzy model.

As shown in

Figure 12, the stability boundary obtained from the T-S fuzzy model is generally consistent with the simulation results. As the SCR increases from a low to a high value, the system’s critical active power first increases and then decreases. From the active power boundary, the T-S fuzzy model developed in this paper is accurate and can measure the stability boundary of the system accurately.

4.2. Effect of Kh on the RAS with Different Control

One of the key aspects of the HSC lies in the coefficient

Kh which determines the proportional between PSL and PLL. To investigate the impact of

Kh on the transient stability of the system, the RAS under different

Kh values are shown in

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15.

As shown in

Figure 13, when the PLL in the HSC adopts proportional controller and the VCL adopts VI control, the RAS of the system gradually expands as

Kh decreases. The analysis results of the RAS are consistent with those obtained from the power-angle curve analysis discussed earlier. With a reduction in

Kh, the active power reference declines, whereas the equivalent inertia and damping coefficients rise, leading to improved transient stability and a larger RAS for the system.

As shown in

Figure 14, when the VCL adopts PI control, the RAS increases with decreasing

Kh, but the change is not significant. This is due to the characteristic of PI control, where

usq is regulated tightly around 0. According to (11), variations in

Kh have no impact on the active power reference. However, as indicated by (9), a smaller

Kh increases the system’s equivalent inertia and damping coefficient, thereby enhancing transient stability.

Finally,

Figure 15 illustrates the RAS for various

Kh values when the PLL in the HSC uses a PI controller and the VCL employs VI control. The results in

Figure 15 are similar to those in

Figure 14. This is because the PI control characteristic of the PLL regulates

usq tightly around 0. In this case, variations in

Kh have no effect on the equivalent active power reference.

4.3. Comparison of the RAS Under Different Control Strategies

According to the above analysis, different values of Kh influence the domain of RAS. Therefore, to compare the transient stability under different control strategies, the RAS for the four control combinations are analyzed and compared under various values of Kh.

As shown in

Figure 16, when

Kh = 0.8, the control combinations in which the P + PI control combination exhibit the largest RAS and thus the best transient stability. This is followed by the P + VI control combination. This occurs because, with a relatively large

Kh, the second term on the right side of (9) remains small, causing only slight changes in the active power reference. During grid voltage dips, if the VCL adopts VI control, the drop in PCC voltage causes the power-angle curve to shift downward, potentially losing an equilibrium point. Conversely, applying PI control in the VCL keeps the PCC voltage almost constant, which reduces the downward shift in the power-angle curve and improves transient stability.

As shown in

Figure 17, when

Kh = 0.5, the RAS under the first two control combinations exhibit minimal differences, while the system with the PI + VI control combination still shows the smallest RAS.

As shown in

Figure 18, when

Kh = 0.2, the system with P + VI control combination exhibits the largest RAS, indicating the best transient stability. As

Kh decreases, the second term on the right-hand side of (9) increases, resulting in a more significant reduction in the active power reference following a voltage sag. Consequently, the P + VI control combination provides the best transient stability under this condition.

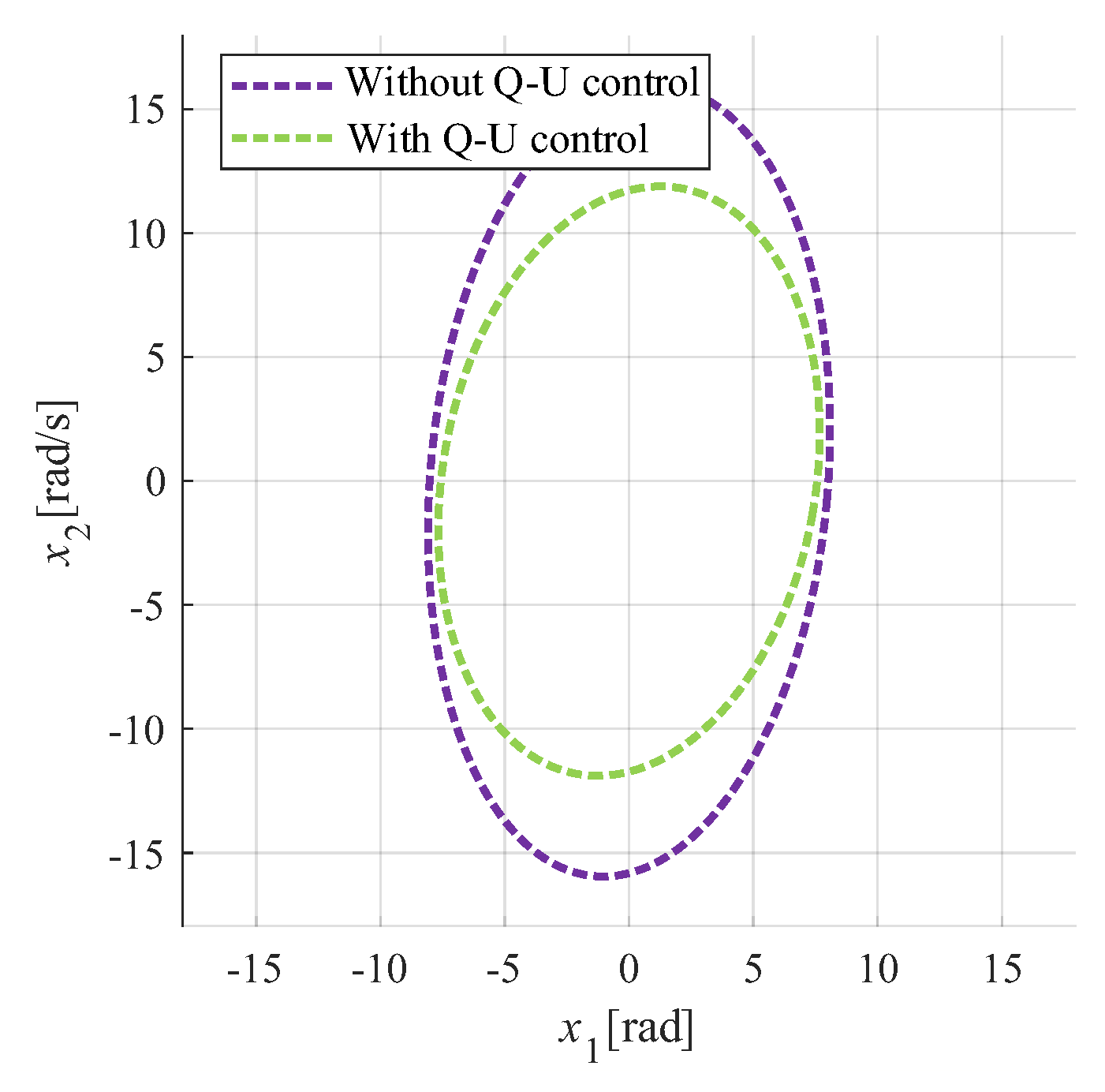

Finally, the RAS for the four control combinations are compared with and without Q-U control. Since the previous analysis of the impact of Q-U control on system transient stability is generally applicable to all four control combinations, this section selects the system with P + VI control combination for the comparison of RAS.

As shown in

Figure 19, the results show that after incorporating

Q-U control, the RAS become smaller, indicating a degradation in transient stability. This observation is consistent with the previous analysis.

6. Conclusions

This paper investigates the large-signal stability of HSC-based VSCs under different control strategies. The main findings are as follows:

(1) Reducing the HSC coefficient Kh improves transient stability, with the most pronounced effect in the P + VI combination. For example, under SCR = 3, decreasing Kh from 0.9 to 0.3 enables the P + VI combination to withstand complete voltage sags, while reducing the maximum power angle overshoot from 1.35 p.u. to 1.3 p.u. and prolonging the transient recovery time from 0.5 s to 1.5 s.

(2) The optimal control combination depends on Kh: When Kh is large, the P + PI combination achieves the best stability with a smaller power angle overshoot (1.31 p.u.). As Kh decreases, the P + VI combination becomes optimal. The PI + VI combination consistently performs the worst, with ugF = 0.57 p.u. and the largest power angle overshoot (up to 1.41 p.u.).

(3) Q-U control deteriorates transient stability by reducing the PCC voltage during faults. For the P + VI combination, enabling Q-U control increases ugF from 0 p.u. to 0.21 p.u., confirming its adverse effect.